Abstract

The sustainable development of tourism is a critical issue, and immersive tourism has emerged as a key market trend that significantly contributes to this goal. Experiencescape, a vital component of immersive tourism, plays a crucial role in shaping tourists’ experience and promoting sustainability within the tourism industry. Taking Chang’an Twelve Hours Theme Block as the research object, this paper investigates the composition and impact of immersive tourism experiencescape by utilizing grounded theory and hierarchical regression analysis on data derived from online reviews and tourist surveys. The findings reveal that immersive tourism experiencescape is divided into two main categories: physical and interpersonal. The physical experiencescape consists of three dimensions: functional facilities, thematic atmosphere, and basic environment. The interpersonal experiencescape, on the other hand, includes tourism performances, host-guest interaction, and personal service. The study demonstrates that immersive tourism experiencescape exerts a significant positive influence on tourists’ behavioral intentions, with emotional experience serving as a partial mediator in this relationship. These insights offer valuable theoretical and practical implications. They provide a perspective for enhancing the sustainability of tourism by improving the quality of immersive experiences.

1. Introduction

Sustainable tourism minimizes negative impacts on natural and cultural environments, and ensures long-term economic benefits without depleting essential resources [1]. Previous studies have shown that sustainability plays a key role in improving the competitiveness of tourism destinations [2]. In addition, tourism can also contribute to other areas, such as sustainable rural development [3,4]. Therefore, the sustainable development of tourism is of great importance. Tourism is an experience-based industry, and thus the promotion of sustainable tourism development should also take into account the important role of experience. The goal of tourism service is to provide unforgettable and positive experiences for tourists [5]. This requires destination managers to focus on immersion for tourists [6], as immersive experience can provide a sense of escaping reality [7]. In recent years, the popularization and innovation of virtual reality technology have provided technical support for immersive tourism experience [8], and VR equipment provides tourists with sensory stimulation and emotional involvement, creating immersive experience in virtual tourism [9]. In real tourism activities, immersive experience programs such as immersive scripts and immersive performances also increase the sense of tourist participation and interaction by generating immersive scene atmosphere [10], which has a reinforcing effect on experience and memory [11].

The experiencescape is the setting in which individuals generate their experiences as part of their mental process. The concept of “experiencescape” aims to capture how experience is produced and consumed [12], emphasizing the relevance of the scenes (i.e., space or environment) in constructing experience and facilitating interactions between participants [13]. Previous research has explored various dimensions of experiencescape in different contexts, including intangible cultural heritage tourism [14], nature-based tourism [15], and ski tourism [16], among others. Additionally, building on servicescape theory, other studies have investigated the impact of experiencescape, such as the influence of onboard experiencescape on visitors’ emotions [17] and the effect of farm tourism experiencescape on creating extraordinary experiences [18]. In fact, The realization of immersive tourism is intrinsically tied to the construction of the experiencescape. On the one hand, the experiencescape forms the essential environment where immersive tourism unfolds, as tourists are essentially immersing themselves within this curated space [19]. On the other hand, the experiencescape also serves as a driving force for immersive tourism by facilitating interactions between the tourist and the environment, which in turn influences the depth and quality of their immersion [20]. It is evident that the experiencescape plays a foundational role in supporting immersive tourism. However, the current body of research on immersive tourism experiencescape is limited, which constrains our comprehensive understanding of immersive tourism as a whole. To bridge this gap, it is essential to conduct further research on immersive tourism experiencescape. Chang’an Twelve Hours Theme Block is China’s first immersive Tang-style city life block, marking a significant evolution in immersive tourism. Unlike previous projects that offered only a single immersive experience, this destination provides a comprehensive, full-scene immersion. The questions this study intend to address are: Are the previous structural dimensions of experiencescape applicable to the emerging phenomenon of full-scene immersive tourism? What is the mechanism by which immersive tourism experiencescape influences tourists’ behavioral intentions? By addressing these questions, this research contributes valuable insights into the structural dimensions and influence mechanisms of immersive tourism experiencescape. This is not only theoretically enriching but also practically significant for promoting the sustainable development of immersive tourism and enhancing the quality of the tourism experience.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Immersive Tourism Experiencescape

The concept of “-scape”, first proposed by Kotler in 1973, describes a well-designed external environment aimed at inducing specific emotions and influencing consumer behavior [21]. On this basis, the concept of “servicescape” was further derived [22], and the concept of “-scape” was gradually expanded from the internal physical environment to the external environment and spatial atmosphere [23]. With the shift from the service economy to the experience economy, the concept of “experiencescape” has emerged [12]. Later, Willson developed the concept of “experiencescape” as a space full of emotion, concentration, engagement, and personal meaning [24]. In the field of tourism, experiencescape is considered to be a holistic environment containing physics, society, symbols, products, and services in which tourists interact and influence each other [25]. Scholars have analyzed the frameworks and dimensions of experiencescape in different tourism experience contexts, involving intangible cultural heritage experiencescape [14], Hanfu destination experiencescape (Hanfu refers to traditional dress of the Han Chinese people) [26], and tourscape [27].

“Immersion”, as a metaphor, refers to being surrounded by a completely different reality and having one’s attention completely occupied [28]. Immersion is a subjective experience that involves both physical and mental engagement [29], and immersion makes it possible for a person to experience a conscious separation from the physical world [28]. “Immersive experience”, on the other hand, refers to the incorporation of personal involvement in moments conceived through multiple senses, creating fluid and uninterrupted physical, mental, or emotional engagement with the current experience, and enabling the user to achieve lasting psychological and emotional effects after the experience [30]. At present, there is no clear definition of immersive tourism experiencescape in academia. Based on a review of the literature, this paper defines immersive tourism experiencescape as a holistic environment that enables tourists to temporarily experience a separation from the real, physical world through physical and mental engagement. As immersive tourism is a relatively new phenomenon, research on immersive tourism experiencescape remains limited. This area of study is still in its early stages, leaving much unexplored yet full of potential. The scarcity of existing studies highlights the need for further research, which could uncover valuable insights and contribute significantly to our understanding of immersive tourism and its experiencescape.

2.2. Emotional Experience

The most fundamental goal of the tourism experience is the pursuit of happiness, which is a form of emotions [31]. Emotion is a person’s psychological experience of whether or not something is in line with their own needs and desires [32]. The emotions experienced during tourism activities are the core elements of the tourism experience [33]. Emotional experience consists of an individual’s conscious, subjective, attitudinal experience of whether objective conditions meet their needs, reflecting the strong feelings associated with specific stimuli formed by individuals after cognitive assessment [34]. Emotional experience can be categorized into positive and negative emotions according to their validity [35].

The inextricable relationship between emotional experience and tourism experience has attracted attention and research to the topic of emotional experience in tourism studies. For example, “home feeling”, as a type of emotional experience, affects the online rating of homestays [36]. In the experience of natural forest landscapes, tourists’ emotions change with the seasons [37]. In addition, an interesting study has shown that tourism souvenirs such as fridge magnets trigger positive emotional and affective responses by generating and protecting memories [38]. Other relevant studies, in general, involved the essence [39], types [40,41], influencing factors [42], and influencing effects [43] of tourists’ emotional experience. The influencing factors of tourists’ emotional experience can be divided into two categories: non-experiential site factors and experiential site factors. Experiential site factors mainly include product factors, environmental factors, and experiential processual factors; while environmental factors include both natural and interpersonal factors [44]. Therefore, the experiencescape, as a holistic environment, is one of the influencing factors of emotional experience. Studies have paid attention to the influence of scene elements on emotional experience [45], but they have focused only on positive emotions, while neglecting the influencing factors of negative emotions. However, positive and negative emotions have different generating mechanisms and also have different influencing effects on behavior, and thus should be studied differently [44]. Therefore, this study will further explore the effects of different experiencescape elements on different emotional experiences.

2.3. Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions

Behavioral intention is an important predictor of actual behavior, which is defined as an individual’s tendency to respond attitudinally to a goal [46]. In the field of tourism, behavioral intention is an important concept for understanding tourists’ destination choices and future motivation and behavior [47]. It mainly consists of the willingness to revisit, recommend, and pay a premium [48]. Among these, “revisit willingness” specifically refers to tourists’ intention to return to the destination in the future [49], “recommendation willingness” refers to tourists’ tendency to recommend the destination to their family and friends [50], and “willingness to pay a premium” refers to tourists’ consumption tendency to pay higher prices for tourism products and services [48].

Behavioral intention can be regarded as an important indicator of an industry’s success in retaining customers [51], and tourists’ behavioral intentions play a key role in the sustainable development of tourism [52]. Studies to date have explored the effects of destination image, tourists’ perceived value, etc. on tourists’ behavioral intentions. Marques found that the perceived image, emotional image, and unique image of a tourist destination all have a significant effect on tourists’ recommendation intentions [53]. Additionally, Han et al. found that social and emotional symbols can also influence consumer’s booking intention [54]. Sun et al. verified that perceived value can influence tourists’ behavioral intentions through overall satisfaction and place identity [55]. Working from the emotional event theory, Tu and Lin examined the cross-layer influence path by which tour guide humor affects tourists’ behavioral intentions, especially the chain-mediated effect of the variables of positive emotions and destination image in this process [56]. Despite its importance to the destination image, the concept of “experiencescape” has been relatively underexplored in academic research. The specific influence of various dimensions of experiencescape on tourists’ behavioral intentions, as well as the mechanisms by which these influences operate, remain unclear. Therefore, this paper delves into the mechanisms by which tourism experiencescape shapes tourists’ behavioral intentions, with a particular focus on distinguishing the roles played by positive and negative emotions within this process.

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Object

The Chang’an Twelve Hours Theme Block, located in Xi’an, China, serves as an ideal case study for exploring immersive tourism. Xi’an, recognized by UNESCO as a “World Historic City” in 1981, is a pivotal birthplace of Chinese civilization and the Chinese nation. It is also the starting point of the Silk Road and the historic capital of 13 dynasties. These attributes provide a strong foundation for the development of the Chang’an Twelve Hours Theme Block, the first immersive Tang-style city life block in China and a renowned immersive tourist destination.

The block is deeply integrated with the intellectual property (IP) of the TV series “Twelve Hours of Chang’an” and embodies the cultural essence of a Tang-style marketplace. In July 2023, the Chang’an Twelve Hours Theme Block was selected as the “National Pilot Cultivating New Space for Smart Tourism Immersion Experience” by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China. This recognition underscores its significance and representativeness as an immersive tourism destination, making it a fitting subject for research in this field.

3.2. Research Methodology

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, integrating both qualitative and quantitative research methods to provide a comprehensive analysis. In the qualitative phase, grounded theory served as the primary methodological framework. The analysis was conducted using NVivo 11.0 software, following the grounded theory’s core processes of open coding, spindle coding, and selective coding. This approach enabled the identification of the structural dimensions of immersive tourism experiencescape.

In the subsequent quantitative phase, research hypotheses were formulated based on the insights gained from the qualitative analysis and a thorough literature review. These hypotheses were used to construct the theoretical research model, which was then tested using hierarchical regression analysis. Hierarchical regression is a sophisticated statistical method that categorizes independent variables into multiple layers based on their logical influence order. This approach allows for a precise estimation of each independent variable’s unique contribution to the dependent variable, thereby clarifying the relationships and hierarchy among the variables. This dual-phase research design ensures a robust and nuanced understanding of the factors influencing immersive tourism experiencescape.

4. Study 1: Dimensional Composition of Immersive Tourism Experiencescape

4.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

In this study, the Octopus Collector was used to collect online reviews on ctrip.com and Dianping.com from tourists who had visited the Twelve Hours of Chang’an Theme Block as the analysis data. The specific steps were as follows: Capture all review data from the scenic area’s opening, from 30 April 2022, to 31 August 2023, totaling 5802 items. To improve the quality of the crawled data, several preprocessing steps were carried out: (1) Removing duplicate comments: Instances where the same content appeared multiple times in the dataset were identified, and only one instance of each duplicate comment was retained, with all others deleted. (2) Eliminating irrelevant comments: Comments that lacked practical significance or were unrelated to the tourism experience—such as phrases like “Places that must be visited”, “Prepare in advance”, “It’s OK”, or “Follow the program”—were removed from the dataset. (3) Correcting typographical errors: The text was reviewed to identify and correct any misspelled words or incorrect characters in the comments. This process ensured the data was cleaner, more relevant, and better suited for analysis. After careful review and meticulous selection, a total of 5517 valid comments were identified, amounting to 565,924 words. From this dataset, two-thirds of the comments were randomly selected and coded using NVivo 11.0 software for further analysis. The remaining 1/3 of the data were used for theory saturation testing. During the coding process of the remaining data, no new concepts or categories emerged, indicating that the data had reached theoretical saturation.

4.2. Dimensional Composition of Immersive Tourism Experiencescape

4.2.1. Coding Process

In the open coding stage, the author read the text material sentence by sentence and paragraph by paragraph. Using NVivo 11.0 software and following the analysis logic of “defining phenomena-developing concepts-exploring categories”, the text material was processed through labeling, conceptualizing, and categorizing in relation to the research theme. During the coding process, careful attention was given to the following points: (1) Considering the multi-layered meanings of the data. A single data segment might simultaneously contain multiple meanings, and these multiple meanings were captured during coding, leading to the creation of corresponding multiple nodes. (2) Repeated coding of the same data segment. If a data segment involved multiple concepts, it was coded into multiple nodes to ensure comprehensiveness in the analysis. (3) Continuous revision and reflexive adjustment. As the data analysis progressed, previously defined nodes were continuously revised or restructured. Additionally, the researcher regularly reflected on the coding process to check for any overlooked concepts or whether too many dispersed nodes needed merging. In cases where classification was unclear or definitions were difficult, special annotations were made, and the research team collectively discussed and determined the results. Finally, 449 nodes were created from the textual materials. These nodes were merged to form the initial concepts, and the initial concepts were then refined and condensed around the main theme of the study, with a total of 27 canonical concepts refined and 11 initial categories formed. Examples of open coding are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of open coding.

In the spindle coding stage, the initial categories obtained from open coding were further classified and conceptualized based on their intrinsic relationships. Using the constant comparative method—continuously comparing different categories and their relationships—the most suitable categories and relationships were determined. Ultimately, three main categories were identified: immersive tourism experiencescape, emotional experience, and tourists’ behavioral intentions. After completing the axial coding, the coding results were reviewed by a professor of tourism management and a doctoral student to ensure reliability and validity. The results of spindle coding are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of spindle coding.

During the selective coding stage, repeated comparisons and reflections on the main categories and original data revealed that each of the categories identified through spindle coding represented distinct characteristics. If any one of these categories were removed, it would be impossible to comprehensively summarize the original data. Ultimately, the core category identified in this study was “the influence mechanism of immersive tourism experiencescape on tourists’ behavioral intentions”. This core category encapsulates the study’s central narrative: immersive tourism experiencescape shapes tourists’ behavioral intentions by evoking their emotional experience.

4.2.2. Dimensional Characterization of Immersive Tourism Experiencescape

Academics commonly use Pizam’s experiencescape model, which classifies the dimensions into six components: sensory, functional, social, natural, cultural, and hospitality culture [57]. Grounded analysis categorizes the immersive tourism experiencescape into two primary types: physical and interpersonal. The physical experiencescape encompasses functional facilities, thematic atmosphere, and basic environment, while the interpersonal experiencescape includes tourism performances, host-guest interaction, and personal service. Compared to the dimensional breakdown of the experiencescape, the dimensions of the immersive tourism experiencescape exhibit the following distinctive characteristics:

- (1)

- The immersive tourism experiencescape does not prominently feature dimensions of nature and hospitality culture. In these destinations, tourism resources are predominantly man-made landscapes, with natural elements being relatively scarce, thereby omitting the dimension of nature. Additionally, in immersive tourism settings, the traditional concept of the “host” is diminished. The physical and psychological distance between performers, staff, and tourists is reduced, leading to a less pronounced presence of hospitality culture.

- (2)

- The distinctive features of the immersive tourism experiencescape are evident in three key aspects: thematic atmosphere, tourism performances, and host-guest interaction. These elements can be viewed as further refinements of sensory, social, and cultural dimensions. The creation of thematic atmosphere is crucial for the immersive tourism experience, because a specific atmosphere can stimulate the needs of tourists, and a good atmosphere can attract tourists and bring success to the tourist venture [58]. Tourism performances mobilize all the senses of the tourists, bring tangible experience to tourists [59], and are an important part of the immersive tourism experiencescape. In the tourism process, tourists do not want to be passive, but prefer to actively participate in the service output process [60], and the interaction with NPCs can deepen their immersive feeling, thus reflecting the importance of the host-guest interaction in the immersive tourism experience.

5. Study 2: Relationship Linking Immersive Tourism Experiencescape and Emotional Experience to Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions

5.1. Research Hypothesis and Model Construction

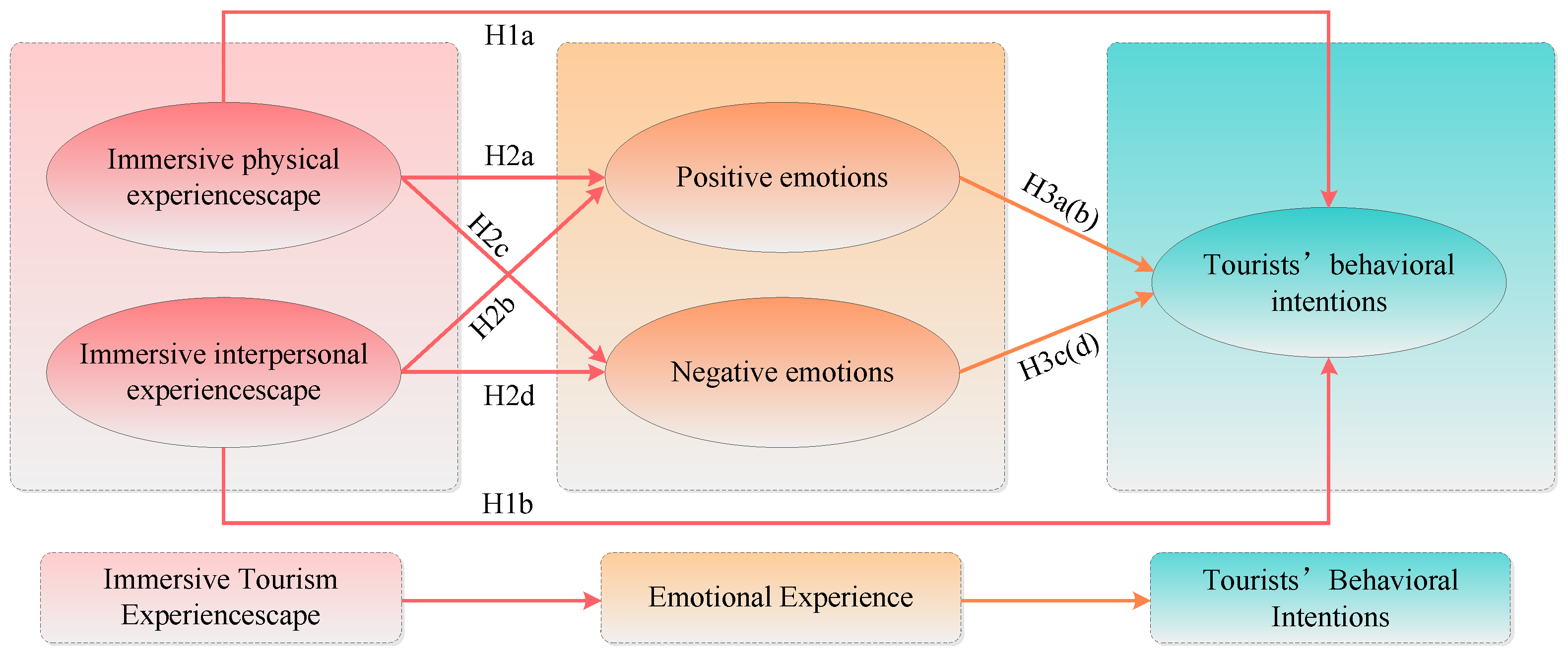

Building on the grounded results of study 1, the immersive tourism experiencescape can be categorized into two main types: physical and interpersonal. To investigate how these different types of immersive experiencescape influence tourists’ behavioral intentions, this paper will use this classification as a foundation. By integrating theoretical insights, we will develop research hypotheses and employ quantitative methods to test them.

5.1.1. Immersive Tourism Experiencescape and Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions

Physical elements in a servicescape can be important cues for customers to judge service quality, which in turn affects their purchasing decisions [27]. Experiencescape, as an extension of servicescape, focuses on service quality and experience quality, influences tourists’ choice of destination, and affects tourists’ behavior [61]. In the field of tourism, studies have shown that the thematization and scenario of the shopping environment can stimulate tourists’ impulsive consumption and that internal atmosphere creation, product display, and sales service all have a significant positive impact on tourists’ willingness to shop behavior [45]. Local food experiencescape in tourist destinations can increase tourists’ satisfaction and willingness to revisit by providing unforgettable tourist experiences [62]. Immersive tourism experiencescape provides tourists with the opportunity to truly escape from reality, which is conducive to the formation of a memorable tourism experience, thus increasing tourists’ intention to revisit and recommend. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a):

Immersive physical experiencescape has a significant positive effect on tourists’ behavioral intentions.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b):

Immersive interpersonal experiencescape has a significant positive effect on tourists’ behavioral intentions.

5.1.2. Immersive Tourism Experiencescape and Emotional Experience

Numerous studies have confirmed that good physical elements evoke positive emotions in customers, such as feeling happy, comfortable, and welcome [63]. In tourism shopping servicescape, the tangible facilities, decorations, and merchandise of the store, the intangible service, atmosphere, and policies, and servicescape elements such as brand and reputation are all important elements that influence tourists’ perception and experience of tourism shopping [45]. In the immersive tourism experiencescape, tourists’ positive perceptual evaluations of a series of physical elements, such as tourism performances and functional facilities, can bring positive affective responses, while negative perceptual evaluations bring negative affective responses. In terms of interpersonal scene, previous research has demonstrated that vibrant crowds can be highly infectious, offering tourists an opportunity to emotionally recharge and self-heal, thereby providing a positive emotional experience [64]. Good interaction between tourists and servicescape will produce more happy emotional responses [45]. However, when the number of tourists in the scene exceeds the tourists’ psychological expectations and there is a lack of order management, crowding will lead to negative emotions [65], and when tourists perceive crowding in the social space, the negative emotions triggered by the restrictions that crowding imposes on the tourist experience will exceed the positive emotions that can be brought about [66]. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a):

Immersive physical experiencescape has a significant positive effect on positive emotions.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b):

Immersive interpersonal experiencescape has a significant positive effect on positive emotions.

Hypothesis 2c (H2c):

Immersive physical experiencescape has a significant negative effect on negative emotions.

Hypothesis 2d (H2d):

Immersive interpersonal experiencescape has a significant negative effect on negative emotions.

5.1.3. Mediating Effect of Emotional Experience

The theory of cognitive appraisal of emotion, describes the mental processes that individuals undergo when they encounter environmental stimuli, and has been used to examine differences in the emotional responses of different individuals to the same event on different occasions [67]. The theory of cognitive appraisal of emotion suggests that an individual’s cognitive appraisal of an event or situation produces different emotional states and guides their subsequent behavior [68]. This has led to the formation of a more recognized construction path of “cognitive evaluation → subject’s emotion → subject’s behavior” [69]. Servicescape theory shows that the physical and social dimensions of a consumption locale can cause emotional changes in customers and thereby influence their behavior [70]. Tourists’ perception of immersive tourism experiencescape is an important antecedent variable of their behavioral intentions, and emotional experience has a significant effect on tourists’ behavioral intentions [71]. Thus, emotional experience plays a mediating role between immersive tourism experiencescape and tourists’ behavioral intentions. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a):

Positive emotions mediate the effect of immersive physical experiencescape on tourists’ behavioral intentions.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b):

Positive emotions mediate the effect of immersive interpersonal experiencescape on tourists’ behavioral intentions.

Hypothesis 3c (H3c):

Negative emotions mediate the effect of immersive physical experiencescape on tourists’ behavioral intentions.

Hypothesis 3d (H3d):

Negative emotions mediate the effect of immersive interpersonal experiencescape on tourists’ behavioral intentions.

The theoretical framework model of this study, based on the above theoretical assumptions, is proposed as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of the study.

5.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

Data were collected using a questionnaire comprising two parts: the first collected tourists’ demographic information, while the second collected tourists’ perception of immersive tourism experiencescape, emotional experience, and tourists’ behavioral intentions. Immersive tourism experiencescape was measured using the scale of Pizam and Tasci [57], positive and negative emotions were measured using the scale of Qiu Lin et al. [72], and tourists’ behavioral intentions were measured using the scale of Hosany et al. [35]. All scales used in this study were based on these established scales, with appropriate modifications based on the results of Study 1. All scale questions were in the form of a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. This study used offline questionnaires to collect data: 268 questionnaires were collected from 10 September 2023 to 20 September 2023 at the Chang’an Twelve Hours Theme Block. A total of 33 invalid questionnaires were excluded, giving a final number of 235 valid questionnaires, with a validity rate of 87.7%.

5.3. Data Analysis

5.3.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

SPSS 27.0 software was utilized to assess the reliability of the data. The results indicate that the Cronbach’s reliability coefficients for the five variables—immersive physical experiencescape, immersive interpersonal experiencescape, positive emotions, negative emotions, and tourists’ behavioral intentions—are 0.894, 0.870, 0.859, 0.911, and 0.894, respectively. All coefficients exceed 0.8, demonstrating high reliability for each variable’s scale. Additionally, the combined reliability of each variable was calculated based on the factor loadings obtained from validated factor analysis, as shown in Table 3. The composite reliability values are 0.91, 0.93, 0.91, 0.94, and 0.93, respectively. Each value is above 0.60, confirming high composite reliability for each variable. In summary, the research data used in this study have been verified to possess high reliability, making them suitable for further analysis.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for each variable (n = 235).

Through confirmatory factor analysis, it was determined that the factor loadings for each variable item in the sample data range from 0.567 to 0.937. All values exceed 0.50, meeting the test criteria and indicating that each item effectively represents its corresponding latent variable. Additionally, the mean variance extracted (AVE) for each variable is greater than 0.50, demonstrating high construct validity. The square root of the AVE for each variable is also greater than the correlation coefficients between that variable and the other variables, confirming high discriminant validity among the variables.

5.3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses, including means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for the main variables, are summarized in Table 3. The findings reveal that: (1) Immersive physical experiencescape is significantly positively correlated with positive emotions (r = 0.66, p < 0.01) and tourists’ behavioral intentions (r = 0.66, p < 0.01), and significantly negatively correlated with negative emotions (r = −0.51, p < 0.01). (2) Immersive interpersonal experiencescape is significantly positively correlated with positive emotions (r = 0.71, p < 0.01) and tourists’ behavioral intentions (r = 0.66, p < 0.01), and significantly negatively correlated with negative emotions (r = −0.55, p < 0.01). (3) Positive emotions are significantly positively correlated with tourists’ behavioral intentions (r = 0.71, p < 0.01), while negative emotions are significantly negatively correlated with tourists’ behavioral intentions (r = −0.55, p < 0.01). These correlation patterns align with theoretical expectations, suggesting that the causal relationships among the variables warrant further investigation.

5.3.3. Hypothesis Testing Results

- (1)

- Immersive tourism experiencescape is significantly and positively related to tourists’ behavioral intentions.Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to test the research hypotheses. Control variables and independent variables were incorporated into the regression equation in a hierarchical manner, and the results are shown in Table 4 and Table 5. In models M6 and M6′, the regression coefficients for the independent variables, immersive physical experiencescape and immersive interpersonal experiencescape, with respect to the dependent variable, tourists’ behavioral intentions, are 0.744 and 0.727 (p < 0.001), respectively. These findings indicate that immersive tourism experiencescape has a significant positive effect on tourists’ behavioral intentions. After controlling for other variables, the independent variables were found to explain 50% and 49% of the variation in tourists’ behavioral intentions, respectively. Consequently, both hypotheses 1a and 1b are supported.

Table 4. Statistical results of hierarchical regression on immersive physical experiencescape, emotional experience, and tourists’ behavioral intentions (n = 235).

Table 4. Statistical results of hierarchical regression on immersive physical experiencescape, emotional experience, and tourists’ behavioral intentions (n = 235). Table 5. Statistical results of hierarchical regression on immersive interpersonal experiencescape, emotional experience, and tourists’ behavioral intentions (n = 235).

Table 5. Statistical results of hierarchical regression on immersive interpersonal experiencescape, emotional experience, and tourists’ behavioral intentions (n = 235). - (2)

- Immersive tourism experiencescape is significantly correlated with emotional experience.In models M2 and M2′, the regression coefficients for the independent variables, immersive physical experiencescape and immersive interpersonal experiencescape, with respect to the dependent variable, positive emotions, are 0.789 and 0.801 (p < 0.001), respectively. These results indicate that immersive tourism experiencescape has a significant positive effect on positive emotions. After controlling for other variables, the independent variables were found to explain 56% and 60% of the variance in positive emotions, respectively. Therefore, hypotheses 2a and 2b are supported. Similarly, in models M4 and M4′, the analysis reveals that immersive tourism experiencescape has a significant negative effect on negative emotions, thereby confirming hypotheses 2c and 2d.

- (3)

- Mediating effect of emotional experience.In model M7, when both immersive physical experiencescape and positive emotions were included in the regression equation, positive emotions were found to have a significant positive effect on tourists’ behavioral intentions ( = 0.51, p < 0.001). The effect of immersive physical experiencescape on tourists’ behavioral intentions remained significant, though the regression coefficient decreased from 0.74 to 0.34 (p < 0.001), indicating that while the direct effect was reduced, it was still significant. This suggests that positive emotions partially mediate the relationship between immersive physical experiencescape and tourists’ behavioral intentions. Similarly, the analysis indicates that:

- Positive emotions partially mediate the relationship between immersive interpersonal experiencescape and tourists’ behavioral intentions;

- Negative emotions partially mediate the relationship between immersive physical experiencescape and tourists’ behavioral intentions;

- Negative emotions partially mediate the relationship between immersive interpersonal experiencescape and tourists’ behavioral intentions.

To further assess the significance of the mediating effect, the bootstrapping method was used to extract 5000 times to test the mediating effect of emotional experience. The mediating effect is considered significant if the path coefficient does not include 0 within the 95% confidence interval. The results are presented in Table 6. The indirect effect coefficient of immersive physical experiencescape on tourists’ behavioral intentions through positive emotions is 0.31, with the 95% confidence interval ranging from [0.21, 0.42], which does not include 0. Therefore, the indirect effect is significant, partially verifying hypothesis 3a. Similarly, hypotheses 3b, 3c, and 3d are also partially verified. In summary, emotional experience plays a significant partial mediating role in the relationship between immersive tourism experiencescape and tourists’ behavioral intentions. Table 6. Significance test results for the mediating effect of emotional experience (bootstrapping = 5000).

Table 6. Significance test results for the mediating effect of emotional experience (bootstrapping = 5000).

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

As an emerging form of tourism, immersive tourism has garnered increasing global attention in recent years. With advances in technology and the diversification of tourist demands, traditional tourism models are no longer sufficient to fully meet the needs of modern travelers. Immersive tourism, by fully engaging the senses and emotions of tourists, creates a unique and compelling travel experience. The findings of this study provide valuable insights for the further theoretical and practical development of immersive tourism.

This study makes theoretical contributions to the research field. First, it enriches the theory of tourism experiencescape. The academic community typically categorizes experiencescape into six dimensions: sensory, functional, social, natural, cultural, and hospitality culture [57]. In tourism studies, tourscape is divided into four elements: atmosphere, social, social symbolism, and nature [27]. However, it remains unclear whether these dimensions apply to the emerging field of immersive tourism. Previous research has mainly focused on conventional tourism experiences, leaving the complexity of immersive tourism underexplored. This study, through empirical research, identifies two primary categories of immersive tourism experiencescape: physical and interpersonal experiencescape, each comprising different dimensions. This categorization not only aligns with the existing literature on the dimensions of tourism experiencescape but also enhances the emerging research on fully immersive tourism experience, thereby enriching the theoretical framework of tourism experiencescape.

Second, it expands the understanding of factors influencing tourists’ behavioral intentions. Traditional research has mainly focused on destination attributes [73], destination image [53], and perceived value [55] as key determinants of tourists’ behavior. However, this research demonstrates that immersive tourism experiencescape is also a significant influencer of tourists’ behavioral intentions. The impact largely depends on tourists’ perceptions of experiencescape. The design of physical spaces, the completeness of facilities, and the overall comfort of the environment are crucial factors shaping tourists’ emotional experience. Additionally, interpersonal interactions within the experiencescape, particularly deep engagement with thematic culture, significantly enhance the sense of immersion. These factors collectively contribute to emotional fluctuations during the experience, ultimately affecting tourists’ behavioral decisions. This study underscores the indispensable role of immersive tourism in modern tourism, particularly in enhancing overall tourist experience and fostering loyalty.

Third, it deepens the understanding of the mechanisms underlying immersive tourism experiencescape. Previous research has indicated that experiencescape, as a contextual condition, can be leveraged to create unforgettable experiences, thereby enhancing tourists’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions [62]. The findings of this study suggest that the experiencescape itself is a direct factor influencing tourists’ behavioral intentions. Further analysis reveals that emotional experience serves as a partial mediator between immersive tourism experiencescapes and tourists’ behavioral intentions. Consequently, this study proposes a model linking immersive tourism experiencescape, emotional experience, and tourists’ behavioral intentions, taking into account the differences between positive and negative emotions. Notably, the study also highlights the differing emotional triggers associated with physical and interpersonal experiencescape, a distinction uncovered through conversations with tourists. Physical experiencescape is more likely to evoke negative emotions, particularly when infrastructural deficiencies are present, leading to a noticeable drop in tourist satisfaction. In contrast, interpersonal experiencescape predominantly elicits positive emotions, such as a deeper cultural understanding and a sense of belonging, often fostered through interactions with in-situ actors (e.g., themed characters).

Fourth, this study provides a fresh perspective on promoting sustainable tourism by highlighting the critical role of immersive experiencescape. Traditionally, sustainable tourism has focused on external factors such as the role of residents, eco-labeling and the role of stakeholders [74]. However, this study emphasizes that sustainability in tourism must also prioritize the quality of the tourist experience itself. Without engaging and meaningful experiences, tourism cannot achieve true sustainability, as disinterested or dissatisfied tourists are less likely to return or recommend the destination, ultimately undermining long-term viability.

6.2. Practical Implications

Based on the findings of this study, there are several practical implications for the tourism industry: First, enhance the creation of immersive tourism destinations to elevate the overall tourism experience. As the tourism market evolves, the traditional resource-oriented tourism model is gradually being replaced by the era of scene tourism. Immersive tourism emphasizes attracting visitors through meticulously designed experiencescape that enhance their experience. When developing experiencescape, destinations should focus not only on utilizing natural resources but also on integrating physical and interpersonal elements to create unique and attractive experiences. This innovative approach can not only stimulate visitors’ desire to return and recommend the destination but also increase their willingness to pay a premium for high-quality experiences. Policymakers should consider establishing guidelines to support and encourage investment in scene creation at tourism destinations, particularly in areas such as infrastructure, technological interaction, and cultural presentation.

Second, define the core components of immersive tourism experiencescape and optimize visitor emotional management. The success of immersive tourism experiencescape depends on the coordinated operation of multiple dimensions. To enhance visitors’ emotional experience, tourism destinations should focus on three key aspects: creating the scene’s atmosphere, innovating tourism performances, and optimizing host-guest interaction. By strengthening these elements, destinations can better deliver emotional value, thereby influencing visitors’ behavioral intentions. Governments should implement relevant policies to promote the deep integration of the cultural and creative industries with tourism, providing visitors with rich and emotionally resonant experiences. Additionally, it is important to promote comprehensive visitor experience evaluation mechanisms, allowing for real-time adjustments and optimization of tourism product design through data collection and analysis.

Third, enhance tourists’ emotional experience by focusing on infrastructure and service quality. The success of immersive tourism destinations depends not only on creating attractive scenes but also on effectively managing visitors’ emotional experience. Research indicates that physical factors, such as infrastructure and environmental conditions, are significant contributors to negative visitor emotions, while interpersonal factors, such as service quality and interaction experiences, play a crucial role in enhancing positive emotions. Therefore, tourism destinations should improve and maintain their infrastructure, manage visitor capacity to avoid overcrowding, and mitigate negative emotions associated with congestion. Policymakers should also focus on the training and quality enhancement of tourism personnel, establish high service standards, and ensure that visitors receive excellent interactive experiences. Additionally, promoting a visitor-centered service philosophy and emphasizing the importance of responding to visitor feedback can further improve overall satisfaction and loyalty.

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Perspectives

This study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, the identification of immersive tourism experiencescape dimensions was based on the grounded theory qualitative research method, which can involve some degree of subjectivity. Second, the study focused solely on the mediating role of emotional experience in the relationship between immersive tourism experiencescape and tourists’ behavioral intentions. Future research should explore whether this relationship is also influenced by other internal and external factors. Lastly, this study was limited to a single case site in China, and the generalizability of the findings to immersive tourist destinations in other countries warrants further investigation.

7. Conclusions

This study, grounded in the dimensional construction of the immersive tourism experiencescape, explores the relationships between immersive tourism experiencescape, emotional experience, and tourists’ behavioral intentions, drawing on immersion theory, scene theory, and other relevant theories. Using a mixed-methods approach, the research elucidates the mechanisms through which the immersive tourism experiencescape influences tourists’ behavioral intentions. The findings underscore the critical role of immersion in the sustainable development of tourism. The main research results are as follows:

- (1)

- The immersive tourism experiencescape can be divided into two categories: physical and interpersonal. The immersive physical experiencescape consists of three dimensions: functional facilities, thematic atmosphere, and basic environment. Meanwhile, the immersive interpersonal experiencescape includes three dimensions: tourism performances, host-guest interaction, and personal service. While this classification shares some similarities with previous categorizations of experiencescape dimensions, it also presents key differences. Specifically, unlike experiencescapes in other contexts, the unique features of the immersive tourism experiencescape are primarily found in the dimensions of thematic atmosphere, tourism performances, and host-guest interaction.

- (2)

- The immersive tourism experiencescape has a significant positive impact on tourists’ behavioral intentions, with both physical and interpersonal experiencescapes contributing to this effect. This indicates that tourists’ perceptual evaluation of the experiencescape is crucial in the immersive tourism experience, influencing their willingness to recommend, revisit, and pay a premium. Additionally, emotional experience partially mediates the relationship between the immersive tourism experiencescape and tourists’ behavioral intentions, with both positive and negative emotions playing a partial mediating role.

- (3)

- The immersive tourism experiencescape has a significant positive effect on positive emotions and a significant negative effect on negative emotions. Conversations with tourists during the survey revealed that interpersonal elements, such as host-guest interaction, are particularly effective in stimulating positive emotions, whereas negative emotions are primarily triggered by physical elements, such as functional facilities and the basic environment.

- (4)

- Creating immersive experiencescape enhances the sustainable development of tourism. As tourism is an experience-based industry, improving the quality of the tourism experience is crucial for promoting sustainable development. This study confirmed that the immersive tourism experiencescape positively impacts tourists’ emotional experience, underscoring its vital role in advancing sustainable tourism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.Z. and X.W.; Data curation: M.Z.; Formal analysis: M.Z.; Funding acquisition and supervision: X.W.; Investigation: M.Z.; Methodology: M.Z.; Project administration: X.W.; Resources: X.W.; Software: M.Z.; Visualization: M.Z.; Validation: M.Z. and X.W.; Writing—original draft: M.Z.; Writing—review and editing: X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant [number 42071169]; and the Key R&D projects of Shaanxi Province in 2020 under Grant [number 2020ZDLGY10-08].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as the national law “Regulations for Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving Humans” does not require the full review process for data collection from adults who have adequate decision-making capacity to agree to participate.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Reviewers for taking the time and effort necessary to review the manuscript. We sincerely appreciate all valuable comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffi, G.; Cucculelli, M.; Masiero, L. Fostering tourism destination competitiveness in developing countries: The role of sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y. System Construction, Tourism Empowerment, and Community Participation: The Sustainable Way of Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde-Rodríguez, M.; Šadeikaitė, G.; García-Delgado, F.J. The Contribution of Tourism to Sustainable Rural Development in Peripheral Mining Spaces: The Riotinto Mining Basin (Andalusia, Spain). Sustainability 2024, 16, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Guerreiro, J.; Ali, F. 20 years of research on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism context: A text-mining approach. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranmer, E.E.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Fountoulaki, P. Exploring the value of augmented reality for tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Discombe, R.M.; Bird, J.M.; Kelly, A.; Blake, R.L.; Harris, D.J.; Vine, S.J. Effects of traditional and immersive video on anticipation in cricket: A temporal occlusion study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 58, 102088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Orús, C. Integrating virtual reality devices into the body: Effects of technological embodiment on customer engagement and behavioral intentions toward the destination. In Future of Tourism Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogicevic, V.; Seo, S.; Kandampully, J.A.; Liu, S.Q.; Rudd, N.A. Virtual reality presence as a preamble of tourism experience: The role of mental imagery. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Jiang, X.; Deng, N. Immersive technology: A meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, T.; Billing, P. Experiencescapes: Tourism, Culture and Economy; Copenhagen Business School Press DK: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Visualizing experiencescape–from the art of intangible cultural heritage. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Suntikul, W.; King, B. Constructing an intangible cultural heritage experiencescape: The case of the Feast of the Drunken Dragon (Macau). Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossgard, K.; Fredman, P. Dimensions in the nature-based tourism experiencescape: An explorative analysis. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 28, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeay, F.; Lichy, J.; Major, B. Co-creation of the ski-chalet community experiencescape. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantouvakis, A.; Gerou, A. The role of onboard experiencescape and social interaction in the formation of ferry passengers’ emotions. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2023, 22, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.Y.; Hågensen, A.M.S.; Kristiansen, H.S. Storytelling through experiencescape: Creating unique stories and extraordinary experiences in farm tourism. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.H.; Mossberg, L. Tour guides’ performance and tourists’ immersion: Facilitating consumer immersion by performing a guide plus role. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, V.; Jensen, Ø. Consumer immersion in the experiencescape of managed visitor attractions: The nature of the immersion process and the role of involvement. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wu, L.; Li, X.R. When art meets tech: The role of augmented reality in enhancing museum experiences and purchase intentions. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Petrick, J.F. Social interactions and intentions to revisit for agritourism service encounters. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, G.B.; McIntosh, A.J. Heritage buildings and tourism: An experiential view. J. Herit. Tour. 2007, 2, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernsand, E.M.; Kraff, H.; Mossberg, L. Tourism experience innovation through design. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Tsaur, S.H. Destination experiencescape for Hanfu tourism: An exploratory study. J. China Tour. Res. 2024, 20, 144–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H. The effects of tourscape and destination familiarity on tourists’ place attachment. Tour. Trib. 2023, 38, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrewal, S.; Simon, A.M.D.; Bech, S.; Bærentsen, K.B.; Forchammer, S. Defining immersion: Literature review and implications for research on. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 2019, 68, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. How to facilitate immersion in a consumption experience: Appropriation operations and service elements. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2006, 5, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.I.D.; Melissen, F.; Haggis-Burridge, M. Immersive experience framework: A Delphi approach. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 43, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, J.; Strijbosch, W. Experiencing tourism: Experiencing happiness? In Routledge Handbook of the Tourist Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N.H. The Laws of Emotion; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mcintosh, A.J.; Siggs, A. An exploration of the experiential nature of boutique accommodation. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Deesilatham, S.; Cauševic, S.; Odeh, K. Measuring tourists’ emotional experiences: Further validation of the destination emotion scale. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Gilbert, D. Measuring tourists’ emotional experiences toward hedonic holiday destinations. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.W.; Wang, Y.; Han, T.Y.; Zhang, K. Exploring the effect of “home feeling” on the online rating of homestays: A three-dimensional perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 182–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ye, C.; Yang, H.; Ye, P.; Xie, Y.; Ding, Z. Exploring the impact of seasonal forest landscapes on tourist emotions using Machine learning. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrom, J.; Light, D.; Medway, D.; Parker, C.; Zenker, S. Post-holiday memory work: Everyday encounters with fridge magnets. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 105, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. On the Essence of Tourism. Tour. Trib. 2014, 29, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Danping, L.; Chen, J. A Review of the Studies of Emotions in Tourism. Tour. Sci. 2015, 29, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R.; Ruffolo, I. Exploring the relationship between emotions and memorable tourism experiences through narratives. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrín-Borondo, J.; Juaneda-Ayensa, E.; González-Menorca, L.; González-Menorca, C. Dimensions and basic emotions: A complementary approach to the emotions produced to tourists by the hotel. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 21, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rojas, C.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, K.; Cao, Y.; Qiao, G.; Li, W. Glamping: An exploration of emotional energy and flow experiences in interaction rituals. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 48, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Huang, A.; Huang, J. Influence of sensory experiences on tourists’ emotions, destination memories, and loyalty. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Fu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L. Consumers’ perceptions, purchase intention, and willingness to pay a premium price for safe vegetables: A case study of Beijing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Guo, W.; Xiao, X.; Yan, M. The relationship between tour guide humor and tourists’ behavior intention: A cross-level analysis. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1478–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Liu, B. Does distance produce beauty? The impact of cognitive distance on tourists’ behavior intentions: An intergenerational difference perspective. Tour. Trib. 2023, 38, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; da Silva, R.V.; Antova, S. Image, satisfaction, destination and product post-visit behaviours: How do they relate in emerging destinations? Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.Y.; Bi, J.W.; Wei, Z.H.; Yao, Y. Visual cues and consumer’s booking intention in P2P accommodation: Exploring the role of social and emotional signals from hosts’ profile photos. Tour. Manag. 2024, 102, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Liu, R.; Ouyang, C.; Yanju, J. Research on the Relationship between Tourists’ Perceived Value and Behavioral Intention—Based on the Perspective of B&B Tourists. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2020, 1, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Lin, B. The Path of Tourist Guide Humor on Tourist Behavioral Intention-Based on Affective Event Theory. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Tasci, A.D. Experienscape: Expanding the concept of servicescape with a multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary approach (invited paper for ‘luminaries’ special issue of International Journal of Hospitality Management). Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Liu, M.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, S. Effects of creative atmosphere on tourists’ post-experience behaviors in creative tourism: The mediation roles of tourist inspiration and place attachment. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 25, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Huang, X.B.; Zhang, M. Is immersion enough? Research on the influence of flow experience and meaningful experience on tourist satisfaction in tourism performing arts. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P.; Morvillo, A.; Okumus, F.; van Niekerk, M. Managing the experience co-creation process in tourism destinations: Empirical findings from Naples. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, C.T.B.; Rahim, F.A.; Hassan, F.H.; Musa, R.; Yusof, J.M.; Hashim, R.H. Exploring tourist experiencescape and servicescape at taman negara (national park malaysia). Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2010, 1, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piramanayagam, S.; Sud, S.; Seal, P.P. Relationship between tourists’ local food experiencescape, satisfaction and behavioural intention. In Tourism in India; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, W.Q.; Jiang, G.X.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, S.N. Night tourscape: Structural dimensions and experiential effects. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Ma, E. Travel during holidays in China: Crowding’s impacts on tourists’ positive and negative affect and satisfactions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H.; Chaozhi, Z. Does Crowding Arouse Tourists’ Negative Affect? An Empirical Research in the Context of Watch-ing the Sunrise on Mount Tai. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2024, 27, 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Implications for Research, Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention. In Emotion And Adaptation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, J.; Rosen, C.C.; Gabriel, A.S.; Puranik, H.; Johnson, R.E.; Ferris, D.L. Why and for whom does the pressure to help hurt others? Affective and cognitive mechanisms linking helping pressure to workplace deviance. Pers. Psychol. 2020, 73, 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, H.; Ziya, Z.; Yaoqi, L.; Jun, L. A Research on the Influence of Residents’Perceived Value on the Support Behavior of Wellness Tourism:Based on the Perspective of Emotion Appraisal Theory. Tour. Sci. 2022, 36, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, L.; Qinhai, M.; Xiaoyu, Z. A review of researches on servicescape and future prospects. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2013, 35, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, F. A study on the relationships of service fairness, consumption emotions and tourist loyalty: A case study of rural tourists. Geogr. Res. 2011, 30, 463–476. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, L.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y. Revision of the positive affect and negative affect scale. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 14, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Yang, X.; Xie, H. The impacts of mountain campsite attributes on tourists’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions: The mediating role of experience quality. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 32, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.; Jain, A. Sustainable tourism and its future research directions: A bibliometric analysis of twenty-five years of research. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 541–567. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).