Abstract

The climate crisis is both an environmental and moral issue. The United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a framework for a global response to systematically challenge the world’s reactions to the climate crisis, making sustainable education for all a priority. For such sustainability education to be effective, it should engage children in early childhood in, about, and for the environment, emphasizing the moral ramifications of climate equity and justice. We investigated in what ways 19 United States (US) nature-based early childhood educators focused their sustainability education (ECEfS) in, about, and for the environment. The types of activities that engaged about and for experiences were related to the moral principles of welfare, harm reduction, resource allocation, and equality, as well as teachers’ reasoning about these experiences with children. Our findings suggest that educators’ curricula and activities reflect potential moral issues related to sustainable development. However, educators did not engage children in moral reasoning about these issues. A possible explanation is US teachers’ beliefs about developmental practice and children’s capabilities leading them to rarely engage in moral reasoning about sustainability issues instead of scaffolding children to develop personal psychological resources, thereby supporting the SDG for sustainable education.

1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainable Development Goals and Early Childhood Education

The anthropogenic climate crisis was caused by and continues to contribute to social inequities [1], making climate change a moral issue to be addressed by current and future generations. The United Nations (UN) seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a framework for a global response to systematically challenge the world’s reactions to the climate crisis in order to ensure “a just, sustainable, prosperous future” (UN Website) that includes reducing inequalities (SDG 10), creating sustainable communities and cities (SDG11), responsible consumption (SDG 12) and taking climate action (SDG 14). One goal in particular, SDG 4, inclusive and equitable quality education for all, informs the roadmap of sustainable development for future generations, as quality education can, and should, include teaching sustainability to children, including how to reduce inequalities, create and reinforce sustainable classrooms and communities, consume responsibly, and take climate action. These are all necessary because, as the UN notes, SDG 4 “is a pivotal driver for positive change, emphasizing the transformative power of education in fostering a sustainable and equitable world”.

However, the UN’s call for inclusive and equitable education for all is not without critique within the context of transnational education. Mochizuki and Vickers [2] note that within SDC 4.7, which focuses on “knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development” the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) encounters two major tensions within the current educational context: the relentless focus on educational metrics and the pursuit of skills, and the role of human exceptionalism in questioning assumptions of humanistic education. Furthermore, UNESCO’s educational interventions do not confront the dominant cultural and structural forces that make meaningful sustainability responses applicable [3]. In some cases, sustainability education can promote or reinforce a country’s transnational norms and epistemic regimes depending on whether or not the country has “de-politicized” or “decolonized” sustainability education [4,5,6]. In other cases, the very “loose” definitions and measurement of sustainability education ensure that changes occur on local levels rather than addressing the “need for a system-level transformation” (p. 732) [7].

Despite the limitations of UNESCO, the global need for equitable, sustainable education is undeniable. The enactment of transformative sustainable education, however, is likely to be influenced by the historical context, understandings of human rights, and responses to human exceptionalism, colonialism, and the role of the country/state/locality in global climate inequality [8]. From a global perspective, then, we must highlight that this article focuses on sustainability education in the context of the northeastern United States in early childhood education settings (pre-K-3; ages 3–9) that identify as “nature-based”, an educational approach that engages children with the natural environment (in both natural and man-made settings) as a pathway for learning. These programs include a large amount of time spent outside, learning about, and through, the natural world, but also may include social emotion, pre-literacy, and pre-mathematical instruction [9]. However, we firmly believe that the approaches outlined in this paper have the potential to be applicable and beneficial in any US early childhood setting.

We focus on early childhood education (pre-K-3; ages 3–9) because sustainability education must start early. Climate change significantly risks children’s prenatal development [10]. From delayed cognitive development and psychological distress [11] to increasing global temperatures and the displacement of families caused by extreme weather events and lack of resources [12], children will overwhelmingly bear the impact of climate change. These effects are not only socioemotional; the World Health Organization also predicts that children will suffer the majority of illnesses and deaths from the climate crisis. Children will need support in transitioning this hopelessness into hope [13,14]. In the United States (US), early childhood education programs can provide young children with opportunities to develop their reasoning about environmental justice inequities and provide them with coping strategies through discussion of not only the issues at large but also what they can do as individuals and community to become agents of change. Research from the US suggests that young children view environmental harm as a moral issue [15] and can condemn everyday community-accepted actions if they hurt the environment [16]. Thus, these studies suggest that young children consider environmental degradation separate from rules and individual decisions. More so, these views need to be supported, and more complex thinking should be scaffolded, as moral views are pliable and diminish over time [17]. Supporting children’s views of environmental harm as a moral violation and scaffolding of young children’s moral thinking is necessary to ensure continued complex and moral reasoning about the environment, which can occur in certain aspects of sustainability education. That is, early childhood education in the US can contribute to the specific goals of SDGs, as mentioned above, and support the UN’s socioeconomic and educational goals.

1.2. Education for Sustainability

Education for Sustainability (EfS) [18] is an educational approach that utilizes multiple pedagogies, including place-based, inquiry-based, and project-based learning. EfS aims to “help students develop a knowledge base about the environment, the economy, and society. It helps students learn skills, perspectives, and values that guide and motivate them to seek sustainable livelihoods, participate in a democratic society, and live in a sustainable manner” [19]. Because EfS focuses on helping children understand the interconnectedness of the environment, the economy, and society, and it connects that knowledge to inquiry and action, EfS reflects the UN’s SDGs for cultivating a just world. This educational approach is not limited to older children; as young children develop the capacities of reasoning and foundational patterns of interactions with environmental sustainability mindsets, action patterns can be established [20,21]. Children can learn to be “problem solvers and solution seekers in relation to their social and environmental issues and topics in relation to meaning in their local contexts” (p. 21) [22]. Thus, sustainability education must occur in early childhood settings, as it directly reflects SDG goal 4.2 (“By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care, and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education”) and SDG 4.7 (“ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyle”).

Early Childhood Education for Sustainability (ECEfS) [21] provides children with opportunities to become agents of change at the individual and community level through a framework that “requires a deep understanding of ourselves, our neighbors, our societal and cultural processes and how we are connected” (p. 6) [23] by spending time in nature (in the environment), learning about human and nonhuman relationships (about the environment), and intentionally making sustainable lifestyle choices and understanding the social and economic inequities that make sustainable development difficult (for the environment).

Education in the environment provides children with direct access to nature and allows them to develop positive feelings toward it [24]. Research from the past twenty years suggests that these positive feelings help young children learn to love and care for the Earth [13,25], and over time, this love and care for the Earth leads to pro-environmental behaviors, often in adulthood [26,27,28]. Although children benefit from spending time in nature, to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change, children must also understand relationships within nature and how these relationships work with and are impacted by humans and human systems. Education about the environment goes beyond teaching children facts about nature. Instead, it creates literacy about how people and societies relate to each other and to natural systems and how to engage in these relationships sustainably [29,30,31].

Unfortunately, most environmental education programs have approached education about the environment from a top-down approach, focusing on scientific knowledge of the environment rather than on the interconnectedness of environmental systems [32]. However, there are pedagogical approaches that engage children in holistic scientific knowledge that move beyond facts to impact children’s environmental attitudes and behaviors. For example, many Nordic countries use a holistic approach that includes environmental education’s ecological, economic, and social components [33]. These holistic approaches have been found to influence children’s attitudes toward climate change [34] and foster their willingness to act [35].

While education in the environment focuses on learning to love and care for the Earth and education about the environment explores the interrelatedness and connections among humans and ecosystems, neither focuses on climate action. For climate mitigation to occur, young children must also learn how to intentionally take local action towards sustainable lifestyle choices and begin to understand the social and economic issues that make sustainable development ‘tricky’. Davis [21] refers to this as education for the environment; she identifies this approach as focusing on social assessment and action for change. In preschools, this would mean that children identify local problems and act on solutions, explaining why these actions are necessary. One potential way to do this is to have educators support young children in developing moral reasoning related to sustainability.

1.3. Developing Moral Reasoning for Sustainability

Climate change is a moral issue as it involves principles of fairness (resource allocation), welfare (caring about other humans and the more-than-human world), harm reduction (changing behaviors that harm others and the more-than-human world), and equality (justice) [36]. Moreover, moral reasoning about sustainability can highlight inequities, such as those found with climate change (in)justice. Children can view the environment as having moral standing [37,38,39], reward and prefer children who act in pro-environmental behaviors over those who engage in environmental destruction [40,41], and identify that environmentally harmful behaviors are wrong, even if such behaviors are acceptable in the local community, such as polluting a waterway [38,42] and recycling [43]. The sophistication of moral reasoning children engage in, from the concrete identifying physical harm to the more abstract unfairness, increases from early childhood to middle childhood [44]. Still, younger children’s ability to morally reason at more sophisticated levels can be encouraged through perspective-taking activities [15]. Thus, children can morally reason about the environment at a young age, although the sophistication of moral reasoning depends on age and provided experiences.

Although less studied, moral reasoning in adolescence and young adulthood is influenced by age and experiences, including cultural context and nature connection. For example, Kahn and Lourenco [38] found that Portuguese students’ moral reasoning of environmental dilemmas became more biocentric (an appeal to the moral standing of an ecological community of which humans may be a part) and less anthropocentric (an appeal to how affecting the environment affects human beings), as the ages of children (from grades 5, 8, 11, and college) increased. However, they also found that while children’s moral justifications were similar across three contexts—Portugal, US, and the Amazon—5th-grade children from the US and Amazon engaged in biocentric reasoning less often (4% and 6%, respectively, compared to 16% in Portugal), suggesting that cultural context and time spent in nature, as well as age, influence how children morally reason about the environment. More recent research in adolescence has supported these findings; Kretten [17] found that US adolescents identified pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling and waste reduction as moral, but less so for energy consumption, a controversial topic in the US, and that connection to nature was a mediating factor; adolescents with a lower connection to nature viewed pro-environmental actions as personal rather than moral choices. Thus, although moral reasoning develops over time, it is influenced by cultural expectations and personal experiences, making moral reasoning about the environment malleable and potentially teachable.

Killen and Dahl [45] argue that the development of moral reasoning enables changes to occur on a societal scale because the realization that society may be unfair is related to the motivation to seek change. Reasoning and judgments related to moral principles elicit emotions and motivate actions, such as rectifying inequities or protesting unfair norms or rules, even in young children [46,47]. Thus, early childhood sustainability education focusing on moral reasoning may facilitate positive change in the local context now and in the future, as reasoning about moral dilemmas spurs age-related changes from childhood into adulthood [45], supporting SDG goals.

Promoting moral reasoning in early childhood can be tricky as it, by necessity, highlights inequities, which can lead to hopelessness. With the proper support, however, children can utilize their thinking to take local action, transforming hopelessness into hope [13,48,49]. One way to do this is by strengthening children’s personal psychological resources [50], which include having children engage in meaning-focused coping activities when discussing sustainability issues and engage in moral reasoning through caring and empathy; both strategies have been identified as precursors to pro-environmental behavior. Meaning-focused coping involves reflecting on the meaning and benefits of a difficult situation, which engenders positive emotions and has been identified as a potential mechanism between living a sustainable lifestyle and wellbeing [13,51,52]. Another way children engage in meaning-focused coping is through local, sustainable actions, such as recycling, to reduce resource inequity, which makes the action meaningful when framed as a moral choice [53,54,55]. Helping children develop empathy and caring towards the more-than-human world, helping children identify these concepts as related to the moral issues of fairness and harm, and discussing how to solve these moral dilemmas are related to pro-environmental intentions, values, and attitudes in children [50]. The key to developing psychological resources is to help children go beyond discussing the negative impact of climate change or environmental knowledge to identify the moral issues, such as fairness (resource allocation), welfare, harm reduction, and justice involved in the dilemma, and help children identify and take small, positive local actions towards remedying the inequalities.

1.4. Current Study

While it may seem more convenient to cultivate love and care for the environment in children rather than actively involving them in problem-solving about sustainability challenges, it is important to remember the ultimate goal. As Ahi and Balci [56] note, young children often do not think about the environment in complex ways on their own. Therefore, it is crucial that complex ecological concepts are directly incorporated into early childhood education programs. This approach should focus on developing children’s agency, as it is a necessary factor for children to engage in education for the environment.

As moral reasoning enables developmental and societal change [45], we investigated in what ways teachers focused on, about, and for the environment; in what types of activities for and about experiences were manifest, and how the teachers reasoned about these experiences with children. We believe that moral reasoning is vital for sustainability education and sustainable development, that is, for people to make sustainable lifestyle choices and understand the inequities that make sustainable development difficult. How teachers reason about experiences with students is critical in helping children focus on social assessment and moral reasoning. Following Ilten-Gee and Manchanda [57], we utilized Social Domain Theory [58] to determine how nature-based educators approach sustainability, including how they help children navigate social-justice-based environmental dilemmas in their everyday classrooms.

Early childhood educators (grades pre-K to 3 in the United States) can help facilitate these moral conversations in their programs. Thus, our research focuses on the following questions: How do nature-based educators approach sustainability, and how do they help children navigate the social-justice-based environmental dilemmas they encounter in their classrooms? Specifically, we were interested in the following: (1) On what activity topics do nature-based early childhood educators focus their curriculum, and with what moral principles is the curriculum associated? Moreover, (2) how do nature-based early childhood educators explain their reasoning with the children (or the researchers) about these shared experiences?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Early Childhood Education Programs

Participants were drawn from nine nature-based early childhood education programs, all within a sixty-mile radius (97 km) in a centralized area of Massachusetts, USA. The programs ranged from forest schools, which spent all day outdoors in the forest, to nature-based schools located in an urban area with a courtyard, which took field trips to forests. All but three were full-day programs; two were located within public charter schools, while the other seven were private and tuition-based. Six programs were located outside of cities or based in rural or forest locations near small towns, and three were located in urbanized areas within city limits. Three of the schools (all urbanized areas) reported that students of color made up at least 25% of their schools’ population. See Table 1 and Table 2 for early childhood education program demographics.

Table 1.

Nature-Based Early Childhood Education Program Demographics.

Table 2.

Participant Demographics.

In 2018, we interviewed 19 participants (89% White and 100% female); 17 were nature-based early childhood teachers, and two were administrators at these centers. The teachers, administrators, and their programs reflected the US national demographics for early childhood educators: 97.3% are women, and approximately 68% are white [59]. The early childhood programs were predominantly private (n = 7), and participants in our study had equivalent experience teaching and similar levels of formal education as educators in the US nature-based early childhood programs [60]. Across the schools, the total number of teachers at each school who taught early childhood ranged from 6 to 13 lead teachers, with the gender make-up of those teachers ranging from 78% to 100% female.

2.2. Analytic Design and Data Analysis

Smith College Institutional Review Board (IRB # 1718-060, approval date March 1st, 2018) approved this study. First, we identified nature-based education centers within a 60-mile (97 km) radius of the university via comprehensive internet searches using keywords such as ‘nature-based education programs’ and ‘forest preschools’. We identified 23 programs (alone-early-childhood programs and elementary schools with early childhood programs). One author emailed the administrators of all 23 programs, and within a month, 17 responded by providing the names and email addresses of early childhood educators in their programs so we could contact them directly. The same author emailed all educators who taught in the nature-based classrooms as the lead teacher, and within two months, 19 educators indicated their willingness to participate. All participants gave written consent for their participation, per IRB protocol, and were interviewed face-to-face. One author arranged and completed individual (ten) or group interviews (three interviews ranging from 3–5 participants from the same school) [61]. The choice of individual and group interviews was deliberate, aiming to highlight teachers’ personal and shared views and reflections on their teaching of sustainability education within the early childhood setting.

Individual and group interviews occurred at the participants’ schools and ranged between 45 and 95 min. Schools with more than one participant participated in group interviews. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, as indicated on the consent form, by one author, who then emailed the participants so they could make comments or changes, a process known as member checking [62]. The interviews focused on three main questions: (1) How do teachers engage in sustainability education in their early childhood settings, and what are common reactions from the children? (2) What about sustainability education in your classroom encourages you to continue this work? (3) What are the facilitators and barriers to sustainability education with young children?

In order to further increase the validity of our findings, we triangulated [63] a subsample of participant interviews with classroom observations along with documents, including lesson plans and center policies and procedures from all participants that reported on them [64]. We used these artifacts to verify the validity of the teachers’ descriptions of their class activities and programs. However, we do not use these artifacts in our coding analysis. We did not receive IRB permission to share teacher lesson plans or recorded observations in our findings due to teacher intellectual property and child privacy rules expected in the US. In addition, we could not include center policies and procedures because this information could be used with our tables to identify the specific early child centers and participants in this study. In order to ensure proper bracketing, which mitigates the effects of preconceptions that may taint the research process [65], the authors collaborated in study design, codebook creation, and interview analyses [66]. We initially read and organized the interview transcripts using a first-pass approach [67]. We organized our codes into three key analysis areas within Davis’ [21] sustainability education differentiation among in, about, and for the environment. See Table 3 for definitions and examples. Another researcher checked thirty percent of the coding to ensure coding accuracy.

Table 3.

Definitions and examples of coding for types of sustainability education.

After the initial sorting pass, we coded the interview sections categorized as either about the environment or for the environment using an open coding procedure, followed by axial coding [68,69] to determine the activities covered. Once we determined the activity topic (e.g., water rights, sharing toys), we organized the topics into themes. Next, we categorized each topic under an existing moral principle within a social domain theory framework (SD; e.g., fairness, resource allocation) [36] following Killen and Dahl’s [45] definition of moral principle—as prescriptive principles concerning others’ welfare, rights, equality, fairness, and justice. See Table 4 for definitions and examples. Finally, we assessed teachers’ explanations of experiences aligned with the previous categories’ activities, including pedagogical choices about how the topic is framed and explained to children, using thematic coding [67]. Researchers collaborated to increase the validity of analyses; all disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Table 4.

Definitions and examples of coding for types of moral principles.

3. Results

3.1. Aim 1: Activity Topics and Moral Principles

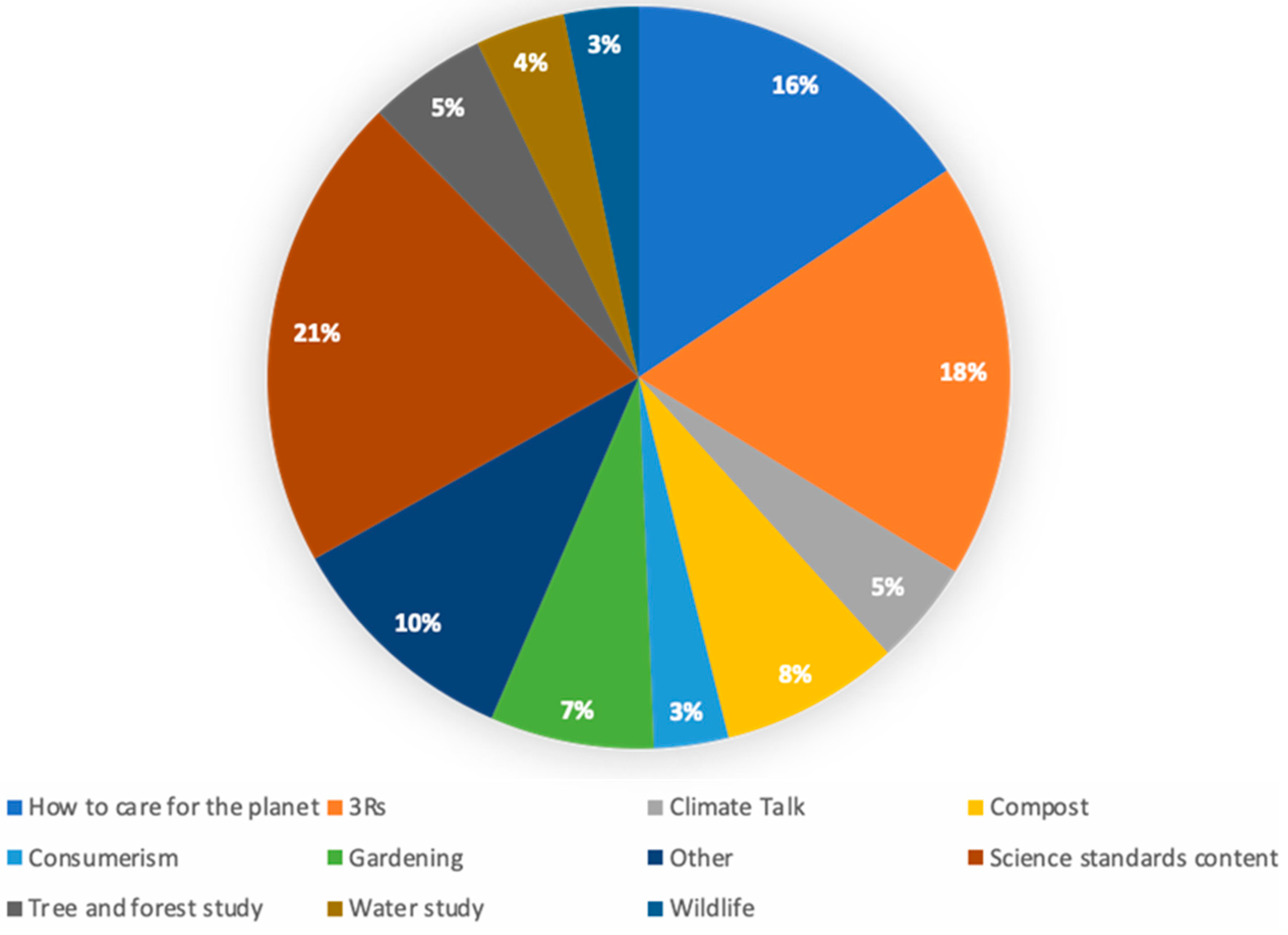

From the interviews, we identified 237 codable sections: 35.4% of codable interview sections were identified as “in” the environment (n = 84), 33.3% of codable interview sections were identified as “about” the environment (n = 79), and 31.6% of codable interview sections were identified as “for” the environment (n = 75). Next, we coded for activities and content from the ‘about’ and ‘for’ the environment sections. We identified 154 topics which we organized into the following 11 themes: how to care for the planet (n = 24), gardening (growing food, flowers, and butterflies; n = 11), science standards content (engineering and design, problem-solving, Earth science; n = 32), tree and forest study (n = 8), water study (n = 6), wildlife (care and sanctuary; n = 5), compost (n = 12), 3Rs (we want to acknowledge that there are 5r’s—refuse, reduce, reuse, repurpose, and recycle—that are now commonly used, but the teachers in our study only discussed the 3Rs) (reduce, reuse, recycle, including zero waste lunch; n = 28), consumerism (n = 5), climate talk (n = 7), and other (miscellaneous; n = 16). See Figure 1 for percentages of these themes. Because the topic/activity code (such as teaching about water pollution) is a more precise indicator than the general themes of the topics covered, we categorized the individual topic areas into four underlying moral principles, including fairness/resource allocation (How are resources allocated between individuals or communities?), equality (Is everyone getting what they need?), harm reduction (Are we minimizing the harmful effects of our behavior?) and welfare (How do we consider and account for the wellbeing of those around us?). Some topics aligned with more than one moral principle (for example, learning about butterflies was meant to teach children about resource allocation and help them develop empathy towards non-humans (welfare)), so the number of topics and the number of moral principles coded may not align. Most topic and content areas were not associated with moral principles (n = 55), and most of these topics fell within the theme of science standards and content. As one teacher noted, “A lot of the geology and geography lessons are based in Earth science, but we don’t do anything really about environmental justice”. The most common moral principle that preschool teachers directly engaged with the children was harm reduction (n = 55), with teachers focusing on composting, zero waste lunches, recycling, and reusing materials. One teacher noted, “Just showing the kids the possibility of reducing and reusing, for example using cloth instead of paper. I just think if they grow up knowing how to do that, then they are more likely to choose that as adults”. Teachers indirectly engaged with the moral principle of welfare (n = 31) by discussing how activities helped develop empathy and care, emotions that would be necessary for protecting and caring for the Earth later in life. For example, teachers commonly reported, “especially with the butterfly gardens, what we’re talking about essentially, is that if we don’t protect the Earth, these insects will not be around anymore”. Teachers also engaged the principles of fairness/resource allocation (n = 29), which often overlapped with welfare. For example, one teacher noted:

“We do a lot of very physical lessons where we talk about how the butterfly needs to eat these leaves, and get these healthy plants, and then come out and if we’re destroying the habitat then there’s no food for them. And, I feel like the kids are very empathetic… They’re like, ‘oh my gosh we need to save them.’ So, I just feel like it’s really teaching them empathy”.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of themes found in “about” and “for” the environment.

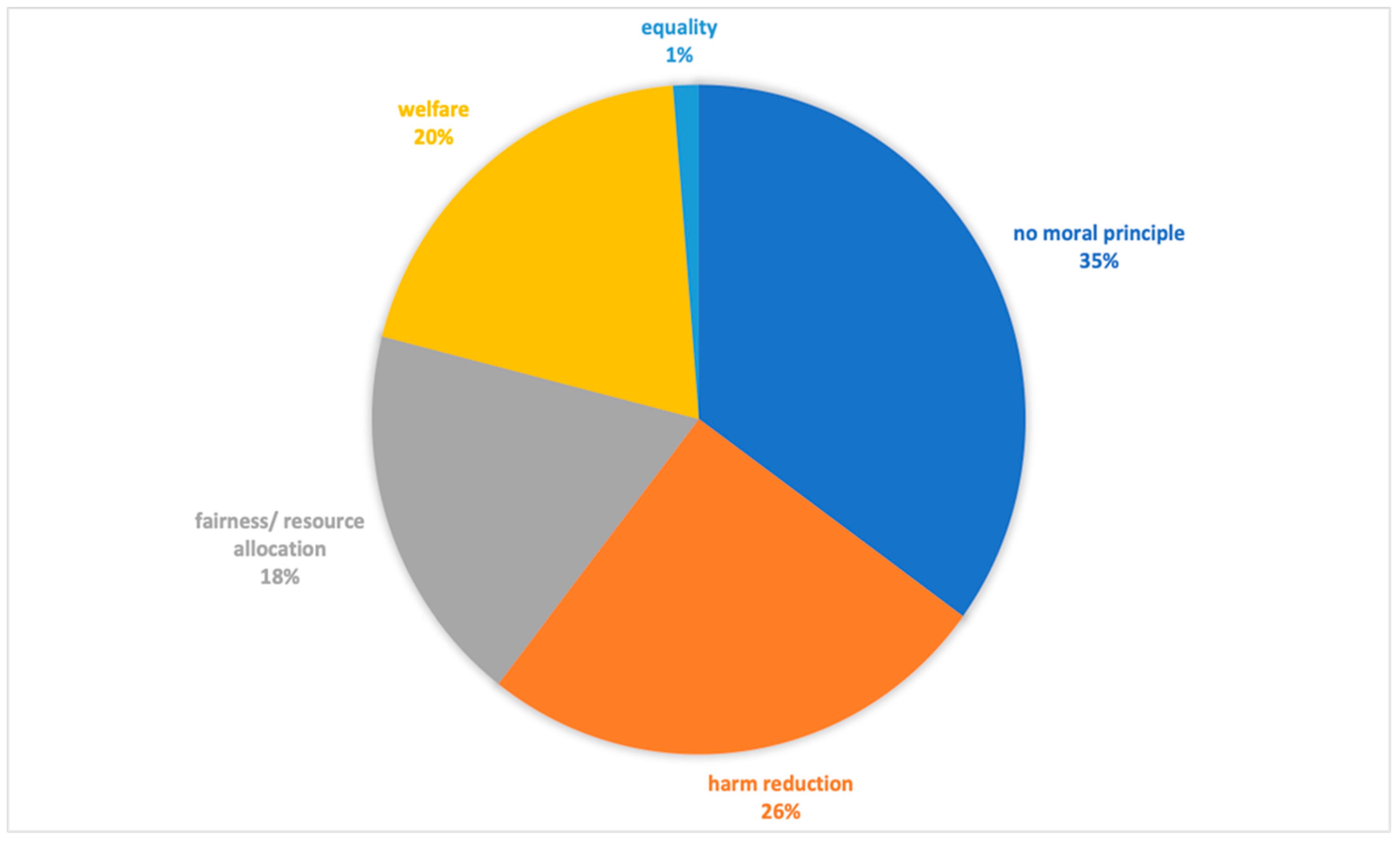

Very few activities or content were related to the moral principles of equality (n = 2), with one teacher reporting that she ran an income equality workshop for the older range of students (grades 1–3; ages 6–8). There were no equality-related activities from educators who worked in pre-k to K (ages 3–5). See Figure 2 for a breakdown of the moral principles.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of moral principles identified in “about” and “for” the environment.

3.2. Aim 2: Moral Reasoning

Our second aim was to broadly understand how teachers engaged students in direct questions and conversations about these underlying moral principles and how teachers supported and scaffolded students’ reasoning in the moral principles related to sustainability education. To do this, we returned to the data. We analyzed the sections of the interviews where we had coded the presence of moral principles to understand better how teachers engaged students to think about or act in alignment with these principles. We found that teachers gave five common responses when asked how they responded to children’s complex questions or interactions that arose within these activities. First, they “provided factual information” (19 of 19 educators), such as how water filtration worked or how butterflies get nectar from flowers. Second, they used what we called “sleight of hand” (11 of 19 educators) to dismiss moral and environmental issues when they arose, such as ending a discussion about water as a limited resource with a suggestion to “do a rain dance” to get more rain. Third, teachers often did what we called “obscuring inequity” (13 of 19 educators) to prevent the judgment of others who had more resources or feelings of shame from children who had access to resources. This theme also included getting rid of the zero-trash lunch program because some children’s families “could only afford packaged food” and children would feel “shame” that their lunch included packaging that must be thrown away. This approach focuses on individual children’s needs rather than helping the children think collectively. For example, from a sustainability standpoint, it is better to have most children in the class have zero-waste lunches than not having anyone do it. Fourth, teachers responded by doing “nothing” (19 of 19 educators) when difficult questions arose—they did not provide reasoning for the actions they asked the children to engage in. They often talked about composting and how to compost, but not why to compost. Several schools had zero-waste lunch policies, but the teachers never explained to the children why they were engaging in the activities. Educators reported that they chose not to engage children in these moral issues because “sustainability issues are too intense for young children to deal with”. The teachers reported believing that young children had limited cognitive and emotional capabilities and therefore they could not engage with children on moral principles because “the issues are too hard for young children to understand”. A common refrain was that the children could not engage in sustainability now but that they were laying the groundwork for the children to engage in sustainability behaviors in the future—as one participant noted, “It’s laying the groundwork for work that’s going to happen when they get a little older”.

Finally, the few instances where teachers discussed the moral implications of an issue were labeled as “shame-reduction” (five of 19 educators) as often the discussions led children to feel bad about themselves and their behaviors, and positive action was downplayed rather than encouraged, to reduce children’s negative emotions. For example, a teacher told us about a discussion she had with her students about the use of glitter in the classroom.

The kids wanted glitter this year, and there’s a couple reasons why we don’t use glitter any more as a program, but one of the reasons is because of learning about the damage that it does to the oceans. As much as we love it, we did talk to the kids about glitter in the oceans, and they got really upset about it, and they started saying, ‘oh my gosh, I have glitter at home! I should throw it away!’ And I was like, ‘well, I mean, use it first, and then just don’t buy anymore.’ But then we also talked about how everyone’s family makes the decisions that they make, because we didn’t want to have a shame thing happening because of it either. But it was interesting because some of the kids got really upset like, ‘oh my gosh I have to tell my parents, we shouldn’t use our glitter glue anymore.’

There was the potential to encourage the kids to think about the harm of glitter on a local level and help the children engage in positive actions, such as not using the glitter, as the children were motivated to enact change through their emotions. However, the teacher did not scaffold children to use their psychological resources, such as highlighting that it was important for them to care so much about this issue and suggesting positive action, such as having the kids encourage others in their school not to use glitter.

4. Discussion

As the climate crisis continues, there is increasing awareness that there is no time to wait; young children need to engage in sustainable development now. The UN’s seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a framework for how to do this: SDG 4—inclusive and equitable quality sustainable education for all—which includes reducing inequalities, creating sustainable classrooms, consuming responsibly, and taking climate action—enacted through Early Childhood Education for Sustainability (ECEfS)—can provide a road map of the different ways that teachers should engage young children in sustainability education in, about, and for the environment. However, engaging children in sustainability education is not enough; climate change is also a moral issue, and as such, children need to learn how to morally reason about climate change, as moral reasoning leads to societal change within a lifetime [45]. How can teachers do this?

The present study examined how a group of nature-based early childhood educators in a specific area of the US approached sustainability education, including the following questions: (1) What activity topics do nature-based preschool teachers focus on and with what moral principles is the curriculum associated? (2) How do nature-based preschool teachers explain their reasoning with the children (or the researchers) about these shared experiences? The answers to these questions are essential for implementing Sustainable Development Goals, as moral reasoning is pivotal for sustainable development, given that it helps individuals recognize the inequalities that impede sustainable progress. We will first discuss the results for the first question, followed by the second question, and provide suggestions for how to help early childhood educators promote inclusive and equitable quality sustainable education for all (SDG 4).

4.1. Topics and Moral Principles in ECEfS

Our study found that most activities and topics were not related to moral principles; instead, they focused on content, such as science standards. This finding is not surprising, as early childhood educators in the United States often report pressure to focus on academic content, which often requires rigidity in lesson planning and activities [70], leaving little room for the moral implications of sustainable development.

The most common moral principle educators engaged with was the principle of harm reduction (Are we minimizing the harmful effects of our behavior?). This finding was not surprising, as early childhood educators intentionally engage children with reminders about behaviors and how these behaviors affect others, often through social and emotional learning principles [71] and perspective-taking, which is a skill young children are developing [72]. More so, research suggests that children as young as three can identify and judge behaviors that harm the environment and that their views on moral harm become more nuanced as they age [15]. Children’s moral reasoning about harm also depends on the target of environmental harm, with more negative judgments occurring against harm to animals, ‘victimless’ harm, such as recycling, followed by plants [43]. Thus, it seems harm reduction is a moral principle that aligns with teachers’ goals for behaviors and children’s cognitive reasoning, potentially making it an effective principle under which to reason morally about environmental harm. The specific topics and activities that fell under this principle in our study involved the ‘victimless’ behaviors such as reducing waste, reusing materials, recycling, composting, and having children engage in zero-waste lunches, all of which are environmental issues typically addressed in school contexts.

When confronted by welfare issues, such as caring for wildlife, water, and the environment, teachers in our study encouraged children to develop empathy, as they believed this to be a precursor to sustainable actions. Although empathy is itself a positive moral emotion and could be a motivation to take action [73], research suggests that it is the combination of high levels of empathy with negative moral emotions, such as guilt, that leads to pro-environmental behavior change, rather than empathy alone [47,74]. When teachers offer children opportunities to develop empathy but do so without acknowledgment or discussion of negative emotions that may co-occur (such as feeling bad for not having taken action before), children may be less inclined to engage in the behavior, such as protecting wildlife, that the teachers want to encourage.

The third most common moral principle teachers engaged with focused on fairness and resource allocation. The activities and topics that engaged with this principle were gardening (farming and butterfly), land, forest, and water topics, such as making sure land resources were fairly distributed or everyone should get the same amount of water. This moral principle often occurred in conjunction with welfare issues, such as ensuring that the butterflies had their own garden space so they had enough food. Children as young as three are concerned with issues of fairness and rectifying inequalities [75] and identify that authority figures (such as teachers) cannot override issues of fairness [76]. Thus, the topics surrounding this principle are things which children are capable of engaging with and are passionate about.

Including elements of moral principles in sustainability education may help address concerns about reinforcing human exceptionalism in the UN’s SDG 4 [2] if moral principles such as welfare, harm, and resource allocation are interpreted through an ecocentric rather than anthropocentric lens [77]. Unfortunately, our study found very little evidence of teachers engaging students in moral principles. When they did, the focus was on human economic principles, such as reducing waste and recycling materials, discourses that Kopnina [78,79] argues are centered on anthropocentric solutions that may have contributed to the climate crisis in the first place. Although addressing social issues is essential to thinking about sustainability education, reinforcing moral principles as primarily anthropocentric is problematic as it models how young children should think about the world and reinforces an intention to protect nature for human gain. Unfortunately, the perspectives of our teachers in this study are not unique; many educators view sustainability through an anthropocentric lens [80,81,82] which aligns with sustainability frameworks in early childhood curricula [81,83]. Although young children think primarily through an anthropocentric lens [84,85], they also have emerging sensitivities to ecocentric views [86,87] and moral interpretations [79,88,89] that develop over time [40,41]. Educators should build on children’s capacities to encourage and develop complex moral reasoning by introducing moral principles from an ecocentric perspective rather than suggesting human-focused solutions during sustainability discussions.

4.2. Moral Reasoning

Although the topics and activities that teachers most commonly engaged in were aligned with moral principles with which children are capable of engaging, teachers rarely engaged in moral reasoning about these issues and did not work to develop children’s personal psychological resources [50] such as scaffolding children to identify specific actions that they could take to problem-solve. These teachers’ lack of engagement with the moral issues driving sustainability education aligns with literature stating that US teachers’ beliefs about children’s capabilities influence decisions to introduce social justice issues. These barriers likely exist because, in the United States, it is common for preschool teachers to focus on the cognitive limitations of children’s thinking, especially within an environmental education framework [90]. Teachers focus on cognitive limitations, even though research suggests that young children can (and should) engage in understanding climate change’s social, political, and economic causes and identifying child-appropriate action [91], and doing so from a systems level confronts often-cited critiques about sustainability education [7]. Teachers in our study often shied away from opportunities to support children by downplaying differences in order to reduce feelings of shame, reinforcing US epistemic norms about sustainability action [4].

Our study found that teachers relied on behaviors to drive social change rather than explaining to children why they were engaging in sustainability behaviors, beliefs that contradict research findings in the US [92,93] and transnational views and practices with children [94,95]. As children’s values influence their behaviors [96], not vice versa, and it is children’s moral reasoning that enables societal changes [45], ignoring opportunities to engage in reasoning actually undercuts goals for sustainable education. Teachers reported that they did not provide opportunities for children to engage with moral reasoning because they believed that children would experience negative emotions, such as fear and anxiety, when discussing why pro-environmental behaviors were necessary, as it is the teachers’ job to protect children from negative emotions. From a research perspective, these teachers’ intentions are misguided; eco-anxiety and fear are not pathological and should not be avoided [97,98,99]. Anxiety can be adaptive and used to garner hope when emotions are validated, when there are safe spaces to discuss emotions, and when positive or creative actions are encouraged [49,100] and culturally relevant strategies are used to help children cope [48]. In some cases, eco-anxiety can nurture pro-environmental behaviors [101], and utilizing nature exposure and environmental action without addressing eco-anxiety and other negative emotions de-centers human agency [102]. Thus, the teachers’ practical concerns for students’ emotions and the fear of instilling hopelessness prevented them from fostering agency and hope for change—views necessary for young children to feel empowered to combat climate change and engage with these sustainability goals [13].

Research on children’s agency in sustainability education suggests that young children can significantly contribute to their communities, locally rather than globally [103]. This potential of young children to contribute to their communities in sustainability education underscores the importance of fostering their agency. More so, children want to contribute to positive environmental solutions. However, many children cannot do so because adults place barriers on real action, such as not allowing students to leave the classroom during the school day to get signatures [104]. In our study, children who had discussions about the moral issues of sustainability were not scaffolded into positive emotions or actions. Instead, they were left to feel helpless, likely reinforcing teachers’ negative perceptions of engaging young children in moral dilemmas surrounding sustainability issues.

4.3. Moral Reasoning and Principles in the Context of Global Early Childhood Education

Implementing sustainability education on a global scale is a complex task. It requires redirecting children’s thinking and action toward more sustainable systems and lifestyles, in line with the UN sustainability goals [105]. Early childhood programs are key players in this endeavor, engaging children in all levels of sustainability education, including education for the environment. This type of education focuses on children’s actions to support the more-than-human world and make lifestyle changes. However, the transnational implementation of these educational practices is not straightforward. Engaging children in moral reasoning about sustainability education is just one strategy for fostering change.

From a global perspective, the particular findings of our study and its conclusions may not apply to all early childhood education programming, as the understanding of sustainability education [106,107,108], teacher training in sustainability education [109,110,111,112] and curriculum and activities [113,114,115] are not holistic and may vary according to country, city, and classroom [105,116]. For example, Derman and Gurbuz [113] compared primary (ranging in ages from 5–13) environmental education across five different countries (Turkey, Australia, Singapore, Ireland, and Canada) and found that the topics of environmental issues, science, and health and activities varied greatly across and within countries. Within-country variation occurred as well because of differences in mandated curriculum [113] and teacher knowledge [117]; Turkish primary teachers’ awareness about sustainable development differed according to topic and gender [118].

4.4. Recommendations for US Educators and Policy Makers

Given the structure and educational purposes of early childhood education in the US, where pre-K (3- and 4-year-olds) is not mandated nor federally funded, and K-3 (5–8-year-olds) educational experience depends on state funding and requirements for science education (which may discourage sustainability education), our suggestions may be challenging. In the US, teachers must trust children’s cognitive abilities and scaffold their thinking towards local, child-accessible solutions rather than focusing on developing sustainability behaviors out of context. Early childhood education also serves as a place where children are exposed to social and emotional learning (SEL) as well as pre-literacy and pre-numeracy concepts, and thus, sustainability education should be carefully designed to incorporate these learning goals as well. In SEL, children can practice developing their personal psychological resources for responding to climate change. Given these challenges in the US, we have two concrete suggestions for approaching sustainability within early childhood classrooms.

First, educators play a crucial role in implementing sustainability education in the complex, science standard-driven US context. They can use the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), K–12 science content standards that set the national expectations for student learning in science, in combination with the practice of moral reasoning, critical to social-emotional learning [119], as a framework for enacting sustainability education, an approach that is reflective of science education for civic engagement [120]. NGSS approaches sustainability as a set of global problems that can be solved through the use of science and technology; this approach alone, however, leaves out the emotional, moral, and ethical implications of climate change [121,122], which research in the US suggests can be a driver for personal action [123]. Providing mechanisms for young children to participate in moral decision-making about sustainability issues, even small ones such as whether to use glitter in the classroom, provides the basis for moral decision-making in broader society, enabling sustainable development. More importantly, approaches that combine moral reasoning and youth-led actions have created positive emotions that mitigate children’s negative emotions surrounding the climate crisis [123,124]. Educators should feel empowered and integral to this process.

Another way to approach SDG goals within the US educational context is to consider sustainability education with moral reasoning as an intervention for developing children’s social-emotional learning (SEL). SEL is “the process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions” [125]. The Collaborative for Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) developed an integrated Framework for Systemic Social and Emotional Learning comprising five competencies: (a) self-awareness (i.e., one’s ability to understand one’s thoughts, emotions, and values and how they influence one’s behavior), (b) self-management (i.e., one’s ability to manage one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors effectively across situations as one works to achieve goals), (c) social awareness (i.e., one’s ability to understand social perspectives and empathize with others from diverse backgrounds), (d) relationship skills (i.e., one’s ability to develop and maintain healthy and supportive relationships and navigate social situations with people from diverse backgrounds), and (e) responsible decision-making (i.e., one’s ability to make caring and constructive social and behavioral choices) [125]. Early childhood sustainability education that includes moral reasoning provides children with opportunities to think within an ethical framework that includes safety concerns and social norms. It also provides them with opportunities to learn how to self-manage emotions, working towards creating solutions involving classmates. We consider this approach reflective of helping children develop personal psychological resources, such as utilizing caring, empathy, and hope [50] when engaging in moral reasoning. This inclusion of hope, agency, and morality can be reinforced by designing activities encouraging children to reflect on the moral implications of their actions, such as discussions of fairness and resource allocation, or the impact of trash on the natural environment. With this inclusion, children can simultaneously learn about sustainability while developing the critical thinking skills necessary to navigate complex moral dilemmas via a hopeful outlook on the future.

Utilizing SEL to promote moral reasoning about sustainability education could be done in any nation whose early childhood curriculum encourages SEL frameworks, such as Brazil [126], Hong Kong [127], and China [128], as Garner and Gabitova’s [129] research across different nations finds teachers and school leaders shared a positive view about the importance of social-emotional learning for their work within and beyond the classroom, but identified barriers, including social, political, and cultural barriers to enacting this in the classroom. Indeed, much of the research on SEL has been done in rich and Western countries, suggesting limited application [130]. However, Hayashi and colleagues [131] suggest an SEL framework that is grounded in bioecological and embodied theoretical frameworks that are culturally responsive and situated in three cultural contexts, North America, Japan, and South Africa, that nations could use as an example to incorporate sustainability education and moral reasoning into an SEL framework that reflects a nation’s history, culture, and sustainability goals.

Additionally, teacher training programs should equip educators with the tools to facilitate these moral discussions, including explicit environmental or sustainability education requirements that include socio-scientific issues (SSI) in licensure programs from an ecocentric perspective. Hogan and O’Flaherty [132] argue that “teachers of pre-service science teachers have a responsibility to ensure that [education for sustainable development] features strongly in their teaching. They are also responsible for ensuring that science education allows students to reflect upon sustainability issues scientifically, focusing on scientific inquiry, evidence-based learning, and engagement in socio-scientific debate”(p. 2). These courses would include both environmental and sustainability content, which is lacking in early childhood education in the US and transnationally [133,134,135], as well as teach early childhood educators how to think about science not as de-contextualized ‘facts’ but as conceptualized within societies across the globe, which is a goal of education about the environment. In addition to science content education, pre-service teachers should be taught to think about the environment and sustainability from an ecocentric, rather than an anthropocentric, perspective. These programs should focus on discourse-based pedagogies, which allow pre-service educators to practice negotiating SSI [136] through an ecocentric lens and provide a pedagogical framework for engaging students in these types of discussions and negotiations. Another way to introduce SSI into the curriculum is through SSI comics or stories [137,138]. This approach fosters pre-literacy and allows educators to address sustainable development topics that may not arrive spontaneously in the early childhood classroom. Although SSI has not yet been studied in the US early education setting, transnational research in elementary grades suggests that it also has a positive impact on students’ science content knowledge, its relevance to everyday life, and their ability to make informed decisions about socio-scientific issues related to their everyday lives [139].

Meanwhile, policy frameworks must support this integrated approach and promote curricula that balance cognitive and social-emotional development while emphasizing moral reasoning and hope. This policy support includes providing educators with the necessary resources and curricular flexibility to introduce complex sustainability concepts that are accessible and engaging for young children. Finally, resource allocation should ensure that all children, regardless of their social location, have access to quality sustainability education that nurtures their intellect and capacity for hope, preparing them to become informed and proactive citizens in a sustainable future.

5. Conclusions

The present-day climate crisis poses an urgent global challenge that necessitates sustained engagement from all members of society—including young people. Inclusive and equitable quality education is critical in fostering pro-environmental and sustainable behaviors from an early age, as SDG 4 highlights. We argued that US early childhood educators include moral reasoning in sustainability education, enabling children to identify the social injustices inherent in anthropogenic climate change. Results from our study of US nature-based early childhood educators focus on content-driven activities instead of integrating moral principles about sustainability. Teachers often avoided discussions regarding the climate crisis that could evoke negative emotions, such as guilt or hopelessness. They relied on small actions, such as picking up trash, with the hope of driving change. The most common moral principle teachers engaged in was harm reduction, which aligned with teachers’ goals and children’s cognitive development. However, educators provided only limited moral scaffolding and missed critical teaching opportunities regarding children’s moral reasoning about sustainability issues, which could have led to meaningful action-taking. Early childhood educators are only one method among many which nations can use to help cultivate future generations that are aware of the climate crisis and equipped and motivated to address it. Embedding moral reasoning within sustainability education, we believe, allows US children to engage in meaningful and contextually relevant sustainability practices and can support the educational transformation required to address the relevant climate crisis. Educators play a crucial role in this process, as they must teach sustainability behaviors and foster a deep moral understanding of why these actions matter. Providing children with opportunities to participate in moral decision-making, even on seemingly insignificant issues, can lay the groundwork for necessary change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and J.L.G.; methodology, J.L.G. and S.A.; validation, S.A. and C.F., formal analysis, S.A. and C.F.; investigation, J.L.G.; data curation, S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A. and C.F.; writing—S.A. and J.L.G., visualization, S.A.; supervision, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Smith College (#1718-060 code) on [1 March 2018].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because consent to share the data was not approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Islam, N.; Winkel, J. Climate Change and Social Inequality. 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2020/08/1597341819.1157.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Mochizuki, Y.; Vickers, E. Still ‘the conscience of humanity’? UNESCO’s vision of education for peace, sustainable development and global citizenship. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2024, 54, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.; Mochizuki, Y. Crisis transformationism and the de-radicalisation of development education in a new global governance landscape. Policy Pract. Dev. Educ. Rev. 2023, 36, 51–76. Available online: https://doras.dcu.ie/28994/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Bengtsson, S.L. Critical education for sustainable development: Exploring the conception of criticality in the context of global and Vietnamese policy discourse. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2024, 54, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogisu, T.; Hagai, S. Localizing transnational norms in Cambodia: Cases of ESD and ASEAN citizenship education. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2024, 54, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, T.; De Souza, D.T.; Wals, A.E.J. A regenerative decolonization perspective on ESD from Latin America. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2024, 54, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockwell, A.J.; Mochizuki, Y.; Sprague, T. Designing indicators and assessment tools for SDG Target 4.7: A critique of the current approach and a proposal for an ’Inside-Out’ strategy. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2024, 54, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Vickers, E. Thailand: Sufficiency education and the performance of peace, sustainable development and global citizenship. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2024, 54, 804–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, D. Learning to Walk between the Raindrops: The Value of Nature Preschools and Forest Kindergartens. Child. Youth Environ. 2014, 24, 228–238. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/330/article/896717 (accessed on 15 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hahn, E.R. The developmental roots of environmental stewardship: Childhood and the climate change crisis. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.E.; Sanson, A.V.; Van Hoorn, J. The psychological effects of climate change on children. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Mohamed, N.S.; Siddig, E.E.; Algaily, T.; Sulaiman, S.; Ali, Y. The impacts of climate change on displaced populations: A call for action. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2021, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People Nat. 2020, 2, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger-Goodes, T.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Hurtubise, K.; Simons, K.; Boucher, A.; Paradis, P.-O.; Herba, C.M.; Camden, C.; Généreux, M. How children make sense of climate change: A descriptive qualitative study of eco-anxiety in parent-child dyads. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, E.R.; Garrett, M.K. Preschoolers’ moral judgments of environmental harm and the influence of perspective taking. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, P.H. In moral relationship with nature: Development and interaction. J. Moral Educ. 2022, 51, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T. Pro-Environmental Behavior and Adolescent Moral Development. J. Res. Adolesc. 2017, 27, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmis, S.; Mutton, R. Education for sustainability (EfS): Practice and practice architectures. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, J.D.; Swick, S.D.; Frazier, L.M.; Bishop, M.; Goodell, L.S. Teachers’ perceptions of sustainable integration of garden education into Head Start classrooms: A grounded theory approach. J. Early Child. Res. 2019, 17, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. What might education for sustainability look like in early childhood? A case for participatory, whole-setting approaches. In The Role of Early Childhood Education for a Sustainable Society; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 18–24. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/14695/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Davis, J. Examining early childhood education through the lens of education for sustainability: Revisioning rights. In Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.; Elliott, S. Young Children and The Environment: Early Education for Sustainability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, J. How to Succeed with Education for Sustainability; Curriculum Corporation: Kings Mills, OH, USA, 2007; Available online: https://researchrepository.rmit.edu.au/esploro/outputs/book/How-to-succeed-with-education-for-sustainability/9921861621201341 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Palmberg, I.E.; Kuru, J. Outdoor Activities as a Basis for Environmental Responsibility. J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Otto, S.; Kaiser, F.G. Childhood Origins of Young Adult Environmental Behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.L.; Milfont, T.L. Exposure to Urban Nature and Tree Planting Are Related to Pro-Environmental Behavior via Connection to Nature, the Use of Nature for Psychological Restoration, and Environmental Attitudes. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 787–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.B.; Mueller, M.P. A philosophical analysis of David Orr’s theory of ecological literacy: Biophilia, ecojustice and moral education in school learning communities. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2011, 6, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, D.W. Environmental education and ecological literacy. Educ. Dig. 1990, 55, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, T.G.; Öztürk, N.; İyi, T.I.; Aşkar, N.; Bal, B.; Karabekmez, S.; Höl, Ş. Education for sustainability in early childhood education: A systematic review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 796–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousell, D.; Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A. A systematic review of climate change education: Giving children and young people a ‘voice’ and a ‘hand’ in redressing climate change. Child. Geogr. 2020, 18, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furu, A.-C.; Heilala, C. Sustainability education in progress: Practices and pedagogies in Finnish early childhood education and care teaching practice settings. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2021, 8, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kroufek, R.; Nepraš, K. The impact of educational strategies on primary school students’ attitudes towards climate change: A comparison of three European countries. Eur. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2023, 11, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, M.; Korhonen, J. Ninth graders and climate change: Attitudes towards consequences, views on mitigation, and predictors of willingness to act. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2017, 26, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, M.; Elenbaas, L.; Ruck, M.D. Developmental Perspectives on Social Inequalities and Human Rights. Hum. Dev. 2022, 66, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KHussar, M.; Horvath, J.C. Do children play fair with mother nature? Understanding children’s judgments of environmentally harmful actions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, P.H.; Lourenço, O. Water, Air, Fire, and Earth: A Developmental Study in Portugal of Environmental Moral Reasoning. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Evans, G.W.; Moon, M.J.; Kaiser, F.G. The development of children’s environmental attitude and behavior. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 58, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraci, A.; Franchin, L.; Commodari, E. Evaluations of pro-environmental behaviours in preschool age. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2024, 21, 770–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wu, Z. They can and will: Preschoolers encourage pro-environmental behavior with rewards and punishments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 82, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, D.C.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; Friedman, B. Along the Rio Negro: Brazilian children’s environmental views and values. Dev. Psychol. 1996, 32, 979. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-06406-001 (accessed on 18 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Sorrel, M.A. Children’s environmental moral judgments: Variations according to type of victim and exposure to nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 62, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.N.; Smetana, J.G. Distinctions between Moral and Conventional Judgments from Early to Middle Childhood: A Meta-Analysis of Social Domain Theory Research. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 874–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, M.; Dahl, A. Moral Reasoning Enables Developmental and Societal Change. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 1209–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, A.; Schmidt, M.F. Preschoolers, but not adults, treat instrumental norms as categorical imperatives. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2018, 165, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, H.; Hudders, L.; Van De Sompel, D.; Cauberghe, V. Motivating Children to Become Green Kids: The Role of Victim Framing, Moral Emotions, and Responsibility on Children’s Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intent. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety and Environmental Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltmer, K.; von Salisch, M. Promoting Subjective Well-Being and a Sustainable Lifestyle in Children and Youth by Strengthening Their Personal Psychological Resources. Sustainability 2023, 16, 134. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/1/134 (accessed on 18 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and climate-change engagement from a psychological perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 49, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children, adolescents, and young adults relate to climate change? Implications for developmental psychology. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 20, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, K.; Kirkhus, R. Meaning-Focused Coping with the Climate Crisis Increases Emotional Wellbeing and Pro-Environmental Behavior; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.V.; Malca, K.P.; Hoorn, J.V.; Burke, S. Children and Climate Change. In Elements in Child Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, B.; Balcı, S. Ecology and the child: Determination of the knowledge level of children aged four to five about concepts of forest and deforestation. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2018, 27, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilten-Gee, R.; Manchanda, S. Using social domain theory to seek critical consciousness with young children. Theory Res. Educ. 2021, 19, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, M.; Rutland, A.; Yip, T. Equity and Justice in Developmental Science: Discrimination, Social Exclusion, and Intergroup Attitudes. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1317–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitebook, M.; McLean, C.; Austin, L.J.E.; Edwards, B. Early Childhood Workforce Index–2018; Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE). Nature Preschools in the United States: 2022; National Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- JFrey, H.; Fontana, A. The group interview in social research. Soc. Sci. J. 1991, 28, 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- McKim, C. Meaningful Member-Checking: A Structured Approach to Member-Checking. Am. J. Qual. Res. 2023, 7, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation 2.0. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, P.C.; Verloop, N.; Beijaard, D. Multi-method triangulation in a qualitative study on teachers’ practical knowledge: An attempt to increase internal validity. Qual. Quant. 2002, 36, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozalek, V.; Zembylas, M. Diffraction or reflection? Sketching the contours of two methodologies in educational research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2017, 30, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufford, L.; Newman, P. Bracketing in qualitative social work. Qual. Soc. Work 2010, 11, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G. Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, F.; Radhika, V. Debunking the myth of the efficacy of “push-down academics”: How rigid, teacher-centered, academic early learning environments dis-empower young children. J. Fam. Strengths 2018, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curby, T.W.; Zinsser, K.M.; Gordon, R.A.; Ponce, E.; Syed, G.; Peng, F. Emotion-focused teaching practices and preschool children’s social and learning behaviors. Emotion 2022, 22, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, S.A.J.; Li, V.; Haddock, T.; Ghrear, S.E.; Brosseau-Liard, P.; Baimel, A.; Whyte, M. Perspectives on perspective taking: How children think about the minds of others. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2017, 52, 185–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Young, A.; Khalil, K.A.; Wharton, J. Empathy for Animals: A Review of the Existing Literature. Curator Mus. J. 2018, 61, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, J.K.; Bloodhart, B. Portraying the Perils to Polar Bears: The Role of Empathic and Objective Perspective-taking Toward Animals in Climate Change Communication. Environ. Commun. 2015, 9, 446–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.T.; Killen, M. Children’s understanding of equity in the context of inequality. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 34, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, E.M.; Killen, M. Children’s Perspectives on Fairness and Inclusivity in the Classroom. Span. J. Psychol. 2022, 25, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.C.; Gagnon, C.; Barton, M.A. Ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1994, 14, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for the future? Critical evaluation of education for sustainable development goals. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 51, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Revisiting Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): Examining Anthropocentric Bias through the Transition of Environmental Education to ESD. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, F.; Castéra, J.; Clément, P. Teachers’ conceptions of the environment: Anthropocentrism, non-anthropocentrism, anthropomorphism and the place of nature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 22, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, N. Anthropocentric tendencies in environmental education: A critical discourse analysis of nature-based learning. Ethics Educ. 2020, 15, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzel, N.; Gül, A. Pre-service Biology Teachers’ Moral Reasoning about Socioscientific Issues and Factors Affecting Their Moral Reasoning. Bull. Educ. Stud. 2023, 2, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldemariam, K.; Boyd, D.; Hirst, N.; Sageidet, B.M.; Browder, J.K.; Grogan, L.; Hughes, F. A Critical Analysis of Concepts Associated with Sustainability in Early Childhood Curriculum Frameworks Across Five National Contexts. Int. J. Early Child. 2017, 49, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dölek, B.Ş.; Akyol, G. Inspecting primary school students’ environmental attitudes based on ecocentric and anthropocentric perspectives. Turk. J. Educ. 2023, 12, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsar, A.; Doğan, Y.; Sezer, G. The ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes towards different environmental phenomena: A sample of Syrian refugee children. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 70, 101005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, D. Preschoolers’ pro-environmental orientations and theory of mind: Ecocentrism and anthropocentrism in ecological dilemmas. Early Child Dev. Care 2020, 190, 1820–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Vasconcelos, C.M.; Strecht-Ribeiro, O.; Torres, J. Non-anthropocentric Reasoning in Children: Its incidence when they are confronted with ecological dilemmas. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margoni, F.; Surian, L. The emergence of sensitivity to biocentric intentions in preschool children. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckert, J.H. Generation Conservation: Children’s Developing Folkbiological and Moral Conceptions of Protecting Endangered Species. In Young Children’s Developing Understanding of the Biological World; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bredekamp, S. Position statement on developmentally appropriate practice in programs for 4-and 5-year olds. In National Association for the Education of Young Children; NAEYC: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Green, K. Environmental Awareness in Early Years Education: A Systematic Content Analysis on Research from Different Countries. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Audley, S.; Stein, N.R.; Ginsburg, J.L. Fostering children’s ecocultural identities within ecoresiliency. In Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, B.M.H.; Fischer, B.; Clayton, S. Should we connect children to nature in the Anthropocene? People Nat. 2022, 4, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banunle, A. Determinants of pro-environmental behaviour of urban youth in Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesar, M.; Jukes, B. Childhoods in the Anthropocene: Rethinking Young Children’s Agency and Activism. In Found in Translation; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė, I. Sustainability in Youth: Environmental Considerations in Adolescence and Their Relationship to Pro-environmental Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 582920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]