Abstract

While entrepreneurship continues to gain significance worldwide as a means for economic development and a tool for youth employment, coffee cultivation entrepreneurial intention becomes an essential goal to investigate and a necessary instrument. Accordingly, this research investigates the role of external factors, namely Access to Finance (ATF), Structural and Institutional Support (SIS), Physical Infrastructure Support (PIS), Social Influence (SIF) and Education and Training (ET), in stimulating Coffee Farming Entrepreneurial Intention (CFEI) among potential entrepreneurs (students). A sample of 318 participants from various universities in Saudi Arabia responded to an online questionnaire, forming the basis for analysis using Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). The study reported different findings, such as a positive relationship between CFEI and other factors, namely PIS, SIF and ET. However, the study found no positive connection between ATF, SIS and CFEI. The study concluded by providing actionable recommendations for policymakers about stimulating coffee farming among students and contributing to the economic development process and youth employment. It also assists in the establishment of sustainable business environments for future generations.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship and small enterprises have been widely acknowledged for their pivotal role in the creation of employment, the mitigation of poverty, the empowerment of people and the strengthening of self-confidence and independence in people [1,2,3,4]. Hence, there has been a focus on developing entrepreneurship and the small and medium enterprises (SME) sector due to their influential role in economic development [5,6]. The positive role of entrepreneurship in economic development necessitates an understanding of why some people prefer to become entrepreneurs while others do not. To address this, it is necessary to know that the intention and decision of individuals to become an entrepreneur are influenced by different individual and environmental factors [7]. Entrepreneurial intention is essential to understand, as it is considered the best predictor for entrepreneurial behaviour and is the first step in entrepreneurship [8,9]. Entrepreneurial intention also reflects people’s readiness, passion and enthusiasm to engage in entrepreneurial business [3,10]. Consequently, it is necessary to understand the key factors contributing to its development.

Individual factors, such as the need for achievement, subjective norms and locus of control, can positively influence entrepreneurial intention among individuals, particularly students [11]. Some other factors, such as self-efficacy, risk-taking, motivation and others, may also contribute to the developing decision to start a business. While these factors are considered personal or individual factors, it is essential not to ignore external factors such as available infrastructure, financial support, social influence, regulative support and institutions in general for their role in enhancing the entrepreneurial intention [3,5,12]. More specifically, to encourage high entrepreneurial activities in a given context, it is essential to consider personality factors such as risk-taking, self-confidence, locus of control and need for achievement, as well as other external factors such as cultural, economic, social, political, demographic, technological, market, human capital, finance, culture and policy factors that support these entrepreneurial activities [9,13,14]. These factors and others act as enablers and provide a proper business environment to stimulate individuals to use their talents and develop innovative ideas [5]. These factors and others represent the so-called entrepreneurial ecosystem that contributes to the formation of new enterprises and the development of entrepreneurial activities [15]. Moreover, they also inspire entrepreneurs to succeed in their entrepreneurial journey [5,16].

Despite the belief that there have been studies in the literature about entrepreneurial intention and critical factors influencing it, it is believed that there is still a lack of literature about it, mainly as most of these conducted studies were implemented in developed countries [17]. Furthermore, these previous studies, in addition to being performed in developed countries, were about individual traits and personalities. These previous studies ignored external factors, which also contribute to developing entrepreneurial intention [3,18,19,20]. Hence, in this research, we continue investigating and fill in the research gap and focus on examining the role of certain critical external factors, namely structural and institutional support, financial support, social influence, physical structure support and education and training support, on developing the coffee farming entrepreneurial intention among the potential entrepreneurs, namely students in Saudi Arabia.

We aim to investigate this, because there has been some evidence claiming that external factors or the so-called entrepreneurial ecosystem in Saudi Arabia has some ambiguity in its policies and regulations [21]. The Saudi entrepreneurial ecosystem also still needs further development and setting strategic plans to overcome the challenges it faces [22]. Nevertheless, despite this criticism about the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Saudi Arabia, it is believed that Saudi Arabia has taken many critical steps and developed many initiatives to provide a conductive business environment for entrepreneurship for specific business industries, such as the Saudi coffee industry.

For example, it has recently conducted substantial economic reforms in various parts of the country under the Saudi 2030 vision. The Saudi Vision 2030 focuses on significant change and improvement in different economic sectors, including the coffee industry, which had a share market valued at USD 1575.52 million in 2021, projected to reach USD 2220.70 million by 2028 [23]. Accordingly, for further improvement in the coffee sector, Saudi Arabia has taken many initiatives to develop and cultivate the coffee industry in the country, especially in areas considered suitable for coffee cultivation, such as the regions of Jazan, Asir and Al-Baha. Accordingly, the Saudi government further guided the Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture (MEWA) to work dedicatedly on advancing coffee cultivation, especially in the country’s southern region, which hosts about 2535 coffee farms, including 500 model farms. The Saudi government aims to develop Arabic coffee production in 15 southern areas, which will become significant hubs for Arabic coffee production, perfectly aligning with the 2030 Saudi economic vision. Saudi Arabia is considered one of the top states in coffee consumption, and consequently, it targets planting about 1.2 million coffee trees by 2026. Therefore, the MEWA established the Sustainable Agricultural Rural Development Program (REF) to meet this objective, explicitly concentrating on Arabic coffee production, processing and marketing [24].

The Saudi government has also taken another important initiative to encourage the cultivation of coffee in the country by establishing the Saudi Coffee Company (SCC), which is a specialised academy that focuses on empowering entrepreneurs, Saudi farmers and coffee enthusiasts by supplying them with expertise and knowledge about coffee roasting, cultivation and preparation. It further aims to set the standards for the coffee industry in the country and provide entrepreneurs with the tools and expertise to successfully establish coffee-related businesses and coffee farms [25]. Furthermore, the Saudi Coffee Company has the intention of allocating about USD 320 million in the next ten years to develop the coffee sector, which will hopefully increase the production of coffee from 300 to 2500 tonnes per annum, ultimately resulting in the development of new job opportunities [26].

Given all the above focus and support from the government and the Saudi Vision 2030 toward enhancing and encouraging the Saudi coffee cultivation and industry in the country, a significant question arises: to what extent the available formal and informal institutions, namely physical infrastructures, structural and institutional support, social influence, education and training support and access to finance and other supports, stimulate the potential entrepreneurs, namely students, and develop their entrepreneurial intention toward coffee cultivation in Saudi Arabia, especially as there have not been any previous studies examining this relationship among the students. It has been reported that enhancing entrepreneurial activities among individuals will require a supportive business environment encompassing different supports mentioned earlier. Accordingly, this study will seek to answer the question of to what extent external factors, namely access to finance, education and training, social influence, structural and institutional support and physical infrastructure support, influence the entrepreneurial intention of the students in Saudi Arabia to develop coffee farming entrepreneurial intention. By concentrating on these proposed factors, we aim to encourage and support essential practices that positively contribute to the economy’s growth and development and, at the same time, ensure the social well-being of people and the sustainability of the environment.

2. Theoretical Background

This study is based on the institutional theory developed by [27]. The institutional theory comprises two components, namely formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions include, but are not limited to, laws and regulations, property rights and constitutions, while informal institutions include sanctions, traditions and customs. The institutional theory explains the complex relationship between formal and informal institutions and their influence on individual behaviour and intention. Institutions provide essential instructions, support and resources for individual behaviour or restrictions and prohibition of this behaviour [28].

This study deals with both formal and informal institutions. We start with access to finance, in which the business environment that provides financial support will influence the students’ perception towards establishing coffee farming businesses. Structural and institutional supports are defined as specific rules, regulations and policies designed to develop and enhance entrepreneurial intention among the students. The more suitable and adequate business rules and regulations are, the more we can create potential coffee farming entrepreneurial intention. Furthermore, there is a need for sufficient physical infrastructure for students to develop positive perceptions towards starting a business on a coffee plantation. Education and training are also considered formal institutions that impact entrepreneurial intention. It is believed that, the better and higher knowledge, training and skills provided, the higher their perception will be towards starting a coffee cultivation business. The more education and training are offered, the higher entrepreneurial intention will be among the students. Finally, social influence is considered informal institutions, and it indicates the influence of networks, relaxed norms, friends, colleagues and peers on the perception of students to develop entrepreneurial coffee intention. The higher the social influence, the higher the students’ legitimacy and acceptance of entrepreneurial activities.

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Access to Finance and Coffee Farming Entrepreneurial Intention

As stated earlier, entrepreneurial intention in an individual is stimulated by various external and internal factors. These factors are called disablers and enablers of business. One of those external factors is access to finance, which is considered an integral part of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and is the backbone for establishing any business [29]. Access to finance has been defined as the ability of an individual to find use and benefit from available capital [30]. In this research, we limit access to finance to those various funding options offered by different entities, which include but are not limited to support from informal investors, equity, debt, business angels, venture capitalists and government finance available for fostering business creation and expanding existing enterprises.

Access to finance and entrepreneurial intention have previously reported conflicting findings. For instance, the study by [31], based on data collected from 181 students affiliated with two Romanian universities, revealed that access to finance plays a pivotal role in the decision to start a business and entrepreneurial intention among the students. In another significant empirical study by [32], it was found in their research, which was based on harmonised data collected from 16 countries, that access to finance is an essential factor in enhancing the establishment of business, especially in those sectors that count heavily on required financial support. Also, Ref. [33] confirmed that instrumental readiness, which includes capital access, networking and informational access, positively and significantly influences EI among Norwegian and Indonesian students. Additionally, Ref. [34] showed that poor access to finance leads to discouraging individuals, particularly potential and nascent entrepreneurs, from developing entrepreneurial intention, and they considered access to finance as instrumental readiness. This was also supported by [33,35], who stated that the inability to pay back the borrowed loans is a significant disabler for entrepreneurs in developing countries. Also, Ref. [36] claimed that the higher the level of financial literacy, the more entrepreneurial intention can be developed among the students.

Notably, there have been some interesting findings regarding access to finance and EI. For example, Ref. [30] disclosed in their study, which was based on data collected from students in Vietnam, that access to finance cannot directly influence the students’ entrepreneurial intention. Access to finance can only influence EI through perceived behavioural control and attitude toward behaviour. In a similar finding, Ref. [35] revealed that access to finance cannot merely impact the EI of people; it should be supported by the ability to control so that action can be directed toward the EI. Refs. [5,37] also confirmed that, in their empirical study among female students, access to finance did not positively influence EI. Accordingly, we posit that the presence of sufficient access to capital can encourage Saudi Arabia students to foster entrepreneurial intention in coffee farming, and thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1:

Access to finance positively influences the coffee farming entrepreneurial intention of potential entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia.

3.2. Structural and Institutional Support and Coffee Farming Entrepreneurial Intention

Successful business and developed entrepreneurship cannot rely on personality traits and ignore other economic and environmental factors surrounding them [38]. Accordingly, factors such as structural and institutional support should also be considered, as they are crucial in any given business environment and deal with the necessary support for backing up business activities in terms of rules, regulations and policies imposed by the government that help entrepreneurs operate and develop EI [13,39]. Both governmental regulations and policies can act as determinants for business opportunities in business contexts [37]. In this research, we define structural and institutional support as support provided by the government and other bodies in the country to enhance entrepreneurial activities. This structural and institutional support includes, but is not limited to, modern technological information; tax deduction schemes and the execution of beneficial policies, rules and regulations that enhance the business environment and make it suitable for business growth and innovation.

Different studies have been conducted concerning the connection between structural support and EI. For example, Ref. [40] conducted research among college students in Ghana, and it was found that a positive connection exists between entrepreneurial intention and other factors, such as incentives and initiatives offered by governmental and non-governmental organisations in the country. In another study implemented in Turkey by [13], it was revealed that structural and educational support positively impacted the intentions of 300 university students.

Furthermore, the study by Imran [5] also reported that government policies, programmes and regulations positively support the entrepreneurial intention of female Saudi students in Saudi Arabia. In the study of [41] conducted in China, it was reported that governmental institutional support strengthens entrepreneurial intention. In the study of [2], it was found that, based on the GEM data for Saudi entrepreneurs, insufficient business legislation and policies will negatively impact entrepreneurial intention. This finding was also supported by the study of [42], who stated that those nations providing poor regulatory quality, lack of rule of law and political instability and the presence of corruption all contribute negatively to developing entrepreneurial intention among Pakistan students. The poor structural support also prevents entrepreneurs or individuals from recognising available business opportunities [43]. Accordingly, the differences in public legal institutions can impact entrepreneurial activities differently [43].

According to the above discussion, a supportive structure and institutional support for potential entrepreneurs will encourage them to develop entrepreneurial intentions in coffee farming. Thus, we assume the following hypothesis:

H2:

Structural and institutional support positively affects students’ entrepreneurial intentions concerning coffee farming in Saudi Arabia.

3.3. Physical Infrastructure Support and Coffee Farming Entrepreneurial Intention

Infrastructures are the different types of means that help individuals carry out certain activities in a given context. Infrastructure, in general, helps entrepreneurs identify and explore available business opportunities and capitalise on them [44]. Physical infrastructures are those essential structures, facilities and systems supporting the economy [45]. Infrastructures can encourage entrepreneurial activities and opportunities by promoting entrepreneurs to benefit from these opportunities by establishing their businesses [46]. This article defines physical infrastructure support as those physical conditions, including utilities, accessible roads, communications and waste disposal. These infrastructures ensure that newly developed enterprises receive reliable access to significant communication services such as the internet and phones and other basic needs such as water, gas and electricity. This ultimately helps to foster enterprises’ operations more effectively and efficiently. Regarding the studies related to entrepreneurship and physical infrastructures, it should to be noted that there is minimal literature about it [45]. For example, a survey by [44] reported that, while infrastructure is positively linked to entrepreneurship and startup activities, specific types of infrastructure, such as broadband, seem to have more influence on startup activity than other infrastructures, such as railroads and highways. Ref. [45], which was based on data from 1993 to 2015, revealed different results. It reported that private infrastructure investment is an enabler and is positively associated with creating job opportunities and businesses. At the same time, public infrastructures are linked with destroying jobs and businesses and act as disablers for entrepreneurship. Furthermore, the study by [47] reported that the development of entrepreneurial infrastructures, such as institutional support and public resource allocations, is essential for entrepreneurial activities.

Finally, the study by [3,5] reported contradictory results on student samples, despite being conducted in the same context. While [5] reported a negative relationship between physical infrastructure and EI, Ref. [3] confirmed the presence of a positive relationship between EI and physical infrastructures. Therefore, from the above review of the literature, we argue that, the more physical infrastructure is provided to the students, the higher their EI about investing in coffee farming will be, and hence, we develop the following hypothesis:

H3:

Physical Infrastructure support positively influences the coffee farming entrepreneurial intention of students in Saudi Arabia.

3.4. Social Influence and Coffee Farming Entrepreneurial Intention

Like other elements within the entrepreneurial ecosystem, social influence represents a facet of informal institutions shaping individuals’ behaviours and attitudes. It encompasses the sentimental support received [13]. In this research, we operationalised social influence as the emotional encouragement and support provided to individuals in general and students or potential entrepreneurs in particular from family, friends and society. This support assists in developing their entrepreneurial intention. The positive sentiments and care supplied by the surrounding community positively influence individuals and provide them with necessary emotional support, strengthening their ability to engage in entrepreneurial activities.

Studies related to EI and social influence vary across different contexts. For example, the survey in [43] reported that those cultural environments where communities encourage entrepreneurial activities and support self-confidence can provide more entrepreneurial opportunities for entrepreneurs. Furthermore, Ref. [40] conducted a study among 228 polytechnic students in Ghana and confirmed a positive relationship between family and peer support and entrepreneurial intention.

Also, the study in [48] examined the influence of both formal and informal institutions on entrepreneurship and found that informal institutions, such as social influence, have a higher impact on entrepreneurship. In Saudi Arabia, a study conducted in [5] revealed that social factors positively influence entrepreneurial intentions among female students, a finding that was also confirmed in [3]. In the context of Indonesia, it was revealed that entrepreneurial intention is positively connected with social support, i.e., family and friends [49,50], and the same results were found in [34] in the context of Turkish universities. In contrast, Ref. [39] showed no relationship between informal support and EI. To conclude, social factors, especially social norms, shape the behaviour and intentions of the students through their self-perception [51,52].

Building on the above review, we argue that the coffee farming entrepreneurial intention among Saudi students can be influenced by social support provided by their surroundings and community. Accordingly, we develop the following hypothesis:

H4:

The entrepreneurial intention of students in Saudi Arabia regarding coffee farming is positively shaped by social influence.

3.5. Education, Training and Coffee Farming Entrepreneurial Intention

Entrepreneurial education is defined as instructional activities provided within schools or outside to encourage individuals to engage in entrepreneurial activities [13]. Education and training are considered essential parts of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, as they provide individuals with the necessary knowledge and skills for carrying out their business activities. Nevertheless, it is believed that many academics still lack the skills needed to start a business [53]. According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), poorly educated individuals tend to develop fewer entrepreneurial activities.

This research defines education and training as the knowledge provided at different stages to support individuals’ self-efficacy and personal initiatives and to foster creativity. It also provides information about market economic principles and emphasises new enterprise development and entrepreneurship.

The relationship between education related to entrepreneurship and its influence on EI has been discussed in previous studies. For example, Ref. [54] emphasised the need for an education that exposes students to practical experience; develops problem-solving skills; fosters the student’s critical thinking and provides access to mentorship, workshops and financial sources to build a higher level of entrepreneurial intention among students. The study in [19] also confirmed the need to focus on training and education to enhance early-stage female entrepreneurs in Ireland and Germany. In Africa, Ref. [55] conducted a study confirming the need to focus on incorporating higher education and specialised entrepreneurial training into state policies so that entrepreneurs can benefit from them and develop their skills. In the study in [56], the researchers collected data from 17 European countries, and their findings revealed that offering education to students is not necessarily what they require, as the focus is more on seminars and lectures but less networking and coaching activities. In another study executed in [57], the findings reported that enterprise training and education offered at schools do not positively impact the ability of graduates to recognise available opportunities or their skills perceptions. Education and training are essential for graduate students and their entrepreneurial activities [5,40,58]. Based on the above discussion, it is argued that students or potential entrepreneurs, if supported with the necessary education and training, can develop entrepreneurial intention in coffee farming. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H5:

The entrepreneurial intention of students in Saudi Arabia towards coffee farming is positively impacted by education and training.

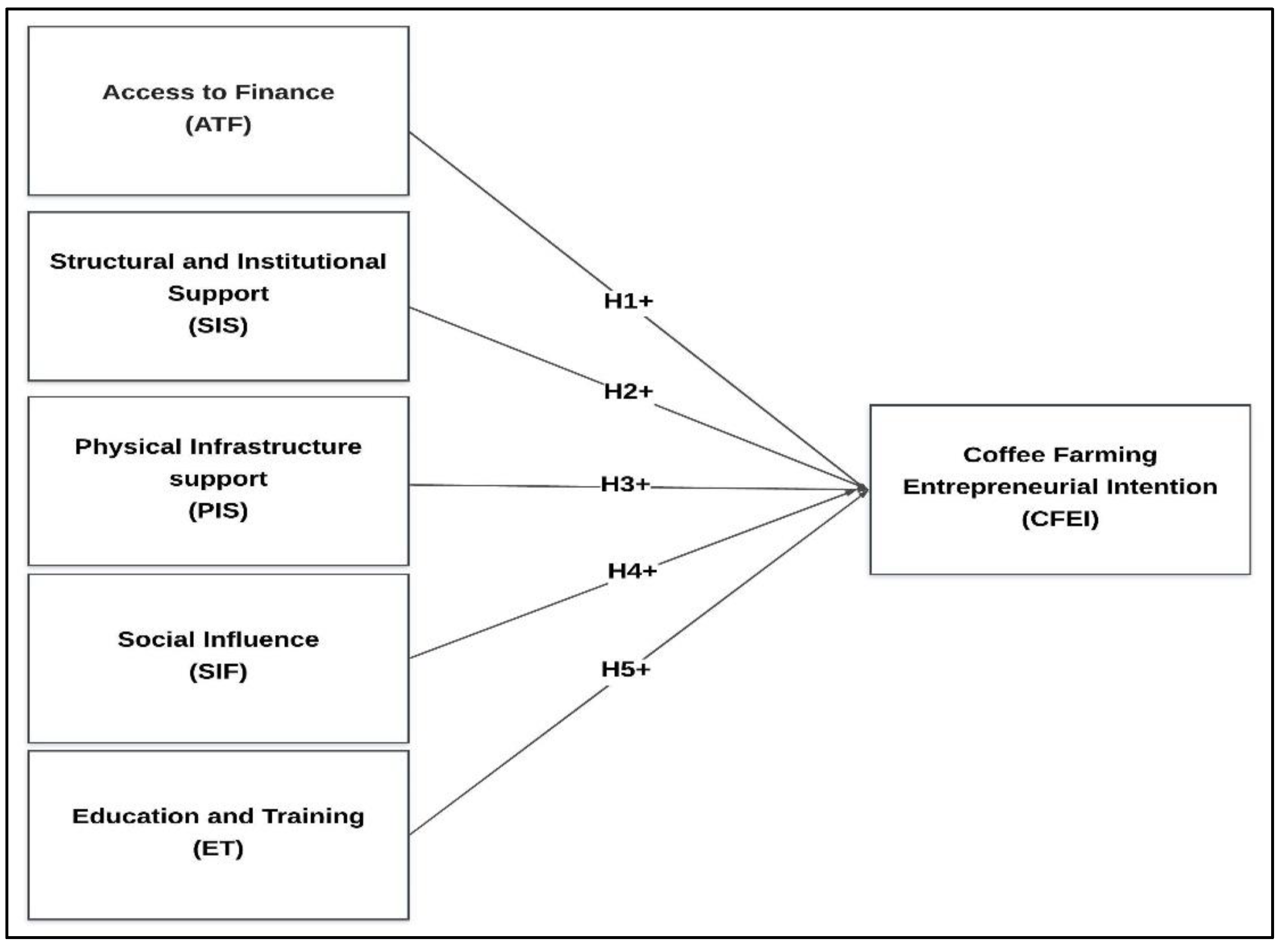

4. Conceptual Model

The current model in Figure 1 is developed after thoroughly reviewing the literature. In this model, we have two types of variables: independent and dependent. Access to finance, structural and institutional support, physical infrastructure support, social finance, education and training are all independent variables, while coffee farming entrepreneurial intention is the dependent variable.

Figure 1.

Hypothesised model. Source: authors’ elaboration.

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Research Design and Data Collection

While Saudi Arabia is putting significant effort into developing different initiatives, such as the Saudi Vision 2030 for developing various aspects of the economy—including the coffee industry—to provide more job opportunities and increase its GDP, it is essential to contribute to these efforts by conducting necessary research in support of the government’s initiatives effort. Accordingly, this quantitative deductive study aims to understand the influence of five key institutional factors—access to finance, structural and institutional support, physical infrastructure support, social influence and education and training support—on developing entrepreneurial intention among potential entrepreneurs (students) in Saudi Arabia. These factors are considered components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem influencing Saudi students’ coffee farming entrepreneurial intention. To fulfil the study’s objectives, this study collected a sample of 318 respondents from students studying in different universities in Saudi Arabia, particularly those in the southern region, as that region is considered conducive to farming and coffee cultivation. The sample also included respondents from other universities in other places to ensure a larger sample size. Students have been identified as potential entrepreneurs, and if they receive the necessary educational and technical support, they might be motivated to start their potential businesses. Therefore, the sample for this study was collected from them. It was aimed to understand how the formal and informal institutions selected in the study influence students’ entrepreneurial intention towards establishing businesses in coffee cultivation, as developing entrepreneurial intention could allow them to start their businesses and create job opportunities for themselves, especially with the government’s available support.

Accordingly, since the sample was collected from different universities in the study context, using an online questionnaire and a non-probability sampling (convenience sampling) was deemed the appropriate strategy for this research. Convenience sampling is a non-probability method designed to offer researchers straightforward access to data. It is used in quantitative and qualitative research and focuses on respondents willing to participate and be part of the study sample [59,60]. The questionnaire employed in this article was initially translated into Arabic. Then, it was checked and verified by an authentic English language agency to ensure there was no issue with its translation, and it was sent to some experts to review its content and validity. We then conducted a pilot study with 15 respondents, and since there was no problem with it, we proceeded in distributing it to the respondents. It was kept online from December 2023 to February 2024.

5.2. Measures of the Study

The measures used in this research have been adopted from authentic and validated previous studies. For example, the measures used in measuring entrepreneurial intention were adopted from [8], while other constructs, namely access to finance, physical infrastructure support, social influence and education and training, were adopted from the study in [5]. The measures for structural and institutional support were adopted from the study in [41]. An example of the entrepreneurial intention measures included “I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur in the field of coffee farming in Saudi Arabia”, and an example of the measures for structural and institutional support was “the government has provided us with beneficial policies and projects”. Concerning examples of the measures for constructs, namely access to finance and physical infrastructure support, they included “In my country, equity funding is available for new and growing firms” and “In my country, the physical infrastructure (roads, utilities, communications, and waste disposal) provides good support for new and growing firms”, respectively. Finally, the social influence, as well as education and training support, included examples for their measures as “In my country, successful entrepreneurs have a high level of status and respect” and “In my country teaching in primary and secondary education encourages creativity, self-sufficiency, and personal Initiative”, respectively. The responses for these measures were collected using a five-point Likert scale.

6. Findings and Analysis

6.1. Findings Related to Demographic Information

The researchers collected data from students in various Saudi Arabian universities, namely, Jazan University, King Khalid University, Bisha University, Al Baha University, Taif University, King Faisal University, Najran University and Northern Border University. The study sample totalled 318, 62% male and 38% female. Regarding the marital status of the respondents, it was found that about 89% were single. With regard to the age category of the respondents, it was found that about 93% of the respondents were aged between 18 and 28 years. Concerning their colleges, it was found that about 31% belonged to the applied college, 16% to the business administration college and 53% to other colleges such as agriculture college and others. Regarding the respondents’ university affiliations, about 31% were from Jazan University, 30% from Northern Border University, 23% from King Faisal University, 3% from Hail University, 6% from Al Baha University, 2% from King Khalid University and 5% from other universities.

6.2. Findings Related to Data Analysis

As indicated earlier, this is quantitative and deductive in nature, with a reasonable sample size. Consequently, partial least squares-structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was used, as it deals with complex models and is appropriate for suitable sample sizes. The PLS-SEM methodology employs the following two steps: the measurement model and the structural model.

6.3. Analysis Related to the Measurement Model of the Study

In the first stage, the PLS-SEM measurement model was evaluated. The main aim was to assess the reliability and validity of the constructs and their items used in the study. When testing the constructs and their items, if their values are high, this indicates the developed model is good accordingly. We conducted many tests, such as Cronbach’s alpha (CA), Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Variable Inflation Factor (VIF) and common method bias (CMB). In the measurement model, we began by looking at the constructs’ indicator loadings for all constructs used in this study. The recommended threshold for these indicator loadings is 70%. Indicators with loadings of up to 70% are recommended, as their values show that the constructs can explain half of the variance in those measures and indicate how adequately the measure reflects the underlying construct [61].

After completing the testing of the construct items loading, we assessed the internal consistency reliability of the constructs used in this study by using Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR). The suggested criterion for CA and CR is values exceeding 0.70, indicating good internal consistency reliability [62]. Our research’s findings, as shown in Table 1, align with this threshold. Subsequently, we tested the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) with an objective threshold of 0.50 or higher. This indicates a satisfactory level of variance captured by each construct relative to the measurement error. The findings met this recommended threshold.

Table 1.

Representation of the measurement model reliability and validity.

We then analysed the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to assess if there was any multicollinearity among the exogenous variables, which meant checking to what extent the model constructs were correlated with each other. For our model, Appendix A and Table 2 shows that our results indicated no significant multicollinearity issues, with all VIF values below 5 [62].

Table 2.

Variance Inflation Factor.

To ensure the data are bias-free, we tested for common method bias (CMB) by applying Harman’s single-factor test. The findings demonstrated that the results did not reveal any common method bias, since Harman’s single-factor value was below 50%, implying no common biases [63].

In the next step, we assessed the discriminant validity of the study’s constructs. Here, we consider the Fornell–Larcker criterion and examine the square root of the AVE for each construct and their correlations with other constructs in the study. Table 3 shows us if the variables used in the developed model, namely CFEI, PIS, ET, ATF, SIS and SIF, are distinct from each other or not. In short, the greater the number in the table, the higher the level of discriminant validity, and it indicates that each variable used in the model is not mixed with another variable; it is only influenced by itself.

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Accordingly, our model’s findings revealed satisfactory discriminant validity [64], as reported in Table 3.

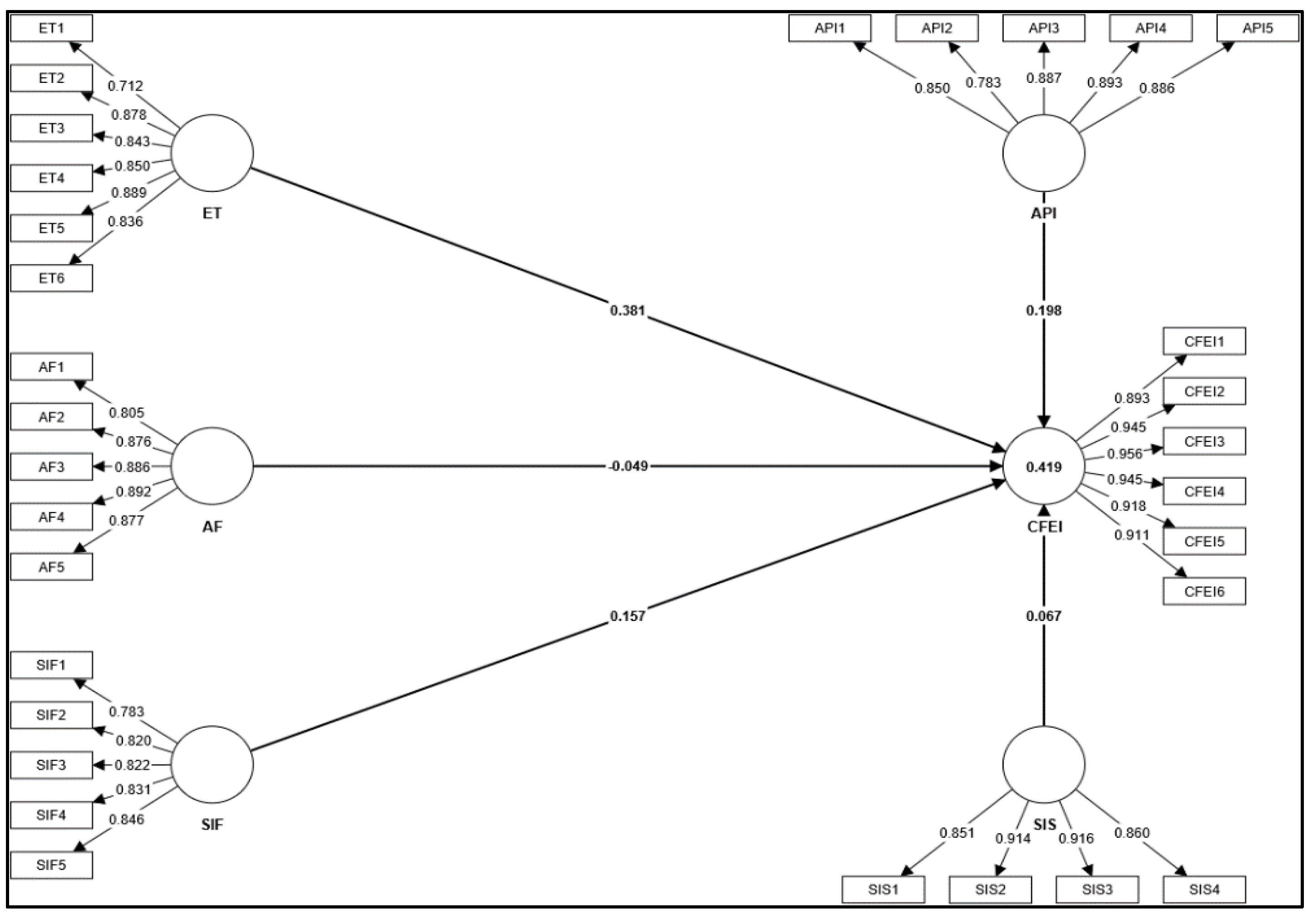

6.4. Analysis Related to the Structural Model

The second step in the PLS-SEM process is to test the significance of the hypotheses developed. Here, we employ the bootstrapping method to assess the results of the path values and their significance [65]. We use the regression method to test the relationships between the variables of the study (independent and dependent variables) with the help of tests such as p-value, t-value and coefficient of determination (R2) [66]. Upon conducting the regression test, we obtained intriguing results. Specifically, we found that PIS, SIF and ET can positively influence the CFEI, while ATF and SIS did not show any positive relationship with it. We further elaborate on these results in Section 7.

We also examined both F2 and R2, as they are essential for testing the quality of the regression model. Different thresholds have been reported in the literature for F2 and R2; however, as per the guidelines of [67], the R2 can be categorised into three levels when evaluated, i.e., =0.26 (significant), =0.13 (moderate) and =0.02 (weak). In this study, we found that the R2 is 41.9%, which means that PIS, SIF and ET explain around 41.9% of the variance in the CFEI. Regarding the effect size (F2), Ref. [67] reported that the effect size has three categories: =0.02, =0.15 and =0.35; these categories can indicate weak, moderate and substantial effects of the independent variables on the dependent variables, respectively. This study’s findings revealed a moderate effect of ET on the CFEI (11.6%), and other constructs reported a weak effect. Finally, we tested the Q2 to show the predictive relevance of the study model. Our model’s Q2 values for the endogenous variable “CFEI” reported a medium predictive relevance level (Q2 = 0.356).

Table 4 presents the results of testing the study’s hypotheses.

Table 4.

Hypotheses testing.

Figure 2 shows the different path coefficients of the study model.

Figure 2.

Path coefficients. Source: primary data.

7. Discussion

The significance of cultivating coffee and advancing the coffee industry in Saudi Arabia has necessitated various Saudi governmental bodies to take different essential initiatives, including the development of Saudi Vision 2030. In line with this effort, this research contributes to this endeavour by seeking to comprehend the primary external factors that contribute to the enhancement of entrepreneurial skills and the development of entrepreneurial intention among potential entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia, namely students. Accordingly, a comprehensive model was developed after a thorough review of the available literature about the concepts of the study, and various hypotheses were developed. The model of the study included five hypotheses, and the findings related to these hypotheses reported different and interesting results as follows.

The first hypothesis (H1) assumed the presence of a positive relationship between access to finance and coffee farming entrepreneurial intention (ATF → CFEI). However, and surprisingly, the findings revealed that there was no positive relationship between access to finance and coffee farming entrepreneurial intention among the students. Despite being illogical, this finding is supported by previous studies such as [5,30,37]. Conversely, it is not in line with other findings that proved otherwise, such as [30,31,33]. Concerning the second hypothesis (H2), which posited the existence of a positive relationship between structure and institutional support and coffee farming entrepreneurial intention (SIS → CFEI), it was also revealed that there was no positive relationship between structure support and coffee farming entrepreneurial intention among the students. This finding was not in line with studies such as [5,40,41].

Nevertheless, these unexpected findings related to H1 and H2 of the study might be attributed to various reasons, such as the students’ perceived economic risk of coffee farming. They might also be unaware of the available support for coffee cultivation, which could contribute to a negative perception of the coffee cultivation business. Furthermore, a lack of awareness about financial resources and structural support may lead to scepticism or hesitation in expressing entrepreneurial intentions related to coffee farming. Therefore, there is a need to offer necessary educational initiatives or awareness campaigns about the existing support mechanisms for coffee farming that may enhance their knowledge and skills.

With regards to the third hypothesis (H3), assuming that there exists a positive connection between PIS and the CFEI, it was found that this hypothesis was confirmed and is in line with [3,44,46]. The finding related to H3 is logical, as the more infrastructures are provided, the better the perception of students toward starting a business, as they feel that there is enough of an entrepreneurial ecosystem to support them. Accordingly, a better perception of starting a coffee business is developed among the students. When individuals feel that all necessary infrastructures are provided for them to start their entrepreneurial business, their confidence, skills and knowledge will increase accordingly. As a result, more business development will occur and vice versa. Looking at the findings for H3 from a practical point of view, we conclude that investing in physical infrastructure is vital, as it bolsters entrepreneurial activities in coffee cultivation. Accordingly, educators, policymakers and other stakeholders can employ these findings to argue and implement plans and strategies that support the accessibility of infrastructure support. To conclude, practical initiatives should include providing processing units, well-equipped agricultural facilities and storage spaces that can positively lead to establishing conducive environments that inspire coffee cultivation entrepreneurs or students.

Concerning the fourth hypothesis (H4), claiming the presence of a positive relationship between SIF and the CFEI, it was reported that SIF positively influences the CFEI. Accordingly, this hypothesis was approved, and is in line with the previous studies of [5,40,43]. The result of (H4) is accurate: the more society, friends, peers and family encourage potential entrepreneurs and provide them with emotional support, the higher their entrepreneurial intention will be. Their self-efficacy and confidence will also increase, leading to better achievements. The H4 finding provides a practical contribution to understanding social influence and entrepreneurship in the coffee farming sector. In this vein, policymakers, social networks and stakeholders can work on designing interventions that enhance and harness the social influences on entrepreneurs. Social influence initiatives, such as mentorship programmes, community engagement and networking opportunities, can nurture students and provide them with a supportive ecosystem for developing their coffee entrepreneurial skills and knowledge. This support will help them achieve higher levels of determination and resilience in pursuing entrepreneurial endeavours.

Finally, the fifth assumption (H5) assumes a positive connection between ET and CFEI. This hypothesis was approved and supported in [5,55,58]. This finding is logical, as training and education equip the students and potential entrepreneurs with essential tools, necessary skills, knowledge, networks and practical experience, which increase their level of understating and competence, making them more confident and robust. In other words, acquiring skills and knowledge through education and training cultivates a sense of confidence and resilience among students, which positively influences their entrepreneurial aspirations and intentions. Additionally, we conclude that reporting a positive relationship between ET and CFEI indicates that any investments in different educational programmes focusing on coffee farming practices can yield valuable payoffs. Programmes and projects offering knowledge sharing, new idea development, networking, straightforward training and market accessibility can lead to the development of an entrepreneurial spirit among students and potential coffee farmers. This positive finding supports the developed theoretical model and provides essential policy solutions, such as educational initiatives regarding how entrepreneurial ecosystems emerge in the context of coffee production systems.

It is important to note that focusing on the proposed factors mentioned earlier and understanding how they enhance coffee farming entrepreneurial intention will help policymakers, universities, incubation organisations and other stakeholders in the context of the study to design and develop essential policies that support sustainable agricultural practices, contribute to a growing economy and develop an agriculture sector with greater business resilience.

8. Conclusions

While several socioeconomic problems, such as unemployment and poverty, persist worldwide, particularly in developing countries, governments and other official entities continue to direct their efforts toward creating business developmental instruments, including promoting entrepreneurship and the SME sector, as remedies for these issues. Different entrepreneurial business types are promoted worldwide as part of governmental initiatives to support the economy and create new job opportunities. Being a developing economy but looking forward, Saudi Arabia continues to support the entrepreneurship and SME sector in the country, with more emphasis and focus on coffee cultivation and industry. In particular, Saudi Arabia has attempted to develop a prospective coffee industry by encouraging entrepreneurs, farmers, potential entrepreneurs (students) and other interested parties in Arabic coffee to invest in it. It focuses explicitly on developing Arabic coffee production in 15 southern areas, which will become significant hubs for Arabic coffee production.

The Saudi government has established a long-term initiative, Saudi Vision 2030, to plant approximately 1.2 million coffee trees by 2026. Accordingly, and as a part of this movement toward improving the coffee industry in Saudi Arabia, we contributed to this movement through a research model aiming to examine to what extent selected institutions (formal and informal institutions), or what we call external ecosystem factors, play a role in stimulating and enhancing the coffee farming entrepreneurial intention in Saudi Arabia among potential students. For this purpose, a conceptual model was developed, and data were collected from different universities in Saudi Arabia. Hypotheses were developed and tested with the help of various statistical tools. The study reported interesting and sometimes surprising findings, which are discussed in detail in Section 7. The study provides specific practical and theoretical implications for the policy and decision-makers that will help improve coffee cultivation in Saudi Arabia and encourage entrepreneurial intention among students. The study also acknowledges certain limitations and proposed suggestions for future research.

9. Implications

9.1. Theoretical Implications

This is one of the few research studies that propose a conceptual model for investigating the influence of selected external factors, namely access to finance, structural support, physical infrastructure support, social impact and education and training, on stimulating coffee cultivation entrepreneurial intention among potential entrepreneurs or students in Saudi Arabia. This proposed model attempted to provide a clear understanding of the possible factors that, based on the previous literature, may contribute to the development of entrepreneurial intention for pursuing coffee cultivation, which is considered one of the most essential sectors today, both economically and socially. Even though the proposed model did not support all the assumptions, this investigation is believed to combine different frameworks and integrate social, economic, organisational and educational perspectives to provide a clear understanding of the critical factors that develop entrepreneurial intention related to coffee cultivation.

This research has provided some insights for future researchers to understand the key factors that support entrepreneurial intentions among respondents, which can be further refined. It also identified other factors that do not influence coffee cultivation entrepreneurial intentions, thus guiding policymakers to take corrective measures. Furthermore, this research provides guidelines for other researchers to continue investigating additional factors that stimulate entrepreneurial intentions among students, entrepreneurs or farmers, using different variables such as personal traits. Future researchers may collect samples from countries with similar characteristics and compare the findings. They can overcome the limitations of this research by enlarging the sample size, improving the model of the study, changing the research methodology and targeting different respondents.

9.2. Practical Implications

In this section, we glance at the study’s practical implications. We acknowledge that some proposed hypotheses were not accepted as anticipated in the developed model. However, others were supported, and accordingly, their findings provided guidelines for policymakers and other institutions such as universities, colleges, incubators and Saudi coffee companies. These entities can provide more coffee cultivation, entrepreneurial training and financial support to potential entrepreneurs, students and existing entrepreneurs. This support will equip students with essential technical expertise and knowledge that stimulates their coffee farming entrepreneurial intentions, ultimately contributing to the development of coffee cultivation in Saudi Arabia and improving the coffee industry. Agricultural organisations and associations need to create awareness programmes and practical training opportunities for individuals interested in coffee cultivation. We further comment on those insignificant results that we anticipated to have a positive relationship between access to finance, structure support and physical infrastructure support) and entrepreneurial intentions among respondents in Saudi Arabia. Despite the strong reliability and validity of the measures used in the developed model of the study, we obtained insignificant results.

Furthermore, regarding other assumed hypotheses that did not present a positive relationship with coffee farming entrepreneurial intention among the students, we believe the absence of positive relationships does not necessarily indicate the lack of the model fit to the context. Instead, we recommend further and deeper exploration into the external factors affecting coffee farming entrepreneurial intention in the context of the study. This exploration can involve qualitative research methods, such as focus groups and interviews, to deeply understand and capture the opinions and prospects of students about this phenomenon. This qualitative approach will help policymakers to understand and identify the particular considerations and difficulties hindering the development of coffee farming entrepreneurial intention among the students in Saudi Arabia. Accordingly, policymakers can tailor and design specific support mechanisms and interventions more effectively to enhance and foster a conducive business environment for coffee cultivation in Saudi Arabia.

Moreover, despite the belief that this study provided a glance over the key factors influencing potential entrepreneurs’ entrepreneurial intentions, it is essential to note that entrepreneurs might also face some practical challenges during coffee cultivation. For instance, entrepreneurs might face a challenge in choosing suitable coffee varieties to plant that suit the study’s climate. Accordingly, a thorough soil analysis to check and ensure the applicability of the land for coffee cultivation and to understand the suitable coffee varieties in the study area is necessary to ensure coffee business success. These considerations provide an imperative grounding for coffee business cultivation and the long-term success of such businesses, and it is recommended that future research be undertaken.

Author Contributions

A.S.A., Conceptualisation and Writing—original draft. M.M.A., Methodology. E.A., Software and Writing—original draft. F.A., Data curation and Validation. A.H.A.S., Supervision and Project administration. S.H.A.M., Visualisation. A.A.A.-d., Supervision and Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice President for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. A301].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved at the by King Faisal University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Social Influence | ||

| SIF1 | In my country, the creation of new ventures is considered an appropriate way to become rich. | [5] |

| SIF2 | In my country, most people consider becoming an entrepreneur as a desirable career choice. | |

| SIF3 | In my country, successful entrepreneurs have a high level of status and respect. | |

| SIF4 | In my country, you will often see stories in the public media about successful entrepreneurs. | |

| SIF5 | In my country, most people think of entrepreneurs as competent, resourceful individuals. | |

| Physical Infrastructures Support | ||

| API1 | In my country, the physical infrastructure (roads, utilities, communications and waste disposal) provides good support for new and growing firms. | [5] |

| API2 | In my country, it is not too expensive for a new or growing firm to gain good access to communications (phone, internet, etc.). | |

| API3 | In my country, a new or growing firm can gain good access to communications (telephone, internet, etc.) in about a week. | |

| API4 | In my country, new and growing firms can afford the cost of basic utilities (gas, water and electricity). | |

| API5 | In my country, new firms can get access to utilities (gas, water, electricity and sewer) in less time. | |

| Access to Finance | ||

| AF1 | In my country, equity funding is available for new and growing firms. | [5] |

| AF2 | In my country, debt financing is available for new and growing firms. | |

| AF3 | In my country, funding is available from informal investors (family, friends and colleagues), who are private individuals (other than founders) for new and growing firms. | |

| AF4 | In my country, professional business angels funding is available for new and growing firms. | |

| AF5 | In my country, venture capitalist funding is available for new and growing firms. | |

| Education and Training | ||

| ET1 | In my country, teaching in primary and secondary education encourages creativity, self-sufficiency and personal initiative. | [5] |

| ET2 | In my country, teaching in primary and secondary education provides adequate instruction in market economic principles. | |

| ET3 | In my country, teaching in primary and secondary education provides adequate attention to entrepreneurship and new firm creation. | |

| ET4 | In my country, colleges and universities provide good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms. | |

| ET5 | In my country, the level of business and management education provides good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms. | |

| ET6 | In my country, the vocational, professional and continuing education systems provide good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms. | |

| Structure of Institutional Support | ||

| SS1 | The governments have provided us with necessary technology information and support. | [41] |

| SS2 | The governments have provided us with support to seek for financial resources. | |

| SS3 | The governments have provided us with beneficial policies and projects. | |

| SS4 | The governments have provided us with direct financial support such as tax reduction and subsidy. | |

| Coffee Farming Entrepreneurial Intention | ||

| CFEI1 | I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur in the field of coffee farming in Saudi Arabia. | [8] |

| CFEI 2 | My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur in the field of coffee farming in Saudi Arabia. | |

| CFEI3 | I will make every effort to start and run my own firm in the field of coffee farming in Saudi Arabia. | |

| CFEI4 | I am determined to create a firm in the field of coffee farming in Saudi Arabia. | |

| CFEI5 | I have very seriously thought of starting a business in the field of coffee farming in Saudi Arabia. | |

| CFEI6 | I have the firm intention to start a firm someday in the field of coffee farming in Saudi Arabia. | |

References

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.; Abubakar, A.A. Breaking Barriers: The Path to Empowering Women Entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2023, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A.; Seraj, A.H.A. Investigating the Impact of Institutions on Small Business Creation Among Saudi Entrepreneurs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 897787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnadi, M.; Gheith, M.H.; Farag, T. How Does the Perception of Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Affect Entrepreneurial Intention Among University Students In Saudi Arabia? Int. J. Entrep. 2020, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shabeeb; Ammer, M.A.; Elshaer, I.A. Born to Be Green: Antecedents of Green Entrepreneurship Intentions among Higher Education Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Ali, M.; Badghish, S. Symmetric and Asymmetric Modeling of Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Developing Entrepreneurial Intentions among Female university Students in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2019, 11, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Berger, E.S.C.; Mpeqa, A. The more the merrier? Economic freedom and entrepreneurial activity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C. Why Do Some People Choose to Become Entrepreneurs? An Integrative Approach. J. Manag. Policy Pract. 2014, 15, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.-W. Development and Cross-Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.; Liguori, E.W. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: Outcome expectations as mediator and subjective norms as moderator. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat, S.C.; Maat, S.M.; Mohd, N. Identifying Factors that Affecting the Entrepreneurial Intention among Engineering Technology Students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.; Alshallaqi, M. Impact of autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness on students’ intention to start a new venture. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D.; Selcuk, S. Which factors affect entrepreneurial intention of university students? J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2009, 33, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, D.J. How to Start an Entrepreneurial Revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, E.; Mayer, H. The evolutionary dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Urban Stud. 2015, 53, 2118–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufkhani, P.; Wagner, R.; Ismail, W.K.W. Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic review. J. Enterprising Communities 2018, 12, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merwe, K.; Maree, T. The behavioural intentions of specialty coffee consumers in South Africa. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwale, Y.O.; Ababtain, A.K.; Alaraifi, A.A. Structural equation model analysis of factors influencing entrepreneurial interest among university students in Saudi Arabia. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, K. Promoting the Entrepreneurial Success of Women Entrepreneurs Through Education and Training. Sci. J. Educ. 2017, 5, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duysters, G.; Cloodt, M. The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, N.; Braswell, R. Business Women in Saudi Arabia: Characteristics, Challenges, and Aspiration in A Regional Context. Monit. Group 2010, 11, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. Mapping entrepreneurship ecosystem of Saudi Arabia. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 9, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L. Business Wires. Business Wire:Saudi Arabia Coffee Market Report 2022: Rising Number of Initiatives to Increase Coffee Production in Saudi Arabia Presents Opportunities—ResearchAndMarkets.com. 2022. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20221014005170/en/Saudi-Arabia-Coffee-Market-Report-2022-Rising-Number-of-Initiatives-to-Increase-Coffee-Production-in-Saudi-Arabia-Presents-Opportunities—ResearchAndMarkets.com (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Environment, M.O. Initiatives and Programs to Develop Coffee Cultivation in Saudi Arabia. Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture. 2023. Available online: https://www.mewa.gov.sa/en/MediaCenter/News/Pages/engnews2226.aspx#:~:text=The%20Kingdom%E2%80%99s%20target%20is%20to,Rural%20Devel-opment%20Program%20(REF) (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- AbuTheab, K.; Saudi Coffee Company. Saudi Coffee Company Academy: A Brewing Beacon of Excellence in the Coffee Industry. 2023. Available online: https://www.saudicoffee.com/news/saudi-coffee-company-scc-proudly-announces-the-launch-of-its-specialized-academy-aimed-at-empowering-saudi-farmers-entrepreneurs-and-coffee-enthusiasts/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Salian, N. Gulf Business: From Bean to Brew: How Saudi Coffee Company Is Powering the Kingdom’s Coffee Industry. 2023. Available online: https://gulfbusiness.com/saudi-coffee-company-to-support-vision-2030-goals/ (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- North, D. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations, Ideas, Interests and Identities, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, B.S.O. An Appraisal of the Determinants of Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: The Case of the Middle East, North Africa and Selected Gulf Cgooperation Council Nations. Afr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Luc, P.T. The relationship between perceived access to finance and social entrepreneurship intentions among university students in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2018, 5, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, V.D.; Roman, A.; Tudose, M.B. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intentions of Youth: The Role of Access to Finance. Eng. Econ. 2022, 33, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Fally, T.; Scarpetta, S. Credit constraints as a barrier to the entry and post-entry growth of firm. Econ. Policy 2007, 22, 732–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, S.; Indarti, N. Entrepreneurial intention among indonesian and norwegian students. J. Enterprising Cult. 2004, 12, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesen, H. Personality or environment? A comprehensive study on the entrepreneurial intentions of university students. Educ. Train. 2013, 55, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T. The Impact of Access to Finance and Environmental Factors on Entrepreneurial Intention: The Mediator Role of Entrepreneurial Behavioural Control. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2020, 8, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami; Al Marri, S. The Impact of Financial Literacy on Entrepreneurial Intention: The Mediating Role of Saving Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 911605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal-Suñé, A.; López-Panisello, M.-B. Institutional and economic determinants of the perception of opportunities and entrepreneurial intention. Investig. Reg. 2013, 26, 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wennekers, S.; Thurik, R. Linking Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Small Bus. Econ. 1999, 13, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelard; Saleh, K.E. Impact of some contextual factors on entrepreneurial intention of university students. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 10707–10717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denanyoh, R.; Adjei, K.; Nyemekye, G.E. Factors That Impact on Entrepreneurial Intention of Tertiary Students in Ghana. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2015, 5, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, C.; De Clercq, D.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C. Government institutional support, entrepreneurial orientation, strategic renewal, and firm performance in transitional China. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Tajddini, K.; Rehman, K.; Ali, J.F.; Ahmed, I. University Student’s inclination of Governance and its Effects on Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Empirical Analysis. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2010, 1, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Camelo-Ordaz, C.; Diánez-González, J.P.; Franco-Leal, N.; Ruiz-Navarro, J. Recognition of Entrepreneurial Opportunity using a Socio-cognitive Approach. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2020, 38, 718–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Heger, D.; Veith, T. Infrastructure and entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.L. Infrastructure investments and entrepreneurial dynamism in the U.S. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, J.L. The Creation and Configuration of Infrastructure for Entrepreneurship in Emerging Domains of Activity. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 38, 721–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, D.; Ven, H. The development of an infrastructure for entrepreneurship Journal of Business Venturing. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, D.; Aparicio, S.; Audretsch, D. Twenty-five years of research on institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: What has been learned? Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 53, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahban, M.A.; Ramalu, S.S.; Syahputra, R. The Influence of Social Support on Entrepreneurial Inclination among Business Students in Indonesia. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 2016, 8, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turulja, L.; Veselinovic, L.; Agic, E.; Pasic-Mesihovic, A. Entrepreneurial intention of students in Bosnia and Herzegovina: What type of support matters? Econ. Res. Istraz. 2020, 33, 2713–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, W.S.; Lo, E.S.C. Cultural contingency in the cognitive model of entrepreneurial intention. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhman, W.; Ahamed, F. The role of social and psychological factors on entrepreneurial intention among islamic college students in Indonesia. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2015, 3, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F.J.; Chamorro-Mera, A.; Rubio, S. Academic entrepreneurship in Spanish universities: An analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial intention. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekule, L.; Cekuls, A.; Dunska, M. The role of education in fostering entrepreneurial intentions among business students. Int. Conf. High. Educ. Adv. 2023, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixiová, Z.; PII, T.K. Training, human capital, and gender gaps in entrepreneurial performance. Econ. Model. 2019, 85, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küttim, M.; Kallaste, M.; Venesaar, U.; Kiis, A. Entrepreneurship Education at University Level and Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 110, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levie, J.D.; Hart, M.; Anyadyke-Danes, M. The effect of business or enterprise training on opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial skills of graduates and non-graduates in the UK. Front. Entrep. Res. 2010, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.; Phan, P. Analyzing the Effectiveness of University Technology Transfer: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education. Adv. Study Entrep. Innov. Econ. Growth 2005, 18, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2015, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Statistical Question: Convenience: Convenience sampling. BMJ 2013, 347, f6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair; Hult; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Risher, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, V.; Sinkovics, R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing the Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).