Abstract

This study explores the environmental behavior disparities between urban and rural residents in China due to socioeconomic status differences amidst social governance and institutional reform. Using OLS regression models on the 2021 China General Social Survey (CGSS) data, it analyzes the impact of socioeconomic status on environmental behaviors. This study reveals that urban residents generally exhibit better environmental behaviors than rural residents. Education and income are identified as critical drivers, with education raising environmental awareness and income driving participation in environmental activities. Urban residents benefit more from these factors. The policy recommendations are for the government to enhance rural education resources and improve education quality, ensuring that education poverty alleviation policies are effectively implemented to support rural development. Simultaneously, promoting rural economic growth and narrowing the urban–rural economic gap is crucial for improving rural environmental behavior and achieving urban–rural environmental harmony. Furthermore, the results call on the international community to focus on environmental governance systems, aiming to provide references for other developing countries in formulating environmental policies, thereby promoting the creation of a more just, eco-friendly, and sustainable global development framework.

1. Introduction

The Civic Ecological Behavior Survey Report (2021), released in 2021, profoundly reveals significant disparities among the Chinese public in terms of environmental awareness and practical actions. The report indicates that the public generally demonstrates strong environmental responsibility and willingness to engage in environmental protection, with over half of the respondents acknowledging possessing the basic capability, resources, and opportunities to undertake environmental behaviors. However, a noteworthy contradiction emerges: despite a high 72.3% of respondents expressing a deep desire to contribute more to environmental protection, many face challenges in identifying actionable pathways. From the traditional sociological perspective, socioeconomic status constitutes a core dimension in assessing the ‘resources’ an individual possesses and is considered an explanatory factor driving changes in behavior patterns. Following this line of reasoning, theoretically, enhancing an individual’s economic and cultural capital would lead to a shift in environmental behaviors [1]. However, this hypothesis overlooks the complexity inherent in behavioral transitions, including but not limited to the accessibility of information channels, the influence of social norms, and the diversity of individual values and motivations, indicating that promoting environmental behaviors requires a comprehensive consideration of multiple dimensions of societal and individual factors.

China’s vast land area has nurtured bustling cities and fertile rural areas, witnessing sweeping historical transformations from planned to market economies. This historical process reveals the increasingly prominent dualistic characteristics of China’s urban–rural structure, which has not only served as a driving force promoting the country’s leap into modernization but has also invisibly catalyzed persistent urban–rural environmental disparities. At its core, the crux of environmental challenges lies in the essence of human behavioral patterns [2]. Given this context, achieving sustainable environmental improvement necessitates fundamental shifts in human behavior. With the deepening transformation of Chinese society, disparities in resource allocation, development trajectories, and lifestyles between urban and rural areas have become more pronounced, delineating a unique and distinct urban–rural environmental dualistic landscape. This structure not only widens the urban–rural development gap but also presents complex challenges to ecological balance and social harmony. The significant disparities in education and income among urban and rural residents not only reflect the diversity and complexity of social structures but also directly shape their divergent orientations in environmental behavior choices. At the micro level, individual environmental awareness levels are constrained by factors such as gender, age, education level, income level, occupation type, workplace, residential location, and religious beliefs. At the structural level, the formation of public environmental awareness is the result of the comprehensive interaction of multiple factors involving socioeconomic development levels, environmental issues, levels of environmental scientific development, dominant values, government management systems, media influence, environmental education promotion, and efforts in environmental protection [3]. From a broader perspective, comparative studies of urban–rural environmental issues have become an integral part of research on social governance innovation and institutional reform. Under China’s unique urban–rural development pattern, the socioeconomic status and structural disparities of residents have significantly influenced environmental behaviors. This exploration of environmental issues embedded in China’s structural disparities and urban–rural regional development patterns represents a meaningful investigation of China’s experience [4]. This perspective not only enriches our understanding of the causes of environmental issues but also provides valuable insights for China and the global community, guiding deeper exploration of the origins of problems and strategies for addressing them, thereby adding significant value to China’s unique contributions to environmental governance.

In 2021, China announced the successful completion of a moderately prosperous society, a milestone that marks a significant turning point in the nation’s development trajectory and signals profound adjustments to the urban–rural dual structure. Simultaneously, the Chinese government’s rural revitalization strategy has long aimed at bridging the gap in resource distribution between urban and rural areas. Consequently, as times change, existing research findings may no longer adequately explain the social phenomena of the new era; the development of socioeconomic conditions and the improvement in education levels may have had a differentiated impact on the environmental behaviors of urban and rural residents, which forms the starting point of this study. In this period of transformation, a deep analysis of the new trends and shifts in environmental behavior among urban and rural residents, leading to the development of new theories, is the innovative aspect of this study. The concept of socioeconomic status encompasses rich and diverse connotations, involving not only tangible economic indicators such as income but also abstract and difficult-to-quantify important dimensions such as educational levels [5].

Building on the previous discussion, this study centers on two core dimensions: educational background and economic income, meticulously exploring the intrinsic relationship between socioeconomic status and environmental behavior. The analysis is divided into three specific subtopics: (1) Investigating whether there are significant differences among urban and rural residents in environmental protection actions, involving comparisons across multiple dimensions such as lifestyles, values, and accessibility of resources. (2) Analyzing how socioeconomic status shapes individual environmental behavior patterns, particularly how education and income act as mediating variables influencing people’s cognition and responses to environmental issues. (3) Elucidating the mechanisms of influence on environmental behaviors among urban and rural residents under diverse socioeconomic conditions, revealing how regional, economic, and educational factors interact, thereby guiding differentiated paths of environmental behavior. By deeply exploring these issues, this article aims not only to enhance our understanding of the deep-seated social structural roots of environmental issues but also to provide solid theoretical foundations and practical guidance for the formulation and implementation of environmental policies, thereby promoting the construction of a more precise and effective environmental governance system.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES), also known as social class, is a key concept determining individuals’ or groups’ positions within social structures, long regarded as a decisive factor influencing psychological states and life outcomes. From a temporal perspective, both Marx in the 19th century and Weber in the early 20th century regarded SES as the foundation for differences in social power, prestige divisions, cultural preferences, and political stances. These differences stem from the roles people play, the groups they belong to, or their individual characteristics [6]. In the mid-20th century, the ‘resource’ theory, further developed by Duncan and others [7,8,9], focused on core dimensions such as income, education, and occupational prestige, attempting to integrate these elements into a unified measurement scale. However, with the advent of the 21st century, new academic trends within psychology and public health advocate for moving away from generalized comprehensive measures of SES toward individual indicators such as income level, educational attainment, or occupational prestige as criteria for assessment. The logic behind this academic shift lies in the existence of more direct and clearer theoretical connections between specific indicators and particular outcomes [10,11,12,13,14]. It aims to enhance the precision and specificity of research, deepening the academic understanding of how socioeconomic status specifically shapes individual psychological states and quality of life. This methodological innovation not only challenges the traditional SES measurement framework but also actively responds to the modern social sciences’ trend toward more refined and personalized research. The concept of socioeconomic status has undergone profound conceptual reshaping in psychological theory, closely integrating advances in measurement theory [15,16,17] and synergizing insights from psychology [18], sociology [19,20,21], public health [11,13,14], and other disciplines to collectively address a long-standing academic challenge. Interdisciplinary research has historically centered on constructing analytical frameworks around socioeconomic status [7,22,23], using individuals’ education levels and income as cornerstones to derive socioeconomic status indicators for various occupations. Studies indicate that this comprehensive indicator, the Socioeconomic Index (SEI), not only effectively measures social status but also carries high levels of recognition and objectivity. Income is considered a direct measure of economic well-being, while education symbolizes social identity and status [24]. From a deep theoretical analysis, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory [25] emphasizes a sequential process of needs development from basic physiological needs to higher-level self-actualization needs. In essence, individuals, once basic survival needs such as food, shelter, and security are met, progress hierarchically to pursue the satisfaction of higher psychological and self-worth needs. Applying this theory to the discussion of environmental protection reveals a clear trend: individuals with superior economic conditions, benefiting from ample resources and leisure time, are more inclined to focus on environmental conservation issues and are more adept at implementing environmental conservation actions. This phenomenon highlights the positive incentivizing role of abundant economic resources in promoting environmentally friendly behavior, further demonstrating the close and intricate relationship between socioeconomic status and environmental protection behaviors.

2.2. Residents’ Environmental Behaviors

In the field of behavioral science, the role of environmental factors is widely emphasized. It is believed that the environment continuously influences behavior, while behavior, in turn, exerts ongoing effects on the environment. In fact, one of the primary objectives of behavior is to impact the environment, meaning that harming the environment is tantamount to harming ourselves [26]. Residents’ environmental behaviors refer to a series of activities undertaken by individuals or households in their daily practices aimed at maintaining, improving, or protecting environmental quality. The complexity and diversity of ecosystems have profound impacts on individual behavior and the challenges faced. From micro-level biological interactions to macro-level climate and environmental changes, each factor shapes human behavior patterns and social structures in various ways [27].

Within the academic community in China, there exists a distinction between broad and narrow understandings of the concept of ‘environmental behavior.’ Broadly, environmental behavior comprehensively covers both aspects of environmental protection and environmental degradation [28], presenting a comprehensive spectrum of behaviors. A more refined classification divides environmental behavior into three main categories: environmental impact behavior, environmental degradation behavior, and environmental protection behavior, emphasizing that protective behavior is just one branch under the broader category of environmental behavior [29]. Conversely, a narrow perspective often focuses on environmental protection behavior, considering it the core focus of environmental behavior research. Despite ongoing debates within academia over the definition of environmental behavior, there is general consensus on the active and practical participation of individuals in environmental protection and issue prevention [30].

Research often deconstructs environmental behavior into two dimensions: personal daily environmental conservation behaviors and environmental participation behaviors [31]. Alternatively, it may delineate behaviors across three specific dimensions, environmental protection, resource recycling, and energy conservation, to comprehensively capture the multidimensional characteristics of residents’ environmental conservation behaviors [32]. Building upon this foundation, the concept of ‘pro-environmental behavior’ emerged to describe spontaneous individual or collective actions in daily life aimed at promoting environmental sustainability [33,34,35]. Pro-environmental behavior plays a pivotal role in mitigating natural resource consumption, reducing pollution emissions, and alleviating environmental degradation, serving as a crucial practical strategy for addressing environmental challenges and ensuring long-term environmental health [36,37].

From a Western perspective, researchers have defined environmental behavior as a conscious effort to minimize the negative impact of personal activities on the environment [38]. In demographic terms, individual environmental behavior is deeply shaped by various social demographic factors, including but not limited to educational background, gender, age, and income, as well as attitudes and values that collectively weave into a complex network influencing decisions on environmental behavior [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Regarding age factors, academia presents diverse perspectives. While some studies suggest that older age groups show more proactive environmental behaviors, implying an increase in environmental awareness with age, other research overturns this empirical finding [47], revealing the complexity and variability in the relationship between age and environmental behavior. This suggests that the specific impact of age on environmental behavior may be moderated by various underexplored variables.

Furthermore, environmental behavior is subdivided into several core categories [48], including persuasive behavior, which influences others through communication and education; financial or consumer behavior, focusing on green consumption choices; ecological management behavior, involving direct environmental conservation practices; legal compliance behavior, emphasizing adherence to environmental regulations; and political behavior, which involves advocating for environmentally friendly policies through policy initiatives and voting.

To date, a widely accepted standard framework for assessing residents’ environmental behaviors has yet to be consolidated within the industry. Against this backdrop, the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) proposed by Dunlap is particularly significant [49]. This paradigm, articulated and popularized through Dunlap’s pioneering research, has gained significant recognition and influence in the academic field. The NEP not only innovatively interprets an environmental values perspective but also evolves into a core methodological tool for exploring the correlation between individual environmental beliefs and actual environmental behaviors [50]. Tanner et al.’s research further strengthens the applied value of this theory, robustly confirming a close and significant correlation between environmental beliefs and behaviors through precise application of the NEP scale [51], deepening scholarly understanding of the dynamic link between the two. Inspired by the NEP scale, Professor Hong designed and implemented a comprehensive survey tailored to the unique background of Chinese residents. This study not only deepened insights into the current state of environmental awareness among the Chinese public but also laid a solid foundation and provided highly valuable reference paths and data support for subsequent explorations of related topics [3].

2.3. The Influence of Socioeconomic Status on Environmental Behaviors of Urban and Rural Residents

Differences in socioeconomic status distinctly delineate environmental protection behaviors among various societal groups, manifesting not only in their observable actions but also subtly through diverse channels of environmental information acquisition, thereby indirectly influencing their respective environmental inclinations [52]. Existing studies have used educational background and income as key indicators to measure the intrinsic link between socioeconomic status and environmental behavior. The findings indicate a positive correlation between higher levels of education and proactive environmental measures taken in personal domains [34], suggesting that educational attainment stimulates individuals to adopt more active environmental strategies, particularly in identifying and addressing environmental threats. However, when it comes to more assertive public environmental actions such as petitions and protests, the influence of education levels appears less significant [53].

Regarding income, some studies emphasize its long-term and significant role in driving deeper environmental behaviors, which often require higher levels of cognitive involvement and resource dedication. In contrast, the impact of income levels on simple or superficial environmental behaviors seems weak or negligible [54]. Adequate personal wealth has been observed to significantly promote residents’ participation in various forms of environmental activities, especially those involving personal expression and active engagement in environmental advocacy [53]. Nevertheless, it is crucial to note dissenting voices in academia, pointing out that the link between personal income and environmental behavior is not straightforward, emphasizing the moderating effects of other socio-cultural factors and the complexity of individual differences [34].

In Western academic explorations from the 1980s to the early 1990s, urban residents exhibited greater environmental concern compared to rural residents [55,56,57]. Factors contributing to this phenomenon are diverse and intertwined, including higher economic incomes, superior educational conditions, and more immediate environmental challenges faced by urban residents, all of which contribute to their greater inclination toward environmental protection [58,59]. In contrast, rural community residents, constrained by lower educational attainment and relatively constrained economic conditions, tend to emphasize pragmatism, focusing on pursuing economic growth to improve living conditions, thus paying less attention to environmental issues [59]. From an environmental concern perspective, urban and rural residents also exhibit differentiated focuses. Urban residents, due to frequent encounters with issues like water and air pollution affecting daily life, are highly sensitive to topics such as drinking water safety and air quality. In contrast, rural residents’ environmental awareness is rooted more in concerns directly affecting their livelihoods and the health of traditional natural ecosystems, such as land degradation and water resource management, which are integral to their lives and work [60].

However, it is noteworthy that academic research reveals a diverse picture of differences in environmental concern between urban and rural areas across different regions and countries. For instance, Jones’ detailed analysis of Southern US data found no significant difference in environmental concern between urban and rural residents after controlling for demographic variables [59]. Research by Dunlap and others further supplements this, suggesting that the determining role of residence (urban or rural) in individual environmental awareness seems to be gradually diminishing [61]. Moreover, studies based on Canadian data illustrate a reverse trend: in some cases, rural residents not only match but even exhibit higher levels of environmental concern than urban residents. This phenomenon is likely propelled by the gradual improvement in rural environmental management services and facilities in recent years, stimulating stronger environmental awareness and more proactive environmental engagement within rural communities [62].

The impact of socioeconomic status on environmental behaviors is complex and diverse, encompassing both direct behavioral manifestations and indirect pathways of information acquisition. It is influenced by multiple factors, such as educational attainment and income levels. To further explore this issue empirically, this study utilizes data from the authoritative Chinese General Social Survey 2021 to elucidate how socioeconomic status influences the environmental behavior of urban and rural residents and the differentiated pathways therein.

2.4. Literature Review Comments

Current research on the influence of socioeconomic status (SES) on environmental behavior among urban and rural residents is abundant, yet there remains room for further discussion. It is widely acknowledged that the higher an individual’s socioeconomic status, the more pronounced their pro-environmental behavior tends to be. However, the significant socioeconomic differences between urban and rural areas may result in urban residents having higher environmental behavior scores than rural residents. In the context of China’s urban–rural dual structure transformation, whether the previous conclusions about environmental behavior still hold true for both urban and rural residents is a question that requires further investigation. Additionally, the mediating mechanisms and factors influencing the environmental behavior of urban and rural residents are likely to change, forming a gap that this study aims to address.

Moreover, the influence of socioeconomic status on environmental behavior is complex and multifaceted, involving not only direct behavioral expressions but also indirect channels of information acquisition. Factors such as education level and income may also exert a combined effect. To explore these issues in greater depth, this study utilizes data from the China General Social Survey (CGSS 2021), a widely recognized and authoritative source in the field of empirical social science research in China. The aim is to empirically reveal how socioeconomic status influences the environmental behavior of urban and rural residents and to identify the differentiated pathways between them. This not only forms the core of the article’s inquiry but also fills a gap in existing research.

3. Research Hypotheses

At the data analysis technical level, this study uses IBM SPSS 26 statistical software to process and analyze the data to reveal how the multi-level structural differences in socioeconomic status dynamically shape and influence the environmental behavior patterns of urban and rural residents.

After the launch of GOES, The Global Environmental Survey, data from the Chinese research team show that the differences in environmental awareness and attitudes between urban and rural residents are quite evident [63]. Scholars have discerned that behind this differentiation lie deep-seated differences in educational attainment, personal income levels, environmental concern, and environmental awareness, which collectively and profoundly influence people’s environmental behavior [64]. Western academia has long confirmed that, in comparison, individuals with lower socioeconomic status are more inclined to accept larger discounts [65]. Urban residents, benefiting from their higher educational background and economic income, often have more extensive environmental knowledge and information sources, such as internet media and environmental knowledge. These advantageous conditions become crucial catalysts driving them to take more environmental actions [66], thus showing that urban residents are more proactive in environmental practices compared to rural residents. This demonstrates that urban residents generally exhibit more pro-environmental behavior than rural residents. On a deeper level, from an economic perspective, rural areas, as relatively lagging segments in socioeconomic development, have residents whose more urgent current need is the rapid expansion of economic scale, thus inevitably showing a lack of attention to environmental issues. Based on the above theoretical framework and empirical observations, we can propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

There are significant differences in environmental behavior between urban and rural residents.

Hypothesis 1.1.

The environmental behavior scores of urban residents are higher than those of rural residents.

3.1. The Impact of Educational Attainment on the Differences in Environmental Behavior between Urban and Rural Residents

As two core indicators of measuring individual economic status, educational attainment and income level significantly distinguish the differences in environmental behavior tendencies between urban and rural residents within the unique urban–rural dual economic structure of China. Specifically, the deepening of educational attainment shows the following characteristics in shaping environmental behavior.

First, a high level of education is often accompanied by a profound understanding and acceptance of mainstream social values, making individuals more likely to recognize and practice concern for public welfare, including the global public issue of environmental protection [67]. Furthermore, as educational attainment increases, individuals gain access to a richer array of social and cultural capital. This not only means they have more channels and resources for obtaining information but also more ‘social capital’ that can be utilized for environmental protection. As Bourdieu conceptualizes social capital as a collection of actual or potential resources [68], it can be understood as the transformation between economic capital, cultural capital, social capital, and symbolic capital [69]. Therefore, the stock of resources an individual possesses influences their pro-environmental behavior. In other words, the more social capital accumulated, the more likely residents are to join environmental organizations, make donations for environmental causes, or directly participate in environmental activities. The cultivation of environmental concepts in their educational background, coupled with higher economic capabilities, jointly enhances this group’s awareness and sense of urgency regarding environmental crises. At the same time, groups with high socioeconomic status, benefiting from quality educational resources and superior working environments, are often more intuitively aware of the importance of sustainable development and practice green consumption and low-carbon lifestyles in their daily lives. These behaviors are not only a reflection of personal choice but also a result of the combined effects of their economic capabilities and educational background, further highlighting the key role of education and income in promoting the formation of environmentally friendly behavior patterns. The difference in socioeconomic status between urban and rural residents leads to variations in their environmental behavior. Among urban residents, those with higher socioeconomic status are more likely to engage in environmental protection actions through collective and structured approaches, thanks to their abundant resources, opportunities, and broad social interactions. Conversely, in rural settings, constrained by lower socioeconomic status, residents are primarily concerned with meeting basic living needs, which may limit their awareness and action on environmental protection. The scarcity of environmental education and information resources further exacerbates their difficulty in participating in environmental activities. Existing research examining the impact of educational background on environmental behavior has not fully considered the imbalance in educational opportunities and quality within the urban–rural dual structure. The significant differences in the allocation of educational resources between urban and rural areas, including the tilt toward quality teaching staff, directly result in urban residents generally enjoying higher-quality education. This not only enhances their environmental awareness but also provides more opportunities for practicing environmental behaviors. In contrast, due to limited educational resources, rural residents often need to achieve a greater leap in educational attainment to gradually close the gap with urban residents in the practice of environmental behaviors. Based on this, this study proposes several hypotheses aimed at deeply analyzing the multifaceted interactions between socioeconomic status and environmental behavior from a novel perspective. It is important to emphasize that, within the framework of the stark contrast between urban and rural differences, this study strives to accurately diagnose the subtle differences and dynamic balance in their relationship. The aim is not only to enrich the academic understanding of environmental sociology theoretically but also to promote positive transformations in the socioeconomic structure at the practical level, encouraging nationwide participation in environmental protection actions and collectively moving toward a sustainable future.

Hypothesis 2.

Education has a positive effect on the environmental behavior of urban and rural residents.

Hypothesis 2.1.

The higher the level of education, the more likely individuals are to engage in favorable environmental behavior.

Hypothesis 2.2.

Compared to residents with low education levels, those with higher education levels can better narrow the gap in environmental behavior between urban and rural residents.

Hypothesis 2.3.

Among individuals with the same level of education, urban residents have higher environmental behavior scores than rural residents.

3.2. The Impact of Income Levels on the Differences in Environmental Behavior between Urban and Rural Residents

Income, as a core component of socioeconomic status, has profound research value in its influence on individual environmental behavior. Firstly, according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, the pursuit of environmental quality is often considered a higher-level need, which only becomes a focus of attention when an individual’s income surpasses a certain threshold [70]. Consequently, individuals with higher socioeconomic status are more inclined to participate in activities such as petitions or environmental organizations [71,72,73]. In contrast, although groups with lower SES may exhibit a higher degree of concern about environmental threats, they reveal a relatively lower willingness to take actual actions to protect the environment compared to high-income and high-education groups [74,75].

When exploring how income differences shape different paths of environmental behavior between urban and rural areas, the research points out that due to the higher level of economic development in cities, high-income groups are more likely to adopt ‘post-materialist’ value orientations. They tend to regard environmental quality as an important part of quality of life, actively participate in community environmental affairs, and take effective measures. Conversely, although rural areas have experienced income growth, the relative lag in development stages means that most residents still adhere to a ‘materialist’ orientation [76]. The incentive mechanisms for environmental behavior are relatively weak, and income growth does not significantly promote the enthusiasm for environmental protection behavior as much as it does for urban residents. Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

The impact of income on the environmental behavior of urban and rural residents shows significant differences, with both having positive effects.

Hypothesis 3.1.

The higher the income level, the more likely individuals are to engage in environmentally friendly behavior.

Hypothesis 3.2.

Compared to residents with low income levels, those with higher income levels can better narrow the gap in environmental behavior between urban and rural residents.

Hypothesis 3.3.

At the same income level, urban residents score better in environmental behavior than rural residents.

4. Data and Measurement

4.1. Data Sources

This study employs quantitative analysis, utilizing data from the 2021 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS2021), which was compiled by the China Survey and Data Center at Renmin University of China. The CGSS is a systematic and comprehensive social survey project designed to reflect various aspects of Chinese society, including communities, families, and individuals. It is highly regarded for its thoroughness and authority (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study location.

The reason for selecting the 2021 data as the research sample is that it represents the latest available data in the database. The survey adopts a multi-angle stratified sampling method, covering a wide range of samples from 19 provinces (municipalities and autonomous regions), including 2 municipalities, 14 provinces, and 3 autonomous regions. It also includes a broad sample of both urban and rural areas to ensure the comprehensiveness, representativeness, and comparability of the data. The questionnaire was quantified using the Likert scale and randomly assigned to selected sample groups for response. The reliability and validity of the sample were verified by the China Survey and Data Center, resulting in 8148 valid samples being collected.

After data cleaning and processing, including the removal of invalid responses and the handling of missing values, this study selected residents aged 22 to 69 as the analysis subjects, yielding a final valid sample of 1118. Among this sample, 45.9% were male, and 54.1% were female. Agricultural household registration accounted for 70.8%, with 46.6% male and 53.4% female, while non-agricultural household registration accounted for 29.2%, with 44.0% male and 56.0% female.

It should be clarified that the number of rural samples is significantly higher than that of urban samples. This difference is mainly due to two factors: first, China’s unique urban–rural dual structure, where rural areas face distinct environmental challenges and opportunities. Increasing the number of rural household samples helps to reveal the unique characteristics of rural environmental behavior, providing a basis for developing environmental policies that are more aligned with rural realities. Second, the availability and richness of the data also influence the sample composition. In the CGSS 2021 dataset, the data for rural household samples are more abundant and detailed, providing strong support for understanding environmental behavior in rural areas. Although the number of urban household samples is relatively smaller, our research design ensures that the sample is representative in other important dimensions (such as age, gender, and education level), so the overall sample can be considered balanced.

4.2. Statistical Description

4.2.1. Dependent Variables and Their Measurement

According to a questionnaire item, this question mainly investigates whether individuals have engaged in certain environmental activities or behaviors, including nine questions mixed with scales and options. The options include ‘Yes’ and ‘No’; ‘Have’ and ‘Have not’; ‘Very willing’, ‘Quite willing’, ‘Uncertain’, ‘Not very willing’, and ‘Very unwilling’; ‘Always’, ‘Often’, ‘Sometimes’, and ‘Never’, totaling four categories. Following the principle of semantic positivity, these were scored, and the total score for this item based on respondents’ answers forms the continuous variable ‘environmental behavior’. The value range for this item is 0–50, with higher scores indicating more favorable environmental behavior. According to a questionnaire item, this question mainly investigates whether individuals have engaged in certain environmental activities or behaviors, including nine questions with scales and options. The options include ‘Yes’ and ‘No’; ‘Have’ and ‘Have not’; ‘Very willing’, ‘Quite willing’, ‘Not sure’, ‘Not very willing’, and ‘Very unwilling’; ‘Always’, ‘Often’, ‘Sometimes’, and ‘Never’, totaling four categories. Based on the principle of semantic positivity, these were scored, and the total score for this item based on respondents’ answers forms the continuous variable ‘environmental behavior’. The value range for this item is 0–50, with higher scores indicating more favorable environmental behavior.

4.2.2. Independent Variables and Their Measurement

The independent variable is socioeconomic status, mainly operationalized as education level and income level. Education level is measured by ‘A7a: What is your highest level of education?’, with options consolidated into primary school or below, junior high school, high school or vocational school, and junior college or above, using primary school or below as the reference variable.

Income level is categorized using the quartile method based on respondents’ total personal income from the previous year. Income below 2000 CNY is classified as low income, 2000 CNY to just under 20,000 CNY as lower-middle income, 20,000 CNY to just under 50,000 CNY as upper-middle income, and above 50,000 CNY as high income, with low income serving as the reference group.

4.2.3. Control Variables

To accurately analyze the relationship between independent and dependent variables, control variables were introduced in variable determination to verify causality. In causal relationship research, control variables help verify the causality between independent and dependent variables. By controlling for other variables that may affect the dependent variable, researchers can be more confident that the observed changes are due to changes in the independent variable. This study draws on previous research to control for variables affecting the environmental behavior of urban and rural residents, focusing mainly on individual characteristics. Firstly, gender is treated as a binary dummy variable, using females as the reference to compare and analyze potential differences in environmental behavior between males and females. Here, females are coded as 1, and males are coded as 2. Here, females are coded as 1, and males are coded as 2. Secondly, household registration is set as a categorical variable, using agricultural household registration as the reference: agricultural household = 1, non-agricultural household = 2. Thirdly, age is a continuous variable.

The reasons for including these three as control variables are as follows: firstly, gender differences are significant not only biologically but also behaviorally, which may influence behavior patterns such as the environmental behavior discussed in this study. If gender is not considered as a control variable, the research results may be affected by gender bias. By considering gender as a control variable, this study can more comprehensively understand phenomena and trends within different gender groups, thereby enhancing the generalizability and applicability of the research. Secondly, household registration is often closely related to social stratification and inequality. In China, household registration is divided into agricultural (rural) and non-agricultural (urban), which, to some extent, determines residents’ rights and benefits in education, healthcare, and social security. Secondly, household registration is often closely related to social stratification and inequality. Therefore, to accurately assess the impact of education level and income on the environmental behavior of urban and rural residents, household registration needs to be used as a control variable to eliminate potential interference caused by differences in household registration. The reason for selecting age as a control variable is twofold: on the one hand, cognitive abilities may change with age, potentially affecting residents’ environmental behavior, making it necessary to control for age to reduce these potential influences. On the other hand, there are differences in social experiences. Individuals in different age groups may have experienced different social events and historical periods, which may influence their behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs. By controlling for age, the variation caused by differences in social experiences can be reduced.

5. Data Analysis Results

5.1. Interaction Analysis

The definitions and descriptions of the main variables are shown in Table 1. The descriptive statistics for the continuous variables of urban and rural residents are shown in Table 2, and the descriptive statistics for the categorical variables of urban and rural residents are shown in Table 3.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of key variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of categorical variables for rural and urban residents: education level, income level, and gender.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of continuous variables for rural and urban residents.

Table 1 provides a detailed descriptive statistical overview of the key variables in the urban and rural resident samples, covering all study subjects. Specifically, the environmental behavior score, with a range set between 1 and 5 points, has an overall average score of 34.22, indicating a moderately high level of participation in environmental behaviors, with a standard deviation of 3.99, showing moderate variability among individuals.

For the income level indicator, this study uses total annual personal income as the quantification standard. The data show an average value of 61,667.49 CNY, with the highest value reaching 9,999,300 CNY, reflecting the rapid economic development in China in recent years. The coordinated rapid growth of urban and rural economies has undoubtedly been a key factor in the significant increase in residents’ incomes compared to the past, highlighting the overall improvement in the country’s economic strength and the significant enhancement of people’s living standards.

When considering the education level variable, the scale is set from 1 to 4, with the overall sample’s average education level at 2.46 and a standard deviation of 1.10, indicating moderate variability in educational backgrounds. Further breakdown shows that the average education level for rural residents is 1.97, with a standard deviation of 0.95, while the corresponding data for urban residents are 2.20 and 0.95 (see Table 2). This stark contrast reveals that urban residents generally have higher education levels than rural residents, confirming the significant disparities in educational resources and opportunities between urban and rural areas.

In Table 1, the overview shows that the mean for gender is 1.54, with a standard deviation of 0.50, and the data range between a maximum of 2 and a minimum of 1, reflecting a balanced gender distribution in the sample. The measurement of the household registration attribute uses values of 1 and 2, with a mean of 1.29 and a standard deviation of 0.46, also showing a certain balance in distribution, with the maximum and minimum values aligning with the value range. Further analysis of the gender environmental scores for urban and rural residents in Table 2. shows that the average score for rural residents is 1.97, with a standard deviation of 0.95, indicating some variability in this indicator in rural areas. In contrast, urban residents have an average gender environment score of 1.56 with a smaller standard deviation of 0.50, revealing that gender scores in urban areas are not only relatively low in overall level but also more concentrated with less variability.

Regarding the age variable, Table 1 data from the total sample show a mean of 47.26 years with a standard deviation of 13.07 years. The age spans from the youngest at 22 years to the oldest at 69 years, depicting the diversity of the sample in terms of age composition.

Combined with age distribution data from Table 3, the results indicate that the age means and standard deviations among the three sample groups are similar, implying a relatively balanced distribution of age composition in the sample.

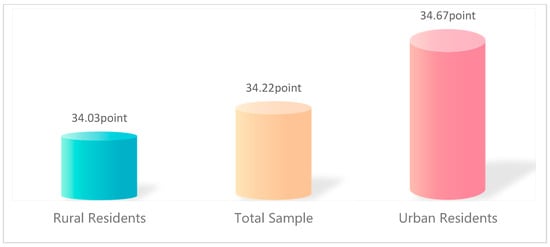

An in-depth exploration of the age composition of urban and rural populations reveals that the average environmental behavior scores for rural and urban residents are 34.03 and 34.67, respectively (see Figure 2). The analysis indicates that rural residents indeed lag behind the overall sample average, while urban residents not only exceed this benchmark but also slightly surpass rural residents in environmental behavior scores. This finding partially supports Hypothesis 1.

Figure 2.

Environmental behavior score for rural and urban residents.

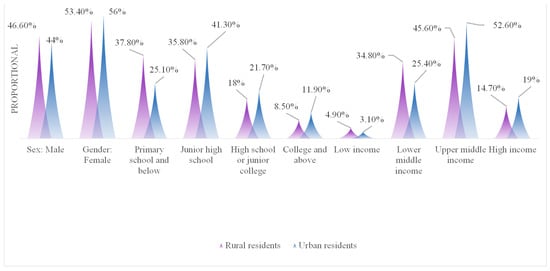

According to the total sample data in Table 4 (see Figure 3), rural and urban residents’ environmental behavior scores show females slightly outnumbering males at 54.1% versus 45.9%. In terms of educational attainment, the junior high school education level ranks highest at 34.1%, while college and above is the lowest, at 9.5%. Primary school and below and high school or technical school education groups account for 34.1%, 37.4%, 19.1%, and 9.5%, respectively, reflecting the diversity and room for improvement in educational structure. In terms of income distribution, the middle-to-high income group dominates at 47.7%, while the low-income group accounts for only 4.4%. The middle to low-income and high-income groups account for 32.0% and 15.9%, respectively, reflecting significant income distribution differences.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of categorical variables for urban and rural residents.

Figure 3.

Descriptive statistics on the percentage of categorical variables for urban and rural residents.

Turning to the sample analysis of rural residents, females account for 53.4% and males for 46.6% of the gender composition. The educational background highlights the uneven distribution of educational resources, with the highest proportion having primary school education or below, at 37.8%, and the lowest being those with college and above education, at 8.5%. In terms of income, the middle-to-high income group has the largest proportion, at 45.6%, while the proportion of the low-income group is the smallest, at only 4.9%. The middle-to-low income and high-income groups account for 34.8% and 14.7%, respectively, showing the characteristic income distribution in rural areas.

Data from the sample of urban residents show a slightly higher proportion of females, at 56.0%, compared to males, at 44.0%. In terms of educational attainment, junior high school education remains the highest at 41.3%, followed closely by high school or technical school education, at 21.7%. Those with primary school education or below account for 25.1%, while those with college and above education account for 11.9%, reflecting a relative improvement in urban education levels. In terms of income distribution, the middle-to-high income group dominates significantly, at 52.6%, far exceeding the 3.1% of the low-income group. The middle-to-low income and high-income groups account for 25.4% and 19.0%, respectively, highlighting the higher concentration and diversity of income levels among urban residents.

5.2. Analysis of Variance

In the specific socio-cultural context of China, it is worth investigating whether education level and income status have an impact on residents’ environmental behavior. To better understand the relationship between these factors, this study employs an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to examine and verify whether there are significant interactions between education level and income. Specifically, it explores whether education and income—two independent variables—have a synergistic effect on residents’ environmental behavior and whether this effect is statistically significant (see Table 5).

Table 5.

ANOVA of education and income.

The analysis results indicate that the η2 values range from 0 to 1, suggesting that the three factors have some explanatory power. Specifically, the F value for education level is very small (F = 0.014), with p > 0.05, indicating that the main effect of the education level is not significant. The F value for income level is slightly larger (F = 1.116), but the p value is also high (p = 0.209), suggesting that the income level does not have a significant effect on the response variable either. The interaction effect between education level and income level has a small F value (F = 0.869) and a p value greater than 0.05 (p = 0.825), indicating that the interaction effect of education and income on the response variable is not significant.

In summary, neither the education level nor income level significantly affects residents’ environmental behavior. Additionally, there is no significant interaction between education and income. This implies that the impacts of education and income on residents’ environmental behavior are independent, and there is no notable interaction between them. Therefore, when analyzing residents’ environmental behavior, the effects of education and income can be considered separately without accounting for their interaction.

5.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

This study aims to explore the specific effects of urban–rural differences in China on residents’ environmental behaviors and to examine how the education level and income level, two socioeconomic status indicators, influence environmental protection behaviors among urban and rural residents. SPSS 26 statistical software is used for data analysis. Constructing a multiple regression model (Table 5) furthers the precise quantification of the above complex relationships. Considering that the core dependent variable, Chinese residents’ environmental behaviors, manifests as continuous data, this study employs classical ordinary least squares regression analysis to ensure the model’s applicability and interpretative power. In the modeling process, all relevant independent variables and necessary control variables are integrated into the framework of this multiple regression model, aiming to comprehensively analyze the independent contributions of each factor and their interactive effects. The model is rigorously designed to systematically reveal how educational background and economic capability interact with urban–rural contexts, jointly shaping Chinese residents’ patterns of environmental protection behaviors. Its mathematical expression is as follows:

where Y represents the dependent variable, Chinese residents’ environmental behaviors; X represents the variables influencing Chinese residents’ environmental behaviors, with p indicating the number of variables; β is the intercept term; β1, β2, …, βp are the regression coefficients of each explanatory variable, affecting the scores of Chinese residents’ environmental behaviors; and ε represents the residual. The analysis results are shown in Table 6.

Yp = β0 + β1X1 + β2X2 + … + βpXp + ε

Table 6.

Estimates of a multiple regression model of urban and rural residents’ environmental behaviors.

6. Empirical Analysis Results

This study reveals significant differences in the socioeconomic status of Chinese urban and rural residents, particularly the impact of differences in education levels and economic incomes on residents’ environmental behavior patterns. The educational background and economic capability not only serve as core driving factors directly linked to individuals’ environmental protection behaviors but also delineate significant urban–rural divides, further exacerbating the gap in environmental awareness and practices between urban and rural residents.

6.1. Analysis Results of the Full Model

The comparative analysis shows that the R2 and adjusted R2 values of all three models exceed the threshold of 0.8, robustly demonstrating their superior performance in data fitting and their ability to effectively explain the observed dataset. Among these models, the full model exhibits the most outstanding explanatory power due to its highest goodness-of-fit indicators; the urban residents model follows closely, demonstrating strong predictive capabilities; in comparison, the rural residents model, though slightly lagging in explanatory power, still maintains a high level of fit, indicating its good descriptive and explanatory capabilities for the data. Overall, all three models effectively capture the data characteristics, with the full model particularly highlighting its explanatory power.

6.1.1. Impact of Education Level on Urban and Rural Residents’ Environmental Scores

In the analysis of the entire sample, the regression coefficients for gender and age are −0.107 and −0.001, respectively, theoretically indicating a slight negative impact on environmental behavior. Importantly, their corresponding p-values are greater than 0.05, suggesting that at the 0.05 level of statistical significance, the expected negative effects of gender and age on environmental behavior are insignificant. This finding reflects the widespread penetration and acceptance of gender equality concepts in contemporary Chinese society, as well as the gradual reduction in differences in environmental behavior literacy between genders. Meanwhile, age no longer appears to be a key factor determining differences in environmental behavior performance, indicating enhanced consistency across age groups and an increasing consensus on environmental responsibility among the general population.

It is noteworthy that the regression coefficient for the household registration type (with agricultural hukou as the baseline) is −0.230, and its p-value is less than 0.05, clearly indicating a significant negative correlation between non-agricultural hukou and environmental behavior scores at the specified level of significance, strongly supporting Hypothesis 1.1. However, to comprehensively verify Hypothesis 1, which confirms the comprehensive impact of socioeconomic status on environmental behavior, the current analysis still has limitations, especially considering that differences in education levels and income levels have not shown significant effects. Therefore, the next step in the research should be to conduct a thorough t-test of environmental behavior scores between rural and urban residents to more comprehensively explore and validate these hypotheses, particularly the subtle differences in education and income dimensions and their potential impacts on environmental behavior.

According to the results of regression analysis, both education level and income level enhancement are positively associated with environmental behavior scores. The regression coefficients for all these variables are positive, and their respective p-values are less than 0.05, strongly demonstrating the significant positive effects of education level improvement and income level increase on environmental behavior scores at the 0.05 significance level. According to the regression equation of the full model, the environmental behavior score is calculated as follows:

Environmental behavior score = −0.107 (gender) − 0.230 (household registration) − 0.001 (age) + 1.862 (junior high school) + 1.529 (senior high school or technical secondary school) + 1.723 (college or above) + 5.251 (medium-low income) + 8.186 (medium-high income) + 13.306 (high income) + 25.511

In the above equation, it can be seen that among the significant variables at the 0.05 significance level, the coefficient for household registration is −0.230. This implies that with other conditions held constant, an increase of 1 unit in household registration will potentially decrease the environmental behavior score by 0.230 units. Compared to agricultural hukou, non-agricultural hukou scores lower by 0.230 units in environmental behavior, highlighting the significant impact of urban–rural differences on environmental behavior performance. Regarding education level, using primary school and below as a reference, residents with junior high school, senior high school or technical secondary school, and college or higher education levels exhibit significantly higher participation in environmental behavior, confirming Hypothesis 2.1 that an increase in education level has a positive effect on promoting residents’ environmental behavior. This further emphasizes the crucial role of education in fostering environmental awareness and behavior habits.

A detailed analysis of the regression results for education level variables reveals a positive association between education advancement and environmental behavior. Specifically, when individuals’ education level increases from primary school or below to junior high school, their environmental behavior score is expected to increase by 1.862 points, indicating that residents with a junior high school education exhibit more proactive environmental behavior compared to those with primary school or lower education levels. Furthermore, the regression coefficient for senior high school or technical secondary school education is 1.529, indicating that this group scores 1.529 points higher in environmental behavior compared to those with primary school or lower education levels, confirming the positive impact of education on environmental behavior. As for residents with college or higher education levels, their environmental behavior score is expected to increase by 1.723 points, once again corroborating the positive correlation between educational attainment and environmental behavior. Residents with junior high school, senior high school or technical secondary school, and college or higher education levels score 1.862, 1.529, and 1.723 points higher, respectively, in environmental behavior compared to those with primary school or lower education levels. This indicates that higher education levels are associated with a greater likelihood of adopting favorable environmental behaviors, thereby promoting improvements in environmental quality and validating the hypothesis.

6.1.2. Impact of Income on Environmental Scores of Urban and Rural Residents

A detailed analysis from the income perspective clearly demonstrates a significant positive impact of income level on environmental behavior, robustly supporting Hypothesis 3. Specifically, compared to the low-income group, residents with middle–low, middle–high, and high incomes show significant improvements in environmental behavior scores, with regression coefficients of 5.251, 8.186, and 13.306, respectively. This implies that, holding other factors constant, for each increase in income level, residents’ environmental behavior scores increase correspondingly: those with middle–low income increase by 5.251 points compared to the low-income group, those with middle–high income increase by 8.186 points, and those with high income increase by a substantial 13.306 points. This sequential growth trend not only confirms the direct correlation between income enhancement and environmental behavior positivity but also aligns well with the theoretical framework of post-materialistic values and individual resource mobilization capabilities, indicating that with improved economic conditions, individuals are more inclined and capable of taking environmentally beneficial actions. In conclusion, these findings not only validate Hypothesis 3, which suggests that the income level positively promotes environmental behavior, but also further refine to different income levels, confirming Hypothesis 3.1 that as income increases, residents’ willingness and ability to engage in environmental conservation behaviors show an upward trend.

6.2. Sub-Model Analysis Results

In order to comprehensively analyze the differences and similarities in the impact of socioeconomic status on environmental behavior between rural and urban residents, sub-models were constructed to specifically investigate the differences between them. When assessing the differences in environmental behavior between urban and rural residents, using the direct difference method is an intuitive approach, simply subtracting the regression coefficients of urban residents from those of rural residents in terms of environmental behavior scores. To comprehensively measure these differences without considering directionality (i.e., focusing solely on the absolute magnitude of differences), further application of absolute value calculations can be used to quantify this gap. Therefore, a mathematical expression used to describe the differences in environmental behavior impact between urban and rural residents can be standardized as

D = |U − R|

In the above formula, D represents the Difference Score, which is the difference between the urban environment score (U) and the rural environment score (R). This formula represents the absolute difference in environmental behavior scores between urban residents and rural residents. If U > R, the difference value is positive, indicating that urban residents have higher environmental behavior scores than rural residents; if R < U, the difference value is positive, but it indicates that rural residents have higher environmental behavior scores than urban residents (the absolute value eliminates directional negativity, focusing purely on the magnitude of the difference, not the direction). In this way, the formula provides a concise and comprehensive tool for assessing and comparing the relative strength and consistency of the impact of different residential environments on residents’ environmental behavior.

6.2.1. Education Level and Differences in Environmental Behavior between Urban and Rural Residents

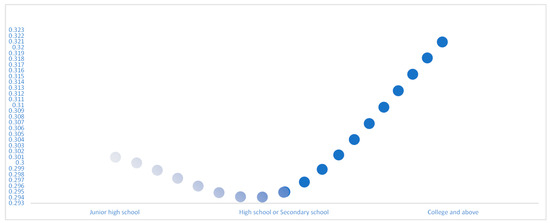

The analysis of educational attainment reveals differences in environmental behavior between rural and urban residents. Among rural residents, individuals with junior high school, senior high school or technical secondary school, and college or higher education show respective increases of 1.892, 1.554, and 1.878 points in environmental behavior scores compared to those with elementary school education or below. In urban areas, these same educational levels correspond to score increases of 1.884, 1.583, and 1.555 points. Applying the aforementioned difference calculation formula, we obtain the following:

Junior high school: D1 = |U1 − R1| = 0.301 = |1.884 − 1.892|

High school or junior college: D2 = |U2 − R2| = 0.295 = |1.583 − 1.554|

College and above: D3 = |U3 − R3| = 0.323 = |1.555 − 1.878|

According to the calculations above, the urban–rural differences in junior high school education (D1) amount to 0.301, indicating urban residents score slightly lower by 0.301 points. For senior high school or technical secondary school education (D2), the urban–rural difference is 0.295 points, with urban residents scoring slightly higher than rural residents. The urban–rural difference widens to 0.323 points for college or higher education (D3), where urban residents score significantly lower than rural residents.

These data demonstrate that with increasing levels of education, the urban–rural disparity in environmental behavior scores has undergone a dynamic shift of initially narrowing and then widening (see Figure 4). Particularly notable is that urban residents score lower than rural residents at the junior high school and college or higher education levels, which diverges from traditional understanding. Conversely, at the senior high school or technical secondary school level, urban residents show a slight advantage. This finding challenges Hypothesis 2.3, suggesting that under similar educational backgrounds, rural residents’ environmental behavior scores may not necessarily be lower than those of urban residents. This study reveals significant improvements in rural education levels, particularly against the backdrop of China’s implementation of compulsory nine-year education and policies favoring rural areas. After reaching a certain level of education, rural residents’ environmental behavior scores even surpass those of urban residents, especially at the college or higher education levels, highlighting possibly enhanced rural education quality, expanded information access channels, and increased environmental awareness.

Figure 4.

Differential values of environmental behavior scores of urban and rural residents at the same educational level.

This study’s uniqueness lies in its revelation of the complexity and non-linear characteristics of urban–rural differences in environmental behavior under equal educational conditions, challenging the simplistic urban–rural dichotomy of the past. This not only provides a new perspective on the relationship between education and environmental behavior but also offers important empirical evidence for formulating more precise and effective environmental policies to promote balanced urban–rural development.

6.2.2. Income Levels and Differences in Environmental Behavior between Urban and Rural Residents

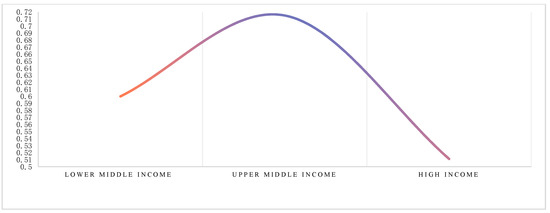

The analysis of the impact of income levels on urban–rural residents’ environmental behavior reveals that among rural residents, the environmental behavior scores increased by 5.118, 8.002, and 13.179 points for the middle–low, middle–high, and high-income groups compared to the low-income group. Similarly, urban residents in these income brackets saw additional scores of 5.781, 8.717, and 13.690, respectively. Based on these data, we calculated the differences in environmental behavior scores between urban and rural residents across income levels:

Middle–low income: D4 = |U4 − R4| = 0.60 = |5.781 − 5.118|

Middle–high income: D5 = |U5 − R5| = 0.715 = |8.717 − 8.002|

High income: D6 = |U6 − R6| = 0.511 = |13.690 − 13.179|

In these calculations, the difference value for the middle–low income group (D4) is 0.60, indicating that urban residents in this income bracket score 0.60 points higher in environmental behavior than rural residents. The difference value for the middle–high income group (D5) is 0.715 points, showing a similar advantage for urban residents. In the high-income group, the difference (D6) decreases to 0.511 points, suggesting a narrowing of the urban–rural gap compared to previous income levels.

These series of computations demonstrate that as income levels rise, the disparity in environmental behavior scores between urban and rural areas initially increases and then decreases (see Figure 5), thus validating the trend proposed by Hypothesis 3.2. Importantly, all difference values across income levels are positive and generally above 0.5 points, clearly indicating that within the same income bracket, urban residents exhibit a stronger inclination toward participating in environmental behavior compared to rural residents, robustly supporting Hypothesis 3.3. This suggests that even with comparable income levels, urban residents demonstrate more significant enthusiasm and participation in environmental behavior, possibly due to greater access to environmental information and resources for participating in environmental activities.

Figure 5.

Differential values of environmental behavior scores of urban and rural residents at the same income level.

6.3. T-Test: Analysis of Differences

Through in-depth analysis using a multiple regression model, this study uncovered a key finding: the household registration type emerged as a significant variable. At a statistical significance level of 0.05, its regression coefficient was −0.230, indicating a negative correlation between household status change and environmental behavior scores. This means that, holding other factors constant, non-agricultural household holders score an average of 0.230 points lower in environmental behavior compared to agricultural household holders. While this result highlights the statistical significance of household type, relying solely on regression analysis is insufficient to comprehensively verify the initial hypothesis regarding household’s impact on environmental behavior. Therefore, the researchers conducted a t-test to precisely assess the differences between household categories. The t-test was chosen for its flexibility and applicability, making it particularly suitable for scenarios with small sample sizes, which aligns well with the needs of this study. Additionally, the t-test is effective in comparing the mean differences between urban and rural residents, allowing us to determine if there is a statistically significant difference between the two groups. This provides strong support for the research findings.

The results of the t-test (shown in Table 7) clearly demonstrate that rural residents have a mean environmental behavior score of 34.032 ± 4.033, while urban residents have a mean of 34.673 ± 3.857. The associated t-value is −2.449, with a p-value of 0.014, significantly less than 0.05, strongly indicating a significant effect of household differences on environmental behavior scores. Furthermore, urban residents score significantly higher than rural residents, robustly validating hypothesis 1.1.

Table 7.

T-test of environmental behavior differences between rural and urban residents.

Regarding gender as a variable, this study found that the mean environmental behavior score for males is 34.406 ± 9.925, and that for females is 34.061 ± 4.043. However, the t-test yielded a p-value of 0.151, exceeding the significance threshold of 0.05, indicating that gender does not significantly influence environmental behavior scores at the current level of analysis, thereby refuting the hypothesis that gender causes differences in environmental behavior. In summary, household type has been confirmed as a significant differentiating factor affecting residents’ environmental behavior performance, while gender differences in this regard appear relatively minor.

7. Discussion and Recommendations

7.1. Discussion

This study aims to deeply explore and elucidate the intricate and profound connections between socioeconomic status and environmental conservation behaviors among urban and rural residents based on the authoritative 2021 CGSS dataset. The analysis reveals that inherent differences in socioeconomic status among Chinese residents constitute a core element influencing their patterns of environmental behavior, particularly within the social structure framework divided between urban and rural areas.

Firstly, there are notable differences in environmental protection behaviors between urban and rural residents, with urban residents demonstrating more active participation. This can be attributed to their higher economic income and greater access to social resources. In contrast, rural residents, constrained by economic conditions, tend to focus more on meeting basic life needs. However, the spread of education helps enhance environmental awareness and participation among rural residents, thereby narrowing this gap. As education becomes more widespread and the awareness of equity grows, environmental protection is gradually becoming a universal action that transcends regional and economic differences.

Secondly, income levels are a key factor influencing the environmental behavior of both urban and rural residents. Across all income levels, there is a trend of increasing environmental behavior, but higher-income individuals are more actively involved in activities such as investing in green consumption and environmental projects. Lower-income individuals contribute to environmental protection through small actions, like reducing plastic use. Urban residents generally show greater concern for the environment compared to rural residents, largely due to the pressing environmental issues in cities and the abundance of informational resources. Therefore, when promoting environmental initiatives, it is essential to consider both economic capacity and regional characteristics.

Moreover, education has a positive impact on the environmental behavior of both urban and rural residents. This is particularly evident in rural areas, where significant improvements in educational attainment have led to enhanced environmental awareness and behavior. The equitable distribution of educational resources helps narrow the urban–rural gap. However, the influence of education is not uniform. At certain educational levels, urban residents perform better. Challenges faced by rural areas, such as economic constraints and changes in family structure, impact students’ education and environmental behavior. Issues like the problem of left-behind children and insufficient educational resources in rural areas exacerbate these differences. Therefore, optimizing the allocation of educational resources, with a focus on rural education and social issues, is crucial for narrowing the urban–rural gap in environmental behavior and improving national environmental awareness.

Finally, education has a positive impact on improving environmental behavior among urban and rural residents. Higher education levels undoubtedly contribute to a progressive improvement in environmental behavior across these populations. Of particular note is the significant progress in education in rural areas, driven by China’s strong support for rural education and the widespread implementation of nine-year compulsory education. The substantial improvement in educational attainment among rural residents has directly enhanced their environmental awareness and behavior. At certain educational levels, such as middle school and higher education, rural residents even score higher in environmental behavior than urban residents, clearly demonstrating the positive role of equitable distribution of educational resources in narrowing the urban–rural gap in environmental behavior. However, the influence of education is not uniformly linear. At the high school or vocational education level, urban residents still exhibit superior environmental behavior. This disparity reflects the unique challenges faced by rural areas, such as economic constraints, household responsibilities, and changes in family structure due to the outflow of rural labor. These factors may impact rural students’ continued education and overall development, subsequently influencing their environmental behavior. Issues such as the plight of left-behind children and the relative scarcity of educational resources in rural areas further exacerbate this gap. In summary, education plays a significant role in enhancing environmental behavior among urban and rural residents, but its impact is complex, intertwined with factors such as urban–rural development disparities, the allocation of educational resources, and changes in family structure. While the improvement in environmental behavior driven by education is evident, particularly in rural areas, it also exposes limiting factors specific to rural socioeconomic conditions. Therefore, optimizing the allocation of educational resources, with particular attention to the depth and breadth of rural education and addressing the unique social challenges of rural areas, is crucial for narrowing the urban–rural gap in environmental behavior and enhancing national environmental awareness and action across the board.

Moreover, this study uncovered additional findings that challenge traditional views on gender and age factors. Historical data indicated slightly higher environmental awareness among males, closely linked to historical limitations in female social status and access to educational resources [3]. Previously, increasing age was associated with a decline in environmental awareness, reflecting the evolution of generational perspectives and the generational gap in receiving environmental information. However, the 2021 CGSS data reveal that the influence of gender and age on residents’ environmental behavior is no longer significant. Behind this shift lies the widespread promotion and deepening of gender equality ideals in China, along with efforts toward the equitable distribution of educational resources. Although traditional notions of male superiority and female subordination have not been completely eradicated in some rural areas, overall, the increasing prevalence of education, particularly the substantial rise in female education levels, has blurred the gender differences in environmental behavior. Similarly, China’s longstanding emphasis on education, including the restoration of the college entrance examination system in 1997, the large-scale literacy campaigns of 1953, and the implementation of compulsory education laws in 1986, has universally elevated the level of education among its populace, diminishing age as a key variable restricting environmental conservation behaviors. In summary, China’s sustained efforts in promoting gender equality and education have effectively weakened the traditional boundaries of gender and age in influencing environmental behavior, marking a new chapter in societal progress and widespread environmental awareness.

7.2. Recommendations