Integrating Sustainability and Circular Economy into Consumer-Brand Dynamics: A Saudi Arabia Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Question

1.2. Research Objectives

- Objective 1: Assess Consumer Perceptions of Brand Personality

- Objective 2: Examine the Impact of Self-Congruence on Consumer Choices

- Objective 3: Investigate the Relationship between Brand Loyalty and Sustainability

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Foundation of Brand Personality

Functional and Symbolic Aspects

2.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Brand Loyalty

2.3. Self-Congruence Theory in Marketing

Self-Congruence and Brand Loyalty

2.4. Sustainability and CE

2.4.1. Global Sustainability Trends

2.4.2. Sustainability in Consumer Markets

2.4.3. Principles of CE

2.4.4. CE in Developing Economies

2.4.5. CE and Consumer Engagement

2.5. Consumerism in Saudi Arabia

2.5.1. The Intersection of Luxury and Sustainability

2.5.2. Emergent Consumer Trends and Economic Crises

2.5.3. Consumerism and Societal Transformation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Framework

3.2. Population, Sample, and Sampling Technique

3.3. Survey Instrument and Data Collection

3.4. Hypothesis

3.5. Data Analysis

3.5.1. Non-Parametric Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.5.2. Non-Parametric Tests for Group Comparisons

3.5.3. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)

4. Results

4.1. The Demographic Distribution of the Participants

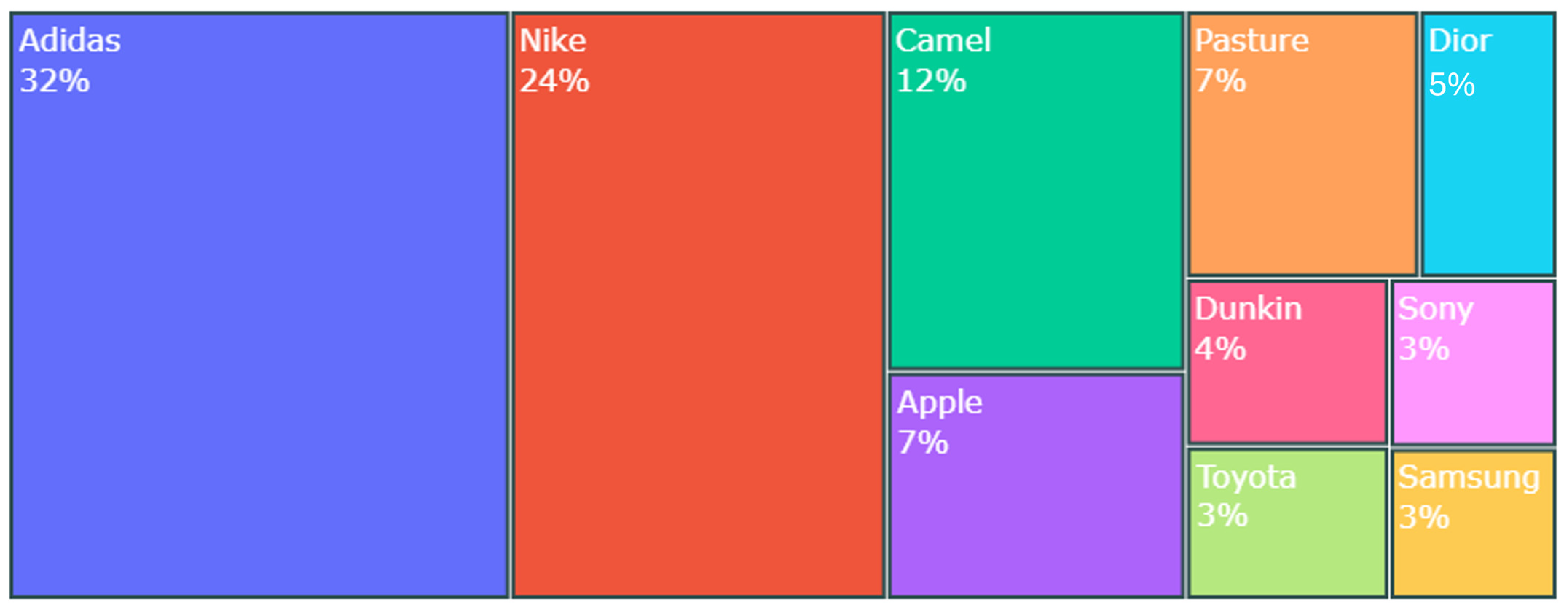

4.2. Brand Personality

- Gender Analysis: The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare ABPS scores between males and females. The test revealed no significant difference in ABPS between genders (U = 37,276.0, p = 0.7629), indicating that gender does not significantly influence perceptions of brand personality [56].

- Age Groups: Differences in ABPS across age groups were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis H test. The results showed significant variations in ABPS across different age groups (H = 41.05, p < 0.0001), with the 36–45 age group exhibiting the highest median ABPS and the 76+ age group the lowest [55]. This suggests that age plays a significant role in shaping brand personality perceptions.

- Qualification Levels: The Kruskal–Wallis H test was also applied to compare ABPS across different qualification levels. The analysis revealed significant differences (H = 25.88, p = 0.00023), indicating that educational background influences how participants perceive brand personality.

- Correlation with Age: The relationship between ABPS and age was further explored using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The analysis found a significant negative correlation (rho = −0.173, p = 0.0000132), suggesting that as age increases, alignment with brand personality tends to decrease [59].

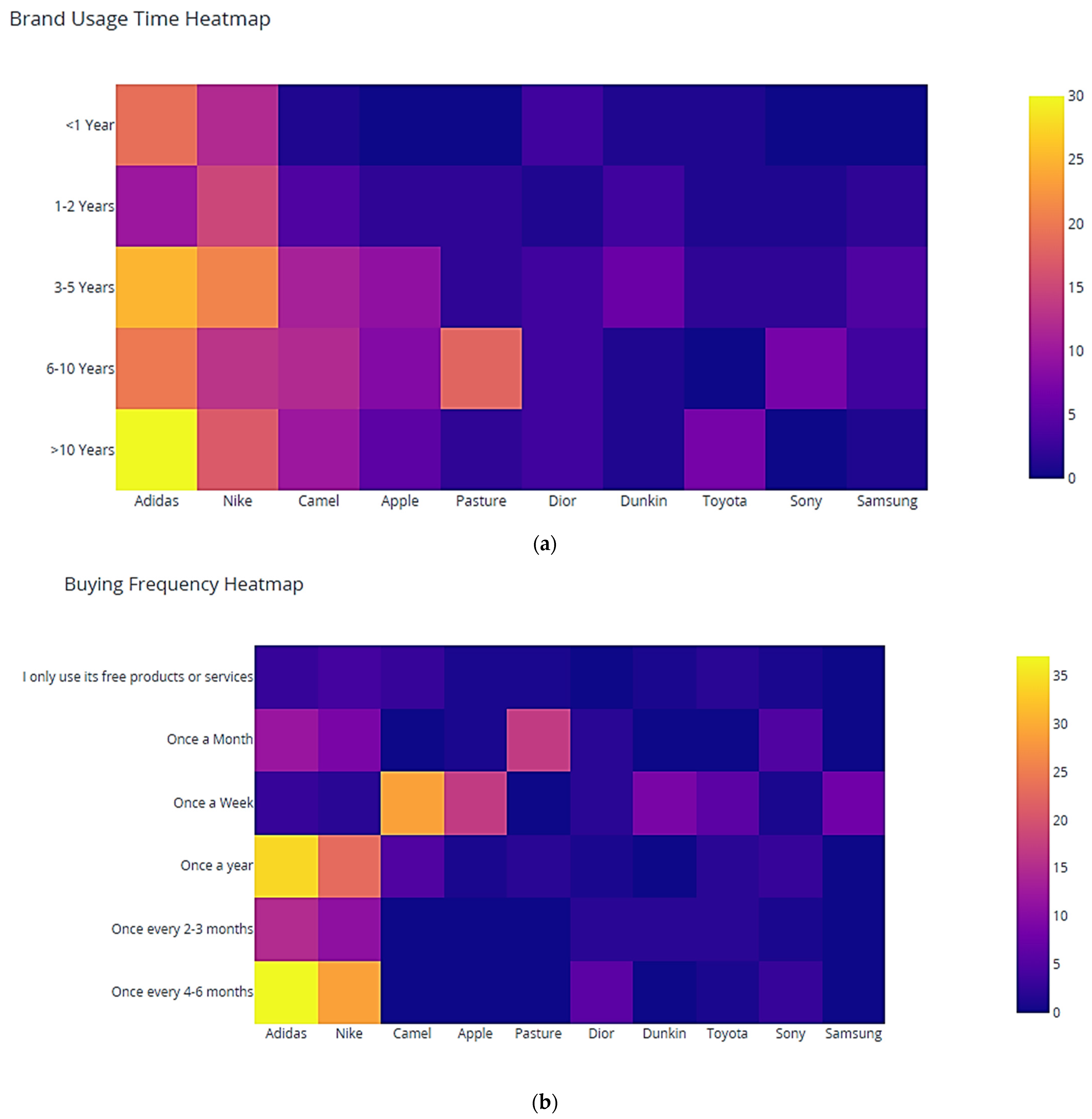

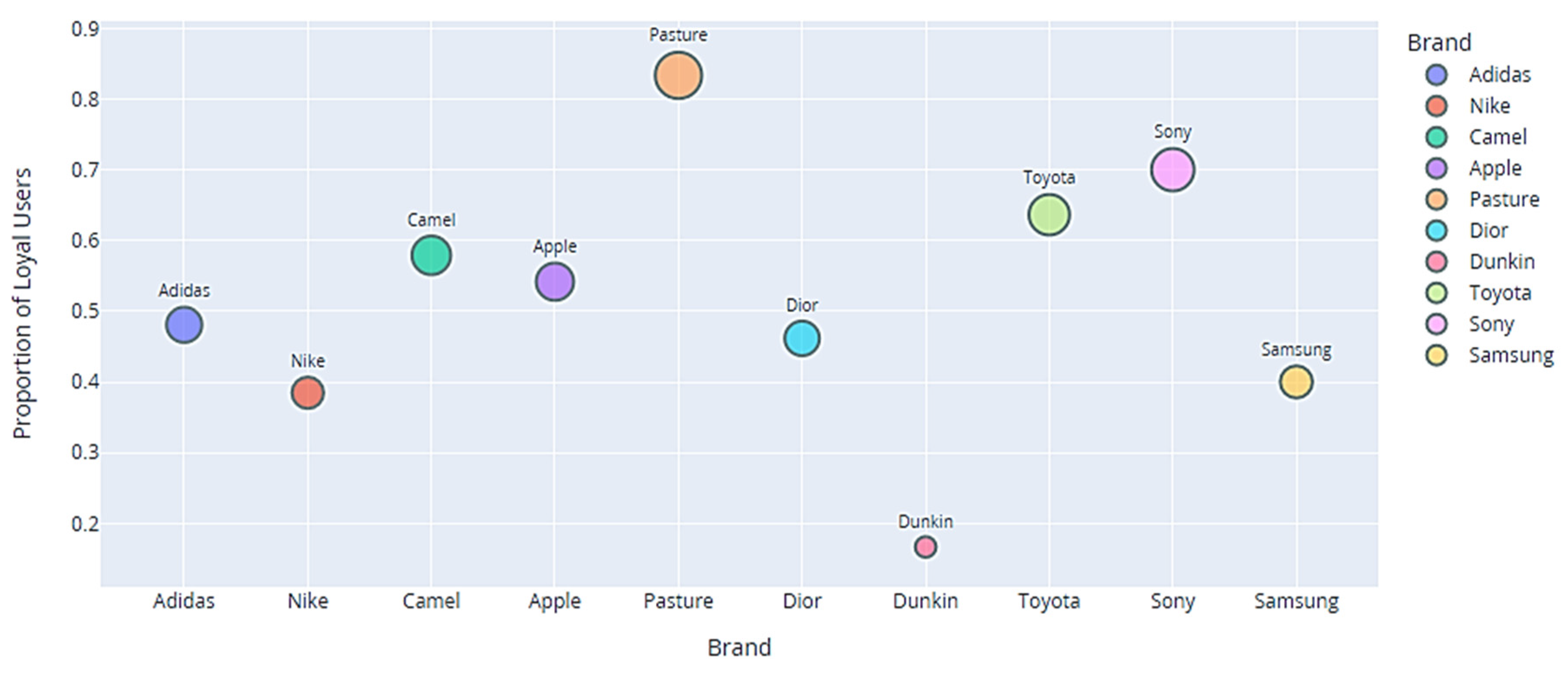

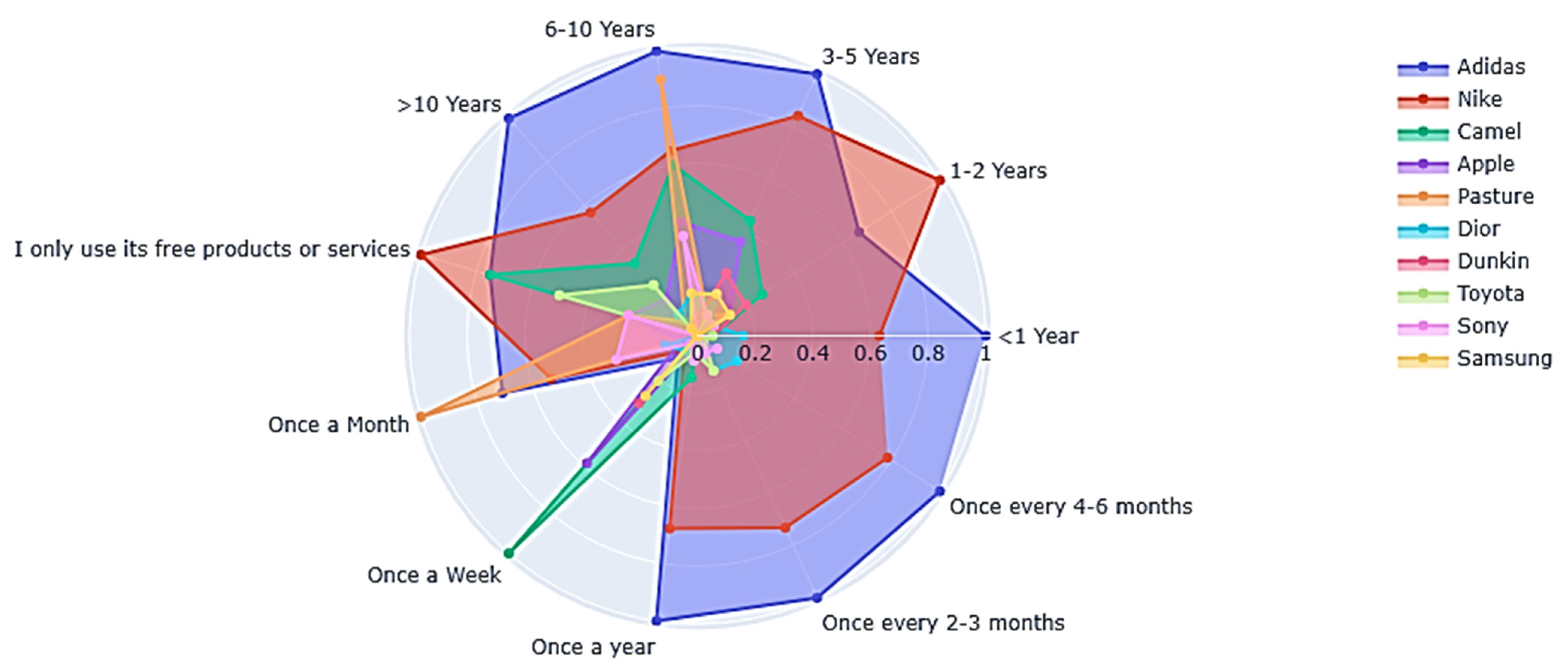

4.3. Brand Loyalty

4.3.1. Factors Influencing Brand Loyalty

4.3.2. Brand Engagement

4.3.3. Comparative Brand Engagement

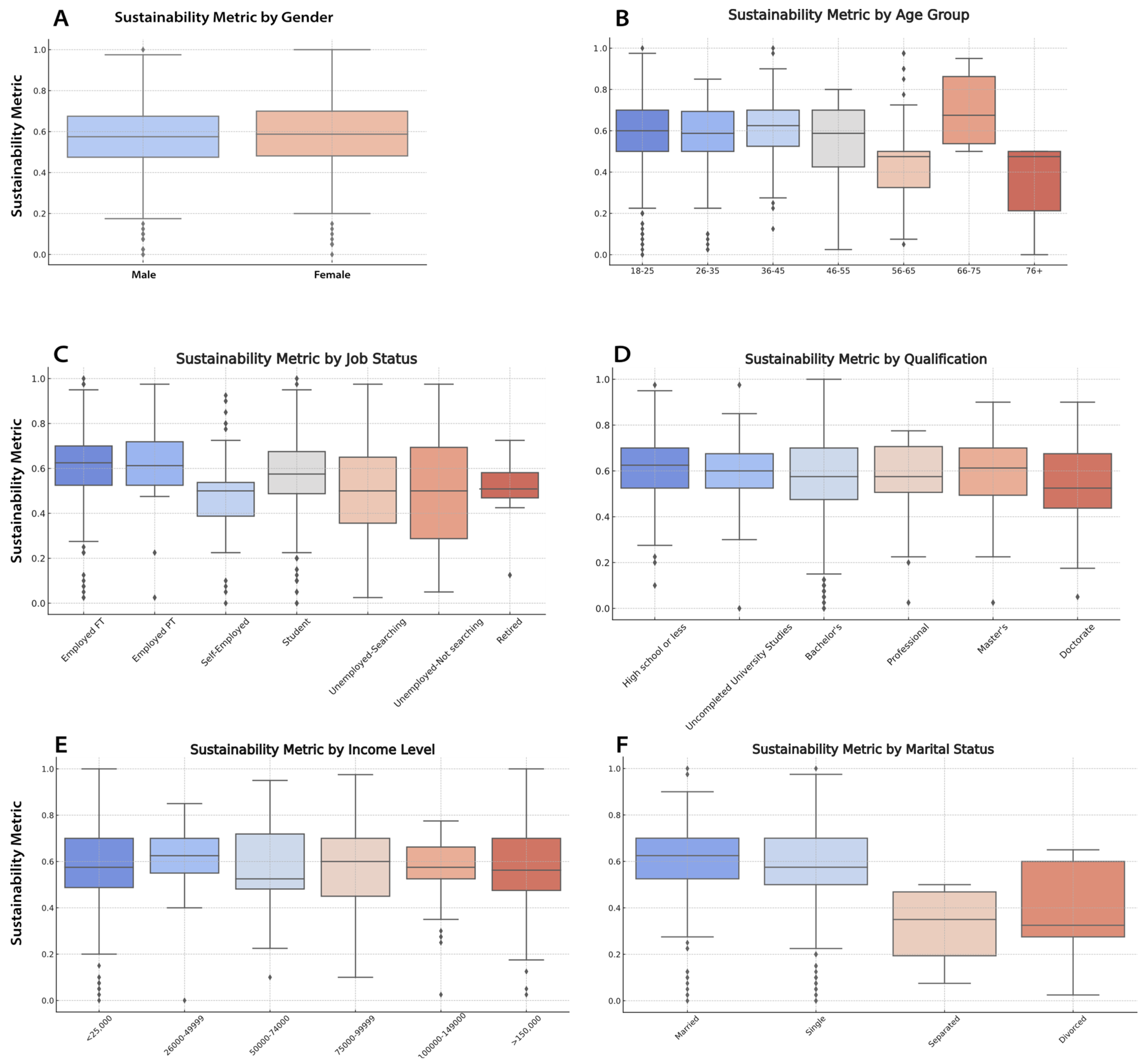

4.4. Consumer Sustainability Orientation

4.4.1. Sustainability Metric

- X is an individual’s response on the Likert scale.

- min(X) represents the minimum value of the Likert scale responses in the dataset, which is 1 in this context.

- max(X) denotes the maximum value of the Likert scale responses, which is 5 for this dataset.

4.4.2. Demographic Influence on Sustainability Metrics

4.5. Brand Personality and Sustainability Purchase Decisions

4.6. Brand Loyalty and Sustainability Purchase Decisions

4.7. Influence of Circular Practices on Brand Loyalty

4.8. The Impact of Demographics on Sustainable Purchasing

4.8.1. Impact of Gender on Sustainable Purchase Components

4.8.2. Impact of Age on Sustainable Purchase Components

4.8.3. Impact of Qualification on Sustainable Purchase Components

4.8.4. Impact of Job Status on Sustainable Purchase Components

4.8.5. Impact of Income Level on Sustainable Purchase Components

4.8.6. Impact of Marital Status on Sustainable Purchase Components

4.9. Impact of Preferred Brand on Sustainable Purchase Behavior

5. Discussion

5.1. Brand Personality and Sustainable Choices

5.2. Brand Loyalty’s Influence on Sustainable Consumption in Saudi Arabia

5.3. CE’s Role in Enhancing Brand Loyalty

5.4. Demographic Determinants of Sustainable Consumer Behavior

5.5. Theoretical Alignment

5.6. Implications of Research

6. Conclusions

Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

- Male

- Female

- Prefer not to answer

- 18–25

- 26–35

- 36–45

- 46–55

- 56–65

- 66–75

- 76+

- High school or less

- Vocational certificate

- Some college, did not complete degree

- Bachelor’s degree

- Master’s degree

- Doctorate

- Prefer not to answer

- Unemployed, looking for work

- Unemployed, not looking for work

- Self-employed

- Part-time employed

- Full-time employed

- Retired

- Student

- Saudi

- Other

- Single

- Married

- Divorced

- Separated

- Prefer not to answer

- Less than 25,000

- 26,000–49,999

- 50,000–74,999

- 75,000–99,999

- 100,000–149,000

- More than 150,000

- Prefer not to answer

- Less than a year

- 1–2 years

- 3–5 years

- 6–10 years

- More than 10 years

- Only use free products/services

- Once a year

- Every 4–6 months

- Every 2–3 months

- Once a month

- Once a week

- Several times a week

- Product or service quality

- Price

- Brand reputation

- Brand’s sustainability efforts

- Customer service

- Social responsibility initiatives

- Other

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- I feel that my favorite brand aligns with my personality.

- I see my favorite brand as a reflection of the person I aspire to be.

- I think my favorite brand represents the type of person I want to become.

- Reducing usage

- Reusing products

- Repairing products

- Refurbishing products

- Remanufacturing

- Recycling

- Upcycling

- Repurposing

- Other

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- I support the concept of the circular economy or resource recycling.

- I am familiar with the circular economy concept and its practices in Saudi Arabia.

- When considering purchasing a product from my favorite brand, I am concerned about the durability and lifespan of the product.

- I support purchasing used products in Saudi Arabia.

- I prefer to contribute with friends in buying products and services together rather than buying them alone.

- I am willing to pay more for a product if I know it is environmentally friendly and sustainable.

- I often discard products that still work or contain useful parts.

- I am very interested in the Saudi government setting policies and regulations to encourage the circular economy or recycling.

- I prefer to buy expensive branded products and replace them when they break or wear out, rather than buying products I can keep, repair, and reuse.

References

- UNEP. Global Material Flows and Resource Productivity Assessment Report for the UNEP International Resource Panel; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019; ISBN 9789280735543. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Living Planet Report 2020: Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuian, S.N.; Abdul-Muhmin, A.G. Consumerism in the Arab Middle East: The Case of Saudi Arabia. In Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Toffaha, N.; Al-Dabbagh, M.A. Purchase Intentions and Luxury Brands: A Study on Consumer Behaviour in Saudi Arabia. J. Econ. Adm. Leg. Sci. 2023, 7, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A. Effect of Economic Crisis on Saudi Arabian Consumers’ Behavior towards Luxury Goods. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. Manag. 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalkhail, T.S. The Impact of Religiosity on Luxury Brand Consumption: The Case of Saudi Consumers. J. Islam. Mark. 2020, 12, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatni, B.; Sibley, M.; Minuchin, L. Evaluating the Impact of the Internationalisation of Urban Planning on Saudi Arabian Cities. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 155, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, S.W. The Rise of Consumerism in Saudi Arabian Society. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2008, 17, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.N. New Emerging Buying Trends in KSA Customers. In Proceedings of the 40th International Business Research Conference, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 9–10 January 2017; ISBN 978-1-925488-27-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rohanaraj, T.T.A. The Purchase Behaviour towards Consumer Goods during Economic Crisis—A Middle Eastern Perspective. Econ. Innov. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 11, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Sarkis, J.; Filho, M.G. Unlocking the Circular Economy through New Business Models Based on Large-Scale Data: An Integrative Framework and Research Agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudo, F.L.; Júnior, J.A.G.; de Oliveira Gobbo, S.C. Industry 4.0 and the Circular Economy: Are These Integrated or disjointed concepts? A research agenda. Rev. Gestão Produção Operações Sist. 2020, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Godinho Filho, M.; Roubaud, D. Industry 4.0 and the Circular Economy: A Proposed Research Agenda and Original Roadmap for Sustainable Operations. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 270, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echezona, O. Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives and Brand Loyalty in Emerging Markets. Int. J. Bus. Strateg. 2024, 10, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Awan, R.A.; Ali, R.; Sarmad, I. The Antecedent Cognitions of Brand Love and Its Impact on Brand Loyalty: The Moderating Role of Sustainability Marketing. Corp. Gov. 2023, 24, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajlan, A.M.; Abed, A.M. Al Transformation Model towards Sustainable Smart Cities: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia as a Case Study. Curr. Urban Stud. 2023, 11, 142–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, T. Sustainable Urbanisation in Desert Cities: Case Study Riyadh City. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Government. Saudi Vision 2030; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD (2024), Material Productivity; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of Brand Personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Ruediger, K.H.; Demetris, V. Brand Emotional Connection and Loyalty. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 20, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, J.F.; Carvalho, S.W.; Trifts, V. The Role of Brand Personality in the Formation of Consumer Affect and Self-Brand Connection. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamitov, M.; Wang, X.; Thomson, M. How Well Do Consumer-Brand Relationships Drive Customer Brand Loyalty? Generalizations from a Meta-Analysis of Brand Relationship Elasticities. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A.; Molinillo, S. Responsible and Active Brand Personality: On the Relationships with Brand Experience and Key Relationship Constructs. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Ahmed, M.A. Consumer Brand Identification and Purchase Intentions: The Mediating Role of Customer Brand Engagement. J. Entrep. Bus. Ventur. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell-Bennett, R.; Parkinson, J. Loyalty (Brand Loyalty). Wiley Encycl. Manag. 2015, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidaković, P.; Koklič, M.K.; Zečević, M.; Žabkar, V. The Influence of Brand Sustainability on Purchase Intentions: The Mediating Role of Brand Impressions and Brand Attitudes. J. Brand Manag. 2022, 29, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.; Jiang, Y.; Alam, F.; Nawaz, M.Z. Role of Brand Love and Consumers’ Demographics in Building Consumer–Brand Relationship. Sage Open 2020, 10, 215824402098300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T.H. The Impact of Brand Love on Brand Loyalty: The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem, and Social Influences. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2020, 25, 156–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapena-Baron, M.; Gruen, T.W.; Guo, L. Heart, Head, and Hand: A Tripartite Conceptualization, Operationalization, and Examination of Brand Loyalty. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A.; Ekinci, Y.; Simkin, L. Self-Congruence, Brand Attachment and Compulsive Buying. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Teng, L.; Foti, L.; Yuan, Y. Using Self-Congruence Theory to Explain the Interaction Effects of Brand Type and Celebrity Type on Consumer Attitude Formation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kressmann, F.; Sirgy, M.J.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F.; Huber, S.; Lee, D.-J. Direct and Indirect Effects of Self-Image Congruence on Brand Loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. The 17 Goals|Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Gallenti, G.; Troiano, S.; Marangon, F.; Bogoni, P.; Campisi, B.; Cosmina, M. Environmentally Sustainable versus Aesthetic Values Motivating Millennials’ Preferences for Wine Purchasing: Evidence from an Experimental Analysis in Italy. Agric. Food Econ. 2019, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, A.; Ferguson, D.; Beise-Zee, R. How to Go Green: Unraveling Green Preferences of Consumers. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2015, 7, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. In Managing Sustainable Business; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Chabowski, B.R.; Mena, J.A.; Gonzalez-Padron, T.L. The Structure of Sustainability Research in Marketing, 1958–2008: A Basis for Future Research Opportunities. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, J.; Jacob, J. Green Marketing: A Study of Consumers’ Attitude towards Environment Friendly Products. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMF. Universal Circular Economy Policy Goals: Enabling the Transition to Scale; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Isle of Wight, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Ormazabal, M. Towards a Consensus on the Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraccascia, L.; Giannoccaro, I.; Agarwal, A.; Hansen, E.G. Business Models for the Circular Economy: Opportunities and Challenges; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 28, ISBN 9789264307452. [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg, E.; Hinfelaar, J.; Bocken, N. Master Circular Business with the Value Hill; Circle Economy: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rexfelt, O.; Hiort af Ornäs, V. Consumer Acceptance of Product-service Systems. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2009, 20, 674–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Otero, J.; Pettersen, I.N.; Boks, C. Consumer Engagement in the Circular Economy: Exploring Clothes Swapping in Emerging Economies from a Social Practice Perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutaula, S.; Gillani, A.; Leonidou, L.C.; Christodoulides, P. Integrating Fair Trade with Circular Economy: Personality Traits, Consumer Engagement, and Ethically-Minded Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.N. Consumer Behavior and Retail Market Consumerism in KSA. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2012, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.N. A Study on Saudi Arabian Retail Dynamics, Its Potential Future and Challenges. J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2014, 2, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai, K. Exploring the Role of Brand–Sustainability–Self-Congruence on Consumers’ Evaluation of Luxury Brands. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 1951–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algumzi, A. Factors Influencing Saudi Young Female Consumers’ Luxury Fashion in Saudi Arabia: Predeterminants of Culture and Lifestyles in Neom City. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilin, A.; Raiko, T. Practical Approaches to Principal Component Analysis in the Presence of Missing Values. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2010, 11, 1957–2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a Test of Whether One of Two Random Variables Is Stochastically Larger than the Other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The Proof and Measurement of Association between Two Things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test | Variable | Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kruskal–Wallis H Test | Age Groups | 41.05 | <0.0001 |

| Kruskal–Wallis H Test | Qualification Levels | 25.88 | 0.00023 |

| Mann–Whitney U Test | Gender | 37,276.0 | 0.7629 |

| Spearman’s Rank Correlation | Age | −0.173 | 0.0000132 |

| Survey Question | Weighted Mean Percentage | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| I will consider switching for more sustainable brand | 0.55 | 1.0966 |

| I support the CE Concept in Saudi Arabia | 0.67 | 1.2204 |

| I have good CE knowledge in Saudi Arabia | 0.54 | 1.1435 |

| I care about the product’s durability and lifespan when purchasing | 0.69 | 1.2423 |

| I favor purchasing used products in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | 0.52 | 1.1628 |

| I prefer buying products and services with friends rather than alone | 0.53 | 1.1693 |

| I will pay more for an eco-friendly product | 0.52 | 1.1855 |

| I often discard a still-functional product | 0.39 | 1.2592 |

| I strongly support the Saudi government in implementing CE and recycling policies | 0.66 | 1.1853 |

| I choose repairable, high-cost brands over disposable ones | 0.47 | 1.2156 |

| Circular Practice | Coefficient (β) |

|---|---|

| Downcycling | 0.0047 |

| Product Refurbishment | 0.0580 |

| Product Repair | 0.0163 |

| Recycling | −0.0214 |

| Reduce use | −0.0021 |

| Re-manufacturing | 0.0121 |

| Reuse | 0.0199 |

| Upcycling | −0.0051 |

| Hypothesis | Description | Result | Supporting Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| H0-1 | Brand personality traits have no significant impact on sustainable purchase decisions among Saudi consumers. | Rejected | PLS-SEM showed that brand personality explains 16.8% of the variance in sustainable purchasing decisions, indicating a significant influence. |

| H1-1 | Brand personality traits significantly influence sustainable purchase decisions. | Accepted | The positive relationship between brand personality and sustainable purchasing was statistically significant (p-value < 0.001). |

| H0-2 | Brand loyalty components do not significantly influence sustainable purchase decisions among Saudi consumers. | Rejected | PLS-SEM analysis revealed a significant coefficient (0.1661, p = 0.007) between brand loyalty and sustainable purchasing, although with a low R-squared value of 1.17%. |

| H1-2 | Brand loyalty components significantly affect sustainable purchase decisions. | Accepted | The model’s results confirmed the influence of brand loyalty on sustainable purchasing behaviors, despite the modest R-squared value. |

| H0-3 | CE practices have no significant impact on brand loyalty among Saudi consumers. | Partially Rejected | The analysis showed that while CE practices do influence brand loyalty, the overall impact is minimal (R-squared = 0.0051), with specific practices like product refurbishment showing some positive impact. |

| H1-3 | Specific CE practices significantly impact brand loyalty. | Partially Accepted | Although the overall effect of CE practices on brand loyalty is low, some practices like product refurbishment demonstrated a positive association, indicating selective influence. |

| H0-4 | Demographic variables (such as age, gender, and income level) do not significantly affect sustainable purchase decisions among Saudi consumers. | Rejected | The PLS-SEM analysis revealed significant impacts of demographic variables like age and gender on sustainable purchasing decisions, particularly highlighting generational differences. |

| H1-4 | Demographic variables significantly influence sustainable purchase decisions. | Accepted | Age, gender, and income level were found to influence sustainable purchasing decisions, with younger consumers and higher-income groups more likely to engage in sustainable behaviors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abu-Bakar, H.; Almutairi, T. Integrating Sustainability and Circular Economy into Consumer-Brand Dynamics: A Saudi Arabia Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187890

Abu-Bakar H, Almutairi T. Integrating Sustainability and Circular Economy into Consumer-Brand Dynamics: A Saudi Arabia Perspective. Sustainability. 2024; 16(18):7890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187890

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbu-Bakar, Halidu, and Tariq Almutairi. 2024. "Integrating Sustainability and Circular Economy into Consumer-Brand Dynamics: A Saudi Arabia Perspective" Sustainability 16, no. 18: 7890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187890

APA StyleAbu-Bakar, H., & Almutairi, T. (2024). Integrating Sustainability and Circular Economy into Consumer-Brand Dynamics: A Saudi Arabia Perspective. Sustainability, 16(18), 7890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187890