Natural Resource Dependence and Household Adaptive Capacity: Understanding the Linkages in the Context of Disaster Resettlement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data Sources and Research

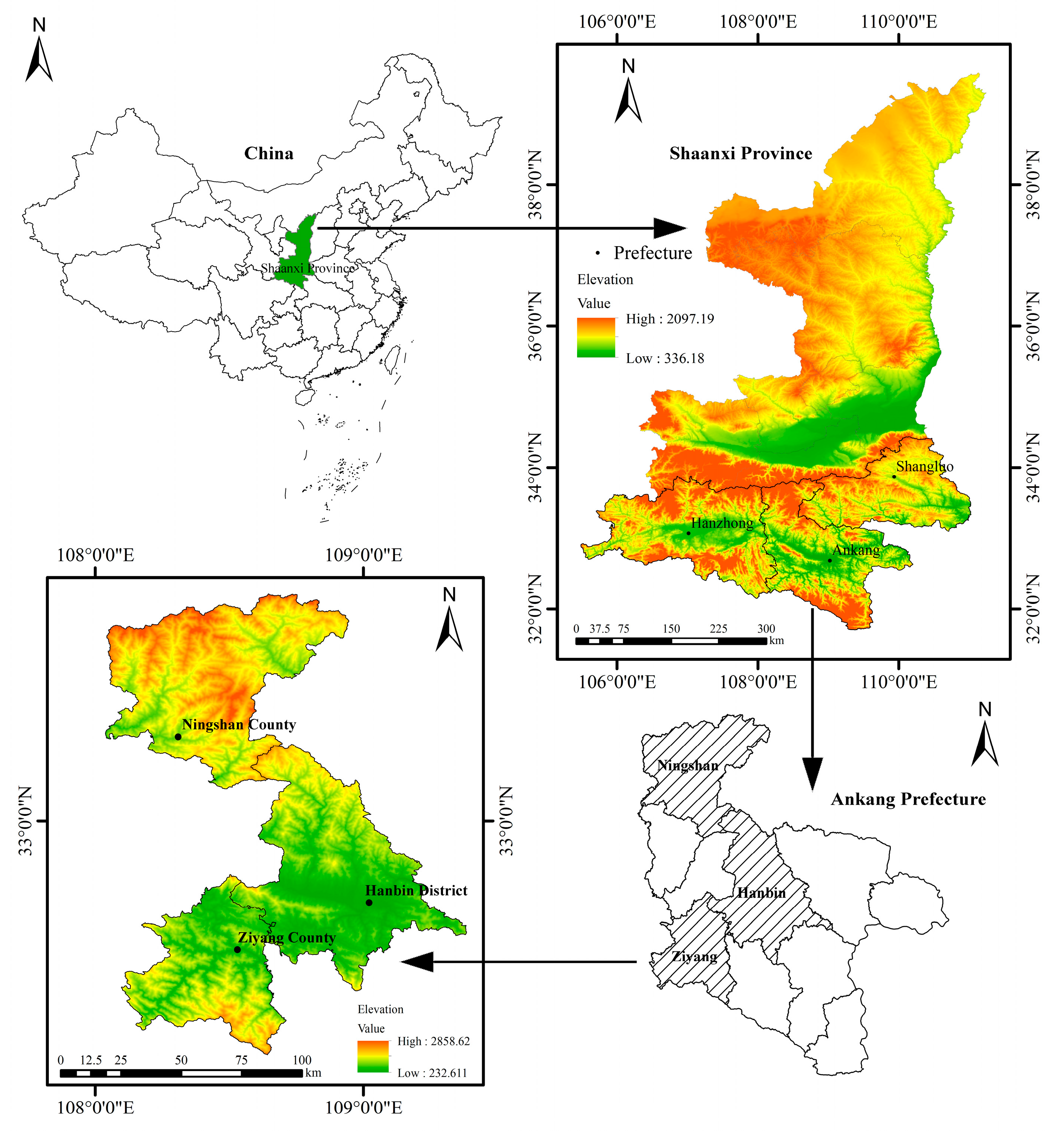

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Indicator Construction

2.3.1. Household Adaptive Capacity (HAC)

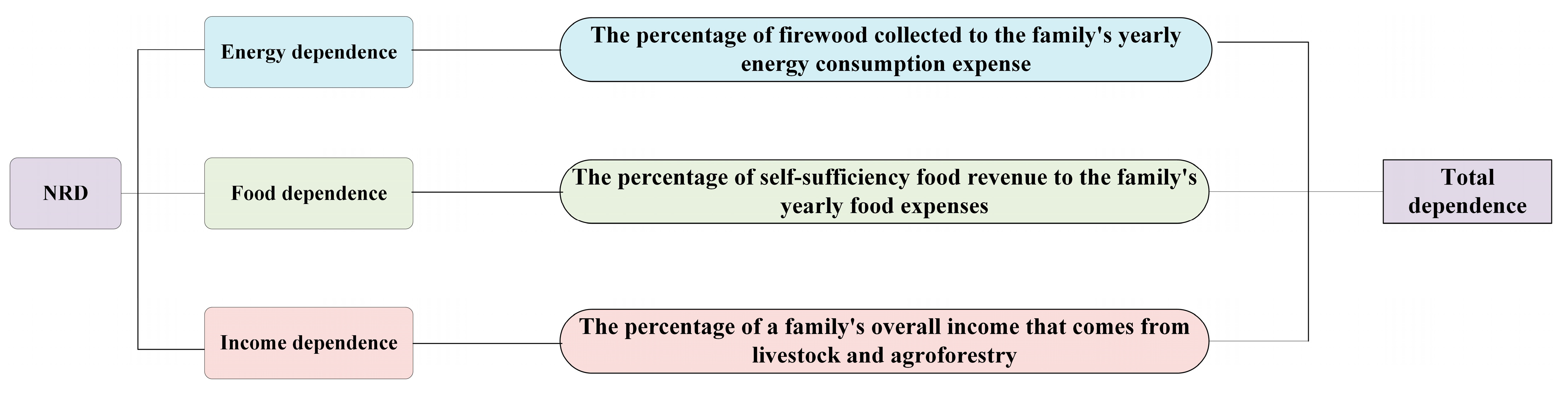

2.3.2. Household Natural Resource Dependence (NRD)

2.4. Regression Analysis Model

3. Results

3.1. Comparing the NRD of Different Types of Households

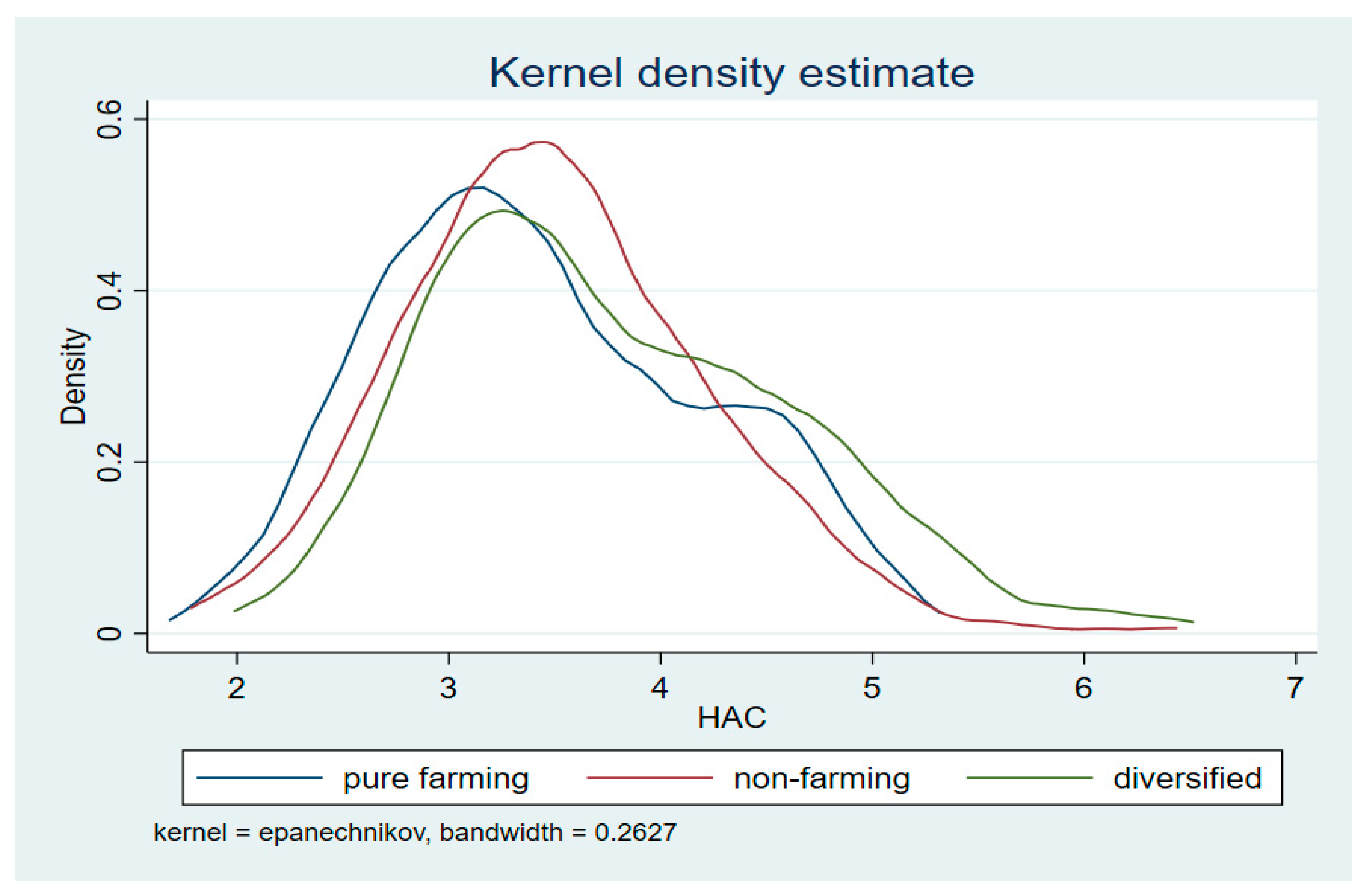

3.2. Comparing the HAC of Different Types of Households

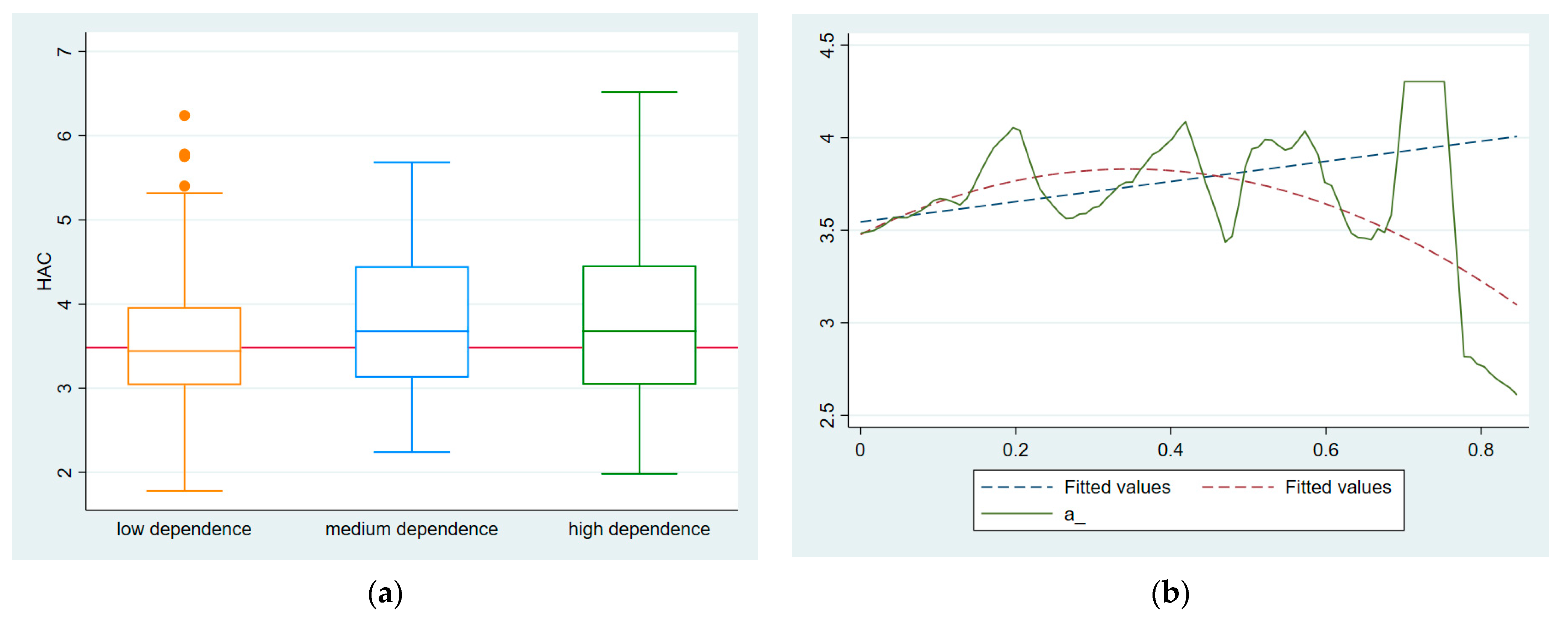

3.3. Analysis of NRD and HAC

3.4. The Influence of NRD on HAC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. Resettlement Fact Sheet; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.; Wilmsen, B. Towards a critical geography of resettlement. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; Saharan, T. Urban development-induced displacement and quality of life in Kolkata. Environ. Urban. 2019, 31, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Pittock, J.; Daniell, K. ‘Sustainability of what, for whom? A critical analysis of Chinese development induced displacement and resettlement (DIDR) programs. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, M.; Gan, C.; Voda, M. Residents’ Diachronic Perception of the Impacts of Ecological Resettlement in a World Heritage Site. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, W.; Li, J. Disaster resettlement and adaptive capacity among rural households in China. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2022, 35, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Project-induced displacement and resettlement: From impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ren, L.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Li, S. Exploring livelihood resilience and its impact on livelihood strategy in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zheng, H.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Zeng, W.; Liang, Y.; Polasky, S.; Feldman, M.W.; Daily, G.C.; et al. Impacts of conservation and human development policy across stakeholders and scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7396–7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, S.D.; Kulatunga, U.; Samaraweera, A.; Shanika, V.G. Cultural issues of community resettlement in Post-Disaster Reconstruction projects in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 53, 102017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.; Tsai, C.E. Coping with extreme disaster risk through preventive planning for resettlement. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 64, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; He, L.; Li, J.; Feldman, M. Illuminating sustainable household well-being and natural resource dependence in the case of disaster resettlement in rural China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 33794–33806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Feldman, M. Livelihood adaptive capacities and adaptation strategies of relocated households in rural China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1067649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.; Li, J.; Lo, K.; Guo, H.; Li, C. Moving millions to eliminate poverty: China’s rapidly evolving practice of poverty resettlement. Dev. Policy Rev. 2019, 38, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C. Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystem; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, S.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L. Natural resource dependence and urban shrinkage: The role of human capital accumulation. Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.T. Natural resource dependence and rural American economic prosperity from 2000 to 2015. Econ. Dev. Q. 2022, 36, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dong, K.; Wang, K.; Dong, X. How does natural resource dependence influence carbon emissions? The role of environmental regulation. Resour. Policy 2023, 80, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Ran, Q.; Razzaq, A. How does natural resource dependence influence industrial green transformation in China? Appraising underlying mechanisms for sustainable development at regional level. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.W.; Wen, Y.L. Evaluation of the dependence of rural households on natural resources based on factor returns. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. 2017, 27, 146–156. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, G.S.; Buerkert, A.; Hoffmann, E.M.; Schlecht, E.; von Cramon-Taubadel, S.; Tscharntke, T. Implications of agricultural transitions and urbanization for ecosystem services. Nature 2014, 515, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Peng, C.; Zhou, D.; Jiang, G. Pastoral household natural resource dependence and contributions of grassland to livelihoods: A case study from the Tibetan Plateau in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, S.; Selomane, O.; Sitas, N.; Blanchard, R.; Kotzee, I.; O’Farrell, P.; Villa, F. Human dependence on natural resources in rapidly urbanising South African regions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 044008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, M.J.; Feng, J.; Wen, Y.L. Analysis of natural resources dependence and its impact factors of surrounding communities: Taking giant panda habitat in Sichuan Province as an example. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2017, 33, 301–306. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Vedeld, P.; Angelsen, A.; Bojö, J.; Sjaastad, E.; Berg, G.K. Forest environmental incomes and the rural poor. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, N.L. Adaptive capacity and its assessment. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.H.; del Pilar Moreno-Sánchez, R. Estimating the adaptive capacity of local communities at marine protected areas in Latin America: A practical approach. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyng, H.B.; Macrae, C.; Guise, V.; Haraldseid-Driftland, C.; Fagerdal, B.; Schibevaag, L.; Alsvik, J.G.; Wiig, S. Exploring the nature of adaptive capacity for resilience in healthcare across different healthcare contexts; a metasynthesis of narratives. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 104, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, G.M.; Alam, K.; Mushtaq, S. Influence of institutional access and social capital on adaptation decision: Empirical evidence from hazard-prone rural households in Bangladesh. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Badola, R.; Ali, S.Z.; Jiju, J.S.; Tariyal, P. Adaptive capacity and vulnerability of the socio-ecological system of Indian Himalayan villages under present and predicted future scenarios. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 113946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami, M.; Zahraie, B.; Ghorbani, M. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of the dimensions of farmers’ adaptive capacity in the face of water scarcity. J. Arid Environ. 2022, 199, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallury, S.; Smith, A.P.; Chaffin, B.C.; Nesbitt, H.K.; Lohani, S.; Gulab, S.; Banerjee, S.; Floyd, T.M.; Metcalf, A.L.; Allen, C.R. Adaptive capacity beyond the household: A systematic review of empirical social-ecological research. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Costella, C. A framework to assess the role of social cash transfers in building adaptive capacity for climate resilience. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2023, 20, 2218472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaziira, J.; Egeru, A.; Bamutaze, Y.; Kisira, Y.; Nabiroko, M. Assessing the Dynamics of Agropastoral farmers’ Adaptive Capacity to Drought in Uganda’s Cattle Corridor. Clim. Risk Manag. 2023, 41, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursey-Bray, M.; Gillanders, B.M.; Maher, J. Developing indicators for adaptive capacity for multiple use coastal regions: Insights from the Spencer Gulf, South Australia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 211, 105727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, L.; Klein, R.J.; Reidsma, P.; Metzger, M.J.; Rounsevell, M.D.; Leemans, R.; Schröter, D. A spatially explicit scenario-driven model of adaptive capacity to global change in Europe. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Huo, X.; Peng, C.; Qiu, H.; Shangguan, Z.; Chang, C.; Huai, J. Complementary livelihood capital as a means to enhance adaptive capacity: A case of the Loess Plateau, China. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, M.; Li, S.; Feldman, M. The impact of the anti-poverty relocation and settlement program on rural households’ well-being and ecosystem dependence: Evidence from Western China. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2021, 34, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, S.; Feldman, M.W.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Daily, G.C. The impact on rural livelihoods and ecosystem services of a major relocation and settlement program: A case in Shaanxi, China. Ambio 2018, 47, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Duan, M.; Feldman, M. Exploring the relationship between vulnerability and adaptation of rural households: Disaster resettlement experience from rural China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1437416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezeer, R.E.; Verweij, P.A.; Boot, R.G.; Junginger, M.; Santos, M.J. Influence of livelihood assets, experienced shocks and perceived risks on smallholder coffee farming practices in Peru. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, J. Effects of disaster-related resettlement on the livelihood resilience of rural households in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. A conceptual framework for measuring livelihood resilience: Relocation experience from Aceh, Indonesia. World Dev. 2019, 117, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A. Measuring livelihood resilience: The household livelihood resilience approach (HLRA). World Dev. 2018, 107, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. What does the future hold for relocated communities post-disaster? Factors affecting livelihood resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 34, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating the role of livelihood assets in suitable livelihood strategies: Protocol for anti-poverty policy in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 78, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenstein, O.; Hellin, J.; Chandna, P. Poverty mapping based on livelihood assets: A meso-level application in the Indo-Gangetic Plains, India. Appl. Geogr. 2010, 30, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Asghar, M.M.; Malik, M.N.; Nawaz, K. Moving towards a sustainable environment: The dynamic linkage between natural resources, human capital, urbanization, economic growth, and ecological footprint in China. Resour. Policy 2020, 67, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baland, J.M.; Bardhan, P.; Das, S.; Mookherjee, D.; Sarkar, R. The environmental impact of poverty: Evidence from firewood collection in rural Nepal. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2010, 59, 23–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, K.; Wang, M. How voluntary is poverty alleviation resettlement in China? Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pormon, M.M.M.; Yee, D.K.P.; Gerona, C.K.O. Households condition and satisfaction towards post-disaster resettlement: The case of typhoon Haiyan resettlement areas in Tacloban City. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 91, 103681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmawan, R.; Clark, J. Resource dependence and the causes of local economic growth: An empirical investigation. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2021, 65, 596–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, A.; Clark, J. The effects of natural resources on human capital accumulation: A literature survey. J. Econ. Surv. 2021, 35, 1073–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ren, Q.; Yu, J. Impact of the ecological resettlement program on participating decision and poverty reduction in southern Shaanxi, China. Forest Policy Econ. 2018, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Luo, Y. Post-disaster resettlement and livelihood vulnerability in rural China. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2017, 26, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Kapucu, N. Examining livelihood risk perceptions in disaster resettlement. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2017, 26, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.; Xue, T. Resettlement and climate change vulnerability: Evidence from rural China. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xu, Y.; Ma, W.; Gao, S. Does participation in poverty alleviation programmes increase subjective well-being? Results from a survey of rural residents in Shanxi, China. Habitat Int. 2021, 118, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whether relocated | Household relocation = 1; non-relocation = 0 | 0.699 | 0.459 |

| Relocation type | Resettlement that is centralized = 1; scattered = 0 | 0.758 | 0.429 |

| Relocation nature | Relocation that is voluntary = 1; involuntary = 0 | 0.862 | 0.345 |

| Household size | The number of people living in the household (persons) | 4.496 | 1.608 |

| Dependence ratio | The ratio of youngsters and the elderly to the household’s total labor force (%) | 0.277 | 0.225 |

| Education level | Average years of education for household members (years) | 6.180 | 2.654 |

| Experience | Types of experiences for household members (1. Village leaders; 2. Technicians, educators, and doctors; 3. Workers at enterprises; 4. Military personnel; and 5. No previous experience) | 0.498 | 0.841 |

| Phone charge | Household members’ last-month phone charge (CNY) | 228.122 | 357.361 |

| Loan | The loan’s potential (certainly = 1, probably = 2, generally = 3, less likely = 4, and certainly cannot = 5) | 3.430 | 1.348 |

| Social support | The total amount of aid funds available (CNY) | 61.072 | 185.960 |

| Indices | Whether Relocated | Relocation Type | Relocation Nature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | t-Test | Centralized | Scattered | t-Test | Voluntary | Involuntary | t-Test | |

| Total dependence | 0.087 (0.006) | 0.238 (0.130) | 12.089 *** | 0.071 (0.006) | 0.142 (0.016) | 5.204 *** | 0.076 (0.006) | 0.162 (0.019) | 5.096 *** |

| Energy dependence | 0.097 (0.011) | 0.363 (0.022) | 12.365 *** | 0.066 (0.010) | 0.195 (0.029) | 5.486 *** | 0.073 (0.010) | 0.248 (0.038) | 5.993 *** |

| Food dependence | 0.032 (0.006) | 0.101 (0.147) | 5.259 *** | 0.023 (0.006) | 0.068 (0.015) | 3.316 *** | 0.034 (0.006) | 0.035 (0.013) | 0.052 |

| Income dependence | 0.131 (0.010) | 0.252 (0.022) | 5.758 *** | 0.124 (0.011) | 0.162 (0.022) | 1.635 | 0.122 (0.010) | 0.204 (0.035) | 2.913 *** |

| Indices | Whether Relocated | Relocation Type | Relocation Nature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | t-Test | Centralized | Scattered | t-Test | Voluntary | Involuntary | t-Test | |

| HAC | 3.529 (0.034) | 3.824 (0.063) | 4.420 *** | 3.477 (0.036) | 3.748 (0.084) | 3.423 *** | 3.500 (0.036) | 3.833 (0.101) | 3.348 *** |

| Awareness | 0.463 (0.011) | 0.478 (0.017) | 0.747 | 0.460 (0.013) | 0.486 (0.022) | 1.029 | 0.465 (0.012) | 0.474 (0.024) | 0.275 |

| Ability | 1.934 (0.023) | 2.316 (0.044) | 8.387 *** | 1.882 (0.023) | 2.112 (0.057) | 4.547 *** | 1.893 (0.023) | 2.224 (0.071) | 5.143 *** |

| Action | 1.132 (0.0200 | 1.030 (0.037) | −2.607 *** | 1.135 (0.022) | 1.143 (0.047) | 0.170 | 1.137 (0.022) | 1.136 (0.057) | −0.024 |

| Variables | Local Households | Relocated Households | Total Sample | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | |

| Total dependence | −0.004 | 0.913 *** | 0.606 *** | |||||||||

| Energy dependence | 0.078 | 0.474 *** | 0.351 *** | |||||||||

| Food dependence | −0.093 | 0.547 ** | 0.316 ** | |||||||||

| Income dependence | −0.030 | 0.305 ** | 0.211 ** | |||||||||

| Household size | 0.136 *** | 0.138 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.194 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.198 *** | 0.197 *** | 0.183 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.183 *** | 0.182 *** |

| Dependence ratio | −0.171 | −0.181 | −0.160 | −0.170 | −0.190 | −0.188 | −0.199 | −0.203 | −0.181 | −0.177 | −0.163 | −0.157 |

| Education level | 0.030 | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.039 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.406 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.042 *** | 0.041 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.045 *** |

| Experience | 0.382 *** | 0.385 *** | 0.380 *** | 0.382 *** | 0.246 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.239 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.2928 ** | 0.290 *** | 0.286 *** | 0.288 *** |

| Phone charge | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | 0.000 | 0.000 * | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 * | 0.000 * |

| Loan | −0.139 *** | −0.139 *** | −0.140 *** | −0.139 *** | −0.076 *** | −0.073 *** | −0.079 *** | −0.082 *** | −0.104 *** | −0.104 *** | −0.106 *** | −0.107 *** |

| Social support | 0.002 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.002 ** | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| Constant | 3.147 *** | 3.107 *** | 3.156 *** | 3.157 *** | 2.529 *** | 2.547 *** | 2.584 *** | 2.589 *** | 2.686 | 2.670 *** | 2.748 *** | 2.740 *** |

| R2 | 0.426 | 0.427 | 0.426 | 0.426 | 0.408 | 0.405 | 0.393 | 0.392 | 0.407 | 0.406 | 0.400 | 0.400 |

| N | 193 | 193 | 193 | 193 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 643 | 643 | 643 | 643 |

| Variables | Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | Model 19 | Model 20 | Model 21 | Model 22 | Model 23 | Model 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dependence | 0.459 *** | 0.835 *** | 0.778 *** | |||||||||

| Energy dependence | 0.263 *** | 0.424 *** | 0.385 *** | |||||||||

| Food dependence | 0.213 | 0.480 ** | 0.534 ** | |||||||||

| Income dependence | 0.140 | 0.285 ** | 0.248 * | |||||||||

| Whether relocated | ||||||||||||

| Relocated households | −0.126 ** | −0.127 ** | −0.182 *** | −0.179 *** | ||||||||

| Relocation type | ||||||||||||

| Centralized resettlement | −0.112 * | −0.113 * | −0.148 ** | −0.158 ** | ||||||||

| Relocation nature | ||||||||||||

| Voluntary relocation | −0.230 *** | −0.232 *** | −0.291 *** | −0.275 *** | ||||||||

| Household size | 0.184 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.185 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.194 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.180 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.194 *** | 0.193 *** |

| Dependence ratio | −0.195 | −0.191 | −0.189 | −0.184 | −0.179 | −0.177 | −0.182 | −0.185 | −0.177 | −0.176 | −0.180 | −0.185 |

| Education level | 0.038 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.040 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.036 *** |

| Experience | 0.290 *** | 0.288 ** | 0.285 *** | 0.286 *** | 0.243 *** | 0.235 *** | 0.237 *** | 0.245 *** | 0.245 *** | 0.237 *** | 0.239 *** | 0.246 *** |

| Phone charge | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 * | 0.0000 ** | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | 0.000 | 0.000 * |

| Loan | −0.100 *** | −0.101 *** | −0.101 *** | −0.102 *** | −0.073 *** | −0.071 *** | −0.075 *** | −0.078 *** | −0.080 *** | −0.078 *** | −0.085 *** | −0.086 *** |

| Social support | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| Constant | 2.807 **8 | 2.816 *** | 2.900 *** | 2.892 *** | 2.613 *** | 2.632 *** | 2.670 *** | 2.700 *** | 2.776 *** | 2.800 *** | 2.882 *** | 2.874 *** |

| R2 | 0.411 | 0.411 | 0.406 | 0.406 | 0.414 | 0.410 | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.420 | 0.416 | 0.411 | 0.408 |

| N | 643 | 643 | 643 | 643 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 |

| Variables | Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | Model 19 | Model 20 | Model 21 | Model 22 | Model 23 | Model 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dependence | 1.400 *** | 2.515 *** | 2.236 *** | |||||||||

| Energy dependence | 0.725 *** | 1.222 *** | 1.009 ** | |||||||||

| Food dependence | 0.588 | 1.295 * | 1.492 ** | |||||||||

| Income dependence | 0.505 * | 0.946 ** | 0.827 ** | |||||||||

| Whether relocated | ||||||||||||

| Relocated households | −0.270 | −0.292 * | −0.438 *** | −0.415 ** | ||||||||

| Relocation type | ||||||||||||

| Centralized resettlement | −0.305 | −0.319 | −0.413 ** | −0.433 ** | ||||||||

| Relocation nature | ||||||||||||

| Voluntary relocation | −0.805 *** | −0.807 *** | −0.976 *** | −0.922 *** | ||||||||

| Household size | 0.555 *** | 0.557 *** | 0.551 *** | 0.552 *** | 0.642 *** | 0.649 *** | 0.648 *** | 0.650 *** | 0.647 *** | 0.652 *** | 0.653 *** | 0.651 *** |

| Dependence ratio | −0.674 ** | −0.666 * | −0.617 * | −0.613 * | −0.744 * | −0.719 * | −0.675 | −0.714 * | −0.736 * | −0.712 * | −0.684 | −0.711 * |

| Education level | 0.105 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.105 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.116 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.110 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.114 *** | 0.113 *** |

| Experience | 0.765 *** | 0.754 *** | 0.744 *** | 0.750 *** | 0.725 *** | 0.692 *** | 0.686 *** | 0.714 *** | 0.722 *** | 0.691 *** | 0.689 *** | 0.711 *** |

| Phone charge | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | 0.000 | 0.000 * | 0.000 ** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Loan | −0.274 *** | −0.275 *** | −0.271 *** | −0.276 *** | −0.212 *** | −0.207 *** | −0.210 *** | −0.219 *** | −0.228 *** | −0.225 *** | −0.230 *** | −0.238 *** |

| Social support | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| R2 | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.041 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.044 | 0.048 | 0.044 |

| N | 643 | 643 | 643 | 643 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dou, B.; Xu, J.; Song, Z.; Feng, W.; Liu, W. Natural Resource Dependence and Household Adaptive Capacity: Understanding the Linkages in the Context of Disaster Resettlement. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187915

Dou B, Xu J, Song Z, Feng W, Liu W. Natural Resource Dependence and Household Adaptive Capacity: Understanding the Linkages in the Context of Disaster Resettlement. Sustainability. 2024; 16(18):7915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187915

Chicago/Turabian StyleDou, Bei, Jie Xu, Zhe Song, Weilin Feng, and Wei Liu. 2024. "Natural Resource Dependence and Household Adaptive Capacity: Understanding the Linkages in the Context of Disaster Resettlement" Sustainability 16, no. 18: 7915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187915