Abstract

Inherited and current trends of urbanization result in growing agri–urban mixed land use patterns that strongly call for innovative management and planning tools at the urban/rural interface. This could especially help to cope with both resilience and environmental fairness goals. In this framework, the category of the Agriculture Park (AP) deserves much attention in relating meaningful experiences, especially in Mediterranean areas. This article deepens the category with the aim of assessing its features as a viable tool in the planning domain to jointly protect and enhance peri-urban farmland areas. In particular, the adopted methodology taps into an integrated and holistic approach to define and assess, by design, a multi-purpose model of a Public Agri–urban Park (PAP) drawing on the Public–Private Partnership (PPP) management model (using break-even analysis to define the contents of the PPP itself), inhabitants’ participation, and referring to a typical fringe area in the municipality of Prato (Italy). Results show the potential of the PAP to jointly achieve—according to a proactive model of green spaces’ protection—many sustainable design targets along with new forms of services aimed at social welfare. At the same time, the article highlights the call for public bodies and agencies to overcome the “business as usual” and “silo-framed” institutional approach and establish fruitful collaborative and synergistic co-design procedures with inhabitants and local stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, especially in Europe and Western countries, urban encroachment has entailed the formation of settlements that have been characterized as “low-density” forms of urban sprawl [1]. Such a process entails the co-existence of urban activities and some peculiar forms of urban and peri-urban agriculture [2,3]. In these contexts, agriculture has been undergoing radical challenges for survival due to urban pressures that are paired with rather new socioeconomic and environmental opportunities. These particularly refer to the creation of sustainable and fair proximity markets related, for instance, to the recovery of the Local Agrifood System (LAFS) along with a recognized role for the provision of social and ecosystem services suitable to support profitable and sustainable agriculture [4,5,6,7].

In particular, considering the numerous functions in relation to the city and its habitability, agricultural operations inside peri-urban areas have been at the center of a cross-disciplinary debate due to the larger influences entailed by urban pressure [8,9].

As a result, urban growth entails the necessity of effective urban planning interventions at the urban/rural interface to cope with unprecedented agri–urban farming forms and patterns [10]. In addition, it also aims to recover a lost production/consumption “circular” metabolic relationship that for centuries featured urban/rural relationships and was lost due to the unfolding of the joint industrial and agricultural revolutions’ effects, which “disembedded” this local matter/energy mutual exchange pattern between urban and rural domains [11].

Accordingly, in a wider worldwide context, many public policy bodies have made meaningful steps with the aim of ensuring sustainable multi-functionality of peri-urban areas. For example, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) claims multi-functionality as a major inspiring principle within the agricultural sector [12], while the Economic European Social Committee [13] clearly underlines the need to devise new planning and management tools, featured as a contractual and shared form, to cope with the rising forms of agri–urban spaces and farming. This can stimulate actions and projects for the creation of new integrated and suitable economies to promote local markets, the quality of living, and the beauty of the places. From this perspective, the public is asked to actively support the production of market and non-market goods (e.g., ecosystem services) produced by agriculture while protecting the culture and natural environment of the areas through various policies, strategic planning, and land use regulations [14].

In this framework, innovative and integrative policies and planning tools are needed to manage agri–urban systems as well as peri-urban forest spaces to retrieve and reproduce agro-ecosystems that meet fundamental conditions for the liveability of human settlements by definition of an integrated management and design approach and tools.

Trying to cope with such a matter, urban planning disciplines and territorial sciences in general have been spending meaningful amounts of their reflection to “reframe” planning techniques, in order to incorporate an integrative management system based on agri-urban and agro-forestry acknowledged entities [15].

Particularly, the Agro–urban Park model—usually defined only as Agricultural Parks (AP) despite its mainly peri-urban collocation—has gained momentum in spatial planning and policy debates. It is considered a tool that can undoubtedly play a primary role in devising and experimenting with effective tools and planning practices to manage and design growing agri–urban domains [16]. In this regard, according to various contributions, introducing an AP entity can represent a promising approach to managing peri-urban areas in many parts of the world as they are designed to host traditional, sustainable, and suitable agricultural activities for local quality product markets while preserving natural habitats and preventing harmful urban expansion into green areas [17,18]. In addition, by preserving natural habitats and promoting sustainable agriculture, APs also offer social spaces for people to engage in environmental-protection-related activities like hiking and nature walks. Hence, multi-purposedly featured, the AP can support social fairness in accessing fresh foodstuffs, environmental benefits, and cultural and natural legacies along with the agrarian space’s structural enhancement. Additionally, AP can ensure the survival of networks of natural areas and the preservation of biological diversity, providing by design a high-quality landscape environment [19]. Accordingly, the introduction of APs can be a valuable strategy for managing peri-urban areas in many regions, helping to balance and feed urban transformations and resilience with environmental sustainability, farming profitability, and preserving important agricultural and natural resources for future generations [20]. Nevertheless, this kind of issue—despite the amount of contribution and study that also relates to the more suitable procedures and forms of institution and management—shows a general lack of insights to scrutinize about the economic feasibility and balance in order to allow PAPs to be established and last.

Based on the previous premises, the objective of this study is to deepen features and operational conditions related to the development of a Public Agri–urban Park (PAP) conceived as a new tool of spatial planning and management. In particular, the PAP’s nature will be scrutinized by referring to a contractual model—based on rules of redevelopment, transformation, and management of the agri–urban domain—that is suitable to frame and encourage actions and projects for the creation of new integrated economies to promote local markets, the quality of living, and the amenities of places. Based on these considerations, this article aims to set up and test a planning and design approach for a PAP development in reference to a typical peri-urban area in the municipality of Prato (Tuscany, Italy). The goal of this project is to devise a tool aimed at regenerating a settled peri-urban agro-ecosystem at the urban/rural interface and to reconnect and mend lost living connections between nature and culture, the place and local inhabitants by testing an innovative tool and methodology in the spatial planning field. This also accounts for the involvement of local actors in the planning choices and drawing on the joint activation of market and non-market services and goods.

In addition, this contribution is not only aimed at contouring the putative “just” design qualities and steps for a PAP set up but also to explore and verify under which management and financial feasibility conditions the PAP itself can be realistically defined and developed. In these terms, this study also deepens the public work nature of the PAP, which within the framework of European legislation must be guaranteed for at least the economic–financial feasibility, and encompasses the possibilities of start-up, development, and effective management.

In this regard, it is useful to rely on evaluation models that enable assessment, from the planning stage, of scenarios for the implementation of the initiative underlying the project.

Internationally, a number of techniques are used to evaluate land transformation (including real estate initiatives), which allow for judgments of convenience even among several alternative solutions. This is performed through the following techniques:

- -

- “Costing” (full costing, direct costing, advanced direct costing): breaking down costs by type (direct and indirect) and variability (fixed and variable) [21,22,23];

- -

- Discounted cash flow analysis (DCFA) to examine financial performance and risks [24,25];

- -

- Integration of economic and production data through cost–volume–profit analysis (CVPA) [26,27,28,29,30] that includes (i) break-even analysis (BEA) [31,32,33], which enables the estimation of break-even conditions in a production process; (ii) Contribution Margin Analysis (CMA) [34], which, in a production process, enables the estimation of the financial sums remaining after dealing with fixed costs for variable and extra-profit costs; and (iii) Operating Leverage Analysis (OLA) [35], which enables the assessment of the riskiness of a production process.

The application of CVPA (BEA, CMA, and OLA) has been also proposed for assessing the key financial data of a real estate initiative with respect to its physical and dimensional characteristics [36,37]; in particular, the Authors have proposed using BEA to determine the conditions for a settlement transformation initiative aimed at public land infrastructure to achieve ordinary market profitability given the economic and dimensional parameters found. Therefore, the BEA provides an essential input to calibrate the initiative, assuming the non-discharge on public resources. In this regard, for the assessment of the economic and financial feasibility of the PAP initiative, a BEA will be implemented aimed at understanding, in detail, the possibility (or not) of endogenous financing of the studied PAP, or, alternatively, additional eligible scenarios for the implementation of the project.

Drawing on these premises, this article unfolds as follows. After this introductory part, Section 2 presents a synthetic literary review of the key concept of AP that underpins the studio concept as a viable socio-ecological entity, planning and designing answers to provide “public and welfare service” management and production. Following, in Section 3, a methodological description of the approach and methods used in the design of the PAP of Prato with both its main goals are presented (Section 3.1), along with a description of the method adopted to assess the financial feasibility of the PAP project (Section 3.2). Section 4 highlights the results and findings of the design procedure adopted, especially pointing out the wide-ranging functionalities and spatial solutions entailed by the achieved project as well as its requirements in terms of public–private partnership solutions and agreements needed. Finally, Section 5, the discussion and conclusions, highlights the key points of what the adoption of the envisioned solution of the PAP entails in terms of innovation demands for the public policy domain as well as requiring better integration between spatial planning tools and agri-environment system management. This especially refers to a more holistic agro-ecological urbanism suitable to cope with current multifaceted transition challenges and supported by assessment tools and procedures.

2. Setting the Key Concept for This Study: The Literature Review of the Agricultural Park

Reflections on AP and the related literature contributions constitute a sort of “thought in action” that unfolds, often in a recursive way, along with the triggering and implementation of various experiences. In such a framework, we witness actions that anticipate theoretical statements as well as theoretical constructs trying to guide practice, which are often questioned and need to be better refined by relating to the plurality of the AP experiences.

Accordingly, we find out how the first known definition of an AP arises from a socially wide bottom-up movement that fueled and fostered the creation of the first and larger AP in Europe, the “Parco Sud Milano” (47,000 ha), in 1992. This park was conceived as a tool to protect a large prime farmland area by firstly maintaining a rentable and thriving farming activity along with its cultural and ecological values. In such a context, Ferraresi and Rossi [38] define the AP as “… a territorial structure aimed at primary production, to its protection and valorization, and assuming a secondary goal of leisure and cultural exploitation on behalf of citizens, while being compatible with the main activity. Both goals give place to different environments and structures in the park area. The valorization of the natural environment and the ecosystem balance raises as a necessary requirement in order to obtain the first two”.

Milan’s Parco Sud experience meaningfully crosses with the Spanish movement in this field in Catalunya—where creation of the first AP in Sabadell (2003) took place, and with it, a deep collaboration and exchange in the context of the Life Program 1996–1999 that paved the way also for the creation of the Parc Agrari de Baix de Llobregat (about 3500 ha). Since then, manifold experiences of AP flourished in this regional context when the Council for Nature Protection (CPN) issued an AP definition conceived as “…a confined space which purpose is to ease and to ensure the farming activity continuity, protecting it from its absorption in the urban process, promoting specific programs that allow for the development of its natural environment and socio-cultural economic potential and to protect the natural patrimony of surrounding areas…” [39].

Moreover, a strong call to support the multi-purpose and worth-valued functions of peri-urban farmland areas—preventing them from being encroached upon by the urban growth by adopting a cross-sector and innovative policy and design approach—came from the previously recalled Opinion on Agriculture in peri-urban areas of the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) [13]. Particularly, even without quoting the AP figure, the mentioned opinion document underlines the pivotal and strategic goals to preserve and enhance peri-urban agriculture according to a proactive approach and adopting a joint participative and multi-agent governance model along with integrated and cross-sectoral policies and planning tools. In this endeavor, the EESC opinion clearly recommends pursuing:

- Formally established bodies according to a Public–Private Partnerships (PPP) model as the subject of governance for the peri-urban farmland areas;

- The setting of “rural–urban intermunicipal projects” that, drawing on the collaboration of different municipalities and stakeholders, could manage an effective integration between the various policy sectors, especially integrating urban developments, food production, and agro-ecosystem protection.

Eventually, and more explicitly, the document outlines the importance of adopting an integrated planning regulatory system suitable to define an integrated conservation and development project for the spaces occupied by peri-urban agriculture.

The EESC’s opinion finds a meaningful consistency with the evolution of the AP concept that took place in Spain in the second half of the 1990s along with an intense development of AP creation projects and activities [40]. Accordingly, there evolved a further systematic approach that, drawing on the increasing experience accrued, was oriented not only to refine the concept and goals of an AP in terms of differences with other park entities (e.g., rural parks, natural parks, or urban parks) [41] but also to point out the pre-conditions for establishment as well as requirements/mechanisms and tools in order to set up and implement an operational model of an AP [42,43].

In such a reflection/action context, the very nature of the AP concept—despite its underpinning agriculture-related nature that entailed firstly addressing the protection of peri-urban farmland areas—has progressively shifted and enriched with joint and synergistic meanings and goals related to the enhancement of biodiversity and of long-lasting and inherited socio-cultural values [40]. Nevertheless, such a complex nature has revealed it necessary to count on some pre-conditions of the AP establishment and progress, based either on the public support on behalf of politicians and technical bodies as well as on farmers as key stakeholders of the AP management and development [44].

Then, in terms of implementation mechanisms, a collaborative approach between the various affected parties turned out to be pivotal and aimed to facilitate an integrated and balanced public/private governance process [45]. Along with this kind of collaborative governance, in order to comply with the original complex AP concept and goals, Zazo Moratalla [46] underlined how the aim of pro-active farmland area protection has to be achieved and hinges upon the following:

- Peri-urban farmland space and structure protection through landscape and urban planning tools;

- Pro-active measures and initiatives to economically enhance farming activities by adopting some tools of rural development and management plans.

Regarding the specificity of the AP, the pre-requisites, management principles, and mechanisms finally allowed the establishment of an AP “model” based on some specific tools that Zazo Moratalla [38] singled out as the following: the creation of a formally established management entity (Ente Gestor); the approval of a planning tool setting out land use rules (Plan de Ordenación Territorial); and the definition of a rural development plan (Plan de Desarollo) containing strategic guidelines, goals, and means for the AP implementation. Such a model was then further enriched by Zazo Moratalla [46] with the addition of an AP project of the park (Proyecto del Parque Agrario) sharing design visions on behalf of the various actors involved.

Despite this remarkable “all-encompassing” and framing AP statement, Paul and Zazo Moratalla [40] brought some remarks to this model, drawing on the study of a meaningful sample of a Spanish self-defined AP. In particular, they pointed out how planning coordination with other sectors and/or overarching development and planning tools were essential for success and needed to be achieved by the involved parties’, private and public, coordination. Secondly, but not less meaningfully, Paul and Zazo Moratalla’s study confirmed the relevance of APs in assuming a multi-functional profile and set of goals compared with the original, mainly agricultural image, encompassing environmental, cultural, and economic issues.

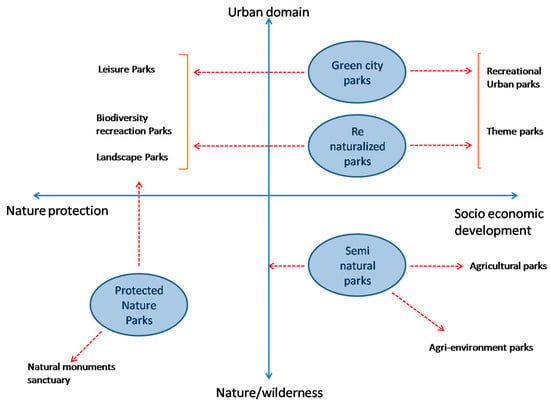

This very complex nature—as pointed out by Fanfani [16] in the framework of peri-urban natural area protection tools—allows for using the enhancement of the peri-urban agriculture system as a tool to achieve multi-purpose strategies by jointly and properly “modulating” socio-economic development and ecosystem protection requirements (see Figure 1). Finally, in these terms, as outlined by the literature survey, the AP turns out to be a key tool to devise and support integrated policies according to place-specific demands—especially when related to climate change challenges—by drawing on public/private parties’ cooperation and mutual interests. Relating to this matter, it is worth to note, particularly regarding this article’s purpose, how the AP has arisen lately as a new urban planning tool. It has been used to manage, on behalf of public parties, some key strategic rural peri-urban areas—also publicly owned—where private interests can be mobilized to comply, in terms of direct management, with public good delivering either in terms of local food provision, cultural values, or the ecosystem and leisure services [20,41,47,48]. It is at this stage that, when considering a specific situation of a study area, we will further test in the remaining part of the article the AP figure under the conditions of a Public Agriculture (or Agri–urban) Park (PAP), where the public land tenure regime sets some peculiar conditions to devise and develop the AP.

Figure 1.

Concept map of peri-urban park typologies according to the 4 typologies identified by the project (source, Fanfani for Peri-urban Parks Project—Interreg IVc, 2012).

3. Methods

3.1. Project Goals and Adopted Design Methodology

The idea of the PAP in the city of Prato is defined in order to enhance the role of its agricultural function and green spaces, in a mostly publicly owned area, by supporting local urban multi-functional agriculture as a key innovative design issue for urban resilience. This both regenerates the connections between the city and the close countryside at the urban/rural interface and enhances urban biodiversity supporting “green” spaces and endowments. Hence, the main objective of the PAP is to create a multi-functional component of the green infrastructure system in the west sector of the city to offer opportunities for both recreation and socialization, viable peri-urban farming activities, and supporting biodiversity. All that while proposing a model of innovative planning tools in contributing to building environmental resilience and fairness. Accordingly, the project sets out a series of specific objectives that, in line with the strategies described above, aim to promote the sustainable development of the territory and improve the quality of life of citizens. The main objectives of the project include the following:

- The recovery, conservation, and enhancement of the agricultural and landscape heritage;

- Promoting proximity in sustainable and profitable peri-urban agriculture;

- Improving ecological connectivity and biodiversity the urban fabric;

- The creation of public green spaces for leisure and socialization;

- Environmental education and local community awareness promotion on sustainability and food issues.

In order to achieve the strategic aims and goals just mentioned, the design approach draws on the well-suited Italian territorialist methodology, particularly referring to the concept of the urban bioregion model [49,50]. According to this approach, a co-evolutionary balance between environmental and social values and local development goals is pursued, drawing on the detection and acknowledgment of the long-lasting environmental, cultural, and territorial/urban heritage (patrimony) along with the social potentialities and design “volition” expressed by the local inhabitants and concerned stakeholders. In such a framework, the adopted methodology draws on an integrated and cross-disciplinary approach, involving and demanding different skills and knowledge in the fields of territorial planning, landscape architecture, agronomy, and environmental sciences. Accordingly, the adopted methodology design unfolded following some steps outlined in the Results Section that, after a general description of the framework where the design area is placed, include (i) the analysis of the local context along with the long-lasting settlement heritage structures as well as of the initiatives currently run by local actors; (ii) the definition of objectives and strategies of intervention and the co-design—also in collaboration with inhabitants and stakeholders of the main spaces—functional structures, and agro-ecological patterns of the park. In particular, this latter participative activity included three visits to the field for place surveys and to lead about twenty semi-structured interviews aimed at gaining advice on behalf of inhabitants about neighborhood life qualities and problems, along with the changes they would like. Moreover, we organized two open meetings in the evening with the inhabitants in collaboration with a local historical NGO of social and health assistance (Misericordia). During these meetings, an envisioning activity was developed—fed by the first survey and design idea results—to solicit and collect further observations and proposals from the inhabitants themselves.

Finally, step (iii) entailed the evaluation of the design strategies and elements relating to a viable management model and to the socio-economic feasibility impacts along with verification of the effectiveness of the actions to be undertaken as better specified in the following section.

3.2. Assessment of the Financial Feasibility

The economic–financial feasibility of a public project represents a key factor in its success, which is unfortunately often underestimated. It is highly dependent on the availability of allocable resources, on behalf of the proposing parties, and is reliant on the ability of the work to be carried out to generate income consistently over time and to maintain its efficiency. Thus, when the proposing party is public in nature and does not have resources but the service is required, this has to be able to generate income through the initiative to repay its construction costs as well as its operation and maintenance costs.

In the present case study, the PAP is configured as a public work that can be composed of spaces that maintain a meaningful role in terms of public access, or to provide tradable goods (e.g., foodstuffs) and services (e.g., recreational functions and amenities), with the latter which are only partially able to produce earnings as in the case of more conventional works whose functions are mainly intended to generate an income. Included in the type of space capable of generating income are all agricultural areas destined for foodstuff production and commercial and tertiary assets and services, within which complementary functions to the agricultural park may also be provided, referring also to the category of public, semi-public, and common goods (e.g., ecosystem services).

On the basis of such general considerations, the choice of the most appropriate evaluation model for the economic–financial sustainability of the initiative of realization of the agricultural park of Capezzana must take place starting from the assumption of verifying the existence of conditions for the feasibility and maintainability of the agricultural park according to an endogenous model; that is, by providing assets with uses and functions capable of generating income, i.e., the so-called “restorative assets”.

In particular, in order to appraise the assets—to restore the expenses into the hands of the public body that realizes and manages the agricultural park— the break-even analysis (BEA) is adopted. This allows the identification of the size of the ”restorative assets” of the costs (of realization) of the initiative by knowing the real estate values and having ascertained the presence of a market capable of appreciating certain types of real estate assets.

In technical terms, the ”break-even”, is an unknown q*, which is to say the minimum needed to repay the fixed and variable costs, thereby guaranteeing ordinary profitability in market terms for the project developer [36]:

where the fixed costs, FCtot, represent all expenses necessary to realize the agricultural park, except those related to the realization of the “accommodation center”.

In detail they are as follows:

- FCa concerns any market value of the buildings/area of intervention, if owned by the project developer including notary and registration expenses;

- FCd concerns the eventual demolition of pre-existing buildings;

- FCu includes works for the area’s urbanization and for rendering it suitable;

- FCt represents the construction (technical) cost or equipping costs of public buildings and areas including agro-environmental works such as hydraulic reticulation, planting of hedges and trees, paths, etc.;

- FCe concerns the technical expenses related to the fixed costs;

- FCf is the financial charges related to the fixed costs;

- FCo is other eventual fixed costs;

- RFC is the non-repayable public funding, which among the fixed costs can be considered but as a deduction.

The fixed costs may be estimated in a summary-direct fashion by obtaining comparables (direct sources) or through the aid of typological price listings (indirect sources).

The unit selling prices (Pu) regard the proceeds derived from the sale of “private” buildings that may be earned with the intervention. For a quick and, at any rate, effective implementation of the model, they are estimated in a summary-direct fashion taking account of the data provided by data banks that reveal selling prices.

The variable unit costs VCunit correspond to the production costs of the ”private” buildings that can be constructed with the intervention:

- VCt—construction (technical cost) of sellable buildings;

- VCe—technical expenses related to variable costs;

- VCc—concession charges;

- VCf—financial charges related to variable costs;

- VCp—ordinary promoter’s profit;

- VCu—unforeseen costs.

The variable costs are also estimated in a summary-direct fashion by obtaining comparables (direct sources) or through the aid of typological price listings (indirect sources).

The BEA allows, in short, to evaluate the initiative by considering its implementation costs and the property values (rental or concession) of the assets capable of generating income.

The PAP, by its nature, consists mostly of areas designated for agro–silvo–pastoral activities that in their implementation, require keeping the areas designated for such activities clean and cared for even when mostly accessible to the public.

The part of the PAP spaces that instead remains completely for public use (bicycle–pedestrian paths, leisure areas), requires negligible, albeit small, management and maintenance costs that are supposed to be compensated for by the rental/lease fees of the agricultural areas, even if they are capped.

Such an intervention hypothesis de facto transfers the PAP management and routine maintenance in the hands of the tenants, reducing the management–maintenance burdens of the public body (in this case, the Municipality of Prato). The complementary assets resulting from the premium building potential, on the other hand, generate “business” income, i.e., cash flows for each activity that can be settled in new refurbished and planned buildings. The premium building potential is a real estate value derived from corollary and complementary functions to the agricultural.

On the basis of the above, the BEA is thus configured as a useful tool to verify the economic–financial feasibility of the project in compliance with the assumptions described above; through the BEA it is then possible to weigh the project’s restorative assets, thanks to which the budget of the initiative can be achieved. In relation to the results of the BEA, different scenarios can be envisaged for the feasibility of the Capezzana PAP.

4. Results

4.1. The Project Context and Components

4.1.1. The Public Agricultural Park Area and Its Local Context

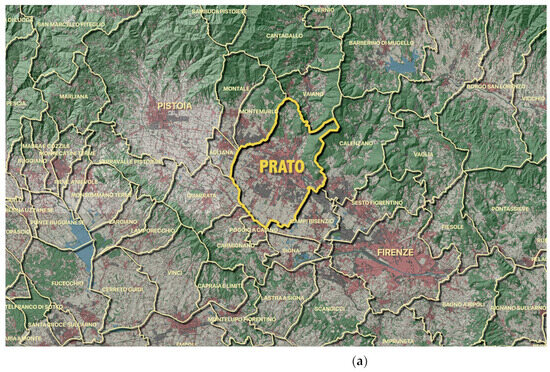

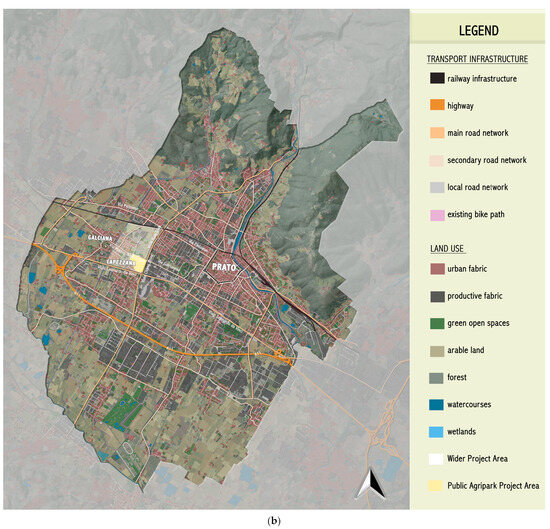

The study area where the design process for the Public Agricultural Park was developed concerns a typical peri-urban area located in the city of Prato, in the Tuscany region and in the west end of its plain metropolitan area (Figure 2a,b).

Figure 2.

(a) Prato and the surrounding metropolitan area. (b) Map of area study in Prato.

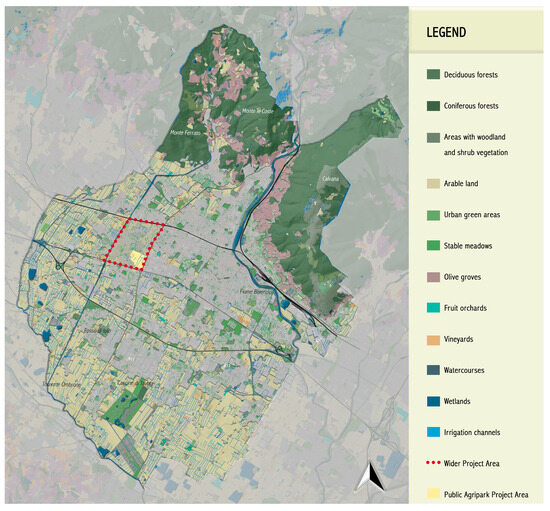

The design activity was continued, drawing on a formal agreement of collaboration on urban development and planning issues established between the University of Florence’s Architecture Department and the municipality of Prato. That is, in this case, under the form of research/action related to an MSc thesis in Urban and Regional Planning and Design elaboration of the same Department. Prato is a city with an important textile manufacturing tradition known above all for its intense industrial activity. Despite this “vocation” and the widespread process of urbanization, the territory of Prato has also maintained a strong presence of agricultural areas, often only partially enclosed, with interesting agro–urban patterns still characterized by significant agricultural use (Figure 3) [51].

Figure 3.

Map of the structure of green areas in relation to the built-up area in the municipality of Prato (from UdS Lamma, simplified).

In this context, this study aimed to verify the role of the PAP promoted as a public endowment placed in a publicly owned area as a policy and planning solution, sustainable and integrated, to promote local development and improve services, promote wellbeing, and the quality of life of citizens.

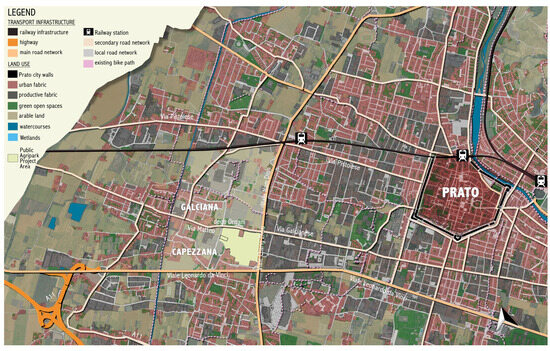

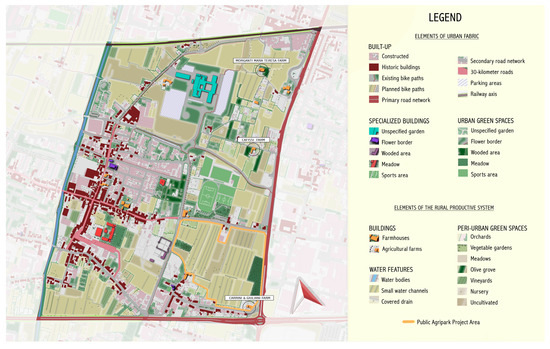

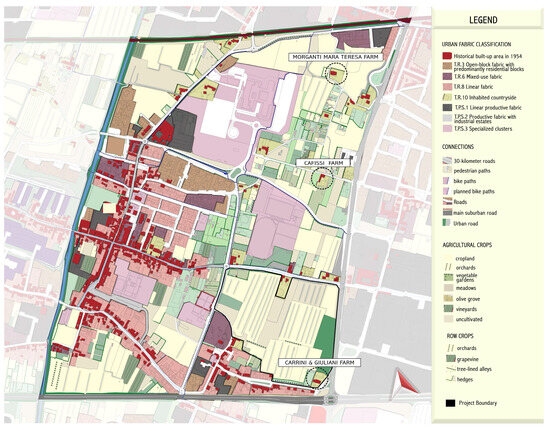

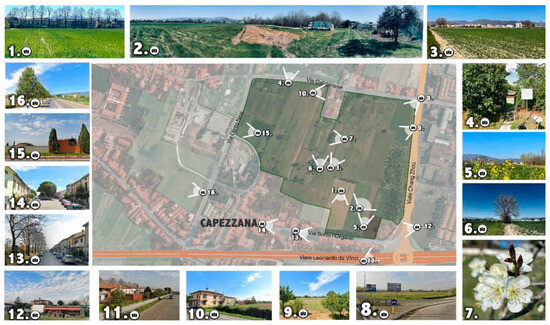

The study plot (Figure 4) covers about 16 hectares and it is located in the hamlet of Capezzana in the west quadrant of the municipality, touching the border of the nearby hamlet of Galciana in an area close to the compact fabric of the city. The area of intervention of the project relates to a territory characterized by a diversity of elements that includes agricultural areas featured with rather simplified agrarian patterns (Figure 5), abandoned industrial fringes, and green spaces while, in this case, the ownership of the soil is mainly of the municipality. The design study assumes and relies on the role of the “hinge” and interface of this area between urban and rural domains, and on its multi-functional nature. For this reason, the project is based on a series of principles and strategies that aim to enhance territorial resources, to create synergies between local active and potential actors based on the environmental, economic, and social sustainability of the actions undertaken.

Figure 4.

Land use and the study area plot position in the urban sector (in light yellow).

Figure 5.

Aerial view of the PAP designed area (inside the green line).

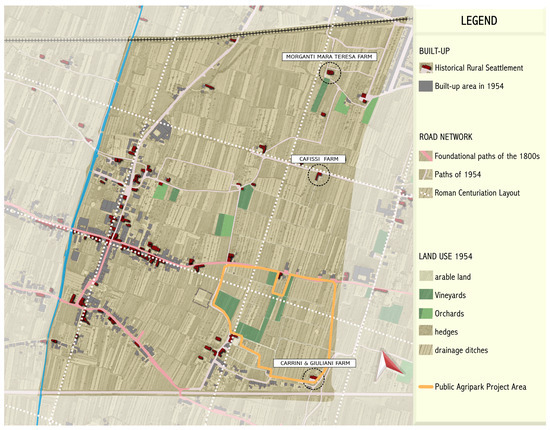

4.1.2. Study Area Features Long-Lasting Heritage Elements Analysis and Evaluation

According to the described methodology, the analysis of the project area focused on a set of aspects including the geography, geomorphology, hydrography, vegetation, fauna, and long-lasting cultural heritage and settlement patterns (Figure 6) as well as the current situation that crosses them with the current connective and functional structure (Figure 7). This analysis has allowed us to identify the resources and opportunities offered by the territory, as well as the problems and criticalities that must be addressed to ensure the implementation of a sustainable project consistent with the needs of the local community.

Figure 6.

Long-lasting settlement patterns and territorial heritage map; the design park area is within the orange line (source: authors’ elaboration on aerial photo GAI 1954).

Figure 7.

Historical settlement patterns and the current urban structure.

Particularly, the analysis showed the presence of some critical issues, including the fragmentation of the territory, the loss of agricultural land due to urbanization, the poor accessibility of green areas, and the need to improve the environmental and landscape quality of the area (Figure 5 and Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Functional and connective structure of the wider study area.

Nevertheless, the analysis phase allowed us to highlight the potential key role of the study area to recover and enhance a north–south green corridor suitable to create not only ecological continuity but also a buffer zone between the compact urban fabric at the east and the urban fringe, endowed also with many urban public functions to the west (Figure 8).

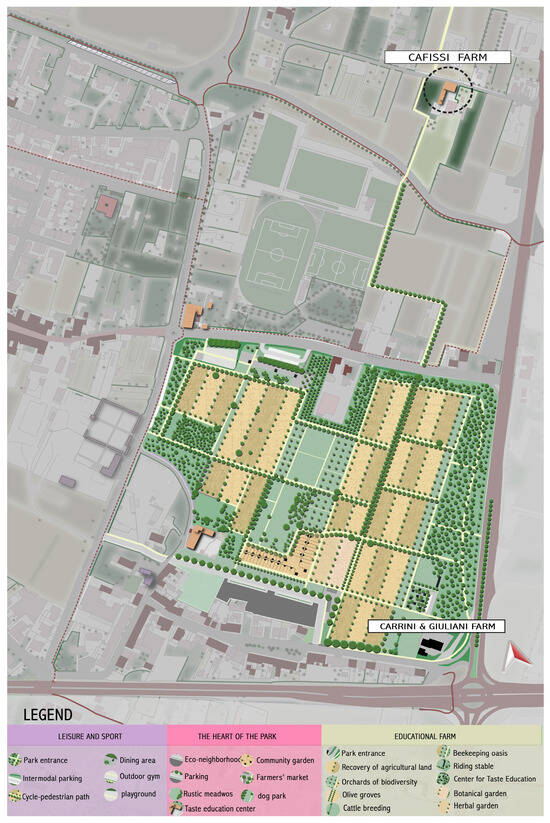

The analysis of this complex urban texture and also of the socio-economic features allowed us to reveal initiatives currently run and the related local actors that could support the main project goals, either referring to the specific design site or to a wider urban sector area. In particular, we could detect and highlight the presence of two relevant peri-urban farming activities (Cafissi Farm, Carrini-Giuliani Farm) (Figure 6 and Figure 7) both strongly carrying on a multi-functional urban farming activity. With the first one formally acknowledged as educational farm and agritourism and the second one directly exploiting the specific area studied for the PAP (Figure 9) and that can be considered as a “neighborhood farm”, source of socially oriented services (e.g., educational farm, proximity food provision and selling, green area maintenance).

Figure 9.

Pictures of the peri-urban farming activity in the PAP design area: Photos 1–7 views and details of the farmland design area; photos 8–16 views of the surrounding urban interface elements and buildings.

In addition, particular attention was paid to the social and cultural aspects of the territory, analyzing the demographic dynamics, local traditions, and other economic activities that characterize the area of intervention. In this case, the interviews and public meetings held confirmed the presence of meaningful active citizenship, showing a sense of belonging to place, a sensitivity to place stewardship, and a demand for the general enhancement of the quality and nature of public space.

4.2. Design Description: Decisions and Solutions

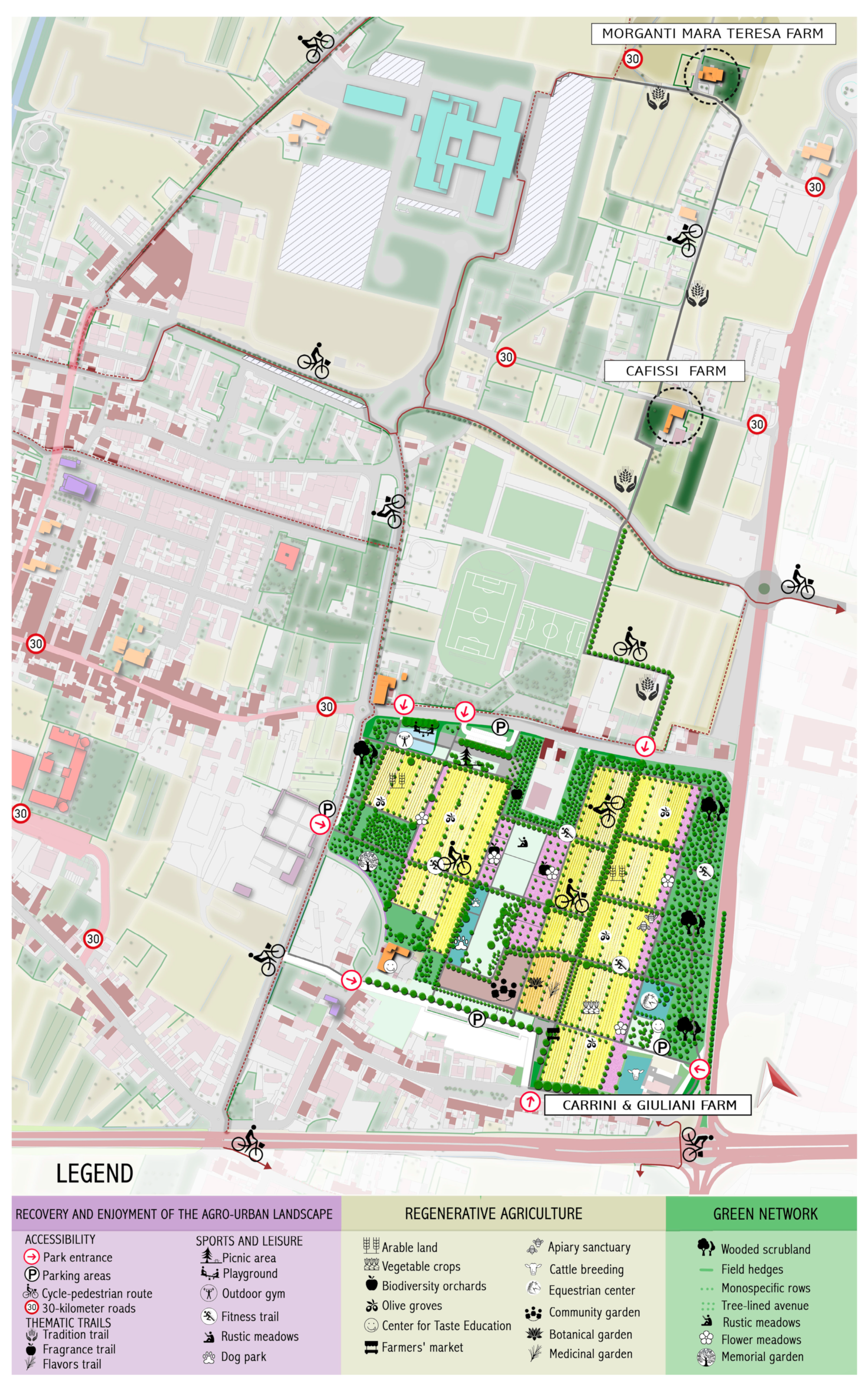

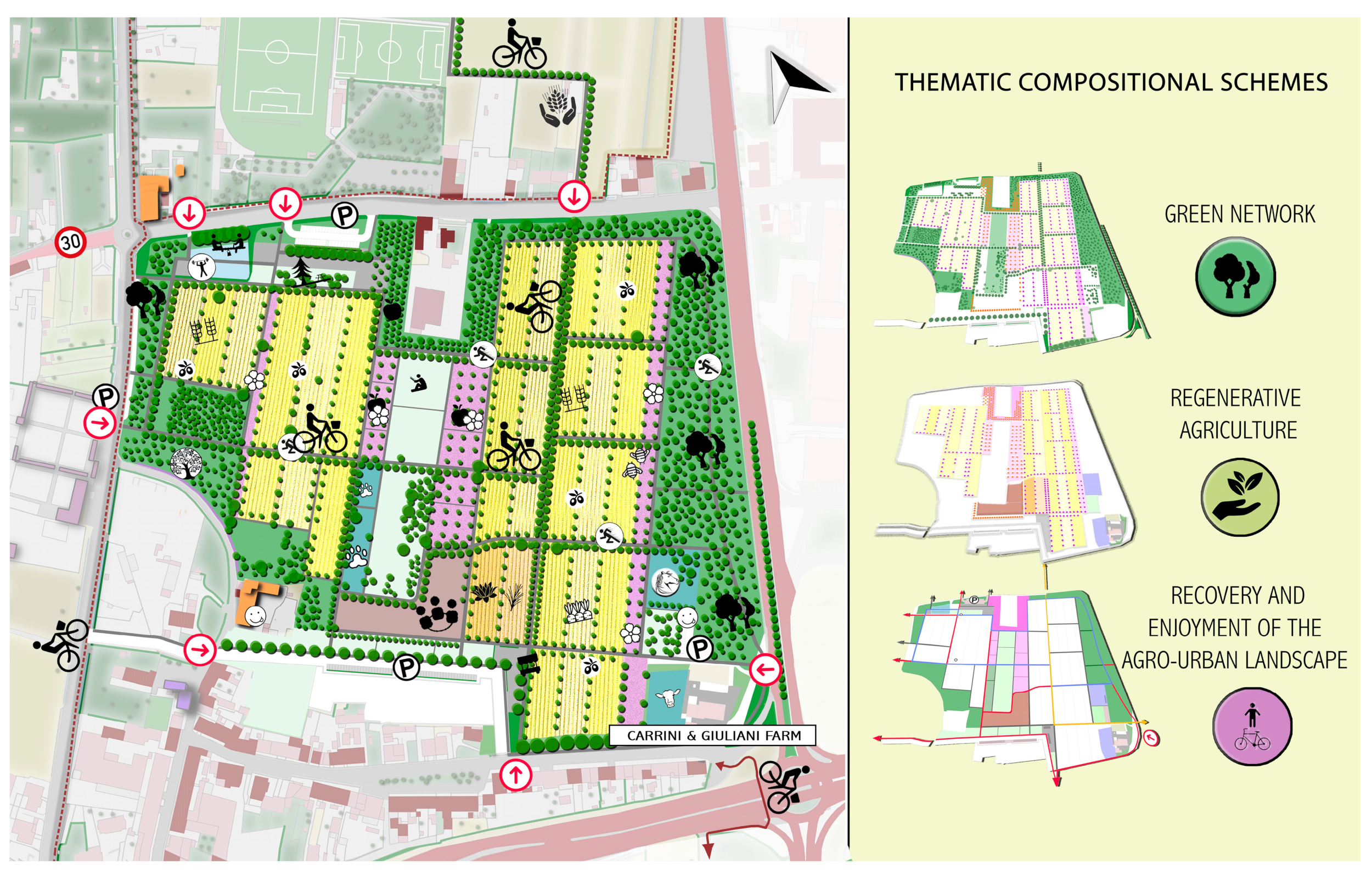

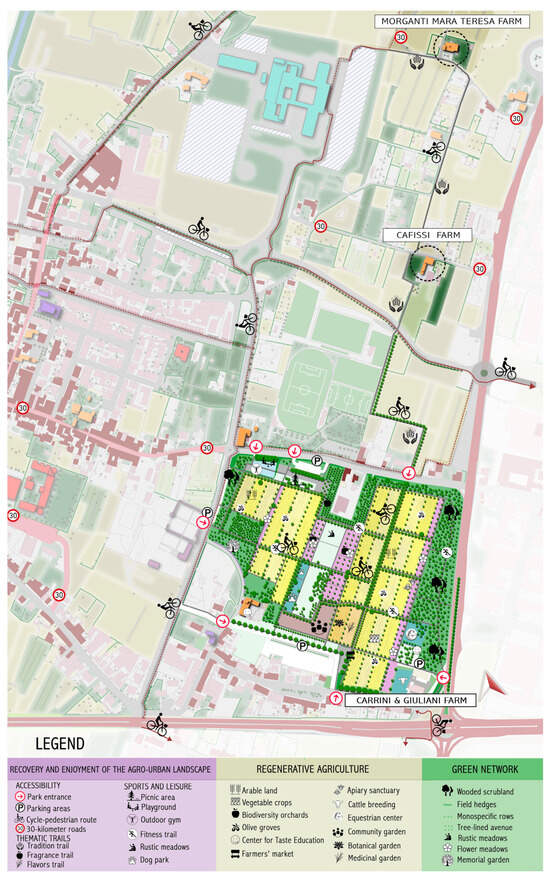

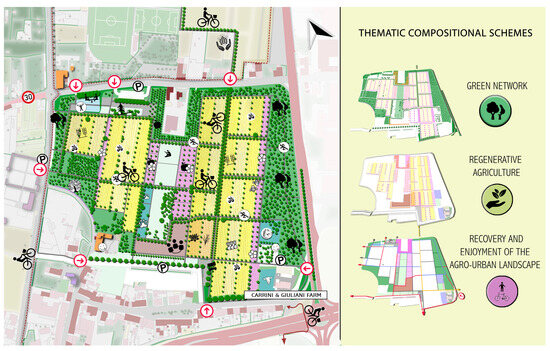

The design phase of the Agro–urban Park focused on the previously shown surveys and on the participative meeting with local inhabitants. The project was mainly interpreted as a connective intervention for a wider agri-urban area (Figure 10) that includes a series of solutions (Figure 11 and Figure 12) that aim to achieve the goals and strategies described above. The main interventions are as follows:

Figure 10.

Reconnection of the peri-urban green spaces in the wider design area: slow mobility tracks and new accessibility of green peri-urban spaces.

Figure 11.

Details of the specific design site: master plan of the Public Agricultural Park.

Figure 12.

Landscape regenerative project of the Public Agricultural Park for the specific design site.

- The redevelopment of agricultural areas and the promotion of sustainable agricultural practices through the introduction of crops with low environmental impact, the diversification of production, and the creation of food local supply chains;

- Relating to the above, the enhancement of current farming activity carried out on the site and the existing farm as a key stewardship actor to unfold and manage the park project with a multi-agent, active planning and design solution;

- The creation of a network of green spaces open to the public and green infrastructure, including small spots parks, urban gardening (e.g., community-supported agriculture), rest areas, along with cycling and walking paths in order to improve ecological connectivity, easy access to agro-ecological areas, and foster sustainable mobility;

- The implementation of restoration and enhancement of cultural heritage, such as the restoration of historic rural buildings for the promotion of viable cultural proximity tourism and didactic activities;

- The creation of public spaces and services for the local community, such as play areas, urban gardens, environmental education centers, and meeting points for socialization and exchange of knowledge and skills;

- The implementation of awareness and communication actions aimed at citizens and local actors to promote community participation and involvement in the project and its activities.

4.3. Governance and Management of the Project: Involvement of Local Actors and the Park Feasibility Appraisal

4.3.1. The Key Role of Public/Private Enduring Partnership Forms

As we have seen in the previous chapter, the successful Peri-urban Agricultural Park implementation largely depends on the setting of a suitable governance and management system, mainly drawing on public–private partnership models and tools [20,36].

According to these findings, the project study paid a peculiar amount of attention to the implementation phase as a critical one for the real and enduring development and implementation of the project, and, especially, to explore the criteria for a best-fitting solution—along with the public actor tenancy of the area—to jointly achieve the public and private synergies and benefits deriving from the scenario project [52].

In this direction, whereas management goals can be assumed as referred to in the project description and also draw on the methodology points previously highlighted, we can point out the particular need to involve a bottom-up and collaborative process with local stakeholders and inhabitants as well as—along with the municipality—the public agencies that can deliver resources, expertise, and advice about the various issue concerning the PAP implementation.

Relating to that, even though we could not anticipate the complexity of a public/private interactive process, this study highlights the importance of setting up a PPP entity suitable to jointly gather and actively involve all the possible social and economic contributors to the PAP purposes’ implementation, along with a stable and effective management entity for the PAP ordinary operations. In this direction, as preliminary steps, we have already defined—in collaboration with the municipality—the possibility to issue a public call drawing on this preliminary project, and to apply on behalf of private parties to propose a management model and goals to trigger the PAP kick-off and development. According to the operational approach to the project, we finally highlight how to devise the park implementation phase, which involves exploring and appraising some key socio-economic features. Accordingly, in the next paragraph—as result of the design methodology—we point out and evaluate the key issues entailed in the project in order to come up with the best suitable management solution criteria, in particular referring to the business model and to the public/private partnerships’ mutual roles, engagement, and resources deployment.

4.3.2. Conditions for Ensuring Financial Feasibility

BEA was applied to the project, described in this section, in order to identify the conditions of financial feasibility for the implementation of the PAP, based on the assumption (only as a starting assumption) that we do not want to resort to public financing. BEA thus denotes a public–private partnership (PPP) procedural operating model.

As anticipated in Section 3.2, it is assumed that the revenue from the lease of the agricultural areas, generating citizen interest in the use of the agricultural resources, is calibrated only because of the operation and maintenance of the PAP. To implement the BEA, the fixed costs, the variable costs, and the unit selling prices (proceeds) of the intervention case in the PPP (Table 1) were estimated.

Table 1.

BEA data for agricultural park.

The parametric costs needed to estimate the fixed costs and the variable costs were obtained from the appropriately updated Price Lists for Construction Types [53]. Regarding variable costs, referring to catering functions, commercial and tertiary uses are considered.

The unit selling prices (proceeds) were estimated taking into account the quotes surveyed by the Real Estate Market Observatory (Osservatorio del Mercato Immobiliare) at the Revenue Agency (Agenzia delle Entrate) [54] for the intervention area (second half of 2022, the latest available data), considering the average between the tertiary and commercial uses.

The break-even construction potential, for the intervention to be financially sustainable, equals the following (Formula (2)):

The alienable/rentable construction potential q*, equal to 4034 sqm, would make it possible to repay the costs of implementation of the PAP; although, as detailed below in the discussions, this parameter (which appears particularly impactful) raises critical issues about the feasibility of the project in the absence of public input, and with only private resources, a scenario with this construction potential placed within the PAP could be designed. This building potential may be intended for complementary functions (commercial, including those related to the marketing of agricultural park products; tertiary, for educational, recreational, cultural activities related to the agricultural production chain; recreational) but also lands on areas in the availability of the municipal administration, outside the agricultural park. The existing public buildings can be considered in this exchange; in this case, the value of the property divested by the Municipality should be considered by reducing the bonus building potential, also taking into account the risk related to the real estate development initiative, which can be provided in the same property [55].

The next Section is the Discussion for the BEA results, from which possible “hybrid” scenarios are derived for the implementation of the initiative, which given the size of the stock to refreshment suggest the need for public contribution or additional refreshment functions.

The Authors will discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. Moreover, the findings and their implications should be further discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Discussion

The Capezzana PAP represents an innovative project that aims to redefine the relationship between the city and countryside in the periurban western quadrant of the City of Prato. The territorialist design methodology adopted, in addition to a participatory and inclusive approach to involve the local community at each stage of the process, provides the key elements for a model of sustainable development that could be replicated in other urban and rural settings as an innovative planning and design tool to manage peri-urban green spaces as a new form of co-produced urban welfare.

The analysis of the project’s results—obtained by applying the territorialist methodology jointly with a socio-economic feasibility assessment model—highlighted that the Capezzana PAP enables to cope with the following aims:

- Integration of urban and rural environments: While many traditional approaches tend to treat the city and the countryside as two separate entities, the Capezzana PAP project aims to integrate these two environments into a single coherent system. This perspective makes the best use of the resources of both contexts, creating a balance between urban development and the protection of the remaining rural environment;

- Enhancement of the area qualities: Unlike projects that focus mainly on economic or infrastructural aspects, the Capezzana PAP places great emphasis on the recovery and enhancing the “heritage” features and endowments—built elements, environmental, scenic, and cultural features of the area. This approach makes it possible to protect and promote the local heritage, improving the quality of life of residents and making the area more attractive to citizens and visitors;

- Sustainability: The project is based on principles of regenerative environmental, economic, and social sustainability. It promotes environmentally friendly agricultural practices, and “food miles 0” products, contributing to a reduction in environmental impact. In addition, through the creation of local food markets and the promotion of sustainable proximity tourism, the project can stimulate the local economy at the neighborhood scale in a fair and sustainable way;

- Community participation: The Capezzana PAP aimed to actively involve the local community in all phases of the project. This participatory approach not only ensures that the project effectively meets the needs and expectations of residents but also promotes a sense of common ownership and responsibility for the area, strengthening the bond between people and their environment, supporting their sense of belonging to the place and stewardship practices;

- Education and training: The project, particularly drawing on -and aiming to enhance- the role of an existing “neighborhood” multifunctional farm, implies a strong educational component, particularly involving schools and educational institutions. It aims to improve awareness and understanding of the relationships between urban and rural environments, the importance of sustainable agriculture, biodiversity, and mindful consumption. This focus on education can have long-term positive effects, helping to form more informed, responsible, and active citizenship;

- Innovation: The Capezzana PAP turned out as a living lab for experimentation and innovation in agriculture and the environment at the urban/rural interface. This aspect distinguishes it from many other initiatives, allowing it to test and implement new ideas and sustainable solutions that could have a significant impact locally and perhaps transfer even more broadly in similar contexts;

- Health and wellness: Promoting a diet based on local, fresh, seasonal produce, combined with access to green areas for physical and recreational activities, can have positive effects on the physical and mental health of the community. The focus on natural therapy and wellness is an added benefit over conventional approaches;

- Sustainable mobility: Restoring the historic agricultural plot crossed by slow country bike/pedestrian tracks encourages an environmentally friendly mobility mode between the neighborhood and the urban center to reduce air pollution, improve air quality, and promote a more active lifestyle;

- Resilience and adaptation: The project fosters community and local resilience to the impacts of climate change through the conservation and enhancement of biodiversity, hedgerows, and tree canopies, the implementation of sustainable agricultural practices, improving soil rainfall absorption capacity and promoting a low-carbon local development model;

- Enhancement of cultural heritage: The project enhances not only natural heritage but also cultural, traditional, and built heritage by promoting knowledge and preservation of traditional agricultural practices, old crafts, and local traditions;

- Economy: The proposed PAP model can furthermore be recognized for supporting the creation of proximity agri-food markets that foreground 0-km products. Moreover, it promotes the rediscovery of sustainable agricultural practices that, while increasing awareness and respect for the environment and biodiversity, can support the development of a local food market suitable to make viable, also in economic terms, the rising local farming initiatives. In addition, further opportunities for self-funding, albeit partial, of the agricultural park also arise from the buildings restored and used for such activities for recreational, hospitality, and teaching initiatives as the answer to an increasingly diversified wellbeing urban demand;

- Financial sustainability: This is perhaps the most critical aspect, the results derived from the BEA point to only a partial ability of the PAP to generate enough of an inducement to be self-financing through PPP; it is a work that can be defined as “cold-tight” whose realization appears more consistent with a negotiated rather than a traditional PPP program. In fact, with regard to the operational implementation of the project, the BEA results return a “restorative” building potential of significant magnitude, setting the premises for requiring the support of a public contribution (of at least 50 percent of the agricultural park’s construction costs), or, alternatively, a greater characterization as a negotiated-type PPP of the PAP. Such a model could be reached, for instance, by providing space and buildings for equestrian recreation activities (riding stables), capable of generating additional income integrating the value of the agricultural assets’ revenues. This, alongside the concession of the existing public building, can be converted to tap into the new income-generating functions of PAPs relating to an increasing urban demand of leisure activities as well as for short “experiential” tourism activities.

6. Conclusions

The Capezzana PAP project enables potentially a series of ambitious goals to be achieved, with tangible and intangible results that allow it to positively permeate the entire surrounding area. The main purpose has been to create and test a paradigm shift in the perception and management of the relationship between the urban and rural environments as reference for planning tools and practice innovation. The advancement, in scientific terms, that the present applied research and design experience was aimed to produce, concerns particularly the applicability of the territorialist approach for urban–rural planning/design under the paradigm of the “urban bioregion”, with the implicit increase in awareness of the deep connection between the city and the countryside, unfortunately, often neglected in modern urban contexts and of fundamental importance in understanding the relevance of peri-urban farming to underpin sustainable urban patterns and activities.

As the project experience continued, the potential of the Capezzana PAP emerged as an innovative tool for the co-planning and co-design of the peri-urban territory and for managing the challenges it presents by overcoming traditional conceptual and operational “partitions” and silos within policy tools. In this, too, it represents an important development opportunity and example to be applied elsewhere in the Prato area and in other peri-urban contexts. Moreover, as witnessed by the assessment study, if properly applied and implemented, the project turned out as suitable to produce several positive outcomes, including the promotion of sustainable agriculture, biodiversity protection, environmental education, promotion of sustainable tourism, and local economic development. The challenge will be to implement the project in a participatory and inclusive way, involving the local community at every stage of the process. With the realization of these goals, the PAP can embody an exemplary model of how different aspects of urban and rural life can be integrated into one coherent and sustainable system at the urban/rural interface while responding to the current compelling demand for a resilient, sustainable, and fair transition. The resulting vision is of a future in which the city and countryside are no longer perceived as separate entities but as parts of a single socio-cultural and environmental whole. Given its innovative and cross-sectoral nature, however, the project poses a non-negligible challenge for the action of public administration, which has traditionally been aligned on path dependence models and articulated by “silos” where there is little dialogue and cooperation between the different sectors of public administration itself. This also raises the issue of a different way of collaboration between public and private bodies in addressing economic feasibility and management hurdles, thus recovering the role and importance of private actors not only in the management of public goods for the production of new forms of welfare but also for forms of “commoning” based on shared regulations aimed at the regenerative use of resources. For these reasons, further improvements of the research could be oriented to a Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Capezzana PAP, considering the financial results obtained through the BEA and to integrate the model based on financial evaluation with the mainly not tradable values provided in terms of ecosystem services. The success of the Capezzana PAP project will depend on the ability to meet these challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F. and F.B.; methodology, D.F. and F.B.; software, F.B. and B.A.; validation, D.F. and F.B.; formal analysis, D.F. and F.B.; investigation, D.F., B.A. and F.B.; resources, D.F. and F.B.; data curation, D.F. and F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.F., F.B. and B.A.; writing—review and editing, D.F. and F.B.; visualization, D.F., B.A. and F.B.; supervision, D.F. and F.B.; project administration, D.F. and F.B.; funding acquisition, F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Environmental Agency (EEA). Urban Sprawl in Europe—The Ignored Challenge; European Union Publications Office: Copenaghen, Denmark, 2006; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/eea_report_2006_10/eea_report_10_2006.pdf/view (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Galli, M.; Lardon, S.; Marraccini, E.; Bonari, E. (Eds.) Agricultural Management in Peri-Urban Areas. The Experience of an International Workshop; Felici: Pisa, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Piorr, A.; Zasada, I.; Doernberg, A.; Zoll, F.; Ramme, W. Research for AGRI Committee—Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture in the EU; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/617468/IPOL_STU(2018)617468_EN.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Van Veenhuizen, R.; Danso, G. Profitability and Sustainability of Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zasada, I. Multifunctional peri-urban agriculture—A review of societal demands and the provision of goods and services by farming. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, S.; Dell’Ovo, M.; D’Ezio, C.; Longo, A.; Oppio, A. Beyond food: Framing ecosystem services value in peri-urban farming in the post-COVID era with a multidimensional perspective. The case of Cascina Biblioteca in Milan (Italy). Cities 2023, 137, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfani, D.; Duží, B.; Mancino, M.; Rovai, M. Multiple evaluation of urban and peri-urban agriculture and its relation to spatial planning: The case of Prato territory (Italy). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mininni, M.V. From agricultural space to the urban countryside. Urban Plan. 2005, 128, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, A. The integration of Urban Agriculture into urban planning—An analysis of the current status and constraint. ETC-RUAF. In Annotated Bibliography on Urban Agriculture; CTA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Adell, G. Theories and Models of the Peri-Urban Interface: A Changing Conceptual Landscape. (Draft Report). In Strategic Environmental Planning and Management for the Peri-urban Interface Research Project; (Report not published); UCL-DPU: London, UK, 1999; Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/43/1/DPU_PUI_Adell_THEORIES_MODELS.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Davoudi, S.; Stead, D. Urban-Rural Relationships: An introduction and a brief history. Built Environ. 2002, 28, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- OCDE. L’Agriculture dans L’aménagement des Aires Périurbaines; OCDE (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development): Paris, France, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- European Economic Social Committee (EESC). Opinion on Agriculture in Periurban Areas. NAT/204, Brussels, 16 September 2004. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/opinions-information-reports/opinions/agriculture-peri-urban-areas (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Winne, L.; Cordell, D.; Chong, G.; Jacobs, B. Planning Tools for Strategic Management of Peri-Urban Food Production; Report for Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors; Institute for Sustainable future, University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2007; Available online: https://www.isurv.com/downloads/download/2103/planning_tools_for_strategic_management_of_peri-urban_food_production_rics (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Gottero, E.; Cassatella, C.; Larcher, F. Planning Peri-Urban Open Spaces: Methods and Tools for Interpretation and Classification. Land 2021, 10, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfani, D. Agricultural park in Europe as tool for agri-urban policies and design: A critical overview. In Agrourbanism. Tools for Governance and Planning of Agrarian Landscape; Gottero, E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, C.; Nougarédés, B.; Sini, L.; Branduini, P.; Salvati, L. Governance changes in peri-urban farmland protection following decentralisation: A comparison between Montpellier (France) and Rome. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montasell, J.; Callau, S. The Baix Llobregat Agricultural Park (Barcelona): An Instrument for Preserving, Developing and Managing a Periurban Agricultural Area. In Rurality near the City, Diputació de Barcelona, Spain, 2008. Available online: http://www.urban-agriculture-europe.org/files/callau_montasell_rural_near_the_city.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Sabaté, J. Reflexiones en torno al proyecto urbanistico de un Parque Agrario. In El Parque Agrario: Una figura de transición hacia nuevos modelos de gobernanza territorial y alimentaria; Yacamán Ochoa, C., Zazo Moratalla, A., Eds.; Heliconia S. Coop. Mad.: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A.; Fanfani, D. Il Parco Agricolo, un nuovo strumento per la pianificazione del territorio aperto. In Patto Città Campagna. Un Progetto di Bioregione Urbana per la Toscana Centrale; Magnaghi, A., Fanfani, D., Eds.; Alinea: Firenze, Italy, 2010; pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bubbio, A. L’activity Based Costing per la Gestione dei Costi di Struttura e Delle Spese Generali; Libero Istituto Universitario Carlo Cattaneo: Castellanza, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Drury, C.M. Management and Cost Accounting; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir, U.; Ozbay, I.; Ozbay, B.; Veli, S. Application of economical models for dye removal from aqueous solutions: Cash flow, cost-benefit, and alternative selection methods. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2014, 16, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, T.; Levengood, E.; Longfield, A.L. Using discounted cash flow analysis in an international setting: A survey of issues in modeling the cost of capital. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 1998, 11, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, R. Discounted cash flow analysis in property investment valuations. J. Prop. Valuat. Invest. 1996, 14, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M. Model sampling: A stochastic cost-volume-profit analysis. Account. Rev. 1975, 50, 780–790. [Google Scholar]

- Adar, Z.; Barnea, A.; Lev, B. A comprehensive cost-volume-profit analysis under uncertainty. Account. Rev. 1977, 52, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, B.E.; Louderback, J.G. Optimizing and satisficing in stochastic cost-volume-profit analysis. Decis. Sci. 1979, 10, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, G.M.; Ijiri, Y.; Leitch, R.A. Stochastic cost-volume-profit analysis with a linear demand function. Decis. Sci. 1981, 12, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.H. Cost-Volume-Profit analysis under uncertainty when the firm has production flexibility. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 1993, 20, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafferky, M. Breakeven Analysis: The Definitive Guide to Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis; Business Expert Press: New York, NY, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klipper, H. Break-Even analysis with variable product mix. Manag. Account. 1978, 59, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. Break-Even analysis: A unit cost model. CGA Mag. 1985, 31, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Horngren, C.T. A contribution margin approach to the analysis of capacity utilization. Account. Rev. 1967, 42, 254–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lev, B. On the association between operating leverage and risk. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1974, 9, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarini, M.R.; Battisti, F. A Model to Assess the Feasibility of Public–Private Partnership for Social Housing. Buildings 2017, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, P. La Stima Degli Indici di Urbanizzazione Nella Perequazione Urbanistica; Alinea: Firenze, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraresi, G.; Rossi, A. (Eds.) Il Parco come cura e cultura del territorio. Una Ricerca Sull’ipotesi del Parco Agricolo; Grafo Editore: Brescia, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Consell de Protecciò de la natura (CPN). Memoria 1994-95; Generalidad de Catalunya Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1996.

- Paul, V.; Zazo Moratalla, A. What is an Agricultural Park? Observations from the Spanish Experience. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periurban Parks Interreg IVc Project. 2012. Available online: https://www.europarc.org/library/project-archive/periurban-parks-project/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Yacamán Ochoa, C.; Zazo Moratalla, A. (Eds.) El Parque Agrario: Una Figura de Transición Hacia Nuevos Modelos de Gobernanza Territorial y Alimentaria; Heliconia S. Coop.: Madrid. Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zazo Moratalla, A. El Parque Agrario: Estructura de Preservación de Los Espacios Agrarios en Entornos Urbanos en un Momento de Cambio Global. Ph.D. Thesis, Escuela Politécnica de Madrid, Departamento de Urbanismo y Ordenación Territorial, Madrid, Spain, 2015. Available online: https://oa.upm.es/39083/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Montasell, J. La gestiò dels espais agraris a Catalunya. In La Futura Llei d’espais Agraris a Catalunya: Jornades de Reflexiò, Participació i Debat; Callau, S., Llop, N., Montasell, J., Paül, V., Ribas, A., Roca, A., Eds.; Fundació Agroterritori: Girona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A.; Fanfani, D. (Eds.) Patto Città Campagna. Un Progetto di Bioregione Urbana per la Toscana Centrale; Alinea: Firenze, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zazo Moratalla, A. Reflexiones sobre la protección de la base territorial del Parque Agrario: La institucionalización de su espacio agrario periurbano. In El Parque Agrario. Una Figura de Transitión Hacia Nuevo Modelos de Gobernanza Territorial y Alimentaria; Yacamán Ochoa, C., Zazo Moratalla, A., Eds.; Heliconia S. Coop.: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- République et canton de Genève. Un nouveau Parc Agro-Urbain à Bernex: Début des Travaux de Construction. (Communiqué de presse); Genéve. 2019. Available online: https://www.ge.ch/document/nouveau-parc-agro-urbain-bernex-debut-travaux-construction (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Spagnoli, L.; Mundula, L. Between Urban and Rural: Is Agricultural Parks a Governance Tool for Developing Tourism in the Periurban Areas? Reflections on Two Italian Cases. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaghi, A. The territorialist approach to the urban bioregion. In Bioregional Planning and Design. Perspectives on a Transitional century; Fanfani, D., Mataran Ruiz, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume I, pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Montasell, J. L’Espai Agrari: Un Territori Provocador. Consideracions I Propostes per la Preservació, la Gestió I el Desenvolupament Dels Espais D’interès Agrari de Catalunya; Instituciò Catalana d’Estudis Agraris: Barcelona, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ravetz, J. Deeper City. Collective Intelligence and Pathways from Smart to Wise; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guarini, M.R.; Battisti, F.; Buccarini, C. Rome: Re-Qualification program for the street markets in public-private partnership. A further proposal for the flaminio II street market. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 838–841, 2928–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIAM—Collegio degli Ingegneri e Architetti di Milano. Prezzi Tipologie Edilizie; DEI: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OMI Osservatorio del Mercato Immobiliare (Agenzia delle Entrate). Banca dati Delle Quotazioni Immobiliari. Available online: https://www.agenziaentrate.gov.it/portale/web/guest/schede/fabbricatiterreni/omi/banche-dati/quotazioni-immobiliari (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Battisti, F.; Campo, O. A model for determining a discount rate in market value assessment of buildable areas subject to restrictions. In Appraisal and Valuation; Morano, P., Oppio, A., Rosato, P., Sdino, L., Tajani, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).