Abstract

The Gulf of Gabès, located off the southern coast of Tunisia, is a region of significant ecological and economic importance, yet it faces a growing threat from abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear, commonly known as ghost gear. This paper addresses the urgent need for a comprehensive conservation code of conduct to mitigate the impacts of ghost gear on marine ecosystems and local communities. Drawing on data and insights from the Life MedTurtles and MedBycatch projects, as well as consultations with local stakeholders, we propose a set of principles and guidelines tailored to the specific socio-economic and political context of Tunisia. Our findings indicate that ghost gear not only endangers marine biodiversity but also affects the livelihoods of local fishers and the sustainability of the region’s fishing industry. The proposed code of conduct emphasizes the roles of government, local communities, and non-governmental organizations in implementing effective management strategies. We also explore the alignment of the proposed measures with existing international laws and policies, ensuring no conflicts arise while reinforcing global conservation efforts. This paper concludes by highlighting the feasibility of the proposed code within the Tunisian context, identifying potential challenges and opportunities for its implementation. Our recommendations aim to foster a collaborative approach to managing ghost gear, contributing to the long-term sustainability of the Gulf of Gabès and serving as a model for similar regions worldwide.

1. Introduction

Ghost gear, also known as “abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG)”, is a significant worldwide problem. It damages marine ecosystems and wildlife and poses challenges for fisheries management. The expansion of fishing fleets worldwide increases the likelihood of gear loss, especially as equipment becomes more durable and harder to decompose. Such gear mainly includes nets, trawls, longlines, pots, traps, and other devices utilized by both commercial and recreational fishers [1,2,3]. A recent study provided a comprehensive global estimate of the annual loss of fishing gear by surveying fishermen worldwide. The findings reveal that about 2% of all fishing gear is lost to the ocean, including a notable 739,583 square kilometers of longlines, along with significant amounts of other gear such as gillnets, purse seines, trawls, and millions of pots and traps.

The quantity of plastic released to the world’s oceans is in the order of 5 to 19 million tons per year and will triple by 2025 [4,5]. Abandoned fishing gear is considered a source of plastic pollution (e.g., nylon and propylene), which presents a major problem for marine biodiversity [6,7]. Every year, more than 600 tons of fishing gear is thrown away, abandoned, or lost in the seas and oceans, thus contributing to the distribution of marine and land debris [8,9,10]. Ghost gear severely impacts the marine environment by continuously trapping marine life, leading to injuries and death [10,11,12,13]. It damages sensitive habitats like coral reefs and seagrass beds, disrupting ecosystems [14]. This uncontrolled fishing depletes fish stocks [2], threatening biodiversity and sustainable harvesting. Economically, it burdens fishermen with the cost of replacing lost gear and reduces their overall catch, affecting livelihoods [5].

Ghost gear challenges fisheries management by worsening overfishing and supporting illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, which hampers sustainable fish stock management [15]. Fisheries management organizations and governments are increasingly focusing on addressing ghost gear to improve sustainable fisheries [16,17,18]. Addressing ghost gear demands international cooperation due to the interconnectedness of marine ecosystems and fisheries. Developing and implementing effective prevention and removal strategies hinges on collaboration among countries, regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and industry stakeholders [17]. Tackling ghost gear also involves several innovative approaches, such as redesigning equipment to lower entanglement risks, incorporating biodegradable materials, and utilizing technologies like GPS tracking and sonar to monitor gear placement and movement [14].

The Mediterranean Sea, with its high biodiversity and heavy maritime traffic, is particularly vulnerable to the impacts of ghost gear. Mitigation efforts have been conducted in this region to combat this environmental problem [19]. Various international and regional regulations aim to address ghost gear. The General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) developed technologies to reduce gear loss, while NGOs, governments, and community groups organized cleanup efforts for ghost gear. The MedSea Alliance is also addressing marine litter and ghost gear in the Mediterranean.

In Tunisia, despite the recognized importance of the Gulf of Gabès, there has been limited research and policy focus on the specific issue of ghost gear [19]. Although ALDFG is known to be the most damaging form of aquatic litter [9], the full extent of the issue along the Tunisian coastline remains largely unexplored. The initial study on the presence of ALDFG in the Gulf of Gabès was conducted under the Life MedTurtles Project [3]. This study encompassed a detailed inventory of ghost gear, an analysis of the key factors contributing to its loss, and a thorough mapping of its spatial distribution. This study was a groundbreaking initiative in the region, marking an initial effort to address and manage the escalating issue of ghost gear, and it underscored a serious environmental concern in the Gulf of Gabès (Video S1). While international frameworks such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries and the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) provide general guidelines for managing ghost gear, there is a pressing need for a tailored, context-specific approach that addresses the unique challenges faced by Tunisia.

This paper seeks to address this gap by proposing a conservation code of conduct specifically designed for the management of ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès. Building on the experiences and outcomes of the Life MedTurtles and MedBycatch projects, as well as extensive consultations with local stakeholders, we outline a set of principles and recommendations aimed at reducing the impact of ghost gear on the region’s marine ecosystems. Furthermore, we explore the socio-economic and political context of Tunisia to assess the feasibility of implementing such a code, ensuring that it aligns with national priorities and international obligations.

By proposing a code of conduct that is both scientifically informed and practically feasible, this paper aims to contribute to the sustainable management of the Gulf of Gabès, safeguarding its ecological integrity and the livelihoods of those who depend on it. The following sections provide a detailed analysis of the problem, the methods used to develop the code, the key findings, and the broader implications for marine conservation in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

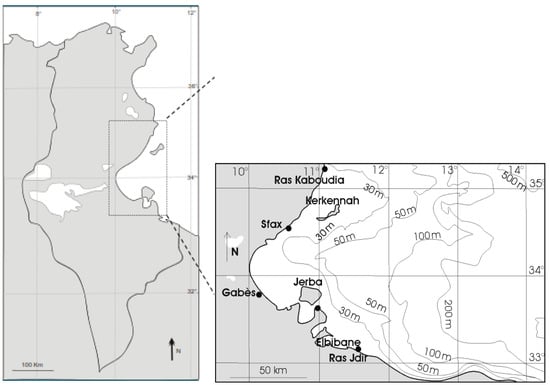

The study was conducted in the Gulf of Gabès (GSA 14), located off the southeastern coast of Tunisia (Figure 1). This region is notable for its pronounced tidal activity and expansive continental shelf. It is one of Tunisia’s most vital marine fishing regions and functions as a key hotspot for marine biodiversity with regional importance [20].

Figure 1.

Geographic overview of the Gulf of Gabès: key areas impacted by ghost gear.

The Gulf of Gabès is renowned for its vast Posidonia oceanica seagrass meadows, the largest in the Mediterranean Sea. This region serves as a vital habitat for various iconic species, including loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) [21], which use it as a wintering and foraging ground. It also acts as a nursery for several elasmobranch species [22,23] and supports numerous fish species [23]. Additionally, cetaceans, particularly the common dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), are frequently found in these waters [24]. The Gulf is also regarded as Tunisia’s primary shark–ray zone, accounting for over 60% of elasmobranch landings. It supports a diverse array of marine life, including 26 species of batoids and 35 species of sharks [24].

The boat number in the gulf is substantial, encompassing everything from coastal traditional sailing boats to advanced tuna vessels. In 2020, 6627 vessels operated in this zone, which represents about 51% of the Tunisian marine fleet, composed mainly of small-scale vessels, which represent 94% of the fleet [25]. However, it is also exposed to anthropogenic factors such as bycatch [26], overfishing, benthic trawling, accumulation of ghost fishing gear, and wastewater pollution, which are altering its natural characteristics.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to gather existing data on ghost gear impacts, management practices, and policy frameworks relevant to the Mediterranean region [1,19,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], with a focus on the Gulf of Gabès [4,41,42,43]. The review included academic papers, reports from international organizations, and documents from the Life MedTurtles and MedBycatch projects. The key sources provided insights into the prevalence of ghost gear, its ecological and socio-economic impacts, and existing mitigation strategies.

2.2.2. Stakeholder Engagement

To ensure that the proposed code of conduct is both practical and contextually relevant, we conducted a series of stakeholder consultations organized by the Life MedTurtles project. These involved workshops and meetings organized with local fishers, government officials, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and representatives from international conservation initiatives. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders to understand their perspectives on the causes of ghost gear, potential solutions, and the roles of different actors in implementing a code of conduct.

During the meetings and workshops organized by the Life MedTurtles project, we outlined the rationale for establishing a code of conduct and identified the stakeholders it would affect. We reviewed existing codes and international policies, discussed potential goals and principles for a code aimed at addressing ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès, assessed its possible benefits and challenges, and explored the next steps for developing and promoting this code within the marine conservation community. Workshop notes were analyzed to extract key themes (Figure 2).

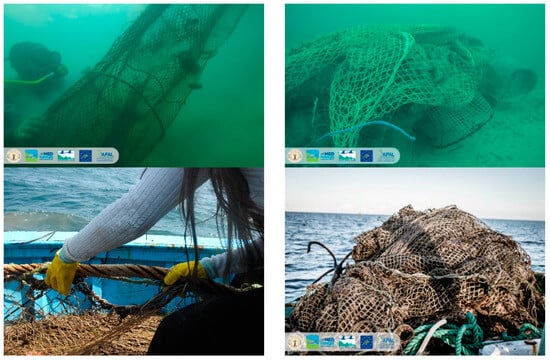

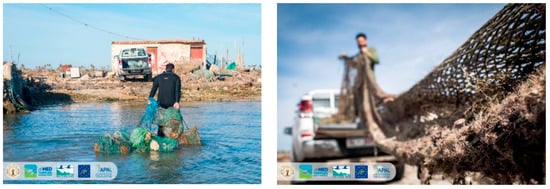

Figure 2.

Data collection and awareness campaign in the Gulf of Gabès (Tunisia).

2.2.3. Field Surveys

Field surveys were conducted in selected areas of the Gulf of Gabès to assess the extent of ghost gear accumulation. The surveys involved underwater visual surveys carried out by trained divers with the teamwork of the Life MedTurtles project to identify and document the presence of ghost nets and other fishing gear on the seafloor. Heatmaps produced by the Life MedTurtles project were used to analyze the spatial distribution of ghost gear and its proximity to key habitats such as seagrass beds and coral reefs.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data collected from literature reviews, stakeholder consultations, and field surveys were analyzed to identify patterns and key themes related to ghost gear management.

The socio-economic and political context of Tunisia was analyzed to assess the feasibility of implementing the proposed code of conduct. This involved evaluating the capacity of local institutions, potential barriers to implementation, and opportunities for alignment with existing policies.

2.4. Development of the Code of Conduct

The development of the code of conduct was informed by lessons from previous initiatives, by (i) drawing on successful conservation projects, both within Tunisia and internationally, to inform the structure and content of the code, (ii) ensuring that the proposed code aligns with relevant international agreements, such as the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries and the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI), and (iii) incorporating feedback from stakeholders to refine the principles and recommendations, ensuring they are actionable and supported by those who will be responsible for their implementation.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

All stakeholder engagements and field activities were conducted with full respect for ethical guidelines, ensuring informed consent, confidentiality, and the respectful treatment of all participants. The study was designed to benefit local communities by addressing a pressing environmental issue that affects their livelihoods.

3. Results

3.1. Extent and Impact of Ghost Gear in the Gulf of Gabès

The field surveys and stakeholder consultations revealed a significant presence of ghost fishing gear in the Gulf of Gabès. Underwater visual surveys documented numerous ghost nets and abandoned fishing gear, particularly in areas with high fishing activity (Figure 3). These ghost gear items were found entangled in seagrass meadows of the Gulf of Gabès, causing considerable damage to this critical habitat.

Figure 3.

Retrieval operations of ghost gear from the Gulf of Gabès.

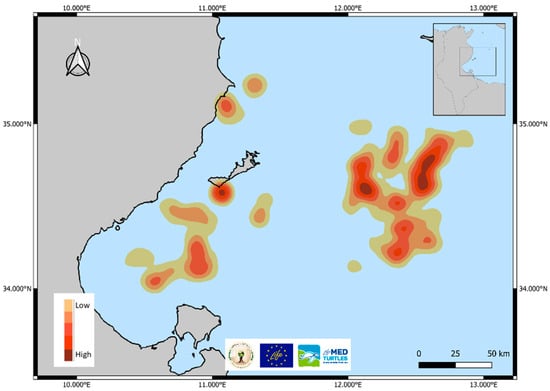

The mapping efforts confirmed that the distribution of ghost gear was concentrated in zones heavily utilized by local fisheries. The map shows two major areas where this seems to concentrate. The first one lies about 30 m south of Sfax and north of Djerba, the second one between 40 m and over 100 m along the Gulf of Gabès [3] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

ALDFG hotspots in the Gulf of Gabès.

The MedBycatch project in Tunisia, a joint effort focused on examining bycatch of at-risk species across different groups in Mediterranean fisheries, as well as creating and assessing effective solutions to address this issue, has confirmed that marine litter constitutes 2.42% of total trawler catches and only 0.47% of coastal fisheries catches. This marine debris for trawlers consists mainly of fishing gear (38.81%), clothing (0.66%), glass (1.67%), metal (22.45%), plastic (17.65%), rubber (17.42), and treated wood (1.33%).

The impact of ghost gear on marine life in the Gulf of Gabès is profound. Stakeholders reported frequent instances of entangled fish, sea turtles, and seabirds. The data indicated that ghost gear contributes to the decline of local fish stocks by continuing to capture marine organisms long after being lost or discarded. Additionally, the physical presence of ghost gear on the seabed was found to disrupt the natural behavior of marine species, leading to altered ecological dynamics in the affected areas.

3.2. Socio-Economic Implications

The socio-economic analysis highlighted the detrimental effects of ghost gear on the livelihoods of local fishing communities. Fishers reported economic losses due to reduced fish stocks and the damage ghost gear caused to their active fishing equipment. The presence of ghost gear also led to increased operational costs, as fishers had to invest more time and resources in removing debris from their nets and ensuring that their fishing grounds were clear of obstacles.

Stakeholder interviews revealed a strong awareness among local fishers of the ghost gear problem, yet a lack of resources and coordinated efforts to address the issue was apparent. While there is a general willingness among the fishing community to participate in ghost gear management, the absence of a clear regulatory framework and support from authorities has hindered effective action.

According to interviews with fishermen and all stakeholders to effectively address ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès, a multi-faceted approach involving a range of stakeholders is essential. First, policy development is a critical aspect of addressing the issue of ALDFG in the Gulf of Gabès. Second, Tunisian fishermen use a variety of methods to track and manage their nets, depending on the type of fishing and the resources available. Traditional methods applied include using buoys and markers to indicate the position of the nets. These are often brightly colored and can be seen from a distance, making it easier for fishermen to locate their nets. In some fishing communities, fishermen work together to track and manage their nets. They share information about the locations of their nets and help each other with retrieval and maintenance. GPS and other electronic tracking systems to monitor the location of their nets are not used. Third, fishing gear manufacturers, as the producers of the equipment used by fishermen, have a unique and influential role in addressing the issue of ghost gear management [1]. Manufacturers can lead the way in creating fishing gear that minimizes the risk of becoming ghost gear by using materials that are less prone to degradation and loss. Finally, users can contribute to the reduction and management of ghost gear through sustainable practices, active engagement in recovery initiatives, and collaboration with manufacturers.

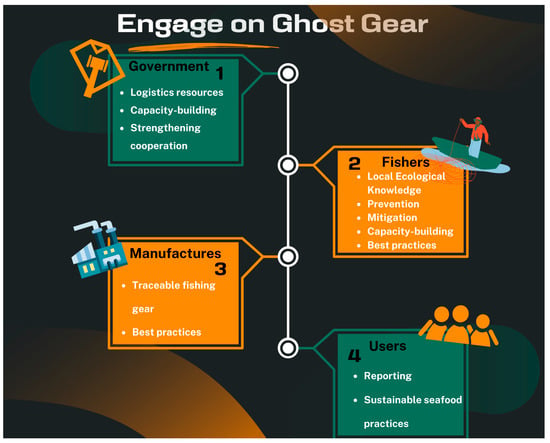

Building on management principles from the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), as well as findings from the Life MedTurtles and MedBycatch projects, we propose a draft code of conduct. This draft outlines the roles and responsibilities of four key stakeholders: government, fisher entities, manufacturers, and users (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Stakeholder engagement in developing a code of conduct for ghost gear management along the Tunisian coast (Gulf of Gabès).

3.3. Development of the Proposed Code of Conduct

Based on the analysis of stakeholder feedback and the field data, a comprehensive code of conduct was developed to address the ghost gear issue in the Gulf of Gabès. The code is structured around four key principles:

- i.

- Sustainability: Emphasizing the need for sustainable fishing practices that minimize the risk of gear loss and ensure the long-term health of marine ecosystems.

- ii.

- Responsibility: Outlining the responsibilities of various stakeholders, including fishers, government agencies, and NGOs, in preventing, retrieving, and managing ghost gear.

- iii.

- Collaboration: Promoting collaborative efforts among local communities, international organizations, and governmental bodies to effectively tackle the ghost gear problem.

- iv.

- Innovation: Encouraging the adoption of innovative technologies and methods for ghost gear detection, retrieval, and recycling.

The proposed code includes specific recommendations for gear marking, reporting of lost gear, incentives for gear retrieval, and the establishment of designated disposal sites. These recommendations are designed to be aligned with existing international policies, ensuring that the code does not conflict with any international agreements or standards.

3.4. Feasibility and Challenges

The feasibility of implementing the proposed code of conduct was assessed through discussions with local stakeholders and an analysis of the current socio-political landscape in Tunisia. The findings suggest that, while there is strong support for the code’s principles, several challenges need to be addressed to ensure successful implementation. These challenges include limited financial resources, the need for stronger institutional frameworks, and the necessity for capacity-building initiatives to empower local fishers and authorities.

The code was generally well received by stakeholders, who recognized its potential to mitigate the ghost gear problem and improve the sustainability of the Gulf of Gabès’ fisheries. However, stakeholders emphasized the importance of government involvement and the need for clear enforcement mechanisms to ensure compliance with the code.

3.5. Case Examples and International Alignment

To illustrate the practicality of the proposed code, case examples of successful ghost gear management initiatives from other regions were included (Table 1). For instance, the “polluter pays” principle, successfully implemented in other Mediterranean countries, was highlighted as a potential model for Tunisia. The alignment of the proposed code with international frameworks such as the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) and the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries was also demonstrated, reinforcing the code’s legitimacy and relevance on a global scale.

Table 1.

The main international, regional, national, and non-governmental legal instruments relevant to the management of ghost gear.

3.6. Draft Code of Conduct for Ghost Gear Management in the Gulf of Gabès (Tunisia)

Article 1: Purpose and Scope

- 1.1

- The Code of Conduct aims to establish guidelines for responsible fishing practices, gear management, and collaborative efforts to mitigate the impact of ghost gear in Tunisia. It applies to all stakeholders, including fishermen, gear manufacturers, NGOs, and government agencies.

- 1.2.

- This Code was developed as part of the Life MedTurtles project. The first paper on this topic in the framework of the project [3] provides essential insights into the impact of ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès and improved sustainable practices and fisheries management in the area. Certain sections of this document are grounded in pertinent international legal rules, including those outlined in the “Towards G7 Action to Combat Ghost Fishing Gear” initiative. Additionally, the Code features provisions that may be or have already been made binding through other mandatory legal instruments, such as those from the “Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)”, the “Environment Directorate (ENV)”, and the “Trade and Agriculture Directorate (TAD)”, in collaboration with the “Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI)” and the “UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)”. The proposed Code of Conduct also aligns with international policies and legal frameworks and does not conflict with any existing international agreements or policies, and it is designed to complement and support existing conservation and marine management efforts.

- 1.3.

- The Code is locally tailored to the Gulf of Gabès area of Tunisia, aimed at conserving the marine Mediterranean biodiversity by reducing the number of incidental entanglements and deaths of sea turtles, cetaceans, sharks, and other megafauna found in this area.

- 1.4.

- The objectives of the Code are as follows:

- i.

- Set policies according to relevant international standards and guidelines, to promote sustainable and environmentally friendly fishing practices and to minimize gear loss and its impact on marine species, particularly in the Gulf of Gabès, taking into account all its relevant environmental, social, biological, commercial, technological, and economic aspects;

- ii.

- Act as a reference tool to assist national authorities in developing or enhancing the legal and institutional frameworks needed for responsible fishing. It also supports the formulation and implementation of measures that promote accountability and responsible behavior among all stakeholders;

- iii.

- Foster cooperation among fishermen, manufacturers, NGOs, and regulatory bodies to address ghost gear issues;

- iv.

- Support the development and use of innovative technologies and practices for preventing and recovering lost gear;

- v.

- Ensure open reporting and monitoring of ghost gear incidents and management activities.

Article 2: General Principles

2.1. Sustainability

Fishing practices should be conducted in a sustainable manner, minimizing the risk of gear loss. For example, the use of biodegradable materials in fishing nets can reduce the long-term environmental impact if the gear is lost. This principle aligns with the “United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization” (FAO)’s guidelines on responsible fishing practices, emphasizing the need for sustainability in resource management. This is also consistent with reports from various international organizations such as GGGI, UNEP, NOAA, Greenpeace, and World Animal Protection that identify ghost fishing gear as the most harmful form of marine debris [17,29,36,37,38,39].

2.2. Responsibility

All stakeholders, including fishers, authorities, manufacturers, and NGOs, have specific responsibilities in managing ghost gear. Fishers, for instance, must ensure proper gear maintenance and report lost gear, while government agencies should enforce regulations and provide support for retrieval efforts. This principle is in line with the “Polluter Pays” principle under international environmental law, which holds that those responsible for pollution should bear the costs of managing it.

2.3. Collaboration

Effective management of ghost gear requires collaboration among local, national, and international stakeholders. An example of this is the partnership between the GGGI and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which provides a platform for sharing best practices and resources. The Code encourages similar collaborations to enhance ghost gear management in the Gulf of Gabès.

2.4. Innovation

Adopting innovative technologies such as GPS tracking and biodegradable nets can significantly improve the detection and retrieval of ghost gear. For instance, the use of underwater drones for ghost gear retrieval has proven effective in other regions. This aligns with international efforts to promote the use of technology in marine conservation, as emphasized in the FAO’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries.

Article 3: Gear Marking and Reporting

3.1 Gear Marking

All fishing gear must be clearly marked with unique identifiers to facilitate traceability. This practice is consistent with the guidelines provided by the FAO and GGGI, which recommend gear marking as a critical step in managing ghost gear. For example, the use of RFID tags on nets allows for easy identification and recovery of lost gear.

3.2. Reporting Lost Gear

Fishers are required to report any lost or discarded gear immediately to the relevant authorities. This system will be supported by a centralized reporting platform, modeled after successful initiatives in other regions, such as Norway’s ghost gear reporting system. This aligns with the FAO’s emphasis on transparency and accountability in fisheries management.

Article 4: Retrieval and Disposal of Ghost Gear

4.1 Retrieval Programs

Incentivized retrieval programs shall be established to encourage the recovery of ghost gear. These could include financial rewards, subsidies for gear recovery, or community recognition programs. An example is the “Fishing for Litter” initiative in Europe, where fishers are rewarded for collecting marine litter, including ghost gear.

4.2. Designated Retrieval Zones

Authorities will identify high-risk areas for ghost gear accumulation and designate them as retrieval zones. This approach is supported by international best practices, such as the creation of retrieval zones in the North Atlantic, which have proven effective in reducing ghost gear. These efforts should also be coordinated with neighboring countries to address transboundary ghost gear issues, consistent with the UNCLOS provisions on marine pollution.

4.3. Disposal Facilities

Facilities for the environmentally responsible disposal or recycling of retrieved ghost gear will be established. This aligns with the FAO’s recommendations on reducing marine litter and the GGGI’s emphasis on creating a circular economy for fishing gear.

Article 5: Education and Awareness

5.1. Educational Campaigns

Comprehensive educational campaigns will be launched to inform fishers and local communities about the impacts of ghost gear and the importance of sustainable fishing practices. These campaigns will draw on international models, such as the GGGI’s outreach programs, and be tailored to the socio-economic context of Tunisia.

5.2. Training Programs

Training programs will be provided to fishers and other stakeholders on best practices for gear management and retrieval. This will include workshops and seminars, possibly in collaboration with international bodies like the FAO, to ensure that participants are well versed in the latest techniques and technologies.

Article 6: Supportive Legislation

6.1. National Legislation

The government should develop and enforce legislation that supports the management of ghost gear.

The Law no. 94-13 of 31 January 1994 on the Exercise of Fishing governs the overall management of fisheries in Tunisia. It includes provisions on the sustainable exploitation of marine resources. While the law does not explicitly address ghost gear, its focus on sustainable practices and ecosystem protection provides a legal basis for actions against ghost gear pollution. The prevention and retrieval of lost gear can be interpreted as part of the broader responsibility of fishers to avoid environmental harm.

The Decree no. 95-1939 of 9 October 1995 on the Regulation of Fisheries provides specific regulations for the operation of fishing activities, including the types of gear that can be used, the fishing zones, and the seasons when fishing is permitted. It also includes provisions for monitoring and enforcement. The decree regulates the use of fishing gear, which is central to the issue of ghost gear. By specifying permissible gear types and usage conditions, the decree indirectly addresses the potential for gear loss. However, it could be strengthened by explicitly including measures for gear marking and retrieval.

The Law no. 2009-49 of 20 July 2009 on the Protection of the Marine and Coastal Areas focuses on the protection of marine and coastal environments in Tunisia. This law provides a broader environmental protection framework within which ghost gear management could be situated. The law’s emphasis on pollution prevention is particularly relevant, as ghost gear constitutes a form of marine pollution. Integrating specific measures against ghost gear within this law could enhance its effectiveness in protecting marine environments.

The National Strategy for the Management of Marine and Coastal Protected Areas (2010) includes objectives related to the sustainable use of marine resources and the reduction of human impacts on marine biodiversity. The strategy provides a framework for protecting marine areas that are particularly vulnerable to ghost gear. Implementing specific actions within these protected areas, such as regular monitoring and gear retrieval programs, could significantly reduce the impact of ghost gear.

Tunisia’s post-2020 National Environmental Protection Strategy likely emphasizes the protection of marine ecosystems, reduction of pollution, and sustainable resource management. Ghost gear, which poses a significant threat to marine life and habitats, should be explicitly identified as a form of marine pollution within this strategy. It is recommended to develop and implement national guidelines for sustainable fishing practices, including ghost gear management, as part of the post-2020 strategy.

Various ministerial orders and circulars issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, Water Resources, and Fisheries provide detailed guidelines for the implementation of fisheries laws. These may include instructions on gear marking, reporting lost gear, and other best practices for minimizing gear loss. These orders and circulars can be critical tools for enforcing regulations related to ghost gear. For instance, mandating the use of gear marking systems and establishing procedures for reporting lost gear can help track and recover ghost gear more effectively.

6.2. Integration into Fisheries Management

The existing national legislation provides a strong foundation for managing fisheries and protecting the marine environment in Tunisia. However, the issue of ghost gear is not explicitly addressed in most of these laws and regulations. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity: there is a clear need to update and expand the legal framework to include specific provisions for ghost gear management.

This legislation should be consistent with Tunisia’s international obligations under agreements such as the UNCLOS and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). For example, fines or penalties for non-compliance could be modeled after those used in other regions to enforce similar regulations. Ghost gear management will be integrated into existing fisheries management plans and marine conservation strategies. This approach is recommended by the FAO and is consistent with the ecosystem-based management practices advocated by international environmental law.

Article 7: Monitoring and Evaluation

7.1. Monitoring Framework

A monitoring and evaluation framework will be established to assess the effectiveness of this Code of Conduct. This will include regular data collection and reporting, with reference to international standards such as those set by the GGGI and the FAO.

7.2. Continuous Improvement

The Code will be reviewed and updated regularly to incorporate new best practices and technological advancements. This process will ensure the Code remains relevant and effective, in line with the adaptive management principles endorsed by the FAO.

Article 8: Roles and Responsibilities

8.1. Government Agencies

The government is responsible for enacting and enforcing regulations that align with the Code of Conduct.

The polluter pays principle (PPP) is a fundamental concept in environmental policy. It ensures that those who cause pollution bear the costs associated with it, including the expenses related to prevention, control, and remediation. The EU has adopted the polluter pays principle as part of its Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD), which requires member states to achieve good environmental status of their marine waters, including addressing the issue of ghost gear. Member states, such as France and the Netherlands, have implemented policies where fishers are responsible for the costs of ghost gear retrieval and disposal. These countries also require fishers to contribute to funds or pay for services that handle the collection and recycling of ghost gear.

The government should take various measures to encourage initiatives to preserve the cultural heritage of fishing communities, including promoting traditional fishing practices such as charfia fishing in the Kerkennah Islands, drift nets (Jebbia), hand lines and long lines (Senhadja), traps and pots (gargoulettes), and beach seines (charfia nets). These programs often involve collaborations with cultural organizations and local communities. The government should recognize and sometimes provides awards or special statuses to communities and individuals who excel in using and preserving traditional fishing gear.

Government authorities must work with the local cooperation of artisanal fishermen, a new initiative promoting local cooperation among artisanal fishermen, to develop and enforce policies and regulations aimed at preventing ghost gear loss and improving gear retrieval and disposal practices. Sustainability and cooperation are becoming key proposals for Tunisian local authorities aiming to boost employment and preserve the environment.

Government agencies must provide logistical and financial support for ghost gear retrieval and disposal. This includes establishing designated retrieval zones, organizing and funding retrieval operations, and setting up facilities for the environmentally responsible disposal or recycling of retrieved gear.

Governments should work with international organizations, including FAO, GGGI, and UNEP, in parallel with their work with RFMOs, to align national regulations with international best practices and to secure technical and financial assistance for ghost gear management. This collaboration is crucial for addressing transboundary issues related to ghost gear, ensuring that efforts in the Gulf of Gabès are part of a broader, international strategy.

Government agencies should lead educational campaigns and training programs aimed at raising awareness about the impacts of ghost gear and the importance of responsible fishing practices. These campaigns should be tailored to the local context, but also draw on successful models from other regions. The Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) has set up a robust technical cooperation program to help countries build their capacity. As a first step, in 2024, the Faculty of Sciences of Sfax and the Tunisian Taxonomy Association, ATUTAX, have joined the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) in order to coordinate with international bodies in the fight against ghost fishing and to help implement international legislation at the national level in Tunisia.

Government agencies should support research programs that localize ghost gear and study their impacts on marine ecosystems to explore innovative solutions to mitigate these impacts. They should encourage startups and industries to design special boats equipped with screen and mesh filters to collect floating waste contaminating Tunisian coasts and support interactions between industries and scientists to propose innovative waste reduction and biodegradable, recyclable, non-toxic materials.

8.2. Fishers

Fishers play a critical role in the prevention, reporting, and retrieval of ghost gear, given their direct involvement in fishing activities.

Fishers are responsible for marking all fishing gear with unique identifiers, such as tags or embedded chips, to facilitate traceability [30]. This practice ensures that any lost or discarded gear can be easily identified and returned to its owner, reducing the incidence of ghost gear. Marking requirements should align with international guidelines, such as those recommended by the FAO and GGGI.

Fishers must report any lost or abandoned gear immediately to the relevant authorities using a standardized reporting platform. This not only aids in the swift retrieval of the gear but also contributes to the overall data collection efforts needed to monitor the scope of the ghost gear problem. Reporting systems could be modeled on successful examples like Norway’s ghost gear reporting system where the eOceans app allows fishers to log lost gear, and anyone who finds it can report it as well [40].

Fishers are encouraged to participate actively in ghost gear retrieval programs. This might involve organized “clean-up” days where fishers are incentivized to retrieve ghost gear, or participation in initiatives like the “Fishing for Litter” program, where they can bring collected ghost gear back to port for proper disposal. The Life MedTurtles project has already installed five ghost net collection containers in the five major ports of the Gulf of Gabès, which fishermen can use to collect their damaged nets.

Fishers must adopt responsible fishing practices to minimize gear loss. This includes regular maintenance checks, proper storage of gear when not in use, and the use of gear suited to the local marine environment. Training on best practices will be provided to ensure all fishers are equipped with the knowledge to reduce gear loss. Fishers, for instance, must ensure proper gear maintenance and report lost gear, while government agencies should enforce regulations and provide support for retrieval efforts. This principle is in line with the polluter pays principle under international environmental law, which holds that those responsible for pollution should bear the costs of managing it.

8.3. Manufacturers

Manufacturers of fishing gear have a significant role in reducing the environmental impact of their products through innovation and sustainability practices.

Manufacturers must prioritize the development and production of fishing gear made from biodegradable materials or other environmentally friendly alternatives. These materials should degrade over time, reducing the long-term impact of lost gear on the marine environment. The development of such gear should align with successful international initiatives, such as those promoted by Blue Ocean Gear, which has developed innovative “smart” buoys that help track fishing gear in real-time, reducing the chances of gear becoming ghost gear. They are also exploring the integration of biodegradable materials into their product lines.

Manufacturers should ensure that all fishing gear is embedded with traceable technology, such as RFID tags or QR codes, at the point of production. This will facilitate the identification and retrieval of lost gear, aligning with international best practices in traceability.

Manufacturers should participate in extended producer responsibility (EPR) programs, which hold them accountable for the lifecycle of their products, including end-of-life disposal. This can involve contributing to or establishing recycling and disposal programs that are accessible to fishers, thus reducing the accumulation of ghost gear.

Manufacturers should implement programs to buy back old or damaged gear from fishers, encouraging the use of new, more sustainable gear and offer discounts or subsidies on eco-friendly gear to incentivize fishers to transition to more sustainable options.

Manufacturers should adopt and promote voluntary industry standards for sustainable gear design and production to ensure that all manufactured gear complies with national and international regulations regarding environmental impact and sustainability

Manufacturers should invest in research and development (R&D) to explore innovative solutions for reducing the environmental impact of fishing gear and participate in pilot projects aimed at testing new materials and incorporating technologies such as RFID tags (radio frequency identification tags that use radio waves to communicate between a tag and a reader), GPS trackers, and other smart technologies to monitor and retrieve lost gear.

Manufacturers should contribute to public awareness campaigns and provide training to fishers on the proper use, maintenance, and disposal of their products. This can be part of broader corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives that align with international environmental standards.

8.4. Users

The broader community, including consumers, NGOs, and local stakeholders, also has a role to play in supporting the objectives of the Code. This includes raising awareness about the environmental impact of ghost gear and supporting initiatives that promote sustainable fishing practices.

Local communities should be encouraged to participate in coastal clean-up operations and other initiatives aimed at reducing marine litter, including ghost gear. These efforts can be coordinated with local authorities and NGOs, including contributing to collecting and measuring gear waste from beaches or underwater and encouraging the utilization of mobile apps, web portals, and public databases to provide tools for gathering and sharing comparable data on marine litter. This helps build a harmonized database of marine litter and raises citizens’ awareness of the issue.

Divers can participate in the ghost gear management strategy along Tunisia’s coastline by reporting ghost gear sightings so professionals can remove the ghost gear, contributing to better waste and fisheries management. Notifying authorities about ghost gear sightings during recreational diving helps professionals remove the debris and supports the enhancement of waste and fisheries management programs.

Consumers can support ghost gear management by choosing to purchase seafood from sources that adhere to responsible fishing practices. Supporting certifications and labels that guarantee sustainable fishing can drive demand for products that align with the principles of the Code.

Users should be encouraged to report sightings of ghost gear or other marine litter to the relevant authorities. This can be facilitated through community-based monitoring programs, media platforms (such as the TunSea Facebook group) or mobile apps such as the Ghost Gear Reporter app developed in partnership with the (GGGI), that allow for easy reporting and tracking of ghost gear incidents.

Article 9: Alignment with International Standards

9.1. International Policy Compliance

This Code shall be aligned with the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) guidelines, and other relevant international agreements. For instance, the Code’s emphasis on gear marking and retrieval aligns with the FAO’s guidelines on reducing marine litter from fishing operations.

All actions under this Code must comply with relevant international laws and agreements, such as UNCLOS and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) guidelines on marine pollution. Regular reviews will ensure the Code remains aligned with evolving international standards and practices.

9.2. Review and Adaptation

The Code will be regularly reviewed to ensure continued alignment with international standards and best practices. This will include consultations with international bodies and periodic updates to incorporate new developments in global ghost gear management.

Article 10: Final Provisions

10.1. Implementation

The effective date of this Code will be determined upon final approval by the relevant authorities. Its provisions will be implemented by all stakeholders in the Gulf of Gabès, with a phased approach to ensure smooth adoption.

10.2. Enforcement

Enforcement mechanisms for this Code will be defined by the government in collaboration with key stakeholders, ensuring accountability and compliance. This may include penalties for non-compliance and incentives for adherence, consistent with international best practices.

4. Discussion

The issue of ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès represents a critical environmental challenge that threatens marine biodiversity, local fisheries, and the overall health of the ecosystem. This study, grounded in the findings of the Life MedTurtles and MedBycatch projects and supported by international legal frameworks, highlights the urgent need for a comprehensive and enforceable code of conduct to manage ghost gear in this vulnerable region.

4.1. Impact on Marine Life and Biodiversity

Ghost gear is one of the most insidious forms of marine pollution, causing extensive harm to marine species, including endangered turtles and other non-target species. The entanglement and ingestion of ghost gear by marine animals lead to injuries, fatalities, and disruptions in reproductive cycles. Our findings align with global research, emphasizing that immediate action is required to mitigate these impacts. The proposed code of conduct outlines clear guidelines and responsibilities for stakeholders to prevent gear loss and ensure the timely retrieval of any lost gear.

4.2. Socio-Economic Implications for Local Communities

The socio-economic context of the Gulf of Gabès is heavily intertwined with the fishing industry, which provides livelihoods for thousands of local fishers. The presence of ghost gear not only reduces fish stocks but also increases operational costs for fishers due to damaged equipment and lost catches. Implementing the polluter pays principle (PPP) within the framework of this code can help to distribute the financial burden of ghost gear management more equitably, ensuring that those responsible for gear loss contribute to the costs of retrieval and disposal.

4.3. International Legal and Policy Context

The proposed code of conduct is firmly grounded in international legal principles, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. By aligning with these frameworks, the code ensures that local actions in the Gulf of Gabès are in harmony with broader international efforts to combat marine pollution and promote sustainable fishing practices. The integration of the polluter pays principle within this context is particularly significant, as it reflects a growing global consensus on the need to hold polluters accountable.

4.4. Role of Stakeholders

The successful implementation of the proposed code depends on the active involvement and collaboration of multiple stakeholders, including local fishers, government authorities, manufacturers of fishing gear, and international organizations. Each stakeholder group has a distinct role to play:

- Government authorities must enforce regulations, facilitate gear retrieval operations, and ensure that the polluter pays principle is applied.

- Fishers are crucial in reporting lost gear and adhering to best practices to prevent gear loss.

- Manufacturers have a responsibility to innovate and produce more sustainable, biodegradable fishing gear, thereby reducing the long-term impact of ghost gear.

- International organizations can provide technical support, funding, and a platform for sharing best practices across regions.

4.5. Feasibility and Implementation Challenges

While the proposed code of conduct presents a robust framework, its implementation may face challenges due to socio-economic and political factors in Tunisia. Effective enforcement, continuous monitoring, and stakeholder engagement are critical to overcoming these challenges. The role of the government as the primary driver of this initiative cannot be overstated. By prioritizing ghost gear management within national environmental policies and securing international cooperation, Tunisia can lead by example in the Mediterranean region.

4.6. Future Directions

Further research is needed to monitor the long-term effectiveness of the code of conduct and to refine its guidelines based on emerging data and technological advancements. Additionally, expanding public awareness campaigns and providing incentives for compliance will be essential in fostering a culture of responsibility among all stakeholders.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the importance of adopting a comprehensive, legally grounded code of conduct to address the issue of ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès. By drawing on international legal frameworks and engaging all relevant stakeholders, the proposed code offers a practical solution to a complex environmental problem. The successful implementation of this code will not only protect marine biodiversity but also secure the livelihoods of local communities, contributing to the sustainable development of the region.

As part of this study, we have utilized AI-powered tools for data review and collection. AI-powered literature search tools were employed to gather relevant academic papers, reports, and policies related to ghost gear and marine conservation. This enabled us to comprehensively review existing research and manage large datasets effectively. We confirm that we have not used AI to generate substantive content for this paper; all analyses, conclusions, and key arguments are entirely the work of the authors.

Moving forward, we recommend holding meetings with key stakeholders, including fishers, community leaders, NGOs, and government officials to discuss the draft code of conduct and gather feedback. We encourage that the basic elements of this code of conduct, as presented here, be proactively considered and applied by conservation organizations and practitioners in Tunisia. We also emphasize the importance of best-practice education for conservationists. To conclude, we reiterate our call for the development of a comprehensive and widely accepted code of conduct to facilitate the process of sustainable fisheries off Tunisia’s coasts, and to develop processes and actions to support a truly sustainable approach to marine conservation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16188003/s1: Video S1: Retrieval operations of ghost gear from Chebba coasts off the Gulf of Gabès as part of Life MedTurtles project. Video S2: Retrieval operations of ghost gear from Djerba Island and Zarzis off Gulf of Gabès as part of Life MedTurtles project.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.B., M.N.B. and I.J.; Data curation, W.B., H.M., M.N.B., S.E., B.S. and I.J.; Formal analysis, W.B.; Funding acquisition, I.J.; Investigation, W.B., H.M. and I.J.; Methodology, W.B., H.M., M.N.B. and I.J.; Project administration, W.B., H.M. and I.J.; Resources, W.B., H.M., M.N.B., S.E., B.S. and I.J.; Supervision, M.N.B. and I.J.; Validation, W.B. and I.J.; Visualization, W.B. and I.J.; Writing—original draft, W.B.; Writing—review and editing, W.B., M.N.B. and I.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the scientific research project “LIFE MEDTURTLES”, co-funded by the European Union and coordinated across Tunisia by the Faculty of Sciences of Sfax (FSS), LIFE financial instrument of the European Union: LIFE18 NAT/IT/000103; and the MedBycatch project funded by the MAVA Foundation under its initiative to support biodiversity conservation and sustainable fishing practices in the Mediterranean.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the approval of the biological sciences commission of the Sfax Faculty of Sciences.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by both the scientific research project “LIFE MEDTURTLES”, funded by the European Union and coordinated across Tunisia by the Faculty of Sciences of Sfax (FSS), and the MedBycatch project funded by the MAVA foundation. The authors would like to thank all participating fishermen and investigators. We would also like to thank the Agency for the Protection and Development of the Littoral (APAL) and the Tipaza Djerba Club, which took part in the Life MedTurtles project’s mission to recover ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès. The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT, an AI language model developed by OpenAI, for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript. ChatGPT was used to help with text structuring, refining language clarity, and proofreading. Its use significantly contributed to improving the efficiency of the writing process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Richardson, K.; Asmutis-Silvia, R.; Drinkwin, J.; Gilardi, K.V.; Giskes, I.; Jones, G.; Barco, S. Building evidence around ghost gear: Global trends and analysis for sustainable solutions at scale. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suka, R.; Huntington, B.; Morioka, J.; O’Brien, K.; Acoba, T. Successful application of a novel technique to quantify negative impacts of derelict fishing nets on Northwestern Hawaiian Island reefs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 157, 111–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaouar, H.; Boussellaa, W.; Jribi, I. Ghost Gears in the Gulf of Gabès: Alarming Situation and Sustainable Solution Perspectives. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Vince, J.; Wilcox, C. Global estimates of fishing gear lost to the ocean each year. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq0135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Ghost Gear Initiative. GGGI 2022 Annual Report; Global Ghost Gear Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 1–31. Available online: https://www.ghostgear.org/annual-report-2022 (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Van der Hoop, J.; Moore, M.; Fahlman, A.; Bocconcelli, A.; Gearge, C. Behavioral Impact of Disentanglement of a Right Whale under Sedation and the Energetic Costs of Entanglement. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2013, 30, 282–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orós, J.; Montesdeoca, N.; Camacho, M.; Arencibia, A.; Calabuig, P. Causes of Stranding and Mortality, and Final Disposition of Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta) Admitted to a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Gran Canaria Island, Spain (1998–2014): A Long-Term Retrospective Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfadyen, G.; Huntington, T.; Cappell, R. Abandoned, Lost or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, C.; Mallos, N.J.; Leonard, G.H.; Rodriguez, A.; Hardesty, B.D. Using Expert Elicitation to Estimate the Impacts of Plastic Pollution on Marine Wildlife. Mar. Policy 2016, 65, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, M.; Hudgins, J.; Sweet, M.A. Review of Ghost Gear Entanglement amongst Marine Mammals, Reptiles and Elasmobranchs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 111, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiros, J.P.; Raykov, V.S. Lethal lesions and amputation caused by plastic debris and fishing gear on theloggerhead turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758). Three case reports from Terceira Island, Azores (NEAtlantic). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 86, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, E.M.; Botterell, Z.L.R.; Broderick, A.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Lindeque, P.K.; Nuno, A.; Godley, B.J. A Global Review of Marine Turtle Entanglement in Anthropogenic Debris: A Baseline for Further Action. Endang. Species Res. 2017, 34, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, K.; Galloway, T.; Godley, B. Global Review of Shark and Ray Entanglement in Anthropogenic Marine Debris. Endanger. Species Res. 2019, 39, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Protecting Whales & Dolphins Initiative. Using Acoustic Sonar Technology to Locate and Tackle Ghost Gear. Available online: https://wwfwhales.org/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Widjaja, S.L.; Tony, W.; Hassan, V.A.; Hennie, B.; Per, E. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing and Associated Drivers. Available online: https://www.oceanpanel.org/bluepapers/illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-fishing-and-associated-drivers (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- FAO. Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- GGGI. Global Ghost Gear Initiative Annual Report; Global Ghost Gear Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Ghost Gear Is the Deadliest Form of Marine Plastic Debris. Stop Ghost Gear: The Most Deadly Form of Marine Plastic Debris. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldwildlife.org (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines on the Marking of Fishing Gear. Directives Volontaires sur le Marquage des Engins de Pêche. Directrices Voluntarias sobre el Marcado de las Artes de Pesca; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bradai, M.N.; Saidi, B.; Bouaïn, A.; Guelorget, O.; Capapé, C. The Gulf of Gabès (Southern Tunisia, Central Mediterranean): A Nursery Area for Sandbar Shark, Carcharhinus plumbeus (Nardo, 1827) (Chondrichthyes: Carcharhinidae). Ann. Ser. Historia Nat. 2005, 15, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jribi, I.; Bradai, M.N.; Bouain, A. Loggerhead Turtle Nesting Activity in Kuriat Islands (Tunisia): Assessment of Nine Years Monitoring. Mar. Turtle Newsl. 2006, 112, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bradai, M.N.; Saidi, B.; Enajjar, S. Overview on Mediterranean Shark’s Fisheries: Impact on the Biodiversity. In Marine Ecology: Biotic and Abiotic Interactions; Türkoğlu, M., Önal, U., Ismen, A., Eds.; INTEC: London, UK, 2018; pp. 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Saidi, B.; Enajjar, S.; Karaa, S.; Echwikhi, K.; Jribi, I.; Bradai, M.N. Shark Pelagic Longline Fishery in the Gulf of Gabes: Inter-Decadal Inspection Reveals Management Needs. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2019, 20, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enajjar, S.; Saidi, B.; Bradai, M.N. Elasmobranchs in Tunisia: Status, Ecology, and Biology. In Sharks Past, Present and Future; Bradai, M.N., Saidi, B., Enajjar, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Anonyme. Annuaire des Statistiques des Pêches et de l’Aquaculture en Tunisie (Année 2020); Direction Générale de la Pêche et de l’Aquaculture: Tunis, Tunisia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Louhichi, M.; Girard, A.; Jribi, I. Fishermen Interviews: A Cost-Effective Tool for Evaluating the Impact of Fisheries on Vulnerable Sea Turtles in Tunisia and Identifying Levers of Mitigation. Animals 2023, 13, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMO. IMO Action Plan on Reducing Marine Litter from Ships. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/20marinelitteractionmecp73.aspx#:~:text=The%20action%20plan%20supports%20IMOsentangled%20in%20propellers%20and%20rudders (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- OECD. Towards G7 Action to Combat Ghost Fishing Gear; Policy Perspectives. OECD Environment Policy Paper, No. 25; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA. Marine Debris Program. Accomplishments Report; NOAA Office of Response and Restoration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- GGGI. Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear: June 2021 Update; Global Ghost Gear Initiative: Washington, DS, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.ghostgear.org (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution 76/71. Sustainable Fisheries, Including through the 1995 Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, and Related Instruments; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marine Stewardship Council (MSC). Preventing Lost and Abandoned Fishing Gear (Ghost Fishing). Available online: https://www.msc.org/what-we-are-doing/preventing-lost-gear-and-ghost-fishing (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Drinkwin, J. Reporting and Retrieval of Lost Fishing Gear: Recommendations for Developing an Effective Program; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.J.; Brillant, S.; Walker, T.R.; Bailey, M.; Callaghan, C. A Ghostly Issue: Managing Abandoned, Lost and Discarded Lobster Fishing Gear in the Bay of Fundy in Eastern Canada. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 181, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczenski, B.; Vargas Poulsen, C.; Gilman, E.L.; Musyl, M.; Geyer, R.; Wilson, J. Plastic Gear Loss Estimates from Remote Observation of Industrial Fishing Activity. Fish. Fish. 2022, 23, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Plastic Debris in the Ocean. In UNEP Year Book 2014: Emerging Issues Update; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- GGGI. Global Ghost Gear Initiative Annual Report; Global Ghost Gear Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Greenpeace. Annual Report for Stichting Greenpeace Council; Greenpeace: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; 31p. [Google Scholar]

- Global Sea Food Alliance. From Reporting Apps to Floating Traps: How Technology Tackles Ghost Fishing. Responsible Seafood Advocat; Global Seafood Alliance: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 2022; 7p, Available online: https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/from-reporting-apps-to-floating-traps-how-technology-tackles-ghost-fishing/?headlessPrinT (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Ben Abdallah, A.; Ben Mustapha, K. Marine Biodiversity in the Gulf of Gabès (Tunisia): Impact of Human Activities and Management Strategies. Cah. Biol. Mar. 2011, 52, 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Lahbib, Y.; Benamer, I. Marine Litter in the Gulf of Gabès: Distribution, Types, and Effects on the Environment. J. Coast. Conserv. 2018, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP/MAP & Plan Bleu. Economic and Social Analysis of the Uses of the Coastal and Marine Waters of Tunisia: The Case of the Gulf of Gabès; UNEP/MAP & Plan Bleu: Athens, Greece, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).