Heritage Regeneration Models for Traditional Courtyard Houses in a Northern Chinese City (Jinan) in the Context of Urban Renewal

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Review

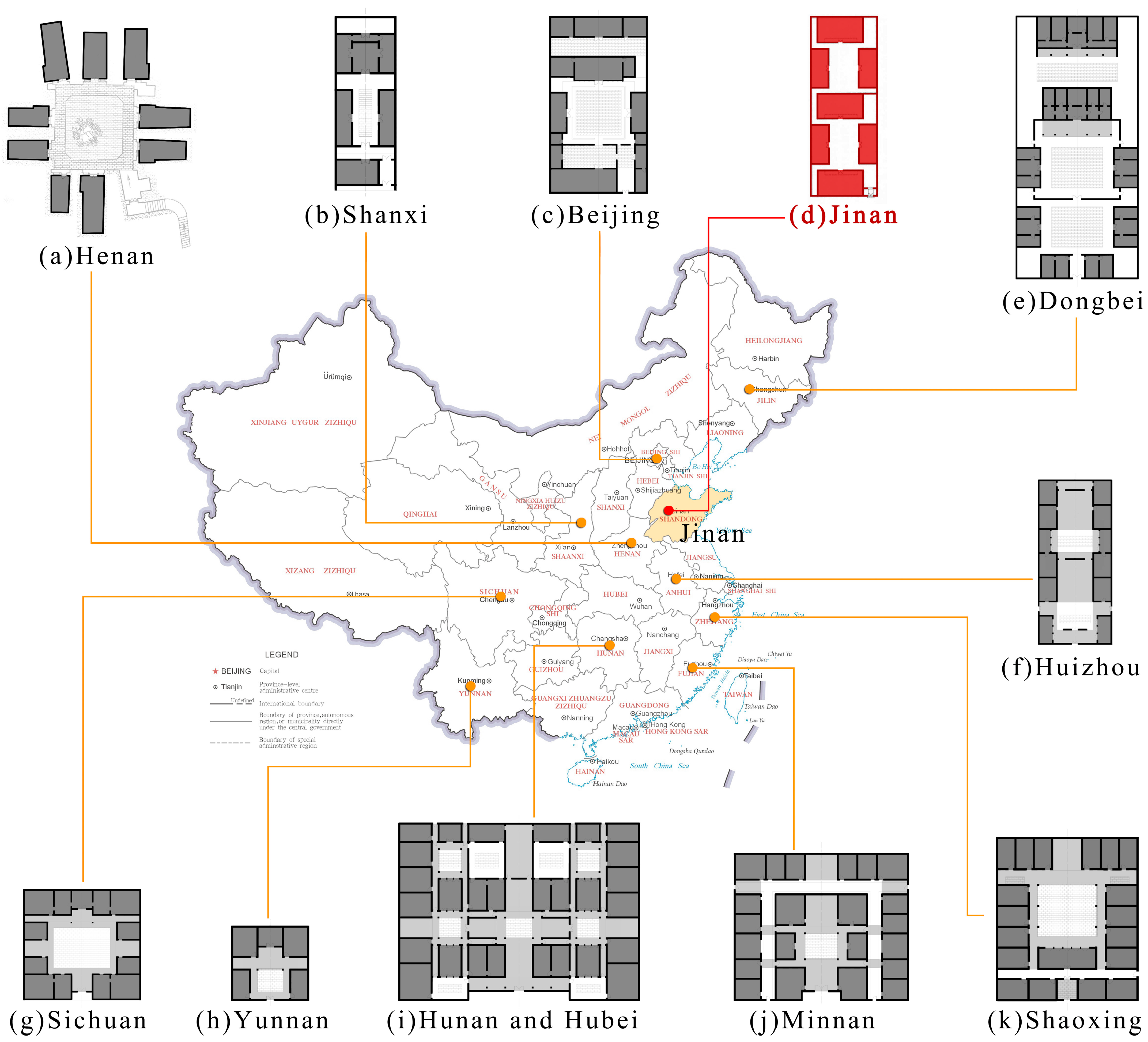

1.2. Research Background in China

1.3. Research Aim

2. Materials and Methodology

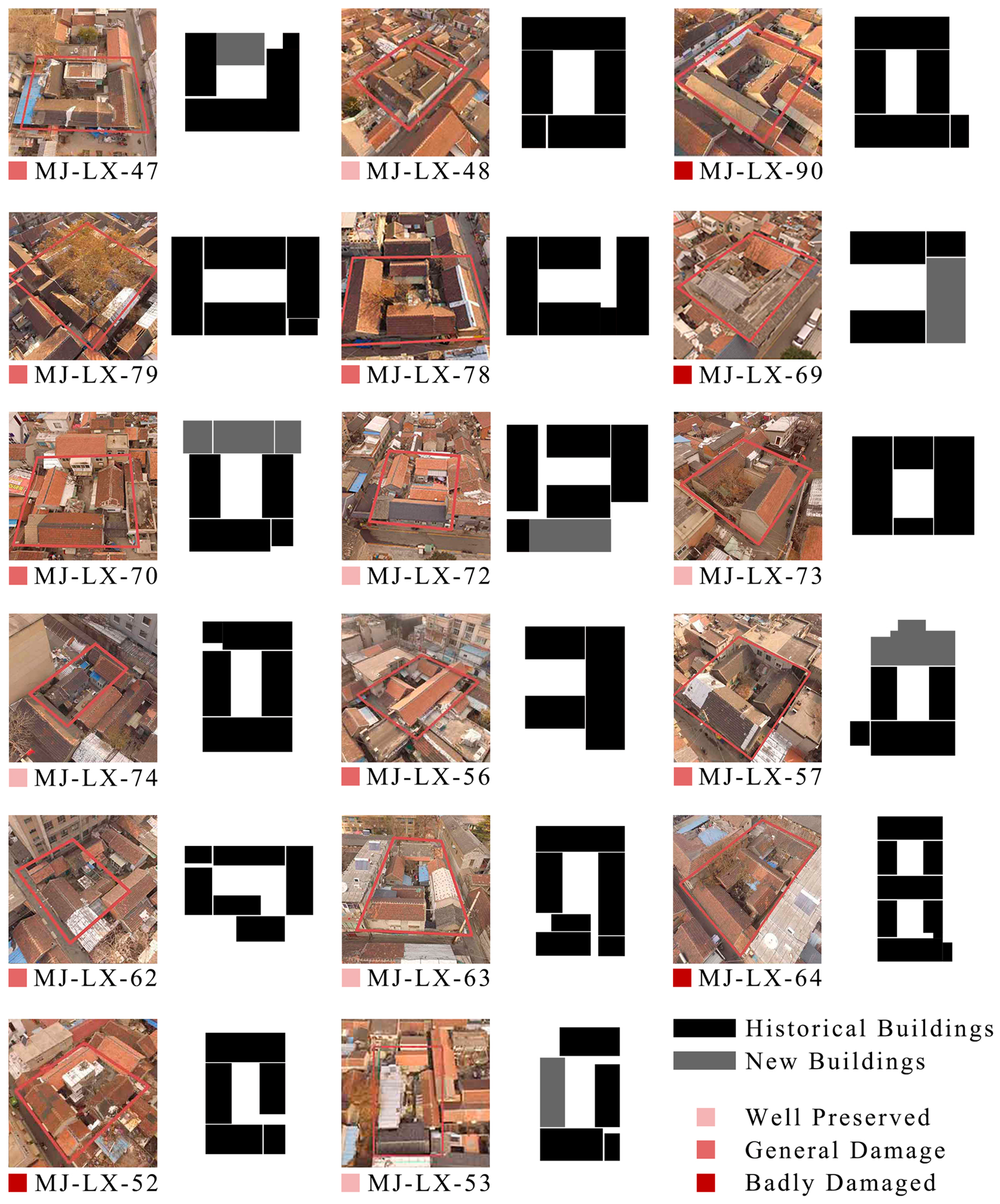

2.1. Case Selection

- (1)

- No. 55 Qiming Street retains the typical south-facing courtyard layout characteristic of traditional Jinan courtyard houses, making it an exemplary model of this architectural style. It also reflects the mixed characteristics of Chinese and Western architectural cultures in modern times [70].

- (2)

- The existing buildings include the main gate, the main room, the east wing room, and the west wing room, which are representative of traditional masonry, woodwork, and other construction techniques and decorative art features.

- (3)

- The north courtyard of No. 55 Qiming Street is a “compound” inhabited by several families and tenants, while the south building is inhabited by the original owner of the house. The coexistence of homeowners and tenants exemplifies a common problem in the use of cohousing.

- (4)

- The property right of No. 55, Qiming Street is clear, which facilitates the implementation of renewal and reconstruction.

- (5)

- Positioned near Huajiajing Spring, one of Jinan’s renowned 72 springs, the spatial setting of No. 55 Qiming Street exemplifies a typical environment within the city, enhancing its historical and cultural significance.

2.2. Methodology

- (1)

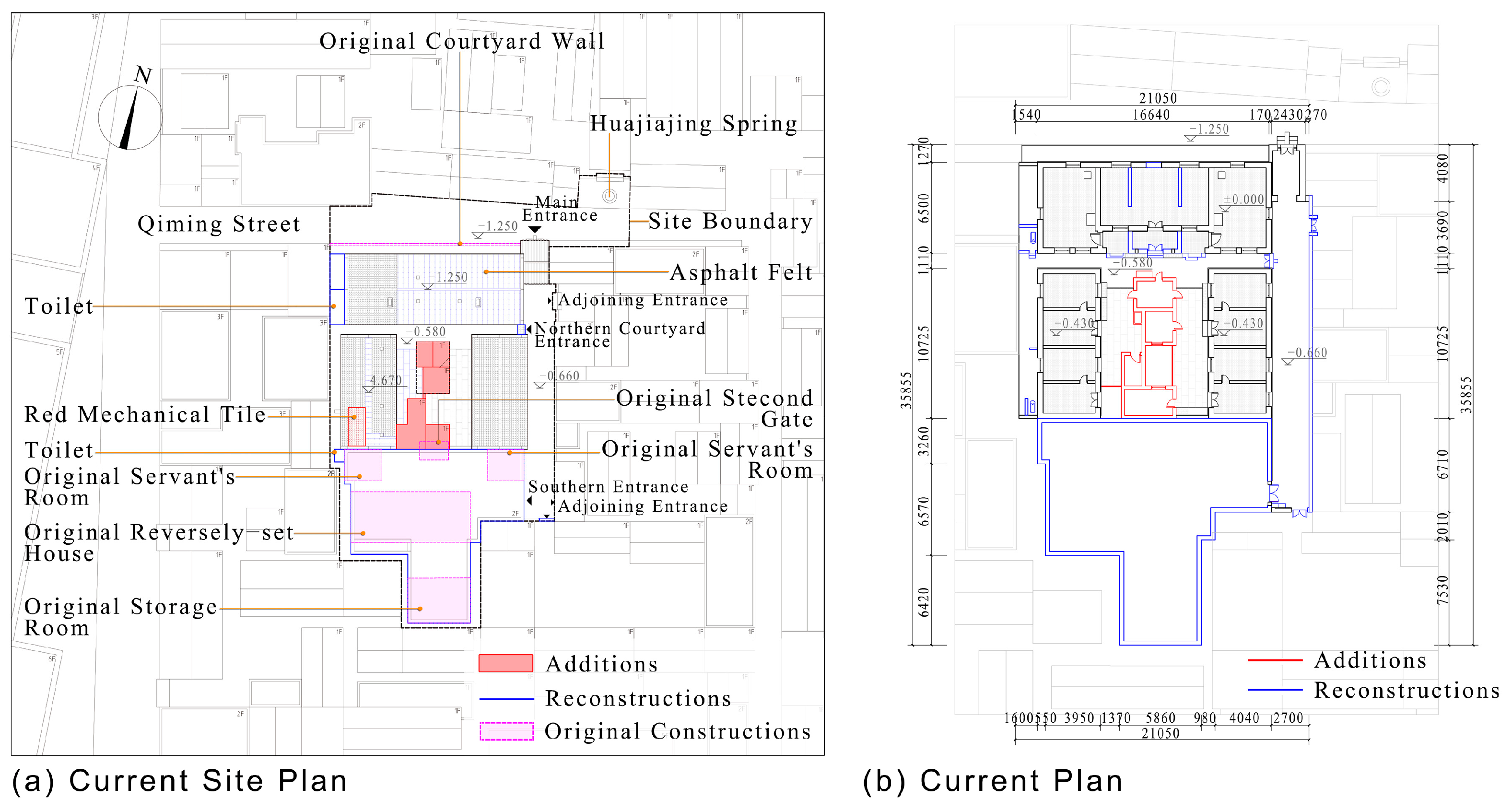

- Historical Study and Field Investigation: The historical research mainly involves the investigation of historical maps, satellite maps, and historical data, examining the development of the Jiangjunmiao Historic District and summarizing the architectural characteristics of Jinan’s courtyard houses. The field investigation includes the research and mapping of the architectural heritage, aerial photography by drones, and evaluation of the state of integrity of the architectural heritage, etc. Based on the historical research and current situation investigation, the fragmentary layers of the buildings in different historical stages can be revealed, providing the data basis for the conservation and reuse practice [71].

- (2)

- Participatory Analysis: Firstly, through the interview with the present owner of the south building of No. 55 Qiming Street, we examined the original state of the building and its later additions and alterations. Secondly, through oral interviews with the 13 existing residents of the north courtyard, we learned about the problems in living and the specific demands for modernization. Finally, we negotiate with the tenants and revise the renewal program, so as to explore the balance between value preservation and tenants’ demands.

- (3)

- Policy Analysis: The policy analysis consisted of five components, namely, important issues and goals to be pursued, identification of alternative courses of action, prediction of the outcome of each alternative, identification of criteria to measure the achievement, and indication of the preferred choice of action. The main purpose was to identify effective strategies for addressing heritage regeneration challenges. Through thorough investigation and analysis, the study aimed to propose viable solutions that stakeholders could consider when making decisions. This approach aimed to provide actionable insights into resolving heritage regeneration issues and facilitating informed decision-making among stakeholders [72].

3. Case Presentation

3.1. History

3.2. Original and Current State

4. Discussion

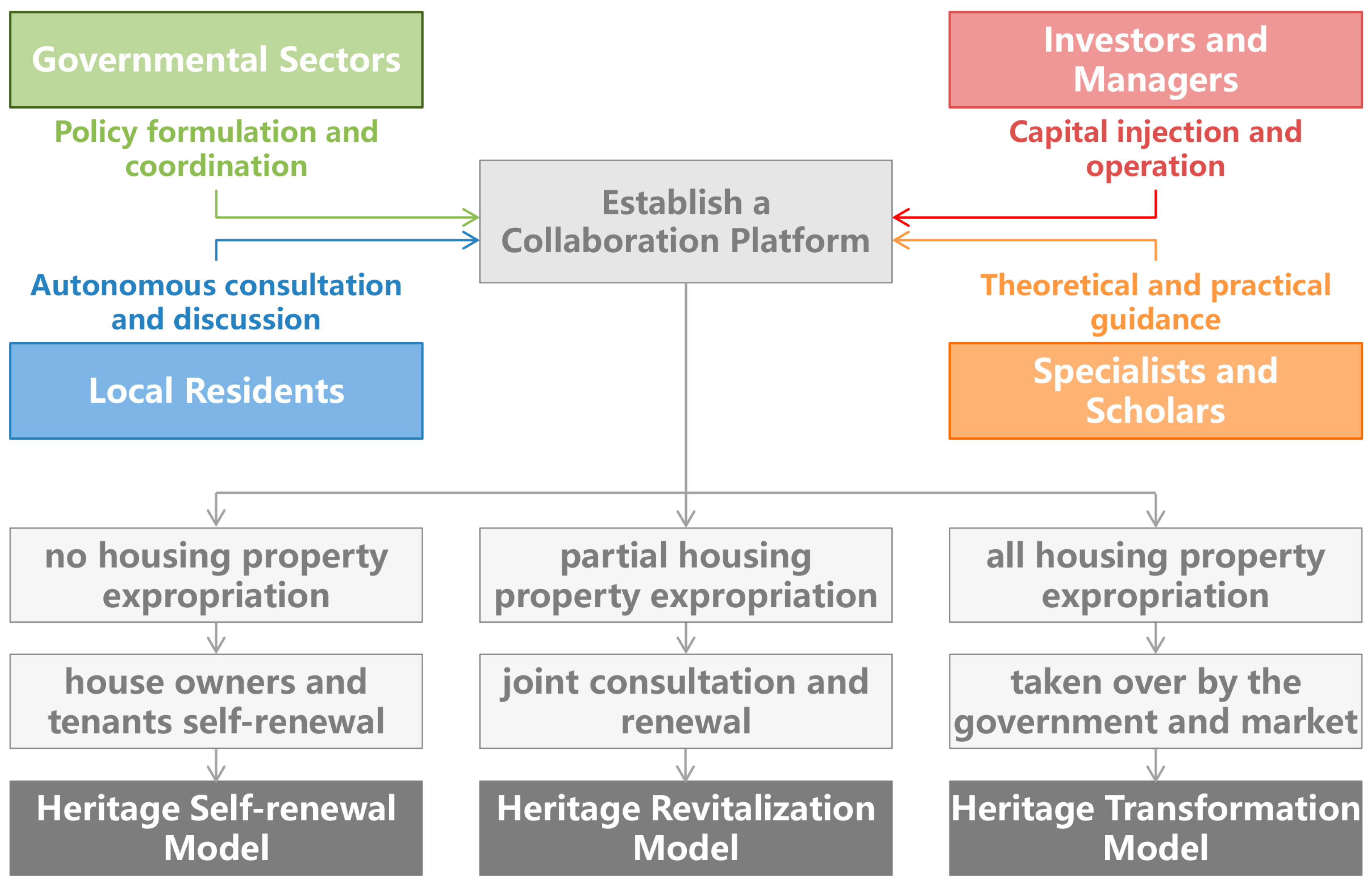

4.1. Interest Relationship of Urban Heritage

- (1)

- (2)

- Communities and minorities, once marginalized, have begun to participate in decision-making in various ways.

- (3)

- The management of heritage conservation has shifted from direct oversight by public sectors to more privatized and entrepreneurial approaches [15].

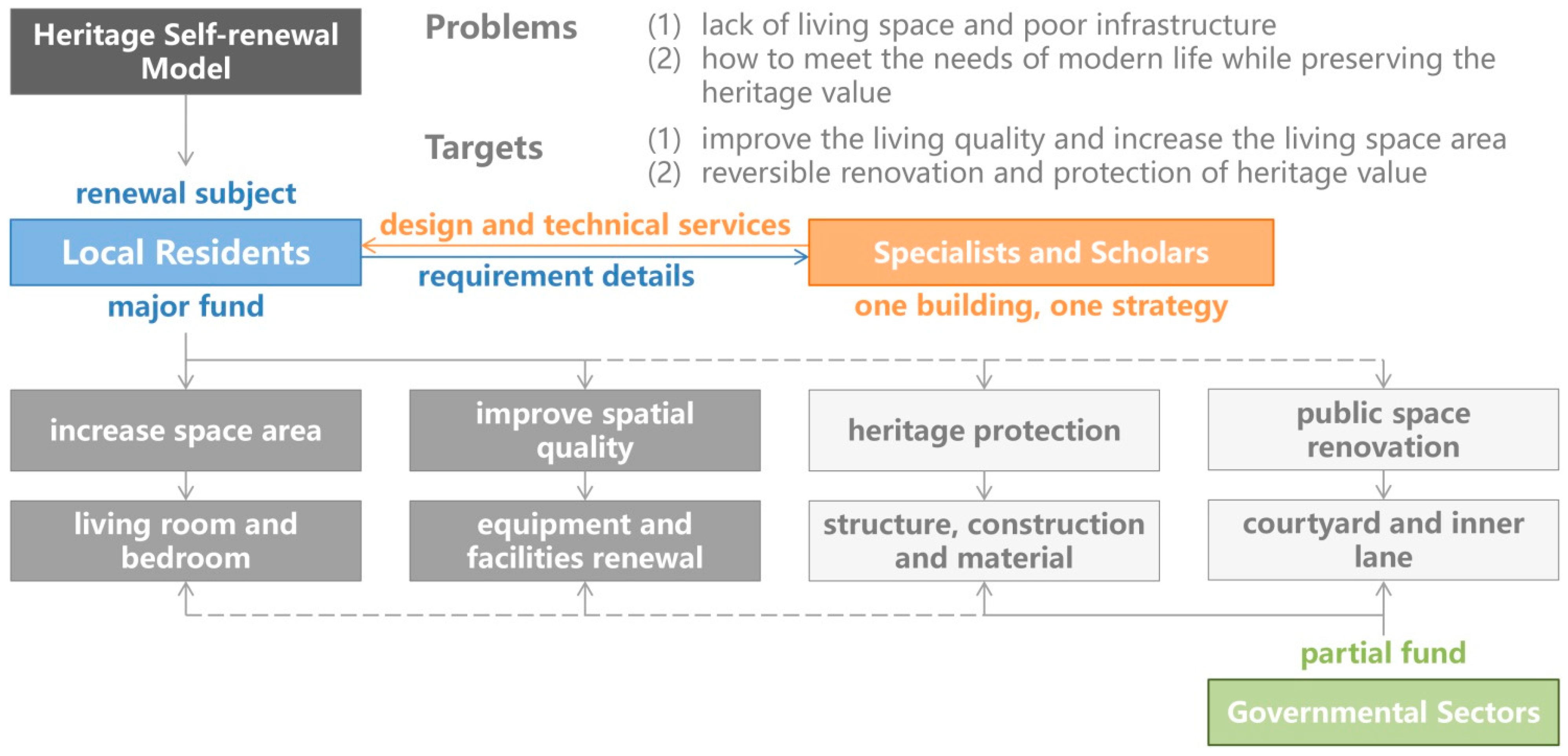

4.2. Heritage Self-Renewal Model

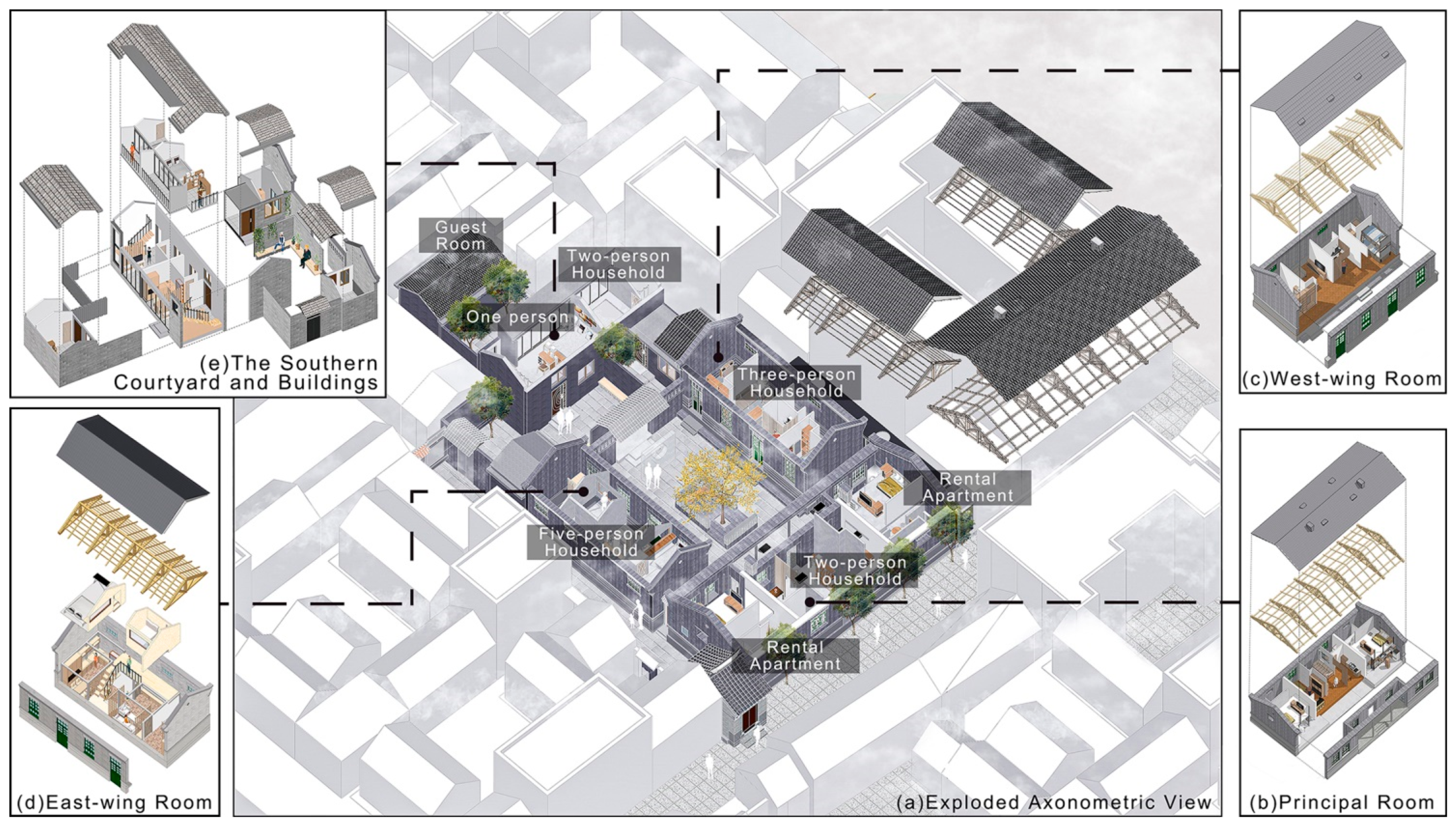

4.3. Heritage Revitalization Model

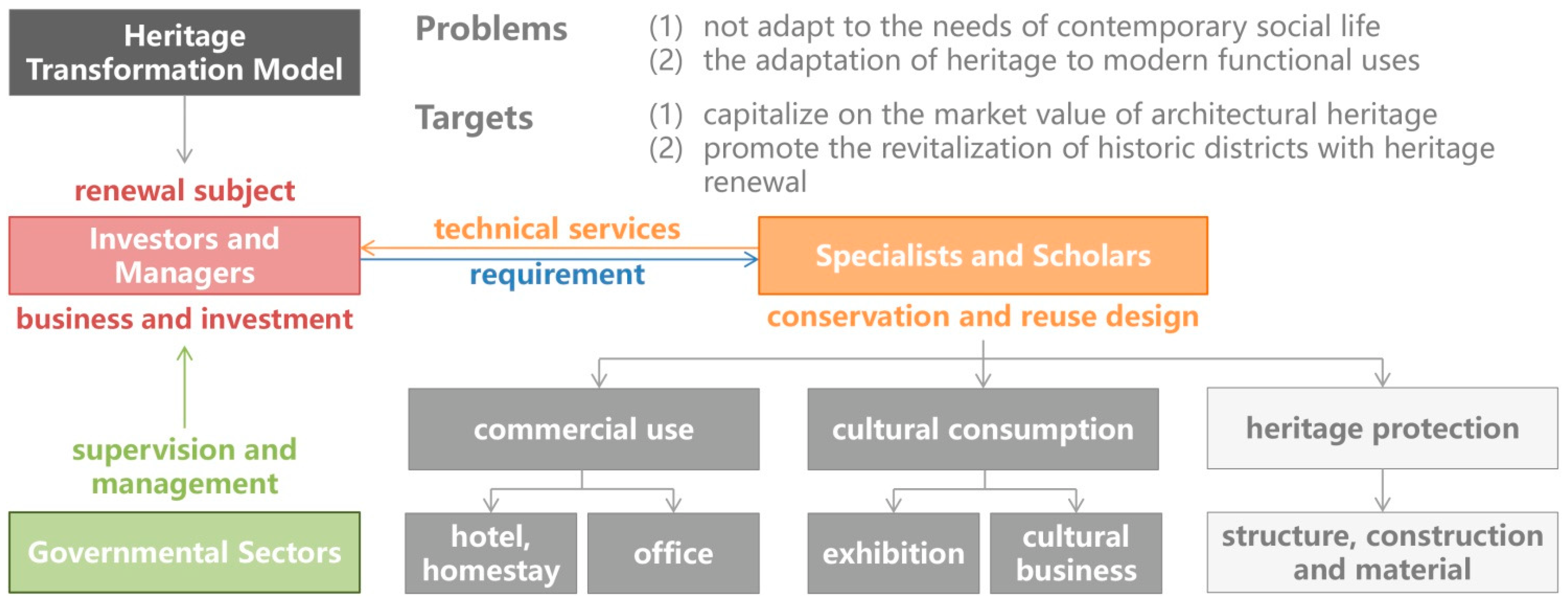

4.4. Heritage Transformation Model

4.5. Comparison of 3 Models

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, S.; Aoki, N. Industrial Heritage Protection in the Period of Inventory Planning. J. Landsc. Res. 2016, 6, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, D.; Chen, H. Termination of Growth Supremacism and Transformation of China’s Urban Planning. City Plan. Rev. 2013, 1, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, X.; Zhuang, S. Promoting Everyday Public Space through Design: A Review of Urban Micro-Regeneration Practices in Shanghai. Archit. J. 2022, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Pan, M. Urban Renewal Practice based on the Concept of Sustainable Development. Archit. Cult. 2023, 2, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, B. Increment Planning, Inventory Planning and Policy Planning. City Plan. Rev. 2013, 2, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Huang, M. Research on Urban Construction Land Regulation Based on Inventory Planning; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; He, C.; Huang, Z. International Experience and Enlightenment of Inventory Planning of Urban Land. Mod. Urban Res. 2017, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, G. Land Readjustment: A Tool for Urban Development. Habitat Int. 1997, 2, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. Land Readjustment, Urban Planning and Urban Sprawl in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Urban Stud. 1999, 13, 2333–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, R. London: Aspects of Change; Centre for Urban Studies and Mac Gibbon and Kee: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Gentrification: Culture and Capital in the Urban Core. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1987, 13, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartek, G. Brownfield Redevelopment. Econ. Dev. J. 2013, 3, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, M.; Lowrie, K.; Miller, K.; Mayer, L. Brownfield Redevelopment as a Smart Growth Option in the United States. Environmentalist 2001, 21, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Analysis on the Concept and Rethinking of Land Use Compatibility under the Background of Built-up Area Planning. Mod. Urban Res. 2018, 5, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z. A Review of Overseas Studies on “Intrinsic Contestations” in Heritage Tourism. Tour. Trib. 2011, 9, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D. Conservation and Regeneration of Urban Architecture. Archit. Cult. 2022, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D. Study for Chinese Residential Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. Introduction to Chinese Housing; Architectural Engineering Press: Beijing, China, 1957; pp. 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Nexus between Cultural Heritage Management and the Mental Health of Urban Communities. Land 2022, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Beyond “Preserving the Past for the Future”: Contemporary Relevance and Historic Preservation. CRM J. Herit. Steward. 2011, 8, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Your solution, their problem—Their solution, your problem: The Gordian Knot of Cultural Heritage Planning and Management at the Local Government Level in Australia. disP Plan. Rev. 2006, 164, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J. The Conservation Plan: A Guide to the Preparation of Conservation Plans for Places of European Cultural Significance; National Trust of Australia, New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Information Sheet: Policy Provisions for Social Cohesion and Peace. 2014. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/Social_cohesion_and_peace_EN.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Kryder-Reid, E. Introduction: Tools for a critical heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 7, 691–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Aziz, N.A.; Mohd Ariffin, N.F.; Ismail, N.A.; Alias, A. Community Participation in the Importance of Living Heritage Conservation and Its Relationships with the Community-Based Education Model towards Creating a Sustainable Community in Melaka UNESCO World Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past Is a Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. World War II Remains on Central Pacific Islands: Perceptions of Heritage versus Priorities of Preservation. Pac. Rev. 1992, 3, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, C. Sense Matters: Aesthetic values of the Great Barrier Reef. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 4, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Usefulness of the Johari Window for the Cultural Heritage Planning Process. Heritage 2023, 6, 724–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, V.; Painho, M.; Vaz, E. Is the heritage really important? A theoretical framework for heritage reputation using citizen sensing. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre, M.; Mason, R. Introduction. In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage: Research Report; De la Torre, M., Ed.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. Assessing Values in Conservation Planning: Methodological Issues and Choices. In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage: Research Report; De la Torre, M., Ed.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- The Burra Charter. 1979. Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/Burra-Charter_1979.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Walter, N. From Values to Narrative: A New Foundation for the Conservation of Historic Buildings. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 20, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostões, A.; Ferreira, Z.; Roque, M. Adaptive Reuse. In Proceedings of the Modern Movement towards the Future 14th International Docomomo Conference Programme Docomomo International, Lisbon, Portugal, 6–9 September 2016; Available online: https://docomomo.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/14IDC_programme.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Lucchi, E. Environmental Risk Management for Museums in Historic Buildings through an Innovative Approach: A Case Study of the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obad Šćitaroci, M.; Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B. Heritage Urbanism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obad Šćitaroci, M. Preface: The Heritage Urbanism Approach and Method. In Cultural Urban Heritage—Development, Learning and Landscape Strategies; Šćitaroci, M.O., Šćitaroci, B.B.O., Mrđa, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. v–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Obad Šćitaroci, M.; Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B.; Mrđa, A. Introduction: The Revitalisation and Enhancement of Cultural Heritage in the Context of the Heritage Urbanism Approach. In Cultural Urban Heritage—Development, Learning and Landscape Strategies; Šćitaroci, M.O., Šćitaroci, B.B.O., Mrđa, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. xxi–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Obad Šćitaroci, M.; Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B. Models of Revitalisation and Enhancement of Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Use. In Cultural Urban Heritage—Development, Learning and Landscape Strategies; Šćitaroci, M.O., Šćitaroci, B.B.O., Mrđa, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 457–475. [Google Scholar]

- Petronela, T. The Importance of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Economy. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounanian, K.; van Tatenhove, J.P.M.; Hansen, C.J.; Delaney, A.E.; Bohnstedt, H.; Azzopardi, E.; Flannery, W.; Toonen, H.; Kenter, J.O.; Ferguson, L.; et al. Conceptualizing Coastal and Maritime Cultural Heritage Through Communities of Meaning and Oarticipation. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 212, 105806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourato, S.; Mazzanti, M. Economic Valuation of Cultural Heritage: Evidence and Prospects. In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage: Research Report; De la Torre, M., Ed.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. A Preliminary Study on the Transformation of Urban Centres in Contemporary China: Taking Xiangfuying Block of Nanjing as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics. Bull. State Counc. People’s Repub. China 1982, 19, 804–810.

- Wei, F.; Xu, W.; Cui, M. Theory and Practice of Preservation and Renewal of Historic District; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S. Reflections on Urban Renewal of Shanghai. Archit. Pract. 2019, 7, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. 10 November 2011. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/160163 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Han, D. Progresses of Interaction and Inclusion: The Practice of Conservation and Regeneration of Xiaoxihu Block in Nanjing. Archit. J. 2022, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Han, D.; Huang, J. The Process-ness and Participation of Urban Design in the Small-scale and Gradual Conservation and Regeneration of the Xiaoxihu Historic Area in Nanjing. Time + Archit. 2021, 1, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Han, D. Publicity beyond Boundaries Spatial Inheritance and Dynamic Regeneration of Duicao Alley at Xiaoxihu Block. Archit. J. 2022, 1, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Han, D. Participatory Self-renewal Mechanism under the Interaction of Property Rights and Policy: A Case Study of Xu House in Xiaoxihu Block, Nanjing. New Archit. 2022, 6, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Dong, Y.; Han, D. Policy Exploration of Small-scale and Gradual Conservation and Regeneration of Xiaoxihu District in Nanjing. Jiangsu Constr. 2021, 4, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, H. Strategies and Paths for Renewal of Industrial Remains in the Age of Inventory; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Tong, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, L. Value Analysis and Rehabilitation Strategies for the Former Qingdao Exchange Building—A Case Study of a Typical Modern Architectural Heritage in the Early 20th Century in China. Buildings 2022, 17, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T. Memory, Place Attachment and the Practice of Gentrification in the Process of Shanghai’s Urban Spatial Reconfiguration. J. Tongji Univ. 2015, 6, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Aoki, N.; Xu, S. Dynamics of Gentrification of Historic Industrial Neighbourhoods under the Market Transition: A Case Study of Tianjin. New Archit. 2020, 2, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xiao, L.; Chen, M. Preliminary Exploration of Approaches to Community Participatory Planning: Case Study of “New Qinghe Experiment” in Beijing. Urban Plan. Forum 2020, 1, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Kinoshita, I.; XU, M. Theory Analysis and Sustainable Operation Mode Research on Participatory Design in the Context of Community Design. Archit. J. 2018, S1, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Liu, M.; Huang, Y. A New Model of Community Participation: A Case Study of “Jointly Development” Workshop in Zengcuo’an, Xiamen. Urban Plan. Forum 2018, 9, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Practicing Micro Urban Regeneration in Shanghai. Archit. J. 2020, 10, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Tong, M. Micro Urban Regeneration: From the Networks to Nodes and Vice Versa. Archit. J. 2020, 10, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Liu, S. Research on the Comlex Adaptability of Urban Architectural Heritage in the Period of Inventory Planning: A Case Study of Harbin City. Mod. Urban Res. 2020, 8, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. “Historic” versus “in History”: Reflections on the Regeneration and Conservation Plan of the En’ning Road Historic District in Guangzhou. Herit. Archit. 2019, 2, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Shao, R.; Lan, W. Space Gene. City Plan. Rev. 2019, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Li, Y.; Lan, W. Space gene: An urban design method to inherit the Chinese traditional planning thoughts—From Suzhou historic urban area to the Xiongan New Area. Sci. Sin. (Technol.) 2023, 5, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. Typological Mapping Study of Courtyard Construction—Culture System in Chinese Dwelling Buildings. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Xue, L.; Liu, Y. Illustration of Old Residential Buildings in Jinan; Jinan Press: Jinan, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Regulations on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural City of Jinan. 2020. Available online: http://nrp.jinan.gov.cn/art/2020/10/9/art_48149_4760807.html?xxgkhide=1 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Q. Heritage-Based Spatial Form Consideration: Western Urban Planning Concepts Used in Chinese Urban (Dalian) Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caja, M. Reconstructing historical context: German cities and the case of Lübeck. ANUARI d’arquit. Soc. Res. J. 2021, 1, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokey, E.; Zeckhauser, R. A Primer for Policy Analysis; W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, F. Sino-foreign Real Estate Negotiation in Modern Times–Based on Historical Investigation in Shandong. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University, Hefei, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peckham, R. Introduction: The Politics of Heritage and Public Culture. In Rethinking Heritage: Cultures and Politics in Europe; Peckham, R., Ed.; I. B. Tauris: London, UK, 2003; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. Exhibitions of Power and Powers of Exhibition: An Introduction to the Politics of Display. In The Politics of Display: Museums, Science, Culture; Macdonald, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Issues in Cultural Tourism Studies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 34–120. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, K. The Representation of the Past: Museums and Heritage in the Postmodern World; Routledge: London, OH, USA, 1992; pp. 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y.; Sun, M. The Study on Some Issues Related to the Conservation and Planning for the Historic Streets and Areas in China. City Plan. Rev. 2001, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage. 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/vernacular_e.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas. 2011. Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Valletta-Principles-GA-_EN_FR_28_11_2011.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Lu, A. Talking about Urban Regeneration by Place. Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China, 2021, Unpublished work. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/TDLdqrGpCDo-FG-tjxFpYQ (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Zukin, S. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Babić, D.; Vatan Kaptan, M.; Masriera Esquerra, C. Heritage Literacy: A Model to Engage Citizens in Heritage Management. In Cultural Urban Heritage—Development, Learning and Landscape Strategies; Šćitaroci, M.O., Šćitaroci, B.B.O., Mrđa, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Opačić, V.T. Tourism Valorisation of Cultural Heritage. In Cultural Urban Heritage—Development, Learning and Landscape Strategies; Šćitaroci, M.O., Šćitaroci, B.B.O., Mrđa, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Humble Opinions on Urban Micro-Regeneration: Refering to Public Policy, Architectural Rethinking and Urban Authenticity. Time + Archit. 2016, 4, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hartog, H.; González Martínez, P. Redefining Heritage Values in Urban Regeneration: The Creation of New Identities in the Context of Shanghai’s Quest for Globalism. In The Twelfth International Convention of Asia Scholars (ICAS 12); Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, C.; Koetter, F. Collage City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Faganel, A.; Reisman, B.; Tomažič, T. Heritage Tourism, Retail Revival and City Center Revitalization: A Case Study of Koper, Slovenia. Heritage 2023, 6, 7343–7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S. Discussion on the phenomenon of housing suburbanization in the process of urbanization in China. Theory Mod. 2009, 5, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. “Transplanting” Yin Yu Tang to America: Preservation, Value, and Cultural Heritage. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 2014, 2, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, Y. Dancing with the Devil? Gentrification and Urban Struggles in, through and against the State in Nanjing, China. Geoforum 2021, 121, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Martínez, P. Echo from the underground: The heritage customization of subway infrastructures in Shanghai’s listed areas. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Special Plan for Urban Renewal of Jinan (2021–2035). 2022. Available online: http://wap.jinan.gov.cn/art/2022/12/12/art_15662_4783432.html (accessed on 15 June 2024).

| Model | Business Development Model | Adaptive Renewal Model | Micro-Update Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land concession | Almost all ceded | Some ceded | Some ceded |

| Subject | Real estate developers and government functionaries | Government departments, related organizations, community residents | Government departments, neighborhood committees, community residents, state-owned construction platforms, and community planners |

| Public participation | Real estate developer negotiates with the government, planning departments to force residents to comply with expropriation | Government-organized consultations within communities and residents, with technical support from designers | Consultation among the parties to carry out administrative services in accordance with the law |

| Relocation of aborigines | Relocation of all the people who used to live there | Some residents relocated after internal consultation | Some residents relocated after internal consultation |

| Typical cases | Sanfangqixiang in Fuzhou in1994, Xintiandi in Shanghai in 2007 | Wuzhen in Tongxiang in 1999, Nanchizi in Beijing in 2003 | Xiaoxihu in Nanjing in 2015 |

| Number | Location | Building Condition |

|---|---|---|

| MJ-LX-47 | 12 Xigongjie Street | Main gate, main room, east wing room, west wing room |

| MJ-LX-48 | 48 Xigongjie Street | Main room, east wing room, west wing room, backside building |

| MJ-LX-90 | 38 Xigongjie Street | Main room, east wing room, west wing room, backside building |

| MJ-LX-79 | 23 Shuangzhongci Street | Main gate, main rooms |

| MJ-LX-78 | 14 Kangshoufo Street | Main gate, main room, east wing room, west wing room |

| MJ-LX-69 | 43 Bianzhi Lane | Main room, west wing room, backside building |

| MJ-LX-70 | 45 Bianzhi Lane | Main gate, east wing room, west wing room, backside building |

| MJ-LX-72 | 71 Bianzhi Lane | Main gate, main room, east wing room, west wing room |

| MJ-LX-73 | 107 Bianzhi Lane | Main gate, east wing room, west wing room |

| MJ-LX-74 | 119 Bianzhi Lane | Main gate, east wing room, backside building |

| MJ-LX-56 | 53 Qiming Street | Main room, east wing room, west wing room |

| MJ-LX-57 | 55 Qiming Street | Main gate, main room, east wing room, west wing room |

| MJ-LX-62 | 83 Qiming Street | Main room, east wing room |

| MJ-LX-63 | 87 Qiming Street | Main gate, main room, west wing room |

| MJ-LX-64 | 91 and 93 Qiming Street | Main room, east wing room, west wing room, backside building |

| MJ-LX-52 | 5 Jiangjunmiao Street | Main room, east wing room, west wing room, backside building |

| MJ-LX-53 | 10 Jiangjunmiao Street | Main gate, east wing room, west wing room |

| Room Type | Living Room | Bedroom | Toilet | Kitchen | Dining Room | Study | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per capita area before renovation (including the illegal additions) | 3.08 m2 | 7.55 m2 | 0 m2 | 2.74 m2 | 1.86 m2 | 0.96 m2 | 2.70 m2 |

| Per capita area after renovation | 5.42 m2 | 5.68 m2 | 1.12 m2 | 0.83 m2 | 1.77 m2 | 2.35 m2 | 2.86 m2 |

| Function | North Courtyard | South Building | Plan | Expanded Axonometric View |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homestay | Living space units and a communal courtyard | Renovated into lobby and homestay |  |  |

| Office | Office space units and communal courtyards | Renovated into co-working space and leisure space |  |  |

| Exhibition | Exhibition space units and outdoor exhibition areas | Restoration of the courtyard layout to serve as exhibition and auxiliary office space |  |  |

| Cultural business | Commercial space units and outdoor exhibition Spaces | Restoration of the courtyard layout to serve as leisure space |  |  |

| Heritage Self-Renewal Model | Heritage Revitalization Model | Heritage Transformation Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Improve the quality of living spaces | Upgrade equipment and modernize spaces | Utilize economic and reuse values |

| Course of action | Negotiation and co-financing between local residents and local government, with experts and scholars proposing specific regeneration strategies | Local government negotiates with enterprises and local residents, and experts and scholars provide regeneration suggestions | Enterprises take the lead in acquiring property rights and land exchange, local governments supervise, and experts and scholars provide technical support. |

| Predicted outcomes | Renovations of some buildings | Upgrading of equipment in most buildings | Functional replacement of some buildings |

| Criteria | Whether living space has increased and living conditions have improved | Whether facilities have been upgraded and living spaces modernized | Whether the urban heritage has revitalized the surrounding area and increased its commercial value |

| Preferred choice of action | Local residents not willing to leave their residence | Local residents have more choices | Local residents are willing to leave their current residence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, L. Heritage Regeneration Models for Traditional Courtyard Houses in a Northern Chinese City (Jinan) in the Context of Urban Renewal. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16188089

Chen M, Wang H, Hu Z, Zhou Q, Zhao L. Heritage Regeneration Models for Traditional Courtyard Houses in a Northern Chinese City (Jinan) in the Context of Urban Renewal. Sustainability. 2024; 16(18):8089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16188089

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Meng, Hechi Wang, Zhanfang Hu, Qi Zhou, and Liang Zhao. 2024. "Heritage Regeneration Models for Traditional Courtyard Houses in a Northern Chinese City (Jinan) in the Context of Urban Renewal" Sustainability 16, no. 18: 8089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16188089

APA StyleChen, M., Wang, H., Hu, Z., Zhou, Q., & Zhao, L. (2024). Heritage Regeneration Models for Traditional Courtyard Houses in a Northern Chinese City (Jinan) in the Context of Urban Renewal. Sustainability, 16(18), 8089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16188089