Digital Communication Innovation of Food Waste Using the AISAS Approach: Evidence from Indonesian Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview of the Literature

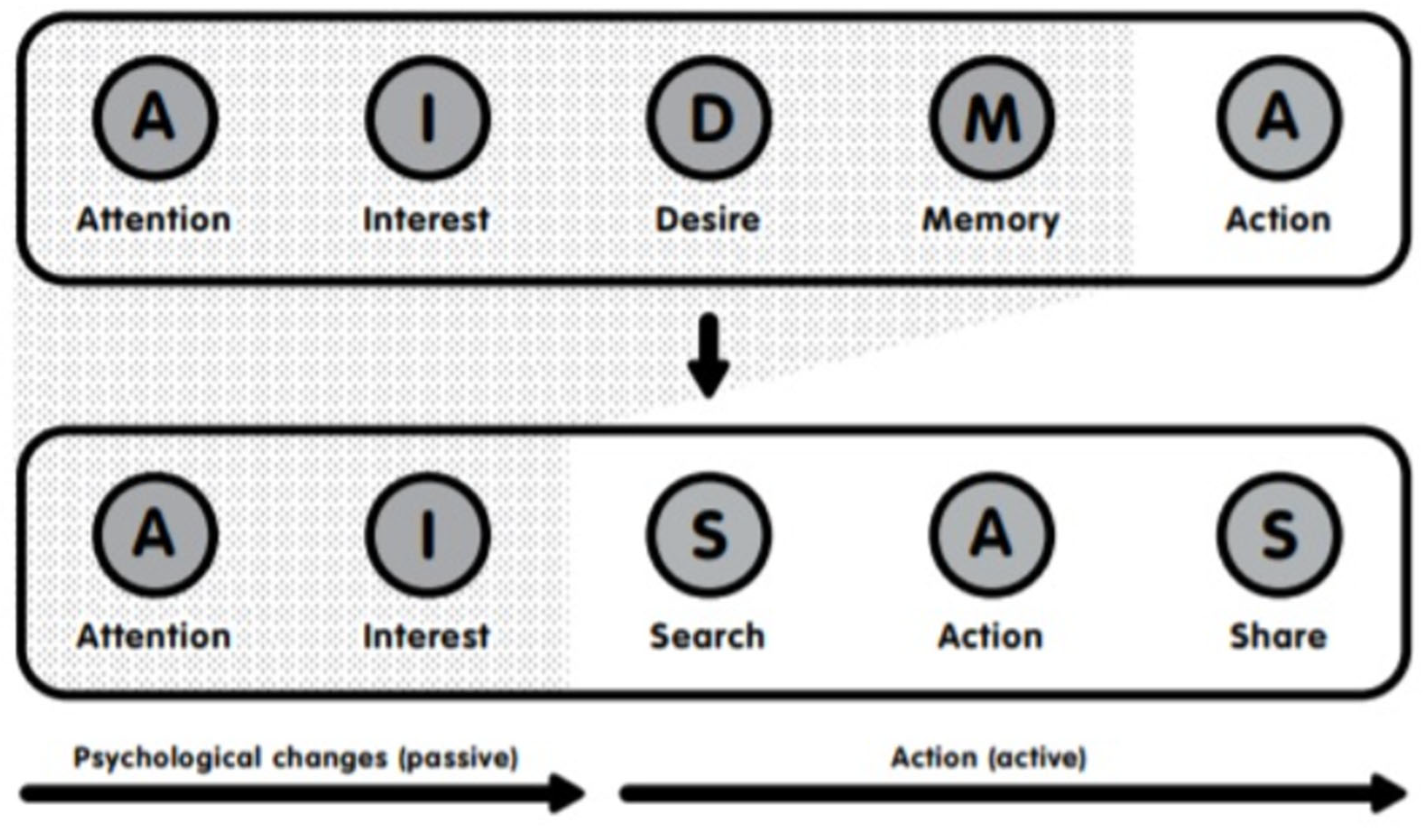

2.1. The AISAS Model

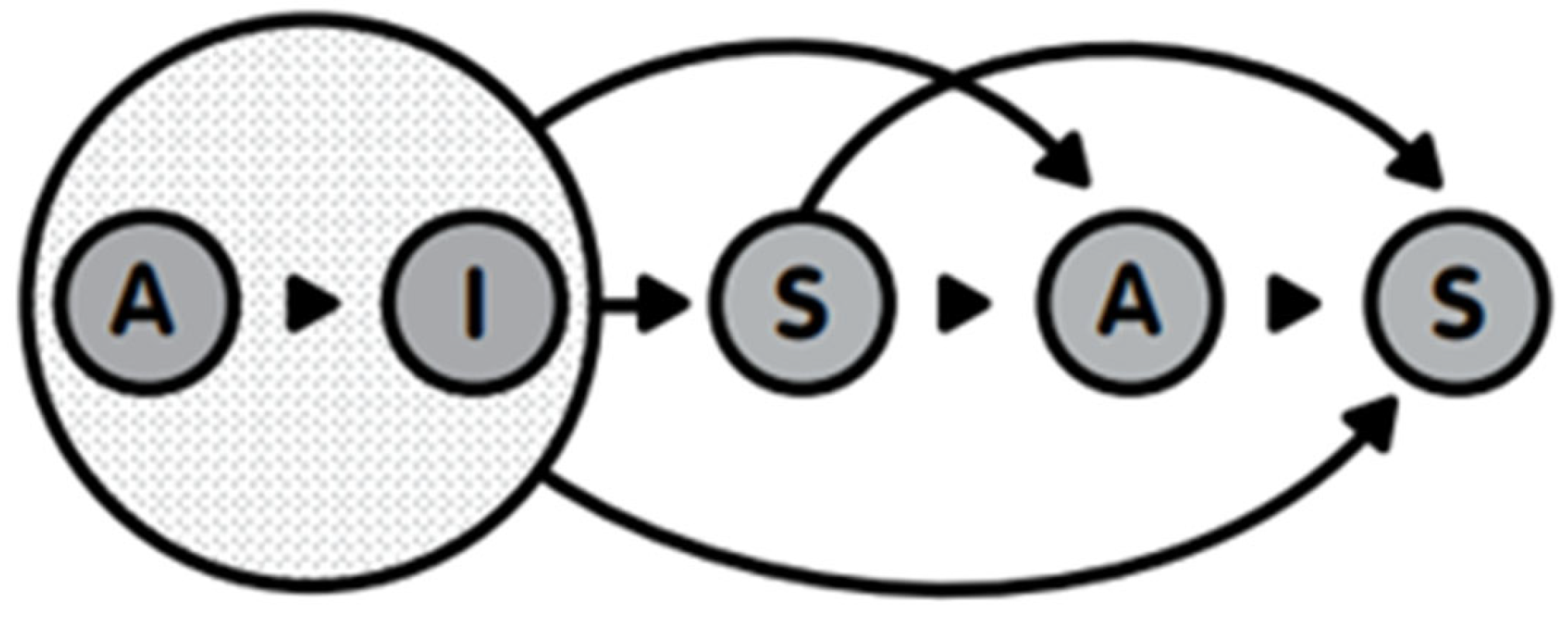

2.2. AISAS Non-Linear Models

3. Research Method

3.1. Design and Location

3.2. The Sampling Technique

3.3. The Research Instrument

3.4. Data Collection

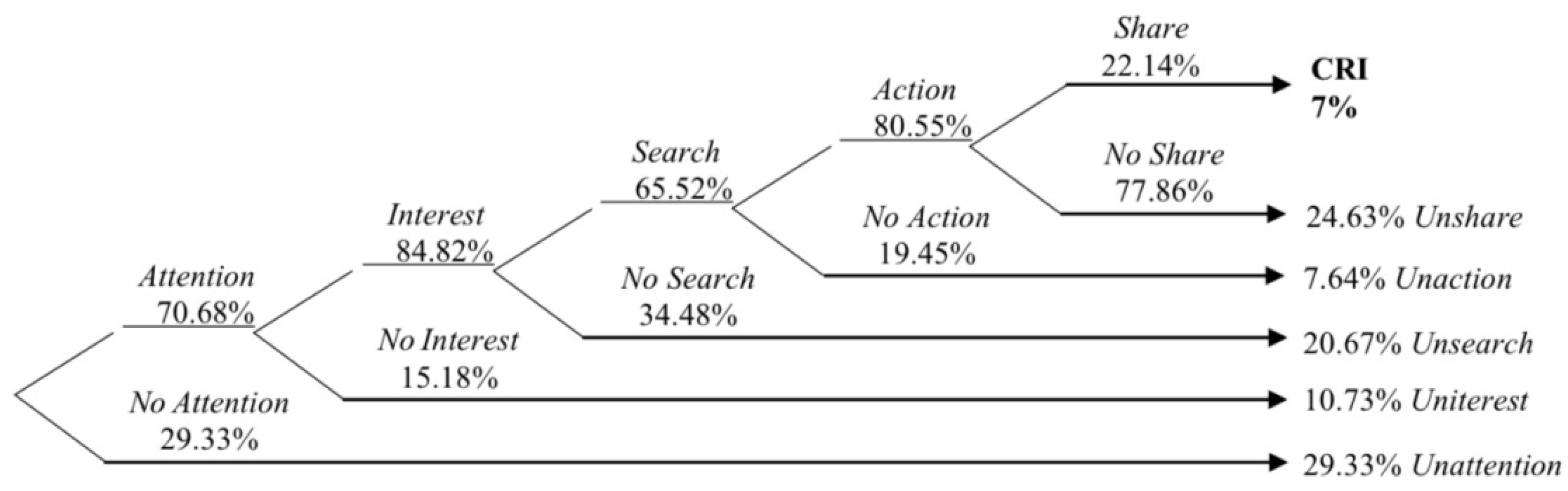

3.5. Data Analysis

- Attention;

- Unattention;

- Uninterested = Attention × No Interest;

- Unsearch = Attention × Interest × No Search;

- Unaction = Attention × Interest × Search × No Action;

- Unshare = Attention × Interest × Search × Action × No Share;

- CRI = Attention × Interest × Search × Action × Share.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Background

4.2. Frequency of Food Waste

4.3. Reasons for Food Waste Behaviors

4.4. Amount of Food Waste

4.5. AISAS

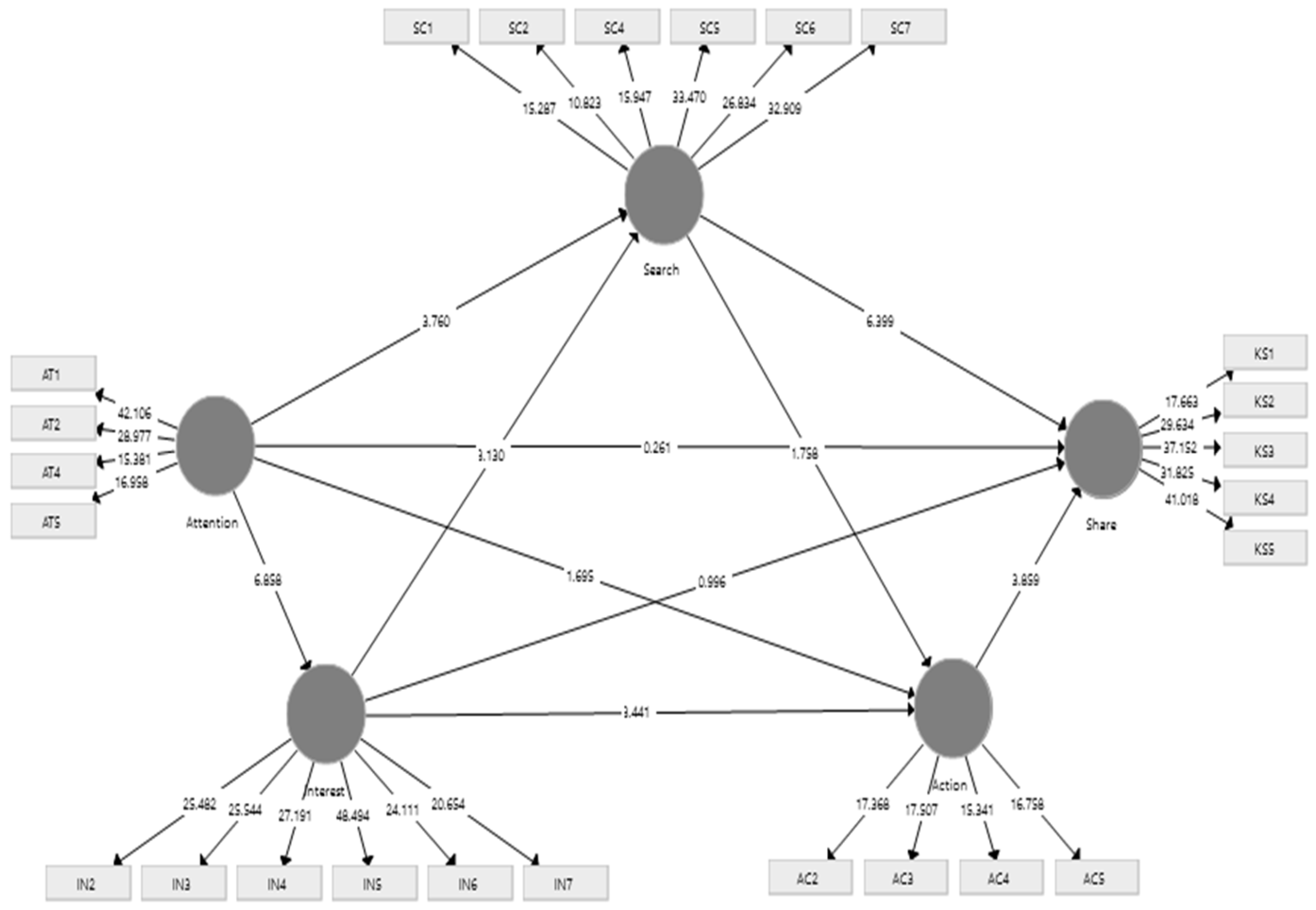

4.6. The Structural Model Test

4.7. Direct and Indirect Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. The Effect of Attention on Interest (H1)

5.2. The Effect of Attention on Search (H2)

5.3. The Effect of Attention on Action (H3)

5.4. The Effect of Attention on Knowledge Sharing (Share) (H4)

5.5. The Effect of Interest on Search (H5)

5.6. The Effect of Interest on Action (H6)

5.7. The Effect of Interest on Knowledge Sharing (Share) Behavior (H7)

5.8. The Effect of Search on Action (H8)

5.9. The Effect of Search on Knowledge Sharing (Share) Behavior (H9)

5.10. The Effect of Action on Knowledge Sharing (Share) Behavior (H10)

6. Research Implications

7. Research Limitations

8. Conclusions

Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Food Loss and Waste Must Be Reduced for Greater Food Security and Environmental Sustainability|Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1310271/icode/ (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Let’s Talk Science. The Environmental Impact of Wasted Food. Available online: https://letstalkscience.ca/educational-resources/stem-in-context/environmental-impact-wasted-food (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berjan, S.; Vaško, Ž.; Ben Hassen, T.; el Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Tomić, V.; Radosavac, A. Assessment of household food waste management during the COVID-19 pandemic in Serbia: A cross-sectional online survey. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 11130–11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP. Food Waste Index Report 2021; UN Environmental Program: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Development Planning Agency. Food Loss and Waste in Indonesia Supporting the Implementation of Circular Economy and Low Carbon Development. 2022. Available online: https://grasp2030.ibcsd.or.id/2022/07/07/bappenas-study-report-food-loss-and-waste-in-indonesia-supporting-the-implementation-of-circular-economy-and-low-carbon-development/ (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Qian, L.; Li, F.; Cao, B.; Wang, L.; Jin, S. Determinants of food waste generation in Chinese university canteens: Evidence from 9192 university students. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luecke, L. Haste to no waste: A multi-component food waste study in a University dining facility. Antonian Sch. Honor. Program 2015, 33, 1–31. Available online: https://sophia.stkate.edu/shas_honors/33 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Palaniveloo, K.; Amran, M.A.; Norhashim, N.A.; Mohamad-Fauzi, N.; Peng-Hui, F.; Hui-Wen, L.; Kai-Lin, Y.; Jiale, L.; Chian-Yee, M.G.; Jing-Yi, L.; et al. Food waste composting and microbial community structure profiling. Processes 2022, 8, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rumaihi, A.; McKay, G.; Mackey, H.R.; Al-Ansari, T. Environmental impact assessment of food waste management using two composting techniques. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Miloradovic, Z.; Djekic, S.; Tomasevic, I. Household food waste in Serbia—Attitudes, quantities and global warming potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Massow, M.; Parizeau, K.; Gallant, M.; Wickson, M.; Haines, J.; Ma, D.W.L.; Wallace, A.; Carroll, N.; Duncan, A.M. Valuing the multiple impacts of household food waste. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.W.; Zaman, U. Linking celebrity endorsement and luxury brand purchase intentions through signaling theory: A serial-mediation model involving psychological ownership, brand trust and brand attitude. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2021, 15, 586–613. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/246073 (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Solekah, N.A.; Handriana, T.; Usman, I. Millennials’ deals with plastic: The effect of natural environmental orientation, environmental knowledge, and environmental concern on willingness to reduce plastic waste. J. Consum. Sci. 2022, 7, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaerul, M.; Zatadini, S.U. Perilaku membuang sampah makanan dan pengelolaan sampah makanan di berbagai negara: Review. J. Ilmu Lingkung. 2020, 18, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falasconi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S.; Segrè, A.; Setti, M.; Vittuari, M. Such a shame! A study on self-perception of household food waste. Sustainability 2019, 11, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Talia, E.; Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Consumer behaviour types in household food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Li, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, L. Are the slimmer more wasteful? The correlation between body mass index and food wastage among Chinese Youth. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajbhandari-Thapa, J.; Ingerson, K.; Lewis, K.H. Impact of trayless dining intervention on food choices of university students. Arch. Public Health 2018, 76, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamri, G.B.; Azizal, N.K.A.; Nakamura, S.; Okada, K.; Nordin, N.H.; Othman, N.; MD Akhir, F.N.; Sobian, A.; Kaida, N.; Hara, H. Delivery, Impact and Approach of Household Food Waste Reduction Campaigns. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APJII. Profil Internet Indonesia 2022. Available online: https://apjii.or.id/download_survei/2feb5ef7-3f51-487d-86dc-6b7abec2b171 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Rani, A.; Shivaprasad, H.N. Where electronic word of mouth stands in consumer information search: An empirical evidence from India. Int. Boll. Manag. Econ. 2019, 10, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Consumers’ selection and use of sources for health information. In Social Web and Health Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, H.J.; Mohammed-Baksh, S.U.S. and Korean Consumers: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Product Information-Seeking and -Giving. J. Promot. Manag. 2020, 26, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Ellahi, A. Influence of electronic word of mouth on purchase intention of fashion products in social networking Websites. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11, 597–622. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/188307 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Wang, J.; Liu, L. Study on the mechanism of customers’ participation in knowledge sharing. Expert Syst. 2019, 36, e12367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.; Farooq, R. The synergetic effect of knowledge management and business model innovation on firm competence: A systematic review. J. Innov. Sci. 2019, 11, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shujahat, M.; Sousa, M.J.; Hussain, S.; Nawaz, F.; Wang, M.; Umer, M. Translating the impact of knowledge management processes into knowledge-based innovation: The neglected and mediating role of knowledge-worker productivity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.M.; Yang, J.J.; Lee, Y.K. The effect of leader competencies on knowledge sharing and job performance: Social capital theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, K.; Andree, T. The Dentsu Way Secrets of Cross Switch Marketing from the World’s Most Innovative Advertising Agency; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wirianti, F.; Rusfian, E. Electronic Word of Mouth Communication Analysis on Visitation Decision Making Process Using AISAS Model on INSTAGRAM USERS: Study on Visit Decision to Japan. Indo-IGCC, 2017. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:181325068 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Jun, W.; Li, S.; Yanzhou, Y.; Gonzalezc, E.D.S.; Weiyi, H.; Litao, S.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of precision marketing effectiveness of community e-commerce–An AISAS based model. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2021, 2, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.; Rashidin, M.S.; Xiao, Y. Investigating the impact of digital influencers on consumer decision-making and content outreach: Using dual AISAS model. Res. Ekon. Istraz. 2022, 35, 1183–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.L.; Shen, C.C.; Morrison, A.M.; Kuo, L.W. Online tourist behavior of the net generation: An empirical analysis in Taiwan based on the AISAS model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, D. AIDMA Model & AISAS Model in Digital Marketing Strategy. Available online: https://bbs.binus.ac.id/ibm/2017/06/aidma-model-aisas-model-in-digital-marketing-strategy/ (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Zhang, Q. A Research based on AISAS model of college students information contact investigation of Chinese dream. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1168, 032130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Sun, E.; Yang, X. Consumer visual attention and behaviour of online clothing. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2020, 33, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurrahim, M.S.; Najib, M.; Djohar, S. Development of AISAS model to see the effect of tourism destination in social media. J. App. Manag. 2019, 17, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktimawati, N.Y.D.; Primyastanto, M.; Abidin, Z. Analysis of social media relations to the decision of visiting in the ria beach recreation park of Kenjeran, Surabaya by AISAS method (attention, interest, search, action, share). Econ. Soc. Fish. Mar. J. 2018, 5, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pelawi, Y.N.; Irwansyah, A.; Aprilia, M.P. Implementation of marketing communication strategy in attention, interest, Search, Action, and Share (AISAS) Model through Vlog. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS), Singapore, 23–25 February 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhud, U.; Purnamasari, L.; Allan, M. Online behaviour of micro and small size entrepreneurs: Testing the attention-interest-search-action-share (AISAS) model. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2022, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talcott, T.N.; Gaspelin, N. Prior target locations attract overt attention during search. Cognition 2020, 201, 104282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Shi, L.; Gao, Z. Beyond the food label itself: How does color affect attention to information on food labels and preference for food attributes? Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusli, V.Y.; Pradina, Y.D. AISAS Model Analysis of General Insurance Company Strategy Using Instagram (Study at PT Asuransi Tokio Marine Indonesia). Am. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 5, 98–107. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/50698022/AISAS_Model_Analysis_of_General_Insurance_Company_Strategy_using_Instagram_Study_at_PT_Asuransi_Tokio_Marine_Indonesia (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Voramontri, D.; Klieb, L. Impact of social media on consumer behaviour. Int. J. Appl. Decis. Sci. 2019, 11, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.W.; Namkung, Y. The information quality and source credibility matter in customers’ evaluation toward food O2O commerce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridasan, A.C.; Fernando, A.G.; Saju, B. A systematic review of consumer information search Ii online and off-line environments. RAUSP Manag. J. 2021, 56, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, A.P.; Sumarwan, U.; Imam Suroso, A.; Najib, M. Influences of product attributes and lifestyles on consumer behavior: A case study of coffee consumption in Indonesia. J. Asian Fin. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 0939–0950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andini, T.; Kurniawan, F. Analisis pembentukan ekspektasi wisata lewat fitur pendukung pencarian informasi di Instagram. J. Stud. Komun. 2020, 4, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fannani, S.I.; Najib, M.; Sarma, M. The effect of social media toward organic food literacy and purchase intention with AISAS model. J. Manag. Agribus 2020, 17, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimah, R.J.; Haryanto, R.; Wardhana, M.W. The effectiveness of health protocol and COVID-19 prevention advertisements using Customer Response Index (CRI) on the community in Banjarmasin city. Inovbiz J. Inov. Bisnis 2022, 9, 7–12. Available online: http://ejournal.polbeng.ac.id/index.php/IBP/article/view/2000 (accessed on 5 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Andry, J.F.; Prayogo, T.; Wijaya, R.L.; Kantona, Y. Effectiveness of Shopee television advertising themed “super Goyang Shopee” in Jakarta society. Perspective 2019, 4, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiwan, T.Y. Efektivitas pesan iklan televisi tresemme menggunakan Customer Response Index (CRI) pada perempuan di Surabaya. J. E-Komun. Univ. Kristen Petra Surabaya 2013, 1, 298–307. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. P-values—A chronic conundrum. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Wang, Y. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing Research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2021, 59, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Hao, Q.; Han, G. Research on the marketing strategy of the new media age based on AISAS model: A case study of micro channel marketing. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Forum on Decision Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 477–486. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-2920-2_40 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Kim, J.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Sharing tourism experiences: The posttrip experience. J. Trav. Res. 2016, 56, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariastuti, I.; Azis, M.A. Strategi komunikasi pemasaran Onefourthree.Co di Instagram dalam Meningkatkan Brand Awareness. J. Pusta. Kom. 2019, 2, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why do consumers make green purchase decisions? Insights from A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qinghao, Y. Research on consumer behavior in tourism e-commerce in the post-pandemic era—Based on the AISAS model. Tour. Manag. Technol. Econ. 2022, 5, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Ain Baig, N.; Waheed, A. Significance of factors influencing online knowledge sharing: A study of higher education in Pakistan. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2016, 10, 1–26. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/188238 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Mikhaylov, A.; Moiseev, N.; Aleshin, K.; Burkhardt, T. Global climate change and greenhouse effect. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2897–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition. Food Waste: Causes, Impacts, and Proposals. 2012. Available online: https://www.barillacfn.com/m/publications/food-waste-causes-impact-proposals.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Amaly, L.; Hudrasyah, H. Measuring the effectiveness of marketing communication using AISAS ARCAS model. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 1, 352–364. Available online: https://journal.sbm.itb.ac.id/index.php/jbm/article/view/394 (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- Wirawan, F.W.; Hapsari, P.D. Analisis AISAS model terhadap product placement dalam film Indonesia (Studi kasus: Brand kuliner di film Ada Apa Dengan Cinta 2). REKAM J. Fotogr. Telev. Animasi 2016, 12, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kurnianti, A.W. Strategi komunikasi pemasaran digital sebagai penggerak desa wisata Kabupaten Wonosobo Provinsi Jawa Tengah. J. Ris. Komun. 2018, 1, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Ho, J.S.; Lau, P.M. Knowledge sharing in academic institutions: A study of multimedia university Malaysia. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 7, 313–324. Available online: http://www.ejkm.com/issue/download.html?idArticle=184&origin=publication_detail (accessed on 10 May 2023).

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 113 | 37.42 |

| Women | 118 | 62.58 |

| Age | ||

| 16–20 years | 213 | 70.53 |

| 21–25 years | 89 | 29.47 |

| Mean ± Std | 19.98 ± 1.50 | |

| Min–Max | 17–25 | |

| Origin | ||

| Banjar | 113 | 37.42 |

| Batak | 3 | 1.32 |

| Bugis | 12 | 3.97 |

| Chinese | 4 | 1.32 |

| Dayaks | 15 | 4.97 |

| Java | 132 | 43.71 |

| Other | 23 | 7.62 |

| Income | ||

| IDR < 500,000 | 73 | 24.17 |

| IDR 500,001–1,000,000 | 147 | 48.68 |

| IDR 1,000,001–3,000,000 | 74 | 24.50 |

| IDR 3,000,001–5,000,000 | 7 | 2.32 |

| IDR > 5,000,001 | 1 | 0.33 |

| Monthly food expenses | ||

| IDR < 500,000 | 101 | 33.44 |

| IDR 500,001–1,000,000 | 157 | 51.99 |

| IDR 1,000,001–3,000,000 | 43 | 14.24 |

| IDR 3,000,001–5,000,000 | 1 | 0.33 |

| Number of family members | ||

| ≤4 people | 160 | 52.98 |

| 5–7 people | 129 | 42.72 |

| ≥8 people | 13 | 430 |

| Food Types | Frequency of Food Waste (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely (<6 Meals) | Often (6–10 Meals) | Always (>10 Meals) | |

| Rice | 51.32 | 36.42 | 6.62 | 5.63 |

| Vegetables | 50.99 | 38.74 | 8.94 | 1.32 |

| Fruit and preparations | 66.23 | 27.15 | 5.63 | 0.99 |

| Sources of vegetable protein and processed products | 64.57 | 26.82 | 6.29 | 2.32 |

| Fish/chicken/beef/other meat | 63.25 | 27.81 | 5.63 | 3.31 |

| Processed meat products | 77.15 | 19.87 | 1.99 | 0.99 |

| Eggs and their preparations | 68.21 | 23.18 | 6.29 | 2.32 |

| Dairy products | 70.53 | 24.17 | 4.64 | 0.66 |

| Cake, bakery, snack, and cereal products | 57.95 | 35.76 | 5.30 | 0.99 |

| Root products | 57.95 | 35.76 | 5.30 | 0.99 |

| Pasta products | 64.90 | 28.81 | 4.64 | 1.66 |

| Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Low (<60) | 290 | 96.03 |

| Moderate (60–80) | 12 | 3.97 |

| High (>80) | 0 | 0 |

| Mean ± SD | 15.27 ± 17.54 | |

| Min–max | 0.00–75.76 | |

| Food Type | Total Food Waste (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1–2 | 3–4 | >4 | |

| Rice | 56.95 | 25.17 | 9.27 | 8.61 |

| Vegetable | 51.99 | 36.75 | 7.95 | 3.31 |

| Fruit and preparations | 72.52 | 19.87 | 4.30 | 3.31 |

| Sources of vegetable protein and processed products | 70.20 | 23.18 | 4.64 | 1.99 |

| Fish/chicken/beef/other meat | 71.52 | 22.52 | 3.97 | 1.99 |

| Processed meat products | 80.13 | 15.89 | 3.31 | 0.66 |

| Eggs and their preparations | 76.49 | 17.22 | 4.97 | 1.32 |

| Dairy products | 74.50 | 18.21 | 4.30 | 2.98 |

| Cake, bakery, snack, and cereal products | 65.56 | 24.83 | 6.62 | 2.98 |

| Root products | 66.56 | 26.49 | 4.97 | 1.99 |

| Pasta products | 71.19 | 19.87 | 5.63 | 3.31 |

| Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Low (<60) | 294 | 97.35 |

| Moderate (60–80) | 7 | 2.32 |

| High (>80) | 1 | 0.33 |

| Mean ± SD | 14.16 ± 16.49 | |

| Min–max | 0.00–100 | |

| Category | Community Type (%) | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IAAS | Non-IAAS | ||

| Attention | |||

| Low (<60) | 34.41 | 50.24 | 0.001 ** |

| Moderate (60–80) | 46.24 | 38.28 | |

| High (>80) | 19.35 | 11.48 | |

| Mean ± SD | 65.77 ± 16.55 | 58.33 ± 19.92 | |

| Min–max | 25.00–100 | 0.00–100 | |

| Interest | |||

| Low (<60) | 5.38 | 23.44 | 0.000 ** |

| Moderate (60–80) | 55.91 | 47.37 | |

| High (>80) | 38.71 | 29.19 | |

| Mean ± SD | 76.28 ± 14.54 | 68.13 ± 21.67 | |

| Min–max | 33.33–100 | 0.00–100 | |

| Search | |||

| Low (<60) | 37.63 | 50.24 | 0.039 * |

| Moderate (60–80) | 46.24 | 43.06 | |

| High (>80) | 16.13 | 6.70 | |

| Mean ± SD | 60.93 ± 20.14 | 55.95 ± 18.80 | |

| Min–max | 0.00–100 | 0.00–100 | |

| Action | |||

| Low (<60) | 9.68 | 39.23 | 0.000 ** |

| Moderate (60–80) | 36.56 | 30.14 | |

| High (>80) | 53.76 | 6.70 | |

| Mean ± SD | 80.11 ± 16.94 | 66.43 ± 23.08 | |

| Min–max | 33.33–100 | 0.00–100 | |

| Share | |||

| Low (<60) | 76.34 | 87.08 | 0.000 ** |

| Moderate (60–80) | 17.20 | 9.57 | |

| High (>80) | 6.45 | 3.35 | |

| Mean ± SD | 40.07 ± 24.39 | 23.54 ± 25.32 | |

| Min–max | 0.00–100 | 0.00–100 | |

| Path | Path Coefficient | t-Values | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention → Interests | 0.431 | 6.950 | H1 is accepted |

| Attention → Search | 0.245 | 3.750 | H2 is accepted |

| Attention → Actions | 0.120 | 1.748 | H3 is rejected |

| Attention → Share | 0.205 | 0.252 | H4 is rejected |

| Interest → Search | 0.205 | 3.213 | H5 is accepted |

| Interest → Action | 0.279 | 3.487 | H6 is accepted |

| Interest → Share | −0.055 | 1014 | H7 is rejected |

| Search → Action | 0.108 | 1.751 | H8 is rejected |

| Search → Share | 0.294 | 6.627 | H9 is accepted |

| Action → Share | 0.205 | 3.828 | H10 is accepted |

| Latent Variables | Construct Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|

| Attention | 0.83 | 0.55 |

| Interest | 0.92 | 0.67 |

| Search | 0.86 | 0.51 |

| Action | 0.85 | 0.59 |

| Knowledge Sharing Behavior (Share) | 0.93 | 0.72 |

| eWOM (electronic word of mouth) | 0.85 | 0.55 |

| Emotion | 0.87 | 0.63 |

| Path Variables | Influence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | Total | |

| Attention → Interest | 0.431 | - | 0.431 |

| Attention → Search | 0.245 | 0.088 | 0.333 |

| Attention → Action | - | 0.156 | 0.156 |

| Attention → Share | - | 0.131 | 0.131 |

| Interest → Search | 0.205 | - | 0.205 |

| Interest → Action | 0.279 | 0.022 | 0.301 |

| Interest → Share | - | 0.122 | 0.122 |

| Search → Share | 0.294 | 0.022 | 0.316 |

| Action → Share | 0.205 | - | 0.205 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuliati, L.N.; Simanjuntak, M. Digital Communication Innovation of Food Waste Using the AISAS Approach: Evidence from Indonesian Adolescents. Sustainability 2024, 16, 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020488

Yuliati LN, Simanjuntak M. Digital Communication Innovation of Food Waste Using the AISAS Approach: Evidence from Indonesian Adolescents. Sustainability. 2024; 16(2):488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020488

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuliati, Lilik Noor, and Megawati Simanjuntak. 2024. "Digital Communication Innovation of Food Waste Using the AISAS Approach: Evidence from Indonesian Adolescents" Sustainability 16, no. 2: 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020488

APA StyleYuliati, L. N., & Simanjuntak, M. (2024). Digital Communication Innovation of Food Waste Using the AISAS Approach: Evidence from Indonesian Adolescents. Sustainability, 16(2), 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020488