Running toward Sustainability: Exploring Off-Peak Destination Resilience through a Mixed-Methods Approach—The Case of Sporting Events

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Background of the Study

2.2. Exploring Organizers’ Perceptions

2.3. Running-Event Organizers’ Interviews

- How does the off-season running event enhance local destination sustainability, encompassing both economic and socio-cultural aspects?

- In what ways do you involve the local community in the organization of the event to enhance destination sustainability during the off-season?

- What strategies do you find most effective in enriching a running event to thrive during the low-season while promoting sustainability?

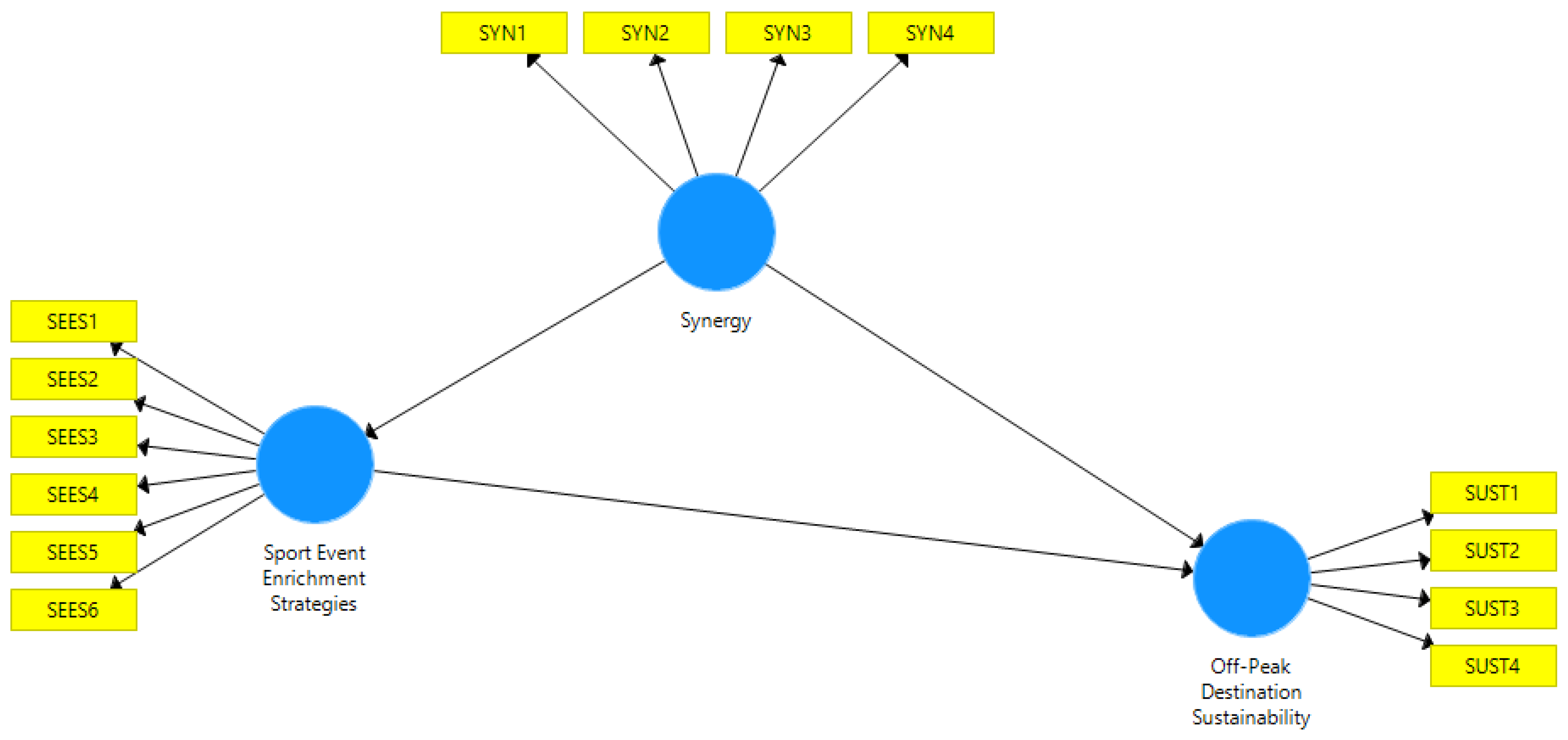

2.4. Conceptual Framework: Running Event Organizers’ Perspectives

2.4.1. Sustainability

- Income Increase (SUST1) is a pivotal dimension that organizers and existing literature affirm as a significant outcome of running events. Foundational studies, such as the seminal work of Walo et al. [28], highlighted that the economic influx generated during an athletic event extends far and beyond mere participation fees. Expenditure on food services, accommodations, and shopping activities by athletes and visitors significantly contributes to the financial well-being of the local community. This economic stimulation is particularly pronounced during off-season weekends, providing an extra and crucial income boost for local businesses.

- Employment Opportunities Increase (SUST2) emerges as another vital component of sustainability. The organization of running events generates a rise in demand for services, prompting the hiring of additional staff by professionals during event days. The race becomes a catalyst for job creation and the extension of existing employment contracts, aligning with the objective of providing enhanced services to the influx of visitors. This economic activity during low-season periods contributes substantially to the financial stability of locals.

- Investment in new facilities (SUST3) marks a tangible outcome of the economic impact of running events. Local professionals and the community, recognizing the heightened demand during event days, invest in new facilities. The financial footprint of the event, as emphasized by organizers, plays a crucial role in inspiring these investments, leading to sustained development beyond the event period.

- Leisure Opportunities (SUST4) extend beyond the sporting activities and enhance community well-being. The positive social value generated by running events is evidenced by the increased collaboration and voluntary efforts of the local society. From the creation of a festive atmosphere to the initiation of running consciousness among individuals, the race becomes a basis for fostering social cohesion, cooperation, and communication among locals.

2.4.2. Sport Event Enrichment Strategies

- Tour Activities (Tours in the Area, Natural and Historical Sights, etc.) (SEES1) variable involves the strategic integration of guided tours and walks to showcase the region’s cultural and natural treasures. Organizers aim to provide a unique experience for participants while promoting the local culture and heritage through exploring natural trails and cultural routes, enhancing the overall race extension strategy.

- Exhibitions with Local Products of the Region (SEES2) variable indicates that organizers plan events and fairs to complement the race, showcasing the region’s local products, cuisine, and cultural elements. These exhibitions entertain participants and visitors, contributing to the promotion of local traditions and fostering a deeper connection between the event and the community.

- Regarding Fun and Actions for All Visitors (Athletes, Escorts, Family) (SEES3) variable, organizers recognize the diverse needs of participants and their families; thus, they introduce additional activities for non-participants, including options like yoga, swimming, music bands, children’s playgrounds, and traditional dance clubs. The goal is to create a holistic experience that caters to a wide audience, making the event enjoyable for everyone involved.

- The variable Social Media Marketing (SEES4) emphasizes the important role of social media in event promotion. Organizers acknowledge the importance of platforms like Instagram and Facebook for publicity and reputation building. Despite variations in social media proficiency, the consensus is that an effective online presence significantly contributes to event success and visibility, underlining the dynamic nature of digital marketing.

- In the context of Sport Websites Administration/Use (SEE5), organizers leverage websites to promote races, aiming to enhance participant experience and streamline registration processes. Engaging with well-known running websites amplifies the visibility of their events within the broader running community. While some focus on the continuous improvement of their websites, others prioritize official platforms to reach a wider audience, showcasing the interconnectedness of technology and race promotion.

- The variable Love for the Birthplace (SEE6) underscores organizers’ shared passion and pride for their race locations. Their love for the region serves as a driving force behind their commitment to contribute to local tourism development. This emotional connection motivates efforts to showcase the unique features of their birthplaces, fostering a sense of responsibility for environmental protection and community engagement.

2.4.3. Synergy

- The directions from authorities (SYN1) variable reflects the organizers’ desire for local authorities’ guidance in developing sustainable initiatives within the community. They seek transparency, long-term planning, and cooperation from authorities to enhance the event’s quality and expand activities, yet express frustration due to limited support and resources, hindering their ability to enrich the event experience.

- The variable Running Culture (SYN2) elucidates the local engagement, perception, and the community’s attitude toward running. The comments emphasized the necessity for a vibrant local running culture. The organizers underscored that lack of local enthusiasm for running presented a challenge for the event and the community, inhibiting local engagement and support.

- The variable Participant Encouragement (SYN3) within the construct of Synergy is centered on the strategies employed to motivate participants, encouraging their return to the event and the region. Collaboration among multiple stakeholders aims to create attractive incentives for the athletes and visitors, offering special gifts, medals, discounts, and additional benefits.

- The variable Community Collaborations (SYN4) epitomizes the strategic partnerships established by event organizers with local stakeholders. These alliances involve negotiated arrangements such as discounted services, unique offers, and cooperative ventures.

2.5. Hypotheses Evolution

- Income Increase (SUST1): Running events significantly boost local income, especially off-season.

- Employment Opportunities Increase (SUST2): Organizing events creates jobs, enhancing local financial stability, especially in the low-season.

- Investment in New Facilities (SUST3): Event demand leads to community investment, sustaining economic development.

- Leisure Opportunities (SUST4): Running events foster social ties, providing leisure opportunities beyond sports.

- Tour Activities (SEES1): Strategic integration of guided tours and walks showcasing the region’s cultural and natural treasures, enhancing the overall race extension strategy.

- Exhibitions with Local Products (SEES2): Planning events and fairs to complement the race, showcasing local products, cuisine, and cultural elements, contributing to the promotion of local traditions.

- Fun and Activities for All Visitors (SEES3): Recognizing diverse needs, organizers introduce additional activities for non-participants, creating a holistic experience for everyone involved.

- Social Media Marketing Skills (SEES4): Acknowledging the pivotal role of social media in event promotion, organizers leverage platforms like Instagram and Facebook for publicity, emphasizing the dynamic nature of digital marketing.

- Sport Websites Administration/Use (RES5): Utilizing websites to enhance participant experience, streamline registration processes, and amplify event visibility within the broader running community.

- Guidance from Local Authorities (SYN1): Organizers seek clearer guidance, transparency, and cooperation from local authorities for sustainable event development.

- Building Running Culture (SYN2): Emphasis on cultivating a vibrant local running culture and addressing challenges related to the lack of local enthusiasm for running.

- Participant Encouragement (SYN3): Strategies employed to motivate participants, fostering collaboration among stakeholders to create compelling incentives for athletes and visitors.

- Community Collaborations (SYN4): Strategic partnerships established by organizers with local stakeholders, involving negotiated arrangements and cooperative ventures.

3. Quantitative Methodology

3.1. Scale and Measure Development

3.2. Participants and Collection of the Study Data

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques

3.3.1. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

3.3.2. Evaluation of the Structural Model (Hypotheses Testing)

4. Discussion and Implications

5. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WTTC—World Travel & Tourism Council. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2022, Global Trends. 2022. Available online: https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2022/EIR2022-Global%20Trends.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Gibson, H.J.; Kaplanidou, K.; Kang, S.J. Small-scale event sport tourism: A case study in sustainable tourism. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.; Hinch, T. Tourism, sport and seasons: The challenges and potential of overcoming seasonality in the sport and tourism sectors. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maditinos, Z.; Vassiliadis, C.; Tzavlopoulos, Y.; Vassiliadis, S.A. Sports events and the COVID-19 pandemic: Assessing runners’ intentions for future participation in running events–evidence from Greece. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. International Tourism Highlights, 2023 Edition—The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism (2020–2022), October 2023; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Tourism and Rural Development: Understanding Challenges on the Ground—Lessons Learned from the Best Tourism Villages by UNWTO Initiative; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, T.; Fayossolà, E.; Weiss, B.; del Río, I.M. Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations; A Guidebook; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Fernández, F.J.; Jiménez-Hernández, I.; Ostos-Rey, M.D.S. Seasonality and efficiencyof the hotel industry in the balearic Islands: Implications for Economic and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Wen, R.; Zeng, Y.; Ye, K.; Khotphat, T. The influence of seasonality on the sustainability of livelihoods of households in rural tourism destinations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. The economic determinants of tourism seasonality: A case study of the Norwegian tourism industry. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1732111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Poczta, J. A small-scale event and a big impact—Is this relationship possible in the world of sport? The meaning of heritage sporting events for sustainable development of tourism—Experiences from Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.; Andrade, C.S.; Van Rheenen, D.; Sobry, C. Portugal: Small scale sport tourism events and local sustainable development. The case of the III Running Wonders Coimbra. In Small Scale Sport Tourism Events and Local Sustainable Development: A Cross-National Comparative Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta, J.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E. Modern running events in sustainable development—More than Just taking care of health and physical condition (Poznan Half Marathon Case Study). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reier Forradellas, R.; Náñez Alonso, S.L.; Jorge-Vázquez, J.; Echarte Fernández, M.Á.; Vidal, M.N. Entrepreneurship, sport, sustainability and integration: A business model in the low-season tourism sector. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomino, A.C.; Perić, M.; Wise, N. Assessing and considering the wider impacts of sport-tourism events: A research agenda review of sustainability and strategic planning elements. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heebkhoksung, K.; Rattanawong, W.; Vongmanee, V. A New Paradigm of a Sustainability-Balanced Scorecard Model for Sport Tourism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Pereira, E.; Rosado, A.; Maroco, J.; McCullough, B.; Mascarenhas, M. Understanding spectator sustainable transportation intentions in international sport tourism events. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1972–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, B. A Theoretical Model of Strategic Communication for the Sustainable Development of Sport Tourism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Kim, K.; Uysal, M. Perceived impacts of festivals and special events by organizers: An extension and validation. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Chen, J. Festival visitor motivation from the organizers’ points of view. Event Management. Event Manag. 2001, 7, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, S.; Grady, J. Sponsorship program protection strategies for special sport events: Are event or-ganizers outmaneuvering ambush marketers? J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 550–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuvront, S.N.; Sollanek, K.J.; Fattman, K.; Troyanos, C. Validation of a Mobile Application Water Planning Tool for Road Race Event Organizers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkarane, S.; Vassiliadis, C.A.; Gianni, M. Exploring professionals’ perceptions of tourism seasonality and sports events: A qualitative study of Kissavos marathon race. Enlightening Tourism. A Pathmaking J. 2022, 12, 24–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhanen, L. Stakeholder participation in tourism destination planning another case of missing the point? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2009, 34, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.M.; Eskerud, L.; Hanstad, D.V. Brand creation in international recurring sports events. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.; Saayman, M. Creating a memorable spectator experience at the Two Oceans Marathon. J. Sport Tour. 2012, 17, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoopetch, C.; Kongarchapatara, B.; Nimsai, S. Tourism Forecasting Using the Delphi Method and Implications for Sustainable Tourism Development. Sustainability 2022, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walo, M.; Bull, A.; Breen, H. Achieving economic benefits at local events: A case study of a local sports event. Festiv. Manag. Event Tour. 1996, 4, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80519-7. [Google Scholar]

- Leguina, A. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1932–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022. 2022. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/ (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Pradhan, P. A threefold approach to rescue the 2030 Agenda from failing. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Abbrev. | Loading | Inner VIF | a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suggested Cut-Off Level | at least 0.5 and ideally >0.7 | >0.5 | >0.7 | >0.7 | >0.5 | |

| Off-Peak Season Sustainability | SUST | 0.812 | 0.877 | 0.641 | ||

| Income Increase | SUST1 | 0.841 | ||||

| Employment Opportunities Increase | SUST2 | 0.849 | ||||

| New facilities Investment | SUST3 | 0.793 | ||||

| Leisure Opportunities | SUST4 | 0.711 | ||||

| Sport Event Enrichment Strategies | SSES | 1.748 | 0.812 | 0.865 | 0.517 | |

| Tour Activities (Tours in the Area, Natural and Historical Sights, etc.) | SEES1 | 0.726 | ||||

| Exhibitions with Local Products of the Region | SEES2 | 0.703 | ||||

| Fun and Actions for All Visitors (Athletes, Escorts, Family) | SEES3 | 0.700 | ||||

| Social Media Marketing Skills | SEES4 | 0.691 | ||||

| Sport Websites Administration/Use | SEES5 | 0.815 | ||||

| Love for the Birthplace | SEES6 | 0.670 | ||||

| Synergy | SYN | 1.000 | 0.732 | 0.831 | 0.553 | |

| Directions from authorities | SYN1 | 0.796 | ||||

| Running Culture | SYN2 | 0.671 | ||||

| Participant Encouragement | SYN3 | 0.719 | ||||

| Community Collaborations | SYN4 | 0.783 |

| SEES | SUST | SYN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEES1 | 0.726 | 0.374 | 0.430 |

| SEES2 | 0.703 | 0.472 | 0.420 |

| SEES3 | 0.700 | 0.385 | 0.424 |

| SEES4 | 0.691 | 0.451 | 0.493 |

| SEES5 | 0.815 | 0.535 | 0.558 |

| SEES6 | 0.670 | 0.372 | 0.477 |

| SUST1 | 0.562 | 0.841 | 0.492 |

| SUST2 | 0.474 | 0.849 | 0.553 |

| SUST3 | 0.355 | 0.793 | 0.455 |

| SUST4 | 0.527 | 0.711 | 0.418 |

| SYN1 | 0.607 | 0.504 | 0.796 |

| SYN2 | 0.373 | 0.474 | 0.671 |

| SYN3 | 0.402 | 0.419 | 0.719 |

| SYN4 | 0.528 | 0.389 | 0.783 |

| SEES | SUST | SYN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEES | 0.719 | ||

| SUST | 0.607 | 0.801 | |

| SYN | 0.654 | 0.602 | 0.744 |

| SEES | SUST | SYN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEES | 0.719 | ||

| SUST | 0.607 | 0.801 | |

| SYN | 0.654 | 0.602 | 0.744 |

| β | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Path Coefficients | |||

| H1: Sport Event Enrichment Strategies → Off-Peak Destination Sustainability | 0.373 | 3.449 | 0.001 |

| H2: Synergy → Off-Peak Destination Sustainability | 0.358 | 3.074 | 0.002 |

| H3: Synergy → Sport Event Enrichment Strategies | 0.654 | 3.522 | 0.000 |

| Specific Indirect Effects | |||

| H4: Synergy → Sport Event Enrichment Strategies → Off-Peak Destination Sustainability | 0.244 | 2.268 | 0.024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkarane, S.; Gianni, M.; Vassiliadis, C. Running toward Sustainability: Exploring Off-Peak Destination Resilience through a Mixed-Methods Approach—The Case of Sporting Events. Sustainability 2024, 16, 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020576

Gkarane S, Gianni M, Vassiliadis C. Running toward Sustainability: Exploring Off-Peak Destination Resilience through a Mixed-Methods Approach—The Case of Sporting Events. Sustainability. 2024; 16(2):576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020576

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkarane, Sofia, Maria Gianni, and Chris Vassiliadis. 2024. "Running toward Sustainability: Exploring Off-Peak Destination Resilience through a Mixed-Methods Approach—The Case of Sporting Events" Sustainability 16, no. 2: 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020576

APA StyleGkarane, S., Gianni, M., & Vassiliadis, C. (2024). Running toward Sustainability: Exploring Off-Peak Destination Resilience through a Mixed-Methods Approach—The Case of Sporting Events. Sustainability, 16(2), 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020576