Does Green Overseas Investment Improve Public Perception in Host Countries? Evidence from Chinese Energy Engagement in 32 African Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Hypotheses

4. Data and Methods

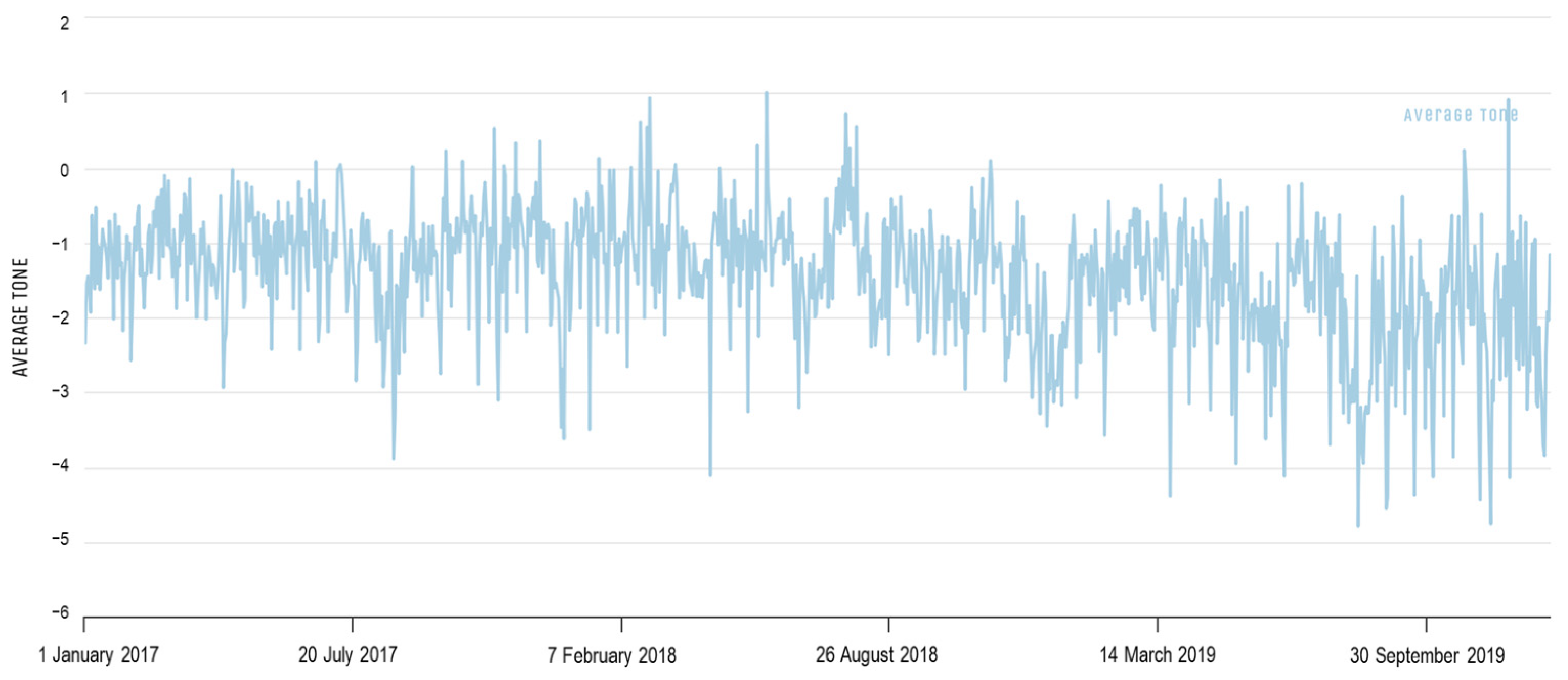

4.1. Dependent Variable

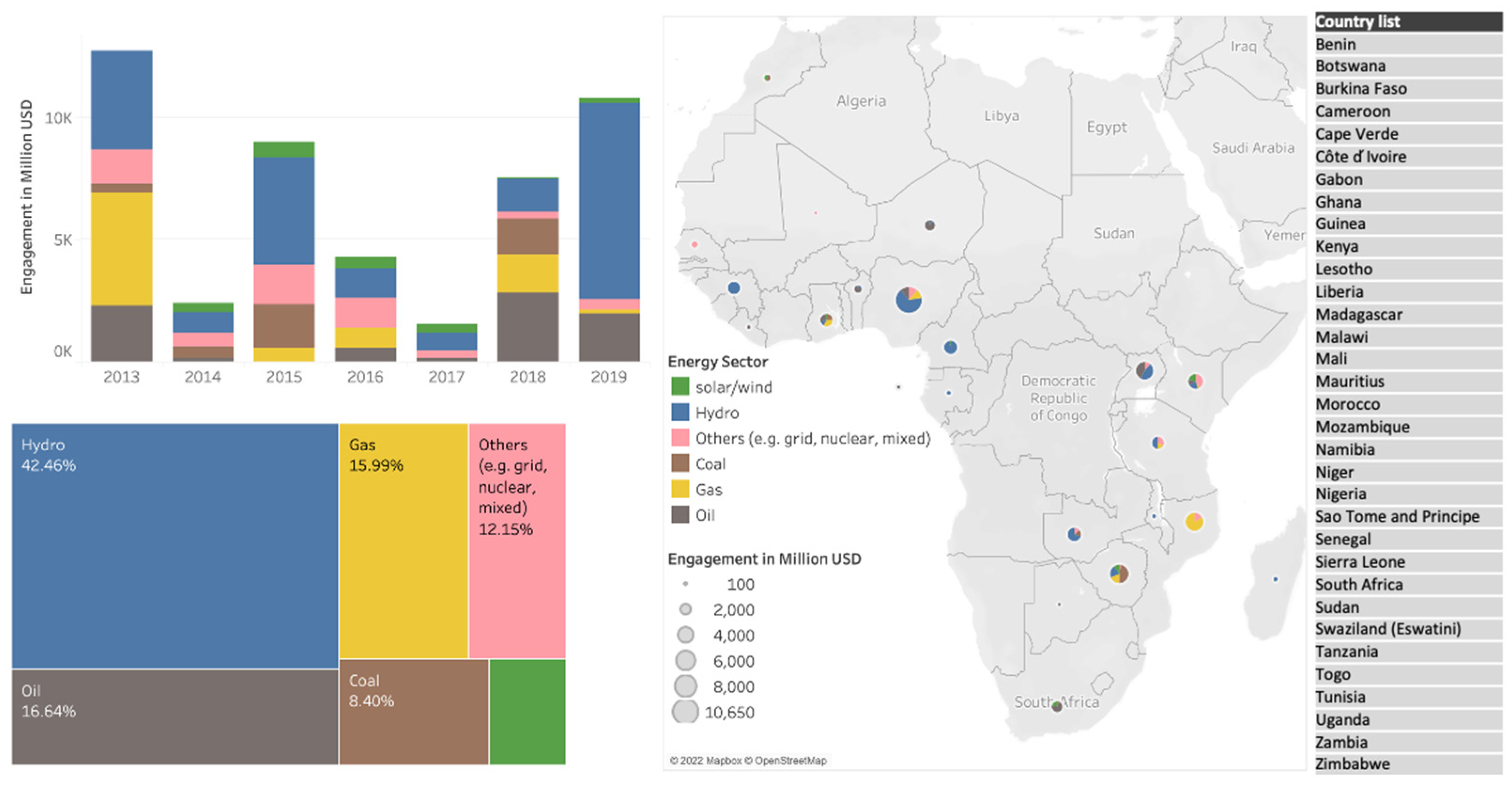

4.2. Exploratory Variables

4.3. Control Variables

4.4. Dataset

5. Results

5.1. Baseline Fixed-Effect Model

5.2. Attitude to Climate Change

5.3. Unemployment Rate

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of 32 African Countries included in the Analysis

| No. | Country | Country Code |

| 1 | Benin | BEN |

| 2 | Botswana | BWA |

| 3 | Burkina Faso | BFA |

| 4 | Cameroon | CMR |

| 5 | Cape Verde | CPV |

| 6 | Côte d'Ivoire | CIV |

| 7 | Gabon | GAB |

| 8 | Ghana | GHA |

| 9 | Kenya | KEN |

| 10 | Lesotho | LSO |

| 11 | Liberia | LBR |

| 12 | Madagascar | MDG |

| 13 | Malawi | MWI |

| 14 | Mali | MLI |

| 15 | Mauritius | MUS |

| 16 | Morocco | MAR |

| 17 | Mozambique | MOZ |

| 18 | Namibia | NAM |

| 19 | Niger | NER |

| 20 | Nigeria | NGA |

| 21 | Sao Tome and Principe | STP |

| 22 | Senegal | SEN |

| 23 | Sierra Leone | SLE |

| 24 | South Africa | ZAF |

| 25 | Sudan | SDN |

| 26 | Swaziland (Eswatini) | SWZ |

| 27 | Tanzania | TZA |

| 28 | Togo | TGO |

| 29 | Tunisia | TUN |

| 30 | Uganda | UGA |

| 31 | Zambia | ZMB |

| 32 | Zimbabwe | ZWE |

References

- Nakano, J. Greening or Greenwashing the Belt and Road Initiative? Center for Strategic & International Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ploywarin, S.; Song, Y.; Sun, D. Research on Factors Affecting Public Risk Perception of Thai High-Speed Railway Projects Based on “Belt and Road Initiative”. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Wang, Y. Towards a green world: The impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on the carbon intensity reduction of countries along the route. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 28510–28526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gilbert, S.; Wang, Y.; Cabré, M.M.; Gallagher, K.P. Moving the Green Belt and Road Initiative: From Words to Actions; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Scissors, D. China Global Investment Tracker (CGIT). 2022. Available online: https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/ (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Gallagher, K.S.; Qi, Q. Policies Governing China’s Overseas Development Finance Implications for Climate Change; Center for International Environment and Resource Policy: Medford, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nedopil, C. Green finance for soft power: An analysis of China’s green policy signals and investments in the Belt and Road Initiative. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selormey, E.E.; Dome, M.Z.; Osse, L.; Logan, C. Change Ahead: Experience and Awareness of Climate Change in Africa; Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 60; Afrobarometer: Accra, Ghana, 2019; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Woo, W.T.; Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Why Is Green Finance Important? SSRN Electron. J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Sustainable Banking—History and Current Developments. SSRN Electron. J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, C.; Michaelowa, K. China in Africa: Competition for traditional development finance institutions? World Dev. 2019, 120, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellner, W.; Dreher, A.; Fuchs, A.; Parks, B.C.; Strange, A. Can Aid Buy Foreign Public Support? Evidence from Chinese Development Finance; Global Research Institute: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenauer, V.Z.; Fuchs, A.; Brückner, L. The effects of trade, aid, and investment on China’s image in Latin America. J. Comp. Econ. 2021, 49, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. Soft Power: China’s Emerging Strategy in International Politics by Mingjiang Li (Ed.): Lexington Books, Plymouth, 2009, 275 pp., US$80, ISBN 978-0-7391-3377-4. Strateg. Anal. 2010, 35, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J. Reputation and International Politics; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8014-7489-7. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Smith, T.; McKnight, B. Environmental finance: A research agenda for interdisciplinary finance research. Econ. Model. 2016, 59, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economics Forum. Global Risks Report 2022; World Economics Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikowitz Family Foundation. African Youth Survey 2022; Ichikowitz Family Foundation: Sandton, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Quitzow, R.; Thielges, S. The German energy transition as soft power. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2022, 29, 598–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClory, J. The Soft Power 30: A Global Rannking of Soft Power; Korea Foundation: Seogwipo-si, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P. Can China’s Economic Statecraft Win Soft Power in Africa? Unpacking Trade, Investment and Aid. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 2019, 24, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekorwe, M.; Chingwete, A.; Okuru, M.; Samson, R. China’s Growing Presence in Africa Wins Largely Positive Popular Reviews; Afrobarometer Round 6; Afrobarometer: Accra, Ghana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Custer, S.; Sethi, T.; Solis, J.A.; Lin, J.J.; Ghose, S.; Gupta, A.; Knight, R.; Baehr, A. Silk Road Diplomacy: Deconstructing Beijing’s Toolkit to Influence South and Central Asia; AidData: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Rambures, D.; Felipe Escobar, D. China’s Decision Making System. In China’s Financial System; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kurlantzick, J. China’s Soft Power in Africa. In Soft Power: China’s Emerging Strategy in International Politics; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kurlantzick, J. Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power is Transforming the World; Yale Univ. Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-300-13628-9. [Google Scholar]

- Examining the Cross-Border Acquisition Strategy of Chinese Companies: The Moderating Roles of State Ownership and Institutional Transition—Jiatao Li, Zhenzhen Xie. 2013. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1548051812472371 (accessed on 17 December 2023).

- Nedopil, C. China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2023 H1; FISF Green Finance & Development Center Brief; FISF Green Finance & Development Center: Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Springer, C.; Steffen, B. Cofinancing and Infrastructure Project Outcomes in Chinese Lending and Overseas Development Finance; GCI Working Paper; Boston University Global Development Policy Center: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dave, B. Silk Road Economic Belt: Effects on China’s soft power diplomacy in Kazakhstan. In China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Impact on Central Asia; Central Asia Program; George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Zadek, S. Decarbonizing the Belt and Road—A Green Finance Roadmap; McKinsey & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mabey, N.; McNally, R. Foreign Direct Investment and the Environment: From Pollution Havens to Sustainable Development; WWF-UK: Woking, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Voituriez, T.; Yao, W.; Larsen, M.L. Revising the ‘host country standard’ principle: A step for China to align its overseas investment with the Paris Agreement. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreror, A.G.; Xu, J. Countries’ Perception of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A Big Data Analysis; Bruegel: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center Global Indicators Database. 2019. Available online: https://www.pewglobal.org/database/ (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Busse, M.; Groizard, J.L. Foreign Direct Investment, Regulations, and Growth; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leetaru, K.; Schrodt, P.A. GDELT: Global data on events, location, and tone. In ISA Annual Convention; Citeseer: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Chan, F.K.S.; Li, N.; Chen, C.; Chen, W.-Q.; Chan, H.K. Improving urban flood resilience via GDELT GKG analyses in China’s Sponge Cities. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voukelatou, V.; Miliou, I.; Giannotti, F.; Pappalardo, L. Understanding peace through the world news. EPJ Data Sci. 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, D.; Burke, J. Predicting Social Unrest Using GDELT. In Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition; Perner, P., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10935, pp. 103–116. ISBN 978-3-319-96132-3. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, F.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Z.; Cheng, J.-J.; Wang, H. Predicting Social Unrest Events with Hidden Markov Models Using GDELT. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2017, 2017, 8180272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.; Weidmann, N.B. Using machine-coded event data for the micro-level study of political violence. Res. Polit. 2014, 1, 205316801453992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedopil, C. China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2021; Green Finance & Development Center: Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Milanowitsch, B.K. Impact of Asian Soft Power in Latin America—China and South Korea as Emerging Powers in the Subcontinent. Ph.D. Thesis, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, J. Editorial: Green or red: Challenges for fish and freshwater biodiversity conservation related to hydropower. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2021, 31, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.A.; Marty, R.; Roessler, P. Foreign Aid and Soft Power: Great Power Competition in Africa in the Early Twenty-first Century. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2022, 52, 1355–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Xiang, J. Pursuing Soft Power through the Confucius Institute: A Large-N Analysis. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 2019, 24, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazys, S.; Dukalskis, A. Rising Powers and Grassroots Image Management: Confucius Institutes and China in the Media. Chin. J. Int. Polit. 2019, 12, 557–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wasserman, H.; Mano, W. (Eds.) China’s Media and Soft Power in Africa; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-349-71377-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zadek, S. Establishing China’s Green Financial System: Progress Report 2017; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Chen, X.; Wohlfarth, P. Public participation, investment networks, and China’s outward FDI: Evidence from 58 countries along the belt and road. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2022, 51, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Qian, X.; Liu, T. Belt and road initiative and Chinese firms’ outward foreign direct investment. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2019, 41, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, J.-M.F.; Lu, F. Thinking Hard About Soft Power: A Review and Critique of the Literature on China and Soft Power. Asian Perspect. 2012, 36, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.J. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the COVID-19 crisis. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2020, 3, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Fan, C. The role of China’s aid and ODI in the economic growth of African countries. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2020, 44, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ma, Z.; Liu, S.; Ma, X.; Acker, K.; Myers, M.; Brautigam, D.; Gallagher, K. China Overseas Finance Inventory Database; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Time Span | Source | Number of Obs | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public perception of China | 2017–2019 | GDELT | 96 * | −0.406 | 0.574 | −1.865 | 0.552 |

| Chinese investment in renewable energy (million US$) | 2015–2019 | CGIT | 165 | 112 | 512 | 0 | 5790 |

| Chinese investment in non-renewable energy (million US$) | 2015–2019 | CGIT | 165 | 88.3 | 364 | 0 | 2600 |

| China’s FDI as a share of total FDI | 2015–2019 | CARI | 128 | 0.108 | 0.229 | −0.649 | 1.282 |

| Trade with China as a share of total trade | 2015–2019 | CARI and World Bank | 128 | 0.148 | 0.127 | 0.0179 | 0.612 |

| # of Chinese workers | 2015–2019 | CARI | 131 | 2361.924 | 2593.776 | 0 | 11,088 |

| # of Confucius Institutes | 2015–2019 | Web search | 165 | 1.212 | 1.109 | 0 | 6 |

| # of Chinese media branches | 2015–2019 | Web search | 165 | 0.582 | 0.820 | 0 | 4 |

| # of Chinese-invested media branches | 2015–2019 | Web search | 165 | 0.382 | 0.487 | 0 | 1 |

| # of Chinese embassy Twitter accounts | 2015–2019 | Web search | 165 | 0.055 | 0.228 | 0 | 1 |

| Percentage of people responding climate change has a negative impact (%) | 2017 | Afrobarometer | 32 | 66.456 | 15.237 | 31.5 | 93.1 |

| Unemployment rate | 2015–2019 | World Bank | 165 | 8.963 | 7.448 | 0.471 | 28.181 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of China | Perception of China | Perception of China | Perception of China | |

| Investment in renewable energy | 0.00165 | 0.00288 ** | ||

| (1.70) | (2.80) | |||

| Investment in non-renewable energy | −0.000156 * | −0.000105 | ||

| (−2.46) | (−0.10) | |||

| China’s FDI share | −0.00605 | −0.0366 | ||

| (−0.05) | (−0.26) | |||

| China’s trade share | 2.469 | 2.529 | ||

| (1.67) | (1.67) | |||

| Number of Chinese workers | 0.000101 | 0.0000689 | ||

| (1.74) | (1.08) | |||

| Number of Confucius Institute | −0.152 | −0.128 | ||

| (−0.82) | (−0.68) | |||

| Number of Chinese media branches | 0.202 | 0.210 | ||

| (1.34) | (1.26) | |||

| Number of Chinese-invested media branches | −0.196 * | −0.222 * | ||

| (−2.32) | (−2.13) | |||

| Number of Chinese embassy Twitter accounts | −0.120 | −0.0773 | ||

| (−1.37) | (−0.65) | |||

| R—square | 0.1802 | 0.3984 | 0.1747 | 0.3728 |

| n | 96 | 89 | 96 | 89 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of China | Perception of China | |

| Investment in renewable energy | 0.00770 | |

| (1.60) | ||

| Attitude to climate change * investment in renewable energy | −0.00511 | |

| (−1.04) | ||

| Investment in non-renewable energy | −0.00000912 | |

| (−0.00) | ||

| Attitude to climate change * investment in non-renewable energy | −0.000122 | |

| (−0.05) | ||

| n | 89 | 89 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of China | Perception of China | Perception of China | Perception of China | |

| Investment in non-renewable energy | 0.00106 | −0.000889 | ||

| (0.64) | (−0.93) | |||

| Unemployment (c) | −0.0537 | −0.0518 | ||

| (−0.69) | (−0.71) | |||

| Investment in non-renewable energy * unemployment (c) | −0.000219 | |||

| (−0.76) | ||||

| Investment in renewable energy | −0.00110 | 0.000168 | ||

| (−0.25) | (0.05) | |||

| Investment in renewable energy * unemployment (c) | 0.000309 | |||

| (1.02) | ||||

| Unemployment (i) | 0.0961 | −0.00825 | ||

| (0.59) | (−0.07) | |||

| Investment in non-renewable energy * unemployment (i) | 0.456 *** | |||

| (3.79) | ||||

| Investment in renewable energy * unemployment (i) | 0.00327 | |||

| (0.91) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nedopil, C.; Yue, M. Does Green Overseas Investment Improve Public Perception in Host Countries? Evidence from Chinese Energy Engagement in 32 African Countries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020590

Nedopil C, Yue M. Does Green Overseas Investment Improve Public Perception in Host Countries? Evidence from Chinese Energy Engagement in 32 African Countries. Sustainability. 2024; 16(2):590. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020590

Chicago/Turabian StyleNedopil, Christoph, and Mengdi Yue. 2024. "Does Green Overseas Investment Improve Public Perception in Host Countries? Evidence from Chinese Energy Engagement in 32 African Countries" Sustainability 16, no. 2: 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020590