1. Introduction

Cities generally have intense socio-economic activities at their core and often grow outwards due to demographic change, transport systems, movement corridors, and land values, giving rise to what is known as a metropolitan region. Studies of cities such as Paris [

1], London [

2], and Mumbai [

3] illustrate the suburban and peri-urban development triggered by train corridors. Metropolitan cities in India are no exception; they have shown enormous growth since the economic reforms of 1990 and now occupy a central place in the imagination of Indian urbanism [

4]. While the core city continues to sustain socio-economic activities igniting the economic engine of the region, the outward growth has also led to the diversity of urban character on the periphery of the metropolis [

5]. Yet many metropolitan regions exhibit a variety of alternative urbanisation processes. This paper presents one such alternative process where the creation of a tourism attraction in the periphery has generated a corridor type of urbanisation in the hitherto rural hinterland outside a city, thus contributing to a different imagination of the metropolitan region itself.

Based on the study of Lavasa tourist town, an attraction developed in the periphery of the Pune Metropolitan Region (PMR) in India, this paper has two objectives. First, the empirical findings are used to illustrate the salient features of tourism urbanisation due to the creation of a tourism attraction in the hinterland lying at the fringe of a metropolitan region. Moving beyond the existing concentration of such studies in the developed world (for example, see [

6,

7]), this paper adds an example from a developing country like India, where tourism is burgeoning at a rapid pace and is changing the tourism landscape. Second, following the pioneering work of Pearce [

8] and Oppermann [

9], this paper argues for the need to include the idea of peripheral attractions and corridors and the formal/informal continuum of socio-spatial activities that they support as key elements in conceptualising metropolitan tourism in a developing country.

The aim of this paper is to contribute to the theoretical discourse on tourism urbanisation by examining the case of a newly created tourist destination in a metropolitan region. Developing tourist destinations around rural landscapes on the periphery of urban regions is gathering momentum in developing countries as leisure-oriented tourism, particularly as day trips, has increased considerably. The significance of this study is that it offers a nuanced understanding of how these processes of tourism development are changing the landscape in the region, which is relevant for many cities in developing countries. The insights from the study can help in devising ways to reduce the impacts of tourism. In this research, the key concepts around tourism urbanisation are explored and examined using the context of the Pune Metropolitan Region (PMR) and by introducing Lavasa—the tourist destination located in the catchment of a watershed in the western periphery of the region. The research employed a spatial mapping method for tracing the urbanisation process in and around Lavasa through three time periods in its growth as a tourist destination. By focusing on mapping the tourism-induced economic enterprise on the main access road to Lavasa and the developments of tourism events and activities within Lavasa, this paper shows how a tourism corridor was shaped. It is seen that the formal tourism experience offered at the destination was supported by an equally important informal economy of tourism services that was offered on the corridor. Thus, a hybrid pattern of tourism-led urbanisation was uncovered, which is quite significant for the relationship between cities and their regions in developing countries.

2. Region, Tourism, and Tourism Urbanisation

2.1. Region and Tourism

There are many ways of defining and delineating a region; the most common way is to refer to a cohesive landmass/entity generally bound by very distinct geographical features such as coastlines, hills, rivers, deserts, and forests [

10]. Such geographical articulation is often used to mark administrative and political boundaries as well—a system loosely followed for defining regions [

11,

12]. However, the utility of such territorial delineations of a region has increasingly been questioned in both developed and developing countries where unending sprawl accompanied by rapid urban growth has become the dominant characteristic of urbanisation of rural and semi-rural areas around cities [

1,

2,

3,

13]. As a result, there is a prevalence of large urban conurbations broadly known as metropolitan regions that have both urban centres and rural hinterlands. Tourism in cities is often understood through the lens of urban areas as shown in the examples of many cities across the world (in fact, an entire journal called Journal of Tourism Cities is dedicated to the study of urban tourism). Following the other direction (both in a geographical and experiential sense) is rural tourism, which has also gained considerable scholarly attention through the study of landscape, community, reminiscences of village life, religious and cultural interactions, and social change [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The perceptions of a region often influence its spatiality. Scholars argued that boundaries are valid only in the time and space in which a region, especially the metropolitan region, is defined [

18]. However, there are counter-narratives as well. When perceived boundaries mismatch with the administrative boundaries, there are ambiguities generated about the expanse of the region [

19]. Forman [

10] has argued that natural boundaries should not be the singular criteria for defining an urban region; the urban culture cultivated by the population committed to urban life also plays a significant role in distinguishing such a geographical region. Thus, while regions can be defined in many tangible and intangible ways, our focus here is on exploring the burgeoning leisure tourism in metropolitan regions that involves consuming serene nature in the hinterland of metropolitan cities.

2.2. Tourism Urbanisation

A direct connection between tourism and urbanisation was first comprehensively explored in the pioneering work of Mullins [

6] in the study of coastal cities in Australia. Emphasising the hedonistic pursuits in the “sun and sand” driven tourism, Mullins posits tourism urbanisation as a process of “urbanization based on sale and consumption of pleasure” [

6]. In this conceptualisation, “the narrow piece of land abutting the beach and extending the length of the coastlines” generates a distinct spatial form of a “tourist strip” that houses most tourism-related infrastructure and services [

6]. Mullins also theorises that the petite bourgeoisie [

20] plays a significant role in providing small-scale retail and personnel services to sustain and boost tourism urbanisation. The idea of tourism urbanisation is further explored by Gladstone [

7] in a study of eight American cities, which he categorises as “leisure cities” and “tourism metropolises”. The former “cater more to retirees and those with the non-employment in-come” (e.g., social security and rentier income), whereas the latter is “gambling centres or cities with enormous entertainment complexes”. Following Mullins, Gladstone’s analysis is primarily focused on demographic change and highlights the rapid rate of population growth and transformation of land uses due to the need for the physical infrastructure necessary for tourism services. He argues that tourism urbanisation is mainly fueled by the populous middle class.

The nature of tourism consumption generates ‘symbolically distinctive forms’ in tourism urbanisation and tourist cities [

7]. For instance, while discussing tourism urbanization in China, scholars using Mullin’s conceptualisation illustrate how tourism attractions have been created for consumption and the building of tourism infrastructure and services has rapidly urbanized those towns with “a unique pattern of land use and land development; the booming of tertiary economic sectors; and the emergence of a flexible regime of labor force” [

21,

22]. Kranjčević, J., and Hajdinjak, S., expand the idea to a sub-national level using the case study of two towns in Croatia and argue how tourism-led urban growth forced the decentralisation of spatial planning in response to the free market induced by private sectors in an erstwhile socialist system [

23]. Holleran applies the concepts of tourism urbanisation to the level of the European Union and shows how rural lands in different European countries became rapidly urbanised due to the creation of an “international milieu of new leisure spaces” that helped in the free “flow of visitors and capital” [

24].

The realities of formal and informal processes of tourism urbanisation are more pronounced in developing countries as shown by Oppermann [

9] who studied several Southeast Asian countries where domestic tourism has a major share in the overall tourism economy. Oppermann, based on the studies in an Asian context, rejects the idea that formal and informal sectors are competing. He stresses the overlapping geographies of formal and informal tourist spaces and indicates that most informal tourism spaces emerge on the movement corridors of two formal tourism spaces. This could be more applicable to regions that constitute both city and rural areas as attractions for tourism. However, the paucity of understanding influence of tourism in metropolitan regions is acute in the existing literature, and more so in developing countries such as India where the urban–rural divide seems to occupy the central debate.

In India, metropolitan planning authorities have existed for many decades to administer large metropolises beginning with Delhi, Mumbai (Bombay), Kolkata (Calcutta), and Chennai (Madras) in the 1970s (their rapid urban growth was evident with their population reaching millions in the early 1970s) [

25]. In recent years, many more metropolitan regions were declared around the rapidly growing urban centres [

26] and the economic centrality of the metropolis was a key factor for regional urbanization [

26,

27,

28] as such cities had a way of dealing with tourism within their jurisdiction. However, the same cannot be said about the rural areas that were managed using the agenda of rural development framed via the “Five Year Plans” [

29]. In doing so, the interdependent networks of the hinterland and the city were sidelined and that weakened the sustainability of rural regions. Thus, India’s weak regional planning process [

30] paid very little attention to the phenomenon of the city region [

11,

31,

32], which is often misunderstood as a city in the region. Most often, the territorial demarcation of a region overlapped and coincided with the “District” [

29]—the spatial jurisdiction administered as the third level of governance and administration (the other two being federal and state levels). It is within this spatial jurisdiction of the District that the metropolitan region comprising city/cities, towns, and rural areas is framed. And it is this metropolitan region that is the primary focus of this paper.

Following the key concepts from Opperman and Mullins, that is, the nature of tourism leads to distinctive patterns of urbanisation, and that these may be a mix of formal and informal [

16,

33] tourist spaces, we now examine how tourism has influenced urban growth in the metropolitan region of Pune. For this study, we build on conceptual approaches to tourist spaces and connecting corridors [

34]. In addition, we employ the geographical approach proposed in Pearce’s [

8] framework of scales and themes that allows us to examine processes of change at various scales in our case study of Lavasa—a new tourist town in the metropolitan region of Pune. While regions can be defined in many tangible and intangible ways, our focus here is on the understanding of a region based on the burgeoning culture of leisure tourism [

35,

36]—a salient trait of the rising urban middle class in India [

28,

37,

38] that involves consuming serene nature in the hinterland of metropolitan cities.

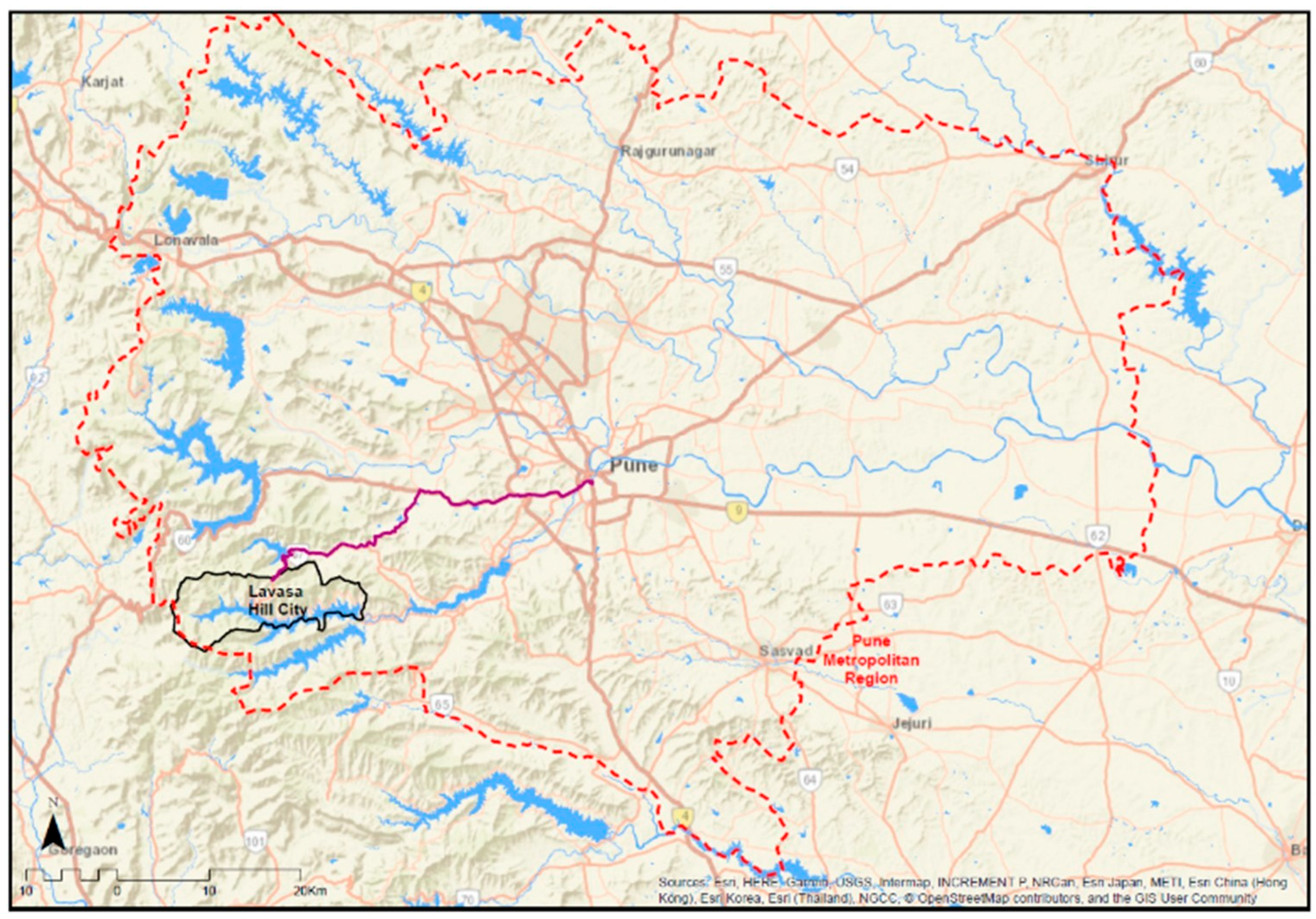

3. Pune Metropolitan Region

Pune Metropolitan Region (PMR) refers to a jurisdiction covering an area of about 6914 km

2 that encompasses the city of Pune and its surrounding hinterlands [

39]. As per the census of 2011, the population of PMR is more than seven million, whereas Pune as a “city proper” is home to about five million people. The city has a long history: it was the capital of the Maratha empire and continues to function as the cultural centre of the state. In recent decades, it experienced rapid urbanisation due to large-scale industrialisation, development of the educational sector, and the flourishing software industry. An administrative authority called Pune Metropolitan Region Development Authority (PMRDA) was formulated in 2015 for managing the urban and regional growth of the Pune Metropolitan Region (PMR) [

39].

The idea of a metropolitan region surrounding Pune had taken root in late 1967. At first, an area of 1605 km

2 with a population of 1.4 million was delineated as a “metropolitan region” and a regional plan was prepared for a tenure of 20 years (1970–1991) [

39]. The plan focused on industrial activities for regional economic development and made a reference to tourism activities around a couple of lakes, forts, and religious centres under the purview of rural planning. The plan was only a guiding document and remained much on paper; there was no designated implementation authority. Only a few minor projects were realised. After years of a policy vacuum, the regional plan was revised in 1997 by expanding its jurisdictional territory to cover the entire Pune district of an area of 15,643 km

2. [

39]. The regional plan of 1997 proposed an “afforestation zone” on hills and lakes with conditional permissibility to a limited number of tourism projects on hilltops, lakefronts, and river banks. Post-liberalisation (since 1991) buoyant economic environment provided the impetus for the development of large-scale tourism destinations [

40,

41,

42] in the region and a provision was made under special regulations for the development of hill stations for tourism. The legacy of hill stations is carried over from colonial rule where the British administrators developed retreats in the mountains to escape from the harsh summers in the tropical climate of India; several such hill stations are now popular tourism destinations [

43].

Tourism was declared a bonafide industry by the state government vide Government Resolution No MTC-0399/C.R.201/ Tourism dated 7th April 1999. The Maharashtra Tour-ism Policy [

44] explicitly stated the government’s intent to cooperate and partner with private enterprises in developing tourism infrastructure at existing and proposed destinations. Private investors capitalised on the opportunity and proposed tourism destination projects to attract domestic tourists from Pune city. Given the terrain of the Pune region, private developers received approval from the state government for the development of five new hill stations in the last 20 years forming part of PMR [

45].

In terms of tourism flows in PMR, two patterns can be identified in the region. The “citybound” refers to visitors coming into the core city. Tourist guides list more than 50 significant tourist attractions in and around Pune city, including the ruins of an old fort, magnificent palatial and colonial buildings, military forts, international ashrams, yoga centres, archaeological sites, and festivals. In 2010, Pune had close to nine million visitors [

46], most being domestic tourists. The other is the “destination-bound” flows where people from the city visit the nearby popular hill stations in the surrounding Sahyadri mountainous ranges including Lonavala-Khandala towards the east (60 km. away) and Mahabaleshwar-Panchgani towards the south (120 km. away). Pune has witnessed a considerable increase in tourism activities because of rapid economic development, rising disposable incomes, prosperity, in-migration, changing demographics, and socio-cultural aspirations, and all this mimics what is generally observed with regard to most cities and burgeoning domestic tourism in India [

47]. For the residents of Pune, tourism has taken the form of “destination-bound” flows to the scenic hinterlands that are easily accessible and serve as day-trip destinations for families to spend quality time [

48]. Of these, the newly built hill towns of Amby Valley and Lavasa have emerged as major tourist attractions and created new patterns of tourism in the region [

49]. Refer to

Figure 1 for the location of Lavasa in the PMR.

4. Lavasa, a Tourist Attraction in the Hinterland

Lavasa is a privately owned hill city developed in the hills and forest areas (spread over 100 km

2 area) around the backwaters of Baji Pasalkar Lake (also known as Varasgaon Lake) in the Western ghats (Sahyadri ranges) about 60 km southwest of Pune. It occupies a peripheral location within the boundary of the PMR. As a multifaceted development, it has been described in many ways—private city, new town, hill city, eco-city, new urbanism, lake city, tourist city, and township [

50,

51,

52,

53]. The multiple meanings and imaginations result partly from the confusing ways in which Lavasa has represented and marketed itself, partly due to its legislative status [

54], and partly due to scholars who critiqued certain aspects of this town [

52]. It was established under the state government’s “Hill station policy’” (notification No. TPS. 1896/1231/CR-123/96/UD-13, dated 3 September 1996), which meant that sustainable tourism would be its main activity. However, subsequently, using other regulatory instruments, this primary use was altered to widen the economic base to include the education, hospitality, and leisure industry to favour its development goals. The master plan of Lavasa covers an area of 40.5 km

2 including nine villages that received approval from the revenue collector of Pune under the regulation of regional plan 1997 and Hill Station Regulations 1997. In 2000, Lavasa Hill Station received “in-principle” approval from the state government enabling the company to get benefits under the industrial policy (that included the purchase of agricultural land beyond the legal ceiling of 22 ha). Over the years, the area under Lavasa expanded and in 2008, a Special Planning Authority status was conferred to Lavasa to perform the planning and regulatory functions of the government.

Figure 2 shows the layout of Lavasa.

In 2000, Lavasa Corporation Ltd. (Mumbai, India) hired US-based planning consultancy firm HOK Planning Group to prepare the master plan for nine villages out of eighteen included in the delineated Hill Station Zone. The plan proposed the creation of two additional major lakes within the submergence of Baji Pasalkar Lake and eight minor lakes in the catchment to provide water supply to the proposed city [

55]. The master plan proposed five towns with distinct architectural characteristics and laid down the procedure to implement and monitor them. The corporation had the vision to develop Hill City with an economy based on the education, hospitality, and tourism sectors. It aspired to be the first and foremost smart city in India built entirely by private investment. Water sports, golf courses, adventure sports, hiking trails, and world-class hospitality were some of the key tourism offerings [

55]. The master plan reserved 42% of the land for nature preservation including nature-based tourism activities. Another 30% of the land was proposed for the development of residential properties including single-family houses, condominiums, services apartments, and social housing. A little less than 4% of the land was allocated for the hospitality sector and 2% of the land for commercial units and offices. A total of 14% of the land was allocated for education, research, and urban amenities in fairly large land parcels [

56]. Lavasa positioned itself as an inclusive tourism destination offering holiday homes to fulfil the leisure aspirations of outsiders and investors.

Lavasa “marketed itself as a new ‘city’ ideal for business, education, hospitality and retirees” [

52]. A few hotels, serviced apartments, and a 1.8 km long lakefront were developed to attract weekend tourists. A major push for business tourism came in the form of a 1200-capacity convention centre, a hotel, and a club managed by ‘Accor’. Three more hotels, a movie theatre, lakefront restaurants, and a water sports facility were added as tourist attractions. The lakefront housing known as ‘Portofino’ with its colourful Mediterranean style façade became a centrepiece. Such investments also caught the fancy of second-home buyers who were interested in owning a holiday home near a lake or in the mountains. Lavasa Corporation constructed and sold over a thousand apartments and villas to such ready clientele [

57]. Many homeowners began to rent their houses to weekend tourists—such rentals were not registered or formal but organised via personal means (and therefore seen as an informal activity). The increased supply of rooms allowed tourists to stay for a longer duration. The town also attracted investment from the Swiss hospitality school, Ecole Hotelier de Lausanne, and Christ University from Chennai. Amenities and facilities including hospitals, schools, bazaars, shopping centres, parks, playgrounds, and sports centres were added [

58]. Several high-profile promotional activities including Lavasa women’s car rallies, Water sports festivals, Dance and cultural events, pre-wedding photoshoots, advertisement films, mainstream feature films, and business events increased tourism. Over a million tourists visited Lavasa Hills annually during its heydays in 2015 [

57].

Lavasa’s spectacular rise to popularity as a tourist attraction later met with a steady decline. Several factors contributed to this but the most significant was a series of environmental lawsuits against the company for allegedly causing irreparable damage to the fragile ecosystem in which it was situated [

52]. The legal battles slowed the pace of construction and the ability to deliver the necessary additional infrastructure for the township. This affected the handling of the promised plots, villas, and much-needed supporting tourism services. The company was under tremendous financial strain with revenue that was far less than the interest amount on borrowed money. Eventually, in 2014, the company filed for bankruptcy under the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) and development in Lavasa stopped. In 2015, the Lavasa Special Planning Authority was merged with PMRDA and Lavasa lost the status of special planning authority. Curtailing of events and promotional activities affected tourism and the image of Lavasa as a high-quality tourism destination suffered a setback. However, the seasonality of natural attractions (lake and mountainous terrain) coupled with quality infrastructure allowed tourists to enjoy the serene surroundings and tourism lingered on. As per order no IA/1007/2023 In C.P.(IB)/1765(MB)2018 issued by NCLT Darwin Platform Infrastructure Limited (DPIL) (a Mumbai-based infrastructure company) was declared as a successful resolution applicant and all the assets of Lavasa were transferred to it. At its peak, the first town of Lavasa named Dasve had just 3000 permanent residents compared to the designed capacity of 20,000. And yet, the making of Lavasa a new hill town in the periphery of a metropolitan region had significant influences on the patterns of urban growth within the region.

5. Materials and Methods

For analysing tourism urbanisation induced by Lavasa, a morphological study was conducted using temporal mapping and direct observations at two of the Lavasa tourism sub-regions: within the Lavasa Hill City, and along the main access, the road connecting Lavasa with Pune city. Before 2000, Lavasa had limited connectivity as only a fair-weather road (designated District Road) connected it to Pune. In 2005, Lavasa decided to upgrade this into an all-weather road under the Build–Operate–Transfer (BOT) scheme of the state government. This new access road developed into a corridor of economic activities related to tourism and thus contributed to regional urbanisation. For morphological analysis, this connecting corridor was subdivided into three segments:

From Pune to Pirangut (a significant industrial town), 26 km.

From Pirangut to Temghar Dam, 16 km.

From Temghar Dam to Lavasa, 8 km.

The data were obtained from the following sources.

Public documents published by project proponents and government authorities till 2019.

Annual Report 2012-13. Issued by Hindustan Construction Co., Ltd., (Mumbai, India) (The parent company of Lavasa Corporation Ltd., (Mumbai, India)), 2013.

Final District Tourism Development Plan for Pune District; Published by Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation (MTDC), (Mumbai India), 2014.

Draft Red Herring Prospectus. SEBI-IPO Report 2014, Submitted by Lavasa Corporation Ltd. to the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), (Mumbai India).

Annual Report 2017-18. Issued by Hindustan Construction Co Ltd (Mumbai, India) (The parent company of Lavasa Corporation Ltd.), 2018.

India Tourism Statistics 2019, published by Ministry of Tourism, Government of India (New Delhi, India).

Interviews conducted from 2021 to 2022.

Shop owners on the Pune-Lavasa Road (N = 1 to 5),

Local villagers (N = 6 to 9)

Officials of Lavasa (N = 10 to 12)

On-site observations during visits to Lavasa from 2005 to 2016.

The semi-structured interview questions to shop owners were formulated to know the locations to run a profitable shop in their village/town, the catchment of their customer base, and the seasonality of their business. We also discussed growth in housing stock and changes in their customer base over the years. Semi-structured interviews using a different set of questions were conducted with local villagers to obtain their perception of housing transformation in their villages. The questions were formulated to find out the availability of non-agriculture jobs, the movement of tourists in their village, and preferred tourist spots. We enquired about reverse migration (outmigrant’s return to their native place), real estate development, and speculative land prices. More specific and structured questions were used in the interviews with Lavasa officials. The interviewees began by narrating the development journey of Lavasa as a tourist destination and explained the challenges it faced. Detailed questions were asked about tourism activities, events, and attractions in Lavasa and their contribution to bringing tourist footfalls. Tourist flows from Pune were understood by enquiring about the night stay and day tripper tourist ratio. Then, we enquired about the other types of business investment Lavasa managed to attract. There were focused questions on the significance of the road connecting Lavasa to Pune.

Every new structure that was built on the access roads and in the surrounding area was indicated as a Point of Interest (PoI). Overall, 354 PoIs or significant instances of urbanisation, induced by tourism activities were identified and mapped along the corridor. The data were analysed spatially, morphologically, and thematically to reveal key learnings on tourism urbanisation in Pune metropolitan region. Since development within the Lavasa site and that along the corridor influenced each other significantly, we discuss both simultaneously. At least three distinct phases can be identified in the growth of Lavasa and the hinterland of PMR.

Stage I: 2000 to 2006;

Stage II: 2006 to 2012;

Stage III: 2012 to 2018.

6. Tourism Urbanisation Induced by Lavasa

6.1. Stage I: 2000 to 2006

In the early years of the project, Lavasa Corporation focused on land acquisition and enabling infrastructure within the city. This included investments in the construction of internal infrastructure, a few hotels, a dam forming a 74-acre lake, a lakefront condominium, a few villas, a city administrative office, and related enabling infrastructure. These developments progressed slowly due to the challenges of transporting material and la-bour that relied on using waterways in Baji Pasalkar Lake and the gravel road that provided access to the site. The Corporation realised the need for an all-weather high-quality road for bringing machinery and resources to increase the pace of development. Lavasa underplayed the proximity to Pune since it wanted to emphasise the accessibility to the tourism destination from Mumbai—an economic centre and a global tourism gateway. Many road accesses were planned to connect Lavasa with the Pune–Mumbai (NH-48) expressway and Mumbai Goa Highway (NH-66), but none materialised due to procedural and intentional delays from the government. Finally, in 2005, the Corporation decided to upgrade the existing access road (that it had been already using) to take heavy traffic. This shifted the attention from the activities within Lavasa to the need for creating a robust movement corridor. A Lavasa official (N10) mentioned, “Substantial time and efforts were spent on identification of possible connectivity to Mumbai-Pune expressway, but we found the Pune-Paud Road to be the most feasible option. Despite unfavourable terms of build-operate-transfer contract, HCC (parent company of Lavasa) decided to develop this road”.

The access road from Pune city was upgraded in segments; the Pune to Pirangut (26 km) segment was completed first. Pirangut was a rural town with few industrial units and was often imagined at the boundary of the Pune urban area. With the new road providing better connectivity, industrial activities proliferated in the case of the Industry–Tourism–Urbanisation nexus [

59]. Existing industrial units began to expand, and newer units started operating with the intention of export-oriented industrial production. The movement of industrial workers triggered housing demand. Being a rural town, the formal housing supply was limited and hence, villagers began to invest in informal labour accommodations. Most of the new constructions were concentrated along the road. The informal weekly bazaar flourished as the road brought more customers. Many small shops, shanties, and street vendors began to appear on the road to sell farm produce from the nearby rural settlements. The weekly bazaar became a permanent fixture and soon transformed into a somewhat semi-formal marketplace. Many industrial units began to build roads to provide last-mile connectivity from the upgraded road and allowed deeper accessibility into the surrounding areas through stray dead-end roads.

Figure 3 marks many of these developments.

A distinct feature along the corridor was the proliferation of “Wedding-lawns”. Wedding-lawn is a colloquial term used for large open plots that are used as a venue for weddings and can host up to a few thousand guests; they have minimal construction including temporary accommodation and green rooms but large areas for gatherings, celebrations, and parking. The wedding lawns are favoured by village landlords and politicians for the extravagant exhibition of wealth during a wedding ceremony. It was not surprising that Lavasa Hill City too found the wedding ceremonies a lucrative business and later promoted itself as a venue for a destination wedding.

In 2006, the completely upgraded road received reasonable traffic flow and was featured in a local newspaper as one of the best roads to travel during monsoon for tourists [

60]. The upgraded road also attracted motorbike riders, adventurists, and tourists as it made the serene hinterland of the Sahyadri ranges and particularly Temghar Dam more accessible. A villager from Mutha Village (N6) mentioned, “We never saw so many bikes and cars in our villages before Lavasa. Now everyone asks for location of waterfalls and trails to the river”. Soon the latent real estate market recognised the availability of better-quality roads and many land parcels were being offered for sale. Towards the end of 2006, after receiving approval for its master plan from the district planning authority, Lavasa was opened for tourists with just a few tourist amenities and leisure spaces. However, the remaining segment of Pirangut–Temghar road did not experience intense commercial activities. For its meandering route across the hinterland, this stretch acted as a buffer of wilderness between Pune City and the tourism destination of Lavasa. With a robust movement corridor in place by 2006, Lavasa was the locus of synergised developmental activities.

6.2. Stage-II: 2006 to 2012

Dasve village was the first to develop among the five proposed towns in Lavasa. It resembled a large-scale construction site where 40 km long internal roads were being constructed. This was the time of rapid construction; Lavasa completed 300 villas, 1000 apartments, and urban amenities like Christel House School, Apollo Hospital, and a bazaar. Three more hotels, a movie theatre, lakefront restaurants, and a water sports facility were added as tourist attractions. The town attracted investment from hospitality and management schools. At that time the management of Lavasa was undecided whether to focus on housing or on tourism infrastructure and eventually did both in equal measure. One of the Lavasa officials (N12) said, “Lavasa offers some of the finest real estates to second home aspirants next to a tourism attraction”. A serious push for business tourism came in the form of a 1200 pax capacity convention centre, a hotel, and a club managed by ‘Accor’. However, the associated advertising campaign mainly emphasised the real estate offers and downplayed the investment’s tourism dimension. Draft Red Herring prospectus [

56] states that Lavasa invested about INR 3500 million (USD 70 million) in the financial year 2009-10 and further invested INR 1900 million (USD 38 Million) in establishing educational institutions like Christ College, Ecole Hotelier de Lausanne, and Christel House School, bringing in about 1500 families and 1000 students. In 2009, Lavasa was embroiled in environmental litigations but, by 2010, Lavasa finally obtained environment clearance (EC) from the central Ministry of Environment and Forest (MoEF), which enabled it to complete villas and apartments and hand them over to the respective buyers.

While within Lavasa, formal tourism facilities were developed, informal economic activities emerged externally in response to the growing influx of visitors. Another Lavasa official (N11) mentioned, “Lavasa has meticulously planned and implemented the tourist amenities, but the urban tourists yearn for raw forest produce served to them by hospitable natives. This is the primary reasons for all the shanties you see on the way”. This was most evident in the selling of forest produce of wild berries and honey by the mountain dwellers who often squatted on scenic viewpoints (mainly in the Temghar–Lavasa segment) and built small shacks over time. Soon to follow were the farmers selling seasonal crops of mangoes, sapota, roasted corn, chicken, and sugarcane in small thatch-roofed shops. Many farmers and villagers made use of such lucrative opportunities and converted a room of their house into a shop, making it a relatively permanent business (mostly seen in the Pirangut-Temghar segment). Such micro-entrepreneurs also began to provide wayside amenities to attract more tourists to their enterprise. This response was markedly different from the way minor businesses in the Pune–Pirangut segment responded to “destination-bound” tourist flow. Though city dwellers were travelling to an upmarket tourism destination, the enroute of informal ethnic gastronomical landscape remained equally attractive.

This stage marked a clear transformation in the informal business of micro-entrepreneurs. First, they turned from a small shanty to a small shop run as a home-based business but soon many became big enough to run a quasi-illegal business and employ migrant workers. Some of the businesses crumbled due to bad management, a few remained home-based but quite a few businesses, especially in the Pune–Pirangut segment, grew into flourishing establishments. The road corridor is now frequented by more and more tourists, leading to the construction of more permanent hotels, lodges, and other leisure activities. In addition, tourists began to explore new places on rivers, farms, waterfalls, and scenic viewpoints all along the way and into the hinterland. Such nature-based attractions existed in abundance on the Pirangut–Temghar and Temghar–Lavasa sections, and progressively they were complemented by permanent tourist facilities. In this context, the Pune–Pirangut section witnessed a higher intensity of urbanisation as the corridor became the spine that provided access to a variety of high-rise flats, farm plots, golf course villas, and hill settlements. These trends are represented in

Figure 4.

A notable change along the corridor was the emergence of five-storied apartment houses in small towns and villages. One of the villagers (N7) from Bhugaon Village said, “Oh yes, so much demand for labour Chawls (labour accommodation with shared toilets) that I have built two more floors over my house. Now we have builders building Pune styled apartments in our village, many of us sold land to them”. Most of these were vertical extensions of existing houses. These houses were occupied by the workers and officers of new industrial units constructed in Pirangut. The houses were quite affordable but devoid of potable water and sanitary services. Soon the businesses catering to vehicular traffic (such as vehicle servicing and fuel stations) appeared along the corridor. The expansion of economic activities in the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors led to a further increase in the resident population.

Several families, students, and workers from the villages along the corridor who had migrated in the past to Pune, Mumbai, and other large cities realised that now they have better employment opportunities in their native villages. The census of 2001 and 2011 marks the trend of reverse migration in almost all villages within Lavasa Hill City and many villages along the corridor. In addition, there was in-migration as large private housing schemes were developed in this region to cater to the migrants who were able to find employment in flourishing industries in Pirangut.

6.3. Stage-III: 2012 to 2018

The stop work order issued by MoEF in 2009 severely strained the cashflow of Lavasa Corporation. The revenue sources dried up and the payment of interest on the loans taken by the Corporation was becoming a very challenging task. After 2012, Lavasa began to lose the trust of funding institutions. The corporation took desperate measures by monetising the properties and re-mortgaging land to obtain some breathing space [

61]. However, the indecisiveness of the company on whether to focus on tourism or real estate became the primary hurdle in financial recovery. After the formation of PMRDA, the status of special planning authority accorded to Lavasa Corporation was revoked and its planning functions were transferred to PMRDA. This move reduced the identity of Lavasa to mere real-estate projects—another township in metropolitan regions. With the downsizing of staff, complete stoppage of development activities, and succumbing to mounting financial pressures, Lavasa Corporation Ltd. declared itself bankrupt and the insolvency process was initiated by the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT).

Despite the demise of Lavasa Corporation Ltd., the destination survived and continued to attract a moderate number of tourists. But now the focus shifted from urbanisation within the destination to urbanisation along the movement corridor. The owner of a streetside eatery (N1) in Khrawade Village said, “Court case has turned Lavasa bankrupt and affected our business but now so many people from Pirangut visit temples and they all travel on this road. Monsoon season brings a lot of visitors to trails and seasonal streams. They all buy water bottles and snacks from my shop”. The corridor was now increasingly flanked by mid-rise apartments, farmhouse plots, golf course villas, and hilltop communities attracting home buyers from middle to high-income groups. The Hinjawadi IT park on the western periphery of Pune offered many jobs, but the housing supply for the IT workers near the workplaces was beyond affordability for many. The Pune–Pirangut segment of the movement corridor successfully attracted homebuyers from such middle-income groups who accepted longer travel distances to avail an affordable house. The presence of middle-income young couples created the demand for quality schools and some of the local schools developed their campuses among the newly emerged group housing. Despite being neglected by a formal policy of urbanisation, the Pune–Lavasa movement corridor now was substantially urbanised with scattered amenities. The pattern is represented in

Figure 5.

The urbanisation along the movement corridor shows three distinct characteristics of development. The Pune–Pirangut section has a very clear identity as a peri-urban part of Pune. Pirangut town and surrounding parts present a case of an overgrown village taken over by industrial units and housing. But most significantly, the development along the Pirangut–Lavasa section of the road attracted tourists by offering an alternative to a formally organised and capitalistic destination. This somewhat complimentary and yet informal tourism space is created due to the strength of informal services provided by natives for tourists seeking the experience of nature discovery and nostalgia for the theatrics of village life.

7. Discussion: Peripheral Attractions and Connecting Corridors

It can very well be argued with some accuracy that the urbanisation instances claimed here were not entirely tourism induced. However, our interviews and observations clarified that most of the urbanisation instances have occurred due to heavy tourist flow from Pune to Lavasa. For instance, one of the shopkeepers (N2) said, “After COVID lockdown many of had to shut down our shop even if the town center shops were open since we were dependent on tourist flow to Lavasa. We are vegetable vendors but we earned well since Lavasa tourists gave better prices to few organically grown vegetables in our farms”. Hence, we assert that such urbanisation can directly be attributed to tourism destinations and needs to be recognised as tourism urbanisation by policy makers.

The case of Lavasa highlights some of the salient features of tourism-induced urbanisation in the metropolitan region of Pune. When natural geographical features such as lakes, water bodies, and mountains determine the boundaries of a region, they also present potential opportunities for tourism to those areas of natural beauty. Initially, a concerted “formal approach” to tourism development is required as illustrated by the various efforts (development of amenities at the destination and development of connecting corridor) of the Lavasa Corporation in creating attractions in the Lavasa Hill City. These efforts were supported by the tourism policy of Maharashtra that encouraged tourism megaprojects in the pristine natural spaces of ecologically fragile western ghats. Lavasa’s development shows that as the “destination” in the periphery matures with its tourism functions, the influx of visitors also triggers a growth of providers of tourism goods and services along the access roads to the destination. Much of this tourism infrastructure is created by the villagers’ en route and can be clearly categorised as informal (as described by Oppermann) and the petite bourgeoisie (as described by Mullins), giving rise to the “strip” of tourism corridor as conceptualised by Mullin.

At least two intersecting patterns in such tourism urbanisation can be identified.

The destination in the periphery represents a formal tourist space because of its formal spatial order (of attractions, accommodations, and infrastructure) and economic services that are necessary for tourism.

The route that provides access to the formal destination, because of its alignment and character, develops into an informal tourist space where one finds that locals offer goods and services to travellers via informal means—roadside stalls (temporary), shanties, local produce, meagre accommodation, and other amenities competing and cooperating simultaneously [

62].

Over time, with increasing tourism flows, many of these services are converted to permanent structures that are easily recognisable and identifiable leading to a ribbon/corridor kind of urbanisation. Although this sometimes has a negative impact on the tourism value of the destination by compromising its unspoiled environment, local communities facilitate the opening of other hinterland areas such as riverbanks, farms, and mountain trails for tourism experiences, creating a constellation of informal tourism spaces. The destination cannot flourish without the route, and the route cannot become viable if there is no tourism at the destination: the interdependencies between the two are very high. However, without the creation of a formal destination such as Lavasa, tourism-led urbanisation would not have taken place. The case example discussed in this paper reasserts the argument that informality is not an anomaly but a key epistemology of planning in Indian cities [

28]. Thus, what started as a destination (with significant impacts on its environmental resources) triggered considerable changes on the route and became instrumental in causing an irreversible change to the socio-economic and spatial fabric of the hinterland. This process is like any other urbanisation that is driven by transportation corridors [

10] but here the formal and informal tourism entrepreneurs [

63] became key contributors.

Lavasa, with its peripheral location, has also helped in reimagining the Pune Metropolitan Region whose western boundary was often visualised as coinciding with the location of Pirangut town. That perceived boundary has now expanded, albeit articulated mainly around the areas of the Pune–Lavasa corridor rather than a natural boundary. It must be noted that Lavasa existed before the delineation of the PMR boundary. These dynamics also indicate the potential of the emergence of a new land mosaic of the Pune metropolitan region, radiating along corridors of movement to other tourist destinations and emerging satellite cities on the periphery of the region.

8. Concluding Remarks

The primary purpose of this paper was to explore the process of urbanisation led by tourism in a metropolitan region. For doing so, it relied on the study of Lavasa Hill City- a tourism destination that lies on the periphery of the Pune Metropolitan Region. This empirical case of tourism urbanisation due to Lavasa in the hinterlands gives some credence to the strip and corridor theory of Mullins conceptualisation and testifies to the simultaneous presence of formal–informal tourist spaces suggested by Oppermann. The paper goes further and conceptualises the interdependencies between destinations and corridors and how they generate distinct patterns of urban growth in the hinterland of a region.

While the findings from Lavasa may be unique, it is not surprising that some of the trends of urban growth resonate with similar examples of tourism destinations that have been recently created in other parts of the country, for instance, peri-urban conurbations at Lonavala hills due to the tourism destination of Aamby Valley City, which is also in proximity of Pune Metropolitan Region. In another Indian metropolitan city of Hyderabad, the creation of Ramoji Film City, a place for filmmaking (like Disney Studios) has generated considerable tourism and is seen as a main agent for peri-urban growth on the eastern periphery of the city [

64,

65]. A similar situation is experienced with Wonderla, a large theme park on the outskirts of Bengaluru in South India (also known as the IT capital of India) where the connecting Mysuru Expressway has seen a spur of building hotels due to significant tourism opportunities [

66]. Likewise, one can also find a few conurbations globally that exhibit a similar process of urbanization in metropolitan regions. For instance, the residents of Galati-Braila in Romania perceived tourism as a viable source of economic development on tourism corridors [

67]. The sale of tourism goods and services helped enhance land value in Songjiang and Lingang New Towns resulting in peri-urbanisation of Shanghai [

68]. Urban sprawl and suburbanisation were quite clearly attributed to the movement of tourists in the Tri-city region—Gdansk, Sopot, and Gdynia in Poland [

69,

70].

Several insights from this case study are relevant, the main being the need to recognise the informal production of tourism spaces by the social and cultural capital [

71] of smaller service providers, which tends to be absent in policy discussions. Quite often the tourism policy relies on tourism enterprises to trigger economic development at the formal tourist destinations and hence anticipates urbanisation to remain limited to the destination and its immediate surroundings. The case presented in this paper provides evidence that the scale and peripheral location of tourism destinations can induce ribbon development on the connecting corridor between the tourist destination and the gateway city. In India, tourism destinations were never imagined to be a generator of urbanisation in metropolitan regions. Successive regional plans of PMR are a testimony to this understanding. Ribbon development or corridor urbanisation is not a new phenomenon—it occurs quite regularly on the periphery of a metropolis but a conscious acknowledgement of these processes and their mainstreaming in planning decision making is necessary for the sound growth of the region.

Regional connectivity becomes imperative when policy encourages entrepreneurs to create new tourist destinations. Hence, many tourism destinations emerge along the existing commuting corridor. These corridors improve the reach of the citizens from the gateway city into its region, giving rise to new city regions and expanding the imagined boundary of established ones. The case urbanization on the corridor connecting Lavasa to Pune exhibits the mosaic of urbanisation. Here, the city (through the day trips of citizens) reached the rural hinterland and the hinterland served as a resource pool to provide tourism services, strengthening the connection of the city to its region. Therefore, the Foreman’s argument that the region is defined by the burgeoning culture of the urban population receives support from this case. This phenomenon is quite different from the ribbon development evident in many city regions resulting from the movement of the rural population to the city for economic purposes.

This case of Lavasa points to some generic trends related to tourism urbanisation, but the spatial configurations that are illustrated through spatial-temporal analysis indicate some unique transformations. First, the corridor that connects to a formal tourist destination in the fringe, is largely populated by tourism enterprises of an informal nature and run by families from the surrounding areas. Second, these informal enterprises have helped to open the hinterland for more leisure-oriented tourism activities of day-trippers from the city, a trend that has significant implications for transforming the nature and ecology of the peripheral areas. Third, the project-driven enclave-based approach to developing Lavasa as a tourist destination has provided an important lesson for understanding regional transformation—it has permanently changed the ecosystem in the periphery. The third lesson is supported by the qualitative data of stagewise urbanisation in the tourism destination of Lavasa provided in this paper. Since Lavasa expanded and opened the notional periphery of the Pune region, the natural features which once mused just the adventure lovers, came in reach of family outings and day trips. That is how the tourism destination in the periphery of a metropolitan region permanently changed the ecosystem.

In following the focused socio-spatial aspects of urban change influenced by tourism to Lavasa, this paper has glossed over some of the other aspects that might also have had some important bearing on such transformations. For example, the dynamics of the political–economic system and the allegations around corrupt practices of governance and planning in which Lavasa was developed may have had a significant influence on its image, popularity, and decline [

54]. Similarly, the trend of day trips and day trippers is situated in a wider set of socio-economic conditions of prosperity, disposable income, working class, and accessibility [

48]. The opening of Lavasa as a destination would have been just in the right time and space for such leisure-oriented tourism that has become a sort of social phenomenon [

53]. More research on understanding the motivation and behaviour of visitors and tourists at Lavasa would really help in forwarding a nuanced understanding of such burgeoning tourism that is fast becoming a reality in Indian cities.

Finally, like most exploratory studies, this paper also has its limitations. While it has managed to highlight the role of a destination and corridor in tourism urbanisation, many other aspects remain to be explored. While the tourism process was at the centre, another study would be necessary to understand the success of Lavasa using the lens of tourist motivation and experiences. Similarly, the geographical setting of this case is such that the access road is on a fairly flat terrain, except for the real steep slopes closer to only Lavasa. The nature of urban growth would have been quite different if this was a more winding road for a greater length (something common with natural hill stations), and these differences and similarities would make fascinating research. While discussing the urbanisation challenges, this study sidestepped the environmental impacts of tourism in the region—both negative and positive. For example, because visitors are able to see how bamboo is used in the hinterland, they become more aware of its sustainability as a building material [

72]. A complete assessment of tourism-related environmental impacts is a must in the case of destinations such as Lavasa that capitalise on their natural settings for tourism. Nonetheless, raising such questions would not have been possible if this paper had not offered a nuanced understanding of the fundamental processes of tourism urbanisation in a metropolitan region.