1. Introduction

In Serbia, there are several touristic mountains, such as Kopaonik [

1,

2,

3], Tara [

4,

5] and Zlatibor [

6,

7]. According to RZS [

8], compared to other tourist-affirmed mountain areas, they are recognizable even to foreign tourists. There are mountains where tourism is on the rise, such as Fruška gora, Stara planina [

9,

10], Zlatar [

11,

12], etc. However, through field observations, mountains that were completely unrecognized by tourists or had minimal affirmation in terms of tourism were found. In the absence of a human presence, the quality of the environment is preserved. For tourists, this is the most attractive feature [

13,

14], especially when it comes to tourists for whom environmental sustainability is important.

The affirmation of mountains by tourists is often a process that takes many years [

15,

16,

17], requiring numerous investments and significant efforts to preserve the quality of what is on offer [

18,

19]. Fast tourist affirmation is desirable in order to exploit the financial benefits as soon as possible [

20,

21] and, in this way, engage, preserve or bring in a new population [

22,

23]. A new population also means the beginning of revitalization processes [

24], which are necessary for the depopulated mountain areas that are discussed in the scientific literature [

25,

26,

27]. Fast tourist affirmation can only be feasible if the new tourist location relies on the nearby potential. The tourism industry is always in need of new and original content [

28]. Searching for such a site means searching the vicinity of already established sites and larger settlements, whose size already guarantees the presence of tourist infrastructure and suprastructure.

The desired mountain was recognized in the local environment of one of the authors. The motivation to become acquainted with the homeland from a professional point of view led to a fascination with its historical sites, but also the observation that these sites were often not associated with the name of the mountain in whose foothills they were located. Recognizing the possibility of organizing sustainable tourism, the authors felt the need to prove that it was possible.

The context of sustainable tourism can be found in the definitions outlined by the WTO [

29] and the work of León-Gómez et al. [

30]. In their work, Guo et al. [

31] provide a historical overview of how the knowledge of sustainable tourism has been enriched. Here, they write that sustainable tourism emphasizes the long-term coordinated development of tourist activities with society, the economy, resources and the environment. Works on the topic of sustainable tourism have determined and directed the focus of research in this work. The essential ideas of well-known literature such as Aronsson [

32], Weaver [

33] and Harris et al. [

34] are integrated into the work, but also the latest thoughts of Vuković [

35], Wagenseil [

36], Gogitidze [

37], Trišić et al. [

38], etc., on trends in sustainable tourism. Due to the work of Della Corte et al. [

39], in addition to proving an ecological balance, the work also seeks to improve the competitiveness of the surrounding attractive tourist areas. The work of Streimikiene et al. [

28] inspires thoughts on strengthening the competitiveness of the destination and on the use of new technologies when studying and paying attention to the demographic characteristics of the population, which is essential in organizing tourism in a certain area. Among others, Agieivaah et al. [

40] emphasize that innovation and new ideas provide a competitive advantage and open new opportunities in tourism. Stolovi Mountain, near Kraljevo, has the potential to offer a new experience. The tourism potential of Stolovi Mountain, due to its untouched nature, opens up new and furthers existing opportunities for future development. Thus, this mountain can be considered an ideal site for sustainable tourism. Kraljevo and the surrounding area, with its infrastructure and superstructure, is recognized as a place where the needs of modern tourists can be met.

The goal of the research is to show the possibilities that small, unaffirmed mountains, such as Stolovi Mountain, can provide. This paper aims to analyze the possibility of affirming tourism on the unaffirmed Stolovi Mountain in order to make it ecologically, economically and socially sustainable. Its achievement should serve those who deal with development strategies and those who work to balance regional development, given that, as Petrović et al. [

41] argue, Serbia is unevenly developed on the regional level. The exploration is enriched by designing a new method to contribute to the harmonization of regional development in Serbia. The research objective is to examine to what extent Stolovi Mountain is known for the already established tourist attractions located in its foothills. The primary focus of the research is to show that, in Serbia, tourism on unaffirmed mountains next to large cities is possible and sustainable.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

It is important to highlight the scientific publications that inspired and initiated this research. Aničić and Veličković [

42] discuss the issue of well-being in Serbia and the ways in which it can be improved through local development, i.e., reducing regional differences caused by uneven regional development. Furthermore, Bošković et al. [

43] note that mountain regions should be considered as the areas that are most important for the development of tourism in the Republic of Serbia. In the past, tourism development was not consistent with the principles of sustainable tourism. Mountains have ecological, recreational, educational and scientific value, and they need to be used in a sustainable manner [

44]. Sustainable tourism does not only imply nature preservation or socially responsible business. The theoretical definition of sustainable tourism involves the dimensions of economic, social and environmental protection [

28]. Such tourism is experiencing a phase of deep metamorphosis, mainly related to the demand for the integration of different meanings of the concept of sustainability, i.e., economic, environmental, social, etc. For example, see [

45]. This initiates the search for alternative destinations in the surroundings of established mountain tourism locations. The 4As of [

46] (attraction, accessibility, amenities and accompanying tourism components in the area) are necessary for any form of tourism in rural areas. Nepal and Chipeniuk [

47] mention six resource characteristics specific to mountains, which include diversity, marginality and difficulty of access, fragility, niche and aesthetics. It is argued that these characteristics are unique when it comes to mountain regions and, as such, specifically imply mountain recreation and tourism development. Recent research by Hui et al. [

48] deals with the other ‘extreme’ called tourist cities.

The scientific literature contains facts that are recognized and can be tested in the case of Stolovi Mountain. Cities can benefit from rural development. Thus, Xu et al. [

49] state that economically backward cities and large cities can serve the surrounding traditional villages by establishing tourist distribution centers, thereby driving their emergency development. In the Far East, according to Michaud and Turner [

50], there are mountain sites near cities (e.g., Lijiang in Yunnan) that attract millions of tourists through the beauty of nature, which can be viewed with the help of cable cars or drones. The authors of [

51] discuss the development of the accommodation capacity of the population that inhabits the mountain area, for the development of tourism but also for local development. The main driving factors include the traffic conditions, tourism self-organization mechanism, natural geographical conditions, political factors and local residents’ willingness to evolve. According to Mitchell [

52], in order for tourism sustainability to be achieved, the existing patterns of power and unequal development must be breached through the involvement of local communities in tourism development. Moreover, Debarbieux et al. [

53] mention the problem of attracting the population and tourists.

There are numerous examples of the damage done to mountain settlements caused by tourism [

44]. In the absence of the movement of tourists on Stolovi Mountain, it is crucial not to deviate from sustainable tourism, which is related to the concept of green tourism. Green tourism (GT) considers the existing and future needs of the environment, businesses, people and visitors. The ‘green’ concept can be applied to every type of specialized tourism industry, i.e., large and small, rural and urban [

54]. Green tourism tries to protect the green environment by adopting various green consumptive activities. This is mainly applied in order to achieve social, economic and environmental sustainability [

55]. Milićević et al. [

56], for the more established mountains in the region, recognize vitality in green forms of tourism. The work of Pan et al. [

57] also provides concrete solutions without which there is no green economy. Therefore, every consideration should take into account the preservation of nature, without which every activity, including tourism, is unsustainable.

In order to achieve the goal of sustainability research, hypotheses were set. The main hypothesis was as follows: the sustainability of tourism on the mountain is possible if there is a larger settlement in its foothills (H0). The three supporting hypotheses were as follows:

H1: The quality of the environment on Stolovi Mountain is ecologically sustainable.

H2: Starting tourist movement on a mountain, such as Stolovi, near a larger settlement is socially sustainable.

H3: Organizing tourist movements around Stolovi Mountain is economically viable.

3. Study Area

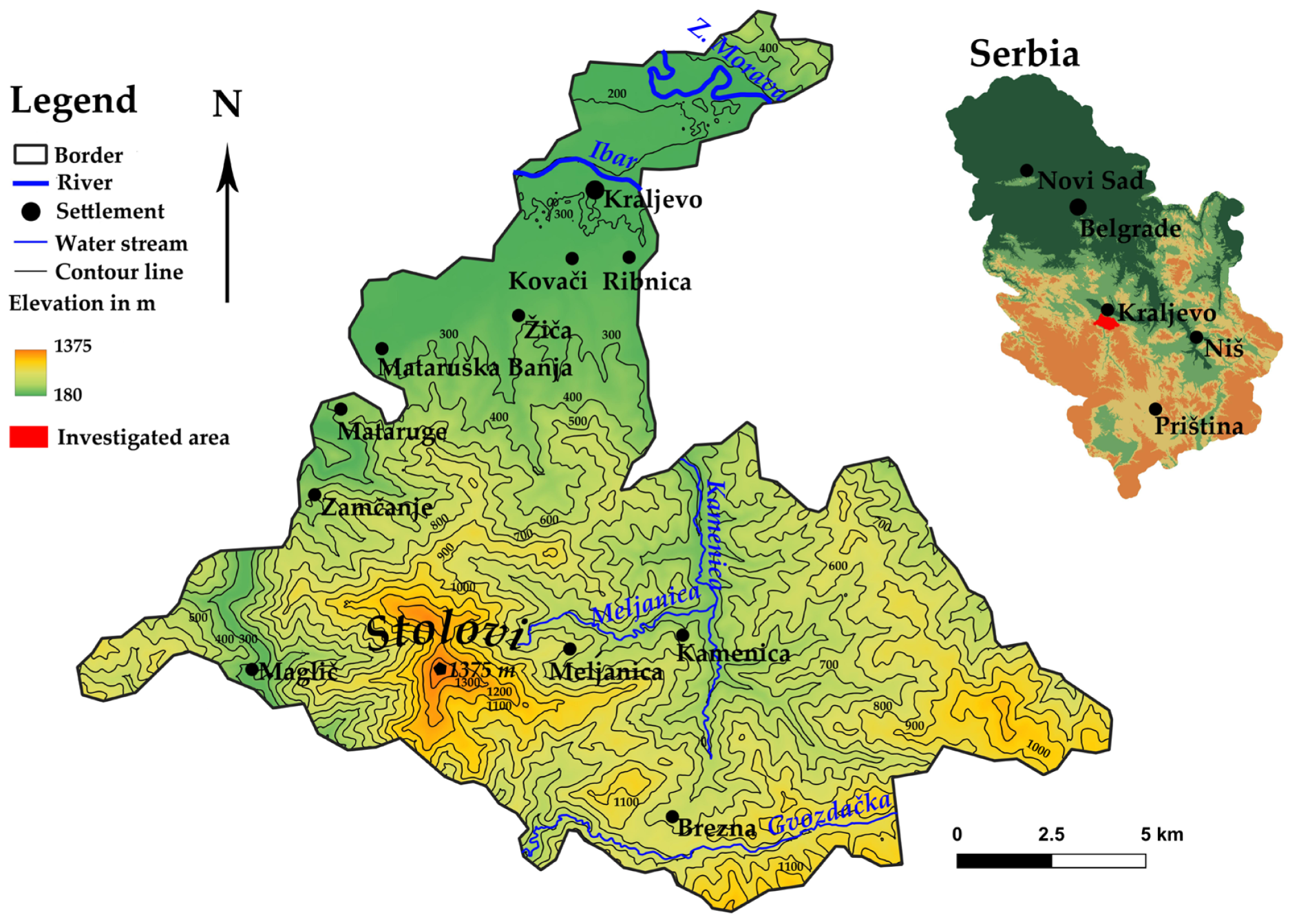

The presentation of the facts about Stolovi Mountain serves to justify the selection of this particular mountain. Stolovi Mountain rises above Kraljevo, a settlement with 64,175 inhabitants according to the 2011 Census [

58]. The preliminary results of the 2022 Census show that 111,690 inhabitants live in the city of Kraljevo [

59]. Brezanska River, a tributary of the Ibar River, flows from the southern side of Stolovi Mountain and encircles the mountain on the western side [

60]. The eastern border is clear, because it coincides with the course of the Ribnica River. In the north, Stolovi descends towards the settlements of Mataruge, Mataruška Spa and Žiča, and towards the city of Kraljevo (

Figure 1).

The two highest peaks are Usovica (1375 m) and Čiker (1325 m). The highest peak is located on the highest mountain ridge, which stretches north–northwest and south–southeast. The relief is filled with slopes and ridges (

Figure 1). The massif of Stolovi Mountain stretches like a star. The slopes of Stolovi Mountain descend steeply towards the Ibar River. The northern side is tamer because the Stolovi massif slopes slightly. The separate mountain masses are called Oštra Glavica, Strmenica, Vitoš and Ozren. The mountain is crossed by Zamčanjska River, Žička River and Crna River, which give it the shape of a star. Stolovi is a dry mountain, due to the fact that it is composed of permeable serpentine rocks. In dry summers, the springs and watercourses are visibly weakened. The topographic map reveals the locations of the springs and traces the paths of the field research. It is important to identify where on the mountain people can drink clean spring water. However, the literature also mentions mineral water springs [

61].

Stolovi Mountain is rocky and one can see broken parts of rocks with little vegetation. There are a number of exposed rocks and slopes with grass. The autochthonous variety is the Ibar lilac. It blooms luxuriantly in the gorge, but also deep in the mountains, next to the Meljanica River. The flat surface is separated from the rest of the mountain by the long and deep valley of the Meljanica River, which flows into the Ribnica River near the village of Kamenica. On Stolovi Mountain, there is a small area covered by oak and beech forests. The area covered by forest in the analyzed territory amounts to 55.5%. According to the authors’ findings, Kamenica, Mataruge, Zamčenje and Brezna are the areas with the largest territories covered by forests. The total forested area covers 56,524,960 m2.

3.1. Tourist Potential of Stolovi Foothills

The most noticeable localities in the foothills of Stolovi Mountain are also known throughout Serbia and beyond. For example, within the western foothills of the Stolovi Mountain massif, there is a medieval fortress, Maglič (

Figure 2(4)). It has been named a cultural monument of exceptional importance [

62], because it dates back to the 13th century [

63]. In the northern foothills, Žiča Monastery and Mataruška Spa are located. Žiča Monastery is a cultural monument of exceptional importance, built in the first half of the 13th century (

Figure 2(5)). The fact that seven Serbian rulers were crowned in it speaks of its importance [

64]. Mataruška Spa has existed since 1898, and, with its 42 °C water [

23], it is used for the treatment [

65] of rheumatic, neurological, gynecological, post-traumatic diseases and diseases of the peripheral blood vessels (

Figure 2(7)). Near Mataruška Spa, on Lojanik Hill, there is a ‘stone forest’, a natural phenomenon that covers 15 hectares. These are deposits and remains of calcified wood from the Paleolithic. Some deposits are approximately one million years old [

66].

Since 1990, the event called ‘Happy Descent’ in Stolovi Mountain has been organized in Ibar Valley, i.e., in the western foothills of the mountain [

67]. According to Jovanović and Delić [

68], ‘Happy Descent’ is a sports, recreational and ecological event that has a national character and gathers approximately 20,000 participants and visitors (

Figure 2(3)). The event is characterized by unusual and interesting vessels made of wood, bottles, Styrofoam and car tires. They must be durable in order to endure a 27 km long journey through the rapids of the Ibar River, from the medieval city of Maglič to Kraljevo (

Figure 2). The high quality of life in the foothills of Stolovi Mountain, which contributes to its tourist attractiveness, can be shown by the fact that, according to Terzić [

69], the city of Kraljevo during the COVID-19 pandemic had a very low level of infection in relation to the number of its inhabitants.

3.2. What Is Attractive for Tourists on Stolovi Mountain?

The largest tourist attractions are, in addition to the beautiful views, the daffodils and wild horses (

Figure 2(2)). Stolovi Mountain is a hiker’s paradise. The mountain can be climbed from several sides. The most accessible trails are from Žiča and Kamenica, which are well arranged and marked. They are maintained by the Mountaineering and Skiing Society, ‘Gvozdac’, from Kraljevo. The trails from Maglič and Dobre Strane are also in operation and are used. However, they are not recommended for hikers because they are overgrown by weeds. The locals claim that there are a great deal of poisonous snakes on this stretch towards Stolovi Mountain.

There are grass meadows in the site called Ravni Sto. In May, wild daffodils appear, which have become the symbol of Stolovi Mountain. Although daffodils also exist on other mountains in Serbia [

70,

71], it can be said that these are the most famous. On the basis of the appearance of this flower, since 1965, the manifestation ‘In Pursuit of Daffodils’ has been held. It is organized by the Mountaineering and Skiing Society, ‘Gvozdac’ [

72]. The procession starts the hike from the village of Kamenica and climbs to the top of the mountain. In the glades, one can enjoy the white fields of wild daffodils. All trails are marked. The length of the ascent can be 21 km long (longer path), during which a height difference of almost 1000 m is experienced, or it can be 11 km long [

73]. In any case, the climb is gentle and easy to complete. According to Jakovljević [

74], more than 2000 people attended this event in 2022.

A herd of semi-wild horses has been permanently living on the slopes of Stolovi Mountain for more than 30 years. At first, tame horses were brought by the owners, i.e., people who lived in the villages below the peaks of Stolovi Mountain, so that they would have less work around them during the summer (

Figure 2(2)). On the mountain, the horses ran freely, and they had food that was fresh and healthy. As time passed, the horses were left for longer periods of time, sometimes during the winter. The horses became independent and began to acquire the characteristics of semi-wild horses that do not need to rely on humans to live.

Horses are not aggressive. There have been recorded cases of wolf attacks during the night and in winter. It has been noticed that horses always sleep on a hill (not in a valley) and head to head. Through breeding, the herd has increased to reach the figure of fifty horses. According to Milenković [

75], the most famous horse on this mountain is the stallion Moro, who has been the master of his herd for about fifteen years. Those who follow these horses state that there could be more of them if the winters were not so harsh and cold. Sometimes, the horses die or run away. There are also horses that have their own owners. These horses are chipped, and the owners visit to groom, feed and observe them. Some of the owners are members of the Association of Horse Lovers, ‘Stolovi’. When the winters are severe and strong, the roads to the horses are snowy and inaccessible. Thus, food cannot be delivered to the horses. For example, in the winter of 2012, food was delivered to the horses using a helicopter [

76]. The enthusiasm of the individual is the only certainty in the hands of the members of the Association. Every Christmas, people from the Association bring down the most beautiful horses, harness them to carriages and walk them through the streets of Kraljevo [

77]. This unique parade is a beautiful event, a favorite among the people of Kraljevo. Wild nature deserves the attention of domestic and foreign tourists and visitors.

The population in the villages of Stolovi Mountain is dropping off. Many young people do not return to the mountain after graduating.

The idea of raising the cross on Stolovi Mountain was conceived by the Mountaineering and Skiing Society, ‘Gvozdac’, from Kraljevo. The location, the place of Usovica on Stolovi Mountain, is owned by a public company, ‘Srbijašume’, at an altitude of 1375 m (

Figure 3). The procedure began at the end of 2007, when the public communal company ‘Roads’ from Kraljevo started building the road and constructing access to the very top of the mountain for the delivery of materials, in the fall of 2010. The works were stopped due to the earthquake in November 2010 and major floods in 2014 [

78]. The cross was built with donations obtained from locals. The works continued in 2017. In May 2020, the cross, weighing 16.5 tons, was raised. The cross is 33.5 m high, a number that represents the years that Isus spent on Earth [

79]. The cross is dedicated to the Lord, Saint Sava and other members of the Nemanjić family for the jubilee, i.e., eight centuries passing since Serbian Orthodox Church became autocephalous. At the same time, those who died in the battles on these mountain ranges, defending the retreat to the Serbian army and civilians in the First World War of 1915/16, are also honored [

80]. The cross is visible from a great distance; visitors can see it upon approaching Kraljevo from all directions.

4. Methods

Why was Stolovi Mountain chosen? Stolovi Mountain was chosen for several reasons. The first was its good geographical position. Stolovi Mountain is located in the central zone of the Republic of Serbia. It is accessible by several traffic routes of different degrees. The busiest road route is the West Morava Valley. This is the route that connects West Morava Valley with Eastern Serbia and it is in the phase of transformation into the A5 highway [

81]. A part of the Ibar Highway, i.e., the state road M22, passes through the west of Stolovi, which is located in the composite valley of the Ibar River [

82,

83]. For centuries, a road connecting the south and the north has been routed through the Ribnica Valley [

84]. Less than 20 km from Stolovi Mountain is Morava Airport [

85], where international aircraft can land [

86], which represents great potential for all foreign tourist movement. In addition, in the northern foothills of Stolovi, Kraljevo is located, which is a city of more than fifty thousand people, who live and work in it and its surroundings. In addition to Kraljevo, there are well-known tourist attractions in different locations in the Stolovi foothills [

87]. The most famous are Mataruška Spa, a hydrological–balneological site [

88]; Žiča, one of the most important sacred buildings of the Serbian Orthodox Church, dating back to the 13th century [

89]; Maglič, one of the most famous medieval fortifications in Serbia [

90]; and the geological phenomenon called the Stone Forest [

87].

Another reason is its morphometry. Stolovi is a hypsometrically low mountain (1375 m a.s.l.) and a small one, concerning the surface that it covers [

91]. The surface of the mountain is 152 km

2, and its circumference is about 53 km [

92]. If the length of the marathon is taken into account [

93], which can be run in less than 4 h [

94], even for enthusiastic walkers, the mountain can be visited in one day. As such, Stolovi Mountain cannot be compared to the developed mountains in terms of tourism; rather, it can be perceived as a mountain that can offer some complementary content.

The third reason is represented by the consequence of the absence of serious tourism affirmation. The professional literature does not record tourist trends. Petrović et al. [

89] mention Stolovi Mountain, near the Žiča Monastery, as one of many other mountains. This fact corrected the originally designed structure of the work. It imposed the need for research that demonstrates the extent to which the local population, as well as the population that does not live in Kraljevo and its surroundings, knows what is on the mountain and in its foothills.

4.1. GIS and Remote Sensing Methodology

All digital cartographic analyses were approved using two open-source GIS software programs, the Quantum Geographical Information System (QGIS 3.12) and the System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses (SAGA 8.2.0). Satellite imagery was downloaded as EarthData from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and from the Landsat 9 satellite mission at 30 m resolution [

95]. The digital elevation model (DEM) had a resolution of 30 m, but, when processed in the GIS software QGIS 3.12 and using the clip raster by mask layer function, the resolution was set to 10 m [

96]. The area of Mt. Stolovi was determined using the official boundaries of settlements in the Republic of Serbia. The ten settlements were analyzed together with the analysis of the relief characteristics. The methodology used in this research was divided into two parts. The first part concerned the selection of digital and analog data within this research. After the precise determination of the geographical coordinates (longitude, latitude, altitude), the next step was the determination of the locations of the tourist sites in the study area. The numerical methods of GIS were applied with QGIS 3.12 and using functions such as clip, slope, aspect and zonal statistics. These functions were used because they allow for the accurate estimation of tourism sites with natural data such as relief properties and their characteristics [

97]. The next step was to separate the digital and analog data. For this purpose, SAGA 8.2.0 and QGIS 3.12 were used, as well as remote sensing features such as pixel analysis, semi-kriging and supervised classification. In particular, these methods were used to determine forest areas in the analyzed area [

98]. These methods are also useful for the analysis of forest characteristics. Another advanced method used in this research was the random forest algorithm.

4.2. Other Methods

After the inevitable consultation of literature sources [

12,

41,

42,

43,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107], the research continued with field observation. It was important to determine whether people knew about Stolovi Mountain, where it was located and whether there were any historically important and tourism sites in its foothills [

60,

61,

63,

64,

67]. Surveys were indispensable in order to prove the validity of the research. It is illogical to discuss tourism in insufficiently known localities. A pilot study was conducted among geography students from the University of Novi Sad and the University of Pristina with a temporary center in Kosovska Mitrovica. Since, after interviewing more than 100 respondents, a number of very similar answers were observed, the research was extended to include other Serbian residents (

Table 1). One of the requirements was that the respondents were not from Kraljevo and its surroundings.

The second questionnaire was given to respondents who lived in Kraljevo and its surroundings. In it, the questions were adapted in order to check how informed the respondents were about their local environment. In addition to the questions aimed at determining whether the domicile population was aware of the tourism value in the foothills of Stolovi Mountain and on its slopes, questions regarding sustainability were also asked. The most important issues were issues of environmental quality, followed by issues of the relationship of the local environment with the development of tourism in Stolovi Mountain.

Some questions were close-ended, concise and direct. Some answers were given using a five-point Likert scale, including options such as totally disagree, disagree, neutral, agree and totally agree. The respondents had to choose only one option for each question. These responses were analysed using descriptive statistics. Differences in responses between sociodemographic groups were sought using the T-test (at the significance level p < 0.01) and one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA, at the significance level p < 0.01; F ≥ 3.47).

For some questions, an in-depth interview had to be conducted. Respondents of proven competence were chosen (people who lived near the mountain, people from Kraljevo and people who decided in which direction the development of this mountain would take place) and all of them were from the territory of the city of Kraljevo. The interviews with respondents lasted, on average, 10–15 min. Interviews were conducted in a physical format ‘face to face’ or by phone. The in-depth interviews were conducted during the summer of 2023, after the end of the survey. During the process, the interviewer made notes and observations to facilitate the analysis of the data. The opinions of the local population helped to interpret the answers received. More precisely, answers were sought from people who organized hiking trips to Stolovi Mountain or events in their foothills. Respondents gave their opinions on the set topics, thus contributing to the objectivity of the research [

108]. The most useful and expedient answers were selected during the desk research, while the most constructive answers are given in the paper.

The interview aimed at discovering facts about the locations of the sources and their characteristics. It was also a means of discovering what the local population considered to be the greatest sources of tourist potential of the mountain.

Through the interviews, information was gathered about numerous legends that have been retold for centuries. This is where the qualitative analysis was conducted. Namely, first, a plan was drawn up about who must be examined and on what topics [

109]. During the conversation, depending on the flow of communication, the outlined plan had to be corrected. The exploratory and explanatory strength of the research determines the value of qualitative research [

110]. As Caudle [

111] stated, the team brought all their skills, knowledge, experience, creativity and work to the analysis of the answers. During the analysis, answers displaying frivolity, sarcasm and incompetence were rejected. The obtained information is presented in the paper precisely, i.e., it was confirmed by several respondents.

Only the local population could give answers concerning the types of pollution and its extent. Some of the authors of the paper attended all the manifestations that were organized during the research period, but only the local population could reveal how these manifestations used to appear and how they differed from the previous ones. Through an in-depth interview, the ways in which the local population was ready to participate in the tourism affirmation of Stolovi Mountain were investigated. Information on the facilities and locations of tourist infrastructure and superstructure, etc., were gathered as well.

The obtained results are presented using a table or a map. The territory shown is a set of settlement atars (basic administrative units) that are located in the foothills or on the slopes and peaks of Stolovi Mountain. Finally, the last method of this research was descriptive qualitative research based on an exploratory study, i.e., the data obtained by qualitative and exploratory methods were described.

The Raosoft [

112] calculator was used to check the sample size appropriateness for respondents who lived in Kraljevo or its surroundings and for others who did not live there. Accordingly, for the population size of 6,647,003 [

59] (the total population of the state), at a confidence level of 95.0%, a sample of 385 respondents was recommended. Taking into account the fact that the investigation covered 550 examinees, of which 520 filled in the questionnaires correctly (94.5%), the sample was considered representative. The sample was not stratified. The respondents were reached through social networks or directly, through personal contact, on the streets of the settlements of the Republic of Serbia.

For the population size of 110,196 [

59] (the total population of the city of Kraljevo with all its settlements), at a confidence level of 90.0%, a sample of 270 respondents was recommended. Taking into account that the investigation covered 300 examinees, of which 270 filled in the questionnaires correctly (90.0%), the sample was considered representative. According to Babbie [

113], a response rate of 70% or more is a solid sign of scale acceptability.

5. Results and Discussion

The results consist of three parts. The first part contains answers from the respondents who did not come from Kraljevo and its surroundings. In the second part, we include answers from the people of Kraljevo and those from the slopes of Stolovi Mountain, its foothills and its surroundings. In the third, we include the results on the possibilities of practicing certain types of tourist movement on certain mountain parts based on the findings of the GIS analysis on the morphological characteristics of Stolovi Mountain. The fourth part considers the opinions of the local population about the aspects that tourists may find attractive on Stolovi Mountain.

Before presenting and analyzing the results of the survey, two facts should be pointed out. Both surveys and an in-depth interview were conducted during July 2023. Some of the respondents were asked about the topic, the idea of exploration and the ultimate aim of the research. Some respondents expressed enthusiasm. As the respondents in the first survey came from different parts of Serbia, the idea of the survey also extended to their areas. Proof of this can be found in the media, which publish non-scientific texts more quickly. In particular, during August 2023, Blažević [

114] and RINA [

115] wrote about the possibility of developing tourism on mountains that are not well known to tourists, as well as about nearby sights that can be connected to them.

5.1. Answers from Respondents Who Did Not Live in Kraljevo and Its Surroundings

The answers from respondents who did not live in Kraljevo and its surroundings illustrate to what extent the people were familiar with the localities in the immediate vicinity of Stolovi Mountain. This group of respondents answered questions concerning the reasons for visiting the mountain, which until now has not been affirmed as a tourist destination.

Women were more accommodating than men. The relative majority of respondents were between 40 and 49 years old. The absolute majority of respondents had a high school diploma (

Table 1). According to the data of the SORS, the situation in Serbia is identical in terms of the sex–age situation as well as the educational structure.

In his book, Light [

116] indicates how important identity is in recognizing a tourist destination. All respondents who were not from the territory of Kraljevo and its surroundings knew about localities such as Mataruška Spa, the medieval fortress Maglič and the Žiča Monastery, but they did not know that they were located in the foothills of Stolovi Mountain. Widely known localities overshadow others with their age, exceptionality, importance, etc. An analysis of all available materials in electronic and paper form about the localities in Stolovi foothills concluded that Stolovi is not mentioned anywhere. These localities are recognizable and their location is related to the settlement of Kraljevo and the valley of Zapadna Morava, rather than to Stolovi Mountain. The affirmation of several territorially close localities is rare in Serbia. The respondents also stated that these sites are located near the city of Kraljevo. However, on average, every other person knew that they were in the foothills or on the slopes of Stolovi Mountain. This was to be expected, due to marketing. The result of the survey was also disappointing as, when asked to name a mountain near Kraljevo, 106 (20.4%) respondents did not name Stolovi Mountain.

In order for Stolovi Mountain to be recognized as a tourism site, the identity of these localities must also be linked to the mountain. Geolocating Maratuška Spa, the Žiča Monastery or the medieval fortress ‘Maglič’ next to Stolovi Mountain can only enhance the tourist offer of the city of Kraljevo and the other mentioned localities. It would provide significant ‘tailwind’ for Stolovi Mountain to be recognized as a tourism site. Everyone who discussed the cross, the horses and the manifestation called ‘In Pursuit of Daffodils’ also knew that they were located or organized on Stolovi Mountain. Therefore, considering that these are familiar aspects, they should be associated with Stolovi Mountain. However, few people had heard of the Stone Forest. Moreover, of the small number of those who had heard about it, some of them connected this natural phenomenon to Stolovi Mountain (

Table 2) but six times more of them actually knew the name of the site (Lojanik).

The respondents provided the reasons that people would visit the mountain, which until now has not been affirmed as a tourist destination. The aspect with the greatest tourist potential was identified as the preserved and untouched nature, and the search for new landscapes, sights and peace and quiet. Some of the answers identified recreationalists who would be satisfied with a walk in clean, quality air. The rest cited curiosity, intrigue and affinity for novelties.

There were also answers that indicated that unaffirmed mountains were synonymous with adventure tourism. Some of the respondents saw it as a source of new knowledge and experience, or as an excellent place to practice hiking or orienteering. One respondent wrote that he would visit any unconfirmed tourist destination if the offer was financially favorable and if he/she had good company. There were those who saw it as an opportunity to obtain tea plants. The most original comment was made by a young interviewee who described mountains that are not established by tourism as perfect places that are not light-polluted but perfect for observing the night sky.

5.2. Answers from Respondents Who Lived in Kraljevo and Its Surroundings

The answers from respondents who lived in Kraljevo and its surroundings helped to reveal the level of knowledge about what can be found in the foothills of the mountain and its slopes. Respondents revealed how often they visited the mountain and gave the reasons for their visits. The most valuable answers were related to the key sustainability issues, i.e., the issues of environmental quality, readiness to contribute to the development of tourism, thoughts about tourism affirmation and work on the identity of Stolovi Mountain.

As for the respondents from the territory of Kraljevo and its surroundings, a greater understanding was shown by women in the age category in which the average age of the Republic and the city is found. In this research, the relative majority of respondents had a university degree (

Table 3).

The people of Kraljevo and other people who lived in Stolovi Mountain and its surroundings highly appreciated that the Žiča Monastery (about 225 m above sea level) and the Mataruška Spa (about 212 m above sea level) were located in the foothills of their mountain. One in five were uninformed and did not perceive that these famous sites were located at the foot of Stolovi Mountain. Respondents were divided on the issue of the medieval fortress Maglič (333 m a.s.l.), but they were aware of its proximity to Stolovi Mountain. Maglič is on a hill, which rises to 78 m in relative height from the Ibar Valley, at a distance of only about 300 m and with an average slope of about 22.7%, so it borders the foothills and the mountain slope. Less than a third of respondents were not sure whether Maglić was built on the territory of the Stolovi Mountain massif. Lojanik Hill and the ‘Stone Forest’ (at about 270 m above sea level) were the least known localities to the people of Kraljevo. Only half of the respondents associated this site with Stolovi Mountain, while 2/5 of them clearly stated that they did not know about it.

When asked about the animals that Stolovi was known for, the majority (95.2%) of respondents noted wild horses. However, this question gave an insight into the presence of other wild animals, such as foxes, vipers, snakes, lizards, chamois, deer, bears, eagles, turtles, insects, etc. In addition to daffodils (87.8%), Stolovi Mountain was also recognizable to the respondents by its pines, firs and birches, as well as garlic or ramson (Allium ursinum), lilac (Syringa vulgaris), sedge grass (Cyperaceae), the great yellow gentian (Gentiana lutea), dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), wallflower (Erysimum cheiri), iris (Iris), etc.

Of all the respondents, 57 of them, or every fifth respondent (21.1%), had never visited the mountain, which is located 4–5 km south of the city center. In the group of these respondents, the majority were women. Only 14 (24.6%) male respondents had not visited the mountain. Among them, only two were born in Kraljevo. Compared to the entire group of respondents who had never visited Stolovi Mountain, 19, i.e., a third of them (33.3%), were born in Kraljevo. One of the interviewees pointed out in the comments section that it was a shame that, as a native of Kraljevo, she had never been to Stolovi Mountain. More than two fifths of the respondents had graduated from university (43.9%) or completed some form of postgraduate study. This information indicates that educational activities on Stolovi Mountain could be integrated into the teaching process.

Of the 213 people from Kraljevo who had ever visited the mountain, the majority of them visited it rarely; one in five stated that they visited it several times a year, followed by those who visited once a year. Among the respondents who were mountaineers, they visited it often, at twice a month (

Figure 4).

When asked why they did not visit the mountain, the majority of respondents (109 or 40.1%) did not answer, leaving a blank space. Other answers included the following: ‘I don’t have time’ (the most frequent answer—55 or 20.1%), ‘It does not come to my mind’, ‘I didn’t have the opportunity’, ‘I wonder myself’, ‘I don’t need to go’. Some people emphasized that they did not enjoy hiking, that it was not interesting to them, that they lacked a real reason, that there were no attractive aspects, etc. Therefore, they were not informed about the existing aspects. There were respondents who pointed out health reasons or the fact that ‘the road was not safe’. One respondent cited the fact that she had small children as a reason. All these respondents were also future visitors who could be attracted by other aspects. There were also unhelpful answers, such as ‘I’m lazy or I lack will’, ‘I don’t have a real reason’, ‘I don’t know what to say’, ‘I don’t have company’ or ‘I don’t have an answer’.

Therefore, the results of the research indicate that the main problem in the tourism affirmation of Stolovi Mountain is its partially recognized identity. This marketing failure can be corrected. Namely, touristic locations in the foothills of Stolovi Mountain should mention the mountain in their promotional activities. By creating an attractive offer and motivating them to visit Stolovi Mountain, mutual benefits can be obtained. The tourist offers of established localities would be improved, and Stolovi Mountain would gain visitors, who could bring income. Likewise, the visits of those who visit primarily for Stolovi Mountain could be enriched by aspects of the foothills and surroundings.

5.3. Results of GIS and Remote Sensing Methodology

In

Table 4, the digital relief analysis is confirmed. The results show that Stolovi Mountain (1375 m) has an azimuth direction between the southwestern sides (180°S–225° SW). The settlements Brezna, Kamenica, Maglič and Mataruge have sharp sides. These sides are suitable for walking, hiking and extreme sports. The other settlements, such as Žiča, Zamčenje, Kovači, Meljanica and Ribnica, are very suitable for walking, cycling and light recreational sports. The settlement of Mataruška Spa is well suited for walks, recreation and spa trails (

Table 4). The digital analyses of the relief have shown that there are five springs in the settlement of Brezna, three in the settlement of Meljanica, two in Zamčenje and one in Kamenica, Žiča and the Mataruška Spa (

Figure 5).

All springs are located on the southwestern side of the mountains of Stolovi and Ravna. The three regions of Brezna, Kamenica and Meljanica are situated at an altitude of more than 500 m. These places (tourist sites) have potential for winter tourism in the winter season (

Table 4 and

Figure 5). According to the evaluation of direct sunshine, on Stolovi Mountain, 62% of the sites are under direct sunshine and 38% of them are not (

Figure 5). The settlements with the sunniest sides are located in Brezna, Žiča, Kamenica, Mataručka Spa, Meljanica and Maglič. The orthodromic distance between the city of Kraljevo and the peak of Stolovi (1375 m) is 18,162.25 m. The altitude difference is 1183 m.

5.4. Results of Tourist Potential

At the end of the questionnaire, a space was left for respondents to indicate aspects of tourism potential related to Stolovi Mountain that are unknown or not sufficiently affirmed. Respondents often cited an under-affirmed manifestation called ‘Maglič—the fusion of traditional and modern’. It is organized by the Ribnica Cultural Center. It takes the form of a medieval assembly where knights’ fights are demonstrated and traveling musicians perform. Artisans and craftsmen display their skills on the walls of the fortress. In addition, there are children’s programs and a rich artistic program. The organizers also arrange a medieval feast.

Similar to this, there are countless locations on Stolovi Mountain that can be used with few resources for the needs of park adventures, archery, orienteering and various hiking tours. One of the walking tours could follow the legends, myths and stories that have been told for generations. Traces of mining activities date back to the time of the Romans, although there were also mining activities during the Middle Ages [

117]. Forests were cleared for the purpose of smelting ore.

The most famous legends tell about heroes from the end of the 14th century. From a distance, the main ridge of Stolovi Mountain appears completely flat and resembles a table. Legend states that Prince Lazar liked to come and hunt on this mountain. For his needs, the servants made wooden tables and benches. According to the locals, a herd of semi-wild horses has been permanently living on the slopes of Stolovi Mountain for more than 30 years. However, according to legend, the hero of Kosovo, Miloš Obilić, asked the herdsman Peter from Stolovi Mountain for a horse for himself. Turija is located in the place where Miloš gave money (in Serbian, to give). At the place where Ždralin, Miloš’s horse, stopped (stumbled), the site of Stublina is now located. Legend states that the herdsman, seeing his heroism, eventually gave the horse away. Thus, the people wished to remember some of the events by creating toponyms from them. Some toponyms recall the centuries-old presence of Turks. For example, the peak Čiker is derived from a Turkish word meaning ‘peak’.

According to Ćertić [

77], it is not fully known who the builders of the medieval fortress Maglič were, or who owned it first. It is believed that the fortification was most likely built by Uroš I after the Mongol invasions, in order to prevent new invasions through the Ibar Gorge, i.e., to protect the approach to his endowment of Sopoćani and the Studenica Monastery. According to one legend, it was built by Irina Kantakuzin, the wife of the despot Đurađ Branković, who was hated and therefore called the cursed Jerina. Experts reject this legend, because it would mean that the fort was built at the beginning of the 15th century. People often call Maglič Jerina’s City.

The grave of Jovan Petrović Đipanda is present on the field, and Marinković [

118] states that this man was one of the greatest local heroes from the First Serbian Uprising. It is important to note that the border of the Belgrade Pashaluk stretched across Stolovi Mountain, and, during the First Serbian Uprising, this was the border between liberated Serbia and the Ottoman Empire.

Stolski potok is characterized by the fact that, near its source, there are four old cemeteries with many unverified but intriguing stories. Access to the stream is difficult, because it is overgrown with branches and bushes. However, enthusiasm, volunteerism and entrepreneurial spirit could transform this site into a very attractive tourist destination. Each site has its own stories, which could inspire different walking tours, depending on the clientele. This means that a tour for children would differ from a tour for adults in both content and length.

5.5. Results and Discussion about Environmental Sustainability

The local population is the best informed about the state of the environment in which they live [

119]. The work of Awasthi et al. [

120] indicates a link between pollution and happiness. This is why it was important to organize a questionnaire that could check the quality of the environment. Descriptive statistics showed that the respondents did not agree that Stolovi Mountain is polluted (M = 2.0, σ = 1.01). Analyzing the responses of different sociodemographic categories did not show any statistically significant differences. Therefore, the absolute majority of respondents did not share the opinion that the water and air on this mountain are polluted or that they were endangered by noise. This conclusion supports hypothesis H1.

However, during the oral survey, some of the respondents stated that Stolovi was slightly polluted. An analysis of the responses showed that even those who had never been to this Mountain were informed about the sources of pollution. In search for an interpretation of the reasons for which some interviewees claimed that the air in this mountain was polluted and that they were threatened by noise, it was learned that quad bike rides are organized on Goč Mountain, which sometimes occur on Stolovi Mountain, too [

121]. They create noise and pollute the air. In addition, the people from the foothills of Stolovi Mountain, with whom an in-depth interview was conducted, described how visitors on motorbikes and jeeps managed to reach the highest elevations of Stolovi Mountain, such as the area where the cross is placed. The use of motorized vehicles on the mountain is prohibited, but people do not respect this decision. Locals state that the manifestation ‘In Pursuit of Daffodils’ in 2023 was officially canceled due to poor weather conditions, and, unofficially, due to the announcement of the arrival and conquest of the mountain by motor vehicles.

In the valley of Ribnica, there is a quarry of dacite-andesite [

105] and diabase. During the in-depth interviews, with the help of which some of the results of the survey were interpreted, it was learned that the quarry does not operate constantly, so the presence of the noise generated by it is occasional. In addition to the quarry, three lathes were also observed during the field observations, which also produce noise when they work.

More than half of the respondents stated that the waters in Stolovi Mountain were not polluted. A third of the respondents stated that they had no opinion on the quality of the water, while 6.7% of the respondents testified that the water in Stolovi Mountain could be polluted (

Table 5). With these answers, the following information was obtained. Those with some knowledge believe that pollution from the presence of the mentioned means of transport sometimes appears on the mountain (

Figure 6). More than 2000 people are present during the event ‘In Pursuit of Daffodils’. They leave municipal waste that can pollute waterways [

122]. There are no economic enterprises on Stolovi Mountain that can create pollution on this mountain. The poultry farm ‘Eko produkt’ and the metal agricultural equipment factory ‘Pomak’ are located in the northern foothills, more precisely in Žiča. ‘Messer Tehnogas’ is a chemical industry plant that deals with the distribution of medical and industrial gases in Ribnica. These plants do not disturb the mountain slopes; moreover, Stolovi Mountain captivates with the beauty and richness of its hydrographic network.

There are numerous sources of fresh and mineral water on Stolovi Mountain (

Figure 7). The water taken from some springs is used for swimming pools, such as the Meljanički swimming pool (

Figure 2(8)) and the swimming pool near Bučje, called Vir, both in the Ribnica River valley.

According to Lukić et al. [

61], there are five sources of mineral water, which are located in the southwestern part of the mountain (

Figure 7). One of them, which has water throughout the year, is shown in

Figure 8.

Long and clear rivers that are tributaries of the Ibar (Žička River, Trešnjarska River, Maglašnica, Dobrostranska River, Brezanska River with Šošanica) or Ribnica (Vilova and Jelova River with Meljanica) extend across Stolovi Mountain.

With regard to municipal and solid waste, half of the respondents stated that they were not informed, did not know, etc. Approximately a quarter claimed that they did not pollute Stolovi Mountain, and about a fifth of them stated that Stolovi was polluted by municipal and solid waste. The explanations obtained from the field research interpreted these answers in the following way. Pollution is present around settlements in the foothills. Settlements are connected to the sewage network of the city of Kraljevo, but there are facilities that are not. Municipal water enters the soil and this should be remedied as soon as possible by connecting it to the sewage network. At least one small garbage dump is registered in all settlements. The larger the population of the settlement, the more landfills there are. If Kraljevo is excluded, the village of Žiča has the largest number of small garbage dumps (10), while Brezna and Kamenica have only one each [

106]. In other words, the farther the settlements are from the city, the fewer inhabitants there are and the fewer landfills. Solid waste is removed every day in the city of Kraljevo, three times a week in Mataruška Spa and once a week in other settlements. The local population is often forced, due to the accumulated waste, to burn it frequently, thus polluting the soil and air. Communal and solid waste is left by careless and arrogant visitors. All conscientious visitors of Stolovi Mountain remove any debris that they find, whenever they have the opportunity. One aspect that is difficult to address is rubble, which is sometimes brought by people from the city and accumulated in a few places. This is the reason to involve the local population on a more serious level, so that it can respond adequately as needed. Possibly, they could record license plates or take pictures of the vehicles, actors, etc., in order to make it easier for communal services to find them and fine them. Research by Zhang [

123] and Ding and Shahzad [

124] shows that this form of punishment is the most effective.

All the mentioned environmental problems can be solved quickly and efficiently if there is an understanding among the local self-government bodies. It is necessary to ban and control the use of means of transport, as well as to place more transparent signs to ensure visitors’ environmental awareness. Waste disposal spots on routes used by visitors and the organization of their regular emptying are needed as well. Young volunteers from the foothills could be hired for this job. Engaging young people (final-year students of high schools, of which there are nine in the territory of the city of Kraljevo) on a weekend visit to develop environmental awareness and clean the mountain would be very significant and would present great benefits. The combination of volunteerism and physical activism can transform Stolovi Mountain into a free gym or space for, for example, aerobics. The forest farm ‘Stolovi’ reforests about 60 ha per year (150,000 seedlings). The people of Kraljevo, as well as other people, visit from Ivanjica, for example, to help with afforestation [

125]. The mentioned facts are very significant for the ecological sustainability of Stolovi Mountain, and, based on them, the hypothesis that the quality of the environment on this mountain is ecologically sustainable can be confirmed (H1).

Every year, at the foot of Maglič, a descent event takes place, which represents a form of regional attraction. From year to year, it attracts an increasing number of people. There are frequent rafting tours on the Ibar River as well. During the summer, on the small island, people can be seen camping and enjoying the beauty of the river. Regarding the ‘Eco Museum’ of the Ibarska Valley [

126], to which the medieval city of Maglič was supposed to belong, it is found that the proposal has not yet been realized. Activities related to green tourism are in favor of ecological sustainability. Therefore, in the case of an undisturbed natural balance, the main focus of any consideration, planning and action is its preservation. As solar cells are visible on some of the private houses in the area, they should be installed in order to provide light, hot water, energy to charge mobile phones, etc.

Stolovi Mountain was mentioned in 2005 in the Local Environmental Action Plan as one of the most important natural resources of the municipality of Kraljevo for the development of mountain tourism. This document shows the intention to include Stolovi Mountain in the ‘Health Path’ conceived by the Mountaineering and Skiing Association ‘Gvozdac’ from Kraljevo [

127]. The Strategy for the Development of the City of Kraljevo [

128] recognizes events of importance on Stolovi Mountain (‘In Pursuit of Daffodils’ and ‘Mountaineers’ Meeting’), as well as on the Ibar River (‘Happy Descent’). In addition, it sees Stolovi Mountain as a place for the development of sports and recreational tourism and mentions the project (1.5.18) of building the missing infrastructure, tourist facilities and tourist signage in order to develop the tourist offer. While the research was conducted, access to certain data required the consent of local authorities. Being introduced to the idea of this work, they began to provide institutional support. This can be explained on the basis of the fact that they adopted the Decree on the Declaration of the Landscape of Exceptional Features ‘Stolovi’, which was published in 2022 in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. It can be recognized as important support for sustainability. Thus, parts of Stolovi Mountain were placed under state protection in 2022 as an area of exceptional characteristics. The surface area of Stolovi Mountain of exceptional characteristics covers 9932.10 ha, of which 8699.64 ha (87.6%) are state property, 1113.59 ha (11.2%) are private property and 118.87 ha (1.2%) are other forms of property. Of the total area of exceptional features, 15.2% is included in the first degree, 30.9% in the second degree and 53.9% in the third degree of protection. This protection serves to preserve the hydrographic phenomena and watercourses with narrow and steep valleys, which appear as a gorge or a canyon. In addition, the focus is on two vegetation belts, composed of oak and beech, with a series of introduced and altered ecosystems, and an extremely diverse and rich animal world is preserved, consisting of invertebrates (65 species of orthopterans, 30 species of hornbills, three species of frogs and 32 species of grasshoppers), ichthyofauna (ten species of fish), 19 species of amphibian and reptile fauna, 125 species of birds and 47 species of mammals, fauna, otters and chamois [

107].

Given the mentioned facts that confirm the ecological sustainability, while bearing in mind the answers given by respondents who did not live in Kraljevo and its surroundings, it can be concluded that Stolovi Mountain can, after the mentioned adequate marketing procedures, serve to attract tourists who seek unspoiled nature and respect the rules of conservation. In one area, with minimal investments, there are localities that appeal to adventurers, mountaineers, and lovers of orienteering, peace, silence and the smell of mountain herbs.

5.6. Results and Discussion about Sociodemographic Sustainability

To consider the possibility of tourist movement, a labor force is needed. According to the data of the last two population censuses, it can be seen that Stolovi Mountain and its foothills are inhabited by ten thousand people. According to the latest population census, this number is 9.6% of the municipal population. It decreased by 9.4% in the inter-census period. This reduction is also evident in the wider area. It is encouraging that there is a city of over 50,000 inhabitants at the edge of the mountain and that there are other settlements in its vicinity with even more inhabitants (

Table 6), in which a labor force could be found for the needs of organizing tourist visits. These facts support the second hypothesis that the initiation of tourist movement on the mountain near a larger settlement is socially sustainable (H2).

In the overall gender structure, the female population predominates. However, geographically, it can be seen that women are more numerous in larger settlements and those that are closer to roads and the city. The male population is more numerous in more remote, mountainous settlements, such as Brezna, Meljanica and Ribnica.

The analysis of the age structure shows (

Table 7) that the most represented category of the population is the elderly (60+). Field research and conversations with this population showed that most of them are very wise, with a great deal of experience, and that everyone who is ‘in power’ is willing to contribute to the development of tourism on Stolovi Mountain. This was also shown by the descriptive statistics, indicating that the people of Kraljevo would be happy to contribute to the development of tourism on Stolovi Mountain (

Table 7). The local population in Serbia usually supports the development of tourism [

129,

130,

131]. A large standard deviation was created (σ = 1.27) due to the responses of the minority who were skeptical and who were afraid that the development of tourism would damage the quality of the natural environment. The

T-test and ANOVA did not identify any sociodemographic category representing a specific opinion and did not show any statistically significant differences. The descriptive statistics identified the cohort of 30–39 years, who agreed with this question the most (M = 4.05), and the oldest, who were undecided (M = 3.31) and mutually disagreed (σ = 1.44). Respondents who had completed only primary school agreed the most (M = 4.33, σ = 1.03), and the most educated proved to be the greatest skeptics (M = 3.62, σ = 1.50). In addition to the local population, there is also a mountain rescue service that helps visitors [

132].

The respondents agreed that the affirmation of tourism could be an opportunity to create new jobs (

Table 8). In support of their position, there are studies by Türker and Öztürk; Vujko and Gajić; Fang et al.; and Ibănescu et al. [

133,

134,

135,

136]. Due to the large standard deviation (σ = 1.33), responses were sought from a randomly selected local population. The greatest skeptics were found among the youngest (M = 3.36, σ = 1.40), because, according to Lukić [

137], they have the greatest affinity for emigration.

According to the data of the National Employment Service (2023), there are 5863 unemployed persons in the territory of Kraljevo. The absolute majority are women (61.0%). Unemployed people are the first target group that could provide valuable help to the organization and promotion of tourism on Stolovi Mountain. Slightly more than one tenth of the unemployed are those who have graduated from university, and they can provide significant intellectual or logistical support.

The questionnaire was used to obtain the opinions of the people of Kraljevo about tourism as a force that could oppose emigration, which is discussed by Maksimović and Milošević and Borović et al. [

138,

139]. When asked whether the affirmation of tourism would slow down the departure of young people, the respondents were not sure (M = 3.47), and they did not agree with each other (σ = 1.42). Female respondents showed agreement (M = 3.53), but men largely disagreed with each other (σ = 1.44). It is believed that their answers were influenced by their mothers’ beliefs that tourism could dissuade young people from deciding to leave home. The descriptive statistics of the age structure revealed that most age categories were undecided and that only those in the fourth and seventh decades of life agreed with this attitude. The analysis of respondents based on the acquired level of education showed undecidedness among the majority and agreement among the most educated respondents, namely university graduates, Masters of Arts and Doctors of Science (M = 3.86, σ = 1.46). This shows that their optimism was based on their foreign experiences and vision. Thanks to the diversity created in the economy, this would offer new job opportunities to the local people both directly and indirectly, increasing their welfare and reducing poverty [

140,

141].

Although sociodemographic sustainability is focused on the human resources that inhabit the slopes or the surroundings of Stolovi Mountain, it must be emphasized that there were interested parties among the older respondents, who showed their great interest when they learned of the resources located in the immediate vicinity of the mountain. They expressed their willingness to make their marketing experience available to facilitate mountain promotion. Older respondents, namely pensioners, stated that they had time to help, on the spot, in the future organization of tourist movement.

The presence of such people would be useful for the local population and others from the surrounding areas, but also for young people who could visit for training in the affirmation of tourist sites. Some of them may later continue to share their knowledge, but some may stay and rejuvenate the age structure of Stolovi Mountain.

5.7. Results and Discussion about Economic Sustainability

The analysis of the factors that support and harm economic sustainability has proven to be extremely complex, so only the indispensable and most interesting results are listed in the paper. Attention was first paid to transportation. This is the main factor that slows down economic development. Moreover, inhabitants of rural areas in Serbia complain about it [

142,

143]. Local and regional roads have been built around Stolovi Mountain. They follow the river valleys of Ibar and Ribnica. The western side of Stolovi Mountain ends in the Ibar Valley. It is precisely in this valley that the famous Ibarska Highway is laid out, which is a very busy road and various suburban and intercity lines pass through it [

144]. On this side of the mountain, there are few places to climb Stolovi Mountain. The main stronghold is the site called Maglič. A railway also runs through the Ibar Valley, but there are four stations in the foothills of Stolovi: Kraljevo, Mataruška Spa, Progorelica and Bogutovačka Spa. According to Marković et al. [

145], the train runs twice a day to the south and to the north on the route Kraljevo–Rudnica (a settlement located at the administrative crossing with Kosovo and Metohija). From Kraljevo to Kamenica (the eastern side of the mountain), there is daily public transport, with one departure and one return. Therefore, there is traffic infrastructure, which is the most important aspect. The local population mostly relies on their own transport. In Kraljevo and some of its settlements, there are agencies for the renting of vehicles and car repair shops. Traffic connections should not only serve this purpose, but they should be ‘at hand’ for those who visit the mountain. This would be economically rational and expedient. It would be beneficial if the available vehicles used renewable energy sources or at least ran on electricity.

As the construction of cable cars is gaining popularity in the region [

146,

147], one economically interesting initiative is a cable car that could connect some of the localities that are popular among tourists or Kraljevo itself with a viewpoint on Stolovi Mountain.

Fees for the visiting of tourist attractions are a normal phenomenon around the world [

148,

149,

150]. Respondents were very disagreeable σ = 1.61 and could not clearly state (

Table 9) whether an entrance fee to the 13th century fortress should be charged. The value M = 2.54 was closer to a state of disagreement than agreement. More precisely, all respondents under 40 years of age, respondents with a high school diploma, those who had never visited the area and women did not agree that an entry fee should be charged. Some respondents were of the opinion that an entrance fee should be charged to everyone who does not have an address from the area of Kraljevo on their ID. In other words, they did not agree that the local population should be charged. Charging for a visit to such landmarks, with the conscientious and rational management of income, would be valuable in improving the arrangement and maintenance of the area.

The respondents agreed that work on the identity and recognizability of the mountain would help in its touristic affirmation (

Table 9). This means that a visit to Stolovi Mountain could be offered to all tourists who visit the mountain’s foothills (Maglič, Žiča, Mataruška Spa, etc.), but also nearby tourist destinations (Vrnjačka Spa, Atomska Spa Gornja Trepča, Gradac Monasteries, Studenica, etc.). Only a small effort is needed in terms of emphasizing (in promotional materials) that these localities are present in the foothills or near Stolovi Mountain. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to implement and use modern technologies [

151] for marketing purposes. This primarily refers to the Internet and social networks, which, at present, spread information faster than any other means. Thousands of tourists circulate around Stolovi Mountain everyday, i.e., they visit the localities in the foothills and the surrounding area. Thus, the content of student excursions should be improved. A mountain can be viewed in the sense of a great companion for children, namely Generation Z [

152]—a place that offers them a peaceful expanse where they can feel the sun, breathe fresh air, move actively, run and become acquainted with various natural phenomena, such as the plants and animals of the mountain.

An in-depth interview with the local population showed that they were aware that Stolovi Mountain could finance itself, i.e., support itself. Assistance for interested visitors could be offered at locations where the ascents begin. These can be places where visitors can obtain refreshments, food and souvenirs. All respondents had common expectations of the authorities. Entrepreneurial initiatives are rare, but they do exist. Paragliders use Stolovi Mountain, because the man who ‘brought’ this activity to Serbia was from Kraljevo [

118].

The local population could only organize themselves in the production of original souvenirs, made from materials from nature. The wood obtained from the removal of trees in sanitary logging could be shaped, and the waste would not damage the quality of the environment. The local population could offer surplus food found on and around the mountain to tourists (canapés and vegetable or cheese pies and many other gastronomic specialties) and drinks (homemade tea made from mountain herbs, homemade juices from raspberries, blackberries, wild strawberries, elderberry and walnut brandy, for example). Therefore, food would help to improve sustainability in rural areas, as Lukić et al. [

153] conclude. Over a period of time, the income would increase the number of entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial initiatives and earnings and would also attract employees.

A certain level of accommodation capacity can be found in the houses of local residents or in the remodeling of abandoned residential buildings by volunteers, local residents and people who have found personal interest in the affirmation of tourism on this mountain. For example, in the village of Meljanica, there are registered rural households that provide accommodation with the use of outdoor swimming pools. Currently, there is one mountain lodge in the village of Brezna (

Figure 2(1)) on the slopes of Stolovi Mountain, which is opened as needed. It is maintained by the Mountaineering and Skiing society ‘Gvozdac’. The home has 20 military beds and can accommodate 30 people. In the warmer part of the year, the large terrace with benches can accommodate up to 70 people. Seen from the ecological side, there is no lack of accommodation facilities. Accommodation needs can be met in Kraljevo, which is 5 km north of the mountain. Statistical data for August 2022 show that, in Kraljevo, there are three hotels with 173 beds, which make up 10.6% of all beds that can be found in other accommodation facilities, such as rooms for rent, houses, apartments, rural tourist households, inns, lodgings, resorts, garni hotels, etc. In addition, there are other municipalities very close by that have a range of different accommodation capacities, such as Vrnjačka Spa [

154]. Sports centers are observed in the northern foothills in Mataruška Spa (which also has accommodation facilities) and Ribnica.

Catering facilities exist and are located in the foothills. In the Ibar Valley, there are three. They are located in Maglič and Zamčanje. There are about a dozen of them in the Ribnica Valley. One, ‘Zivanović’, was designed as an ethnic village. Slightly south of this, there is a bakery, which should work non-stop. They can be used to obtain food. Hikers often take packed lunches with them. Food consumption is a valuable source of income for the local population. This not only refers to catering establishments, but also to other services that may be needed, such as health clinics, hair and beauty salons, dentists, consumer goods and sports equipment stores, etc. In addition, there is a Gerontological and Rehabilitation Center in Mataruška Spa. Food can be offered in these and similar locations.

Meals may or may not be organized on the mountain. Items that cannot be obtained on the mountain can be found in the foothills or a nearby city. This is very important, because untouched nature can and must remain so for the sustainability of the ecosystem. Any item that could be used to complement and enrich the offer must not damage the quality of the environment at any cost, regardless of whether it is economically attractive. Therefore, Stolovi Mountain does not need investments, but only the organization of guides and guards whose work could be financed by tourism revenues and could be recognized, valued and supported by the local administration and self-government. According to all the above, the last hypothesis (H3) that the organization of tourist movement on the mountain near a larger settlement is fully economically sustainable has been confirmed.

Support for this conclusion was obtained during the surveys and conversations with people who did not live on the slopes of Stolovi Mountain and its surroundings. Bearing in mind that they had no direct interests in this, their support towards the tourism affirmation of Stolovi Mountain has greater importance, seriousness and strength.

6. Conclusions

Tourists favor an authentic offer, which could permit the initiation of tourist activities on the mountains next to a larger settlement. There are many mountains in Serbia similar to Stolovi Mountain. They are completely unnoticed and unused. Unique aspects can be found on each of them, i.e., horses, daffodils, a cross, etc., can be found on Stolovi Mountain. Mountains, such as Stolovi Mountain, are important to be affirmed as tourism sites in order to refine the tourist offer of the region, as well as increase financial interest, which can lead to more even regional development (creating new jobs, keeping young people, attracting young people from other parts of Serbia), proving that tourism does not necessarily have to negatively impact ecological sustainability. Ecotourism, recreation and cultural and event tourism are the forms of tourism that show the greatest potential.

From the aspect of ecological sustainability, the mountain is in excellent condition. Those types of tourist movement that are in accordance with ecological principles should be planned. Therefore, mountain climbing, hiking, engaged recreation, observation of the living world (daffodils, lilacs, birds, wild horses, etc.) can be suggested. The mountain is suitable for the organization of themed camps (forest lovers, bug lovers, bird lovers) for children throughout the summer. Stolovi Mountain is a place, according to one of the interviewees, where a person can lay down on clean grass to breathe clean air and listen to the chirping of birds. The superstructure is present in the surroundings of the mountain. Based on this, there is no need to disrupt the mountain area with new suprastructural content. Relying on green forms of tourism will guarantee the preservation of the environment and thus ecological sustainability.

Research indicates that tourist attractions are clearly recognized. It is necessary to connect Stolovi Mountain with the potential in the foothills, because this connection would provide it with its first visitors. Economic sustainability is possible only with the initiative of people, who can control the localities where the ascents to the mountain begin. Their role in this case would be in the collection of donations for the preservation of the nature of Stolovi Mountain and the procurement of food for horses and other wild animals. In addition, funding could be collected as part of the income from the hiring of accredited guides and part of the income from the sold souvenirs, i.e., the costs of value added tax and compensation to souvenir makers and sellers. There is also interest among the local population for this type of assistance, having in mind an additional source of income. Raw materials for souvenirs can be found on the mountain (e.g., wood can be obtained through sanitary logging). Souvenirs made from natural materials support environmental sustainability. The development of tourism should lead to an increase in the percentage of occupied accommodation, which will result in a higher share of tourism in the gross domestic product (GDP). More precisely, the inclusion of a visit to Stolovi Mountain in an itinerary that features the tourist attractions of Kraljevo and its surroundings should extend the stay of tourists by one day. The quality of the organization and offer, if professionally designed and implemented, would quickly spread from person to person and via media. An extension of one’s stay means an increase in both boarding and non-boarding spending, which increases income. Positive economic effects can only positively affect the sociodemographic conditions and sustainability.