Leveraging Local Value in a Post-Smart Tourism Village to Encourage Sustainable Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Smart Tourism Destination, Smart Tourism Village, Post-Smart Tourism Village

2.2. Digital Competence in Smart Tourism Community

2.3. Circular Economy in Smart Tourism Village

2.4. Leveraging Creative Festivals to Improve CE, Digital Competence, and the Attractiveness of Smart Tourism

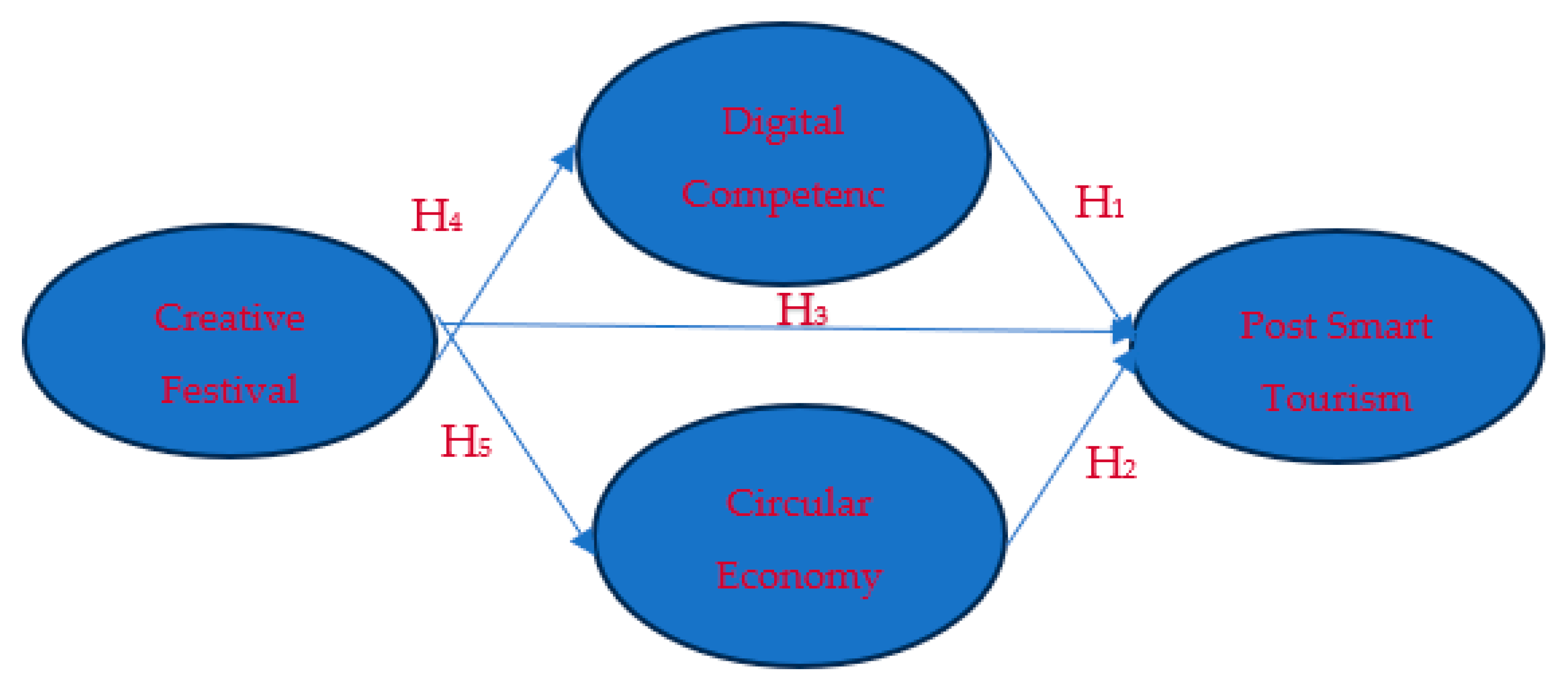

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Stakeholders’ View on Living Culture Festival, Circular Economy, and Smart Tourism Village

4.2. Quantitative Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koo, C.; Shin, S.; Gretzel, U.; Hunter, W.C.; Chung, N. Conceptualization of Smart Tourism Destination Competitiveness. Asia Pacific J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 26, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, F. Smart tourism destination: A bibliometric review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 34, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Pavon, S.; Lopez-Mosquera, N.; Jim’enez-Naranjo, H. The role emotions play in loyalty and WOM intention in a Smart Tourism Destination Management. Cities 2024, 145, 104681. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4402675 (accessed on 14 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Badri, H.; Hmioui, A. Smart Tourism Destination Competitiveness: The Exploitation of the Big Data in Morocco. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. ISPRS Arch. 2021, 46, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktaş Kulualp, H.; Sarı, Ö. Smart Tourism, Smart Cities, and Smart Destinations as Knowledge Management Tools. In Handbook of Research on Smart Technology Applications in the Tourism Industry; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 371–390. [Google Scholar]

- Pranita, D.; Sarjana, S.; Musthofa, B.M.; Kusumastuti, H.; Rasul, M.S. Blockchain Technology to Enhance Integrated Blue Economy: A Case Study in Strengthening Sustainable Tourism on Smart Islands. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, C.; Rodrigues, P.; Gomez-suarez, M. A Bibliometric and Content Analysis of Sustainability and Smart Tourism. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, L.; Aebischer, B. Smart Sustainable Cities: Definition and Challenges. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2015, 310, 351–365. [Google Scholar]

- Ribes, J.F.; Baidal, J.I. Smart sustainability: A new perspective in the sustainable tourism debate. Investig. Reg. 2018, 42, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgaz, B.; Özerden, S.T. As a road map of sustainable tourism smart cities and smart. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Global Practice of Multidisciplinary Scientific Studies, Baku, Azerbaijan, 10–12 December 2023; pp. 1491–1507. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368655079_AS_A_ROAD_MAP_OF_SUSTAINABLE_TOURISM_SMART_CITIES_AND_SMART_TOURISM#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Aguirre, A.; Zayas, A.; Gómez-Carmona, D.; López Sánchez, J.A. Smart tourism destinations really make sustainable cities: Benidorm as a case study. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 9, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelter, J.; Fuchs, M.; Lexhagen, M. Making sense of smart tourism destinations: A qualitative text analysis from Sweden. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, K.H.; Jahan, I.; Zayed, N.M.; Islam, K.M.A.; Suyaiya, S.; Tkachenko, O.; Nitsenko, V. Smart Tourism Ecosystem: A New Dimension toward Sustainable Value Co-Creation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, S.; Rajabzadeh Ghatari, A.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Jahanyan, S. Developing a model for sustainable smart tourism destinations: A systematic review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Beyond smart tourism cities—Towards a new generation of “wise” tourism destinations. J. Tour. Futur. 2021, 7, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M.; Zwolinska-Ligaj, M. The “smart village” as away to achieve sustainable development in Rural Areas of Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranita, D.; Kesa, D.D.; Marsdenia. Digitalization Methods from Scratch Nature towards Smart Tourism Village; Lessons from Tanjung Bunga Samosir, Indonesia. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1933, 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Crespo, P.; Bermudez-Edo, M.; Garrido, J.L. Smart tourism in Villages: Challenges and the Alpujarra Case Study. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 204, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyambodo, T.K.; Artianingsih, M.D. Strategy for Sustainable Smart Tourism Village Development in Ponggok Village, Klaten, Central Java. Int. J. Sustain. Compet. Tour. 2022, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Adamov, T.; Feher, A.; Stanciu, S. Smart Tourist Village—An Entrepreneurial Necessity for Maramures Rural Area. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorobantu, M.R.; Gheorghe, G.; Nistoreanu, P. New Ways to Value Tourism Resources from Rural Environment. Compet. Agro-Food Environ. Econ. 2012, 1, 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Košić, K.; Demirović, D.; Dragin, A. Living in a Rural Tourism Destination—The Local Community’s Perspective. Tour. South. East. Eur. 2017, 4, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.H.; Kim, J.; Jeong, M. Memorable tourism experience at smart tourism destinations: Do travelers’ residential tourism clusters matter? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustacha, I.; Baños-Pino, J.F.; Del Valle, E. The role of technology in enhancing the tourism experience in smart destinations: A meta-analysis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Milon, A.; Juaneda-Ayensa, E.; Olarte-Pascual, C.; Pelegrín-Borondo, J. Towards the smart tourism destination: Key factors in information source use on the tourist shopping journey. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xie, C.; Huang, Q.; Morrison, A.M. Smart tourism destination experiences: The mediating impact of arousal levels. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriyani, I.G.A.D. Siaran Pers: Menparekraf Dorong Kepala Daerah Maksimalkan Pengembangan Desa Wisata. Badan Pariwisata dan Ekonomi Kreatif. 2022. Available online: https://www.kemenparekraf.go.id/berita/siaran-pers-menparekraf-dorong-kepala-daerah-maksimalkan-pengembangan-desa-wisata (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- Rudwiarti, L.A.; Pudianti, A.; Emanuel, A.W.R.; Vitasurya, V.R.; Hadi, P. Smart tourism village, opportunity, and challenge in the disruptive era. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 780, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranita, D.; Sarjana, S.; Musthofa, B.M. Mediating Role of Sustainable Tourism and Creative Economy to Improve Community Wellbeing. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2022, 11, 781–794. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart Tourism Destinations. In Proceedings of the International Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 21–24 January 2014; pp. 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H.M.; Huertas, A.; Moreno, A. (SA)6: A New Framework for the Analysis of Smart Tourism Destinations. In A Comparative Case Study of Two Spanish Destinations; Publicacions de la Universitat d’Alacant: Alicante, Spain, 2017; pp. 190–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bulchand-Gidumal, J. Post-COVID-19 recovery of island tourism using a smart tourism destination framework. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendi, Y. Internet of Things (Iot) Sistem Pengendalian Lampu Menggunakan Raspberry Pi Berbasis Mobile. J. Ilm. Ilmu Komput. 2018, 4, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Initiative of the European Union. Leading Examples of Smart Tourism Practices in Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; pp. 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Werthner, H.; Koo, C.; Lamsfus, C. Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Comput. Human. Behav. 2015, 50, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecsek, B. Working on holiday: The theory and practice of workcation. Balk. J. Emerg. Trends Soc. Sci. 2018, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sarjana, S.; Claudia, S.A.; Ramadhina, A.T.; Suyanti, L. Acceleration of the Battery Electric Vehicle Program through Carbon Tax and Strategic Management between Government Institutions. In RSF Conference Series: Engineering and Technology; RSF Press: Bandung, Indonesia, 2023; pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pranita, D. Post-Smart Tourism Destination: Have We Been Wise Enough? In Proceedings of the International Conference on Vocational Education Applied Science and Technology (ICVEAST 2023), Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research; Atlantis Press SARL: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehade, M.; Stylianou-Lambert, T. Revisiting Authenticity in the Age of the Digital Transformation of Cultural Tourism. In Cultural and Tourism Innovation in the Digital Era; Sixth International IACuDiT Conference, Athens 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppantonio Di Franco, P.; Galeazzi, F.; Vassallo, V. Authenticity and Cultural Heritage in the Age of 3D Digital Reproductions; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2018; 138p. [Google Scholar]

- Veerasamy, S.; Goswami, S. Smart Tourism Intermingling with Indian Spiritual Destinations: Role of e-WoM Sentiments in marketing. ASEAN J. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 20, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodnah, K.D.; Armoogum, V.; Jaunky, V.C.; Armoogum, S. Towards Smart Tourism: An. individual appreciation of Porlwi-By-Light festival: An Ordered Probit Approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Innovative Business Practices for the Transformation of Societies (EmergiTech), Balaclava, Mauritius, 3–6 August 2016; pp. 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Andres Coca-Stefaniak, J.; Seisdedos, G. Smart urban tourism destinations at a crossroads-being “smart” and urban are no longer enough. In Handbook of Tourism Cities; Morrison, A.M., Coca-Stefaniak, J.A., Eds.; The Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S. Smart Tourism Development in Small and Medium Cities: The Case of Macao. J. Smart Tour. 2021, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmat, E.N.A. A Literature Review on Smart City and Smart Tourism. J. Inov. Penelit. 2021, 1, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar]

- Marguna, A.M.; Sangiasseri. Pengaruh Kompetensi Digital (e-Skills) Terhadap Kinerja Pustakawan di UPT Perpustakaan Universitas Hasanuddin. Jupiter 2020, 17, 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Steens, B.; Bots, J.; Derks, K. International Journal of Accounting Developing digital competencies of controllers: Evidence from the Netherlands. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2024, 52, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarjana, S.; Widokarti, J.R. Strengthening Partnership Strategy for Digital Development in Water Tourism. In Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Urrutia, X.; Morales-Urrutia, D.; Simabaña-Taipe, L.; Ramírez, C.A.B. Smart tourism and the application of ICT: The contribution of digital tools. RISTI Rev. Iber. Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2020, E32, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Resmawa, I.N.; Masruroh, S. Konsep Dan Strategi Pengembangan Creative Tourism Pada Kampung Parikan Surabaya. Ikraith-Hum. 2019, 3, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sava, D.C. The Creative Tourism—An Interactive Type of Cultural Tourism. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2021, 21, 486–492. [Google Scholar]

- Boes, K.; Buhalis, D.; Inversini, A. Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, A.; Alexandru, C.A.; Coardos, D.; Tudora, E.; Definition, A.B.D. Big Data: Concepts, Technologies and Applications in the Public Sector. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Eng. 2016, 10, 1670–1676. [Google Scholar]

- De Mello, J.C.; Faxina, F. Smart City and Smart Tourist Destinations: Learning from New Experiences in the 21st century. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2021, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R. Framework for Building Smart Tourism Big Data Mining Model for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Liberato, P.M.; Alén-González, E.; de Azevedo Liberato, D.F.V. Digital Technology in a Smart Tourist Destination: The Case of Porto. J. Urban. Technol. 2018, 25, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Garbin Praničević, D. The Impact of ICT on Actors Involved in Smart Tourism Destination Supply Chain. e-Rev. Tour Res. 2019, 16, 234–243. Available online: http://ertr.tamu.edu (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Yang, S.; Yumeng, L.; Ziqi, Y. Tourists’ Risk Perception of Smart Tourism Impact on Tourism Experience. In 2022 International Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities and Arts (SSHA 2022); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 653, pp. 368–375. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Ormazabal, M. Towards a consensus on the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Florido, C.; Jacob, M. Circular economy contributions to the tourism sector: A critical literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszás, N.; Keller, K.; Birkner, Z. Understanding circularity in tourism. Soc. Econ. 2022, 44, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfors, S. Circular Economy in Tourism: A System-Level Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism Research 2023, Pafos, Cyprus, 8–9 June 2023; pp. 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cabrera, J.; López-Del-pino, F. The 10 most crucial circular economy challenge patterns in tourism and the effects of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, F.; Bærenholdt, J.O.; Greve, K.A.G.M. Circular economy tourist practices. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2762–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, L.F.; Nocca, F. From linear to circular tourism. Aestimum 2017, 70, 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mies, A.; Gold, S. Mapping the social dimension of the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, P.; Domenech, T.; Drummond, P.; Bleischwitz, R.; Hughes, N.; Lotti, L. The Circular Economy: What, Why, How and Where. Managing environmental and energy transitions for regions and cities. In Managing Environmental and Energy Transitions for Regions and Cities; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Valavanidis, A. Concept and Practice of the Circular Economy Concept and Practice of the Circular Economy. Athanasios Valavanidis 2018, 4, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Heshmati, A. A review of the circular economy and its implementation. Int. J. Green. Econ. 2017, 11, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimbaljević, M.; Stankov, U.; Demirović, D.; Pavluković, V. Nice and smart: Creating a smarter festival–the study of EXIT (Novi Sad, Serbia). Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Mele, G.; Ndou, V.; Secundo, G. Creating value from Social Big Data: Implications for Smart Tourism Destinations. Inf. Process Manag. 2018, 54, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Marketing smart tourism cities—A strategic dilemma. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabry, N.; Zeghni, S. Smart destination management driven by emotions and small data. In Proceedings of the SMART Tourism Destination Increasing Citizen’s Sentiment of Sharing Local Tourism Related Values through Gamification Using Emerging Mobile Apps and SMALL Data Analysis, Marne-laVallée, France, 26 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer, B.; Magnus, B.; Celuch, K. The impact of artificial intelligence on event experiences: A scenario technique approach. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, A.; Lobo, J. Technology Driving Event Management Industry to the Next Level. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO), Noida, India, 4–5 June 2020; pp. 436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.P. The Age of Hybrid Events Amplifying the Power of Culture through Digital Experiences (Music Festivals Feat. Technology). Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto Politecnico do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Calisto, M. From Circular Economy to Circular Society: Analysing Circularity Discourses and Policies and Their Sustainability Implications. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- D’souza, N.; Dastmalchi, M.R. Creativity on the move: Exploring little-c (p) and big-C (p) creative events within a multidisciplinary design team process. Des. Stud. 2016, 46, 6–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunita, Y. Telaah Kompetensi Guru di Era Digital dalam Membangun Warga Negara yang Baik. ASANKA J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2023, 4, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.R.; Bidari, S.; Bidari, D.; Neupane, S.; Sapkota, R. Exploring the Mixed Methods Research Design: Types, Purposes, Strengths, Challenges, and Criticisms. Glob. Acad. J. Linguist. Lit. 2023, 5, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawadi, S.; Shrestha, S.; Giri, R.A. Mixed-Methods Research: A Discussion on its Types, Challenges, and Criticisms. J. Pract. Stud. Educ. 2021, 2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business, 4th ed.; Salemba Empat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Riduwan. Skala Pengukuran Variabel-Variabel Penelitian; Alfabeta: Bandung, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Pearce, P.L.; Oktadiana, H. Can digital-free tourism build character strengths? Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapuz, M.C.M. The role of local community empowerment in the digital transformation of rural tourism development in the Philippines. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjielias, E.; Christofi, M.; Christou, P.; Hadjielia Drotarova, M. Digitalization, agility, and customer value in tourism. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 175, 121334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, S.; Flynn, S.; Kylänen, M. Digital transformation in tourism: Modes for continuing professional development in a virtual community of practice. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, M.R.; Panait, M.; Bacoş, I.B.; Naghi, L.E.; Oltean, F.D. Circular tourism economy in European union between competitiveness, risk and sustainability. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, F.; Bærenholdt, J.O. Tourist practices in the circular economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Wang, C.; Tang, D.; Ye, W. Tourism circular economy: Identification and measurement of tourism industry ecologization. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 144, 109476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.Q.; Kovacs, J.F. Creative tourism and creative spectacles in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoaldo, P.; Serra, J.; Marujo, N.; Alves, J.; Gonçalves, A.; Cabeça, S.; Duxbury, N. Profiling the participants in creative tourism activities: Case studies from small and medium sized cities and rural areas from Continental Portugal. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, D.; Saxena, G. Participative co-creation of archaeological heritage: Case insights on creative tourism in Alentejo, Portugal. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, L.; Saeli, M.; Campisi, T. Smart technological tools for rising damp on monumental buildings for cultural heritage conservation. A proposal for smart villages implementation in the Madonie montains (Sicily). Sustain. Futur. 2023, 6, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokun, K.; Nazarko, J. Smart villages concept—A bibliometric analysis and state-of-the-art literature review. Prog. Plann. 2023, 175, 100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, R.; Sudaryono; Wijono, D.; Prayitno, B. Tourism Development of Historical Riverbanks in Jatinom Village. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 227, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ashfaq, M.; Tandon, A.; Zhang, Q.; Jabeen, F.; Dhir, A. Doing good for society! How purchasing green technology stimulates consumers toward green behavior: A structural equation modeling–artificial neural network approach. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 1274–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dai, J.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; He, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, Q. Mechanism of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence the green development behavior of construction enterprises. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachri, H.; Sarjana, S. Performance evaluation through the effectiveness of resources and reputation: A case study of hospitals in Indonesia. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2022, 20, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesberg, J.; Brunton-Smith, I.; Bradford, B. Police visibility, trust in police fairness, and collective efficacy: A multilevel Structural Equation Model. Eur. J. Criminol. 2023, 20, 712–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarjana, S. Strengthening Manufacturing Competitiveness Through Sustainable Manufacturing Among Industrial Estate in West Java, Indonesia. J. Bus. Soc. Dev. 2023, 10, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Niekerk, M. Contemporary issues in events, festivals and destination management. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M. The Role of Partnerships in Staging Tourist Experiences. In Tourism Management, Marketing, and Development; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, J.; Turaev, B.; Mohanty, P. Festival and Event Tourism Building Resilience and Promoting Sustainability; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2022; pp. 1–161. [Google Scholar]

- Astuti, P.D.; Chariri, A.; Rohman, A. Tri hita karana’s philosophy and intellectual capital: Evidence from the hotel industry in Indonesia. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2021, 17, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudana, I.G.; Gusman, D.; Ardini, N.W. Implementation of tri hita karana local knowledge in uluwatu temple tourist attraction, Bali, Indonesia. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2023, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, P.R.A.M.; Kartika, I.M. Membangun Karakter Berlandaskan Tri Hita Karana Dalam Perspektif Kehidupan Global. J. Pendidik. Kewarganegaraan Undiksha 2021, 9, 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Padet, I.W.; Krishna, I.B.W. Falsafah Hidup Dalam Konsep Kosmologi Tri Hita Karana. Genta Hredaya 2018, 2, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Adhitama, S. Konsep tri hita karana dalam ajaran kepercayaan budi daya. Dharmasmrti J. Ilmu Agama Kebud. 2020, 20, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisnawa, D.K. Implementasi Nilai-Nilai Tri Hita Karana dalam Atraksi Wisata di Pura Desa dan Puseh Desa Adat Batuan. Pariwisata Budaya J. Ilm. Pariwisata Agama Budaya 2020, 5, 13–29. Available online: http://ejournal.ihdn.ac.id/index.php/PB/index (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Farhan, H.; Anwar, K. The Tourism Development Strategy Based on Rural and Local Wisdom. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tou, H.J.; Noer, M.; Helmi; Lenggogeni, S. Spatial Planning with Local Wisdom for Rural Tourism Development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 556, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.; Casado-Díaz, A.B.; Navarro-Ruiz, S.; Fuster-Uguet, M. Smart tourism city governance: Exploring the impact on stakeholder networks. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghozali, I. Aplikasi Analisis Multivariate Dengan Program SPSS; Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro: Semarang, Indonesia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsson, S.; Sorin, F. Circular Economy in Travel and Tourism: A Conceptual Framework for a Sustainable, Resilient and Future Proof Industry Transition. CE360 Alliance. 2020. Available online: http://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/circular-economy-in-travel-and-tourism.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2023).

| Experts | Concepts |

|---|---|

| [1] | Current and future practices comprised various activities, including (1) waste sorting, (2) nature tourism such as hiking, cycling, and outdoor holidays, (3) transportation consisting of cycling, walking, trains, and other forms of movement, (4) accommodation, (5) sharing, and (6) reusing materials. |

| [43] | Smart tourism evolved as a social phenomenon, originating from the convergence of ICT with tourism experiences. This evolution was supported by concerted efforts to collect and use data from various sources, including physical infrastructure, social relations, government, and the human mind. The integration of advanced technology played a crucial role in transforming these data. |

| [14] | Smart tourism represented a logical evolutionary step beyond traditional and e-tourism. It served as the foundation for technology-driven innovation, obtaining inspiration from the smart city concept. Innovative tourism destinations were constructed on modern technology infrastructure, fostering sustainable and accessible development in tourist areas. The objective was to enhance tourism experiences, improve the quality of life for residents, support businesses, and establish a smarter platform for the distribution and collection of destination data. |

| [5] | STD included assembling a tourism ecosystem through a web-based application. This aimed to enhance destination efficiency and address the evolving expectations and needs of both tourists as well as residents. The focus was on holistic innovations comprising all stakeholders in the tourism ecosystem while also promoting the responsible use of environmental and social resources. |

| [44] | Examined key parallels between the concepts of smart cities and smart tourism destinations, traditionally dominated by technology-based approaches. However, a new generation of smart initiatives was evolving with a more human-centered focus. |

| [45] | Smart tourism, as a branch of smart cities, aims to address tourists’ travel-related needs, enhance travel experiences, and improve the competitiveness of destinations. |

| [46] | STD used tools, techniques, and technology to co-create tourist experiences. This included adopting tourism platforms to integrate services and other tourism resources. |

| [15] | Offered insights into wiser tourism development, exploring avenues for a more humanistic and local value context in STD. This method ensured that each destination retained unique characteristics. |

| [10] | Smart sustainable tourism includes the incorporation of ICT, smart technology, and various applications to adapt the services provided to tourists. |

| Experts | Concepts |

|---|---|

| [57] | The smart destination was synonymous with wise tourism, serving as a destination founded on an advanced technology infrastructure capable of ensuring sustainable development. Instruments for such features included ICT infrastructures (cloud computing, IoA, IoE, and IoM), mobile devices, virtual reality, and services based on the user’s location. |

| [58] | ICT evolved from the digital revolution, allowing stakeholders and destination authorities to efficiently access knowledge and information regarding the components of the tourism industry and travelers’ experiences, which were then evaluated. |

| [50] | ICT served as a crucial tool to enhance processes and introduce smart concepts, including smart tourism. This intelligent concept operated on the socio-technical paradigm, treating technology and individuals as collaborative actors to co-create value in the included sectors’ economic, social, and environmental prosperity. |

| [12] | The evolution of the smart tourism concept was closely related to digitalization. In smart tourism, ICT plays a role in supporting the marketing and delivery of goods and tourist services, along with the development of technological infrastructures. |

| [59] | The technological capabilities of smart tourism destinations enhanced the efficiency of resource management and sustainability, providing opportunities for interactive activities. This increased competitiveness, leading many regions to undergo modernization. |

| Experts | Concept |

|---|---|

| [63] | CE was an economic system that altered the standard of interaction between humans and nature at a system-level production to conserve resources, reduce waste, and improve efficiency. It could be implemented at the company, tourist, and destination levels to transform the loop of production and usage, influencing how resources are used and reused. |

| [68] | CE comprised two conceptual strands originating from industrial ecology. One strand addressed the flow of materials within an economy, while the other focused on the factors influencing the direction of the flow. |

| [69] | CE repurposes materials at the end of the service life into resources for others, minimizing waste. |

| [70] | CE functioned as a strategy for sustainability, addressing ecological deterioration and resource shortages. It used the principles of the 3Rs, namely reduce, reuse, and recycle in material management. |

| Experts | Concepts |

|---|---|

| [72] | Organizing cultural festivals and other events comprised crafting a smart experience, enhancing the attractiveness of STD, fostering discussions and engagement of STD, implementing a new business model to facilitate dynamic connections with external stakeholders, and enhancing the interconnectedness of the business ecosystem. |

| [73] | Festivals and other social innovations negatively affected the cognitive function of the human brain in processing emotions and memory and storing life experiences in the context of technology. However, STDs demanded creativity, innovation, and intelligence in destination branding, along with the preservation of authenticity through a unique destination approach centered on the ecosystem. |

| [71] | The evolution of smart technology enhanced the tourist experience, and smart festivals could be related to smart tourism destinations. A smart festival was an event contributing to cultural life and constituting a tradition for the destination. |

| [74] | Festivals were tourist practices associated with emotion, shaping tourism experiences and memories, which became the active response of visitor responses even in smart tourism destinations. |

| Variables | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Digital Competence [85,86,87,88] |

|

| Circular Economy in Tourism [6,89,90,91] |

|

| Creative Event [92,93,94,95] |

|

| Post-Smart Tourism [18,96,97,98] |

|

| Stakeholders | Expert Opinions | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Head of Rural Area Empowerment, Department of Village Community Empowerment (VCE), Gianyar. | To support Kenderan Village, the local residential government provided policies and budget allocations, with a particular focus on waste management, enhancing the welfare of individuals, and facilitating the growth of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). | Supporting tourism village. |

| Secretary of Cooperative Office | Foster events that activate local participation in SME businesses and suggest the concept of the Temple becoming the central hub for various activities within the local community. | Use Temple to support local businesses and SMEs. |

| Digital Ambassador of Gianyar Region | Provide digital access for community business and facilitate coordination. | Digital Accessibility |

| Religious Leader | The potential of the temple to serve as a catalyst for change, a focal point for religious, economic, socio-cultural, and conservation activities, and a pilot program for the development of a smart and circular economy tourism village. | Improve the role of the temple in the community’s daily productive lives. |

| Community Leader | Tourism villages strived to establish excellence and uniqueness to succeed in the competition. | Focus on economic and welfare gain from tourism or creative industry. |

| Tourism Group Leader | Tri Hita Karana philosophy, circular economy, and living culture festival served as avenues for differentiating tourist destinations. | Local wisdom and events for developing thematic tourism. |

| Environmentalist | The lack of sustainable awareness and practices among the community prompted the initiation of a campaign against plastic usage and the promotion of sustainable practices in Tegallalang. During the pandemic, collaborative efforts with donors and local philanthropists were established, facilitating an exchange program where 1 kg of waste could be exchanged for 1 kg of rice. | Sustainable awareness for destination preservation. |

| Tourism Business Group Leader | The integration of local wisdom, locally produced items, and creativity was considered essential, with a pressing need for tourism packages that also incorporate local businesses. | Local business enhancement. |

| Creative Industry Leader | Promote sustainability by adopting the practice of planting one tree for every use of one log. | Sustainable practice to increase business. |

| Village-owned Enterprises (BUMDES) | Leverage local festivals as a platform to stimulate, advertise, and enhance the informal economy and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). | Improve business and local welfare. |

| Variable | Indicators | Code | Standardized Loading (L) | t | Prob. | Construct Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creative Events | Tangible Environment | CE1 | 0.87 | 9.6 | 0 | 0.96 | 0.78 |

| Social Cohesion | CE2 | 0.9 | 9.98 | 0 | |||

| Innovative Novel | CE3 | 0.89 | 9.78 | 0 | |||

| Concept | |||||||

| Sense of | CE4 | 0.88 | 9.73 | 0 | |||

| Professionalism | |||||||

| Local Wisdom | CE5 | 0.89 | 9.85 | 0 | |||

| Content | |||||||

| Special Performance | CE6 | 0.87 | 9.62 | 0 | |||

| Tourism Circular Economy | Preservation of | TCE1 | 0.69 | - | - | 0.93 | 0.73 |

| Resources | |||||||

| Green Technology Adoption | TCE2 | 0.89 | 6.03 | 0 | |||

| Environmental Stewardship | TCE3 | 0.78 | 5.6 | 0 | |||

| Waste Management | TCE4 | 0.94 | 6.16 | 0 | |||

| Sustainable | TCE5 | 0.95 | 6.19 | 0 | |||

| Environment | |||||||

| Digital Competence | Information Handling | DC1 | 0.89 | - | - | 0.95 | 0.81 |

| Social Networking | DC2 | 0.89 | 7.3 | 0 | |||

| Content Creation | DC3 | 0.92 | 7.48 | 0 | |||

| Safety Concern | DC4 | 0.91 | 7.45 | 0 | |||

| Post-Smart Tourism | Digital Experience | Smart1 | 0.82 | - | - | 0.93 | 0.74 |

| Smart Business Ecosystem | Smart2 | 0.88 | 7.2 | 0 | |||

| Technological | Smart3 | 0.87 | 7.15 | 0 | |||

| Infrastructure | |||||||

| Interactive | Smart4 | 0.85 | 7.04 | 0 | |||

| Communication | |||||||

| Real-Time | Smart5 | 0.87 | 7.18 | 0 | |||

| Information |

| No | Hypothesis | Coeff. | Standard | t-Stat | Prob. | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Error | |||||

| 1 | DC → PST | 0.440 * | 0.12 | 3.8 | 0 | 0.194 |

| 2 | TCE → PST | 0.270 * | 0.11 | 2.39 | 0.018 | 0.073 |

| 3 | CE → PST | 0.300 * | 0.13 | 2.24 | 0.026 | 0.09 |

| 4 | CE → DC | 0.660 * | 0.095 | 6.93 | 0 | 0.436 |

| 5 | CE → TCE | 0.690 * | 0.12 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.476 |

| 6 | CE → TCE → PST | 0.186 ** | 0.083 | 2.257 | 0.025 | 0.186 |

| 7 | CE → DC → PST | 0.290 ** | 0.09 | 3.243 | 0.001 | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kusumastuti, H.; Pranita, D.; Viendyasari, M.; Rasul, M.S.; Sarjana, S. Leveraging Local Value in a Post-Smart Tourism Village to Encourage Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2024, 16, 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020873

Kusumastuti H, Pranita D, Viendyasari M, Rasul MS, Sarjana S. Leveraging Local Value in a Post-Smart Tourism Village to Encourage Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability. 2024; 16(2):873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020873

Chicago/Turabian StyleKusumastuti, Hadining, Diaz Pranita, Mila Viendyasari, Mohamad Sattar Rasul, and Sri Sarjana. 2024. "Leveraging Local Value in a Post-Smart Tourism Village to Encourage Sustainable Tourism" Sustainability 16, no. 2: 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020873

APA StyleKusumastuti, H., Pranita, D., Viendyasari, M., Rasul, M. S., & Sarjana, S. (2024). Leveraging Local Value in a Post-Smart Tourism Village to Encourage Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability, 16(2), 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020873