Sustainable Development Goals and Gender Equality: A Social Design Approach on Gender-Based Violence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Gender Equality and Gender-Based Violence: The Foundation Stone

Contextualizing Gender-Based Violence

3. Social Design: The Genesis of Social Change by Design

| Design Discipline | Explanation | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Design for social Innovation | Social innovation became essential to move forward the conceptual idealisation to an authentic product of design for social change. Its outcomes are meaningful and based on new social and economic models. Additionally, the diffusion of design thinking as a model of approach was evidenced by social innovation and its entrepreneurial spheres and collective network proposal. | Margolin, V. and Margolin, S. 2002 [40]; Mulgan, G. et al., 2008 [48]; O. 2018 [65]; Phills, J., Deiglmeier, K. and Miller, D., 2008 [67]; M. Mortati, M. and Villari, B. 2014 [68]; Manzini, E. 2015 [69]; Deserti, A., Rizzo, F. and Cobanli, Manzini, E. 2018 [70]; Caetano, A. 2019 [50] |

| Dialogical design | Dialogical design helps to structure multiple ideas coherently using dialogues to capture and map causal systems. This ability to create dialogues between actors and between these actors and their surroundings is natural to human beings. Thus, dialogue is a central element in social design that joins consciousness, human approach and interactions, participants’ relations, power dynamics, and emancipation. | Kimbell L. and Julier, J. 2012 [71]; Banathy, B. 2013 [72]; Cipolla C. and R. Bartholo, 2014 [57]; Irwin, T. 2015 [73]; Klumbytė, G. et al., 2022 [74]. |

| Transitions Design | The domains of transition design contribute to its practices, providing tools to approach system problems so their practitioners can visualise and intervene sharply in the field [68]. While in regenerative design, the wholeness and human nature propel the creation of solutions from a non-human perspective, and with a whole perspective interact with design culture, promoting a transformative aspect from aesthetics to mind models for positive emergences. | Irwin, T. 2015 [73]; Christakis, A. 1998 [75]; Du Plessis, C. 2012 [76]; Wahl, D. 2016 [77]; M. van der Bijl-Brouwer, 2017 [78]; Heller, C. 2018 [43]. |

| Political Design or Design Justice | Political design creates ways for argument and for contesting the status quo, generating spaces and opportunities for debate and changing structures through its critical approach. Thus, one critical social design indicator is its impact and the level of autonomy such design intervention causes. In other words, how such interference shakes or changes the current reality for the better. | Fry, T. 2010 [79]; Freire, K. et al., 2011 [80]; Vazquez, R. 2017 [81]; Schultz T. et al., 2018 [82]; Costanza-Chock, S. 2018 [40]; Serpa, B. et al., 2020 [83]; Collins, P. 2015 [84]; Van Amstel, F. et al., 2022 [85]. |

| Systemic Design | In many fields, social innovation evolved to embrace the systems perspective, moving from a product and service provider to a complex service system view, including public participation and private and citizen representatives. Thus, systems thinking not only enriches social design practices but also propels the creation of more assertive and impactful proposals. Rather than a problem-solving perspective, the systemic design approach enables practitioners to navigate an exploratory journey for leverage points and emergencies that impact the whole. | B. Banathy, H. 2013 [72]; Christakis, A. N. 1998 [75]; Bertalanffy, von L. 1968 [86]; Meadows, D. 2008 [87]; Metcalf, G. 2014 [88]; van der Bijl-Brouwer M. and Malcolm, B. 2020 [89]. |

| Pluriversal and Regenerative Design | Pluriversal Design is embedded within many worlds. It allows a collective construction based on multiple voices, from humans and non-humans. Its principles enrich the design approach on multiple levels, from self-consciousness to collective management. These approaches enrich the design capability to answer social and environmental problems by accepting multiple voices, narratives, and truths. | Klumbytė G. et al., 2022 [74]; Wahl, D. 2016 [77]; Kania J. and Kramer, M. 2013 [90]; Escobar, A. 2015 [91]; Escobar, A. 2018 [92]; Noel, L.-A. 2020 [93]. |

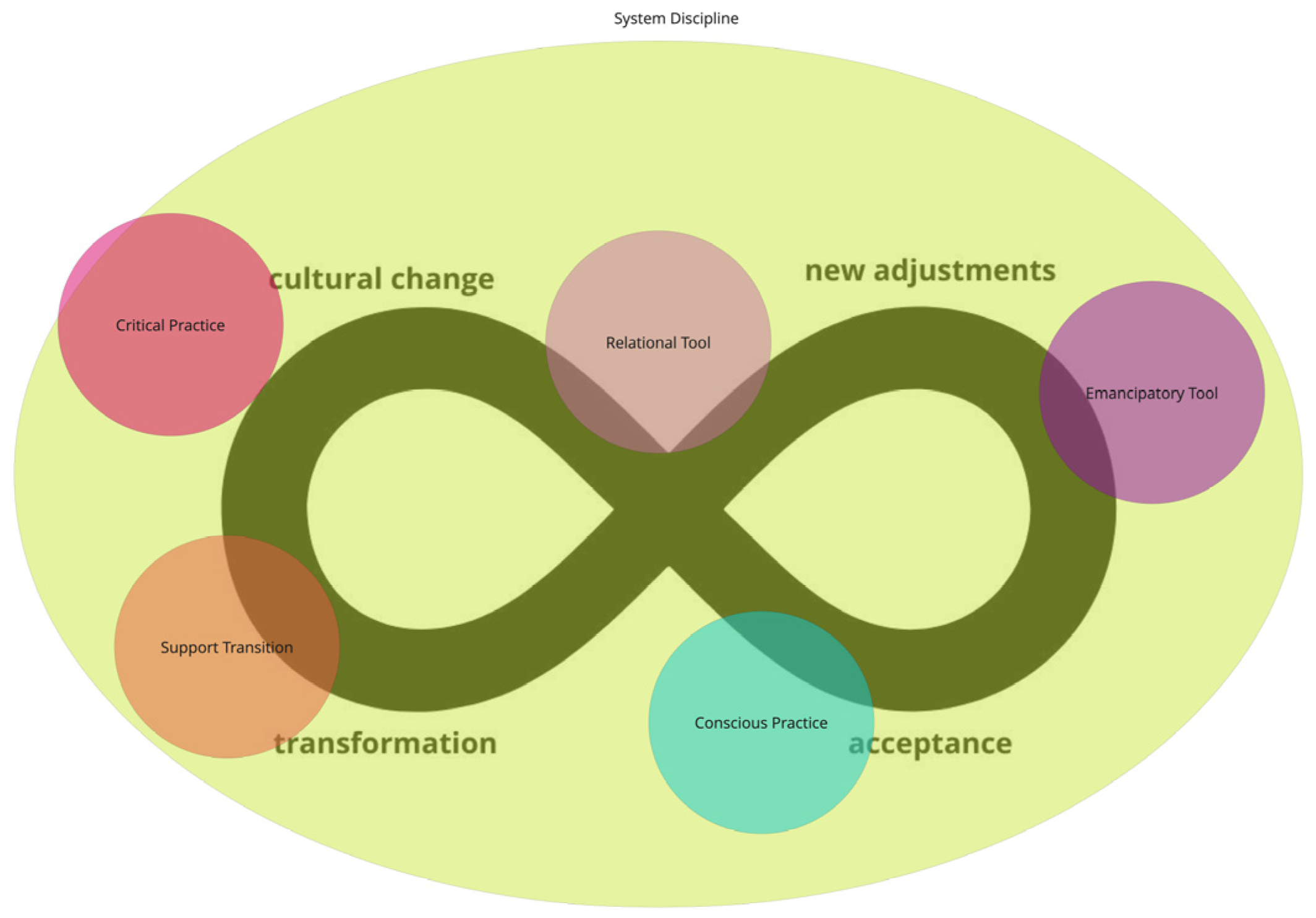

4. The Six Social Design Domains for Social Change in GBV

- Systemic discipline

- 2.

- Critical practice

- 3.

- Conscious practice

- 4.

- Emancipatory tool

- 5.

- Relational tool

- 6.

- Support for transitions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Turning Promises into Action: Gender Equality in the 2030 Agenda. 2018. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2018/sdg-report-gender-equality-in-the-2030-agenda-for-sustainable-development-2018-en.pdf?la=en&vs=4332 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Inglehart, R.; Norris, P. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change around the World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatullo, M. Why a design attitude matters in a world in flux. In Flourish by Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. Systemic Design Principles for Complex Social Systems. In Social Systems and Design; Metcalf, G., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 91–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Eliminating Gender-Based Violence; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shils, E. Tradition and the Generations: On the Difficulties of Transmission. 1984. Available online: https://about.jstor.org/terms (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Inglehart, R.F.; Ponarin, E.; Inglehart, R.C. Cultural change, slow and fast: The distinctive trajectory of norms governing gender equality and sexual orientation. Soc. Forces 2017, 95, 1313–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2023; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pouramin, P.; Nagabhatla, N.; Miletto, M. A Systematic Review of Water and Gender Interlinkages: Assessing the Intersection With Health. Front. Water 2020, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. Tackling Violence against Women and Girls in the Context of Climate Change. 2022, pp. 1–12. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/Tackling-violence-against-women-and-girls-in-the-context-of-climate-change-en.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Bhui, K. Gender, power and mental illness. Structural sources of gender inequality. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beauvoir, S. O Segundo Sexo. Fatos e Mitos, 4th ed.; Difusão Europeia do Livro: São Paulo, Brazil, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. End Violence against Women and Girls; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Women and United Nations Development Programme. The Paths to Equal. Twin Indices on Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality. 2023. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/the-paths-to-equal-twin-indices-on-womens-empowerment-and-gender-equality-en.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockstrom, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, E.D. Gendered Systemic Analysis: Systems Thinking and Gender Equality in International Development. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hull Business School Centre for Systems Studies, Hull, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Kovaleva, M.; Tsani, S.; Țîrcă, D.M.; Shiel, C.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Nicolau, M.; Sima, M.; Fritzen, B.; Lange Salvia, A.; et al. Promoting gender equality across the sustainable development goals. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 14177–14198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme. Goal 5: Gender Equality. 2023. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals/gender-equality (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- United Nations. UNDP Support to the Integration of Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/5_Gender_Equality_digital.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Amatullo, M.; Boyer, B.; May, J.; Shea, A. (Eds.) Design for Social Innovation. Case Studies from around the World; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitz, N.; Carlsen, H.; Skånberg, K.; Dzebo, A. Systems Thinking for SDG. A System View to Improve Coherence. 2019. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep25071.4 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Heise, L. What Works to Prevent Partner Violence? An Evidence Overview. December 2011. Available online: http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/21062/1/Heise_Partner_Violence_evidence_overview.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- United Nations Women. Fact Sheet-Global; United Nations Women: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Policy Brief: The Impact of on Women; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shreeves, R.; Prpic, M. Violence Against Women in the EU: State of Play. 2022. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Faith, B. Tackling online gender-based violence; understanding gender, development, and the power relations of digital spaces. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2022, 26, 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- UNODC. Global Study on Homicide—Gender-Related Killing of Women and Girls. 2018. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/GSH2018/GSH18_Gender-related_killing_of_women_and_girls. (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Desai, B.H.; Mandal, M. Role of climate change in exacerbating sexual and gender-based violence against women: A new challenge for international law. Environ. Policy Law 2021, 51, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Climate Change Exacerbates Violence against Women and Girls. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2022/07/climate-change-exacerbates-violence-against-women-and-girls (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Lisboa, M.; Pasinato, W. Intercâmbio Brasil-União Europeia Sobre o Programa de Combate à Violência Doméstica Contra a Mulher. 2018. Available online: https://www.cnmp.mp.br/portal/images/Publicacoes/documentos/2018/Publica%C3%A7%C3%A3o_Uni%C3%A3o_uropeia_WEB.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Heise, L.L. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence against Woman 1998, 4, 262–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michau, L. Good Practice in Designing a Community-Based Approach to Prevent Domestic Violence. 2005. Available online: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/vaw-gp-2005/docs/experts/michau.community.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Butler, J. Problemas de Género, 1st ed.; Orfeu Negro: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, L.L. Gender Roles a Sociologial Perpective, 6th ed.; Washington University in St. Louis: St. Louis, MO, USA; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttell, F.; Ferreira, R.J. The hidden disaster of COVID-19: Intimate partner violence. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, S197–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walby, S.; Olive, P.; European Union; European Institute for Gender Equality. Estimating the Costs of Gender-Based Violence in the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Katirai, N. Retraumatized in court. Ariz. Law Rev. 2020, 62, 81–124. Available online: https://arizonalawreview.org/pdf/62-1/62arizlrev81.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Costanza-Chock, S. Design Justice: Towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice. In Proceedings of the DRS2018: Catalyst, Limerick, Ireland, 25–28 June 2018; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanek, V.J. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change/Victor Papanek; with an Introduction by R. Buckminster Fuller; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; Available online: https://cercabib.ub.edu/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1033718__SPapanek__Orightresult__U__X4?lang=cat (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Margolin, V.; Margolin, S. A “Social Model” of Design: Issue of practice and Research. Des. Issues 2002, 18, 24–30. Available online: http://direct.mit.edu/desi/article-pdf/18/4/24/1713662/074793602320827406.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Heller, C. The Intergalactic Design Guide Harnessing the Creative Potential of Social Design; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, R. Rhetoric, Humanism and Design; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen, I.; Hush, G. Utopian, Molecular and Sociological Social Design. Int. J. Des. 2016, 10, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C. Introduction: Design and citizenship. Citizsh. Stud. 2010, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, C.; Aránguiz, S.; Montt, C. Formación para el Diseño Social. Percepciones y expectativas entre los estudiantes de la Facultad de Diseño de la Universidad del Pacífico, Chile. In Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Diseño y Comunicación; Universidad de Palermo: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S.; Cheng, L.L.; Hummels, C.; Koskinen, I. Social design: An introduction. Int. J. Des. 2016, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G.; Tucker, S.; Ali, R.; Sanders, B. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated; University of Oxford: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano, A. Designing social action: The impact of reflexivity on practice. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2019, 49, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E.; Jégou, F. Collaborative Services: Social Innovation and Design for Sustainability; Edizioni POLI.design: Milano, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gaitto, J. La función social del diseño o el diseño al servicio social. Cuaderno 2018, 69, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E.; Jégou, F. (Eds.) Cultures of Resilience; Hato Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cipolla, C. Designing for Vulnerability: Interpersonal Relations and Design. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2018, 4, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuori, B.F.; Nicoletti, V.M. Perspectivas Decoloniais para um Design Pluriversal. PosFAUUSP 52 2021, 28, 1–13. Available online: https://www.revistas.usp.br/posfau (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Julier, G.; Kimbell, L. Keeping the system going: Social design and the reproduction of inequalities in neoliberal times. Des. Issues 2019, 35, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, C.; Bartholo, R. Empathy or Inclusion: A Dialogical Approach to Socially Responsible Design. Int. J. Des. 2014, 8, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, J.; Bichardb, J.A. Design anthropology or anthropological design? Towards ‘social design’. Int. J. Des. Creat. Innov. 2017, 5, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratovski, G. Empowerment by Design. J. Des. Bus. Soc. 2016, 2, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, M.; Tomitsch, M.; Gaughwin, M. From human-centred to life-centred design: Considering environmental and ethical concerns in the design of interactive products. J. Responsible Technol. 2022, 10, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.B.; Minyenya-Njuguna, J.; Kamiru, W.K.; Mbugua, S.; Makobu, N.W.; Donelson, A.J. Implementation research and human-centred design: How theory driven human-centred design can sustain trust in complex health systems, support measurement and drive sustained community health volunteer engagement. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, II150–II162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, S. Harnessing the Creative Potential of Social Design. 2018, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.skipprichard.com/harnessing-the-creative-potential-of-social-design/ (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Cohenmiller, A. Leading Change in Gender and Diversity in Higher Education from Margins to Mainstream; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, A.J.P.; van Ael, K. Bringing systemic design in the educational practice: The case of gender equality in an academic context. In Proceedings of the Design Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Designing coalitions: Design for social forms in a fluid world. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2017, 10, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, İ.; Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, İ. Design for Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deserti, A.; Rizzo, F.; Cobanli, O. From Social Design to Design for Social Innovation. The Social Innovation Landscape—Global Trends. 2018. Available online: https://www.socialinnovationatlas.net/fileadmin/PDF/einzeln/01_SI-Landscape_Global_Trends/01_14_From-Social-Design_Deserti-Rizzo-Cobanli.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Irwin, T. The Emerging Transition Design Approach. In Proceedings of the DRS2018: Catalyst, Limerick, Ireland, 25–28 June 2018; Volume 3, pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open Book of Social Innovation; The Young Foundation. 2010. Available online: https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/The-Open-Book-of-Social-Innovationg.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Manzini, E. Autonomy, collaboration and light communities. Lessons learnt from social innovation. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2018, 11, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbell, L.; Julier, J. The Social Design Methods Menu-In Perpetual Beta; The Young Foundation. 2012. Available online: http://www.lucykimbell.com/stuff/Fieldstudio_SocialDesignMethodsMenu.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Banathy, B.H. Guided Evolution of Society: A Systems View; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, T. Transition design: A proposal for a new area of design practice, study, and research. Des. Cult. 2015, 7, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumbytė, G.; Britton, R.L.; Laiti, O.; Prado de O. Martins, L.; Snelting, F.; Ward, C. Speculative Materialities, Indigenous Worldings and Decolonial Futures in Computing & Design. Matter J. New Mater. Res. 2022, 3, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, A.N. Book review: Designing Social Systems in a Changing World. By Bela H. Banathy. Published by Plenum Press, New York, 1996, 372 pp, ISBN 0 306 45251 0. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 1998, 15, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, C. Towards a regenerative paradigm for the built environment. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, D.C. Designing Regenerative Cultures; Triarchy Press: Axminster, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- van der Bijl-Brouwer, M. Designing for Social Infrastructures in Complex Service Systems: A Human-Centered and Social Systems Perspective on Service Design. She Ji 2017, 3, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, T. Design as Politics; Berg: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, K.; Borba, G.; Diebold, L. Participatory Design as an Approach to Social Innovation. Des. Philos. Pap. 2011, 9, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, R. Precedence, Earth and the Anthropocene: Decolonizing Design. Des. Philos. Pap. 2017, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.; Abdulla, D.; Ansari, A.; Canlı, E.; Keshavarz, M.; Kiem, M.; Martins, L.P.; JSVieira de Oliveira, P. What Is at Stake with Decolonizing Design? A Roundtable. Des. Cult. 2018, 10, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpa, B.; Portela, I.; Costard, M.; Batista, S. Political-pedagogical contributions to participatory design from Paulo Freire. PDC 2020, 20, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amstel FM, C.; Noel, L.; Gonzatto, R.F. Design, Oppression and Liberation. Diseña 2022, 21, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Essays on Its Foundation and Development; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, G.S. Creating Social System. In Social Systems and Design; Metcalf, G., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- van der Bijl-Brouwer, M.; Malcolm, B. Systemic Design Principles in Social Innovation: A Study of Expert Practices and Design Rationales. She Ji 2020, 6, 386–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, J.; Kramer, M. Embracing Emergence: How Collective Impact Addresses Complexity. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2013. Available online: http://www.ssireview.org/blog/entry/embracing_emergence_how_collective_impact_addresses_complexity (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Escobar, A. Transiciones: A Space for Research and Design for Transitions to the Pluriverse. Des. Philos. Pap. 2015, 13, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Design for the Pluriverse—Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Noel, L.-A. Envisioning a Pluriversal Design Education. In Pivot 2020: Designing a World of Many Centers; Design Research Society: London, UK, 2020; pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lima, R.; Guedes, G. Sustainable Development Goals and Gender Equality: A Social Design Approach on Gender-Based Violence. Sustainability 2024, 16, 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020914

Lima R, Guedes G. Sustainable Development Goals and Gender Equality: A Social Design Approach on Gender-Based Violence. Sustainability. 2024; 16(2):914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020914

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Raquel, and Graça Guedes. 2024. "Sustainable Development Goals and Gender Equality: A Social Design Approach on Gender-Based Violence" Sustainability 16, no. 2: 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020914

APA StyleLima, R., & Guedes, G. (2024). Sustainable Development Goals and Gender Equality: A Social Design Approach on Gender-Based Violence. Sustainability, 16(2), 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020914