Tomato Waste as a Sustainable Source of Antioxidants and Pectins: Processing, Pretreatment and Extraction Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Green Approaches in Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Food Industry Waste

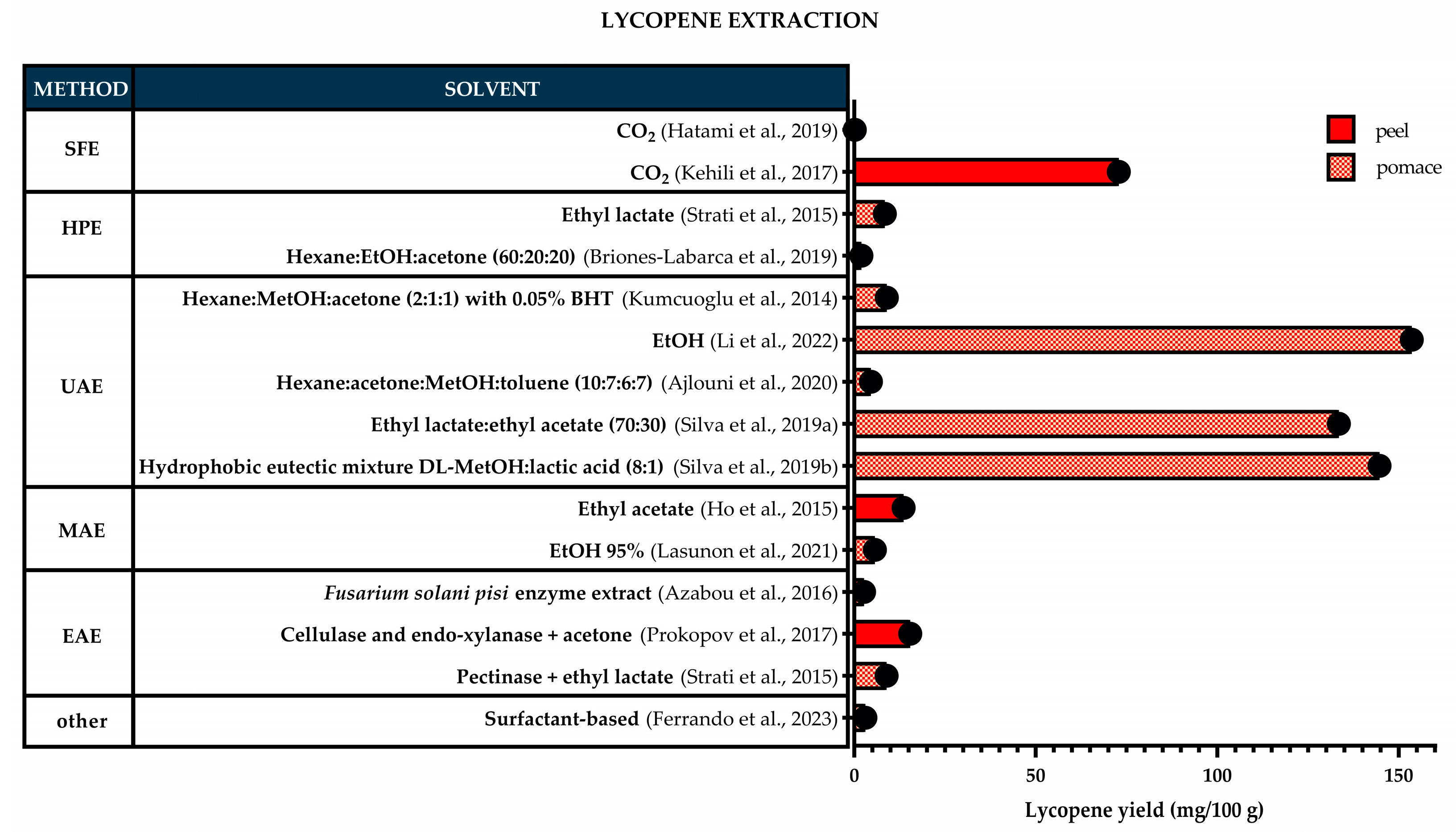

3. Impact of TPW Processing and Extraction Conditions on Carotenoid Yields

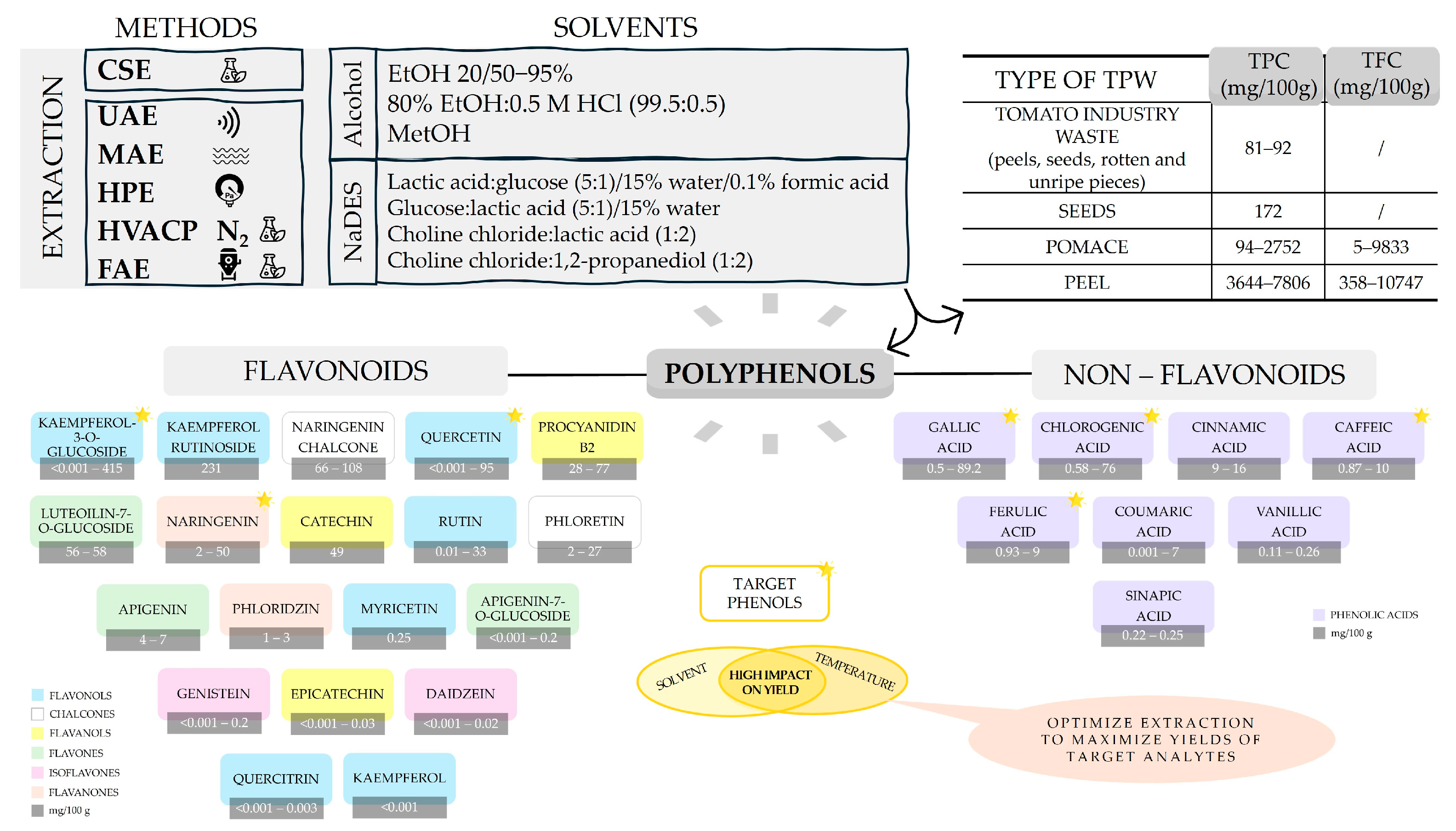

4. Impact of TPW Processing and Extraction Conditions on Polyphenol Yields

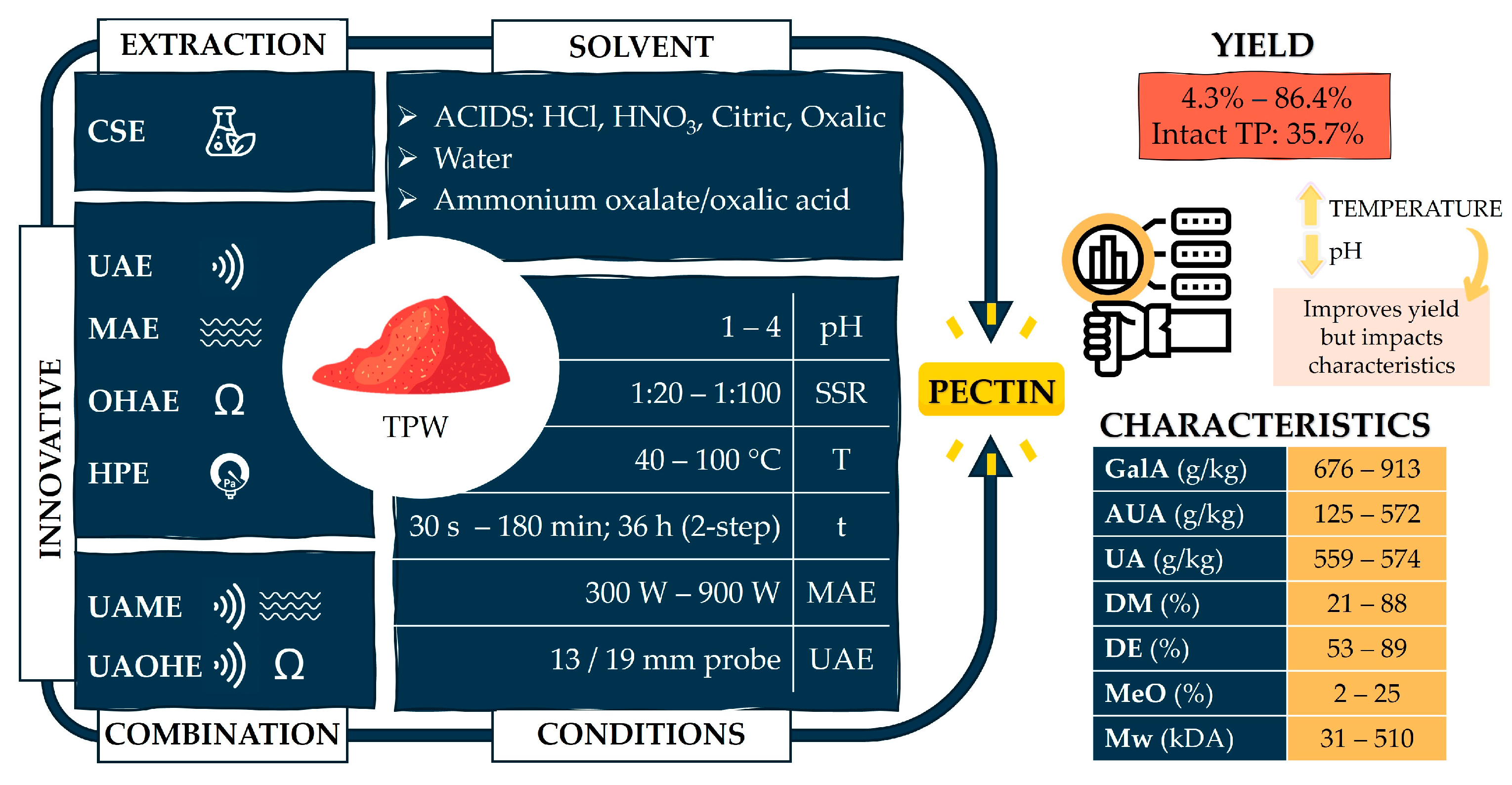

5. Impact of TPW Processing and Extraction Conditions on Pectin Yields

6. Major Obstacles for Widespread Industrial Utilization of TPW as the Source of Bioactive Compounds

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO STATISTICS. World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Yearbook 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casa, M.; Casillo, A.M.; Miccio, M. Pectin production from tomato seeds by environment-friendly extraction: Simulation and discussion. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 87, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WPTC Crop Update as of 25 October 2022—Tomato News. Available online: https://www.tomatonews.com/en/wptc-crop-update-as-of-25-october-2022_2_1812.html (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Nour, V.; Panaite, T.D.; Ropota, M.; Turcu, R.; Trandafir, I.; Corbu, A.R. Nutritional and bioactive compounds in dried tomato processing waste. CYTA J. Food 2018, 16, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pintado, M.E. Integral valorisation of tomato by-products towards bioactive compounds recovery: Human health benefits. Food Chem. 2023, 410, 135319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carillo, P.; D’Amelia, L.; Dell’Aversana, E.; Faiella, D.; Cacace, D.; Giuliano, B.; Morrone, B. Eco-friendly use of tomato processing residues for lactic acid production in campania. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 64, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.R.; Pieltain, M.C.; Castanon, J.I.R. Evaluation of tomato crop by-products as feed for goats. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009, 154, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Gao, R.; Ye, F.; Zhao, G. Sustainable valorisation of tomato pomace: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabi, I.B.; Zannou, O.; Dedehou, E.S.C.A.; Ayegnon, B.P.; Oscar Odouaro, O.B.; Maqsood, S.; Galanakis, C.M.; Pierre Polycarpe Kayodé, A. Tomato pomace as a source of valuable functional ingredients for improving physicochemical and sensory properties and extending the shelf life of foods: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Paengkoum, S.; Taethaisong, N.; Meethip, W.; Surakhunthod, J.; Sinpru, B.; Sroichak, T.; Archa, P.; et al. Sustainable Valorization of Tomato Pomace (Lycopersicon esculentum) in Animal Nutrition: A Review. Animals 2022, 12, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Waste Index Report 2024|UNEP—UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/food-waste-index-report-2024 (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Palansooriya, K.N.; Withana, P.A.; Jeong, Y.; Sang, M.K.; Cho, Y.; Hwang, G.; Chang, S.X.; Ok, Y.S. Contrasting effects of food waste and its biochar on soil properties and lettuce growth in a microplastic-contaminated soil. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, G.; Zhou, M.; Vira, J.; Hess, P.G.; Liu, X.; Paulot, F.; Liu, X. Global food loss and waste embodies unrecognized harms to air quality and biodiversity hotspots. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijosa-Valsero, M.; Garita-Cambronero, J.; Paniagua-García, A.I.; Díez-Antolínez, R. Tomato Waste from Processing Industries as a Feedstock for Biofuel Production. Bioenergy Res. 2019, 12, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinar, J.M.; González, J.F.; Martínez, G. Energetic use of the tomato plant waste. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008, 89, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabouki, I.; Folina, A.; Efthimiadou, A.; Karydogianni, S.; Zisi, C.; Kouneli, V.; Kapsalis, N.C.; Katsenios, N.; Travlos, I. Evaluation of Processing Tomato Pomace after Composting on Soil Properties, Yield, and Quality of Processing Tomato in Greece. Agronomy 2021, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabouki, I.; Efthimiadou, A.; Folina, A.; Zisi, C.; Karydogianni, S. Effect of different tomato pomace compost as organic fertilizer in sweet maize crop. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2020, 51, 2858–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, M.; Laifi, T.; Bennici, S.; Dutournie, P.; Limousy, L.; Agapiou, A.; Papamichael, I.; Khiari, B.; Jeguirim, M.; Zorpas, A.A. Tomato waste biochar in the framework of circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 871, 161959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, F.M.; Madkour, M.; El-Azeem, N.A.; Aboelazab, O.; Ahmed, S.Y.A.; Alagawany, M. Tomato pomace as a nontraditional feedstuff: Productive and reproductive performance, digestive enzymes, blood metabolites, and the deposition of carotenoids into egg yolk in quail breeders. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagawany, M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; El-Rayes, T.K.; Madkour, M.; Loschi, A.R.; Di Cerbo, A.; Reda, F.M. Evaluation of dried tomato pomace as a non-conventional feed: Its effect on growth, nutrients digestibility, digestive enzyme, blood chemistry and intestinal microbiota of growing quails. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrotos, K.; Gerasopoulos, K. Sustainable use of tomato pomace for the production of high added value food, feed, and nutraceutical products. In Membrane Engineering in the Circular Economy. Renewable Sources Valorization in Energy and Downstream Processing in Agro-Food Industry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouatmani, T.; Haddadi-Guemghar, H.; Hadjal, S.; Boulekbache-Makhlouf, L.; Madani, K. Tomato By-Products. In Nutraceutics from Agri-Food By-Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 137–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casa, M.; Miccio, M.; De Feo, G.; Paulillo, A.; Chirone, R.; Paulillo, D.; Lettieri, P.; Chirone, R. A brief overview on valorization of industrial tomato by-products using the biorefinery cascade approach. Detritus 2021, 15, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.J. The role of carotenoids in human health. Nutr. Clin. Care 2002, 5, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R.; Lawrenson, J.G. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023, CD000254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, R.; Xiao, Y.; Fang, J.; Xu, Q. Effect of Carotene and Lycopene on the Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tang, R.; Zhou, R.; Qian, Y.; Di, D. The protective effect of serum carotenoids on cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study from the general US adult population. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1154239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carotenoids Market Size, Share, Trends and Industry Analysis. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/carotenoid-market-158421566.html?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjw0ruyBhDuARIsANSZ3wpIr0XDIAtkLSIGtiC-NZbi16BHHv5doztF8CbBBhBhUp_lQrwk0cQaAsDfEALw_wcB (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Carotenoids Market Size, Share, Analysis & Forecast 2031. Available online: https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/carotenoids-market.html (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Mutha, R.E.; Tatiya, A.U.; Surana, S.J. Flavonoids as natural phenolic compounds and their role in therapeutics: An overview. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issaoui, M.; Delgado, A.M.; Caruso, G.; Micali, M.; Barbera, M.; Atrous, H.; Ouslati, A.; Chammem, N. Phenols, flavors, and the mediterranean diet. J. AOAC Int. 2021, 103, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, P.; Taurisano, V.; Tommonaro, G.; Pasquale, V.; Jiménez, J.M.S.; de Pascual-Teresa, S.; Poli, A.; Nicolaus, B. Biological Properties of Polyphenols Extracts from Agro Industry’s Wastes. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyphenols Market Size, Share, Growth & Trends Report, 2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/polyphenols-market-analysis (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Polyphenols Market Size, Share, Demand Analysis, 2030. Available online: https://www.vynzresearch.com/food-beverages/polyphenols-market (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Zdunek, A.; Pieczywek, P.M.; Cybulska, J. The primary, secondary, and structures of higher levels of pectin polysaccharides. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 1101–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroço, R.F.; Kim, B.; Santacoloma, P.A.; Abildskov, J.; Lee, J.H.; Huusom, J.K. Analysis and model-based optimization of a pectin extraction process. J. Food Eng. 2019, 244, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pectin: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action|DrugBank Online. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB11158 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Pectin Market Size & Share, Industry Analysis Report 2024–2032. Available online: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/pectin-market (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Aksoylu Özbek, Z.; Çelik, K.; Günç Ergönül, P.; Hepçimen, A.Z. A promising food waste for food fortification: Characterization of dried tomato pomace and its cold pressed oil. J. Food Chem. Nanotechnol. 2020, 6, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, T.; Patel, K. Carotenoids: Potent to Prevent Diseases Review. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2020, 10, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, R.; Roselló, S.; Cebolla-Cornejo, J. Tomato as a source of carotenoids and polyphenols targeted to cancer prevention. Cancers 2016, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Carrión, Á.; Calani, L.; de Azua, M.J.R.; Mena, P.; Del Rio, D.; Suárez, M.; Arola-Arnal, A. (Poly)phenolic composition of tomatoes from different growing locations and their absorption in rats: A comparative study. Food Chem. 2022, 388, 132984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouda, K.; Mabrouk, A.M.; Abdelgayed, S.S.; Mohamed, R.S. Protective effect of tomato pomace extract encapsulated in combination with probiotics against indomethacin induced enterocolitis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.C.; Ghalamara, S.; Campos, D.; Ribeiro, T.B.; Pereira, R.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pintado, M. Tomato Processing By-Products Valorisation through Ohmic Heating Approach. Foods 2023, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjeira, T.; Costa, A.; Faria-Silva, C.; Ribeiro, D.; Ferreira de Oliveira, J.M.P.; Simões, S.; Ascenso, A. Sustainable Valorization of Tomato By-Products to Obtain Bioactive Compounds: Their Potential in Inflammation and Cancer Management. Molecules 2022, 27, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, E.; Carpentieri, S.; Pataro, G.; Ferrari, G. A Comprehensive Overview of Tomato Processing By-Product Valorization by Conventional Methods versus Emerging Technologies. Foods 2023, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Yerena, A.; Domínguez-López, I.; Abuhabib, M.M.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Pérez, M. Tomato wastes and by-products: Upcoming sources of polyphenols and carotenoids for food, nutraceutical, and pharma applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 10546–10563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, A.; Kumar, S.; Sunil, C.K.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Rawson, A. Recent advances in the utilization of industrial byproducts and wastes generated at different stages of tomato processing: Status report. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e17063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yu, L.; Pehrsson, P.R. Are Processed Tomato Products as Nutritious as Fresh Tomatoes? Scoping Review on the Effects of Industrial Processing on Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds in Tomatoes. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, A.V.; Srivastava, A.K. Recovery of Bioactive Compounds From Tomato Wastes—Conventional Vs. Emerging Technologies: A Review. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 2016, 1, 541–545. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Srivastav, S.; Sharanagat, V.S. Ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE) of bioactive compounds from fruit and vegetable processing by-products: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 70, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.S.; Ferdosh, S.; Haque Akanda, M.J.; Ghafoor, K.; Rukshana, A.H.; Ali, M.E.; Kamaruzzaman, B.Y.; Fauzi, M.B.; Hadijah, S.; Shaarani, S.; et al. Techniques for the extraction of phytosterols and their benefits in human health: A review. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 2206–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavahian, M.; Sastry, S.; Farhoosh, R.; Farahnaky, A. Ohmic Heating as a Promising Technique for Extraction of Herbal Essential Oils: Understanding Mechanisms, Recent Findings, and Associated Challenges, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 91, ISBN 9780128204702. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Castro, L.M.G.; Moreira, S.A.; Pintado, M.; Saraiva, J.A. Comparison of Emerging Technologies to Extract High-Added Value Compounds from Fruit Residues: Pressure- and Electro-Based Technologies. Food Eng. Rev. 2017, 9, 190–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.W.; Hsu, C.P.; Yang, B.B.; Wang, C.Y. Advances in the extraction of natural ingredients by high pressure extraction technology. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 33, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, O.; Rafińska, K.; Możeński, C.; Buszewski, B. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Materials. J. AOAC Int. 2017, 100, 1624–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picot-Allain, C.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Ak, G.; Zengin, G. Conventional versus green extraction techniques—a comparative perspective. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 40, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolmeh, M.; Jafari, S.M. Applications of Response Surface Methodology in the Food Industry Processes. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Adyatni, I.; Reuhs, B. Effect of Processing Methods on the Quality of Tomato Products. Food Nutr. Sci. 2018, 9, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touami, Y.; Marir, R. Harnessing the power of artificial neural networks methodology and multi-objective optimization for enhanced yield and bioactivity of plants polyphenolic compounds. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2024, 41, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatabadi, Z.; Elhami Rad, A.H.; Farzaneh, V.; Akhlaghi Feizabad, S.H.; Estiri, S.H.; Bakhshabadi, H. Modeling of the lycopene extraction from tomato pulps. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, A.; Deep, K.; Buckley, N.; Nagar, A.K. Optimization of Lycopene Extraction from Tomato Processing Waste Skin Using Harmony Search Algorithm. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2020, 1139, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.V.; Gando-Ferreira, L.M.; Quina, M.J. Tomato Residue Management from a Biorefinery Perspective and towards a Circular Economy. Foods 2024, 13, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’evoli, L.; Lombardi-Boccia, G.; Lucarini, M. Influence of heat treatments on carotenoid content of cherry tomatoes. Foods 2013, 2, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E.S.; Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis, M.; Bowen, P.E. Effects of Heat Treatment on the Carotenoid and Tocopherol Composition of Tomato. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, C1109–C1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Hu, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, S. Thermal conditions and active substance stability affect the isomerization and degradation of lycopene. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 111987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernández, G.B.; Boluda-Aguilar, M.; Taboada-Rodríguez, A.; Soto-Jover, S.; Marín-Iniesta, F.; López-Gómez, A. Processing, Packaging, and Storage of Tomato Products: Influence on the Lycopene Content. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, K.; Dulf, F.V.; Teleky, B.E.; Eleni, P.; Boukouvalas, C.; Krokida, M.; Kapsalis, N.; Rusu, A.V.; Socol, C.T.; Vodnar, D.C. Evaluation of the bioactive compounds found in tomato seed oil and tomato peels influenced by industrial heat treatments. Foods 2021, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, Y.; Gebre, H.; Haile, A. Effects of Pre-Heating and Concentration Temperatures on Physico-Chemical Quality of Semi Concentrated Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Paste. J. Food Process. Technol. 2019, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeoka, G.R.; Dao, L.; Flessa, S.; Gillespie, D.M.; Jewell, W.T.; Huebner, B.; Bertow, D.; Ebeler, S.E. Processing effects on lycopene content and antioxidant activity of tomatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3713–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.; Garcia-Alonso, F.; Ros, G.; Periago, M. Stability of carotenoids, phenolic compounds, ascorbic acid and antioxidant capacity of tomatoes during thermal processing. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2010, 60, 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, M.; Maeda, H.; Fukaya, T.; Goto, M. Effects of Z-Isomerization on the Bioavailability and Functionality of Carotenoids: A Review. Prog. Carotenoid Res. 2018, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M. Z-Isomers of lycopene and β-carotene exhibit greater skin- quality improving action than their all-E-isomers. Food. Chem. 2024, 421, 135954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreou, V.; Dimopoulos, G.; Dermesonlouoglou, E.; Taoukis, P. Application of pulsed electric fields to improve product yield and waste valorization in industrial tomato processing. J. Food Eng. 2020, 270, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataro, G.; Carullo, D.; Bakar Siddique, M.A.; Falcone, M.; Donsì, F.; Ferrari, G. Improved extractability of carotenoids from tomato peels as side benefits of PEF treatment of tomato fruit for more energy-efficient steam-assisted peeling. J. Food Eng. 2018, 233, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, C.; Casadei, E.; Valli, E.; Tura, M.; Ragni, L.; Bendini, A.; Toschi, T.G. Sustainable Drying and Green Deep Eutectic Extraction of Carotenoids from Tomato Pomace. Foods 2022, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, G.D.C.; Díaz-Moreno, A.C. Efecto del proceso de secado por aire caliente en las características fisicoquímicas, antioxidantes y microestructurales de tomate cv. Chonto. Agron. Colomb. 2017, 35, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Iancu, P.; Pleșu, V.; Todașcă, M.C.; Bîldea, C.S. Effect of different drying processes on lycopene recovery from tomato peels of crystal variety. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. B Chem. Mater. Sci. 2019, 81, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G.; Ramachandraiah, K.; Wu, Z.; Li, S.; Eun, J.B. Impact of ball-milling time on the physical properties, bioactive compounds, and structural characteristics of onion peel powder. Food Biosci. 2020, 36, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombino, S.; Cassano, R.; Procopio, D.; Di Gioia, M.L.; Barone, E. Valorization of tomato waste as a source of carotenoids. Molecules 2021, 26, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, T.; Meireles, M.A.A.; Ciftci, O.N. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of lycopene from tomato processing by-products: Mathematical modeling and optimization. J. Food Eng. 2019, 241, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehili, M.; Kammlott, M.; Choura, S.; Zammel, A.; Zetzl, C.; Smirnova, I.; Allouche, N.; Sayadi, S. Supercritical CO2 extraction and antioxidant activity of lycopene and β-carotene-enriched oleoresin from tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum L.) peels by-product of a Tunisian industry. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 102, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Iancu, P.; Plesu, V.; Todasca, M.C.; Isopencu, G.O.; Bildea, C.S. Valuable Natural Antioxidant Products Recovered from Tomatoes by Green Extraction. Molecules 2022, 27, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurić, S.; Ferrari, G.; Velikov, K.P.; Donsì, F. High-pressure homogenization treatment to recover bioactive compounds from tomato peels. J. Food Eng. 2019, 262, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, I.F.; Gogou, E.; Oreopoulou, V. Enzyme and high pressure assisted extraction of carotenoids from tomato waste. Food Bioprod. Process. 2015, 94, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Labarca, V.; Giovagnoli-Vicuña, C.; Cañas-Sarazúa, R. Optimization of Extraction Yield, Flavonoids and Lycopene from Tomato Pulp by High Hydrostatic Pressure-Assisted Extraction; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 278, ISBN 5651220445. [Google Scholar]

- Kumcuoglu, S.; Yilmaz, T.; Tavman, S. Ultrasound assisted extraction of lycopene from tomato processing wastes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 4102–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pettinato, M.; Casazza, A.A.; Perego, P. A Comprehensive Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Lycopene Recovery from Tomato Waste and Encapsulation by Spray Drying. Processes 2022, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajlouni, S.; Premier, R.; Tow, W.W. Improving extraction of lycopene from tomato waste by-products using ultrasonication and freeze drying. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2020, 5, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.A.; Ferreira, T.A.P.C.; Celli, G.B.; Brooks, M.S. Optimization of Lycopene Extraction from Tomato Processing Waste Using an Eco-Friendly Ethyl Lactate–Ethyl Acetate Solvent: A Green Valorization Approach. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 2851–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.A.; Ferreira, T.A.P.C.; Jiao, G.; Brooks, M.S. Sustainable approach for lycopene extraction from tomato processing by-product using hydrophobic eutectic solvents. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.H.Y.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Liceaga, A.M.; San Martín-González, M.F. Microwave-assisted extraction of lycopene in tomato peels: Effect of extraction conditions on all-trans and cis-isomer yields. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasunon, P.; Phonkerd, N.; Tettawong, P.; Sengkhamparn, N. Effect of microwave-assisted extraction on bioactive compounds from industrial tomato waste and its antioxidant activity. Food Res. 2021, 5, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azabou, S.; Abid, Y.; Sebii, H.; Felfoul, I.; Gargouri, A.; Attia, H. Potential of the Solid-State Fermentation of Tomato by Products by Fusarium solani pisi for Enzymatic Extraction of Lycopene; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 68, ISBN 2169764100. [Google Scholar]

- Catalkaya, G.; Kahveci, D. Optimization of enzyme assisted extraction of lycopene from industrial tomato waste. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 219, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopov, T.; Nikolova, M.; Dobrev, G.; Taneva, D. Enzyme-assisted extraction of carotenoids from Bulgarian tomato peels. Acta Aliment. 2017, 46, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, B.O.; Baenas, N.; Rincón, F.; Periago, M.J. Green Extraction of Carotenoids from Tomato By-products Using Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 17, 3017–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachoudi, D.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Enhanced Extraction of Carotenoids from Tomato Industry Waste Using Menthol/Fatty Acid Deep Eutectic Solvent. Waste 2023, 1, 977–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Fang, H.; Gao, Y.; Su, T.; Niu, Y.; Yu, L. (Lucy) Characterization of enzymatic modified soluble dietary fiber from tomato peels with high release of lycopene. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Nguyen, L.T.H.; Nguyen, C.N.; Hertog, M.L.A.T.M.; Nicolaï, B.; Picha, D. Optimization of Lycopene Extraction from Tomato Pomace and Effect of Extract on Oxidative Stability of Peanut Oil. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2023, 73, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, J.; Kay, H.P.; Krishnamurthy, N.P.; Ramakrishnan, N.R.; Aldawoud, T.M.S.; Galanakis, C.M.; Wei, O.C. Extraction of carotenoids from tomato pomace via water-induced hydrocolloidal complexation. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minatel, I.O.; Borges, C.V.; Borges, C.V.; Alonzo, H.; Hector, G.; Gomez, G.; Chen, C.O.; Chen, C.O.; Pace, G.; Lima, P. Phenolic compounds: Functional properties, impact of processing and bioavailability, Phenolic Compounds-Biological Activity. Open Sci. 2017, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, E.; Carle, R.; Astudillo, L.; Guzmán, L.; Gutiérrez, M.; Carrasco, G.; Palomo, I. Antioxidant and antiplatelet activities in extracts from green and fully ripe tomato fruits (Solanum lycopersicum) and pomace from industrial tomato processing. In Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; Volume 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chada, P.S.N.; Santos, P.H.; Rodrigues, L.G.G.; Goulart, G.A.S.; Azevedo dos Santos, J.D.; Maraschin, M.; Lanza, M. Non-conventional techniques for the extraction of antioxidant compounds and lycopene from industrial tomato pomace (Solanum lycopersicum L.) using spouted bed drying as a pre-treatment. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza da Costa, B.; García, M.O.; Muro, G.S.; Motilva, M.J. A comparative evaluation of the phenol and lycopene content of tomato by-products subjected to different drying methods. Lwt 2023, 179, 114644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćetković, G.; Savatović, S.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; Djilas, S.; Vulić, J.; Mandić, A.; Četojević-Simin, D. Valorisation of phenolic composition, antioxidant and cell growth activities of tomato waste. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Parizad, P.; De Nisi, P.; Adani, F.; Sciarria, T.P.; Squillace, P.; Scarafoni, A.; Iametti, S.; Scaglia, B. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the crude extracts of raw and fermented tomato pomace and their correlations with aglycate-polyphenols. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghofrani, S.; Joghataei, M.-T.; Mohseni, S.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Bagheri, M.; Khamse, S.; Roghani, M. Naringenin improves learning and memory in an Alzheimer’s disease rat model: Insights into the underlying mechanisms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 764, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyova, V.; Skiba, M.; Vasyliev, G. Extraction of phenolic compounds from tomato pomace using choline chloride–based deep eutectic solvents. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 1087–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha-Meyer, A.; Palomo, I.; Plaza, A.; Tarone, A.G.; Maróstica Junior, M.R.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G.; Fuentes, E. Platelet Anti-Aggregant Activity and Bioactive Compounds of Ultrasound-Assisted Extracts from Whole and Seedless Tomato Pomace. Foods 2020, 9, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.d.l.Á.; Espino, M.; Gomez, F.J.V.; Silva, M.F. Novel approaches mediated by tailor-made green solvents for the extraction of phenolic compounds from agro-food industrial by-products. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Zhang, R.; Hou, F.; Zhang, M.; Guo, J.; Huang, F.; Deng, Y.; Wei, Z. Comparison of the free and bound phenolic profiles and cellular antioxidant activities of litchi pulp extracts from different solvents. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Yan, H.; Han, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, W.; Xie, C.; Qu, J.; Gong, Z.; Shi, X. Acid and alkaline hydrolysis extraction of non-extractabke polyphenols in blueberries optimisation by response surface methodology. Czech J. Food Sci. 2014, 32, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Salas, P.; Morales-Soto, A.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Phenolic-Compound-Extraction Systems for Fruit and Vegetable Samples. Molecules 2010, 15, 8813–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninčević Grassino, A.; Ostojić, J.; Miletić, V.; Djaković, S.; Bosiljkov, T.; Zorić, Z.; Ježek, D.; Rimac Brnčić, S.; Brnčić, M. Application of high hydrostatic pressure and ultrasound-assisted extractions as a novel approach for pectin and polyphenols recovery from tomato peel waste. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 64, 102424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaleddine, A.; Urrutigoïty, M.; Bouajila, J.; Merah, O.; Evon, P.; de Caro, P. Ecodesigned Formulations with Tomato Pomace Extracts. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, A.; Rodríguez, L.; Concha-Meyer, A.A.; Cabezas, R.; Zurob, E.; Merlet, G.; Palomo, I.; Fuentes, E. Effects of Extraction Methods on Phenolic Content, Antioxidant and Antiplatelet Activities of Tomato Pomace Extracts. Plants 2023, 12, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solaberrieta, I.; Mellinas, C.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. Recovery of Antioxidants from Tomato Seed Industrial Wastes by Microwave-Assisted and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Foods 2022, 11, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakić, M.T.; Pedisić, S.; Zorić, Z.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Grassino, A.N. Effect of microwave-assisted extraction on polyphenols recovery from tomato peel waste. Acta Chim. Slov. 2019, 66, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninčević Grassino, A.; Djaković, S.; Bosiljkov, T.; Halambek, J.; Zorić, Z.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Petrović, M.; Rimac Brnčić, S. Valorisation of Tomato Peel Waste as a Sustainable Source for Pectin, Polyphenols and Fatty Acids Recovery Using Sequential Extraction. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 4593–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Reddivari, L.; Huang, J.Y. Development of cold plasma pretreatment for improving phenolics extractability from tomato pomace. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 65, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, E.; Esmer, O.K.; Sahiner, A. Optimization of the conditions of alkaline extraction of tomato peels and characterization of tomato peel extracts obtained under atmospheric and oxygen free conditions. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2023, 95, e20220077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview, P.M. Pectin Market Overview. 2024, 2022–2027. Available online: https://www.industryarc.com/Report/15977/pectin-market.html (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Circular Economy Action Plan—European Commission. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/circular-economy-action-plan_en (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Mellinas, C.; Ramos, M.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. Recent trends in the use of pectin from agro-waste residues as a natural-based biopolymer for food packaging applications. Materials 2020, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, C.G.; Arora, A.; Shastri, Y. Sustainability Challenges and Opportunities in Pectin Extraction from Fruit Waste. ACS Eng. Au 2022, 2, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alancay, M.M.; Lobo, M.O.; Quinzio, C.M.; Iturriaga, L.B. Extraction and physicochemical characterization of pectin from tomato processing waste. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 2119–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Audenhove, J.; Bernaerts, T.; De Smet, V.; Delbaere, S.; Van Loey, A.M.; Hendrickx, M.E.; Sengkhamparn, N.; Lasunon, P.; Tettawong, P.; Sengkhamparn, N.; et al. Recent trends in the use of pectin from agro-waste residues as a natural-based biopolymer for food packaging applications. Molecules 2021, 18, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassino, A.N.; Brnčić, M.; Vikić-Topić, D.; Roca, S.; Dent, M.; Brnčić, S.R. Ultrasound assisted extraction and characterization of pectin from tomato waste. Food Chem. 2016, 198, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassino, A.N.; Halambek, J.; Djaković, S.; Rimac Brnčić, S.; Dent, M.; Grabarić, Z. Utilization of tomato peel waste from canning factory as a potential source for pectin production and application as tin corrosion inhibitor. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xie, F.; Liu, X.; Luo, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z. Pectin from Black Tomato Pomace: Characterization, Interaction with Gallotannin, and Emulsifying Stability Properties. Starch Stärke 2019, 71, 1800172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengkhamparn, N.; Phonkerd, N. Phenolic Compound Extraction from Industrial Tomato Waste by Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 639, 12040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengar, A.S.; Rawson, A.; Pare, A.; Kumar, K.S. Valorization of tomato processing waste: Characterization and process optimization of pectin extraction. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2019, 7, 3790–3794. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Xie, F.; Lan, X.; Gong, S.; Wang, Z. Characteristics of pectin from black cherry tomato waste modified by dynamic high-pressure microfluidization. J. Food Eng. 2018, 216, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behroozeh, H.; Nikzad, M.; Ghoreyshi, A.A.; Kakoui, N. Extraction of pectin from tomato wastes by ultrasound assisted method and evaluation of its performance as an ecofriendly corrosion inhibitor. Innov. Food Technol. 2021, 9, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengar, A.S.; Rawson, A.; Muthiah, M.; Kalakandan, S.K. Comparison of different ultrasound assisted extraction techniques for pectin from tomato processing waste. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 61, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiler, E.; Jørs, E.; Bælum, J.; Huici, O.; Alvarez Caero, M.M.; Cedergreen, N. The influence of tomato processing on residues of organochlorine and organophosphate insecticides and their associated dietary risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 527–528, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braguglia, C.M.; Gallipoli, A.; Gianico, A.; Pagliaccia, P. Anaerobic bioconversion of food waste into energy: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 248, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristóbal, J.; Caldeira, C.; Corrado, S.; Sala, S. Techno-economic and profitability analysis of food waste biorefineries at European level. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 259, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayana, D.; İçier, F. Effects of Process Conditions on Drying of Tomato Pomace in a Novel Daylight Simulated Photovoltaic-Assisted Drying System. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniceto, J.P.S.; Rodrigues, V.H.; Portugal, I.; Silva, C.M. Valorization of tomato residues by supercritical fluid extraction. Processes 2022, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.W.; Preskett, D.; Krienke, D.; Runager, K.S.; Hastrup, A.C.S.; Charlton, A. Pre-processing Waste Tomatoes into Separated Streams with the Intention of Recovering Protein: Towards an Integrated Fruit and Vegetable Biorefinery Approach to Waste Minimization. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 3463–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, C.; Domínguez, R.; Van Langenhove, H.; Herrero, S.; Gil, P.; Ledón, C.; Dewulf, J. Exergetic analysis in cane sugar production in combination with Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C.; Vlysidis, A.; Fiore, G.; De Laurentiis, V.; Vignali, G.; Sala, S. Sustainability of food waste biorefinery: A review on valorisation pathways, techno-economic constraints, and environmental assessment. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 312, 123575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Barbosa, A.; Advinha, B.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J. Green Extraction Techniques of Bioactive Compounds: A State-of-the-Art Review. Processes 2023, 11, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzella, L.; Moccia, F.; Nasti, R.; Marzorati, S.; Verotta, L.; Napolitano, A. Bioactive Phenolic Compounds From Agri-Food Wastes: An Update on Green and Sustainable Extraction Methodologies. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Zhu, Z.; Koubaa, M.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Orlien, V. Green alternative methods for the extraction of antioxidant bioactive compounds from winery wastes and by-products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 49, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanoglu, E.; Nemli, E.; Tomas-Barberan, F. Novel Approaches in the Valorization of Agricultural Wastes and Their Applications. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6787–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, J.; Singh, R.; Vijayaraghavan, R.; MacFarlane, D.; Patti, A.F.; Arora, A. Bioactives from fruit processing wastes: Green approaches to valuable chemicals. Food Chem. 2017, 225, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soquetta, M.B.; Terra, L.d.M.; Bastos, C.P. Green technologies for the extraction of bioactive compounds in fruits and vegetables. CYTA J. Food 2018, 16, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojić, M.; Mišan, A.; Tiwari, B. Eco-innovative technologies for extraction of proteins for human consumption from renewable protein sources of plant origin. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 75, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Valenzuela, L.S.; Ballesteros-Gómez, A.; Rubio, S. Green Solvents for the Extraction of High Added-Value Compounds from Agri-food Waste. Food Eng. Rev. 2020, 12, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martín, E.; Forbes-Hernández, T.; Romero, A.; Cianciosi, D.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Influence of the extraction method on the recovery of bioactive phenolic compounds from food industry by-products. Food Chem. 2022, 378, 131918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Nuñez, O.; Granados, M.; Sentellas, S.; Saurina, J. An overview of the extraction and characterization of bioactive phenolic compounds from agri-food waste within the framework of circular bioeconomy. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 161, 116994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnik, P.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Barba, F.J.; Cravotto, G.; Binello, A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Shpigelman, A. Innovative “green” and novel strategies for the extraction of bioactive added value compounds from citruswastes—A review. Molecules 2017, 22, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, K.; Shahbaz, H.M.; Kwon, J.H. Green Extraction Methods for Polyphenols from Plant Matrices and Their Byproducts: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert-Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Strube, J.; Uhlenbrock, L.; Gunjevic, V.; Cravotto, G. Green extraction of natural products. Origins, current status, and future challenges. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Pintado, M.; Oliveira, A.L.S. Natural bioactive compounds from food waste: Toxicity and safety concerns. Foods 2021, 10, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devkota, L.; Montet, D.; Anal, A.K. Regulatory and Legislative Issues for Food Waste Utilization. In Food Processing By-Products and Their Utilization; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwal, T.; Chemat, F.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Cravotto, G.; Jaiswal, D.K.; Bhatt, I.D.; Devkota, H.P.; Luo, Z. Recent advances in scaling-up of non-conventional extraction techniques: Learning from successes and failures. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 127, 115895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingret, D.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Bourvellec, C.L.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Chemat, F. Lab and pilot-scale ultrasound-assisted water extraction of polyphenols from apple pomace. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonkird, S.; Phisalaphong, C.; Phisalaphong, M. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of capsaicinoids from Capsicum frutescens on a lab- and pilot-plant scale. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008, 15, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petigny, L.; Périno, S.; Minuti, M.; Visinoni, F.; Wajsman, J.; Chemat, F. Simultaneous microwave extraction and separation of volatile and non-volatile organic compounds of boldo leaves. From lab to industrial scale. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 7183–7198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Périno, S.; Pierson, J.T.; Ruiz, K.; Cravotto, G.; Chemat, F. Laboratory to pilot scale: Microwave extraction for polyphenols lettuce. Food Chem. 2016, 204, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Pereira, R.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pintado, M.E. Extraction of tomato by-products’ bioactive compounds using ohmic technology. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 117, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hilphy, A.R.; Al-Musafer, A.M.; Gavahian, M. Pilot-scale ohmic heating-assisted extraction of wheat bran bioactive compounds: Effects of the extract on corn oil stability. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Aslam, R.; Makroo, H.A. High pressure extraction and its application in the extraction of bio-active compounds: A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e12896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, S.; Gemmell, C.; Lau, A.T.Y.; Arvaj, L.; Strange, P.; Gao, A.; Barbut, S. High pressure processing during drying of fermented sausages can enhance safety and reduce time required to produce a dry fermented product. Food Control 2020, 113, 107224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelyn; Milani, E.; Silva, F.V.M. Comparing high pressure thermal processing and thermosonication with thermal processing for the inactivation of bacteria, moulds, and yeasts spores in foods. J. Food Eng. 2017, 214, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, N.S.; Buckow, R.; Versteeg, C. Quality-related enzymes in fruit and vegetable products: Effects of novel food processing technologies, part 1: High-pressure processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 24–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, S.J. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Food Production and Processing: An Introduction; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klöpffer, W.; Grahl, B. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A Guide to Best Practice. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A Guide to Best Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, L.; Pontalier, P.Y.; Sablayrolles, C. Life cycle assessment (LCA) applied to the process industry: A review. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.D.; Dhamole, P.B. Techno economic and life cycle assessment of lycopene production from tomato peels using different extraction methods. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 14, 25495–25511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Examined Parameters | Yield/Properties | Physico-Chemical and Rheological Characteristics | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | CSE: T > 85 °C | ↑ yield | [127] | |

| CSE: 80 °C vs. 60 °C | ↓ yield | ↑ MeO (9.0 vs. 6.2) ↑ AUA (572 g/kg vs. 352 g/kg) ↑ DE (slightly, 89% vs. 85%); | [129] | |

| UAE: 80 °C vs. 60 °C | ↑ yield (slightly) | ↓ MeO ↓ AUA (slightly) ↓ DE (slightly) | ||

| UAE (bath, pH 2.5): 40 °C vs. 60 °C vs. 80 °C | 4% vs. 6% vs. 9% | [132] | ||

| UAE: 40 °C vs. 20 °C | ↑ yield better anticorrosion properties | [135] | ||

| pH | pH 2 vs. pH 4.5 | ↑ yield | DM (77% vs. 88%) GalA (no effect) intrinsic viscosity (4.2 dL g−1 vs. 1.8 dL g−1) viscosimetric average molecular weight (94.6 kDa vs. 30.5 kDa) | [127] |

| pH 1.6 vs. pH 4 | ↑ yield | DM (74% vs. 67%) UA (no effect) | [128] | |

| UAE: pH 1.0 vs. pH 1.5 vs. pH 2.0 | ↑ yield at decreasing pH | ↑ total carboxyl groups with higher pH (at SSR 1:20; no effect at higher SSR) | [93] | |

| CSE: HCl (pH 1.5) vs. ammonium-oxalate + oxalic acid (pH 4.5) | ↑ yields | ↑ GalA (84% vs. 79%) ↓ DM (20.8% vs. 29.3%) in HCl extracts | [131] | |

| UAE/MAE/OHAE: pH 2 vs. pH 1/pH 1.5 | ↓ yields at pH 2 | [133] | ||

| Duration of Extraction | prolonged CSE (5 to 10 min) | ↑ IST ↑ CST ↑ SDR | [127] | |

| MAE (300 W): 3 min vs. 5 min vs. 10 min | 9.4% vs. 15.1% vs. 31.6% (effect is less significant at higher MWP (450 and 600 W)) | the effect of the duration of MAE on carboxyl group content is not clear | [93] | |

| HPE: 10 min vs. 45 min | 6.6% vs. 9.2% | ↑ AUA (31% vs. 43%) | [115] | |

| prolonged MAE/UAE (30–150 s) | ↑ yields | [136] | ||

| prolonged OHAE (90–210 s) | ↑ yields | [133] | ||

| prolonged: UAE up to 10 min (450 W and 600 W) or 2 min (750 W); MAE up to 3 min (900 W) or 4 min (750 W); OHAE up to 5 min; UAME up to 8 min (450 W and 750 W) or 10 min (600 W) | ↑ yields | [133] | ||

| prolonged UAE up to 20 min | ↑ yields (further prolongation is not relevant for yields) | [132] | ||

| prolonged UAE (15–90 min, 60 °C/80 °C) | ↑ yields (15.2% vs. 17.2%/16.3% vs. 18.5%) | ↓ MeO (5.56 vs. 4.50/4.5 vs. 3.8) ↓ AUA (37.6 vs. 31.4/33 vs. 27) ↓ DE (87.9 vs. 84.8/89 vs. 77) | [129] | |

| Extraction Method | CSE (36 h) vs. UAE (30–180 min) | 31% vs. 35.5% | type of extraction does not influence characteristics of pectins (they are primarily affected by temperature and duration of extraction) | [129] |

| UAE (20 min, pH 1.5) vs. MAE (10 min, pH 1.5) | 282.5 g/kg vs. 301.2 g/kg | ↓ GalA | [93] | |

| UAE vs. MAE vs. OHAE | 98 g/kg vs. 120 g/kg vs. 80 g/kg | [133] | ||

| UAE vs. MAE vs. OHAE vs. UAME vs. UOHAE | 152 g/kg vs. 254 g/kg vs. 106.5 g/kg vs. 180 g/kg vs. 146 g/kg | [133] | ||

| HPE vs. CSE (30 min)/CSE (45 min) | ↑ yields (14–15%) | [115] | ||

| Combined techniques (subsequent UAE + MAE − increases yields (340.6 g/kg vs. 282.5 (UAE) and 301.2 g/kg (MAE))) | subsequent UAE + MAE has higher total carboxyl groups content compared to UAE compared to MAE | [93] | ||

| Extraction Solvent | UAE: citric acid vs. nitric acid/hydrochloric acid | ↑ yields | ↑ AUA DM (no effect) | [132] |

| CSE:HCl (pH 1.5) vs. ammonium-oxalate + oxalic acid (pH 4.5) | ↑ yields | ↑ GalA (83.9% vs. 78.2%) ↓ DM (20.8% vs.29.3%) | [131] | |

| UAE: citric acid vs. oxalic acid/HCl | ↑ yields (18.5%) | [135] | ||

| SSR | UAE: 1:20 vs. 1:30 vs. 1:50 | 17% vs. 26% vs. 32% | total carboxyl groups (0.15 vs. 1.1 vs. 1.2) | [93] |

| UAE/MAE/OHAE: SSR increased from 1:50 to 1:70 | yields (no effect) | [133] | ||

| MWP | higher MWP at short extraction periods (3–5 min) | ↑ yields | the effect on carboxyl group content is not clear | [93] |

| Pretreatment of Raw Material | HPE | ↑ yield (864 g/kg vs. 473 g/kg) | ↓ DM ↑ Mw | [128] |

| Posttreatment of Pectin | dynamic high pressure microfluidization (0–160 MPa) | ↑ MeO (1.73 to 3.11%) ↑ AUA (19.38 to 28.37%) ↑ DE (50.77 to 62.15%) ↑ particle size | rheological properties (apparent viscosity, consistency index and flow behavior index) were significantly changed | [131] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radić, K.; Galić, E.; Vinković, T.; Golub, N.; Vitali Čepo, D. Tomato Waste as a Sustainable Source of Antioxidants and Pectins: Processing, Pretreatment and Extraction Challenges. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219158

Radić K, Galić E, Vinković T, Golub N, Vitali Čepo D. Tomato Waste as a Sustainable Source of Antioxidants and Pectins: Processing, Pretreatment and Extraction Challenges. Sustainability. 2024; 16(21):9158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219158

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadić, Kristina, Emerik Galić, Tomislav Vinković, Nikolina Golub, and Dubravka Vitali Čepo. 2024. "Tomato Waste as a Sustainable Source of Antioxidants and Pectins: Processing, Pretreatment and Extraction Challenges" Sustainability 16, no. 21: 9158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219158

APA StyleRadić, K., Galić, E., Vinković, T., Golub, N., & Vitali Čepo, D. (2024). Tomato Waste as a Sustainable Source of Antioxidants and Pectins: Processing, Pretreatment and Extraction Challenges. Sustainability, 16(21), 9158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219158