Abstract

This research has been developed through a literature review on the importance of and current approach in the education system to the present environmental and ecosystemic crisis and the training of future generations in degrowth in the Spanish education system. To this end, a systematic literature review (SLR) has been carried out following the standards of the PRISMA declaration. In total, 40 articles published between January 2005 and March 2024 were selected from the following databases: Scopus, Dialnet, Web of Science and Scielo. The findings show it is a relevant topic in school education as a concern, but it is not reflected in educational practice; that it has been incorporated into the curriculum, but sporadically, decontextualised and more focused on ‘sustainable development’; also, it lacks critical questioning of the unlimited growth and consumption model that capitalism entails. The study concludes that it is crucial to incorporate degrowth in a transversal way in education at all schooling levels, and to reform the curricula of the faculties of education in all universities so that the pedagogy of degrowth is a priority in the training of future teachers.

1. Introduction

The capitalist growth society is unsustainable because it does not consider the planet’s capacity for regeneration and is profoundly unequal [1,2,3,4,5]. It has been shown that 20% of the world’s population owns 86% of the natural resources, while 1.3 billion people suffer extreme poverty; that is, living on less than one dollar a day [6,7]. Thus, the starting point is not the same for everyone. The enriched global North establishes the rules of the international game, organising a system of unequal exchange; thus, the global South is sacrificed as extractivist zones to continue plundering the planet’s resources and enhancing consumption of unnecessary products; the result of advertising-driven desires [8].

The present times are characterised by a profound crisis affecting the relationships of people and societies with nature [9], as well as the equitable access to the goods and resources provided by the Earth. Over the last decades, consumption has increased so exponentially that it has led to a way of life that poses a serious threat to the future of humanity and life on this planet [10]. Moreover, the irrational increase in consumption has become an indicator of unhappiness—rather than a sign of the opposite—despite the recurrent messages generated by advertising and corporate marketing [11].

Therefore, it is crucial to rethink how to move forward in the construction of a society and a planet that develops a more respectful and sustainable model, as opposed to the present model of production and consumption, and to the tremendous global socio-environmental deterioration caused by capitalism in our ecosystem. It must also be pointed out that research and experts have been denouncing this since the 1970s [12,13,14,15,16]. The education system and the initial university training of future teachers play a key role in the way future generations are being educated in the face of the situation described.

1.1. Climate Crisis

One of the most visible aspects of this ecosystem crisis is climate change (hereafter, CC). In 2024, the 21st of July was the hottest day ever recorded worldwide, according to data from the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. In Europe, there have been twice as many days above 40 °C as in the entire 1980s [17]. This is a progressive trend that has been observed in recent years [9].

The most advisable proposal would be to radically transform the energy model based on the intensive use of fossil hydrocarbons in an urgent and planned manner. However, the truth is that the economic and social model, as well as a large part of society, has not realised the urgency and necessity of this change, given that this would imply a radical transformation of the way of life and the individual and collective mentality in a society governed by capitalist-driven growth [18].

In this scenario, it is necessary for academic educational research to give the climate emergency the transcendental importance that derives from its threat potential. Further, it is important to set agreed programmes and agendas that give priority to improving the knowledge and pedagogical training of current and future generations. In this way, contemporary societies become aware of the seriousness of this problem, demand effective response policies and actions, and actively participate in their implementation [19].

CC is postulated as the most important challenge for humanity this century at a scientific level and in terms of the survival of the species and the planet [20]. Nevertheless, the apathy seemingly shown by part of the social sciences and education towards this problem—on the current trajectory, towards a generalised collapse—is disconcerting [18].

1.2. Education in the Face of Climate Collapse

González-Gaudiano and Meira-Cartea [18] indicate that resistance to change in the face of current environmental problems is mostly due to individuals and communities not having ‘objective’ and ‘real’ knowledge of what the world is like and how it works. Therefore, education should focus on transmitting scientific knowledge that allows them to build a real picture of their environment.

The insistence on turning Environmental Education into an essentially ‘scientific’ education often expresses such deconstructive projects [21]. This requires approaches, methodologies and tools that are not yet widely available in the classroom [18]. Another aspect worth mentioning is that educating in another model of life implies having to voluntarily give up certain comforts offered by the current way of life to combat CC, as well as demanding political measures to change the global consumption model demanded by capitalism [22].

Therefore, we must be aware that social, structural, political and personal change regarding habits, mentalities and practices entails resistance and defensive attitudes. As other changes, the most common reaction is that of a certain skepticism, if not opposition or distancing and, above all, the belief in future technological solutions that do not always come in time or are not even possible [23].

2. Research Objectives

The aim of this research has been to conduct a systematic review of the academic literature (SLR) regarding the importance and current approach present in the Spanish education system, especially in the training of future teachers. The process of teaching and learning involved in the issue of the environmental and ecosystemic crisis we are experiencing today is studied. This objective has been broken down into the following questions and analysed through the SLR methodology:

- -

- Does the current literature show a concern for this issue in the field of education, given the number and importance of publications on the subject?

- -

- What knowledge, epistemological conceptualisation and understanding of the causes, consequences and ways of dealing with the phenomenon predominate among teachers and students regarding the climate crisis?

- -

- What options or proposals for solutions and approaches are put forward in the education system regarding the way out of this crisis?

- -

- Does there appear to be a concern for training future teachers in how to teach and work educationally on these issues in current teacher training, as can be seen from the number and importance of the publications found on the subject?

- -

- Is there an increase in the number of publications on this subject related to current or recent educational policies implemented in Spain?

3. Methodology

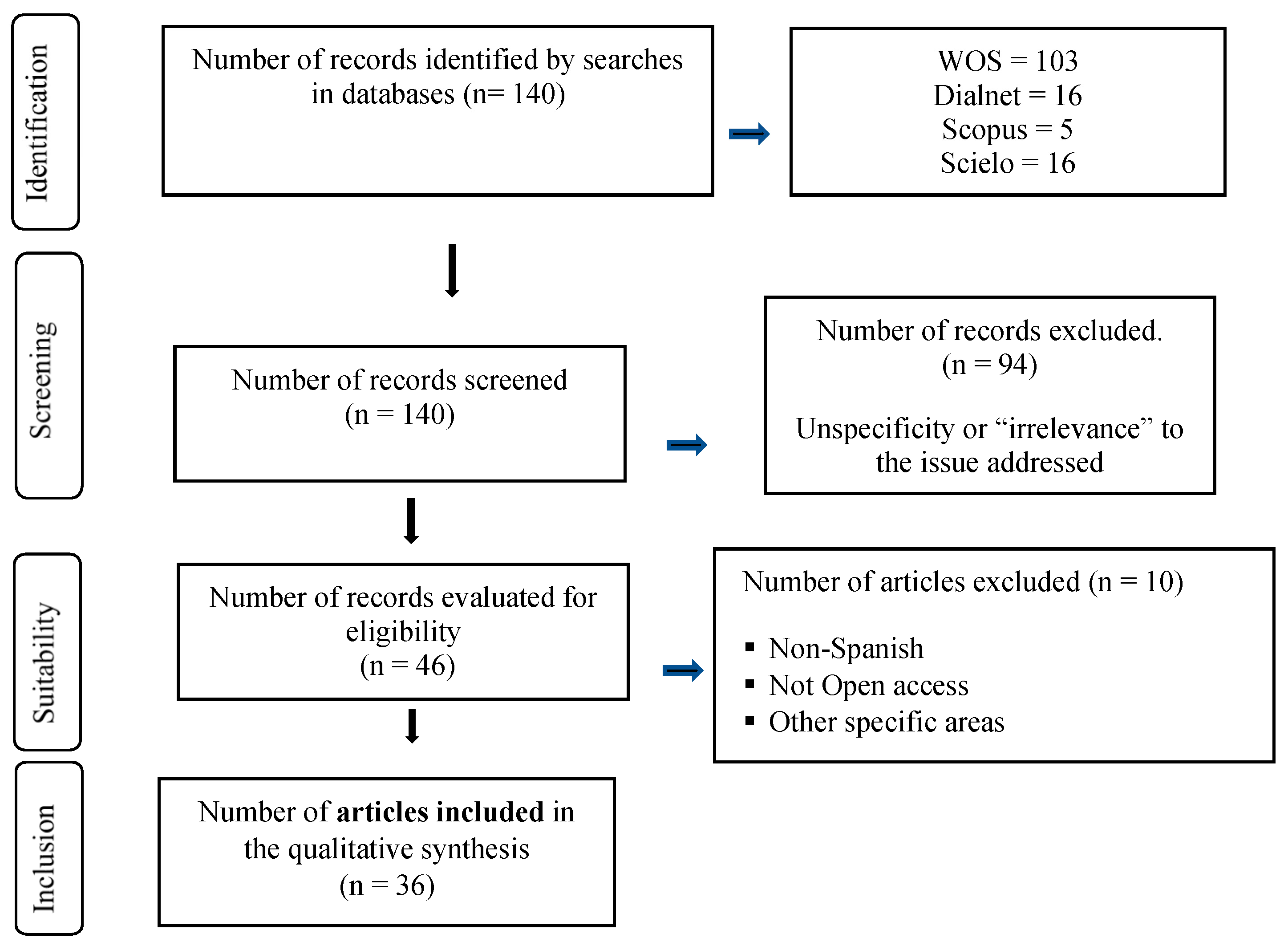

A systematic literature review (SLR) was carried out in the reference databases (WOS, Scopus, Scielo and Dialnet), with quality standards and international recognition, of all publications between January 2005 and March 2024. The quality standards of the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) (Supplementary Material). protocol for a systematic review [24,25] were considered for this SLR; this has been helpful to avoid, or at least minimise, possible biases [26]. The PRISMA 2020 guidelines followed to conduct the SLR were: (1) perform a chain search to identify the research with the highest impact, (2) especially emerging and most cited research and studies, (3) following inclusion and exclusion phases and criteria to select the documents.

Firstly, the key words or key descriptors of the research applied in this SLR were determined for the databases: degrowth and education (Table 1). To select the articles, inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined based on the established objectives; the aim being to identify peer-reviewed scientific articles based on quantitative and/or qualitative methodologies, as well as literature review articles or essays.

Table 1.

Database search procedure.

After the first review, in which 140 documents appeared between 2005 and 2024, 94 articles were discarded in the first screening phase, applying certain inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2): articles from research in Anglo-Saxon countries (given that the research focused on the Spanish education system), articles that were not open access, articles from other specific fields such as Chemistry, Biology, Economics, etc. where the educational component was not related in any way to the possibility of degrowth as a means to stop the effects of CC. Subsequently, in the suitability phase, additional inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to discard articles by analysing the title, abstract and content of each article. Articles were discarded based on:

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- -

- Descriptive experiences of didactic or methodological applications that do not provide an in-depth epistemological approach;

- -

- Reviews of other publications or experiences conducted;

- -

- Studies prior to 2005.

To conduct the systematic search, publication from 2005 to 2024 of articles indexed in the databases referred to were analysed. The search phrases using Boolean operators are described below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Search organisation.

According to all these criteria, the number of records excluded after the first review was 94, leaving 46 articles, and 10 more were eliminated in the second screening. Therefore, 36 articles were finally included in this SLR work. This process is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the different SLR phases. Source: elaborated by the authors.

4. Results and Discussion

This mapping of the updated state of the art has enabled the identification of the different epistemological positions, i.e., in relation to the approach and form of educational implementation in the face of the climate and ecosystem crisis, as well as in teacher training in this field. Below are the results of the SLR conducted based on the categories established around the research objectives.

4.1. Importance in the Field of Education

In this category of analysis, we have come across several fundamental findings. The first and most significant result in this category is that the crisis and CC (a) is a relevant issue in terms of the concern expressed by the educational community, but that (b) it is not sufficiently reflected in daily educational practice in classrooms and educational centres in coherence with this expressed concern [27]; and that (c) degrowth has not yet appeared in the educational field, given that there is very little literature, studies and research in this field [28,29].

A second finding is the topic has been incorporated in some textbooks and curricular materials of certain subjects, but (a) sporadically in most cases [10,30], (b) in a decontextualised and isolated way with respect to only certain environmental problems [31,32], (c) from a perspective that minimises the impact and consequences they are provoking [28,33], that (d) does not question the model of unlimited growth and consumption that capitalism entails [28], as well as (e) from an approach that entrusts the solution to the technology of the future with a certain magical air of displacement of the problem to the future [27,34].

The third result refers to the fact that studies have been developed mainly on three fundamental aspects: (a) the educational community’s perception of the issue [35,36], (b) the social representations that are embodied in this community on the subject studied [37,38], and (c) the way the issue is addressed in the educational field [18,22,27,30,32,33,39,40]. These three sections will be developed in the following categories analysed.

The fourth result has to do with the educational approach to the climate crisis. In this regard, two relevant aspects are noted: (a) disciplinary educational practices prevail over interdisciplinary or cross-disciplinary proposals that enable complex approaches [33,35,41]; and (b) there is a predominance of personal awareness-raising approaches that do not sufficiently problematise or delve into the structural causes, the global impacts involved and the possible ways of going beyond or overcoming the capitalist system of growth [42,43].

A fifth element found refers to the channels of knowledge on this topic, with the greatest impact on students. The role of social networks and digital media is highlighted, as the age of pupils increases in relation to the information obtained [30,31,44]. According to research, this means that schools should be aware of the influence of digital media—Internet, social networks, TV—in shaping students’ knowledge. Although these media are also used in the classroom in a didactic way, young people have access to a wide choice of information on the subject, ranging from a critical and global perspective to highly questionable denialist and conspiratorial views [45]. According to educational research, schools have a fundamental role to play in this regard in terms of selecting and analysing information sources and their reliability, as well as contrasting scientific information with other information; for instance, news that emphasizes pollution as the origin of the climate crisis and rising temperatures as the effect [30,32,46].

The sixth result refers to the social representation that seems to predominate in teachers about the crisis and the CC [46,47]. It should be noted that the information they have allows them to understand the phenomenon from more complex visions than those usually shared by students. Though focusing mainly on the biophysical aspects, they consider economic and political dimensions as well as the repercussions of its impacts on the international, national and regional spheres. Nevertheless, a critical vision that questions the system does not predominate; it focuses more on personal or community awareness-raising approaches that do not involve conflicts with power or the system [27,28,35].

4.2. Epistemological Conceptualisation from Education

In this category, we also point out six significant elements that seem relevant to us in the results found in this SLR. The participants in various studies, which include teachers and students, perceive the phenomenon of the climate crisis as real and a worrying situation at present [37]. Therefore, the first result to highlight in this category is that both are predominantly aware of the phenomenon and its seriousness [19,39].

The second aspect that stands out is the conception of its causes. In the research reviewed [10,19,21,39,43,48], the most frequently identified causes operate (a) at the individual level, linked to both human selfishness and consumerism, (b) at the structural level related to capitalism, overpopulation and pollution, (c) at the social level with lack of education and corruption, and (d) at the economic level with low public budgets and lack of sanctions for polluting industries.

The third group of results are those indicated by the educational community on how the consequences of the climate crisis are conceived and understood. The following are repeatedly identified and pointed out as such: (a) at a global level, environmental impacts [19,49], and (b) at the personal level diseases, behavioural and mood changes [21,35,36,50,51,52].

A fourth aspect refers to the knowledge acquired through education. It seems that a proportion of the students lack solid information about certain basic issues—greenhouse gases, carbon emissions trading and so on—and show a confused or erroneous knowledge about these topics, including aspects related to environmental policy and management [37,53]. Nevertheless, students do express their willingness to participate in the development of actions in favour of the environment [50]. However, it is noted that they tend to see the problem as something temporarily distant, which makes it difficult to take appropriate and timely action as soon as possible [53].

The fifth finding is that epistemologically a representation of the educational community is perceived to be more focused on the catastrophic consequences of the problem than on solutions [31,48,54,55]. This reveals a representation marked by negative emotions and a pessimistic tone, which prevents visualizing possible alternatives and solutions to a threat potential [49].

The sixth result worth highlighting is that students seem to identify causes, consequences and strategies in the face of the climate crisis, but through direct and simple associations. They identify the burning of fossil fuels as a cause, but not consumption habits; they recognise direct strategies to combat climate change, such as the use of urban transport, but do not perceive the relationship between local consumption strategies and the reduction of the transport of goods [31]. Socio-economic consequences are the least identified by students [56], despite the obvious correlation between them and CC intensification [57]. Most of the social representations allude only to the ecological dimension, taking up some elements of the social dimension and not considering the political, economic, cultural and philosophical dimensions [45,50].

4.3. Strategies for Educational Intervention

In this category, we have included all the proposals put forward regarding how to intervene educationally at school and in extracurricular and complementary activities, etc. These proposals address the problem of the planet’s limits, the distribution of its scarce resources, interdependence and eco-dependence, as well as the predatory and unsustainable behaviour of capitalism with respect to the biosphere that sustains life. The following are the results obtained in the SLR.

There are two main ways in which students channel their intervention: (a) activism and (b) remedial actions [30,50]. Research describes experiences and proposals from a sector of students who insist on confrontational ‘hyperactivism’—actions that are both symbolic and directly confrontational—to denounce the consequences of CC and the overcoming of the planet’s limits. These actions seek to draw attention and generate a certain media agenda to pressure the public authorities to act [30]. Another sector focuses more on awareness raising, remedial actions and local action to mitigate or minimise the effects of climate change as far as possible, understanding that structural, global and cultural change in society is not their responsibility [50].

It is proposed that educational intervention in schools should focus on (a) transmitting knowledge and proven information that raises awareness of the effects and consequences of CC and the energy and ecosystem crisis [35,42,52]; (b) investigating the phenomenon, its consequences and possible alternatives with students and the educational community, to enhance their personal and social responsibility [41,50]; (c) putting measures into practice, implementing strategies and commitments in schools and their environment; i.e., specific measures that show and set examples consistent with the change proposed [10,40,51]; (d) proposing service-learning actions and programmes with this perspective which impact on the social context and help to transform it in this sense [10,19,23,32,54,58]; and (e) exposing the model that sustains the situation and involving the educational community with social movements and activists in their environment to fight against CC and the system that maintains it [22,33,42,45,53].

Of these educational intervention strategies, those focusing on or more related to raising awareness, creating spaces for reflection and disseminating information on sustainability and care for the environment seem to predominate [19]. However, in those approached from a degrowth perspective, the basic strategy proposed is to learn how to adjust to a new situation in a limited world [52]. Such adjustment involves developing educational responses to three challenges. The first challenge is the decrease in resources associated with a possible institutional crisis requiring local responses. This implies educating in autonomy and self-reliance, and more specifically in ‘know-how’ based on the management of more resilient technologies. A second challenge has to do with the growth of uncertainty and vulnerability. In the face of complex and novel problems and situations of increased risk, we need to enhance a systemic understanding of the world, research capacity—and thus creativity—collaborative work and care. The third challenge is the speed of change; in just a few decades we could find ourselves in a very different situation. There will not be much time for trial and error, or for experimenting with possible responses to degrowth/collapse; so, it is a priority to educate in a critical spirit, in increasing our evaluative capacity, and in feminist eco-literacy [44] based on scientific knowledge rather than on mythical thinking [52].

4.4. The Training of Future Teachers

Although recognised in Spain and even as a priority objective of current educational legislation, many educational administrations, and numerous institutions and organisations [32], the truth is that it is not reflected in the curricula of faculties of education in a systematic and planned way [49].

Therefore, the results of those research studies that reveal the existence of uncritical and conformist attitudes among trainee teachers are not surprising. However, it is also pointed out in some cases that a profile of a future transforming teacher appears in line with a degrowth pedagogy focused on critical and emancipatory action [29,46]. Another outstanding aspect is the average academic scientific knowledge of trainee teachers in contrasts with a high level of pro-environmental attitudes [40].

It is also noted that trainee teachers prefer individual eco-sustainable behaviours (using the bicycle as a means of transport) to collective ones (actively participating in campaigns), those of lesser involvement (turning off the heating) to those of greater involvement (choosing alternative means of transport to flying). In addition, a low predisposition to exert political pressure for the resolution of socio-environmental problems and change towards degrowth was found [36,40].

4.5. The Orientation of Education Policies

An example of the introduction of sustainability in the field of education is the current Spanish education law; that is, the Organic Law 3/2020, of 29 December, which amends the Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May, on Education (LOMLOE). This regulation refers to sustainability from the preamble, recognising sustainable development as one of the five key focuses of the law. In Article 1 on the principles guiding the law, it establishes education for ecological transition with social justice criteria as a contribution to environmental, social and economic sustainability. Its Title IV establishes that the education system cannot be oblivious to the challenges posed by the CC of the planet, and that educational centres must become a place of custody and care for our environment [34,40,59].

In the general principles, Article 110 is reformulated to include sustainability and relations with the environment, highlighting the need for coordination between administrations to promote and guarantee the culture of environmental sustainability, social cooperation to protect biodiversity, etc.

Furthermore, it establishes that Education for Sustainable Development, global citizenship and the 2030 Agenda will be included in the training processes and access to the teaching profession. This obliges teachers to have received specific training in the contents of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the 2030 Agenda by 2025. In general, the studies reviewed conclude that the LOMLOE represents an advance with respect to previous laws, although it lacks the inclusion of an eco-social competence and a critical view at some of the approaches of the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda [23,33,34,40,45].

5. Conclusions

There are various approaches to intervene in education in the face of the CC problem: education for sustainable development [60], environmental education [61], ecopedagogy [58,62], etc. However, in this research we have focused on the pedagogy of degrowth, as this represents an amendment to the entire capitalist system based on infinite growth on a finite planet [63,64].

Regarding the first question posed by this research, the studies reviewed coincide in pointing out that it has indeed become a relevant issue in terms of the concern expressed by both the educational community and the educational administrations and legislation in force. Still, this contrasts with the scarce and relative lack of effective implementation of practices that mainstream all educational action; from the curriculum of all subjects to the organisation of schools in all senses. In this sense, there is still a long way to go for degrowth to become a central axis in the educational field [65,66].

Accordingly, a substantial change would entail a thorough revision of the contents reflected in the textbooks and curricular materials of all subjects. These should incorporate knowledge, principles and values in a systematic way about the whole problem; its causes, impact and consequences, questioning the model of unlimited growth and consumption that capitalism entails.

Concerning the epistemological conceptualisation from the perspective of education, there is a progressive awareness of the importance of the climate crisis among all sectors of the educational community. Likewise, its causes are progressively being associated not only to individual conduct or behaviour linked to selfishness and consumerism, but also to structural causes related to the capitalist model. There is also a representation in the educational content and process that is more focused on the catastrophic consequences of the problem than on structural solutions. This can lead to a difficulty in visualizing possible alternatives. Moreover, catastrophe or collapse is seen as temporarily distant, which reduces the urgency of intervention in education. It would then be necessary to focus on conceptualising and developing the alternative of degrowth as a global, planned and hopeful solution to the current situation. Its seriousness, on the other hand, must be confirmed with contrasted and scientific information allowing society to become truly and accurately aware of its possible irreversibility if measures are not urgently planned [67,68].

Therefore, we believe that an epistemological shift is needed that goes beyond unidisciplinarity, reflecting the need for knowledge aimed at changing the foundations and pillars of the current development model. For this, it is necessary to incorporate critical theories to understand scientific thought and its relationship with racial, patriarchal and colonial power structures. Ecology and degrowth play a relevant role as key fields in providing solutions to the depletion of natural ecosystems, the overflow of planetary cycles, and their relationship with the capitalist reproduction model [34].

Educational intervention strategies to initiate and involve present and future generations in degrowth can be varied and complementary, as has been seen in this review. These include transmitting knowledge and contrasted information [69] to initiating participatory research-action processes, and implementing measures consistent with the proposed change in the educational centre itself and in its environment. At the same time, there is a need to expose the model that sustains the situation, and to get involved with social movements and activists against CC and the system that maintains it [1,4].

The limitations of this SLR are the scant literature currently available; mostly on specific experiences or practices that reflect the teaching and didactic lines of action of this pedagogy of degrowth in classrooms and educational centres. Therefore, literature not specifically referring to the concept of degrowth but addressing aspects substantially related to this approach has been included in this review.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16219210/s1, Table S1: The PRISMA 2020 checklist. References [70,71] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cao, F.; Jian, Y. The Role of integrating AI and VR in fostering environmental awareness and enhancing activism among college students. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fullerton, J. Regenerative Capitalism; Capital Institute: Thiruvananthapuram, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, L.V. Regenerative—The new sustainable? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.A.; Statham, A.; Gilles, E.E.; Roberts, M.R.; Turner, W. From awareness to activism: Understanding commitment to social justice in higher education. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice 2024, 19, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, T. The new ‘passive revolution’ of the green economy and growth discourse: Maintaining the ‘sustainable development’of neoliberal capitalism. New Political Econ. 2015, 20, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; King, R.B. What predicts perceived economic inequality? The roles of actual inequality, system justification, and fairness considerations. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 61, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, Á.; Rodríguez-Bailón, R.; Willis, G.B. The economic inequality as normative information model (EINIM). Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 34, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alister, C.; Cuadra, X.; Julián-Vejar, D.; Pantel, B.; Ponce, C. (Eds.) Cuestionamientos al Modelo Extractivista Neoliberal desde el Sur: Capitalismo, Territorios y Resistencias; Ariadna Ediciones: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- López, G. Good morning. We’re covering extreme weather, cooling inflation and Emmy nominations. The New York Times. 13 July 2023. Available online: https://messaging-custom-newsletters.nytimes.com/dynamic/render?abVariantId=0&productCode=NN&uri=nyt%3A%2F%2Fnewsletter%2Fcd58fe9b-1217-592b-b4f2-8e9252a23c50 (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Mínguez-Vallejos, R.; Pedreño-Plana, M. Educación para el desarrollo sostenible: Una propuesta alternativa. In Transformar la Educación para Cambiar el Mundo; González, E., Mínguez, R., Eds.; Consejería de Educación y Cultura de la Región de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2021; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Shchegel, O. Pursuit of Happiness: Maryna Hrymych and Unhappy Human in Consumption Society. Korean J. Ukr. Stud. 2020, 1, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossel, H. Earth at a Crossroads: Paths to a Sustainable Future; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. Building a Sustainable Society; Worldwatch Inst: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein, E. The economic roots of environmental decline: Property rights or path dependence? J. Econ. Issues 1995, 29, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Luna, L. El desafío ambiental: Enseñanzas a partir de la COVID-19. Medisan 2020, 24, 728–743. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council, Policy, Global Affairs; Policy Division; Board on Sustainable Development. Our Common Journey: A Transition Toward Sustainability; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J. Los récords de calor que está batiendo esta década: Los días de más de 40 grados ya no son una excepción. El País. 11 July 2023. Available online: https://elpais.com/clima-y-medio-ambiente/2023-07-11/datos-los-records-de-calor-que-esta-batiendo-esta-decada-los-dias-de-mas-de-40-grados-ya-no-son-una-excepcion.html (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- González-Gaudiano, E.J.; Meira-Cartea, P.A. Educación para el cambio climático: ¿educar sobre el clima o para el cambio? Perfiles Educ. 2020, 42, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Pérez, J.; Meira-Cartea, P.A.; González Gaudiano, E.J. Educación y comunicación para el cambio climático. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. (RMIE) 2020, 25, 819–842. [Google Scholar]

- Bento, A.M.; Miller, N.; Mookerjee, M.; Severnini, E. A unifying approach to measuring climate change impacts and adaptation. In NBER Working Paper No. 27247; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27247/w27247.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Meira, P.A. Problemas ambientales globales y Educación Ambiental: Una aproximación desde las representaciones sociales del cambio climático. Integr. Educ. 2013, 6, 29–64. [Google Scholar]

- González Gaudiano, E.J. La educación frente a la emergencia sanitaria y del cambio climático. Semejanzas de familia. Perfiles Educ. 2020, 11, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Fernández, O. Problemas socioambientales y educación ambiental. El cambio climático desde la perspectiva de los futuros maestros de educación primaria. Pensam. Educ. Rev. Investig. Educ. Latinoam. 2020, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Revisiones y Mapeos Sistemáticos de Literatura; Grupo GRIAL: Salamanca, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev. Esp. Cariol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, J.; Cartes-Velásquez, R. Pautas de Chequeo, parte II: QUOROM y PRISMA. Rev. Chil. Cirugía 2015, 67, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecologistas en Acción. Estudio del Currículum Oculto Antiecológico de los Libros de Texto; Ecologistas en Acción: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Gutiérrez, E.-J.; Palomo-Cermeño, E. Degrowth and Higher Education: The Training of Future Teachers. Sustain. Clim. Chang. 2023, 16, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Robles, A.; Trujillo-Vargas, J.J.; Perlado, I. Investigative-training contributions on degrowth for university teacher training. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2024, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morote, A.F. ¿De dónde está recibiendo la información sobre el cambio climático el alumnado? Una aproximación desde las Ciencias Sociales. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2022, 34, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Díaz, M.; Moreno-Fernández, O.; Rivero-García, A. El cambio climático en los libros de texto de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. (RMIE) 2020, 20, 957–985. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, G.; Bonilla, N.; Prosser, C.; Romo-Medina, I. Expertos por experiencia en la educación para el cambio climático: Emociones, acciones y estrategias desde la perspectiva de participantes de tres programas escolares chilenos. Rev. Estud. Exp. Educ. (REXE) 2022, 21, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vinuesa, A.; Bello-Benavides, L.O.; Iglesias da Cunha, M.L. Desigualdades de género en la educación para el cambio climático. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. (RMIE) 2020, 25, 1013–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, Y.; Rendueles, C.; Muiño, E.S.; Valladares, F.; Valero, A. La enseñanza de la crisis ecológica en la educación superior: Una propuesta. Dossieres EsF 2022, 47, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Benavides, L.O.; Cruz-Sánchez, G.E. Profesorado universitario ante el cambio climático. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. (RMIE) 2020, 25, 1069–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pacheco, F.L.; Mejía-Rodríguez, D.L.; Sánchez-Buitrago, J.O. Conocimientos y percepciones sobre el cambio climático en estudiantes universitarios. Divers. Perspect. Psicol. 2022, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto, R. El cambio climático en las representaciones sociales de los estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Electrón. Investig. Educ. 2018, 20, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, E.; Castillo, C.; Vallejos, M. Representaciones sociales sobre desarrollo sostenible y cambio climático en estudiantes universitarios. Perspect. Comun. 2013, 6, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera-Hernández, L.; Murillo-Parra, L.D.; Ocaña-Zúñiga, J.; Cabrera-Méndez, M.; Echeverría-Castro, S.B.; Sotelo-Castillo, M.A. Causas, Consecuencias y qué Hacer Frente al Cambio Climático. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. (RMIE) 2020, 25, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Fernández, A.; Rodríguez-Marín, F.; Solís Ramírez, E.; Rivero García, A. Alfabetización ambiental del profesorado de Educación Infantil y Primaria en formación inicial. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2022, 36, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilanes-Capelo, R.M.; Tipán-Barros, B.G. La Educación Ambiental como estrategia para enfrentar el cambio climático. Alteridad Rev. Educ. 2021, 16, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinet, M.; Hosta, J.; Llerena, G.; Massip, M. Educar en el Decrecimiento: Una perspectiva necesaria en agroecología escolar. In Educación para el Bien Común: Hacia una Práctica Crítica, Inclusiva y Comprometida Socialmente; Díez-Gutiérrez, E.J., Rodríguez-Fernández, J.R., Eds.; Octaedro: Quito, Ecuador, 2020; pp. 465–479. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Labrada, Y.R.; Pérez-Benítez, M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, G.; Domínguez- Hopkins, R. La educación ambiental ante el cambio climático en la formación del profesional universitario: Experiencias desde la Universidad de Oriente. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2021, 13, 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Caramés, R.; Mulet, B. Extrañamiento ecofeminista a la cibercultura como paradigma para una sociología de la educación del decrecimiento. Teknokultura 2018, 15, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.E.; Rodríguez-Marín, F.R.; Fernández-Arroyo, J.; Gutiérrez, M.P. La educación científica ante el reto del decrecimiento. Alambique Didáctica Cienc. Exp. 2019, 95, 47–52. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6770356 (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Pérez-Rodríguez, U.; Varela-Losada, M.; Lorenzo-Rial, M.A.; Vega-Marcote, P. Tendencias actitudinales del profesorado en formación hacia una educación ambiental transformadora. Rev. Psicodidáct. 2017, 22, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gaudiano, E.J.; Maldonado-González, A.L. ¿Qué piensan, dicen y hacen los jóvenes universitarios sobre el cambio climático? Un estudio de representaciones sociales. Educ. Em Rev. Espec. 2014, 3, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto-Flores, R. Las representaciones sociales del cambio climático en estudiantes de educación secundaria. Rev. Estud. Exp. Educ. 2015, 14, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Meira, P.A.; Arto, M. Representaciones del cambio climático en estudiantes universitarios en España: Aportes para la educación y la comunicación. Educ. Rev. Espec. 2014, 3, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto, R. Mirada compartida del cambio climático en los estudiantes de bachillerato. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. (RMIE) 2020, 25, 987–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Cadena, M.E.; Fernández-Crispín, A.; Cruz-Vargas, A.; Bueno-Ruiz, P. De la representación social del cambio climático a la acción. El caso de estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. (RMIE) 2020, 25, 1043–1068. [Google Scholar]

- García-Díaz, J.E.; Fernández-Arroyo, J.; Rodríguez-Marín, F.; Puig-Gutiérrez, M. Más allá de la sostenibilidad: Por una Educación Ambiental que incremente la resiliencia de la población ante el decrecimiento. Rev. Educ. Ambient. Sostenibilidad 2019, 1, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, N.; Páramo, P. Educación para la mitigación y adaptación al cambio climático en América Latina. Educ. Educ. 2020, 23, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Marín, F.; Fernández-Arroyo, J.; Puig-Gutíerrez, M.; García-Díaz, J.E. Los huertos escolares ecológicos, un camino decrecentista hacia un mundo más justo. Enseñanza Cienc. Extra 2017, 32, 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Boronat-Gil, R.; Gómez-Tena, M.; López-Pérez, J.P. Diseño experimental de un sumidero de CO2 y sus implicaciones en el cambio climático. Una experiencia de trabajo con alumnos en el laboratorio de Educación Secundaria. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Cienc. 2018, 15, 1202–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robredo, B.; Ladrera, R. ¿Preparados para la acción climática al finalizar la Educación Primaria? Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. (RMIE) 2020, 25, 933–955. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, J.P.; Bhaskar, A.; Pandit, M.K. Biology, distribution and ecology of Didymosphenia geminata (Lyngbye) Schmidt an abundant diatom from the Indian Himalayan rivers. Aquat. Ecol. 2008, 42, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallart i Navarra, J.; Solaz Almena, C. Educación, Ciudadanía y Convivencia. Diversidad y Sentido Social de la Educación: Comunicaciones del XIV Congreso Nacional y III Iberoamericano de Pedagogía. 2008. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=351659 (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Flores, R.C. La formación de maestros en educación ambiental. Una experiencia con base a la elaboración de situaciones problema y alternativas de solución. Educ. Rev. 2022, 38, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H.; Bedford, T. From pseudo to genuine sustainability education: Ecopedagogy and degrowth in business studies courses. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2024, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, J.M.; Esquivel-Martín, T.; Guevara-Herrero, I. Educación Ambiental de Maestros para Maestros; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Peñalver, S.M.; Porcel-Rodríguez, L.; Ruiz-Peñalver, A.I. La ecopedagogía en cuestión: Una revisión bibliográfica. Contextos Educ. Rev. Educ. 2021, 28, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Gutiérrez, E.J. Educar en y para el Decrecimiento. El País. 23 August 2024. Available online: https://elpais.com/educacion/2024-08-23/educar-en-y-para-el-decrecimiento.html (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Kaufmann, N.; Sanders, C.; Wortmann, J. Building new foundations: The future of education from a degrowth perspective. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriluță, N.; Grecu, S.P.; Chiriac, H.C. Sustainability and employability in the time of COVID-19. Youth, education and entrepreneurship in EU countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.J. Imagining education beyond growth: A post-qualitative inquiry into the educational consequences of post-growth economic thought. Curriculum Perspectives 2024, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saborit, I.C.; Bordera, J. Una salida justa al laberinto de la transición energética. Cantárida 2023, 483, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel, A. El futuro ya no es lo que era: Crecimiento y sostenibilidad. Telos Cuad. Comun. Innovación 2020, 113, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Canaza-Choque, F.A. De la educación ambiental al desarrollo sostenible: Desafíos y tensiones en los tiempos del cambio climático. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2019, 165, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Gutiérrez, E.-J. Formar al profesorado en decrecimiento como intervención socioeducativa emancipadora. In La Educación Como Elemento de Transformación Social: Libro de Actas; Asociación Universitaria de Formación del Profesorado (AUFOP): Calle San Juan Bosco, Spain, 2012; p. 1195. [Google Scholar]

- Díez Gutiérrez, E.-J.; Palomo Cermeño, E. La formación universitaria del futuro profesorado: La necesidad de educar en el modelo del decrecimiento. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2022, 36, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).