Abstract

The collection of the ancestral fruit cauchao (Amomyrtus luma) is part of the routines of women gatherers from the extreme south (44° South Latitude) in Chile. The traditional food knowledge of cauchao has not been documented, and there is no data on the nutritional composition. Women’s experiences collecting cauchao can help understand the relationship between traditional food, herbal medicine, and local gatherers’ communities. Thus, this research explores the traditional knowledge of food and the nutritional composition of cauchao. Mixed methods research was performed. A case study included in-depth interviews with 12 women gatherers and thematic analysis. The composition of macronutrients in cauchao was obtained by proximate chemical analyses and dietary fiber using the enzymatic-gravimetric method. Results showed that gathering for these women was more than just extracting natural resources; it was associated with family, food security, participation in different stages of the food system, and practices that could contribute towards sustainable food systems. Furthermore, cauchao fruit showed a high dietary fiber content, and women gatherers did not connect cauchao with dietary fiber. Since access to knowledge by small-scale food producers, especially women, is part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG#2.3), the approach of this research may help guide knowledge transfer among women gatherers.

1. Introduction

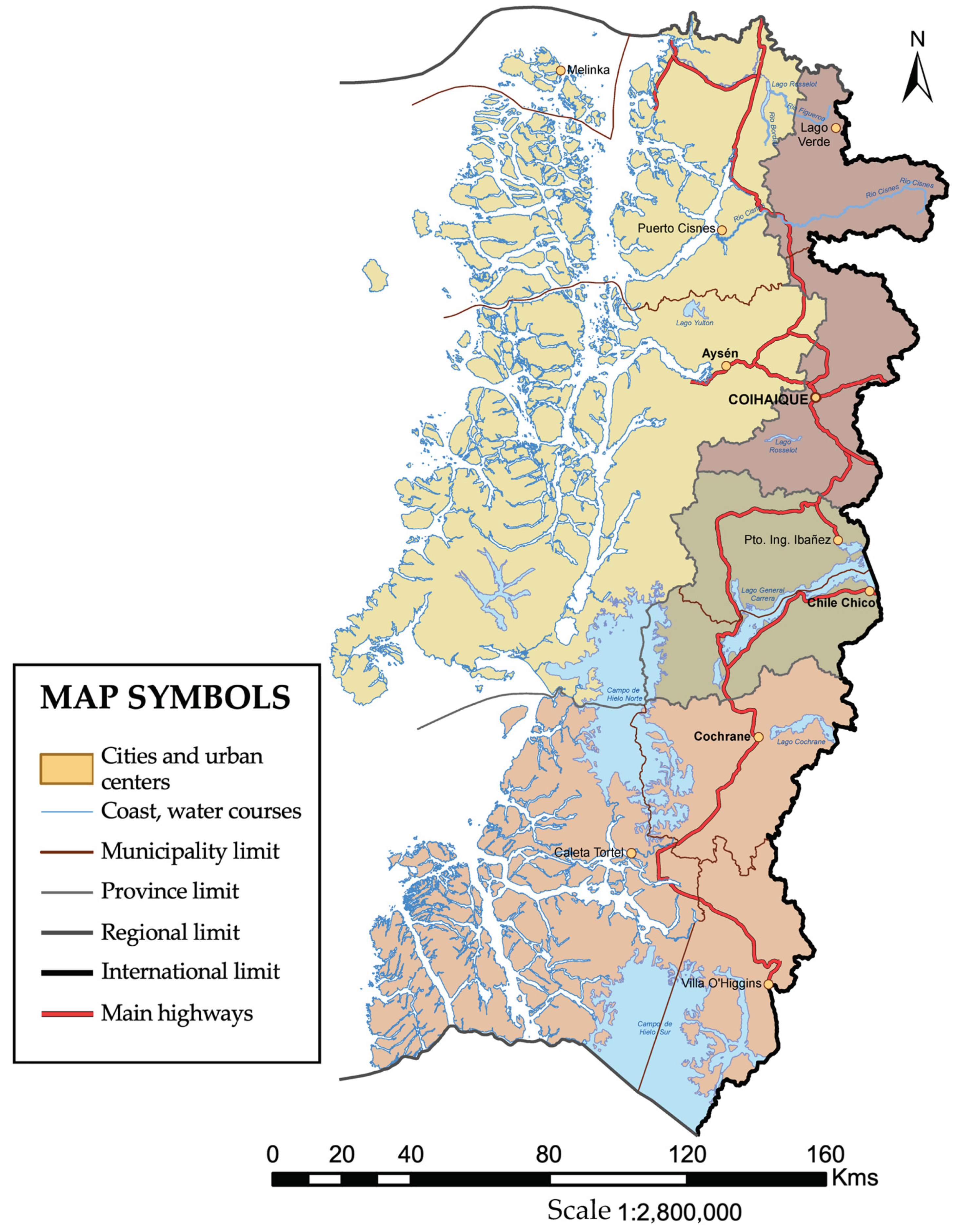

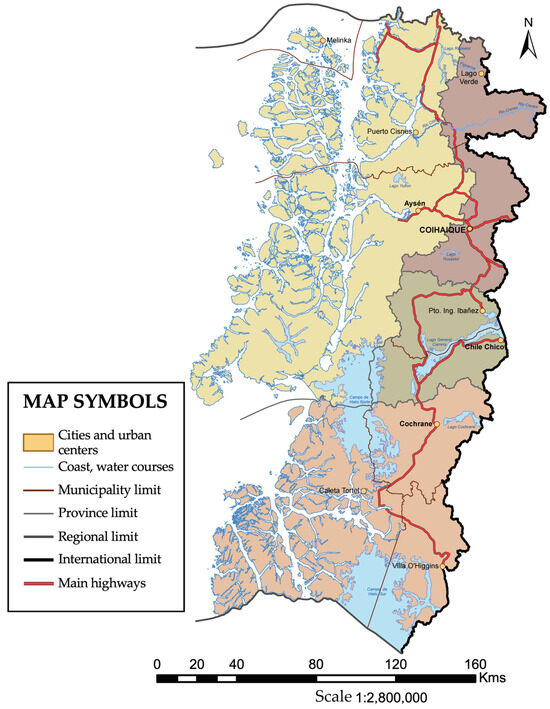

The high degree of endemism of the Chilean flora represents an essential genetic resource for food [1], where the collection of ancestral fruits is deeply rooted in the food habits of indigenous peoples, rural communities, and native forests [2]. In particular, the collection of cauchao (Amomyrtus luma Molina, botanical family: Myrtaceae) fruit (Figure 1) is part of the routines of women gatherers from the extreme south (44° South Latitude) [3].

Figure 1.

Cauchao fruit collected in extreme south forests (Puerto Cisnes, Aysen, Chile). Author: Daniela Gómez. Date: January 2021.

A review of the work of naturalists, anthropologists, and books on ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology available at the National Digital Library (www.memoriachilena.cl, accessed on 20 December 2021) did not report the traditional food knowledge of cauchao fruit by Indigenous peoples and rural populations in the extreme south forests [4,5,6,7]. Furthermore, the Chilean Ministry of Health does not recognize cauchao as part of the Traditional Herbal Medicines (THM) [8]. Indeed, the TMH lacks an exhaustive review of the contribution of native plants from Chile to traditional herbal medicine since this knowledge has been scarcely documented in books and scientific articles [2]. Therefore, reports on anthropological and ethnobotanical field studies are necessary to understand the relationship between traditional food, herbal medicine, and local gatherer communities [9]. At the same time, scientific research needs to generate evidence on the traditional food and medicinal use of new native species that can enrich Chile’s traditional herbal medicines.

The lack of ethnographic documents and scientific articles reporting the traditional food knowledge and the nutritional composition of cauchao fruit suggests a low appreciation of cauchao as a non-wood forest product for food purposes. This problem could be due to the low visibility of the collection trade as part of women’s cultural heritage in extreme south forests in Chile. Furthermore, women might lack the know-how for food entrepreneurship within the food systems. This research highlighted that:

- There is little documentation of the traditional food knowledge of gatherers from the extreme south forests in Chile.

- There is no data on the nutritional content of cauchao fruit.

- Producing scientific knowledge is necessary to guide knowledge transfer with women gatherers.

Forests have a recognized role in food systems [10,11]. Using the concept proposed by Fassio for food systems [12], this research defined forest food systems as a series of interconnected actions that entail food production, processing, consumption, and waste generation. The primary research question was: What are women’s experiences collecting cauchao in extreme south forest food systems? This research question pointed beyond the economic incentive that may exist for selling the cauchao collected. The significance of the study was to demonstrate how a group of women gatherers and traditional food knowledge were involved in the different stages of the food systems and the food security and in recognizing the nutritional chemical composition of the cauchao fruit.

Thus, this research aimed to explore the traditional knowledge of food and the nutritional composition of cauchao to gain insights into women gatherers’ food systems and livelihoods. Mixed methods research was conducted. Qualitative data was used to build a narrative from the voices of the women gatherers, recorded in interviews. Quantitative data was obtained from chemical analyses of fruit composition. To the best of our knowledge, mixed methods research is novel in investigating the traditional use of cauchao fruit and its nutritional composition. The innovation of this research is a proposal of a circular model of a sustainable food system based on the current situation of a group of women gatherers from the extreme south forests in Chile. The transfer of knowledge about this proposal and the composition of the cauchao fruit may add value to the development of new products and significantly impact the livelihoods of women gatherers and their families.

Literature Review

Biodiversity hotspots are geographical areas worldwide that contain a large number of endemic species; Chile is regarded as a biodiversity hotspot [1]. Of the 5105 higher plants described in Chile, 45.8% are endemic [13]. FAO [14] defines biodiversity for food and agriculture as “a component of biodiversity that contributes to agricultural and food production”, including forest species and other collected wild species, among others. Biodiversity is thus an essential source of nutrition and subsistence for many people. However, the state of biodiversity and its threats are worrying. Climate change, human behavior, and other drivers have affected vital ecosystems such as forests, decreasing the species’ population (i.e., many species become vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered) [15]. In other words, climate change and anthropogenic intervention can result in a loss of genetic diversity.

Since the XVIII century, several naturalists and anthropologists have denoted the use of the biodiversity of Chile and the contribution of indigenous peoples and rural communities to sustaining traditional plant knowledge [4,5,6,7,16]. Most records correspond to field observation work or conversations with representatives of indigenous and rural communities in central and south-central Chile. Indeed, previous research denoted a gap in knowledge of the traditional use of native fruits throughout Chile [17]. The traditional knowledge of the Mapuche people and the rural population of central and south-central Chile has been more widely compiled and disseminated than the knowledge of the indigenous peoples and the rural population of the extreme south of Chile [17]. Nevertheless, the role of women is manifest in indigenous peoples and the rural population, where women from the extreme south of Chile have historically collected some edible roots, wild fruits and mushrooms, and seeds to survive in extremely harsh conditions [16]. On the other hand, man has been involved with hunting and fishing [7].

Cauchao, luma, or reloncavi is considered one of the 10 species of the genus Myrtus found in Chile by flora naturalists such as Molina [5] and Gay [4]. The Chilean Ministry of the Environment [18] considers cauchao a native species distributed in Chile and Argentina in South America [19]. The distribution of the luma tree in Chile covers the Maule (34° South Latitude) to Aysen (44° South Latitude) region, from 0–800 m above sea level. In the extreme south of Chile, Luma is an evergreen tree that grows naturally as part of the deciduous Nothofagus and evergreen forests [19]. Currently, there are no advances in luma tree domestication and cultivation; cauchao is collected from wild populations of luma trees. Díaz-Forestier et al. [20] compiled the uses of the 19 native Myrtaceae species of Chile, recognizing medicinal, edible, ornamental, dye, magic-ritual, wood, cosmetic, and beekeeping. The uses of cauchao are limited to medicinal, edible, and wood.

During the last decade, interest in studying wild fruits has increased due to their attractive sensory properties, and there is a global trend in finding new fruits with potential health benefits. Furthermore, the characterization of biodiversity and wild foods is a strategic priority area proposed by FAO for the sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity for food and agriculture [15]. In particular, fresh fruits are a source of dietary fiber, vitamin C, potassium, magnesium, and bioactive compounds [21]. Dietary patterns high in fruits and vegetables have consistently been identified as protective against cardiovascular disease and premature mortality [22,23,24,25].

Some authors have reported the nutritional composition of other fruits of the Myrtaceae botanical family, such as camu camu (Myrciaria dubia (Kunth) McVaugh), guava (Psidium guajava L.), and murta (Ugni molinae Turcz) [26,27]. In this sense, cauchao could have a nutritional content similar to fruits from the same botanical family. Therefore, research on the cauchao fruit may complement the study of native Chilean fruits such as murta, maqui (Aristotelia chilensis [Mol] Stuntz), and calafate (Berberis buxifolia Lam.), recognized for their traditional use and their nutritional composition [17,28,29].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Research Area

Aysen (44° South Latitude) is the third largest region in Chile, where 41% (4,431,845 ha) of its surface corresponds to a forest, mainly native (99.7%) [30]. On the contrary, Aysen is the region with the smallest population (i.e., 103,158 inhabitants, 0.6% of the total population in Chile), where 48% are women [31]. From a gender perspective, around half of the micro and small enterprises in Aysen have a woman as the leading owner [32]. Nevertheless, the average income for women was $403,000 (US$ 411), while the average income for men in Aysen was around $500,000 (US$ 510) [33]. Income thus denotes a gap of 19% between women and men.

The climate of Aysen is cold oceanic and strongly influenced by the polar front. The mean annual rainfall fluctuates between 3000 and 4000 mm. Temperature is low, with a yearly mean of 8 to 9 °C, where the maximum air temperatures occur in January. The regional area of native forest by species involves evergreen forests (47.9%), Nothofagus forests (29.4%), cypress de las Guaitecas forests (Pilgerodendron uviferum, Cupressaceae, 11.3%), and coigüe de Magallanes forests (Nothofagus betuloides, Nothofagaceae, 10.8%) [30].

This research selected the town of Cisnes in the Aysen region (Figure 2) as the research area because its municipality has a rural office that supports facilities for local gathering communities, providing a link between the community and the study researchers. Cisnes has a population of 6517 inhabitants [31], an extension of 16,093 km2 with irregular geography (i.e., a large number of watercourses, archipelagos, islands, and mountains) [30]. The seven localities (Puerto Raúl Marín Balmaceda, La Junta, Puyuhuapi, Puerto Cisnes, Puerto Gaviota, Puerto Gala, and Melimoyu) of Cisnes are isolated [34]. Isolation suggests a challenge to women gatherers to work together as communities.

Figure 2.

Research area in the Aysen region and Puerto Cisnes in Chile. Source: ODEPA [30].

2.2. Selection and Description of Participants

Preliminary, the rural office of Cisnes provided information about local gathering communities that collected non-wood forest products for food. The rural office identified six gatherer communities, with 74 women and 26 men. These local communities collected rosa mosqueta (Rosa eglanteria L.), morchela (Morchella esculenta), nalca (Gunnera tinctoria (Molina) Mirb.), maqui, calafate, and cauchao.

The rural office of the Municipality of Cisnes invited women gatherers from Cisnes to participate in the research. All participants had access to the Internet. Previously, the office’s community outreach staff provided training on using the Zoom platform. Then, a remote meeting (via Zoom, version 5.8.3) was held to explain the research procedure to all the gatherers interested in participating in the research. Fifteen female gatherers participated in the meeting; 12 agreed to participate in the research. Each female gatherer who agreed to participate accepted an informed consent form.

2.3. Interviews

A case study [35] was conducted using a constructivist research paradigm. This research used convenience sampling, using a “snowball” strategy; each participant was asked about potential new participants [36]. Thus, this research performed in-depth interviews with the 12 women gatherers to investigate the traditional uses of cauchao using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix A). These interviews were conducted remotely (via Zoom) and lasted approximately one hour. Women gatherers were generally connected from their households during October 2020. This month did not coincide with gathering activities.

All the interviews were transcribed verbatim. For the analysis, the interviews were anonymized. Initial information saturation criteria were used [35], which were achieved with the inclusion of 12 participants. A thematic content analysis was aimed at “identifying, organizing, analyzing and reporting patterns or themes from a careful reading and re-reading of the information collected” [37]. These thematic patterns were consistent with the interview guide, which in turn was consistent with the specific objectives and primary research question. Thematic patterns allowed the creation of codes and categories that emerged from the participants for each of the guiding questions that are the focus of the analysis of this study. This qualitative analysis strategy was the most appropriate for this research since it allowed us to focus on the phenomenon of the study, which was consistent with the case study design. NVivo 11 software was used for this analysis and facilitated triangulation in the findings among research team members, which responds to the rigor of the information analysis.

2.4. Chemical Analysis

After the interviews, the 12 women gatherers were contacted and asked if they could provide fruit for chemical analysis. Therefore, fruit sampling was opportunistic, according to the feasibility of the gatherers in providing fruit samples. Five women gatherers provided cauchao fruit samples (500 g). Fruits were manually collected in Cisnes in February 2021, refrigerated (4 °C) in plastic bags, delivered to the rural office staff, and transported in an insulated shipping container to Santiago through an overnight courier service.

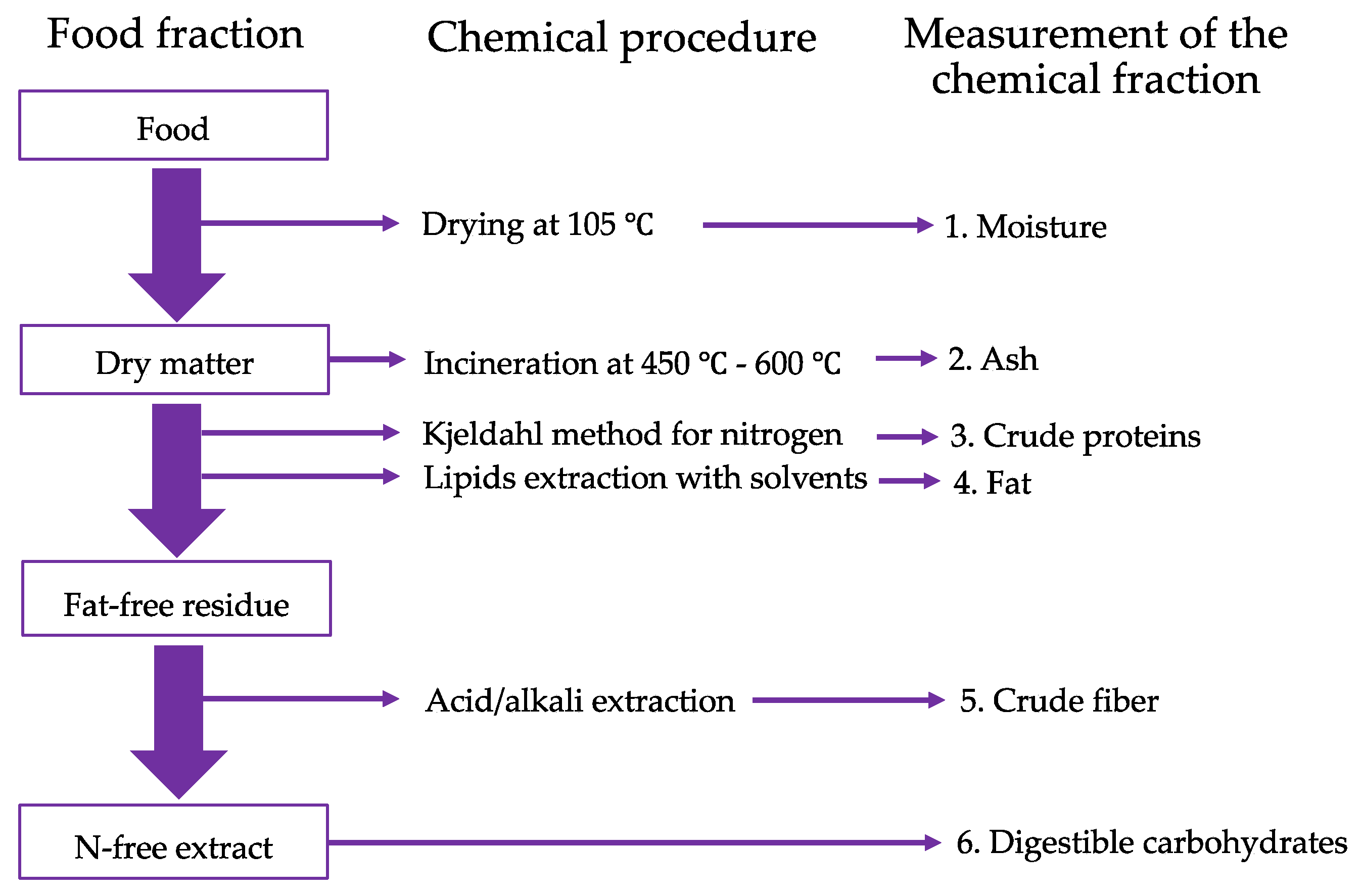

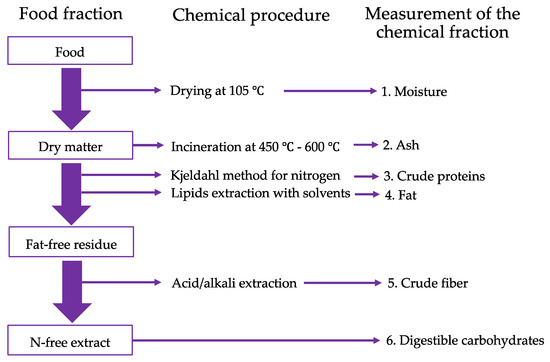

The determination of moisture, ash, total proteins, carbohydrates, and fat was carried out from the proximate chemical analysis (Figure 3) using AOAC methods [38]. The analysis of dietary fiber (i.e., total, soluble, and insoluble) was performed using the enzymatic-gravimetric method, considered a reference method [38]. Total sugars (glucose, fructose, and sucrose) were quantified using HPLC-IR [26]. The results of the nutritional content were expressed per 100 g of fresh weight.

Figure 3.

Flow chart for proximate chemical analysis. Source: Greenfield and Southgate [39].

2.5. Duration of Thorough Field Research

Due to the sanitary restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, this research conducted remote meetings and interviews during October 2020. Fruit sample collection was performed in February 2021.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Participants

Table 1 summarizes the description of the women gatherers (n = 12). The mean age was 46, ranging between 30 and 59 years old. In Chile, school education comprises primary (8 years) and secondary (4 years); technical education comprises 2 years. The educational level of the women gatherers was predominantly secondary school education (i.e., 12 years of school education), with various occupations in addition to gatherers. In general, the women gatherers lived as a family with a couple; they were mothers of a mean of 3 sons and daughters, and part of them lived in households.

Table 1.

Description of participants.

Women gatherers collected with their families, and two had a micro-enterprise. Most resided in Puerto Cisnes. Regarding the identification with some ethnic groups, half of them identified with the Mapuche ethnic group, and one declared that they “value everything ancestral”. The women gatherers reported a mean household income of $503,000 (US$ 513), with a range between $80,000 (US$ 82) and $2,000,000 (US$ 2041). The mean income for women gatherers was higher than those reported for women of the Aysen region [33]. On the other hand, the mean income of women gatherers was similar to men’s income in the Aysen region.

3.2. Thematic Patterns from the Collected Data

Qualitative data was used to construct a table with themes, sub-themes, findings, and representative quotes (Appendix B) of women gatherers (WG). This research identified cultural, family, and community components, post-collection handling, entrepreneurship, other non-wood products, and medicinal properties as themes and stages of the food supply chain (i.e., collection, processing, by-products, and distribution) and the traditional use of cauchao fruit, leaf, and wood as sub-themes.

Cultural, family, and community components describe the relationship between gathering, family, and community. Collection details techniques for gathering cauchao fruit. For example, “Cauchao is also a very delicate product, and it is complicated to collect it” and “It has its technique to collect it, and we collect what we need” (WG02) were representative quotes associated with techniques of fruit collection. Furthermore, “Everyone collected what we need. In those years, of course, we did not shake the trees. Because it was for our consumption more than anything” (WG01) was a quote also associated with the collection, where we observed a second fruit collection technique. Post-collection handling, processing, and distribution detail the participation of women gatherers in different stages of the food supply chain.

The by-products sub-theme revealed that women gatherers also use leaves and wood of the luma tree. “People say ‘there is a lot, a lot,’… We have to collect what we need” (WG08). This representative quote denoted a careful use of cauchao fruit and by-products of the luma tree. This research defined entrepreneurship as the capacity of women gatherers to develop and commercialize products. “Our way of collecting is always with respect; it will always be with respect” and “Moreover, we collect what we need. We already have our places” (WG11) were quotes associated with entrepreneurship that reflect the consciousness of a woman gatherer in the commercialization of cauchao. Therefore, “We only collect what we need” was a phrase from the voices of four women gatherers that this research used in the title of this article.

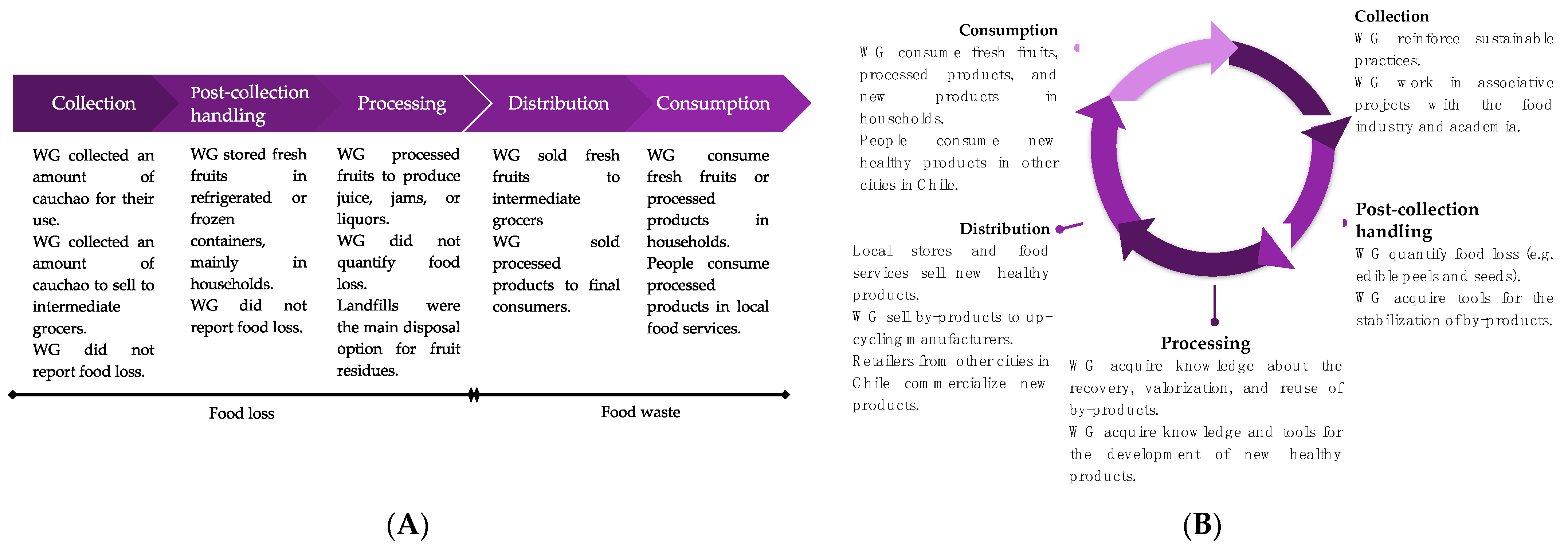

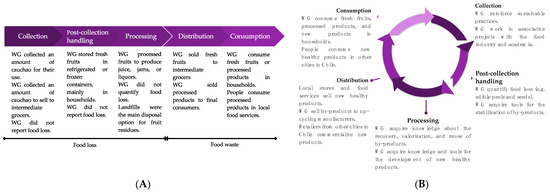

Qualitative data was also used to build a model of the current food supply chain associated with cauchao, women gatherers’ participation, and food loss production (Figure 4A). This research also proposed a circular model of a sustainable food system where women gatherers participate and interact with stakeholders of food systems and academia (Figure 4B). These models described the levels of the food supply chain characterized by Gooch et al. [40] and the food system proposed by Fassio et al. [12].

Figure 4.

Participation of women gatherers in food systems. Current food supply chain and production of food loss (A) and sustainable food systems for women gatherers (B).

3.3. Nutritional Content of Cauchao Fruit

Macronutrients (i.e., available carbohydrates, fat, and proteins), total sugar content, and dietary fiber content of cauchao fruit are detailed in Table 2. The moisture content (~80 g/100 g) was predominant in the composition of the cauchao fruit. Carbohydrates (5.1 g/100 g) were the macronutrient most abundant in cauchao. Regarding the type of dietary fiber, soluble fiber (9.9 g/100 g) predominates in the composition of total dietary fiber (10.9 g/100 g) of the cauchao fruit.

Table 2.

Nutritional content of cauchao fruit (100 g).

4. Discussion

This research is intended to use cauchao fruit to construct a women’s narrative on food systems in extreme south forests. Qualitative and quantitative data were obtained. This research conducted in-depth interviews with 12 female gatherers from the Aysen region to investigate the traditional food knowledge of cauchao as an example of ancestral fruit. Qualitative data allowed us to construct a narrative from the voices of the women gatherers, recorded in interviews. The results of the content of macronutrients, total sugars, and dietary fiber of the cauchao fruit provided basic information on the composition of the cauchao fruit that was not previously reported. “Only collect what we need” was a quote representing the main findings of this research that responded to the research question: What are women’s experiences collecting cauchao in extreme south forest food systems? In the following subsections, this research discusses the principal themes obtained in the thematic analysis and proposes research topics that may help empower women gatherers and their traditions.

4.1. Only Collect What We Need to Preserve

This research showed that women gatherers use biodiversity for food and medicinal use (Table A1; fruit and leaf sub-themes and medicinal properties theme). Several authors reported similar uses of biodiversity where botanical resources for food and medicine are available and accessible to forest users, and biodiversity conservation is a priority [41,42,43,44]. This research could explain the relationship between women gatherers and biodiversity by ethnicity; half of the women gatherers identified with the Mapuche ethnic group (Table A2). Indeed, in Chile and other countries, the traditional knowledge of native fruits is rooted in the food habits of the rural population and indigenous peoples [2,45]. SDGs highlight the relevance of valuing the traditional knowledge of rural communities, and the value of traditional knowledge is a crucial issue in preserving the sustainable use of biodiversity [46].

The collection of cauchao and other ancestral foods as botanical resources is more deeply rooted in the family than the community (Table A2; cultural and family component theme). The women expressed that gathering is a family tradition; their fathers and mothers collected botanical resources (Table A2; luma tree as a non-wood forest product theme). Indeed, women gatherers referred to collecting with their husbands and daughters and desired to preserve gathering as a family tradition. Maintaining gathering as a family tradition is a challenge because some authors have noted that part of the traditional knowledge could be lost due to the migration of the young population from rural to urban areas [2]. Nevertheless, women gatherers also mentioned that they wanted cauchao fruit to exist for future generations; they tried to maintain gathering in their families and town. This denotes the importance of women gatherers in preserving gathering. Thus, we interpret that they collect what they need to preserve.

This research did not observe a community of women gatherers (Table A2; community component theme). Women mentioned they did not collect fruits together with other gatherers. They revealed that few people collect in Cisnes. We speculate that the abundance of large surfaces of native forests and irregular geography (Figure 2) do not favor the contact between women gatherers during collection. Thus, meeting points can be around other laborers and when they attend workshops or seminars (Table A2; entrepreneurship theme). This issue is relevant because previous research has denoted that social projects that fill the gap in women’s empowerment can majorly impact women in the community [47,48,49]. Note that women gatherers denoted that they commonly commercialize cauchao fruit by themselves. This supposed effort is to determine quantities and prices. If a woman gatherer did not know the cost of cauchao fruit commercialized by other gatherers, she could not have the tools to negotiate a reasonable price to commercialize her fruits. Then, we propose that restoring a gatherer community may help to empower women gatherers and their traditions.

4.2. Only Collect What We Need for Our Diet and Nutritional Well-Being

Women gatherers had access to cauchao collected from extreme south forests in Chile. Access to cauchao and other ancestral fruits did not involve any payment for the product because gatherers collect fruits that grow naturally in native forests (Table A2; community component theme). Thus, access to cauchao and other ancestral fruits could contribute to the food security of women gatherers and their families. “Only collect what we need” also reflected that the consumption of cauchao was relevant to the diet of women gatherers and their families. Indeed, other authors have highlighted that ancestral foods as natural resources give variety to a healthy diet [50,51], and dietary diversity has been positively associated with nutritional status [52,53,54]. Therefore, indigenous and traditional knowledge is essential in promoting food and nutrition security.

Like other fresh fruits, cauchao fruit has a high moisture content and a relevant carbohydrate content (Table 2) as part of its macronutrients [21]. Interestingly, cauchao showed a significant dietary fiber content, considering that the Institute of Medicine [55] has recommended an adult’s reference daily fiber intake of 25 to 38 g/day. If we assume a fruit serving of 80 g, consuming one serving of cauchao involves the intake of 8.7 g of total fiber (i.e., 23–35% of the reference daily fiber intake), classifying it as an excellent fiber source. Dietary fiber has been associated with health outcomes and the prevention of non-communicable diseases [56]. Healthy adults’ regular consumption of 5–10 g/day of soluble fiber reduces LDL cholesterol by 4–10% [57].

Furthermore, various medical and observational research has indicated that a high-fiber diet with a consumption of at least 14 g/1000 kcal per day plays a significant role in maintaining a healthy body weight [58]. Access to knowledge on cauchao fruit composition by gatherers could promote consuming and developing food products high in dietary fiber. In this context, access to knowledge is critical in improving agricultural productivity and the incomes of small-scale food producers, particularly women, as declared in SDG 2.3 [46].

Note that women gatherers did not connect the cauchao fruit with dietary fiber. Instead, they associated the fruits with antioxidants and anti-aging properties (Table A2; entrepreneurship and medicinal properties themes). Women gatherers could associate cauchao fruit with sensory properties such as sweetness and flavor (Table A2; fruit sub-theme). Naturalists and previous research have recognized the aromatic properties of other fruits from the Myrtaceae family (e.g., murta) [17]. Women also treasured that cauchao fruit belongs to areas (i.e., extensive native forests) without environmental pollution, contributing to health and well-being.

Luma tree gives by-products that women gatherers could associate with medicinal properties (Table A2; by-products, leaf, and wood subthemes). Women gatherers could collect Luma leaf all year round because luma is an evergreen tree [19]. Luma leaf was dried and used in infusions. In this sense, luma leaves could replace tea or coffee or treat cold or stomach pain (Table A2; medicinal properties theme). The relationship between botanical resources and medicine reflected the importance of native plants as medicinal plants for rural communities, as described previously [45,51].

4.3. Seasonality and Sustainability

This research interprets the phrase “only collect what we need” as a sign of respect for the luma tree as a botanical resource and a sustainable collection of cauchao fruit (Table A2; collection theme). Similar to other non-wood forest products, the abundance of cauchao fruit as a genetic resource has not been quantified. However, the extensive area with native forest in the Aysen region favors its sustainable collection by local gatherer communities. Results showed several products from the luma tree (Table A2; by-products, leaf, and wood subthemes). Luma wood was cut and dried for firewood. Note that low temperatures (i.e., the annual mean of 8 to 9 °C) in the Aysen region force the use of heater systems all year round, and women gatherers described respectful exploitation of luma firewood. Cauchao fruit was a seasonal product obtained from the luma tree (Table A2; seasonality sub-theme). This research observed awareness of a sustainable collection; therefore, it proposes reinforcing sustainable practices in luma tree exploitation to empower women gatherers and their traditions.

This research observed that women gatherers participated in different stages of the food supply chain (Table A2; collection, post-collection handling, processing, and distribution themes and sub-themes). Indeed, women not only participated in fruit collection and consumption, but some of them also participated as processors and distributors (Figure 4A). Women gatherers described two fruit collection techniques according to the product quantity. The first technique was more respectful with the luma tree, but they could collect less quantity of product (Table A2; collection theme). Transport from forests to households did not involve refrigeration. Previous research denoted that post-collection handling is a crucial stage for seasonal products because it determines how seasonal fruits are stored or transformed into processed foods [59]. Indeed, the lack of refrigerated or frozen storage reported by women gatherers limited the use of cauchao fruit for food (Table A2; post-collection handling theme). This lack of cold facilities was consistent with the description of processing and distribution, where women gatherers had limited knowledge about processed foods and distribution channels (Table A2; processing and distribution sub-theme). This denoted the importance of access to knowledge to fill the gap in developing food products by women gatherers, promoting opportunities for value addition, as the United Nations [46] proposed in SDG 2.3.

Several authors indicated that biodiversity may serve to develop products that generate economic income, adding value to ecosystem services [41,42,43,44]. In the case of women gatherers interviewed, the processing of fruits was mainly limited to juice, jams, and liquors (Table A2; entrepreneurship theme). This research observed that knowledge about cauchao was more limited than other native fruits such as calafate and murta (Table A2; other non-wood forest products theme). Most women gatherers sold mainly fresh cauchao fruits to intermediates because they lacked the know-how for food entrepreneurship. Two women were exceptions; they used cauchao for pastry products and syrup and sold these processed products. Then, this research proposes that developing social research projects focused on food technology involving women gatherers can empower them and their traditions.

4.4. Circular Food Economies

Gustavsson et al. [60] showed that food loss occurs in all food groups at any food chain level. Therefore, ancestral fruits should not be an exception. Gatherers did not report food loss along the supply chain (Figure 4A). Then, this research did not observe the quantification of food loss at any level (Table A2; collection, post-collection handling, processing, and distribution themes and sub-themes). Nevertheless, processing can produce considerable food loss (e.g., edible peels and seeds) when cauchao fruit is processed to elaborate juice and jams. Some authors revealed that food systems entail food production, processing, consumption, and the generation of waste that affects the production of new foods [12]. Thus, this research proposes that sustainable food systems for women gatherers (Figure 4B) should consider quantifying food loss and recovering, valorizing, and reusing cauchao by-products to reduce food loss and promote circular food economies. Indeed, there is scarce research on quantifying food loss in Chilean food systems [61]. Previous research from other countries suggested that quantifying food loss and waste determines the potential for reduction, reuse, and recycling, thus contributing to sustainable food systems [62,63,64]. Access to this knowledge by women gatherers could positively impact food processing. For example, previous research has highlighted that edible peels and seeds lost in fruit processing contain considerable dietary fiber and bioactive compounds that can be reused or recycled for producing new foods [65,66,67]. Then, we propose that collaboration among women gatherers and associative projects with different stakeholders of the food industry and academia are necessary for developing new healthy foods and valorizing cauchao by-products. The valuation of by-products follows Chilean environmental policies demanding greater efficiency in the use of resources. This efficiency refers to optimizing the consumption of materials, energy, and water in production processes, seeking to minimize waste and promote sustainability in production [68,69]. Furthermore, disseminating food systems’ characteristics in extreme south forests may help gatherers know and value ancestral fruits and reinforce their sustainable practices.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

The study has one major limitation: using a virtual format (Zoom) to collect data may have affected the relationship between the research team and participants. However, the constraints imposed by the confinements associated with COVID-19 did not allow the interviews to be conducted face-to-face, as initially designed.

To our knowledge, this is the first mixed methods research focused on studying the traditional food knowledge of cauchao and the quantification of macronutrients in cauchao fruit. Despite the chemical analysis being limited to macronutrients, the content of dietary fiber gives insights for future studies into cauchao fruit as an excellent source of dietary fiber.

As a case study, this research was exploratory and represented the experience of a particular group of women gatherers. Nevertheless, the qualitative data methodology will allow new research to explore the knowledge of other women gatherers from the extreme south of Chile.

5. Conclusions

“Only collect what we need” was a phrase from the voices of some women gatherers that represents the main findings of this research. Results showed that gathering for these women was more than just extracting natural resources; it was associated with family, food security, participation in different stages of the food system, and practices that could contribute towards sustainable food systems. For these women gatherers from the extreme south of Chile, the gathering was more rooted in the family than the community and involved household economic income. Some gatherers sold the cauchao fruit, while others developed products they sold in entrepreneurship. Gathering positively impacts food security. These gatherers had physical access to nutritious fruit such as cauchao and other products that grow naturally and are available in the forests of the extreme south of Chile. Indeed, the content of cauchao’s dietary fiber gives insights into its being an excellent source of dietary fiber. Access to knowledge by small-scale food producers, especially women, is part of SDG #2.3. Our results provide knowledge about the traditional use and nutritional content of a fruit unknown to the general population. The approach of this research may help guide knowledge transfer among women gatherers. We propose restoring community aspects and reinforcing sustainable practices in exploiting luma trees performed by women gatherers. We also propose developing social research projects focused on food technology where women gatherers should be involved and can empower them and their traditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.F.; Methodology: C.F., M.B. and P.R. Formal analysis and investigation: C.F., M.B., A.P., C.A. and L.R. Writing—original draft preparation: C.F. and P.R.; Writing—review and editing: M.B., A.P., C.A. and L.R. Funding acquisition: C.F.; Resources: C.F.; Supervision: M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Vicerrectoría de Investigación and Dirección de Pastoral y Cultura Cristiana of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica (ID 191226004; 8 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

The Ethics Committee of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile approved the research procedure (ID 191226004). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Daniela Gómez from the Municipality of Cisnes, Aysen, for contributing as a link with a group of women gatherers. The authors appreciate women gatherers’ valuable time sharing their knowledge and experience. The authors also thank the article’s reviewers per standard peer reviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Interview guide.

Table A1.

Interview guide.

| Section | Question |

|---|---|

| Characterization of gatherer | Please provide information about your birth date, education level, occupation, civil status, number of children, number of children living in the household, identification with some ethnic group, and household income. |

| 1 | Tell us a little about the cauchao fruit. For example, when is it collected? How is it stored? |

| 2 | What is cauchao used for? |

| 3 | What medicinal properties does the cauchao fruit have? |

| 4 | What has been the tradition in your family regarding gathering? |

| 5 | Was your mother a gatherer? |

| 6 | How does it feel to be a gatherer? |

| 7 | How is gathering? |

| 8 | What does the cauchao fruit represent in your community? Do you go out with other gatherers? |

| 9 | What other fruits do you collect? |

| 10 | What would you say to buyers? |

| 11 | What would you like future generations (children and grandchildren) to know about the cauchao fruit and gathering? |

| 12 | Is there anything you would like to tell us? |

Questions performed in individual interviews with 12 women.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Qualitative analyses of interviews.

Table A2.

Qualitative analyses of interviews.

| Themes 1 and Sub-Themes 2 | Findings | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| The cultural and family component 1 | Women generally carry out the collection. They typically collected fruits alone or with a husband. Fruit collection generates a feeling of freedom, contact with nature, and getting out of their domestic and parenting routines. | “I have collected on my own or with my husband, but most of the time, I have been alone because I like to feel that solitude” (WG07). “For me, being a gatherer is a moment of freedom, free from what the household is … because walking in the nature is that, freedom” (WG09). “It is also favorable for me because I feel comfortable and happy, that is, getting up early to collect. It is something that I look forward to every day because I get ready the day before—for example, preparing meals before” (WG010). |

| Community component 1 | They point out that there was no real community of gatherers; other laborers, such as handcrafters, joined them. In general, collecting places were fields or forests located within their properties or properties of relatives. Sometimes, they expressed that they ask permission to collect. An exception was the youngest gatherer, who collected with friends, associating gathering with a group recreational activity. She also collected different types of mushrooms and fruits to develop products related to vegan gastronomy. | “One cannot go into any field to collect” (WG01). “Here in our community, we never get together as gatherers because very few people collect. Maybe some people collect, if they have a little piece of land, I collect cauchao in my daughter’s field” (WG02). “It is a panorama for us to go out and collect... not only the two of us but with friends... Then it is the entertainment of collecting something delicious and getting lost and learning in the forest” (WG11). “We arrive and just pass by, we ask permission from the tree, we ask permission from what surrounds us, and thus, we also give something for what we have received. I have respect for the forest and the land. So, for me, that is asking permission” (WG11). |

| Seasonality 2 | Fruit collection is highly seasonal from December to February. January is the month of the most remarkable production. | “At the end of December or the first days of January, at the latest at the end of January. It all depends on the weather” (WG02). |

| Collection 2 | There were two techniques, depending on the quantity of fruits. The first technique was manual collecting; women gatherers collected each fruit by hand. Although it was slower than the second technique, this technique had the advantage of achieving clean fruits and being careful with the tree. They usually used this technique when they collected alone, to their use, transporting only fruits in buckets. Sometimes, they complemented manual collecting with a hook to bring the branches closer and collect the fruits. The second technique was to shake the tree branches and collect everything that fell on a tarp. A greater quantity could be collected, although it involved cleaning the fruits. Women gatherers put fruits in water, and the remains of branches, stems, and leaves were separated from the fruits by flotation. They usually used this technique when they went with their family or sold quantities up to 100 kg to intermediate grocers. | “Cauchao is also a very delicate product, and it is complicated to collect it... it has its technique to collect it, and we collect what we need” (WG02). “And there we go collecting, removing with our hand or else with scissors, because suddenly someone reaches out with their hand and pulls, and we only damage the tree” (WG11). “Everyone collected what we need. In those years, of course, we did not shake the trees. Because it was for our consumption more than anything” (WG01). “It falls on the canvas; we gather it and put it in a pot or a drum with water. So what does the cauchao do? Cauchao goes to the bottom, and the leaf rises, and there we take out the entire leaf and the clean cauchao. That way, we collect cauchao because it is difficult to gather a significant amount by hand” (WG10). |

| Post-collection handling 1 | Cold fruit storage was uncommon among the participants, although they knew they could freeze fruits for up to 6 months. The fruits were generally processed, consumed immediately, or sold to third parties for freezing or drying. The lack of refrigerated or frozen storage may be due to limited access to facilities for cold storage. | “He said he dried and frozen fruits, but now I do not remember the gentleman’s name because that was about 2 years ago” (WG09). “We do not freeze fruits. We have ways to freeze, but one prioritizes other things, meat or some vegetables” (WG05). |

| Processing and distribution 2 | Gatherers generally consumed fresh fruits immediately; they defined them as candy. Gatherers frequently made juice from fresh fruits, and they strikingly mention syrup. However, most of the gatherers did not know how to prepare syrup. The syrup had a more widespread use than jam. Jam was less known as a product. Several times, “Chicha de cauchao” was mentioned. Liquor is also mentioned, but they did not make liquor in Cisnes. They generally referred to commercial products as processed products manufactured in Coyhaique (Aysen capital), with the fruits they collected in Puerto Cisnes. | “Sometimes we went out to the fields for cauchao collecting, but to eat, just to eat it. It was pure eating, eating, eating. Sometimes we ended up lying on the field eating cauchao” (WG07). “Cauchao is part of all life. I grew up in the countryside, it was like our candy, waiting for it to ripen..”. (WG05). “I sell to a woman who says that there are people who like (cauchao) jam, but there are others who do not. Maybe she says it is because they do not know the product yet” (WG02). |

| By-products 2 | The luma leaf was dried, and the wood was cut and dried for firewood. Gatherers used it to make a wood stove fire that works all year round. We observed respectful exploitation of luma trees for firewood. Gatherers did not report storage of firewood, probably because households in the south had a space for firewood storage. Gatherers also did not report the storage of dried leaves. Perhaps because it was a simple process, they could make infusions with just a few leaves. The use of the leaves did not have a more significant family impact, as was the case with the fruit. | “It allows us another source of income, and we get firewood from the tree. It is important for us. Because in some way it still sustains our family” (WG03). “Most of the year, we have wood heating, and we also have a mesh above the wood stove, where we can dry the fruits we collect” (WG011). “People say ‘there is a lot, a lot’, but there is very little left in the fields here in Cisnes. Moreover, we have to take care of it. We have to collect what we need (WG08). Although true, the luma regenerates quickly because it is humid here. People here say, “I get one luma, and then come out”. Yes, it is like that, but they have already exploited it a lot, and accessing a field with much luma is difficult. So, we are careful to collect. “We are thinking and taking care of our forest, to leave it to our children” (WG10). |

| Entrepreneurship 1 | From the dialogues, we deduced that Cisnes was a supplier of raw materials for Coyhaique. Gatherers did not mention local ventures for processed products. They described family consumption of fresh fruit or fruit juice, the leaf for infusion, or firewood for combustion. Participants valued the instances that provide tools to develop ventures based on their natural resources. They repeated contents such as “It is an antioxidant”, “It has properties”, and “It is used in cosmetics”. However, this seems to have only increased information, which does not translate into practical tools. For example, suppose they do not have the cooling capacity or a dehydrator or were not taught about product development and marketing. In that case, it is unlikely that they will obtain value associated with collecting and selling the fruit, as expressed during the interviews. The exception was the owner of a vegan restaurant, which has derived commercial value from all the products collected. | “I have a person who buys me the cauchao that I collect. I do not work with cauchao because you do not know what to do with it. Apart from syrup, which I do not know how to make, you must know how to do that” (WG02). “I went to a practice where they showed a dehydrator, and I liked the idea. So I have been fighting to have a dehydrator” (WG10). “I remember that we made two deliveries for $500.000. For us, that is good” (WG01). “This fruit is taken outside to Coyhaique, where mini entrepreneurs work with the juice. I give it to a company”. (WG10). “He appeared interested in the product (cauchao) and wanted to buy. Where we live (Cisnes), we have countryside; there is a lot. Now, we never knew why he wanted it” (WG09). “I heard that about the antioxidant once in a workshop. We went to a workshop on plants and fruit trees with a professor who came to give the talk” (WG03). “We did a workshop together... and she used it for flavorings, creams, therapeutic aromas. So, at least I knew the things I did not know about the cauchao fruit. For me, that was new; that is why others are making cosmetics” (WG10). “We began to prepare to receive the fruits that the earth is going to give us, and our way of collecting is always with respect; it will always be with respect. “Moreover, we collect what we need. We already have our places. We have several places here where we not only collect fruits but also collect local edible mushrooms. Furthermore, as I tell you, we are preparing to start collecting. We use cauchao in different ways. We make cauchao sauces, cake, liqueurs, and vinegar. It is one of the fruits that gives us several preparation options. For us, not just cauchao. In general, all the fruits that the territory provides us” (WG11). |

| Other non-wood forest products 1 | Calafate was the most mentioned fruit (more than 80 times). The collection was more organized, generally done in groups, and had buyers. The murta was also mentioned (13 times). The participant who had a vegan restaurant collected different types of edible mushrooms and fruits with a group of friends. She used ancestral fruits in different pastry products. | “... Being able to deliver it and share it with the people of the same town. During the edible mushroom season, we make “changle empanadas” and “gargales empanadas”. We have been making vegan food in this territory for 4 years, and now people are just beginning to (re)value what we do. That is, for example, what happened with the gargal. Many years before, when people began to colonize this territory, they called it the bread of the people. Now they do not go to collect gargal. Very few people collect in this territory. It still makes me sad that most people collect calafate, whether green or ripe. For what? For a company at $2000/kg” (WG11). |

| Luma tree as a non-wood forest product 1 | They value the luma as sustenance, whether through the sale of the fruit, the consumption of firewood, or the infusions of the leaf. The luma is part of their culture; they have family memories, and the most mentioned thing was that it is “natural”. | “It is a product of its people, that they consume it, and take advantage of it. They do not destroy it.... It is a natural product that occurs right here” (WG09). “At least, I am happy collecting fruits. It serves me. It gives me the security of what I am eating; it is something that God provided on earth. Precisely for us to take it, not that we are putting additive things in it” (WG10). “Starting from the fact that it is a natural product, which we know has antioxidant properties, and is delicious. It is not contaminated because it grows naturally in the forest” (WG03). |

| Fruit 2 | Delicious as a candy, better in flavor than other local fruits, although less known. Some participants even said that sheep and birds ate the fruit. They were beginning to (re)value this ancestral fruit more. | “The flavor is wonderful; I swear that the flavor of cauchao makes a difference. I find that it is much richer than calafate” (WG11). “It is a delicious fruit, which is the most natural thing on this earth. For example, this region is natural, without any contamination” (WG04). “If you consume the fresh fruit, you know how delicious it is. The sweetness… The flavor is different” (WG10). “It was a fruit that was there, but no one knew that it was edible, so no... sheep and birds consumed it” (WG09). |

| Leaf 2 | Ancestrally consolidated as an infusion. Gatherers mentioned Leaf in all interviews except MC06. | “You use the leaf. Suddenly, we want to drink an infusion in the countryside, as we say, “agüita” (WG07). |

| Wood 2 | Firewood for combustion. Wood stoves are essential in southern homes. They even had a mesh placed over the kitchen to dry fruits. | “Most of the year, we have wood heating, and we also have a mesh above the wood stove, where we can dry the fruits we collect” (WG11). |

| Medicinal properties 1 | Gatherers recognized luma leaf as a natural medicine against colds and abdominal pain and mentioned that their ancestors also used it. They did not give that ancestral valuation to the fruit. However, they have heard in courses or on the Internet that the fruit has antioxidant or other properties. | “For aging, I think, something like that... Wow, I am not sure what else. I think it is for many things” (WG01). “They say that cauchao is like an antioxidant... but I do not know much about its properties, because this topic is little known… We do not know if it can be good for health” (WG02). “They told me it was an antioxidant... I do not know if it is true. Because I have always eaten cauchao” (WG04). “They say all dark products, like calafate, have medicinal properties. However, I do not know exactly what properties (WG05). The truth is that I was looking for information, and there is no information regarding cauchao” (WG09). “We took the (infusion) for colds and digestion. My mother gave it to us when we had stomach pain” (WG01). |

WG: Woman gatherer. Thematic analyses of 12 interviews conducted on October 2020.

References

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredes, C.; Montenegro, G. Chilean Plants as a Source of Polyphenols. In Natural Antioxidants and Biocides from Wild Medicinal Plants; Céspedes, C., Sampietro, D., Seigler, D., Rai, M., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 116–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fredes, C.; Bernales, M.; Parada, A.; Hermosilla, C.; Robert, P. Recolectoras de Cauchao, Conocer Para Valorar. Rev. Diálogos 2021, 16, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, C. Historia Física y Política de Chile. Botánica. Tomo Segundo; Museo de Historia Natural de Santiago: Santiago, Chile, 1846. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, J. Compendio de La Historia Geográfica, Natural y Civil Del Reyno de Chile; Madrid, Spain. 1788. Available online: https://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-8028.html (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Wilhem de Mösbach, E. Botánica Indígena; Editorial Andrés Bello: Santiago, Chile, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gusinde, M. Expedición a la Tierra del Fuego; Publicaciones del Museo de Etnología y Antropología de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud. Medicamentos Herbarios Tradicionales; Seremi de Salud Arica y Parinacota: Santiago, Chile, 2008.

- Heinrich, M.; Lardos, A.; Leonti, M.; Weckerle, C.; Willcox, M.; Applequist, W.; Ladio, A.; Lin Long, C.; Mukherjee, P.; Stafford, G. Best Practice in Research: Consensus Statement on Ethnopharmacological Field Studies—ConSEFS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 211, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinceti, B.; Termote, C.; Ickowitz, A.; Powell, B.; Kehlenbeck, K.; Hunter, D. The Contribution of Forests and Trees to Sustainable Diets. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4797–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Forest Food Systems and Their Contribution to Food Security and Nutrition. Defining Priorities for Sustainable Use; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fassio, F.; Tecco, N. Circular Economy for Food: A Systemic Interpretation of 40 Case Histories in the Food System in Their Relationships with SDGs. Systems 2019, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marticorena, C. Contribución a La Estadística de La Flora Vascular de Chile. Gayana Botánica 1990, 47, 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Framework for Action on Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. Viaje de Un Naturalista Alrededor del Mundo; Joaquín Gil: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Fredes, C.; Parada, A.; Salinas, J.; Robert, P. Phytochemicals and Traditional Use of Two Southernmost Chilean Berry Fruits: Murta (Ugni Molinae Turcz) and Calafate (Berberis buxifolia Lam.). Foods 2020, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Medioambiente. Inventario nacional de Especies de Chile. Available online: http://especies.mma.gob.cl/CNMWeb/Web/WebCiudadana/Default.aspx (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Rodriguez, R.; Marticorena, C.; Alarcón, D.; Baeza, C.; Cavieres, L.; Finot, V.L.; Fuentes, N.; Kiessling, A.; Mihoc, M.; Pauchard, A.; et al. Catálogo de Las Plantas Vasculares de Chile. Gayana. Botánica 2018, 75, 1–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Forestier, J.; León-Lobos, P.; Marticorena, A.; Celis-Diez, J.L.; Giovannini, P. Native Useful Plants of Chile: A Review and Use Patterns. Econ. Bot. 2019, 73, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. FoodData Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Aljefree, N.; Ahmed, F. Association between Dietary Pattern and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease among Adults in the Middle East and North Africa Region: A Systematic Review. Food Nutr. Res. 2015, 59, 27486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calton, E.K.; James, A.P.; Pannu, P.K.; Soares, M.J. Certain Dietary Patterns Are Beneficial for the Metabolic Syndrome: Reviewing the Evidence. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, S.L.; McKinley, M.C.; Young, I.S.; Cardwell, C.R.; Woodside, J.V. The Effect of Increasing Fruit and Vegetable Consumption on Overall Diet: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.D.; Li, Y.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rosner, B.A.; Sun, Q.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Rimm, E.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Stampfer, M.J.; et al. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Mortality. Circulation 2021, 143, 1642–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, L.T.; Lajolo, F.M.; Genovese, M.I. Potential Dietary Sources of Ellagic Acid and Other Antioxidants among Fruits Consumed in Brazil: Jabuticaba (Myrciaria Jaboticaba (Vell.) Berg). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ah-Hen, K.S.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Moraga, N.O.; Lemus-Mondaca, R. Modelling of Rheological Behaviour of Pulps and Purées from Fresh and Frozen-Thawed Murta (Ugni Molinae Turcz) Berries. Int. J. Food Eng. 2012, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredes, C.; Robert, P. The Powerful Colour of the Maqui (Aristotelia Chilensis [Mol.] Stuntz) Fruit. J. Berry Res. 2014, 4, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredes, C.; Robert, P. Maqui (Aristotelia Chilensis (Mol.) Stuntz). In Fruit and Vegetable Phytochemicals: Chemistry and Human Health; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODEPA. Región de de Aysén del General Carlos Ibañez del Campo. Información Regional; ODEPA: Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE). Censo 2017—Cuadros Estadísticos. Available online: https://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/sociales/censos-de-poblacion-y-vivienda/poblacion-y-vivienda (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Macías, A. Plan de Gobierno 2021–2025 Región de Aysén. Available online: https://gorecloud.goreaysen.cl/owncloud/index.php/s/u4iVKWLR4aNiLgv (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE). Síntesis de Resultados: Encuesta Suplementaria de Ingresos 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE): Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno Regional de Aysén. Actualización Política Regional de Localidades Aisladas Región de Aysén; Chile. 2019. Available online: https://www.goreaysen.cl/controls/neochannels/neo_ch95/appinstances/media204/Resexe_814_19_Politica_de_Localidades_Aisladas_actualizada_2019.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Approaches to Inquiry. In Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Variety in Qualitative Inquiry: Theoretical Orientations. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 3rd. ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dilia, M.; Barrera, M.; Tonon, G.; Victoria, S.; Salgado, A. Investigación Cualitativa: El Análisis Temático Para El Tratamiento de La Información Desde El Enfoque de La Fenomenología Social 1. Univ. Humanística 2012, 4807, 195–226. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; The Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, H.; Southgate, D.A.T. Food Composition Data: Production, Management and Use, 2nd ed.; Springer Nature: Rome, Italy, 2003; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gooch, M.; Bucknell, D.; LaPlain, D.; Dent, B.; Whitehead, P.; Felfel, A.; Nikkel, L.; Maguire, M. The Avoidable Crisis of Food Waste: Technical Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.secondharvest.ca/getmedia/58c2527f-928a-4b6f-843a-c0a6b4d09692/The-Avoidable-Crisis-of-Food-Waste-Technical-Report.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Bassaganya-Riera, J.; Berry, E.M.; Blaak, E.E.; Burlingame, B.; le Coutre, J.; van Eden, W.; El-Sohemy, A.; German, J.B.; Knorr, D.; Lacroix, C.; et al. Goals in Nutrition Science 2020–2025. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, 606378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclère, D.; Obersteiner, M.; Barrett, M.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Chaudhary, A.; De Palma, A.; DeClerck, F.A.J.; Di Marco, M.; Doelman, J.C.; Dürauer, M.; et al. Bending the Curve of Terrestrial Biodiversity Needs an Integrated Strategy. Nature 2020, 585, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, Á.; Burlingame, B. Biodiversity and Nutrition: A Common Path toward Global Food Security and Sustainable Development. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French Collier, N.; Sayer, J.; Boedhihartono, A.; Hanspach, J.; Abson, D.; Fischer, J. System Properties Determine Food Security and Biodiversity Outcomes at Landscape Scale: A Case Study from West Flores, Indonesia. Land 2018, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L.; Turner, N.J. “The Old Foods Are the New Foods!”: Erosion and Revitalization of Indigenous Food Systems in Northwestern North America. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 596237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Wark, K.; Volkeimer, J.; Mortenson, R.; Trainor, J.; Presley, J.; Jauregui-Dusseau, A.; Clyma, K.R.; Jernigan, V.B.B. The Development of a Community-Led Alaska Native Traditional Foods Gathering. Health Promot. Pract. 2023, 24, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, K.; Neathway, C. Community Champions for Safe, Sustainable, Traditional Food Systems. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valaitis, R.F.; McEachern, L.W.; Harris, S.; Dick, T.; Yovanovich, J.; Yessis, J.; Zupko, B.; Corbett, K.K.; Hanning, R.M. Annual Gatherings as an Integrated Knowledge Translation Strategy to Support Local and Traditional Food Systems within and across Indigenous Community Contexts: A Qualitative Study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 47, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, N.J. “That Was Our Candy!”: Sweet Foods in Indigenous Peoples’ Traditional Diets in Northwestern North America. J. Ethnobiol. 2020, 40, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.M.; Alavez, V.; Castro-Porras, L.; Martínez, Y.; Cerritos, R. Analysis of the Current Agricultural Production System, Environmental, and Health Indicators: Necessary the Rediscovering of the Pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican Diet? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkotoky, K.; Unisa, S.; Gupta, A.K. State-Level Dietary Diversity as a Contextual Determinant of Nutritional Status of Children in India: A Multilevel Approach. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2018, 50, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimond, M.; Ruel, M.T. Dietary Diversity Is Associated with Child Nutritional Status: Evidence from 11 Demographic and Health Surveys. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2579–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithya, D.J.; Bhavani, R.V. Dietary Diversity and Its Relationship with Nutritional Status among Adolescents and Adults in Rural India. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2018, 50, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, I.S.; Orfila, C. Dietary Fiber in the Prevention of Obesity and Obesity-Related Chronic Diseases: From Epidemiological Evidence to Potential Molecular Mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 8752–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.; Rosner, B.; Willett, W.W.; Sacks, F.M. Cholesterol-Lowering Effects of Dietary Fiber: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Ziani, K.; Mititelu, M.; Oprea, E.; Neacșu, S.M.; Moroșan, E.; Dumitrescu, D.-E.; Roșca, A.C.; Drăgănescu, D.; Negrei, C. Therapeutic Benefits and Dietary Restrictions of Fiber Intake: A State of the Art Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, M.C. Selection and Use of Postharvest Technologies as a Component of the Food Chain. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, crh43–crh46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; Otterdijk, V.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/mb060e/mb060e00.htm (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Fredes, C.; Jara, M.; Moya, J.L.; Reyes-Jara, A. Reduce, Reuse and Recycle: A Critical Review of Scientific Knowledge on Food Loss and Waste in Chile. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2023, 50, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allesch, A.; Brunner, P.H. Material Flow Analysis as a Decision Support Tool for Waste Management: A Literature Review. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini, E.; Iacovidou, E.; Gronow, J.; Voulvoulis, N. Food Flows in the United Kingdom: The Potential of Surplus Food Redistribution to Reduce Waste. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 2018, 68, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, C.; Stoessel, F.; Baier, U.; Hellweg, S. Quantifying Food Losses and the Potential for Reduction in Switzerland. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasyliev, G.; Vorobyova, V. Valorization of Food Waste to Produce Eco-Friendly Means of Corrosion Protection and “Green” Synthesis of Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6615118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassoff, E.S.; Guo, J.X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.C.; Li, Y.O. Potential Development of Non-Synthetic Food Additives from Orange Processing by-Products—A Review. Food Qual. Saf. 2021, 5, fyaa035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Esparza, L.M.; la Mora, Z.V.; Vázquez-Paulino, O.; Ascencio, F.; Villarruel-López, A. Bell Peppers (Capsicum annum L.) Losses and Wastes: Source for Food and Pharmaceutical Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ODEPA. Estudio de Economía Circular en el Sector Agroalimentario Chileno; ODEPA: Santiago, Chile, 2019.

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. Economía Circular. Available online: https://economiacircular.mma.gob.cl/hoja-de-ruta/ (accessed on 7 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).