The Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Residents’ Cultural Consumption in China: An Urban-Rural Difference Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. A Theoretical Model

2.2. Mechanisms Analysis

2.2.1. Liquidity Constraints

2.2.2. Precautionary Savings

2.2.3. Payment Convenience

3. Data and Empirical Strategy

3.1. Construction of Variables

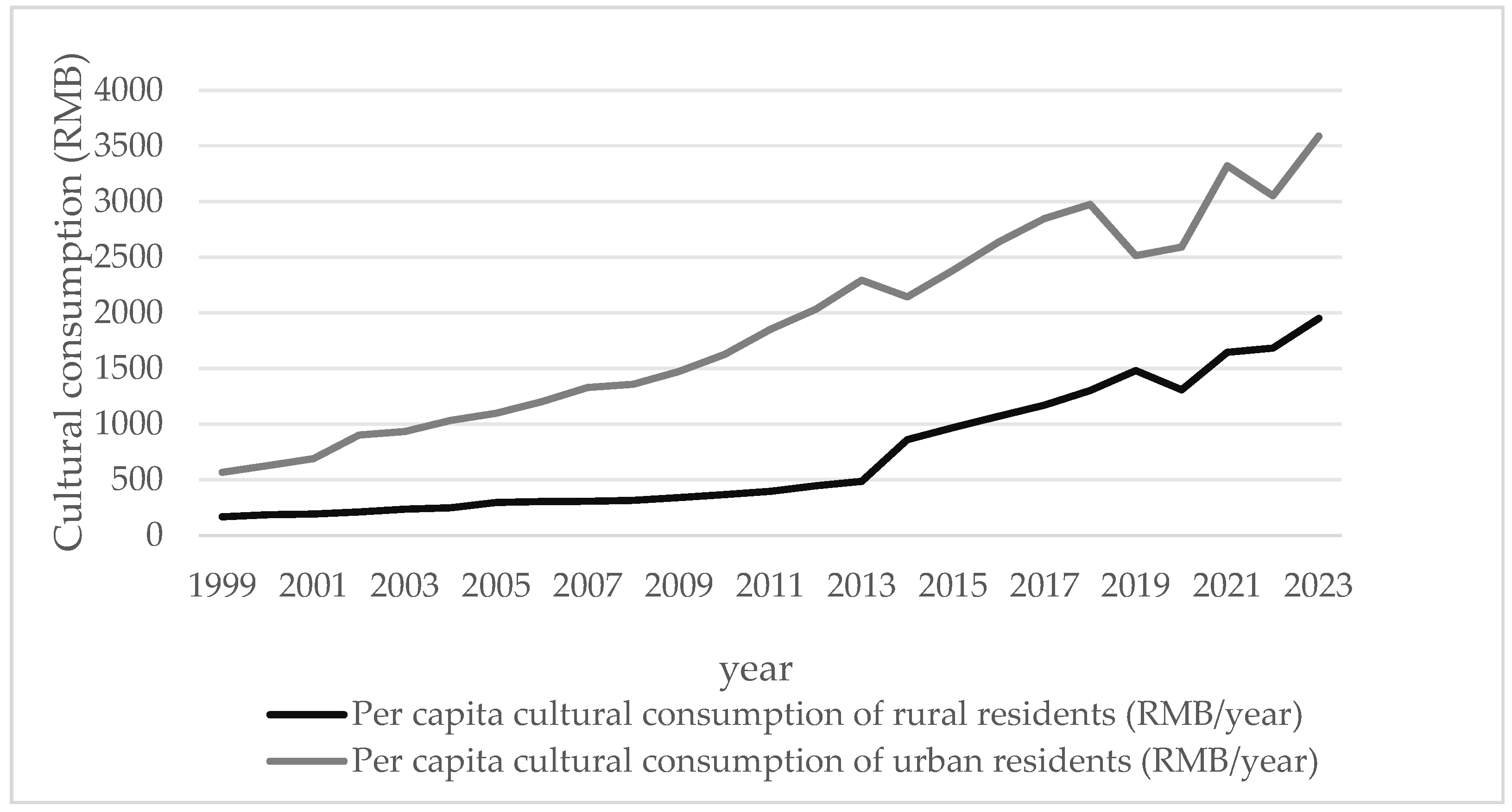

3.1.1. Cultural Consumption

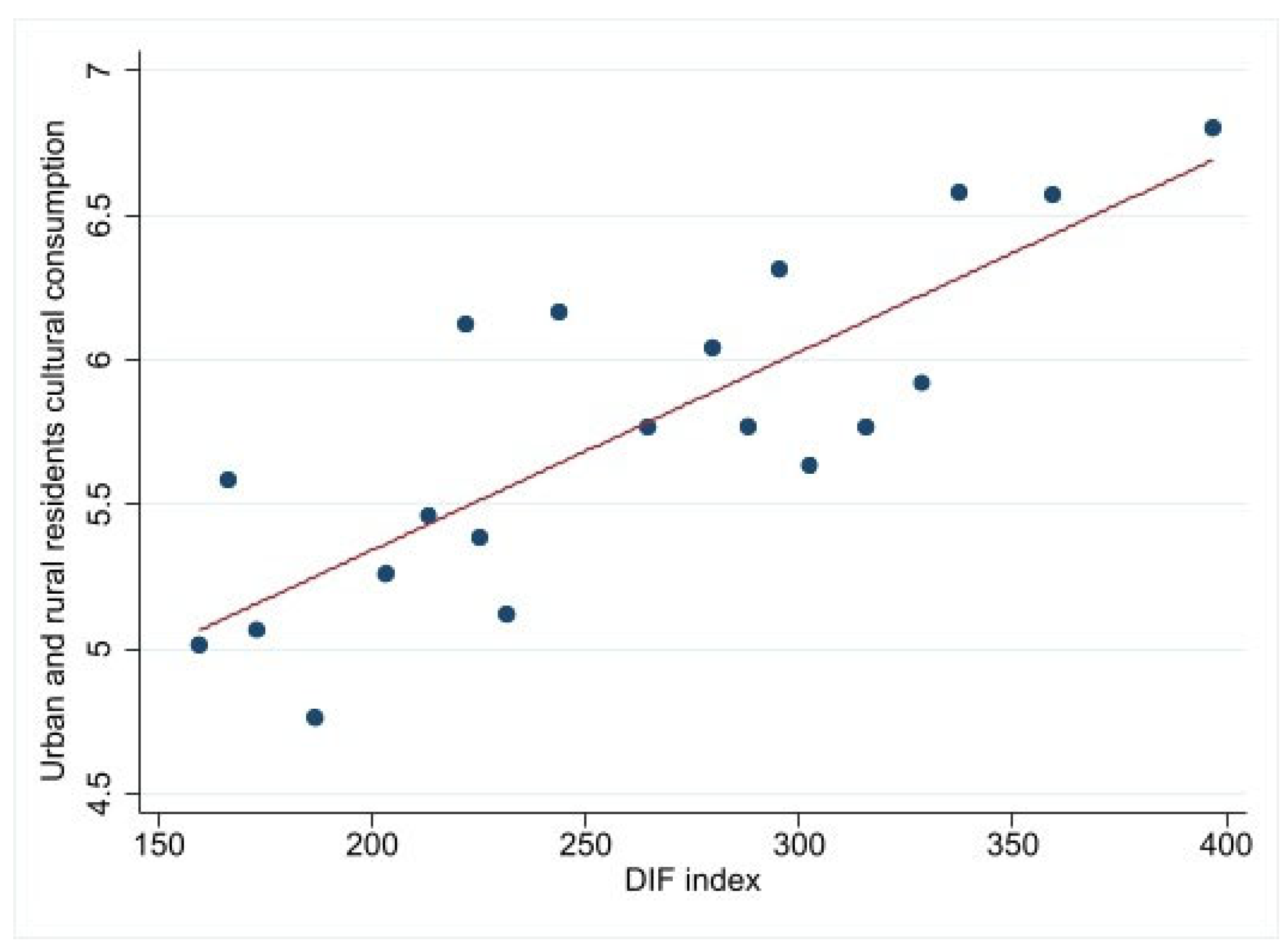

3.1.2. Digital Inclusive Finance

3.1.3. Control Variables

3.2. Data Source

3.3. Empirical Model

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Baseline Regression

4.2. Endogeneity Test

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.4. Mechanism Examination

4.4.1. Mechanism Examination of Liquidity Constraints

4.4.2. Mechanism Examination of Precautionary Savings

4.4.3. Mechanism Examination of Payment Convenience

5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Credit Business

5.2. Insurance Business

5.3. Sub-Index Measuring Payment Convenience

6. Conclusions and Suggestions for Policy

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katz-Gerro, T. Cultural consumption research: Review of methodology, theory, and consequence. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2004, 14, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veghes, C. Cultural Consumption as a Trait of a Sustainable Lifestyle: Evidence from the European Union. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 9, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crociata, A.; Agovino, M.; Sacco, P. Recycling waste: Does culture matter? J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2015, 55, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolika, M.; Baltzis, A. Curiosity’s pleasure? Exploring motives for cultural consumption. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2020, 25, e1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Heo, S. Arts and cultural activities and happiness: Evidence from Korea. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1637–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buncák, J.; Hrabovská, A.; Sopóci, J. The Way of Life and the Cultural Consumption of Social Classes in Slovak Society. Sociologia 2019, 51, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, J. Intra-cultural consumption of rural landscapes: An emergent politics of redistribution in Indonesia. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Q.; Xu, A.; Zheng, Q. Promoting or Inhibiting? Digital Inclusive Finance and Cultural Consumption of Rural Residents. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Hilbert, M.; Frey, S. Breaking the Structural Reinforcement: An Agent-Based Model on Cultural Consumption and Social Relations. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2023, 41, 848–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, H. Digital Finance Affects the Consumption Path of Urban Digital Finance and Residents: The Expansion of Digital Finance to Consumption in the Perspective of Space Spillover. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Hou, G. Mobile payment, digital inclusive finance, and residents’ consumption behavior research. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0288679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, L.; Martens, B. Digital music consumption on the Internet: Evidence from clickstream data. Inf. Econ. Policy 2016, 34, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylland, O.; Kleppe, B. Accountable countability. Digital cultural consumption among young people and the tools used to measure it. Cult. Trends 2023, 33, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Pamuk, H.; Ramrattan, R.; Uras, B. Payment instruments, finance and development. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 133, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Zhai, C.; Zhao, S. Does digital finance promote household consumption upgrading? An analysis based on data from the China family panel studies. Econ. Model. 2023, 125, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J. The impact of digital finance on household consumption: Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2020, 86, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yin, Z.; Jiang, J. The effect of the digital divide on household consumption in China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 87, 102593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.P. Crossing the digital divide: The impact of the digital economy on elderly individuals? Consumption upgrade in China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.; Love, I. The Real Impact of Improved Access to Finance: Evidence from Mexico. J. Financ. 2014, 69, 1347–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manshad, M.; Brannon, D. Haptic-payment: Exploring vibration feedback as a means of reducing overspending in mobile payment. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Yin, Z. Accessibility of financial services and household consumption in China: Evidence from micro data. N. Am. Econ. Financ. 2020, 53, 101213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayir, T. Hedonic and utilitarian consumption with compulsive buying relationship use of credit card: A research on online marketplace. J. Mehmet Akif Ersoy Univ. Econ. Adm. Sci. Fac. 2021, 8, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlan, D.; Zinman, J. Expanding Credit Access: Using Randomized Supply Decisions to Estimate the Impacts. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 433–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Ouyang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Shi, Z. The impact of digital economy on household private insurance participation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 95, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. The impact of digital finance on household insurance purchases: Evidence from micro data in China. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.-Issues Pract. 2022, 47, 538–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L. Effect of digital inclusive finance on common prosperity and the underlying mechanisms. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupas, P.; Robinson, J. Why don’t the poor save more? Evidence from health savings experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 1138–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Vatsa, P.; Ma, W.; Zheng, H. Does mobile payment adoption really increase online shopping expenditure in China: A gender-differential analysis. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J. The influence mechanism of internet finance on residents’ online consumption. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 70, 106323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Aqel, M. Blockchain implementation to manage banking mobile payments. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2021, 37, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkes, H.; Joyner, C.; Pezzo, M.; Nash, J.; Siegel-Jacobs, K.; Stone, E. The psychology of windfall gains. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1994, 59, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivetz, R.; Zheng, Y. The effects of promotions on hedonic versus utilitarian purchases. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, H. The use of noncash payment methods for regular payments and the household demand for cash: Evidence from Japan. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 2020, 71, 719–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, X. Income and cultural consumption in China: A theoretical analysis and a regional empirical evidence. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2023, 216, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Z.; Bai, Y. A study of the impact of digital finance usage on household consumption upgrading: Based on financial asset allocation perspective. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ma, F.; Deng, W.; Pi, Y. Digital inclusive finance and rural household subsistence consumption in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Kong, T.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z. Measuring China’s digital financial inclusion: Index compilation and spatial characteristics. China Econ. Q. 2020, 19, 1401–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Li, J. The nexus between internet use and consumption diversity of rural household. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Cao, R. Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Urban Carbon Emission Intensity: From the Perspective of Green and Low-Carbon Travel and Clean Energy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zang, X. Digital finance’s impact on household service consumption-the perspective of heterogeneous consumers. Appl. Econ. 2024, 56, 7014–7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definitions and Assignment | Total Sample | Urban | Rural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | ||

| Consumption | Residents’ cultural consumption, log transformation of household cultural expenditure | 5.739 | 3.950 | 6.396 | 3.782 | 5.037 | 4.005 |

| DIF | One period lagged DIF index | 257.839 | 65.177 | 266.483 | 67.178 | 248.873 | 61.832 |

| Gender | Gender of the head of household, male = 1, female = 0 | 0.513 | 0.500 | 0.506 | 0.500 | 0.520 | 0.500 |

| Age | Age of the head of household in the sample | 45.148 | 16.087 | 44.130 | 15.934 | 46.221 | 16.169 |

| Health | Health of the head of household, 5 levels of healthiness, healthy = 5, unhealthy = 1 | 2.956 | 1.474 | 2.991 | 1.407 | 2.920 | 1.540 |

| Education | Education of the head of household, years of education | 7.767 | 4.956 | 9.300 | 4.778 | 6.143 | 4.608 |

| Family size | Family size, number of the family members | 3.838 | 1.858 | 3.548 | 1.724 | 4.143 | 1.945 |

| Child dependency | Child dependency, the ratio of children (Age < 14) to the household labor force | 0.148 | 0.355 | 0.138 | 0.353 | 0.158 | 0.355 |

| Elder dependency | Elder dependency, the ratio of elder (Age > 65) to the household labor force | 0.035 | 0.143 | 0.030 | 0.128 | 0.040 | 0.157 |

| Asset | The net worth of the household, log transformation of household asset | 11.966 | 2.730 | 12.403 | 2.708 | 11.500 | 2.681 |

| Debt | Household debt, log transformation of household indebted | 3.981 | 5.354 | 3.888 | 5.457 | 4.086 | 5.244 |

| Traditional finance | Provincial traditional finance, the ratio of RMB loan balances of provincial financial institutions to GDP | 1.482 | 0.453 | 1.49 | 0.46 | 1.479 | 0.452 |

| Variables | Baseline Regression | IV Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Total | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | |

| DIF | 0.016 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.046 *** | 0.034 *** | 0.068 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.004) | (0.007) | (0.010) | |

| Gender | −0.011 | −0.048 | −0.002 | −0.045 | 0.003 |

| (0.036) | (0.049) | (0.053) | (0.049) | (0.052) | |

| Age | −0.011 ** | −0.008 | −0.011 | −0.008 | −0.010 |

| (0.005) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Age squared | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Health | −0.005 | −0.002 | −0.010 | 0.000 | −0.012 |

| (0.013) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.000) | (0.019) | |

| Education | 0.004 | 0.012 | −0.002 | 0.011 | −0.003 |

| (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Family size | 0.520 *** | 0.543 *** | 0.511 *** | 0.542 *** | 0.511 *** |

| (0.022) | (0.035) | (0.030) | (0.036) | (0.032) | |

| Elder dependency | −0.438 *** | −0.308 *** | −0.592 *** | −0.317 *** | −0.578 *** |

| (0.075) | (0.114) | (0.104) | (0.111) | (0.106) | |

| Child dependency | 0.330 *** | 0.470 *** | 0.074 | 0.462 | 0.029 |

| (0.101) | (0.148) | (0.141) | (0.153) | (0.137) | |

| Asset | 0.070 *** | 0.063 *** | 0.086 *** | 0.063 *** | 0.086 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| Debt | 0.024 *** | 0.030 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.021 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.187) | (0.006) | |

| Traditional finance | −0.177 | −0.158 | −0.029 | 0.184 | 0.264 |

| (0.110) | (0.156) | (0.181) | (0.187) | (0.218) | |

| Household FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| F-value | 73.97 | 32.70 | 49.87 | 31.60 | 38.45 |

| R-squared/centered R-squared | 0.728 | 0.735 | 0.727 | 0.040 | 0.057 |

| Observations | 35,946 | 17,998 | 17,948 | 17,998 | 17,948 |

| Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistics | 13.930 | 9.984 | |||

| Cragg-Donald Wald-F statistics | 536.912 | 881.365 | |||

| p-value of Chow test | 0.006 | 0.000 | |||

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Urban | Rural | Rural | |

| First Stage | Second Stage | First Stage | Second Stage | |

| DIF | Consumption | DIF | Consumption | |

| Instrumental variables | −0.036 *** | −0.042 *** | ||

| (0.006) | (0.006) | |||

| DIF | 0.034 *** | 0.068 *** | ||

| (0.007) | (0.010) | |||

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistics | 13.930 | 9.984 | ||

| [0.000] | [0.002] | |||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F statistics | 536.912 | 881.365 | ||

| {16.380} | {16.380} | |||

| Observations | 17,998 | 17,998 | 17,948 | 17,948 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | |

| Consumption | Consumption | The Proportion of Cultural Consumption in Total Consumption | ||||

| DIF | 0.017 *** | 0.049 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.049 *** | 0.002 ** | 0.009 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| R-squared | 0.768 | 0.756 | 0.730 | 0.726 | 0.561 | 0.613 |

| Observations | 13,480 | 14,268 | 15,689 | 17,477 | 17,998 | 17,948 |

| p-value of Chow test | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.002 | |||

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | |

| Liquidity Constraints | Precautionary Savings (Insurance Expenditure) | Payment Convenience | ||||

| DIF | −0.001 *** | −0.005 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.067 ** | 0.001 *** | 0.004 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.056) | (0.031) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| R-squared | 0.611 | 0.583 | 0.641 | 0.585 | 0.628 | 0.580 |

| Observations | 17,998 | 17,948 | 17,998 | 17,948 | 17,998 | 17,948 |

| p-value of Chow test | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.011 | |||

| Categorized/Sub-Categorized Indices | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | |||||

| Credit business | 0.011 *** | 0.032 *** | ||||||

| (0.003) | (0.004) | |||||||

| Insurance business | 0.012 *** | 0.006 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||||

| R-squared | 0.735 | 0.726 | 0.735 | 0.724 | ||||

| Observations | 17,998 | 17,948 | 17,998 | 17,948 | ||||

| p-value of Chow test | 0.000 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Categorized/Sub-categorized indices | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | ||

| Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | |||

| BDFC | 0.009 *** | 0.038 *** | ||||||

| (0.003) | (0.004) | |||||||

| DDIF | 0.006 *** | 0.009 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||||||

| Payment business | 0.007 *** | 0.024 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||||||

| R-squared | 0.737 | 0.726 | 0.737 | 0.724 | 0.737 | 0.726 | ||

| Observations | 17,998 | 17,948 | 17,998 | 17,948 | 17,998 | 17,948 | ||

| p-value of Chow test | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Cai, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. The Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Residents’ Cultural Consumption in China: An Urban-Rural Difference Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411118

Sun X, Cai Z, Wang C, Wang J. The Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Residents’ Cultural Consumption in China: An Urban-Rural Difference Perspective. Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):11118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411118

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xiaohui, Zhijian Cai, Chongyu Wang, and Jing Wang. 2024. "The Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Residents’ Cultural Consumption in China: An Urban-Rural Difference Perspective" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 11118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411118

APA StyleSun, X., Cai, Z., Wang, C., & Wang, J. (2024). The Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Residents’ Cultural Consumption in China: An Urban-Rural Difference Perspective. Sustainability, 16(24), 11118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411118