Safety Culture in SMEs of the Food Industry: A Case Study and Best Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

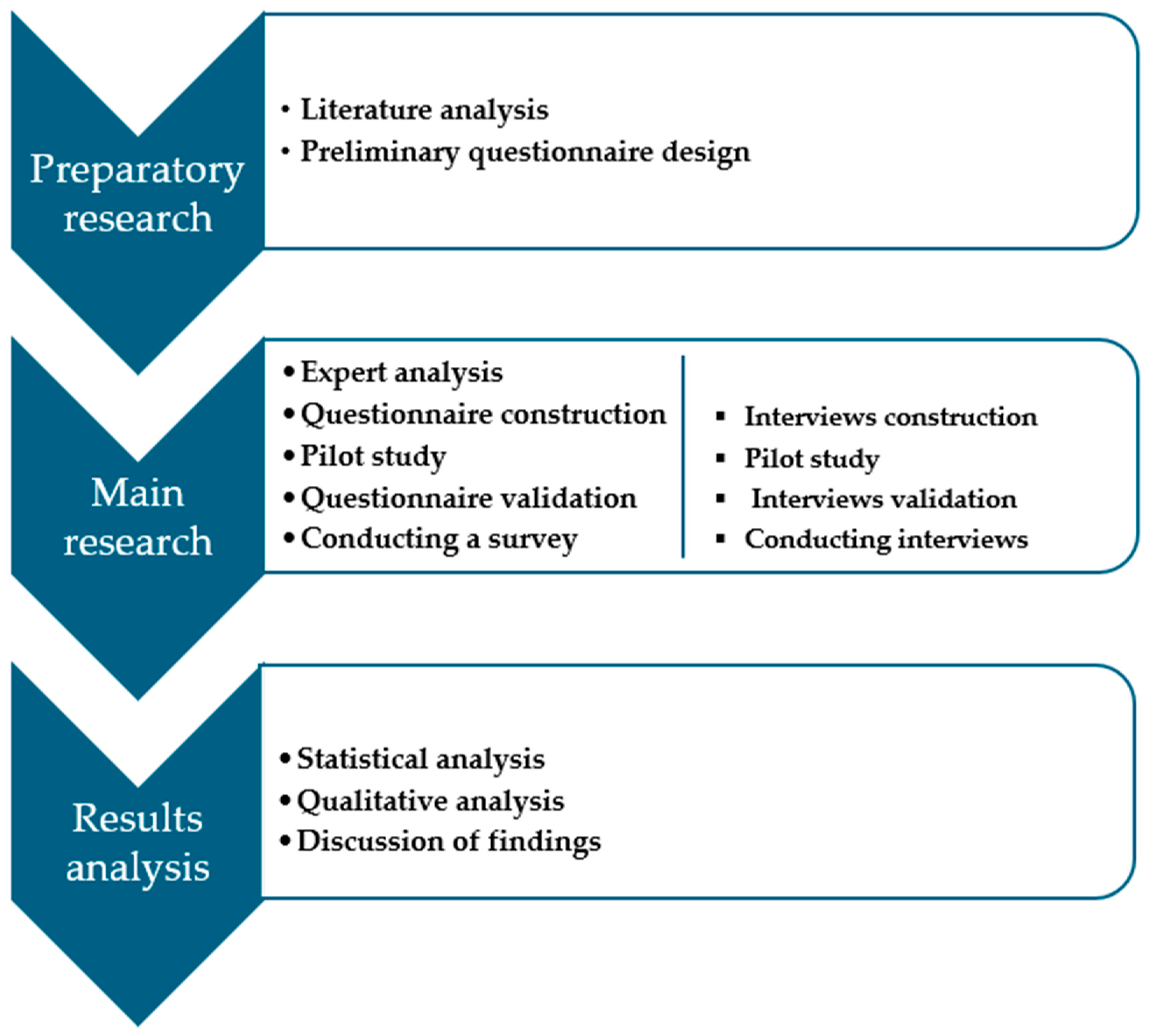

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

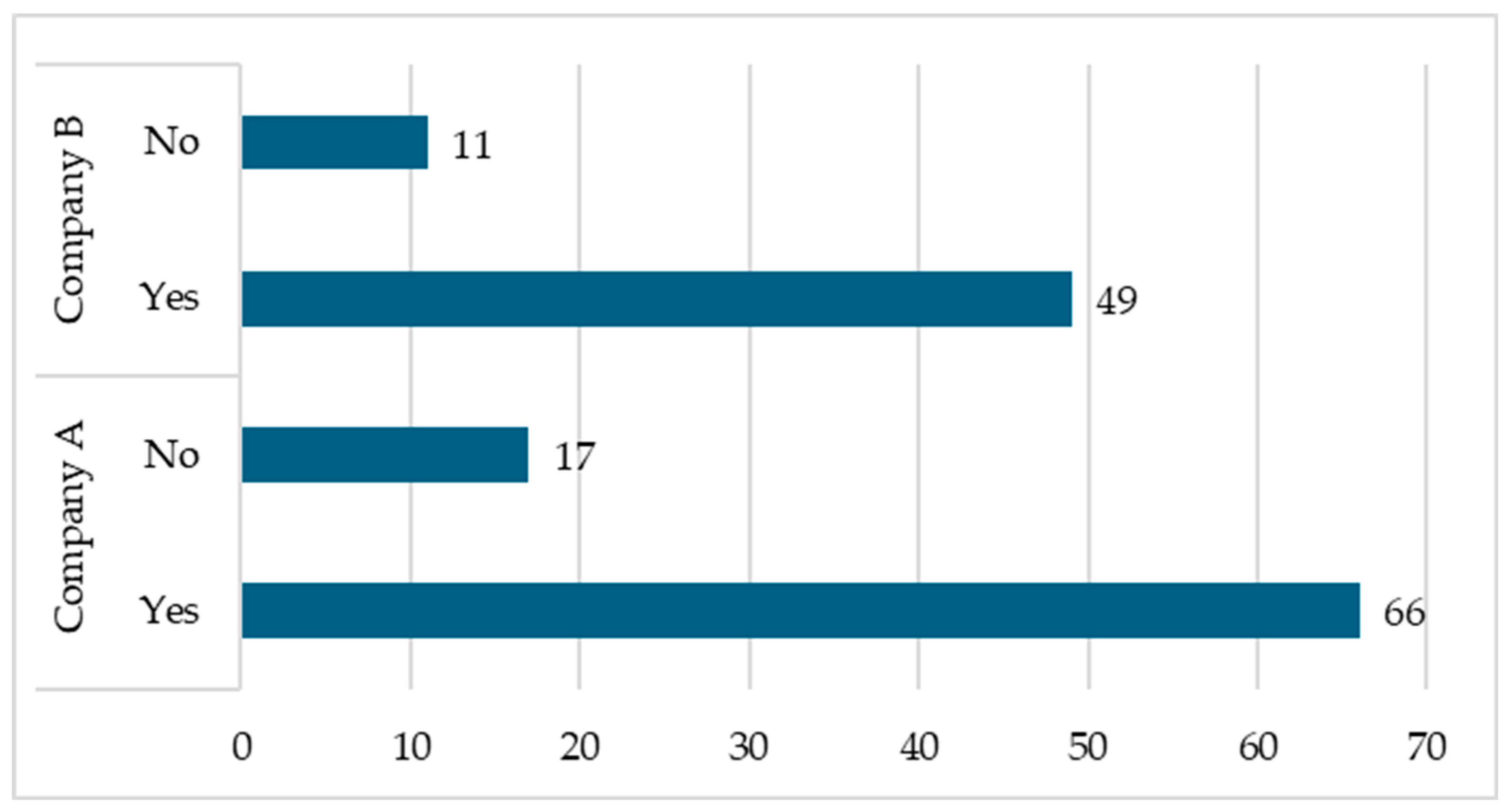

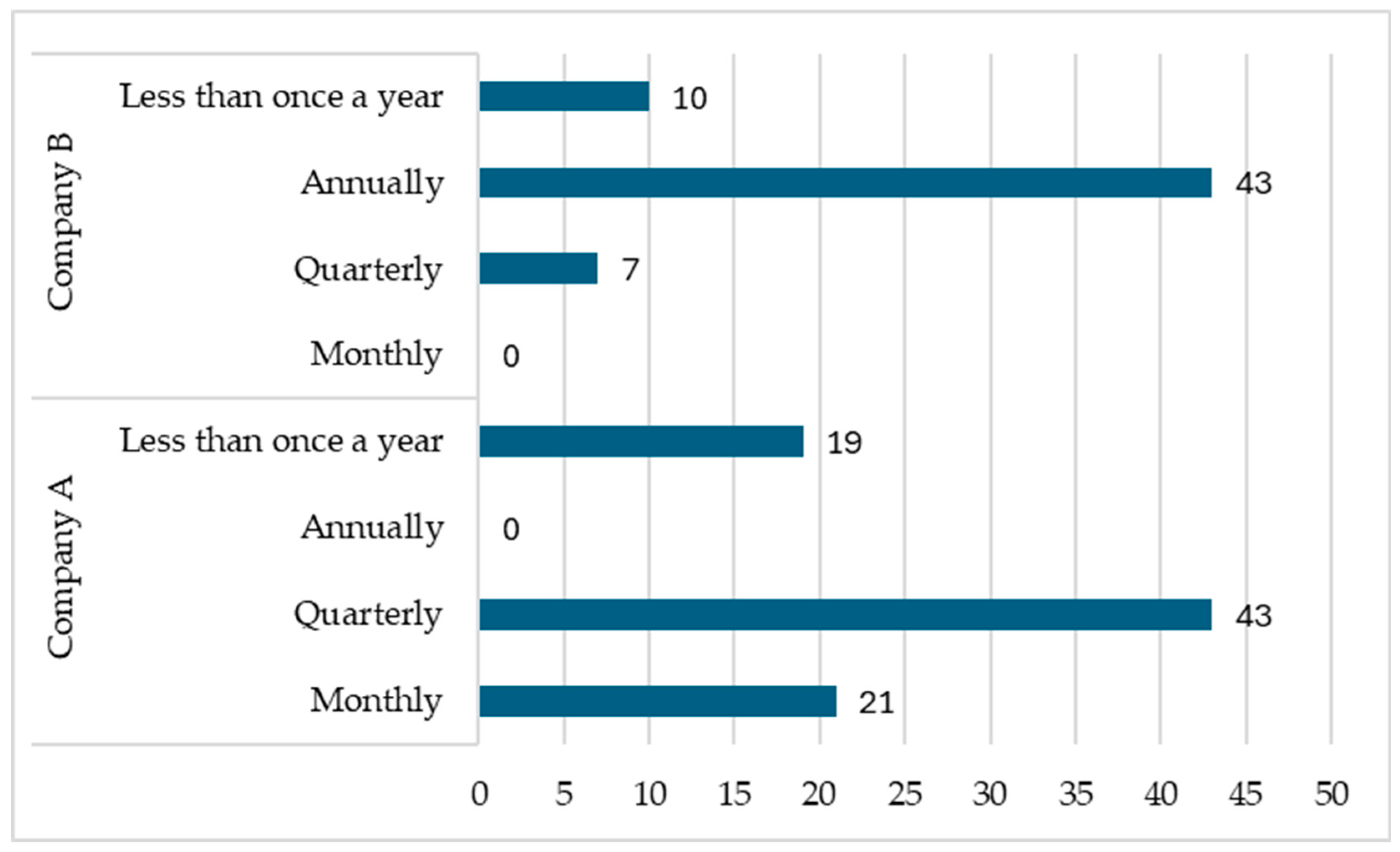

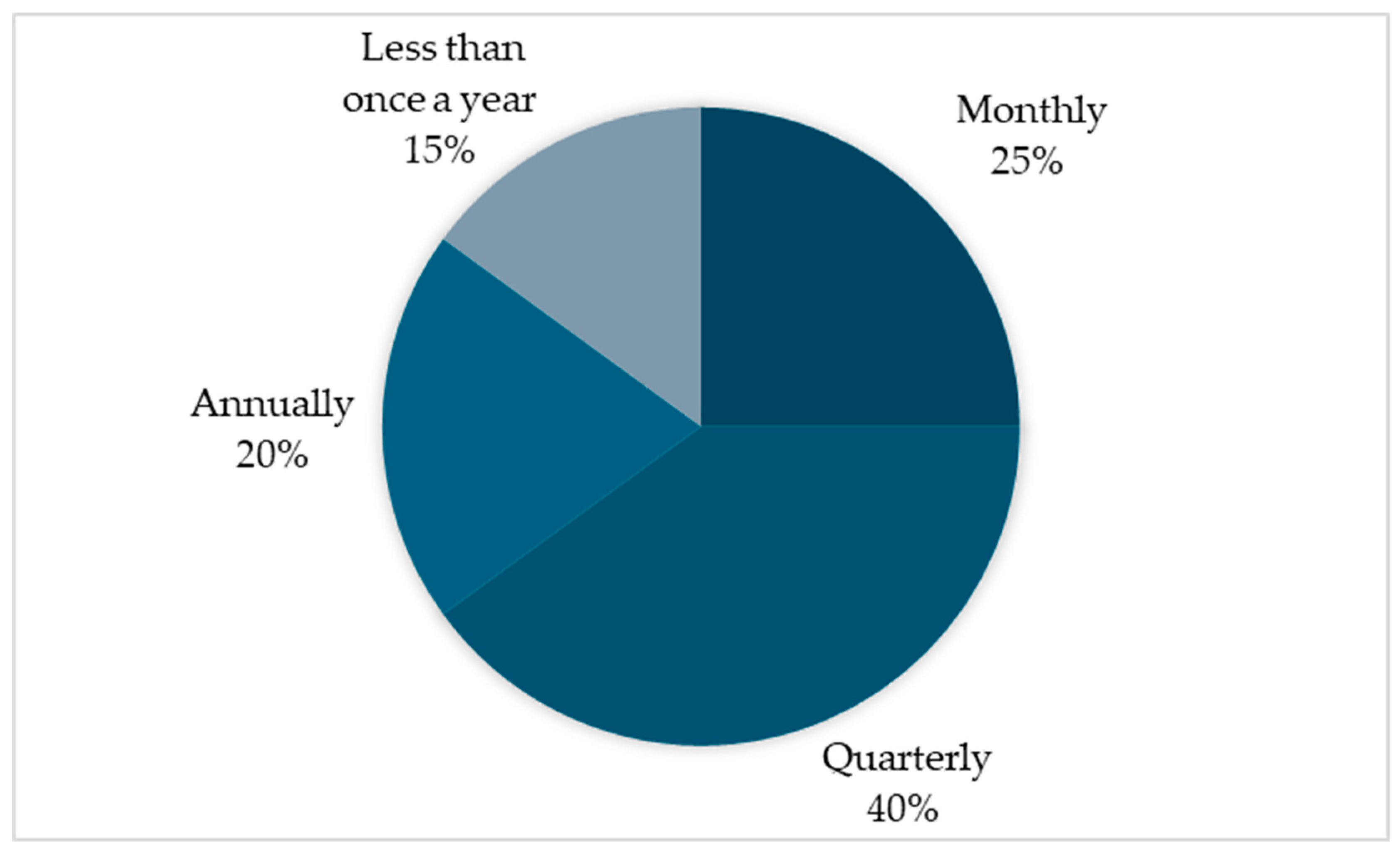

3.1. Questionnaire Survey

3.2. Questionnaire Interview

4. Discussion

4.1. Strategic Recommendations for Implementing a Sustainable Safety Culture

4.2. Long-Term Effects of Implementing a Sustainable Safety Culture

4.3. Impact of a Sustainable Safety Culture on Company Efficiency and Employee Morale in the Food Industry

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Sustainable Safety Culture in a Manufacturing Enterprise

- Please complete the following survey regarding the safety culture in your organization. Your responses are anonymous and will be used exclusively for research purposes.

- General Information

- How long have you been working in this organization?

- (a)

- Less than 1 year

- (b)

- 1–3 years

- (c)

- 4–6 years

- (d)

- More than 6 years

- What is your position?

- (a)

- Production employee

- (b)

- Manager

- (c)

- Safety department employee

- (d)

- Administrative employee

- What is your educational background?

- (a)

- Vocational

- (b)

- Secondary

- (c)

- Higher education

- Understanding of Safety Policy

- 4.

- Are you familiar with the safety policy in your organization?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- 5.

- How often are safety training sessions organized?

- (a)

- Monthly

- (b)

- Quarterly

- (c)

- Annually

- (d)

- Less than once a year

- 6.

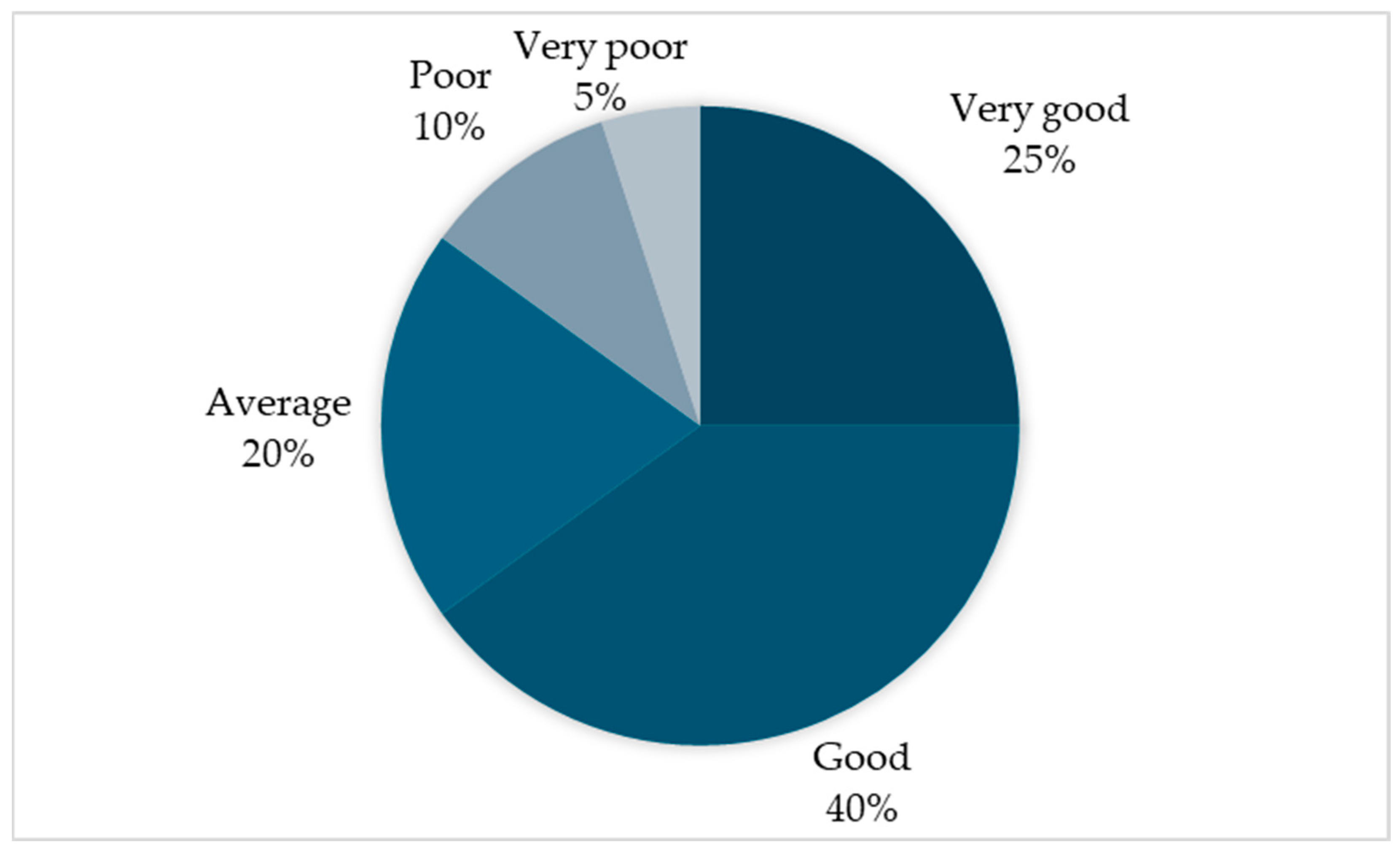

- How would you rate the quality of the safety training sessions?

- (a)

- Very good

- (b)

- Good

- (c)

- Average

- (d)

- Poor

- (e)

- Very poor

- 7.

- Are safety information materials (e.g., brochures, instructions, or videos) available in your organization?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- Management Involvement

- 8.

- How often does management participate in safety training sessions?

- (a)

- Regularly

- (b)

- Occasionally

- (c)

- Rarely

- (d)

- Never

- 9.

- Do you believe that management promotes safety in the workplace?

- (a)

- Strongly agree

- (b)

- Agree

- (c)

- Not sure

- (d)

- Disagree

- (e)

- Strongly disagree

- 10.

- How often does management organize safety meetings?

- (a)

- Monthly

- (b)

- Quarterly

- (c)

- Annually

- (d)

- Less than once a year

- Communication and Collaboration

- 11.

- How would you rate the quality of safety communication in your organization?

- (a)

- Very good

- (b)

- Good

- (c)

- Average

- (d)

- Poor

- (e)

- Very poor

- 12.

- Do you have the opportunity to report safety concerns?

- (a)

- Yes, without hesitation

- (b)

- Yes, but with hesitation

- (c)

- No, I do not have the opportunity

- 13.

- Does the organization encourage the reporting of incidents and accidents?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- 14.

- How often do you participate in safety meetings?

- (a)

- Regularly

- (b)

- Occasionally

- (c)

- Rarely

- (d)

- Never

- Impressions and Opinions

- 15.

- What changes in safety have you noticed in the past year?

- Open response: __________

- 16.

- What suggestions do you have for improving the safety culture in the organization?

- Open response: __________

- 17.

- How would you rate the availability of protective equipment (e.g., helmets, gloves, and safety glasses)?

- (a)

- Very good

- (b)

- Good

- (c)

- Average

- (d)

- Poor

- (e)

- Very poor

- 18.

- How often do you use the provided protective equipment?

- (a)

- Always

- (b)

- Often

- (c)

- Rarely

- (d)

- Never

- 19.

- What has been your experience in responding to emergency situations?

- (a)

- Strongly positive

- (b)

- Positive

- (c)

- Neutral

- (d)

- Negative

- (e)

- Strongly negative

- Employee Participation

- 20.

- Do you feel involved in safety-related decision-making processes?

- (a)

- Strongly agree

- (b)

- Agree

- (c)

- Not sure

- (d)

- Disagree

- (e)

- Strongly disagree

- 21.

- Do you participate in initiatives aimed at improving workplace safety?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- Continuous Improvement

- 22.

- How often does the organization review safety-related incidents?

- (a)

- Regularly

- (b)

- Occasionally

- (c)

- Rarely

- (d)

- Never

- 23.

- Does the organization implement changes based on incident reviews?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- Sustainability and Environment

- 24.

- What environmental protection actions does your organization undertake?

- Open response: __________

- 25.

- Does the organization integrate safety strategy with environmental policy?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- Stakeholder Collaboration

- 26.

- How often does the organization collaborate with stakeholders (e.g., suppliers and clients) regarding safety?

- (a)

- Regularly

- (b)

- Occasionally

- (c)

- Rarely

- (d)

- Never

- 27.

- Does the organization gather feedback from stakeholders on its safety policy?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- Additional Information

- 28.

- Would you like to add anything about safety in your organization?

- Open response: __________

Appendix B

- Introduction

- •

- Purpose of the interview:

- ○

- Explain to the participant the purpose of the research, which is to understand how a sustainable safety culture impacts the organization and to identify the key factors shaping it;

- ○

- Emphasize the importance of this study in developing effective safety strategies.

- •

- Confidentiality rules:

- ○

- Assure the participant that their responses will be kept confidential and used solely for research purposes;

- ○

- Inform them of the option to pause the interview at any time and discuss consent for recording the conversation (if applicable).

- •

- Duration:

- ○

- Inform the participant that the interview will last approximately 30–45 min, depending on the depth of responses.

- General Questions

- Please tell me about your experience in this organization.

- ○

- How long have you worked at this company?

- ○

- What is your position, and what are your main responsibilities?

- How do you assess the overall safety culture in your organization?

- ○

- What strengths do you observe in safety practices?

- ○

- What areas do you think need improvement?

- Safety Policy

- Are you familiar with the safety policy in your organization?

- ○

- What are the key elements of this policy that are important to you?

- ○

- Do you feel this policy is clearly communicated to employees?

- How often do you participate in safety training?

- ○

- How would you rate the quality of these training sessions? Are they tailored to your needs?

- ○

- What topics were covered in recent training sessions, and how relevant were they to you?

- Management Engagement

- How does the organization’s management promote workplace safety?

- ○

- Do managers regularly participate in safety training and meetings?

- ○

- What specific actions do leaders take to inspire employees to follow safety protocols?

- What mechanisms does management use to monitor the safety culture?

- ○

- Are safety audits conducted? How often?

- ○

- What actions are taken in response to audit results?

- Communication and Collaboration

- How would you evaluate the communication of safety within your organization?

- ○

- What communication channels are available for safety information (e.g., meetings, emails, or bulletin boards)?

- ○

- Do you feel comfortable reporting safety concerns? What are your experiences in this area?

- Does the organization encourage the reporting of incidents and accidents?

- ○

- What are the accident reporting procedures? Are they well understood by employees?

- ○

- Are there any support mechanisms for employees who report incidents?

- Employee Participation

- What is your experience with employee involvement in safety-related decision-making processes?

- ○

- Do you feel that your opinion is considered in safety-related decisions?

- ○

- Can you give examples where your input impacted safety policies?

- What safety initiatives are undertaken by employees?

- ○

- Are there working groups or safety committees you can participate in?

- ○

- What ideas for safety improvement have you proposed or observed?

- Continuous Improvement

- How often does the organization review safety-related incidents?

- ○

- Are post-incident sessions held to analyze them? What insights were gained from recent cases?

- Does the organization make changes based on employee feedback?

- ○

- What changes have you noticed in safety procedures in response to employee feedback?

- ○

- What innovative solutions have been implemented recently?

- Sustainability and Environment

- What actions does your organization take regarding environmental protection?

- ○

- Are workplace safety and environmental protection integrated within the organization’s policies?

- ○

- What ecology-related initiatives are undertaken, and how do they impact workplace safety?

- Stakeholder Collaboration

- •

- How does the organization collaborate with stakeholders on safety matters?

- ○

- What is your experience in working with suppliers and clients in terms of safety?

- •

- Do you think feedback from stakeholders is taken into consideration?

- ○

- Can you provide examples where the organization responded to stakeholder opinions?

- Conclusion

- Would you like to add anything else about the safety culture in your organization?

- ○

- What suggestions do you have for improving workplace safety culture?

- Are there any questions you would like to ask me as the interviewer?

- Thank You

- •

- Express gratitude for participating in the interview:

- ○

- Thank the participant for their time and willingness to share their experience;

- ○

- Emphasize the value of their contribution to the research.

- •

- Information on next steps:

- ○

- Explain how the collected data will be used and when they can expect feedback or research results.

References

- Jain, A.; Leka, S.; Zwetsloot, G. Managing Health, Safety and Well-Being; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, D.; Jayakumar, V.; Gunarathne, N.; Samudrage, D. Implementing health and safety strategies for business sustainability: The use of management controls systems. Saf. Sci. 2023, 164, 106183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, V.C.; Paraskevopoulou, A.; Stavropoulos, P. A modelling-based framework for carbon emissions calculation in additive manufacturing: A stereolithography case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 11, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, B. Towards the environmentally friendly manufacturing industry–the role of infrastructure. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bourhis, F.; Kerbrat, O.; Hascoet, J.Y.; Mognol, P. Sustainable manufacturing: Evaluation and modeling of environmental impacts in additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 69, 1927–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Miller, J.; Vezza, J.; Mayster, M.; Raffay, M.; Justice, Q.; Al Tamimi, Z.; Hansotte, G.; Sunkara, L.D.; Bernat, J. Additive manufacturing: A comprehensive review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, D.; Zefinetti, F.C.; Spreafico, C.; Regazzoni, D. Comparative life cycle assessment of two different manufacturing technologies: Laser additive manufacturing and traditional technique. Procedia CIRP 2022, 105, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Despeisse, M. Additive manufacturing and sustainability: An exploratory study of the advantages and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1573–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.; Carmona-Aparicio, G.; Lei, I.; Despeisse, M. Energy and material efficiency strategies enabled by metal additive manufacturing—A review for the aeronautic and aerospace sectors. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokare, S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Godina, R. Life cycle assessment of additive manufacturing processes: A review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 68, 536–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellens, K.; Baumers, M.; Gutowski, T.G.; Flanagan, W.; Lifset, R.; Duflou, J.R. Environmental dimensions of additive manufacturing: Mapping application domains and their environmental implications. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S49–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Singh, S.; Kopperi, H.; Ramakrishna, S.; Mohan, S.V. Comparative job production based life cycle assessment of conventional and additive manufacturing assisted investment casting of aluminium: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, W.R.; Qi, H.; Kim, I.; Mazumder, J.; Skerlos, S.J. Environmental aspects of laser-based and conventional tool and die manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, V.C.; Stavropoulos, P.; Chryssolouris, G. A critical review on the environmental impact of manufacturing: A holistic perspective. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 603–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, F.O.; Ani, E.C.; Ebirim, W.; Montero, D.J.P.; Olu-lawal, K.A. Integrating renewable energy solutions in the manufacturing industry: Challenges and opportunities: A review. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 674–703. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, D.; Seyda, V.; Wycisk, E.; Emmelmann, C. Additive manufacturing of metals. Acta Mater. 2016, 117, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.; Mendes, F.; Barbosa, J. Certification and integration of management systems: The experience of Portuguese small and medium enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJoy, D.M. Behavior change versus culture change: Divergent approaches to managing workplace safety. Saf. Sci. 2005, 43, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xing, Y.; Luo, L.; Yu, R. Evaluating the effectiveness of Behavior-Based Safety education methods for commercial vehicle drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 117, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabiesz, P.; Tutak, M. Developing a culture of safety for sustainable development and public health in manufacturing companies—A case study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Lacey, J.; Zhang, A.; Leipold, S. The social licence to operate: A critical review. Foresty 2016, 89, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skład, A. Assessing the impact of processes on the Occupational Safety and Health Management System’s effectiveness using the fuzzy cognitive maps approach. Saf. Sci. 2019, 117, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, D.; Afonso, P.; Rodrigues, M.A. Integrated management systems as a key facilitator of occupational health and safety risk management: A case study in a medium-sized waste management firm. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.S.; Ahad, M.A.; Nafis, M.T.; Alam, M.A.; Biswas, R. Introducing “For transforming our world”: A proposal for the 2030 agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 129030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haight, J.M.; Kecojevic, V. Automation vs. human intervention: What is the best fit for the best performance? Process Saf. Prog. 2005, 24, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnicka, J.; Kabiesz, P.; Palka, D.; Gajewska, P.; Islam, E.U.; Szymanek, D. Evaluation of the effectiveness of employers and H&S services in relation to the COVID-19 system in Polish manufacturing companies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Bradley, J.C.; Wallace, J.C.; Burke, M.J. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daily, B.F.; Huang, S.C. Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Lawrie, M.; Hudson, P. A framework for understanding the development of organisational safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2006, 44, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christos, S.C.; Christos, G. Data-centric operations in the oil & gas industry by the use of 5G mobile networks and industrial IoT (IIoT). In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Digital Telecommunications, Athens, Greece, 22 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, D. SC in industrial organizations: Theoretical and applied implications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1980, 65, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. A group-level model of SC: Testing the effect of group climate on microaccidents in manufacturing jobs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwan, S.R.; Bhatia, M.P.S. SD in Industry 4.0. In A Roadmap to Industry 4.0: Smart Production, Sharp Business and SD; Nayyar, A., Kumar, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. Relation between occupational safety management and firm performance. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nævestad, T.O. Mapping research on culture and safety in high-risk organizations: Arguments for a sociotechnical understanding of safety culture. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 2009, 17, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldenmund, F.W. The nature of safety culture: A review of theory and research. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 215–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. Safety climate and safety behaviour. Aust. J. Manag. 2002, 27, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Davey, J.; Armstrong, K. Returning to the roots of culture: A review and re-conceptualisation of safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2013, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburumman, M.; Newnam, S.; Fildes, B. Evaluating the effectiveness of workplace interventions in improving safety culture: A systematic review. Saf. Sci. 2019, 115, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, S. Foundations of Safety Science: A Century of Understanding Accidents and Disasters; Routledge: England, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves Filho, A.P.; Waterson, P. Maturity models and safety culture: A critical review. Saf. Sci. 2018, 105, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coze, J.C. Outlines of a sensitising model for industrial safety assessment. Saf. Sci. 2013, 51, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumpal, I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2025–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayob, A.N.; Hassan, C.R.C.; Hamid, M.D. Safety culture maturity measurement methods: A systematic literature review. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2022, 80, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Xu, K.L.; Li, J.; Yao, X.; Wu, C.; Xu, Q. A new accident causation theory based on systems thinking and its systemic accident analysis method of work systems. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2022, 158, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, E.; Khan, F.; Abbassi, R. Importance of human reliability in process operation: A critical analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 211, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiesz, P.; Bartnicka, J. Modern training methods in the field of occupational safety. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI 2019), Seville, Spain, 11–13 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, R.G.; Dunn, J.C.; Hayes, B.K.; Kalish, M.L. A test of two processes: The effect of training on deductive and inductive reasoning. Cognition 2020, 199, 104223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, F.; Podila, P.; Powers, C. Creating a culture of safety in the emergency department: The value of teamwork training. J. Nurs. Adm. 2013, 43, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, H.; Khan, F.; Ahmed, S. A risk-based shutdown inspection and maintenance interval estimation considering human error. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2016, 100, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri, S.M.; Alzahrani, S.M.; Alwafi, A.M. Modeling and assessment of human and organization factors of nuclear safety culture in Saudi Arabia. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2023, 404, 112176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Love, P.E.D.; Luo, H.; Ding, L. Computer vision for behaviour-based safety in construction: A review and future directions. Adv. Eng. Inf. 2020, 43, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwetsloot, G.; van Kampen, J.; Steijn, W.; Post, S. Ranking of process safety cultures for risk-based inspections using indicative safety culture assessments. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2020, 64, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestani, N.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Asadnia, M.; Khan, F. Human reliability assessment for complex physical operations in harsh operating conditions. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2020, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, E.S. The Psychology of Safety: How to Improve Behaviors and Attitudes on the Job; Chilton Book Company: Radnor, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Fung, I.W.H. Behavior, attitude, and perception toward safety culture from mandatory safety training course. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2012, 138, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemn, E.; Bofinger, C.; Clif, D.; Hassall, M.E. Examining the relationship between safety culture maturity and safety performance of the mining industry. Saf. Sci. 2019, 113, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Guo, D. Human factors risk assessment and management: Process safety in engineering. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2018, 113, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldissone, G.; Comberti, L.; Bosca, S.; Murè, S. The analysis and management of unsafe acts and unsafe conditions. Data collection and analysis. Saf. Sci. 2019, 119, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, D.; Khan, F.; Veitch, B. Occupational accident models—Where have we been and where are we going? J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2006, 19, 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, M.; Wang, Q.; Khan, F. Analysis of sustainability metrics from a process design and operation perspective. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2023, 177, 1351–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharp, R.G. A perspective on unifying culture and psychology: Some philosophical and scientific issues. J. Theor. Philos. Psychol. 2007, 27, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.L.C.; Amaral, F.G. Critical factors of success and barriers to the implementation of occupational health and safety management systems: A systematic review of literature. Saf. Sci. 2019, 117, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecuła, K. Analysis of asymmetric VR games–Steam platform case study. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecuła, K. Virtual reality applications market analysis—On the example of Steam digital platform. Informatics 2022, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecuła, K. Application of virtual reality for education at technical university. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI 2019), Seville, Spain, 11–13 November 2019; IATED: Seville, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sleiman, A.A.; Sigurjonsdottir, S.; Elnes, A.; Gage, N.A.; Gravina, N.E. A quantitative review of performance feedback in organizational settings (1998–2018). J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2020, 40, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J. Cost savings in workplace safety initiatives: A financial analysis of accident prevention. J. Occup. Health Saf. 2018, 12, 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. Br. Med. J. 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D. Safety Culture: Implementing Effective Workplace Safety Programs; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Naji, G.M.A.; Isha, A.S.N.; Mohyaldinn, M.E.; Leka, S.; Saleem, M.S.; Rahman, S.M.N.B.S.A.; Alzoraiki, M. Impact of safety culture on safety performance; mediating role of psychosocial hazard: An integrated modelling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, D.N.; Liu, M.; Ling, F.Y. A comparative study on adopting human resource practices for safety management on construction projects in the United States and Singapore. Int. J. Project Manag. 2011, 29, 1018–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S. Safety climate in construction site environments. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2002, 128, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurin, T.A. Safety inspections in construction sites: A systems thinking perspective. Accident Anal. Prev. 2016, 93, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. Fundamentals of systems ergonomics/human factors. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksorn, T.; Hadikusumo, B.H. Critical success factors influencing safety program performance in Thai construction projects. Saf. Sci. 2008, 46, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, R.; McAuliffe, E. A systematic review of factors that enable psychological safety in healthcare teams. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2020, 32, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative reviews: Flexible, rigorous, and practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittman, K.; Hughes, S. Increased nursing participation in multidisciplinary rounds to enhance communication, patient safety, and parent satisfaction. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. 2018, 30, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, R.; Quinlan, M.; McNamara, M. OHS inspectors and psychosocial risk factors: Evidence from Australia. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcroft, C.A.; Punnett, L. Work environment risk factors for injuries in wood processing. J. Saf. Res. 2009, 40, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grill, M.; Samuelsson, A.U.; Matton, E.; Norderfeldt, E.; Rapp-Ricciardi, M.; Räisänen, C.; Larsman, P. Individualized behavior-based safety-leadership training: A randomized controlled trial. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 87, 332–344, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulzer-Azaroff, B.; Fellner, D.J. Searching for performance targets in the behavioral analysis of occupational health and safety: An assessment strategy. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 1984, 6, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwatka, N.V.; Goldenhar, L.M.; Johnson, S.K. Change in frontline supervisors’ safety leadership practices after participating in a leadership training program: Does company size matter? J. Saf. Res. 2020, 74, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, J.; Krauesslar, V.; Avery, R. Safety coaching: A literature review of coaching in high hazard industries. Ind. Commer. Train. 2015, 47, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Barling, J. Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 2010, 24, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Hughes, D.J.; Epitropaki, O.; Thomas, G. In pursuit of causality in leadership training research: A review and pragmatic recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.J.; Woods, S.A.; Guillaume, Y.R. The effectiveness of workplace coaching: A meta-analysis of learning and performance outcomes from coaching. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, D.M. Exploring the role of emotional intelligence in behavior-based safety coaching. J. Saf. Res. 2007, 38, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouma, D.; Canbaloglu, G.; Treur, J.; Wiewiora, A. Adaptive network modeling of the influence of leadership and communication on learning within an organization. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2023, 79, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P. Implementing a safety culture in a major multi-national. Saf. Sci. 2007, 45, 697–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, K.; Whitaker, S.M.; Flin, R. Safety climate, safety management practice and safety performance in offshore environments. Saf. Sci. 2003, 41, 641–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Factor | Demographic Relationships | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | Company A | Company B | ||

| 83 (58%) | 60 (42%) | |||

| Professional experience | 0–1 | 1–3 | 4–6 | 6 or more |

| 14 (10%) | 29 (20%) | 36 (25%) | 64 (45%) | |

| Position | Production employee 98 (69%) | Manager 32 (22%) | Safety department employee 2 (1%) | Administrative employee 11 (8%) |

| Education level | Vocational education | Secondary | Higher education | |

| 79 (55%) | 43 (30%) | 21 (15%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kabiesz, P. Safety Culture in SMEs of the Food Industry: A Case Study and Best Practices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411185

Kabiesz P. Safety Culture in SMEs of the Food Industry: A Case Study and Best Practices. Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):11185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411185

Chicago/Turabian StyleKabiesz, Patrycja. 2024. "Safety Culture in SMEs of the Food Industry: A Case Study and Best Practices" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 11185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411185

APA StyleKabiesz, P. (2024). Safety Culture in SMEs of the Food Industry: A Case Study and Best Practices. Sustainability, 16(24), 11185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411185