Abstract

This study empirically investigated the drivers of port competitiveness among low-, upper-, and high-income countries in the Middle East and North Africa region. It explored the effects of country-level competitiveness, logistic performance, and ease of doing business on port competitiveness for 17 countries from the region using a 14-item scale and covering the years 2010 to 2022. Port competitiveness indicators were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis to determine the research constructs’ validity. Structural path analysis was deployed to verify hypotheses concerning effects between conceptualized variables. The findings demonstrate that in high-income countries, an increase in country competitiveness notably enhances port sustainability and competitiveness. Conversely, in low-income countries, higher country competitiveness appears to diminish port competitiveness. For countries with average income, the association is relatively neutral, exhibiting a slight positive trend. This study explains the specific drivers and interactions that improve port sustainability and competitiveness as countries move from low- to high-income levels of development.

1. Introduction

Competitiveness encompasses a range of institutions, policies, and factors that contribute to an economic system’s prosperity, directly influencing income levels and the overall health of the economy [1]. At the macroeconomic level, a key aspect of competitiveness is the quality of infrastructure, which includes vital components such as roads, railways, and ports. These infrastructures play a crucial role in facilitating trade and enabling economic activities. While national competitiveness covers a broader array of economic indicators and institutional frameworks, port competitiveness focuses explicitly on the operational efficiency and strategic advantages of individual ports within the global supply chain [2]. This distinction is significant: a country can markedly improve its overall economic performance by enhancing port competitiveness. Such enhancements reduce trade costs and improve market access, propelling national economic growth [3].

Global shipping service industry stakeholders use various key port hubs worldwide for global, regional, and national logistic purposes. The host countries and local areas of major ports achieve immense economic benefits and improved competitive potential for local, hinterland, and national economies. At the same time, a decline in the use of a particular port due to a lack of competitiveness relative to changing market conditions can have ruinous socioeconomic and commercial ramifications for ports and their dependent communities. Ports that are more flexible to the requirements of shipping lines and that can complement and add value will become preferred channels for shipping companies and be better positioned to achieve sustainable long-term economic growth.

While developing countries strive to enhance economic performance and move from one level of development to another, they face numerous challenges, and several key factors influence their progress towards sustainable development. However, countries that leverage their ports effectively as part of broader economic strategies are better positioned to achieve sustainable development goals and improve the well-being of their populations over the long term. Thus, the level of national income and availability of ports can be considered vital to competitiveness.

However, the sustainability of port competitiveness (SoPC) includes complex factors that affect ports’ attractiveness and presence for shipping services. Sustainable port competitiveness means balancing the need for growth and efficiency with the responsibility to protect the environment and support social well-being. It refers to the ability of a port to maintain its competitive edge over time while also considering environmental, social, and economic factors [4]. For instance, many shipping lines choose ports that aim to strengthen the level of connectivity and integration with particular trade routes and regions. Other shipping lines choose ports based on their logistic chain solutions to minimize time and economic costs.

Ports are deemed pivotal to an efficient transport system and a well-organized supply chain [5], and the competitiveness of individual ports is formed from a web of infrastructural and service factors, external environmental and local resources, and connectivity with transport and communication networks. The complexity of these factors varies by location and service lines, and improving a port’s competitiveness is a challenging task. While numerous studies have examined port competitiveness in the MENA region, limited consideration has been directed to these transition factors. Accordingly, this study fills this gap.

Similarly, geopolitical risks, such as conflicts and shifting trade policies, disrupt global supply chains. Therefore, the income level of a country plays a significant role in determining how well a port can respond to and recover from geopolitical disruptions. This is due to differences in infrastructure quality, financial resources, technological capabilities, and institutional stability. For instance, high-income countries are better positioned to manage these disruptions due to advanced infrastructure, technology, and financial resources, allowing them to quickly adapt and mitigate impacts. Conversely, low-income countries are more vulnerable, struggling with outdated infrastructure, limited technology, and weaker institutional stability, making adaptation to and recovery from geopolitical disruptions more challenging. Income levels thus shape each region’s ability to respond to geopolitical risks, influencing port competitiveness and resilience.

Following the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic and numerous ongoing conflicts, including in Ukraine and Gaza, new trade routes have developed, such as the India–Middle East–Europe (IME) corridor, which are affecting the dynamics of global trade, shifting trade routes, and influencing the performance and sustainability of many ports. The conflict in Gaza has severely affected the competitiveness and trade of ports in the Red Sea and eastern Mediterranean regions [6,7] and strained the capacity of regional ports, increasing risks for shippers and forcing them to seek alternative routes [8]. These events further complicate the operating environment for ports, requiring collaboration to remain competitive. In addition to disrupting trade, the conflict has highlighted the need for effective risk management strategies to maintain sustainable port competitiveness [9]. Furthermore, the establishment of new trade routes may also shift trade flows and impact port activities, highlighting the need for strategic adjustments in the post-conflict era.

Ports with advanced communication networks and associated technologies are essential to link the demand and supply sides of served markets [10]. The development in the importance of seaports as an enabler of international transportation and supply chains is profound. Continued growth and sustained operations of this magnitude are a major test of latent seaport capacity [11]. Whether legacy seaports are sufficient to accommodate the transport and logistic growth in the coming years is open to question [12,13]. To generate more business, there is intense competition among container ports to maximize their effectiveness and efficiency [14,15,16]. Such competition among ports is crucial for improving economic performance [17,18]. Cutting-edge progress in worldwide trade under globalization has resulted in a manifold increase in the importance of container transport [11].

This development in container transport is associated with numerous technological, logistic, and financial developments that are of increasing magnitude relative to traditional sea transportation. Seaports seem to be the most fundamental and distinguished part of the container transport system, commanding a pivotal nexus at the interface of land and ocean transportation [19]. To achieve a better edge in terms of competitiveness, ports need to improve their efficiency. Most ports worldwide have increasingly sought to incorporate modern technologies and IT systems and equipment within their operations. Though different ports have met with varying degrees of success, they have all generally achieved smoother container shipping processes in the multimodal transport system [18].

Several studies evaluated port competitiveness in terms of port operations, interests, and outcomes according to their needs using qualitative evaluation of experts’ “experiences” and “perceptions,” but few studies have undertaken a detailed examination of how related factors precisely affect the SoPC [20,21,22]. The current research seeks to add to the emerging research in assessing various effects arising from Logistic Performance Index (LPI), Country Competitiveness Index (GCI), and ease of doing business (EoDB) factors on the SoPC, as measured by the country’s level of income and development.

Understanding the drivers of port competitiveness in the MENA region is essential in order to devise and enable strategic business models for countries with different levels of income and development. Consequently, this research aimed to discern the key drivers of port competitiveness affecting countries at different levels of development. The developed constructs applied in this research are novel in the regional context, and were designed in order to (a) examine which factors can enhance SoPC and (b) investigate the relationship of logistic performance with competitiveness and EoDB factors. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was deployed for port competitiveness impact assessment concerning logistic performance, competitiveness, and EoDB factors. Additionally, this study examines how country-level income acts as a moderating variable in these relationships.

Following this introduction, Section 2 reviews related literature, then Section 3 unpacks the developed model and tested hypotheses. Section 4 outlines the methodology deployed for data collection and statistical analysis. Section 5 presents and analyzes the empirical findings and conclusions from hypothesis testing, while Section 6 discusses these outcomes.

2. Literature Review

Ports are vital hubs in global cargo and logistics, contributing immensely to macroeconomic development by interfacing between overseas and domestic producers and consumers and facilitating the flow of capital, products, people, and data. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of port sustainability, including warehousing and logistics in relation to emerging technologies, is necessary to understand their competitiveness and infrastructure requirements [23].

Port competitiveness is essentially defined as the ability of a port to acquire comparative advantages in terms of products, infrastructure, and services [24]. Over recent years, the competitiveness of the global port market has increased greatly, and various instrumental factors have been discerned, with new types of data being utilized to encompass a broader understanding of what port competitiveness can entail [25,26,27,28,29]. Port services and capabilities are affected by internal management and external factors such as national and international political, legislative, and economic considerations, and logistics (e.g., the length of maritime journey from one port to another, and the ports connectedness with inland transportation networks and infrastructure) [30,31]. Internal operational factors include tariffs levied by ports, processing and handling times, and onward and incoming terrestrial, maritime, and air transportation routes, etc. [15,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Other studies have offered various indices for the evaluation of ports’ competitiveness, including a variety of pertinent considerations [38,39,40,41,42,43]. For example, Yeo et al. [36] advocated seven fundamental considerations, encompassing the services and regional centers of ports, interior conditions, logistic efficiency, and the connectivity and convenience of related infrastructure in relation to South Korean and Chinese ports. Ha and Yang [44] identified a hierarchy of six dimensions including 16 particular KPIs for ports’ performance, with 60 total indices of port competitiveness. A systematic review by Parola et al. [43] encompassing major peer-reviewed international journals for the period 1983–2014 identified the main competitiveness drivers of ports as costs, connectivity to the interior, position relative to global markets, operational technology and infrastructure (and their efficiency), maritime and nautical connectivity and accessibility, quality of service, and specific site issues.

Based on the potential instrumentality of such diverse factors and approaches, various studies have proffered differing methodologies to assay global and local competitiveness among ports [44,45,46,47,48,49]. For example, Da Cruz and de Matos Ferreira [50] evaluated the efficiency of maritime ports in Spain and Portugal, finding that cargo amount was not an overwhelming determinant. Chen et al. [47] adopted global positioning system (GPS) traces and maritime open data to effectively monitor port performance. Ren et al. [49] developed a new “multi-attribute decision analysis method” to determine competitiveness at Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore, and they found that the former could outperform the two other ports by leveraging effective market share ratio in the coming decade.

Other studies used the global maritime transport network (GMTN), including Peng et al. [23], who deployed it to analyze three normative transport networks for cargo vessels (bulk carriers, container ships, and oil tankers), leading to the conclusion that while some ports performed well in all studied categories, others varied greatly in terms of their network type. Ducruet [51] analyzed GMTN data from 1977 to 2008, finding that network growth and concentration in relation to key hubs rendered traffic distribution dependent on established ports’ retrenched position.

Conversely, the competitiveness of ports is usually evaluated concerning both local socioeconomic profiles and prevailing geographical conditions, which converge to shape ports’ operational status. For instance, individual wharves were the main focus of traditional port development, but combined ports’ development and the nexus of advanced technologies offer a paradigm shift in flows of capital, technologies, and data, in addition to the more efficient distribution of goods internationally and regionally. Consequently, analyzing port status with market share ratio is important to assess net competitiveness [23]. Munim and Saeed [52] conducted a systematic literature review collected from the Web of Science database investigating articles on how port competitiveness evolved based on maritime literature from 1990 to 2015. The seven main factors identified in their study were port competition, efficiency, institutional transformation, pricing, embeddedness, choice, and cooperation.

Wan et al. [53] developed a model to evaluate the risk factors of maritime supply chains by investigating a real case of a world-leading container shipping company. The study found that the most critical risk factors are the transportation of dangerous products, fluctuations in fuel prices, hard competition, unattractive markets, and fluctuations in exchange rates. A recent analysis of Indonesian ports concluded that port competitiveness significantly relies on government and business support as well as operational performance and that the operational performance of national ports is particularly important in competitiveness [24].

Munim et al. [54] investigated the container market in Bangladesh, due to the uniqueness of its regional context and factors of competitiveness. The study developed a novel approach to evaluate the competitiveness of transshipment ports on seven major dimensions: connectivity, port facility, efficiency, cost factor, policy and management, information systems, and green port management. These various factors are fundamental in contemporary strategic visions and business models for port competitiveness [55] and in macroeconomic development for nations and the global economy in general [56].

The intensification of competition due to globalization, container isolation, the integration of markets, and global flows of labor and capital have fundamentally altered container port governance, operations, and competitiveness [55]. Many researchers have studied the competition of port systems [24,57,58,59,60]. Additionally, the performance of seaports is shaped by profit maximization imperatives in the face of fierce local and global competition [61]. Trade connectivity can be contextualized with a triad of interdependent dimensions: (1) maritime networks (i.e., shipping characteristics and performance at sea); (2) port efficiency per se; and (3) “hinterland connectivity,” referring to the various stakeholders involved in supply chains and local and national economic activities intersecting with ports.

Policies that function effectively for one dimension of port management may be counterproductive in relation to others, and holistic approaches encompassing all dimensions are naturally preferred [62]. Trade connectivity dimensions’ efficiency and growth drivers vary and may span multiple dimensions, but industrial strategies of shipping lines remain the core maritime network drivers. Serious global actors (e.g., Compagnie Générale Maritime, Maersk, and Mediterranean Shipping Company) have been consolidating operational strategies to converge on a “hub-and-spoke” system, oriented toward regions and feeding into secondary Mediterranean ports. Numerous studies were conducted to examine the port competitiveness in the region, highlighting the need for ports to invest in infrastructure, enhance operational efficiency, adopt new technologies, and navigate geopolitical and economic challenges to remain competitive in the global maritime industry [11,63,64].

3. Proposed Model and Hypotheses

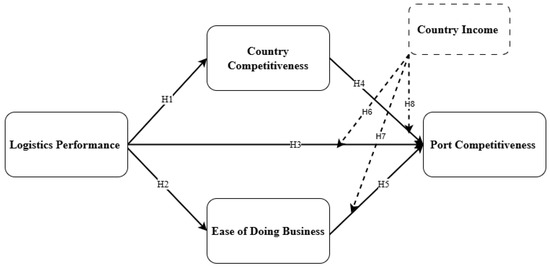

This study constructs a conceptual framework to assess the effects of country-level logistic performance, competitiveness, and EoDB dimensions on the SoPC using country-level income as a moderator. Figure 1 displays the envisioned constructs and hypothesized relationships between them, as discussed below.

Figure 1.

Proposed model.

3.1. Logistic Performance Dimensions

The association between logistic performance and port competitiveness is fundamental, whereby improving a country’s logistic performance enhances the competitiveness of its ports. Logistic performance influences a port’s efficiency, reliability, and ability to handle cargo effectively. Efficient logistics can reduce costs, improve service quality, and attract more shipping lines and cargo, thereby enhancing a port’s overall competitiveness [65,66,67,68]. The logistic performance dimensions used in this study are explained below.

3.1.1. Customs

An extensive number of studies have found a positive relationship between customs procedures as the main components of logistic performance that affect port competitiveness [62,69]. Inefficient customs procedures increase costs and hinder trade and cargo shipments. Although tariffs for maritime containers have been significantly reduced due to the prevalence of larger container ships, the costs of onward (i.e., inland) transportation from ports remain relatively expensive [62]. Most studies examining the relationship between customs procedures and port competitiveness focused on regional contexts without looking into country-specific or other factors, like customs digitalization and integration with global trade networks, which can further improve port competitiveness. In addition, the majority of existing research focuses on high-income countries with already efficient customs systems, while few studies on how to improve customs efficiency have been conducted in low- and middle-income countries [70,71,72,73].

3.1.2. Timeliness

Timeliness refers to the ability to deliver goods or services within a specified period, ensuring that cargo handling, customs clearance, and overall transportation are completed without delays. Timeliness is critical for time-sensitive goods and is a key factor in determining the efficiency and reliability of a port or logistics system [70,74,75]. Therefore, ports that ensure timely handling, processing, and delivery of cargo attract more shippers and cargo flows, leading to higher efficiency, reduced costs, and better customer satisfaction. Delays, on the other hand, reduce a port’s competitive advantage by increasing uncertainty and costs for users [76,77]. Thus, improving timeliness in logistic performance can enhance port competitiveness in different regional and economic contexts.

3.1.3. Tracking and Tracing

Tracking and tracing concern the ability to monitor and follow the progress and location of goods throughout the supply chain from origin to final destination. Studies show that ports that enhance tracking and tracing reduce delays and ensure timely deliveries, which in turn boosts competitiveness [78]. Tracking and tracing enable companies to monitor the movement of goods and ensure timely delivery, improving their competitiveness in the market [79]. Similarly, technologies such as electronic data interchange (EDI) and tracking and tracing systems employed in container terminals are expected to improve port competitiveness [80]. Based on the previous discussions on the links between port competitiveness and logistic performance dimensions, this study hypothesizes that:

H1:

Improving logistic performance dimensions enhances national competitiveness.

H2:

Improving logistic performance dimensions affects a country’s EoDB positively.

H3:

Improving logistic performance dimensions enhances the SoPC.

3.2. Competitiveness Dimensions

Competitiveness can be evaluated at various levels (e.g., countries, governments, organizations, and individuals). In the context of ports, economic performance, management efficiency, and infrastructure are widely recognized as core metrics of national competitiveness [1]. Many studies have historically tied port competitiveness to user perceptions and traditional metrics [81,82]. However, Parola et al. [43] expanded this understanding by incorporating additional factors such as cost, connectivity, location, services, logistics, inland transport, infrastructure, operational efficiency, and service quality.

This study extends the focus to include the broader structural and operational aspects of port competitiveness while highlighting the importance of professionalization of port officers [83]. Enhancing professional skills in areas like green port management can lead to gains in operational efficiency and sustainability, contributing to both short- and long-term competitiveness. The chosen competitiveness dimensions for this study reflect an integrated approach to the SoPC. Below, we provide a detailed explanation of these dimensions and their specific relevance to port competitiveness.

3.2.1. Institutions

Strong institutions provide the regulatory and governance framework necessary for stable and predictable business operations, which directly influence the SoPC. When governance is effective, it attracts foreign and domestic investment, enhances operational transparency, and ensures compliance with international standards. For example, a well-governed port with clear regulations and secure property rights facilitates smoother transactions, faster logistic processes, and better coordination among stakeholders [62]. Additionally, the institutional environment affects how other factors—like connectivity and location—are leveraged to improve port competitiveness. Effective institutions can therefore amplify the impact of infrastructural investments or mitigate risks associated with geographical location. Empirical evidence has developed and validated scales for the measurement of the quality of institutions [73,84]. However, other studies have examined the link between institutions and port competitiveness separately [85,86].

Notwithstanding the important developments offered by reviewed studies, more examination is needed concerning the impacts of institutions on port competitiveness in different regions and contexts. There is limited research on how government policies, institutional quality, and regulatory environments interact with other factors to influence port competitiveness.

3.2.2. Infrastructure

Infrastructure is a cornerstone of port competitiveness, influencing both operational efficiency and long-term strategic viability. The ongoing development of port facilities, technology, and connectivity affects port performance and competitiveness [4]. The quality of infrastructure affects transport costs, trade efficiency, and overall SoPC. Investments in inland terminals, logistic zones, and rail networks, as noted by [62], can expand a port’s influence beyond its traditional hinterland. However, infrastructure is only one aspect; geographic location and connectivity also play crucial roles. Ports situated in strategic locations with strong inland and coastal links have a competitive advantage, underscoring the need to consider location as a moderating factor in infrastructure’s contribution to the SoPC. High quality and functional infrastructure are essential for port competitiveness. However, such investment is never risk-free, and even the best ports in terms of infrastructure are vulnerable to market and political externalities [87]. Other factors affect port efficiency, which is closely linked to infrastructure quality that reduces transport costs and enhances trade [70].

3.2.3. Macroeconomic Environment

A country’s macroeconomic environment is intricately linked to its ports’ performance and competitiveness. Factors like inflation, exchange rates, and economic stability influence trade flows, investment, and thus the SoPC. Moreover, the macroeconomic environment interacts with social factors like education and income disparity. For example, a skilled labor force can enhance operational performance and support the adoption of new technologies, further strengthening the SoPC. Conversely, income disparity can limit access to skilled labor or create social challenges, potentially weakening the macroeconomic foundation for port competitiveness. Lirn et al. [88] demonstrated how a stable macroeconomic context can increase a port’s attractiveness. However, the influence of these factors is moderated by elements like education levels, which affect the skill quality of the labor force in port regions, and income disparity, which can impact the overall socioeconomic stability of port operations. This study highlights the need to explore these connections in different economic contexts, particularly in developing regions where volatility may alter these dynamics [89,90].

3.2.4. Market Size and Efficiency

The relationship between market size and port competitiveness has been demonstrated in large markets, mainly in developing countries. Market size is closely linked to a port’s geographical location and connectivity: ports situated near major trade routes or large consumer markets have a natural advantage in attracting cargo. Studies show that larger markets lead to higher accessibility to trade networks, container throughput, and better utilization of port infrastructure [91,92,93]. Arvis et al. [62] adumbrated seven indicators instrumental in ports’ market share, the most significant of which were interconnectivity with the inland and destinations, road distance, and volume of throughput. Political stability, cultural considerations, and environmental policies also play a role in determining market size and efficiency [94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101]. Alongside such universal factors, a new trend of environmental protection has emerged, such as regulations on environmental issues and consumer and regulatory requests that logistics should be increasingly green. However, most related studies that provided criteria for port competitiveness did not systematically categorize them. For instance, Murphy et al. [102] and Wiegmans et al. [99] classified different groups of factors, but they did not prioritize, measure, or compare them. Based on the previous discussions on the link between port competitiveness and competitiveness dimensions, this study hypothesizes that:

H4:

Improving national competitiveness positively enhances the SoPC and overall economic performance.

3.3. Ease of Doing Business Dimensions

EoDB refers to a set of indicators developed by the World Bank to measure how conducive a regulatory environment is for business operations in different countries [73]. EoDB dimensions such as trading across borders, enforcing contracts, protecting minority investors, and dealing with construction permits are directly linked to port competitiveness, because efficient regulatory and operational environments in a country make it easier for ports to facilitate trade. According to the World Bank [73], EoDB tends to be more efficient in handling cargo, leading to increased competitiveness in the global logistics network. The EoDB dimensions used in this study are explained below.

3.3.1. Protecting Minority Investors

Ports that ensure good corporate governance and protect minority investors are seen as more stable and trustworthy, which can attract global shipping companies [103], thus protecting minority investors to attract investment, fostering good corporate governance, and enhancing port competitiveness [73].

3.3.2. Trading Across Borders

The ease of trading across borders influences port competitiveness significantly, and ports with efficient logistics and streamlined trading procedures facilitate international trade to compete for global cargo flows [104]. On the other hand, enhanced customs procedures and reduced trade costs attract international shipping lines and traders, which enhances their global competitiveness.

3.3.3. Enforcing Contracts

Enforcing contracts ensures that disputes related to port services, contracts with shipping companies, or logistic operators are resolved promptly, maintaining port reliability by investors and shipping companies. Ports with efficient operations and high scores in enforcing contracts are better to handle larger cargo volumes, improve shipping schedules, and reduce costs for shippers [105].

3.3.4. Dealing with Construction Permits

The dimension of dealing with construction permits has direct impacts on port competitiveness by influencing the speed, cost, and quality of infrastructure development. This dimension is linked with regulatory ecosystems and shows how easy it is for investors to start and operate a business in different countries. Building on previous discussions, ports operating in countries with streamlined regulations, efficient customs procedures, and supportive business environments are more competitive globally. The ease with which businesses can operate and trade affects how efficiently ports handle cargo and serve international markets. Consequently, this study posits that:

H5:

EoDB enhances the SoPC and overall economic performance.

3.4. National Income Level

The relationship between national income and port competitiveness has been explored through various theoretical lenses, demonstrating how income levels can influence LPI, GCI, and EoDB in relation to port efficiency. Previous studies show that the effects of income levels on port competitiveness vary significantly between low-income and high-income countries, influencing their investment capacity, workforce skills, technological adoption, and strategic focus, with high-income countries emphasizing advanced infrastructure and innovation, while low-income countries prioritize cost-effective, foundational improvements [106,107]. Generally, higher national income levels are associated with increased investment in infrastructure, enhancing port operations and services, and improving competitiveness [107,108]. Research indicates that as national income rises, ports are better positioned to optimize their logistic capabilities and operational efficiencies, contributing to an advantageous competitive stance in global trade [72].

This supports the notion that income levels play a positive role in moderating the connection between a nation’s overall competitiveness and its port competitiveness, as wealthier countries can invest in advanced technologies and facilities that enhance port services while also lowering operational costs. On the other hand, some experts suggest that the advantages of rising national income may not necessarily lead to improved port competitiveness across the board [109]. In lower-income countries, for example, even when national income increases, challenges such as bureaucratic inefficiencies and insufficient regulatory frameworks can hinder the effective use of resources intended for port development [110,111]. Therefore, while higher national income has the potential to improve port infrastructure and services, the realization of these benefits is critically dependent on the wider economic environment and the effectiveness of governance structures. Hence, this study hypothesizes that:

H6:

Income level moderates the relationship between logistic performance and port competitiveness.

H7:

Income level moderates the relationship between EoDB and port competitiveness.

H8:

Income level positively moderates the relationship between a country’s competitiveness and port competitiveness.

3.5. Proposed Model

This study analyzes “port competitiveness” in multiple dimensions, arguing that the SoPC and the drivers thereof are significantly determined by notable developments in the maritime industry. Thus, building on previous literature, the current study posits that LPI, GCI, and EoDB are a function of interrelationships between the study constructs. Figure 1 shows the expected relationships between these factors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

This study utilized SEM with Smart PLS 4 to assess the effects of country-level competitiveness, logistic performance, and EoDB on the SoPC. The model was developed by integrating various factors of competitiveness, logistics, and EoDB factors to test their collective and individual influences on port competitiveness across 17 countries in the MENA region, classified according to their income level as per the World Bank classification: Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malta, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. These countries were chosen based on their level of income according to the World Bank classification and their trade routes’ connectivity, connections with international markets, and port availability. This comprehensive approach enables an in-depth assessment of how different income levels interact with critical logistic and economic factors, thus offering valuable insights into port competitiveness across varied economic landscapes. The study also included path analysis corresponding to H1–H8. These relationships suggest that increasing country competitiveness, logistic performance, and EoDB factors increase the SoPC. While SEM is considered a confirmatory technique, it also extends the possibility of relationships among the latent variables and encompasses two components: a measurement model (essentially CFA) and a structural model [112]. The applicability of port competitiveness factors to this study was investigated by applying CFA to test the hypotheses.

4.2. Measurement Items

A 14-item scale was developed by the researchers, derived from the World Economic Forum (WEF), GCI, LPI, and EoDB. The sustainability of the port competitiveness scale was measured using the weighted average of three different indices published by WEF, namely, the linear shipping connectivity index (with maximum value in 2004 = 100), quality of port infrastructure (with scores ranging from 1 = extremely underdeveloped to 7 = well developed and efficient by international standards), and international shipments. Country competitiveness uses a five-item scale derived from GCI. Logistic performance uses a five-item scale derived from LPI. EoDB uses a three-item scale derived from EoDB. All indicators were standardized on a five-point scale to be consistent with the study context. The most recently available data were used in this study, encompassing the years 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2022. The selected period ensured comprehensive and consistent data across all key factors influencing port competitiveness, including logistic performance, economic indicators, infrastructure development, and geopolitical impacts, encompassing a period marked by significant geopolitical events and conflicts in the MENA region.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) involved item-to-total correlations for 14 items, with all items showing satisfactory correlations. Subsequently, employing a principal component and varimax rotation resulted in the retention of 14 items and the identification of 4 factors suitable for EFA. The results for the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measurement (0.708) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (reaching significance at the 0.001 level) (as shown in Table 1) confirmed that the data exhibited significant inherent correlations for EFA. The scree plot indicated a four-factor solution with 14 items as the optimal solution, accounting for 86.14% of the total variance in the factor pattern.

Table 1.

KMO and Bartlett’s test.

Table 2 shows that the reliability testing of the constructs utilizing Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR) revealed that all constructs surpassed the 0.70 threshold recommended by Sarstedt et al. [113]. In addition, our assessment of convergent validity by determining AVE values revealed that all values exceeded the 0.50 threshold recommended by Henseler et al. [114].

Table 2.

Factor loadings.

Additionally, we conducted Fornell–Larcker and heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio tests to assess discriminant validity. The HTMT ratio results showed acceptable values below the 0.80 threshold, as shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker and heterotrait–monotrait ratio tests.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity regarding Fornell–Larcker criterion.

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

The structural model was calculated using the bootstrapping technique, and the hypothesized relationships were developed based on theoretical and empirical research. Table 5 shows the results of the hypothesis testing: it shows that the model fit is significant, with an SRMR value of 0.035. Additionally, the determination coefficient (R2) value is greater than 0.25 [115]. These findings indicate that 50.4% of the variance in the SoPC was explained by country competitiveness, country logistic performance, and EoDB. Furthermore, the Q2 value was higher than zero, demonstrating the significance and predictive relevance of the study model [116].

Table 5.

Model fit.

5. Results

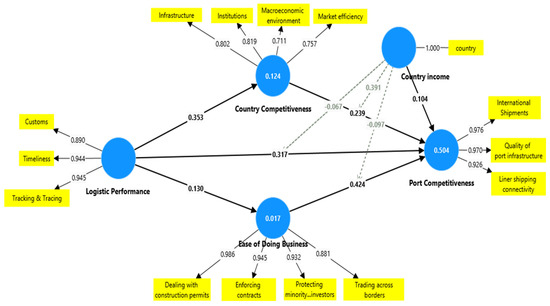

The findings in Figure 2 show that country logistic performance has a significant and positive impact on the following factors: country competitiveness (β = 0.353, t = 4.485, p ≤ 0.000), EoDB (β = 0.130, t = 2.780, p ≤ 0.000), and SoPC (β = 0.317, t = 3.485, p ≤ 0.001). Concerning H4, the results indicate that country competitiveness has a positive and significant impact on the SoPC (β = 0.239, t = 2.146, p ≤ 0.05). EoDB also has a positive and significant impact on port competitiveness (β = 0.424, t = 4.042, and p ≤ 0.001). Thus, we accepted the direct relationships of H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 (Table 6).

Figure 2.

Proposed model.

Table 6.

Results of the direct hypotheses.

In addition, the study explored the influence of national income level on the relationship between independent variables (country logistic performance, country competitiveness, and EoDB) and the SoPC. The findings revealed that national income level moderates the relationship between country competitiveness and port competitiveness. It showed a positive and significant effect with a coefficient of 0.391, a t-value of 4.075, and a p-value of less than 0.05. However, the study found that the moderation role of national income level on the impact of the country’s logistic performance and EoDB on port competitiveness was not significant, leading to the lack of support for hypotheses H6 and H8 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Results of the moderation hypotheses.

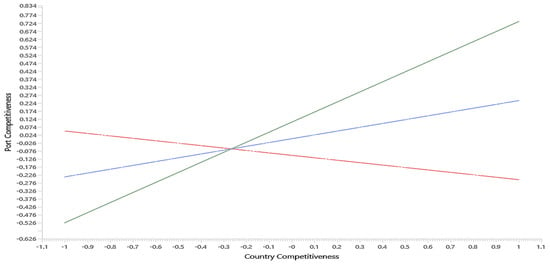

Figure 3 demonstrates the interaction between country income level and country competitiveness and the relationship between country competitiveness and port competitiveness. The results show that in high-income countries (green line), an increase in country competitiveness notably improves port competitiveness. In contrast, in low-income countries (red line), higher country competitiveness appears to reduce port competitiveness. This could be caused by resource allocations toward sectors perceived to be more directly tied to economic growth, such as urban development or manufacturing, rather than toward improving port infrastructure. For countries with average income (blue line), the association is relatively neutral, with a small positive trend. These findings indicate that country competitiveness is influenced by national income in terms of the impact it exerts on the SoPC.

Figure 3.

The moderating role of country income level.

6. Discussion

A country’s income level plays a significant role in determining how its competitiveness affects the SoPC. It can also show how ports in different regions can respond and recover from geopolitical disruptions and risks. The ability of ports to respond to these risks is mainly determined by the level of port competitiveness, which is due to differences in infrastructure quality, financial resources, technological capabilities, and institutional stability. The capabilities of ports in the MENA region, with the ongoing challenges posed by the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza along with the evolving dynamics of the IME corridor, underscore the need for ports to continuously upgrade their infrastructure, integrate advanced technologies, and develop tailored strategies to maintain their global competitiveness.

This study’s findings confirm that the SoPC is closely linked with the country’s logistic performance, competitiveness, and EoDB, but the associated effects vary significantly across countries by income. In low- and high-income countries, an increase in country competitiveness reduces or improves the SoPC (respectively), while in middle-income countries, the association is relatively neutral (with a small non-significant positive trend). Moreover, a country’s logistic performance has a significant and positive impact on the EoDB and on the country’s competitiveness. An important finding for low-income countries that affects port competitiveness is that resource allocation is typically skewed toward sectors perceived to be more directly tied to economic growth than ports. The findings suggest that low-income countries should adopt a balanced approach to economic development, ensuring that gains in national competitiveness are aligned with targeted investments in port infrastructure and capabilities for long-term economic development. This requires prioritizing port modernization, enhancing logistic networks, and providing training for port staff to avoid performance decline. It also highlights the need for supportive government policies that facilitate investments in maritime infrastructure, and the importance of international partnerships and capacity-building programs aimed specifically at ports in developing economies.

These findings must be interpreted in light of countries at all different income levels facing global competition, as well as unequal challenges related to infrastructure, technology, green practices, and financing [117]. In addition to disrupting trade, conflicts have highlighted the need for effective risk management strategies to maintain port competitiveness [9]. Furthermore, the establishment of new trade routes may also shift trade flows and impact port activities, highlighting the need for strategic adjustments in the post-war era. Low-income countries can benefit from international support and cost-efficiency-focused strategies. Likewise, middle-income countries must balance rapid growth with technological and environmental considerations, while high-income countries focus on innovation and maintaining advanced infrastructure.

By improving port infrastructure and operations, countries can enhance their logistic performance, overall competitiveness, and business environment. Tailored strategies that consider the economic context of low-, middle-, and high-income countries are essential for optimizing port performance and fostering sustainable economic growth. For low-income countries, enhancing port infrastructure and logistic efficiency can improve the SoPC. For middle-income countries, balancing growth with sustainable practices can enhance the SoPC. In addition, investment in modernizing ports and improving regulatory environments can lead to better performance in logistics, competitiveness, and business operations. For high-income countries, continuous innovation and infrastructure maintenance are key to sustaining port competitiveness. High-income countries must focus on integrating advanced technologies and maintaining regulatory efficiency to uphold their competitive edge. Therefore, high-income countries must continuously invest in maintaining and upgrading their advanced port infrastructure to stay competitive. This includes addressing aging facilities and integrating new technologies. As a result, port managers operating in countries with different income levels must prioritize strategic investments in infrastructure, professional training, and sustainable practices to improve efficiency and competitiveness. They can strengthen operational performance by adopting advanced technologies and green approaches and mitigate risks while fostering stronger partnerships.

By focusing on long-term growth, managers can align investments with industry trends, benchmark performance, and introduce innovative services to ensure continued success in a competitive environment. This study contributes to the literature by showing how ports in different regions and income levels respond to changes in logistic performance, competitiveness, and EoDB dimensions over time. The main limitations of this study are related to the availability of data over recent years and the inclusion of all dimensions in the model. Future studies should focus on comparative case studies from low-, middle-, and high-income countries to examine how these dimensions enhance the sustainability of ports’ competitiveness. Furthermore, other dimensions such as insolvency, credit, and improved technology might be included in the model to increase reliability.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.A.H.; validation, G.A.S.; formal analysis, O.M.B.; investigation, M.A.H.; data curation, O.M.B.; writing—original draft, M.F.M.; writing—review and editing, M.F.M.; review, R.K.; visualization, G.A.S.; supervision, M.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

World Economic Forum (WEF). https://www.weforum.org/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cho, H.; Lee, J. Does transportation size matter for competitiveness in the logistics industry? The cases of maritime and air transportation. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2020, 36, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, K.; Song, D.W. Port supply chain integration and sustainability: A resource-based view. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 504–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.A. Does Trade Reform Promote Economic Growth? A Review of Recent Evidence. World Bank Research Observer, Working Paper 25927. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w25927 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Notteboom, T.; Rodrigue, J.P. Port regionalization: A new conceptual framework. Marit. Policy Manag. 2005, 32, 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Meersman, H.; Van de Voorde, E. Port management, operation, and competition: A focus on North Europe. In The Handbook of Maritime Economics and Business, 2nd ed.; Grammenos, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 921–936. ISBN 978-1-8431-1880-0. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed, M.; Farouk, A. Geopolitical tensions and their impact on maritime trade in the Middle East: A case study of port resilience. J. Glob. Trade Logist. 2023, 58, 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Lin, Y. The impact of geopolitical conflicts on port competitiveness and global trade routes: A focus on the Middle East. J. Marit. Econ. 2023, 45, 245–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Saleh, M. The influence of regional conflicts on maritime logistics and trade competitiveness: An analysis of Middle Eastern ports. Int. J. Shipp. Trade 2023, 12, 321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Kumar, V. The effects of geopolitical conflicts on global trade routes and port operations: A focus on South Asia and the Middle East. J. Glob. Trade Marit. Stud. 2023, 27, 200–217. [Google Scholar]

- Schøyen, H.; Odeck, J. Comparing the productivity of Norwegian and some Nordic and UK container ports—An application of Malmquist productivity index. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2017, 9, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.S.; Khan, R.U.; Mustafa, T. Technical efficiency comparison of container ports in Asian and Middle East region using DEA. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2021, 37, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeck, J.; Bråthen, S. A meta-analysis of DEA and SFA studies of the technical efficiency of seaports: A comparison of fixed and random-effects regression models. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2012, 46, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Transport Forum. Transport Outlook 2023; International Transport Forum: Paris, France, 2023; ISBN 978-9-2821-6726-7. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M.; Liu, L.; Gao, F. Post-entry container port capacity expansion. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2012, 46, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, A.C.L.; Zhang, A.; Cheung, W. Port competitiveness from the users’ perspective: An analysis of major container ports in China and its neighbouring countries. Res. Transp. Econ. 2012, 35, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Port Technology International. 2038: Future Visions. Available online: https://www.porttechnology.org/news/2038-future-visions/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Cullinane, K.; Wang, T.F.; Song, D.W.; Ji, P. The technical efficiency of container ports: Comparing data envelopment analysis and stochastic frontier analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2006, 40, 354–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Mangan, J.; Lalwani, C. Comparing port performance: Western European versus eastern Asian ports. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.L.; Yu, M.M.; Hsieh, W.F. Evaluating the efficiency of major container shipping companies: A framework of dynamic network DEA with shared inputs. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 117, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, J.P.; Notteboom, T.E. The Role of Ports in the Global Supply Chain. Marit. Policy Manag. 2013, 40, 420–431. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.F.; Cullinane, K.P.B.; Song, D.W. Industrial concentration in container ports. In Proceedings of the International Association of Maritime Economists Annual Conference, Izmir, Turkey, 30 June–2 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, G.T.; Roe, M.; Dinwoodie, J. Measuring the competitiveness of container ports: Logisticians’ perspectives. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Yang, Y.; Lu, F.; Cheng, S.; Mou, N.; Yang, R. Modelling the competitiveness of the ports along the Maritime Silk Road with big data. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, S.; Taufik, A.A.; Hui, F.K.P. Exploring key variables of port competitiveness: Evidence from Indonesian ports. Compet. Rev. 2020, 30, 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, W.Y.; Lam, J.S.; Notteboom, T. Developments in container port competition in East Asia. Transp. Rev. 2006, 26, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.; Dowall, D.E.; Song, D.W. Evaluating impacts of institutional reforms on port efficiency changes: Ownership, corporate structure, and total factor productivity changes of world container ports. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2010, 46, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichou, K. An empirical study of the impacts of operating and market conditions on container-port efficiency and benchmarking. Res. Transp. Econ. 2013, 42, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, D.N.; Chang, Y.T.; Lam, J.S.L.; Desplebin, O.; Dholakia, N.; Al-Wugayan, A. An empirical test of the balanced theory of port competitiveness. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, K.X. Port competition with accessibility and congestion: A theoretical framework and literature review on empirical studies. Marit. Policy Manag. 2018, 45, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guridi, M.; Perea, J. The impact of global crises on port operations and trade efficiency: A case study of Middle Eastern ports. J. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2023, 29, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Chang, H. Port resilience and competitiveness in the face of global disruptions: Insights from the Middle East and Asia. J. Marit. Trade Logist. 2024, 31, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, A.C.L.; Zhang, A.; Cheung, W. Foreign participation and competition: A way to improve the container port efficiency in China? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 49, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Alemán, A.; Trujillo, L.; Cullinane, K.P. Time at ports in short sea shipping: When timing is crucial. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2014, 16, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, G.F.; Cariou, P. The impact of competition on container port (in) efficiency. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 78, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, B.; Hernández, R.; Rodríguez-Déniz, H. Container port competitiveness and connectivity: The Canary Islands main ports case. Transp. Policy 2015, 38, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.J.; Woo, S.H. Liner shipping networks, port characteristics and the impact on port performance. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2017, 19, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Moya, J.; Feo Valero, M. Port choice in container market: A literature review. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, G.T.; Roe, M.; Dinwoodie, J. Evaluating the competitiveness of container ports in Korea and China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhieh, L.; Mdanat, M.; Al-Shboul, M.; Samawi, G. Transportation landed cost as a barrier to intra-regional trade. J. Borderl. Stud. 2019, 34, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.T.; Hu, K.C. Evaluation of the service quality of container ports by importance-performance analysis. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2012, 4, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, G.T.; Ng, A.K.; Lee, P.T.W.; Yang, Z. Modelling port choice in an uncertain environment. Marit. Policy Manag. 2014, 41, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Lu, J. A study on the effects of network centrality and efficiency on the throughput of Korean and Chinese container ports. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Transportation Engineering, Dalian, China, 26–27 September 2015; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2015; pp. 760–769, ISBN 978-0-7844-7938-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, F.; Risitano, M.; Ferretti, M.; Panetti, E. The drivers of port competitiveness: A critical review. Transp. Rev. 2016, 37, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.H.; Yang, Z. Comparative analysis of port performance indicators: Independency and interdependency. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onut, S.; Tuzkaya, U.R.; Torun, E. Selecting container port via a fuzzy ANP-based approach: A case study in the Marmara Region, Turkey. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L. Tactical berth allocation under uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 247, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, T. Port cargo throughput forecasting based on combination model. In Proceedings of the 2016 Joint International Information Technology, Mechanical and Electronic Engineering Conference, Xi’an, China, 4–5 October 2016; Atlantis Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 148–154, ISBN 978-94-6252-234-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.G.; Yeo, G.T. Analysis of the air transport network characteristics of major airports. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2017, 33, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Lützen, M.; Rasmussen, H.B. Identification of success factors for green shipping with measurement of greenness based on ANP and ISM. In Multi-Criteria Decision Making in Maritime Studies and Logistics: Applications and Cases; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 260. [Google Scholar]

- Da Cruz, M.R.P.; de Matos Ferreira, J.J. Evaluating Iberian seaport competitiveness using an alternative DEA approach. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2016, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducruet, C. Multilayer dynamics of complex spatial networks: The case of global maritime flows (1977–2008). J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 60, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munim, Z.H.; Saeed, N. Seaport competitiveness research: The past, present and future. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2019, 11, 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Yan, X.; Zhang, D.; Qu, Z.; Yang, Z. An advanced fuzzy Bayesian-based FMEA approach for assessing maritime supply chain risks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 125, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munim, Z.H.; Duru, O.; Ng, A.K. Transhipment port’s competitiveness forecasting using analytic network process modelling. Transp. Policy 2022, 124, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.L.; Yeo, G.T. A competitive strategic position analysis of major container ports in Southeast Asia. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2017, 33, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, D. Empirical analysis of the worldwide maritime transportation network. Phys. A 2009, 388, 2061–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.H. Strategic positioning analysis on the Asian container ports. J. Korean Assoc. Shipp. Stud. 2002, 34, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, J.S.L.; Yap, W.Y. Competition for transhipment containers by major ports in Southeast Asia: Slot capacity analysis. Marit. Policy Manag. 2008, 35, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notteboom, T.; Yap, W.Y. Port competition and competitiveness. In The Blackwell Companion to Maritime Economics; Talley, W.K., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 549–570. ISBN 978-1-444-33024-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer, P.J. Asian-Pacific Rim Logistics: Global Context and Local Policies; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-84720-628-2. [Google Scholar]

- Da Cruz, M.R.P. Competitiveness and Strategic Positioning of Seaports: The Case of Iberian Seaports. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, 2012. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10400.6/2633 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Arvis, J.F.; Vesin, V.; Carruthers, R.; Ducruet, C. Maritime Networks, Port Efficiency, and Hinterland Connectivity in the Mediterranean; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4648-1274-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almawsheki, E.S.; Shah, M.Z. Technical efficiency analysis of container terminals in the Middle Eastern region. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2015, 31, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutin, N.; Nguyen, T.T.; Vallée, T. Relative efficiencies of ASEAN container ports based on data envelopment analysis. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2017, 33, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notteboom, T.; Rodrigue, J.P. The future of containerization: Perspectives from maritime and inland freight distribution. GeoJournal 2009, 74, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsmeier, G.; Sánchez, R.J. The relevance of international transport costs on food prices: Endogenous and exogenous effects. Res. Transp. Econ. 2009, 25, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, W.Y.; Lam, J.S.L. 80 million-twenty-foot-equivalent-unit container port? Sustainability issues in port and hinterland development. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 46, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Arvis, J.F.; Mustra, M.A.; Ojala, L.; Shepherd, B.; Saslavsky, D. Connecting to Compete 2010: Trade Logistics in the Global Economy. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/06/28/connecting-to-compete-2016-trade-logistics-in-the-global-economy (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Hoffman, J.; Wilmsmeier, G.; Venus Lun, Y.H. Connecting the world through global shipping networks. J. Shipp. Trade 2017, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, X.; Dollar, D.; Micco, A. Port efficiency, maritime transport costs, and bilateral trade. J. Dev. Econ. 2004, 75, 417–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongzon, J.L. Port choice and freight forwarders. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2009, 45, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munim, Z.H.; Schramm, H.J. The impact of port infrastructure and logistics performance on economic growth: The mediating role of seaborne trade. J. Shipp. Trade 2018, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business Regulation in 190 Economies; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-4648-1441-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zarzoso, I.; Márquez-Ramos, L. The impact of trade facilitation on sectoral trade. B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2008, 8, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Arvis, J.F.; Wiederer, C.; Raj, A.; Dairabayeva, K.; Kiiski, T. Connecting to Compete 2018: Trade Logistics in the Global Economy; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/29971 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Merk, O.; Dang, T. Efficiency of World Ports in Container and Bulk Cargo (Oil, Coal, and Grain). In OECD Report on Port Competitiveness; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, R.; Martí, L.; García, L. Logistics performance and export competitiveness: European experience. Empirica 2014, 41, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.; van Hoek, R. Logistics Management and Strategy: Competing Through the Supply Chain; Pearson Education: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-2737-1276-3. [Google Scholar]

- Banomyong, R.; Supatn, N. Supply chain assessment tool development in Thailand: An SME perspective. Int. J. Proc. Manag. 2011, 4, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, G.; Maugeri, S.; Panetti, E.; Ferretti, M. Port labour, competitiveness and drivers of change in the Mediterranean Sea: A conceptual framework. Prof. Plan. Control. 2019, 30, 1102–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.; Coronado, D.; Mar Cerban, M. Port competitiveness in container traffic from an internal point of view: The experience of the Port of Algeciras Bay. Marit. Policy Manag. 2007, 34, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.R.; Schellinck, T.; Pallis, A.A. A systematic approach for evaluating port effectiveness. Marit. Policy Manag. 2011, 38, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, K.K.; Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Shaheen, M.M.A. Green port management practices for sustainable port operations: A multi method study of Asian ports. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 50, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastrorillo, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5430. 2020. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/630421468336563314/pdf/WPS5430.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Hsu, C.C.; Hu, H.-C. The impact of institutional factors on port competitiveness: Evidence from Asian ports. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 59, 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Pallis, A.A.; Vergara, S. Port reform and the role of institutional frameworks in the port industry. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P.N.; Woo, S.H. Port connectivity and competition among container ports in Southeast Asia based on Social Network Analysis and TOPSIS. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 49, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lirn, T.C.; Thanopoulou, H.A.; Beynon, M.J.; Beresford, A.K.C. An application of AHP on transshipment port selection: A global perspective. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2004, 6, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonigen, B.A.; Wilson, W.W. Port efficiency and trade flows. Rev. Int. Econ. 2008, 16, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notteboom, T.E. Economic Analysis of the European Seaport System: Report Commissioned by the European Sea Ports Organisation (ESPO). Available online: https://www.espo.be/media/espopublications/ITMMAEconomicAnalysisoftheEuropeanPortSystem2009.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Sanchez, R.J.; Hoffmann, J.; Micco, A.; Pizzolitto, G.V.; Sgut, M.; Wilmsmeier, G. Port efficiency and international trade: Port efficiency as a determinant of maritime transport costs. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2003, 5, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, K.; Song, D.W. Estimating the relative efficiency of European container ports: A stochastic frontier analysis. Res. Transp. Econ. 2006, 16, 85–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, K. Port competitiveness in a changing environment: A case of north Europe. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2010, 44, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, H.J. Structural Changes in International Trade and Transport Markets: The Importance of Logistics. Ports Harb. 1990, 35, 9. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:151205163 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Lirn, T.C.; Thanopoulou, H.A.; Beresford, A.K. Transhipment port selection and decision-making behaviour: Analysing the Taiwanese case. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2003, 6, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.J.; Zhou, Z.; Magni, K.; Christoforides, C.; Rappsilber, J.; Mann, M.; Reed, R. Pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA export linked by direct interactions between UAP56 and Aly. Nature 2001, 413, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongzon, J. Determinants of competitiveness in logistics: Implications for the ASEAN region. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2007, 9, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Transport. National Policy Statement for Ports: Presented to Parliament Pursuant to Section 5(9) of the Planning Act 2008. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/national-policy-statement-for-ports--4 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Wiegmans, B.W.; Hoest, A.V.D.; Notteboom, T.E. Port and terminal selection by deep-sea container operators. Marit. Policy Manag. 2008, 35, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comtois, C.; Dong, J. Port competition in the Yangtze River delta. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2007, 48, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenblat, C. Les Villes Portuaires en Europe: Analyse Comparative; Université de Lausanne: Montpellier, France; CNRS: Paris, France, 2004; Available online: https://www.mgm.fr/PUB/IRSIT.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Murphy, P.R.; Dalenberg, D.R.; Daley, J.M. Analyzing international water transportation: The perspectives of large US industrial corporations. J. Bus. Logist. 1991, 12, 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Investor protection and corporate governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 58, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinek, J.; Sourdin, P. To what extent are high-quality logistics services trade facilitating? In OECD Trade Policy Working Papers; No. 108; OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merk, O. The Competitiveness of Global Port-Cities: Synthesis Report. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/directorates/centre-for-entrepreneurship-smes-regions-and-cities.html (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Lee, S.W.; Song, J.M.; Park, S.J.; Sohn, B.R. A study on the comparative analysis of port competitiveness using AHP. KMI Int. J. Marit. Aff. Fish. 2014, 6, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilaka, R.; Jayawardhana, C.; Embogama, N.; Jayasooriya, S.; Karunarathna, N.; Gamage, T.; Kuruppu, N. Gross domestic product and logistics performance index drive the world trade: A study based on all continents. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwarakish, G.S.; Salim, A.M. Review on the role of ports in the development of a nation. Aquat. Procedia 2015, 4, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, 2nd ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-06-8484-146-5. [Google Scholar]

- Koeswayo, P.S.; Handoyo, S.; Abdul Hasyir, D. Investigating the relationship between public governance and the Corruption Perception Index. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2342513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainer, L.; Daels, M. What makes local planning effective in a megacity? The overlapping agendas and scale inconsistencies in developing Buenos Aires’ affordable land markets. Plan. Theory Pract. 2024, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet—Retrospective observations and recent advances. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2023, 31, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Research Methods in Applied Linguistics (Vol. 1, Issue 3); Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80519-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K. Mediation analysis, categorical moderation analysis, and higher-order constructs modeling in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): A B2B Example using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2016, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, E.; Mdanat, M.; Alsoud, A. Sustainability of Fiscal and Monetary Policies under Fixed Exchange Rate Regime in Jordan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).