Abstract

Marine sponges have historically been targeted for different purposes, mainly as bath sponges or more recently as a source of bioactive metabolites. However, their use as ornamental species for aquariology is less thoroughly studied. In light of the rise in the importance of sustainable production systems and to valorize the biomass obtained from them, this work assessed the market potential of sustainably reared marine sponges in Italian aquariology. Information was obtained by means of an anonymous questionnaire distributed using social media and printed QR codes targeting Italian aquariophily groups. A total of 101 people from almost all Italian regions participated in the study. Among the people with marine aquariums, almost two-thirds had marine sponges (obtained mainly from fishing discards and trusted shops), and those without them stated that there was no availability in the specialized shops. However, when people were asked about a hypothetical change in purchase intention or frequency of these invertebrates, 68.3% of the respondents showed a positive attitude toward the idea of acquisition. This study constitutes the first preliminary assessment of the valorization potential for sustainably cultivated sponges as ornamental species, which shows a promising prospective in the Italian aquariology sector.

1. Introduction

Since Egyptian civilization, marine sponges have been harvested and used by humans [1]. The method of harvesting the biomass and the commercial interest in it have changed over the decades (i.e., from collection to cultivation and from cosmetics to production of bioactive secondary metabolites [2]); however, these marine invertebrates still persist in the economy of some countries as an alternative source of income, from “bath sponges” in the Mediterranean (e.g., Greece, Italy, Croatia, Cyprus or Tunisia) and underdeveloped countries (e.g., Micronesia or Zanzibar) to ornamental species for aquariology, especially in the USA (reviewed in [3]).

Although there is an absence of specific regulations on ornamental invertebrate species trade except those subjected to a protection regime (e.g., European Habitat Directive, CITES), the exploitation of wild stocks to support this business sector is not environmentally sustainable or ethical. This reason has increased interest in developing pilot production systems aiming to reduce harvesting pressure on natural stocks and to provide the amount of biomass required for various other purposes. Thus, since the end of the 18th century [4], numerous attempts have been made to cultivate sponges and reduce costs.

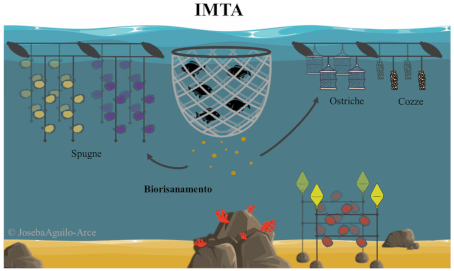

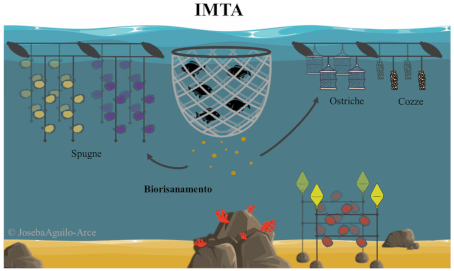

Among the systems proposed, Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) is a sustainable and environmentally friendly polyculture that combines the rearing of fed species (e.g., fish or shrimp) and extractive species that use waste from the fed species for their growth and does not require additional dietary inputs (such as macroalgae to remove inorganic substances and filter-feeding or detritivorous invertebrates to remove the dissolved and particulate organic component). In this context, marine sponges emerge as potential bioremediators of fish farming-derived organic matter, as they have a high capacity for filtration and retention of dissolved and particulate matter between 0.5 and 50 µm in diameter (e.g., [5,6,7,8]). As a result, up to 200% growth of biomass in just a few months has been obtained, with some Mediterranean species reared in these systems (e.g., [9,10,11,12,13,14]). Despite these impressive results, their inedibility for humans hinders the profitability of the reared by-product and slows down its implementation and the development of the aforementioned systems. Nevertheless, when these bioremediator by-products have a potential valorization, such as aquariology, the higher profitability of the system, the possible reduction of effluent fees, entry into new markets, and greater public and governmental acceptance have been described as favorable elements for its implementation [15]. In this sense, IMTA may increase revenues by up to 4% and reduce the natural and market risks of the aquaculture sector, making conversion from monoculture to polyculture a worthwhile undertaking [16]. On the other hand, this conversion has been shown to positively affect local benthic communities by promoting higher species recruitment that increases diversity and improves the ecological quality status of these systems, therefore reducing its environmental impact [17]. Marine ornamental aquaculture can play a crucial role in achieving a balance between economic viability and environmentally friendly practices. In fact, today less than 5% of marine ornamental species are farmed and even fewer are available in mass production to supply the growing demand of this business [18]. The rest come from natural stocks that are probably already overexploited, as an excess of specimens must be harvested to offset all losses along the supply chain. These unsustainable practices may lead to the collapse of this industry, as is currently known, so new policies arising from this problem may restrict the harvesting and sale of marine animals [18]. By then, aquaculture alternatives would have to be ready since a drastic decrease in the availability of wild organisms would lead to an increase in demand that could only be met by farmed specimens [18]. To this end, there is a great need to better understand the global marine aquarium trade as well as the risks and benefits of its aquaculture industry. At the same time, the focus should be on the potential market for its products and the reduction of its production costs. To do so, market analysis, optimization of farming methodology and increased knowledge of key biological aspects (such as reproduction, feeding and diseases) are necessary [18]. In this sense, IMTA with sponges can represent a sustainable and environmentally friendly specimen supply able to minimize the impacts of wild ornamental organisms’ collection; indeed, they may potentially be employed for the restoration of depleted ornamental populations [19].

The reef aquarium market is expected to continue growing worldwide at an annual rate of more than 10% to reach a value of USD 11 billion by 2028 [20]. The sponge and coral trade alone accounted for USD 171 million in 2020 [21]. In Europe, the pet-related industry is an important sector of the economy that is growing mainly due to the increase in the number of pets, and among these, there are more than 16 million aquariums, of which fish in Italy account for almost 50% of pets [22]. The use of questionnaires to assess the origin and quantity of ornamental species sold for aquariology has been shown to reveal possible underestimates in data published by official databases, which would provide necessary information to control the trade market [23]. In fact, the current supply chain of ornamental species is long, with too many intermediaries that hinder the traceability of the organisms traded and their regulation for the sustainable management of the natural communities from which they originate. The current methods used for this purpose are not adequate due to their invasiveness and non-destructive techniques such as bacterial barcoding have been proposed for their traceability [24]. Marine sponges and IMTA systems would be a sustainable solution to the problems described above, thanks to being holobionts and their regenerative capacity (which facilitates the use of traceability techniques) and the reduction of the number of intermediaries between the farmers and the client, respectively.

Overall, the exchange of cultured aquarium ornamental species seems a profitable opportunity for the development of valorization chances for specimens supplied from polyculture facilities. In this context, we conducted a survey to understand the interest of Italian aquariologists in sponge specimens and their willingness to purchase them from sustainable farms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

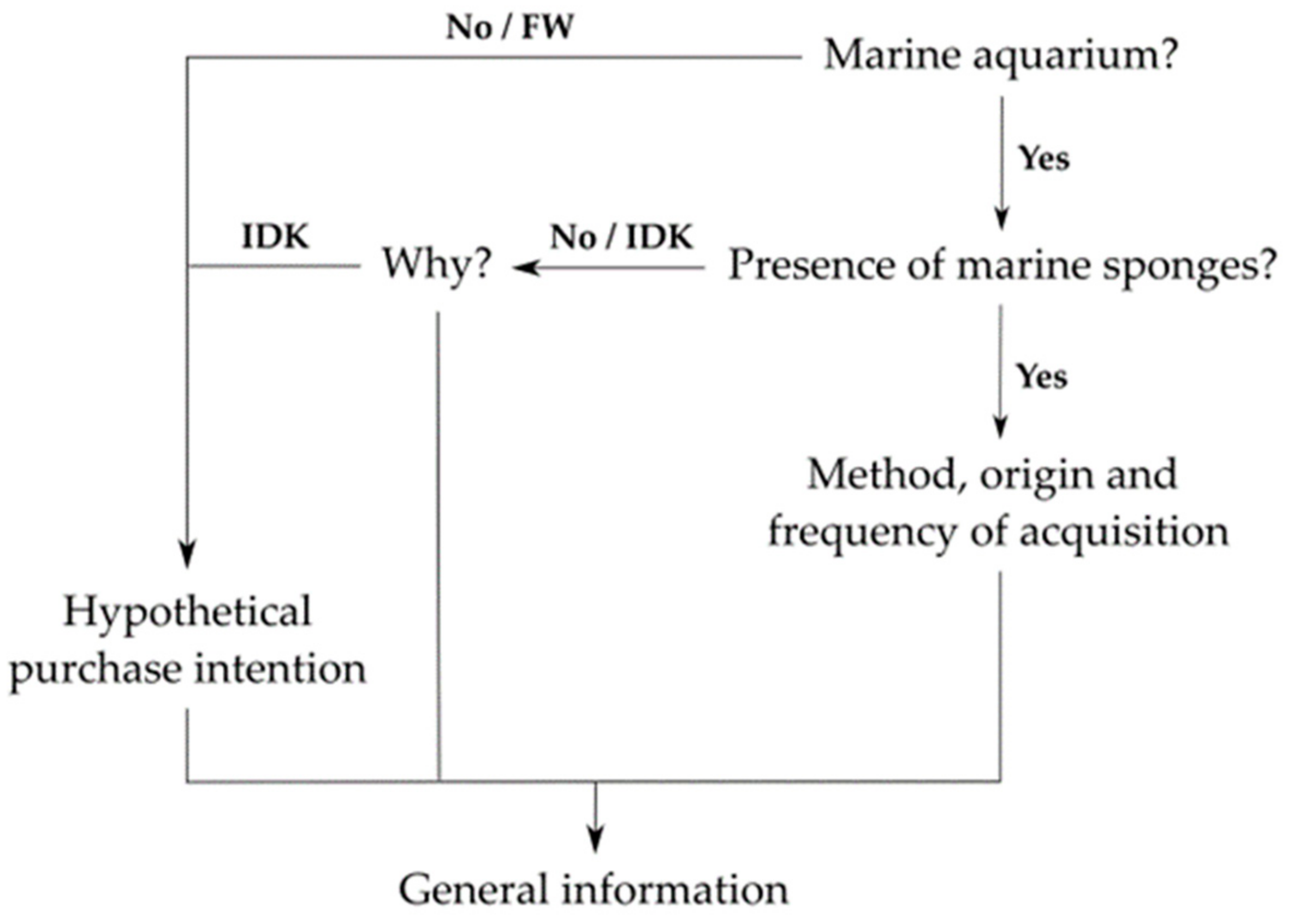

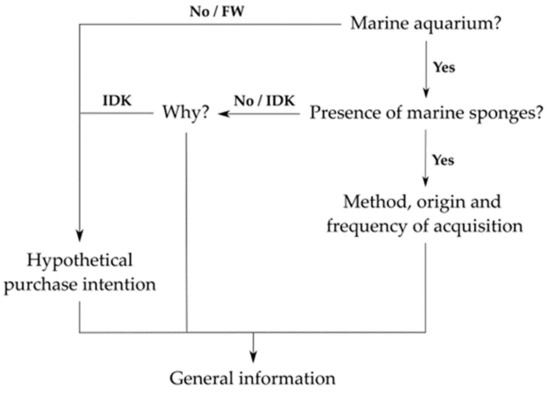

The intended information for the study was obtained by means of an anonymous questionnaire organized into four sections (Appendix A and Appendix B). The first three questions evaluated general knowledge on marine sponges, their filtering ability and IMTA systems, and were the same for every participant; the second section targeting aquariology habits followed a “conditional branching” path (represented in Figure 1) with which the following data was obtained: type of aquarium, the presence of sponges or the reasons for their absence and the method of acquisition, geographical origin and frequency; the third section consisted of five sustainability questions, regarding environmental concern, awareness of own actions environmental impact, willingness to make sacrifices for it and the im-portance of sustainable production systems and the proximity between production and sale locations. Section four collected sociodemographic information about participants, specifically, gender, age, education level, and region of residence, with the latter being the only mandatory information.

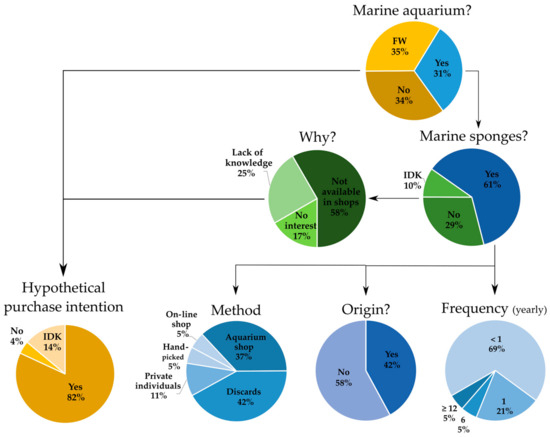

Figure 1.

“Conditional branching” path followed in Part II of the questionnaire. FW: Fresh water; IDK: “I don’t know”.

All questions in the first two sections were closed-ended in order to ease respondents’ experience and obtain quantifiable data, in some of them with either an open answer or an “I don’t know” (IDK) option. Information from section three followed a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “completely”). After parts I and II, a short paragraph with corresponding general information and images was added. At the end of parts II and III, a hypothetical question about purchase intention was proposed to evaluate a possible market. After part IV, a final open box was added to express any information or suggestions. After its preparation using Google forms, the survey was distributed on March 2023 using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and Telegram, in which Italian aquariophily groups were targeted. A printed QR code was also distributed among local pet stores and the University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy. The answering period ended on September 2023 after 6 months.

2.2. Data Analysis

The possible relationships between sociodemographic status (regions of residence grouped in northern, central and southern areas and education level) and all information gathered in parts I, II and III as well as the final question were examined by univariate chi-square (χ2) analysis using R 4.3.0 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Adjusted Standardized Residuals were used to detect over- or under-represented proportions in the case of significant relationships.

2.3. Privacy Considerations

At the beginning of the questionnaire, information about funding projects and data treatment procedures was available. Being an online questionnaire posted on social media groups (or QR format) and therefore the accession being voluntary, it was considered that by answering the questionnaire completely anonymously, they agreed to participate in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and General Knowledge

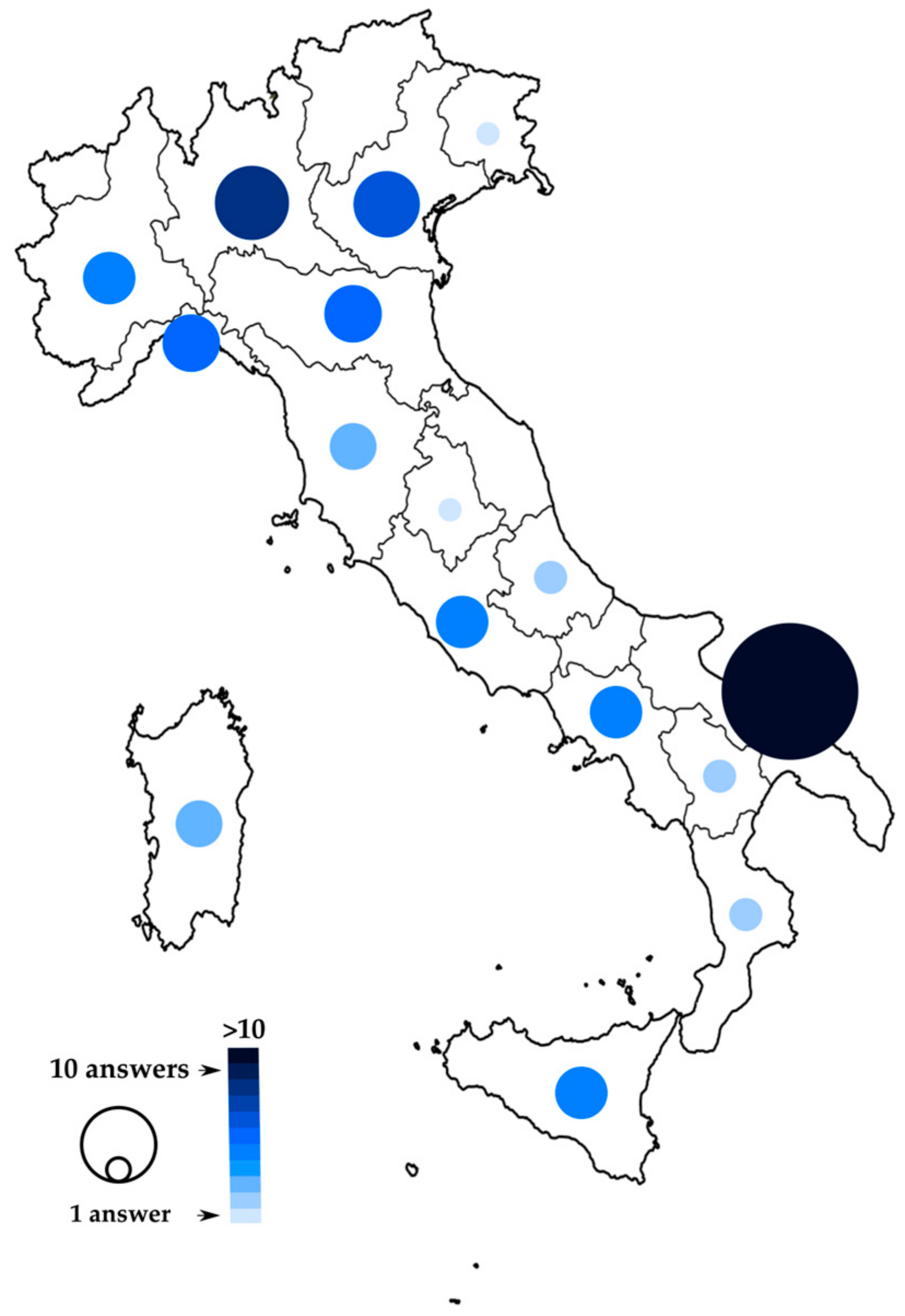

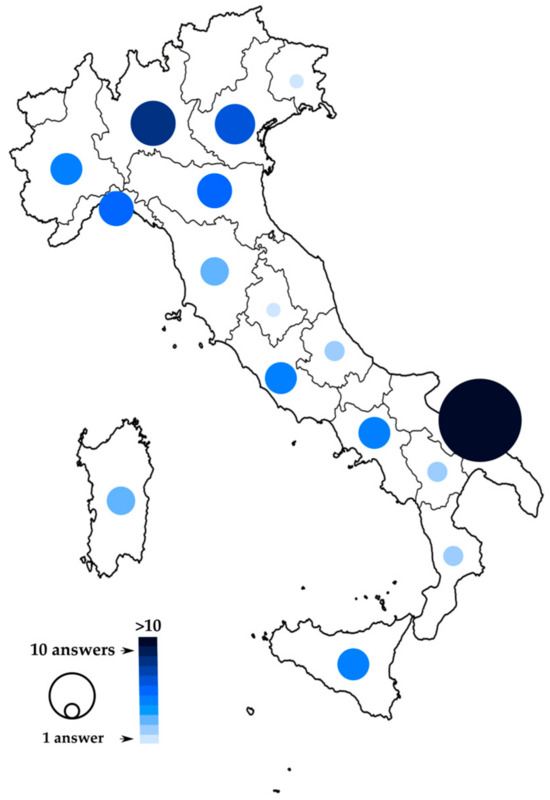

A total of 101 people from almost all Italian regions participated in the study (Figure 2), mainly from the northern (Lombardy, Liguria, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna) and southern (Apulia) areas, with a mean age of 38 years (SD = 14.22). The gender ratio was 2:1 (66% male, 33% female), while the education level showed equal frequencies between respondents who graduated and did not graduate from university (49 and 51%, respectively). Interestingly, although almost 90% of people were aware of marine sponges and their filtering activity, only 21.8% knew what IMTA systems were and how they worked, regardless of their education level (χ2 = 1.149, p = 0.284).

Figure 2.

Collected answers based on the region of origin of the respondents. Each answer is represented by one circle, whose size and the intensity of the color are directly proportional to its frequency.

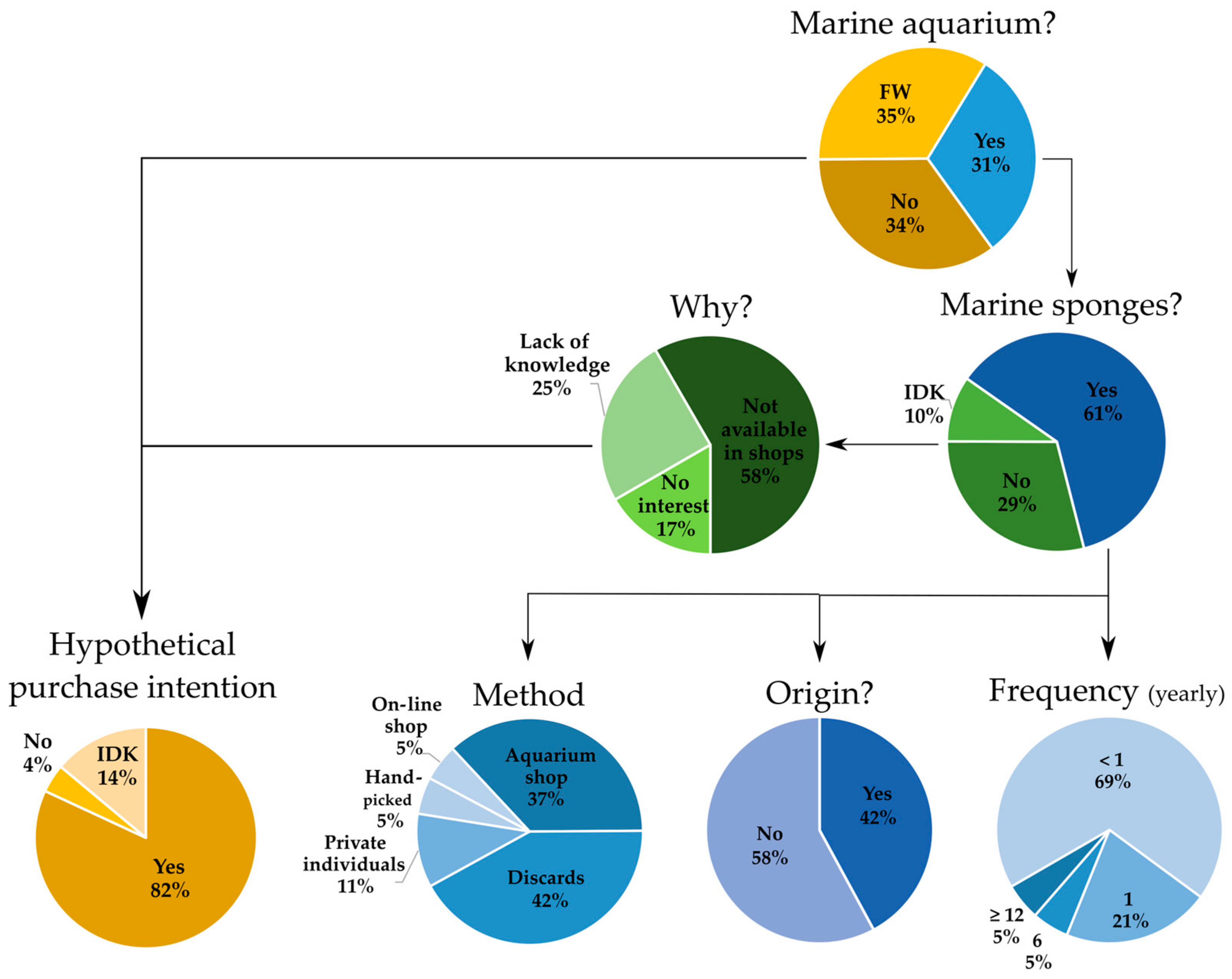

3.2. Aquarium Matters

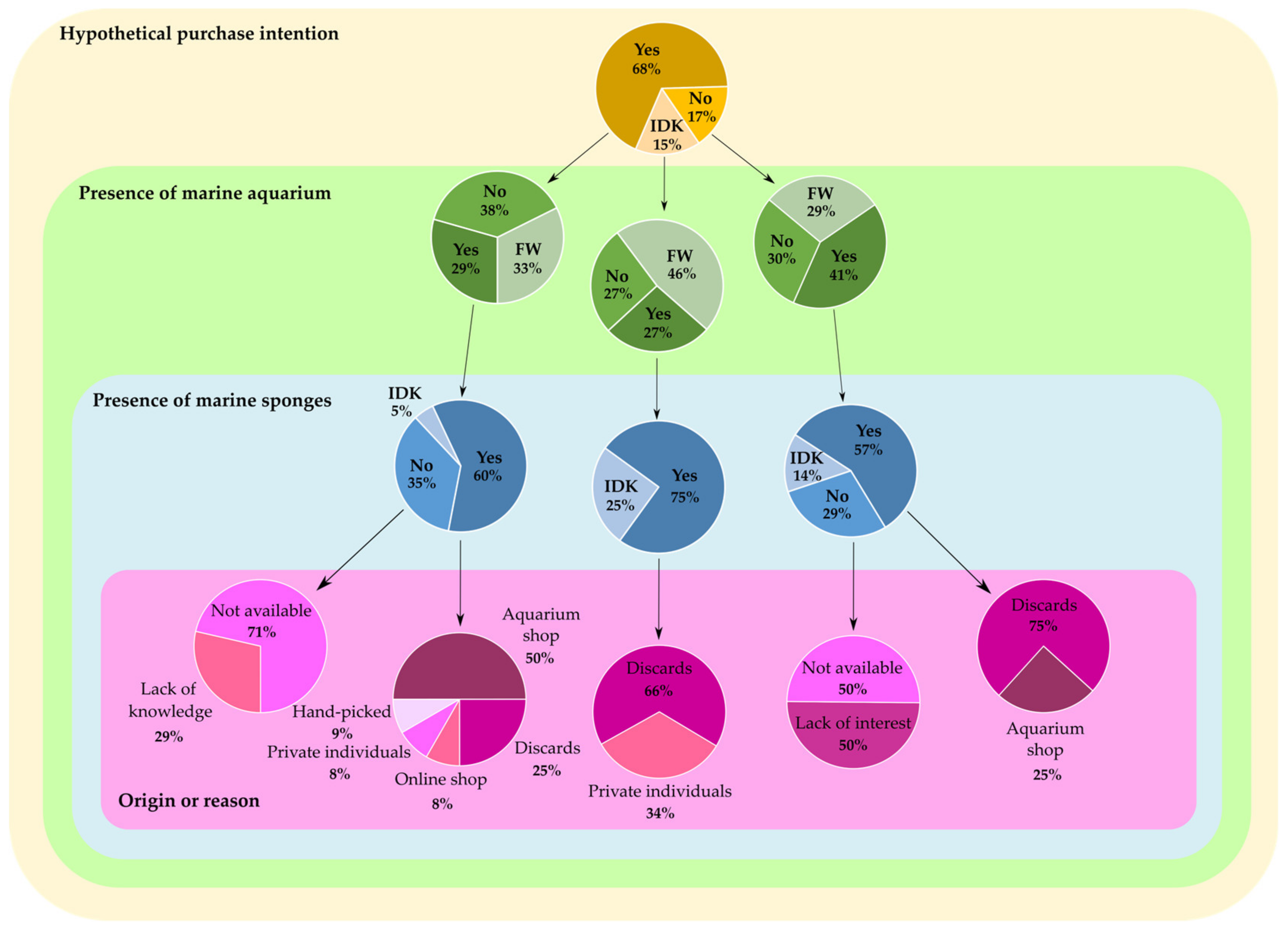

In the data retrieved from part II (represented in Figure 3) and despite trying to address the questionnaire to people with aquariums (and preferably marine aquariums), 34.7% of the respondents stated that they had none and 34.6% that they had freshwater aquariums. Of those with marine aquaria (30.7%), 61.3% said they had sponges in their aquarium, acquiring them mainly once a year or less (89.5%). Ownership of marine aquariums was proportionally higher in the central area, where 75% of respondents confirmed their presence at home (Figure 4A; χ2 = 15.462, p = 0.004).

Figure 3.

Pie chart representation of the statistics calculated following the “conditional branching” pathway designed for Part II. FW: Fresh water; IDK: “I don’t know”.

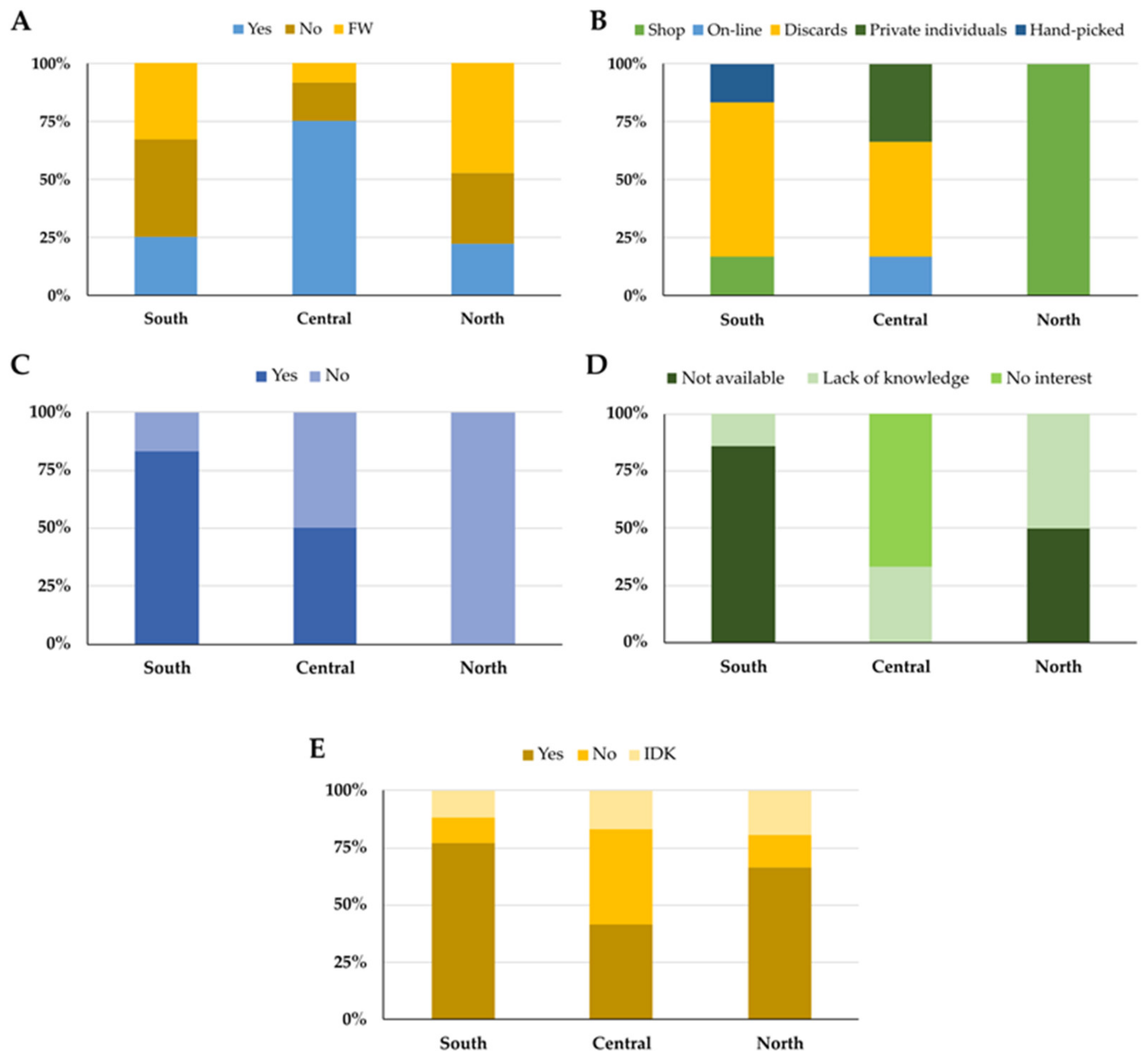

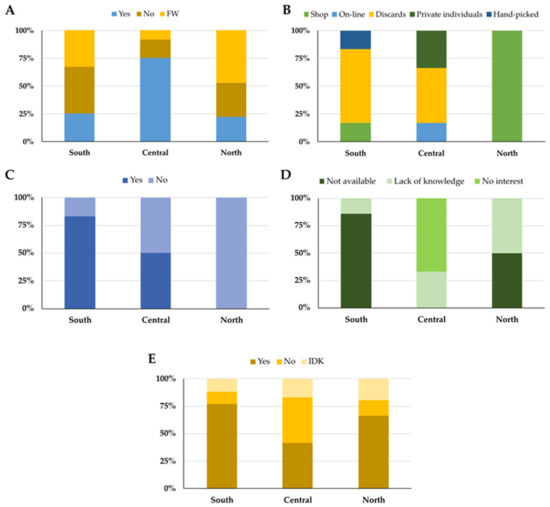

Figure 4.

Frequency of answers (%) based on area of residence and presence of marine aquarium (A), method of acquisition of sponges (B), knowledge of their geographical origin (C), reason of their absence in marine aquariums (D), and purchase intention or frequency change (E). FW: Fresh water; IDK: “I don’t know”.

In terms of where the sponges come from, discards from professional fishing dominate (42.1%), followed by aquarium shops (36.8%), private aquarists (10.5%) and personal collection and online shopping (both 5.3%) (Figure 3). A respondent noted that some sponges arrived from purchasing rocks matured in other aquariums that, at that time, were undeveloped and thus unnoticeable. These methods of acquisition varied among areas (χ2 = 20.571, p = 0.008), with trusted shops being the option selected significantly more often by the interviewees from the North (100%) (Figure 4B). Discards from commercial fishing accounted for 66% of the responses from the southern area, and online shops and private individuals appeared as an acquisition method only among respondents from central regions (Figure 4B). At the same time, when sponge keepers were asked if they knew the geographical origin of the sponges they owned, more than half (58%) said they did not (Figure 3). All of those who answered positively to the question (42%) pointed to the Mediterranean as the origin of their sponges, some of them specifying regions such as the Northern Tyrrhenian, Ionian, Adriatic or Aegean Seas. Just one interviewee who declared a trusted shop as the main source of sponges mentioned sponges reared in diverse geographical locations as their general origin. This knowledge of the possible geographical area of provenience of traded sponges significantly varied among Italian regions (χ2 = 8.550, p = 0.014), as no northern respondents knew the origin of their individuals, compared to 83.3% of southerners, who in fact did (Figure 4C). In central regions, the proportions appeared to be equal (50% for both Yes and No answers).

Those who did not have sponges in their marine aquaria (29%) stated that the reasons for this were mainly the impossibility of acquiring them from trusted shops (58.3%) as well as lack of knowledge about them and voluntary disinterest (25 and 16.7%, respectively, Figure 3), which varied among regions (χ2 = 9.578, p = 0.048). The southern regions were dominated by lack of availability and the central regions by lack of interest, the latter reason being registered only among respondents (Figure 4D). Nevertheless, in the last question of this part regarding a possible purchase intention proposed to aquariophilists unfamiliar with marine sponges (owing to the lack of either a marine aquarium or knowledge), 82.2% of the people showed a positive attitude towards the proposed idea. Geographic area did not influence these results (χ2 = 1.473, p = 0.831), with a mean positive answer proportion of 79.77% (SD = 5) for all three areas.

3.3. Sustainable Awareness

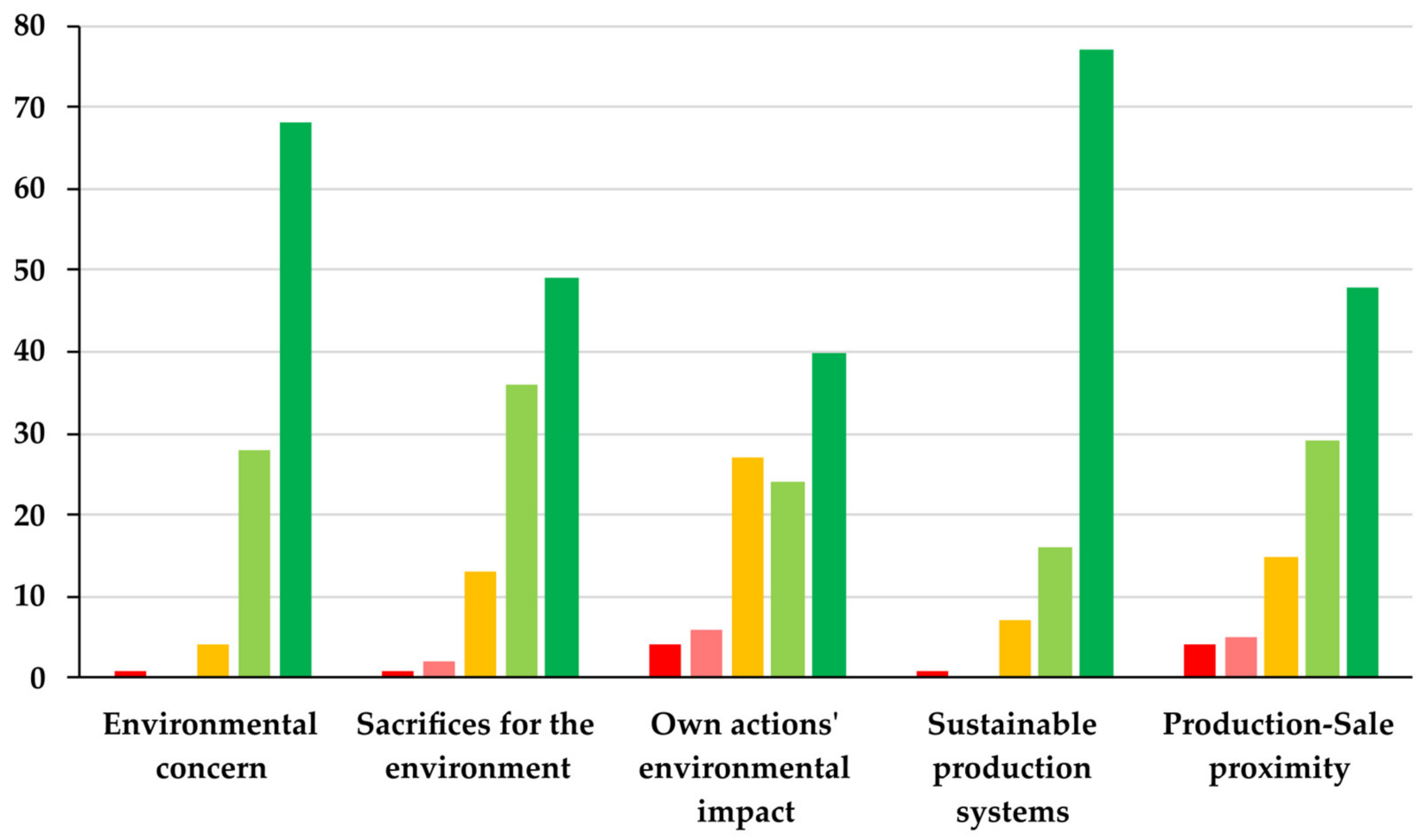

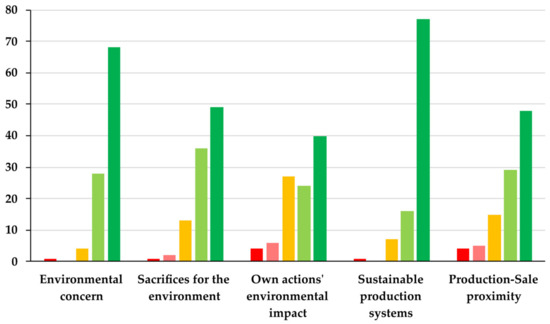

In the sustainability section, the vast majority of respondents declared that they were concerned and willing to make sacrifices for the environment (95 and 84%, respectively; ≥4 in Figure 5), although 37% were hesitant about the impact of their actions on the environment (<4 in Figure 5). This dubious attitude slightly differed among areas (χ2 = 6.053, p = 0.048), with central regions showing a higher proportion of these respondents (66% against the 36.1 and 8.8% recorded from the north and south, respectively).

Figure 5.

Respondents’ sustainability perception recorded in part III by the number of answers expressing the level of accordance or importance: from “not at all” (red) to “completely” (green).

Regarding production systems, almost all of them (92%) agreed on the high value of using sustainable systems and 77% attributed high importance to the geographical proximity between the place of production and the sale of the products (≥4 in Figure 5). Nevertheless, the latter results had a strong geographic component (χ2 = 27.989, p < 0.001), as almost 70% of respondents from the south assigned moderate or less importance to the proximity compared to the 16.7% from each of the other regions.

3.4. Final Question: Effect of Sustainability on Hypothetical Purchase Intention

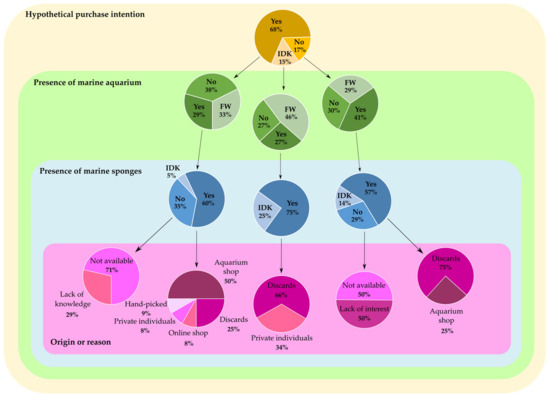

After part III, in the final question on the hypothetical purchase intention or frequency change regarding sponges reared in sustainable production systems such as IMTA (represented in Figure 6), only 17% of the total number of respondents showed no interest, of which 76.5% did not confirm the presence of marine sponges (either because they lacked marine aquariums or sponges in them). On the other hand, of the 2 out of 3 respondents who would be willing to acquire them (68.3%), 17.4% were people who currently had sponges (mainly from aquarium shops) and 10.1% did not have them due to unavailability or lack of knowledge, and the rest were people without an aquarium or with a freshwater one. Of the respondents, 15% were hesitant about the market possibility proposed, being predominantly people without a marine aquarium (73.3%). Although not significant, geographic area slightly influenced these results (χ2 = 8.4, p = 0.078), with people from the central area being rather less willing to buy sponges (41.67%) and those from the south being the most willing (76.92%) (Figure 4E).

Figure 6.

Classification of all the respondents based on the answer given to the last question (yellow) and presence of marine aquarium (green), presences of sponges in marine aquariums (blue) and their origin or reason for their absence (pink). FW: Fresh Water; IDK: “I Don’t Know”.

4. Discussion

Marine sponges represent emerging by-products of IMTA systems, although their profitability is still under development [3]. Their most promising economic potential concerns the ability to produce bioactive metabolites that have been interesting in different industries over the last decades; nevertheless, their market is not yet well established owing to the so-called “biomass supply problem”. Collection of ornamental species for aquariology is equally based on natural stocks that remove millions of marine organisms annually from local ecosystems, with the tropical countries of Asia and the US being the largest exporters and importers, respectively [25,26]. In this context, sponge farming (and, more specifically, IMTA systems) could represent a suitable alternative that has proven to be effective with bath sponges and affects the local economy positively (e.g., [27,28]). Therefore, rearing ornamental species for aquariology represents another valorization route that may benefit from this sustainable production method and the present paper has proven so.

The designed questionnaire and different spreading social platforms enabled the researchers to obtain 101 responses from almost all of the Italian territory (Figure 2). The locally spread physical format (i.e., QR code) has also proven to be effective, being responsible for the significantly higher amount of answers received from Apulia. Even in inland regions, sponges and their filtering ability are well known among Italians (88%). IMTA systems, despite being an increasingly topical research issue in the aquaculture sector with more than 160 research items in the last 15 years (using the “Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture” term in Scopus, accessed on 11 September 2023), were known to only 1 out of 5 respondents, which highlights the need for the development and communication of this sustainable approach.

Part II showed interesting results regarding the method of acquisition of sponges and the reason for their absence. Fishing discards were identified as the source of choice for almost half of the sponge owners, followed by purchases from local stores (42.1 and 36.8%, respectively, Figure 3). These results show a geographic component, with discards being more common in southern coastal regions and stores being the option selected by all of the aquariophilists surveyed from the north (Figure 4). In relation to this, the methodology of obtaining sponges seems to be related to the knowledge of their origin. Since most of the sponges came from fishing discards in the south, among respondents of this area, their origin was significantly better known than in the north, where 100% of the holders bought them in stores and none of them knew their origin. These results denote a lack of interest or information about the animals sold in aquarium stores. In this sense, more sustainable and local methodologies for their collection would improve the knowledge of aquariophilists about the product and the traceability of the organisms for a more sustainable management of the natural communities from which they originate. On the other hand, unavailability in stores is the main reason for the absence of Porifera in aquariums at the national level, comprising 85.7% of responses from the southern regions. In fact, of the more than 600 aquarium stores registered in Italy (according to [29]), almost half of them are located in the 8 northern regions, doubling the number of stores in the south.

The vast majority of respondents showed a high sustainable awareness valuing the proximity of the products, their sustainable production and even being willing to make sacrifices for the environment (Figure 5). In fact, 68.3% of respondents would change their intention/frequency of purchasing sponges if they came from sustainable systems, such as IMTA (Figure 6). Although about a third of them were people without aquariums and therefore without the knowledge of the effort involved in maintaining an aquarium in optimal conditions. What is most encouraging for the proposed potential market is (1) that the absence of these animals in the marine aquariums of people willing to purchase them (left path in Figure 6) could be solved with awareness and greater availability of sponges in stores and (2) that the respondents who showed doubts or denied the change of attitude towards the proposed hypothetical market (center and right paths in Figure 6) are mainly people who currently do not pay for them and therefore are not customers of the industry.

The appreciation of non-edible biomass from IMTA systems is a pending issue that slows down its globalization and implementation. However, in Italy, non-conventional biomass cultivated in an IMTA system, such as the polychaete worm Sabella spallanzanii, has been shown to obtain similar growth results to conventional feed when used as a food substitute for tropical aquarium fish [30]. In addition, some of the genera and species proposed by Calado [19] as potential ornamental sponge species have already been successfully reared in Italian IMTA systems (i.e., Ircinia spp. and Aplysina aerophoba [3]), supporting aquariology as a promising market for the by-products of these farms.

For example, there are a total of nearly 29,900,000 aquarium fish in Italy [22]. To make the calculations easier, considering that one out of 10 is marine [31] and placing 7 individuals per tank [22], this would mean the presence of 427,143 marine aquariums in Italy. Assuming one of them per person and applying the percentage of people with marine aquariums interested in buying sponges calculated in the present study (64.5%), there are more than 275,500 aquariophilists willing to purchase these sustainably reared animals. With prices of around EUR 10 per individual (e.g., Acquariomania.net and Exoticfarm.shop, (21 January 2024)), although underestimated compared to other national and most US prices) and a calculated average purchase rate of once a year (Part II of the present work), its estimated market value reaches almost EUR 3 million per year, which, added to the fact of its low production cost [32], would be a powerful source of income. These quick calculations exclude large public aquariums (where the number of aquariums, their size and the number of individuals per tank are greater) and other possible uses of the reared sponge biomass (such as bath sponges and bioactive compound production), which would be a fundamental market of these systems.

The overexploitation of marine resources for ornamental species collection in European waters poses a potential threat to marine ecosystems, especially in the absence of dedicated regulatory measures at the European level. Porifera, or sponges, are filter feeder organisms representing one of the dominant and most abundant components of benthic communities in the world’s oceans. They are considered “living hotels” because of the great variety and abundance of endobionts belonging to other taxonomic groups, including cnidarians, polychaetes, crustaceans and echinoderms, playing a fundamental role in increasing the biodiversity of ecosystems [33,34,35]. Historically, the systematic collection of sponges has meant a critical reduction in their natural stocks, such as the bath sponge Spongia officinalis (considered endangered [36]) or the pharmacologically interesting Dysidea avara (collected for its avarol content, a powerful bioactive compound [37]). However, despite the described positive ecosystem services provided by these animals and, therefore, the risk of reducing their populations, there is controversy related to the theoretically sustainable hand-collection of specimens, a study concluding that this practice probably has a negligible impact on certain communities [38]. In this context, in view of their economic potential, trials have been carried out to define the methodology and improve the yield of biomass production (either for bath sponges or for bioactive compound synthesis), which have promoted the development of the aquaculture of these animals (e.g., [9,13,39,40]).

Nowadays, however, the major threats to these animals are both direct (e.g., in the form of physical damage from trawling, oiling or deep-sea mining) and indirect (e.g., epidemic events, pollution, increased sedimentation from bottom fishing or climate change) [35]. Therefore, for some years now, the protection of their most vulnerable populations to the aforementioned direct activities, although still scarce, has been encouraged [41]”.

To protect benthic ecosystems and address this lack of regulation, it is crucial to propose alternative sustainable solutions and legislative measures for effective sector regulation. According to Wood [42], a comprehensive understanding of the resource and its dynamics, including breeding cycles, recruitment times and growth rates of targeted species, is essential for selecting an appropriate management strategy. Considerations should encompass the issuance of harvesting permits, establishment of certified wholesalers, adoption of suitable harvesting equipment and methods, implementation of size limits for harvested species, species-based quotas, protection of rare species and the introduction of harvesting seasons. Ultimately, the cultivation of commercially valuable ornamental organisms emerges as a sustainable alternative to harvesting from natural populations [42]. The suggestions presented in this research aim to promote the value of sponges cultivated in multi-trophic aquaculture systems as sustainable ornamental species, offering economic opportunities and benefiting local communities.

5. Conclusions

With the demonstrated capacity of IMTA systems to cultivate marine sponges and the social acceptance detected in this preliminary study, it has been shown that these invertebrates can be used as ornamental organisms in the aquariology sector. In particular, both in the north because of its demand and in the south because of the lack of supply, Italy could be a hot spot for the successful implementation of the proposed sustainable systems, which at the same time would reduce pressure on natural communities and support the local economy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.-A., A.S. and C.L.; methodology, J.A.-A. and A.S.; formal analysis, J.A.-A.; data curation, J.A.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.-A. and C.L.; writing—review and editing, J.A.-A., A.S., R.T. and C.L.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, R.T. and C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out within the projects REMEDIA Life (LIFE16 ENV/IT/000343): Remediation of Marine Environment and Development of Innovative Aquaculture: exploitation of Edible/not Edible biomass and PO FEAMP 2014/2020—Misura 2.47—Innovazione art. 47 Reg. 508/2014: Approcci innovativi per una acquacoltura integrata e sostenibile.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to lack of legislation in Italy that requires Ethics Committee approval for non-clinical or pharmacological subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results of the study can be provided upon request by the first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all local shops, social media groups and anonymous respondents for distributing and answering the questionnaire. In particular, Francesca Araldo, Alessandra Gravina, Patrizia Puthod, Muriel Oddenino and Miriam Ravisato, who collaborated in gathering responses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Printable Version of the Questionnaire (English Version)

SPONGES AS ORNAMENTAL SPECIES FOR THE AQUARIUM

First of all, we would like to thank you for your kind cooperation.

We are conducting scientific research aimed at valorizing poriferous biomass (or sponges) reared in integrated multi-trophic aquaculture systems within the framework of national and international projects (Remedia-Life: Remediation of Marine Environment and Development of Innovative Aquaculture exploitation of Edible/not Edible biomass https://remedialife.eu/; OP FEAMP 2014/2020: Innovative Approaches for Integrated and Sustainable Aquaculture).

The purpose is to assess the perception and appreciation of sponges as biofilters and ornamental aquarium species.

Should you decide to respond, please be advised that your answers will remain completely anonymous and that the few personal data requested will be used only to make statistical calculations.

Please respond with the utmost sincerity, as we consider your answers particularly important.

(I) General knowledge

A1-Do you know what sea sponges are?

Yes No

A2-Do you know that they are filtering organisms that can improve water quality?

Yes No

A3-Do you know what IMTA (Integrated MultiTrophic Aquaculture) systems are?

Yes No

INFORMATION

Sponges are aquatic invertebrates belonging to the phylum Porifera, which is among the oldest on our planet. They are animals that live mainly on the seabed, usually anchored to the substrate and feed by filtering bacteria, plankton, organic matter and even viruses.

IMTA is a form of polyculture in which species fed commercial diets (e.g., fish or shrimp) and extractive species that use wastes from the fed species for their growth and do not require additional dietary inputs (such as macroalgae to remove inorganic matter and filter-feeding or depositional invertebrates to remove dissolved and particulate organic matter) are reared in an integrated system.

This combined farming reduces the impact of the production system on the surrounding environment and can provide an alternative source of income for the industry, supporting a circular economy.

(II) Aquariophily

B1-Do you have a marine aquarium?

Yes No Fresh water

B2-Do you have sea sponges in the aquarium?

Yes No I don’t know

B3-How often do you buy sea sponges? (1 = Less than once a year; 2 = Once a year; 3 = Twice a year; 4 = Once every two months; 5 = Every month or more)

1 2 3 4 5

B4-Where do you buy them?

- □

- In your local aquarium store

- □

- In an online store

- □

- Other:

B5-Do you know the geographic origin of the sponges purchased? If yes, please specify in “Other”

- □

- No

- □

- Other:

B6-Why do you not acquire sponges?

- □

- It is not possible to buy them in the store

- □

- They are too expensive

- □

- I was not aware of their existence

- □

- Other:

B7-If you had a marine aquarium and knew the benefits described above, would you be willing to purchase marine sponges?

Yes No I don’t know

INFORMATION

Most ornamental aquarium sponges come from tropical areas, with the United States being a major exporter. They are obtained mainly by taking specimens from natural populations, which, despite their regenerative capacity, have a negative impact on the ecosystem.

(III) Sustainability

On a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 corresponds to “Not at all” and 5 to “Completely”):

C1-How concerned are you about the environment?

1 2 3 4 5

C2-How important is geographic proximity between where products are produced and where they are sold to you?

1 2 3 4 5

C3-How important is it to you to use sustainable production systems?

1 2 3 4 5

C4-How much do you believe that your actions result in an impact on the environment?

1 2 3 4 5

C5-How willing are you to make sacrifices to protect the environment?

1 2 3 4 5

C6-Would you change your intention/frequency to buy ornamental sea sponges if they were locally and sustainably sourced from IMTA systems?

- □

- Yes, I buy them now, but I would buy them more often.

- □

- Yes, I do not buy them now, but I would like to buy them.

- □

- No, I buy them now, and I would not change the frequency

- □

- No, I do not buy them now, and I would not like to purchase them

- □

- I don’t know

(IV) Socio-demographic data

All these data are optional except the region of residence

D1-Gender

Male Female Other

D2-Age:

D3-Region of residence (mandatory):

D4-Education level:

- □

- High school diploma or lower

- □

- Bachelor’s degree or higher

Thank you very much for your time. Below is a free space to write any comments or information you would like to attach.

If you would like to be informed about the future publication of the results, you can attach a reference email below.

Once again, thank you for your time and cooperation on behalf of all of the contributors.

Appendix B. Printable Version of the Questionnaire (Original: Italian)

SPUGNE COME SPECIE ORNAMENTALI PER L’ACQUARIO

Innanzitutto desideriamo ringraziarla per la sua gentile collaborazione.

Stiamo conducendo una ricerca scientifica finalizzata a valorizzare le biomasse di poriferi (o spugne) allevati in sistemi di acquacoltura multi-trofica integrata nell’ambito di progetti nazionali ed internazionali (Remedia-Life: Remediation of Marine Environment and Development of Innovative Aquaculture exploitation of Edible/not Edible biomass https://remedialife.eu/; PO FEAMP 2014/2020: Approcci Innovativi per una acquacoltura integrata e sostenibile).

L’intento è quello di valutare la percezione e l’apprezzamento delle spugne come biofiltri e specie ornamentali per acquari.

Se decidesse di rispondere, la informiamo che le sue risposte rimarranno completamente anonime e che i pochi dati anagrafici richiesti serviranno solo per realizzare calcoli statistici.

La preghiamo di rispondere con la massima sincerità, dato che riteniamo le sue risposte particolarmente importanti.

(I) Conoscenze generali

A1-Sa cosa sono le spugne marine?

Si No

A2-Sa che sono organismi filtratori in grado di migliorare la qualità dell’acqua?

Si No

A3-Sa cosa sono i sistemi IMTA (Acquacoltura Multi-Trofica Integrata)?

Si No

INFORMAZIONE

Le spugne sono invertebrati acquatici appartenenti al phylum Porifera, tra i più antichi del nostro pianeta. Sono animali che vivono prevalentemente sui fondali marini, di solito ancorati al substrato e si nutrono filtrando batteri, plancton, materia organica e anche virus.

L’IMTA è una forma di policoltura in cui vengono allevate in un sistema integrato specie alimentate con diete commerciali (ad es. pesci o gamberi) e specie estrattive che utilizzano per la loro crescita i rifiuti derivanti dalle specie alimentate e non necessitano di ulteriori input alimentari (come macroalghe per rimuovere le sostanze inorganiche e gli invertebrati filtratori o deposivori per rimuovere la componente organica disciolta e particolata).

Questo allevamento combinato riduce l’impatto del sistema produttivo sull’ambiente circostante e può offrire una fonte di reddito alternativa per il settore, favorendo un’economia circolare.

(II) Aquariofilia

B1-Ha un acquario marino?

Si No Acqua dolce

B2-Se ha risposto “Sì” nella domanda precedente, ha spugne marine nell’acquario?

Si No Non lo so

B3-Con quale frequenza compra spugne marine? (1 = Meno di una volta l’anno; 2 = Una volta l’anno; 3 = Due volte l’anno; 4 = una volta ogni due mesi; 5 = Ogni mese o più)

1 2 3 4 5

B4-Dove le acquista?

- □

- Nel negozio di acquariofilia di fiducia

- □

- In un negozio online

- □

- Altro:

B5-Sa qual è la provenienza geografica delle spugne acquistate? Se sì, specificare in “Altro”

- □

- No

- □

- Altro:

B6-Per quale motivo non acquisita spugne?

- □

- Non è possibile acquistarle in negozio

- □

- Sono troppo costose

- □

- Non ero a conoscenza della loro esistenza

- □

- Altro:

B7-Se avesse un acquario marino e conoscendo i benefici descritti precedentemente, sarebbe disposto ad acquistare spugne marine?

Si No Non lo so

INFORMAZIONE

La maggior parte delle spugne per acquari ornamentali proviene da aree tropicali, essendo gli Stati Uniti uno dei maggiori esportatori. Si ottengono principalmente attraverso il prelievo di esemplari da popolazioni naturali che, nonostante la loro capacità rigenerativa, ha un impatto negativo sull’ecosistema.

(III)-Sostenibilità

Su una scala da 1 a 5 (dove 1 corrisponde a “Per nulla” e 5 a “Del tutto”):

C1-Quanto è preoccupata per l’ambiente?

1 2 3 4 5

C2-Quanto è importante per lei la vicinanza geografica tra il luogo di produzione e quello di vendita dei prodotti?

1 2 3 4 5

C3-Quanto è importante per lei utilizzare sistemi di produzione sostenibili?

1 2 3 4 5

C4-Quanto crede che le sue azioni determinino un impatto sull’ambiente?

1 2 3 4 5

C5-Quanto è disposta a fare sacrifici per proteggere l’ambiente?

1 2 3 4 5

C6-Cambierebbe la sua intenzione/frequenza di acquistare spugne marine ornamentali se fossero di provenienza locale e sostenibile come dai sistemi IMTA?

- □

- Sì, adesso le compro però le comprerei più spesso

- □

- Sì, adesso non le compro però mi piacerebbe acquistarle

- □

- No, adesso le compro e non cambierei la frequenza

- □

- No, adesso non le compro e non mi piacerebbe acquistarle

- □

- Non lo so

(IV)-Dati socio-demografici

Tutti questi dati sono facoltativi eccetto la regione di domicilio

D1-Genere

Maschile Femminile Altro

D2-Età:

D3-Regione di domicilio (obbligatorio):

D4-Livello di istruzione

- □

- Diploma o inferiore

- □

- Laurea o superiore

Grazie mille per il suo tempo. In basso è presente uno spazio libero per scrivere eventuali commenti o informazioni che si desidera allegare.

Se desiderate essere informati sulla futura pubblicazione dei risultati, potete allegare un’e-mail di riferimento qui sotto.

Ancora una volta, grazie per il vostro tempo e la vostra collaborazione a nome di tutti i collaboratori.

References

- Chaviarà, D. Le spugne e i loro pescatori dai tempi antichi ad ora. Mem. Reg. Com. Talassogr. Ital. 1920, 74, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bierwirth, J.; Mantas, T.P.; Villechanoux, J.; Cerrano, C. Restoration of marine sponges—What can we learn from over a century of experimental cultivation? Water 2022, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilo-Arce, J.; Ferriol, P.; Trani, R.; Puthod, P.; Pierri, C.; Longo, C. Sponges as emerging by-product of Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture (IMTA). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavolini, F. Memorie per Servire alla Storia de’ Polipi Marini; Wentworth Press: Napoli, Italy, 1785; pp. 262–265. [Google Scholar]

- Reiswig, H.M. Particle feeding in natural populations of three marine demosponges. Biol. Bull. 1971, 141, 568–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pile, A.J.; Patterson, M.R.; Witman, J.D. In situ grazing on plankton. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996, 141, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes, M.; Coma, R.; Gili, J.M. Natural diet and grazing rate of the temperate sponge Dysidea avara (Demospongiae, Dendroceratida) throughout an annual cycle. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999, 176, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, M.; Zhang, X.; Cao, X.; Xue, L.; Cao, H.; Zhang, W. Selective feeding by sponges on pathogenic microbes: A reassessment of potential for abatement of microbial pollution. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 403, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, W.E.; Wimmer, W.; Schatton, W.; Böhm, M.; Batel, R.; Filic, Z. Initiation of an aquaculture of sponges for the sustainable production of bioactive metabolites in open systems: Example, Geodia cydonium. Mar. Biotechnol. 1999, 1, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronzato, R.; Bavestrello, G.; Cerrano, C.; Magnino, G.; Manconi, R.; Pantelis, J.; Sara, A.; Sidri, M. Sponge farming in the Mediterranean Sea: New perspectives. Mem. Qld. Mus. 1999, 44, 485–491. Available online: https://biostor.org/reference/110020 (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Osinga, R.; Sidri, M.; Cerig, E.; Gokalp, S.Z.; Gokalp, M. Sponge aquaculture trials in the East-Mediterranean Sea: New approaches to earlier ideas. Open Mar. Biol. J. 2010, 4, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Cardone, F.; Corriero, G.; Licciano, M.; Pierri, C.; Stabili, L. The co-occurrence of the demosponge Hymeniacidon perlevis and the edible mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis as a new tool for bacterial load mitigation in aquaculture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 3736–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, M.; Wijgerde, T.; Sarà, A.; De Goeij, J.M.; Osinga, R. Development of an integrated mariculture for the collagen-rich sponge Chondrosia reniformis. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giangrande, A.; Pierri, C.; Arduini, D.; Borghese, J.; Licciano, M.; Trani, R.; Corriero, G.; Basile, G.; Cecere, E.; Petrocelli, A. An innovative IMTA system: Polychaetes, sponges and macroalgae co-cultured in a Southern Italian in-shore mariculture plant (Ionian Sea). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileti, A.; Arduini, D.; Watson, G.; Giangrande, A. Blockchain traceability in trading biomasses obtained with an Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridler, N.; Wowchuk, M.; Robinson, B.; Barrington, K.; Chopin, T.; Robinson, S.; Page, F.; Reid, G.; Szemerda, M.; Sewuster, J.; et al. Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA): A potential strategic choice for farmers. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2007, 11, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghese, J.; Musco, L.; Arduini, D.; Tamburello, L.; Del Pasqua, M.; Giangrande, A. A Comparative Approach to Detect Macrobenthic Response to the Conversion of an Inshore Mariculture Plant into an IMTA System in the Mar Grande of Taranto (Mediterranean Sea, Italy). Water 2023, 15, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, R.; Olivotto, I.; Oliver, M.P.; Holt, G.J. Marine Ornamental Species Aquaculture; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; Volume 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, R. Marine ornamental species from European waters: A valuable overlooked resource or a future threat for the conservation of marine ecosystems? Sci. Mar. 2006, 70, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandview Research. Reef Aquarium Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Product (Component, Natural), by End Use (Household, Zoo & Oceanarium), by Region (Europe, Asia Pacific), and Segment Forecasts, 2021–2028. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/reef-aquarium-market-report (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XV Edizione Rapporto Assalco-Zoomark. Pet in Italia: 15 Anni di Cambiamenti in Famiglia e in Società. Available online: https://www.zoomark.it/media/zoomark/pressrelease/2023/rapporto_assalco_-_zoomark_2022_-_sintesi.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Murray, J.M.; Watson, G.J.; Giangrande, A.; Licciano, M.; Bentley, M.G. Managing the Marine Aquarium Trade: Revealing the Data Gaps Using Ornamental Polychaetes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, F.P.; Valenti, W.C.; Calado, R. Traceability issues in the trade of marine ornamental species. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2013, 21, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabnitz, C.; Taylor, M.; Green, E.; Razak, T. From Ocean to Aquarium: The Global Trade in Marine Ornamental Species; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2003; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.F.; Behrens, M.D.; Max, L.M.; Daszak, P. US drowning in unidentified fishes: Scope, implications, and regulation of live fish import. Conserv. Lett. 2008, 1, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinecultures. Available online: https://www.marinecultures.org/en/projects/spongefarming/spongefarming/ (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Tobey, J.A.; Haws, M.C.; Ellis, S.S. Aquaculture Profile for Pohnpei Federated States of Micronesia; Technical Report; NOAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. Available online: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/39936 (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- NegoziAcquari. Available online: https://www.negoziacquari.it/ (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Arduini, D.; Calabrese, C.; Borghese, J.; De Domenico, S.; Putignano, M.; Toso, A.; Gravili, C.; Giangrande, A. Perspectives for exploitation of Sabella spallanzanii’s biomass as a new Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) by-product: Feeding Trial on Amphiprion ocellaris using Sabella meal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.R.; Ledua, E.; Stanley, J. Regional Assessment of the Commercial Viability for Marine Ornamental Aquaculture within the Pacific Islands (Giant Clam, Hard and Soft Coral, Finfish, Live Rock and Marine Shrimp); Secretariat of the Pacific Community: Noumea, New Caledonia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oronti, A.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Elmore, C.E.; Auriemma, R.; Pesle, G. Assessing the feasibility of sponge aquaculture as a sustainable industry in The Bahamas. Aquac. Int. 2012, 20, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, L.; Idan, T.; Shefer, S.; Ilan, M. Macrofauna inhabiting massive demosponges from shallow and mesophotic habitats along the Israeli Mediterranean coast. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7, 612779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, R.W.; Boury-Esnault, N.; Vacelet, J.; Dohrmann, M.; Erpenbeck, D.; De Voogd, N.J.; Santodomingo, N.; Vanhoorne, B.; Kelly, M.; Hooper, J.N. Global diversity of sponges (Porifera). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado, M.; Aguilar, R.; Bannister, R.; Bell, J.; Conway, J.; Dayton, P.; Diaz, C.; Gutt, J.; Kelly, M.; Kenchington, E.; et al. Sponge Grounds as Key Marine Habitats: A Synthetic Review of Types, Structure, Functional Roles, and Conservation Concerns. In Marine Animal Forests: The Ecology of Benthic Biodiversity Hotspots; Rossi, S., Bramanti, L., Gori, A., Saco del Valle, C.O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 145–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerovasileiou, V.; Dailianis, T.; Sini, M.; del Mar Otero, M.; Numa, C.; Katsanevakis, S.; Voultsiadou, E. Assessing the regional conservation status of sponges (Porifera): The case of the Aegean ecoregion. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2018, 19, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronzato, R.; Manconi, R. Mediterranean commercial sponges: Over 5000 years of natural history and cultural heritage. Mar. Ecol. 2008, 29, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler IV, M.J.; Behringer, D.C.; Valentine, M.M. Commercial sponge fishery impacts on the population dynamics of sponges in the Florida Keys, FL, USA. Fish. Res. 2017, 190, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Northcote, P.T.; Webb, V.L.; Mackey, S.; Handley, S.J. Aquaculture trials for the production of biologically active metabolites in the New Zealand sponge Mycale hentscheli (Demospongiae: Poecilosclerida). Aquaculture 2005, 250, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, V.S.; Manzano, G.G.; Clairecynth, C.Y.; Aliño, P.M.; Salvador-Reyes, L.A. Mariculture potential of renieramycin producing philippine blue sponge Xestospongia sp. (Porifera: Haplosclerida). Aquaculture 2019, 502, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Report of the Technical Consultation on International Guidelines for the Management of Deep-Sea Fisheries in the High Seas; Report No. 881; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, E. Global advances in conservation and management of marine ornamental resources. Aquar. Sci. Conserv. 2001, 3, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).