Sustainable Development in Old Communities in China—Using Redesigned Nucleic Acid Testing Booths for Community-Specific Needs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Future Communities and Sustainable Development

2.2. Community Residents’ Needs

2.3. Community Convenience Service Stations

3. Research Methods

- What is it like to live in this community? Are there any disadvantages, and do you have any needs?

- Do you think the community management and public services are comprehensive?

- Do you have any ideas or suggestions about the public services in the community?

- What are the needs and pain points of the residents of the community?

- How are community public services conducted?

- What are the pain points and difficulties in carrying out public services in the community?

- Please talk about the dimensions through which the community design addresses the needs of the residents of the community based on your design experience?

- What are your suggestions for remodeling and designing the unused nucleic acid testing booths in the community?

- How do you think community kiosks should be designed to better serve the community?

- Could you please share your experiences and methods of developing a sustainable community?

4. Qualitative Research Analysis

4.1. Analysis of the Interviews with the Community Residents and Managers

- (1)

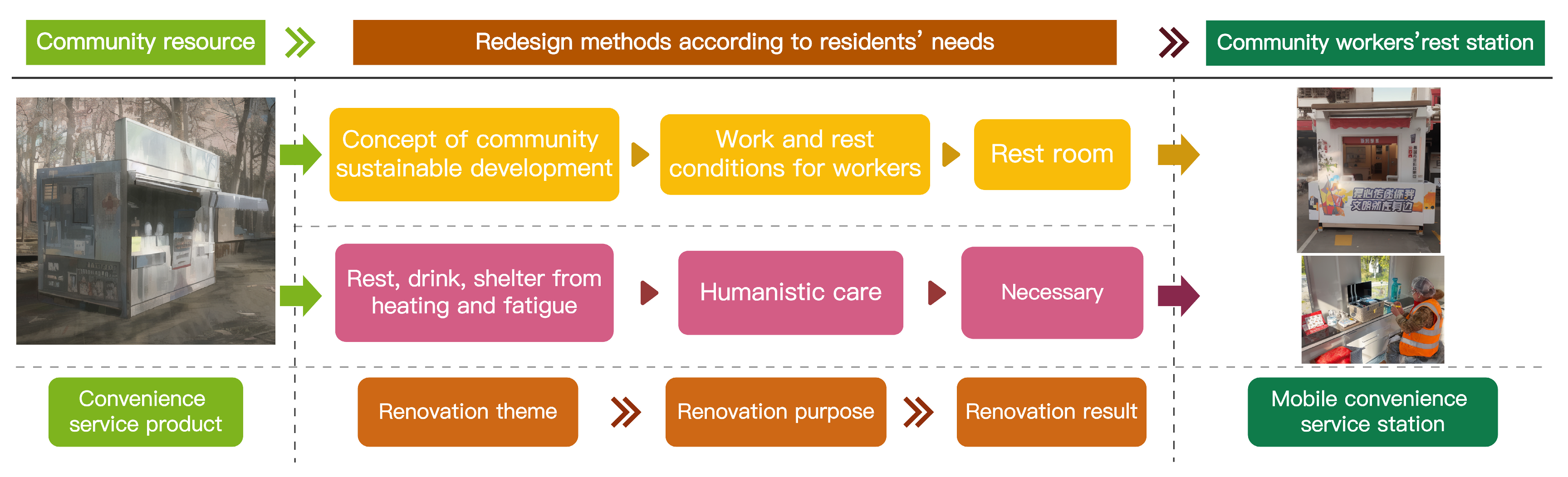

- Humanistic care: Older people aged 65 years noted the lack of channels through which to establish connections with other residents in the community. They often lacked social interactions since they were unfamiliar with other residents, even though they often encountered these residents within the community (A1). This made them feel depressed. At the same time, another older person expressed their concern and need regarding their inability to control their physical functions, namely, urination and excretion, and expressed the hope that the community would find ways to address these physiological needs (A2). The Haibin community has a large number of elderly people, and there is a great need for young people to hang on to them. The Haibin community therefore often organizes activities for university students to visit the elderly (B10). B3 hoped that the community management would pay more attention to the community workers and protect their legitimate rights and interests. Based on this, B3 felt that more concern and care should be given to environmental sanitation workers, cleaning aunts, and security uncles to improve their happiness when working. A14 deemed psychological counseling services to be necessary for community residents to help improve their emotions and alleviate depression since many young workers who had recently entered the workplace were experiencing a significant psychological gap between campus and the workplace. With the current economic recession, the residents of the Bigui Yuan community hoped that they could receive financial management education to increase their financial awareness (A18) as well as reduce the cost of property management and unnecessary services and thereby alleviate the financial burden on families (A15, A16).

- (2)

- Life convenience: The health of community residents cannot be separated from sports and fitness. A13 expressed a desire for communities to have sports activity rooms for residents to use so as to improve their quality of life and physical health. The interactions between community service providers, community residents, and intelligent technologies services have a significant impact on the satisfaction of residents’ need levels [33]. According to A5, having healthcare facilities within a community can greatly improve the convenience of life, as it would remove the need for residents to travel to more distant hospitals and clinics, which thus reduces the amount of time and energy spent on this activity. A10 proposed that communities provide more entertainment facilities for children to play in and experience, as these would improve the connection between the residents and the quality of children’s entertainment. A20 asserted that communities should provide convenient information services, such as community websites, WeChat official accounts, and community bulletin boards. These information facilities should have timely updates to make it easy for residents to access detailed information regarding their community (A20). Volunteer services were identified as a way to improve the quantity and quality of the services provided in a community (A12) and enhance the convenience of life [34]. B10 felt that communities should also have places for residents to relax and have fun so that they can cool off in summer, and in winter, they can bask in the sun. These spaces would also be used for elderly people to play chess, cards, and kung fu and chat, for women to sing, dance, and put on fashion shows, and for children to play and chase around.

- (3)

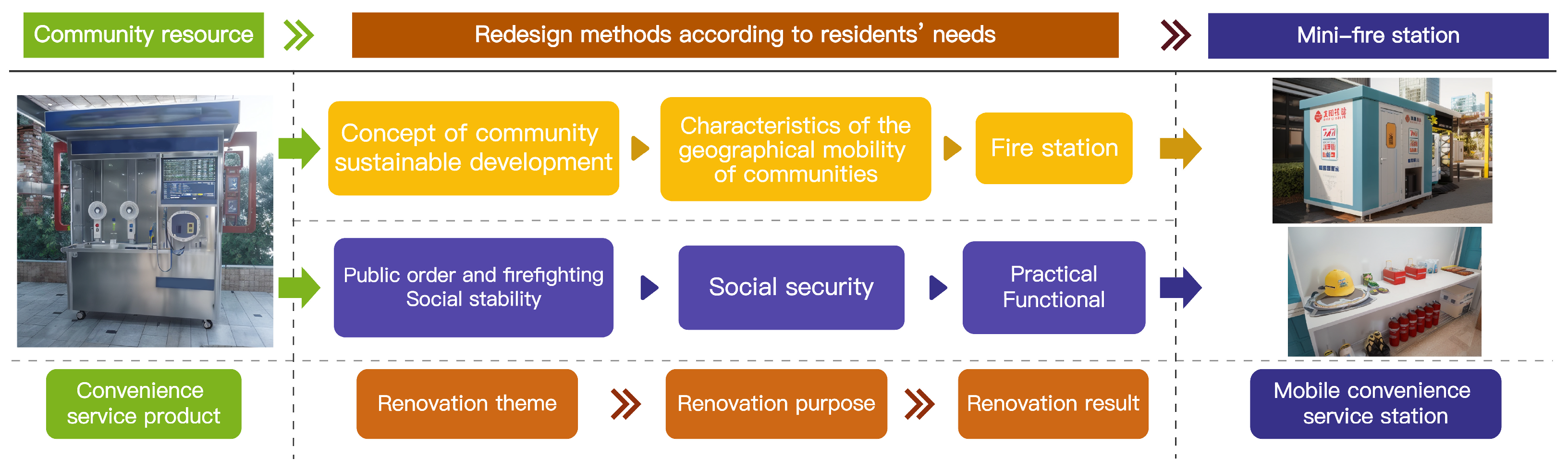

- Community safety: Community security is crucial and a prerequisite for community living (A7). Community public facilities for fire and disaster prevention should be ready in the event of these emergencies, and community preparedness should be undertaken (A6). Many elderly people and children live in the communities. The public emergency rescue equipment should be used in the case of accidents to reduce risks or harm (A2). Residents of the Changhu Yuan community emphasized that the community needs to maintain a hygienic environment to prevent and control the spread of disease and ensure the health of the residents (A17). A19 was concerned about the public facilities and equipment in his community. He upheld that the community should maintain the facilities and equipment regularly to ensure they are operational and to prevent accidents.

- (4)

- Efficiency of community governance: As a member of the community management staff, B4 affirmed that the establishment of a community service system was very necessary [29], as it could greatly optimize a community’s self-management ability and form a virtuous cycle. She mentioned that the community needs to know the needs of the residents, which can be achieved through resident interviews, literature reviews, and field research. Annual implementation plans can then be developed. Midterm feedback and later reporting would be needed during the mid-stage of activities, and finally, the entire community plan would need to be evaluated [38]. B2 indicated that there were conflicts between residents, and the consequences of these conflicts were uncontrollable. In such situations, mediation was needed to help the community resolve the conflicts and reduce unnecessary harm (B2). At the same time, ways to improve the efficiency of community governance, such as complaint reporting boxes (B4), livelihood micro practical affairs (B4), wish collection boxes (B4), and goodwill boxes (A9), were also mentioned. B4 indicated that, with improvements to the social work service system, the restrictions on community activities would become less over time.

- (5)

- Knowledge sharing: Community knowledge sharing is essential for empowering communities [34]. In the community where A9 lives, the majority of residents are newborns. The other residents expressed a willingness to establish children’s bookstores in the community so that residents could take their children to read shared books in their free time, thereby building a platform for community knowledge sharing and a learning-oriented community, which draws close to developing a sustainable community [27,50]. The popularization and promotion of knowledge of law is also necessary. In a modern civilized society, the promotion of legal awareness is becoming increasingly important. The establishment and improvement of a community system cannot be separated from improvements in legal awareness among residents (A4). Student tutoring (A9) and the study of basic skills by children (A8) are also needed.

- (6)

- Cultural sustainability: The education levels of the residents in the different communities varied significantly. Cultural sustainability plays a significant role in the sustainable development of communities (B4). It can improve residents’ innovation abilities, humanistic literacy, moral character, ideological depth, spiritual strength, and community cohesion [38]. It can further inspire residents to spontaneously organize and develop communities [30]. Improvements in community quality and culture contribute to the sustainable development and external image of the community, thereby reducing contradictions and conflicts among residents (A12, A13). A9 had high requirements for self-improvement. These included appearance, temperament, social interactions between neighbors, and the improvement of family parent–child relationships. Community manager B9 thought that the cultural atmosphere of a community could also be changed through design, such as changing the visual effects of some small spaces. The cultural atmosphere of a community can be created through colors, graphics, plants, and even artworks, such as sculptures (B9).

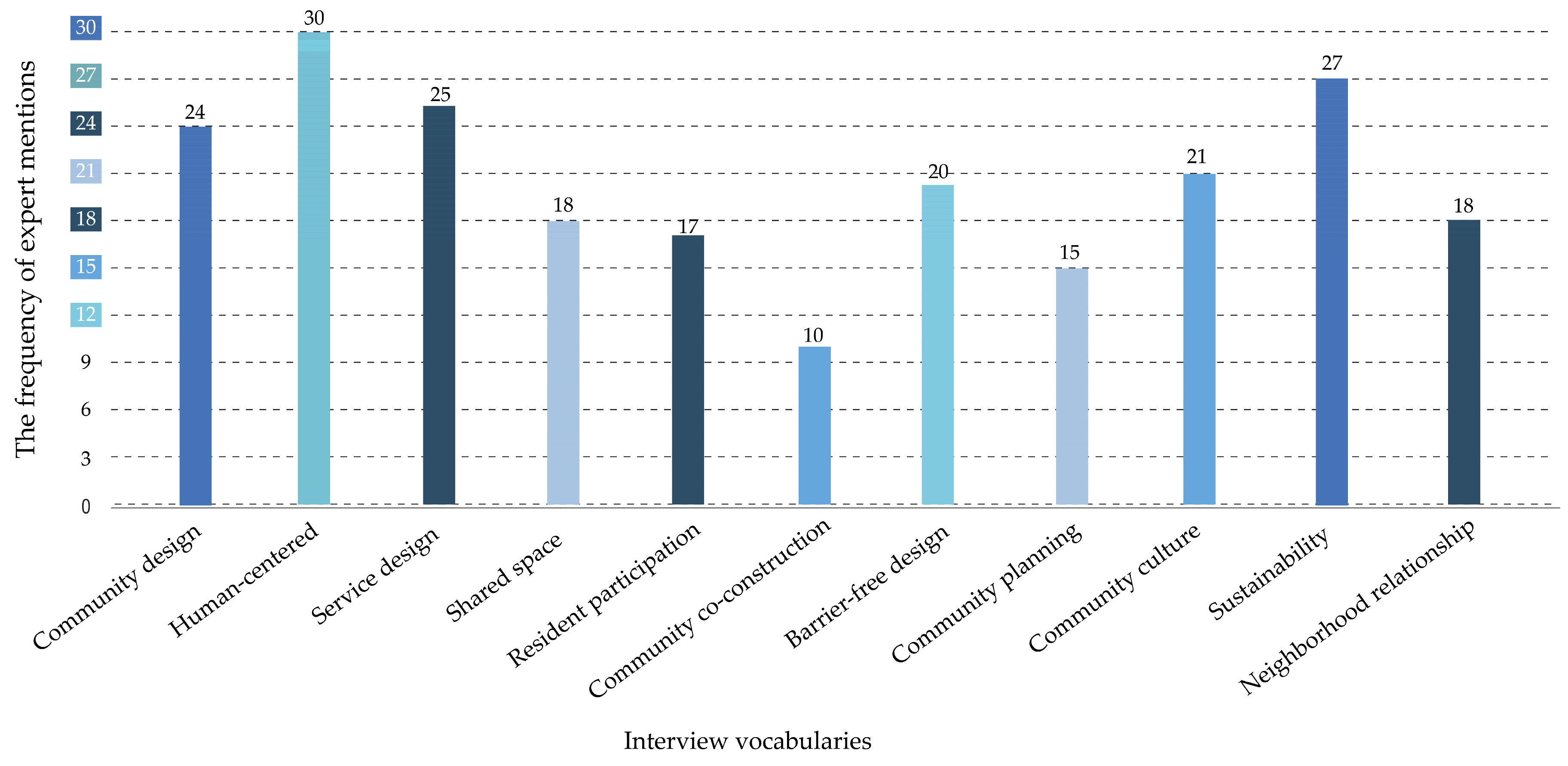

4.2. Community Designers and Specialists Analysis

- (1)

- Addressing the needs of residents: C1 asserted that the renovation of the unused nucleic acid sampling kiosks in a community necessitated conducting a large number of social interviews with the residents in the community and listening to their feedback. The residents’ opinions and demands regarding the existing environment, the management of the hardware in the district, and the residents’ behaviors and physical conditions need to be understood. In addition, the cultural atmosphere of the community can be changed through some design methods, such as changing the visual effects of the environment through the use of color, graphics, plants, and even art, such as sculptures. C4 and C5 emphasized that the community should pay attention to the social value needs of the elderly. They felt that the energy of middle-aged people needed to be utilized, and by providing them with venues and spaces, they could participate fully in helping the elderly with leisure activities in their spare time. They could also be organized to carry out some public welfare activities. The sense of public welfare among the older generation is usually weaker, so this is one way to spread the idea of public welfare.

- (2)

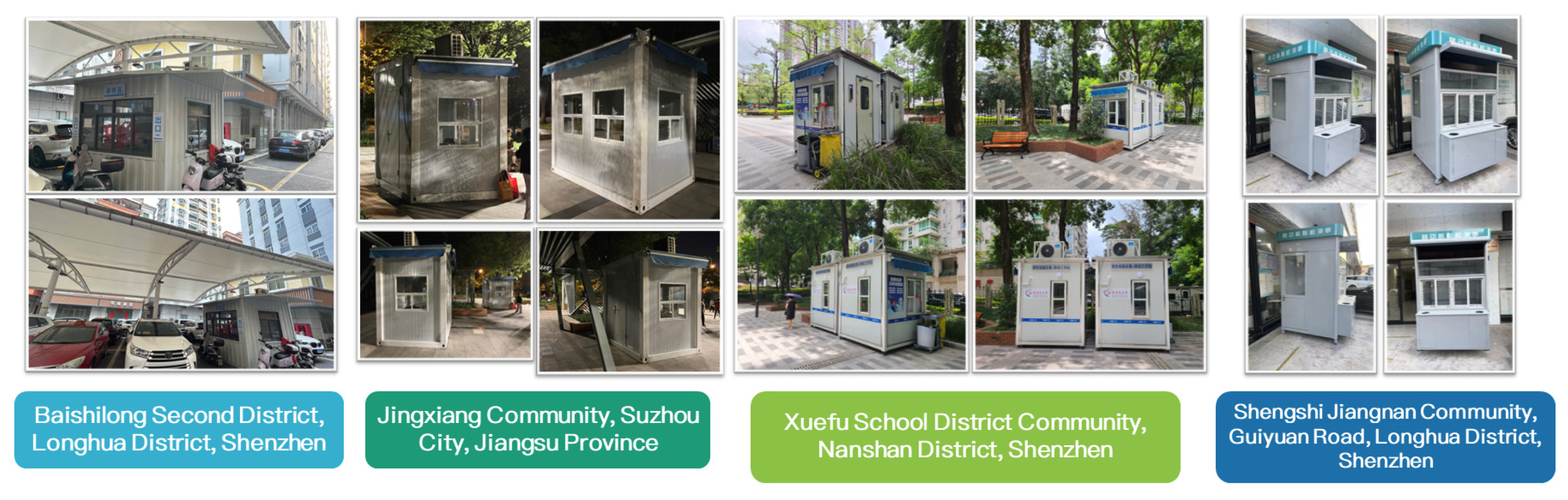

- Nucleic Acid Testing Booths Renovation: C2 and C3 emphasized the need to renovate the unused nucleic acid testing booths in the communities and to provide data support. The transformation of the unused community nucleic acid testing booths into convenient service stations should focus on the needs of the residents in the community and be planned and designed in a coordinated manner with multiple departments, organizations, and properties. The transformation of the unused community nucleic acid testing booths could be piloted as multifunctional space conversions, health and well-being services, community interaction spaces, sustainable development, cultural and artistic spaces, education and training centers, and green leisure spaces.

- (3)

- Community Planning: C6 indicated that an excellent community planning program could meet the various needs of residents, provide a good living environment and social services, promote communication and interaction among residents, and enhance community cohesion and a sense of belonging. At the same time, managers of community planning programs can utilize resources rationally, improve the sustainability of the community, and promote the overall development of the city. C10 and C12 felt that community design is very difficult. Intricate social environments and cultural relationships allow different communities and regions to adopt different solutions.

- (4)

- Community Design: C7 and C8 noted that social and cultural attributes need to be strengthened most in community design, and the starting point for strengthening social attributes is the restoration of neighborhood relations. In contemporary urban life, the chances of neighbors getting to know one another are diminishing. First of all, community design is a human-centered design, so the users’ habits should be considered first. Designers should be fully aware of the users’ preferences and habits so that they can develop the basis of the design scheme and create adaptive designs. Second, for the dimension of public activity areas, designers should pay attention to the construction of a sense of place. Starting with human behavior, the layout is developed according to the nature and scale of the space. Finally, designers should consider the sustainable development of the community, collect user feedback, and then update the design. C9 and C11 noted that the layout of the convenience service stations should be concise and clear, so that residents can find the corresponding service areas easily. This requires designers to take into account accessibility and to provide people with special needs with convenient access through the design.

5. Design Case Analysis

5.1. Renovation Design: Community Workers’ Rest Stations

5.2. Renovation Design: Fever Clinics

5.3. Renovation Design: Mini-Fire Stations

5.4. Renovation Design: People’s Livelihood Liaison Stations

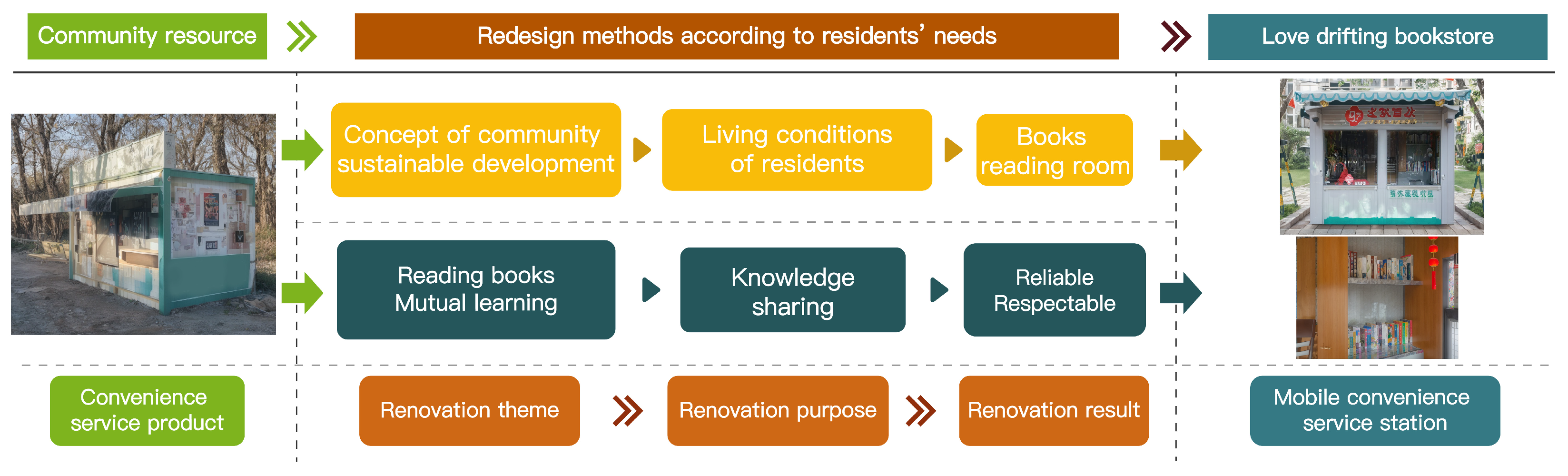

5.5. Renovation Design: Love Drifting Bookstores

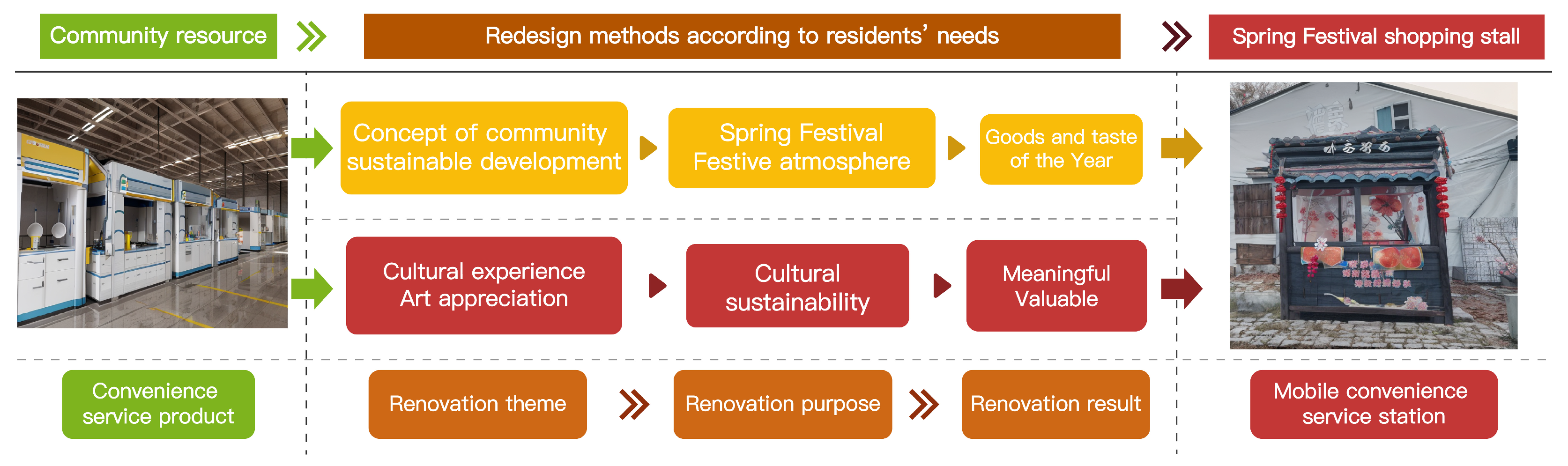

5.6. Renovation Design: Spring Festival Shopping Stalls

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Goals. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Lee, K.-H.; Noh, J.; Khim, J.S. The Blue Economy and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals: Challenges and opportunities. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Goals. 2023. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/ (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Roseland, M. Sustainable community development: Integrating environmental, economic, and social objectives. Prog. Plan. 2000, 54, 73–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H. Sustainable Communities, 1st ed.; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/1562958/sustainable-communities-the-potential-for-econeighbourhoods-pdf (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM). The Egan Review: Skills for Sustainable Communities; Office of the Deputy Prime Minister: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.L. Developing an evaluation framework for community empowerment from the viewpoint of sustainable communities: A study on the experiences of Tainan City and Tainan County. J. Hous. Stud. 2007, 16, 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Balta-Ozkan, N.; Boteler, B.; Amerighi, O. European smart home market development: Public views on technical and economic aspects across the United Kingdom, Germany and Italy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watini, S.; Nurhaeni, T.; Meria, L. Development of Village Office Service Models to Community Based on Mobile Computing. Int. J. Cyber IT Serv. Manag. 2021, 1, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinisch, C.; Kofler, M.; Iglesias, F.; Kastner, W. ThinkHome Energy Efficiency in Future Smart Homes. Eurasip J. Embed. Syst. 2011, 2011, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M. Strategic decisions on urban built environment to pandemics in Turkey: Lessons from COVID-19. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuxi has built 1,519 medical service centers for the people. Available online: https://www.zgjssw.gov.cn/shixianchuanzhen/wuxi/202212/t20221219_7782690.shtml (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- What the 15-minute nucleic acid sampling circle will bring. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1733160665617490777&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- How to reuse the massive resources of nucleic acid sampling kiosk Transformation? Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1753098087538129977&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Shenzhen Daily. Available online: https://www.sz.gov.cn/en_szgov/news/latest/content/post_10349135.html (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Inayatullah, S. Six pillars: Futures thinking for transforming. Foresight 2008, 10, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandra, C.; Wyborn, C.; Roldan, C.M.; van Kerkhoff, L. Futures-thinking: Concepts, methods and capacities for adaptive governance. In Handbook on Adaptive Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham Glos, UK, 2023; pp. 76–98. ISBN 9781800888234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D. Community and Sustainable Development: Participation in the Future; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elsbach, K.D.; Stigliani, I. Design Thinking and Organizational Culture: A Review and Framework for Future Research. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2274–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, R.V.V. The future workshop: Democratic problem solving. Econ. Anal. Work. Pap. 2006, 5, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Dator, J. What futures studies is, and is not. In Jim Dator: A Noticer in Time; Selected work, 1967-2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B. Community-Based Participatory Research Contributions to Intervention Research: The Intersection of Science and Practice to Improve Health Equity. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H. Towards New Community: Theory and Method of Integral Construction of Urban Residential Community; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, J.; Corbett, M. Designing Sustainable Communities: Learning from Village Homes; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhah, H.A.; Bin Redzuan, M. The Role of NGOs in Promoting Empowerment for Sustainable Community Development. J. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 30, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AtKisson, A. Developing indicators of sustainable community: Lessons from sustainable Seattle. In The Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Cities; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 352–363. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C.; Sackney, L. Profound Improvement: Building Capacity for a Learning Community; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011; ISBN 9026516347. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, P.M. Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.M.; Lang, W. Collaborative workshop and community participation: A new approach to urban regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Plan. Theory Pr. 2004, 5, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhou, Y. Research on human–AI co-creation based on reflective design practice. CCF Trans. Pervasive Comput. Interact. 2020, 2, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.J.; Ricotta, D.N.; Freed, J.; Smith, C.C.; Huang, G.C. Adapting Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a Framework for Resident Wellness. Teach. Learn. Med. 2019, 31, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.K.; Balaji, M.S.; Sadeque, S.; Nguyen, B.; Melewar, T.C. Constituents and consequences of smart customer experience in retailing. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 124, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverack, G. Improving health outcomes through community empowerment: A review of the literature. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2006, 24(1), 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, A.; Matsumoto, H.; Takaoka, M.; Kugai, H.; Suzuki, M.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Educational Program for Promoting Collaboration Between Community Care Professionals and Convenience Stores. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L. User experience: The motivation and promotion of livestreaming innovation in Chinese marketing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Washington, DC, USA, 24–29 July 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 344–361. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, A.; Matsumoto, H.; Takaoka, M.; Kugai, H.; Suzuki, M.; Murata, S.; Miyahara, M.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Building Relationships between Community Care Professionals and Convenience Stores in Japan: Community-Based Participatory Research. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2023, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan, G.; Newton, D.; Wallis, E.; Winterton, J.; Winterton, R. Adult and Community Learning: What? In Why? Who? Where? Department for Education and Skills: London, UK, 2001. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/4154415.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Mason, R.B.; Ngobese, N.; Maharaj, M. Perceptions of service provided by South African police service community service centres. Police Pr. Res. 2021, 22, 1259–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.R.; Matzen, D.; McAloone, T.C.; Evans, S. Strategies for designing and developing services for manufacturing firms. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 3, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 12th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 0-13-145757-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lockton, D. Design with Intent: A Design Pattern Toolkit for Environmental and Social Behaviour Change. Doctoral Dissertation, Brunel University School of Engineering and Design PhD Theses, London, UK, 2013. Available online: http://bura.brunel.ac.uk/handle/2438/7546 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Ho, S.S.; Sung, T.J. The development of academic research in service design: A meta-analysis. J. Des. 2014, 19, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassan, R.K.; Nketiah-Amponsah, E.; Arhinful, D.K. Design and implementation of community engagement interventions towards healthcare quality improvement in Ghana: A methodological approach. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.W. Research on the Theory and Practice of Urban Community Construction of the Communist Party of China. Doctoral Dissertation, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2010. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFD0911&filename=2010115982.nh (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Gregory, S.A. The Design Method; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 1489961690. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Terken, J. Design Process. In Automotive Interaction Design: From Theory to Practice; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 165–179. ISBN 978-981-19-3447-6. [Google Scholar]

- Goldim, J.R.; Fernandes, M.S. Selection of Research Subjects: Methodological and Ethical Issues. In Handbook of Bioethical Decisions. Volume II: Scientific Integrity and Institutional Ethics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, L.; Bolam, R.; McMahon, A.; Wallace, M.; Thomas, S. Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature. J. Educ. Change 2006, 7, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visual Suzhou. 2023. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/ldjbQKLv_6sKzVtK-mb0jA (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Joseph, L.; Bates, A. What is an “Ecovillage”? Communities 2003, 117, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nedaei, M.; Jacoby, A. Design-Driven Conflicts: A Design-Oriented Methodology for Mindset and Paradigm Shifts in Human Social Systems. Systems 2023, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Gender | Age | Community | Residence Time (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Male | 65 | Binhai | 20 or above |

| A2 | Male | 60 | Binhai | 15–19 |

| A3 | Male | 58 | Jinlong | 10–14 |

| A4 | Male | 45 | Jinlong | 7–9 |

| A5 | Female | 55 | Binhai | 7–9 |

| A6 | Female | 50 | Binhai | 1–3 |

| A7 | Female | 52 | Jinlong | 4–6 |

| A8 | Female | 45 | Jinlong | 7–9 |

| A9 | Female | 32 | Xuelin Yayuan | 4–6 |

| A10 | Female | 13 | Binhai | 4–6 |

| A11 | Female | 16 | Xuelin Yayuan | 7–9 |

| A12 | Female | 22 | Xuelin Yayuan | 1–3 |

| A13 | Male | 24 | Haibin | 4–6 |

| A14 | Male | 24 | Xiaomeisha Xinju | 4–6 |

| A15 | Male | 50 | Bigui Yuan | 7–9 |

| A16 | Female | 48 | Bigui Yuan | 7–9 |

| A17 | Female | 52 | Changhu Yuan | 7–9 |

| A18 | Male | 17 | Bigui Yuan | 4–6 |

| A19 | Male | 24 | Dongtian | 4–6 |

| A20 | Male | 24 | Yanta | 1–3 |

| No. | Gender | Age | Community | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | Male | 50 | Binhai | Community security captain |

| B2 | Male | 45 | Jinlong | Community security |

| B3 | Male | 40 | Jinlong | Community security |

| B4 | Female | 28 | Binhai | Community management director |

| B5 | Female | 24 | Binhai | Community social worker |

| B6 | Female | 24 | Binhai | Community social worker |

| B7 | Female | 23 | Jinlong | Community social worker |

| B8 | Female | 22 | Jinlong | Community social worker |

| B9 | Female | 25 | Haibin | Community social worker |

| B10 | Female | 40 | Haibin | Community director |

| No. | Gender | Research Area | Affiliated Unit | Research Experiences (Years) | Occupation | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Male | Community design | Wuhan University | 35 | Professor | 65 |

| C2 | Female | Interior design, environmental design | Wuhan University | 30 | Professor | 55 |

| C3 | Female | Design education | Shenzhen University | 26 | Professor | 55 |

| C4 | Male | Service design | Shenzhen University | 22 | Associate professor | 50 |

| C5 | Male | Community planning design | Nanjing Tech University | 18–20 | Professor | 47 |

| C6 | Male | Service design | Guangdong University of Finance & Economics | 12–14 | Associate professor | 37 |

| C7 | Male | Community residential program design | East China Architectural Design 8 Research Institute Co., Ltd. (ECADI) | 16 | Senior architect | 38 |

| C8 | Male | Residential and recreational building design | ECADI | 10 | Intermediate architect | 29 |

| C9 | Male | Urban and rural planning design | Yunnan Urban and Rural Planning and Design Institute | 16 | Senior engineer | 38 |

| C10 | Male | Product design, interaction design | Xiaopeng Motors | 10–12 | Professional designer | 30 |

| C11 | Male | Community design | Ningbo Yongshang Fenghua Culture Media Co. | 18 | Head designer | 40 |

| C12 | Male | Service design, product design | Artop Group | 10–12 | Professional designer | 30 |

| Interviewees | Need | Sustainable Development |

|---|---|---|

| A1, A2, A14, A15, A16, A18 | Social, physical, and psychological counseling, financial management, financial burden | Humanistic care |

| B3, B10 | Lonely elderly people, rest for community workers | |

| A5, A10, A12, A13, A20 | Sports rooms, medical clinics, entertainment venues, information platforms, support services | Life convenience |

| B7, B8, B10 | Leisure and entertainment, express delivery stations, shared piano rooms | |

| A2, A6, A7, A17, A19 | Public security, fire prevention, emergency equipment, health safety, equipment safety | Community safety |

| B1, B2 | Fire stations, shelters | |

| A3, A4, A9 | Donation boxes, livelihood liaison stations | Efficient community governance |

| B2, B4 | Service system, resident mediation, opinion collection boxes | |

| A4, A8, A9 | Children’s libraries, sharing books, knowledge platforms, tutoring | Knowledge sharing |

| B5, B6, B11 | Legal knowledge, resident participation | |

| A1, A6, A12, A13, A17, A20 | Spring Festival shopping stalls, parent–child relationships, cultural festivals | Cultural sustainability |

| B4, B9 | Educational level, cultural atmosphere, community building |

| Interviewees | Opinion | Direction |

|---|---|---|

| C1: Talk to the residents, look around the community, and see what they have to say about the environment. | Pay more attention to the living conditions of the community residents | Address the needs of the community residents |

| C4: Create a sense of community and provide space for public activities. | Meet the social needs of the elderly, provide space for the elderly and children’s outdoor activities, labor needs, sports needs | |

| C5: Ensure that all areas within the community are safe, accessible, and suitable for people of all ages and abilities. | Human-centered design | |

| C2: Transform the community nucleic acid testing booths. | Multifunctional space. Concentration on health and well-being, community interaction spaces, and sustainable development | Nucleic acid testing booth renovation |

| C3: Transformation should focus on the needs of the residents in the community. Multiparty coordination is needed for overall planning. | Culture and art space, education and training center, green leisure space, etc. | |

| C6: Focus on providing convenient and diversified services. | Optimize the community service design | Community planning |

| C10: Think of the nucleic acid sampling kiosk as a space with a constant size, and think about the other uses it can have. | Optimize the community space design | |

| C12: Encourage community participation, including decision-making, project planning, and problem-solving. | Encourage the active participation of residents | |

| C7: Social and cultural attributes need to be strengthened most. Start with the restoration of the neighborhood relationships. | Enhance community interaction and socializing | Community design |

| C8: Start with the dimension of users’ habits. Design with a full understanding of the users’ preferences and habits. | Study residents’ living habits and behavior patterns | |

| C9: The purpose is to create a harmonious living environment and to motivate communication among human beings and the environment through the reasonable organization of the space. | Attach importance to communication among communities | |

| C11: Create a livable and safe environment. The needs of the residents need to be considered during construction. | Consider safety and livability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Luo, W.; Chen, J.; Lin, R.; Lyu, Y. Sustainable Development in Old Communities in China—Using Redesigned Nucleic Acid Testing Booths for Community-Specific Needs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031099

Wu J, Luo W, Chen J, Lin R, Lyu Y. Sustainable Development in Old Communities in China—Using Redesigned Nucleic Acid Testing Booths for Community-Specific Needs. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031099

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jun, Wenzhe Luo, Jiaru Chen, Rungtai Lin, and Yanru Lyu. 2024. "Sustainable Development in Old Communities in China—Using Redesigned Nucleic Acid Testing Booths for Community-Specific Needs" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031099

APA StyleWu, J., Luo, W., Chen, J., Lin, R., & Lyu, Y. (2024). Sustainable Development in Old Communities in China—Using Redesigned Nucleic Acid Testing Booths for Community-Specific Needs. Sustainability, 16(3), 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031099