Factors Influencing Tourists’ Intention and Behavior toward Tourism Waste Classification: A Case Study of the West Lake Scenic Spot in Hangzhou, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theory Background

2.1.1. The Theory of Planned Behavior

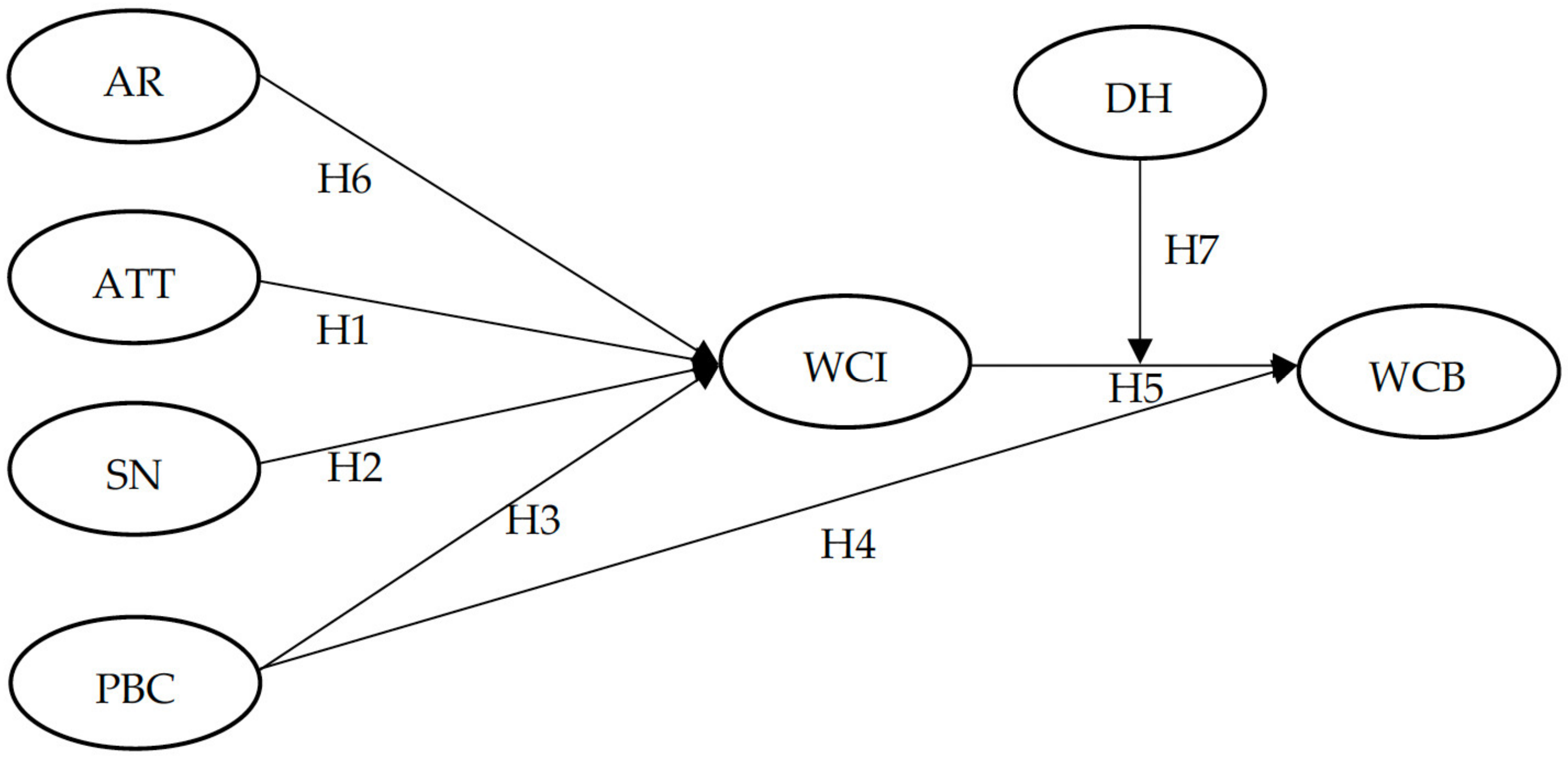

2.1.2. The Extended TPB-AR-DH Model

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Attitude, Subjective Norm, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Tourists’ Waste Classification Intention/Actual Behavior

2.2.2. Ascription of Responsibility and Tourists’ Waste Classification Intention

2.2.3. Moderating Role of the Daily Habit of Waste Classification

3. Methodology

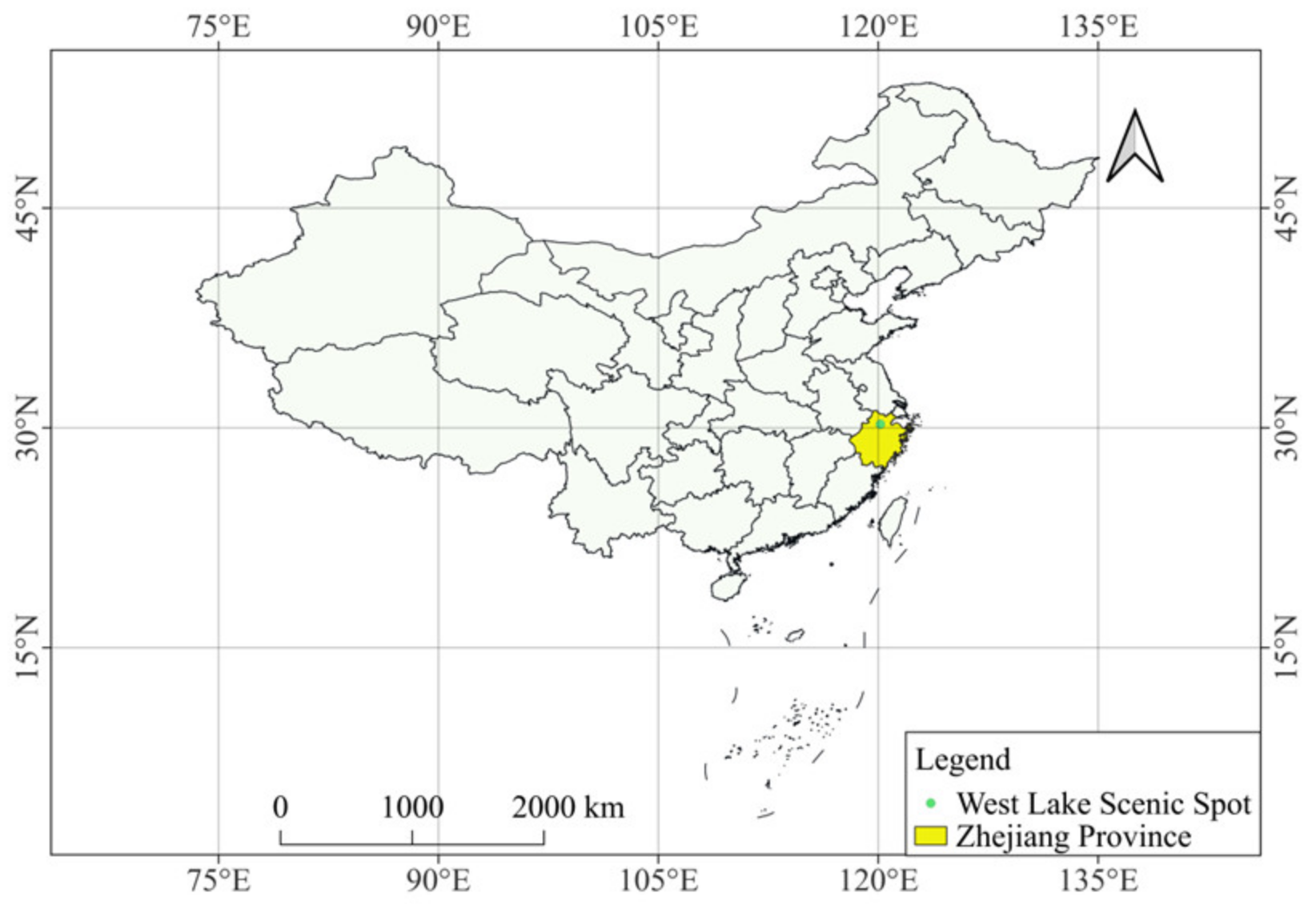

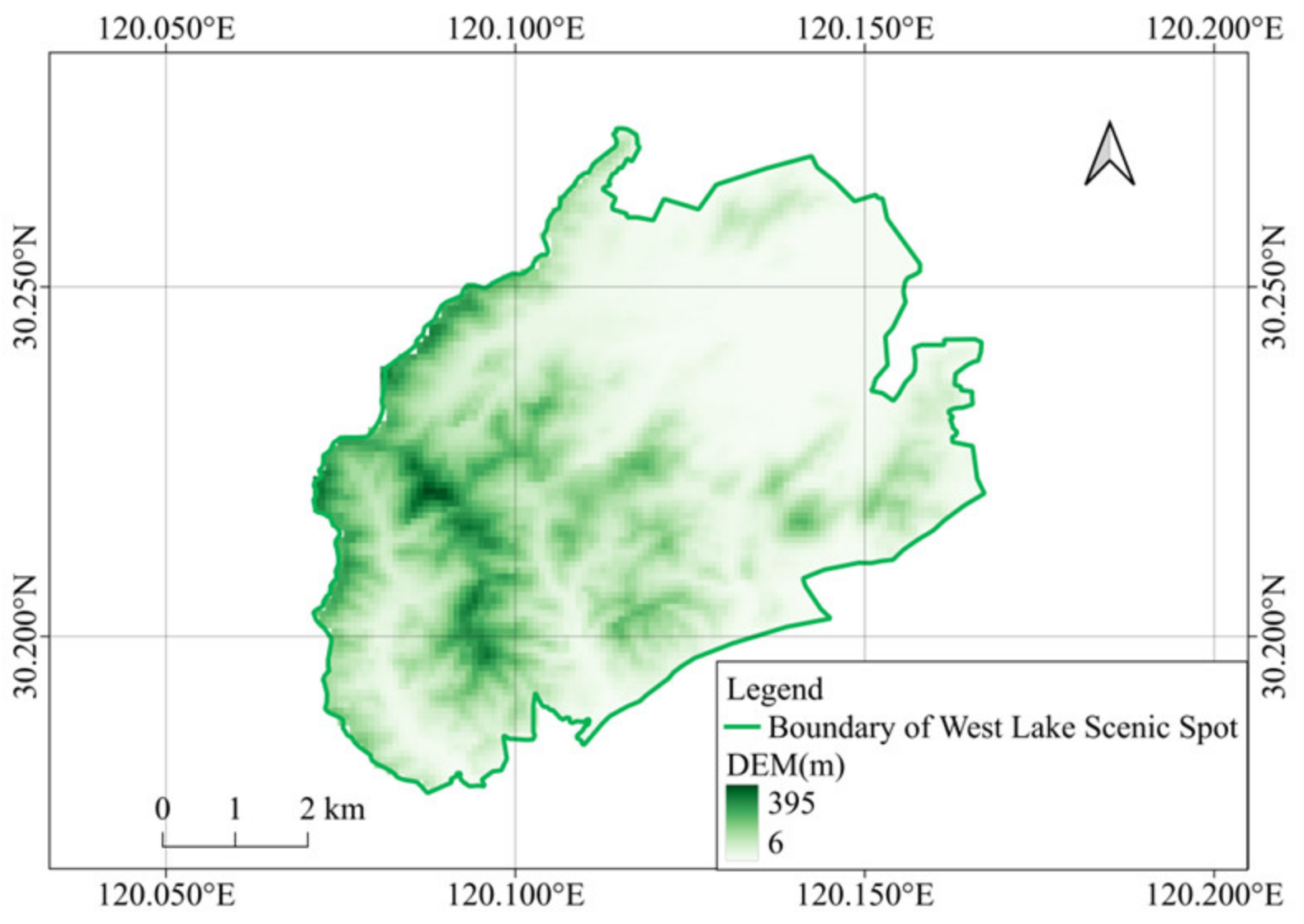

3.1. The Background of the Study Case

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

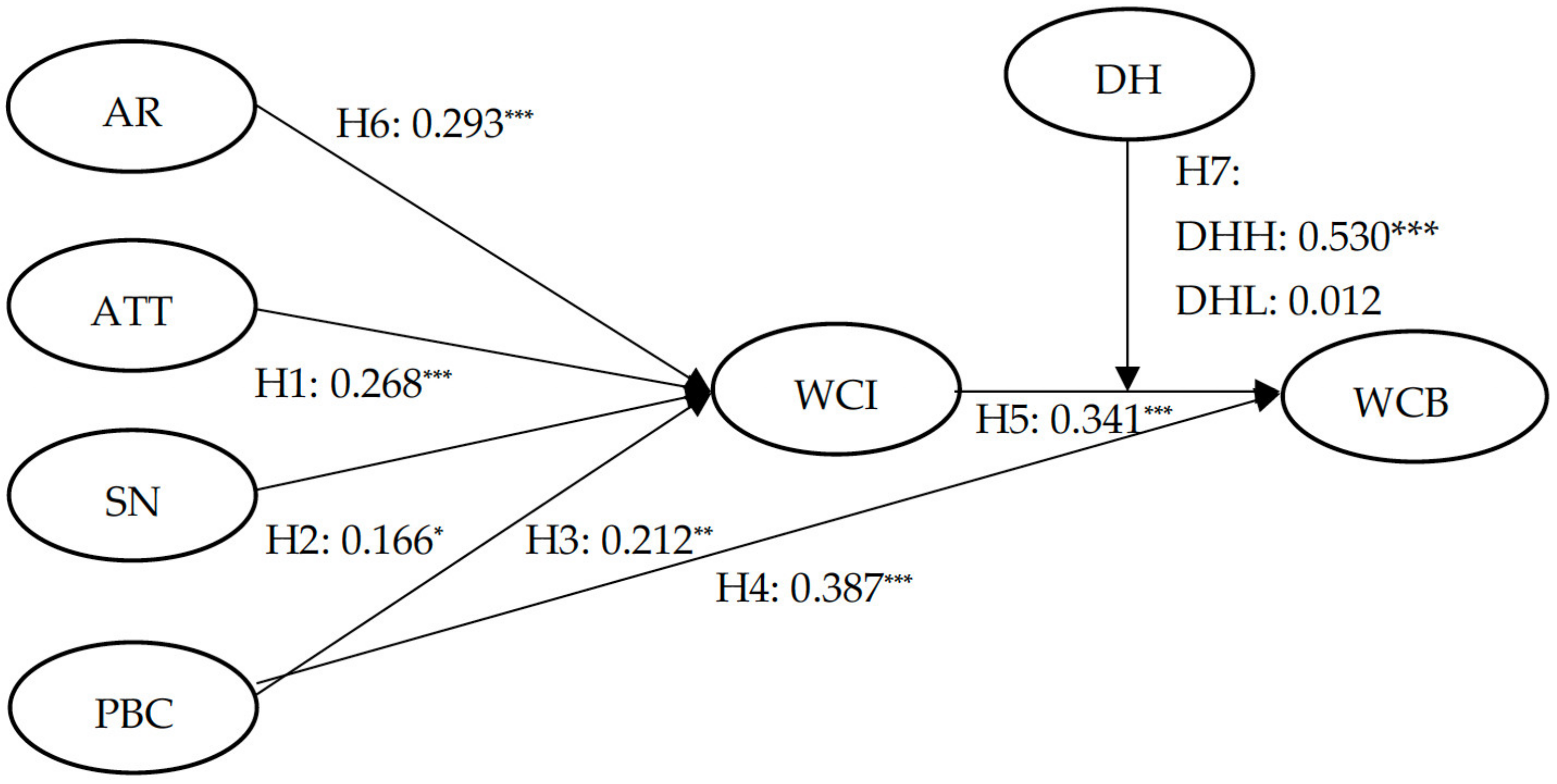

4.3. Structural Model Evaluation

4.4. The Mediating Test of Waste Classification Intention

4.5. The Moderating Test of the Daily Habit of Waste Classification

5. Discussion

5.1. Factors Influencing Tourists’ Waste Classification Intention

5.2. Factors Influencing Tourists’ Waste Classification Behavior

5.3. The Moderating Role of the Daily Habit of Waste Classification

5.4. Research Significance

5.4.1. Theoretical Significance

5.4.2. Practical Significance

5.5. Research Limitations and Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Chu, G.; Yang, J.; Yu, P. Factors influencing tourists’ litter management behavior in mountainous tourism areas in China. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabane, W.; Nassour, A.; Bartnik, S.; Bünemann, A.; Nelles, M. Shifting towards sustainable tourism: Organizational and financial scenarios for solid waste management in tourism destinations in Tunisia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, E.; Navia, R. Waste management in touristic regions. Waste Manag. Res. 2015, 33, 593–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.C.; Rodic, L.; Modak, P.; Soos, R.; Rogero, A.C.; Velis, C.; Iyer, M.; Simonett, O. Global Waste Management Outlook; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Yue, G.; Xinquan, G.; Yingmei, Y.; Hua, C.; Jianping, H.; Jian, Z. Exploring the residents’ intention to separate MSW in Beijing and understanding the reasons: An explanation by extended VBN theory. Sust. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, W. Constructing an effective prevention mechanism for MSW lifecycle using failure mode and effects analysis. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaeta Bernardi, A.; Parente, V. Organic municipal solid waste (MSW) as feedstock for biodiesel production: A financial feasibility analysis. Renew. Energy. 2016, 86, 1422–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge-Zhang, S.; Cai, T.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Mu, P.; Cui, J. Investigation and Suggestions regarding Residents’ Understanding of Waste Classification in Chinese Prefecture-Level Cities—A Case Study of Maanshan City, Anhui Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yu, Z.; Fukuda, H. Extended theory of planned behavior for predicting the willingness to pay for municipal solid waste management in Beijing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knussen, C.; Yule, F. “I’m not in the habit of recycling” The role of habitual behavior in the disposal of household waste. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnes, S.; Grün, B.; Dolnicar, S. Habit drives sustainable tourist behaviour. Ann. Touris. Res. 2022, 92, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Yu, P.; Chu, G. What influences tourists’ intention to participate in the Zero Litter Initiative in mountainous tourism areas: A case study of Huangshan National Park, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaske, J.J.; Jacobs, M.H.; Espinosa, T.K. Carbon footprint mitigation on vacation: A norm activation model. J. Outdo. Recreat. Tour. Res. Plan. 2015, 11, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansser, O.A.; Reich, C.S. Influence of the new ecological paradigm (NEP) and environmental concerns on pro-environmental behavioral intention based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 134629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, H. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to understand individual’s energy saving behavior in workplaces. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Extending the theory of planned behavior model to explain people’s energy savings and carbon reduction behavioral intentions to mitigate climate change in Taiwan–moral obligation matters. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M. E-waste recycling behaviour: An integration of recycling habits into the theory of planned behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, T.M.; Iris, K.; Wang, L.; Hsu, S.C.; Tsang, D.C.; Li, C.; Yeung, T.L.; Zhang, R.; Poon, C.S. Extended theory of planned behaviour for promoting construction waste recycling in Hong Kong. Waste Manag. 2019, 83, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Liu, Y.; Mo, Z. Moral norm is the key: An extension of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) on Chinese consumers’ green purchase intention. Asia Pac. J. Market. Logist. 2020, 32, 1823–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Mulgrew, K.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Schaffer, V.; Hoberg, R. Theory of planned behaviour: Predicting tourists’ pro-environmental intentions after a humpback whale encounter. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A.N.; Adelazim Ahmed, T.S.; Alotaibi, E.K.; Abbas, I.S.; Ali, E.R.; Shaker, E.S.M. The Role of Awareness of Consequences in Predicting the Local Tourists’ Plastic Waste Reduction Behavioral Intention: The Extension of Planned Behavior Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chua, B.-L.; Hyun, S.S. Eliciting customers’ waste reduction and water saving behaviors at a hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ji, C.; He, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Tourists’ waste reduction behavioral intentions at tourist destinations: An integrative research framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M.; Wei, W. The role of social capital in predicting tourists’ waste sorting intentions in rural destinations: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulker Demirel, E.; Ciftci, G. A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soorani, F.; Ahmadvand, M. Determinants of consumers’ food management behavior: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Waste Manag. 2019, 98, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.; Tang, D.; Wu, G.; Lan, J. Understanding intention and behavior toward sustainable usage of bike sharing by extending the theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Hu, H.; Yu, P. The influence of environmental background on tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviour. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P.; Hu, H. The theory of planned behavior as a model for understanding tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors: The moderating role of environmental interpretations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.F.; Malesios, C. Extending the theory of planned behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, F.; Daud, D.; Weng Wai, C.; Jiram, W.R.A. Waste separation at source behaviour among Malaysian households: The Theory of Planned Behaviour with moral norm. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Youth travelers and waste reduction behaviors while traveling to tourist destinations. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lai, K.H.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z. From intention to action: How do personal attitudes, facilities accessibility, and government stimulus matter for household waste sorting? J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.T.B.; Zhu, D.; Liu, C.; Kim, P.B. A meta-analysis of antecedents of pro-environmental behavioral intention of tourists and hospitality consumers. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Zhou, K. From intention to behavior: Comprehending residents’ waste sorting intention and behavior formation process. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: Compared analysis of first-time and repeat tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Huang, L.; Whitmarsh, L. Home and away: Cross-contextual consistency in tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1443–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Young, R. Promoting conservation behavior in shared spaces: The role of energy monitors. J. Environ. Syst. 1989, 19, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Verplanken, B.; Aarts, H. Habit, attitude, and planned behaviour: Is habit an empty construct or an interesting case of goal-directed automaticity? Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 10, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Neal, D.T. The habitual consumer. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.; Gardner, B. Promoting habit formation. Health Psychol. Rev. 2013, 7, S137–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Shaw, G.; Coles, T.; Prillwitz, J. ‘A holiday is a holiday’: Practicing sustainability, home and away. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. Tourists’ perception of international air travel’s impact on the global climate and potential climate change policies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Ma, E.; Qu, H.; Ryan, B. Daily green behavior as an antecedent and a moderator for visitors’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1390–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limayem, M.; Hirt, S.G.; Cheung, C.M. How habit limits the predictive power of intention: The case of information systems continuance. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, M.R. Diagnosing measurement equivalence in cross-national research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1995, 26, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Martet. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Weitzman, R. The twenty-seven per cent rule. Ann. Math. Statist. 1964, 35, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Peterson, R.A.; Brown, S.P. Structural equation modeling in marketing: Some practical reminders. J. Martet. Theory Pract. 2008, 16, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Items and Sources |

|---|---|

| ATT | Attitude toward the behavior [1,16,42]. |

| ATT1 | I think it is worthwhile for tourists to classify waste in West Lake. |

| ATT2 | I think it is wise for tourists to classify waste in West Lake. |

| ATT3 | I think it is beneficial for tourists to classify waste in West Lake. |

| SN | Subjective norm [1,16,42]. |

| SN1 | People who are important to me agree with me about classifying waste in West Lake. |

| SN2 | People who are important to me want me to classify waste in West Lake. |

| SN3 | People who are important to me think I should classify waste in West Lake. |

| PBC | Perceived behavioral control [1,16,42]. |

| PBC1 | It is easy to classify waste for me in West Lake. |

| PBC2 | I had the time and ability to classify waste in West Lake. |

| PBC3 | It is convenient to classify waste for me in West Lake. |

| AR | Ascription of responsibility [38,39,41]. |

| AR1 | I have the responsibility to promote resource recycling and environmental protection through waste classification in West Lake. |

| AR2 | I have the responsibility to relieve the pressure on sanitation workers through waste classification in West Lake. |

| AR3 | I have the responsibility to protect the sanitation of West Lake through waste classification. |

| DH | Daily habit of waste classification [10,52]. |

| DH1 | I have the habit of classifying waste in my daily life. |

| DH2 | I have paid attention to waste classification policies in my daily life. |

| DH3 | I have learned about the knowledge of waste classification in my daily life. |

| WCI | Waste classification intention [16,39]. |

| WCI1 | I am willing to abide by the waste classification policy in West Lake. |

| WCI2 | I am willing to persuade travel companions to classify their waste in West Lake. |

| WCI3 | I am willing to learn about waste classification in West Lake. |

| WCB | Waste classification behavior [16,39]. |

| WCB1 | I classified waste in West Lake. |

| WCB2 | I persuaded your travel companions to classify their waste at West Lake. |

| WCB3 | I learned about waste classification in West Lake. |

| Variable | n | % | Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age | ||||

| Male | 186 | 48.69 | <17 | 8 | 2.09 |

| Female | 196 | 51.31 | 18–30 | 254 | 66.49 |

| Education Level | 31–45 | 88 | 23.04 | ||

| Less than High School | 32 | 8.38 | 46–60 | 31 | 8.12 |

| High School/Technical School | 83 | 21.73 | >61 | 1 | 0.26 |

| Undergraduate Degree | 219 | 57.33 | Monthly Income (RMB) | ||

| Postgraduate Degree | 48 | 12.56 | Under 3000 | 174 | 45.55 |

| Does the daily residence have a waste sorting policy? | 3001–6000 | 94 | 24.61 | ||

| Yes | 232 | 60.73 | 6001–9000 | 72 | 18.85 |

| No | 150 | 39.27 | 9000–12,000 | 22 | 5.76 |

| Over 12,000 | 20 | 5.23 |

| Dim | Item Reliability | Composite Reliability | Convergence Validity | Discriminate Validity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std. Loading | CR | AVE | WCB | WCI | AR | DH | PBC | SN | ATT | |

| WCB | 0.626–0.829 | 0.786 | 0.554 | 0.744 | ||||||

| WCI | 0.690–0.714 | 0.744 | 0.492 | 0.609 | 0.701 | |||||

| AR | 0.783–0.838 | 0.859 | 0.67 | 0.360 | 0.697 | 0.819 | ||||

| DH | 0.690–0.856 | 0.834 | 0.629 | 0.526 | 0.558 | 0.508 | 0.793 | |||

| PBC | 0.702–0.823 | 0.820 | 0.604 | 0.592 | 0.601 | 0.531 | 0.557 | 0.777 | ||

| SN | 0.817–0.899 | 0.889 | 0.727 | 0.467 | 0.639 | 0.633 | 0.509 | 0.615 | 0.853 | |

| ATT | 0.856–0.903 | 0.917 | 0.786 | 0.310 | 0.678 | 0.631 | 0.362 | 0.504 | 0.573 | 0.887 |

| Path | Effect | Bias-Corrected Percentile | Percentile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||

| PBC→WCB | Total effects | 0.332 | 0.722 | 0.346 | 0.737 |

| Indirect effects | 0.023 | 0.206 | 0.012 | 0.186 | |

| Direct effects | 0.245 | 0.659 | 0.252 | 0.666 | |

| Paired Differences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev | S.E. Mean | 95% CI of the Difference | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| WCB–WCI | −0.787 | 0.792 | 0.041 | −0.867 | −0.707 | −19.418 | 381 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, P. Factors Influencing Tourists’ Intention and Behavior toward Tourism Waste Classification: A Case Study of the West Lake Scenic Spot in Hangzhou, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031231

Hu H, Zhang Y, Wang C, Yu P. Factors Influencing Tourists’ Intention and Behavior toward Tourism Waste Classification: A Case Study of the West Lake Scenic Spot in Hangzhou, China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031231

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Huan, Yu Zhang, Chang Wang, and Peng Yu. 2024. "Factors Influencing Tourists’ Intention and Behavior toward Tourism Waste Classification: A Case Study of the West Lake Scenic Spot in Hangzhou, China" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031231

APA StyleHu, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, C., & Yu, P. (2024). Factors Influencing Tourists’ Intention and Behavior toward Tourism Waste Classification: A Case Study of the West Lake Scenic Spot in Hangzhou, China. Sustainability, 16(3), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031231