Roles of Urban Green Spaces for Children in High-Density Metropolitan Areas during Pandemics: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Terms and Definitions

2.2. Search Strategy

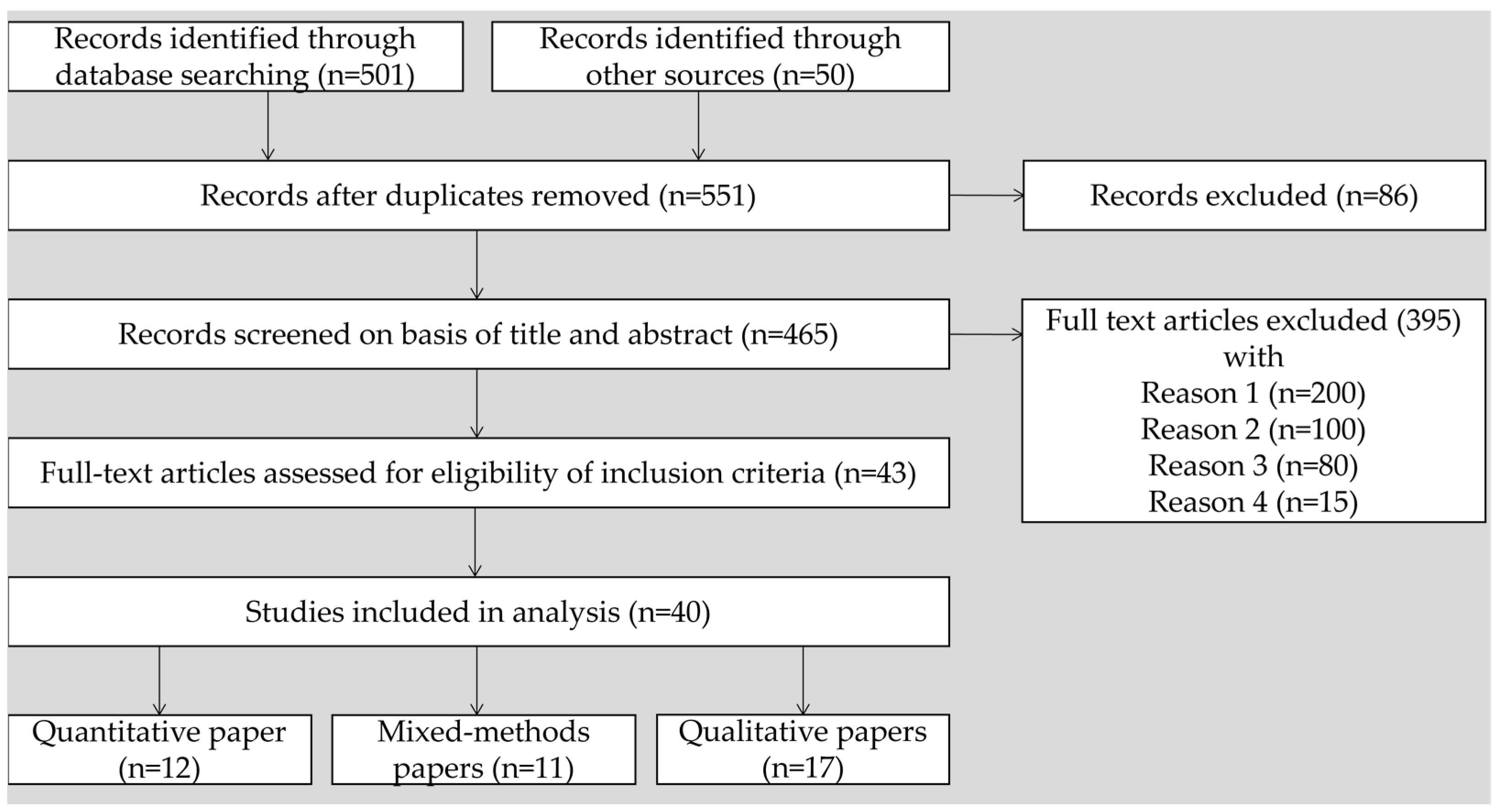

2.3. Screening Process

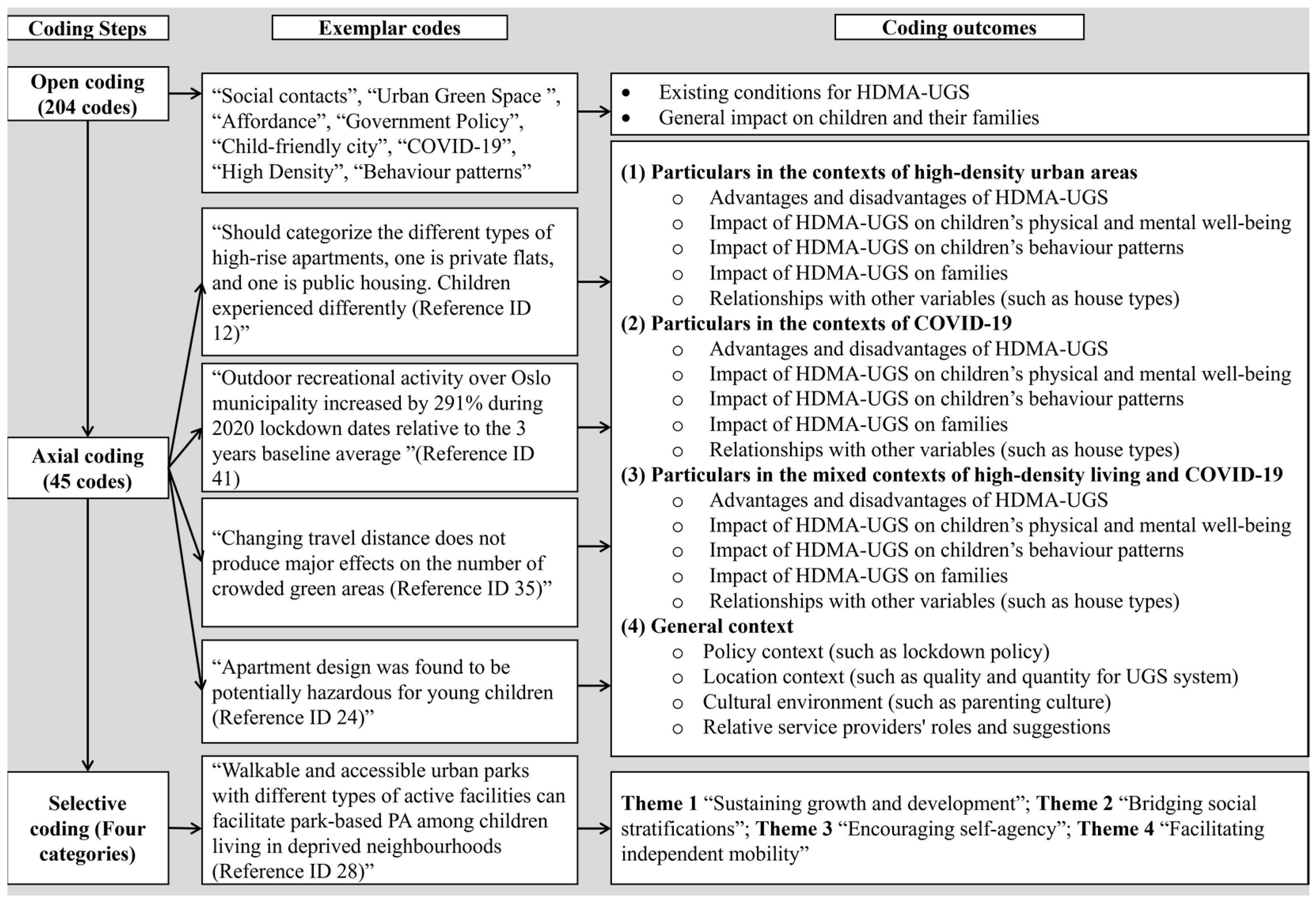

2.4. Thematic Analysis

2.5. Theoretical Framework

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

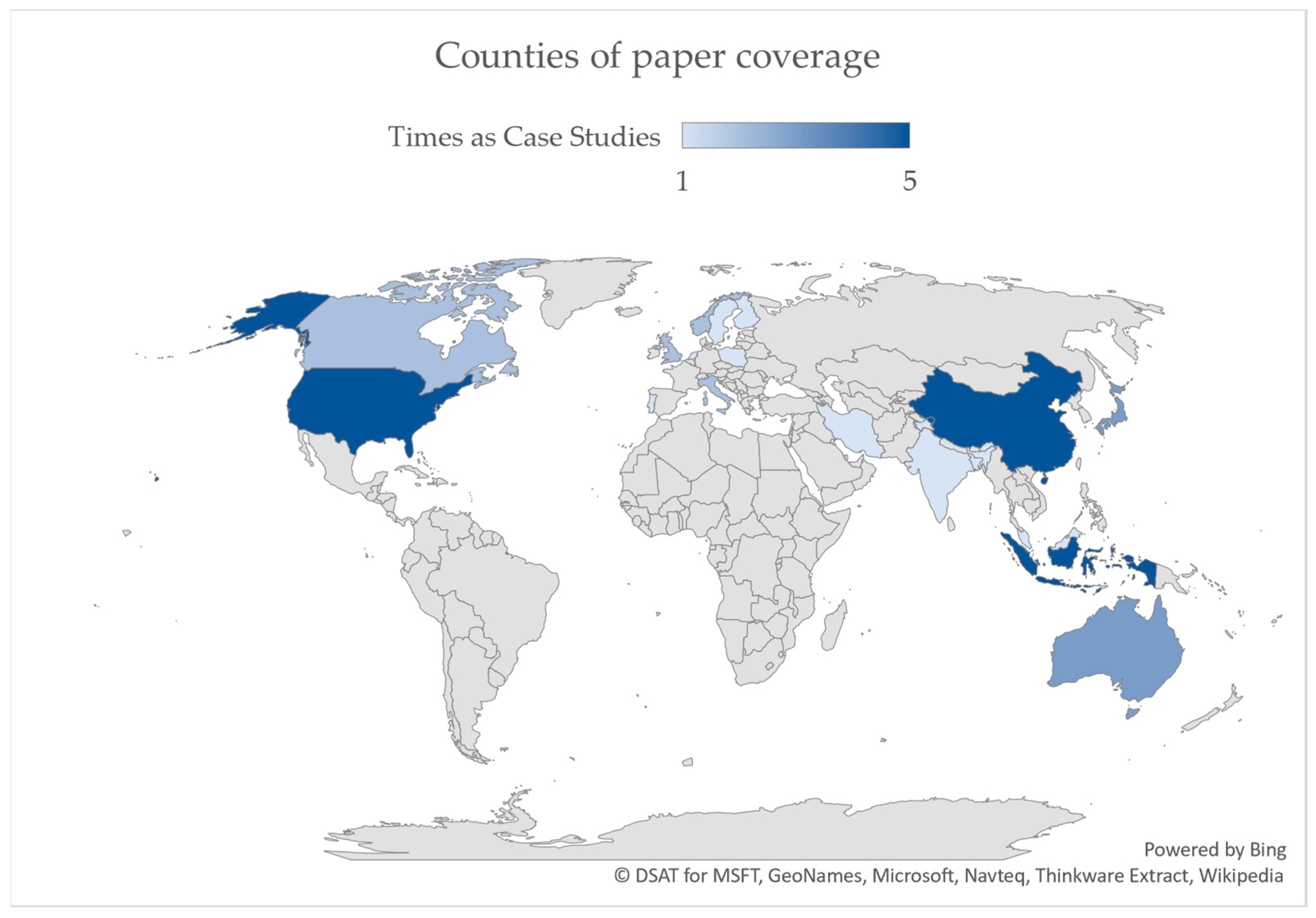

3.1.1. Timing and Location of the Studies

3.1.2. Scoping and Drivers for the Studies

3.1.3. Types of Green Spaces

3.2. Thematic Analysis—HDMA-UGS Roles

3.2.1. Sustaining Growth and Development

3.2.2. Bridging Social Stratifications

3.2.3. Encouraging Self-Agency

3.2.4. Facilitating Independent Mobility

3.3. Thematic Analysis—Policy and Service Provider Roles

3.3.1. Policy Environment

3.3.2. Service Provider Roles

4. Discussion

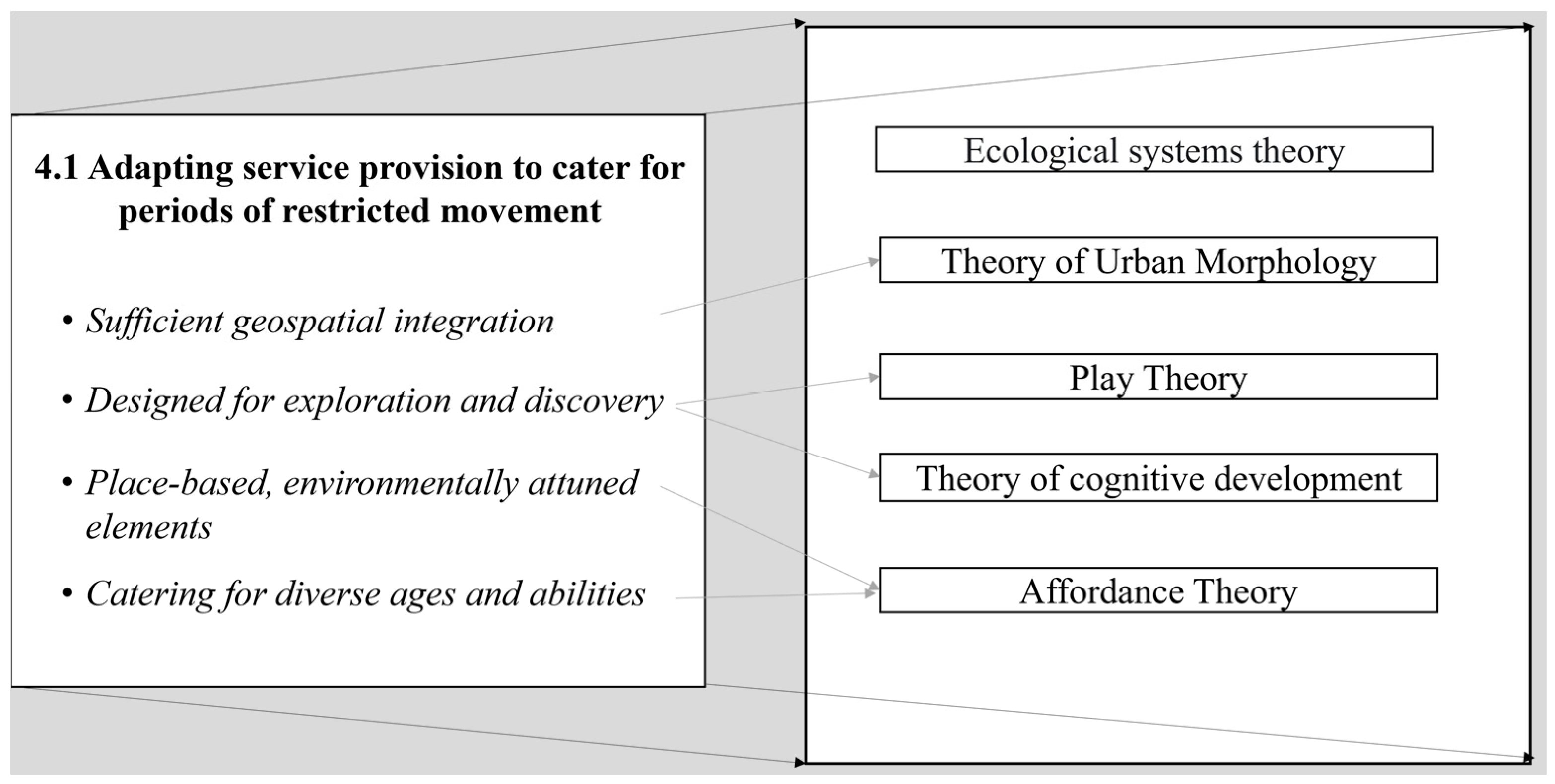

4.1. Adapting Service Provision to Cater for Periods of Restricted Movement

4.1.1. Sufficient Geospatial Integration

4.1.2. Designed for Exploration and Discovery

4.1.3. Place-Based, Environmentally Attuned Elements

4.1.4. Catering for Diverse Ages and Abilities

4.2. Applying the Learning from Pandemics to Day-to-Day Living

4.2.1. Improving Socio-Economic Factors

4.2.2. Mitigating Urban Heat in High-Density Metropolitan Areas

4.2.3. Promoting Biodiversity in Mega-Cities

4.3. Theoretical Contribution and Suggestions

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buck, C.; Eiben, G.; Lauria, F.; Konstabel, K.; Page, A.; Ahrens, W.; Pigeot, I. Urban Moveability and Physical Activity in Children: Longitudinal Results from the IDEFICS and I. Family Cohort. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Atlantic Books: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 25 September 2015).

- Tamaki, E.; Shibuya, M. Urban Risk and Wellbeing in Asian Mega Cities; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, H.; Coll-Seck, A.M.; Banerjee, A.; Peterson, S.; Dalglish, S.L.; Ameratunga, S.; Balabanova, D.; Bhan, M.K.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Borrazzo, J.; et al. A Future for the World’s Children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 395, 605–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlett, K.; Turner, E.C. Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown Restrictions on Parents’ Attitudes towards Green Space and Time Spent Outside by Children in Cambridgeshire and North London, United Kingdom. People Nat. 2021, 4, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C.; van Heezik, Y. Children, Nature and Cities; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Commission on Children and Disasters. 2010 Report to the President and Congress; AHRQ Publication No. 10-M037; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2010; p. 192.

- Christensen, P.; Hadfield-Hill, S.; Horton, J.; Kraftl, P. Children Living in Sustainable Built Environments; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, S.; Das Chatterjee, N.; Ghosh, S. An Integrated Simulation Approach to the Assessment of Urban Growth Pattern and Loss in Urban Green Space in Kolkata, India: A GIS-Based Analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famutimi, J.T.F.; Olugbamila, O.B.O. Implications of Living in Harmony with Nature for Urban Sustainability in Post Covid-19 Era. Urban Reg. Plan. Rev. 2022, 8, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, Q. Integrating Green Infrastructure, Ecosystem Services and Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Sustainability: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Sanesi, G. Nature-Based Solutions: Settling the Issue of Sustainable Urbanization. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keresztes-Sipos, A.; Reith, A.; Fekete, A.; Balogh, P. The Role of Municipalities and Landscape Architects in the Public Involvement Processes Related to Green Infrastructure Developments. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Agric. Environ. 2021, 13, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltmer, E.; Köslich-Strumann, S.; Walther, A.; Kasem, M.; Obst, K.; Kötter, T. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Stress, Mental Health and Coping Behavior in German University Students—A Longitudinal Study before and after the Onset of the Pandemic. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.K.; Sehgal, V.; Ogra, A. Creating a Child-Friendly Environment: An Interpretation of Children’s Drawings from Planned Neighborhood Parks of Lucknow City. Societies 2021, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, E.; Midouhas, E.; Joshi, H. The Role of Urban Neighbourhood Green Space in Children’s Emotional and Behavioural Resilience. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoneti, M. Children and Adolescents in the Physical Space: From a Playground for Children to a Child Friendly City or from Measures to Networks. Urbani Izziv 2000, 11, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaken, G.-J.; Danckaerts, M. Impact of Green Space Exposure on Children’s and Adolescents’ Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward Thompson, C.; Aspinall, P.; Bell, S. (Eds.) Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, T.; Sobek, C.; Ludwig, J.; Igel, U.; Grande, G.; Ott, V.; Kiess, W.; Körner, A.; Vogel, M. Associations of Green Spaces and Streets in the Living Environment with Outdoor Activity, Media Use, Overweight/Obesity and Emotional Wellbeing in Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabisch, N.; Haase, D.; Annerstedt van den Bosch, M. Proposing Access to Urban Green Spaces as an Indicator of Health Inequalities among Children. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25 (Suppl. S3), ckv176.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, S.S.; Thambiah, S.; Chakraborty, K. Children’s Agency in Accessing for Spaces of Play in an Urban High-Rise Community in Malaysia. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-C.L. A Study of Outdoor Interactional Spaces in High-Rise Housing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghri, Z.; Zermatten, J.; Lansdown, G.; Ruggiero, R. Monitoring State Compliance with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child an Analysis of Attributes; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the Built Environment. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.W.; Kenworthy, J.R. The Land Use—Transport Connection. Land Use Policy 1996, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, M.; Yusoff, M.M.; Shafie, A. Assessing the Role of Urban Green Spaces for Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review. GeoJournal 2021, 87, 4405–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, E.L.J.; Okyere, S.A.; Frimpong, L.K.; Diko, S.K.; Commodore, T.S.; Kita, M. Planning for Informal Urban Green Spaces in African Cities: Children’s Perception and Use in Peri-Urban Areas of Luanda, Angola. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, H. Interior Gardens; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusban, A.A.; Alhusban, S.A.; Alhusban, M.A. How the COVID 19 Pandemic Would Change the Future of Architectural Design. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A. The Greening of the City; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentz, K.; Speight, T. The Urban Garden; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, C.; Clare, C.M. People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, P.; Leverett, S. Children’s and Young People’s Spaces: Developing Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M.; Yao, B.; Cenci, J.; Liao, C.; Zhang, J. Visualisation of High-Density City Research Evolution, Trends, and Outlook in the 21st Century. Land 2023, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneralp, B.; Reba, M.; Hales, B.U.; Wentz, E.A.; Seto, K.C. Trends in Urban Land Expansion, Density, and Land Transitions from 1970 to 2010: A Global Synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaun, S.K.; King, C.; Wang, Z. Theorising with Urban China: Methodological and Tactical Experiments for a More Global Urban Studies. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2023, 204382062311566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Man, X.; Zhang, Y. From “Division” to “Integration”: Evolution and Reform of China’s Spatial Planning System. Buildings 2023, 13, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldera, H.T.S.; Desha, C.; Dawes, L. Exploring the Role of Lean Thinking in Sustainable Business Practice: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1546–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Longitudinal Field Research on Change: Theory and Practice. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Snyder-Duch, J.; Bracken, C.C. Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Baden, M.; Howell Major, C. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley, H.E.A.; Weiss, D.J. Interrater Reliability and Agreement. In Handbook of Applied Multivariate Statistics and Mathematical Modeling; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Collins, K.M.T.; Frels, R.K. Foreword: Using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory to Frame Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Research. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2013, 7, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’acci, L. The Mathematics of Urban Morphology; Cham Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, A.D. The Future of Play Theory: A Multidisciplinary Inquiry into Contributions of Brian Sutton-Smith; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, A.; Martin, A.; Cordovil, R.; Fjørtoft, I.; Iivonen, S.; Jidovtseff, B.; Lopes, F.; Reilly, J.J.; Thomson, H.; Wells, V.; et al. Nature-Based Early Childhood Education and Children’s Social, Emotional and Cognitive Development: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadavi, S.; Kaplan, R.; Hunter, M.C.R. Environmental Affordances: A Practical Approach for Design of Nearby Outdoor Settings in Urban Residential Areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.; Imrie, S.; Fink, E.; Gedikoglu, M.; Hughes, C. Understanding Changes to Children’s Connection to Nature during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Implications for Child Well-Being. People Nat. 2021, 4, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanza, K.; Durand, C.P.; Alcazar, M.; Ehlers, S.; Zhang, K.; Kohl, H.W. School Parks as a Community Health Resource: Use of Joint-Use Parks by Children before and during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Guan, Q.; Wang, R. Can Parkland Mitigate Mental Health Burden Imposed by the COVID-19? A National Study in China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 67, 127451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, C.; Neilson, A.L.; Menezes, I. COVID-19 and the Desire of Children to Return to Nature: Emotions in the Face of Environmental and Intergenerational Injustices. J. Environ. Educ. 2021, 52, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Iida, A.; Hino, K.; Murayama, A.; Hiroi, U.; Terada, T.; Koizumi, H.; Yokohari, M. Use of Urban Green Spaces in the Context of Lifestyle Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Tokyo. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneletti, D.; Cortinovis, C.; Zardo, L. Simulating Crowding of Urban Green Areas to Manage Access during Lockdowns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 219, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomikawa, S.; Niwa, Y.; Lim, H.; Kida, M. The Impact of the “COVID-19 Life” on the Tokyo Metropolitan Area Households with Primary School-Aged Children: A Study Based on Spatial Characteristics. J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M. Urban Nature in a Time of Crisis: Recreational Use of Green Space Increases during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Access and Use of Green Areas during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Green Infrastructure Management in the “New Normal”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Brussoni, M.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Ferguson, L.J.; Mitra, R.; O’Reilly, N.; Spence, J.C.; Vanderloo, L.M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Virus Outbreak on Movement and Play Behaviours of Canadian Children and Youth: A National Survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoari, N.; Ezzati, M.; Baumgar Aghatner, J.; Malacarne, D.; Fecht, D. Accessibility and Allocation of Public Parks and Gardens in England and Wales: A COVID-19 Social Distancing Perspective. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.-H.; Hipp, J.A.; Marquet, O.; Alberico, C.; Fry, D.; Mazak, E.; Lovasi, G.S.; Robinson, W.R.; Floyd, M.F. Neighborhood Characteristics Associated with Park Use and Park-Based Physical Activity among Children in Low-Income Diverse Neighborhoods in New York City. Prev. Med. 2020, 131, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitzman, C.; Mizrachi, D. Creating Child-Friendly High-Rise Environments: Beyond Wastelands and Glasshouses. Urban Policy Res. 2012, 30, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, A.M.; Broberg, A.K.; Kahila, M.H. Urban Environment and Children’s Active Lifestyle: SoftGIS Revealing Children’s Behavioral Patterns and Meaningful Places. Am. J. Health Promot. 2012, 26, e137–e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, M.-J.; de Vries, S.I.; van Oers, H.A.; Schuit, A.J. Outdoor Play among Children in Relation to Neighborhood Characteristics: A Cross-Sectional Neighborhood Observation Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Burgt, D.; Gustafson, K. “Doing Time” and “Creating Space”: A Case Study of Outdoor Play and Institutionalized Leisure in an Urban Family. Child. Youth Environ. 2013, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.J.; Warner, E.; Robson, B. High-Rise Parenting: Experiences of Families in Private, High-Rise Housing in Inner City Melbourne and Implications for Children’s Health. Cities Health 2018, 3, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Lai, P.C.; Kwan, M.-P. Park and Neighbourhood Environmental Characteristics Associated with Park-Based Physical Activity among Children in a High-Density City. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 68, 127479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohareb, N.; Felix, M.; Elsamahy, E. A Child-Friendly City: A Youth Creative Vision of Reclaiming Interstitial Spaces In El Mina (Tripoli, Lebanon). Creat. Stud. 2019, 12, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.R. Geographies of Outdoor Play in Dhaka: An Explorative Study on Children’s Location Preference, Usage Pattern, and Accessibility Range of Play Spaces. Child. Geogr. 2021, 20, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.J.; Warner, E. “Living Outside the House”: How Families Raising Young Children in New, Private High-Rise Developments Experience Their Local Environment. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2019, 13, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M. Outdoor Play Areas for Children in High-Density Housing in Montreal. Master’s Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ristianti, N.S.; Widjajanti, R. The Effectiveness of Inclusive Playground Usage for Children through Behavior-Setting Approach in Tembalang, Semarang City. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 592, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemmich, J.N.; Epstein, L.H.; Raja, S.; Yin, L.; Robinson, J.; Winiewicz, D. Association of Access to Parks and Recreational Facilities with the Physical Activity of Young Children. Prev. Med. 2006, 43, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, T.A.; Meriwether, R.A.; Baker, E.T.; Watkins, L.T.; Johnson, C.C.; Webber, L.S. Safe Play Spaces to Promote Physical Activity in Inner-City Children: Results from a Pilot Study of an Environmental Intervention. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1625–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuniastuti, E.; Hasibuan, H.S. Green Open Space, towards a Child-Friendly City (a Case Study in Lembah Gurame Park, Depok City, Jakarta Greater Area, Indonesia). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 328, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihantini, P.; Kurniawati, W. Mapping of Child Friendly Parks Availability for Supporting Child Friendly City in Semarang. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 313, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.M. A Child-Friendly Design for Sustainable Urban Environment: A Case Study of Malang City Parks. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 881, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbø, E.C.A.; Raanaas, R.K.; Nordh, H.; Aamodt, G. Neighborhood Green Spaces, Facilities and Population Density as Predictors of Activity Participation among 8-Year-Olds: A Cross-Sectional GIS Study Based on the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikorska, D.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Krauze, K.; Sikorski, P. The Role of Informal Green Spaces in Reducing Inequalities in Urban Green Space Availability to Children and Seniors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 108, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, L. Middle-Class Childhood and Parenting Culture in High-Rise Hong Kong: On Scheduled Lives, the School Trap and a New Urban Idyll. Child. Geogr. 2014, 13, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M. At Home with Nature. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C.; Annunziata, A. Smart City Governance and Children’s Agency: An Assessment of the Green Infrastructure Impact on Children’s Activities in Cagliari (Italy) with the Tool “Opportunities for Children in Urban Spaces (OCUS)”. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, S.P. How Does the Playground Role in Realizing Children-Friendly-City? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharghi, A.; Maulan, S.B.; Salleh, I.B.; Salim, A. The Relationship of Children Connectivity and Physical Activities with Satisfaction of Open Spaces in High Rise Apartments in Tehran. Int. J. Kinesiol. Sports Sci. 2014, 2, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, M.K.; Sehgal, V.; Ogra, A. A Critical Review of Standards to Examine the Parameters of Child-Friendly Environment (CFE) in Parks and Open Space of Planned Neighborhoods: A Case of Lucknow City, India. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holding, E.; Fairbrother, H.; Griffin, N.; Wistow, J.; Powell, K.; Summerbell, C. Exploring the Local Policy Context for Reducing Health Inequalities in Children and Young People: An in Depth Qualitative Case Study of One Local Authority in the North of England, UK. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.K.; Ghandour, R.M. Impact of Neighborhood Social Conditions and Household Socioeconomic Status on Behavioral Problems among US Children. Matern. Child Health J. 2012, 16 (Suppl. S1), 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grusky, D.B. Social Stratification; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpulainen, K.; Krokfors, L.; Lipponen, L.; Tissari, V.; Hilppö, J.; Rajala, A. Oppimisen Sillat: Kohti Osallistavia Oppimisympäristöjä; University of Helsinki Libraries: Helsinki, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koshy, V.; Smith, C.P.; Brown, J. Parenting “Gifted and Talented” Children in Urban Areas. Gift. Educ. Int. 2016, 33, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, S.; Howe, N.; Persram, R.J. Parents’ and Children’s Power Effectiveness during Polyadic Family Conflict: Process and Outcome. Soc. Dev. 2018, 28, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, M.R.; Christensen, P. Is Children’s Independent Mobility Really Independent? A Study of Children’s Mobility Combining Ethnography and GPS/Mobile Phone Technologies. Mobilities 2009, 4, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissotto, A.; Tonucci, F. Freedom of Movement and Environmental Knowledge in Elementary School Children. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, M.; Adams, J.; Whitelegg, J. One False Move: A Study of Children’s Independent Mobility; Policy Studies Institute: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, B. Children’s Independent Mobility: A Comparative Study in England and Germany (1971–2010); Policy Studies Institute: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lovasi, G.S.; Schwartz-Soicher, O.; Quinn, J.W.; Berger, D.K.; Neckerman, K.M.; Jaslow, R.; Lee, K.K.; Rundle, A. Neighborhood Safety and Green Space as Predictors of Obesity among Preschool Children from Low-Income Families in New York City. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Parves Rana, M. Social Benefits of Urban Green Space. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2012, 23, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Andreucci, M.B. Raising Healthy Children: Promoting the Multiple Benefits of Green Open Spaces through Biophilic Design. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robel, S. Green Space in the Community; Images Publishing Group: Mulgrave, VIC, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, K. Connecting to Food: Cultivating Children in the School Garden. Child. Geogr. 2016, 15, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullu, B. Geographies of Children’s Play in the Context of Neoliberal Restructuring in Istanbul. Child. Geogr. 2017, 16, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Lee, H.; Millar, C.A.; Spence, J.C. “Eyes on Where Children Play”: A Retrospective Study of Active Free Play. Child. Geogr. 2013, 13, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.N.; Müller, F.; Kanegae, M.M.; Morgade, M. Two Childhoods, Two Neighborhoods, and One City: Utopias and Dystopias in Brasilia. Child. Geogr. 2020, 19, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Abbott, R. Physical Activity and Rural Young People’s Sense of Place. Child. Geogr. 2009, 7, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacilli, M.G.; Giovannelli, I.; Prezza, M.; Augimeri, M.L. Children and the Public Realm: Antecedents and Consequences of Independent Mobility in a Group of 11–13-Year-Old Italian Children. Child. Geogr. 2013, 11, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Jones, D.; Sloan, D.; Rustin, M. Children’s Independent Spatial Mobility in the Urban Public Realm. Childhood 2000, 7, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, A.; Timperio, A.; Crawford, D. Playing It Safe: The Influence of Neighbourhood Safety on Children’s Physical Activity—A Review. Health Place 2008, 14, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wales, M.; Mårtensson, F.; Jansson, M. “You Can Be Outside a Lot”: Independent Mobility and Agency among Children in a Suburban Community in Sweden. Child. Geogr. 2020, 19, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomanović, S.; Petrović, M. Children’s and Parents’ Perspectives on Risks and Safety in Three Belgrade Neighbourhoods. Child. Geogr. 2010, 8, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, M. Playground Design; Braun Publishing: Salenstein, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Huang, W.Y.; Xing, R. Relationship between Parental Granting Mobility License and After-School Physical Activity in Children. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52 (Suppl. S7), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesooriya, N.; Brambilla, A.; Markauskaitė, L. A Biophilic Design Guide to Environmentally Sustainable Design Studios; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A. Informal Urban Greenspace: A Typology and Trilingual Systematic Review of Its Role for Urban Residents and Trends in the Literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A.; Lo, A.Y. Memories of Vacant Lots: How and Why Residents Used Informal Urban Green Space as Children and Teenagers in Brisbane, Australia, and Sapporo, Japan. Child. Geogr. 2015, 14, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincetl, S.; Gearin, E. The Reinvention of Public Green Space. Urban Geogr. 2005, 26, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Sundevall, E.; Wales, M. The Role of Green Spaces and Their Management in a Child-Friendly Urban Village. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.B. The Role of Social and Cultural Factors in Environmental Design and Affordance Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Storli, R.; Hagen, T.L. Affordances in Outdoor Environments and Children’s Physically Active Play in Pre-School. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieske, B.; Withagen, R.; Smith, J.; Zaal, F.T.J.M. Affordances in a Simple Playscape: Are Children Attracted to Challenging Affordances? J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, M. Çocuklar İçin Kamusal Mekânda Sosyal Adalet: Kadıköy—Sultanbeyli Örneğinde Kamusal Açık ve Yeşil Alanların İncelenmesi. MEGARON 2019, 14, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, J.L. Measuring Neighborhood Accessibility to Public Green Space: An Environmental Justice Study of Gronton, Ct. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Geography, Central Connecticut State University, New Britain, CT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X.; Mavoa, S.; Badland, H.M.; Giles-Corti, B. Do Low-Income Neighbourhoods Have the Least Green Space? A Cross-Sectional Study of Australia’s Most Populous Cities. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.-Y.; Kim, J.; Chong, W.K.O.; Ariaratnam, S.T. Urban Green Space Layouts and Urban Heat Island: Case Study on Apartment Complexes in South Korea. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2018, 144, 04018004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghavani, S.; Malakooti, H.; Bidokhti, A.A.A. Numerical Assessment of the Urban Green Space Scenarios on Urban Heat Island and Thermal Comfort Level in Tehran Metropolis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhao, S. Scale Dependence of Urban Green Space Cooling Efficiency: A Case Study in Beijing Metropolitan Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, S.; Antonio, J.; Murisic, M. Nature-Based Solutions for Improving Resilience in the Caribbean; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shochat, E.; Lerman, S.B.; Anderies, J.M.; Warren, P.S.; Faeth, S.H.; Nilon, C.H. Invasion, Competition, and Biodiversity Loss in Urban Ecosystems. BioScience 2010, 60, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, O.O.; Garmestani, A.S.; Albro, S.; Ban, N.C.; Berland, A.; Burkman, C.E.; Gardiner, M.M.; Gunderson, L.; Hopton, M.E.; Schoon, M.L.; et al. Adaptive Governance to Promote Ecosystem Services in Urban Green Spaces. Urban Ecosyst. 2015, 19, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossola, A.; Jari, N. Urban Biodiversity: From Research to Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Şenik, B.; Uzun, O. An Assessment on Size and Site Selection of Emergency Assembly Points and Temporary Shelter Areas in Düzce. Nat. Hazards 2020, 105, 1587–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, F.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Q. Biodiversity in Urban Green Space: A Bibliometric Review on the Current Research Field and Its Prospects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Words | Children | Green Spaces | High-Density |

|---|---|---|---|

| MeSH Terms (for MedLine search engine) | Child Tree Number(s): M01.060.406 MeSH Unique ID: D002648 | Green Spaces Tree Number(s): J03.925.680. MeSH Unique ID: D000068316 | High-density Tree Number(s): F01.145.875.281 MeSH Unique ID: D003441 |

| Additional Keywords (for other search engines) | Children, Kid | Parks (s), Playgrounds; Gardens; Greenery Grounds | Crowded; Populated; Metropolitan; High-density; Urban; Urbanisation; Urban sprawl; urban fortressing; segregation |

| Pandemic: SARS; Pandemic; COVID-19; Coronavirus; fever; HIVI; Bird flu; influenza; HIV; H5N1 virus; Bird flu; H1N1; Swine Flu; the plague; Anthrax; Cholera; Leptospirosis. | |||

| Mobility: Movement; Confined; Limited; Confinement; Restricted; Restriction | |||

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Date | All dates of publications were considered | |

| Language | Written in English or Chinese | Poor-quality English or Chinese |

| Type of publication | Peer-reviewed journal papers Conference proceedings and editorials, book and book chapters, reports | Literature reviews, letters, editorial and position papers If only the abstract is available Newspapers and trade papers |

| Research scope/themes | Discusses the association between children and urban green space in the contexts of high-density or high-rise living environments. | Urban green space is limited to in situ examples: balcony, indoor courtyard, patio, indoor playgrounds, etc. |

| Database Type | Research Result (without Timeframe) | 10 Years | 5 Years | 1 Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOAJ | 202 | 207 | 137 | 49 |

| ERIC | 6 | 1 | - | - |

| JSTOR | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PubMed | 478 | 267 | 149 | 33 |

| Science Direct | 407 | 82 | 52 | 15 |

| Scopus | 539 | 317 | 200 | 60 |

| Web of Science | 457 | 274 | 169 | 49 |

| Author/s | Pandemic/s of Focus | Type of Study | UGS Roles (‘E’—Evidenced; ‘R’—Recommended) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustaining Growth and Development | Bridging Social Stratifications | Encouraging Self-Agency | Facilitating Independent Mobility | ||||

| Friedman et al. (2022) | [55] | *Y | *Qual | E | R | R | R |

| Lanza et al. (2021) | [56] | *Y | *Quant | R | E | R | - |

| Yao et al. (2022) | [57] | *Y | *Quant | R | - | E | R |

| Rios et al. (2021) | [58] | *Y | *Qual | E | R | - | - |

| Yamazaki et al. (2021) | [59] | *Y | *Mixed | - | R | E | - |

| Geneletti et al. (2022) | [60] | *Y | *Quant | - | E | - | - |

| Tomikawa et al. (2021) | [61] | *Y | *Qual | - | E | - | - |

| Venter et al. (2020) | [62] | *Y | *Quant | R | - | - | - |

| Yuta and Ryo (2020) | [63] | *Y | *Quant | - | E | - | - |

| Moore et al. (2020) | [64] | *Y | *Quant | - | - | E | - |

| Shoari et al. (2020) | [65] | *Y | *Quant | E | - | - | - |

| Huang et al. (2006) | [24] | - | *Qual | R | E | R | R |

| Huang et al. (2020) | [66] | - | *Quant | R | E | R | R |

| Whitzman and Mizrachi (2012) | [67] | - | *Qual | R | E | R | E |

| Kyttä et al. (2012) | [68] | - | *Mixed | R | R | E | E |

| Agarwal et al. (2021) | [16] | - | *Qual | R | R | E | - |

| Aarts et al. (2012) | [69] | - | *Mixed | R | R | E | - |

| van der Burgt et al. (2013) | [70] | - | *Qual | R | R | E | - |

| Andrews et al. (2019) | [71] | - | *Qual | R | - | E | E |

| Zhang et al. (2022) | [72] | - | *Mixed | R | - | R | E |

| Mohareb et al. (2019) | [73] | - | *Mixed | E, R | - | R | - |

| Bhuyan (2022) | [74] | - | *Mixed | R | E | - | - |

| Agha (2019) | [23] | - | *Qual | R | - | E | - |

| Andrews and Warner (2020) | [75] | - | *Qual | R | - | E | - |

| Aggarwal (2001) | [76] | - | *Qual | R | - | - | E |

| Ristianti and Widjajanti (2020) | [77] | - | *Quant | - | - | R | E |

| Roemmich et al. (2006) | [78] | - | *Quant | - | E | - | R |

| Farley et al. (2007) | [79] | - | *Mixed | - | R | - | E |

| Yuniastuti et al. (2019) | [80] | - | *Mixed | R | - | - | - |

| Simoneti (2000) | [18] | - | *Qual | E | - | - | - |

| Prihantini and Kurniawati (2019) | [81] | - | *Qual | E | - | - | - |

| Nugroho (2021) | [82] | - | *Quant | R | - | - | - |

| Nordbø et al. (2019) | [83] | - | *Quant | E | - | - | - |

| Sikorska et al. (2020) | [84] | - | *Quant | - | E | - | - |

| Marquet et al. (2019) | [73] | - | *Quant | - | E | - | - |

| Karsten (2015) | [85] | - | *Qual | - | - | E | - |

| Wells (2000) | [86] | - | *Quant | - | - | E | - |

| Garau et al. (2019) | [87] | - | *Mixed | - | - | E | - |

| Dewi (2012) | [88] | - | *Quant | - | - | E | - |

| Sharghi et al. (2014) | [89] | - | *Qual | - | - | - | E |

| Key Policies Examples | Type of Policy | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19-related policy; key policy measures to reduce the transmission of SAR-CoV-2 and protect public health. | COVID-19 Pandemic Policy | Shoari et al. (2020) [65]; Yao et al. (2022) [57]; Venter et al. (2020) [62] |

| The government incentive policy issued in 1984; policy levers; government policy on housing design; no explicit child-friendly policy on high-rise, private housing. Apartment guidelines (the new Victorian Apartment Guidelines); Australian policy on the design of high-rise dwellings; integrative planning practices and solutions. | Housing Policy | Whitzman and Mizrachi (2012) [67]; Nordbø et al. (2019) [83]; Aggarwal (2021) [76]; Andrew and Warner (2020) [75]; Andrews et al. (2018) [71] |

| Child-friendly-city policy; policies regarding the use of specific green areas, including parks, agricultural lands, and gardens; policy related to local spatial planning and traffic and transportation; common international standards and policy objectives for local green space planning (16 policy scenarios); spatial planning policy. | Design Policy | Dewi (2012) [88]; Yao et al., (2022) [57]; Aarts et al. (2012) [69]; Geneletti et al. (2022) [60]; Sikorska et al. (2020) [84] |

| Policy in relation to children’s health in Australia. | Health Policy | Andrews et al. (2018) [71] |

| Current planetary economic policy. | Economic Policy | Rios et al. (2021) [58] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Desha, C.; Caldera, S.; Beer, T. Roles of Urban Green Spaces for Children in High-Density Metropolitan Areas during Pandemics: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030988

Wang Y, Desha C, Caldera S, Beer T. Roles of Urban Green Spaces for Children in High-Density Metropolitan Areas during Pandemics: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030988

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yunjin, Cheryl Desha, Savindi Caldera, and Tanja Beer. 2024. "Roles of Urban Green Spaces for Children in High-Density Metropolitan Areas during Pandemics: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030988

APA StyleWang, Y., Desha, C., Caldera, S., & Beer, T. (2024). Roles of Urban Green Spaces for Children in High-Density Metropolitan Areas during Pandemics: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 16(3), 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030988