Entrepreneurship among Social Workers: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurial Intention and SDGs

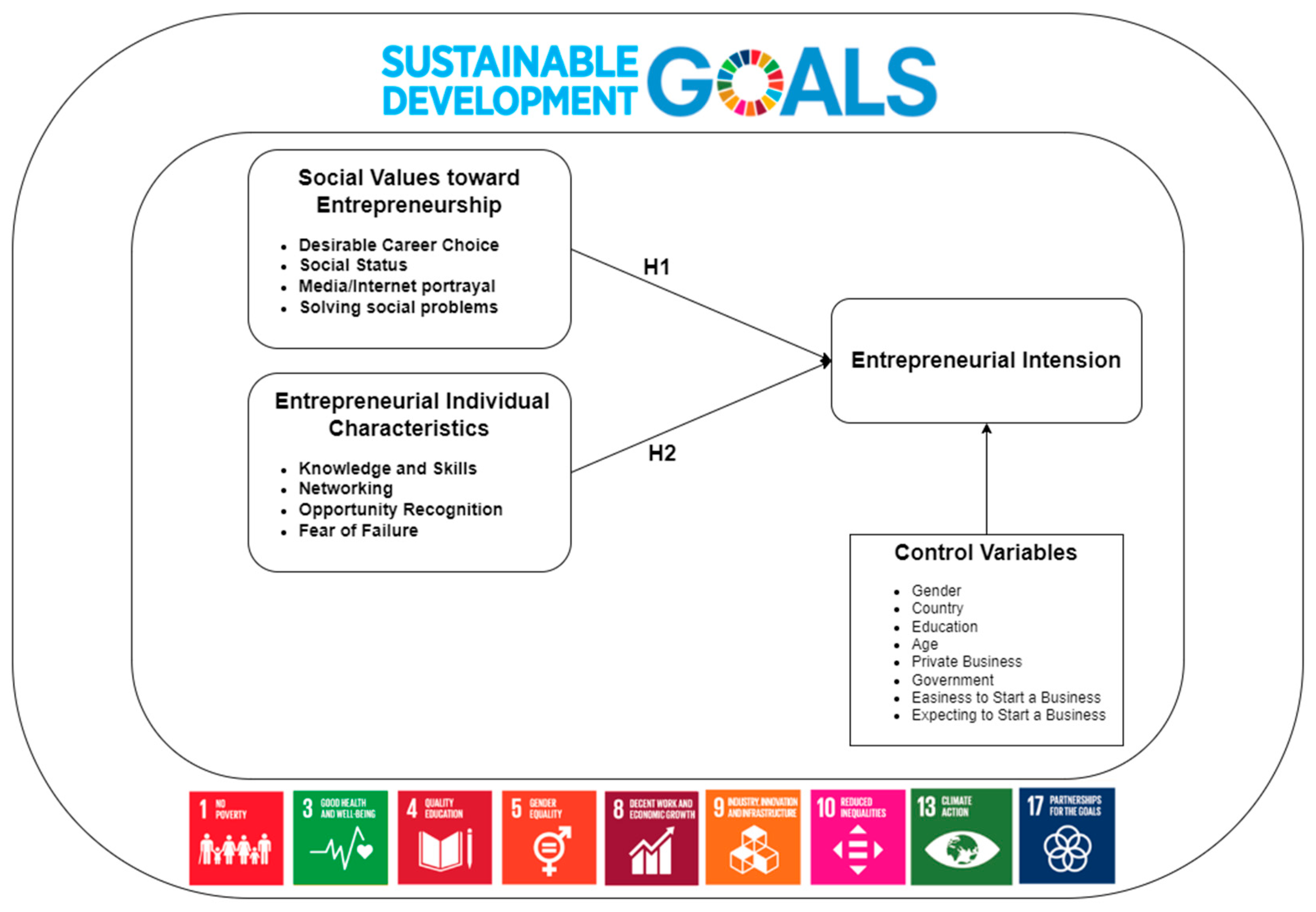

2.2. Social Values towards Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Intention

2.3. Entrepreneurial Individual Characteristics and Entrepreneurial Intention

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. SDGs Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | EDU | NET | OPT | KNOW | FOF | CAREER | STATUS | MEDIA | EASY | SOCP | BSTART | FUTSUP | PRIV | GOV | GEN | AGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NET | 0.097 ** | |||||||||||||||

| OPT | 0.147 ** | 0.203 ** | ||||||||||||||

| KNOW | 0.045 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.168 ** | |||||||||||||

| FOF | 0.03 | 0.011 | −0.059 ** | −0.148 ** | ||||||||||||

| CAREER | −0.052 ** | 0.031 * | 0.128 ** | 0.027 | −0.007 | |||||||||||

| STATUS | 0.057 ** | 0.002 | 0.118 ** | −0.015 | 0.081 ** | 0.142 ** | ||||||||||

| MEDIA | 0.012 | 0.022 | 0.102 ** | 0.03 | 0.011 | 0.141 ** | 0.152 ** | |||||||||

| EASY | 0.040 * | 0.045 * | 0.243 ** | 0.089 ** | −0.094 ** | 0.122 ** | 0.078 ** | 0.128 ** | ||||||||

| SOCP | −0.013 | 0.019 | 0.076 ** | 0.067 ** | −0.036 | 0.081 ** | 0.105 ** | 0.154 ** | 0.135 ** | |||||||

| BSTART | 0.021 | 0.145 ** | 0.099 ** | 0.189 ** | −0.068 ** | 0.073 ** | 0.018 | 0.040 ** | 0.017 | 0.070 ** | ||||||

| FUTSUP | 0.031 * | 0.157 ** | 0.142 ** | 0.226 ** | −0.076 ** | 0.083 ** | 0.008 | 0.054 ** | 0.019 | 0.049 * | 0.407 ** | |||||

| PRIV | −0.106 ** | 0.032 * | −0.007 | 0.124 ** | −0.071 ** | 0.018 | 0.005 | −0.029 | −0.01 | 0.046 * | 0.090 ** | 0.078 ** | ||||

| GOV | 0.056 ** | −0.021 | −0.014 | −0.039 * | 0.024 | −0.004 | −0.002 | −0.043 ** | −0.052 ** | −0.048 * | −0.028 | −0.009 | −0.429 ** | |||

| GEN | −0.037 * | 0.050 ** | 0.041 * | 0.136 ** | −0.062 ** | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.084 ** | 0.089 ** | 0.144 ** | −0.028 | ||

| AGE | −0.005 | −0.104 ** | −0.041 * | 0.026 | −0.052 ** | −0.062 ** | −0.058 ** | 0.012 | −0.006 | −0.036 | −0.088 ** | −0.141 ** | −0.062 ** | 0.066 ** | −0.018 | |

| SOC_V | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.204 ** | 0.075 ** | 0.034 | 0.558 ** | 0.622 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.199 ** | 0.545 ** | 0.085 ** | 0.077 ** | 0.008 | −0.079 ** | 0.026 | −0.049 * |

References

- United Nations. Challenges and Opportunities in the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nhapi, T.; Pinto, C. Embedding SDGs in Social Work Education: Insights from Zimbabwe and Portugal BSW and MSW Programs. Soc. Work Educ. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasooria, D. Sustainable Development Goals and Social Work: Opportunities and Challenges for Social Work Practice in Malaysia. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 2016, 1, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civinskas, R.; Dvorak, J.; Šumskas, G. Beyond the Front-Line: The Coping Strategies and Discretion of Lithuanian Street-Level Bureaucracy during COVID-19. Corvinus J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 12, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimba, Z.F. Cultural Complexity Thinking by Social Workers in Their Address of Sustainable Development Goals in a Culturally Diverse South Africa. J. Progress. Hum. Serv. 2020, 31, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliński, M.; Mioduszewski, J. Determinants of Development of Social Enterprises According to the Theory of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, G.; Tschopp, C.; Grote, G.; Hirschi, A. Grass Roots of Occupational Change: Understanding Mobility in Vocational Careers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 122, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, S.P. Shifting Patterns: How Satisfaction Alters Career Change Intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, L.; Oh, I.S.; Vankatwyk, P.; Tesluk, P.E. Developing Executive Leaders: The Relative Contribution of Cognitive Ability, Personality, and the Accumulation of Work Experience in Predicting Strategic Thinking Competency. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 829–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Transaction Publisher: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.C. The Economics of Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; pp. 39–67. ISBN 1139451863. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, M.; Wyrwich, M. The Effect of Entrepreneurship on Economic Development-an Empirical Analysis Using Regional Entrepreneurship Culture. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 17, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim Neto, R.d.C.; Picanço Rodrigues, V.; Panzer, S. Exploring the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Behavior and Teachers’ Job Satisfaction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetakis, L.A. The Role of Creativity and Proactivity on Perceived Entrepreneurial Desirability. Think. Ski. Creat. 2008, 3, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Gil-Soto, E.; Ruiz-Rosa, I.; Sene, P.M. Entrepreneurial Intentions in Diverse Development Contexts: A Cross-Cultural Comparison between Senegal and Spain. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing Models of Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.; Bosma, N.; Autio, E.; Hunt, S.; De Bono, N.; Servais, I.; Lopez-Garcia, P.; Chin, N. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: Data Collection Design and Implementation 1998–2003. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Brazeal, D.V. Enterprise Potential and Potential Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A. The Displaced, Uncomfortable Entrepreneur; University Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneur: Champaign, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship. Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship; En Kent, C.A., Sexton, D.L., Vespert, K.H., Eds.; Prentice-Hall: Kent, OH, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, G.B.; Schin, G.C.; Sava, V.; Panait, A.A. Career Path Changer: The Case of Public and Private Sector Entrepreneurial Employee Intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burksiene, V.; Dvorak, J.; Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, G. Sustainability and Sustainability Marketing in Competing for the Title of European Capital of Culture. Organizacija 2018, 51, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhahri, S.; Slimani, S.; Omri, A. Behavioral Entrepreneurship for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 165, 120561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véliz Palomino, J.C.; Pimentel Bernal, P.M.; Arana Barbier, P.J. Identificación de Factores Sociales y Económicos Que Influyen En El Emprendimiento Mediante Un Modelo de Ecuaciones Estructurales. Contaduría Adm. 2023, 68, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Bulsara, H.P.; Trivedi, M.; Bagdi, H. An Analysis of Sustainability-Driven Entrepreneurial Intentions among University Students: The Role of University Support and SDG Knowledge. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, S.; Kiran, R. Examining the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Perceived Behaviour, Intentions, and Competencies as Catalysts for Sustainable Growth: An Indian Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walidayni, C.T.; Dellyana, D.; Chaldun, E.R. Towards SDGs 4 and 8: How Value Co-Creation Affecting Entrepreneurship Education’s Quality and Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, A.; Suresh, M. Exploring the Contribution of Sustainable Entrepreneurship toward Sustainable Development Goals: A Bibliometric Analysis. Green Technol. Sustain. 2023, 1, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Gomes, S.; Pacheco, R. Unveiling the Antecedents of Sustainability-Oriented Entrepreneurial Intentions in Angolan Universities: Theory Planned Behavior Extension Proposal. Ind. High. Educ. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, I.; Ahmad, A.; Saleem, I.; Yasin, N. Role of Entrepreneurship Education, Passion and Motivation in Augmenting Omani Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention: A Stimulus-Organism-Response Approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Jaramillo-Arévalo, M.; De-La-cruz-diaz, M.; Anderson-Seminario, M.d.l.M. Influence of Social, Environmental and Economic Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) over Continuation of Entrepreneurship and Competitiveness. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisca Castilla-Polo, A.L.-G.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, M.C. Best Practice Learning in Cooperative Entrepreneurship to Engage Business Students in the SDGs. Stud. High. Educ. 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nițu-Antonie, R.D.; Feder, E.-S.; Nițu-Antonie, V.; György, R.-K. Predicting Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions among Romanian Students: A Mediated and Moderated Application of the Entrepreneurial Event Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L. Versus Self-Employment: Reasons for Career Choice. Entrepenruersh. Theory Pract. 1996, 20, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.; Stutzer, A. Latent Entrepreneurship across Nations. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, A.; Thurik, R. Entrepreneurship and Its Determinants in a Cross-Country Setting. J. Evol. Econ. 2007, 17, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.C.; Van Praag, M. Group Status and Entrepreneurship. J. Econ. Manag. Strateg. 2010, 19, 919–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, C.D.M.; Miragaia, D.A.M.; Veiga, P.M. Entrepreneurial Intention of Sports Students in the Higher Education Context—Can Gender Make a Difference? J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2023, 32, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Hartog, C.; Hoogendoorn, B. Beyond the Moral Portrayal of Social Entrepreneurs: An Empirical Approach to Who They are and what Drives Them. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Alvarez, C. Institutional Dimensions and Entrepreneurial Activity: An International Study. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leković, B.; Uzelac, O.; Fazekaš, T.; Horvat, A.M.; Vrgović, P. Determinants of Social Entrepreneurs in Southeast Europe: Gem Data Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, E.; Noguera, M.; Urbano, D. The Effect of Cultural Factors on Social Entrepreneurship: The Impact of the Economic Downturn in Spain. In Entrepreneurship, Regional Development and Culture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 75–87. ISBN 9783319151106. [Google Scholar]

- Busenitz, L.W.; Barney, J.B. Differences between Entrepreneurs and Managers in Large Organizations: Biases and Heuristics in Strategic Decision-Making. J. Bus. Ventur. 1997, 12, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.C.; Woo, C.Y.; Dunkelberg, W.C. Entrepreneurs’ Perceived Chances for Success. J. Bus. Ventur. 1988, 3, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koellinger, P.; Minniti, M.; Schade, C. “I Think I Can, I Think I Can”: Overconfidence and Entrepreneurial Behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 2007, 28, 502–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C.F.; Lovallo, D. Overconfidence and Excess Entry: An Experimental Approach. In Choices, Values, and Frames; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L.W.; Gomez, C.; Spencer, J.W. Country Institutional Profiles: Unlocking Entrepreneurial Phenomena. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, I.M. Competition and Entrepreneurship; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S.A. Prior Knowledge and the Discovery of Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. Continued Entrepreneurship: Ability, Need, and Opportunity as Determinants of Small Firm Growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 1991, 6, 405–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Fogel, D.S. Environments for Entrepreneurship Development: Key Dimensions and Research Implications. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenius, P.; Minniti, M. Perceptual Variables and Nascent Entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The Role of Social and Human Capital among Nascent Entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, M. Entrepreneurial Alertness and Asymmetric Information in a Spin-Glass Model. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H. Organizations Evolving; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 0803989199. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir, O.; Karadeniz, E. Investigating the Factors Affecting Total Entrepreneurial Activities in Turkey. METU Stud. Dev. 2011, 38, 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V.; Ferreira, J.J.; Fernandes, C. Entrepreneurial and Network Knowledge in Emerging Economies: A Study of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Rev. Int. Bus. Strateg. 2016, 26, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkina, E. The Importance of Networking to Entrepreneurship: Montreal’s Artificial Intelligence Cluster and Its Born-Global Firm Element AI. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2018, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F. Contextualizing Entrepreneurship—Conceptual Challenges and Ways Forward. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Fernandes, C.I.; Veiga, P.M.; Caputo, A. The Interactions of Entrepreneurial Attitudes, Abilities and Aspirations in the (Twin) Environmental and Digital Transitions? A Dynamic Panel Data Approach. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. Descartes’ Error: Passion, Reason, and the Human Brain; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.A. The Psychology of Fear and Stress; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, F.; Van Apeldoorn, D.; Stuiver, M.; Kok, K. Niches and Networks: Explaining Network Evolution through Niche Formation Processes. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Carr, J.C. The Relationship between Entrepreneur Psychological Capital and Well-Being. Front. Entrep. Res. 2008, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, E.; Bosma, N.; van Witteloostuijn, A.; de Jong, J.P.J.; Bogaert, S.; Edwards, N.; Jaspers, F. Ambitious Entrepreneurship: A Review of the Academic Literature and New Directions for Public Policy; AWT: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 9789077005569. [Google Scholar]

- Cardon, M.S.; Wincent, J.; Singh, J.; Drnovsek, M. The Nature and Experience of Entrepreneurial Passion. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciotti, G.; Hayton, J.C. Fear of Failure and Entrepreneurship: A Review and Direction for Future Research. Enterp. Res. Centre Res. Pap. 2014, 24, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, K.H.; Chang, H.C.; Peng, C.Y. Refining the Linkage between Perceived Capability and Entrepreneurial Intention: Roles of Perceived Opportunity, Fear of Failure, and Gender. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, J.C.; Cholakova, M. The Role of Affect in the Creation and Intentional Pursuit of Entrepreneurial Ideas. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, P.M.; Miguel, V.; Marques, J.A. Entrepreneurial Intention of Communication Students: The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurship Education. Int. J. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataram, S. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. Acad. M 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurial Action and the Role of Uncertainty in the Theory of the Entrepreneur. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 31, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, S.; Metcalf, L.E.; York, J.L. Distinguishing Entrepreneurial Approaches to Opportunity Perception. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Locke, E.A.; Collins, C.J. Entrepreneurial Motivation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2003, 13, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, M.J.; Jones, P.; Pickernell, D. Country-Based Comparison Analysis Using FsQCA Investigating Entrepreneurial Attitudes and Activity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmann, C.; Rauch, A.; Zacher, H. A Lifespan Perspective on Entrepreneurship: Perceived Opportunities and Skills Explain the Negative Association between Age and Entrepreneurial Activity. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, E.; Fernandes, C.I.; Ferreira, J.J. The Role of Political and Economic Institutions in Informal Entrepreneurship. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 15, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardichvili, A.; Cardozo, R.; Ray, S. A Theory of Entrepreneurial Opportunity Identification and Development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardi, M.A.; Costa, J. Appraising the Role of Age among Senior Entrepreneurial Intentions. European Analysis Based on HDI. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 14, 953–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, M.; Costa, J.; Moreira, A.C. The Effect of University Missions on Entrepreneurial Initiative across Multiple Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Evidence from Europe. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voda, A.I.; Butnaru, G.I.; Butnaru, R.C. Enablers of Entrepreneurial Activity across the European Union-an Analysis Using GEM Individual Data. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM. GEM 2015/2016 Global Report. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2016. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=49480 (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Dependent Variable | Description | Source | Type |

| Intention to start a Business (BSTART) | Individual’s intention to start a business | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Independent Variables | Description | Source | Type |

| Desirable Career Choice (CAREER) | Starting a new business as a good career choice | GEM2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Social Status (STATUS) | Starting a new business has a high level of status and respect | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Media/Internet (MEDIA) | Stories of successful new businesses in public media/internet | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Solving social problems (SOCP) | Businesses that primarly aim to solve social problems | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Knowledge and Skills (KNOW) | Individual’s knowledge, skills, and experience | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Networking (NET) | Individual’s knowledge of entrepeneurs | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Opportunity Recognition (OPT) | Individual’s perception of a business opportunity | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Fear of Failure (FOF) | Individual’s Fear of Failure | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Control Variables | Description | Source | Type |

| Gender (GEN) | Individual’s Gender | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Country (COUNTRY) | Country | GEM 2018 (APS) | Dummy |

| Education (EDUC) | Individual’s Education | GEM 2018 (APS) | Multinomial |

| Age (AGE) | Individual’s Age | GEM 2018 (APS) | Continuos |

| Private Business (PRIV) | Employed in a private business | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Government (GOV) | Employed by the government | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Easiness to Start a Business (EASY) | Individual’s perception of the ease of starting a business | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Expecting to Start a Business (FUTSUP) | Individual’s expectations regarding starting a business | GEM 2018 (APS) | Binary |

| Variable | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDU | 4507 | 0 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.5 |

| NET | 4506 | 0 | 1 | 0.37 | 0.482 |

| OPT | 3702 | 0 | 1 | 0.51 | 0.5 |

| KNOW | 4320 | 0 | 1 | 0.44 | 0.497 |

| FOF | 4317 | 0 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.498 |

| CAREER | 4226 | 0 | 1 | 0.56 | 0.497 |

| STATUS | 4298 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.458 |

| MEDIA | 4273 | 0 | 1 | 0.59 | 0.492 |

| EASY | 2630 | 0 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.492 |

| SOCP | 2693 | 0 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| BSTART | 4521 | 0 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.288 |

| FUTSUP | 4339 | 0 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.389 |

| PRIV | 4519 | 0 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.478 |

| GOV | 4515 | 0 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.472 |

| GEN | 4545 | 0 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.497 |

| AGE | 4349 | 18 | 83 | 42.29 | 12.92 |

| SOCV | 2356 | −1.95 | 1.57 | 0 | 1 |

| All Sample | Public | Private | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |

| NET | 0.818 ** (0.185) | 0.777 ** (0.183) | 0.799 ** (0.183) | 0.764 ** (0.181) | 0.799 ** (0.184) | 0.758 ** (0.182) | |||

| OPT | −0.019 (0.195) | 0.006 (0.194) | −0.059 (0.194) | 0.033 (0.193) | 0.022 (0.195) | 0.003 (0.194) | |||

| KNOW | 0.814 ** (0.207) | 0.798 ** (0.205) | 0.825 ** (0.205) | 0.807 ** (0.204) | 0.830 ** (0.207) | 0.810 ** (0.205) | |||

| FOF | −0.151 (0.186) | −0.169 (0.185) | −0.131 (0.185) | 0.149 (0.184) | 0.153 (0.186) | 0.173 (0.184) | |||

| CAREER | 0.404 * (0.202) | 0.420 * (0.201) | 0.422 * (0.202) | ||||||

| STATUS | −0.098 (0.195) | −0.092 (0.194) | 0.121 (0.194) | ||||||

| MEDIA | −0.227 (0.195) | −0.231 (0.193) | 0.247 (0.193) | ||||||

| SOCP | 0.278 (0.197) | 0.272 (0.196) | 0.270 (0.196) | ||||||

| SOCV | 0.080 (0.099) | 0.084 (0.098) | 0.069 (0.098) | ||||||

| FUTSUP | 2.274 ** (0.167) | 1.923 ** (0.195) | 1.930 ** (0.194) | 2.276 ** (0.167) | 1.923 ** (0.194) | 1.927 ** (0.193) | 2.285 ** (0.167) | 1.930 ** (0.194) | 1.939 ** (01.94) |

| PRIV | 0.460 * (0.196) | 0.505 * (0.235) | 0.531 * (0.235) | 0.414 * (0.164) | 0.428 * (0.190) | 0.441 * (0.190) | |||

| GOV | 0.091 (0.203) | 0.144 (0.241) | 0.167 (0.239) | −0.177 (0.170) | −0.168 (0.195) | 0.158 (0.195) | |||

| GEN | 0.233 (0.153) | 0.112 (0.179) | 0.096 (0.178) | 0.265 (0.152) | 0.151 (0.176) | 0.140 (0.175) | 0.243 (0.153) | 0.126 (0.178) | 0.111 (0.177) |

| AGE | −0.005 (0.006) | −0.004 (0.007) | −0.005 (0.007) | −0.004 (0.006) | −0.003 (0.007) | 0.004 (0.007) | 0.005 (0.006) | 0.004 (0.07) | 0.005 (0.007) |

| EASY | 0.031 (0.165) | − 0.074 (0.198) | −0.083 (0.196) | 0.005 (0.164) | −0.103 (197) | 0.115 (0.195) | 0.035 (0.165) | 0.062 (0.197) | 0.071 (0.195) |

| EDU | 0.147 (0.161) | 0.026 (0.188) | 0.022 (0.188) | 0.119 (0.159) | −0.005 (0.186) | −0.016 (0.185) | 0.158 (0.160) | 0.035 (0.188) | 0.032 (0.187) |

| Pseudo R2 | 34.7% | 38.6% | 38.1% | 34.4% | 38.1% | 37.5% | 34.9% | 38.7% | 38.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, J.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Veiga, P.M. Entrepreneurship among Social Workers: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030996

Pereira J, Rodrigues RG, Veiga PM. Entrepreneurship among Social Workers: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030996

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, João, Ricardo Gouveia Rodrigues, and Pedro Mota Veiga. 2024. "Entrepreneurship among Social Workers: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030996

APA StylePereira, J., Rodrigues, R. G., & Veiga, P. M. (2024). Entrepreneurship among Social Workers: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 16(3), 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030996