Abstract

While there is growing interest in leader–follower relationships in the leadership literature, little is known about how a leader’s framing effect triggers employees’ proactive behaviors. This research aims to extend previous knowledge about the effects of leaders’ goal framing and uncover their potential impacts on followership behaviors. Drawing on social information processing theory, this study proposes that both types of goal framing (gaining and losing) indirectly influence employees’ followership behaviors by mobilizing their sense of work meaning, especially when they have a power dependence on their leaders, using the method of questionnaire measurement, CFA analysis, hierarchical regression analysis, and the bootstrap tested hypotheses. The results show that gain framing indirectly contributes to employees’ followership behaviors by enhancing work meaning. Furthermore, this positive indirect relationship is stronger for employees with high power dependence. Yet another finding reveals that loss framing negatively impacts followership behavior by reducing employees’ sense of work meaning, which is unaffected by power dependence. From the perspective of the framing effect, this study verifies the influence of goal framing on employees’ behaviors and illustrates the effect of work meaning as a mechanism of goal framing on followership behavior.

1. Introduction

Leaders, as crucial information sources within the organization, can guide employees’ attention to crucial information, thereby influencing their cognitive patterns and altering their overall perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward organizational goals and their daily work []. This phenomenon known as the “framing effect” illustrates how changes in description can reverse individual behavioral preferences, emphasizing the influence of information presentation on decision-making processes []. In the framing effect, speakers use negative or positive terms to construct information, thereby guiding listeners to make different behaviors. For example, a leader’s positive or negative depiction of current work can impact whether employees revolve their tasks around the leader, support, cooperate, and assist the leader’s work. In practice, some leaders use positive language or gain framing, emphasizing the prospects of success and favorable outcomes, motivating employees to act to achieve organizational goals and exhibit positive followership behaviors []. Alternatively, certain leaders believe that negative language or loss framing can stimulate employees by portraying potential losses and failures as threats to employee interests and intensifying employees’ feelings of insecurity, panic, and stress, aiming to force employees to transform stress into motivation and make positive efforts to achieve goals. However, when guiding employees towards active behaviors, does a leader’s use of positive or negative framing have the same persuasive effect? How can a leader best construct and communicate information to motivate their followers effectively?

Current research on the framing effect suggests that goal framing is a commonly used non-value intervention method in the fields of communication and behavioral persuasion. Goal framing is a type of framing effect, also known as gain–loss framing, that presents information in a way that influences decision-making processes and encourages goal-oriented behavior [,]. Goal framing is widely applied in real-life decision-making scenarios, including health, economic, and political decisions. It has also received significant attention and progress in organizational psychology research. Research has established connections between a leader’s gain–loss framing and outcomes such as employee innovative behavior, knowledge hiding, unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB), work performance, and work attitudes [,,,,]. Research found that framing, as a crucial signal, leads to different perceptions and behaviors among employees who receive information. The use of gain framing by leaders can foster positive leader–subordinate relationships and stimulate employees’ perceptions of responsibility. Moreover, when presented in a gain framing, employees who have positive interactions with their leaders are better able to comprehend the leader’s expectations for achieving goals, fulfill their duties, recognize the importance of goal achievement for the leader, themselves, and the organization, and are more willing to engage in innovative behaviors to achieve the goals. Conversely, loss framing is negatively associated with employees’ innovative behavior and leader–subordinate relationships []. Additional research indicates that there is a goal framing effect in the impact of leaders on subordinates’ willingness for UPB, when the framing types fit the individual’s regulatory focus []. However, the current research on goal framing has drawn an overly simplistic conclusion, with insufficient investigation into the influencing process mechanisms. As research on goal framing advances and matures, it becomes necessary to move beyond simpler direct effects to understand the processes by which goal framing may influence cognitive responses. These cognitive responses may better explain the influence of framing effects on individual attitudes and behavioral outcomes [].

Furthermore, leaders play a critical role in aligning employee actions with organizational goals, and the effective communication skill is essential for alignment []. Leaders can utilize goal framing to influence employees and persuade them to take action towards achieving specific organizational goals by creating shared goals with them. Shared goal setting and communication between leaders and employees can enhance employees’ motivation to follow [,]. According to the social constructivist perspective, followership involves achieving organizational goals through individual or group efforts that are influenced by the leader in a specific situation []. The relationship between a leader and follower is characterized by interpersonal orientation, interactivity, and shared goals []. The way in which leaders communicate with their employees and construct their work goals affects employees’ willingness to follow and followership behavior. Research has shown that employees who actively follow have a stronger sense of responsibility and are willing to work together with their leaders to achieve goals []. This is of long-term significance for achieving sustainable organizational development. However, current research on how a leader’s goal framing influences employee followership behavior and the process mechanisms is insufficient.

Considering these limitations, to advance understandings about the effects of goal framing, the current study seeks to investigate the effects of goal framing on followership behavior and underlying boundary conditions under which these effects of goal framing are manifested. Drawing from social information processing theory (SIPT), this study aims to explore how leaders’ goal framing, namely gain framing and loss framing, impact employees’ followership behaviors through affecting employees’ work meaning in the condition of power dependence. SIPT suggests that an individual’s behavior is influenced by how they process and interpret specific information []. Goal framing comprises information about organizational goals and expectations conveyed from leaders to employees. Employees then process this framed information and compare it with their personal goals, values, and experiences to understand the underlying meaning of the frame in workplace. According to SIPT, this process can further influence their cognitive responses, such as work meaning, which in turn impact their followership behaviors. For instance, if the framed information aligns with employees’ values and is perceived as meaningful, it is more likely to motivate them to follow their leaders, commit to organizational goals, and actively engage in teamwork []. SIPT highlights that individuals’ behaviors are influenced by the social environment they are in, shaping the process of adjusting their actions based on social information. Furthermore, the power status of leaders enhances the persuasiveness of their discourse, making their disseminated information more influential and more easily accepted or convincing by others [,,]. Thus, this study proposed and analyzed the indirect relationship between gain–loss framing and followership behaviors through the mediation of work meaning and the moderation of power dependence.

This study enhances our understanding of the influence of leaders’ goal framing on employees’ followership behaviors from the perspective of social information processing theory. First, by studying the indirect relationship between goal framing and followership behavior, we gained insights into the cognitive mechanisms at play in the framing effect. This deepened our understanding of goal framing. Second, this study put forward a new view on the antecedence of active followership behaviors from the perspective of information. Third, by identifying power dependence as boundary conditions, this study extends the research on contextual factors of the influences of goal framing on employees’ work meaning and followership. It clarifies the conditions under which goal framing influences behavior in organizational contexts.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Social Information Processing Theory

The social information processing theory explains cognitive processes involved in how individuals receive, process, and respond to information. It suggests that attitudes and behaviors often result from the cognitive products of the social environment []. Prior to engaging in behavior, individuals typically go through several social information processing steps. These steps include encoding social cues, interpreting cues to identify others’ intentions or for self-evaluation, clarifying goals, and determining responses. These sequential steps lead to behavioral outcomes.

Social information has a dual effect on work attitudes and behavior. Firstly, it provides guidelines for socially acceptable beliefs, attitudes, and needs, along with acceptable reasons for action, thereby constructing meaning directly. Secondly, it directs an individual’s attention to specific information, enhancing its salience, and sets expectations for individual behavior outcomes [].

According to social information processing theory, job or task characteristics are not inherent, but rather constructed []. Leaders in organizations have the authority to control and influence employee work resources and career development. Therefore, leaders are critical social information sources for employees, constructing meaning for work-related factors. Daily interactions with leaders can help employees understand task goals, behavioral requirements, and expectations in the workplace, which can influence their behavior.

The social information processing perspective suggests that employees can form perceptions of their work by selectively perceiving and interpreting their social environment and past behaviors []. The characteristics of social information can influence the formation of these perceptions, and the sources and social background of information can also affect the salience of information and the interpretations formed. Therefore, the social information processing theory can explain how positive or negative goal frames transmitted by leaders’ impact employee followership behavior.

2.2. Goal Framing

In psychology, framing refers to how people process information []. Kahneman and Tversky (1981) found that people’s decisions are influenced by how the alternative options are described, showing a preference reversal phenomenon in their study on the ‘Asian disease problem’ []. This evidently contradicts the constancy principle of rational decision-making, and they termed this preference shift for alternative options due to semantic changes as the framing effect.

Levin et al. (1998) conducted a meta-analysis of interdisciplinary studies on framing effects. They categorized the framing effect into three distinct types: risky framing, attribute framing, and goal framing. The concept of the goal framing effect was initially defined by them []. The goal framing starts by outlining behavioral consequences, emphasizing positive outcomes of engaging in the behavior or negative outcomes of not participating, thereby influencing various behavioral decisions. Research has utilized the goal framing effect to explore the impact of different types of information or wording on willingness or behavior, focusing on whether positive or negative goal framing is more effective at persuading individuals toward certain behaviors [,,].

Several studies suggest that goal framing affects individual cognitive processes []. Goals direct attention, determine which knowledge and attitudes are most easily accessible cognitively, influence how people evaluate various aspects of situations, and guide the consideration of different options. Goals themselves reflect factors that motivate individuals in specific contexts. Activation of an individual’s goal significantly influences their current thoughts, sensitivity to information, perception of viable action choices, and subsequent actions []. Goals can also adjust dynamically based on the context, enabling selective processing of incoming information [].

Within organizational research, goal framing emphasizes how leaders interpret issues and shape contexts to foster collaborative efforts among organizational members, with the ultimate aim of achieving a specific goal []. In practical management, work structures are relatively fixed. However, leaders exhibit high flexibility in using different framing types to describe work characteristics and goals. Leaders can influence how employees interpret information by manipulating goal framing. Research has shown that employees’ attitudes and behaviors can be changed based on the positive or negative language used by leaders []. When leaders clarify the significance of work and provide contextual information to employees, they can influence their motivation for followership and behavior through specific responsive language forms and symbols [].

2.3. Followership Behavior

The main outcome of our study is followership behavior, which is a key indicator for measuring leadership effectiveness and a strategy for addressing cooperation and coordination issues within organizations [,]. Followership directly relates to whether the leader’s directives can be effectively implemented, consequently impacting the realization of organizational goals [,]. Research has summarized the motivation behind followership behavior, indicating that employees may engage in followership due to adherence to the formal position of leaders in society, a desire to achieve individual goals, seeking security and protection from superiors or leaders, and identifying with charismatic and powerful leaders []. Therefore, followership behavior is under the influence of leaders and is the result of considerations of both individual and organizational interests. Within the leader–follower relationship in organizations, the study of the framing effect helps us to gain insight into how a leader’s goal setting, goal-proposal, and goal-expression influence employees’ understanding and acceptance of work goals. This process can activate the followership motivation, which in turn shapes employees’ followership behaviors.

2.4. Formulation of Hypotheses

2.4.1. Goal Framing and Followership Behavior

The way information is presented significantly shapes people’s decisions. The phenomenon in which different descriptions of the same thing led individuals to make different behavioral decisions is known as the framing effect []. Specifically, the goal framing effect occurs when individuals opt for either gain or loss framing to convey ideas for persuasive purposes [,]. Positive goal framing focuses on the potential benefits or gains of a behavior, while negative goal framing concentrates on potential losses []. However, whether employing positive gain framing or negative loss framing, the fundamental aim remains to persuade individuals toward a specific course of action. According to social information processing theory (SIPT), individuals process and interpret social information, determining their attitudes and behaviors []. Therefore, the different expressions of gain framing and loss framing have distinctive impacts on individuals.

Followership behavior is guided by leaders and involves effective communication, helping leaders take responsibility and actively solving problems []. Whether employees choose to make a behavioral decision to follow the leader is closely related to the leader’s behavioral guidance, motivation, and positive and effective interaction between superiors and subordinates []. The way leaders describe goals not only offers strategies for employees to accomplish organizational goals but also accentuates specific information aspects within different framing types, influencing their decisions in followership behavior [].

The positive information conveyed through gain framing tends to enhance employees’ internal motivation, foster close cooperative relationships with leaders, and activate their consciousness of dedication, loyalty, and responsibility, consequently eliciting proactive followership behavior []. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

Gain framing is positively related to followership behavior.

However, this study posits that the loss framing approach might have a negative impact on employees’ proactive followership behavior. By emphasizing potential losses and negative outcomes at work, employees tend to focus more on avoiding failure than achieving success [,]. This cautious approach in decision-making reduces employees’ enthusiasm and motivation, resulting in decreased work motivation and performance. When leaders employ loss framing, it heightens employees’ sense of insecurity, leading them to take conservative actions to protect their interests rather than taking positive actions to solve dilemmas. Followership behavior involves employees voluntarily or unconsciously accepting a leader’s influence and engaging in efforts toward common organizational goals []. However, loss framing might lead employees to focus more on self-interest rather that cooperation for team or organizational goals. Therefore, the use of loss framing may have a negative impact on employees’ proactive followership behavior. This study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2.

Loss framing is negatively related to followership behavior.

2.4.2. Goal Framing and Work Meaning

Social information stems from the verbal expressions and behaviors of others, people form their cognition through observation and interpretation of this information []. Work meaning represents an individual-level cognitive factor that involves intrinsic interest in assigned tasks, emphasizing subjective feelings and experiential orientation. Unlike other objective job characteristics, such as task importance or skill diversity, work meaning is more proximal to individual cognitive evaluations. It directly reflects an individual’s subjective perceptions of work tasks and provides a more direct assessment of whether the work performed contributes to personal development. Previous research suggests that work meaning plays a positive role in work behaviors, work attitudes, work performance, work engagement, and other outcomes [,,]. Work meaning, therefore, provides individuals with a cognitive sense of the importance of work, and also influences individuals’ behavioral decisions in the workplace.

Leaders also play a crucial role in shaping or influencing work meaning. Leaders frame the organization’s mission, goals, purpose for employees and interpret and communicate various work events and environments, thereby influencing employees’ perceptions of work meaning [,]. Leaders who use gain framing can create a narrative of “gains” for employees, emphasizing the rewards and career advancements associated with work tasks. This activates strong work ideals and a sense of work meaning, fulfilling employees’ growth needs [,]. Thus, this study asserts that employees exposed to gain framing perceive the information as aligning with their expectations, attributing meaning to their work. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses can be inferred.

H3.

Gain framing is positively related to work meaning.

In contrast, when leaders adopt a loss framing perspective, it leads to a scenario of “loss” for employees, highlighting how poorly completing work tasks could result in personal performance and developmental losses. This engenders resistance toward work tasks, increased sensitivity to negative outcomes, and a diminished sense of work meaning among employees. In summary, this study posits that different types of goal framing actions influences employees’ perceptions of work meaning differently, as hypothesized below.

H4.

Loss framing is negatively related to work meaning.

2.4.3. The Mediating Role of Work Meaning

Regardless of whether leaders employ positive or negative goal framing with employees, the aim remains to effectively persuade employees to adopt followership behaviors. According to social information processing theory (SIPT), the types of goal framing conveyed by leaders to employees, whether positive or negative, can influence employees’ perception of information, thereby impacting individual behavior. As a cognitive factor, work meaning can influence employees’ work behavior and is related to employees’ evaluations of the personal interests []. Thus, employees’ work-related perceptions of ideas such as work meaning may serve as a bridge to convey the effects of goal framing on followership behavior.

Financial incentives can affect an individual’s sense of work meaning []. A positive framing highlights the potential gains and favorable outcomes of employees’ followership behavior, fostering resonance with the goals set by leaders and enhancing a sense of meaningful work []. Consequently, employees are more inclined to adopt followership behaviors, such as supporting leaders and investing effort in common goals, as hypothesized below.

H5:

Work meaning mediates the relationship between gain framing and followership behavior.

In contrast, loss framing accentuates potential losses, which makes employees more sensitive to failure, reduces their perceived meaning of work, and makes them more conservative in their behavior, thus weakening followership motivation []. Additionally, due to the loss framing, employees perceive that they are engaged in work that does not lead to additional personal advancement and career prospects, which can lead to a deterioration of well-being, undermining personal efficacy beliefs and a sense of purpose, and an unwillingness to engage in proactive behaviors to achieve their goals. This study suggested that gain and loss goal framing impact employees’ proactive followership behavior differently, with employees’ perception of work meaning playing a mediating role. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H6:

Work meaning mediates the relationship between loss framing and followership behavior.

2.4.4. The Moderating Role of Power Dependence

According to social information processing theory, the formation of individual cognition and behavior is influenced not only by the characteristics of information but also by sender- and individual-related factors []. In psychological studies, power is understood as controlling significant resources such as information or decisions or influencing the thoughts and behaviors (outcomes) of others [,]. Power dependence refers to the degree of control that a leader has over the goals and resources that employees value []. Specifically, goals reflect the states individuals want to achieve or avoid [], while resources reflect the means individuals need to achieve these goals []. Leaders wield influence by providing or withholding resources pivotal for employees’ goal accomplishment [].

Therefore, differences in employees’ dependence on leader power can affect the persuasive effect of goal framing, influencing employees’ perception of the work meaning. As critical resources necessary for achieving goals lie in leaders, highly power-dependent employees, upon receiving positive information conveyed through gain framing, find that goal framing is more attractive and relevant, enhancing the perception of work meaning []. However, upon receiving positive information through gain framing, low power-dependent employees perceive the information as relatively less attractive, thereby weakening its impact on their perception of work significance. Therefore, the present study considers power dependence as a moderating variable between gain framing and work meaning, as hypothesized below.

H7:

Power dependence moderates the relationship between gain framing and work meaning such that the relationship is stronger when power dependence is high rather than low.

Employees consider leaders with greater control over resources to be authorities []. The authority and influence of leaders can change employees’ responses to loss framing. Upon receiving negative information conveyed through loss framing, highly power-dependent employees might reduce their fear of negative outcomes. Consequently, they might prioritize understanding the leader’s intentions and goals, believing the leader’s statements rather than just focusing on the possible negative results. This significantly weakens the negative impact of loss framing on people’s perception of work meaning. Conversely, when exposed to information from loss framing, low power-dependent employees may not fully trust the leader’s authority. They focus more on personal losses and negative impacts and interpret negative framing information through their understanding of work meaning and values. As a result, this may reinforce the negative impact of loss framing on the perception of work meaning. Therefore, the present study considers power dependence as a moderating variable between loss framing and work meaning, as hypothesized below.

H8:

Power dependence moderates the relationship between loss framing and work meaning such that the relationship is weaker when power dependence is high rather than low.

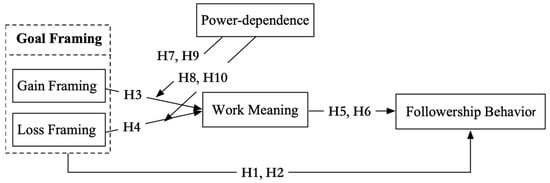

According to the above analysis, the level of power dependence explains how employees treat the power and resources controlled by leaders and, in turn, affects the acceptance of goal framing and their perception of work meaning. Therefore, for employees with different levels of power dependence, different goal framing leads to different behavioral outcomes []. This study further proposes an integrated research model, as shown in Figure 1, where employees’ power dependence positively moderates the indirect effect of gain framing on followership behavior through work meaning. Specifically, high power dependence strengthens the impact of gain framing on work meaning, prompting positive followership behavior. Conversely, low power dependence weakens the impact of gain framing on work meaning and subsequent followership behavior, as hypothesized below.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized moderated mediation model.

H9:

Power dependence moderates the indirect effect of gain framing on employees’ followership behavior through work meaning such that the indirect effect is stronger when power dependence is high rather than low.

Employees’ power dependence negatively moderates the indirect effect of loss framing on followership behavior through work meaning. Similarly, high power dependence mitigates the negative impact of loss framing on work meaning, indirectly influencing followership behavior. Conversely, low power dependence amplifies the negative impact of loss framing on work meaning, affecting positive behavior indirectly. This leads us to propose the following hypotheses:

H10:

Power dependence moderates the indirect effect of loss framing on employees’ followership behavior through work meaning such that the indirect effect is weaker when power dependence is high rather than low.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Participants

In this study, the online convenience sampling approach was used to distribute the questionnaires at three time points (every half month apart). The questionnaires were distributed to Credamo (https://www.credamo.com/ accessed on 30 December 2023), and the research subjects were limited to enterprise employees. Finally, the three waves of research data were matched by the ID of the participants identified by the Credamo. The specific research process is as follows:

In the initial phase (T1), 560 questionnaires were distributed in September 2023; these were focused on control variables and the independent variables—gain framing and loss framing. In phase 2 (T2), questionnaires were distributed to 560 participants who completed the first phase of the survey two weeks later, and a total of 483 valid questionnaires were collected, for an effective recovery rate of 86%. In this stage, employees’ work meaning is assessed. In phase three (T3), questionnaires were distributed to the 483 participants who completed the second phase two weeks earlier, for a total of 404 collected valid questionnaires, for an effective recovery rate of 83.6%. In this stage, the followership behavior and power dependence of employees are collected. According to the results of the three-phase survey, the overall sample recovery rate was 72.14%.

The sample was 41.6% male and 58.4% female. Regarding education, 84.7% held a bachelor’s degree or higher, with 68.1% having a bachelor’s degree. In terms of age distribution, 48.3% were aged 21–30 years, 38.9% were aged 31–40 years, 8.9% were aged 41–50 years, and 4.0% were over 51 years, indicating a predominantly younger demographic in the study. Most participants (77.7%) had between 2 and 10 years of work experience; 45.8% had 2–5 years of work experience, and 31.9% had 6–10 years of work experience. Concerning collaboration time with leaders, the majority (69.1%) had collaborated for 2–5 years.

3.2. Measurement

In this study, all the variables were adapted from existing scales. All the variables, their definitions, constructs, quantity of items and related reference sources are shown in Table 1 below. Except for the control variables, the variables were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). To ensure semantic consistency, we followed a back-translation procedure to obtain Chinese questionnaires. We also conducted a presurvey among MBA students (n = 30) to validate the translated scales. There was no semantic ambiguity in any of the items, and no one was confused when answering the questionnaire; therefore, the question of questionnaire bias was excluded. According to 404 prediction questionnaires, the predicted Cronbach’s α value of each variable is greater than 0.5, which basically indicates good internal consistency.

Table 1.

Measurement instruments.

Gain framing and loss framing were measured using the 6-item scale developed by Xu J. et al. (2019) []. Sample items included “My leader emphasizes the positive impact that work or tasks themselves can have on employees’ personal development” and “My leader tends to emphasize the actual or potential losses that may result from task failure”. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the scale were 0.764 and 0.825.

We adopted the work meaning scale developed by Steger et al. (2012), which includes four items, such as “I think the work I am engaged in is very meaningful” and “My work helps fulfill my life values and meaning [].” The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale was 0.847.

We assessed power dependence with the scale developed by Wee et al. (2017), which includes two items, “To what extent do you rely on your immediate superior to achieve your desired career goals (e.g., promotion)?” and “To what extent do you rely on your superiors for materials, methods, information, and other resources you care about? []” The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale was 0.551.

Followership behavior was measured with the scale developed by Christopher and Sharon (2015), which contains six items, such as “I actively complete tasks assigned by my leader” and “I am willing to support my leader. []” The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale was 0.806.

We included gender, age, education, organizational tenure, and collaboration time with leaders as control variables. Previous studies have shown that organizational tenure and collaboration time with leaders are relevant to followership behavior [,].

3.3. Data Analysis

In this study, SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 8.3 were used for the statistical analysis of the data. The statistical procedures were as follows: First, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Mplus 8.3 to assess the fit of the measurement model before estimating the structural model. Second, descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis were performed using SPSS 26.0. Finally, hypothesis testing was conducted using hierarchical regression analysis and the bootstrap method.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance (CMV) Test and Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs)

The data of this study were collected through self-reports by employees. Methods such as concealing the purpose of the research, randomizing questionnaire item arrangements, and introducing specific discriminating questions were used to control for CMV. Considering the potential existence of CMV, we conducted Harman’s one-factor analysis to examine all items of the five variables. The first factor accounted for only 35.589% of the total variance (less than 50%), indicating that CMV did not significantly impact this study [].

In this study, Mplus 8.0 was used for confirmatory factor analysis, and the analysis results are shown in Table 2. The five-factor model had the best fit (χ2/df = 1.125, CFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.994, RMSEA = 0.018). This model is significantly better than the other factor models, indicating that the discriminant validity of the five variables is acceptable.

Table 2.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the variables involved in this study. From Table 2, it can be observed that the gain framing is significantly positively correlated with work meaning (r = 0.478, p < 0.01), the loss framing is significantly negatively correlated with work meaning (r = −0.221, p < 0.01), the gain framing is significantly positively correlated with followership behavior (r = 0.472, p < 0.01), and the loss framing is significantly negatively correlated with followership behavior (r = −0.201, p < 0.01), providing preliminary support for research hypotheses H1, H2, H3, and H4.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Direct and Mediating Effect Testing

To examine the mediating effect, we adopted Baron and Kenny’s (1986) four-step mediation analysis method []. This study aimed to explore whether work meaning acts as a mediator between gain framing, loss framing, and followership behavior. First, we examined the impact of gain framing and loss framing on work meaning. Second, we examined the influence of gain framing and loss framing on followership behavior. We subsequently evaluated the impact of work meaning on followership behavior. If the first three steps are confirmed, we further analyze whether gain framing, loss framing, and work meaning affect followership behavior. If the effects of gain framing and loss framing on followership behavior are enhanced, weakened, or no longer significant, then the mediating role of work meaning is established. The empirical research results are shown as follows.

In examining the “gain framing–work meaning–followership behavior” pathway for linear regression relationships among variables, five models (Models 1 through 5) were constructed and assessed, as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of hierarchical regression analysis.

Model 1 included work meaning as the dependent variable and control variables as independent variables; these variables were subsequently entered into the regression equation. The results indicated that only gender, age, and collaboration time with the leader had linear regression relationships with work meaning among the control variables.

Model 2, based on Model 1, introduced the gain framing as an independent variable into the model. The results showed a positive correlation between gain framing and work meaning (B = 0.460, p < 0.001), indicating a strong positive predictive effect of gain framing on work meaning, thus confirming H3.

Model 3 takes followership behavior as the result variable and the control variable as the independent variable; these variables are included in the regression equation. The results show that there is no linear correlation between the control variables and followership behavior.

On the basis of Model 3, Model 4 puts the gain framing as an independent variable into Model 3. The results show that the gain framing is positively correlated with followership behavior (B = 0.034, p < 0.001), indicating that the gain framing has a positive predictive effect on followership behavior. Therefore, H1 is verified again.

Model 5, based on Model 3, included the gain framing as an independent variable. The results showed that work meaning significantly influenced followership behavior (B = 0.520, p < 0.001). Additionally, the gain framing significantly influenced followership behavior (B = 0.101, p < 0.001). The impact of gain framing on followership behavior was strengthened by the presence of work meaning, preliminarily validating the partial mediating role of work meaning between gain framing and followership behavior and confirming H5.

To further examine the mediating role of work meaning, this study employed the bootstrap method, as suggested by MacKinnon et al. (2004), setting 5000 iterations for resampling and a confidence interval of 95% []. SPSS-Process Model 4 was used to test whether work meaning had a mediating effect. The results are shown in Table 5. The confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effect is [0.160, 0.321], and the interval does not contain 0. Again, it can be verified that there is a significant mediating effect of work meaning between gain framing and followership behavior, providing further validation for H5.

Table 5.

Results of the indirect effect model from the fain framing to followership behavior.

In examining the “loss framing–work meaning–followership behavior” pathway for linear regression relationships among variables, five models (Models 6 through 11) were constructed and assessed, as summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of hierarchical regression analysis.

Model 7 took work meaning as the dependent variable and control variables as the independent variables and was entered into the regression equation. The results showed that among the controlled variables, only gender, age, and collaboration time had linear regression relationships with work meaning.

Model 8, built upon Model 7, introduced loss framing as an independent variable. The findings revealed a negative correlation between loss framing and employees’ work meaning (B = −0.158, p < 0.001), indicating a strong negative predictive effect of loss framing on work meaning, thus confirming H4.

Model 9 considered followership behavior as the outcome variable and the control variable as the independent variable, which is included in the regression equation. The results revealed no linear correlation between the control variables and followership behavior.

Model 10, an extension of Model 9, introduced loss framing as an independent variable. The outcomes revealed a negative correlation between loss framing and followership behavior (B = −0.109, p < 0.001), thereby reaffirming H2.

Model 11, built upon Model 10, incorporated both loss framing and work meaning. The findings indicated that work meaning significantly influenced employees’ followership behavior (B = 0.564, p < 0.001), while loss framing did not significantly influence followership behavior (B = −0.021, p > 0.05). This preliminary evidence suggests that work meaning fully mediates the relationship between loss framing and followership behavior, validating H6.

The mediating effect of work meaning between loss framing and followership behavior was also examined using SPSS-Process Model 4. The outcomes presented in Table 7 show the confidence intervals (CIs) for the indirect effects, ranging from [−0.132, −0.051]. This nonzero interval reaffirms the statistically significant mediation of work meaning between loss framing and followership behavior, providing further confirmation of H6.

Table 7.

Results of the indirect effect model from loss framing to followership behavior.

4.3.2. Moderating Effect Analysis

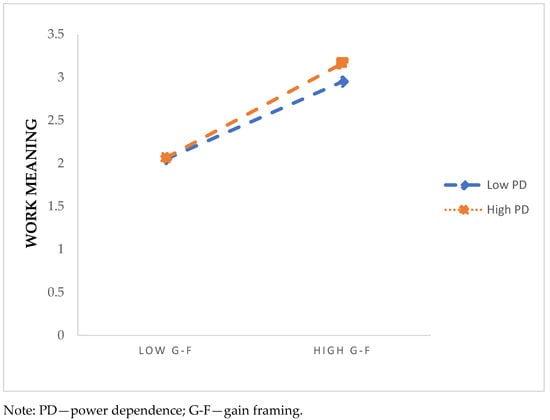

This study posits that power dependence moderates the positive relationship between gain framing and work meaning. This finding indicates that the stronger employees’ power dependence on the leader, the stronger the positive relationship between gain framing and work meaning. Similarly, it is theorized that this reliance negatively moderates the relationship between the loss framing and work meaning, such that the relationship is weaker when power dependence is high rather than low.

The analysis indicated that, after considering control variables, the interaction effect on power dependence and gain framing significantly influenced work meaning, with a coefficient of 0.099 and a confidence interval (CI) of [0.020, 0.177], excluding 0; thus, H7 was supported. However, the interaction effect between power dependence and loss framing had no significant impact on work meaning, as indicated by the confidence interval (CI) of [−0.074, 0.040]. Thus, H8 was not supported.

To show the moderating effect of power dependence more directly, a simple slope analysis was conducted in this study, and the results are shown in Table 8. High-level (+1SD) and low-level (−1SD) power dependence had positive moderating effects on both gain framing and work meaning. The simple slope plot is shown in Figure 2. As expected for H7, as the power dependence increases, the positive influence of the gain framing on work meaning (represented by the slope of the corresponding effect line in the plot) gradually increases.

Table 8.

Results of the moderating effect analysis.

Figure 2.

Interactive effects of G-F and power dependence on work meaning.

4.3.3. Moderated Moderating Effect Testing

SPSS-Model 7 was used to test the moderated mediation effect (bootstrapping 5000 times, 95% confidence interval), and the results are shown in Table 9. The indirect effect of gain framing on employees’ followership behavior through work meaning was significant at the high-power dependence level (β = 0.285, 95% CI = [0.167, 0.395], interval excluding 0). The results were also significant at low power dependence levels (β = 0.183, 95% CI = [0.108, 0.272], interval excluding 0), thus supporting H9.

Table 9.

Results of the moderated moderating effect analysis.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore how leaders’ gain or loss framing of job tasks influence employees’ perceptions of work meaning and their subsequent followership behavior. Based on the social information processing theory, the findings indicate that gain framing indirectly strengthens positive followership behavior by enhancing employees’ perception of work meaning, whereas loss framing indirectly inhibits followership behavior by decreasing this perception. Moreover, it was observed that power dependence strengthens the indirect influence of gain framing on followership behavior through work meaning. However, the role of power dependence in moderating the impact of loss framing on work meaning was found to be insignificant. One potential explanation is that when faced with loss framing, employees tend to be conservative in avoiding losses and are unwilling to invest time and effort in work involving loss risk.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

First, given that leaders serve as both disseminators of organizational information and constructors of work meaning, their influence on employees’ proactive followership behavior may be achieved by framing the way employees process information. This study applies SIPT to investigate the framing effect within leader–follower relationships, confirming that leaders’ goal framing impacts employees’ follower behavior. The research findings not only extend the application of SIPT, but also deepen our understanding of how social information influences employee behavior. It also provides new insights into the effects of goal framing. Previous studies on goal framing have often focused on exploring its effects on innovative behavior and ethical decision making from the perspectives of regulatory fit theory and cognitive appraisal theory, with a lack of research on employee followership behavior [,,]. This study, utilizing SIPT, specifically discusses how gain and loss framing have different effects on follower behavior thus enriching the research perspective and depth of goal framing studies.

Second, this study investigates the indirect influence of a leader’s goal framing on followers’ behavior through an intermediate pathway, addressing the previous research gap related to the lack of process mechanisms []. Specifically, it introduces cognitive influences into the goal framing effect based on SIPT, highlighting how gain and loss framing indirectly shape followership behavior by influencing work meaning []. Empirical findings confirm the mediating effect of work meaning. This understanding of work meaning contributes to revealing the complex dynamics of leader–follower interactions. Additionally, by initiating the exploration of cognitive factors, it enhances the depth of procedural research on goal framing within organizational behavior studies.

Finally, the study’s contribution of introducing power dependence as a moderator in the relationship between goal framing and followership behavior is significant. It provides a more nuanced understanding of leader–follower dynamics by highlighting the differential effects of gain framing on followership behavior based on the degree of power dependence. Previous research has focused mostly on the effects of the organizational environment and individual traits on the outcomes of leadership communication, neglecting the influence of power within the organization []. In particular, the impact of power dependence as a boundary condition has received limited attention in goal framing research. However, several studies highlight that power relationships frequently moderate a leader’s influence on employees. This study, grounded in SIPT, conceptualizes power dependence as a critical situational factor and represents a significant theoretical innovation. It examines the moderating impact of power dependence in the context of China’s high power distance culture and uses empirical evidence to reveal the varying effects of goal framing on followership behavior. The results indicate that for high power-dependent employees, the impact of gain framing on followership behavior was stronger, a finding that adds complexity to our understanding of how power interact with leadership strategies to influence employee behavior.

5.2. Practical Implications

First, organizations can incorporate the insights from this research into their leadership training programs. Leaders can learn about the powerful impact of goal framing on followership behavior by attending trainings on how goal framing affect perceptions of work meaning. The study’s results suggest that leaders can effectively influence followership behavior by strategically developing the content of goal framing. Therefore, leadership training programs could include understanding the impact of different framing strategies and how they can be used to mobilize employees’ sense of work meaning. This can enhance leaders’ ability to motivate and energize their teams, as well as improve communication strategies with subordinates.

Additionally, organizations can utilize the results of this study to enhance employee engagement and motivation. By integrating goal framing strategies with employees’ sense of work meaning, leaders can create a positive work environment where employees feel motivated to actively contribute to organizational goals. However, the study’s findings indicate that the negative impact of loss framing on follower behavior should be viewed with caution. Organizations can develop strategies to mitigate the potentially harmful effects of loss framing and ensure that employees maintain a strong sense of work meaning even in challenging situations.

Finally, recognizing the role of power dependence in shaping the strategic effectiveness of the goal framework, organizations can take steps to mitigate power differentials. For example, leaders are encouraged to adjust their leadership style and framing strategies to the specific characteristics and dynamics of their followers or team members. Leaders whose followers exhibit high levels of power dependence can increase follower engagement by emphasizing gain framing. This fosters a supportive and inclusive work culture where all employees feel empowered to achieve goals. Furthermore, organizations that aim to promote a positive workplace culture can use research findings related to the gain framing. Leaders can use gain framing information to improve employees’ perceptions of the importance of their work, potentially resulting in a more engaged workforce.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

First, although the data collected in this paper were divided into three time points, causal relationships were still not effectively verified. Future experimental studies can further test the robustness of the research conclusions. Second, framing effects may influence behavioral outcomes through an individual’s cognitive and emotional responses []. This study demonstrated the mediating role of job meaning, which could be further explored in future studies, and the mechanism through which emotional factors affect this process could be considered. Finally, we examined the moderating effect of power dependence on the influence of goal framing on employees’ work meaning and active followership behavior. However, the moderating effect of power dependence on how loss framing affects employees’ work meaning is not statistically significant. Therefore, future studies might draw on the perspective of regulatory focus theory to investigate how individual trait factors influence the relationship between goal framing and followership behavior.

6. Conclusions

This study explores how goal framing influence employees’ followership behavior. Drawing on SIPT, goal framing is innovatively regarded as social information cues for research. It was discovered that gain framing indirectly promotes followership behavior by increasing employees’ sense of work meaning. However, loss framing indirectly inhibits followership behavior by reducing employees’ sense of work meaning. In addition, our findings in the context of high cultural distance in China suggest that employees’ power dependence on leaders strengthens the positive correlation between gain framing and work meaning and further strengthens the indirect correlation between the gain framing and followership behavior. Our study emphasizes that the style in which leaders describe goals to followers has multiple effects (e.g., negative and positive effects) on followers’ behavior, providing new insights into the complex dynamics of leader–follower interactions, deepening the cognitive hierarchy of research on the goal-framing effect, and adding to the understanding of the mechanisms by which the goal-framing effect operates in organizational contexts. Additionally, the results of this study improve the application of the SIPT and expand the scope of its explanatory power.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.X. and W.S.; formal analysis, M.X.; investigation, W.S. and F.W.; resources, W.S.; writing—original draft, M.X.; writing—review and editing, M.X. and F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical review and approval, following local legislation and institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are highly confidential. However, they can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request from the editorial board representative.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lau, D.C.; Liden, R.C. Antecedents of Coworker Trust: Leaders’ Blessings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The Framing of Decisions and the Rationality of Choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez, D.Z. Challenge versus threat effects on the goal–performance relationship. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2002, 88, 667–682. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.B.; Li, S.; Liang, Z.Y. Behavioral decision making is nudging China toward the overall revitalization. Acta. Psychol. Sin. 2018, 50, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerend, M.A.; Cullen, M. Effects of message framing and temporal context on college student drinking behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shang, Y.F.; Zhao, X.Y. A study of the relationship between university research team leader’s linguistic framing and follower’s innovative behavior. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 20, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.F.; Xu, J.; Zhao, X.Y.; Xu, X.L. Study of Knowledge Hiding in Scientific Research Teams of Universities Based on Regulatory Focus Theory in Web2.0 Situation. Sci. Res. Manag. 2016, 11, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, K.A.; Ziegert, J.C.; Capitano, J. The Effect of Leadership Style, Framing, and Promotion Regulatory Focus on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Yufan, S. Leader’s Linguistic Framing, Followers’ Chronic Regulatory Focus and Followers’ Work Attitude. J. Manag. Sci. 2011, 24, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, R.L.; Walter, N.; Oshidary, N.; Endacott, C.G.; Love-Nichols, J.; Lew, Z.J.; Aune, A. Can Emotions Capture the Elusive Gain-Loss Framing Effect? A Meta-Analysis. Commun. Res. 2020, 47, 1107–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välimäki, M.A.; Lantta, T.; Hipp, K.; Varpula, J.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y.; Chen, W.; Hu, S.; Li, X. Measured and perceived impacts of evidence-based leadership in nursing: A mixed-methods systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e055356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Stam, D. Visionary Leadership: The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, M.K.; Uhl-Bien, M.; West, B.J.; Patera, J.L.; Mc Gregor, R. Exploring social constructions of followership: A qualitative study. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, K.A.; Bezrukova, K. A field study of group diversity, workgroup context, and performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 25, 703–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Maher, K.J. Leadership and Information Processing: Linking Perceptions and Performance; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Riggio, R.E.; Lowe, K.B.; Carsten, M.K. Followership theory: A review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalesny, M.D.; Ford, J.K. Extending the social information processing perspective: New links to attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 47, 205–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipnis, D. Does power corrupt? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 24, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.M.; Aguinis, H. Accounting for subordinate perceptions of supervisor power: An identity-dependence model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis. An Essay on the Organization of Experience; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, I.P.; Schneider, S.L.; Gaeth, G.J. All frames are not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 76, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, D.; Meyers-Levy, J. The Influence of Message Framing and Issue Involvement. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Guo, Y.; Hu, D. Information framing effect on public’s intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccination in China. Vaccines 2021, 9, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.S.; Yu, J.J.; Ni, S.G.; Li, H. Reduced framing effect: Experience adjusts affective forecasting with losses. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 76, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Goal-framing theory and norm-guided environmental behavior. In Encouraging Sustainable Behavior: Psychology and the Environment; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Normative, Gain and Hedonic Goal Frames Guiding Environmental Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benford, R.D.; Snow, D.A. Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 611–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matshoba-Ramuedzisi, T.; de Jongh, D.; Fourie, W. Followership: A review of current and emerging research. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022, 43, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Foti, R.J.; De Vader, C.L. A test of leadership categorization theory: Internal structure, information processing, and leadership perceptions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1984, 34, 343–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastardoz, N.; Van Vugt, M. The nature of followership: Evolutionary analysis and review. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.H.; McDonald, B.D.; Park, J.; Yu, K.Y.T. Making public service motivation count for increasing organizational fit: The role of followership behavior and leader support as a causal mechanism. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2019, 85, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, D. Rethinking followership: A post-structuralist analysis of follower identities. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, S.; Zou, Z. Power and message framing: An examination of consumer responses toward goal-framed messages. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 16766–16775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; He, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, H. How does loss-versus-gain message framing affect HPV vaccination intention? Mediating roles of discrete emotions and cognitive elaboration. Curr. Psychol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, K.; Nordlund, A.; Jansson, J.; Nilsson, J. Goal Framing as a Tool for Changing People’s Car Travel Behavior in Sweden. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimotakis, N.; Lambert, L.S.; Fu, S.; Boulamatsi, A.; Smith, T.A.; Runnalls, B.; Corner, A.J.; Tepper, B.J.; Maurer, T.J. Gains and Losses: Week-To-Week Changes in Leader–Follower Relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2023, 66, 248–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. Analysis of Researches on Implicit Followership Theories in Organization and Future Prospects. Adv. Psychol. 2019, 9, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berson, Y.; Halevy, N.; Shamir, B.; Erez, M. Leading from different psychological distances: A construal-level perspective on vision communication, goal setting, and follower motivation. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieglmeyer, R.; Deutsch, R.; De Houwer, J.; De Raedt, R. Being moved: Valence activates approach-avoidance behavior independently of evaluation and approach-avoidance intentions. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, A.J.; Thrash, T.M. Approach and avoidance temperament as basic dimensions of personality. J. Personal. 2010, 78, 865–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieglmeyer, R.; De Houwer, J.; Deutsch, R. On the nature of automatically triggered approach–avoidance behavior. Emot. Rev. 2013, 5, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, B. The personality of followers and its effect on the perception of leadership—An overview, a study and a research agenda. Small Group Res. 2006, 37, 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R. D.Measuring Meaningful Work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolny, J.M.; Khurana, R.; Hill-Popper, M. Revisiting the meaning of leadership. Res. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, M. Toward a Theory of Followership. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2011, 15, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipfelsberger, P.; Raes, A.; Herhausen, D.; Kark, R.; Bruch, H. Start with why: The transfer of work meaningfulness from leaders to followers and the role of dyadic tenure. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 1287–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.I.; Monge, P.R. Social Information and Employee Anxiety about Organizational Change. Hum. Commun. Res. 1985, 11, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, N.J.; Sivanathan, N.; Mayer, N.D.; Galinsky, A.D. Power and overconfident decision-making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2012, 117, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Gruenfeld, D.H.; Anderson, C. Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, E.X.M.; Hui, L.; Dong, L.; Jun, L. Moving from Abuse to Reconciliation: A Power-Dependence Perspective on When and How a Follower Can Break the Spiral of Abuse. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 2352–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.J.; Edelstein, R.S. Emotion and memory narrowing: A review and goal-relevance approach. Cognit. Emot. 2009, 23, 833–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinote, A. Power and goal pursuit. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Interdependence, Interaction, and Relationships. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, R.E. Interpersonal Power: A Review, Critique, and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 136–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molm, L.D. Affect and Social Exchange: Satisfaction in Power-Dependence Relations. Am. Soc. Rev. 1991, 56, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumm, C.A.; Drury, S. Leadership that empowers: How strategic planning relates to followership. Eng. Manag. J. 2015, 25, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, J.; Walker, D.O.H. Leaders mentoring others: The effects of implicit followership theory on leader integrity and mentoring. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 2688–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L.S.; Rosen, C.C.; Gajendran, R.S.; Ozgen, S.; Corwin, E.S. Pain or gain? Understanding how trait empathy impacts leader effectiveness following the provision of negative feedback. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mac Kenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, S.; MacDonald, P. A Look at Leadership Styles and Workplace Solidarity Communication. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2019, 56, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).