Abstract

Despite the presence of numerous navigable rivers in Brazil, they remain underutilized for Inland Waterway Transport (IWT). Given the recent changes in transport systems which aim to reduce reliance on highways due to their high cost and lack of sustainability, it becomes crucial to explore new transport models in Brazil, shifting part of the transport from roads to railways and mainly to waterways. To fill this gap in Brazil’s transport system, it was decided to check why waterways are little used and what challenges cause them to be underutilized and, additionally, what opportunities could leverage their use in the country. In this sense, in this study, we identify the biggest challenges and opportunities faced by IWT in Brazil. To achieve this objective, interviews were conducted using content analysis with managers who work in public and private IWT organizations active in Brazil. Results show that IWT has seen a recovery in interest in recent years due to the need for cheaper and greener logistics. It was also found that the main challenges that IWT faces are a lack of public policies followed by precarious infrastructure of waterways, ports and locks, as well as modest integration with other transport modes. Conversely, the most significant opportunity lies in the potential reduction in transport costs, coupled with the enhanced sustainability of transport activities via the utilization of IWT, thereby fostering greener transport practices. These results can contribute to a better understanding of practical and theoretical approaches related to IWT in Brazil, and they can serve as a reflection for new research focusing on the development of IWT especially in other emerging countries facing similar issues.

1. Introduction

Currently in transport research, there is a tendency to carry out research related to new transport models, many of them seeking better efficiency in relation to cost and sustainability. In order to improve efficiency, it is essential to obtain a greater balance in the use of transport modes, mainly trying to reduce transport by road and increase transport by railroads and mainly rivers [1,2,3].

Carrying out this study in Brazil is very important because there is a high predominance of road transport in the country in addition to few studies and public policies for Inland Waterway Transport (IWT). Considering that the situation of public policies for IWT may be similar in some countries, especially in emerging countries, this study can bring academic contributions in this way, unlike Europe and China, which stand out in terms of IWT research, mainly in recent decades. Researchers have highlighted the growth of IWT in China after the National Plan for the Yangtze River Economic Belt Development [4] and the increase in European policies after 2010 for IWT [5]. These policies to encourage IWT result in government investment, which in Europe and China has been increasing recently, but in Brazil, investments in IWT are still limited, being applied almost exclusively to highways [6]. Thus, given this lack of research, public policies and investments make the Brazilian transport system different when compared to Europe and China transport systems as well as less efficient. This is mainly because Brazilian transport uses few railways and even fewer waterways, which are more sustainable and cheaper modes. So, changes are needed in the Brazilian transport system.

The transport is included in the field of logistics studies, which traditionally has the objective to deliver the right products at the right time, but later, studies on supply chain management (SCM) emerged, which integrated different other actors in the logistics chain [7]. Today, logistics activities are even more complex, because the market has increasingly demanded that companies deliver their products faster and at the lowest possible cost in addition to delivering the product in perfect conditions of use and in a sustainable way. Thus, in order to be able to meet these market requirements, companies must always adjust their logistics processes, developing them continuously.

What hinders these logistics adjustments in Brazil is the great predominance of road transport, limiting logistics operators in finding new ways to deliver products with reduced costs and greater sustainability due to the limited use of railways and mainly waterways. Improving logistics efficiency in relation to transport in Brazil has become challenging due to the inherent difficulty of reducing costs associated with road transportation. Road transport inherently carries higher costs and is less sustainable. In this sense, it is important to use intermodal transport, distributing part of road transport to other modes, like railways and waterways [3]. Considering this shift in transportation, waterways stand out, because IWT is more sustainable and cheaper and uses less energy [8,9]. The only limitation relation to IWT is the fact that it is the slowest mode. However, with proper planning, this limitation can become an opportunity, as managers can use this longer transport time to store products while they are in transport, reducing costs with storage in warehouses.

Intermodal transport offers the possibility of utilizing multiple modes of transportation simultaneously, involving at least two modes [10]. In this format, an input or product can, for example, be transported for the main long haulage by railway or waterway, while the road is used in pre-transport or post-transport of the total route [2,11] in addition to many other possibilities, according to the availability of modes in the region. Thus, as railways and IWT have lower costs and are more sustainable, they can contribute by significantly reducing costs and increasing sustainability in the Brazilian transport system. This is mainly because according to the Brazilian Ministry of Ports and Airports [12], there are 15 waterways in Brazil which could be used to assist in efficient intermodal transport in the country. Most waterways have large extensions, such as the Amazonas Waterway with a length of 1640 km, the Tocantins–Araguaia Waterway with 1650 km, the Sao Francisco Waterway with 2350 km, the Tietê–Paraná Waterway with 1080 km, and the Paraguay Waterway, which in 3440 km interconnects Brazil with Paraguay, Uruguay, Bolivia and Argentina [12] in addition to other, smaller waterways that could also be very important.

As IWT has the lowest cost and is the most sustainable transport mode, and considering the high potential for its use in Brazil, in this research study, we decided to analyze why this mode remains underused in the country. Another motivator for the research is that research related to IWT in Brazil is scarce. In addition, the research can help in the development of the Brazilian transport system via the analysis of cheaper and more sustainable alternatives for transport via waterways and can also help other countries, especially emerging ones, that may have similar situations.

The cost reduction is significant, as logistics costs in Brazil constitute a larger proportion of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) when compared to the United States and Europe [13]. These high logistics costs impact the exportation of Brazilian commodities and goods, as their final price is becoming less competitive compared to other countries. Thus, Brazil has to improve its logistics system, and intermodal transport is the best alternative for this, mainly using waterways. As this research can facilitate a better understanding of how IWT in Brazil can contribute to the improvement of the Brazilian transport system, this research fills a gap that is important and can also contribute to reflections and analyses of logistics and mainly transport systems in other countries, especially emerging countries.

To reach the aim of this research, interviews with managers who work in activities related to IWT in Brazil were carried out. These interviews were critical to identifying the main challenges and opportunities that the IWT activity faces in the country, which was the aim of the research. Thus, this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical background, which is followed by Section 3 with the research method. Section 4 presents the results and discussion, and finally, Section 5 contains the research conclusions and contributions.

2. Theoretical Background

Currently, logistics is much more than delivering the right goods to the right place at the right time and being efficient with SCM [7]. As early as 2007, Ballou emphasized the significance of various factors related to supply chain management (SCM). These include income generation, expanding the SCM frontier, coordination challenges, information sharing, bottleneck identification, and opportunity recognition. Addressing these aspects requires more refined methods and the need for excellence in logistics management, considering all stakeholders and merging different organizational departments with logistics [7]. Since 2007, over the years, these issues became even more complex with emphasis on product quality (no damage during transport), speed, cost reduction and sustainability.

The first part seems pretty obvious, as it is a common expectation for products to be delivered to consumers promptly and in a suitable condition for their intended use. Regarding costs, they are expected to be reduced through innovations in processes, approaches and management, which results in organizational development. And this development and cost reduction in logistics can be achieved more easily using more IWT. Gharehgozli and Zaerpour [14], for example, considering the Rotterdam Port region, verified that the cost of barge transportation is EUR12.6 per thousand ton-kilometers, while by train is EUR45.21 and by truck is EUR48.42. These values may vary according to the region, but normally, the barge transportation cost corroborates the data reported by the authors, as normally, the IWT costs are about four times less than train or truck, and they require low investment in maintenance and expansion [14].

Considering the containerized transport, the waterways also stand out in relation to costs as there has been a growth in containerized transport over the last two decades, and in this sense, the IWT of containers is attracting increasing interest as a reliable and cheaper alternative to roadway transportation [15]. Containers can also contribute to less congestion in urban areas and in ports due to their practicality in being transferred from sea to river vessels instead of trucks [16,17].

In addition to the market requirements related to quality, speed and cost, society is currently very aware of sustainability. In this regard, Porter and Kramer [18] affirm that companies that adopt sustainable practices acquire a competitive advantage over competitors that do not. That is why firms do not want their names associated with unsustainable practices, considering that the concern for the environment is increasing nowadays [19,20]. In this context, companies that fail to meet these requirements end up having difficulty competing in the market.

It is also necessary to add that the market has demanded increasingly efficient logistics processes, using available resources in the best possible way to turning logistics green. For logistics to become greener, especially in the case of Brazil, it becomes necessary to use more waterways mainly because their use has several benefits. According to the European Commission [9], transport by waterways consumes only 17% of the energy consumed by roads and 50% of the energy consumed by railways. Moreover, it is considered to be seven times more sustainable compared to other modes [8]. Therefore, waterways are the most sustainable mode, mainly for its high fuel efficiency when compared with truck and rail [1]. In addition to its energy efficiency, IWT also contributes to lower GHG emissions [11,21,22]. Furthermore, it contributes to reduced congestion in densely populated regions as well as less noise, and it also offers more security, especially in the transport of dangerous products [9,23].

In this way, with greater balance in the use of transport modes, especially with the use of waterways, logistics could become greener and cheaper. Especially in Brazil, where transport by road predominates, and it is necessary to seek more sustainable means of transport [24], changing transport from roads to waterways [1,3,8,14,19,25,26,27,28,29]. For this reason, in recent years, there has been a renewed interest in IWT [30,31].

To achieve a greater use of IWT, it is necessary to connect the transport modes. Because the IWT does not work without the other modes, it is dependent on them. Thus, it is necessary to create intermodal terminals, which are places that combine two or more modes, [30,32]. For this reason, the intermodal terminals can be interpreted as a chain of actors that provide a transport service [33]. And because it is a chain, they end up having more complex combinations of intermodal transport, needing additional research [34]. It is also necessary to highlight the importance of inland ports of the waterways, which by promoting the connection of the logistics transport system with other ports and other modes end up becoming logistics centers and contribute to the development of less populated regions, [35,36]. According to Onden et al. [32], these logistics centers involve various activities related to logistics, such as distribution, storage, transport, consolidation, handling, customs clearance, imports, exports, transit processes, infrastructure services, insurance and banks, and they can contribute to the development of smaller cities in inland regions.

Many logistics centers could be created in Brazil. According to the Ministry of Infrastructure of Brazil [12], there is a good number of connections between modes in the country. However, the almost exclusive use of highways makes these connections deactivated over the years, hindering intermodal transport. As a result, the waterways end up being little used, too.

In this context, it is crucial to enhance the intermodal transport infrastructure in Brazil. This approach can significantly contribute to reducing costs and promoting sustainability [14]. This cost reduction is important because according to data from 2022, the percentage of logistics costs in Brazil represents 12.5% of the country’s GDP, which is a high number compared to 10% in Europe and 8% in the USA [14]. There has already been an improvement, as according to the CNT in 2016, this cost was 12.7% of the Brazilian GDP [37]. But this percentage needs to decrease further so that Brazilian products can be more competitive in the international market.

To reduce the costs, it is necessary to create public policies for IWT in Brazil and rethink the Brazilian transport system, balancing the use of transport modes. In this sense, public policies are very important to the development of IWT, because IWT consider human health impacts [11]. It is necessary to do what Europe has been doing for some decades now, creating public policies for IWT and replanning its logistics systems mainly considering transport in search of greater efficiency, as seen in 2013 when Europe focused on quality assurance in IWT [38]. In this sense, the emerging countries like Brazil and others must also adjust their logistics systems, following China’s and European countries’ lead. Jiang et al. [36] point out that although investments in waterways have been growing in recent years in China, especially in the last decade, when around 200 billion were invested in the Yangtze and Pearl rivers, investments are still not enough. And Lee and Lam [39] highlight the importance of the government for the development of ports in China. But unfortunately, the same does not occur in Brazil, where considering the increments of Brazilian government investments comparing the years 2022 and 2023 for transport infrastructure, 90.03% will be destined for highways, 5.8% for waterways, 1.0% for railways, 2.1% for air and 0.7% for others, [6]. This proves the great predominance of road transport in Brazil and the importance of changes related to public policies for the development of IWT in the country.

Public policies for IWT are a challenge in Brazil, as there are few. In this sense, Yu et al. [40] present some necessary incentive policies for IWT that can help Brazil and other emerging countries, such as the creation of subsidies related to river activities, reduction in service fees, subsidies for the acquisition of vessels, and incentives for the creation of companies to operate in IWT, among others. It would also be interesting to have an entity supporting the activity, acting in Latin America in the same way that the European Commission acts on the European continent. In Brazil, there is the Agência Nacional de Transportes Aquaviários (ANTAQ), in English the National Waterway Transport Agency, which was created in 2001 and is affiliated with the Ministry of Ports and Airports of Brazil, and its responsibilities are regulation, granting, inspection and the production of knowledge [41]. ANTAQ strives to increase the IWT activities, including carrying out feasibility studies for IWT, such as the study of Regulatory Obstacles to Multimodal Transport, among others [41]. But unfortunately, such efforts come up against few public policies for IWT in the country.

Regarding the availability of qualified labor for IWT, the works by Lendjel and Fischman [26] and Li and Yip [35] mentioned scarcity, but it is not a very widespread subject in the literature. In Brazil, the scarcity is because IWT is little used in the country.

Many authors point out that the availability of research on IWT is still small, and it is difficult to organize and implement changes related to IWT due to lack of knowledge [31], which is mainly because only in recent decades has the activity attracted attention. But in relation to Brazil, the situation is even more worrying. For example, Bu and Nachmann [1] researched containerized barge transport and did not find any articles in Africa and South America. When we searched in Scopus considering in the article title the keywords “inland waterway” and Brazil, only one paper was found [42] that analyzes the investment in inland waterway infrastructure projects, taking into consideration allocative efficiency, the effect on regional development and environmental impact. And when we searched using the terms “inland waterway” and “South America”, no articles were found. When searching using the term “inland waterway” and the United States of America (USA), five papers were found. It is worth mentioning the oldest by Perakis [43] that highlights the savings that IWT can provide to logistics, Chi and Baek [44] emphasizing the importance of grain transportation on the Mississippi waterway in the USA, and Farazi et al. [45] addressing political and institutional challenges for IWT in Illinois in the USA. When searching using the term “inland waterway” and China, 17 papers were found with important research on IWT. Key papers included Lu et al. [31] considering the growth of IWT in China 1978–2018, the analyses of Yu et al. [40] and Li et al. [46] on public policy for the IWT in China, and others. When searching using the term “inland waterway” and Europe, 12 articles were found, but when Germany was included, for example, eight articles were found. Thus, as there are many countries on the European continent, the number of papers on the continent addressing IWT is greater in relation to other continents. The strong role of the European Commission for IWT supports research and development on IWT in the European continent.

Thus, there is an urgent need for research on IWT in Brazil. In this sense, studies like that of Lu et al. [31] that show how China has developed its IWT in recent decades can help emerging countries like Brazil and others develop their IWT as well. The authors also point out that there is much room for expansion related to IWT, as the volumes transported by the main rivers in the world, including the Amazon River in Brazil, are much smaller than their capacities, [31].

As little research was found in preliminary analyses considering IWT in Brazil, the authors decided to take a step back and conduct research to better understand the context of IWT in Brazil. Thus, the objective was to analyze the main challenges and opportunities of IWT in Brazil. After carrying out this research and better understanding of the situation of IWT in Brazil, the authors can analyze more specific questions about IWT in the country in future research. It may also serve to assist research by other researchers, mainly from other developing countries, facilitating the collaborative development of the IWT literature related to Brazil and other developing countries.

3. Materials and Methods

To analyze the main challenges and opportunities of IWT in Brazil, deep interviews were carried out with specialists who work in activities related to Brazilian IWT. The searches for the interviewees were based on research on the inland waterway ports of Brazil listed on the Brazilian Ministry of Ports and Airport’s website [12,13]. On this website, there is information about the inland waterway ports in Brazil, and from this information, the researcher went in search of interviewees. Another source of interviewees was the ANTAQ website, which contains documents with companies that work with IWT in Brazil [41].

The search for interviewees to contribute to the research was difficult, because despite having a significant amount of inland waterway ports on the list of the Brazilian Ministry of Ports and Airports [12], most of these inland waterway ports are inactive. There was also difficulty in searching for interviewees with managers in the private sector, because many contacts of companies listed on ANTAQ [41] probably are not updated. Thus, most of the calls made to the telephone numbers listed on the webpage of ANTAQ [41] were not answered as well as the emails sent. Faced with this challenge, it was predicted that the number of respondents at the end of the survey could be reduced, and from that it was decided to explore these respondents in depth in order to have a rich sample.

In order to try to increase the number of interviewees, the snowball technique was used. The snowball technique is well known and widely used in varied fields of research as well as in transport, as in the research by Nalmpantis et. al, [47], Li and Zhao [48], Calastri et al. [49], and Barros et al. [50], among others. The snowball technique is appropriate for accumulating more interviewees to generate more data. In this sense, the interviewees were asked if they could indicate another person with good knowledge of the topic to participate in the interview. After significant effort, with this approach, it was possible to reach a total of 11 interviews, 8 of which were carried out using the interview script and another 3 interviews carried out in a complementary way.

The eight main interviewees acted as managers of public and private organizations, as shippers (private section), public port managers, and public managers responsible for IWT, such as city hall transport managers, for example. The three others, categorized as complementary interviewees, acted as a lieutenant of the Brazilian Navy, a president of an inland waterway workers union of the Tietê-Paraná Waterway region and a retired ship captain responsible for the Pirapora Vapor Museum, which is a museum of old ships powered by steam using firewood. These three other interviews were considered complementary interviews, not following exactly all the questions in the interview script, approaching the questions more freely.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that these three complementary interviews contributed significantly to the enrichment of discussions and reflections about the research. This was mainly because, like the other eight interviewees, the three complementary interviewees work in daily activities of IWT and therefore contributed with important complementary information that was only possible to be collected due to the freer nature of the interview that was applied to them. This research strategy helped to significantly enrich the research, as according to Grobarcikova and Sosedova [51], it is impossible to propose theoretical approaches for IWT without taking into account the day-to-day reality.

Faced with the already reported difficulty in carrying out the interviews, it was decided to delve deeper into the interviews using the interview script in order to have a rich sample of the personal situation. In this way, even with a not large number of interviewees, with eleven interviews, the interview script allows a greater immersion in relation to the theme as the interview script had a total of thirty-seven questions covered in depth.

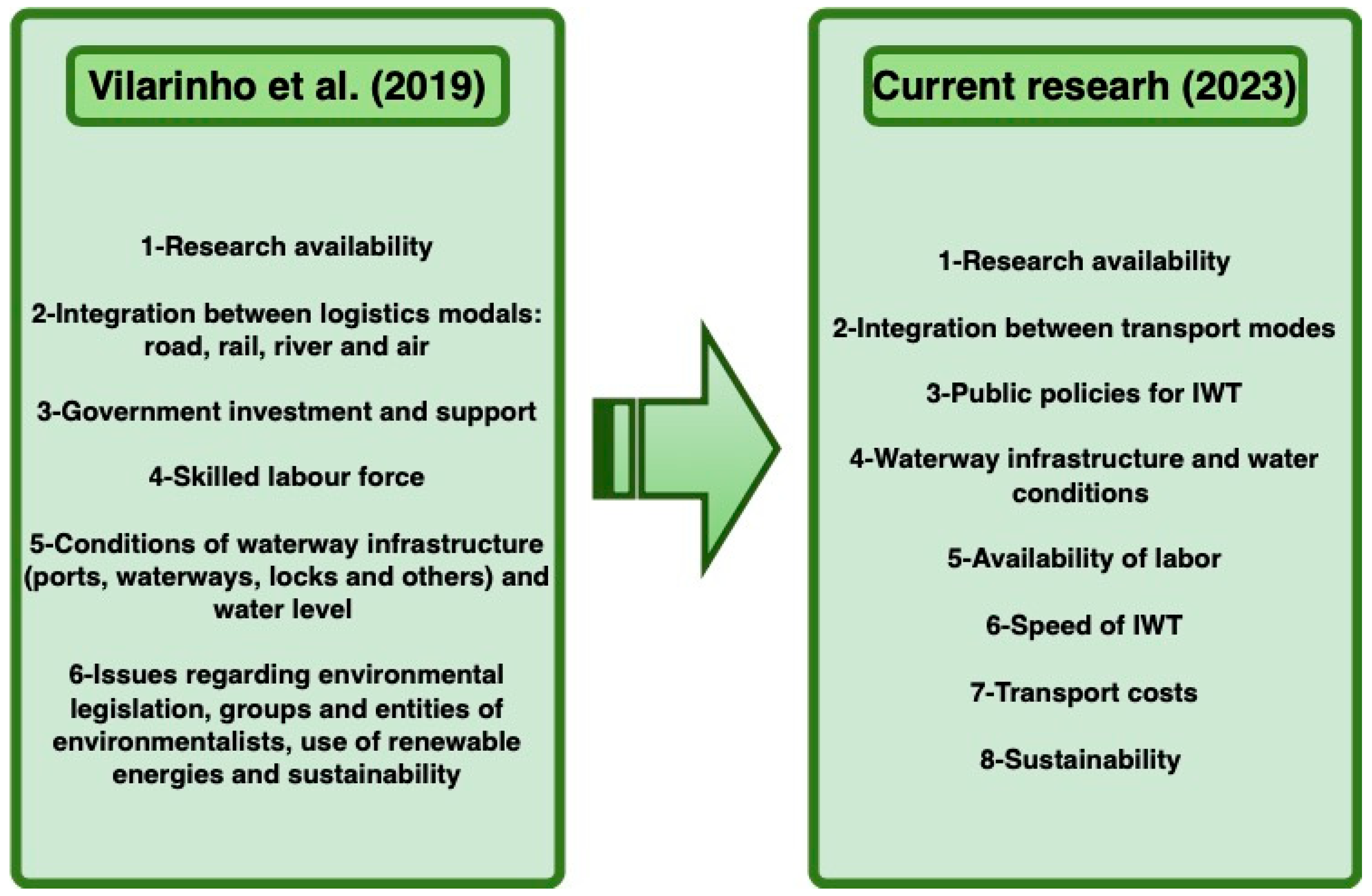

The interview script was developed based on eight main topics: (1) research availability, (2) integration between transport modes (road, rail, river and air), (3) public policies for IWT (investment and support), (4) waterway infrastructure (ports, waterways, locks and others) and water conditions, (5) availability of labor, (6) speed of IWT, (7) transport costs and (8) sustainability (environmental legislation, non-governmental organization-NGO and entities, renewable energies, others). These eight topics were identified after previous studies on the topic, such as the one carried out by Vilarinho et al. [52], who identified six main topics. After carrying out additional readings on the topic, it was decided to adjust these six topics and include two others. Thus, with these eight topics, the main issues related to IWT challenges and opportunities considering the Brazilian case are believed to be present in the study. Figure 1 below shows the evolution of the topics studied.

Figure 1.

Evolution of researched topics. Source: adapted from Vilarinho et al. [52].

The first questions in the interview script aimed to verify the profile of the interviewees and the companies they operated; respondents were also asked if they believed there was a recovery of interest in IWT in Brazil, which was followed by questions about the challenges and opportunities of the IWT in Brazil as well as the ways to overcome the challenges and strengthen the opportunities; and finally, the eight main topics of challenges and opportunities of the IWT in Brazil were addressed.

The questions were carefully structured to be as clear as possible. And as many of the questions were too long, a chart was constructed with the summaries of the questions so that readers could become familiar with the themes that were addressed in the interview. This chart is available in Appendix A in Table A1 at the end of this article.

As the interview script was long, the interviews lasted about an hour, some with even longer durations when it was noticed that the interviewees really enjoyed working with IWT and felt the need to further explore the topics addressed. Therefore, in these cases, some interviewees ended up bringing a lot of other related information and also went deeper into some explanations about some the questions of the interview script.

To analyze the collected data, the content analysis methodology was used, an approach created by Bardin [53] that, through systematic procedures, allows the researcher to obtain information that allows the inference of knowledge. Krippendorff [54], and other authors, improved Bardin’s methodology, bringing it to a more current context, and consulting these studies, it was found that the methodology fits very well in the context of IWT in Brazil, as it is a topic that is not much researched, where through interviews, it was possible to obtain inferences about the themes of the interview script.

4. Results and Discussion

The results and discussions about the researched topics were separate into two topics, which are outlined below.

4.1. Information about the Search Process of the Interviewees and Ports Situation

From the interviews, it was verified, and later confirmed through research on the internet pages of the Brazilian Ministry of Ports and Airports and ANTAQ, that these totally inactive or partially active ports in most cases are under the responsibility of the Brazilian government: some under the responsibility of the federal government, some under the responsibility of the state government and in other cases under the responsibility of municipalities. And these government entities have paralyzed inland waterway activities and disabled many ports. This practice of deactivating ports was very common in the second half of the last century in Brazil, as there was a great expansion of highways in the country and the fuel was still cheap. For this reason, the intermodal terminals were disabled over the years. But it is important to highlight that from the interviews, it was possible to verify that there are currently movements to reactivate these ports and create intermodal terminals, which is mainly due to the need for cheaper and greener logistics through intermodal transportation. In this sense, some public ports are being reactivated, or concession contracts are being made to private firms to activate such ports. But this phenomenon still occurs slowly, which is mainly because Brazil is configured as a very bureaucratic country, where such concession contracts require a considerable waiting time.

Regarding the partially active ports, from the interviews, it was possible to verify that in the majority of them, the facilities exist and there are people working in them, but there are practically no operations in them. In these ports, people work more in the sense of keeping the facilities in good condition and carrying out administrative and bureaucratic activities related to public administration. During a visit to the Pirapora Port, a public port under federal administration in the region of the Sao Francisco Waterway, it was possible to visit the port facilities and it was possible to verify that the port, despite being listed as an asset, is a partially active port. In fact, the port could be considered inactive, as no products circulate through it, being active only because there are public servants acting in administrative functions at the port.

After visiting the facilities of the Pirapora Port, it was possible to carry out a face-to-face interview with the port manager. This interview was probably one of the main interviews of this research, as the manager had extensive experience (thirty-four years) with IWT. The manager explained in the interview what IWT looked like decades ago, what happened over the years and the current situation of IWT in Brazil. The manager of the Pirapora Port (I7) indicated a friend (I8), who owns boats and works with IWT, who was one of the interviewees of the private sector in the survey. In addition to the Pirapora Port manager, two other public port managers were interviewed (I2 and I4), totaling three managers who contributed to the research with specific information about public ports (I2, I 4 and I7). Table 1 below details the profile of the interviewees in more detail.

Table 1.

Interviewees profile and source.

Regarding the ports of the private sector, in some cases, the ports were granted by the government to private entities, and in other cases, the companies themselves built the ports on the banks of the rivers but with the authorization of Brazilian government. Regarding private shipping companies, using the data on the ANTAQ webpage, the researcher looked for managers of these companies to carry out the interviews. But unfortunately, access to managers of private ports and managers of shipping companies was very difficult, so regrettably, it was possible to carry out only two interviews (I6 and I8) with managers from the private sector who work with IWT. But interviewees I1 and I3 have private micro-enterprises related to IWT, in addition to many years of experience with IWT activities. And as they also act as representatives of public administration, the interviews with them (I1 and I3) were important for the research mainly because it was possible to analyze both relevant issues from the perspective of public and private entities and big and small firms in the research, which meant that the sample could be analyzed from different perspectives.

It is important to inform that it is common for people to avoid responding to surveys, especially interviews, because the execution time of the interviews is longer and therefore it is difficult for people to agree to do them. It is also important to add that many private companies prohibit managers from giving interviews, in which instances the researcher was directed to the companies’ communication department, which informed that such interviews would not be possible to be carried out.

4.2. Interview Questions

The results of the first part of the interviews are presented below.

4.2.1. Part 1—Profile of Interviewees

Table 1 presents the interviewees’ profile.

From Table 1, it is possible to verify that three respondents are from public ports of Brazil (I2, I4 and I7), also participate three micro and medium enterprises (I1, I3 and I8), with I3 also working in the city hall administration in the area of works and transport. In addition, we also interviewed a planning secretary of Presidente Epitácio city (I5), a transport manager for a large company (I6), a Brazilian Navy Lieutenant (I9), a retired steamboat captain who is responsible for the museum of steamboats in the municipality of Pirapora on the Sao Francisco Waterway region, which is one of the most important waterways in Brazil (I10), and a president of a river workers’ union of the Tietê river, another important waterway in Brazil (I11), named Tietê-Paraná Waterway.

From Table 1, it is also possible to verify that I6, I8 and I11 were interviewed after being indicated by I4, I7 and I5, respectively, where the snowfall technique helped to capture three more interviewees to compose the research sample.

It is also important to point out that apart from the lieutenant of the Brazilian Navy (I9 ©) who has 10 years of experience with the IWT activities, which is already a great level of experience, the other interviewees had extensive expertise in relation to the topic. Of the other ten interviewees, five have more than twenty years of experience and the other five have more than thirty years, being possible to highlight I10 with more than thirty-seven years of experience and I1 and I3 with more than forty years. This vast experience of the interviewees enabled a better understanding of the changes that occurred in IWT in Brazil in the last three decades.

Another aspect that enriched the research is the fact that the interviewees work in different types of organizations; in this sense, it was possible to verify perceptions, visions and answers from different perspectives on the research topic.

Following, questions three and four were directed only to respondents who worked in shipping companies that act in IWT. The result was that the company of interviewee I6 had 309 vessels registered at ANTAQ and in operation, and the company of interviewee I8 had 6 vessels, but these were not in operation and not registered with ANTAQ. It is important to inform that interviewee I8 reported that he had around thirty vessels when navigation in the region of the Sao Francisco Waterway was frequent. But with the decline of navigation in the region in the second half of the last century, he started selling his vessels.

4.2.2. Part 2—Perceptions about IWT and Its Challenges and Opportunities in Brazil

Through the interviews, it was possible to verify that the decline of navigation in Brazil was due to several factors, but the main one being the increase in the paving of secondary roads, becoming highways and then being used by trucks. In addition, road transport is an easier way to move goods, as it is faster and guarantees collection and delivery only by trucks, unlike vessels. For example, a truck can pick up goods at an industry and deliver at the industry customer’s address, while vessels can only do this if both companies are on the banks of rivers. So, in the majority of cases, IWT are dependent of other transport modes like railways and highways to connect rivers to cities and other places.

Other main reasons reported in the interviews that caused navigation to be left aside were problems related to public policies, precarious infrastructure of ports and waterways and the lack of integration between transport modes, which are topics that will be discussed in more detail ahead.

The decline in navigation in Brazil occurred mainly in the second half of the last century, when governments intensified the construction and use of highways. At this time, there was a need to interconnect distant regions of a country with a large territorial extension like Brazil so that products and people could be moved more easily and quickly. Another important point is that at that time the industry was expanding significantly with an ever-increasing range of industrialized products being available to the market. In this era, the automobile industry developed a lot too, and as road transport was configured as easier, faster, and cheaper, the highways were very utilized and the waterways were left aside. Moreover, it was also mentioned in interviews the influence of Petrobras, a Brazilian state oil company, that with the increased use of highways would sell more fuel and make the government profit more.

For these and several other reasons, there has been a significant decline of IWT in the second half of the last century in Brazil, and thus the ports, waterways and other facilities became precarious over the last few decades. But mainly at the beginning of the 21st century, there has been a recovery of interest in navigation, mainly because fuel prices have increased a lot in this period, causing transport costs to raise product prices. And considering that the market expects costs to be as low as possible, transport models are being rethought. In this sense, the intermodal transport model has developed a lot, mainly in the European continent, but in Brazil, the changes in this sense are still limited.

In the fifth question of the interview script, considering the recovery of interest in navigation in Brazil, of the eight main interviewees, half of them said they see a recovery of interest in navigation in Brazil. I1 said “yes, because of the need” (i.e., the need to transport commodities at a lower cost). I3 said “Without a doubt, as it is 60% cheaper”. I4 also said yes, mainly in their region of operation, which is the northern region of Brazil, where according to him, the demand for IWT has increased. He even said that “The northern arc is more interesting than the southern and southeastern regions due to transportation costs, and because it has fewer tolls and queues”. And finally, I6 also agreed, saying that “in the last three years, yes”, relying on the increase in agrobusiness production in Brazil, increasing the use of the north corridor for production flow due to its economic viability, corroborating what was said by I4.

Respondents who did not agree with the recovery of interest in IWT in Brazil were I2, I5, I7 and I8. In this sense, I5 replied that “In relation to IWT I do not see a recovery in interest, only maritime transport has increased significantly”, respondents I7 and I8 replied that in their region there is no interest. In this case, the answers vary according to the region where the interviewee operates, as in some regions, IWT have practically ceased their activities and there are no good expectations of return, as previously reported in this research. While in other regions, despite their ills, the activity has been developed, albeit slowly.

The sixth question was about the main challenges of IWT in Brazil, and the interviewees highlighted problems related to lack of public policies for IWT and large bureaucracy, precarious infrastructure of ports and waterways, lack of integration between transport modes and strong action by NGO and entities groups.

The main challenge quoted was in relation to public policies for IWT and bureaucracy. In this sense, it is important to highlight that several river ports are inactive due to the lack of synchronization between the federal, state and municipal spheres. In the interviews with the managers logged in to the municipalities, we were informed that the municipalities desire to take control of the public ports in order to reactivate them. But for this, the federal government must grant the ports to the states, and after that the states make the concession to the municipalities, which is a process that appears to be very bureaucratic and difficult. Another challenge is the environmental licenses for building and improving port and waterway infrastructure in Brazil, whether public or private, which are excessively bureaucratic. This ends up being related to the second most cited challenge, which are the conditions of waterways and ports, which in most cases are not in good condition.

Still in relation to public policies, there are major challenges that IWT faces in Brazil. Regarding public ports, one of the interviewees stated that “the administration of Brazilian public ports has a political character, always with appointments of managers. Therefore, when a new president is appointed, there is a change in the board of directors. And with the change in management many procedures are changed, taking approximately 90 to 120 days resizing, which delays ongoing operations and makes it difficult to find new clients, as it is necessary to wait for new procedures from the new board”. Another interviewee adds that in addition to the constant changes in management: “few of the appointed managers are technicians, the majority are politicians”. It is important to note that this disrupts IWT activities, as managers appointed by politicians usually do not have the same expertise as technical managers, and in many cases, they put political interests ahead of the interests of the activity.

Another point related to public policies is the corruption, where recent operations such as “Zelotes” and “Lavajato” showed criminal relationships between public works and contractors. In this sense, an interviewee raised an important point of view, arguing that “the waterway does not need major works or maintenance. What could be a great opportunity is actually a problem because politicians want to inaugurate works. And it is known that there are companies close to the government making a lot of profit from works”.

In addition, in relation to the large bureaucracy within public ports, one interviewee argued that public ports lose competitiveness. According to him, among the reasons, “There are delays at public ports because everything has to be approved based on the law. To replace a pole for example it is necessary to have 3 quotes, and pay the amount established by the government. Therefore, you pay R$45.00 for a pole that you can buy for R$30.00”. These problems related to public policies and bureaucracy end up causing the second and third biggest challenge cited by the interviewees, which are the precarious infrastructure of ports and waterways and lack of integration between transport modes in Brazil. In this sense, adjustments in public policies are needed to reduce bureaucracy and support the development of IWT in Brazil.

The fourth most cited challenge was the actions of worker’s unions and Non-Government Organizations (NGOs). Regarding the worker’s unions, it is necessary to highlight that the unions of road workers are very strong in Brazil, having a lot of political support, and they do not want to lose transport slices for transport by waterways.

Related to IWT, there are port workers’ unions too, which also have a very strong presence within Brazilian river ports. One of the interviewees contributed a lot to the understanding of labor in public ports in relation to worker’s unions. He said that “I think that the main bottleneck that exists is the value of labor”. While there are worker’s union agreements, “The values used do not match the reality of logistics in the world in terms of shipping. But in Brazil the union is very strong and it is not possible to reach an agreement that is good for the shippers”. He complements, saying that: “A crane operator in a private port in our region earns around 5 thousand reais in Brazilian currency (around 940EUR). In public ports, to comply with law 12,815, [55], the same crane operator earns around 16 to 17 thousand reais (around 3.1EUR)”. In addition, “This crane operator has not completed high school and is being paid the equivalent salary of a doctor, lawyer or engineer, and often acts irresponsibly, without commitment to the work, the client or the load. And he cannot be replaced by someone from the private sector, it has to be within the framework of workers’ unions. This is the situation we live in”. In addition, according to another interviewee, “The cost of public ports in Brazil is five times higher than that of private ports”, therefore, he defends privatization and says that “A public port that was supposed to have 4000 employees actually has 9000, who pays this bill?”.

The inefficiencies of Brazilian public ports, such as those mentioned above, are other reasons why IWT has been left aside. But some interviewees said that there are great efforts by municipalities to have autonomy over public ports and afterwards move to private entities through concessions. In this way, it would be possible for port activities to be reactive, including the possibility of creating logistics centers in these cities. These logistic centers would support the development of the cities, mainly in the economic sphere, where more logistics activities would mean more companies in the city, more products being transported, more business activities in these cities and more fundraising.

In addition to worker’s unions, NGOs were also mentioned, but less frequently, acting when construction on waterways and ports could threaten the environment. NGOs will be addressed in more depth ahead.

To overcome the challenges (seventh question), the main actions proposed by the interviewees were reducing bureaucracy, strengthening public policies to support IWT and improving the infrastructure conditions of waterway ports and transport modes. Among the points that were highlighted with more emphasis by the interviewees, it is possible to mention cooperation approaches between the public and private spheres, with less bureaucracy and facilitation of public–private partnerships, so that transport modes can be used more appropriately. In addition, management, inspection and control should be the responsibility of the public sphere, but the private sector can help in many activities aiming at the improvements in the models.

Regarding how to overcome the challenges, one of the interviewees said that the first thing to do would be to create a specific regulatory body for the IWT sector and then through it develop different policies that can help with the development of the sector. Potential policies include the following: tax incentives for products transported by waterways, for naval construction, in addition to tax exemptions for ports, shipyards and warehouses; incentives for the purchase of fuels, lubricants and other items; creation of credit and financing policies for companies that operate in the IWT; and mandatory transport of items from public companies such as Petrobras, Conab and others by waterways as a way to encourage and strengthen the sector.

Regarding question eight, about the opportunities that the IWT can provide, the most frequent answer was cost reduction, where respondents mentioned that river transport has the lowest cost and that it has a lower risk of accidents because it is known that transport by road is what causes most accidents. In addition, the volume transported by the waterways by means of tugboats is large; thus, transport migration to the waterways could mean a significant reduction in trucks on the highways, reducing accidents. This shift would reduce the cost of maintaining the highways too, in addition to reducing the consumption of energy, mainly fossil fuels, and consequently reducing GHG emissions into the atmosphere as well as reducing congestion in metropolitan areas. A good example is that a barge carrying 2 to 3 thousand tons can remove about 30 trucks from the highways not to mention that the vessel has about three to five crew members depending on the barge and two engines emitting CO2, against 30 drivers and 30 engines for the trucks. Furthermore, it is possible to avoid the theft of loads, an activity that is unfortunately common in Brazil, which means that transport costs per road increase due to the use of armed escorts. In addition, there are cases in which the drivers themselves steal part of the loads they transport.

Another point to be highlighted as an opportunity is the creation of intermodal terminals and transport junctions interconnecting transport modes in strategic locations, which could bring development to regions of the hinterland of Brazil, mainly in the north and northeast regions, which are the least developed.

In the ninth question, when asked to enhance the opportunities, the interviewees mentioned the reduction in bureaucracy, the improvement of the transport infrastructure, government incentives, better logistics planning in Brazil and the reduction in operating costs in public ports. One of the interviewees added that to overcome the challenges, the government is an essential part, “It has to be by the government, ANTT, ANTAQ and everyone, everyone has to sit down, and create a regulatory model for transport mode use, that is the first thing”.

4.2.3. Part 3—Eight Topics Considering the Challenges and Opportunities of IWT in Brazil

This section presents the results of the interview considering the eight main topics that were listed as the main challenges and opportunities of the IWT in Brazil.

- (1)

- Research Availability

The majority of respondents (five) expressed that the availability of surveys is indeed a challenge that needs to be addressed. They suggested that there should be an increase in the number of surveys conducted to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the topic at hand. Three interviewees added that the most striking thing in the reality of Brazil is the fact that surveys, in most cases, are not applied in organizational daily life, that is, most surveys “They just stay on paper (planning)”. A solution to this problem would be greater interaction between research entities and companies. One interviewee said that “regional economic data on agricultural production, industrial production, commercial cargo movement, services and transport systems” are information that need to be available so that transport planning can be carried out. Another respondent said that it is necessary to conduct “research related to planning”. Further stating that: “Our planning is done here randomly”. Another noted that “companies are pioneering developing studies and advancing in the way they can”.

The public universities of Brazil, which have good quality, some being among the best in the world according to university rankings, can help with the development of companies through research and therefore contribute to the IWT development in Brazil. However, such partnerships are again hampered by the existing bureaucracy in the country, thus being a great challenge to be mitigated by the nation. This is mainly because it is difficult to establish partnerships between companies and universities in Brazil, especially if the company intends to pay for research, as bureaucracy makes it difficult for public entities to receive private funds.

Adjustments should be made in this regard, as such partnerships would be very positive for both sides, as creating research departments within companies is very expensive, and therefore many companies end up not investing and not innovating in the way they should and thus end up being less competitive in the market. Whereas in universities, Research and Development (R&D) departments in most cases already exist. Thus, with these partnerships, it would be possible to increase the performance of Brazilian companies in the world market and strengthen the Brazilian economy. In addition, universities could receive more financial resources from private companies, and this additional fund could improve the quality of the education service provided to the Brazilian population.

This reinforces what was mentioned by the interviewees, because only an interviewee of a large private company said their company had an effective R&D department, that is in the engineering and development of equipment to improve navigability conditions. In the companies of the other interviewees, either there are no R&D departments, or, if they exist, they are not disseminated as they should be. This shows the necessity of public–private partnerships for the research and development of IWT in Brazil.

In an important public port, where one of the managers was interviewed, many research studies were carried out. But as operations at the port ground to a halt, research was also paralyzed. The interviewed manager said that there was very in-depth research: “The georeferenced information system that we were implementing was linked to the telemetry network, which was also being implemented, but these projects were discontinued and the equipment was looted. With these integrated studies it would be possible to empirically discover the mobilization mechanism of sandbanks, how these banks move, and thus predict where sandbanks could form to carry out desilting. But the ideal is not to desilt, it is a palliative measure, the ideal is to study a way to fix the sand banks on the banks through hydraulic works, as is done on the Mississippi River in the USA”. It is thought that many other cases like this one also occurred, which means a loss of information over time and negatively impacts IWT in Brazil.

Regarding participation in congresses, conferences and events, five interviewees said that they participate frequently; one of them (I10), said: “Yes, it takes encouragement and nurturing dreams”. The interviewee from the large company said that the company is always invited to attend events and that top management is always participating in events in Brazil and in other countries. It was noticed in the interviews that due to the decrease in navigation in some regions, there was a decrease in events and discussions on the subject, reflecting the lack of motivation of some managers in relation to IWT activity and related topics, such as conferences and events. One of them said that “No longer, I gave many lectures at events and colleges”.

This research seeks to help in this sense: to bring information that can help in the development of IWT in Brazil.

- (2)

- Integration between transport modes (road, rail, river and air)

Five interviewees considered that the integration between transport modes is a great challenge to be faced. It is very important to start the results and discussion in this section with a very pertinent comment of an interviewee in relation to the subject addressed in this research, which is the IWT. His speech was very assertive, saying that: “The waterway does not work without the other modes, if it is not designed with the other modes, it will remain there without being useful”. Thus, the transport modes must be interconnected so that there really is an efficient transport system using the four main transport modes.

It is also important to point out that in many cases, this integration does occur, as in the south and southeast, which is the most developed region in Brazil, and also in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, as mentioned by one of the interviewees. But as many of the river ports are not in operation in Brazil, intermodal transport ends up being used very infrequently. This is the case of the Pirapora Port, an important public port without operation in the state of Minas Gerais, where the Sao Francisco Waterway passes. This waterway is 2354 km long, connecting the southeast region to the northeast region of Brazil. In Pirapora, there is also a railroad to the sea port of Vitória, even passing through Belo Horizonte, the capital of the state of Minas Gerais. But there are no operations in the Pirapora public port, and the railway transports only a small amount of products compared to its capacity, being used almost exclusively the road. In this example, it can be perceived that if the transport modes were connected and working, it would be possible to reach significant advances in the Brazilian transport system, with cost reduction and sustainability, making the Brazilian logistics greener and more competitive.

Still regarding the Pirapora public port, an interviewee added that there is demand for IWT in the region of Sao Francisco Waterway, “There are 1.5 million tons of gypsum and 1.6 million grains in the São Francisco waterway region, totaling 3.1 million tons that would make the waterway completely viable, and this is not being seen”. But it is known that many other products can be transported by waterway, and as it is integrated with the railroad and highway, the city could become an important logistics center. In this sense, the installation of an intermodal terminal could contribute to a considerable reduction in logistics costs and support the development of the city.

The Pirapora public port is just an example, there are many other river ports in Brazil without operation, most of them with good potential for intermodal terminals installation.

Another interviewee brought a very important argument, which is actually what is expected from a developed transport system. He said: “It is necessary to resume interconnection between modes of transport in Brazil, mainly the railway line, so that river navigation provides the initial transport and the railway lines cross branches, with trucks contributing to arterial connections, no longer making long journeys”. But unfortunately, this type of multimodal transport in Brazil is still underused, because the transport continues to be moved mostly by road in long journeys, which needs to be changed.

But there is another problem in Brazil related to the integration of transport modes. As the country has a large territorial extension, in the most developed regions, there are many highways, but in the less developed regions, in the interior or hinterland of the country, there are few highways, and those that exist are not in good condition. There are other regions even more lacking in highways, such as the northern region of Brazil for example, where rivers are normally heavily used. In this region, near the Amazon Forest, in some cases, the river is the only way to move products and people. Corroborating this thought, one interviewee that works near the Amazon region said: “there are no highways here, the river is everything to us”. This reinforces the need for a greater integration of transport modes in Brazil and for greater balance in their use.

In many moments of the interviews, the lack of railways was mentioned. One of the interviewees said that “There should be more railroads, but the construction does not get off the ground”. Another interviewee said: “It is not recommended to create demand and transport almost exclusively by road, mainly because the cost is lower by rail and waterways”.

As for whether this integration between modes is improving, most respondents said no. Those who answered that integration is improving made the statement in the sense of “It is improving due to necessity”, but the improvement is still timid. In relation to the creation of intermodal terminals and logistics centers along the waterways, all interviewees evaluated it positively, “This is the solution” said one of the interviewees, “It is the future, it is what will happen”, said another. But due to the challenges of creating these logistics complexes, all interviewees were not very optimistic, which was mainly due to bureaucratic issues and lack of public policies for IWT, which in Brazil are major obstacles, as mentioned earlier.

Another point that was considered for interviewees is the strength of the union of road workers, who do not want to lose slices in relation to transport for other modes.

- (3)

- Public policies for IWT (Investment and support)

Based on the paragraph above, and in the research data, the lack of public policies to support the development of the IWT was the greatest challenge. As previously mentioned, Petrobras plays an important role in public policies in the country, as it is a state-owned company with high revenues. And considering that Petrobras commercializes energy, especially fuel in the country, public policies to strengthen the IWT could certainly negatively impact the sale of fuels in Brazil and consequently government tax collection. So, perhaps it is normal not to encourage transport by other modes, as the road mode is the one that consumes more fuel. Corroborating this assertion, one of the interviewees stated: “the government is prioritizing fuel consumption, and the highway system consumes much more than the railroad, waterway and airway”. But it is necessary to point out that the market always ends up adjusting, because if transport by road reduces, or grows more slowly, transport by waterways and railroads can boost the economy in other ways, such as boosting the shipbuilding industry, the business of cranes, forklifts, conveyors, and several other items. In addition, many people working in fluvial and rail companies would be needed with increased activity. So, you lose on one side, but gain on the other. As happened and still happens with industrial mechanization, where machines have been replacing people over the years in industry, but much more people are needed to build, control and maintain industrial machines, people end up adapting their activity, working on more important and technical tasks, which ends up developing the workforce. Thus, such logistics developments in Brazil with greater balance between the transport modes could, for example, encourage Petrobras to invest in greener energies as an alternative to fossil fuels, which would make the company update and maybe profit even more. In this sense, public policies are needed to encourage IWT, because if this does not happen quickly, Brazilian products may lose more competitiveness in the international market.

When asked if there are enough investments for the maintenance and improvement of waterways and ports in a satisfactory manner, six interviewees said no, one said reasonably and another said yes, which proves that public policies are needed in this regard. Regarding public–private partnerships, the majority said that it is a good alternative, and that they should be strengthened with more public policies in this regard mainly to make IWT activities more agile. This topic has already been discussed citing partnerships between companies and universities, but there are many other possibilities for public–private partnerships that could develop the Brazilian logistics and transport system.

Regarding the support and supervision of public entities in Brazil, such as ANTAQ, the Brazilian Ministry of Ports and Airports, DNIT (National Department of Transport Infrastructure), IBAMA (Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), MAPA (Ministry of agriculture, livestock and supply) and others, there was a consensus among the interviewees that the support offered could be better. One of the interviewees said: “We are constantly under supervision from these entities. The support leaves a lot to be desired, it seems that they are more focused on fines and inspection than on operations”. In addition, many interviewees were very dissatisfied with the performance of public entities in relation to other aspects, such as inspection procedures, that are usually lengthy, delaying navigation. Thus, although the public service has improved in recent years, it is still not enough.

Finally, it is possible to verify that a significant effort is needed in the creation of public policies for the development of IWT in Brazil.

- (4)

- Waterway infrastructure (ports, waterways, locks) and water conditions

Asked if the condition of waterway infrastructure in Brazil is a challenge for the development of IWT, only one of the interviewees said no, that he sees that in his region, it is not a problem. The other seven interviewees consider that the conditions are not good and constitute challenges to be overcome. One of the interviewees even said, “We don’t have waterways, we have rivers where companies navigate in a practically exploitative way, with no use of beacons or signage to condition navigation”, he completes saying that if it were not for the expertise of the crew, there would be no navigation. This type of argument was relatively common during the interviews, because it is not enough having the river. A river requires maintenance to be considered a waterway, mainly dredging and buoying, among others. In this sense, an interviewee brought important information about important rivers in the northern region of Brazil, saying that: “The Amazon, Tapajós and Madeira rivers, they are not waterways, they are navigable rivers by their nature, and not because they are conditioned to navigation”. Thus, as these rivers have very large volumes of water, even without specific care for waterways such as dredging, buoying and other activities, navigation in them ends up happening. But such care is necessary especially in rivers that have lower water levels, as there may be points with boulders, sandbanks or other obstacles that can make navigation difficult or impossible. This care is also necessary in rivers such as Amazon, Tapajós and Madeira, because even with large volumes of water, there may be points where navigation is more difficult, with boulders and sandbanks.

Regarding the infrastructure conditions of inland ports in Brazil, half of the interviewees said that the conditions are not good. “Everything must be redone”, said one; “scrapped”, said another. And only two interviewees said that the conditions are good or reasonable, considering public ports. Regarding private ports, there is a consensus that conditions are good. One interviewee compared public ports with private ports: “Public ports have problems, but private ports are getting stronger. Private ports don’t have many problems, but we do (in public ports) because of slowness and bureaucracy”. From this report, it is possible to verify again the bureaucracy disturbing the IWT.

Regarding the conditions along the waterways, the majority said that there is no waterway; there is a navigable river. And that in most waterways, the conditions are not good. Only interviewee I11, who works on the Tietê-Paraná waterway, said that the conditions on the waterway are good, as there are several dredging companies along the waterway. But he said that such conditions can be improved, mainly because the buoying service is not good. It should be noted that the Tietê-Paraná waterway is the one with the most navigation in Brazil, and it is located in the southeast region of the country, which is the most developed in Brazil.

Regarding the locks, their existence is necessary to allow navigation where there are hydroelectric plants, since they are the ones that provide the crossing of the boats. In regions where there are locks, there are some problems related to delays in transporting ships, as it is the hydroelectric plants that control boat traffic. In this sense, one of the interviewees said: “The lock cannot be managed by the power generator, it must be independent, so that it is possible to stimulate river navigation traffic”. In this sense, there must be changes so that both activities, energy generation and navigation, occur in the best possible way without one activity disturbing the other.

Regarding water levels, it was reported that with the construction and expansion of hydroelectric plants in Brazil, water levels in rivers decreased mainly due to the impoundment of water in the dams, which were becoming bigger and bigger. In this sense, it was mentioned by one of the interviewees that the water should be used in a more shared way so that navigation is not impaired. Because with low water levels in the rivers, drafts decrease and vessels are more likely to run aground on sandbanks.

In addition to the reduction in water levels due to hydroelectric plants, there are also periods of drought when the volume of rivers decreases. But even so, it is possible to navigate in most rivers in Brazil but with more care and with less draft. On the Madeira waterway, that flows to Amazon Waterway, in the dry season, low water levels are also a problem mainly because of boulders that make navigation difficult. Thus, in the dry period, the navigation occurs only during the day. But if there were signs on the waterway, navigation could take place uninterrupted.

It is also important to highlight climate changes, such as in the region of the Sao Francisco Waterway, where the water levels dropped considerably in recent years, as can be seen by an interviewee that said: “we are in the worst drought in the history of the Sao Francisco River from 2014 to now. It never rained so little”.

Thus, for infrastructure to improve, it is necessary to have more public policies for IWT to help with the maintenance and adaptation of waterways so that they can play their role in the development of IWT in Brazil.

- (5)

- Availability of labor

It was expected that the availability of labor would be a problem for the IWT, as it was listed as a challenge in some papers in the literature review. But the researcher was surprised while the interviews were taking place, because this availability of labor was not considered a great challenge for IWT in Brazil by the interviewees. This occurred because normally in the riverside cities, there are the River Captaincies of the Brazilian Navy and teaching institutions that offer qualification courses so that people can work in IWT operations, making the workforce available. There were courses of commanders, foreman, sailor, cook fluvial, and others.

But it is necessary to inform that the reduction in navigation in Brazil in the last years caused many of these courses to be extinct, so the existing workforce ends up migrating to other activities and other regions. And with the paralyzed IWT activities, knowledge ends up being lost, as one of the interviewees said: “Knowledge is dying, and if there is no one who can stimulate the growth of river navigation it will be difficult to regain this knowledge”. The same interviewee also added that: “the captaincy of the Brazilian Navy does everything to have (the courses for captains, sailors and others), but as there are no more (IWT activity), it does not justify having courses”. The interviewee points out that: “If you need to set up a convoy today, maybe you won’t be able to”.

As shown above, despite much knowledge being lost over the years, the availability of labor for IWT activities is still not a big problem, but if there is no resumption of IWT soon, the situation could become worse.

- (6)

- Speed of IWT

Respondents do not believe that speed of IWT is a challenge for the development of IWT in Brazil. In this sense, one of the respondents said that IWT is slower by its nature. One important point is that because more time is spent being transported, it is possible to reduce product storage time and reduce costs. One of the interviewees said: “IWT has lower storage costs as the goods stay on the vessels longer”. Thus, with transport planning, the product can be in stock during transit rather than in warehouses, reducing costs.

One of the interviewees said that the bottlenecks are “On the waterway, as there are places that cannot be crossed, especially at night when navigation is more complicated, making it necessary to stop, stay overnight, and then cross during the day with caution, even with signs available”. This corroborates with the analyses made in the waterway infrastructure section, because the rivers, to be considered as waterways, need care such as beaconing, dredging, signaling and other care.

Another point that stood out was delays in port inspection activities, which were listed by three managers as the biggest bottlenecks. When the question was asked, one of them suddenly said: “Inspection, did you know that sometimes a barge or vessel stays with a sailor for ten to fifteen days to wait for the release of the revenue for the cargo to continue navigation?”. And he added, “The guys take a while to release. What is the cost of this? Its money thrown in the trash.” Another interviewee said that, “There are days when the IRS does not work, and you have to schedule an appointment. Working with exports and having to wait for inspection is something that cannot happen”. The same problem happens with MAPA and IBAMA; the same interviewee added that these inspection entities should work more together with other actors to assist in the development of the IWT activity. Thus, it is evident that the performance of the public service has a significant impact on IWT. Therefore, there is a pressing need for substantial improvement in the quality of public services, particularly in terms of efficiency and agility.

One of the interviewees, a manager of a private port located in the northern region, said that his biggest problem is the delay of trucks on the highways, which means that the boats have to wait to be loaded and then continue their journey. He said that: “BR 163 delays transport as it is not paved and during the rainy season trucks have difficulty passing in some places”. As previously mentioned, in the north of Brazil there are few highways, and those that exist are in poor condition, and many are not paved.

Thus, is necessary to improve all the infrastructure of waterways, ports, locks and other, as well as road and rail infrastructure to create an efficient intermodal transport system in Brazil. This is the only way to reduce transport time: with an integrated and efficient transport system. When asked about how it would be possible to reduce transport time, one of the interviewees said: “improvement in the infrastructure conditions of ports and waterways and greater agility in port activities”, which are really the main points that must be adjusted.

- (7)

- Transport costs

Nine respondents judged that the greatest opportunity that IWT offers is cost reduction, as it is the lowest cost mode. From the interviews, it was possible to verify that the cost of transport by waterways is normally measured per ton and per kilometer, but there are cases in which the price is fixed according to the route and type of cargo. In this sense, it is common for there to be price variations according to the composition of the cargo and the compartment used, whether they are containers, liquid cargo, bulk cargo or general cargo. One of the interviewees informally said that from Porto Velho to Manaus, a stretch of about 890 kilometers, the price was R$80 to R$100 per ton of general cargo, in Brazilian currency (Real). It is important to inform that one Euro is worth approximately 5.4 Reais, which makes these numbers EUR 14.80 and EUR 18.5, respectively.

In relation to the justification for IWT being the least used despite having a lower cost, the answers appointed by interviewees were the same as mentioned earlier in this research, such as lack of public policies for IWT, precarious infrastructure and culture of using road transport. But as logistics development is needed in Brazil, mainly to reduce costs, changes in this regard are expected in the coming years.

Corroborating this statement, with this need for changes and development of the transport model in Brazil, one of the interviewees said that “it is a cultural issue in Brazil, people have always worked with trucks, until they began to see that railroad and waterway were transport modes with best result”. In this sense, it is already known where the bottlenecks are and where efforts should be made, but it is necessary that there are initiatives for the Brazilian transport model to really develop. And for this to happen, public policies that encourage the development of IWT are necessary, which has already been mentioned and discussed in the public policy for IWT section of this paper. Because from the interviews, it was possible to perceive that there is already some pressure from private companies for advances in relation to public policies to assist the IWT in Brazil.

- (8)

- Sustainability (environmental legislation, NGO and entities, renewable energies)

When asked if they believed that IWT could bring benefits in terms of sustainability, with the exception of I11, who was not clear in his arguments, all respondents considered the statement valid. One of them added that IWT “is the one that consumes the least fuel per ton transported”, the others justified it by saying that it is the most appropriate mode, which saves fuel. In addition, the use of waterways contributes to the reduction in trucks on the highways with a consequent decrease in the number of accidents, expenses with road maintenance and less GHG emissions.

Regarding the Ministry of the Environment, Greenpeace, and environmentalist groups, it was asked whether these entities are considered obstacles to the development of IWT in Brazil. Half of the managers interviewed said yes, mainly the Ministry of the Environment, which as mentioned earlier, should reduce the focus only on inspections and punishments (fines) and should also act toward awareness and support, helping in the development of the activity in the country in addition to streamlining the release of licenses for improving waterway infrastructure.