App-Based Digital Health Equity Determinants According to Ecological Models: Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objectives

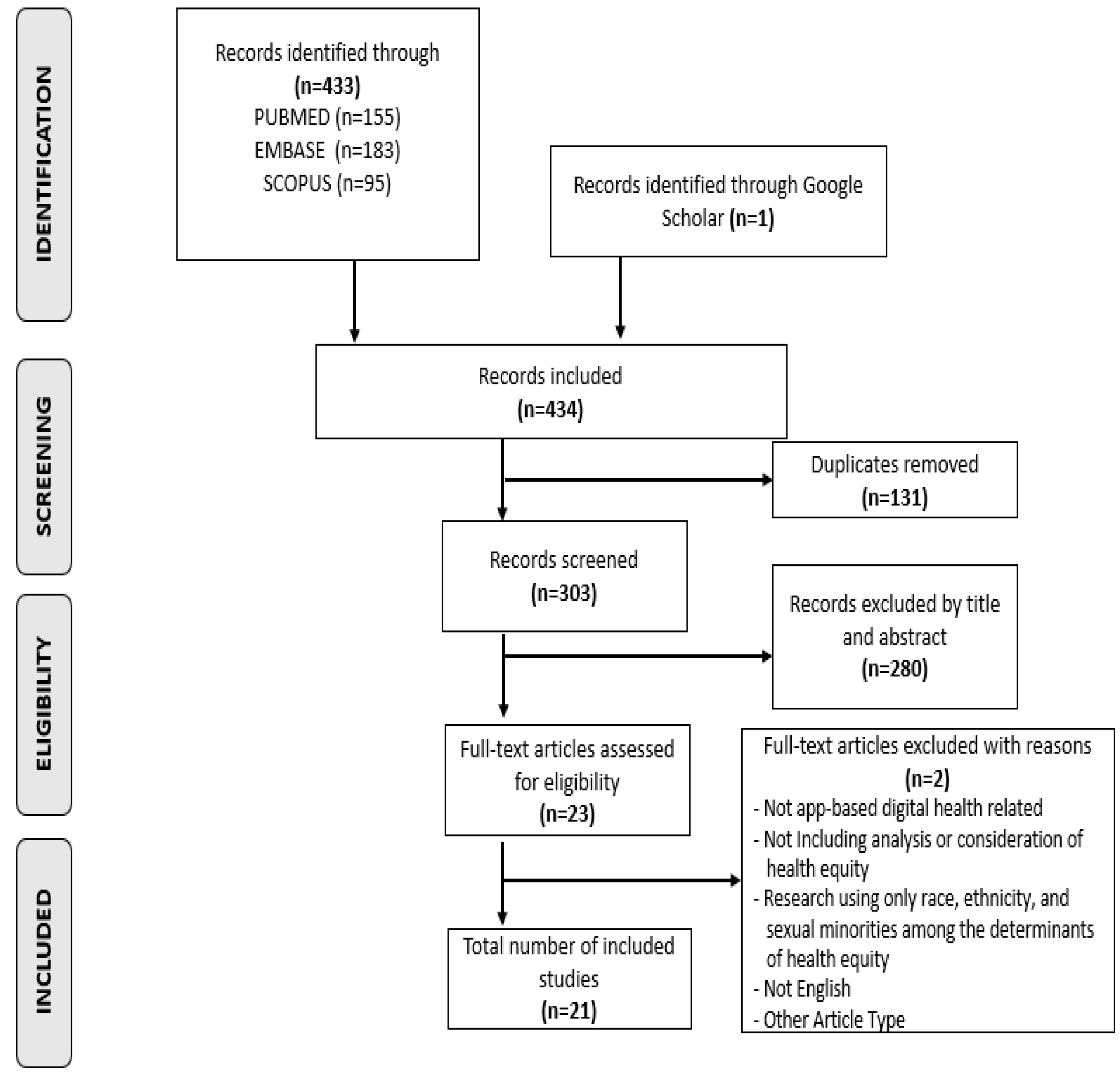

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

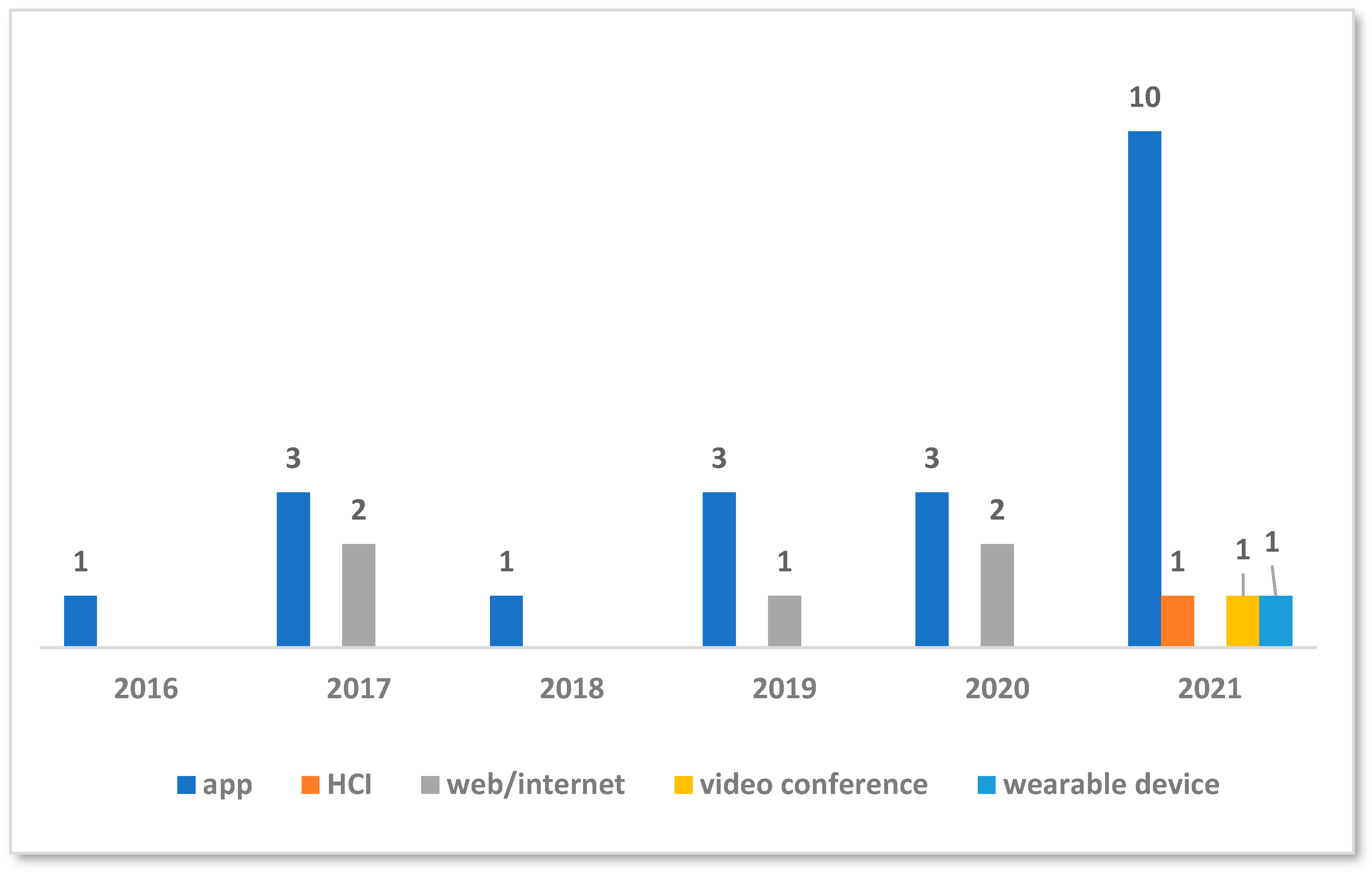

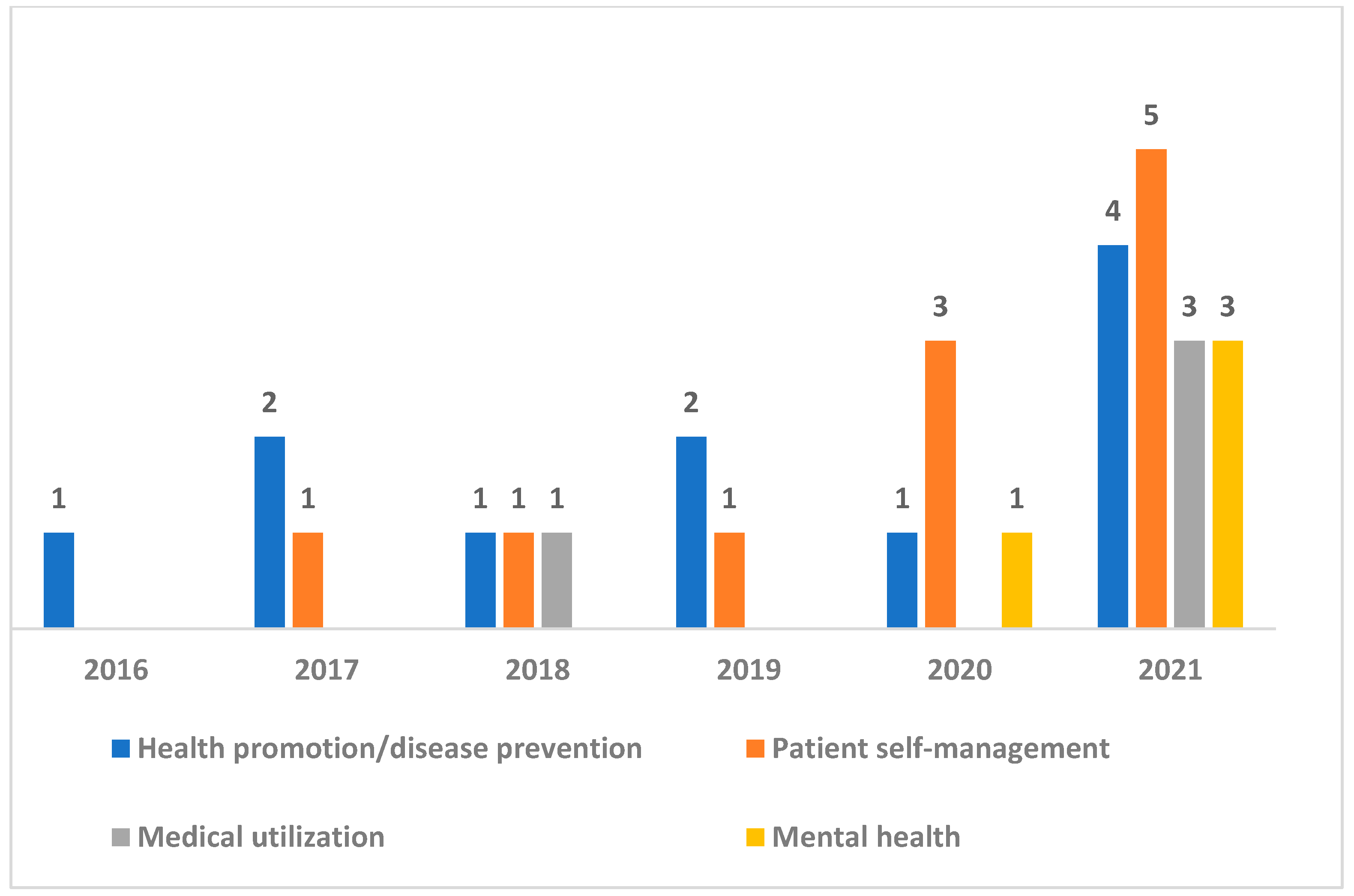

3.1. Overview of Studies

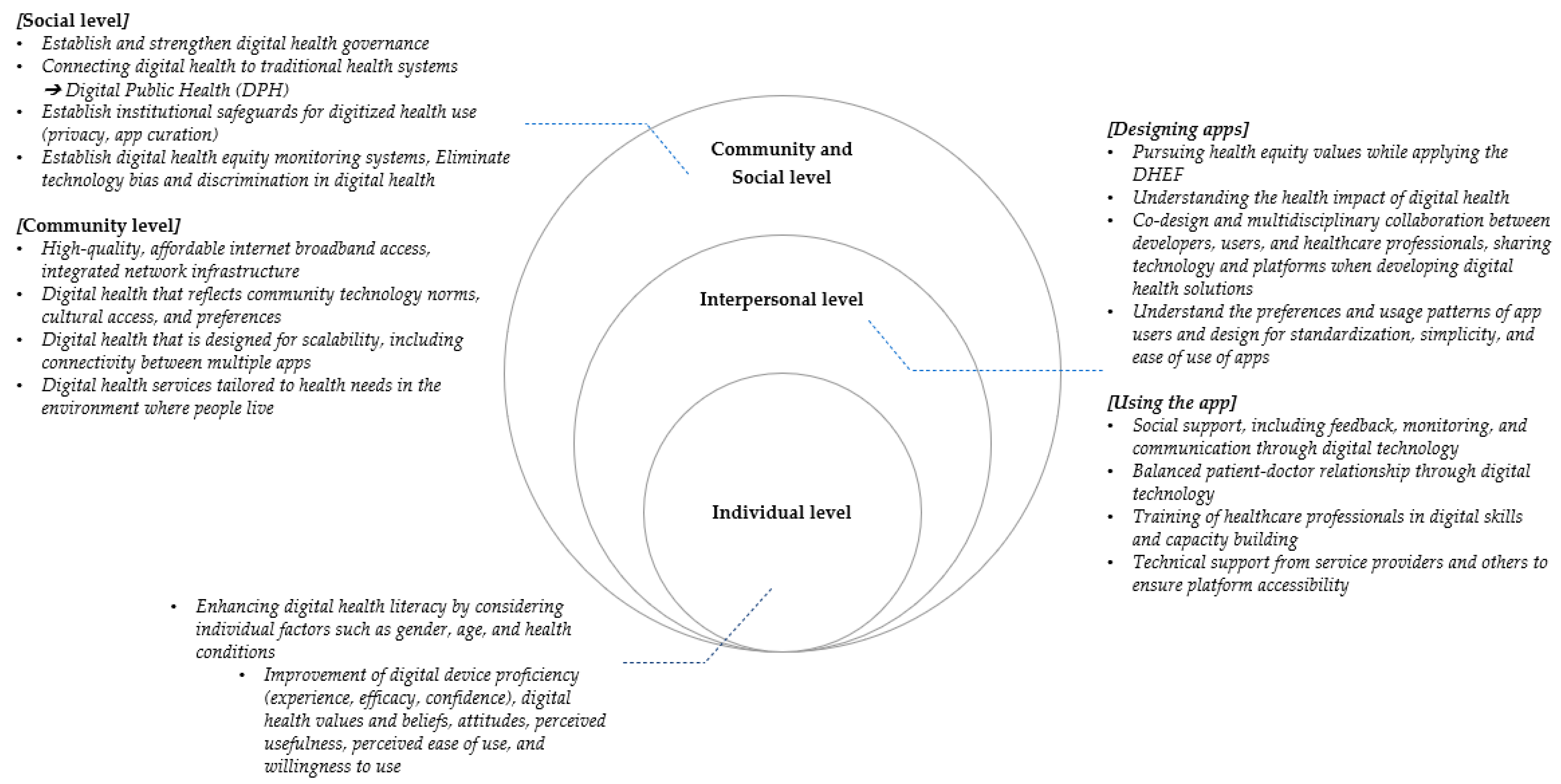

3.2. Digital Determinants of Health According to Ecological Models

| Author | Year | Country | Service | Tool | Methodology | Sample (Sample Size) * | Digital Determinants of Health | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Level | Interpersonal Level | Community and Societal Level | |||||||

| Aromatario et al. [34] | 2019 | France | Health promotion and disease prevention | App | Qualitative research | Consumers, patients, health professionals, app developers, etc. (N = 32) | Literacy | Communication between stakeholders | Internet accessibility and culture |

| Balcombe et al. [26] | 2021 | Australia | Mental health care and healthcare utilization | App and HCI | Literature review | N/A | Disease | Communication, technology sharing, and co-design | Internet accessibility, integrated network, and expanded connectivity between apps |

| Bhuiyan et al. [36] | 2021 | USA | Health promotion, disease prevention, and mental health care | App | Quantitative research | Meditation app subscribers 18 years and older (N = 8392) | Income | Residence | |

| Businelle et al. [18] | 2016 | USA | Health promotion and disease prevention | App | Quantitative research | Hospital smoking cessation clinic users (N = 59) | Income and race | ||

| Camacho-Rivera et al. [23] | 2020 | USA | Patient self-care | App and web | Quantitative research | Adults with chronic disease (N = 10,760) | Socioeconomic status and social security | Residence | |

| Cheng et al. [24] | 2020 | Australia | Health promotion and disease prevention, patient self-care, and mental health care | App and web | Mixed research | Patients ( N = 530) and telephone interview (N = 5) | Literacy and socioeconomic status | Communication between stakeholders | Integrated network |

| Grundy [16] | 2022* | Canada | Health promotion and disease prevention | App | Literature review | N/A | Disease, literacy, socioeconomic status, and subjective perception | Technology sharing and co-design and universal design | Internet accessibility |

| Hannemann et al. [27] | 2021 | Germany | Healthcare utilization, mental health | App and video conference | Quantitative research | Patients who made reservations for treatment during the COVID-19 period (N = 1570) | Disease, literacy, and socioeconomic status | Communication and service standardization | |

| Hernandez-Ramos et al. [28] | 2021 | USA | patient self-care, and mental health care | App | Quantitative research | Pre- and post-coronavirus treatment patients (N = 43) | Literacy and socioeconomic status | Technical support to secure platform accessibility | |

| Laing et al. [19] | 2018 | USA | Health promotion and disease prevention, patient self- care, and healthcare utilization | App | Quantitative research | Health center low-income patients over 18 years of age (N = 164) | Socioeconomic status | ||

| Leziak et al. [29] | 2021 | USA | Patient self-care | App | Qualitative research | Pregnant women, low-income people, and people with diabetes (N = 45) | Disease and income | Customized feedback | |

| Luo and White Means [33] | 2021 | USA | Patient self-care | App | Qualitative research | Individuals who are aged 18 and above and diagnosed with diabetes who own smartphones (N = 15) | Disease and income | Customized feedback | |

| Medairos et al. [20] | 2017 | USA | Health promotion and disease prevention | App, web, and SNS | Quantitative research | Low-income community (N = 291) | Income | ||

| Miller Jr et al. [21] | 2017 | USA | Patient self-care | App | Quantitative research | Individuals who are aged 50–74 who are scheduled for colorectal cancer screening (N = 450) | Literacy and socioeconomic status | ||

| Neves et al. [30] | 2021 | Portugal | Health promotion, disease prevention, and patient self-care | App | Quantitative research | Individuals who are aged 13 and older diagnosed with asthma (N = 526) | Disease, literacy, and socioeconomic status | ||

| Potdar et al. [25] | 2020 | USA | Patient self-care | App | Quantitative research | Individuals who are aged 18 and above diagnosed with cancer (N = 141) | Socioeconomic status, health knowledge, and disease | ||

| Quintiliani et al. [35] | 2019 | USA | Patient self-care | App | Qualitative research | Breast cancer survivors (N = 13) | Customized feedback and monitoring | ||

| Qureshi et al. [37] | 2019 | USA | Health promotion and disease prevention | App and web | Quantitative research | Countries (N = 154) | Education and life expectancy | ||

| Schmaderer et al. [31] | 2021 | USA | Patient self-care | App | Qualitative research | Patients participating in mobile health interventions (N = 10) | Disease and social security | Communication | |

| Ye and Ma [32] | 2021 | USA | Health promotion and disease prevention | App and wearable | Quantitative research | General adults (N = 11,411) | Socioeconomic status | ||

| Hong et al. [22] | 2017 | China | Health promotion and disease prevention | App and web | Quantitative research | Individuals who are aged 45 and above (N = 18,215) | Socioeconomic status, smartphone ownership, and disease | Residential area | |

3.3. Strategies for Mitigating Inequities in App-Based Digital Health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.; Kan, L. Digital technology and the future of health systems. Health Syst. Reform 2019, 5, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun-mi, P.; Min-wook, K. Basic Research on Digital Capabilities of Seoul Citizens; Seoul Digital Foundation: Seoul, Korea, 2022; Available online: https://sdf.seoul.kr/research-report/1734?curPage=2 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Crawford, A.; Serhal, E. Digital health equity and COVID-19: The innovation curve cannot reinforce the social gradient of health. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dover, D.C.; Belon, A.P. The health equity measurement framework: A comprehensive model to measure social inequities in health. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaihlanen, A.-M.; Virtanen, L.; Buchert, U.; Safarov, N.; Valkonen, P.; Hietapakka, L.; Hörhammer, I.; Kujala, S.; Kouvonen, A.; Heponiemi, T. Towards digital health equity-a qualitative study of the challenges experienced by vulnerable groups in using digital health services in the COVID-19 era. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, K. Digital Health Equity. In Digital Health; Linwood, S.L., Ed.; Exon Publications: Brisbane City, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, S.; Lawrence, K.; Schoenthaler, A.M.; Mann, D. A framework for digital health equity. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahnel, T.; Dassow, H.-H.; Gerhardus, A.; Schüz, B. The digital rainbow: Digital determinants of health inequities. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221129093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequities in Health: Levelling Up Part 2; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ulfert-Blank, A.-S.; Schmidt, I. Assessing digital self-efficacy: Review and scale development. Comput. Educ. 2022, 191, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping reviews. Joanna Briggs Inst. Rev. Man. 2017, 2015, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economy Forum. The Fourth Industrial Revolution: What it Means, How to Respond. 14 January 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/ (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Grundy, Q. A review of the quality and impact of mobile health apps. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Businelle, M.S.; Ma, P.; Kendzor, D.E.; Frank, S.G.; Vidrine, D.J.; Wetter, D.W. An ecological momentary intervention for smoking cessation: Evaluation of feasibility and effectiveness. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, S.S.; Alsayid, M.; Ocampo, C.; Baugh, S. Mobile Health Technology Knowledge and Practices Among Patients of Safety-Net Health Systems in Washington State and Washington, DC. J. Patient Centered Res. Rev. 2018, 5, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medairos, R.; Kang, V.; Aboubakare, C.; Kramer, M.; Dugan, S.A. Physical activity in an underserved population: Identifying technology preferences. J. Phys. Act. Health 2017, 14, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller Jr, D.P.; Weaver, K.E.; Case, L.D.; Babcock, D.; Lawler, D.; Denizard-Thompson, N.; Pignone, M.P.; Spangler, J.G. Usability of a novel mobile health iPad app by vulnerable populations. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.A.; Zhou, Z.; Fang, Y.; Shi, L. The digital divide and health disparities in China: Evidence from a national survey and policy implications. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Rivera, M.; Islam, J.Y.; Rivera, A.; Vidot, D.C. Attitudes toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools among adults with chronic health conditions: Secondary data analysis of the COVID-19 impact survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e24693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. Co-designing eHealth and equity solutions: Application of the Ophelia (Optimizing Health Literacy and Access) process. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 604401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potdar, R.; Thomas, A.; DiMeglio, M.; Mohiuddin, K.; Djibo, D.A.; Laudanski, K.; Dourado, C.M.; Leighton, J.C.; Ford, J.G. Access to internet, smartphone usage, and acceptability of mobile health technology among cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5455–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balcombe, L.; De Leo, D. Digital mental health challenges and the horizon ahead for solutions. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e26811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannemann, N.; Götz, N.-A.; Schmidt, L.; Hübner, U.; Babitsch, B. Patient connectivity with healthcare professionals and health insurer using digital health technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A German cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ramos, R.; Aguilera, A.; Garcia, F.; Miramontes-Gomez, J.; Pathak, L.E.; Figueroa, C.A.; Lyles, C.R. Conducting internet-based visits for onboarding populations with limited digital literacy to an mhealth intervention: Development of a patient-centered approach. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e25299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leziak, K.; Birch, E.; Jackson, J.; Strohbach, A.; Niznik, C.; Yee, L.M. Identifying mobile health technology experiences and preferences of low-income pregnant women with diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2021, 15, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, A.L.; Jácome, C.; Taveira-Gomes, T.; Pereira, A.M.; Almeida, R.; Amaral, R.; Alves-Correia, M.; Mendes, S.; Chaves-Loureiro, C.; Valério, M. Determinants of the use of health and fitness mobile apps by patients with asthma: Secondary analysis of observational studies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmaderer, M.; Miller, J.N.; Mollard, E. Experiences of using a self-management mobile app among individuals with heart failure: Qualitative study. JMIR Nurs. 2021, 4, e28139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Ma, Q. The effects and patterns among mobile health, social determinants, and physical activity: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. AMIA Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2021, 2021, 653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; White-Means, S. Evaluating the potential use of smartphone apps for diabetes self-management in an underserved population: A qualitative approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromatario, O.; Van Hoye, A.; Vuillemin, A.; Foucaut, A.-M.; Pommier, J.; Cambon, L. Using theory of change to develop an intervention theory for designing and evaluating behavior change SDApps for healthy eating and physical exercise: The OCAPREV theory. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintiliani, L.M.; Foster, M.; Oshry, L.J. Preferences of mHealth app features for weight management among breast cancer survivors from underserved populations. Psycho-Oncol. 2019, 28, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, N.; Puzia, M.; Stecher, C.; Huberty, J. Associations between rural or urban status, health outcomes and behaviors, and COVID-19 perceptions among meditation app users: Longitudinal survey study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e26037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S.; Xiong, J.; Deitenbeck, B. The Effect of Mobile Health and Social Inequalities on Human Development and Health Outcomes: mHealth for Health Equity. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Grand Wailea, HI, USA, 8–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Park, N.; Yoon, N.; Park, N.; Kim, Y.; Kwak, M.; Jang, S. Understanding the digital health care experience based on eHealth literacy: Focusing on the Seoul citizens. Korean J. Health Educ. Promot. 2022, 39, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.L.H.; Maaß, L.; Vodden, A.; van Kessel, R.; Sorbello, S.; Buttigieg, S.; Odone, A. The dawn of digital public health in Europe: Implications for public health policy and practice. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2022, 14, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Level | Strategies | Detailed Strategies | List of References Examined in the Scoping Review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual level | Digital health literacy education | Enhancing digital health literacy by considering individual factors such as gender, age, and health conditions | [16,19,20,24,30] |

| Improvement of digital device proficiency (experience, efficacy, and confidence) | [19] | ||

| Promoting attitude changes toward app usage | [23] | ||

| Interpersonal level | Values pursuit for health in app design | Understanding health equity | [16,34] |

| Understanding the health impact of apps | [16] | ||

| Application of a DHEF | [16,34] | ||

| Consideration of excluding technological bias | [19] | ||

| Communication, collaboration, and sharing in app design | Co-design | [16,24,26] | |

| Interdisciplinary collaboration | [27] | ||

| Mutual information provision and sharing | [16] | ||

| Communication and encouragement between patients and healthcare service providers | [19] | ||

| User consideration in app design and requirements in app usage | Understanding app users’ preferences and usage patterns | [20] | |

| Specialized content based on participant characteristics | [19,23,24,29,33] | ||

| App design configuration | Standardization | [16] | |

| Simplicity | [33,35] | ||

| Ease of use | [32,35] | ||

| Requirements in app usage | Digital technology proficiency of healthcare service providers | [16,26] | |

| Technical support for app usage provided by service providers or nearby individuals | [28,33] | ||

| Timeliness of app services | [16,18] | ||

| Community and social level | Regulation | Strengthening of cybersecurity against personal information | [16,26,33] |

| Support for health app curation | [16] | ||

| Evaluation | Monitoring digital health equity | [16,34] | |

| Enhanced accessibility | Infrastructure development for integration with healthcare systems | [19] | |

| Support for the availability of digital devices such as smartphones | [22] | ||

| Adoption of community preferred technological norms (cultural accessibility) | [26,34] | ||

| Expansion of connections to other apps | [26] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, N.-Y.; Jang, S. App-Based Digital Health Equity Determinants According to Ecological Models: Scoping Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062232

Park N-Y, Jang S. App-Based Digital Health Equity Determinants According to Ecological Models: Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2024; 16(6):2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062232

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Na-Young, and Sarang Jang. 2024. "App-Based Digital Health Equity Determinants According to Ecological Models: Scoping Review" Sustainability 16, no. 6: 2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062232

APA StylePark, N.-Y., & Jang, S. (2024). App-Based Digital Health Equity Determinants According to Ecological Models: Scoping Review. Sustainability, 16(6), 2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062232