Disparity of Rural Income in Counties between Ecologically Functional Areas and Non-Ecologically Functional Areas from Social Capital Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rural Income Inequality in China

2.2. Social Capital

2.3. Social Networks and Social Capital

2.4. Social Capital and Income Inequality

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. The Standard Quantile Regression Model

3.1.2. Decomposition of Differences at Different Quantiles

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Variables

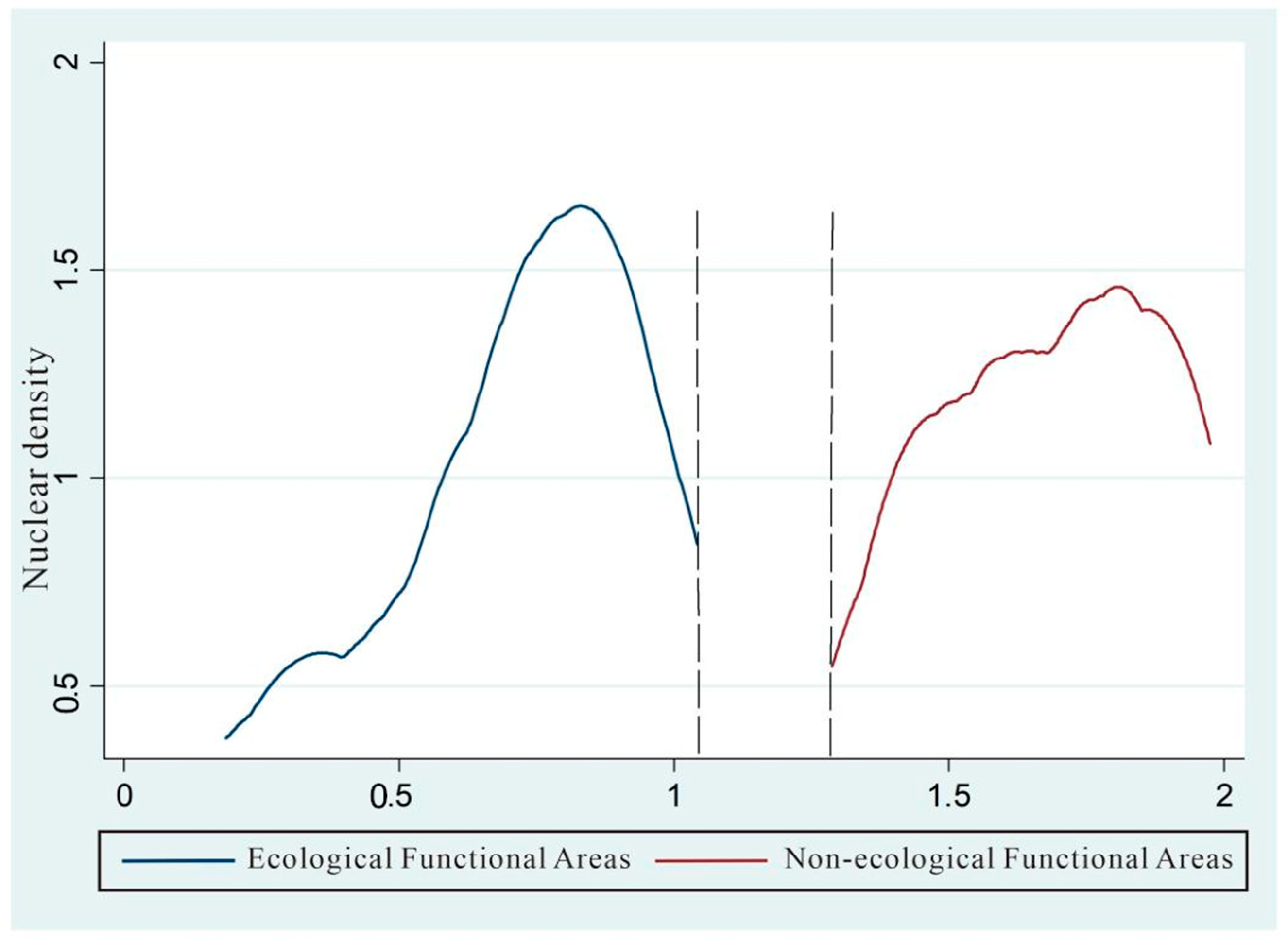

3.3.1. Rural Income

3.3.2. Social Capital

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Quantile Regression Results

4.2. Decomposition of Differences at Different Quantiles

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, X. Income inequality in today’s China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6928–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Changes in the source of China’s regional inequality. China Econ. Rev. 2000, 11, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. China’s (uneven) progress against poverty. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 82, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feldman, M.W.; Li, S.; Daily, G.C. Rural household income and inequality under the Sloping Land Conversion Program in western China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7721–7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Lan, J. The Sloping Land Conversion Program in China: Effect on the Livelihood Diversification of Rural Households. World Dev. 2015, 70, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Rong, Q.; Zhu, W. Did the key priority forestry programs affect income inequality in rural China? Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jin, L. How eco-compensation contribute to poverty reduction: A perspective from different income group of rural households in Guizhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122962. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, P.F.; Patenaude, G.; Ometto, J.P.; Meir, P.; Toledo, P.M.; Coelho, A.; Young, C.E.F. Ecosystem protection and poverty alleviation in the tropics: Perspective from a historical evolution of policy-making in the Brazilian Amazon. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 8, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, H.J. Environment and the Poor: Development Strategies for a Common Agenda; Transaction Book: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, T.; Vosti, S.A. Links between rural poverty and the environment in developing countries: Asset categories and investment poverty. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. The economic linkages between rural poverty and land degradation: Some evidence from Africa. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 82, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Jagger, P.; Babigumira, R.; Belcher, B.; Hogarth, N.J.; Bauch, S.; Börner, J.; Smith-Hall, C.; Wunder, S. Environmental Income and Rural Livelihoods: A Global-Comparative Analysis. World Dev. 2014, 64, S12–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEA. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: A Framework for Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- TEEB. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.; Zhong, L.; Ma, X. Visitors to protected areas in China. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 209, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, J.J.; Safifina, C.; Sissenwine, M.P. Ecology and conservation. Whose fish are they anyway? Science 2011, 293, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abram, N.J.; Gagan, M.K.; Cole, J.E.; Hantoro, W.S.; Mudelsee, M. Recent intensifification of tropical climate variability in the Indian Ocean. Nat. Geosci. 2008, 1, 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China. National Key Ecological Function Zone Transfer Payment (Pilot) Approach. 2009. Available online: https://yss.mof.gov.cn/zhengceguizhang/200912/t20091225_252633.htm (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Fan, C.C. Of belts and ladders: State policy and uneven regional development in post-Mao China. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1995, 85, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.D. Regional development in China: Transitional institutions, embedded globalization, and hybrid economies. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2007, 48, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, S.J.; Janikas, M.V. Regional convergence, inequality, and space. J. Econ. Geogr. 2005, 5, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, E. Geography, nature, and the question of development. Dialogues Hum Geogr. 2011, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.C. Informal sector, income inequality and economic development. Econ. Model. 2011, 28, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Do institutions matter for regional development? Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, J.S. Globalization, decentralization and income inequality: The case of China. Econ. Model. 2013, 31, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.D. Spatiality of regional inequality. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Mellander, C. The Geography of Inequality: Difference and Determinants of Wage and Income Inequality across US Metros. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storper, M. Separate Worlds? Explaining the current wave of regional economic polarisation. J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 18, 247–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Chen, Y. Spatio-temporal change of urban–rural equalized development patterns in China and its driving factors. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 32, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Z. Geographical patterns and anti-poverty targeting post- 2020 in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 1810–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Poverty: An Ordinal Approach to Measurement. Econometrica 1976, 44, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S. Multidimensional Poverty and Its Discontents; OPHI Working Paper; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2011; p. 46. Available online: https://ophi.org.uk/publication/RP-23a (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwald: Westport, CT, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nanetti, R.Y. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Szreter, S.; Woolcock, M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 33, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, D.; Pritchett, L. Cents and Sociability: Household Income and Social Capital in Rural Tanzania. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1999, 47, 871–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, C. Social Capital, Household Welfare and Poverty in Indonesia in Local Level Institutions; Working Paper, No. 6; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, P.F. Economic Growth and Social Capital. Polit. Stud. 2000, 48, 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluccio, J.; Haddad, L.; May, J. Social capital and household welfare in South Africa, 1993–1998. J. Dev. Stud. 2000, 36, 54–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, M.S.; Weber, B.A. Local Social and Economic Conditions, Spatial Concentrations of Poverty, and Poverty Dynamics. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 86, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltz, J.; Guo, Y.; Yao, Y. Lineage networks, urban migration and income inequality: Evidence from rural China. J. Comp. Econ. 2020, 48, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.L. Solidary Groups, Informal Accountability, and Local Public Goods Provision in Rural China. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2007, 101, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yao, Y. Does grassroots democracy reduce income inequality in China? J. Public Econ. 2008, 92, 2182–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Tao, R. Organizational Structure and Collective Action: Lineage Networks, Semiautonomous Civic Associations, and Collective Resistance in Rural China. Am. J. Sociol. 2017, 122, 1726–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padró i Miquel, G.; Qian, N.; Xu, Y.; Yao, Y. Making Democracy Work: Culture, Social Capital and Elections in China; NBER Working Paper; 2018; p. w21058. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w21058/w21058.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Bebbington, A. Social capital and rural intensification: Local organisations and islands of sustainability in the rural andes. Geogr. J. 1997, 163, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 79, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Arnel, N.W.; Thompkis, E.L. Successful adaptation to climate change across scales. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, M.; Kirchner, A. Social Capital and Unemployment: A Macro-Quantitative Analysis of the European Regions. Polit. Stud. 2011, 59, 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlund, H.; Kobayashi, K. Social Capital and Rural Development in the Knowledge Society; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, F.; He, C. Regional difference in social capital and its impact on regional economic growth in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wei, Y.D.; Simon, C.A. Social capital, race, and income inequality in the United States. Sustainability 2017, 9, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, G.; Lavecchia, L. Social capital formation across space: Proximity and trust in European regions. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2013, 36, 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S. Industrialization and spatial income inequality in rural China, 1986-92. Econ. Transit. 1997, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, B.; Shi, L. Income inequality within and across counties in rural China 1988 and 1995. J. Dev. Econ. 2002, 69, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melly, B. Decomposition of Differences in Distribution Using Quantile Regression. Unpublished Working Paper. 2004. Available online: www.siaw.unisg.ch/lechner/melly (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Han, W.; Wei, Y.; Cai, J.; Yu, Y. Furong Chen. Rural nonfarm sector and rural residents’ income research in China. An empirical study on the township and village enterprises after ownership reform (2000–2013). J. Rual. Stud. 2001, 82, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, G. Accounting for income inequality in rural China: A regression-based approach. J. Comp. Econ. 2004, 32, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bilsborrow, R.E.; Song, C.; Tao, S.; Huang, Q. Rural household income distribution and inequality in China: Effects of payments for ecosystem services policies and other factors. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, Y. Demystifying the geography of income inequality in rural China: A transitional framework. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Liao, F.H.; Li, G. A spatiotemporal analysis of county economy and the multi-mechanism process of regional inequality in rural China. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 111, 102073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Langage et Pouvoir Symbolique; Seuil/Points: París, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Capital Cultural, Escuela Y Espacio Social; Siglo XXI Editores: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In Social Epidemiology; Berkman, L.F., Kawachi, I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rostila, M. Social Capital and Health Inequality in European Welfare States; Palrgave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M. Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deth, J.W. Measuring social capital: Orthodoxies and continuing controversies. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2003, 6, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. Assets and Affect in the Study of Social Capital in Rural Communities. Sociol. Rural. 2015, 56, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, M.R.; Thompson, P.J.; Saegert, S. The role of social capital in combating poverty. In Social Capital and Poor Communities; Saegert, S., Thompson, P.J., Warren, M.R., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Flora, C.B.; Flora, J.L. Entrepreneurial Social Infrastructure: A Necessary Ingredient. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 1993, 529, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpham, T.; Grant, E.; Thomas, E. Measuring social capital within health surveys: Key issues. Health Policy Plan. 2002, 17, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, A.; Shrader, E. Cross-Cultural Measures of Social Capital: A Tool and Results from India and Panama; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Available online: https://kipdf.com/cross-cultural-measures-of-social-capital_5ad4a05b7f8b9adb308b462a.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Akçomak, I.S.; Müller-Zick, H. Trust and inventive activity in Europe: Causal, spatial and nonlinear forces. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2015, 60, 529–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E.; Herb, S. Opportunism risk in service traids—A social capital perspective. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2014, 44, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.; Ziglio, E. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: An assets model global health promotion. IUHPE Promot. Educ. 2007, 2, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gradstein, M.; Justman, M. Human capital, social capital, and public schooling. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2000, 44, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Maassen Van Den Brink, H.; Groot, W. 2009. A meta-analysis of the effect of education on social capital. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2009, 28, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogues, T.; Carter, M.R. Social capital and the reproduction of economic inequality in polarized societies. J. Econ. Inequal. 2005, 3, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantarat, S.; Barrett, C.B. Social network capital, economic mobility and poverty traps. J. Econ. Inequal. 2011, 10, 299–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social Networks and Status Attainment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1999, 25, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, E.; Akgungor, S. The contribution of social capital on rural livelihoods: Malawi and the Philippines cases. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2020, 70, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, T.; Deneulin, S. Guest Edıtors’ Introduction. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2007, 8, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.E.; Peter, V.M.; Hurlbert, J.S. Social Resources and Socio-economic Status. Soc. Netw. 1986, 8, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancee, B.; Werfhorst, H.G. Income Inequality and Participation: A Comparison of 24 European Countries. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 41, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalia, L.; Mierina, I. Getting Support in Polarized Societies: Income, Social Networks, and Socioeconomic Context. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 49, 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin, L.I. Social structure and processes of social support. In Social Support and Health; Cohen, S., Syme, S.L., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Willmott, P. Friendship Networks and Social Support; Policy Studies Institute: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, V. Poor people, poor places, and poor health: The mediating role of social networks and social capital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 1501–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvó-Armengol, A.; Jackson, M.O. The effects of social networks on employment and inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 426–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, D.; Rapoport, H. Network effects and the dynamics of migration and inequality: Theory and evidence from Mexico. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 84, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R.; Bassett, G.W. Regression Quantiles. Econometrica 1978, 46, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. The China County Statistical Yearbook (2002–2016). Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/jg/jgsz/xzdw/202302/t20230206_1901800.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Kim, B.-Y.; Kang, Y. Social capital and entrepreneurial activity: A pseudo-panel approach. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2014, 97, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, S.; Keefer, P. Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A Cross-Country Investigation. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 1251–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shideler, D.W.; Kraybill, D.S. Social capital: An analysis of factors influencing investment. J. Soc. Econ. 2009, 38, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcomak, I.S.; ter Weel, B. The impact of social capital on crime: Evidence from the Netherlands. Reg. Sci. Urban. Econ. 2012, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; van Schaik, T. Social capital and growth in European regions: An empirical test. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2005, 21, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, S.; McNeely, C.L. A multi-dimensional perspective on social capital and economic development: An exploratory analysis. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2012, 49, 821–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasingha, A.; Goetz, S.J. US County-Level Social Capital Data, 1990–2005. The Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development; Penn State University: University Park, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Temple, J.; Johnson, P.A. Social Capability and Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1998, 113, 965–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishise, H.; Sawada, Y. Aggregate Returns to Social Capital: Estimates Based on the Augmented-Solow Model. J. Macroecon. 2009, 31, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.A. Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econometrica 1978, 46, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Quantiles | ||||||||

| 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 | |

| 2001 | 0.216 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.168 *** | 0.148 *** | 0.163 *** | 0.158 *** | 0.175 *** | 0.190 * | 0.088 |

| (0.034) | (0.036) | (0.031) | (0.034) | (0.041) | (0.042) | (0.046) | (0.106) | (0.179) | |

| 2002 | 0.227 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.246 *** | 0.274 *** | 0.275 *** | 0.258 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.078 |

| (0.036) | (0.031) | (0.027) | (0.039) | (0.045) | (0.044) | (0.040) | (0.051) | (0.068) | |

| 2003 | 0.241 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.206 *** | 0.223 *** | 0.230 *** | 0.223 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.242 *** | 0.096 |

| (0.052) | (0.029) | (0.026) | (0.030) | (0.028) | (0.043) | (0.058) | (0.031) | (0.108) | |

| 2004 | 0.199 *** | 0.210 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.241 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.287 *** | 0.282 *** | 0.150 *** |

| (0.037) | (0.022) | (0.015) | (0.018) | (0.013) | (0.023) | (0.029) | (0.036) | (0.024) | |

| 2005 | 0.181 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.183 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.223 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.243 *** | 0.159 *** |

| (0.037) | (0.028) | (0.019) | (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.026) | (0.027) | (0.027) | |

| 2006 | 0.169 *** | 0.182 *** | 0.166 *** | 0.170 *** | 0.170 *** | 0.190 *** | 0.257 *** | 0.204 *** | 0.123 *** |

| (0.035) | (0.020) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.013) | (0.016) | (0.030) | (0.046) | (0.027) | |

| 2007 | 0.251 *** | 0.235 *** | 0.225 *** | 0.225 *** | 0.211 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.250 *** | 0.179 *** | 0.148 *** |

| (0.039) | (0.039) | (0.027) | (0.022) | (0.025) | (0.038) | (0.075) | (0.038) | (0.036) | |

| 2008 | 0.196 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.190 *** | 0.182 *** | 0.195 *** | 0.185 *** | 0.216 *** | 0.192 *** | 0.159 *** |

| (0.040) | (0.034) | (0.019) | (0.014) | (0.022) | (0.027) | (0.038) | (0.045) | (0.044) | |

| 2009 | 0.230 *** | 0.190 *** | 0.173 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.218 *** | 0.134 *** |

| (0.026) | (0.041) | (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.035) | (0.039) | (0.036) | (0.041) | (0.046) | |

| 2010 | 0.241 *** | 0.154 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.169 *** | 0.170 *** | 0.171 *** | 0.176 *** | 0.200 *** | 0.151 *** |

| (0.038) | (0.037) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.024) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.049) | (0.032) | |

| 2011 | 0.217 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.157 *** | 0.152 *** | 0.151 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.107 *** | 0.143 *** | 0.074 |

| (0.051) | (0.033) | (0.025) | (0.030) | (0.037) | (0.036) | (0.038) | (0.040) | (0.066) | |

| 2012 | 0.239 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.160 *** | 0.172 *** | 0.156 *** | 0.119 ** | 0.124 *** | 0.134 *** | 0.056 |

| (0.025) | (0.039) | (0.022) | (0.027) | (0.030) | (0.048) | (0.041) | (0.046) | (0.065) | |

| 2013 | −0.075 | 0.064 | 0.086 | 0.134 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.127 *** | 0.138 *** | 0.126 ** | 0.179 *** |

| (0.127) | (0.093) | (0.073) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.038) | (0.046) | (0.046) | (0.048) | |

| 2014 | −0.057 | −0.057 | −0.057 | −0.107 | −0.107 | −0.107 | 0.040 | 0.041 | 0.041 |

| (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.086) | (0.090) | (0.089) | (0.077) | (0.083) | (0.071) | (0.064) | |

| 2015 | −0.045 | −0.045 | −0.021 | −0.021 | −0.083 | −0.003 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.031 |

| (0.061) | (0.061) | (0.063) | (0.071) | (0.084) | (0.080) | (0.068) | (0.256) | (0.257) | |

| Year | Quantiles | ||||||||

| 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 | |

| 2001 | 0.422 *** | 0.419 *** | 0.418 *** | 0.403 *** | 0.378 *** | 0.363 *** | 0.356 *** | 0.326 *** | 0.287 *** |

| (0.023) | (0.016) | (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.028) | (0.013) | |

| 2002 | 0.419 *** | 0.414 *** | 0.415 *** | 0.412 *** | 0.384 *** | 0.365 *** | 0.359 *** | 0.326 *** | 0.291 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.010) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.011) | (0.021) | (0.017) | |

| 2003 | 0.433 *** | 0.411 *** | 0.420 *** | 0.414 *** | 0.386 *** | 0.362 *** | 0.348 *** | 0.312 *** | 0.290 *** |

| (0.032) | (0.018) | (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.016) | (0.015) | (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.014) | |

| 2004 | 0.380 *** | 0.401 *** | 0.391 *** | 0.394 *** | 0.372 *** | 0.346 *** | 0.317 *** | 0.280 *** | 0.273 *** |

| (0.015) | (0.018) | (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.016) | |

| 2005 | 0.414 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.392 *** | 0.377 *** | 0.353 *** | 0.334 *** | 0.303 *** | 0.281 *** | 0.269 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.010) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.021) | (0.013) | (0.020) | |

| 2006 | 0.406 *** | 0.414 *** | 0.410 *** | 0.372 *** | 0.350 *** | 0.315 *** | 0.283 *** | 0.263 *** | 0.250 *** |

| (0.016) | (0.009) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.016) | (0.012) | (0.016) | |

| 2007 | 0.460 *** | 0.443 *** | 0.435 *** | 0.400 *** | 0.373 *** | 0.333 *** | 0.298 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.242 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.012) | (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.016) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.016) | |

| 2008 | 0.428 *** | 0.406 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.387 *** | 0.368 *** | 0.320 *** | 0.287 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.256 *** |

| (0.020) | (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.017) | (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.019) | (0.016) | (0.021) | |

| 2009 | 0.421 *** | 0.397 *** | 0.398 *** | 0.379 *** | 0.360 *** | 0.321 *** | 0.291 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.250 *** |

| (0.018) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.021) | (0.019) | |

| 2010 | 0.413 *** | 0.392 *** | 0.371 *** | 0.345 *** | 0.319 *** | 0.297 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.250 *** | 0.222 *** |

| (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.016) | (0.014) | |

| 2011 | 0.390 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.368 *** | 0.351 *** | 0.335 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.267 *** | 0.252 *** | 0.226 *** |

| (0.020) | (0.014) | (0.012) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.014) | (0.015) | (0.010) | (0.011) | |

| 2012 | 0.385 *** | 0.378 *** | 0.366 *** | 0.354 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.308 *** | 0.276 *** | 0.239 *** | 0.222 *** |

| (0.022) | (0.014) | (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.014) | (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.016) | |

| 2013 | 0.453 *** | 0.419 *** | 0.374 *** | 0.285 *** | 0.212 *** | 0.210 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.169 *** | 0.153 *** |

| (0.098) | (0.048) | (0.052) | (0.056) | (0.050) | (0.045) | (0.044) | (0.038) | (0.042) | |

| 2014 | 0.408 *** | 0.413 *** | 0.391 *** | 0.314 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.217 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.162 *** | 0.149 *** |

| (0.101) | (0.065) | (0.071) | (0.068) | (0.060) | (0.045) | (0.039) | (0.036) | (0.044) | |

| 2015 | 0.598 *** | 0.469 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.406 *** | 0.296 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.183 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.139 *** |

| (0.127) | (0.047) | (0.079) | (0.093) | (0.055) | (0.062) | (0.055) | (0.042) | (0.046) | |

| Year | Decomposition of Differences | Quantiles | ||||||||

| 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 | ||

| 2001 | Social capital difference | 0.479 | 0.481 | 0.453 | 0.392 | 0.323 | 0.266 | 0.242 | 0.194 | 0.206 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.079 | 0.114 | 0.146 | 0.174 | 0.149 | 0.156 | 0.129 | 0.131 | 0.086 | |

| Total difference | 0.558 | 0.595 | 0.599 | 0.566 | 0.472 | 0.422 | 0.371 | 0.325 | 0.292 | |

| 2002 | Social capital difference | 0.344 | 0.346 | 0.35 | 0.351 | 0.348 | 0.344 | 0.339 | 0.331 | 0.317 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.034 | 0.062 | 0.079 | 0.093 | 0.103 | 0.116 | 0.126 | 0.138 | 0.147 | |

| Total difference | 0.378 | 0.408 | 0.429 | 0.444 | 0.451 | 0.46 | 0.465 | 0.469 | 0.464 | |

| 2003 | Social capital difference | 0.358 | 0.363 | 0.364 | 0.363 | 0.358 | 0.356 | 0.347 | 0.34 | 0.326 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.032 | 0.066 | 0.088 | 0.102 | 0.116 | 0.128 | 0.144 | 0.162 | 0.173 | |

| Total difference | 0.39 | 0.429 | 0.452 | 0.465 | 0.474 | 0.484 | 0.491 | 0.502 | 0.499 | |

| 2004 | Social capital difference | 0.437 | 0.414 | 0.401 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.345 | 0.328 | 0.313 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.015 | 0.055 | 0.076 | 0.093 | 0.103 | 0.113 | 0.125 | 0.14 | 0.158 | |

| Total difference | 0.452 | 0.469 | 0.477 | 0.482 | 0.48 | 0.475 | 0.47 | 0.468 | 0.471 | |

| 2005 | Social capital difference | 0.45 | 0.419 | 0.397 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.334 | 0.321 | 0.31 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.041 | 0.09 | 0.119 | 0.138 | 0.151 | 0.165 | 0.182 | 0.201 | 0.221 | |

| Total difference | 0.491 | 0.509 | 0.516 | 0.519 | 0.516 | 0.515 | 0.516 | 0.522 | 0.531 | |

| 2006 | Social capital difference | 0.428 | 0.402 | 0.386 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.316 | 0.302 | 0.292 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.045 | 0.103 | 0.13 | 0.145 | 0.154 | 0.165 | 0.182 | 0.205 | 0.228 | |

| Total difference | 0.473 | 0.505 | 0.516 | 0.514 | 0.506 | 0.499 | 0.498 | 0.507 | 0.52 | |

| 2007 | Social capital difference | 0.375 | 0.362 | 0.353 | 0.34 | 0.326 | 0.311 | 0.295 | 0.281 | 0.267 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.076 | 0.124 | 0.149 | 0.166 | 0.175 | 0.182 | 0.194 | 0.215 | 0.223 | |

| Total difference | 0.451 | 0.486 | 0.502 | 0.506 | 0.501 | 0.493 | 0.489 | 0.496 | 0.49 | |

| 2008 | Social capital difference | 0.4 | 0.373 | 0.356 | 0.341 | 0.326 | 0.309 | 0.293 | 0.279 | 0.27 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.034 | 0.081 | 0.106 | 0.121 | 0.13 | 0.139 | 0.152 | 0.171 | 0.188 | |

| Total difference | 0.434 | 0.454 | 0.462 | 0.462 | 0.456 | 0.448 | 0.445 | 0.45 | 0.458 | |

| 2009 | Social capital difference | 0.365 | 0.35 | 0.337 | 0.322 | 0.308 | 0.294 | 0.28 | 0.268 | 0.26 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.056 | 0.092 | 0.115 | 0.131 | 0.141 | 0.15 | 0.164 | 0.181 | 0.199 | |

| Total difference | 0.421 | 0.442 | 0.452 | 0.453 | 0.449 | 0.444 | 0.444 | 0.449 | 0.459 | |

| 2010 | Social capital difference | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.312 | 0.3 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.258 | 0.247 | 0.235 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.106 | 0.138 | 0.156 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.204 | 0.216 | 0.225 | |

| Total difference | 0.426 | 0.458 | 0.468 | 0.469 | 0.465 | 0.462 | 0.462 | 0.463 | 0.46 | |

| 2011 | Social capital difference | 0.256 | 0.267 | 0.271 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.239 | 0.23 | 0.224 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.086 | 0.12 | 0.142 | 0.157 | 0.168 | 0.176 | 0.184 | 0.201 | 0.222 | |

| Total difference | 0.342 | 0.387 | 0.413 | 0.424 | 0.427 | 0.426 | 0.423 | 0.431 | 0.446 | |

| 2012 | Social capital difference | 0.252 | 0.272 | 0.275 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.242 | 0.231 | 0.224 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.101 | 0.123 | 0.14 | 0.153 | 0.162 | 0.17 | 0.175 | 0.189 | 0.207 | |

| Total difference | 0.353 | 0.395 | 0.415 | 0.424 | 0.424 | 0.422 | 0.417 | 0.42 | 0.431 | |

| 2013 | Social capital difference | 0.263 | 0.277 | 0.273 | 0.28 | 0.288 | 0.282 | 0.292 | 0.306 | 0.321 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.182 | 0.136 | 0.136 | 0.127 | 0.102 | 0.096 | 0.086 | 0.071 | 0.076 | |

| Total difference | 0.445 | 0.413 | 0.409 | 0.407 | 0.39 | 0.378 | 0.378 | 0.377 | 0.397 | |

| 2014 | Social capital difference | 0.384 | 0.348 | 0.345 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.242 | 0.202 | 0.186 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.097 | 0.204 | 0.202 | 0.217 | 0.225 | 0.222 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.175 | |

| Total difference | 0.481 | 0.552 | 0.547 | 0.523 | 0.471 | 0.454 | 0.435 | 0.395 | 0.361 | |

| 2015 | Social capital difference | 0.479 | 0.481 | 0.453 | 0.392 | 0.323 | 0.266 | 0.242 | 0.194 | 0.206 |

| Sectoral difference | 0.079 | 0.114 | 0.146 | 0.174 | 0.149 | 0.156 | 0.129 | 0.131 | 0.086 | |

| Total difference | 0.558 | 0.595 | 0.599 | 0.566 | 0.472 | 0.422 | 0.371 | 0.325 | 0.292 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Song, W. Disparity of Rural Income in Counties between Ecologically Functional Areas and Non-Ecologically Functional Areas from Social Capital Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072661

Zhang H, Song W. Disparity of Rural Income in Counties between Ecologically Functional Areas and Non-Ecologically Functional Areas from Social Capital Perspective. Sustainability. 2024; 16(7):2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072661

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hong, and Wenfei Song. 2024. "Disparity of Rural Income in Counties between Ecologically Functional Areas and Non-Ecologically Functional Areas from Social Capital Perspective" Sustainability 16, no. 7: 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072661

APA StyleZhang, H., & Song, W. (2024). Disparity of Rural Income in Counties between Ecologically Functional Areas and Non-Ecologically Functional Areas from Social Capital Perspective. Sustainability, 16(7), 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072661