Abstract

The impacts of COVID-19 on cities across the United Kingdom were significant and diverse, whilst ongoing climate-related, sustainability and social challenges were highlighted and sometimes amplified. Lessons from organisational and citizen experiences and their responses have the potential to improve local sustainability and resilience to global events; hence, they must be examined. We report findings from a project conducted in Preston (UK) exploring how COVID-19 recovery might accelerate organisation-led and citizen-led action for the wellbeing of people, places and the planet. The project used a settings approach to public health and combined qualitative research with conceptual development; the former involved online interviews and group dialogues with members of several local anchor institutions, whilst the latter examined synergy between community wealth building, Doughnut Economics and place-based climate action. We explore two themes—anchor institutions’ strategic priorities and plans; ‘building back better’, and its future sustainability implications. These revealed four cross-cutting aspects: wellbeing, tackling societal inequalities, collaborative working, and COVID-19 as a catalyst for transformative change. Informed by ‘Doughnut-Shaped Community Wealth Building’, organisations are encouraged to embed commitment to equitable and inclusive climate action; consolidate the co-operative approach developed during the pandemic at strategic, operational and grassroots levels; take a nuanced approach to future work policies and practices; work across anchor institutions to advocate collectively for supportive national-level policy to build a sustainable, wellbeing economy.

Keywords:

organisations; citizens; climate; community; sustainability; resilience; justice; COVID-19; UK 1. Introduction

COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency of international concern in 2020 [1] and has been highly disruptive—with social, economic and environmental impacts for nations, municipalities, communities, families and citizens. Occurring against the backdrop of global crises such as climate change and biodiversity loss, the pandemic has highlighted that human health is inextricably connected to planetary, economic and societal wellbeing [2,3]. It has been argued that COVID-19 should not be viewed as separate from the climate and ecological crises—with both being driven by an unsustainable food system linked to habitat destruction and biodiversity decline [4]. As such, they are both associated with and impact upon global efforts to meet important sustainability goals, including United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2 (Zero Hunger), 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), 13 (Climate Action) and 15 (Life on Land).

Reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [5,6,7] concluded that without urgent action to cut emissions, there will be irreversible changes to the global climate system and ecosystems. While climate change represents a global emergency, cities and towns can be understood as ‘testbeds’ for mitigation, adaptation and decarbonisation [8], with this local focus complementing national- and international-level action [9,10]. The Place-Based Climate Action Network (P-CAN)—which part-funded this study—is a five-year Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) funded project that connects researchers and decision-makers from public, private and third sectors to catalyse transformative place-based change [11]. This paper reports on the project ‘Climate Resilience, Social Justice and COVID-19 Recovery in Preston’, conducted by a research team from the University of Central Lancashire that explored opportunities for climate action and social justice arising during a period of national recovery from COVID-19. The team were particularly interested in how these opportunities could translate into practice the political rhetoric of ‘build back better’, serving as a springboard to accelerate organisation and citizen-led action towards a future that prioritises the wellbeing of people, places and the planet. The project combined qualitative empirical research with conceptual development, the latter examining synergy between community wealth building (CWB), Doughnut Economics and place-based climate action. The study is unique in that this is the first reflective, co-researched project conducted since the pandemic, involving the public, private and third sectors to understand differential experiences and explore future-orientated solutions for North-West England.

Preston, a city in North-West England with a population of 147,900, was well placed to confront the difficulties and hardships that suddenly struck the UK with COVID-19. Following the collapse of the Tithebarn regeneration project in November 2011, the local Council, along with partners and stakeholders in the city, sought alternative means of creating and retaining local wealth. Supported by the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES) and drawing learning from both Cleveland (Ohio, USA) and Mondragón (Basque Country, Spain), this later became identified as a CWB project dubbed the ‘Preston Model’ [12]. CWB offers a democratic place-based approach to building more sustainable, resilient, equitable and relocalised economies [13] and encouraging institutions to procure in ways that benefit local communities, working to ensure that wealth created locally is more equally owned, equitably distributed and retained in the local economy through community-based, co-operative and public ownership. This meant that by the time the pandemic hit, communities, local businesses, voluntary organisations and so-called ‘anchor institutions’ (large institutions that are rooted in place, such as the local hospital, the university, etc.) had already developed a culture of mutuality and cooperation. Even if some of the progress in real terms had been sparse, at least a culture of mutual support and cooperation had been encouraged [14]—furthermore, Preston had recently been named the most improved and most rapidly improving city in the UK [15], and best city to live and work in North-West England [16,17].

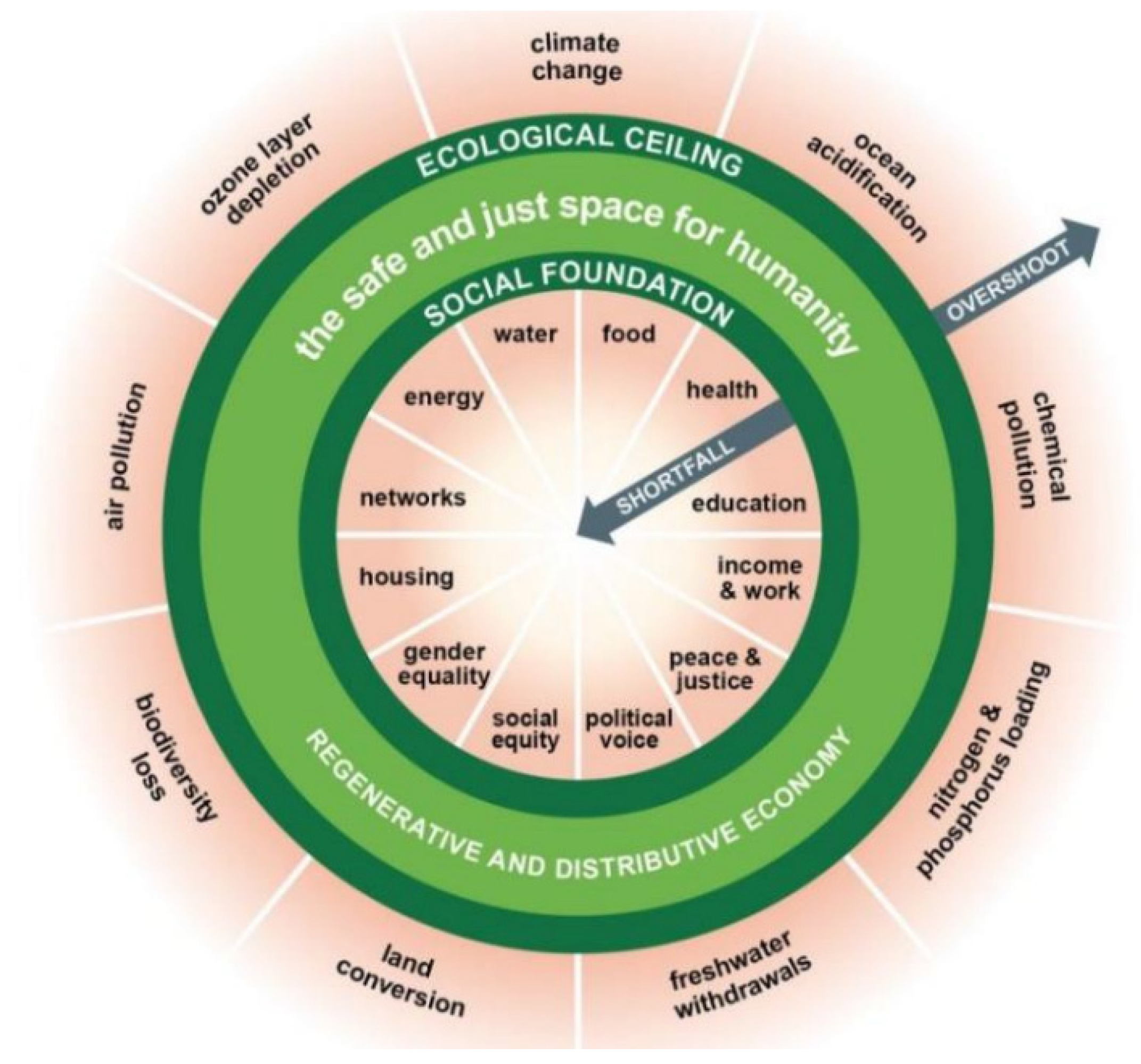

It is noteworthy that Preston City Council’s refreshed vision, Community Wealth Building 2.0 [18], embraces a commitment not only to social justice but also to place-based climate leadership, governance and action, reflecting the Council’s decision to declare a climate emergency and a target of net-zero by 2030 [19]. However, it remains that CWB projects around the world have tended to focus more strongly on local socio-economic concerns, building what is sometimes termed ‘new municipalism’ [20]. This is why this study’s focus on place-based climate action was framed using ‘Doughnut Economics’ alongside CWB. Doughnut Economics aims to meet the needs of all people within the means of the living planet [21]. The visual representation (see Figure 1) presents two concentric rings: a social foundation to protect human wellbeing with no-one falling short of life’s essentials—informed by the Sustainable Development Goals [22]—and an ecological ceiling to ensure that we do not collectively overshoot the Earth’s planetary boundaries—informed by the work of the Stockholm Resilience Institute [23,24]. Between these boundaries lies an ecologically safe and socially just space in which humanity can thrive. While initially designed to be used at the global level, Doughnut Economics has now been downscaled with cities and counties experimenting with using it as a decision-making tool to guide and measure socio-economic and environmental progress. A well-developed example of this ‘downscaling’ can be found in Amsterdam [25,26]. Whilst we do not explicitly conduct an assessment of Preston using the Doughnut Economics model, it does directly inform our work as we explore how the needs of various actors might be met more effectively in the future within sustainable and planetary boundaries. In particular, our study deals with several of the social criteria considered by the model, such as social equity, health, housing, income and work, and networks, whilst also considering what is necessary to constitute a just space for humanity (in a local context) when dealing with macro-scale challenges, such as climate change.

Figure 1.

The Doughnut of Social and Planetary Boundaries (Source: [21]). (Credit: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier. CC-BY-SA 4.0).

2. Aims and Methods

Picking up cues from CWB and Doughnut Economics, the project aimed to explore how recovery from COVID-19 could translate into practice the rhetoric of ‘build back better’ and create innovative opportunities for climate action and social justice—examining how disruption from one threat might galvanise momentum to address another. This was achieved theoretically using a settings approach to public health, which has a number of key characteristics at the conceptual level [27], including that health is understood using an ecological model (that is, an interplay of environmental, organisational and personal factors); viewing settings (in the context of this research, anchor institutions) as dynamic complex systems with inputs, throughputs, outputs and impacts—characterised by integration, interconnectedness, interrelationships and interdependencies between different elements; and a focus on positive change within organisations, balancing top-down commitment with bottom-up stakeholder engagement. This framework informed our approach to studying the anchor institutions using ‘whole system thinking’ [28]. It was guided by the four following research questions:

- How has COVID-19 been experienced by Preston’s anchor institutions and communities, and what have they learned about their resilience, responsiveness and adaptability?

- Has COVID-19 offered glimpses of a different future—and if so, what might this look like?

- What are the perceived links with and opportunities to address climate change and related ecological and social challenges during Preston’s recovery from COVID-19, and what does this mean for organisational and community-led action?

- What potential synergy is offered by exploring the convergence and intersection of place-based climate action, CWB and Doughnut Economics, and what might such an integrated city-based approach to fostering human flourishing within planetary boundaries mean for transformative recovery from COVID-19?

For data collection methods congruent to the settings approach, we wished to capture voices from selected anchor organisations and Preston’s diverse communities. Therefore, the primary empirical data collection methods were semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Ten interviews and 12 focus groups were conducted in 2021 with a total of 70 stakeholders—including staff and students from UCLan; officers and councillors from PCC; staff, tenants, and Board members from Community Gateway Association; Lancashire Enterprise Partnership; Preston Vocational Centre; Climate Action Preston; and individuals from Preston’s voluntary, community and faith sectors (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants interviewed by anchor organisations.

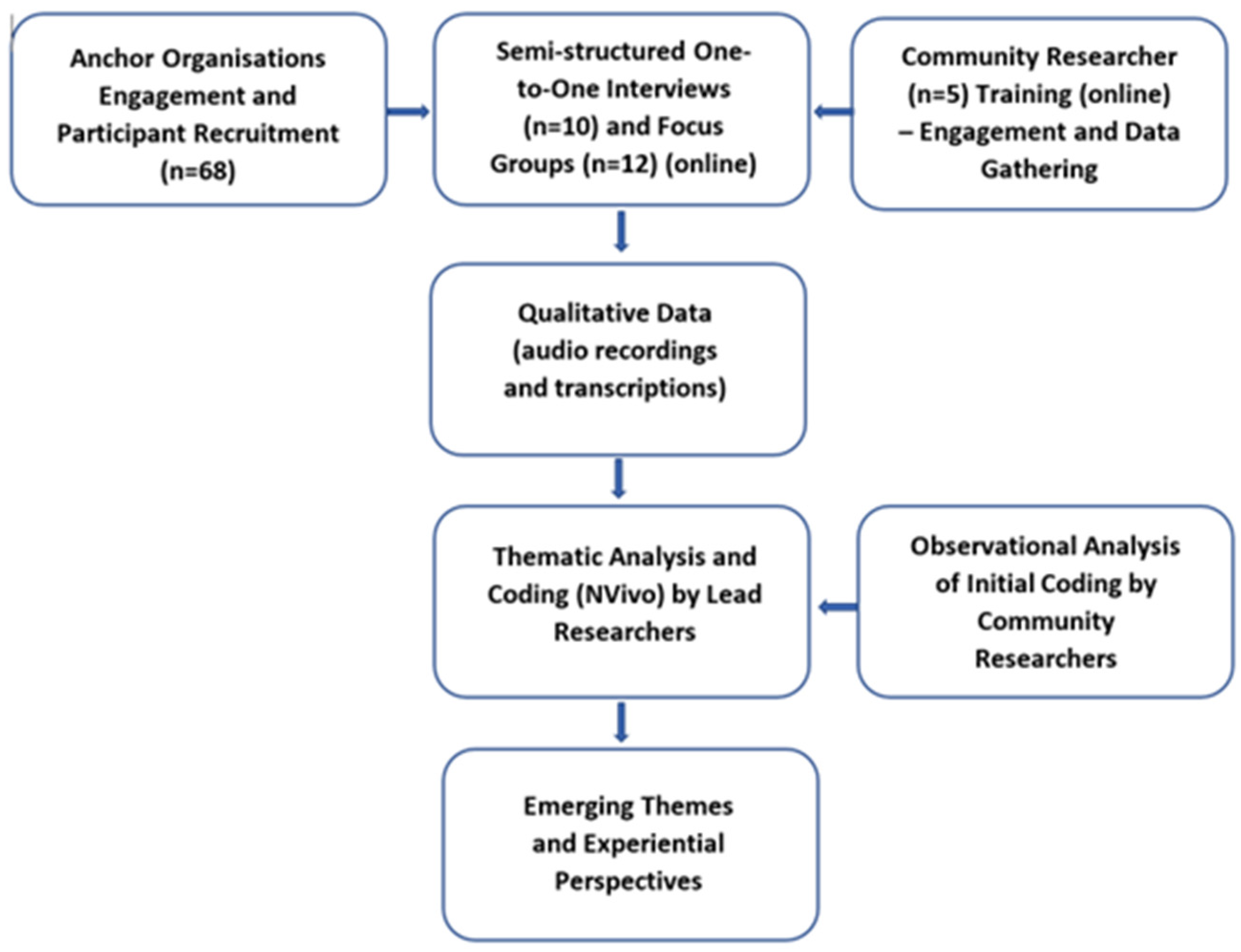

Anchor organisations and institutions were suggested by the Project Oversight Group. The research team co-ordinated with a key point of contact in each of the anchor organisations to send invitations to all members of their organisation to participate in the focus groups. There were no exclusion criteria: every individual who responded and was able to join online focus groups at allotted times was able to participate. In addition to this, purposive sampling was used for interviews with key stakeholders in anchor institutions and voluntary sector networks, which was also determined by the Project Oversight Group, which included representatives from the participating anchor institutions and voluntary sector networks. Data collection was entirely online due to COVID-19 restrictions, a constraint that also influenced the sample of stakeholders that could be readily accessed (see ‘Section 4’). Focus groups and interviews lasted between 30 min and 1 h. Interview schedule prompts concerned the following themes: Reflections on the impact of COVID-19 on the participants’ organisation; considerations for the future of their organisation as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic; a discussion around the different organisations’ strategic values regarding sustainability, wellbeing and resilience. In accordance with the research team’s commitment to co-production, five volunteer community researchers were recruited via existing local community networks and trained online by the research team to work as co-researchers, jointly facilitating focus groups and being invited to ‘quality check’ analysed data. The community researchers had no specific professional or academic background. They were recruited because they lived in the local area and were involved in local community groups. Each focus group had a university researcher and a community researcher present, but one-to-one interviews were conducted by a researcher only. These ‘co-research’ methodological stages are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Co-research flow chart showing the involvement of anchor organisations and community researchers in data gathering and analysis.

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Central Lancashire (Reference Number: HEALTH 0131), and interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber. Using NVivo 1.6.2 & 1.7.1 qualitative data management software, data were subjected to a two-stage manual thematic analysis [29] using a standard thematic coding framework. One member of the research team identified themes within the raw data by using a line-by-line analysis of verbatim transcripts and interpreting their implications in relation to the aims of the research [30]. Initial analysis and coding were cross-checked and refined by other research team members to produce a first draft of the analysis, which was then quality-checked by other research team members, including community researchers. All individual interviewees consented to be identified by role and organisation, and those identifiable in the data were offered the opportunity to ‘member-check’ quotes to be used in the final report for accuracy and, in some cases, sensitivity [31].

Complementing the empirical data collection, a rapid review of the literature and other relevant documentation was undertaken [32]. Forming a separate report, this contextualises place-based climate action, CWB and Doughnut Economics, explores how the three approaches intersect and interrelate, and captures and distils learning relating to their local application. This conceptual development was further supported by a round-table workshop and webinar.

3. Results

Four interconnected overarching themes emerged from the data analysis: Impacts of COVID-19; Institutional responses to COVID-19; Anchor Institutions’ Strategic Priorities and Plans; ‘Building Back Better’ and its Future Sustainability Implications for Preston. Reflecting an interest in the future and in sustainability, this paper explores the latter two of these.

3.1. Anchor Institutions’ Strategic Priorities and Plans

A key thematic focus was anchor institutions’ strategic priorities and plans. Within this, sub-themes were quality of life, sustainability and climate action, CWB, partnerships, and a focus on the long-term.

A commitment to quality of life was understood to have been embedded in anchor institutions’ strategies over many years, with top-level ‘buy-in’ being key to its prioritisation. PCC’s focus on CWB was understood to reinforce this, closely entwining it with commitments to equality and social justice:

“[Cllr Brown] …emerged onto the cabinet with that community social value responsibility…and has progressed up to leadership…CWB is a…fundamental agenda item…Making sure that there’s inclusivity, fairness…all of those things are fundamental to the policies that we develop and, therefore, the business that we deliver.”[Interview—Deputy Chief Executive, PCC]

Participants from other anchor institutions reflected that the pandemic has strengthened this focus, encouraging a more proactive approach and further highlighting anchor institutions’ responsibility to look after communities and their quality of life. This was often connected with sustainability and climate action, for example, in relation to Lancashire Enterprise Partnership’s Social Value Framework and Toolkit [33], which sees taking care of the most vulnerable as intrinsic to the sustainability of communities. The importance of a holistic approach to quality of life was noted, with housing, skills development, employment, food security and social support identified as key determinants.

Sustainability and climate action were understood to be key strategic priorities guiding the future direction of the three anchor institutions involved in the research study. Participants suggested that action on the climate and ecological emergencies—with appropriate accountability and reporting mechanisms—were now fundamental to their future plans and would need to be built in to all their policies. For UCLan, both the Vice-Chancellor and Chair of the Board emphasised the key role of the University’s new strategic plan and related sub-strategy in driving the sustainability agenda and the significance of the Board’s oversight and governance in leading meaningful and courageous action:

“The [Board’s Environment Working Group] is looking at all aspects…It’s absolutely fundamental…We’re talking about the future of the human race here, I can’t think of anything that could be more important…I think there are whole areas where we should really be much, much more radical.”[Interview—Chair of Board, UCLan]

PCC’s leadership highlighted how it has demonstrated its commitment to prioritising climate action by declaring a climate emergency, incorporating commitments within its refreshed CWB Strategy [21] and creating a dedicated cabinet post supported by a working group:

“There’s also been a climate change task and finish group and they’ve got a report coming out fairly soon…We’re a bit disappointed, obviously, COVID has delayed that…But with climate change and things like green energy and stuff like that, you’ve got to do the right thing at the right time to maximise the effect.”[Interview—Deputy Leader, PCC]

Alongside this, there was an appreciation of the enormous amount of work remaining and the challenges of effectively prioritising and funding action:

“I’m yet to be convinced that having a cabinet member for climate change will actually make any difference at all. Because the cabinet members don’t do the work…and if we don’t have the staff and the resource to back that up, then I’m not exactly sure what it is we’re going to achieve.”[Focus Group—Officers, Preston City Council #1]

While noting this financial challenge, participants from CGA highlighted the inclusion of climate action within future plans, one priority being the incorporation of energy efficiency within new builds and retrofits. Participants from Preston Vocational Centre, a subsidiary of CGA, echoed this commitment:

“I think we’ve always had an eye on sustainability and environmental impacts…We pride ourselves on as much recyclability as we can…We have a waste transfer system… And [we ask] ‘do we actually need that much resource?”[Focus Group—Preston Vocational Centre]

CWB, as encapsulated in the Preston Model, is a key strategic driver for PCC. While appreciating the significant financial and cultural challenges involved, participants emphasised that commitments to quality of life, sustainability and climate action are firmly incorporated within the refreshed strategy ‘CWB 2.0′:

“We wanted to make sure that climate change was embedded [in our CWB strategy] and given proper due status…[We’re] trying to embed environmental consciousness into everything.”[Interview—Chief Executive, PCC]

The Preston Model is thus perceived as an opportunity to influence partners and put alternatives in place—in procurement, employment and economic democratisation. This ambition was echoed by other anchor institutions such as UCLan and CGA:

“Employment opportunities, employment skills that we give our tenants, creating that wealth locally…What we do complements that Preston Model naturally…Also, with the procurement exercises we do, we’re always conscious of the Preston pound and making sure we choose local suppliers where we can.”[Focus Group—Staff, CGA]

It was argued that while the work of many in the voluntary, community and faith sectors supports the Preston Model, organisations on the ‘coal face’ are often too distracted in seeking short-term ‘survival’ income to develop their understanding and engagement:

“We were approached at the beginning to get more involved but sometimes it can be quite difficult in the voluntary sector, because of the funding aspect…But I really would like to explore the Preston Model a little bit more and how we can kind of work within that because we need to be sustainable.”[Focus Group—VCFS]

Looking ahead, several participants highlighted Doughnut Economics, suggesting that its adoption would offer an important opportunity to strengthen the Preston Model into the future, amplifying its focus on the wellbeing of people, communities and the planet:

“The different future, for Let’s Grow Preston, is to follow the principles of Doughnut Economics. Rather than…measuring wealth, let’s look at wellbeing. Let’s encourage the economy to be driven by people feeling valued, by people having a voice and being heard and aspirations growing…Being able to grasp this positive glimpse of a future where communities are more cohesive, where people feel valued, are more resilient, are stronger…if you build stronger more resilient communities, then climate change will become part of the solution”.[Focus Group—VCFS]

While participants reflected that Preston’s commitment to both CWB and climate action pre-dated the pandemic and had, in many ways, been delayed rather than accelerated, they felt that the Preston Model has the potential to support COVID-19 recovery and help galvanise a stronger cross-sector approach to climate action, particularly in areas such as recycling and energy efficiency and generation. More widely, it was noted that Preston’s resilient response to the pandemic was strengthened by partnerships, some already in existence, some newly forged. Anchor institutions viewed this collaborative approach as essential in pursuing common strategic priorities highlighted above:

“I don’t think there’s any point in us doing our own things individually. If we could do things collectively and work together it would be better really, and I think there is a desire to try and pull together.”[Interview—Director, Estates and Capital Projects, UCLan]

Participants from multiple sectors discussed how the pandemic had galvanised inter-organisation partnerships, accelerated the use of virtual meeting platforms and broken-down traditional silos, cutting through ‘red tape’ and encouraging differences to be put aside:

“Competition suspended for a period of time and there was kind of co-operation between businesses for the greater good I think, which was really helpful.”[Interview—Chief Executive, Lancashire Enterprise Partnership]

“It has brought many community organisations together, collaborating not competing.”[Focus Group—VCFS]

For PCC, the wide-ranging commitment to CWB was seen to offer an important focus and opportunity to use the pandemic as a catalyst to work in partnership to address inequality:

“Working with the other anchor institutions, the hospital, the University, places like that, to try and get better wages, getting poorer people into better jobs, to raise the floor levels of poverty…We really need to make better inroads into it and COVID has highlighted that.”[Interview—Deputy Leader, Preston City Council]

Looking ahead at how the anchor institutions’ commitments to sustainability and climate action could be effectively implemented, there was again a recognition that partnership working is essential:

“I think collaboration’s going to be key as well, particularly around the carbon neutral agenda and meeting those targets. Right across the sector, there’s going to be collaboration, in terms of procurement, to gain efficiencies to actually make this work and make it deliverable.”[Focus Group—Mixed, CGA]

A number of participants highlighted the importance of partnership, including the voices of ‘ordinary people’ through the use of deliberative democracy, a focus that can challenge perceptions of political leaders in local government:

“And to be able to move forward, we need to listen to those climate assemblies that are made up of regular people because politicians do not always have the right answers.”[Focus Group—UCLan #5]

The data also suggested that the experience of COVID-19 has encouraged anchor institutions increasingly to embed a focus on the long-term into their strategic planning:

“We need to move away from these one-year budgets, to be looking at least three to five years, and this longer-term projection about growth or shrinkage because otherwise… we’re never going to have time to plan to do it differently. It’s always knee-jerk…”[Interview—Director, Estates & Capital Projects, UCLan]

For some, the experience of the pandemic combined with the imperative of looking ahead to the challenge of climate change prompted a review of organisational strategy to ensure ‘fit of purpose’ into the future:

“COVID came in the early, mid-point of [our five-year corporate plan]. We’ve had a good look at that plan to make sure…it’s still deliverable... And I think…the vast majority of what’s in that plan… is still appropriate, is still relevant.”[Focus Group—Executive Team & Board Members, CGA]

3.2. Building Back Better’ and Its Future Sustainability Implications

Closely related to anchor institutions’ strategic priorities and plans, a further key thematic focus was ‘building back better’ and its future sustainability implications for Preston. Sub-themes were fairness and social justice, buildings and the physical environment, shifting mindsets, the gap between rhetoric and reality, and embedding enduring changes in working practices.

Reflecting on how COVID-19 could serve as a catalyst to build a better and more sustainable future, participants emphasised the importance of taking a comprehensive approach to promoting fairness and social justice, which have been both spotlighted and impacted by the pandemic:

“There’s lots of areas that we are reinvigorated about…Public health and health inequalities… [have] an enormous bearing upon people’s quality of life and life chances…Linkages to educational disparities and housing, living conditions, economic outcomes and everything else, are of enormous significance…And everything we do, in terms of environment, whether enabling cycling, walking, public parks, open spaces…all the recreation, whether linked in to the provision of arts, culture, sporting activity, things that improve physical and mental health…it should be a holistic approach.”[Interview—Chief Executive, PCC]

Significantly, the collaborative approach catalysed at the grassroots level looked set to continue and evolve with a specific concern to benefit disadvantaged communities:

“Right at the very beginning there were very real shortages [of food]…that put a lot of people in a real collaborative mode…We’ve now got…about 50 community organisations sharing waste food and they’re just collaborating…to the benefit of communities and those most in need…There’s a real appetite from those organisations to look at new things beyond COVID, beyond the crisis provision of food…working together at a neighbourhood level to look at…sustainability of food and all of that. So, I think there’s a real opportunity that has arisen now.”[Focus Group, Officers, PCC #2]

When talking about the rhetoric of ‘building back better’, a number of people talked about buildings and the physical environment. At the macro level, there was a focus on the transformative potential of UCLan’s new Student Centre and Square and on city development that ensures equity, viability, connectivity and vitality:

“We’ve been contemplating, what does COVID recovery mean, in all sorts of different areas…how can we improve the lives of the most disadvantaged, how can we ensure that the city has a viable future? [Also], what will the city centre be moving forward—the challenge of the high street? So…we want to position Preston as an accessible, affordable, attractive city, with great connectivity.”[Interview—Chief Executive, Preston City Council]

At an organisational level, participants highlighted the importance of and tensions involved in reviewing space utilisation in the context of blended working, estate planning and decarbonisation:

“Universities…don’t use space very efficiently…So it’s…creating a lot of carbon and we’re not really using it and it costs a lot of money and we don’t really have enough money to maintain it… Surely we can, as a smart organisation, find better ways to utilise space? And there’s always been a pushback and, I have to say, largely from academics, about why we possibly couldn’t do it any other way because it’s the way they’ve always done it!”[Interview—Director, Estates & Capital Projects, UCLan]

This highlights the value of organisations taking a reflective and nuanced approach to ‘recovery’, harnessing the positives of remote working and space rationalisation in ways that address decarbonisation, climate change and sustainability whilst meeting the needs of employers, customers and employees.

In relation to local housing, the concern was to promote wellbeing and sustainability, with energy efficiency and insulation for new builds and retrofits being highlighted as essential in tackling both the climate emergency and fuel poverty. While cost was a key concern, there was also optimism about the opportunity to prioritise skills development and invest in worker-owned cooperatives (a key feature of the Preston Model):

“We’re very keen on working with CGA, as a start, to look at retrofitting of properties and, potentially, it would that be good for… worker-owned companies to do that, [to] really push the boundaries of Preston Council.”[Interview—Leader, Preston City Council]

“One of our objectives…is to make our homes more energy efficient… So, we’re in the throws right now of assessing, what does post-2024 look like and, in reality, what does climate change, carbon neutral by 2050 look like?… We know, indicatively, it’s going to be a very big deal and a very expensive deal but… we’re not in this alone.”[Focus Group—Executive Team and Board Members, Community Gateway Association]

Participants highlighted the unique opportunity presented by the pandemic to embed a lasting shift in mindsets geared towards building a different and better future. While some were not convinced that the pandemic would be significant in mobilising climate action, others felt strongly that the glimpses of what might be possible could and should help change thinking to accelerate urgent transformative systemic change. Although not everyone made a connection between the experience of the pandemic and the potential this offered to think creatively about a different future, others highlighted the ‘once in a lifetime’ opportunity it presented and the urgent need for organisations to harness their learning from responding to the COVID-19 crisis so as to be better equipped to respond to the longer-term climate and ecological emergencies:

“I think it’s changed the way people are. I think it’s changed the way they think and that’s an immense opportunity around health, wellbeing, families, sustainability, education, communication…Even though I would never have wished for this horrible, terrible experience, I think that it can be transformational in a positive way going forward.”[Interview—Chief Information & Infrastructure Officer, UCLan]

There was a strong sense that the disruptive experience of COVID-19 offers enormous potential for anchor institutions to alter organisational working practices to deliver services more sustainably:

“I mean I think it would be almost criminal if we didn’t look to change things as a result, because if we can’t learn from a worldwide pandemic that’s lasted eighteen months and still isn’t finished, then I’m not sure what it would take for us to learn and change.”[Focus Group—Officers, PCC #1]

Reflecting on individual and community action, a member of Climate Action Preston argued that one key factor in the ability to foster change is a community’s ability to access information and take collective action rather than feeling isolated and helpless:

“One of the things is about this awareness… [It’s] about people knowing what they can do…Because people generally are hearing… ‘there’s a climate emergency’, but then because it feels…so big, where do you start? What can you do as an individual, as a community, as a city?”[Focus Group—Climate Action Preston]

Counter to the focus on positively embedding a radical shift in mindsets that prioritises climate action, some participants expressed scepticism and disappointment about the gap between rhetoric and reality:

“I think the challenge now, as we come out of the pandemic…is that this government is focused very much on getting back to business as usual, even with the rhetoric [of] let’s build back better, it’s really, let’s build back the same…let’s go back to how we were.”[Focus Group—UCLan #4]

There were also concerns that organisations’ focus on ensuring a rapid ‘return’ and ‘recovery’ to normal would mean that people will not continue to invest in local communities in ways developed during the pandemic and that they will not have the opportunities needed to draw on their experience to consolidate positive changes:

“I feel rather sceptical that actually some big lessons and so on will follow, not only because of the ‘back to normal’ but also because I don’t think people will give themselves the mental space and time to really reflect and think about what we’ll learn and what will change.”[Focus Group—UCLan #2]

In talking about ‘building back better’, participants identified the potential for embedding enduring changes in working practices as key to ensuring long-term commitment to climate action and carbon reduction. While noting the importance of a nuanced approach that takes account of the needs of different organisations, different roles and indeed different individuals in those roles, participants highlighted the increased use of technology to facilitate remote/hybrid working linked to increased levels of trust that challenge assumptions about ‘productivity’ and ‘presenteeism’:

“I don’t think that we’re going to go back to doing everything face-to-face. I think we will still use some of those online tools to do things that are a little bit different and…wider reaching.”[Focus Group—Climate Action Preston]

“What everybody’s learnt from COVID…was that some of our people…could do an amazing job and you’ll never see them. So, it’s built up…a level of trust in others and in themselves, and it has also broken down some myths about the fact that you’ve got to be present to perform.”[Interview—Chief Information & Infrastructure Officer, UCLan]

Through all of this, glimpses of a possible new future, characterised by a reduction in traffic and noise, reduced emissions and increased nature connectivity, were viewed as important catalysts for integrating long-term changes to working practices:

“If people can do their jobs without travelling [and] using carbon fuels, then I think it’s got to be done, as long as they’re equally productive… So, I think… [hybrid] working is going to be one or two days a week in the office, instead of five, unless you really, really have to be in for some reason. So, I think it would be massively good for the environment.”[Interview—Deputy Leader, PCC]

We now discuss these findings and articulate the numerous interconnected perspectives and aspects that permeated and emerged from the findings.

4. Discussion

The findings revealed multiple perspectives related to anchor institutions’ strategic priorities, ‘building back better’ and future implications for Preston. Whilst diverse issues emerged, we discuss key interconnected aspects that permeated the findings: wellbeing, tackling societal inequalities, collaborative working, and COVID-19 as a springboard for transformative change.

4.1. Wellbeing

It is perhaps unsurprising that wellbeing was a primary consideration and cross-cutting focus for both institutional and community stakeholders. While the physical health impacts of COVID-19 were most immediate, mental health consequences have been multifarious and far-reaching [34,35], with both mediated by social wellbeing—the impacts of containment measures strongly influenced patterns of interaction and connection. Wellbeing was a key focus in discussions concerning anchor institutions’ strategic plans, with a strong appreciation that wellbeing determinants are wide-ranging. Connections were made to inclusion, fairness, social value and sustainability, with income, food security, education, employment, housing, green space and building design all being highlighted. Reflecting on opportunities to change future approaches, wellbeing was understood to be central to the Preston Model’s CWB approach and to Doughnut Economics. This focus on ‘wellbeing economies’ has been prominent in commentaries exploring notions of ‘building back better and fairer’, with Büchs et al. [36] (p. 4) arguing that recovery from COVID-19 must prioritise “human health, wellbeing and ecological stability”.

4.2. Tackling Societal Inequalities

It is apparent that the pandemic has revealed and amplified entrenched social, economic and political inequalities. Marmot et al. [37] argue that the experiences of COVID-19 must be viewed in relation to pre-existing patterns of inequality and disadvantage, noting that those people and places struggling pre-pandemic have been most negatively impacted and face the greatest risks of entrenched poverty and disadvantage into the future. This is echoed by Lambert et al. [2] (e312), who note that COVID-19 “highlighted fault lines in societal structures that perpetuate ethnic, economic, social, and gender inequalities”. It is also apparent that without an explicit commitment to tackling long-standing inequalities and injustices, the long-term societal-level impacts of COVID-19 are likely to further exacerbate them [38].

Closely entwined with its focus on wellbeing, CWB was seen to signal a robust commitment to tackling disadvantage and pursuing social justice—against the backdrop of financial constraints and national-level policy that seems to work against local aspirations. Since the data collection period, HM Government [39] launched its ‘Levelling Up’ programme, aimed at spreading opportunity more equally across the UK. It is noteworthy that the National Audit Office has simultaneously published a report scrutinising the decisions and policies of the Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities [40], criticising the lack of an evidence-informed approach regarding the impact of public spending on past interventions [41]. The focus on tackling health and associated societal inequalities when ‘building back better’ echoed calls for a ‘just transition’, which involves an “ambitious social and economic restructuring that addresses the roots of inequality” [42] (p. 9). Since the summer of 2022, spiralling energy bills and increasing concerns about fuel poverty, heightened further by the war in Ukraine, have exacerbated the cost-of-living crisis in the UK and served to strengthen the importance of such thinking [43].

4.3. Collaborative Working

In both business and political spheres, researchers found a refreshed commitment to collaborative working, reflecting a shift from competition to co-operation. Reflecting a sense of positivity, hope, ambition and aspiration for a better future based on participants’ experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, these observations concur with research examining local government pandemic responses:

“The far-reaching impacts of the pandemic have meant that local responses have required the involvement of not just official government bodies, but also organizations in all segments of society…not just between different public service providers alongside long-established voluntary sector bodies, but also drawing in a myriad of neighbourhood mutual aid groups, concerned local businesses and members of the general public.”[44] (p. i.)

While reflections were often couched in strategic ‘performance’ terms, there was a sense that such collaboration has broader potential to build and consolidate relationships, catalysed by new perspectives emerging through the pandemic and associated restrictions. For some, these shifts were viewed as opportunities for ‘radical’ change in cross-sector working, indicating more progressive perspectives not usually found in large public sector institutions. Whereas competition is the norm for businesses, the movement towards collaboration was remarked upon as an extraordinary achievement for the greater good. Similarly, local councillors welcomed the fact that COVID-19 had served as a stimulus for them to work together across political boundaries, perceived to be a significant step. Just as the norm of ‘competition’ in business was disrupted, so was the norm of ‘political rivalry’ based on ideology and party membership. Furthermore, this shift towards co-operation was seen to go beyond politics, with reflections on ‘clap for carers’ pointing to a new-found humanity in and rekindling of relationships. A similar perspective was evident in the voluntary sector, with the pandemic reinforcing an organisational commitment to co-operative working and revealing a sense of hope and ambition going forward.

This new-found collaborative spirit and broadened sense of agency and empowerment resonates with reflections of Morgan et al. [45] regarding the collaborative ‘connected community approach’, and of South et al. [46] (p. 307), who argue that “a collaborative approach to rebuilding community health, wealth and wellbeing will be needed” during the COVID-19 pandemic recovery, such that “the ambition of a more community-centred system” can be realised. Instead of a central figure/group/authority being expected to take on the full burden of community-level responsibility, it was noted that community and voluntary groups were willing to participate as a societal collective, with co-operation becoming an accepted part of working for the common good. It was noteworthy that whereas organisations already experienced in group relations and inter-personal dynamics (such as the housing association and some voluntary sector bodies) expressed a strong desire to learn from the experience and strengthen future collaboration, others seemed more fearful that relationship enhancements could be transient, with cohesiveness only possible during crises. This collaborative culture is pertinent to how Preston prioritises a ‘wellbeing economy’ [36] in the future and develops a place-based approach to addressing climate and ecological emergencies. As Yuille, Tyfield and Willis [47] (p. 4) note, “a collaborative and aligned approach is needed both within councils (between officers and politicians, different departments and political parties) and with wider stakeholders”.

4.4. COVID-19 as a Springboard for Transformative Change

The final cross-cutting focus highlights the recognition that the pandemic, whilst unprecedented, damaging and traumatic, presents a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ opportunity for transformative change. Participants’ concern to ‘seize the moment’ echoed wider thinking about the opportunity:

“Like all crises, the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to be a catalyst for positive change precisely because it is so disruptive a shock to our economic and political systems, there is also the possibility that COVID-19 will help accelerate the emergence of...profound market shifts with exponentially positive consequences for people and planet.”[48] (p. 4)

The government restrictions to mobility and physical social contact served to reveal an alternative to simply ‘returning to the old normal’, highlighting the potential and widespread appetite for systemic change. However, it was also apparent that organisational stakeholders, while generally endorsing the need to prioritise the climate and ecological emergencies, were often sceptical about the possibility of ‘making this happen’ in the context of intensifying financial constraints and uncertainty of the appropriate strategic and operational response. At the community level, it was clear that awareness and prioritisation of climate change and environmental issues was variable, perhaps reflecting the immediacy of other concerns.

These findings reflect a widespread appreciation that, alongside the pain, suffering, injustice and predicted long-term damage, COVID-19 has offered glimpses of what a new and different world might look like. Across the globe, lockdowns have been associated with new patterns of working and learning, and with plummeting air travel, reduced motor traffic, renewed interest in cycling and walking, enhanced air quality, decreased carbon emissions and engagement with the natural environment [3]. These glimpses clearly offer significant potential for the disruption caused to serve as a catalyst to the sort of truly transformative recovery necessary to ‘build back’ better. There was also a sense from participants that CWB and the Preston Model [18] provide important opportunities to help frame and steer this recovery in ways that tackle inequalities and galvanise climate action. This is a process that some thought would be further strengthened through closer engagement with Doughnut Economics [21,49], with its dual focus on meeting human needs and respecting planetary boundaries.

Place-based climate action, CWB and Doughnut Economics have all considered the implications of and sought to respond to COVID-19, with the consequence that engagement with the three approaches has been enhanced by the pandemic. A group of local government, environmental and research organisations has proposed a blueprint for how the Government can use the pandemic to accelerate climate action at the local level and ensure that recovery from COVID-19 is truly ‘green’ [50]. CLES [51] has called for local government to take an integrated approach to economic, social and environmental justice and for a reimagining of how local economies can prioritise wellbeing over economic growth, advocating the use of CWB in building back better, fairer and greener from the pandemic [52,53,54]. Stratford and O’Neill [55] (p. 9) have considered how Doughnut Economics can guide post-pandemic recovery, arguing that “we need to focus our efforts on building a wellbeing economy—an economy that meets human needs and improves quality of life, without destabilising the Earth systems upon which we depend”. Elsewhere, the Wellbeing Economy Alliance has proposed 10 principles for recovery based on the Doughnut framework [36].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

In this paper, we have presented findings from the ‘Climate Resilience, Social Justice & COVID-19 Recovery in Preston’ project, exploring two themes that emerged from data collected during interviews and focus groups: Anchor Institutions’ Strategic Priorities and Plans (with sub-themes related to quality of life; sustainability and climate action; CWB; partnerships; and a focus on the long-term); and Building Back Better and its Future Implications for Preston (with sub-themes related to fairness and social justice; the built environment; shifting mindsets; rhetoric versus reality; and embedding enduring changes in working practices). Reflecting on these themes, it was evident that four key aspects permeated the findings—wellbeing, tackling inequalities, collaborative working and COVID-19 as a springboard for transformative change.

The evidence on climate and ecological emergencies highlights the urgency of implementing a comprehensive place-based approach supported by organisational and community-level plans. To seize the unique opportunity presented by COVID-19, we must combine a cross-sector strategic vision for transformative systems-level change with tangible actions that visibly harness learning and accelerate progress in tackling the interrelated challenges posed by the climate emergency, ecological crisis and societal inequality.

The paper has some obvious limitations. First, the research was conducted in one medium-sized city in England, and it cannot be assumed that findings and learning will automatically be transferable elsewhere. Second, while the initial study design included a combination of online and face-to-face interviews, focus groups and participatory stakeholder dialogue events, the longevity of the pandemic and accompanying restrictions on mobility and interaction meant that face-to-face data collection could not take place and the stakeholder events were unable to be transferred online. Consequently, it proved particularly challenging to access the voices of community stakeholders.

The findings and the interwoven aspects do, however, reveal some important inter-connected implications for anchor institutions and other organisations as they grapple with the scale and complexity of future challenges post-COVID-19 and consider what type of future we want, what needs to happen to enable this future and what is possible within financial and other contextual constraints. As a result, we propose four key recommendations for local stakeholders, institutions and policymakers, which respond to several of our original research questions, namely 3 and 4. Our full response to all four research questions is detailed in our full project report [56].

Firstly, we recommend using the momentum and disruption associated with the COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity to embed a commitment to equitable and inclusive climate action within and between organisations. This is likely to involve organisations and partnerships in two constructive and progressive forms. Firstly, by moving beyond the declaration of a climate and ecological emergency to develop a comprehensive action plan with ambitious SMART targets assessed according to previously agreed criteria and approved by a steering group duly convened for the purpose. Secondly, by prioritising a deliberative democratic process, such as a climate assembly or citizen’s jury [57], which informs action planning and can hold anchor institutions to account.

Secondly, we recommend consolidating the co-operative approach developed during the pandemic at strategic, operational and grassroots levels. Building on existing inter-organisation working will require three avenues of progression. The first is to establish an overarching cross-sector partnership able to accelerate action on the climate and ecological emergencies. This should potentially be modelled on the P-CAN climate commissions developed in Leeds, Edinburgh and Belfast or integrated within a previously established collaboration. Although there will inevitably be challenging questions about leadership and governance, a formally established partnership model should be adopted or created with a clear remit for acting on the climate emergency and moving beyond governmental rhetoric [58]. The second is the identification of tangible opportunities to collaborate across sectors to progress decarbonisation, increase carbon literacy and test innovative solutions facilitating a just transition. This might draw on specific expertise and learning generated in one particular anchor institution and put in place mechanisms to share and apply this more widely or use the proposed partnership to generate and incubate new cross-cutting ideas in areas such as transport, food, technology and nature-based solutions. The third is the provision of support, both financial and practical, to enable the grassroots collaborative culture catalysed by the pandemic to endure and strengthen.

Thirdly, we recommend taking a nuanced but radical approach to future work policies and practices. In the first instance, this will require appreciating that workplaces and organisations are diverse and that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach. It is then required to harness the positives of virtual technology for carbon reduction and wellbeing [59,60], and its wider potential for reducing travel, space utilisation and energy use. Throughout, we suggest that it will also require actors to be ambitious and to implement ‘win-win’ blended solutions that prioritise decarbonisation while acknowledging meeting the diverse needs of employers, clients and employees.

Finally, we recommend working collaboratively across anchor institutions to advocate collectively for supportive national-level policy by lobbying Members of Parliament and stakeholder organisations to work towards building a wellbeing economy and facilitate place-based action to tackle the climate and ecological emergencies. To be effective, this will most likely require a combination of non-partisan approaches, which will appeal in different ways to different organisations, trade unions, politicians and activists. This includes agreeing on common concerns, calling on the Government to provide increased financial support and remove unhelpful regulatory barriers and engaging with citizen- and community-led activism for change by including communities and organisations in strategic planning at every level. To move forward creatively and effectively, it will be essential for organisations to practice boundary-spanning leadership, which opens up possibilities for innovation and new types of collaboration. Defined as “the capability to establish direction, alignment, and commitment across boundaries in service of a higher vision or goal” [61] (p. 4), this reflects three priorities: collaboration across functions, empowerment of employees at all levels, and cross-organisational learning.

In concluding, it is pertinent to draw on insights from the Rapid Review [32] conducted alongside the empirical study. This proposed ‘Doughnut-Shaped Community Wealth Building’ as an appropriate place-based approach to tackle the dual crises posed by the climate and ecological emergencies and growing societal inequalities in the wake of COVID-19. In the context of Preston, this builds on existing strengths and organisational priorities, offering a disruptive approach to enable a ‘bounce forward’ into new ways of thinking and doing. By collaborating on such an approach and seizing this moment, organisations and citizens have enormous potential to trail-blaze and reap benefits for people, places and the planet.

Author Contributions

This study was contributed by several authors. The authorship represents the main contributors to the reported work. Authors contributed to the following components of the study: Conceptualisation and Methodology, M.D., A.F., I.M.C.-P., J.W. and J.M.; Data Gathering and Curation, M.D., A.F. and I.M.C.-P.; Validation, J.W. and J.M.; Formal analysis, A.F., I.M.C.-P. and M.D.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.F., I.M.C.-P. and M.D.; Writing—review and editing, I.M.C.-P., A.F., M.D., J.W. and J.M.; Project Oversight, J.W. and J.M.; Project Administration, M.D., A.F. and I.M.C.-P.; Funding acquisition, M.D. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through the Place-Based Climate Action Network (P-CAN), with regards to grant number ES/S008381/1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Central Lancashire.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative datasets utilised in this article are not readily available due to ethical and privacy restrictions. Requests to access our community researcher training materials should be directed to Alan Farrier.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the Place-Based Climate Action Network (P-CAN) with additional support from the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan)’s Institute of Citizenship, Society & Change and Centre for Sustainable Transitions. Thank you to Rachel Stringfellow (Preston City Council), Claire Smith (Community Gateway Association) and Julie Ridley (UCLan) for their support and guidance on the project’s Oversight Group. Finally, thank you to all the study’s participants and Community Researchers who supported the research team.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- WHO. COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) Global Research and Innovation Forum. Geneva: World Health Organisation. 11–12 February 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Lambert, H.; Gupte, J.; Fletcher, H.; Hammond, L.; Lowe, N.; Pelling, M.; Raina, N.; Shahid, T.; Shanks, K. COVID-19 as a global challenge: Towards an inclusive and sustainable future. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, E312–E314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de León, E.A.; Shriwise, A.; Tomson, G.; Morton, S.; Lemos, D.S.; Menne, B.; Dooris, M. Beyond building back better: Imagining a future for human and planetary health. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e827–e839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WWF—World Wildlife Fund for Nature. COVID 19: Urgent Call to Protect People and Nature; World Wildlife Fund for Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/4783129/WWF%20COVID19%20URGENT%20CALL%20TO%20PROTECT%20PEOPLE%20AND%20NATURE.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change; Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Stripple, J.; Bulkeley, H. Towards a material politics of socio-technical transitions: Navigating decarbonisation pathways in Malmö. Political Geogr. 2019, 72, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggah, R. Look to Cities, Not Nation-States, To Solve Our Biggest Challenges. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/cities-mayors-not-nation-states-challenges-climate/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Sharif, M.; Cities: A ‘Cause of and Solution To’ Climate Change. United Nations News. 2019. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/09/1046662 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- PCAN. About PCAN [Place-Based Climate Action Network]. 2021. Available online: https://pcancities.org.uk/about (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Manley, J.; Whyman, P. (Eds.) The Preston Model and CWB: Creating a Socio-Economic Democracy for the Future; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M.; Howard, T. The Making of a Democratic Economy; Berrett-Koehler: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; Jones, R. Paint Your Town Red: How Preston Took Back Control and Your Town Can Too; Repeater: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Partington, R.; ‘Preston Named as Most Improved City in the UK’. The Guardian. 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/nov/01/preston-named-as-most-most-improved-city-in-uk#:~:text=Research%20carried%20out%20by%20the,most%20in%20its%202018%20Good (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- DEMOS-PwC. Good Growth for Cities: The Local Economic Impact of COVID-19; PWC: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.pwc.co.uk/industries/government-public-sector/good-growth/2021.html (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- DEMOS-PwC. Good Growth for Cities: Taking Action on Levelling Up; PWC: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.pwc.co.uk/government-public-sector/good-growth/assets/pdf/good-growth-2022.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- PCC. CWB 2.0: Leading Resilience and Recovery in Preston; Preston City Council: Preston, UK, 2021. Available online: https://www.preston.gov.uk/media/5367/Community-Wealth-Building-2-0-Leading-Resilience-and-Recovery-in-Preston-Strategy/pdf/CommWealth-ShowcaseDoc_web.pdf?m=637498454035670000&ccp=true#cookie-consent-prompt (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- PCC. Resolution to Declare a Climate Emergency. In Minutes of Council Meeting Held on 18th April; Preston City Council: Preston, UK, 2019; Available online: https://preston.moderngov.co.uk/documents/g5641/Printed%20minutes%2018th-Apr-2019%2014.00%20Council.pdf?T=1 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Thompson, M. What’s so new about New Municipalism? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Penguin Random House: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, J.; Rockström, S.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL). The Amsterdam City Doughnut: A Tool for Transformative Action. Amsterdam: DEAL with Circle Economy, C40 Cities and Biomimicry 3.8. 2020. Available online: https://www.kateraworth.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/20200406-AMS-portrait-EN-Single-page-web-420x210mm.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Nugent, C.; Amsterdam Is Embracing a Radical New Economic Theory to Help Save the Environment. Could It Also Replace Capitalism? Time, 22 January 2021. Available online: https://time.com/5930093/amsterdam-doughnut-economics/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Kokko, S.; Baybutt, M. (Eds.) Handbook of Settings-Based Health Promotion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, J.; Gordon, P.; Plamping, D. Working Whole Systems: Putting Theory into Practice in Organisations; King’s Fund: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, Z. The Essential Guide to Doing Research; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, M.; Dooris, M.; Barry, J. Place-Based Climate Action, Community Wealth Building and Doughnut Economics: A Rapid Review (May 2022). PCAN Cities. 2022. Available online: https://pcancities.org.uk/sites/default/files/RapidReview%20FINAL_0.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Lancashire Enterprise Partnership. Social Value Toolkit. 2023. Available online: https://lancashirelep.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/social-value-toolkit-002.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R.; Wetherall, K.; Cleare, S.; McClelland, H.; Melson, A.J.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; O’Carroll, R.E.; O’Connor, D.B.; Platt, S.; Scowcroft, E.; et al. Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 218, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büchs, M.; Baltruszewicz, M.; Bohnenberger, K.; Busch, J.; Dyke, J.; Elf, P.; Fanning, A.; Fritz, M.; Garvey, A.; Hardt, L.; et al. Wellbeing Economics for the COVID-19 Recovery. Ten Principles to Build Back Better (May 2020). Global: Wellbeing Economy Alliance. 2020. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Wellbeing_Economics_for_the_COVID-19_recovery_10Principles.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Boyce, T.; Goldblatt, P.; Morrison, J. Health Equity in England. The Marmot Review 10 Years On (February 2020); Institute of Health Equity, The Health Foundation: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Bambra, C.; Riordan, R.; Ford, J.; Matthews, F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HM Government. Levelling Up the United Kingdom; Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-the-united-kingdom (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Davies, G. Supporting Local Economic Growth: Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities; National Audit Office: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Supporting-local-economic-growth.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- National Audit Office. Supporting Local Economic Growth: Press Release (2nd February). 2022. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/press-release/supporting-local-economic-growth/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Pinker, A. Just Transitions: A Comparative Perspective; A Report Prepared for the Just Transition Commission; James Hutton Institute: Aberdeen, UK, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/independent-report/2020/08/transitions-comparative-perspective2/documents/transitions-comparative-perspective/transitions-comparative-perspective/govscot:document/transitions-comparative-perspective.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- ONS. Energy Prices and Their Effect on Households (1st February). Office for National Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/articles/energypricesandtheireffectonhouseholds/2022-02-01 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Gore, T.; Bimpson, E.; Dobson, J.; Parkes, S. Local Government Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK: A Thematic Review; Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University: Sheffield, UK, 2021; Available online: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/29300/1/local-government-responses-to-COVID.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Morgan, G.; Poland, B.; Jackson, S.; Gloger, A.; Luca, S.; Lach, N.; Rolston, I.A. A connected community response to COVID-19 in Toronto. Glob. Health Promot. 2021, 29, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, J.; Stansfield, J.; Amlot, J.; Weston, D. Sustaining and Strengthening Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Perspect. Public Health 2020, 140, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuille, A.; Tyfield, D.; Willis, R. Enabling Rapid Climate Action. The Experience of Local Decision-Makers; PCAN: Lancaster, UK, 2021; Available online: https://pcancities.org.uk/sites/default/files/Briefing_Enabling%20Rapid%20Climate%20Action%20The%20Experience%20of%20Local%20Decision-Makers.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development. The Consequences of COVID-19 for the Decade Ahead. Vision 2050 Issue Brief (7 May). 2020. Available online: https://docs.wbcsd.org/2020/05/WBCSD_V2050IB_COVID19.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Fanning, A.L.; Krestyaninova, O.; Raworth, K.; Dwyer, J.; Hagerman Miller, N.; Eriksson, F. Creating City Portraits: A Methodological Guide from the Thriving Cities Initiative. 2020. Available online: https://doughnuteconomics.org/Creating-City-Portraits-Methodology.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- ADEPT; Ashden; Friends of the Earth; Grantham Institute; Greenpeace UK; LEDNet; PCAN; Solace. A Blueprint for Accelerating Climate Action and a Green Recovery at the Local Level. 2021. Available online: https://www.adeptnet.org.uk/news-events/climate-change-hub/blueprint-accelerating-climate-action-and-green-recovery-local-level#:~:text=Together%2C%20we%20published%20a%20Blueprint,together%20with%20communities%20and%20businesses (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- CLES. Owning the Economy; CWB 2020; CLES (Centre for Local Economic Strategies): Manchester, UK, 2020; Available online: https://cles.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Community-Wealth-Building-2020-final-version.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- CLES. Rescue, Recover, Reform. A Framework for New Local Economic Practice in the Era of COVID-19; CLES (Centre for Local Economic Strategies): Manchester, UK, 2020; Available online: https://cles.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Rescue-recover-reform-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- CLES. Own the Future. A Guide for New Local Economies; CLES (Centre for Local Economic Strategies): Manchester, UK, 2020; Available online: https://cles.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Own-the-future-revised-mutuals-copy.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Leibowitz, J. A Green Recovery for Local Economies; CLES: Manchester, UK, 2020; Available online: https://cles.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Green-Recovery-FINAL2.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Stratford, B.; O’Neill, D. The UK’s Path to a Doughnut-Shaped Recovery; University of Leeds: Leeds, UK, 2020; Available online: https://goodlife.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2020/11/doughnut-shaped-recovery-report.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Charnley-Parry, I.; Farrier, A.; Dooris, M.; Manley, J.; Whitton, J.; Drake, M.; Turda, M. Climate Resilience, Social Justice & COVID-19 Recovery in Preston: Final Report (May 2022). PCAN Cities. 2022. Available online: https://pcancities.org.uk/sites/default/files/PCAN%20Final%20Report%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Wells, R.; Howarth, C.; Brand-Correa, L.I. Are citizen juries and assemblies on climate change driving democratic climate policymaking? An exploration of two case studies in the UK. Clim. Chang. 2021, 168, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, C.; Lane, M.; Fankhauser, S. What next for local government climate emergency declarations? The gap between rhetoric and action. Clim. Chang. 2021, 167, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houlihan Wiberg, A.; Løvhaug, S.; Mathisen, M.; Tschoerner, B.; Resch, E.; Erdt, M.; Prasolova-Førland, E. Advanced visualization of neighborhood carbon metrics using virtual reality: Improving stakeholder engagement. In Handbook of Smart Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–33. Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-030-15145-4_64-1 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Fauville, G.; Queiroz, A.C.M.; Bailenson, J.N. Virtual reality as a promising tool to promote climate change awareness. In Technology and Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, J.; Ernst, C.; Campbell, M. Boundary Spanning Leadership: Mission Critical Perspectives from the Executive Suite; Center for Creative Leadership Organizational Leadership White Paper Series; Center for Creative Leadership: Greensboro, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).