Abstract

In contributing towards the discourse on developing teachers’ capabilities for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), this study examines the relationships between sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy for teaching sustainability concepts among vocational teachers in Malaysian colleges. Grounded in Bandura’s self-efficacy theory, the research assesses the combined effect of teachers’ sustainability knowledge and readiness on their ability to teach sustainability effectively. Using a cross-sectional survey design, a sample of three hundred and seventy-five (375) vocational college teachers and structural equation modeling (SEM), the results indicate no significant link between teachers’ sustainability knowledge and their readiness for ESD. However, a positive relationship between teachers’ readiness and their self-efficacy was found. The study shows that while sustainability knowledge does not directly enhance readiness for ESD, it is a strong predictor of self-efficacy in teaching sustainability. Moreover, readiness has a greater effect on self-efficacy than sustainability knowledge alone, highlighting the importance of conceptual understanding in building teachers’ confidence and competence in sustainability education. Despite focusing specifically on Malaysia and using self-reported data, which to some extent limits the study’s findings, the outcomes offer practical insights for educational policymakers, vocational institutions, and educators. They underscore the need for a comprehensive educational approach beyond just knowledge transfer. This research contributes to the sustainability education discourse and suggests areas for future studies, including exploring contextual differences and adopting longitudinal study designs to better understand the dynamics between sustainability knowledge, readiness, and teaching self-efficacy in vocational education.

1. Introduction

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) stands as an imperative in today’s educational landscape, addressing the urgent need to equip individuals with the knowledge, skills, and values essential for a sustainable future [1,2]. As ESD continues to gain recognition, educators find themselves facing fundamental questions such as “What should we teach about sustainable development?” and “How might we approach teaching for sustainability, especially within the context of technical and vocational education?” These questions become even more complex when considering the varying levels of awareness and understanding of sustainability concepts among educators, as well as the extent of ESD integration within the vocational education curricula [3,4]. This predicament begs a critical question: Why do vocational teachers struggle with effectively teaching and integrating sustainability concepts within their respective subjects? Some scholars have attempted to provide answers to these pertinent questions [5,6,7,8]. For instance, Sharma [9] explained that vocational educators in New Zealand held perceptions of ESD being of little relevance to trade and vocational education and as such were less interested in sustainability issues, which in turn resulted in these educators affirming that their perception and knowledge of sustainability issues was minimal. Therefore, could inadequate or lower knowledge of sustainability issues affect teachers’ readiness and self-efficacy to engage in ESD?

This study, therefore, is founded upon the assumption that the answer to the question of how teachers might approach teaching sustainability in a TVE context may in part be found in understanding the interplay of vocational teachers’ sustainability knowledge, readiness, and teaching efficacy [7,10,11]. While the quality of teacher training programs plays a pivotal role in this context, examining teachers’ self-efficacy and readiness to teach sustainability provides an indirect lens through which we can explore their preparedness for this critical task. Vocational teachers’ awareness, sense of capacity, and confidence are reflected in their efficacy beliefs, and a substantial body of research literature has established a connection between teachers’ self-efficacy and their training as well as their teaching performance [2,12,13,14,15].

According to the Cloud Institute for Sustainable Education [10], Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is a learning process that aims to provide students, teachers, and school systems with the knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, and thinking needed to attain economic prosperity and responsible citizenship. Similarly, ref. [11] defines ESD as a learning process that provides individuals with the necessary knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes to make informed decisions and take responsible actions to ensure environmental integrity, economic viability, and social justice for current and future generations, while also respecting cultural diversity. ESD therefore aims to preserve and enhance the health of living systems to ensure the future welfare of humanity and the Earth.

Various educational fields across different countries are at distinctive levels of ESD integration despite over two decades of UNESCO calls for reorienting educational programs/systems to develop sustainability literacy. In a TVE context, the challenges are also evident as there are notable challenges within the implementation of ESD in Malaysia’s vocational education sector. For instance, the researchers in [4], using a quantitative case study, examined the prospects of the TVE program in Malaysia in preparing pre-service teachers for teaching sustainability concepts. Using a dual perspective analysis constituting TVE educators’ and students’ perspectives, they found that TVE programs currently do not adequately incorporate sustainability concepts. This backdrop inhibits the programs’ effectiveness in properly preparing teachers to perform educational tasks that advocate for and advance sustainability. Similarly, ref. [11] argued that to train workers who can carry out work by applying an understanding of sustainability principles, teachers and instructors must themselves become sustainability-literate vocational teachers. However, they highlighted that vocational teacher education programs were sufficiently vast in developing the technical aspects and competencies of vocational teachers but lagged sufficiently in developing sustainability-literate vocational teachers. These challenges underscore the need for this study.

Bandura defines self-efficacy as the belief in one’s capacity to plan and execute instructional objectives within a specific subject matter [12]. In the context of teaching, self-efficacy represents a teacher’s conviction in their ability to educate their students efficiently and effectively. While research literature [13,14,15] has explored the connection between self-efficacy and the broader teaching and learning process, the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and their effectiveness in teaching sustainability remains largely unknown.

Moreover, it is crucial to recognize that efficacy beliefs are not one-dimensional; they vary across different subject matters [12,16]. Thus, it would be an oversimplification to assume that teachers who generally possess self-efficacy would exhibit the same level of self-efficacy when teaching sustainability concepts. Consequently, this study aims to address this gap in the literature by investigating the association between vocational teachers’ self-efficacy, their knowledge, and their readiness within the specific context of ESD and TVE.

While previous studies have explored the impact of sustainability pedagogies on pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy for ESD [17], the broader understanding of self-efficacy in teaching sustainability remains substantially unexplored, especially in a TVE context. Research literature suggests that teachers’ self-efficacy for teaching sustainability may be influenced by the quality of teacher training programs or professional development courses to which teachers are exposed. Thus, this study seeks to examine the relationship between vocational teachers’ self-efficacy and their sustainability knowledge within the unique context of Malaysian vocational colleges.

In addition to self-efficacy, another critical factor influencing the quality and effectiveness of teaching and learning is teachers’ readiness [18,19,20,21]. Teacher readiness encompasses their willingness, confidence, capacity, attitudes, motivation, and intent to teach effectively. While perceived readiness has been theoretically linked to self-efficacy [22], a teacher’s ability to maintain an effective classroom environment is compromised if they do not feel adequately prepared. In educational contexts, teachers are more likely to engage successfully in teaching when they feel confident and competent. The case is also true about the relationship between self-efficacy and teachers’ readiness [12]. Teachers feel better prepared when they feel confident and competent in their abilities. Thus, teachers’ perception of their readiness to teach, and the quality of their training experience, may be fundamental to determining how confident and competent they feel in executing teaching tasks related to a specific subject matter, and in the specific context of sustainability education.

Although some studies have explored teachers’ knowledge of sustainability, self-efficacy, and readiness to teach sustainability concepts and issues [7,17,23,24], the literature remains relatively limited and inconclusive on the nature of the relationship between these variables, especially regarding an ESD context. This study therefore addresses this gap by providing a comprehensive examination of vocational teachers’ knowledge of sustainability, their readiness, and self-efficacy levels in teaching sustainability. The extent to which self-efficacy, sustainability knowledge, and readiness are reflected in teaching performance is pivotal to the quality of the educational process, particularly concerning sustainability education. This study aims to contribute to stakeholders’ understanding of in-service vocational teachers’ self-efficacy, sustainability knowledge, and readiness in the context of teaching sustainability in Malaysian vocational colleges. By doing so, it seeks to provide valuable insights that can be used to enhance the quality and effectiveness of teacher training and professional development programs, ultimately fostering the development of self-efficacious teachers who can engage learners effectively in meaningful sustainability education. With the foregoing, the following research questions were formulated to guide the study:

- What is the level of sustainability knowledge among teachers in vocational colleges?

- What is the level of vocational college teachers’ readiness in terms of teaching sustainable concepts?

- What is the self-efficacy level of vocational college teachers with respect to sustainability education?

- What is the relationship between vocational college teachers’ sustainability knowledge and their self-efficacy in teaching sustainability?

- What is the effect of vocational teachers’ sustainability knowledge and readiness for teaching sustainability concepts on their self-efficacy for sustainability teaching?

1.1. Research Framework and Hypothesis Development

This study’s conceptual framework is rooted in Albert Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), which posits that an individual’s self-efficacy, or belief in their ability to succeed in a specific task, is shaped by personal experiences, social and cultural factors, as well as observational learning. According to Bandura [16], individuals can enhance their self-efficacy through various means, such as expanding their skills and knowledge, receiving feedback and encouragement, and observing others who excel in the same task [16].

In an educational context, SCT suggests that teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, influenced by their knowledge and preparedness [25,26], play a pivotal role in their motivation, behavior, and performance. Teachers tend to feel more confident and capable when equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively teach a subject or implement a specific educational approach [16]. Additionally, their experiences and interactions with the teaching environment, including support programs and technological infrastructure, also contribute to shaping their self-efficacy beliefs [27]. Consequently, the theory proposes an interconnected relationship between teachers’ knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy within the teaching and learning process.

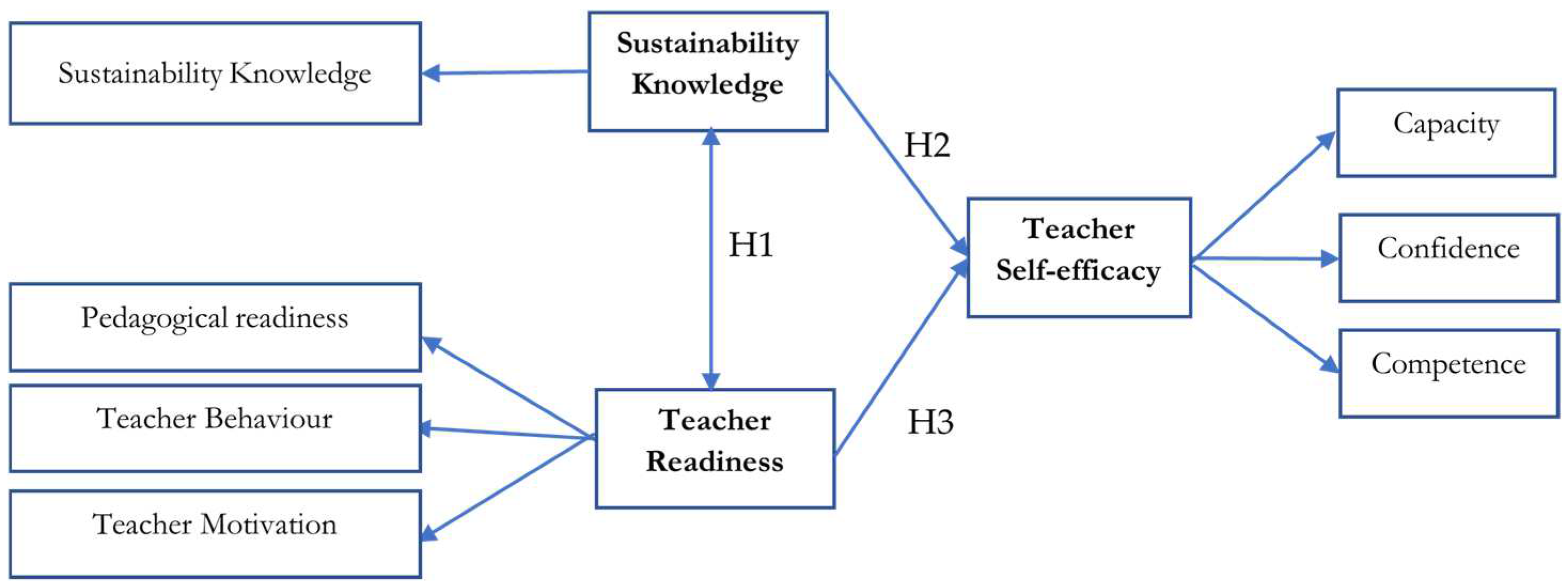

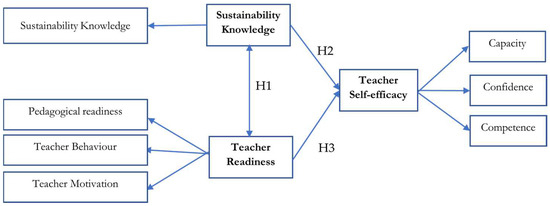

While the extant literature extensively links self-efficacy to the general teaching and learning process [13,14,21,28], research on the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and sustainability teaching is developing rapidly. Ashton and Webb [29] argue that efficacy beliefs are not unidimensional, i.e., they vary across different subject matters. Therefore, assuming a homogeneous relationship exists between teachers’ self-efficacy and their readiness to teach specific subjects, such as ESD, would be misleading. Therefore, SCT provides a theoretical foundation to examine whether vocational teachers’ sustainability knowledge influences their readiness and self-efficacy beliefs in teaching ESD content. Additionally, this study also examines whether the combined effect of vocational teachers’ knowledge and readiness affects their self-efficacy in teaching sustainability concepts and issues across vocational colleges in Malaysia. Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework of the study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study.

1.1.1. Teachers’ Sustainability Knowledge and ESD Readiness

The relationship between teachers’ sustainability knowledge and their readiness in the context of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is an intricate but critical dynamic that significantly shapes the efficacy of sustainability education initiatives [30]. The ability to effectively engage in ESD lies in the foundational knowledge possessed by educators. UNESCO [30] has stressed that teachers equipped with a robust understanding of sustainability concepts are better prepared to integrate these multifaceted ideas into their pedagogical endeavors. The depth of knowledge about the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability not only empowers teachers but also equips them with the requisite content expertise to effectively convey these intricate concepts to their students [31,32,33]. Sustainability knowledge exerts a profound influence on teachers’ pedagogical practices. Studies by Wals [34] and Walshe [35] assert that educators well-versed in sustainability are more inclined to adopt experiential and inquiry-based teaching methods, which may demonstrate content and pedagogical preparedness in navigating the complex and multifaceted ESD landscape. Teachers’ readiness reflects how well-prepared they are for delivering a specific subject matter. In the context of this study, sustainability knowledge or ESD knowledge is defined as vocational college teachers’ conceptual understanding of sustainability across social, environmental, and economic dimensions, and their content and pedagogical knowledge which they have acquired through training or experience.

The relationship between teachers’ sustainability knowledge and readiness extends beyond the mere articulation of information or facts. An understanding of this contextual relationship will be pivotal in shaping educators’ willingness and ability to adapt their teaching practices to incorporate sustainability concepts. Tilbury [36] suggests that educators with a comprehensive understanding of sustainability not only recognize the importance of ESD but also exhibit a readiness to adapt their curriculum and instructional methods in consonance with the principles of sustainable development.

Drawing insights from pertinent literature, some scholars have suggested that teachers’ knowledge of sustainability issues and concepts may influence their level of preparedness to engage in ESD adequately. For instance, Vukelic [21] examined the link between teachers’ readiness to implement ESD and their exposure to the initial teachers’ training program. They found that teachers’ initial training influenced their level of preparedness for ESD. More specifically, the authors [21] found that pre-service teachers in the field of the natural sciences expressed more intent to implement ESD to a lesser extent compared to students from other fields (humanities, arts, and social sciences), implying that the programs exposing students to sustainability concepts tended to correlate with pre-service teachers’ readiness in ESD. Similarly, the authors in [37] suggest that teachers need specific knowledge and abilities to develop and implement education for sustainable development (ESD). Eliyawati et al. [38] also emphasized the need for science teachers to integrate ESD teaching competencies with their science teaching competencies. In a dissimilar context, Mulyadi et al. [39] found that teachers’ perceptions of their ESD competence were positively correlated with the implementation of ESD in schools. Given these dynamics in the association of teachers’ knowledge of ESD and their preparedness to engage in ESD, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a positive and significant relationship between vocational teachers’ sustainability knowledge and their readiness for sustainability teaching.

1.1.2. Teachers’ Sustainability Knowledge and Self-Efficacy in ESD

Bandura’s conception of self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to plan and implement instructional objectives within a specific subject matter [13]. In an educational context, self-efficacy is defined as a teacher’s conviction in their ability to educate their students efficiently and effectively. Within the domain of ESD and specifically within this study, vocational teachers’ self-efficacy is an outcome variable representing a teacher’s capacity, competence, and confidence in their ability to successfully plan and execute courses of action required to attain instructional objectives regarding ESD.

Prior research literature has linked teachers’ knowledge and self-efficacy in ESD. For instance, Evans [17] examined the impact of sustainability pedagogies on pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy for ESD using a quasi-experimental, pre–post design. The author found that there was an increase in students’ observed ESD efficacy after being exposed to teaching methodologies that adopted sustainability pedagogies. Ref. [40] found that professional development training programs significantly increase teachers’ knowledge and self-efficacy. Similarly, Ref. [2] found that pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy, perceived content knowledge, and perceived pedagogical knowledge regarding ESD were adequately enhanced through teaching practicum experiences. In addition, a study [26] also found that long-term professional development programs that provide opportunities for teachers to experiment with ESD principles and challenges can boost their self-efficacy and lead to the implementation of ESD practices in the classroom. Given that prior studies have associated some dynamic where teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs are influenced by avenues for knowledge building and development, the following can thus be hypothesized:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Vocational college teachers’ sustainability knowledge positively and significantly influences their self-efficacy for sustainability teaching.

1.1.3. Teachers’ Readiness and Self-Efficacy in ESD

The quality and efficacy of the teaching and learning process are significantly influenced by teachers’ perceived preparedness (readiness) in managing their subject matter. According to Giallo et al. [22], teachers’ readiness is associated with their self-efficacy and is crucial for maintaining an effective classroom environment [41]. The same can also be said of the impact of teachers’ self-efficacy and readiness. However, the bidirectional (reciprocal) relationship between the teacher’s efficacy and readiness will not be examined in this study given the limitations of the partial least squares structural equation modeling in estimating bidirectional relationships. However, it can be assumed that as teachers’ readiness influences their self-efficacy in ESD, teachers’ self-efficacy can also impact their ESD readiness. Housego [41] further notes that a teacher’s success in the teaching and learning process is diminished when they lack the readiness to teach. Readiness, as defined by Baker [42], encompasses various aspects such as willingness, confidence, capacity, attitudes, motivation, and intent to teach. Therefore, in the context of this study, vocational teachers’ readiness for sustainability teaching is a predictor variable reflecting a teacher’s perception of how prepared they are, their attitudes, motivations, and willingness to engage in Education for Sustainable Development. Vukelic [21] found that pre-service teachers’ readiness to implement ESD is closely correlated with their self-efficacy in ESD. The author [21] further explained that female pre-service teachers tend to express greater intention to implement ESD, while age was negatively correlated with the extent to which pre-service teachers express their intention to implement ESD. Vukelic’s study shed light on the nuances in teachers’ readiness to implement ESD when viewed from the lens of socio-demographic factors such as gender, age, and their effect on teachers’ self-efficacy. While studies have suggested a link between teachers’ readiness and their self-efficacy [7,17,21], research directly examining this relationship within an ESD context is lacking, especially within vocational education. Given that teachers’ readiness and self-efficacy are contingent on several factors including the context and subject matter, it is crucial to examine how the former affects the latter in an ESD context. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Vocational teachers’ readiness in sustainability teaching positively and significantly affects their self-efficacy in sustainability teaching.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of vocational teachers’ sustainability knowledge and readiness in sustainability teaching on their self-efficacy in sustainability teaching. Hence, a cross-sectional survey was used. A cross-sectional survey research method was used because it afforded the researchers the flexibility to collect data from in-service vocational college teachers at a single point in time, on their perceived self-efficacy and readiness in sustainability teaching [43].

2.2. Sample, Sampling Approach, and Demography of Respondents

The target population for the study were vocational college teachers in Malaysia. Given that the researchers were interested in examining the dynamics between teachers’ sustainability knowledge, their readiness, and their self-efficacy in sustainability teaching within the ambit of vocational education, vocational college teachers were considered the most appropriate population for the study. According to Malaysia’s Ministry of Education, there are 87 vocational colleges across the country. Hence, given the need for a representative and adequate sample, Krejcie and Morgan’s [44] sample size table was used to determine the sample size for the study. Hence, a total of 375 vocational college teachers were selected using a cluster sampling method for the study. Cluster sampling was used because vocational colleges in Malaysia are categorized into geographical zones, namely, northern, eastern, central, southern, and eastern zones. Hence six colleges were strategically chosen from the respective zones to collect data for this study. Participants were randomly selected across these zones to reflect an approximately representative sample.

Table 1 shows the demographic profile of respondents in this study. A sample of three hundred and sixty vocational college teachers participated in the study. Table 1 shows the gender distribution, location of institutions, age distribution, highest degree obtained, and teaching experience of vocational college teachers across the study’s location. Table 1 also indicates that there was a mixed representation of vocational teachers in terms of gender, with both male and female vocational college teachers participating in the study. In terms of the location of the institutions, most respondents (79.4%) are affiliated with vocational colleges located in more urban-centric locations. Similarly, the age distribution of respondents, as shown in Table 1, indicates that the largest cohort of teachers in vocational colleges falls within the 41–50 years age range, constituting 28.9% of the sample. This suggests a significant presence of mid-career vocational college teachers in the study. Additionally, the 20–30 years and 31–40 years age groups show substantial representation, adding to a diverse age profile of respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of respondents (n = 360).

In analyzing the highest degrees attained by vocational college teachers, Table 1 reveals that the majority (92.2%) hold bachelor’s degrees. Comparatively, a smaller percentage possess master’s degrees (5.0%), with only a minimal presence of teachers holding diplomas (2.8%). Examining the teaching experience of vocational college teachers in this study, Table 1 highlights the 5–10 years teaching experience category as the most prominent, encompassing 37.2% of the sample. This indicates a significant representation of teachers at mid-career and early career stages. Additionally, the <5 years category represents approximately 33.1% of the sample. Vocational teachers with 11–15 years of experience (12.2%) and >15 years of experience (17.5%) add to a balanced distribution, enhancing diversity within the sample. The demographic profile reflects a heterogeneous group of vocational college teachers, with a significant representation of mid-early career professionals holding bachelor’s degrees. This nuanced understanding of the sample’s characteristics is crucial for contextualizing and interpreting the subsequent findings related to the interplay between sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy in teaching sustainability concepts.

2.3. Instrument and Measures

The instrument for data collection was a researcher-designed questionnaire consisting of four sections including a demographic section and three scales adapted from several studies [7,17,21,45]. Section A sought data on teachers’ demographic characteristics, including the institution’s location, gender, age, teaching experience, and highest degree obtained. Section B was a test consisting of 20 questions designed to assess participants’ knowledge of sustainability issues. Each correctly answered question scored a total of 5 marks. Section C sought participants’ self-report data on their teaching readiness comprising three sub-dimensions, namely, pedagogical readiness (e.g., I feel prepared to implement effective teaching strategies to teach sustainability principles), teacher behavior (e.g., I am confident in maintaining a positive and conducive classroom environment that facilitates ESD learning), and teacher motivation (e.g., I am motivated and enthusiastic about teaching sustainability concepts and issues in my lessons). Items in the readiness scales were structured on a 9-point Likert scale comprising 1 = Not at all ready and 9 = Extremely ready. Section D contains the teachers’ self-efficacy scale which sought data on teachers’ self-efficacy according to three sub-dimensions, namely, capacity to teach sustainability concepts (e.g., I feel confident in my ability to effectively teach sustainability concepts), competence (e.g., I am confident in my capability to convey sustainability concepts accurately), and competence (e.g., I perceive myself as highly competent in delivering sustainability content). Items in this scale were structured on a 9-point Likert comprising 1 = Not at all confident, and 9 = Extremely confident. To modify the instrument, the process included selecting items from the original questionnaires and customizing them based on dimensions identified through a thorough literature review and by the operational definition of the constructs. The items, although adapted from previous studies [7,17,46], were pre-validated and pilot-tested with thirty vocational teachers who were not part of the sample for the study. This was done to ensure that the instrument measures what was intended by the researchers. Upon internal consistency checks, Cronbach alpha values of 0.772, 0.971, and 0.976 were obtained for the knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy scales, respectively, indicating the high reliability of the measures.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize and describe participants’ demographic data. Descriptive statistics were also used to interpret the level of vocational college teachers’ sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy for sustainability teaching as shown in Table 2. The remark convention iterated in Table 2 is a consistent practice in social science research when transforming scales of varying dimensions, as reported in [47]. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to test the hypothesized relationships between the exogenous and endogenous constructs and determine the strength of the relationship [48].

Table 2.

Mean score interpretation.

3. Results

3.1. Teachers’ Sustainability Knowledge Levels

Table 3 shows the sustainability knowledge levels of vocational college teachers in Peninsular Malaysia. We found that most vocational teachers have substantial knowledge of sustainability issues, with about 65 percent of the sample scoring between 68–100% on the sustainability knowledge test, indicating a somewhat balanced understanding of sustainability concepts and their dimensions. A good number of vocational college teachers (26.4%) show an adequate level of sustainability knowledge, scoring between 34–67% on the sustainability knowledge scale, while a modest amount (8.6%) show a minimal sustainability knowledge level, scoring between 0–33%. With a mean score of 67.7 and a standard deviation of 19, the results reflect that a vast majority of vocational college teachers in Malaysia have moderate to high knowledge of sustainability issues and related concepts.

Table 3.

Vocational college teachers’ sustainability knowledge levels.

The disparities in the levels of sustainability knowledge among vocational college teachers are indicative of the necessity for targeted interventions aimed at developing competencies and capabilities for resolving complex sustainability issues. These interventions should capitalize on and leverage the most experienced teachers who possess a higher level of sustainability knowledge to spearhead them, thus enhancing sustainability education within the vocational context.

3.2. Teachers’ Readiness Levels in Sustainability Teaching

In assessing vocational college teachers’ readiness levels for teaching sustainability concepts and related issues, we found that vocational teachers exhibit a particularly substantial and significant level of readiness in terms of teacher behavior (M = 6.41, SD = 1.45) and teaching motivation (M = 6.52, SD = 1.57) dimensions, while showing an adequate (M = 6.27, SD = 1.50) readiness level in terms of pedagogical readiness (See Table 4). While vocational teachers, in sum, show a substantial level of readiness (M = 6.36, SD = 1.25), it will be beneficial to further enhance their preparedness in terms of ESD pedagogies, instructional methods, and strategies, contributing to an even more significant level of preparedness for ESD.

Table 4.

Vocational college teachers’ readiness levels in sustainability teaching.

3.3. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Levels in Sustainability Teaching

Regarding vocational college teachers’ self-efficacy levels in sustainability teaching, we found (see Table 5) that vocational teachers have an adequate to substantial level of perceived confidence (M = 6.32, SD = 1.40) and competence (M = 6.45, SD = 1.42) to teach sustainability concepts. While the capacity to teach sustainability concepts falls within the adequate range (M = 6.23, SD = 1.47), the overall self-efficacy level is deemed adequate (M = 6.33, SD = 1.24), indicating a collective belief in vocational teachers’ capacity to contribute significantly to sustainability education. This suggests that vocational college teachers perceive that they possess the capacity, confidence, and competence to engage in sustainability education and prepare students to become sustainability-literate across various vocations.

Table 5.

Vocational college teachers’ self-efficacy levels in sustainability teaching.

3.4. Assessing the Measurement and Structural Model

To estimate the associations between the exogenous and endogenous constructs as illustrated in the conceptual framework of the study (see Figure 1), the partial least squares structural equation modeling was used [49]. We sought to estimate the effect between teachers’ sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy in teaching sustainability concepts in the context of Malaysian vocational education. Three hypotheses (H1 to H3) were tested to draw inferences on the relationship between teachers’ sustainability knowledge, teachers’ readiness, and teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching sustainability concepts.

Hair [48] recommends a two-stage approach for analyzing the interactive effect between constructs in a complex model. Firstly, the reflective measurement model is assessed to establish convergent and discriminant validity. Secondly, the structural model is also assessed to estimate the relationship between the constructs. Assessing the structural model enables the researchers to ascertain the model’s fit in predicting the target constructs [48].

3.4.1. The Measurement Model

The measurement model evaluates the relationship between the latent constructs and their corresponding observed indicators. Three main criteria are used to assess the measurement model, namely, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity [50]. Internal consistency estimates the extent to which an indicator or set of indicators is consistent in measuring what it intends to measure. This is assessed using the composite reliability and Cronbach alpha coefficient [48]. Convergent validity, on the other hand, is used to estimate the extent to which individual indicators reflect a construct, i.e., the extent to which individual indicators converge to a specific construct in comparison to measuring other constructs. The indicator reliability, factor loadings and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) are used to specify convergent validity. Table 6 shows the factor loadings, Cronbach alpha coefficient, composite reliability (CR), and AVE of all constructs in the model. According to Hair [48], indicators and constructs with outer loadings greater than 0.708 and CR greater than 0.700 have achieved satisfactory reliability while convergent validity is established with an AVE of 0.500. As seen in Table 6, all constructs have factor loadings ranging between 0.795 and 0.946. Regarding the internal consistency, CR, and AVE of teachers’ self-efficacy and readiness scales, Table 6 shows that the values obtained were greater than the minimum threshold specified by Hair [48] and Ramayah et al. [50]. Given that the sustainability knowledge measure was an aggregate reflecting the knowledge score of respondents, it is a unidimensional construct and, as such, its loading is one; hence, Cronbach alpha and CR estimates do not apply to this scale since there are no underlying indicators or subdimensions for a test [48]. This establishes that the measures are satisfactorily reliable and valid.

Table 6.

Construct reliability and convergent validity.

To determine discriminant validity, the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) was used. Discriminant validity refers to the extent to which indicators measure distinct concepts by examining the correlation between measures of potentially overlapping indicators [50]. In sum, discriminant validity indicates the extent to which constructs in a model are truly distinct from one another. Traditional measures of discriminant validity such as Fornell and Larcker’s criterion are adjudged to be flawed, given that this criterion is too conservative and may not identify a lack of discriminant validity [48]. Hence, the HTMT criterion, being a direct comparison of correlations, is argued to be more sensitive in detecting potential issues with discriminant validity. Hence, the HTMT ratio was used to determine discriminant validity. Table 7 shows the HTMT ratio values. Henseler [51] and Kline [52] recommend that HTMT values of 0.85 and 0.90 establish discriminant validity. As shown in Table 7, all HTMT values meet the stringent HTMT criteria of 0.85, thus indicating that the three constructs in the model are truly distinct, and discriminant validity was achieved.

Table 7.

HTMT ratio.

3.4.2. The Structural Model

Before assessing the structural model, it is essential to verify that there are no lateral collinearity issues with the constructs, as this has the potential to distort causal effects within the model. To assess lateral collinearity in the model, inner VIF values are used. Hair [49] recommends that constructs with inner VIF values less than five signify that lateral multicollinearity is not an issue with the model. After assessing multi-collinearity issues, the structural model can hence be assessed. Table 8 shows the structural model.

Table 8.

Multi-collinearity assessment using the inner VIF.

The structural model estimates the strength of interactive effects among the constructs specified in the three hypotheses (H1–H3), employing measures such as the path coefficient (β), variance explained (R2), and effect size (f2).

Table 8 indicates that the inner VIF values for all the constructs are below the recommended threshold of five, as recommended by Hair [49]. This signifies that multi-collinearity is not an issue in the model.

The bootstrapping function in SmartPLS 4.0 using 5000 separate samples was used to assess the structural model to determine the significance of the hypothesized relationships between the constructs. The results in Table 9 show that teachers’ sustainability knowledge does not significantly affect teachers’ readiness for sustainability teaching (β = 0.063, p = 0.096, t-statistic = 1.304). Ramayah et al. [50] note that hypotheses are significant and accepted when the t-statistic is greater than 1.645, and the p-value is less than 0.05; since the p-value and t-statistic for H1 here exceed this threshold, H1 is unsupported. Similarly, the results in Table 9 indicate that sustainability knowledge positively and significantly affects vocational teachers’ self-efficacy for sustainability teaching (β = 0.183, p = 0.000, t-statistic = 4.208), indicating that the hypothesis H2 is supported by the model. Vocational college teachers’ sustainability knowledge explains about 18.3% of the variance in teachers’ self-efficacy for sustainability teaching. In addition, the results also show that vocational college teachers’ readiness positively and significantly influences teachers’ self-efficacy in sustainability teaching (β = 0.564, p = 0.000, t-statistic = 1.304), with about 56.4% of the variance in teachers’ self-efficacy for sustainability teaching explained by vocational teachers’ readiness. Thus, the hypothesis H3 is supported by the model.

Table 9.

Hypothesis testing.

3.4.3. Predictive Relevance (Q2) and Effect Size (f2)

The effect size of the exogenous constructs was determined by examining the f2 values shown in Table 10. According to Hair [48], it is crucial to measure the effect size to determine the strength of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. According to Cohen [53], effect sizes of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively. The results show that vocational teachers’ sustainability knowledge with an effect size of 0.053 has a small effect on vocational teachers’ self-efficacy in sustainability teaching. Conversely, vocational college teachers’ readiness with an effect size of 0.498 has a large effect on vocational college teachers’ self-efficacy for sustainability education in Malaysian vocational colleges. This implies that a teacher’s readiness and preparedness to engage in sustainability education contributes more to their perceived efficacy in teaching sustainability concepts than simply developing knowledge of sustainability issues and concepts. Furthermore, in examining the predictive accuracy and explanatory power of the model through the coefficient of determination (R2), the results in Table 10 illustrate that the variance in vocational college teachers’ self-efficacy for sustainability teaching is explicable by 36.4% of the combined effect of teachers’ sustainability knowledge and readiness for sustainability teaching, as indicated by an R2 value of 0.364. Cohen [53] confirms that a model achieving an R2 greater than 0.20 demonstrates substantial explanatory accuracy. Furthermore, Q2 values exceeding zero suggest the adequate predictive relevance of the model. In this context, the Q2 value of 0.356 indicates that the exogenous constructs possess significant predictive relevance for the endogenous constructs.

Table 10.

Predictive relevance and effect size.

4. Discussion

The examination of sustainability knowledge among vocational college teachers in Malaysian vocational colleges, as illustrated in Table 3, indicates a commendable level of understanding regarding sustainability education, with 65% of participants scoring between 68–100%. Nevertheless, disparities exist, emphasizing the necessity for targeted interventions. Leveraging the expertise of those with higher knowledge levels can contribute to equitable distribution and enhance sustainability education within the vocational context. The findings also revealed that vocational teachers exhibit substantial readiness in behavior, motivation, and pedagogical aspects. While the overall readiness of vocational college teachers is significant, a focus on refining vocational teachers’ preparedness in ESD pedagogies and instructional strategies is necessitated to further enhance their readiness for ESD. Regarding vocational teachers’ self-efficacy in sustainability teaching, the findings indicate that vocational college teachers perceive that they have substantial levels of confidence and competence. Similarly, vocational college teachers perceived their capacity for sustainability teaching (ESD) was adequate. Overall, the aggregate score signifies a collective belief in teachers’ ability, confidence, and competence to significantly contribute to sustainability education. the findings unveil the nuanced landscape of sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy among vocational college teachers in Malaysia. The results provide a foundation for targeted interventions, emphasizing the importance of leveraging existing expertise and refining specific areas to enhance sustainability education within vocational settings. These results are consistent with the assertions of UNESCO [30], as teachers who are equipped with a vivid understanding of sustainability concepts are better prepared to integrate these multifaceted ideas into their pedagogical endeavors. The depth of knowledge about the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability not only empowers teachers but also equips them with the requisite expertise to effectively convey these complex concepts to their students [31,32,33].

The study also sought to determine the associations between vocational teachers’ sustainability knowledge, readiness for sustainability teaching, and self-efficacy in sustainability teaching. To assess the interactive effect among these variables, three hypotheses were tested using the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis. Table 9 provides critical insights into the complex relationships between teachers’ sustainability knowledge, readiness for sustainability teaching, and self-efficacy. The finding that sustainability knowledge has no significant effect on vocational teachers’ readiness contradicts the initial hypothesis (H1) and calls into question established literature. Irrespective of this, the idea that an educator’s foundational knowledge, as emphasized by UNESCO [30] and echoed in the works of Wals [34] and Walshe [35], does not directly affect teachers’ preparedness brings an interesting dynamic to the discourse. This finding contradicts previous research, which found a positive relationship between knowledge of sustainability concepts and preparedness for ESD. Vukelic’s [21] study, for example, found that exposure to sustainability concepts during initial training influenced teachers’ readiness for ESD. This could be the result of a myriad of factors. Firstly, sustainability knowledge is multifaceted, encompassing social, environmental, and economic dimensions. Bandura [16] posits that individuals learn through observation, imitation, and modeling. Teachers may require more specific and targeted training on integrating sustainability concepts into pedagogical practices that go beyond general knowledge and awareness of sustainability issues. In addition, knowledge is an individual-level construct that varies from person to person and is contingent on environmental and contextual factors, training, experience, and so on. These intervening variables may affect the relationship between vocational teachers’ knowledge of sustainability and their readiness to engage in ESD.

Another possible explanation for this research outcome may be the contextual variations in knowledge. The study focused on vocational teachers in Malaysian vocational colleges. Hence, contextual variations may influence the relationship between sustainability knowledge and readiness [16]. Cultural, institutional, or contextual differences may impact how sustainability knowledge translates into practical readiness. SCT emphasizes the role of social and environmental factors in shaping behavior, and these contextual elements may play a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of sustainability knowledge in promoting teachers’ readiness. In addition, Bandura also highlighted the interaction between personal factors, behavior, and the environment. This is because such factors, such as institutional support, collaborative learning environments, or specific teaching methodologies, may need to interact with sustainability knowledge to affect teachers’ readiness for sustainability teaching [16]. This study did not account for these factors, hence the outcome.

In contrast, the positive and significant influence of sustainability knowledge on vocational college teachers’ self-efficacy (H2) is consistent with previous research. The findings are consistent with Evans [17] and Ref. [40], indicating that exposure to sustainability pedagogies improves teachers’ self-efficacy, and the same may be true for the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and readiness. A teacher’s belief in their capacity to execute ESD teaching tasks efficiently may also inform their level of preparedness to execute said teaching activities. This consistency with existing literature lends credibility to the study’s findings. In a similar vein, the findings revealed a positive and significant influence of teachers’ readiness on their self-efficacy (H3). This research outcome corroborates the research literature’s emphasis on the integral role of teacher readiness in fostering an effective learning environment [21]. However, the substantial effect size of readiness compared to sustainability knowledge raises critical questions about the relative importance of these factors. The large effect size of readiness (0.498) in comparison to the small effect size of sustainability knowledge (0.053) implies that teachers’ preparedness holds more explanatory power over their perceived efficacy in teaching sustainability concepts. This challenges the conventional notion that knowledge forms the bedrock of effective teaching [7,17,21,22]. However, Bandura [16] asserts that self-efficacy is influenced by mastery experiences, social modeling, social persuasion, and physiological factors. Readiness, reflecting a teacher’s confidence, capacity, and motivation, may have a more direct effect on self-efficacy than knowledge alone. This may be because teachers perceive their ability to enact sustainability education more strongly through preparedness rather than developing a theoretical and conceptual understanding of the concept or phenomenon alone.

Furthermore, the coefficient of determination (R2) and predictive relevance (Q2) provide valuable insights into the explanatory and predictive power of the model. The R2 value of 0.364 indicates that 36.4% of the variance in vocational college teachers’ self-efficacy is explained by the combined effect of sustainability knowledge and readiness. While this surpasses Cohen’s threshold for substantial explanatory accuracy [53,54], it underscores the complexity of factors influencing teachers’ self-efficacy in sustainability teaching. The unexplained variance indicates that teachers’ self-efficacy in sustainability instruction is influenced not only by sustainability knowledge and preparation but also by other key factors such as personal views, previous experiences, institutional backing, or other environmental elements. The large Q2 value (0.356) further reinforces the model’s predictive relevance. A Q2 score of 0.356 (or 35.6%) in this context indicates that the model can predict 35.6% of the variance in teachers’ self-efficacy for sustainability education. This strongly suggests that the model is both theoretically sound and practically applicable. Additionally, the proximity of the Q2 value to the R2 value obtained is noteworthy. It suggests that the model is not only explaining a significant portion of the current variation but is also effective at predicting self-efficacy in similar samples. In predictive modeling, a high Q2 value is as important as a high R² value because it ensures that the model’s conclusions are not only fit to the sample data but also generalizable to other populations. Given the study’s outcomes, it is pertinent to also regress and discuss the findings in line with the demography of respondents.

The study’s results, framed in the diverse demographic context of vocational college teachers in Malaysia, provide a detailed framework for comprehending the dynamics of sustainability education. The diverse demographic profile, including the age profile, educational background, and teaching experiences, demonstrates the complex nature of vocational education environments. This diversity offers valuable insights into the nuances of the educational ecosystem and how it can impact the implementation and success of sustainability education. The level of sustainability knowledge among the teachers, as indicated in the study, is a positive note. However, the existence of disparities in this knowledge underscores a vital aspect: the need for nuanced, targeted interventions in sustainability education that consider the diverse demographic backgrounds of the teachers. The demographic data suggest that these interventions may need to be tailored differently across various age groups, educational levels, and years of teaching experience to be effective. The demographic backdrop of this study—particularly the significant representation of mid-career professionals—also suggests that while experience and maturity might contribute positively to self-efficacy, they do not necessarily correlate with readiness to teach sustainability concepts, hinting at possible gaps in initial teacher training or ongoing professional development. Furthermore, the challenge to the convention that knowledge directly increases preparedness for sustainability teaching, revealed in the study, gains an additional layer of complexity when viewed through the demographic lens. The varied educational and experiential backgrounds of the teachers suggest that personal, institutional, and contextual factors may significantly influence this relationship. It implies that enhancing sustainability education in vocational settings may require more than just imparting knowledge; it may necessitate addressing broader systemic and contextual factors that impact teachers’ readiness and self-efficacy.

5. Implications of the Study

5.1. Implications for the Malaysian Ministry of Education

The study’s outcomes highlight the need for Malaysia’s Ministry of Education to strategically improve sustainability education in vocational teacher training programs. A critical implication is the need to review and adapt the current curriculum to explicitly incorporate sustainability components. This adaptation should not only focus on theoretical knowledge but also on practical aspects that help teachers prepare for sustainability teaching. Furthermore, the Ministry should consider launching targeted professional development initiatives for vocational teachers. These programs should go beyond knowledge acquisition, focusing on teacher readiness and pedagogical strategies that align with sustainability concepts. Incentive structures or recognition programs for educators who demonstrate substantial levels of sustainability knowledge and readiness could encourage more active participation in sustainability education within vocational education.

5.2. Implications for Vocational Institutions

Vocational institutions, as leaders in TVET, should align their curricula with sustainability-related content and principles. We recommend that courses should explicitly integrate sustainability concepts to ensure a balance of theoretical knowledge and practical readiness for effective teaching. Faculty development programs that focus on improving sustainability knowledge, readiness, and motivation are critical. Creating collaborative opportunities between vocational institutions and external organizations can help to enhance knowledge and promote best practices in ESD.

5.3. Implications for Theory and Research

The study advances theoretical understanding, necessitating an extension of Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory in the context of sustainability education to reflect the nuances in the dynamics of antecedent factors influencing teachers’ readiness and self-efficacy for sustainability teaching. The importance of readiness in translating knowledge into effective teaching practices should be further investigated. Future research can examine how contextual factors influence the relationships between sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy. Understanding how cultural and institutional contexts influence these dynamics will enhance theoretical frameworks. Furthermore, longitudinal studies that examine the evolution of teachers’ sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy over time can reveal important insights into the dynamic nature of these relationships.

5.4. Implications for Practice

Practitioners directly involved in sustainability education should adopt a balanced approach to professional development. Engaging in activities that enhance both sustainability knowledge and readiness ensures a holistic preparation for effective teaching. Collaborative learning communities within and across vocational institutions offer platforms for knowledge sharing and the implementation of innovative practices in sustainability education.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

While the study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of sustainability education among vocational college teachers, it has some limitations. One major constraint is the generalizability of the findings. The study focuses solely on vocational colleges in Malaysia, so caution should be exercised when extrapolating the findings to other educational contexts or cultural settings. Educational systems, institutional structures, and cultural influences differ significantly across regions, with potentially different outcomes. Another consideration is the reliance on self-report measures, which raises the possibility of response bias. Participants may have been inclined to provide socially desirable responses, particularly when self-reporting their sustainability readiness and self-efficacy. This bias has the potential to influence data accuracy, emphasizing the need for more objective measures or observational methods to validate self-reported information. The study’s scope is also limited by its focus on a narrow set of variables: sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy; this is because the investigators intended to simply juxtapose the influence of teachers’ sustainability knowledge and readiness on their self-efficacy from an ESD and general education perspective. We stated earlier that it would be an oversimplification to assume that because the research literature provides empirical evidence that teachers’ knowledge and readiness influence their self-efficacy and vice versa, hence the outcomes would be similar within an ESD context. Our findings have shed more light on the nuances in this simple but complex relationship. While these factors are undoubtedly important, other potential influences on the teaching of sustainability concepts have not been examined in this study. Institutional support, classroom resource availability, and specific teaching strategies may have a significant impact on the effectiveness of sustainability education, necessitating expanded research investigation. Furthermore, it is critical to acknowledge another limitation of the study, which is the adoption of a cross-sectional research design. Cross-sectional designs only enable data collection at one point in time, limiting the researcher’s ability to capture development or changes over time. This limitation may impact the depth of understanding regarding the dynamics between the study’s variables. Thus, while the current study offers valuable contributions, future research utilizing longitudinal designs could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing vocational college teachers’ preparedness in sustainability teaching over time.

7. Conclusions

The study investigated the relationships between sustainability knowledge, readiness, and self-efficacy among Malaysian vocational teachers. The findings emphasize the importance of not only having solid sustainability knowledge but also being adequately prepared and motivated to incorporate these concepts into teaching practices. The positive impact of readiness on self-efficacy emphasizes the importance of educators’ overall preparedness for effective sustainability education. The study contributes substantially to the ongoing discussion on sustainability education by highlighting these relationships. This research enhances our comprehension of some of the factors that influence educators’ preparedness for teaching sustainability concepts and highlights the wider implications for educational policy, vocational institutions, and professional development efforts. Utilizing the knowledge gained from this study in educational policies can assist in developing curricular frameworks that emphasize sustainability education and the specific elements that enable teachers to thrive in implementing ESD teaching activities. Vocational institutions can draw from these findings to create specific training programs to improve teachers’ knowledge and preparedness for sustainability, therefore promoting an optimum atmosphere for sustainable development efforts. Furthermore, professional development initiatives can be tailored to equip educators with the necessary tools and strategies to integrate sustainability principles seamlessly into their teaching practices. By doing so, these efforts can contribute to developing a generation of environmentally conscious individuals who are equipped to address the challenges of sustainability in their respective fields. Overall, the study’s implications extend beyond academia, offering actionable recommendations that have the potential to catalyze positive change and contribute to the attainment of sustainable development goals at both local and global levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y., C.C.C., W.C., A.S. and M.O.O.; Methodology, W.Y., C.C.C., W.C. and A.S.; Software, C.C.C.; Validation, C.C.C.; Formal analysis, C.C.C. and W.C.; Investigation, W.Y., C.C.C., W.C., A.S., M.O.O., D.R.Ñ.E. and B.V.B.; Data curation, M.O.O.; Writing—original draft, W.Y. and C.C.C.; Writing—review & editing, C.C.C., A.S., M.O.O., D.R.Ñ.E. and B.V.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

We adhered to the ethical standards established by the school/institution/university/Helsinki Declaration’s ethical guidelines, considering all pertinent requirements. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants, who willingly participated in the study. Participants were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time without any penalty. We commit to maintaining the confidentiality of participants’ data and details throughout the study and beyond.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Manasia, L.; Ianos, M.G.; Chicioreanu, T.D. Pre-Service Teacher Preparedness for Fostering Education for Sustainable Development: An Empirical Analysis of Central Dimensions of Teaching Readiness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousheen, A.; Zia, M.A.; Waseem, M. Exploring Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy, Content Knowledge, and Pedagogical Knowledge Concerning Education for Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 30, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinedu, C.C.; Azlinda, W.; Mohamed, W. A Document Analysis of the Visibility of Sustainability in TVE Teacher Education Programme: The Case of a Malaysian HEI. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2017, 25, 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Chinedu, C.C.; Wan Mohamed, W.A.; Ajah, A.O.; Tukur, Y.A. Prospects of a Technical and Vocational Education Program in Preparing Pre-Service Teachers for Sustainability: A Case Study of a TVE Program in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Curric. Perspect. 2019, 39, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrazak, S.R.; Ahmad, F.S. Sustainable Development: A Malaysian Perspective. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 164, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aminrad, Z.; Zakariya, S.; Hadi, A.S.; Sakari, M. Relationship between Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes towards Environmental Education among Secondary School Students in Malaysia. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 22, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar]

- Effeney, G.; Davis, J. Education for Sustainability: A Case Study of Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ Knowledge and Efficacy. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 38, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Monteiro, S. Creating Social Change: The Ultimate Goal of Education for Sustainability. Int. J. Social. Sci. Humanit. 2016, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. Education for Sustainability in Certificate and Vocational Education at a New Zealand Polytechnic. Master’s Thesis, Unitec Institute of Technolog, Auckland, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cloud Institute for Sustainable Education Education for Sustainability. Available online: http://cloudinstitute.org/brief-history/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Chinedu, C.C.; Saleem, A.; Wan Muda, W.H.N. Teaching and Learning Approaches: Curriculum Framework for Sustainability Literacy for Technical and Vocational Teacher Training Programmes in Malaysia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; ISBN 0470479213. [Google Scholar]

- Gavora, P. Slovak Pre-Service Teacher Self-Efficacy: Theoretical and Research Considerations. New Educ. Rev. 2010, 21, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tebbs, T.J. Assessing Teachers’ Self-Efficacy towards Teaching Thinking Skills. Unpublished. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Bijl, J.J.; Shortridge-Baggett, L.M. The Theory and Measurement of the Self-Efficacy Construct. Sch. Inq. Nurs. Pract. 2002, 15, 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1986; ISBN 013815614X. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N.; Tomas, L.; Woods, C. Impact of Sustainability Pedagogies on Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 10, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, C.; West, M. Pre-Service Teachers’ Perception and Beliefs of Readiness to Teach Mathematics. Curr. Issues Educ. 2011, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Görsev İnceçay, Y.K.D. Classroom Management, Self-Efficacy and Readiness of Turkish Pre-Service English Teachers. Int. Assoc. Res. Foreign Lang. Educ. Appl. Linguist. ELT Res. J. 2012, 1, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ozek Kaloti, Y. A Comparative Study Of The Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, And Readiness Of American Versus Turkish Language Teachers. J. Int. Educ. Res. (JIER) 2016, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukelić, N. Student Teachers’ Readiness to Implement Education for Sustainable Development. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallo, R.; Little, E. Classroom Behaviour Problems: The Relationship between Preparedness, Classroom Experiences, and Self-Efficacy in Graduate and Student Teachers. Aust. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 3, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, C.; Huss, J.; Utley, J. Assessing K–12 Teachers’ Personal Environmental Education Teaching Efficacy and Outcome Expectancy. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2010, 9, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, A.P. Preservice Elementary Teachers’ Perceived Efficacy in Teaching Environmental Education: A Preliminary Study; 1992. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED362487 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Handtke, K.; Richter-Beuschel, L.; Bögeholz, S. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD: A Theory-Driven Instrument and the Effectiveness of ESD in German Teacher Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T.; Gericke, N. Teachers’ ESD Self-Efficacy and Practices: A Longitudinal Study on the Impact of Teacher Professional Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Howard, S.K.; Tondeur, J. The More Experienced, the Better Prepared? New Evidence on the Relation between Teachers’ Experience and Their Readiness for Online Teaching and Learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogias, A.; Malandrakis, G.; Papadopoulou, P.; Gavrilakis, C. Self-Efficacy of In-Service Secondary School Teachers in Relation to Education for Sustainable Development: Preliminary Findings. In Contributions from Science Education Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, P.T.; Webb, R.B. Making a Difference: Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy and Student Achievement; Longman Publishing Group: London, UK, 1986; ISBN 0582284805. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation. UNESCO Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action. Programme on Education for Sustainable Development; United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson, P.; Hudges, P.; Layer, G. Education for Sustainable Development: Using the UNESCO Framework to Embed ESD in a Student Learning and Living Experience. Policy Pract. A Dev. Educ. Rev. 2008, 17–29. Available online: https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/sites/default/files/Issue6.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Pavlova, M. Two Pathways, One Destination–TVET for a Sustainable Future. In Proceedings of the Conference Report for the UNESCO-UNEVOC Virtual Conference, Virtual, 22 October–10 November 2007; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Toolkit, Learning & Training Tools; Section for Education for Sustainable Development (ED/UNP/ESD): Paris France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J. A Mid-DESD Review Key Findings and Ways Forward. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 3, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, N. Understanding Students’ Conceptions of Sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Environmental Education for Sustainability: Defining the New Focus of Environmental Education in the 1990s. Environ. Educ. Res 1995, 1, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceska, N.; Nikoloski, D. The Role of Teachers’ Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the International Balkan and Near Eastern Social Sciences Conference Serie (IBANESS), Ohrid, North Macedonia, 28–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eliyawati; Widodo, A.; Kaniawati, I.; Fujii, H. The Development and Validation of an Instrument for Assessing Science Teacher Competency to Teach ESD. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyadi, D.; Ali, M.; Ropo, E.; Dewi, L. Correlational Study: Teacher Perceptions and The Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development Competency for Junior High School Teachers. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 299-307, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, K.D.F. Professional Development: Improving Teachers’ Knowledge and Self-Efficacy Related to Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2022, 32, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housego, B.E. A Comparative Study of Student Teachers’ Feelings of Preparedness to Teach. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 1990, 36, 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P.H. The Role of Self-Efficacy in Teacher Readiness for Differentiating Discipline in Classroom Settings; Bowling Green State University: Bowling Green, OH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Educational Research. Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating, Quantitative and Qualitative. Anim. Genet. 2015, 39, 561–563. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, R.F.; Park, C.L.; Van Neste-Kenny, J.M.C.; Burton, P.; Qayyum, A. Using Self-Efficacy to Assess the Readiness of Nursing Educators and Students for Mobile Learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2012, 13, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahat, H.; Idrus, S. Education for Sustainable Development in Malaysia: A Study of Teacher and Student Awareness. Geogr. Malays. J. Soc. Space 2017, 12, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Obeidat, B.Y.; Al-Suradi, M.M.; Masa’deh, R.; Tarhini, A. The Impact of Knowledge Management on Innovation: An Empirical Study on Jordanian Consultancy Firms. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1214–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equations Modeling (PLS-SEM). J. Tour. Res. 2021, 6, 390. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah TJ, F.H.; Cheah, J.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using. In SmartPLS 3.0: Chapter 13: An Updated and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis; Pearson: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2017; ISBN 978-976-349-750-8. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J Acad Mark Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routedge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; Volume 55, ISBN 0415195411. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).