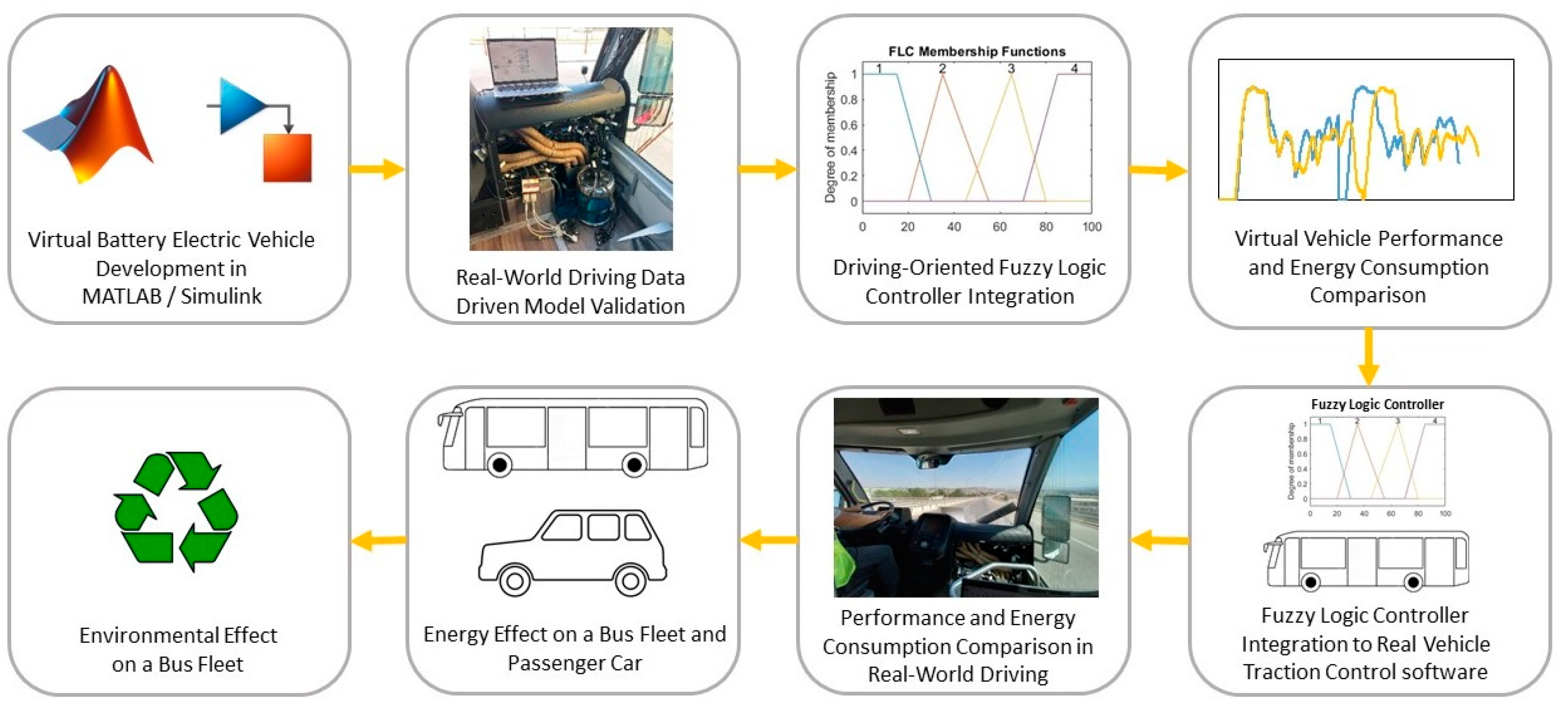

Sustainable Energy Management in Electric Vehicles Through a Fuzzy Logic-Based Strategy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- A successful FLC-based energy management system was designed in a single energy source EV architecture;

- The effectiveness of the developed strategy was strengthened by testing it on two different driving behaviors and both virtual and real vehicle models;

- The findings were evaluated and concretized on a real electric bus fleet;

- A comprehensive assessment is made by presenting energy management, cost, and environmental impacts together.

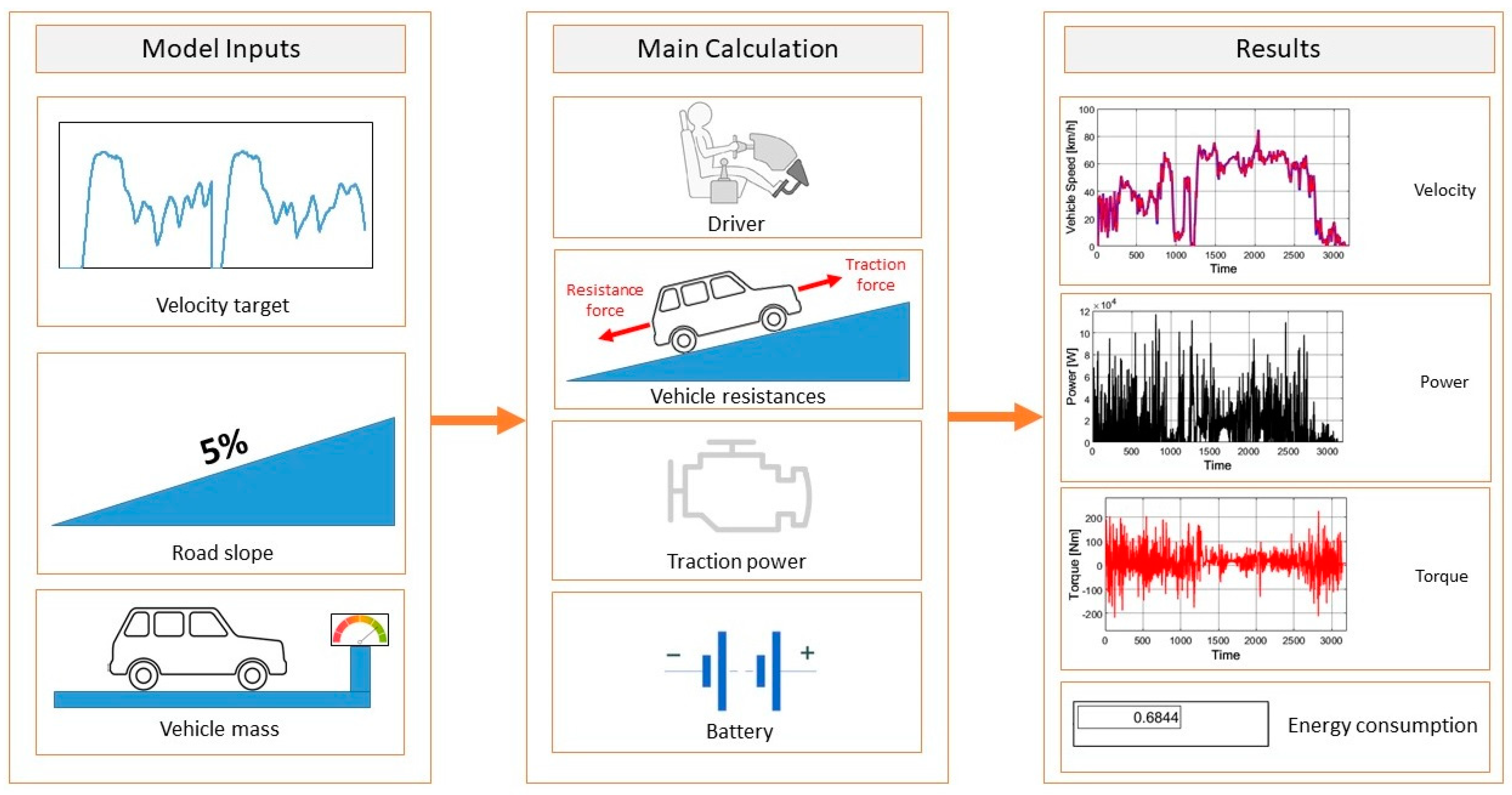

2. Materials and Methods

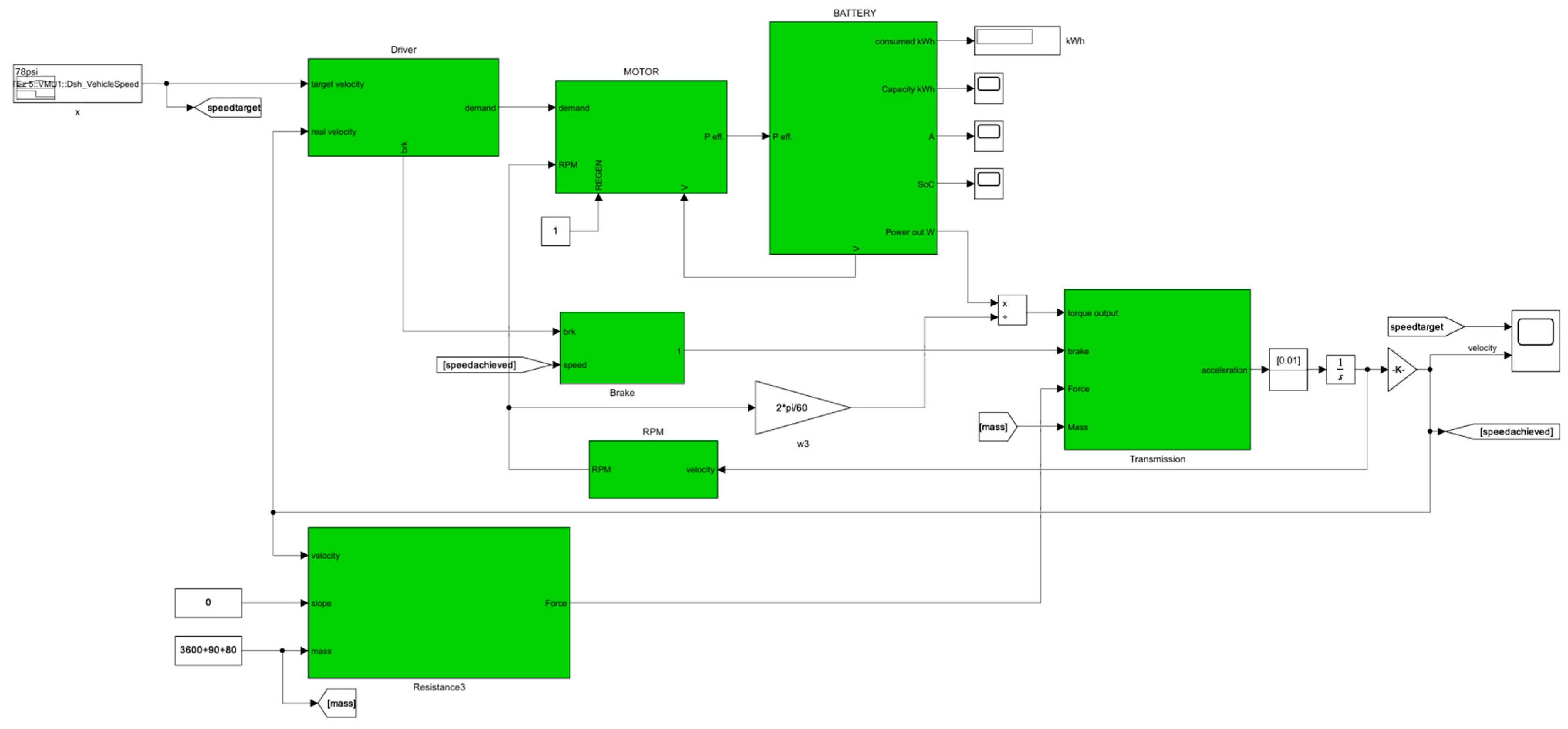

2.1. Virtual Battery EV Model

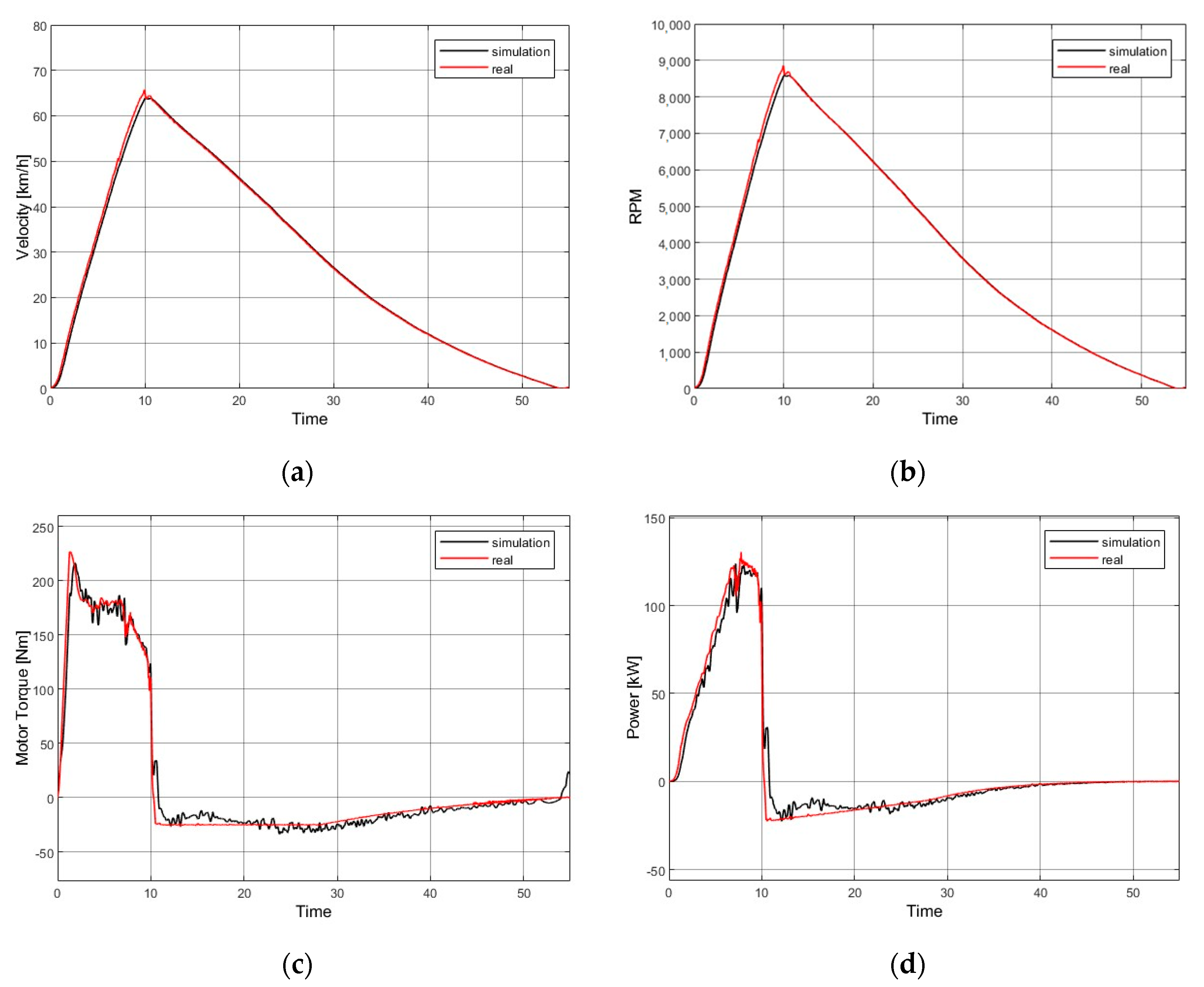

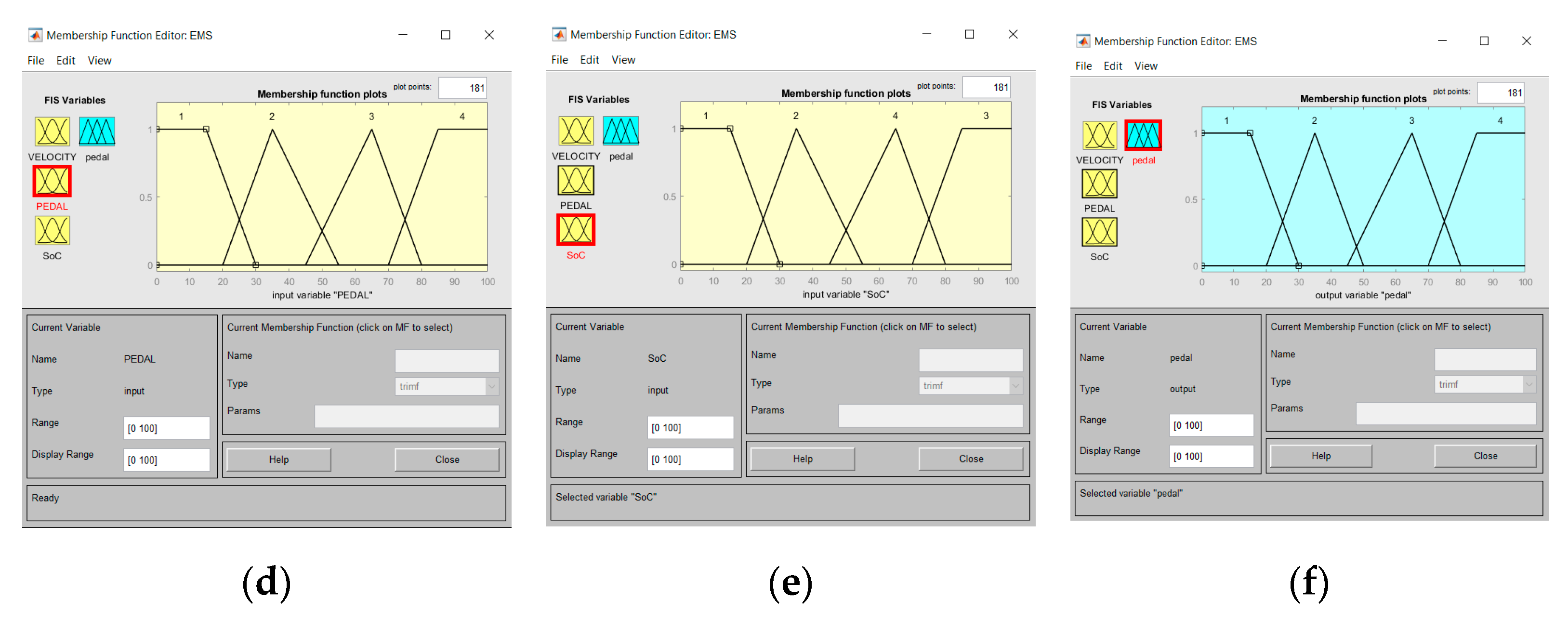

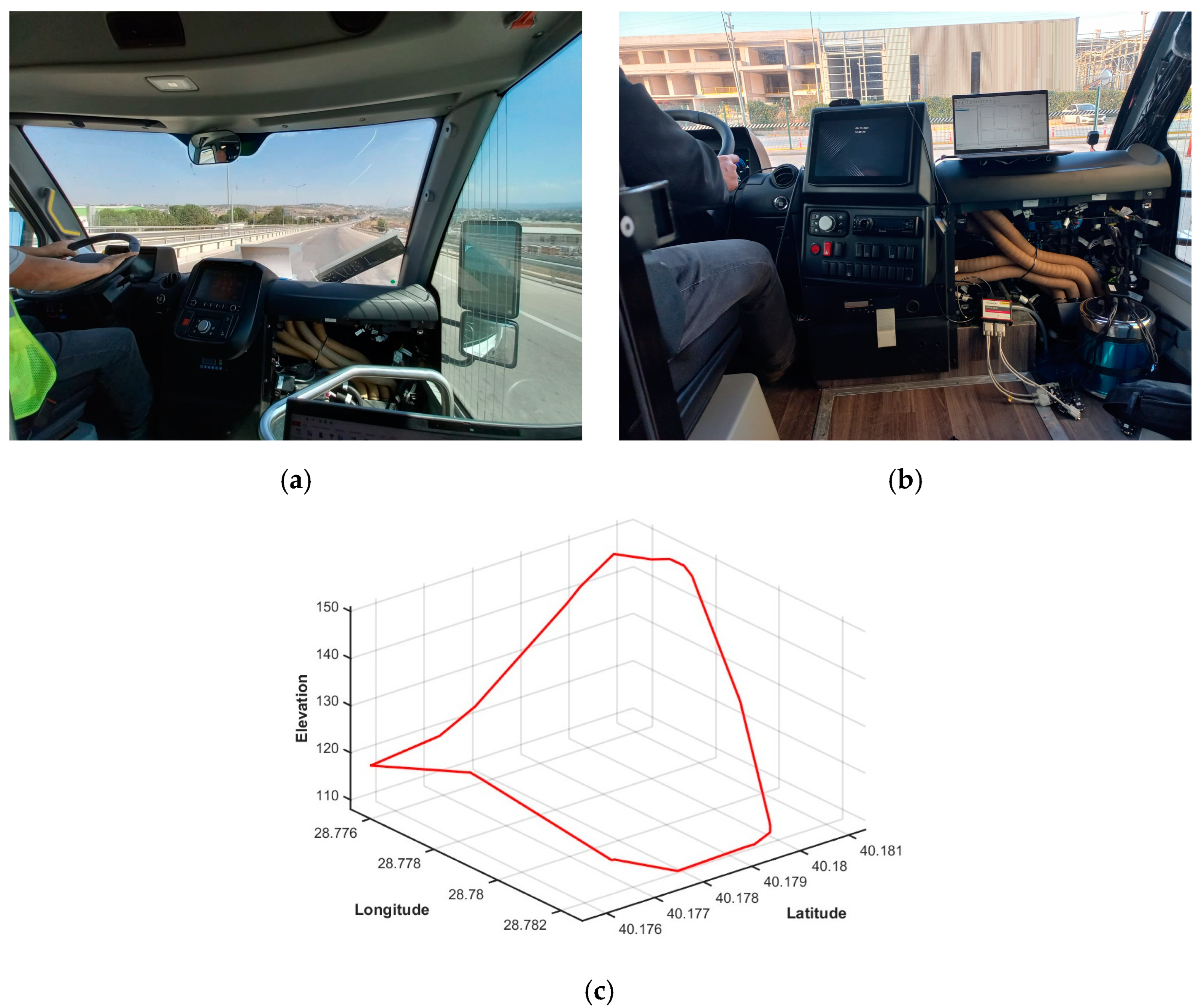

2.2. Virtual Electric Vehicle Model Validation

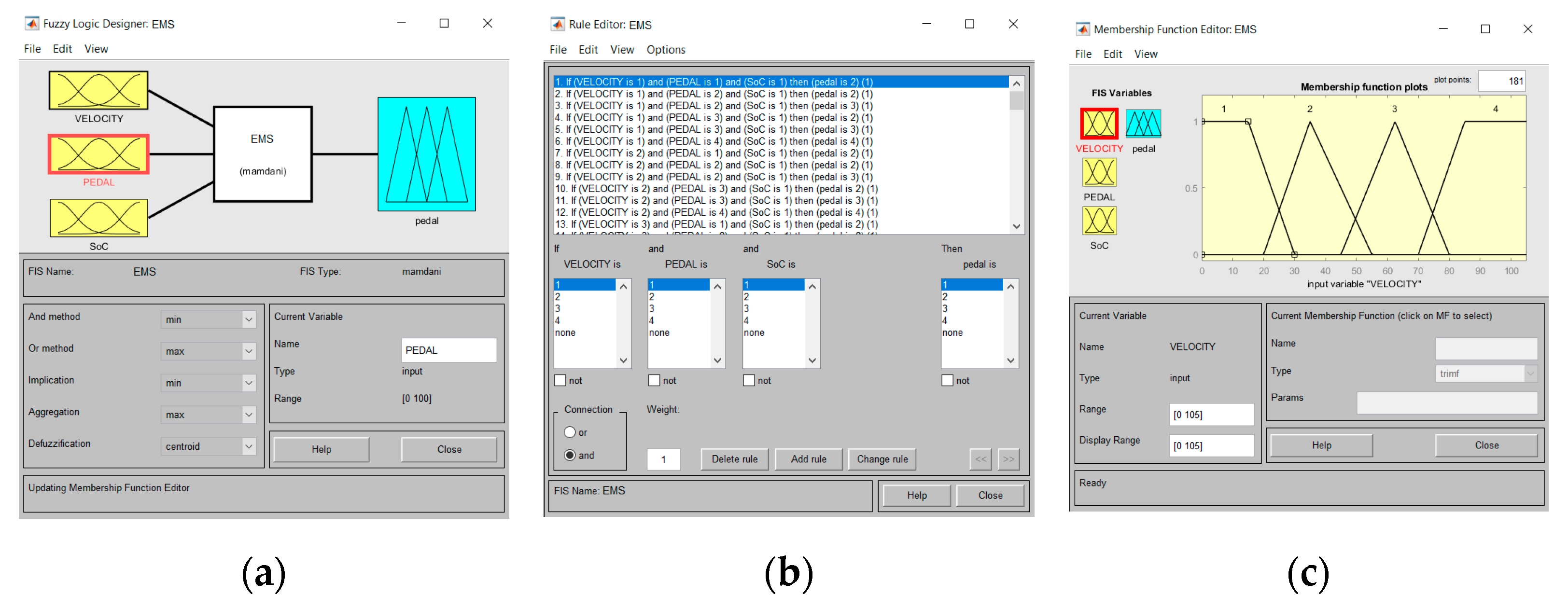

2.3. FLC Integration to Virtual Vehicle Model

2.3.1. The First Trial of FLC

2.3.2. The Second Trial of FLC

2.4. Energy Assessment on a Bus Fleet

3. Results

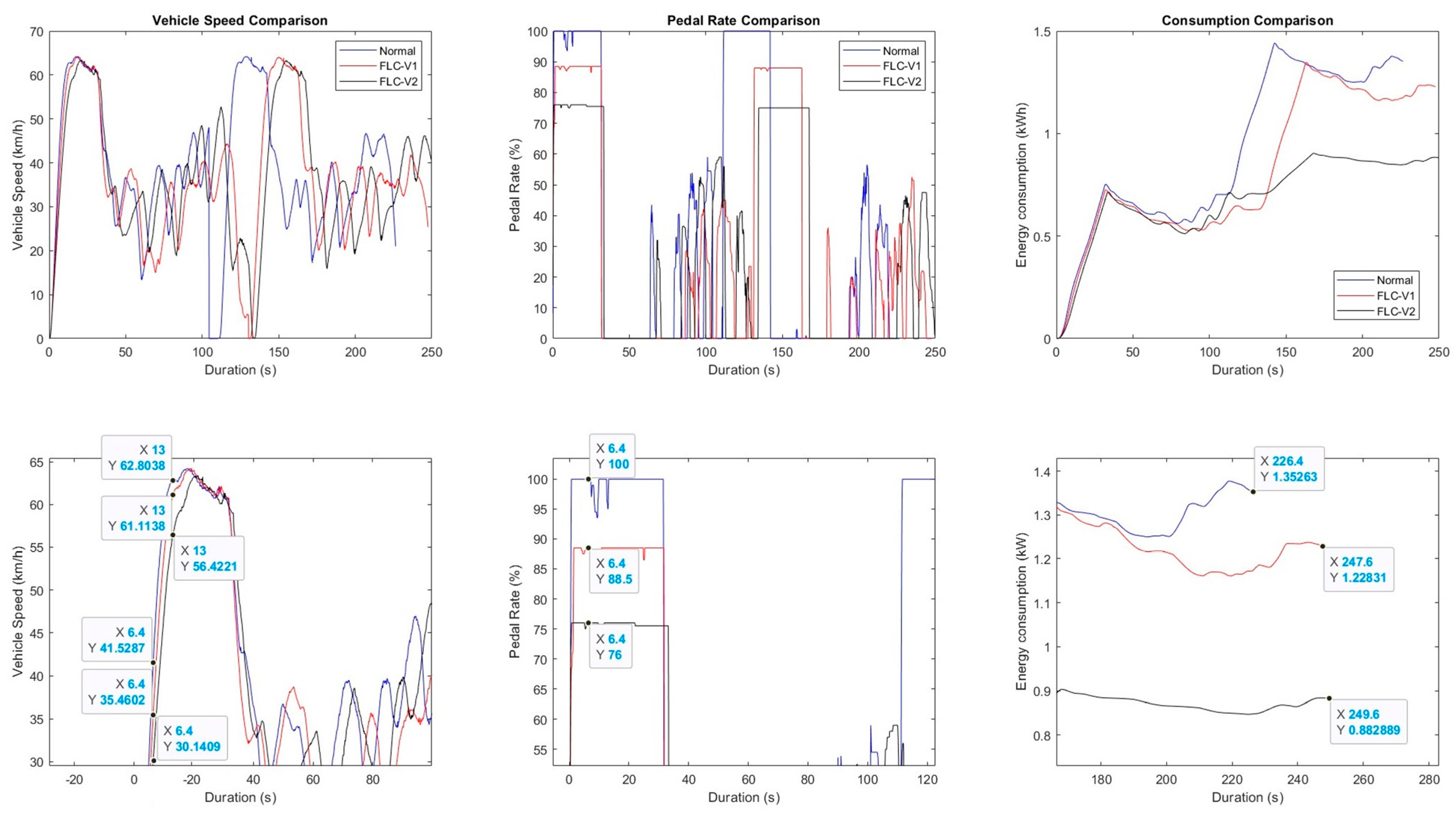

3.1. FLC Integrated First Trial Results

3.2. FLC Integrated Second Trial Results

3.3. Energy Assessment on a Bus Fleet Results

4. Conclusions

- The virtual vehicle model is quite successful in predicting the real vehicle behavior;

- The FLC-based strategy provides serious advantages in energy consumption with acceptable performance loss;

- The FLC-based strategy provides effective results in single-energy source systems as well as hybrid vehicles;

- Battery cycle decrease can be achieved with the help of an optimal energy management strategy;

- An annual saving potential has emerged at USD 164,770.65 on an electric bus line, USD 64,017,840 on overall European EVs;

- Annual carbon emission reduction potential as 1044.09 tons for an electric bus line and 405,657.6 tons for European EVs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelaty, H.; Al-Obaidi, A.; Mohamed, M.; Farag, H.E.Z. Machine Learning Prediction Models for Battery-Electric Bus Energy Consumption in Transit. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 96, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, R. Data-Driven Estimation of Energy Consumption for Electric Bus under Real-World Driving Conditions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 98, 102969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savran, E.; Karpat, E.; Karpat, F. GA and WOA-Based Optimization for Electric Powertrain Efficiency. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2024, 23, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparber, W.; Grotto, A.; Zambelli, P.; Vaccaro, R.; Zubaryeva, A. Evaluation of Different Scenarios to Switch the Whole Regional Bus Fleet of an Italian Alpine Region to Zero-Emission Buses. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamuła, T.; Pamuła, D. Prediction of Electric Buses Energy Consumption from Trip Parameters Using Deep Learning. Energies 2022, 15, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Fu, Q.; Li, Y.; Chu, H.; Niu, E. Optimal Model of Electric Bus Scheduling Based on Energy Consumption and Battery Loss. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savran, E.; Karpat, E.; Karpat, F. Energy-Efficient Anomaly Detection and Chaoticity in Electric. Sensors 2024, 24, 5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savran, E.; Karpat, E.; Karpat, F. Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle Hydrogen Consumption and Battery Cycle Optimization Using Bald Eagle Search Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özel, M.A.; Şefkat, G. Experimental and Numerical Study of Energy and Thermal Management System for a Hydrogen Fuel Cell-Battery Hybrid Electric Vehicle. Energy 2022, 238, 121794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.H.R.; Silva, F.L.; Lourenço, M.A.M.; Eckert, J.J.; Silva, L.C.A. Vehicle Drivetrain and Fuzzy Controller Optimization Using a Planar Dynamics Simulation Based on a Real-World Driving Cycle. Energy 2022, 257, 124769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahic, A.; Eskander, M.; Avdevicius, E.; Schulz, D. Energy Consumption of Battery- Electric Buses: Review of Influential Parameters and Modelling Approaches. B&H Electr. Eng. 2023, 17, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savran, E.; Karpat, F. Synthetic Data Generation Using Copula Model and Driving Behavior Analysis. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navin, N.K. A Multiagent Fuzzy Reinforcement Learning Approach for Economic Power Dispatch Considering Multiple Plug-in Electric Vehicle Loads. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 1431–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Chen, L.; Lopes, A.M.; Li, X.; Xie, S.; Li, P.; Chen, Y. Hybrid Deep Neural Network with Dimension Attention for State-of-Health Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy 2023, 278, 127734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, S.; Lopes, A.M.; Li, H.; Bao, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, P. A New SOH Estimation Method for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Model-Data-Fusion. Energy 2024, 129597, 129597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pimentel, Y.; Osuna-Galán, I.; Avilés-Cruz, C.; Villegas-Cortez, J. Power Supply Management for an Electric Vehicle Using Fuzzy Logic. Appl. Comput. Intell. Soft Comput. 2018, 2018, 2846748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleeb, H.; Sayed, K.; Kassem, A.; Mostafa, R. Power Management Strategy for Battery Electric Vehicles. IET Electr. Syst. Transp. 2019, 9, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateichyk, V.; Kostian, N.; Smieszek, M.; Mosciszewski, J.; Tarandushka, L. Evaluating Vehicle Energy Efficiency in Urban Transport Systems Based on Fuzzy Logic Models. Energies 2023, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Bie, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, L. Trip Energy Consumption Estimation for Electric Buses. Commun. Transp. Res. 2022, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulgeris, S.; Zafeiriadis, A.; Athanasopoulos, N.; Tzivelou, Ν.; Michali, M.E. Evaluation of Energy Consumption and Electric Range of Battery Electric Busses for Application to Public Transportation. Transp. Eng. 2022, 00, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Ma, C.; Zhao, C. An Adaptive Fuzzy Logic-Based Energy Management Strategy on Battery/Ultracapacitor Hybrid Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2016, 2, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Afonso, Ó. Impact of Powertrain Electrification on the Overall CO2 Emissions of Intercity Public Bus Transport: Tenerife Island Test Case. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelkrem, O.A.; Lervåg, K.Y.; Babri, S.; Lu, C.; Södersten, C.J. A Battery Electric Bus Energy Consumption Model for Strategic Purposes: Validation of a Proposed Model Structure with Data from Bus Fleets in China and Norway. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 94, 102804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, H.; Mansour, C.; Haddad, M.; Nemer, M.; Stabat, P. Energy Consumption and Battery Sizing for Different Types of Electric Bus Service. Energy 2022, 239, 122454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojević, I.A.; Taranović, D.S. Influencing Factors on Electricity Consumption of Electric Bus in Real Operating Conditions. Therm. Sci. 2023, 27, 767–784. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, K.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Hua, X.; Long, W. Energy-Optimal Speed Control for Connected Electric Buses Considering Passenger Load. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würtz, S.; Bogenberger, K.; Göhner, U.; Rupp, A. Towards Efficient Battery Electric Bus Operations: A Novel Energy Forecasting Framework. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Bus. 10 New Volvo Electric Buses in Luxembourg City. Towards a Full Electric Fleet by 2030. Available online: https://www.sustainable-bus.com/electric-bus/10-volvo-electric-buses-in-luxembourg-city/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Yavaş, Ö.; Savran, E.; Nalbur, B.E.; Karpat, F. Energy and Carbon Loss Management in an Electric Bus Factory for Energy Sustainability. Transdiscipl. J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 13, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Paris Agreement. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/paris-agreement (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Naef, A. The Impossible Love of Fossil Fuel Companies for Carbon Taxes. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 217, 108045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supapo, K.R.M.; Lozano, L.; Tabañag, I.D.F.; Querikiol, E.M. A Geospatial Approach to Energy Planning in Aid of Just Energy Transition in Small Island Communities in the Philippines. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparotto, J.; Da Boit Martinello, K. Coal as an Energy Source and Its Impacts on Human Health. Energy Geosci. 2021, 2, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, A.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Hossain, M.A.; Ahmed, M.R. Exploration and Corrective Measures of Greenhouse Gas Emission from Fossil Fuel Power Stations for Bangladesh. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, L.; Sheng, X.; Liu, M.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Q.; Zuo, J. Life Cycle Cost of Electricity Production: A Comparative Study. Energies 2021, 14, 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). More Countries Are Pricing Carbon, but Emissions Are Still Too Cheap. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/07/21/blog-more-countries-are-pricing-carbon-but-emissions-are-still-too-cheap (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Weiss, M.; Winbush, T.; Newman, A.; Helmers, E. Energy Consumption of Electric Vehicles in Europe. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareth, R. EV Mileage Increase as Petrol and Diesel Vehicles Drive Fewer Miles. Available online: https://www.fleetnews.co.uk/news/ev-mileages-increase-as-petrol-and-diesel-vehicles-drive-fewer-miles (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Europe Environment Agency. New Registrations of Electric Vehicles in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/new-registrations-of-electric-vehicles (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Etxandi-santolaya, M.; Canals, L.; Corchero, C. Estimation of Electric Vehicle Battery Capacity Requirements Based on Synthetic Cycles. Transp. Res. Part D 2023, 114, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The MathWorks Inc. Pricing and Licensing. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/pricing-licensing.html?prodcode=ML&intendeduse=comm (accessed on 22 September 2024).

| Property | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle length | 6–8 | |

| Motor type | PMSM | |

| Maximum motor power | 100–200 | kW |

| Maximum motor torque | 200–300 | Nm |

| Battery type | Li-ion | |

| Battery capacity | 70–150 | kWh |

| Passenger capacity | 18–35 | |

| Vehicle full load | 3000–5000 | kg |

| Transmission ratio | 12–20 | |

| Frontal area | 5–6 | m2 |

| Drag coefficient | 0.6 | |

| Rolling coefficient | 0.0082 |

| Feature | FLC-V1 | FLC-V2 |

|---|---|---|

| Energy consumption reduction (%) | 9.16% | 34.69% |

| Performance loss (%) | 2.69% | 10.16% |

| Parameter optimization | Manuel | Manuel |

| Application method | Simulation and real-time | Real-time |

| Method complexity | low | low |

| Membership function types | trapmf | trapmf |

| Input 1 (Velocity) and membership function range | 0–15–30 | 0–15–30 |

| 20–35–55 | 20–35–55 | |

| 45–62.5–80 | 45–62.5–80 | |

| 70–85–105 | 70–85–105 | |

| Input 2 (Pedal rate) and membership function range | 0–15–30 | 0–15–30 |

| 20–35–55 | 20–35–55 | |

| 45–62.5–80 | 45–65–80 | |

| 70–85–100 | 70–80–100 | |

| Input 3 (SoC) and membership function range | 0–15–30 | 0–15–30 |

| 20–35–55 | 20–35–55 | |

| 45–62.5–80 | 45–62–80 | |

| 70–85–100 | 70–83–100 | |

| Output (Maximum pedal rate) and membership function range | 0–15–30 | 0–15–30 |

| 20–35–50 | 20–32–50 | |

| 45–65–80 | 45–62.5–80 | |

| 70–85–100 | 70–83–100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Savran, E.; Karpat, E.; Karpat, F. Sustainable Energy Management in Electric Vehicles Through a Fuzzy Logic-Based Strategy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010089

Savran E, Karpat E, Karpat F. Sustainable Energy Management in Electric Vehicles Through a Fuzzy Logic-Based Strategy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleSavran, Efe, Esin Karpat, and Fatih Karpat. 2025. "Sustainable Energy Management in Electric Vehicles Through a Fuzzy Logic-Based Strategy" Sustainability 17, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010089

APA StyleSavran, E., Karpat, E., & Karpat, F. (2025). Sustainable Energy Management in Electric Vehicles Through a Fuzzy Logic-Based Strategy. Sustainability, 17(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010089