What Drives Successful Campus Living Labs? The Case of Utrecht University

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Higher Education System: HEI as Regime

1.2. CLLs as a Protected Space for Sustainability at HEIs

1.3. Research Gap and Question

What factors influence the development of successful campus living labs as protected spaces for sustainability innovation?

2. Empirical Context

2.1. Sustainability at Utrecht University

2.2. Center for Living Labs at Utrecht University

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Perceived Success in Campus Living Labs

4.2. Enabling Factors for Protected Space Development

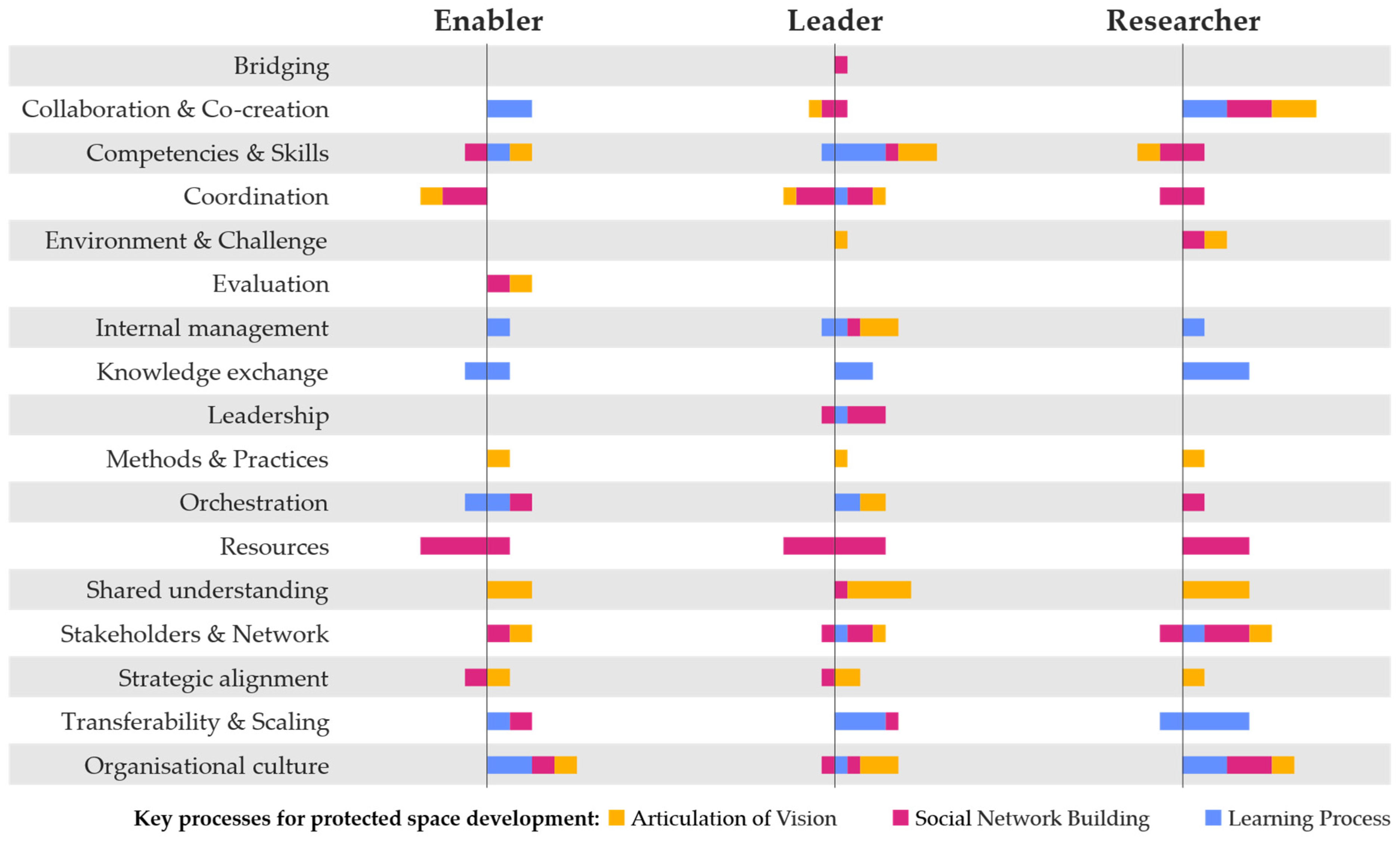

4.2.1. Broad Three-Process Factors

4.2.2. Two-Process Factors

“I do think what has worked is like having three different tracks... This is a good narrative to explain to people and also fits with what we are actually doing. It’s also helpful for our focus, and if there are any other opportunities that come around, we can always be open to those. But I would say that almost everything we do can be connected to one of those three things”.(Leader 2)

4.2.3. Vision-Specific Factors

“At some point, we just thought, well, [theme] is the right word to connect it all. So that people can connect their own work to that vision, because it’s easy to explain to others what you’re doing. It also helps with focus, which only strengthens itself because if the focus is right, you also know what things you might be doing or not”.(Leader 2)

4.2.4. Network-Specific Factors

“If you don’t have enough money, then eventually, all the living labs will stop”.(Leader 1)

“If you have a great idea and you’re the first in the world to do it, of course, you need a lot of money. An organisation like this has an obligation to support the development of new things. If you always say that if it costs more, it’s impossible, then we never move forward. You have to make space for innovation”.(Enabler 3)

“A lot of our work is planned in long-term cycles, and living labs pop up out of nowhere. We don’t see them coming, so the only work you can prepare for is what you already anticipate. If you hire someone dedicated to living labs, there’s a chance they’ll have nothing to do for a month.”.(Enabler 2)

4.2.5. Learning-Specific Factors

4.2.6. Peripheral Factors

5. Discussion

5.1. Perceived Success

5.2. Enabling Factors

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SNM | Strategic niche management |

| MLP | Multi-level perspective |

| HEIs | Higher education institutions |

| CLLs | Campus living labs |

| UU | Utrecht University |

| CLU | Centre for Living Labs |

| GOLL | Green Office Living Lab |

Appendix A

- Modified from Calvo et al., 2018 [23].

- Introduction

- Request permission for recording.

- Introduce myself and the research.

- Purpose of the research.

- Extra follow-up questions.

- Can you tell me more about X that you just told me? Can you give me an example of X?

- General questions

- What is your role at Utrecht University?

- Have you heard about living labs? Have you worked related to living labs?

- What is a LL for you?

- What is your living lab about? (Which LL have you worked?) In which LL have you participated?

- Why did you choose a living lab approach?

- What is your role there?

- How it all started? (Living labs, sustainability) What makes it difficult? What helped?

- What does the LL/your project (you are working on) aim to solve at the UU?

- Strategic niche management

- Social network building

- Which stakeholders have been involved (so far)? (internal, regional, national, international)

- How is the interaction between stakeholders? (formal, informal)

- Are there enough resources available (developing the LL)? (i.e., financial, human, time, informational)

- Who (in the network) provided which resources? Have you experienced a lack of resources?

- Is this a successful network? What makes a network/team successful?

- Articulation of vision

- Is there a shared vision? Or do the network/members think different things?

- How has the vision evolved (in time/during the project)?

- How has the vision been articulated (between stakeholders)?

- On which experiences were the vision-based?

- How did you resolve conflicts or misalignments?

- What helped to build a common vision? What makes it more difficult?

- Learning processes

- What (type of) learning happened in the project? What have you learned about the organisation?

- How was learning organised? Or was it organic?

- How do you store and share the results and data?

- What were the most surprising results?

- What was helpful for the learning process?

- What made it more difficult?

- Closing

- How do you see (your) living lab evolving?

- What does success look like? (For what would you receive a medal/prize?)

- What do you think will happen after the fund/project ends?

- What do you need more in your LL (to be successful)?

- What do you need less in your LL (to be successful)?

- Any other remarks or last thoughts?

- Who do you recommend I interview next?

Appendix B

| Factor | Subfactor |

|---|---|

| Bridging | connect faculty with the operational department |

| connect the operational department with the faculty | |

| Collaboration and Co-creation | building a strong community feeling |

| collaboration across boundaries | |

| focusing on a common and interesting purpose and vision | |

| Competencies anbd Skills | action-oriented experimentation |

| active listening and empathise | |

| aligning motivations and capabilities | |

| incremental, iterative and agile process | |

| mapping (stakeholders, process, infrastructure) | |

| open and effective communication | |

| outside-the-box and transdisciplinary thinking | |

| professional skills for students | |

| reporting | |

| understanding of the governance and structure of the university | |

| understanding of the living lab concept | |

| Coordination | dedicated central roles |

| embedding living labs into the university with clearly defined roles | |

| incentive creation and holistic recognition and rewards systems | |

| streamlining operations by capacity matching, thematic clustering and efficient budget allocation | |

| Environment and Challenge ** | focusing on an ambitious and trendy societal problem |

| focusing on an iconic location with a widely shared problem | |

| Evaluation | adjusting scope and goals to reality |

| feasibility | |

| incorporate cradle-to-grave perspective | |

| initial intake | |

| opportune communication about restrictions | |

| Internal management | adjusting scope and goals to reality |

| differentiate theme using different tracks | |

| identifying and sharing everyone’s expectations and needs | |

| improving communication among stakeholders | |

| keeping all parties informed about processes and key decisions | |

| managing processes to achieve desired outcomes | |

| Prioritisation of goals and activities | |

| student supervision | |

| Knowledge Exchange ** | enhancing students’ creative and innovative real-world experiential learning experiences |

| gathering stakeholder input | |

| institutional/organisational learning | |

| involving skilled users | |

| promoting inter-organisational learning | |

| provide periodic spaces for reflection | |

| Leadership | intrapreneurship |

| recognising bottom-up contributions | |

| recognising leadership contributions from students and stakeholders | |

| support from high-level directors | |

| Methods and Practices | effective meetings |

| experimenting | |

| program management approach | |

| structured frameworks and guidelines | |

| visual representations | |

| Orchestration * | bridging and intermediary |

| build network | |

| building spaces to learn | |

| communication | |

| creating structured opportunities to meet | |

| empower others to act | |

| evaluation | |

| leadership | |

| mediation | |

| mental support | |

| provide seed funds | |

| setting goals and strategy | |

| supervision and mentoring students | |

| support | |

| teaching the living lab concept | |

| thinking along | |

| Resources ** | dedicated budget from the university |

| dedicated time and managerial support | |

| flexible budget | |

| integrating financing stakeholder into the network | |

| leverage internal knowledge | |

| sustained funding | |

| Shared understanding | commonly owned living lab vision |

| flexibility while keeping the focus | |

| flexible budget | |

| iterative refinement and perspectives integration | |

| operationalisation | |

| overarching theme | |

| shaping the narrative and identifying themes | |

| shared interests and values | |

| stakeholders use consistent language | |

| Stakeholders and Network | encouraging serendipitous connections |

| engaging relevant and diverse expertise | |

| excluding misaligned stakeholders | |

| involving users perspectives | |

| leveraging existing relationships and networks | |

| Strategic alignment | embracing third mission |

| empower others to help reach institutional goals | |

| goal in the strategic plan | |

| high university sustainability ambition | |

| operations anchor to reality | |

| Transferability and Scaling | implementing systems for structured data collection and internal sharing |

| reporting and communication | |

| sharing knowledge and inspiration | |

| Organisational culture ** | academic freedom |

| alignment with personal and professional values | |

| failure as a learning opportunity | |

| high sustainability awareness | |

| open communication, honesty and transparency | |

| openness to new approaches | |

| positive mindset | |

| support from top management | |

| transdisciplinary |

Appendix C

| Factor | Definition | Present | Absent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning | Network | Vision | Total | Learning | Network | Vision | Total | ||

| Bridging | connecting the two internal worlds of the HEI: faculty and operational departments. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Collaboration and Co-creation | the action of working together in a CLL. | 4 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Competencies and Skills | the individual abilities required to develop and participate in CLLs. | 5 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Coordination | the HEI-wide organisation of different units, faculties, teams, and groups. | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| Environment and challenge | selecting locations where real societal problems occur. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Evaluation | assessing CLLs at the start, throughout, and at the conclusion to determine their feasibility, effectiveness, impact, and progress. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Internal management | how people and processes are coordinated within a CLL. | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Knowledge exchange | the process of sharing and acquiring information, insights, and skills. | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Leadership | the ability of an individual or group to influence, guide, and inspire others. | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Methods and Practices | the structured approaches and tools used to address problems within a CLL. | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Orchestration | a subtle yet strategic form of coordination in CLLs, typically carried out by a central unit. | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Resources | the financial, human, knowledge, and institutional assets necessary for CLLs. | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Shared understanding | a mutual awareness of each other’s interests and purpose. | 0 | 1 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stakeholders and network | who should be involved in a CLL, when to engage them, and how to manage participation. | 2 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Strategic alignment | how CLLs activities contribute to the broader sustainability goals of the HEI. | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Transferability and Scaling | the ability of CLLs to replicate and expand their impact. | 8 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Organisational culture | the overall environment, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours that shape ways of working, researching, teaching and studying within CLLs. | 5 | 4 | 5 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

References

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Geels, F.W. Strategic Niche Management and Sustainable Innovation Journeys: Theory, Findings, Research Agenda, and Policy. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2008, 20, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Berkhout, T.; Cayuela, A.; Campbell, A. Next Generation Sustainability at the University of British Columbia: The University as Societal Test-Bed for Sustainability. In Regenerative Sustainable Development of Universities and Cities; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 27–48. ISBN 9781781003640. [Google Scholar]

- Horan, W.; Shawe, R.; Moles, R.; O’Regan, B. National Sustainability Transitions and the Role of University Campuses: Ireland as a Case Study. In Sustainability on University Campuses: Learning, Skills Building and Best Practices; Leal Filho, W., Bardi, U., Eds.; World Sustainability Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 255–270. ISBN 978-3-030-15863-7. [Google Scholar]

- Horan, W.; Shawe, R.; O’Regan, B. Ireland’s Transition towards a Low Carbon Society: The Leadership Role of Higher Education Institutions in Solar Photovoltaic Niche Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatmon, T.D.; Krill, H.E.; Rynes, J.J. Food Production as a Niche Innovation in Higher Education. In The Contribution of Social Sciences to Sustainable Development at Universities; Leal Filho, W., Zint, M., Eds.; World Sustainability Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 145–159. ISBN 978-3-319-26864-4. [Google Scholar]

- Radinger-Peer, V.; Pflitsch, G.; Kanning, H.; Schiller, D. Establishing the Regional Sustainable Developmental Role of Universities—From the Multilevel-Perspective (MLP) and Beyond. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Vanegas, A.; Ramani, S.V.; Volante, L. Service-Learning as a Niche Innovation in Higher Education for Sustainability. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1291669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidewind, U.; Augenstein, K. Analysing a Transition to a Sustainability-Oriented Science System in Germany. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2012, 3, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spira, F.; Baker-Shelley, A. Driving the Energy Transition at Maastricht University? Analysing the Transformative Potential of the Student-Driven and Staff-Supported Maastricht University Green Office. In Transformative Approaches to Sustainable Development at Universities; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; World Sustainability Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 207–224. ISBN 978-3-319-08836-5. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckrath, C.; Rosales-Carreón, J.; Worrell, E. Conceptualisation of Campus Living Labs for the Sustainability Transition: An Integrative Literature Review. Environ. Dev. 2025, 54, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, L.A.; Bossert, M.; Newman, J.; Ferraz, F.; Robinson, Z.P.; Agarwala, Y.; Wolff, P.J.; Jiranek, P.; Hellinga, C. Towards a Learning System for University Campuses as Living Labs for Sustainability. In Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A.L., Pretorius, R.W., Brandli, L.L., Manolas, E., Alves, F., Azeiteiro, U., Rogers, J., Shiel, C., Do Paco, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 135–149. ISBN 978-3-030-15604-6. [Google Scholar]

- Herth, A.; Verburg, R.; Blok, K. The Innovation Power of Living Labs to Enable Sustainability Transitions: Challenges and Opportunities of On-Campus Initiatives. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2024, 34, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martek, I.; Hosseini, M.R.; Durdyev, S.; Arashpour, M.; Edwards, D.J. Are University “Living Labs” Able to Deliver Sustainable Outcomes? A Case-Based Appraisal of Deakin University, Australia. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 1332–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, T.; Derr, V. Landscapes as Living Laboratories for Sustainable Campus Planning and Stewardship: A Scoping Review of Approaches and Practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 216, 104259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Ozuyar, P.G.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Azul, A.M.; Alvarez, M.G.; Da Silva Neiva, S.; Salvia, A.L.; Borsari, B.; Danila, A.; Vasconcelos, C.R. Living Labs in the Context of the UN Sustainable Development Goals: State of the Art. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Schäpke, N.; Marg, O.; Stelzer, F.; Lang, D.J.; Bossert, M.; Gantert, M.; Häußler, E.; Marquardt, E.; Piontek, F.M.; et al. Transdisciplinary Sustainability Research in Real-World Labs: Success Factors and Methods for Change. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herth, A.; Verburg, R.; Blok, K. How Can Campus Living Labs Thrive to Reach Sustainable Solutions? Clean. Prod. Lett. 2025, 8, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utrecht University. Strategic Plan 2025: Open Mind, Open Attitude, Open Science—Improving the World Sustainably Together; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Utrecht University. Sustainability Plan for Business Operations: Ambitions and Goals for Sustainable Development 2024; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, L.A.; Bossert, M. The University Campus as a Living Lab for Sustainability: A Practitioner’s Guide and Handbook; University of Technology, Hochschule für Technik Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-940670-68-7. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, S.; Morales, A.; Arias Gómez, J.E. Applying Strategic Niche Management to Understand How Universities Contribute to the Development of Social Innovation Niches: The Case of the Social Innovation Scientific Park in Colombia. Rev. De Pensam. I Anal. 2018, 23, 95–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Hak, T. Case Study Methodology in Business Research; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7506-8196-4. [Google Scholar]

- Plassnig, S.N.; Pettit, M.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, K.; Säumel, I. Successful Scaling of Edible City Solutions to Promote Food Citizenship and Sustainability in Food System Transitions. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 1032836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, K.; Cooper, I. Are Living Labs Effective? Exploring the Evidence. Technovation 2021, 106, 102311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, S. Is Sustainability a Moving Target? A Methodology for Measuring CSR Dynamics. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. 2020, 27, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heiligenberg, H.A.R.M.; Heimeriks, G.J.; Hekkert, M.P.; van Oort, F.G. A Habitat for Sustainability Experiments: Success Factors for Innovations in Their Local and Regional Contexts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, A.; Evans, J. Introduction: Experimenting for Sustainable Development? Living Laboratories, Social Learning and the Role of the University. In Regenerative Sustainable Development of Universities and Cities; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-1-78100-364-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta, A.; Vreugdenhil, H.; Slinger, J. Harvesting Living Labs Outcomes through Learning Pathways. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 9, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Ritter, L.J.; Wisse Gonzales, C. Cultivating a Collaborative Culture for Ensuring Sustainable Development Goals in Higher Education: An Integrative Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.C.; Graham, A.C. Toward an Empirical Research Agenda for Sustainability in Higher Education: Exploring the Transition Management Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, R.; Herselman, M. Applying a Living Lab Methodology to Support Innovation in Education at a University in South Africa. TDSA 2015, 11, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, W.M.; Henriksen, H.; Spengler, J.D. Universities as the Engine of Transformational Sustainability toward Delivering the Sustainable Development Goals: “Living Labs” for Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Preez, M.; Arkesteijn, M.H.; den Heijer, A.C.; Rymarzak, M. Campus Managers’ Role in Innovation Implementation for Sustainability on Dutch University Campuses. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, B.; Schaffers, H.; Turkama, P.; Ståhlbröst, A.; Ballon, P. Cross Border Living Labs Networks to Support SMEs Accessing New Markets. In Proceedings of the eChallenges e-2011 Conference Proceedings, Florence, Italy, 26–28 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkarainen, L.; Hyysalo, S. The Evolution of Intermediary Activities: Broadening the Concept of Facilitation in Living Labs. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2016, 6, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geenhuizen, M. A Framework for the Evaluation of Living Labs as Boundary Spanners in Innovation. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2018, 36, 1280–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S. Living Labs as Open Innovation Networks: Networks, Roles and Innovation Outcomes. Ph.D. Thesis, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Save, P.; Cavka, B.T.; Froese, T. Evaluation and Lessons Learned from a Campus as a Living Lab Program to Promote Sustainable Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, P.; Sharp, D.; Pigeon, J.; Raven, R. Governing University Living Labs for Sustainability Transformations: Insights from 18 International Case Studies. In Sustainability Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnheim, B.; Sovacool, B.K. Exploring the Role of Failure in Socio-Technical Transitions Research. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 37, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, A.-G.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M.; Kortelainen, M. Actor Roles and Role Patterns Influencing Innovation in Living Labs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauth, J.; De Moortel, K.; Schuurman, D. Living Labs as Orchestrators in the Regional Innovation Ecosystem: A Conceptual Framework. J. Responsible Innov. 2024, 11, 2414505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name Initiative | Purpose: Innovation for Sustainability Transition | Place: Real-Life Campus Experimentation | Network: Transdisciplinary | Approach: Mode of Co-Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFAs Remediation | Research and test sustainable soil remediation techniques, moving away from traditional “dig and dump” methods. | Contaminated field at UU campus, formerly a fire response training site, used by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. | Internal: Researchers and Operations External | Test-bed: Research-focused, starting with an explorative MSc thesis, followed by hiring PhD candidates. |

| Healthy Heidelberglaan | Provide data and tested innovations for local climate adaptation to guide sustainable redevelopment of Heidelberglaan. | Heidelberglaan at UU campus: a busy central hub with mobility, food, and library services for Campusians. | Internal: Operations, researchers, teachers and students External | Strategic/Educational: Sensors and the digital twin, developed with external stakeholders, features innovations tested by students. |

| Zero Waste | Support UU’s zero-waste transformation by developing and testing circular waste management strategies and innovations. | UU campus, including diverse facilities, such as laboratories, restaurants, classrooms, and offices. Campusians generate waste. | Internal: Operations, researchers, teachers and students External | Strategic: Part of the Zero Waste Program aligned with the strategic plan. |

| Greening the UBB square | Transform the University Library courtyard into a green oasis for sustainability, biodiversity, cultural expression, and educational experimentation. | Inner courtyard of Utrecht’s University Library: historically significant, underutilised, and overly paved, mainly used by students. | Internal: Operations, teachers and students External | Grassroots: Initiated by students and then, transformed into an experimental space for a minor program. |

| Bio-receptivity | Test and promote bio-receptive materials to boost biodiversity, blend buildings into the landscape, and capture fine dust. | P-Olympos parking lot at UU campus with gabions of recycled debris and grass verges as experimental spaces for teaching and learning. | Internal: Operations, teachers and students | Educational: Educational, as part of a course. |

| Biodiversity | Monitoring system using citizen science (BioBlitz) to increase the effectiveness of biodiversity restoration measures. | UU campus green areas. It involves Campusians. | Internal: Operations, researchers, teachers and students External | Strategic: Part of the Biodiversity Program aligned with the strategic plan. |

| Sustainable Laboratories | Exchange best practices to implement sustainability practices. | UU Laboratories. It involves the users of the laboratories, such as technicians and researchers. | Internal: Operations and researchers (faculties) | Grassroots: Working group |

| Circular Pavilion | Future meeting point at the heart of the campus, showcasing UU’s commitment to a sustainable society. | New entrance of the Botanical Gardens. | Internal: Operations and researchers | Co-design |

| Energy | There is no clear aim to innovate. | LL Solar Ecology Meadow. | Commission |

| Data Analysis Phase | Task | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Data familiarisation | Organise the data according to the topics outlined in the interview guide. | Identification of two main topics: Perceived success and factors. |

| (2) Coding | (a) Perceived success: Apply an inductive approach to identify emerging categories. | Identification of three dimensions of success. |

| (b) Enabling factors: Apply a deductive approach [19], allowing factors to emerge. | Frequency of present/absent enabling factors per role. | |

| (3) Theorising the codes | Synthesise previous phases and compare data to existing theory. | Insights on success and key factors for protected space development. |

| Sample Features | Options | Frequency | Proportion * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initiative | PFAs Remediation | 2 | 13% |

| Healthy Heidelberglaan | 2 | 13% | |

| Zero Waste | 2 | 13% | |

| Greening the UBB square | 2 | 13% | |

| Bio-receptivity | 2 | 13% | |

| Biodiversity | 1 | 7% | |

| Sustainable Laboratories | 3 | 20% | |

| Several initiatives | 1 | 7% | |

| Role | Enabler | 4 | 27% |

| Leader | 7 | 47% | |

| Researcher | 4 | 27% | |

| Position | (Assistant/Associate) Professor | 2 | 13% |

| Campus operations | 7 | 47% | |

| Faculty operations | 3 | 20% | |

| Student | 3 | 20% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stuckrath, C.; Chappin, M.M.H.; Worrell, E. What Drives Successful Campus Living Labs? The Case of Utrecht University. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125506

Stuckrath C, Chappin MMH, Worrell E. What Drives Successful Campus Living Labs? The Case of Utrecht University. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125506

Chicago/Turabian StyleStuckrath, Claudia, Maryse M. H. Chappin, and Ernst Worrell. 2025. "What Drives Successful Campus Living Labs? The Case of Utrecht University" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125506

APA StyleStuckrath, C., Chappin, M. M. H., & Worrell, E. (2025). What Drives Successful Campus Living Labs? The Case of Utrecht University. Sustainability, 17(12), 5506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125506