Abstract

In the thematic context of rural materialities, the materialities of medieval origin are studied. In this sense, the process of land occupation and colonization in the Middle Ages as a frame of the emergence of settlements and original materialities is analyzed. The study combines historical and documentary study along with visual and spatial analysis. The study area is the area of Entresierras in the northeast of the province of Segovia, which has maintained its medieval settlement and the initial or traditional structure of many villages to the present day. In this area, spatial biographies of the villages and styles of the medieval villages’ materialities in the contemporary age are finally established.

1. Introduction

The value of the recent global or planetary approaches should not be given dark, infinite nuances in places that have the courage to drive politics in geographical sites as a specific product of historical conformation [1,2]. The other is also other spaces of marginal materialities (reconstituted) [3]. The historical rural geographies have as their traditional object the interest in landscape dynamics, settlement patterns, and human transformations and changes in a place at a specific time. This traditional interest is collected within the framework of a renewed vision of geohistorical analysis in order to analyze the presence of the landscapes of the past in a key area in the present. In this orientation, the historical approach to geography amalgamates some traditions of historical and rural geographies in the context of ongoing academic tendencies in more-than-human materialities.

In the framework of sustainable urban–rural relations, the preservation of medieval cultural settlement landscapes is very important to preserving the socio-cultural keystones of historical roots in the process of global sustainable development. These landscapes offer images of villages that start from the medieval repopulation process, that have remained unchanged until today, and that are clear examples for an adequate balanced process of sustainable urban–rural development.

With the notability of post-structuralism in rural and human geography from the 1990s, territory underwent a severe criticism and notable revision. In this academic context, the idea of the emergence of a plurality of overlapping and competing territorial authorities and jurisdictions acquired relevance, giving way to a sort of new medievalism centered around a form of non-hierarchical and multi-level governance. The object of this study is the analysis of medieval sites and (sacred) medieval identities in the context of a historical spatial process of reorganization: from historical colonization through multiple processes of resistance/resilience to contemporary hybridism. The area of research is a key space named Entresierras (Segovia province) in the territory of medieval colonization in Spain between the river Duero and the Central System Mountains.

2. Historical Materialities in Permanent Transformation

In an environment of historic settlement from medieval times, the materialities, in transformation since the eleventh–twelfth centuries, have a continuous historical trajectory, with the permanent spatial and symbolic witness of the reconstituted Romanesque churches (as an example of sacred and monumental materiality). In the materialities of historical origin, mainly of medieval origin, it is possible to ask what is the old and what is the new, since these words and approximations, ‘old’ and ‘new’, must be placed in each historical period. The ‘old’ and the ‘new’ words change in value and meaning over time within the framework of long periods of resistance and resilience around zones or villages of instability.

As Knox suggests [4] (p. 1), ‘Built environments are an important expression of human geographies, reflecting cultural, economic, political, and social forces. In many sub disciplines they have been treated as an independent variable, leading to criticisms of environmental determinism. More appropriately, built environments can be seen as an important element of the socio-spatial dialectic, having reciprocal and recursive relationships with cultural, economic, political, and social phenomena at scales ranging from individual buildings to the global’. In the following subsections, the main historical and spatial milestones are analyzed that allow us to adequately contextualize the materialities in the case study.

2.1. The Historical Background—The Medieval Production of Landscapes of Colonization

Between 1085 and 1213, Christian military advances toward the south of the Iberian Peninsula allowed the repopulation of a rearguard that had previously been almost completely empty. In Castilla y León, these are the lands called ‘Extremaduras’ at that historical moment between the Duero River and the Central System [5] (p. 37). Olivera Serrano [6] suggests the existence of a ‘strategic desert’ south of the line of the Duero River, where the Castilian Extremadura is located, up to the Central System. In these very depopulated lands, colonization also affected the ‘Transierra’—lands beyond the Central System on its southern slope. The colonization of Castilian Extremadura was a means of ensuring political and territorial stability within the framework of a mobile or fluid border between the Christian world and the Muslim world. In this area, colonization was carried out through villas, which controlled large territories or ‘lands’ where numerous villages were established, and the space was organized according to criteria of economic rationality related to the new agrarian social, economic, but also mercantile orders. Another unique and territorial socioeconomic characteristic is the relative spatial dissociation between agriculture and livestock, given that both had their own spaces. In short, between the eleventh and twelfth centuries there was a new general organization of the territory that has remained until today. This new spatial articulation emerged from the relationship between conquest and colonization and the organization of the territory, constituting a border spatial structure [5] (p. 22). The communities of ‘Villa and Tierra’ are ‘border cities’ where ruralism is almost absolute [7] (p. 33). According to Valdeon [7], the Duero Valley was an unpopulated and empty area in the eighth century, and he picks up the idea of depopulation and repopulation that arises from Sánchez Albornoz [8].

The colonization of the territory located between the Duero and the Central System in the second half of the 11th century was based on small free landowners who used the haste system—occupation of vacant assets—to occupy land and put it under cultivation. Between the 8th and 11th centuries, the study territory remained very lightly populated by hermit settlements, itinerant groups of Christian ranchers, and a few Muslims dedicated to agriculture. In the 11th century, the definitive repopulation of the study area began with foreign settlers who merged with the very weak native population. The monarchy encouraged settlement through benefits of all kinds unique to the area, under municipal systems of control of extensive territories; the predominant population was called ‘Villa’ and the small surrounding villages ‘Tierra’, constituting a community of ‘Villa and Tierra’ (e.g., Fresno, Maderuelo, Sepulveda, Ayllon) from the area (Table 1). However, it was between the second half of the 12th century and the beginning of the 13th century when the repopulation impulse had more vigor and the village system that we know today was consolidated. The border economy was based on agriculture and livestock. Today, village and land communities still provide services and earn income from medieval rights. Mitre [9] (p. 165) points out that Extremadura between the Duero River and the mountains of the Central System in the 11th–12th centuries had a land occupation that was based on the formation of municipal councils with very broad terms or demarcations. These population centers would be the basis of the subsequent expansion into (dependent) peasant villages that populated their territory.

Table 1.

Historical villa and land communities in the Entresierras research area.

2.2. The Process of Land Occupation and Medieval Colonization

‘Planned nucleated settlement and subsequent settlement shift is a recognized common component in the complex development of the medieval landscape’ [10] (p. 43). This territorial characteristic of the Middle Ages in Europe is also relevant south of the Duero. As has been noted, in the last decades of the 11th century the Castilian-Leonese Christian kings had occupied the so-called Extremadura, an area located between the Duero River and the Central System. The repopulation of this area acted as a ‘border’ with the area of Muslim domain and was based on village and land communities (a central council and a large alfoz around it) (An alfoz is the set of different towns that depend on another principal and obey the same territorial jurisdiction.) [11] (p. 89). One of the first towns repopulated due to its strategic value was Sepúlveda, immediate to the study area, where there must have been a previous residual population [12] (pp. 156–157).

The medieval land occupation process in the area consisted of a territorial articulation in two steps: the distribution and the constitution of the village. After the granting or ‘pressure’ of the land—the ‘pressure’ is assets taken that were vacant—the establishment of villages was organized (Figure 1). Villages were homologous settlement units made up of single-family homes surrounded by small plots surrounded by orchards. The church was the center of sociability of the village, and generally it was the ‘own church’ of the village community. After its formation, there was a process of social and physical compaction of the village. ‘The theoretical model presents us with the village surrounded by orchards in its vicinity, with most of the land dedicated to cereals and areas of forests and pastures further away’ [5] (p. 75).

Figure 1.

Old house in Barahona del Fresno.

In them lived loosely hierarchical human groups governed by kinship ties that gave rise to the formation of the so-called ‘village communities’. The border area allowed residents to have all types of legal–procedural, economic, and tax privileges. The ‘village communities’ were small groupings of family cells. Each family cell was the holder of an individual right to exploit part of the area attributed to the group and a management capacity for the area not allocated individually or for communal use. In the stage of creation and first consolidation, there was a horizontal community tendency in the village communities and in the village and land communities. Valdeon [13] points out that ‘the village community brought together all the residents of a rural nucleus, regardless of their own social condition’ [13] (p. 210). In ‘the communities of villa and land, the egalitarian sense of their members predominated’ [13] (p. 210), but in the late Middle Ages, ‘with the passage of time the communities of villa and land had been transformed into collective lordships with the territory of the alfoz and the inhabitants of the villages as vassals’ [13] (p. 211). The villa and land communities were territorial complexes around ‘border cities’.

Isla Frez [14] points out the constitution of ‘village community’ as a geographical and habitat reality as well as a social and legal organization where property was linked to blood. The peasants would have family properties, lands, and houses, which would be transmitted within their family, and all members of the community would have collective rights over pastures and forests [14] (p. 201). Minguez [15] points out the relevance of neighborhood relations in peasant communities established on ‘no-man’s land’, in a sparsely populated territory before official colonization, on the basis of freedom for peasants. For his part, García González [16] points out the constitution of a regime of ‘full private ownership’ and a ‘mutual regime’, which founded a ‘small family farm’.

In short, from the Duero River to the Central System in the Entresierras area there was (1) a process of repopulation and colonization of an empty or weakly populated space in a border or no-man’s land (2) with an original territorial organization system of villa and land and (3) communities of peasants in villages that together formed a ‘villa and land’ system of territorial occupation and colonization. These characteristics were also common in other areas of Europe, as in the case of Norway: ‘…clustered settlements seem to have been common along…’ [17] (p. 37).

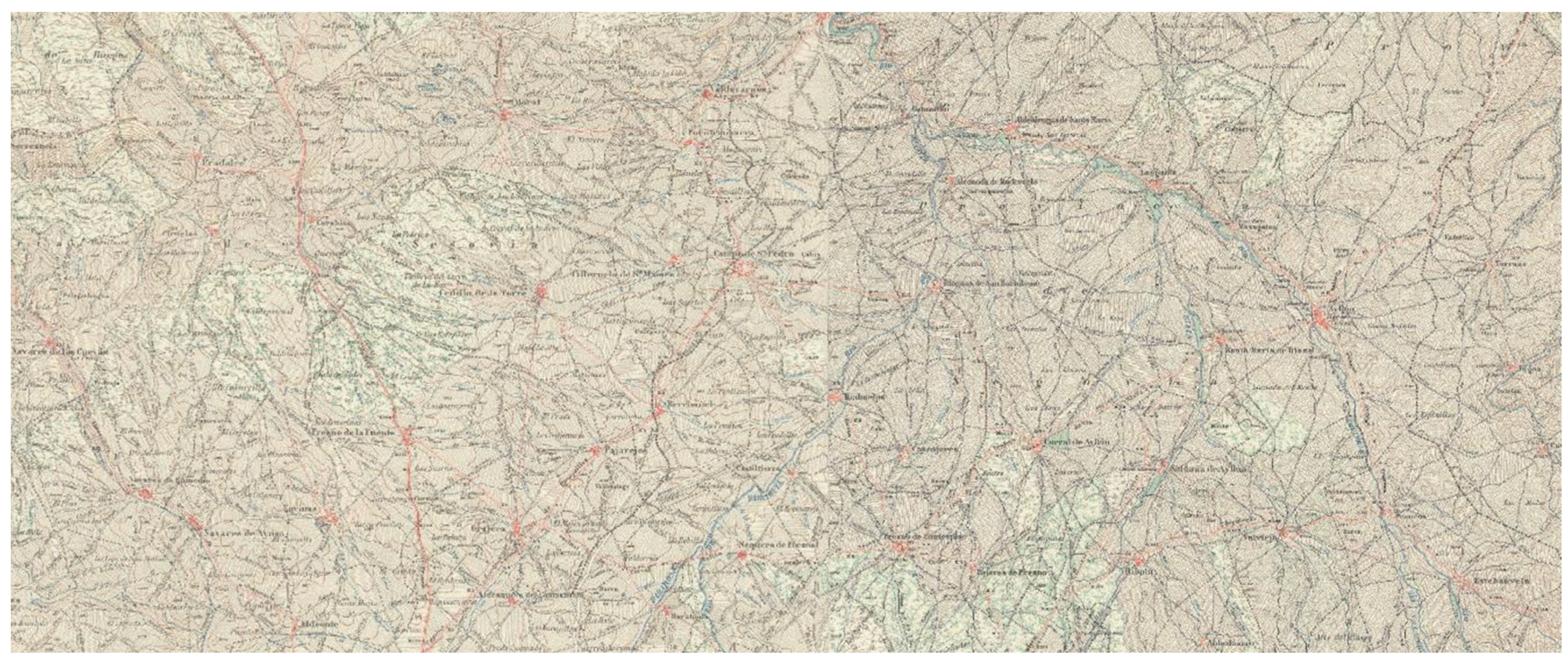

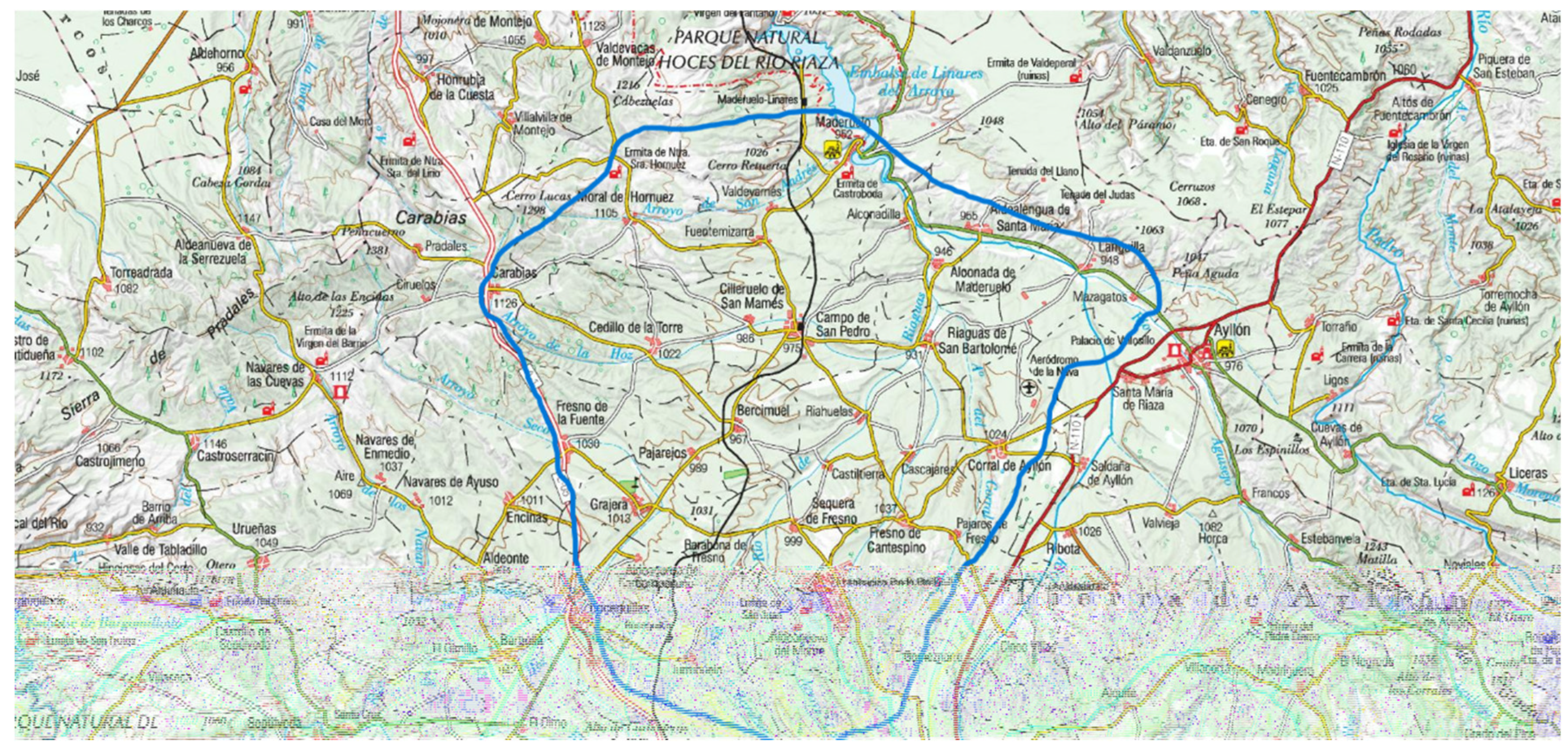

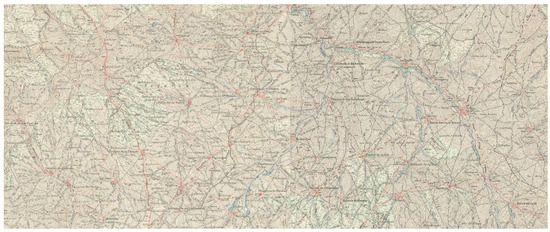

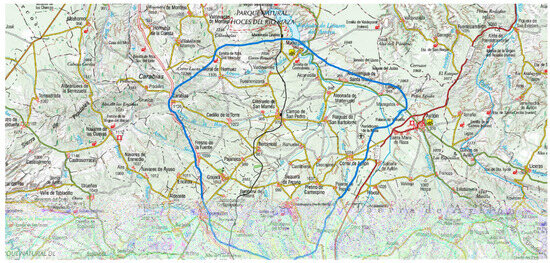

The strategic position, the rapid occupation of the land with a certain planning based on the walking distance between the villages to cover round trips in a day, and the visual recognition of the neighboring villages characterize the Entresierras area (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The structured territorial occupation and colonization in the Middle Ages have the purpose of strategically protecting the mountain passes through the Central System toward the Muslim world. This border characteristic should have encouraged complete use of the territory and eventual plowing. This initial dense settlement made it possible to press toward nearby Transierra lands and organize their occupation and colonization. The emblematic rural materialities of the Middle Ages (Romanesque churches) are a spatial landmark that embraces the settlement, which currently in many centers does not exceed the initial occupation or surface. There is a value of materiality as a whole as well as its proportionate position in the closest territorial context.

Figure 2.

Historical map of research area. First map of MTN.

Figure 3.

Map of research area. MTN.

2.3. Appropriating the Medieval Materialities and the Sense of Tierra in Historical Volatile Frontiers

The consequences of the reconquest have been long-lasting, cementing a new territorial micro-organization of the rural space as a result of the peculiar results of the territorial processes of colonization. The toponymy preserves the representation of the processes of medieval colonization (e.g., the place name Aldeanueva). As a result of the repopulation processes in the mid-13th century, there were 475 places in the bishopric of Segovia distributed irregularly across the topography. The frontier effect in land colonization, moving progressively, was democratic in nature and based on the individualism and opportunism derived from confrontation with a wilderness environment. The rural settlement pattern is a ‘sequential occupation’ that has already been observed in other areas of Europe [10,17].

The medieval organic community was established by aggregation and determined the form of medieval villages: linear–mixed–enclosed or dispersed–scattered throughout the territory. These grouped and compacted fixed materialities of the Middle Ages have been repeatedly reconstituted with an extensive biography from the 11th–12th centuries to the present. Currently, they assume compact and enclosed materialities, with a visual reference to the next village and between them, within the framework of a landscape that as a whole is unchanged since the medieval colonization stage.

Traditional low-rise buildings with long shafts on roofs associated with large corrals characterize the medieval villages in the study area (Figure 1). The roofs of houses with a long draft length are a permanent characteristic of the popular and vernacular architecture and cover production and living areas. In these characteristic and unique villages of heterogeneous construction, natural earth architecture is linked to a peculiar and traditional way of life (Figure 1). In this sense, there is a notable modability of the constructions, with houses growing as an organism to adapt them to the circumstances of the resident family.

Each medieval village contains a micro-universe linked to feelings and historical memory. Consequently, each village has a unique orientation. But it is necessary to know the macro-spatial mechanisms that underlie each micro-orientation. Even villages separated by short distances of just 3 or 4 km have a different rhythm and orientation. In this area the ‘depopulation of the territory’ coexists with the ‘non-depopulation of the place’.

The ruin of public religious buildings is the ruin of the real community, in many cases replaced by the postmodern spectral community. It is the definitive end of the traditional peasant community with medieval origins around the small Romanesque construction. However, its maintenance harbors a sense of continuity since the medieval repopulation of the 11th and 12th centuries (Figure 4 and Figure 5). We admire a territory that appears to us as it did 1000 years ago. As Harvey suggests [18] (p. 197), ‘The construction of ‘community’ entails the production of such a place’.

Figure 4.

Landscape of Entresierras research area.

Figure 5.

Aldeanueva Monte church.

In the continued process of historical resistance and resilience that characterizes the micro-territorial articulation processes of the Entresierras area, it is necessary to distinguish between the causes of historical transformation until the 19th century and the contemporary causes of change. The causes of historical depopulation until the 19th century [19] were natural disasters, abusive taxes, health epidemics, traditional industrial decline, overseas emigration, confiscation laws, episodes of agricultural crises, and wars. The causes of the current decline (20th century) are lack of adequate infrastructure, rural exodus, the call effect of previous migrants, the closure of schools due to lack of students, the creation of reservoirs and the flooding of farmland, or the low productivity of the land.

Continued historical processes of change generate new nostalgic spaces of medievalism. The small spaces of villages from medieval ages associated with end territorial products result from the movement of human beings, goods, animals, water, trees, etc. through spaces and over time. Movement suggests interactions and exchange in a process of creative place making with multiple pathways of revitalization in the form of micro-spatial narrative stories and infinite minor spatial histories.

The coexistence of inactive materialities versus materialities with perspective is a complex combination of short cycles and long cycles of deteriorated materialities and rehabilitated materialities. Perspective materialities are socially and economically (pro)active materialities.

3. Methods and Case Study

The study area is called Entresierras (Table 2, Figure 2 and Figure 3), an area of gently modeled countryside at an average altitude of 1000 m, framed in the northeastern territory of the province of Segovia. It is an area of cereal agriculture and sheep farming due to the deep, clay loam soils with acceptable organic matter content. The region is characterized by having many nearby villages, about 4 km distant on average and with few inhabitants (fewer than 100 inhabitants) [20]. The settlement system has its origins in the 11th and 12th centuries, and it is a settlement system that responded to the strategies of medieval territorial repopulation. The Entresierras area is a site of colonization, transit of people, and low population. In this area, the rural exodus reached its climax between 1960 and 1970, when 17% of the population left the province of Segovia and around 120,000 Segovians left their place, mainly emigrating to Madrid [19]. In 1953, there were 85 municipalities in the area; currently, there are 56 municipalities [20].

Table 2.

Villages in the research area.

In short, a gradual process of social impoverishment occurred. The objective of establishing spatial biographies is to recover the history of the territory and the space in scale as a way of research. A homogeneous area of special medieval settlement can currently have various biographical orientations. Each village has its own particular itinerary in the context of a revitalization of materialities. Kolen et al. [21] propose that through a landscape’s narratives it is possible to notice its main biographical components. Some previous research encouraged the complexities of micro-social and territorial strategies and the itineraries or categories of the research area [2]. Now, the purpose is studying the value of micro-strategies in a small rural area through the exploration of materialities in between micro-places (medieval villages) marked by historical depopulation and cultural marginalization.

As Butlin [22] suggests, ‘The historical geography of rural land and settlement is inevitably and predictably a complex question (...) that can one be fully understood by intensive regional study’ [22] (p. 165). In the context of a postmodernist historical geography it is possible to read and observe a continuous process of development or dissolution and replacement in the place-making [23]. As Baker argues, spatial histories and micro-spaces are robust tendencies in historical geography and also in rural geography. The purpose of this orientation is to research the place histories of the changing spatial relations among and within medieval places.

The visits and reconnaissance of the towns in the Entresierras area was carried out in the summers of 2023 and 2024 (Figure 4), essentially during the months of July and August, when more houses are open. Baker [23] highlights that contemporary historical geography abandons historical interpretation in favor of a visual and spatial analysis that allows for a more adequate study of settlement systems that follow micro-territorial patterns. As Morrissey et al. [24] point out, visualizing the landscape based on key lenses is a relevant method in the analysis of past landscapes in the contemporary landscape. Landscape is a text to read for understanding the sign and significance in the historical process of continuity, change, and adaptation. Bartran [25] encourages the importance of visual imagery to substantiate claims about landscape, place, and process. The analytical process is visual imagery—cultural meaning—sign-significance—de-coding interpretation. The constructions of identity and strategies of resistance based on medieval memorials suggest a pathway of research. Probably the iconic landscape of national identity is a range of geographical settings and medieval historical contexts.

All the villages in the Entresierras area have a small population, with the exception of the medieval villages (Fresno, Maderuelo) or towns that benefited from the modernization process of the 1960s–1970s (Campo de San Pedro) or villages with recent tourist and recreational orientations (Grajera). In any case, the statistical population is not effectively the real population, which fluctuates significantly throughout the year.

4. Spatial Biographies

The medieval lands of others are historical sites of representation of the other mutants with a precise genealogy and history in time. In Duncan’s words, they are ‘spatialities times’ [26], where times of the biographies of successive others are inscribed.

Spatial biographies have three broad scales: (1) spatial biographies of whole research areas, (2) micro-spatial biographies of villages (even rural houses), (3) individual material biographies. The biographies of the entire area allow us to analyze the evolution of the medieval landscape as a whole, especially the settlement structure. Furthermore, they allow for a visual and spatial interpretation of the significant damage to the medieval historical landscape in contemporary times. The micro-spatial biographies of the villages point out possible styles of geohistorical evolution of the rural materialities. Specifically, each village has its spatial biography, and each village has its rhythm in the process of socio-territorial transformation. Some possible types in the research area are old depopulation, new depopulation, transit, slow villages, restructuring conventional, restructuring recreational–touristic, restructuring second homes (Table 3). Finally, the individual biographies of each house-dwelling allow us to point out the relevance of the ruined and forgotten traditional individual materialities, the individual materialities reconstituted for the future, and the new individual materialities in the expansions of traditional settlements (Figure 1). In any case, as Harvey encouraged [18] (p. 184), ‘The active production and making of space therefore occur through building and dwelling’.

Table 3.

Categories of villages.

Usually, the recovery of the materialities of a village is an intermediate stage for its demographic recovery. But it can also be a final scenario in some cases. Currently, a village of recovered empty houses is a possible end of the process of rural restructuring. It is necessary to understand that the confluence of the biographies of the place and the multiple biographies of the village and of the houses are fixed; that is, they develop in a location, and only the biographies of the people are spatially mobile. A village of empty material biographies requires a future coincidence with mobile personal biographies. The fixed and mobile biography is reproduced in states of stability–instability until the permanent stability that is acquired by the fixity of the mobile biography. Fixed biographies can simply be shaped. In this way, we have three biographies that play a game among themselves: place, house, and people. The aggregated materialities and the individualized materialities acquire a differentiated rhythm with their inhabitants in each village and between villages. A recovered materiality is a static materiality for a long period of time with an indeterminate end. The ruined materiality is an unstable materiality waiting for its recovery and occupation by new inhabitants. Ruined materials are now only a punctual and marginal reality in the villages of the study area.

Landscape Memory, Social Groups, and Associated Identities

Landscape as live, landscape as cultural nature, and landscapes of work are the three dimensions that coincide in a medieval village restructured by a contemporary process. In any case, it is possible to ask: Do all the peoples of a territory emerge at the same time? Do all the dimensions of the medieval landscape emerge coincidentally? Palang, Soovaliy, and Printsmann [27] point out an interesting difference between ‘Persistent landscapes’, ‘Landscapes of lives seasonality’ and, finally, ‘Await landscapes’. Seasonality, expressed both in the natural rhythms of the landscape as well as in the human lifestyle, is a characteristic of the study area. The new or old localized social and cultural landscapes are the texture of the social world [28]. The landscapes in the Entresierras area have persisted since the Middle Ages in their basic characteristics (Figure 3 and Figure 4); they have a social seasonality and await the closing of the cycle of the process of rural change through the recovery of the last untransformed ruins and the stable permanence of a part of the seasonal residents (Figure 1).

‘Landscape is experienced in countless ways by all human beings, both individually and as members of communities, nations and humanity as a whole’ [29] (p. 635), but it is possible to distinguish two points of view from a geohistorical perspective, according to Lowenthal [29]: ‘living with’ is regarded as a virtue, ‘looking at’ as a scenic appreciation. Virtue and scenic are two characteristics that complement each other and give rise to biographies and itineraries in medieval historical landscapes. The landscapes affected by historical processes of depopulation have their own interpretive keys (Figure 5). These emptying landscapes suffer scenic and social transformations in Europe [29]: rural life in recent memory, rural life is long gone, rural life persists. These three dimensions of rural lives are associated with the processes of social change of a vertical nature (associated with local populations) or of a territorial nature (associated with new populations) with the strength of traditional populations and with the processes of material renewal. Although there are global trends in micro-territories, each village has its own dynamics and orientation. In recently restructured medieval settlement areas, ‘Fluctuational memories’, which promote and define emerging properties as determinants of change, are very relevant [30,31]. In the words of Harvey, ‘History and memory in places are quite distinct from one another’ [18] (p. 179).

Medieval landscapes contain, in the form of continuous processes, ‘Contested landscapes’ and ‘Landscapes of continuity’ that coexist territorially (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). These historical landscapes express successive situations of resilience and spatial resistance. Scott [32] suggests that there are two approaches to resilience: balance to the previous situation and adaptation to a new scenario. In any case, balance and adaptation coexist as two forces in the continuous gestation of medieval landscapes and in the historical evolution of each medieval village. The vision of resilience as a process that interacts evolutionarily with situations of resistance also allows us to address the historical analysis of medieval villages [33]. Resilience processes are broad in historical situations prior to the 19th century, but contemporarily, they have increasingly shorter alternatives in time with resistance processes, given the intensity of the rural change processes. Materialities have their own dynamic of resistance to change processes, which can be parallel with social processes but which maintains its own rhythm [28].

In medieval villages, there is also a symbiosis of singular materialities (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Some common examples are the Olma as a vegetal materiality (Figure 6) and the medieval Romanesque church as an essential stone materiality. As Heidegger [30] already pointed out, the work of art opens the world, and the material and vegetal landmarks in a small village are like works of art toward the world. Following this author, the discovery of space, emancipating itself, is a process from the place to the site with its appropriate dimensions. The priority in the construction of a place offers the spatiality of the surrounding world. The formal intuition of space discovers and offers possibilities of spatial relationships, especially in landscapes that hold keys to their medieval historical construction. Giving space or spacing is a constant characteristic of medieval repopulation and colonization. The external world of the medieval inhabitants was being before the eyes, a ‘being there with’ or being of the world; ‘being of space’ contains several phenomenal spatialities, and medieval space is a spatiality at the hand of extensive things before the eyes, which is currently visually maintained on many hilltops as it was a thousand years ago (Figure 4). The open and pure space where there is an order of places and a determination of metric positions is the phenomenon of the place [30] (p. 126), which can be read perfectly in the landscapes and sites of medieval colonization. We can see what the ancient and first settlers of the Entresierras area saw, which allows us to imagine places and routines from another era.

Figure 6.

Barahona Fresno church.

5. Styles of Village Materialities

There are multiple exit models in the depopulated and remote rural areas of the restructuring and revitalization process. Two major options coexist: (1) the locational model (based on recovering materialities) versus (2) the population model (recovering people in statistics). Creative place-making through recreational individual or collective solutions on site is a conventional solution in these rural areas in decline. In any case, ‘Place based community entails a delicate relationship between fluid spatio-temporal processes’ [18] (p. 199).

Interactive places in a network in the form of one territorial destination end up coexisting with a singularity of place in the form of itinerary. Each place has a small history. The spatial biographies of villages’ materialities host multiple styles: (1) Slow is the most common in the study area; suitable examples are Turrubuelo, dominated by small lives, or Bercimuel, which expresses a pleasure reconstitution or reconversion. In this style, value is given to the small, the value of the medieval village is exalted, and the discreet value of everyday stillness is experienced (Figure 7). (2) Latent towns are associated with new depopulation—Castiltierra is a good example of modern depopulation—where there is no permanent and/or statistical population, but all the houses are renovated and used seasonally. (3) Decline is associated with old depopulation and contemporary critical transit; Aldeanueva Monte or Barahona (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) are towns that still experience the effects of depopulation in their material and social reality. Many rural houses are ruined or have not transitioned from their traditional rural or agricultural functionality. The process of rural change is in an initial phase, but its foreseeable future will be the slow category. (4) Riahuelas, where ancient and modern processes coexist (old/new or modern/traditional) (Figure 8), have a stable agrarian population base that is strongly expressed in the materialities of the town but that coexists with other realities of new residents or seasonal residents. Finally, there are three types of restructured villages: (5) conventional, with a rural restructuring process based on new residents and new industries, which merge with service activities; (6) touristic emblematic or scenic in villages of monumental character such as Maderuelo (Figure 8), which recalls its traditional medieval character in its tourist and residential strategy; and (7) touristic second homes, in towns where there have been contemporary expansions of second homes directed to new seasonal urban residents, but which have also enabled the emergence of a new, stable local society (Table 3).

Figure 7.

Alconada of Maderuelo.

Figure 8.

Riahuelas stables.

Spatial stories exist in everyday organized places, in multiple spatial trajectories and modalities [34]. This perspective points out that every village story is a spatial practice with everyday tactics in the form of territorial expressions. Other characteristics are (1) bipolar distinctions between map and itinerary, (2) frontiers and bridges between places, (3) place(s) coexistence in the same location, (4) spaces as intersections of mobile elements.

Only the restructured villages have a population of more than 100 inhabitants, especially those that have had a tourist–recreational orientation such as Grajera, which had 256 inhabitants in 2023, and Fresno, which had 303 inhabitants in 2023. On the contrary, old depopulation villages have a population of around 10 inhabitants and are administratively dependent (Figure 5). Slow social and material life villages have sizes between 10 and 50 inhabitants. The slow category brings together most of the villages (Table 3) (Figure 7); they are towns with many seasonal residents who have recovered the materialities but with little statistical or permanent population. On the other hand, old depopulation villages are small villages with a very low population, affected by traditional depopulation, with ruined or missing traditional materials and few renewed materials (Figure 1). New depopulation villages are an extreme variant of slow villages: recovered houses without permanent residents and ruined emblematic materialities. Statistically, they are depopulated, without materially having that condition.

A special case is the special biography villages with special biographies based on the construction of an alternative residential landscape. They are peoples with biographical leadership framed in dispersed societies (but in small places) compared with concentrated societies (but in large cities). An example in the study area is Grajera. Dispersed and mobile daily lives characterize declining rural areas, where each person must find their place dispersed in the territory. They are villages marked at the same time by the actions of a mayor with interests in the construction of new materials—extensions of low houses—who guides the village toward a usually recreational–tourist vocation that attracts new urban populations.

All the centers preserve original urban structures; there are numerous examples of well-preserved houses between party walls and restored houses. In this sense, there are no major alterations in the original configuration of the medieval population centers. In the location of the settlement there is a notable influence of the river banks and flooded areas to obtain natural adobera land. The adoberas—adobera is the place in the village where adobes were made, used for the traditional construction of houses—are in depressed areas of the population itself [35]. The natural land indicates traditional self-sufficiency and a way of life where all resources are available in the localities themselves. Adobe techniques are more developed in the central areas, but where access to natural earth is more limited, adobe is a secondary construction element to stone. In the study area, there are also villages where the natural land is secondary with a limestone (masonry) façade (e.g., Alconadilla or Barahona del Fresno) (Figure 1). Usually, this is limestone of a different color based on the substrate (Figure 9). In vernacular architecture, they use stone in all the perimeter walls, covered with natural earth and lime. Within the limits of the localities, haylofts, sheds, pigeon coops, winery neighborhoods, and orchards with masonry walls are exempt. Productive buildings are practically non-existent due to changes to residential use or deterioration and abandonment. The sunken roofs and specific material ruins in a group of recovered houses stand out.

Figure 9.

Maderuelo village.

As previously noted, almost all the villages are in the ‘slow’ category (Figure 7), and all have small village expansions: (1) They may be established on the previous build space, occupying plots of productive agricultural buildings. (2) Other villages expanded and merged with the build area prior to the traditional build area. (3) In other cases, they established small expansions differentiated and demarcated from the traditional core. In any case, the place formation is an active and permanent process, but the ‘Question of how to define the ‘authentic’ qualities of ‘real places’’ [18] (p. 197) is relevant.

6. Conclusions

In this study, the complex intersections and autonomies by type of village in a territory are analyzed. The dynamic of biographies of medieval villages allows us to build a typology of villages: Few old and new depopulated villages, many slow villages, and some restructured in a recreational way. Appropriating the medieval communities in the social memory of the area is a common characteristic. The non-existence of more processes of resettlement and land tenure organization from the medieval age is a notable singularity in the organization of the research area. The very close settlements limited any growth of each village and peasant community. In short, the medieval occupation and organization of the entire rural space occurred at the time of medieval colonization due to the proximity of the villages and the initial density of the settlements.

In the case of medieval settlements, is it possible to find multiple processes in a permanent renegotiation of communities in place and out of place? A key question is, how are communities renegotiated? The answer has two dimensions: horizontal or geographical and temporal or geohistorical. Potential alternatives and future lines of inquiry around the community capital and multifunctionality are suggested for geographical analysis [36].

But the concept of community and multifunctionality are in discussion at the end of the process of rural restructuring in medieval materialities. Peripherality, dissociation, outsiders, and multiple histories in a marginal area suggest that marginality is a deliberate choice to shield creativity from the mainstream [37].

Villages are a dynamic and fluid cultural object, continuously reflecting the socioeconomic context of each historical period and society’s ability to transform it. Cultural objects act as intermediaries that condition the ways in which each person or group of people interacts with their environment and establishes their place in the site in the form of medieval micro-encounters.

Beauty is not a quality of the materiality of the village and the rural environment, but rather, depends on the subjective experience of the observer, shaped by the culture of the historical era in which it develops and, consequently, it is fluid, unstable, and evolutionary. It is a medium through which ideas, emotions, and realities that are part of the life of a certain place are expressed. The current result of settlement in the Entresierras area is a combination of bad materialities (damage in the territory as the product of new residential settlements), good materialities (material medieval villages), and prestigious materialities (sacred medieval materialities). Participatory methods that prioritize the insights of rural people in landscape–scenic resource-based economies are a key option for the future.

Is the problem of the villages discussed in this paper a common problem in the global perspective? No, it is a problem only in countries with historical depopulation processes. Issues such as the rural depopulation and the preservation and reuse of rural historical heritage are also important issues in some developing countries in Western and Central Europe. The research framework proposed in this paper is applicable to other countries with processes of historical depopulation and rural restructuring, mainly in Western and Central Europe.

In any case, the preservation of the entire landscape of medieval settlement offers a wealth of plural nuances for the territory in the context of the global sustainable development processes that have different micro-orientations in specific areas. The preservation of these landscapes with medieval roots must be an objective of sustainable development in countries with historical depopulation with active processes of social and material revitalization.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

References

- Cloke, P.; Little, J. Contested Countryside Cultures; Rurality and socio-cultural marginalization; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, A. The politics of place: Official, intermediate and community discourses in depopulated rural areas of Central Spain. The case of the Riaza river valley (Segovia, Spain). J. Rural Stud. 2009, 25, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. The lost life of a historic rural route in the core of Guadarrama Mountains. Madrid (Spain). A geographical perspective. Landsc. Hist. 2017, 38, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, P.L. Built Environments. In International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladero Quesada, M.A. La Formación Medieval de España; Territorios, regiones, reinos; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Olivera Serrano, C. La Reacción Almorávide. In Historia de España de la Edad Media; Alvarez Palenzuela, V.A., Ed.; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Valdeon Baruque, J. Las Raíces Medievales de Castilla y León; Ámbito: Valladolid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Albornoz, C. Despoblación y Repoblación del Valle del Duero; Universidad de Buenos Aires: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Mitre, E. La España Medieval; Istmo: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oosthuizen, S. Medieval settlement relocation in West Cambridgeshire: Three case-studies. Landsc. Hist. 1997, 19, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdeon Baruque, J. La Reconquista. El Concepto de España: Unidad y Diversidad; Espasa: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, B.F. Reconquista y Repoblación de la Península; El País: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Valdeon Baruque, J. Personalidad Histórica de Castilla en la Edad Media. In Introducción a la Historia de Castilla; García, J.J., Lecanda, J.A., Eds.; Ayuntamiento de Burgos: Burgos, Spain, 2001; pp. 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Isla Frez, A. La Alta Edad Media. Siglos VIII-XI; Sintesis: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Minguez, J.M. La España de los Siglos VI al XIII. Guerra, Expansión y Transformaciones; Nerea: San Sebastián, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- García González, J.J. Castilla en tiempos de Fernán González; Dossoles: Burgos, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oye, I. Settlement patterns and field systems in Medieval Norway. Landsc. Hist. 2009, 30, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Cosmopolitanism and the Geographies of Freedom; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arranz, J.V. Abandonados; 10 eco-rutas por los pueblos abandonados de Segovia; Caja Segovia: Segovia, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- CODINSE El Nordeste Segoviano: Una Comarca Camino del Desarrollo; Caja de Segovia: Segovia, Spain, 1997.

- Kolen, J.; Renes, H.; Hermans, R. Landscape Biographies; Amstedam Univeristy Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Butlin, R.A. Historical Geography Through the Gates of Space and Time; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A.R.H. Geography and History. Bridging the Divide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, J.; Nally, D.; Strohmayer, V.; Whelan, Y. Key Concepts in Historical Geography; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bartran, R. Geography and the interpretation of visual imaginery. In Key Methods in Geography; Clifford, M.J., Valentine, G., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2003; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, J. Sites of representation. Place, time and the discourse of the other. In Place/Culture/Representation; Ducan, J., Ley, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Palang, H.; Soovaliy, H.; Printsmann, A. Seasonal Landscapes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, A. Old, lost and forgotten rural materialities: Old local irrigation channels and lost local walking trails. Land 2022, 11, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. Living with and looking at landscape. Landsc. Res. 2007, 32, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. El Ser y el Tiempo; FCE: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 1989; original edition in the year 1927. [Google Scholar]

- De Landa, M. Mil Años de Historia No Lineal; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M. Resilience: A Conceptual Lens for Rural Studies? Geogr. Compass 2013, 7, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Challenges and pathways in sustainable rural resiliencies or/and resistances. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz de la Calle, D. El Uso del Adobe en la Arquitectura Tradicional Segoviana; Pasado, presente y futuro; Diputación de Segovia: Segovia, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, G.; Carson, D. Resilient communities: Transitions, pathways and resourcefulness. Geogr. J. 2015, 182, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.C. Medieval rural settlement: Changing perpections. Landsc. Hist. 1992, 14, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).