Abstract

Resource consumption, global greenhouse gas emissions, and their effects on human health have pushed the food sector to produce novel foods such as cultured meat. Cultured meat could respond to the demands for sustainable transformations in the food sector; however, are consumers ready to change their eating habits? This research analyses consumer perceptions of cultured meat by linking it to quality, health, sustainability, and socio-economic aspects. The study adopts a qualitative approach, and through in-depth interviews, explores Italian consumers’ perceptions of cultured meat. The findings show how cultured meat is perceived as a sustainable alternative that safeguards the environment, natural resources, and animal welfare. However, the research highlights the need for more information on the production phase of this novel food. Research into the hazards and risks of cultured meat is essential to confirm its safety. Indeed, further research and investments are needed to obtain information on the safety and reliability of this new food. The respondents feared introducing this new food as it could damage the actors involved in the agri-food chain by reducing jobs, and they were not inclined to abandon their culinary traditions. The results suggest to companies and governments which aspects to optimize and which factors to invest in to communicate with consumers.

1. Introduction

The Food and Agriculture Organization has predicted that 70% more food will be needed by 2050 to meet the demands of the growing population in light of resources and arable land limitations [1,2]. Considering this challenge, more efficient ways of producing proteins are being developed to support the growing global population while respecting environmental and animal welfare issues [3]. Among the solutions, in recent years, cultured meat has become increasingly widespread [4,5]. Cultured meat, or in vitro or cellular meat, is an example of a novel food made through advanced biotechnological techniques. The process involves the collection of animal cells, typically through a noninvasive muscle biopsy, which is then grown in a controlled environment to produce meat [6,7]. This novel food represents a sustainable and safe health alternative for consumers [8]. Cultured meat is produced in controlled, bacteria-free environments with limited human–animal interaction, which would improve health and safety, reducing the risk of food poisoning and contamination [9,10]. However, other studies show that cell culture is never perfectly controlled [11,12]. Cultured meat is already available in the United States and Singapore, and European governments are investing in its development. Singapore was the first country to approve the sale of cultured meat to consumers in December 2020. In June 2023, the United States became the second country to approve its sale. In 2022, European cultured meat companies saw investments increase by 30% to €120 million [13].

Sinke et al. [14] highlight how cultured meat can have a lower environmental impact than conventional meat, in particular on the use of agricultural land, air pollution, and nitrogen-related emissions. For example, the study conducted by Tuomisto, Ellis, and Haastrup [15] shows how cultured meat would require less water (82–96% less), produce fewer greenhouse gases (78–96% less), use less energy (7–45%), and would require less land consumption (less than 99%) than conventional meat production. Furthermore, this type of production helps reduce environmental and ethical problems associated with animal farming [16]. Improving food security is a priority across Europe, as wars, climate change, and supply chain vulnerabilities can cause inflation and food shortages. Cultured meat is expected to be up to 5.8 times more efficient at converting raw materials into meat—so it could help reduce Europe’s dependence on food imports, feeding more people with fewer resources. Italy imports most of the meat it consumes and has a self-sufficiency rate for beef of 42.5% [17]. Supporting domestic cultured meat production could help close this gap. According to research conducted by Mancini and Antonioli [18], more than half of Italian consumers declared themselves to be interested in purchasing it once it was available in Europe. Consumers are pushed to change their eating habits to combat animal cruelty and environmental externalities [19,20].

However, cultured meat’s production and marketing in Italy have been banned. Several studies have highlighted [11,21] that despite the numerous benefits that cultured meat can offer, the aspects that affect the acceptance of this novel food are the availability and accessibility of information on cultured meat [22,23,24,25].

However, the existing literature indicates a dearth of studies on Italian consumer perception of cultured meat [20,26]. The acceptance of cultured meat varies from country to country and is linked to the different perceptions of benefits compared to risks. The interest in Italy stems from the fact that many consumers consider meat consumption as an integral part of their food culture and tradition [27,28,29,30].

The success of cultured meat depends on consumer behavior [31]. Therefore, understanding consumer acceptance of cultured meat is crucial [32], especially regarding its quality, safety, health, and sustainability [33]. Research can help identify the factors that motivate consumers to purchase and consume cultured meat, providing insights into how to encourage consumers to consume sustainably. In light of this, the authors, through a qualitative analysis, delved into the perceptions of Italian consumers on the diffusion of this new food and explored their viewpoints on quality, sustainability, ethics, and socio-economic aspects linked to the production of cultured meat. The following research questions are what this paper aims to address:

(RQ1) What are Italian consumers’ perceptions towards cultured meat compared to traditional meat?

(RQ2) Quality, health, sustainability, and socio-economic aspects: what are the challenges of cultured meat for Italian consumers?

(RQ3) How can we optimize the acceptance of cultured meat for Italian consumers?

The findings of this research offer valuable insights and recommendations to companies and governments on which aspects to optimize and which factors to invest in to communicate with consumers effectively.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 explains the qualitative methodological approach adopted, namely the in-depth semi-structured interviews with Italian consumers, which were analyzed through content analysis; in Section 3, the authors analyze the existing literature on cultured meat and consumer acceptance. Section 4 presents the benefits and risks of cultured meat and shows how cultured meat is perceived as a sustainable alternative that safeguards the environment, natural resources, and animal welfare. Section 5 suggests to companies and governments which factors to invest in to communicate with consumers and the need to provide more information on the safety and reliability of this new food. Finally, the last section concludes the work, highlighting limitations and future research perspectives.

2. Literature Review

Consumer acceptance of cultured meat is a subject of growing academic interest. Several studies have identified barriers and factors that influence consumers. The market success of this novel food depends on consumer acceptance [34]. It is therefore crucial to investigate consumers’ perceptions of cultured meat and their willingness to consume it [35]. Several studies [17,36,37] suggest that the main perceived benefits are animal welfare and environmental benefits, followed by personal benefits, such as health and food safety. Environmentally conscious consumers are more likely to adopt cultured meat, considering its potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and use of raw materials compared to traditional livestock farming [36]. The production of cultured meat would return natural resources and arable land used for meat production [38], significantly impacting agriculture and the environment. This new production approach could free up land for more sustainable and nutritious crops, reducing environmental pressure and contributing to food security [39,40]. Ethical concerns also play a decisive role, particularly among consumers who are concerned about animal welfare but still want to consume meat [41].

Previous studies have also confirmed that acceptance of cultured meat is influenced by various sociodemographic characteristics, such as gender, age, income, and education [16,42,43]. It has been found that younger consumers and those with higher levels of education are generally more receptive to cultured meat [41,44]. In contrast, older generations, who grew up with traditional food systems, may be more reluctant to introduce this novel food [45]. Cultural factors [46,47], such as tradition, religion, technological trust, and food safety concerns, also significantly influence the acceptance of cultured meat. Introducing cultured meat in countries with strong meat-eating traditions, such as Italy, challenges culinary customs [36]. Religion may also influence consumers’ attitudes towards cultured meat. Some consumers may accept cultured meat if it adheres to specific ethical standards and rituals, while others may reject it due to its artificiality. Conversely, for others, cultured meat may be a more ethical choice as it does not use violence towards animals [48]. In countries with food shortages or high meat production costs, cultured meat may be perceived as an opportunity for nutritional security [49].

Consumers’ main concerns include naturalness, taste, safety and cultural acceptance, and uncertainty about safety and health [50]. Many consumers view cultured meat as an artificial product due to a lack of knowledge about its production. They may, therefore, express concerns about potential long-term health effects and safety [47]. Another significant barrier is taste and sensory expectations: conventional meat sets a high standard for texture and flavor, and consumers may be reluctant to switch if cultured meat does not match or exceed conventional options [50]. Nutritional values and food safety are also issues to consider. Conventional and cultured meat provides high-quality protein and essential nutrients, but cultured meat offers potential improvements in fat composition, cholesterol levels, and food safety. While traditional meat carries inherent risks due to bacterial contamination, antibiotic use, and zoonotic diseases, the controlled production process of cultured meat reduces these risks [36,49,51,52].

Furthermore, price sensitivity is a crucial factor, as studies indicate that many consumers are unwilling to pay a premium for cultured meat, especially in its early stages on the market [51]. Furthermore, the lack of clear regulatory frameworks in many countries can contribute to uncertainty and hesitation among consumers, who often rely on government approval to indicate safety and legitimacy.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

An exploratory, inductive research design was planned to explore Italian consumers’ perceptions of cultured meat. The authors conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews to allow for open-ended responses [53,54]. Considering the purpose of the inquiry, qualitative inquiry, which is flexible, intelligible, and accessible, was the most appropriate methodology, as it can provide detailed insights into the research topic [55,56]. During May 2024, 34 face-to-face interviews were conducted, each lasting 40–60 min. Based on the literature review, the interview outline comprised 5 sections with 22 questions. The interview outline is presented in Appendix A. The first in-depth topic was consumers’ perceptions of the future food to identify its advantages and disadvantages. Following this, traditional vs. cultured meat was explored in depth, examining how many interviewees were attentive to environmental and health issues, their opinion on cultured meat, and the ban on selling it in Italy. The third section of the interview focused on the quality of cultured meat [57], exploring whether consumers considered this novel food healthy and safe and whether the production process was reliable. Subsequently, it was analyzed whether introducing this new food would solve the problems related to food security, hunger, and nutrition, as well as how it could benefit the well-being of the individual/community and promote sustainable development. Finally, the last section focused on socio-economic aspects; in detail, the interviewees were asked how introducing cultured meat could influence the agricultural sector and put traditional culinary culture and the Made in Italy food supply chain at risk.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The interviewees were selected through a snowball approach [58,59,60]. A pilot interview was conducted to test the questions’ and topics’ effectiveness and validity. Following the principles of data saturation [61], 34 interviews were conducted. The authors stopped at 34 interviews, as no new significant information emerged [62,63].

The interviews were transcribed [64], and two researchers, using the MAXQDA18 textual analysis software, analyzed and coded the results of the interviews, eliminating bias and subjective interpretations [65,66,67]. Similar concepts were codified and grouped into categories, and the key issues were identified. These results were compared, followed by a discussion of the items that showed a lack of convergence and adequacy fit of the conceptual classifications [68]. The results are presented through frequency tables and quotations extracted from the original text [69] and summarized with a cognitive map [70,71,72,73].

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The sample comprised 34 interviewees, of whom 20 were male and 14 were female. Most respondents were in the 18–25 age range (17 interviewees), followed by 11 consumers aged >56 years. The other age ranges recorded the following frequencies: 26–35 years with three respondents and 36–45 with three respondents. Regarding educational background, 15 respondents had a diploma, 11 had a master’s degree, and seven had a bachelor’s degree. The majority of the sample comprised students (18) and private-sector employees (9). A total of 28 respondents followed the Mediterranean diet, three consumers followed a protein diet, one respondent was vegetarian, and two respondents were celiac and had allergies. Furthermore, the analysis of the sample highlighted the following weekly meat consumption: 1 time (2), 2 times (1), 1–2 times (8), 2–3 times (11), >3 times (11), and never (1). Therefore, the sample interviewed had a large consumption of traditional meat.

4.2. Qualitative Results

The authors analyzed the interview results, focusing on each dimension of the interview through quotations and frequency tables on the key topics raised.

First, the authors explored the consumers’ perceptions of the future food (I) and traditional vs. cultured meat—definitions and expectations (II). and then subsequently focused on the quality of cultural meat (III) and its connection with the themes of sustainability and ethics (IV) and the socio-economic aspects (V).

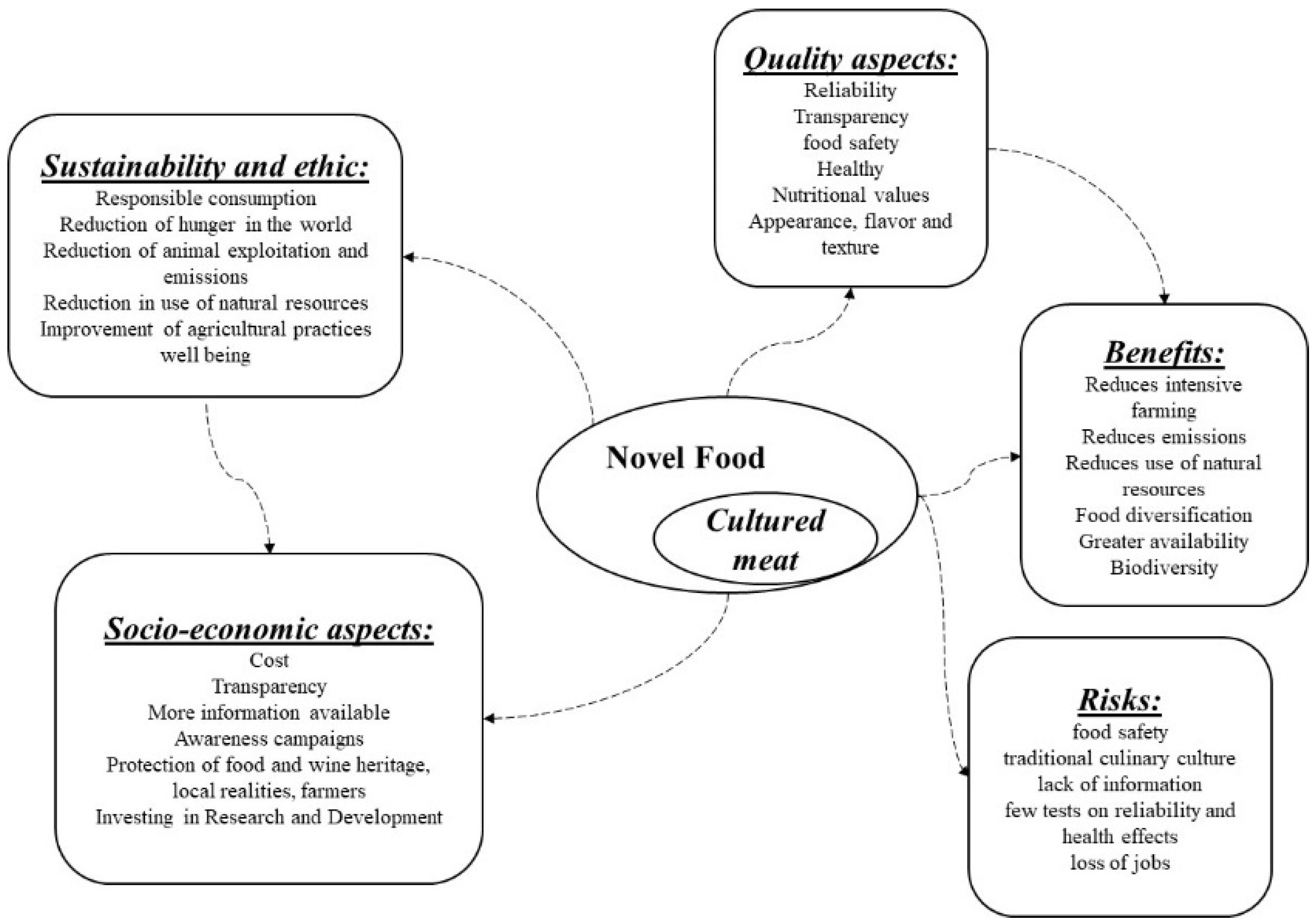

Finally, a cognitive map was presented to summarize all the qualitative results that emerged [51] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cognitive map (source: authors’ own creation).

- I.

- Consumers’ perceptions of the future food

The results highlight a rich tapestry of perspectives on the concept of food of the future. Respondents identified insects (18), cultured meat (12), and cricket flour (10) as potential foods of the future. Many respondents considered these new foods sustainable, with minimal environmental impact and innovation (16). However, for some respondents, these new foods represented a challenge for the Italian market (10), as they are linked to typical culinary traditions. At the same time, other consumers considered them risky foods due to the scarcity of information on their production process (8). Interestingly, some believed these new foods were safe (12) and healthy (13), while others labeled them as artificial and chemical (13). Table 1 shows the benefits and risks associated with the new foods that emerged from the interviews.

Table 1.

Benefits and risks of the future foods (source: authors’ own creation).

Among their advantages, these future foods could contribute to more sustainable food production, reduce the environmental impact (greenhouse gas emissions), and use natural resources such as land, water, and energy. Furthermore, most interviewees highlighted that introducing cultured meat, for example, would eliminate animal exploitation and promote livestock welfare. The interviewees believed these new foods could improve health, reduce the incidence of diet-related diseases, and contribute to global food security as there is greater traceability. Introducing these new foods could contribute to lowering famine and pursuing Goals 1 and 2 of the 2030 Agenda to defeat poverty and reduce hunger in the world. Among the disadvantages were doubts about the health effects of these new foods, the loss of culinary traditions, and their different aspects, flavor, and consistency compared to traditional food. The interviewees also identified the cost and poor food safety among the risks; the consumers considered some of these future foods to be finished/unnatural as they are produced in laboratories, and the consumers were therefore not sure of the quality and reliability of the raw materials used. What also emerged was the risk of job losses and the awareness of those interviewed that only large multinational companies could adopt these very innovative production processes.

For most of the respondents, these foods contribute to sustainability through the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the more efficient use of natural resources, and the promotion of animal welfare through the reduction of intensive farming.

“They contribute to pursuing sustainability because less use of fertilizers and less exploitation of animals (intensive farming) is expected; furthermore, these new foods would make it possible to satisfy the needs of the entire world population”.

“These new foods allow us to save resources. Furthermore, they do not involve intensive exploitation of the soil and do not require enormous quantities of water”.

Furthermore, these new foods would make it possible to satisfy the needs of the entire world population and save natural resources.

“I’m not sure if these new foods are sustainable. The production of some of these future foods still requires a lot of resources and energy so that they may have a similar or worse environmental impact than traditional foods”.

However, some respondents were still determining the real sustainability of these novelty foods as their production requires high investments and natural resources (i.e., energy and water).

“In my opinion these novelty foods do not contribute to sustainability, both for a question linked to costs and for a question linked to distribution”.

The analysis shows that the respondents knew about novel foods, highlighting their benefits and risks for the environment, health, and the economy.

- II.

- Traditional vs. cultured meat: definitions and expectations

Most of those interviewed (28) considered themselves attentive to the problems associated with the treatment of and respect for animals, highlighting the need to raise awareness and inform people about intensive farming and how animals are treated to protect them.

All the respondents thought that consuming conventional meat could negatively affect the environment due to its implications for deforestation, water and energy use, and greenhouse gas emissions. However, one respondent highlighted that there are sustainable farming models that apply principles of animal welfare, environmental protection, and efficient resource use. According to 30 respondents, conventional meat is healthy but in moderation. Meat is a protein source that is part of a balanced diet, but choosing meat sources from sustainable and ethical farms is essential. However, according to four respondents, traditional meat is harmful to health as it generates diseases. According to those interviewees, individuals who follow diets rich in animal proteins, especially red and processed meats, have a higher risk of developing diseases such as diabetes, heart attacks, cardiovascular problems, obesity, and cancer [74].

The interviewees considered cultured meat a non-natural/artificial food that pursues sustainability and innovation. However, some feared introducing this new food due to uncertainty about the production phase and food safety.

“Cultured meat is utopia, sustainability and innovation. It will hardly enter everyday life as prejudices and uncertainties will prevail. It is a food that will need to be advertised, raise awareness, and have a reduced price. It will be a food that will hardly enter the market and be consumed by the current society”.

As Table 2 shows, the advantages, according to the Italian interviewees, of the introduction of cultured meat are environmental, as it would lead to a reduction in emissions and use of natural resources (21), a reduction in intensive farming (19), greater product availability (3), more food safety (3), and would also encourage continuous research.

Table 2.

Cultured meat advantages and disadvantages (source: authors’ own creation).

Among the risks, however, uncertainties emerged regarding the effects on health, as cultured meat is a new food that needs to be tested and perceived as poor quality. Furthermore, it hinders the economy and the security of the Italian agri-food heritage, reducing the workforce in the food sector. The introduction of this new food would distance Italians from culinary tradition. Furthermore, high costs are required to produce and purchase cultured meat.

Italy is the first country in the world to have banned the production and marketing of cultured meat. Below are some opinions expressed by those interviewed:

“Italy has taken a precautionary stance towards cultured meat, considering food safety and the impact on the traditional industry. It is a choice to protect the country’s economy and the farmers and meat producers”.

“Italy has chosen to ban the production and marketing of this product to carry out further studies and checks before putting it on the market”.

“I think it is right to ban production because there is insufficient information and certainty. It could ruin Italy’s agricultural economy, and there are no guarantees about the effects it may have on consumers in the long term”.

The respondents were asked whether they would be willing to consume cultured meat. The sample appears divided: 17 individuals would not be willing to consume it because they had little information about the product and little confidence in its effects on health; instead, the remaining respondents would try it out of curiosity (11) and to preserve animals and the environment (7).

“I might be willing to consume cultured meat if it were safe and sustainable. I would be encouraged to buy it if it could help reduce the environmental impact and animal suffering”.

“I am curious; I would like to try it to test the taste and quality of the product”.

“I would buy it when the price is advantageous; otherwise, the traditional one would be better”.

The respondents willing to try it (nine males and eight females) fell within the 18–25 and 26–35 age groups, and they consumed traditional meat on average two times a week. Among the respondents willing to try cultured meat was the only vegetarian respondent, who said he would like to try it out of curiosity and to reduce animal suffering.

The results confirm that young people, compared to older people, are more willing to change their dietary habits to reduce environmental impacts and see cultured meat as a potential solution to limit deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions [36].

Thus, the respondents perceived cultured meat as an alternative that could help reduce emissions and use of natural resources and improve animal welfare. However, having little information about the production stages of this food, the respondents had doubts about the effects on their health and the economic consequences.

- III.

- Quality of cultured meat

The respondents were asked to express their expectations regarding the quality of cultured meat. According to most respondents (20), cultured meat could be considered high quality.

“If produced following rigorous protocols, cultured meat could be considered high quality. It is essential to ensure that the production process is safe, transparent, and meets quality and nutritional standards. However, it is important to conduct further research and evaluation to confirm its long-term quality and safety”.

Still, it is necessary to have more information on the production process and ensure that it is safe, transparent, and complies with quality and nutritional standards. The need has emerged to conduct further research and evaluations to confirm the quality and safety of this new food (5): “I’m not sure about the reliability of cultured meat. I have doubts about food safety, I don’t think it is a reliable and safe product”.

Furthermore, being created in a laboratory, the flavor and appearance would be perfectly controlled to be a quality food (3). However, others thought the taste would not be similar to traditional meat (6).

“I don’t think cultured meat can reach the quality of conventional meat. It is difficult for a cultured product to have a taste similar to that of traditional meat”.

Most respondents did not consider cultured meat a safe and healthy food as there is little information on how it is prepared (25). According to nine interviewees, however, cultured meat is made in a laboratory and subjected to various standards and quality controls to guarantee its purity and absence of contaminants.

The nutritional composition of cultured meat may be designed to be similar to that of traditional meat, but it may vary depending on the manufacturing process and ingredients used. In general, cultured meat could be a similar source of proteins and nutrients to traditional meat, as it is still produced from animal stem cells (15). However, according to 16 respondents, cultured meat does not have the same nutritional properties as traditional meat.

Furthermore, the sample was divided regarding the flavor and texture of cultured meat compared to traditional meat. For 18 respondents, cultured meat could not match cultured meat as it would have a different flavor and texture. Instead, according to 14 consumers, cultured meat could match the flavor and texture of traditional meat. According to two respondents, cultured meat could match the taste of conventional meat but not the texture. The cultured meat production process could be considered reliable if strict production and quality control standards were followed. Measures must be taken to ensure the safety and reliability of the final product (17). Further analysis and more information on this new product are necessary to verify whether the production process is reliable and transparent (14). The transparency of the cultured meat production process depends on the manufacturing company’s approach and current regulations. Ideally, companies should provide clear information about the manufacturing process, the ingredients used, and the safety tests carried out to ensure consumer trust.

The results highlight the need for the respondents to have more information on the reliability, transparency, and food safety of synthetic meat, also considering its nutritional values, taste, and texture compared to traditional meat.

- IV.

- Cultured meat: sustainability and ethics

According to those interviewed, introducing cultured meat would solve the problems related to hunger and nutrition as it would represent an additional source of protein and be more readily available even in places where crops and food were lacking (16).

“Cultured meat could help solve some of the problems related to food security, hunger, and nutrition. Being produced in a laboratory, it could be less subject to bacterial and viral contamination than traditional meat. Furthermore, its production could be more efficient regarding resource use, allowing greater food availability for the world’s population”.

However, others argued that this new food would not reduce world hunger, considering the high costs of production and sale (12). The remaining respondents (6) considered cultured meat not a solution to world hunger but a tool that could provide an additional source of dietary protein, especially in regions with food shortages. As Table 3 shows, the respondents were asked whether this new food promotes the well-being of the individual/community.

Table 3.

Cultured meat and well-being (source: authors’ own creation).

For most respondents, it did not; according to 10 respondents, introducing this new food reduces pollution, safeguards the ecosystem, and gives greater access to food, thus improving collective well-being.

“It could promote individual well-being by helping to reduce the risks of animal-borne diseases and improve their well-being by reducing the need for intensive farming”.

“The introduction of cultured meat could promote the well-being of individuals and communities. For example, it could offer a safer and more sustainable source of protein, reducing the risk of diseases linked to consuming contaminated meat. Furthermore, reducing reliance on intensive farming could help improve animal welfare”.

Seven respondents declared that the effects on well-being had yet to be experienced.

According to only six respondents, cultured meat does not promote sustainable development. These respondents stated that they had little information to express an opinion. According to all the other respondents (25), cultured meat pursues the principles of sustainable development by safeguarding the environment, raw materials, natural habitats, and animal welfare.

“Cultured meat could contribute to the pursuit of sustainable development by reducing environmental impact and improving agricultural practices. Its production requires less water, land, and feed than traditional meat, reducing the consumption of natural resources and greenhouse gas emissions”.

Additionally, it may reduce risks associated with foodborne illnesses (4).

The interviewees also highlighted how cultured meat has a lower environmental impact than traditional meat production, requiring less space, water, and feed to produce the same amount of meat. However, considering other factors, such as the energy needed for laboratory production and biological waste management, is also essential.

The respondents were asked whether cultured meat would become widespread in Italy. The results show that the interviewees considered Italy a traditionalist country linked to culinary traditions that wanted to safeguard the stakeholders involved in the agri-food sector and that could be more responsive to innovation.

“In my opinion, no, given that it was the first country to refuse, I think it will continue to insist on this position, mainly to safeguard the work of Italian farmers and the country’s culinary and food culture”.

More information is needed on the effects of this new food, which, according to some interviewees, would take hold in the coming years after considering its consequences in the countries that consume it and the costs at which it will be sold.

The results analysis of this section highlights that the respondents were divided on this issue. Some believed that this new food would reduce pollution, offer greater access to food, and thus improve collective well-being; others believed that synthetic meat would not reduce world hunger, given its high costs of production and sale.

- V.

- Cultured meat and socio-economic aspects

The interviewees were asked how introducing cultured meat could affect the agricultural industry and the local economy.

The quotations highlight how, for most respondents, introducing this new food would have risks and adverse effects on the local economy, including the loss of numerous jobs.

However, for some respondents (10), it would encourage the search for new production methods.

“The introduction of cultured meat influences the agricultural industry by generating new opportunities for research and development in production”.

According to 22 respondents, cultured meat puts traditional culinary culture and the Made in Italy food supply chain at risk:

“The food standardization that would be subjected to through this process would undermine one of the strengths on which our country is based”.

“Introducing different technologies and preparation methods are not part of our culture”.

However, for the remaining consumers, cultured meat does not put traditional culinary culture and the Made in Italy food supply chain at risk, as it could add a new innovative “dimension” to cuisine.

Indeed, “if cultured meat could integrate into this tradition, it could be seen as a complementary option rather than a threat”.

Most of those interviewed (14) said they would be willing to pay a lower price for cultured meat than traditional meat. Instead, nine individuals would be willing to pay more in light of the potential health and environmental benefits. Five consumers would pay the same price, and six respondents would not be willing to buy it. How can public acceptance of cultured meat be increased?

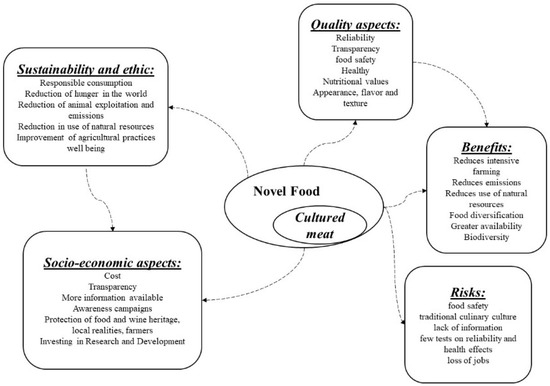

Figure 2 highlights the key themes that emerged from the analysis of the interviews.

Figure 2.

Key aspects on how to increase public acceptance of cultured meat (source: authors’ own creation).

In Italy, it is necessary to have a national plan for protecting and developing our food and wine tradition, which can truly support the development of small and medium-sized local businesses in our country. To increase public acceptance of cultured meat, the government, companies, laboratories, and consumers could adopt several strategies; for instance, they could include awareness campaigns on the importance of cultured meat for environmental sustainability and animal welfare, investments in research and development of more efficient and safer technologies, the implementation of regulations that guarantee the quality and safety of products, and the promotion of partnerships between the public and private sectors to support the adoption of cultured meat (15) [16,75]. It is necessary to have more information via social media, newspapers, and television programs and more transparency in the production process (16). Continuous investment in research and development is crucial (3).

The main results emerging from the interviews are summarized in the cognitive map in Figure 1.

The cognitive map highlights how the interviewees perceived cultured meat as an alternative that could help reduce emissions, use natural resources, and improve animal welfare, confirming the existing literature [19,20]. Furthermore, cultured meat would represent a diversified food option available on the market that pursues environmental, economic, and social sustainability by reducing world hunger. However, the analysis highlighted numerous doubts about the production phase of this food. Indeed, according to the respondents, further experiments and more information on the food safety of this novel food are needed. On the quality issue, the consumers highlighted the need to focus on the reliability, transparency, and food safety of this new food, also considering the nutritional values, flavor, and consistency compared to traditional meat. This research highlights the need for greater transparency, more significant investments in R&D, and awareness campaigns on this new food’s benefits and risks. A crucial aspect for Italian consumers is to protect their health and the reference sector by not reducing jobs and continuing to respect the culinary tradition of our country.

5. Discussion

Our results highlight the possibility of cultured meat gaining ground in Italy, considering the growing attention towards environmental sustainability and animal welfare. Consumer acceptance is key to negotiating market opportunities, especially for novel foods [76]. However, significant investments and consumer education may be needed to drive the country’s adoption of this technology. Italian consumers are likely to accept cultured meat considering its environmental benefits, reduction of animal suffering, and global food security; indeed, it could guarantee access to high-quality proteins even in regions where livestock farming is not feasible and could reduce dependence on intensive agricultural practices and make food systems more resilient to climate change. However, the interviewees highlighted that transitioning to cultured meat could generate socio-economic risks, such as uncertainties regarding safety and health and loss of food traditions [41,77]. Gomez-Luciano et al. (2019) [78] compared consumer acceptance of cultured meat in four countries (UK, Spain, Brazil, and Dominican Republic) and found that Spanish consumers were more tolerant, while Brazilian consumers were more conservative. As highlighted by our results, introducing cultured meat in Italy, a country with strong traditions related to the consumption of meat that is a cultural, identity, and Mediterranean diet symbol, represents a challenge for culinary customs. However, according to some interviewees, it could also offer opportunities for innovation and adaptation of the culinary tradition, allowing cultured meat to be integrated in ways that respect and preserve the authenticity of Italian cuisine [79]. Demographic differences also affect the acceptance of this novel food. Our analysis also showed that younger consumers are more open to food innovation and therefore inclined to consume cultured meat [44]. Indeed, the new generations are more attentive to sustainability, climate change, and animal welfare issues. Adults, on the other hand, are more attached to traditional foods. The interviewees, as also emerged in other studies [80,81,82], perceived cultured meat as unnatural compared to conventional meat. Italian consumers expect cultured meat to be as good as conventionally produced meat in terms of taste, appearance, and price.

Our results show that the biggest concern associated with the consumption of cultured meat is food safety. The interviewees highlighted the need to continue investing in research and development. The existing literature highlights that informing consumers can increase the consumption of more sustainable and animal welfare-friendly products [83]. Awareness campaigns are needed to communicate transparently with consumers by providing information on how cultured meat is a reliable, safe, and tested product and showing the different production phases and verification tests. This information must be conveyed by scientists, nutritionists, and industry experts through information and awareness campaigns to reduce skepticism. The information must come from reliable and credible health sources following solid experimental evidence demonstrating its efficacy and safety. It is necessary to start educating the youngest, for example, by integrating cultured meat into food education programs to make the concept known to the new generations. Supply chain stakeholders are key in transitioning to a more sustainable food system, and governments must support them. As highlighted by the interviewees, policymakers must support companies in the sector and the scientific community with funding and through specific regulations and certifications to protect all agri-food actors. Public policies must promote them as part of a sustainable food strategy. Cell lines to produce cultured meat in Europe will need to be approved by regulators through a rigorous scientific process, as has already happened in the US and Singapore, and consumer safety and trust are top priorities for regulators and the cultured meat industry. While governments have the opportunity to make the process more transparent to avoid unnecessary delays in applications, authorities should ensure that the process remains focused on food safety science. The scientific community and research centers must continue to invest in R&D to provide consumers with information on this novel food’s quality and reliability. Investment in research is essential to overcome the main barriers and obstacles identified by consumers, provide more details, and ensure food safety for the entire sector so that it reaps benefits [84].

This research has some limitations. First, through a qualitative survey, the authors explored intentions to accept the consumption of cultured meat despite it not being marketed. Therefore, future research should use different methodological approaches in other countries (even those where it is marketed) to examine the actual behavior of consumers. The study was conducted on a sample of Italian consumers. Therefore, future studies must replicate the research in other cultural contexts to understand the factors influencing consumer acceptance of cultured meat. In addition, the sample size was consistent with the proposed study’s exploratory nature, although the sample will be expanded in future research to enrich the proposed results.

6. Conclusions

This research explored Italian consumers’ perceptions of the spread of cultured meat. Italy has banned the production and marketing of cultured meat. However, governments and companies in the sector must identify the benefits and advantages of introducing this new technology in the agri-food sector.

Understanding doubts, uncertainties, and consumer perceptions about cultured meat is crucial to making it accepted and optimizing its production and diffusion. The results highlight the need for more information on the effects of consuming this meat on human health. Food safety emerged as a key issue related to the quality and sustainability of this novel food.

The respondents highlighted the need to protect all actors involved in the agri-food chain by supporting culinary traditions and small businesses. The respondents called for implementing regulations that guarantee the quality and safety of products and promoting partnerships between the public and private sectors to support the adoption of cultured meat. Governments and companies in the sector need to educate citizens, invest in R&D, and encourage sustainable production and consumption by highlighting the importance of protecting their resources, the environment, and animal welfare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.G.P. and G.A.; methodology, software, analysis: M.G.P.; writing: preparation of original draft, M.G.P.; review and supervision, G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Italian legislation (D.L.vo 24.6.2003, n. 211, “attuazione della Direttiva 2001/20/CE”) indicates that ethics approval is not required for anonymous interviews/questionnaires. However, this study respected ethical issue and policy specifically considering privacy and professional secrets. Values such as the human respect for life, free thinking, and international patients’ rights were observed for the data collection phase (see: https://www.garanteprivacy.it/web/guest/home/docweb/-/docwebdisplay/docweb/385378 (accessed on 10 January 2025)). The authors confirm that the participants accepted to participate in the research, aware of the fact that their anonymity was guaranteed.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Interview Track

| (I) Perceptions on Future Food |

| Define what the future food is for you in three words. |

| What benefits and disadvantages can these foods bring? |

| Do these future foods contribute to the pursuit of sustainability? Why? How? |

| (II) Traditional vs. Cultured Meat: Definitions and Expectations |

| Do you define yourself as a person who is attentive to problems related to the treatment and respect of animals? |

| In your opinion, is it healthy to consume conventional meat? |

| What do you think about cultured food? What advantages and risks can it have? |

| Italy has banned the production and marketing of cultured meat. What do you think? |

| Would you be willing to consume cultured meat? Why? |

| (III) CulturedMeat andQuality |

| Cultured meat and quality: explain your opinion. |

| Do you consider it a safe food? Why? |

| Do you think it’s healthy to consume cultured meat? |

| In your opinion, does cultured meat have the same nutritional properties as traditional meat? |

| In your opinion, can cultured meat match or exceed the flavor and texture of traditional meat? |

| Is the cultured meat production process reliable? |

| (IV) Cultured Meat Between Sustainability and Ethics |

| Would cultured meat solve issues related to food security, hunger, and nutrition? Why? |

| Does this innovative food promote the well-being of the individual/community? How? |

| Does this food promote sustainable development? How? |

| In your opinion, will the cultured meat market take hold in Italy? Why? |

| (V) Cultured Meat and Socio-economic aspects |

| How do you think the introduction of cultured meat could affect the agricultural industry and the local economy? |

| In your opinion, does cultured meat put traditional culinary culture and the Made in Italy food supply chain at risk? Why? |

| How much would you be willing to pay for cultured meat compared to traditional meat? |

| What do you think could be done to increase public acceptance of cultured meat? |

References

- FAO; WHO. Food Safety Aspects of Cell-Based Food; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aiking, H. Protein production: Planet, profit, plus people? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 483S–489S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seah, J.S.H.; Singh, S.; Tan, L.P.; Choudhury, D. Scaffolds for the manufacture of cultured meat. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 42, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treich, N. Cultured meat: Promises and challenges. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2021, 79, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritz, M.S.; Verbruggen, S.E.; Post, M.J. Alternatives for large-scale production of cultured beef: A review. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.J. Cultured meat from stem cells: Challenges and prospects. Meat Sci. 2012, 92, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, P. Clean Meat: How Growing Meat Without Animals Will Revolutionize Dinner and the World; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datar, I.; Betti, M. Possibilities for an in vitro meat production system. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.F. Is in vitro meat the solution for the future? Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.F.; Van Wezemael, L.; Chriki, S.; Legrand, I.; Verbeke, W.; Farmer, L.; Scollan, N.D.; Polkinghorne, R.; Rødbotten, R.; Allen, P.; et al. Modelling of beef sensory quality for a better prediction of palatability. Meat Sci. 2013, 97, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good Food Institute Europe. Tutto Quello che Volevi Sapere Sulla Carne Coltivata; Un Breve Manuale di Dati, Statistiche e Risorse; Good Food Institute Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sinke, P.; Swartz, E.; Sanctorum, H.; van der Giesen, C.; Odegard, I. Ex-ante life cycle assessment of commercial-scale cultivated meat production in 2030. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H.L.; Ellis, M.J.; Haastrup, P. Environmental impacts of cultured meat: Alternative production scenarios. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment in the Agri-Food Sector, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–10 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, M.C.; Antonioli, F. Exploring consumers’ attitude towards cultured meat in Italy. Meat Sci. 2019, 150, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketelings, L.; Kremers, S.; de Boer, A. The barriers and drivers of a safe market introduction of cultured meat: A qualitative study. Food Control 2021, 130, 108299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, C.S.; Allenby, B.R. Cultured meat: The systemic implications of an emerging technology. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Symposium on Sustainable Systems and Technology (ISSST), Boston, MA, USA, 16–18 May 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, C.; Barnett, J. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: A systematic review. Meat Sci. 2018, 143, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulain, J.P. Food in transition: The place of food in the theories of transition. Sociol. Rev. 2021, 69, 702–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteratos, K.S.; Sherman, R. Consumer interest towards cell-based meat. Int. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018; unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, N.C.; Markus, C.R.; Post, M.J. The effect of information content on acceptance of cultured meat in a tasting context. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231176. [Google Scholar]

- Harguess, J.M.; Crespo, N.C.; Hong, M.Y. Strategies to reduce meat consumption: A systematic literature review of experimental studies. Appetite 2020, 144, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Perceived naturalness, disgust, trust and food neophobia as predictors of cultured meat acceptance in ten countries. Appetite 2020, 155, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Bai, J. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat in urban areas of three cities in China. Food Control 2020, 118, 107390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesenfeld, L.P.; Maier, M.; Brazzola, N.; Stolz, N.; Sun, Y.; Kachi, A. How information, social norms, and experience with novel meat substitutes can create positive political feedback and demand-side policy change. Food Policy 2023, 117, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, G.A.; Fischer, A.R.; Tobi, H.; van Trijp, H.C. Explicit and implicit attitude toward an emerging food technology: The case of cultured meat. Appetite 2017, 108, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogueva, D.; Marinova, D.; Bryant, C. Meat me halfway: Sydney meat-loving men’s restaurant experience with alternative plant-based proteins. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueders, A.; Wollast, R.; Nugier, A.; Guimond, S. You read what you eat! Selective exposure effects as obstacles for environmental risk communication in the meat consumption debate. Appetite 2022, 170, 105877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Dou, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Sui, X. The development history and recent updates on soy protein-based meat alternatives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Sütterlin, B.; Hartmann, C. Perceived naturalness and evoked disgust influence acceptance of cultured meat. Meat Sci. 2018, 139, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvesson, M.; Deetz, S. Doing Critical Management Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pakseresht, A.; Kaliji, S.A.; Canavari, M. Review of factors affecting consumer acceptance of cultured meat. Appetite 2022, 170, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faletar, I.; Cerjak, M. Perception of cultured meat as a basis for market segmentation: Empirical findings from Croatian study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Barnett, J. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: An updated review (2018–2020). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceković, P.; García-Torralba, L.; Sakoulogeorga, E.; Vučković, T.; Perez-Cueto, F.J. How do consumers perceive cultured meat in Croatia, Greece, and Spain? Nutrients 2021, 13, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherp, H.Å. Quantifying qualitative data using cognitive maps. J. Res. Method Educ. 2013, 36, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, E. Anticipatory Life Cycle Assessment and Techno-Economic Assessment of Commercial Cultivated Meat Production. Good Food Inst. 2021. Available online: https://gfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cultured-meat-LCA-TEA-technical.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Betz, U.A.; Arora, L.; Assal, R.A.; Azevedo, H.; Baldwin, J.; Becker, M.S.; Zhao, G. Game changers in science and technology-now and beyond. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 193, 122588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Sans, P.; Van Loo, E.J. Challenges and prospects for consumer acceptance of cultured meat. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, O.; Scrimgeour, F. Consumer segmentation and motives for choice of cultured meat in two Chinese cities: Shanghai and Chengdu. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Padilha, L.; Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J. Sustainable meat: Looking through the eyes of Australian consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, M.; Phillips, C.J.; Fielding, K.; Hornsey, M.J. Testing potential psychological predictors of attitudes towards cultured meat. Appetite 2019, 136, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, P. If you build it, will they eat it? Consumer preferences for plant-based and cultured meat burgers. Appetite 2018, 125, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boereboom, A.; Mongondry, P.; de Aguiar, L.K.; Urbano, B.; Jiang, Z.; De Koning, W.; Vriesekoop, F. Identifying consumer groups and their characteristics based on their willingness to engage with cultured meat: A comparison of four European countries. Foods 2022, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant-Genevier, J. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, March–April 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1680–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, N.; Di Silvio, L.; Dunsford, I.; Ellis, M.; Glencross, A.; Sexton, A. Bringing cultured meat to market: Technical, socio-political, and regulatory challenges in cellular agriculture. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilks, M.; Phillips, C.J. Attitudes to in vitro meat: A survey of potential consumers in the United States. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Weele, C.; Driessen, C. How normal meat becomes stranger as cultured meat becomes more normal; ambivalence and ambiguity below the surface of behavior. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Z.F.; Morton, J.D.; Bekhit, A.E.D.A.; Kumar, S.; Bhat, H.F. Cultured meat: Challenges in the path of production and 3D food printing as an option to develop cultured meat-based products. In Alternative Proteins, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 271–295. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.Q.; Dumay, J. The qualitative research interview. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2011, 8, 238–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, K.; Gunaydin, S. Research using qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods and choice based on the research. Perfusion 2015, 30, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Hay, D.B.; Adams, A. How a qualitative approach to concept map analysis can be used to aid learning by illustrating patterns of conceptual development. Educ. Res. 2000, 42, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, M.G.; Guglielmetti Mugion, R.; Toni, M.; Di Pietro, L.; Renzi, M.F. Gamification and service quality in bike sharing: An empirical study in Italy. TQM J. 2021, 33, 1222–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia-Palacios, L.; Pérez-López, R.; Polo-Redondo, Y. Cognitive, affective and behavioural responses in mall experience: A qualitative approach. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguinis, H.; Solarino, A.M. Transparency and replicability in qualitative research: The case of interviews with elite informants. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 1291–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, L.M.; Meyer, M.; Estable, A. Improving accuracy of transcripts in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, M.; Choi, T.Y.; Li, M. Qualitative case studies in operations management: Trends, research outcomes, and future research implications. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, L.; Edvardsson, B.; Reynoso, J.; Renzi, M.F.; Toni, M.; Guglielmetti Mugion, R. A scaling up framework for innovative service ecosystems: Lessons from Eataly and KidZania. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 29, 146–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, M.G.; Arcese, G. ChatGPT between opportunities and challenges: An empirical study in Italy. TQM J. 2024, 37, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araslı, H.; Arıcı, H.E. The art of retaining seasonal employees: Three industry-specific leadership styles. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and interpretation of qualitative data in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, G.D.; McCracken, G. The Long Interview; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Aal, K.; Di Pietro, L.; Edvardsson, B.; Renzi, M.F.; Mugion, R.G. Innovation in service ecosystems: An empirical study of the integration of values, brands, service systems and experience rooms. J. Serv. Manag. 2016, 27, 619–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzan, T.; Buzan, B. The Mind Map Book; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.M. Cognitive mapping and repertory grids for qualitative survey research: Some comparative observations. J. Manag. Stud. 1992, 29, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chriki, S.; Hocquette, J.F. The myth of cultured meat: A review. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 507645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Murray, C.J. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, N.; Perito, M.A.; Lupi, C. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: Some hints from Italy. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Bai, J. How information affects consumers’ attitudes toward and willingness to pay for cultured meat: Evidence from Chinese urban consumers. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 3748–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; Dooley, J.J.; Dunsford, I.; Goodman, M.K.; MacMillan, T.C.; Morgans, L.C.; Sexton, A.E. Threat or opportunity? An analysis of perceptions of cultured meat in the UK farming sector. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1277511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Luciano, C.A.; de Aguiar, L.K.; Vriesekoop, F.; Urbano, B. Consumers’ willingness to purchase three alternatives to meat proteins in the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil and the Dominican Republic. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, S.; Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R. The digital and sustainable transition of the agri-food sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 187, 122222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnari, M. The future of meat consumption—Expert views from Finland. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2008, 75, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Sütterlin, B. Importance of perceived naturalness for acceptance of food additives and cultured meat. Appetite 2017, 113, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekker, G.A.; Tobi, H.; Fischer, A.R. Meet meat: An explorative study on meat and cultured meat as seen by Chinese, Ethiopians and Dutch. Appetite 2017, 114, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, A.R.; Briley, D.; Wilson, B.J.; Raubenheimer, D.; Schlosberg, D.; McGreevy, P.D. The price of good welfare: Does informing consumers about what on-package labels mean for animal welfare influence their purchase intentions? Appetite 2020, 148, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, G.G.; Heidemann, M.S.; Goes, H.A.A.; Molento, C.F.M. Can radical innovation mitigate environmental and animal welfare misconduct in global value chains? The case of cell-based tuna. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 169, 120845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).