Abstract

The decline in the young population in rural areas has led to a shortage of skilled labor in agriculture. While the use of technology and capital is often suggested as a solution, it may not be sufficient, especially with the aging rural population. The goal of this study was to examine the factors influencing young people’s decisions to stay in agriculture, and propose solutions. On the other hand, this study presents policy recommendations aimed at strengthening implementation tools for sustainable development and revitalizing global partnerships under SDG 17. Data were collected through surveys with 2398 young individuals aged 15–29 across 27 rural settlements in Turkey. A binary logit regression model was used to analyze the probability of young people remaining in agriculture. The results show that, similar to studies in developing economies, young men were more likely to stay in agriculture than young women. Additionally, having personal income or assets, as well as larger land and livestock holdings in the household, increased the likelihood of staying in agriculture. Conversely, migration from households and higher education levels decreased the probability. The study emphasizes the need for projects that improve the welfare of rural youth. Economic development alone is insufficient; policies integrating agricultural and social factors, including family dynamics, could be more effective in ensuring youth retention in agriculture and supporting sustainable agricultural production.

1. Introduction

On a global scale, the rural population has entered a rapid downward trend since the 1990s. Especially in economies with higher and higher-middle income, it is observed that rural population rates have negative values. According to the World Bank data, the proportion of rural population in the world is 42.66%, with a decrease of 3.86% in the last five years [1]. It would not be wrong to say that rural migration plays the most effective role in this proportional decrease [2]. In the historical process, there are many factors that trigger rural migration. These elements exhibit variations across different time periods and also demonstrate differences when examined at the global scale, in contrast to the smallest administrative units [3,4,5]. Despite this difference, the factors that are basically ongoing and have had a significant impact in recent years are economic inequality between rural and urban regions and the differences in social welfare and educational opportunities, mechanization and modernization in agriculture, and climate change [6].

The rural population is largely characterized as an agricultural one. Therefore, increasing rural migration leads to a decrease in the agricultural population and an increase in labor migration. In the literature, there are opinions that rural migration can have positive effects on agricultural production and rural development, as well as negative effects [7,8,9]. Regarding labor productivity, there may be a more effective and efficient use of the workforce [10,11], but there may also be a decrease in qualified labor and in agricultural productivity [12,13]. Regarding the amount of cultivated land, in contrast to the view that rural-to-urban migration decreases the amount of cultivated land [8,14,15,16,17], it is believed that it may contribute to providing capital resources for agricultural improvements and land acquisitions [18]. Another difference of opinion regarding the impact of rural migration on agricultural production regards the use of agricultural technology. On one hand, it is stated that it could lead to the deterioration and abandonment of traditional agricultural practices dependent on the labor force, and as a result, technology cannot be transferred. On the other hand, it is suggested that migration can contribute to the development of more modern technologies in rural areas through foreign exchange investments and increase agricultural income by increasing the scale of enterprises [19,20,21].

With the increase in technology and capital use, agriculture has become a business that can be managed from urban areas by many people with agricultural experience and has played an active role in the decrease in the rural population. However, the fact that migration from rural to urban areas is a mode of household migration has led to the youth moving away from agriculture, while decreasing the interest of rural youth in agriculture and becoming a sociological phenomenon that is effective on their decision to migrate. Although there are numerous factors driving rural-to-urban youth migration, recent studies indexed in Web of Science and Scopus indicate that current research predominantly focuses on agriculture-related issues such as climate change, technology, land inheritance, social and human capital, farm structures, agricultural income, and young people’s sense of belonging [22,23]. The acceleration of these studies on the relationship between rural youth and agriculture proves that the increase in technology use and capital transfer cannot be effective in the long term in terms of the sustainability of agricultural production without the rural youth remaining in agriculture. Indeed, considering that agriculture is a branch of activity carried out in rural areas, it seems necessary for educated and qualified rural youth to remain in agriculture in terms of the sustainability and development of agriculture.

The problem of the decline and aging of the agricultural population, especially in low- and middle-income economies, is discussed, and the search for solutions to encourage the rural young population to remain in agriculture continues [24,25]. As in many developing countries, the proportion of young population is high in Türkiye, and this rural population is transferred to urban areas. In particular, the tendency of the educated, young and active population to migrate constantly means that people who have the capacity to operate using modern production techniques leave the agricultural sector [26,27]. This situation is proposed to adversely affect the operator profile in the agricultural sector in the coming years. As a matter of fact, the importance of young people’s experiences with their agricultural roots is undeniable, as is that of mechanization and modern agricultural practices.

The continued engagement of youth in agriculture plays a strategic role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in the areas of food security, rural economic development, climate change mitigation, and agricultural innovation. In this context, there is a strong and direct linkage between youth retention in agriculture and several specific SDGs, including SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). Unleashing the potential of the agricultural sector and ensuring an adequate level of food production largely depend on the effective integration of the younger population into agricultural activities. The active participation of young farmers is therefore crucial to the achievement of SDG 2 targets [28,29,30]. While SDG 8 does not explicitly prioritize agriculture, its emphasis on “decent work” aligns with the need to improve the quality of agricultural employment. Globally, agriculture is often perceived as a low-income and low-status sector, reinforcing the necessity for subsidies and state support. Consequently, making agriculture a viable and attractive source of income for young people has become a matter of urgency [31]. Furthermore, young individuals are generally more open to adopting innovative and environmentally sustainable practices, offering a significant advantage in promoting climate-resilient agricultural methods. In this regard, the contributions of young farmers to achieving the goals outlined in SDG 12 and SDG 13 should not be underestimated [32,33,34].

However, current socio-economic conditions present a number of structural barriers that hinder the sustained participation of rural youth in agriculture. These barriers include limited access to capital and financial services, difficulties in land acquisition, insufficient agricultural training and knowledge, restricted access to technology and digital tools, negative social perceptions, the low attractiveness of rural life, and inadequate public policies. These multifaceted challenges indicate that youth retention in agriculture should not be considered solely from an economic perspective, but also in terms of social equity, equal opportunity, and quality of life. From the standpoint of SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), empowering rural youth to remain engaged in agricultural production is also essential for maintaining the rural–urban balance and achieving inclusive development. Therefore, enhancing youth participation in agriculture is indispensable for ensuring a more equitable distribution of welfare and sustainable rural development. In overcoming these challenges, both national and international cooperation and coordination are necessary. In this context, SDG 17 provides a comprehensive framework for developing partnerships, knowledge sharing, access to financial resources, and inclusive policy mechanisms that support the integration of youth into agriculture. Sustained youth involvement in agriculture cannot be achieved through individual efforts alone; rather, it requires multi-stakeholder, long-term, and inclusive collaborations. Thus, implementing structural transformations that enable young people to remain in agriculture is of paramount importance for the successful realization of the Sustainable Development Goals [35,36]. In summary, while the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) serve as a driving force for youth engagement in agriculture, the continued involvement of young people in agriculture also plays a pivotal role in achieving these goals. Regarding the agricultural production areas, Türkiye is a rich country in terms of production patterns and systems due to its climatic and geographical differences. However, the differences among the regions in terms of both agricultural and economic development are at a level that cannot be ignored. It can be stated that there is a similar distribution in economies of many countries. In this respect, studies addressing the relationship between rural youth and agriculture are carried out on a regional or sub-regional basis in terms of scope. Although these studies are important in terms of regional development policies, they are criticized for not reflecting the whole country. In order to increase rural welfare, ensure the development of agricultural production and achieve sustainability in agriculture, studies that could reveal the structure of economies are needed in order to develop policies and practices to encourage the young population to stay in agriculture and specialize. This study aimed to determine the tendency of the young population to stay in agriculture in Türkiye, and to develop solution proposals for this. In other words, this study seeks to answer the question of what factors could influence young people to remain in agriculture and aims to develop recommendations to ensure their continued participation in the agricultural sector. This study, which covered all of Türkiye, is important in terms of shedding light on rural development and agricultural policies, with the problems and solution proposals it identifies. Particularly in terms of rural development, it is believed that policies aimed at ensuring sustainable agricultural production and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) could guide the fulfillment of several sub-goals (SDG 2,8,12 and 13) alongside SDG 17. In addition, it could also constitute a source of information for other countries, especially low- and middle-income economies that face similar problems in the global economy, in terms of problem identification and solution development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

The main material of this study, which aimed to reveal the tendency of the young population in rural areas to remain in agriculture, consisted of primary data obtained through face-to-face surveys. The sample volume that could best represent Türkiye in the study was determined in two stages. In the first stage, the provinces that could represent Türkiye in terms of migration were determined. The dominant structure of rural migration in the migration phenomenon was taken into consideration, and an attempt was made to establish a relationship between agriculture and rural migration. Thus, a rational universe volume was created in the study, focusing on nine agricultural production regions in Türkiye determined by The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. In this context, three provinces were determined to represent each region based on the net migration rate averages for the past thirteen-year period, and twenty-seven provinces were included in the universe of the study (Table 1). Net migration rate (NMR) expresses the net migration number for every thousand people who can migrate and is calculated as shown in Equation (1). In accordance with the net migration rate criterion, careful attention was paid to ensure that each region was represented by the provinces with the highest levels of migration, either as senders or receivers, and that the values fell within the specified range. In this way, geographical units with different migration rates were included in the sample, and the intention was to reach individuals with different migration tendencies.

Table 1.

Provinces surveyed by region and their net migration rates in Türkiye.

Net migration rate is obtained by multiplying the ratio of internal migration change (migration in–migration out) to the regional population by 1000 [37].

where NMR.i-i. is net migration rate, m.i is in-migration, mi. is out-migration, m.i − mi. is net migration, Pi,t+n is population residing in “i” at the time “t + n”, i is the place in which migration is defined, and k is a constant (k = 1000).

In the second stage, the sample size was determined as 2398 by using the random probability sampling method (Equation (2)) based on the young population between the ages of 15 and 29, living in villages of 27 provinces. In Türkiye, the migration rate is highest among individuals aged 15–29. Consequently, this age group constitutes the target population of the study, as it represents rural youth. Furthermore, this age range also aligns with the age bracket (15–24 years) defined as youth in the United Nations’ definition. The number of surveys to be conducted in each province was distributed proportionally, taking into account the rural populations of the selected provinces [38]. In Equation (1), n is the sample size, N is the number of units in the main population, d is the deviation from the acceptable mean (0.02), t is the t table value at the 95% confidence interval (1.96), p is the ratio of the examined unit in the population (0.50), and q is (1 − p).

A total of 2398 participants were purposively selected based on age groups, and data were collected using the face-to-face survey technique. Participants in the 15–19 age range make up 34.8% of the sample, and surveys with these participants were conducted under parental supervision.

As a result of a face-to-face survey conducted with 2398 participants, general information about the village, as well as general information about the participants and their households, alongside data regarding agricultural activities and migration, were obtained. A dataset consisting of 289 horizontal slices was collected in total.

2.2. Empirical Model

Young people staying in agriculture is considered critical for the sustainability and development of agricultural production. On the other hand, young people staying in agriculture is closely related to the phenomenon of rural migration. It is necessary to determine the tendency of young people to stay in agriculture in terms of both economic and sociological aspects. In this context, the binary logit regression model, which is one of the binary choice models, was used to determine the probability of young people staying in agriculture and the factors affecting these probabilities.

In the logit model, estimated probability values of the discontinuous dependent variable varied between 0 and 1. This model tries to determine the probability of the dependent variable (Yi) being 1 by estimating the result as a value between 0 and 1 [39]. The dependent variable of the research was determined as binary, where rural young people who wanted to stay in agriculture was 1 and those who did not want to stay was 0. The logistic distribution function explaining the binary logit regression model is given in Equation (2) [40].

The probability of young people staying in agriculture is (Pi) and the probability of not staying is (1 − Pi). Accordingly, Pi/(1 − Pi) is the ratio of the probability of a young person staying in agriculture to the probability of not staying in agriculture. Then, the binary logit regression model is

When written as in Equation (3), the β2 coefficient indicates the slope and Xi indicates the independent variables. Accordingly, it can be estimated how a unit change in Xi changes the logarithmic ratio of the probability of affecting the young individual (such as the increase in the tendency of a young person who is having or has received a university education to leave agriculture) to the probability of not affecting them. In addition, the marginal effects of each variable can be used to interpret the coefficients in the estimated logit model (Equation (4)).

When the partial derivative of the probability is taken with respect to the independent variable, the determination that the changes in the independent variable have a constant effect on the probability is made, with the marginal effect of on [41].

Accordingly, it is concluded that the rate of change of probability according to the independent variable depends not only on , but also on the level of probability at which the change is measured. In this case, it is stated that the change in the independent variables has the greatest effect on the probability of choosing any preference at the midpoint of the distribution. In order to determine the best model, different model trials were performed for the variables. These trials were tested statistically to see if they were significant at the 5% level of probability. The model created to determine the possibilities of rural youth remaining in agriculture and the factors affecting these possibilities are as follows.

The variables used in the model are given in detail in Table 2. When variables are examined in detail, they are observed to present with a scaled, ordinal, nominal measurement structure, including both continuous and discrete variables. The variables refer to the participants’ age (X1), education level (X2), gender (X3), ownership of any personal property (X4), income status (X5), beliefs about agriculture having adequate income (X6), land ownership of the household (X8), livestock ownership of the household (X9), and the number of migrants from the household (X10). Variable X7 indicates the distance from the participants’ place of residence to the city center, while variable X11 was constructed based on the Human Development Index calculated for the participants’ provinces in 2019. Education level (X2), beliefs about agriculture having adequate income (X6), and livestock ownership of the household (X9) are considered as ordinal variables rather than categorical variables.

Table 2.

Variables used in the logit model and descriptive statistics.

3. Results and Discussion

In terms of the willingness of young people to migrate from rural areas to urban areas, more than half of the young people (58.4%) were quite determined to migrate from their villages, while 41.6% stated that they did not want to migrate, stating that leaving their villages was not a good option. The migration intention of young people also varied according to the regions they lived in. It was determined that especially young people living in rural areas of the Black Sea Region were inclined to migrate to a large extent (65.9%), while young people living in rural areas of the Central South Region were inclined to migrate to a lesser extent (37.0%). It was observed that 48% of young people tended to stay in agricultural production. In addition, the rate of young people who tended to continue agricultural production despite the decision to migrate was also high. This situation can be explained by the increase in the use of technology in agriculture and the decrease in workload, especially in plant production.

In addition to the elements listed in Table 3 that could affect the desire to continue agricultural production, it is also important to evaluate some additional issues. In this sense, socio-economic and demographic characteristics may be effective in the tendency of young people to remain in agriculture. Of the young people interviewed in the study, 24% were female and 76% were male. The average age was 22.1 years. Of all youth interviewed, 34.8% was in the 15–19-year age group, 30.5% in 20–24-year group and 34.7% in 25–29-year group. A strong correlation was found between the age of the young people and their level of education, marital status, and having many assets related to agriculture (having livestock, agricultural land and agricultural income, etc.). In fact, it was observed that young people in the 15–19-year age group continued their high school education, and that the rate of university graduates increased as the age increased. Besides this, as the age range increased, young people who graduated from primary and secondary schools were encountered. The same result was also found in marital status, as expected, and the rate of married people (49.8%) among young people aged 25–29 increased significantly compared to others.

Table 3.

General information on youth by age groups (%).

The sustainability of agricultural production and therefore the protection of the rural population are made largely possible by keeping young people in agriculture. In this context, it could be important for young people to have a sense of belonging to both agriculture and rural life. In strengthening the sense of belonging, it could be effective for young people to have their own income and property. According to the information obtained, young people in the 25–29-year age group were the majority, and only 17.3% of young people had agricultural income. This situation is related to the fact that young people are not interested in agricultural production, and that they function as laborers in family businesses despite being engaged in agriculture. The situation of having property related to agriculture reveals this more clearly. It is striking that young people owned very low levels of their own land (12.7%), livestock (4.5%) and machinery equipment (7.7%). Agricultural welfare and financial sufficiency can be effective in the sustainability of agricultural production and in keeping young people in agriculture. When the views of the youth on the effects of remaining in agriculture on their welfare and the financial adequacy of agriculture were examined, the dominant view was that agriculture negatively affected welfare (42.9%) and was not financially sufficient (50.8%). However, 33.5% of the youth stated that agriculture had no effect on welfare and 25.3% stated that agriculture was neither financially sufficient nor insufficient.

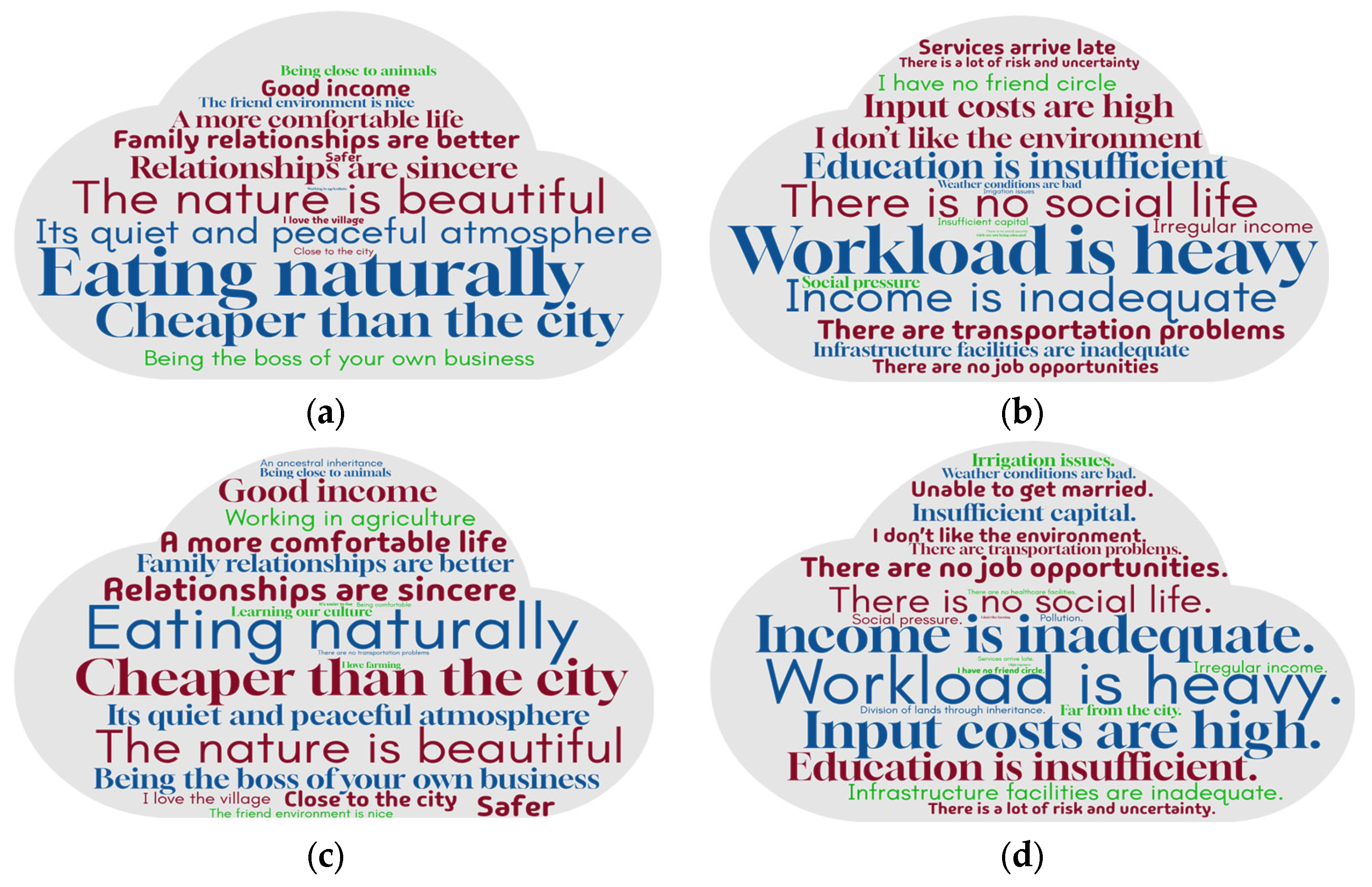

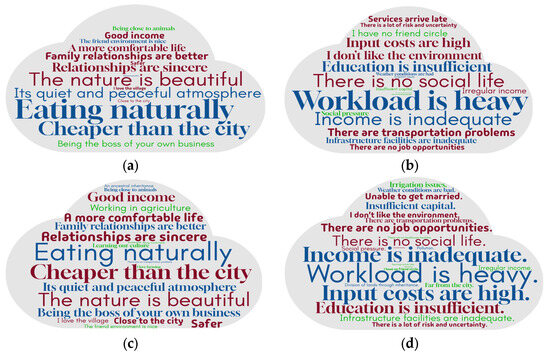

Young people’s approaches to rural life are as important as other issues, such as financial sufficiency, welfare, property and income, to their staying in agriculture. In this context, understanding the young people’s driving and pulling forces in relation to living in rural areas and engaging in agricultural activities is needed. In the light of the information obtained, 37.5% of the young people stated that there was no positive aspect, and 24.6% stated that there was no negative aspect regarding living in rural areas and engaging in agricultural activities. The attractive and repulsive aspects of rural life and agricultural activities according to young people are given in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Young people stated that, rather than agricultural activities, issues such as the natural beauty of rural areas, natural nutrition, the lower cost of living and human relations made life in rural areas attractive. On the other hand, young people stated that both agriculture and rural life were difficult for reasons such as a lack of social life opportunities, heavy workload, insufficient income and inadequate education.

Figure 1.

Young peoples’ thoughts on rural life; (a) Young peoples’ positive thoughts on rural life; (b) Young peoples’ negative thoughts towards the rural life.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of rural areas according to youth; (a) positive aspects of rural areas according to female youth; (b) negative aspects of rural areas according to female youth; (c) positive aspects of rural areas according to male youth; (d) negative aspects of rural areas according to male youth.

Young people staying in agriculture is considered very important for the sustainability and development of agricultural production. In addition to the conditions of rural living itself, it is necessary to determine the tendency of young people to stay in agriculture in terms of both economic and sociological aspects. The binary logit model results determining the tendency of young people to stay in agriculture are given in Table 4. The significance of the model was evaluated with the likelihood ratio, which is equivalent to the F test in the linear regression model, and the model was found to be significant at the 1% significance level. McFadden coefficients of determination are frequently used in the literature to explain the goodness of fit of the logit model. Although goodness of fit measures are of secondary importance in binary choice models, this value was found to be 0.24 in the analysis, and it was observed that the independent variables were sufficient to explain the dependent variable [41]. On the other hand, according to the model results, the coefficients of all variables included in the model had the expected sign. The fact that the likelihood ratio (LR), which measures the significance of the explanatory variables, was significant and the log-likelihood value was of sufficient size indicates the suitability of the adapted model.

Table 4.

Binary logit model results.

A statistically significant relationship was found between the desire of rural youth to remain in agriculture and their age (X1) (p < 0.05). Accordingly, when young people between the ages of 15 and 29 were considered, it was predicted that the probability of rural youth remaining in agriculture may increase by 0.006 times in the event of a one-unit (year) increase in age. These findings are similar to those from some other studies in the literature. Arli et al. (2014) examined young people between the ages of 18–25 in order to understand the tendencies of young people towards the agricultural sector, and to determine which factors are effective in their desire to do or not to do farming [42]. In their study, they attributed the low agricultural income level to the fact that young people do not want to do farming, while emphasizing that education is an important factor impacting the respect of farmers in society and the increase in the quality of life of farmers, and that non-agricultural job opportunities should be created in rural areas. Yakar (2012) stated in their research that the number of household heads aged 65 and over was 4 times the number of household heads under the age of 35 years, and that the majority of their adult children migrated to find work [43]. Güreşçi and Yurttaş (2008), on the other hand, found that the number of young household heads in rural areas was very low as a result of migration, and households generally consisted of two people living with their spouses [44].

When the level of education (X2) was taken into account, it was observed that there was a significant negative relationship between the tendency of young people to stay in agriculture and their level of education. When the agricultural structure is examined in Türkiye, it is determined that the level of education is quite low. It can be stated that the findings obtained were consistent with this aspect, and it could be stated that the probability of young people living in rural areas staying in agriculture may decrease by 0.09 times as the level of education of young people increases. In addition, studies conducted in different countries have emphasized that the young population with a high level of education had a negative attitude towards agriculture, and considered agriculture as a last option in career planning [45,46,47,48].

Figure 2 indicate that the attractive aspects of agriculture and rural life are the same in both groups, while the negative aspects are more social life-oriented in women, while problems related to agricultural production are given more importance by men. This finding shows that young men prioritized agriculture more than women. In fact, when the model result was evaluated in terms of gender (X3), it was revealed that the probability of young men staying in agriculture was statistically higher than young women, at a 1% significance level. Accordingly, it is predicted that the probability of young men living in rural areas and carrying out agricultural activities compared to young women may increase by 0.252 times.

It is stated that women are underrepresented in agricultural research and higher education, but play a vital role in global agricultural production [49,50]. Eissler and Brennan (2015) argued that young women experience many constraints when engaging in agriculture [51]. They emphasized that in order to increase the number of young women pursuing agriculture as a career, there is a need to shift from the perception of current women as “farm helpers” to women playing a central role in agribusiness activities [52].

When rural youth had their own income (X4) and assets (X5) and perceived agriculture as providing sufficient income (X6), these had positive and significant effects on the probability of rural youth remaining in agriculture, as expected. The probability of a young person remaining in agriculture increased by 0.137 times when the young people had their own assets, by 0.046 times when they had their own income and by 0.107 times when they thought that agriculture provides sufficient income. In this context, it could be stated that while income is an important factor for the young person to continue agricultural activities, the sense of belonging is also important.

Considering the fact that small family businesses are predominant in rural areas, the head of the household (usually the father) carries the ownership of the land and livestock as long as he/she is alive, and thus maintains his/her power. On the other hand, young people who are expected to continue the business remain uninterested in taking responsibility for a long time since they do not have their own assets or income. During this process, they start looking for another job or life [53]. Suriname (2009) stated that young people were reluctant to engage in agriculture due to the lack of access to productive assets, especially land, or the lack of control over them [53]. Again, the size of the household’s land (X8) and livestock (X9) also had a positive effect on the young person’s staying in agriculture. It was found that an increase in the household’s land holdings and livestock holdings can increase the probability of young people staying in agriculture by 0.001 times and 0.034 times, respectively.

When the probability of staying in agriculture was evaluated in terms of the regions where rural youth resided (X11.4), the probability of staying in agriculture increased by 0.099 times if the region where the youth lived had higher human development index compared to a low one. In this sense, living in a region that is developed in terms of health, education and income factors for rural youth is an important criterion in terms of continuing agricultural activities. In fact, another factor supporting this finding came from the distance of the place where the youth lived to the city center (X7) variable. In other words, as the distance of the place where the youth lived to the city center increased, the probability of staying in agriculture was negatively affected, albeit at a low rate (−0.001). Goran and Jelisavka (2017) emphasized that the participation of young people in the agricultural sector depends on where they live. Especially among students in rural areas, agriculture is generally perceived as a less valuable subject or a last option [54]. On the other hand, urban youth generally view agriculture as a ‘demanding job’ that they are not open to pursuing [45]. Finally, the number of individuals migrating from the household (X10) also appeared as a factor that negatively affected the possibility of young people staying in agriculture, as expected. As the number of migrants in the household where the young person lived increased, the probability of the young person staying in agriculture decreased by 0.052 times. Tasgin et al. (2016) conducted a study specifically in Erzurum province of Türkiye, and found that there was a linear relationship between the increase in the number of farmers’ relatives who had migrated and their desire to migrate themselves [55].

4. Conclusions

Socio-economic status has become a determining factor for young people’s decision to stay in the agricultural sector. Developing technology, social welfare and economic conditions are among the factors that encourage migration from rural to urban areas. The research findings have revealed that the desire of young people to stay in agriculture or, in other words, to continue agricultural production is positively affected by economic factors that reinforced the sense of belonging. However, it was determined that socio-cultural factors have the potential to increase rural migration by negatively affecting the tendency of young people to stay in agriculture. In addition, it was shown that men and young people between the ages of 25–29 tend to continue agricultural activities. This situation is a clear indication that the sustainability of the agricultural sector is under threat in terms of future generations.

Another finding obtained in the research is that younger and more educated individuals living in rural areas in Türkiye are less likely to stay in agriculture. This finding shows that, in addition to economic conditions, the social opportunities and living standards of rural life also play an important role today. If the social dimension is not adequately addressed in rural development policies, it is clear that this situation would pose a significant threat in terms of agricultural sustainability in the coming years. In this context, practices and policies aimed at rural areas should not be the responsibility of only the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, but should also be addressed via a holistic approach with various ministries and institutions, such as the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Family and Social Services, and the Ministry of Youth and Sports. Considering the Sustainable Development Goals, it is believed that the development of such inter-institutional collaborative projects and the adoption of related policies (SDG 17) are of significant importance. It is undeniable that addressing the identified issues related to the continuity of agricultural production and the prevention of rural migration will also contribute to achieving the sub-goals of the Sustainable Development Goals, such as SDG 2, 8, 12 and 13.

Research findings support the idea that the most effective factors in keeping young people living in rural areas of Türkiye in agriculture are economic ones. In this context, in order to reduce rural migration and increase the welfare level of rural young people, it is of great importance to ensure that the profile of an agricultural business is transformed in favor of young people, and to develop sustainable agricultural policies. Various projects and studies are being carried out in Türkiye for young people, and these projects should be made more comprehensive and resource transfer should be increased. In addition, in order for agriculture to reach a more satisfactory level in economic terms, it is of great importance to first solve social security problems and direct young people towards sustainable businesses.

In this context, it is thought that the expansion of projects covering the rural youth population in Türkiye, especially the young people in the 15–29 age group, could yield more effective results. In addition, focusing on local projects targeting young people at regional and provincial levels would be an important step in terms of the sustainability of agriculture. Increasing the advantages granted to young people and young women by the European Union grant funds through the Agriculture and Rural Development Support Institution (TKDK), which has been implemented in Türkiye since 2007, is considered another strategy that would support young people’s tendency to remain in agriculture. Finally, it is emphasized that comprehensive and continuous education activities to keep young people in rural areas and to provide agricultural education should be developed.

Although the findings of this study are significant in terms of the country’s rural development and agricultural policies, it is essential that relevant institutions conduct further investigations, particularly to facilitate an in-depth analysis and draw definitive conclusions. Furthermore, while this research is expected to inform numerous studies, it is important to note that its scope is limited. Future researchers are encouraged to approach the topic not only from an agricultural perspective, but also within the context of rural life sustainability, as this approach is crucial for both identifying problems and developing solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and G.E.; methodology, M.A.; investigation, B.A., G.E., A.Ç. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, G.E. and A.Ç.; project administration, G.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Scientific and Technological Research Projects Support Program (119K769) of the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data set used and/or analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Guresci, E. Agricultural Factors as the Root Cause of Rural Migration from a Global Perspective. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbański, M. Comparing Push and Pull Factors Affecting Migration. Economies 2022, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaika, M.; Reinprecht, C. Migration drivers: Why do people migrate. In Introduction to Migration Studies: An Interactive Guide to the Literatures on Migration and Diversity; Scholten, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.I.; Alharthi, M.; Haque, A.; Illiyan, A. Statistical analysis of push and pull factors of migration: A case study of India. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2023, 35, 102859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Liao, T.F. Labor out-migration and agricultural change in rural China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Long, H.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, D.; Yang, R. Effects of rural–urban migration on agricultural transformation: A case of Yucheng City, China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.E.; Lopez-Feldman, A. Does migration make rural households more productive? Evidence from Mexico. In Migration, Transfers and Economic Decision Making among Agricultural Households; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 68–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, N.; Luo, X. The impact of migration on rural poverty and inequality: A case study in China. Agric. Econ. 2010, 41, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sarkar, A.; Hossain, M.S.; Li, X.; Xia, X. Household Labour Migration and Farmers’ Access to Productive Agricultural Services: A Case Study from Chinese Provinces. Agriculture 2021, 11, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagakos, D. Urban-rural gaps in the developing world: Does internal migration offer opportunities? J. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 34, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Sun, X. Does labor migration affect rural land transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E.B. Migration and rural development. EJADE Electron. J. Agric. Dev. Econ. 2007, 4, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.; Larsen, A.; Noack, F. The land use consequences of rural to urban migration. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2024, 106, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Cao, S.; Qing, C.; Xu, D.; Liu, S. Does labour migration necessarily promote farmers’ land transfer-in? Empirical evidence from China’s rural panel data. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, B.; Lu, Z. The impact of rural out-migration on arable land use intensity: Evidence from mountain areas in Guangdong, China. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Deng, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, S. Labor migration and farmland abandonment in rural China: Empirical results and policy implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Hu, R.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, C. How Does Rural–Urban Migration Experience Affect Arable Land Use? Evidence from 2293 Farmers in China. Land 2020, 9, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deotti, L.; Estruch, E. Addressing Rural Youth Migration at Its Root Causes: A Conceptual Framework; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, W.; Wang, D.; Zheng, L. The impact of migration on agricultural restructuring: Evidence from Jiangxi Province in China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Reardon, T. The rapid rise of cross-regional agricultural mechanization services in China. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 95, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Web of Science. 268 Results from Web of Science Core Collection for: Refine Results for Agriculture and Rural Migration and Youth (All Fields). Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/summary/b1a7b63a-4138-4f53-8014-b775efa4d9f6-0154a74de6/author-ascending/1 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Scopus. 6159 Search Documents: Agriculture AND Rural AND Migration AND Youth (All Fields). Available online: https://www.scopus.com/results/results.uri?st1=SDGs+and+youth+farmer&st2=&s=ALL%28agriculture+AND+rural+AND+migration+AND+youth%29&limit=10&origin=searchbasic&sort=plf-f&src=s&sot=b&sdt=b&sessionSearchId=f9d83a333972e35d9385b6f482b571f5 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Mazumdar, D. Rural-urban migration in developing countries. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987; Volume 2, pp. 1097–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Mendola, M. Rural out-migration and economic development at origin: A review of the evidence. J. Int. Dev. 2012, 24, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davran, M.K.; Özalp, B.; Tok, N.; Öztornacı, B. Türkiye’de kırsal gençlik açısından istihdam ve tarımsal istihdamın geleceği. Gençlik Araştırmaları Dergisi 2017, 5, 169–199. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçın, G.E.; Kara, F.Ö. Rural Migration and Effects on Agricultural Production. Harran J. Agric. Food Sci. 2016, 20, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osabohien, R.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Youth in agriculture and food security in Nigeria. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2025, 52, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geza, W.; Ngidi, M.; Ojo, T.; Adetoro, A.A.; Slotow, R.; Mabhaudhi, T. Youth Participation in Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyanju, D.; Mburu, J.; Gituro, W.; Chumo, C.; Mignouna, D.; Ogunniyi, A.; Akomolafe, J.K.; Ejima, J. Assessing food security among young farmers in Africa: Evidence from Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda. Agric. Food Econ. 2023, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losch, B. Decent Employment and the Future of Agriculture. How Dominant Narratives Prevent Addressing Structural Issues. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 862249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osabohien, R. ICT adoption and youth employment in Nigeria’s agricultural sector. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2024, 15, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirambo, D. Can Social Innovation Address Africa’s Twin Development Challenges of Climate Change Vulnerability and Forced Migrations? J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 7, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouko, K.O.; Ogola, J.R.O.; Ng’on’ga, C.A.; Wairimu, J.R. Youth involvement in agripreneurship as Nexus for poverty reduction and rural employment in Kenya. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2078527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann-Aoyagi, M.B.; Miura, K.; Watanabe, K. Sustainability in Japan’s Agriculture: An Analysis of Current Approaches. Sustainability 2024, 16, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldhar, S.M.; Hussain, T.; Thaochan, N.; Bana, R.S.; Jat, M.K.; Nidhi, C.N.; Sarangthem, I.; Sivalingam, P.N.; Samadia, D.K.; Nagesh, M.; et al. Entrepreneurship opportunities for agriculture graduate and rural youth in India: A scoping review. J. Agric. Ecol. 2023, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkstat. Net Migration Rate. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=nufus-ve-demografi-109&dil=1 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Çiçek, A.; Erkan, O. Tarım ekonomisinde araştırma ve örnekleme yöntemleri. Gaziosmanpaşa Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Yayınları 1996, 12, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Özer, H. Nitel Değişkenli Ekonometrik Modeller: Teori ve Bir Uygulama; Nobel Yayın Dağıtım: Ankara, Turkey, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D. Econometrics by Example; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arlı, R.; Balcı, M.; Abay, C. Gençlerin Kırsalda Çiftçilik Yapma Eğilimleri: Akhisar İlçesi Örneği. In Proceedings of the Ulusal Aile Çiftçiliği Sempozyumu, Ankara, Türkiye, 30–31 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yakar, M. Internal and international migration effects on age structure of rural population: A case study on Emirdag county. Turk. J. Geogr. Sci. 2012, 10, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güreşci, E.; Yurttaş, Z. ASurvey on the Causes of Rural Migration and Its Effects onAgriculture: An Example Kırık County, Ispir, Erzurum. Turk. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 14, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chinsinga, B.; Chasukwa, M. Youth, agriculture and land grabs in Malawi. IDS Bull. 2012, 43, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Allen, W.; Kleinschmidt, C. Career motivations and attitudes towards agriculture of first-year science students at The University of Queensland. Agric. Sci. 2011, 23, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ojebiyi, W.G.; Ashimolowo, O.R.; Soetan, O.S.; Aromiwura, O.A.; Adeoye, A.S. Willingness to venture into agriculture-related enterprises after graduation among final year agriculture students of Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta. Int. J. Appl. Agric. Apic. Res. 2015, 11, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ridha, R.N.; Wahyu, B.P. Entrepreneurship intention in agricultural sector of young generation in Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 11, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shisler, R.C.; Sbicca, J. Agriculture as carework: The contradictions of performing femininity in a male-dominated occupation. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 875–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Krauss, S.E.; D’Silva, J.L.; Tiraieyari, N.; Ismail, I.A.; Dahalan, D. Towards agriculture as career: Predicting students’ participation in the agricultural sector using an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2022, 28, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissler, S.; Brennan, M. Review of Research and Practice for Youth Engagement in Agricultural Education and Training Systems; Paulines Publications Africa: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, B. Does group farming empower rural women? Lessons from India’s experiments. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 47, 841–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriname, V.L. Youth in agriculture-challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth Regular Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, Georgetown, Guyana, 2–5 July 2009. Unpublished Report. [Google Scholar]

- Goran, R.; Jelisavka, B. Some aspects rural-urban interdependence: Economic-geographical view. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 2017, 61, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşğın, G.; Kadıoğlu, S.; Gezenoğlu, C.K.; Kadıoğlu, B. Kırsal Göçü Etkileyen Faktörlerin Analizi: Erzurum İli Örneği. In Proceedings of the XII Ulusal Tarım Ekonomisi Kongresi, Isparta, Turkey, 25–27 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).