Abstract

This systematic literature review examines the relationship between Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Pro-Environmental Behaviors (PEBs). Considering the worsening climate change and the current climate emergency, pro-environmental behavior has gained significant attention in the literature. PEBs aim to minimize negative impacts and maximize positive impacts on the environment. Researchers have focused on the Connectedness to Nature as a potential driver of Pro-Environmental Behavior. However, there is no universally agreed definition of this construct, which can be understood as a profound connection with nature. The primary aim of this study is to investigate the existence of a relationship between Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Pro-Environmental Behaviors (PEBs). To determine if such a relationship be identified, this study further attempts to clarify its direction and assess the magnitude of this association. This literature review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). To identify relevant studies, we searched multiple academic databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Sociological Abstracts, PsycArticles, PsycINFO, Science Direct, and Academic Search Complete. The search strategy involved the use of the keywords: “Connectedness to Nature” and “Pro-Environmental Behavior”. The search process yielded a total of 2280 records after the removal of duplicates. Among these, only 29 studies met the established inclusion criteria and were therefore selected for analysis. The findings reported in the reviewed literature consistently indicate the existence of a significant and positive relationship between Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Pro-Environmental Behaviors (PEBs), although this association appears to exhibit considerable variability across studies. Overall, individual Pro-Environmental Behaviors showed a stronger association with Connectedness to Nature (CN) compared to activism-related behaviors. The findings of this review highlight the potential value, for practitioners engaged in environmental protection, of promoting and enhancing individuals’ connectedness to the natural world. Strengthening CN may represent an effective strategy to foster Pro-Environmental Behaviors, particularly in relation to sustainable consumption practices and recycling activities.

1. Introduction

1.1. Climate Change

The latest 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [1] emphasized the significant and rapid alterations occurring in the Earth’s climate, which are leading to a range of direct and indirect consequences. These include issues such as poverty, the spread of infectious diseases, forced migration, and conflict, all of which are exacerbated by interconnected global systems [1,2]. To mitigate the devastating health consequences worldwide, there is a strong scientific consensus on the necessity of reducing climate-related risks, impacts, and vulnerabilities [1,3]. A series of individual actions indicated as potentially helpful to combat these negative effects are Pro-Environmental Behavior (PEB) [4] and Connectedness to Nature constructs. Pro-environmental behaviors are characterized as actions intended to reduce harmful effects (e.g., using energy-efficient light bulbs) and enhance beneficial outcomes (e.g., planting trees) for the environment [5,6]. The concept of Connectedness to Nature (CN), as introduced by Mayer and Frantz [7], refers to the degree to which individuals feel emotionally and experientially connected to the natural world, indicating their sense of belonging and integration within nature. Based on the literature presented below, a positive relationship between CN and PEB is expected across the included studies.

1.2. Pro-Environmental Behavior Literature Background

In recent decades, Pro-Environmental Behaviors (PEBs) have become crucial in addressing the negative effects of climate change [4]. Pro-environmental behaviors are those actions aimed at minimizing negative impacts (e.g., using energy-efficient light bulbs) and/or maximizing positive impacts (e.g., planting trees) on our planet [6].

Pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) can be categorized into distinct clusters representing different domains of action, as highlighted by Kurisu and Kurisu [8]. These clusters include “place” (e.g., public transportation use), “actors” (e.g., individuals, corporations, and organizations), “influential fields” (e.g., global warming, energy conservation, water management, and waste reduction), and “household” (e.g., sustainable product choices for daily needs).

The study of Pro-Environmental Behaviors identifies two main groups of variables that can exert a significant influence on these behaviors [9]. The first group includes personal factors, such as attitude, norms, values, and knowledge. The second group consists of external factors, such as air pollution, the economy, politics, government regulations, and environmental NGOs. The first category influences PEBs “from within”, while the second category influences PEBs “from outside”.

It is clear that political power is not the only entity responsible for addressing climate change; every citizen, in their own small way, must play their part if we are truly to help and strongly support our planet. Each individual has hundreds of ways to reduce the negative impact of the climate crisis. Reference [4] provides the following examples of individual Pro-Environmental Behaviors: purchasing cars with smaller engines, switching to more fuel-efficient cars, reducing car travel, walking or cycling instead of driving when possible, preferring public transport over private vehicles, installing energy-efficient light bulbs, installing renewable energy sources (e.g., solar panels and wind turbines), turning off lights when not needed, unplugging devices when not in use, using more environmentally friendly products, reducing waste production, recycling as much as possible, reusing bottles and containers, and replacing broken appliances with more energy-efficient ones.

Currently, many people claim to be concerned about our planet. However, unfortunately, environmental concern does not automatically translate into the implementation of genuine Pro-Environmental Behaviors [10]. The scientific literature identifies several factors that could hinder the transition from attitude to action: time, money, information, lack of community infrastructure, and social pressures that promote consumption at the expense of conservation [6], as well as more emotional factors such as fear, anxiety, pessimism, and feelings of helplessness [11]. There comes a point when an individual is faced with a situation that forces them to decide whether to act in a way that brings short-term benefits, even though they know that this short-term advantage is counterbalanced by long-term harmful consequences for all [12].

Politicians and governments worldwide have the responsibility to raise awareness among their citizens about environmental issues and educate them on the implementation of behaviors that safeguard our planet. Numerous studies have demonstrated the significant impact that political leadership and legislation can have on the adoption of individual PEBs. The analyses conducted by [9] show that an increase in environmental spending by regional governments and the strict enforcement of environmental regulations can have a strong positive impact. The enforcement of environmental provisions not only directly promotes PEBs but also indirectly promotes them by increasing individuals’ perception of environmental risks.

Various theoretical frameworks have been developed to analyze PEBs, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior [13] and Models of Responsible Environmental Behavior [14,15]. Additionally, frameworks like the Models of Altruism–Empathy [16] and the Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) theory [17] have been explored.

The role of identity in PEBs, particularly how individuals relate to nature, has been investigated by Chernev and Blair [18]. Recent efforts have aimed to systematize literature on the relationship between PEB and identity aspects related to nature. For example, research on psychological and physical connections to nature promoting conservation behaviors [19] and the construct of Connectedness to Nature (CN) [7] has produced empirical evidence. However, this research remains unsystematized, with attempts at meta-analyses being hampered by study heterogeneity [20,21]. A systematic review approach is therefore preferred to convey the specificity and maturity of the literature.

1.3. Connectedness to Nature Literature Background

The construction of Connectedness to Nature (CN) is represented in the literature through various terms, such as Inclusion of Nature in the Self [22], Relationship with Nature [23], Dispositional Empathy with Nature [24], Love and Care for Nature [25], Commitment to Nature [26], Connectivity with Nature [27], Emotional Affinity with Nature [28], Environmental Identity [29], Nature Relatedness [23], Biophilic Design [30], and Nature-Based Solutions [31].

These constructs collectively form the trait of Human–Nature Connectedness (HNC), defining the extent to which individuals consider themselves part of nature [24].

Despite sharing common theoretical roots in self-concept theory [32], these constructs differ in their focus and measurement. Schultz’s [22] Inclusion of Nature in the Self (INS) emphasizes a cognitive perspective, describing the incorporation of nature into one’s self-concept. The author places the individual on a continuum with two extremes: on one end, there is a person who perceives themselves as completely separate from the natural environment; on the other end, there is a person who believes that all living organisms, including humans, are equal parts of the same environment. Similarly, Davis et al. [26] introduced the concept of Commitment to Nature (COM), suggesting that exposure to nature positively affects well-being [33]. On the emotional side, ref. [28] introduced Emotional Affinity Toward Nature (EATN), reflecting emotional attachments to nature. Mayer and Frantz [7] further expanded this with Connectedness to Nature (CN), emphasizing an emotional and experiential connection with nature. Geng et al. [34] define CN as an individual’s sense of connection and belonging to nature, from both a cognitive and an emotional perspective. They use this term to refer to a fundamental factor underlying attitudes toward the environment.

The literature presents two types of Connectedness to Nature: explicit, a conscious connection that an individual can express to others; and implicit, an unconscious connection that an individual is unable to articulate to others [35].

According to Wilson [36], Connectedness to Nature may have an innate biological root. The author developed the biophilia hypothesis, which posits that humans are biologically predisposed to be attached to and dependent on nature. The biophilia hypothesis suggests that our well-being increases when we strengthen our connection with nature because humans have an innate desire to connect with their surrounding environment—a remnant of the evolutionary need to understand the environment for survival [37].

According to Klassen [38], an individual’s CN depends on multiple factors, including prior knowledge, lived experiences, cultural background, and interactions or conversations with people who demonstrate care and dedication toward the environment. Wilson [36] argues that spirituality is a key factor influencing our deep relationship with nature and suggests that an ecological self is experienced through a sense of spiritual unity with nature. According to Ashmore et al. [39], the construct of collective identity plays a crucial role, as nature can be perceived as a collective community to which humans belong [29].

CN is associated with a range of variables, including environmental concern [27], biospheric value orientations [19,40], environmental identity [41], green purchasing [42], human well-being [19], personal norms [43], sustainable consumption behavior [42,44], and behavioral intentions to act pro-environmentally [45].

Several authors argue that humans were more connected to nature in the past, both physically and psychologically, compared to today [46,47]. This decline in Connectedness to Nature appears to be primarily due to the gradual shift in the population from rural to urban areas, which seems to isolate individuals from natural environmental stimuli [48]. According to Schultz [22], the increasing disconnect from nature risks leading to a reduction in appreciation and respect for nature, which may ultimately result in apathy toward environmental issues. Louv [49] coined the term “nature-deficit disorder” to explain the numerous ecological and social issues associated with the decline in contact with nature.

1.4. The Theoretical Relationship Between PEB and CN

From a theoretical point of view, several authors have linked PEB and CN. For Mayer and Frantz [7], people who feel a deep connection with nature are less inclined to engage in actions that harm the environment, as nature becomes an integral part of their sense of self. As a result, any behavior that negatively impacts the environment would also be perceived as detrimental to their own well-being. Likewise, for Schultz [50], the significance individuals place on an object is determined by the degree to which they internalize that object within their sense of self. Given that Schultz conceptualizes CN as the degree to which nature is integrated into an individual’s cognitive representation of the self, it can be inferred that the stronger an individual’s connection with nature, the more likely they are to engage in Pro-Environmental Behaviors.

However, the relationship between the self and nature is influenced by individuals’ perceptions of natural environments. Since most people perceive natural areas as independent of human action, cognitive dissonance may potentially arise [51]. Cognitive dissonance occurs when individuals experience conflicting thoughts and/or emotions about a particular concept or when their attitudes and behaviors are misaligned [52]. According to Vining et al. [51], dissonance can lead individuals to rationalize their environmentally harmful behaviors to alleviate the psychological discomfort caused by the dissonance itself, thereby justifying their contradictory actions. Resolving this conflict through changes in actual behavior rather than merely altering beliefs could lead to more environmentally responsible actions.

Cialdini et al. [53] proposed that greater closeness in interpersonal relationships enhances empathy and the willingness to help others. This concept can be hypothetically extended to the human–nature relationship, suggesting that a stronger connection with nature may cultivate empathy toward the natural world, which, in turn, could encourage individuals to adopt more considerate and altruistic environmental behaviors [20]. Similarly, according to Raymond et al. [54], individuals who develop a sense of connection and kinship with others are more likely to reject harmful environmental practices.

According to Bruni and Schultz [55], connection with nature provides the foundation for pro-environmental beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. In fact, research by Bruni [56] has demonstrated that CN is a predictor of attitudes, concerns, and intentions to engage in pro-environmental actions. Soga and Gaston [21] argue that the decline in emotional connection, coupled with reduced opportunities for direct experiences in nature, discourages positive environmental emotions, attitudes, and behaviors, thereby initiating a cycle of disaffection.

Understanding how human relationships with nature influence personal values and attitudes, how these relationships can be assessed, and the behavioral consequences they may entail, could offer valuable insights into the potential of Connectedness to Nature to promote environmental protection by encouraging individuals to adopt behaviors that benefit the natural world [57]. A better understanding of individuals and their relationships with nature has the potential to enhance our ability to effectively achieve conservation goals. Understanding how these relationships form, how they influence personal values and attitudes, and what behavioral implications they may have remains critical today.

The present systematic literature review aims to verify the theoretical link between the two constructs (Connectedness to Nature and Pro-Environmental Behavior) and the robustness of their relationship within an adequate number of empirical studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

This systematic review of the literature was conducted in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis) guidelines [58].

The PRISMA methodology is widely recognized as the standard for presenting evidence in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. It comprises a 27-item checklist and a four-phase flow diagram [58]. The primary goal of the PRISMA Statement is to assist authors in enhancing the transparency and quality of their reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Additionally, the PRISMA framework aids readers in comprehending the review process, facilitating a structured presentation of the reviewed information (Appendix A Table A3).

We developed an internal protocol inspired by the STROBE Checklist for correlational studies. In the internal protocol, we have defined: objective, method, eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy, selection process, data collection process, data item, risk of bias in individual studies, variables’ measurement, statistical analysis, data.

The literature search was conducted between November 2021 and July 2022. To access the literature, the following databases were consulted: PubMed (using only the Boolean operator AND with no filters), Google Scholar, Sociological Abstracts, PsycArticles, PsycINFO, Science Direct, and Academic Search Complete. The keywords used for the search were: “Connectedness to Nature” and “Pro-Environmental Behavior”. We did not consult Scopus because we followed the guidance provided by Bramer et al. [59] in our systematic review methodology. This guidance suggested that Scopus can often be excluded from the optimal combination of databases, particularly when Google Scholar is included. The search engine returned 2280 results.

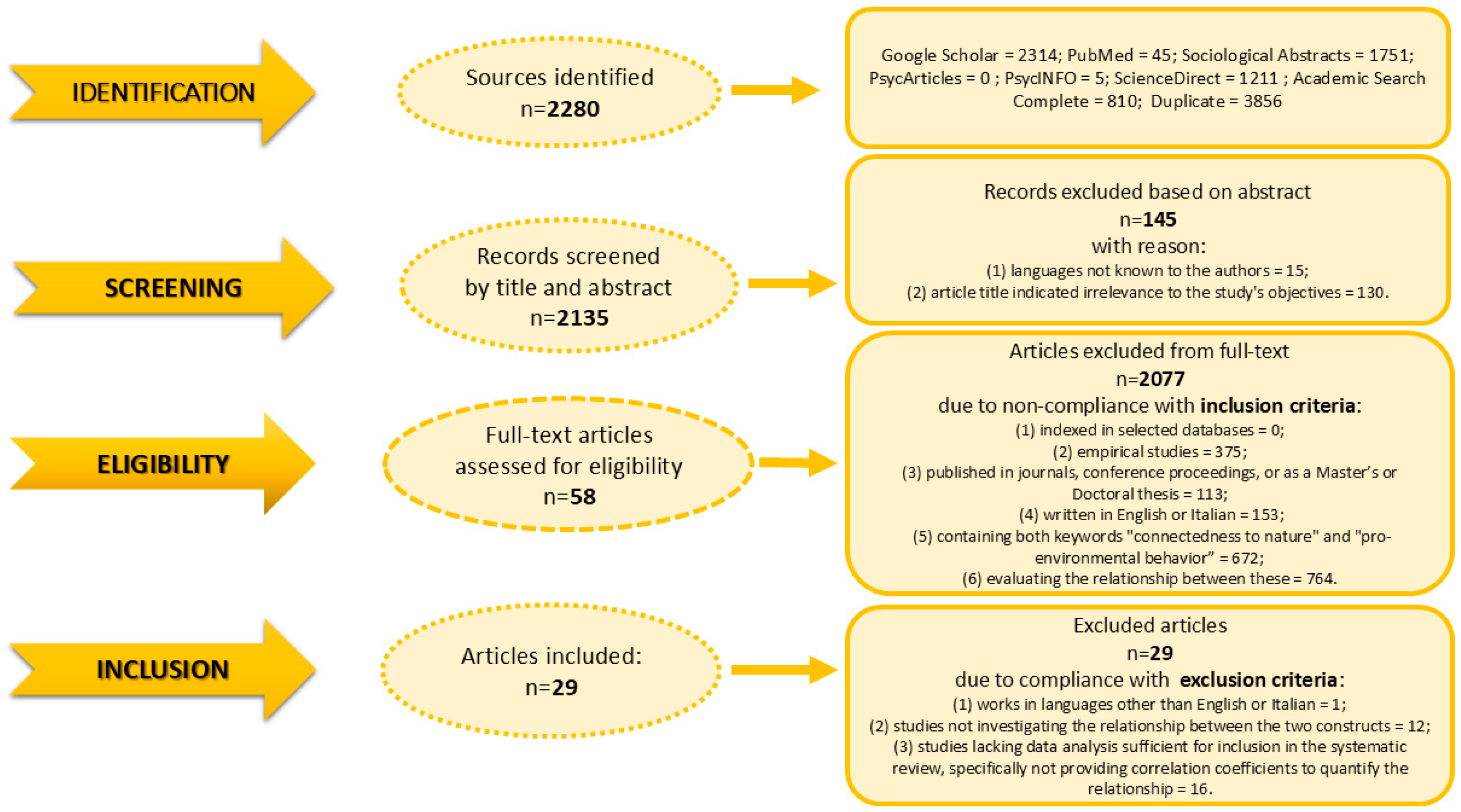

The authors (author 1 and author 2) initially identified 2280 articles (after removing duplicates) from selected databases based on predefined search criteria (see Figure 1). Abstracts in languages not known to the authors or those where the article title indicated irrelevance to the study’s objectives were excluded, resulting in the removal of 145 sources. Subsequently, the authors independently screened 2135 abstracts against the following inclusion criteria: (1) indexed in selected databases, (2) empirical studies, (3) published in journals, conference proceedings, or as a Master’s or Doctoral thesis, (4) written in English or Italian, (5) containing both keywords “Connectedness to Nature” and “Pro-Environmental Behavior”, and (6) evaluating the relationship between these constructs. This screening led to the exclusion of 2077 abstracts. The authors then accessed the full-text versions of the remaining 58 abstracts for further review. Independently, they applied the following exclusion criteria to these full texts: (1) works in languages other than English or Italian, (2) studies not investigating the relationship between the two constructs, and (3) studies lacking data analysis sufficient for inclusion in the systematic review, specifically not providing correlation coefficients to quantify the relationship. This process resulted in the inclusion of 29 studies and the exclusion of an equal number.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the flow of information during the systematic review of the literature: the number of results found, the number of works of which the abstract has been viewed, the number of works of which the complete text has been viewed, excluded articles, and included articles.

It should be noted that each source was reviewed independently by the authors, and in cases of disagreement, a third author (author 3) acted as an independent adjudicator, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. This approach helps minimize bias and ensures the consistent application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria or assessment standards [60].

The same procedure was adopted for the data collection process: the same two researchers independently extracted the correlation coefficients from the included studies, with the involvement of the same third author in case of disagreements. To synthesize the results, a narrative approach was employed, which involved structuring and summarizing the key findings from the selected studies into two tables (Table A1 and Table A2).

Since nearly all the studies observed the same direction of the effect, potential sources of heterogeneity among the study results were not further investigated. Canonical sensitivity analyses and certainty assessments, typically used in intervention studies, appear not applicable to systematic reviews of correlational and/or cross-sectional studies. These studies do not aim to estimate a specific value but rather focus on presenting a distribution. The methodological quality and potential biases of the included studies were assessed based on factors such as study design, sample size, data collection methods, statistical analyses, and reporting quality, in order to offer a comprehensive evaluation of the evidence.

2.2. Description of the Studies

This systematic review of the literature included 29 studies (see Table A1 and Table A2). These are studies that investigate the relationship between two constructs: Connectedness to Nature and Pro-Environmental Behavior. In all studies, the relationship between variables was investigated through correlation analysis.

2.2.1. Date Distribution

The studies included in this systematic review of literature are quite recent: they all date back to the last decade. Five were published in 2022. Another five in 2021 and nine in 2020. Five studies date back to 2018, one to 2016, three to 2015 and one, the most distant, to 2014.

2.2.2. Geographical Distribution

The studies were carried out in different countries: from Europe to Asia, from America to Oceania. The geographical distribution is as follows: 4 were carried out in the United States, another 4 in Spain, 3 in Australia, 2 in Italy, 2 in Greece, 2 in England, 2 in Canada, 2 in China, 2 in Mexico, 1 in Brazil, 1 in Sweden, 1 in Pakistan, 1 in India, 1 in New Zealand, 1 in the Philippines, and 1 in Serbia.

2.2.3. Sample Size

The studies used rather large samples: only four samples are less than 100 (sample sizes of 76, 97, 78 and 54), 22 samples are in the order of hundreds (sample sizes: 360, 688, 973, 150, 224, 400, 400, 113, 489, 212, 423, 352, 307, 159, 185, 245, 430, 589, 382, 211, 296, 299), finally, the other 4 samples are in the order of thousands (4700, 1251, 4960, 1068).

2.2.4. Proportion of Males and Females

With reference to the proportion of male to female, the largest group comprising 19 studies reports a higher percentage of females than males (proportion of females: 68.06%, 50.43%, 62.5%, 58%, 54%; 75%, 51.41%, 61.7%, 51.42%, 56.03%, 96.2%, 67%, 51.8%, 58.1%, 63.3%, 77%, 73%, 66.7%, 60.5%, and 59.1%). A small second group of four studies reported a higher proportion of males (proportion of males: 51.32%, 61.86%, 55.75%, and 98%). Finally, a final group of 6 studies does not report information about the percentage of females and males in the sample.

2.2.5. Sampling Age

Studies present a rather varied age distribution of sampling. A total of 3 studies considered a specific population, that of children: two studies representing a range of 9–12 and one study representing a range of 4–12. The second group of studies, comprising 10 studies, focused on some of the narrower and others wider age groups including adolescents and/or young adults and/or adults (age range considered: 16–24, 9–21, 23–30, 10–19, 18–40, 18–35, 18–46, 18–48, 17–56, and 20–59). The third group of studies, which includes 6, takes into account very large age groups ranging from adolescents to the elderly (age groups considered: 18–75, 18–60, 16–95, 18–75, 18–65, and 20–82). The last group of studies, consisting of 10 studies, does not report information about the age range of the sample used.

2.2.6. CN Measuring Instruments

The variable “Connectedness to Nature” was measured in the 29 works using different tools. The most common measure is the Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7], which has been used in 15 research projects. Among these, Geng et al. [34] used the Chinese version of the scale; Hongxin et al. [61] used the 13-item version adapted by Perrin and Benassi [62]; and Apaoloaza et al. [63] used 7 items based on Mayer and Frantz’s scale [7]. In 3 works, the authors used the Connection to Nature Index (CNI) [64]. In 2 works, the adapted short version of the Disposition to Connect With Nature Scale [65] was used, while in another study the 12-item short version of the Disposition to Connect With Nature Scale [66] was used by the authors. In the other 2, research authors used the Inclusion of Nature in the Self scale (INS) [67]. Other measures used in the studies that are part of the revision are as follows: the Nature Connection Index (NCI) [68]; the 6-item short form of the Nature Relatedness Scale [69]; three items extrapolated from the article published by Gosling and Williams [70]; a single graphical item from Schultz [22] where participants were asked to choose one of the seven figures presented that best represented their relationship with nature; five items built ad hoc by Iverson [71]; and a question extrapolated from the national survey “Outdoor Recreation in Change” by [72].

2.2.7. PEB Measurement Instruments

The Pro-Environmental Behavior variable has been measured in each research in a different way. Some authors used a validated tool, others used only a few items extrapolated from several successful tools; still, others created their own measure based on previous tools, and finally, others asked one or more questions to try to capture this construct. Six studies used the General Ecological Behavior Scale (GEBS) of Kaiser and Wilson [73] and Kaiser [74]. Among these, Krettenauer et al. [75] used an adapted version of this scale; and Duron-Ramos et al. [76] and Barrera-Hernández et al. [77] used the adapted version for use with children by Fraijo Sing et al. [78]. Two researchers used a modified version of the Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale by Whitmarsh and O’Neill [79]. Two other searches used the Pro-Environmental Behaviors Scale (PEBS) of Markle [80]. The other tools that have been used in these studies are: the self-reported PEB Scale by Larson et al. [81]; the Schultz et al. [82] Environmental Behavior Scale; the College Students’ Environmental Behaviors Questionnaire (CSEBQ) as amended by Shen [83] from the Behavior-based Environmental Attitude scale [84]; the scale of PB adapted by Robertson and Barling [85]; Alisat and Reimer’s [86] Environment Action Scale; Cheng and Monroe’s [64] Connection to Nature Index (CNI); a measure of general PEBs by Dutcher et al. [27] and Kaiser, Wolfing, and Fuhrer [87]; a questionnaire on Pro-Environmental Behaviors adapted from Markle [80] and Menardo et al. [88]; Environmental Questionnaire used by [65]; a measure of the frequency of engaging in 22 pro-environmental behaviors by Whitmarsh et al. [89]; and a measure of 16 items adapted by Binder, Blankenberg and Guardiola [90] asking participants to indicate the frequency with which they carry out pro-environmental activities. In some studies several items have been extrapolated from various instruments: in one, the authors used 10 items derived from previous studies (e.g., [73,81]) to measure environmental action and personal practices; and in another study, 6 items of pro-environmental behavior were used based on the following works [91,92,93]. Finally, a study used seven items from the Student Environmental Behavior Scale of Markowitz et al. [94] and an additional item from Panno et al. [95]. In an article, the authors developed a real multidimensional measure of Pro-Environmental Behavior (22 items) based on previous works [73,81,86]. In another study, Iverson [71] built ad hoc 7 items to measure Pro-Environmental Behavior. Finally, in other studies, the authors asked participants questions that could capture the construct: in one study, 6 questions from the national survey “Outdoor Recreation in Change” [72] were used, and participants were asked to respond to a list of items following the question: “What of the following actions you do for environmental reasons”; in another study, the PEB was measured by the question: “Have you changed your behavior due to environmental reasons?” [96]; in another, the research respondents were asked to indicate what environmental activities they had undertaken in the previous 12 months [97]; in a latest study, in order to capture sustainable consumption the authors asked individuals to mark the degree to which they performed different actions, while to capture activism they asked individuals to mark the frequency with which they participate in demonstrations in support of the environment [98].

2.3. Quality Assessment

For the quality assessment, we utilized the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines [99], adapting this tool for a systematic review of correlational studies within the field of social sciences. We addressed all the guiding questions from the JBI checklist.

We responded affirmatively to item 1, as the inclusion and exclusion criteria for our review were clearly defined a priori (Figure 1) and rigorously applied during the selection process. We answered affirmatively to item 2, as we provided a detailed description of the samples in the included studies, specifically considering gender, age, and nationality (Table A1).

In accordance with items 3 and 4 of the JBI guidelines, we conducted an assessment of the psychometric properties of all measurement instruments employed in the included studies. Specifically, reliability was evaluated based on internal consistency, using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, applying the following standard criteria: α < 0.60 = poor; 0.60 ≤ α < 0.70 = questionable; 0.70 ≤ α < 0.80 = acceptable; 0.80 ≤ α < 0.90 = good; α ≥ 0.90 = excellent. Regarding validity, we considered evidence from confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) and correlation tables to assess convergent and divergent validity. Based on these criteria, we assigned a qualitative label to each instrument: excellent (validated scale with both CFA and convergent/divergent validity evidence); good (adapted/modified/new scale with both CFA and convergent/divergent validity evidence); average (adapted/modified scale with either CFA or convergent/divergent validity evidence); and poor (ad hoc scale with insufficient validity evidence, or adapted/modified scale without any validity evidence). The detailed results of this assessment for the instruments used to measure Connectedness to Nature are presented in Appendix A Table A4, whereas details regarding the reliability and validity of the instruments measuring Pro-Environmental Behavior are provided in Appendix A Table A5.

Items 5 and 6 were not applicable to our research, as we analyzed univariate relationships rather than multivariate ones, and thus confounding factors were not considered.

Lastly, we responded affirmatively to items 7 and 8, as we ensured that the outcomes extracted from each study were measured in a valid and reliable manner, and that the authors employed correlation statistical analysis, which was essential for our study to extract the correlation coefficients, as reported in Table A1.

3. Results

The results show that there is a relationship between Connectedness to Nature and Pro-Environmental Behavior. All 29 studies report a significant and positive correlation between the two variables, only in one case [100] the correlation between CN and a specific PEB construct is not significant.

Correlations vary from a minimum of r = 0.09 to a maximum of r = 0.62.

In the various studies, the variable Pro-Environmental Behavior has been investigated taking into consideration different types of behavior: 28 studies (all except: [100]) analyzed individual behaviors (for example: recycle, buy environmentally sustainable products, buy cars with low fuel consumption); 4 of these ([97,98,101,102]) over individual behaviors, have also investigated those of activism (e.g., participate in demonstrations that support the environment, vote political parties that support the environment, and volunteer) and a single study [100] has dealt exclusively with activism.

With regard to individual Pro-Environmental Behaviors, the 28 studies that took this dimension into account investigated different categories such as sustainable consumption, recycling, transport use, behavior in the domestic environment, purchase of organic food, storage, and waste reduction.

As for activism, the different authors have referred to this concept taking into account different actions, including: participating in demonstrations that support the environment, voting for parties that support environmental conservation policies, donate contributions to organizations struggling to protect the environment, be part of an environmental organization, write letters to politicians to fight for environmental causes, volunteer for the environment, raising awareness of environmental issues, participating in nature conservation events such as planting trees.

In agreement with Gignac and Szodorai [103], the recent guidelines on the interpretation of the dimensions of Pearson’s correlation effects in the field of the search for individual differences, it is recommended to consider the correlation of 0.10 as relatively small, of 0.20 as average and of 0.30 relatively large. These guidelines were specifically developed to offer empirically representative thresholds for evaluating effect sizes in psychological research. While Cohen’s cut-offs (0.10, 0.30, and 0.50) have been widely used, they were originally thought of as general heuristics across various research fields and were not derived from empirical data in psychological science. In contrast, Gignac and Szodorai’s cut-offs are based on a comprehensive meta-analysis of over 700 correlations in psychological research, making them more representative of the actual distribution of effect sizes in this domain. Nonetheless, beyond relying on such benchmarks, the r coefficient can still be interpreted in a more objective way since it inherently represents an index of the strength of an association (i.e., when squared and multiplied by 100—i.e., r2 × 100, it expresses the percentage of the common variance among variables).

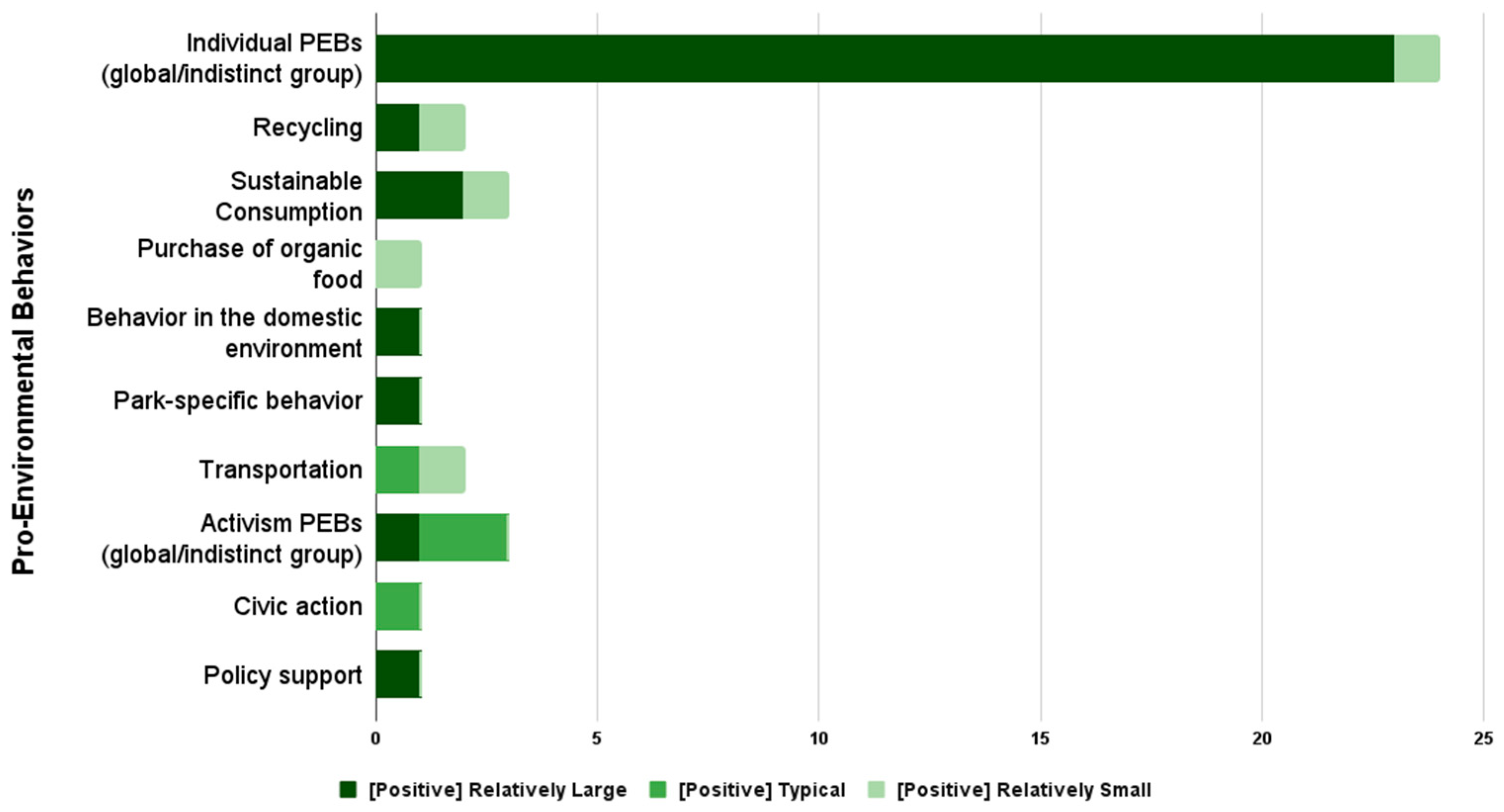

The 23 studies that analyzed the correlation between Connectedness to Nature and the general group of individual Pro-Environmental Behaviors all reported a large effect size (range r = 0.28–0.62), only in one case [96] the effect size was small (r = 0.13). The three studies [98,101,104] that dealt with the association between CN and sustainable consumption highlighted two large effect sizes and one relatively small (respectively: r = 0.37; r = 0.38; r = 0.17). The two studies [101,104] that studied the relationship between CN and transport found two different effect dimensions: one medium and one small (r = 0.21; r = 0.09), respectively. The two studies [101,104] that dealt with the relationship between CN and recycling found two different effect dimensions: one large and one small (r = 0.44; r = 0.11), respectively. The dimension of the effect of the relationship between CN and behavior in the domestic environment [101], park-specific behavior [43], and purchase of organic food [104] was large for the first two sizes and relatively small for the last size (respectively: r = 0.47; r = 0.32; r = 0.16).

The five studies that analyzed the association between Connectedness to Nature and behaviors of activism reported correlation coefficients from medium to relatively large. In a study [98], activism is understood by the authors as a frequency of political participation in demonstrations that support the environment. In this study the size of the effect is relatively large (r = 0.28). In another article [102], the authors use the construct of environmental action, including this concept; for example, vote for political parties that support environmental conservation policies, contribute financially to environmental causes, be an active member of an organization, write letters to politicians about environmental causes, and take part in environmental protests. In this case, the size of the observed effect is essentially typical (r = 0.19). In a third study [101], the authors distinguish between civic action and policy support by finding an average effect (r = 0.24) and a large effect (r = 0.35), respectively. In further research [97], the authors talk about nature conservation behavior, including in this construct, being a member of an environmental organization, volunteering for the environment, donate a contribution at least every three months to support an environmental organization, and donate your time at least once every three months to provide help in an environmental organization. The correlation coefficient found shows an almost typical effect size (r = 0.19). The last study [100], distinguishes between two constructs, participatory action and leadership action (by participatory actions, the authors refer to activities such as engaging in nature conservation events like tree planting, discussing environmental issues with others, participating in educational events focused on environmental concerns, and using online platforms to raise public awareness about these issues. In the case of leadership actions, the authors describe activities such as providing financial support to a cause or dedicating time to work with a group or organization that addresses the connection between environmental issues and other social challenges, such as justice or poverty.). In the university population, the correlation between CN and participatory action was average (r = 0.23), and that between CN and leadership action was not significant; while in the professional population, both correlations were average (r = 0.24 and r = 0.27, respectively).

A visual summary of the main findings is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The bar chart displays the strength and direction of the association between specific Pro-Environmental Behaviors (PEBs) and Connectedness to Nature (CN). The y-axis represents different PEBs, while the x-axis shows the number of studies assessing the relationship between each PEB and CN. The color scheme indicates the strength and direction of the observed associations.

4. Discussion

Global environmental issues and climate change require collective efforts and people psychology [105,106]. Emerging scientific literature has highlighted how a change in identity, a construct underlying the concept of Connection to Nature, can foster a change in PEBs [107,108].

The majority of studies included in this review examined the correlation between Connectedness to Nature (CN) and a general Pro-Environmental score, which does not distinguish between different types of individual Pro-Environmental Behaviors (PEBs). This total score is based on the adoption of multiple PEBs. Notably, most of these studies (22 out of 23) that explored the relationship between CN and the “undifferentiated” individual PEB reported a large effect size.

For those studies that instead analyzed the relationship between CN and specific individual Pro-Environmental Behaviors, the most common PEB were as follows: sustainable consumption, transport, and recycling. Three studies focused on sustainable consumption, with two reporting large effect sizes, and one showing a relatively small effect size. In addition, the two studies examining recycling behaviors reported one large effect size and one small effect size. Similarly, the two studies on transportation choices found one typical and one small effect size.

This variability may arise from the fact that the same behavior can be influenced by different processes for different individuals. Some actions are driven by faster, more instinctive processes, while others are shaped by slower, more reflective processes (e.g., when considering sustainable purchasing, one could distinguish between impulse buys and reasoned purchases). As a result, the varying measurement methods used across studies to assess PEBs may have, in some cases, captured more instinctive behaviors, while in others, they may have focused on more deliberate actions. This variability in terms of effect size within the same type of PEB can also be explained through the goal frame theory [109]. The authors identified a range of sub-goals, which they categorized into three dimensions, referred to as goal frames: hedonic goal frame, normative goal frame, and gain goal frame. A normative goal frame involves sub-goals related to the appropriateness of one’s actions, with behaviors such as contributing to a clean environment being considered appropriate [110]. According to these researchers, there is a relationship between the normative goal frame and Pro-Environmental Behavior. Therefore, when the regulatory aspect is dominant in a given sample, a stronger relationship between Connectedness to Nature and PEB is expected, as individuals will be motivated to act in a moral and appropriate manner before evaluating the environmental impact of their choices. Conversely, if the hedonic or gain aspects are more prominent in the sample, the relationship between CN and PEB is likely to be weaker, as behavior will be more influenced by these goals. Furthermore, the variation in effect sizes across studies examining the same type of PEB may also be influenced by the considerable heterogeneity of the measurement instruments employed across studies. Indeed, the different tools used to assess both Connectedness to Nature and Pro-Environmental Behavior possess diverse psychometric properties, which may have contributed to differences in the strength of the observed associations. For a detailed overview of the reliability and validity properties of the instruments used to assess CN and PEB, see Appendix A Table A4 and Table A5, respectively.

Four studies differentiated between individual behaviors and activist behaviors, while a single study focused exclusively on activist behaviors. Behaviors of activism are behaviors that require a greater social commitment to environmental causes and that have an immediate and significant impact at the collective level (e.g., join demonstrations that fight for environmental causes, donate time and/or money to environmental organizations, and vote for political parties that care about environmental issues). As for activist behavior, the effect sizes of the correlations found vary from medium to large. The variability observed in the different effect sizes may be attributed to the significant differences in the types of activism behaviors considered across the studies (e.g., voting parties that support environmental policies, and participating in nature conservation events such as planting trees).

With regard to the four studies that compared individual PEB and CN versus activist PEB and CN, there is a clear difference in the effect size in three studies out of four, with a higher effect size between individual PEB and CN. The stronger correlation between Connectedness to Nature and individual behaviors, as compared to activist behaviors, may be due to the fact that activist behaviors typically require greater resources—such as cognitive effort, time, and money—than individual behaviors, which are generally less demanding and costly. Consequently, fostering activist behaviors may require a higher level of Connectedness to Nature than what is needed to encourage individual PEBs. Social and institutional changes may be necessary to make activism behaviors more accessible and less resource intensive for individuals (e.g., more voluntary associations established in the small territory, more people who contribute in time and/or money so that a single minimum contribution is sufficient, and more important institutions and political parties that promote protests/pro-environmental activities).

4.1. Limitations of Included Studies

The risk of bias for each included study was independently assessed by the same initial two reviewers, with the involvement of a third author as a mediator in case of disagreement.

Regarding the limitations of the included studies, firstly it is crucial not to overlook the fact that all the included studies implemented a correlational research design, and thus causal inferences are not possible. In all studies, we cannot disregard the potential sampling biases resulting from the use of convenience sampling techniques (i.e., non-probabilistic sampling). Furthermore, the majority of the included articles were conducted on samples predominantly composed of university students and women, this poor sample representativeness limits the generalizability of the results. Then, the majority of the analyzed data were derived from self-report measures; therefore, we cannot underestimate the potential distortion effects, particularly recall bias and social desirability bias. The measurement instruments for PEBs typically concentrate on specific behaviors, with varying ranges depending on the study under consideration. This limitation restricts the generalizability of these behaviors to the broader category of PEBs, which is an extremely vast and heterogeneous category. Ultimately, only one study investigates intercultural differences (and only between two countries).

4.2. Limitations of This Study

This systematic literature review is not without limitations. Firstly, the extensive variability in the nomenclature associated with Connectedness to Nature must be acknowledged (the construct of CN is represented in the literature through various terms, such as Inclusion of Nature in the Self, Relationship with Nature, Dispositional Empathy with Nature, Love and Care for Nature, Commitment to Nature, Connectivity with Nature, Emotional Affinity with Nature, Environmental Identity, Nature Relatedness, Biophilic Design, and Nature-Based Solutions). The chosen keywords, though carefully selected, may not encompass every study on the topic. However, these keywords are expected to capture the majority of relevant literature. Another limitation related to the terminology concerns the use of the keyword ‘Pro-Environmental Behavior’, which employed the American English spelling of ‘behavior’. This choice was based on the rationale that the vast majority of authors in the field use the American version. However, it is important to note that this decision may have excluded articles that only use the British English spelling, ‘behaviour’. Further limitations of this study are rooted in the omission of an examination of potential publication bias, given the heterogeneous nature of the included studies concerning the definition of Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Additionally, the restricted generalizability of the findings is a consequence of the predominant homogeneity observed in the samples, primarily composed of young cisgender women and university students across the included studies. Finally, considering that among the 29 included articles, there are 28 in English and one in Italian, we cannot rule out the possibility of potential linguistic biases.

4.3. Potential Impact

The findings of this study contribute to the literature on Pro-Environmental Behaviors and Connectedness to Nature. Firstly, the present work suggests the usefulness of strengthening people’s Connectedness to Nature, given the potential positive impact of CN on PEB. This has practical implications as it suggests that pro-environmental interventions may be more effective if they focus not directly on behaviors but rather on individuals’ attitudes, particularly on the construct of Connectedness to Nature.

Furthermore, the wide variability of the correlation coefficients observed (partly due to the considerable heterogeneity within the class of PEBs) suggests the possibility that certain categories of Pro-Environmental Behaviors may be more strongly associated with Connectedness to Nature than others. This review provides an initial overview indicating that sustainable consumption, recycling, domestic behavior, and park-specific behavior appear to be the behaviors most strongly associated with CN. However, given the variability noted by different authors, even within the same category, further studies in this field are desirable to systematically investigate the strength of these associations, enabling more robust conclusions.

This study suggests to activists involved in environmental awareness campaigns that these initiatives could be more effective if, in addition to promoting the appropriate social norms related to Pro-Environmental Behaviors, they also emphasize an experiential and emotional dimension. By encouraging individuals to engage directly with nature, these campaigns can help strengthen the connection between people and the natural environment.

The study suggests that public entities could promote Pro-Environmental Behaviors by increasing access to green spaces and organizing nature-based activities while encouraging community participation. This approach would enhance the likelihood that citizens have experiences in nature, thereby strengthening their connection to the natural environment.

Future studies in this regard could explore the potential of experiential nature immersion training in catalyzing enduring behavioral change [111,112], as well as investigate the efficacy of mindfulness experiences within natural environments [113] and the influence of exposure to nature documentaries [114] on the development of Connectedness to Nature and its subsequent impact on Pro-Environmental Behavior.

Moreover, it would be crucial to assess not only the interventions’ capacity to foster PEBs but also their effectiveness in enhancing the overall well-being of individuals [98].

5. Conclusions

Overall, the included studies in this systematic review supported a positive association between Connectedness to Nature and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. However, the robustness of this relationship seems contingent on the specific type of PEB under consideration, indicating that recycling and sustainable consumption exhibited a stronger association with CN compared to other PEBs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G., G.V. and M.D.; methodology, G.V. and M.D.; formal analysis, G.V. and M.D.; investigation, G.V. and M.F.; data curation, G.V. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.V. and M.F.; writing—review and editing, A.G., G.V., M.F. and M.D.; supervision, A.G. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All the articles selected are presented in the appendix section.

Acknowledgments

We thank the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Project “PHOENIX: The Rise of Citizen Voices for a Greener Europe” (grant agreement No 101037328) for supporting and promoting this systematic review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Main features of the studies examined: references, sample size, gender distribution, age distribution/mean age, Country, Connectedness to Nature measure, Pro-Environmental Behavior measure, and results.

Table A1.

Main features of the studies examined: references, sample size, gender distribution, age distribution/mean age, Country, Connectedness to Nature measure, Pro-Environmental Behavior measure, and results.

| Ref. | Sample Size | Gender Distribution | Age Distribution/Mean Age | Country | Connectedness to Nature Measure | Pro-Environmental Behavior Measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [113] | 360 | 31.9% M 68.1% F | 16–24 M = 20.11 | Arizona, USA | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7] | A modified version of Pro-Environmental Behavior scale (PEB) [79]. | r = 0.34, p < 0.001 |

| [75] | 688 | 49.6% M 50.4% F | 9–21 M = 15.42 | Canada and China | A shortened and adapted version of the instrument developed by Brügger et al. [66] | An adapted version of the General Ecological Behavior scale (GEB) [73]. | r = 0.42, p < 0.001 |

| [98] | 973 | NR | NR NR | Granada, Spain | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7] | In order to capture sustainable consumption (s.c.) they asked individuals to score the degree with which they perform several actions. In order to capture activism (a) they asked individuals to score the frequency with which they participate in demonstrations in support of the environment. | r(s.c.) = 0.36, p < 0.01; r(a) = 0.276, p < 0.01 |

| [102] | 400 | NR | 18–75 NR | City of Thessaloniki, Greece. | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7] | They used 10 behavioral items derived from previous studies, e.g., [73,81]. The authors considered two dimensions of pro-environmental behavior: environmental action (e.a.) and personal practices domains (p.p.). | r(p.p.) = 0.47, p < 0.01; r(e.a.) = 0.19, p < 0.01 |

| [115] | 224 | 37.5% M 62.5% F | NR M = 23.64 | Brazil | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7] | Self-reported PEB Scale [81] | r = 0.44, p < 0.01 |

| [116] | 1068 | NR | 18–46 M = 21.12 | Granada, Spain | 14 items adapted from Mayer and Frantz [7] | Sixteen items, adapted from Binder, Blankenberg, and Guardiola [90], which asked participants to indicate how often they perform pro-environmental activities. | r = 0.40, p < 0.001 |

| [101] | 150 | 42% M 58% F | NR M = 40.32 | Greece | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7]; Iclusion of Nature in the Self scale (INS) [67] | They draw on the work of Kaiser and Wilson [73]; Alisat and Riemer [86] and Larson et al. [81] to develop a multi-dimensional measure of environmental behavior (22 items). The scale encompasses six potential behavior domains: civic actions (c.a.), policy support (p.s.), recycling (r.), transportation (t.), behavior in the household setting (b.h.s.) and consumerism (c.). | r(CNS,c.a.) = 0.24; r(CNS,p.s.) = 0.35; r(CNS,r.) = 0.438; r(CNS,t.) = 0.214; r(CNS,b.h.s.) = = 0.48; r(CNS,c.) = 0.384; r(INS,c.a.) = 0.334; r(INS,p.s.) = 0.419; r(INS,r.) = 0.333; r(INS,t.) = 0.248; r(INS,b.h.s.) = = 0.536; r(INS,c.) = 0.496; For all coefficients p < 0.01 |

| [76] | 400 | 46% M 54% F | 9–12 M = 10 | Mexico | Children’s Affective Attitude Toward Nature Scale [64] | General Ecological Behavior Scale [74], adapted for use with children by Fraijo Sing et al. [78] | r = 0.46, p < 0.01 |

| [35] | 76 | 25% M 75% F | 18–60 M = 33 | Australia | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7] | Environmental Behavior scale [82]. | r = 0.36, p < 0.01 |

| [34] | 113 | 55.8% M 44.2% F | 23–30 M = 26.54 | China | A Chinese version of the CNS [7] and a modified Chinese version of the computerized IAT based on that of Schultz and colleagues [117] was created to measure the RT (ms) needed to classify words associated with natural and built environments. | College Students’ Environmental Behaviors Questionnaire (CSEBQ) modified by Shen [83] from the Behavior-based Environmental Attitude scale [84] and a situational simulation experiment (s.s.e.). | r(CNS,CSEBQ) = 0.39, p < 001; r(IAT,s.s.e.) = 0.56, p < 0.001 |

| [97] | 4960 | 48.6% M 51.4% F | 16–95 NR | England | The Nature Connection Index (NCI) [68] | Environment-related activities undertaken during the previous 12 months. The authors consider two types of pro-environmental behavior: household behaviors (h.b.) and nature conservation behaviors (n.c.b.). | r(NCI, h.b.) = 0.34, p < 0.001; r(NCI, n.c.b.) = = 0.19, p < 0.001 |

| [118] | 97 | 61.9% M 38.1% F | 10–19 14.24 | Spain | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7] | Pro-Environmental Behaviors Scale (PEBS) [80]. | r = 0.397, p < 0.001 |

| [119] | 1251 | 51.3% M 48.7% F | NR NR | Canada | Krettenauer’s adapted version of the measure developed by Brügger and colleagues [66] | Environmental Questionnaire used by [65]. | r = 0.53, p < 0.01 |

| [61] | 489 | NR | 18–40 NR | Pakistan | The scale of CN was adapted from Perrin and Benassi [62] | The scale of PB was adapted from Robertson and Barling [85]. | r = 0.57, p < 0.05 |

| [100] | 212 | NR | 18–35 NR | India | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7] | Environment Action Scale [86]. The study investigates two types of behavior: participatory action (p.a.) and leadership action (l.a.). | University students: r(CN, p.a.) = 0.227, p < 0.01; r(CN, l.a.) = −0.058; not significant. Professionals: r(CN, p.a.) = 0.243, p < 0.05; r(CN, l.a.) = 0.265, p < 0.01 |

| [120] | 423 | 38.3% M 61.7% F | NR NR | New Zealand | A 12-item version of Brügger et al. [66] Disposition to Connect With Nature Scale. | The General Ecological Behavior Scale [73,74] | r = 0.48, p < 0.001 |

| [121] | 352 | 48.6% M 51.4% F | 4–12 M = 7.63 | Australia | Connection to Nature Index (CNI) [64] | Connection to Nature Index (CNI) [64]. | r = 0.46, p < 0.001 |

| [43] | 307 | 44% M 56% F | NR NR | Australia | Seven items derived from Gosling and Williams [70] | Six Pro-Environmental Behavior items based on Tonge et al. [91,92,93]. | r = 0.323, p < 0.001 |

| [104] | 4700 | NR | 18–75 NR | Sweden | Three item from the “Outdoor Recreation in Change” National Survey [72]. Participants were asked to respond to three items following the question: “To be in nature usually makes me feel or experience”: (i) A heightened sense about the interplay of nature, that everything is connected. (ii) A feeling that the city is dependent on the surrounding nature. (iii) A feeling that all people, including myself, are united and a part of nature. | Six questions from the “Outdoor Recreation in Change” National Survey [72]. Participants were asked to respond to a list of behavioral items following the question: “What of the following do you do for environmental reasons”: (i) I choose to walk, ride the bicycle or use public transportation instead of going by car. (ii) I collect and separate household waste. (iii) I eat organically produced food. (iv) I purchase green eco label products. (v) I reduce my speed when driving. (vi) I choose the train over air travel. | r(i) = 0.09; r(ii) = 0.11; r(iii) = 0.16; r(iv) = 0.17; r(v) = 0.20; r(vi) = 0.13 p < 0.008 for all coefficients. |

| [122] | 159 | 3.8% M 96.2% F | NR M = 25.56 | Italy | A single graphical item from Schultz [22]. Participants were asked to choose one of the seven figures presented which better represented their relationship with nature. | A self-reported measure of general PEBs composed of 14 item from [27,87]. | r = 0.52, p < 0.001 |

| [123] | 185 | 33% M 67% F | 18–48 M = 21.5 | USA | CNS [7] | Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale [80]. | r = 0.38, p < 0.001 |

| [63] | 245 | 48.2% M 51.8% F | 17–56 M = 19.69 | Spain | Seven items based on Mayer and Frantz’s scale [7] | Seven items of the Student Environmental Behavior Scale [94] and an additional item [95]. | r = 0.62, p < 0.01 |

| [124] | 430 | 41.9% M 58.1% F | 20–59 M = 31.2 | Italy | Connectedness to Nature Scale [7] | Pro-environmental behaviors’ questionnaire (adapted from Markle [80] and Menardo [88]). To this were added four questions on the purchase of products, another question on environmental citizenship and one on separate waste collection. | r = 0.28, p < 0.001 |

| [125] | 589 | 36.7% M 63.3% F | 18–65 M = 30.06 | Philippines | Connectedness to Nature Scale [7] | General Measure of Ecological Behavior [74]. | r = 0.40, p < 0.01 |

| [71] | 78 | 23% M 77% F | NR NR | USA | Five items [71] | Seven items [71]. | r = 0.42, p < 0.0001 |

| [96] | 382 | 98% M 2% F | 20–82 41.4 | Serbia | Inclusion of Nature in the Self Scale [67] | The EB in this study was measured by the question: “Have you changed your behavior due to environmental reasons?”. | r = 0.13, p < 0.01 |

| [126] | 211 | 27% M 73% F | NR 26.57 | England | The short form of the nature relatedness scale [69] | A measure of the frequency of engaging in 22 Pro-Environmental Behaviors [89]. | r = 0.59, p < 0.001 |

| [127] | N1 = 54 N2 = 299 | 33.3% MN1 66.7% FN1 39.5% MN1 60.5% FN1 | NR N1 NR N2 MN1 = 36.15 MN2 = 43.3 | USA | Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) [7] | General Ecological Behavior Scale (GEBS) [73] in N1 and Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEB) [79] in N2. | r(CNS,GEBS) = 0.38, p < 0.01; r(CNS,PEB) = 0.43, p < 0.001 |

| [77] | 296 | 40.9% M 59.1% F | 9–12 10.42 | Mexico | Connection to Nature Index (CNI) [64] | Eleven items from the General Ecological Behavior Scale of Kaiser [74] adapted for use with children by Fraijo Sing et al. [78]. | r = 0.49, p < 0.001 |

Table A2.

Main characteristics of the studies examined: references, main results, limitations of the study, and risk of distortion.

Table A2.

Main characteristics of the studies examined: references, main results, limitations of the study, and risk of distortion.

| Ref. | Main Findings | Limitations | Risk of Biases |

|---|---|---|---|

| [113] | Statistically controlling mindfulness, Connectedness to Nature is significantly and positively associated with pro-environmental behavior. Connectedness to nature mediates the relationship between mindfulness and pro-environmental behavior. | The study was aimed only at university students. The research examined daily Pro-Environmental Behaviors (e.g., recycling, the use of reusable shopping bags), and therefore, the generalization of these findings to other types of Pro-Environmental Behaviors should be implemented with caution. It is important to note that the results are correlative, so the data cannot support causal relationships. The research was carried out in Arizona, it would be desirable to replicate it in other countries. | Sampling bias due to convenience sampling technique (non-probability sampling). Participants self-reported the average frequency of their engagement in 17 daily Pro-Environmental Behaviors, but self-reports may contain recall errors, in addition to distortions that can occur due to bias of social desirability. |

| [75] | Connectedness to nature is significantly and positively associated with pro-environmental behavior in both Canada and China. | Drawing is correlative, so it does not allow causal inferences. Only two cultural groups were compared, so the question remains whether the cultural differences documented in the study are unique for the two countries or represent more general factors applicable to a wider spectrum of cultures. | Sampling of convenience and non-representative. While the authors focused on distinguishing collectivism–individualism, there might be other factors that produced the differences between the Canadian and Chinese samples. Measures are self-reported, so biases of social recall and desirability are possible. |

| [98] | There is a significant and positive correlation between Connectedness to Nature and two types of pro-environmental behavior: sustainable consumption and activism. | The sample is adequate for statistical analysis, but a larger sample size would have been ideal. Because we work with correlative data, causality cannot be affirmed. The study was conducted in Spain, it would be desirable to replicate it in other contexts. | Sampling of convenience and non-representative. The environmental activism indicator leaves room for improvement: it is based on participation in pro-environmental events and could be enriched by including other dimensions of activism. Data are self-reported, so it can be distorted due to recall biases and social desirability. |

| [102] | There is a correlation between Connectedness to Nature and two dimensions of pro-environmental behavior: personal practices and environmental action. | It would be useful to replicate the study also in other socio-cultural contexts. The study has a correlational nature, so cause and effect inferences cannot be made. | Only self-reported environmental behavior was measured, not real behavior, which raises a concern about the bias of social desirability over possible recall errors. |

| [116] | Pro-environmental behavior mediates the link between Connectedness to Nature and food adhesion, fully explaining why people who feel more connected to nature report greater adherence in the short term and are more likely to continue their diet in the future. A high Connectedness to Nature predicts a high PEB index. | The participants are all university students. The study has a correlative nature, which undermines the possibility of making causal inferences. Many variables have been evaluated with binary responses. There are additional factors that can play a role in vegetarian dietary adherence, for example, it would be useful to consider constructs such as sensitivity to disgust, moral foundations, other relevant values, and self-control when considering meat consumption. The sample was placed in a geographical area where many people follow a Mediterranean diet, this justifies intercultural validation, in order to demonstrate the reliability of the effects observed outside Spain. | The authors based themselves on what was self-reported by the participants, so there may be distortions due to recall errors and biases of social desirability. Sampling of convenience. |

| [115] | The results suggest that current experiences of adults in nature have a positive effect on their PEB, this effect is partially explained by the Connectedness to Nature. Connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behavior are positively associated. | The participants are all university students. Most of them are women. It would be useful to replicate the study in other developing and developed countries so as to allow a generalization of the results. The study is correlative, so no causal explanations can be made. | Sampling of convenience. The data were self-reported by the participants, so there is a risk of recall errors and distortions due to bias of social desirability. |

| [101] | The results indicate that pro-environmental behavior is a multidimensional construct. There is a positive correlation between Connectedness to Nature and six domains of pro-environmental behavior: civic actions; policy support; recycling; transportation choices; behavior in the home; and sustainable consumption. | Since the predictive power of connection, the ecological worldview, and environmental concern have never been examined with respect to multiple behavioral domains, The conclusions of this study are provisional and further validation of the results is essential to verify their replicability. It is also critical to examine other psychological antecedents that predict environmental behavior versus those reported in this study, such as norms, earnings, hedonic motivations, and contextual factors (e.g., status, comfort, behavioral opportunities) that previous research has highlighted. This study was carried out in Greece, the results should also be replicated in different socio-cultural contexts. The study is correlative, so no causal conclusions can be drawn. | Sampling of convenience. The measurement of pro-environmental behavior used was constructed at-hoc by the authors, which increases the risk of potential bias. This study is based on self-reported measures, so social desirability could be a limiting factor that influences responses, as well as potential recall errors. |

| [76] | There was a moderately positive correlation between the children’s place of residence and PEB, as well as the Connectedness to Nature and PEB. | The narrow age range does not allow generalizations. It would be important to replicate this research in other countries to allow generalization. The study is correlative, so no causal conclusions can be drawn. | Convenience sampling. Self-reported measurements, therefore possible errors due to social desirability bias and memory bias. |

| [35] | Connectedness to nature is positively correlated with Pro-Environmental Behaviors. This relationship remained positive and significant even by controlling social desirability. Connectedness to nature explains 10% of the variance in pro-environmental behavior. | The participants are all graduates in psychology. Most of the participants are females. The use of the Environmental Behavior scale of Schultz et al. [82] may be a limitation. The scale consists of only 10 behaviors, six of which are related to the recycling or reuse of articles. This limited number of behaviors may have contributed to the low score as participants may have adopted behaviors not included in the scale. Because the scale measures engagement in past behaviors, participants may not be able to properly remember how often they have engaged in behavior, if at all. The extent of the effects observed is relatively small. While the relationships are significant, little variance in pro-environmental behavior has been explained by Connectedness to Nature (only 10%). The research was conducted in only one country, it would be desirable to replicate it in other countries. The study is correlative, so cause and effect relationships cannot be inferred. | Sampling of convenience. Self-reported responses are therefore potentially affected by distortions due to social desirability bias and mnemonic bias. |

| [34] | The results showed that the explicit Connectedness to Nature was positively correlated with intentional environmental behaviors, while the implicit connectedness was positively correlated with spontaneous environmental behaviors. Therefore, it is the implicit Connectedness to Nature that can really predict pro-environmental behavior in real-life situations. | The age range is rather narrow. The participants are all university students. The study was carried out in China, it would be useful to replicate it in other contexts in order to advance generalizations. As a correlation study, no causal statements can be made. The structure of the plastic bag test to measure spontaneous environmental behavior is binary, not continuous. Therefore, measurement could be simplified, necessitating the development of a more elaborate instrument in future studies. | Convenience sampling. Self-reported data, then possibly suffering from recall errors and bias of social desirability. |

| [97] | The authors found a positive correlation between Connectedness to Nature and two types of pro-environmental behavior: Household PEB and Nature Conservation PEB. | The study is correlative, so no cause-and-effect inferences can be advanced. Authors acknowledge that they know little about the quality of contact with nature in the measures used. The study was conducted in England, so it would be useful to replicate it in other countries so that we can generalize the results. The size of the observed effects is small, indicating that natural factors explain only a limited amount of variance in the results. | The data are self-reported, so it may be affected by biases of social desirability and memory. |

| [118] | Results show that the highest scores on Connectedness to Nature are correlated to higher scores on pro-environmental behavior, life satisfaction, beliefs on environmental behavior, and knowledge of the circular economy. | A limit is the sample size, which has been shown to be a limitation by authors in studies with a similar sample size. The age range is narrow. The lack of control over strange variables, such as household socio-economic data, limits the generalization of results. The study was conducted in Spain, it would be desirable to replicate it in other countries. The study is correlative, so it is not possible to come to conclusions about cause-effect relationships. | Convenience sampling. Measurements are self-reported and, therefore influenced by biases of social desirability and recall. |

| [119] | Connectedness to nature is a strong predictor of pro-environmental behavior, higher levels of Connectedness to Nature are associated with higher levels of pro-environmental behavior. Results show that Connectedness to Nature mediates significantly the relationship between age and PEB, so that, with advancing age, their connection levels increase, which, in turn, leads to an increase in PEB levels. | The study is correlative, so it is not possible to make causal inferences. The questionnaire of this study failed to measure a number of important variables, in particular, the amount of time spent in nature by the participants was not measured, similarly, individual occupations, infrastructure levels in their cities, and levels of industrialization near their homes have not been measured. The research was carried out in Canada, it would be useful to replicate it in other socio-cultural contexts in order to generalize the results. | Pro-environmental behavior was measured using a series of items, taken from different tools, there may have been biases in the choice of items by the authors. The data have been self-reported, so it could be distorted due to social desirability bias and mnemonic bias. |

| [61] | Results show that Connectedness to Nature and pro-environmental behavior are significantly and positively correlated. In addition, pro-environmental behavior and Connectedness to Nature are significant mediators in the relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. | The current work has been conducted only in four cities of Pakistan, future researchers should include more cities from other geographical locations in order to have a better generalization. Pro-environmental behavior could also be explained by other variables that have been neglected in this research. The study is correlative, no causal inferences can be made. | Convenience sampling. Self-reported measurements are therefore potentially affected by social desirability and memory biases. |

| [100] | There is a weak positive correlation between Connectedness to Nature and participatory actions in Indian university students. There is a weak positive correlation between Connectedness to Nature and participatory actions in Indian professionals. There is a weak positive correlation between Connectedness to Nature and leadership actions in Indian professionals. | The study was conducted in India, so to generalize the results the same research should be replicated in other socio-cultural contexts. The research has a correlational nature, therefore it does not allow us to conclude causal explanations. | Convenience sampling. Self-reported responses, therefore possibly affected by memory biases and social desirability. |

| [120] | Connectedness to nature had the strongest direct positive association with PEB. The participation in tree planting had statistically significant indirect relationships with PEB through two routes. The first indirect association was through Connectedness to Nature and the second indirect association was through Connectedness to Nature, the use of nature for psychological restoration, and environmental attitudes. | Individuals who particularly appreciate nature or have more financial resources may be more likely to live in greener areas and participate in plantation projects than those who are not so interested in nature or have less economic resources, the lack of causal assignment creates a threat to internal validity. The study was conducted with residents of Wellington City, a city that, atypically, has an abundance of green space. Future research examining residents in other urban areas with less green space and more limited opportunities to engage with nature would strengthen confidence in our findings. The study, being correlative, does not allow to make cause-effect inference. | The results are based on self-reported data, which creates a threat to validity (i.e., measurements may not access what we intend to measure). Sampling of convenience. |

| [121] | The age of participants is significantly and negatively correlated with both the time spent in nature and the children’s Connectedness to Nature, which means that older students tended to spend less time in nature. Socio-economic conditions were shown to have a significant and negative correlation with Connectedness to Nature. Pro-environmental behaviors were found to be significantly and positively correlated with Connectedness to Nature and the time spent in nature. As expected, there was also a significant and positive correlation between Connectedness to Nature and time in nature. | The narrow age range does not allow generalizing results to adults. The drawing is correlative, so no causal conclusions can be drawn. The study was carried out in Australia, it should be replicated in other countries to make possible a generalization. The measure of the amount of time spent in nature simply asked if the children had spent time outdoors when they were at home and at school. It is not a measure of the type of activity, the type of activity in nature is likely to be an important factor to explore. | The data are self-reported, so it may be affected by the bias of social desirability and memory. Convenience sampling. |

| [43] | An individual’s sense of identity as an environmentalist or having a Connectedness to Nature was shown to influence pro-environmental behavior, as the study found a significant positive relationship between these two dimensions. Personal standards have a positive effect on the Pro-Environmental Behaviors used in this study. | The study is limited to the context of Western culture, it would be desirable to validate the results in a different cultural context. The study has a correlational nature, so no causal conclusions can be drawn. | The measures used in this study are based on an individual’s response rather than measuring or witnessing actual behavior, as such, there is potential for respondents to provide socially desirable responses. The answers may also be affected by mnemonic bias. Non-probability sampling (convenience sampling) was used. |