A Comparison of Energy Transition Governance in Germany, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Transition Theory

2.1. Transition Theory as the Study of Historical Transitions

- Transitions are co-evolutionary processes that require changes at the micro-level of “niches” (i.e., protected spaces where new technologies and/or practices are not exposed to the full selective pressures operating in the incumbent regime), at the meso-level of “regimes” (i.e., a dominant set of stable but continuously evolving artefacts, actors and institutions), and at the macro-level of the “landscape” (i.e., the set of processes which operate beyond the direct influence of actors in a given regime);

- Transitions are multi-actor processes, involving a large variety of social groups and cutting across established functional specializations and jurisdictional boundaries;

- Transitions involve moving away from established ways of doing things (in terms of principles, business models, end-user practices, etc.), and this inevitably provokes resistance from groups that fear that their interests will be harmed;

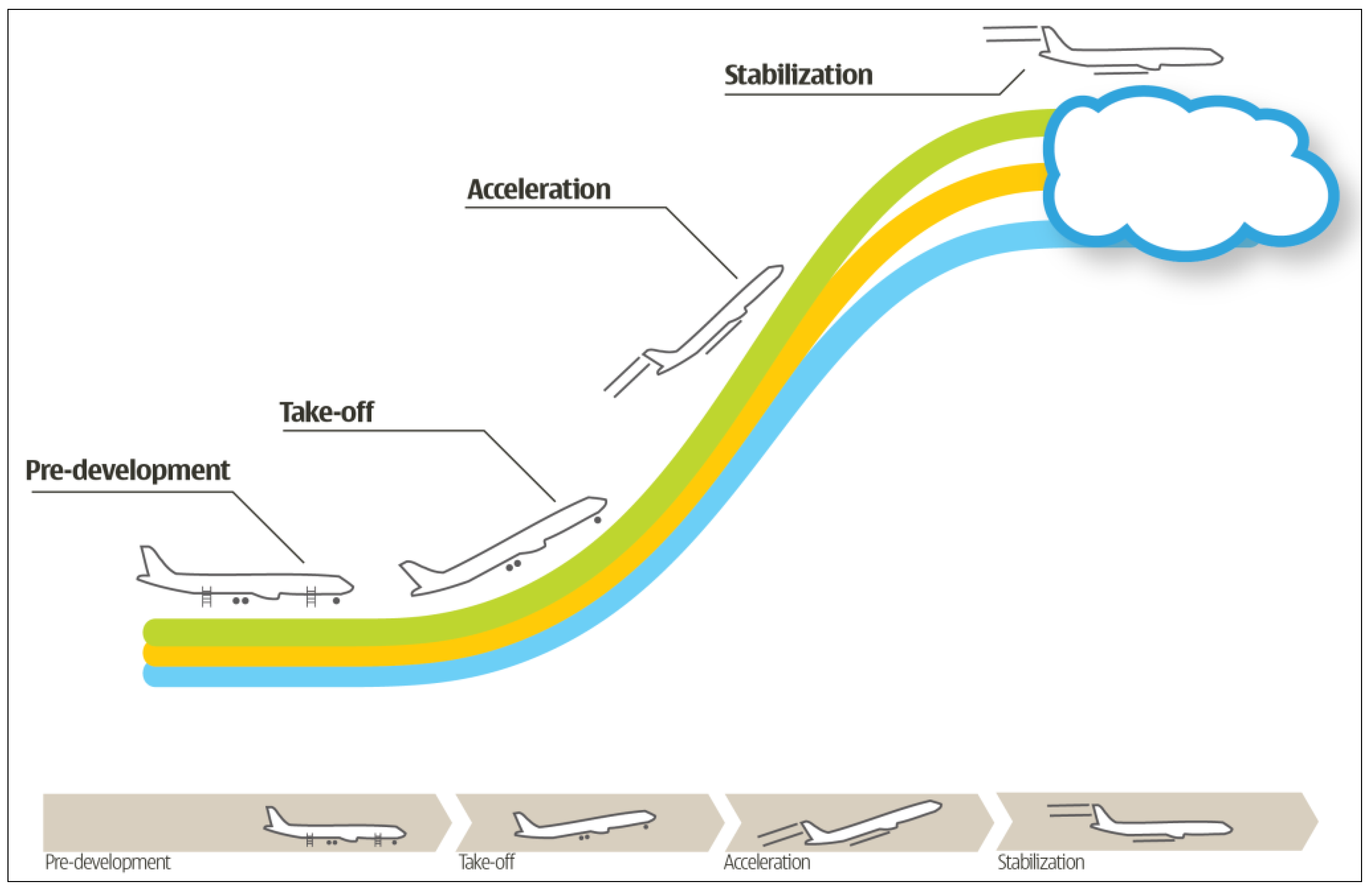

- Pre-development: During the pre-development phase the system status quo remains, but small-scale initiatives arise in which completely new working and thinking paradigms are employed. Early experiments fitting in innovative system structures are established. There is a kind of “nervousness” within the system caused by external (landscape) pressure or tangible consequences of unsustainable practices (“symptoms”). The appropriate way for finding solutions for the complex problem settings is being explored.

- Take-off: The take-off is the phase during which the regime in place starts to absorb the transition impulses and shows a visible—be it cautious—start of a change process. It is the phase during which a number of reactions to the unsustainable situation get higher visibility, are mutually connected and reinforce each other.

- Acceleration: In the acceleration phase structural changes occur and are translated into mainstream practice of many actors; caused by an accumulation of mutually reinforcing socio-cultural, institutional, technological, economical, etc., moves. The new ways of working, thinking, and learning get “anchored” or “embedded”.

- Stabilization: During a stabilization phase, the speed of change decreases, a new system in a dynamic equilibrium is established (in which new niches develop, marking a new cycle, and so on).

2.2. Transition Management as the Attempt to Influence Energy Transitions towards Sustainable Solutions

- The strategic level is concerned with all activities and developments that deal primarily with the “culture” of a societal (sub-)system as a whole: debates on ethics, long-term vision development, collective goal and norm setting, long-term foresight, etc. At this level, transition management aims for the integration (and, hence, institutionalization) of long-term governance activities in the realm of “ordinary” policy making.

- The tactical level is concerned with rooting the visions developed in the transition arenas in the strategies of various networks, organizations and institutions. In this process, visions are further translated into so-called “transition paths”—i.e., (technical, regulatory, cultural) routes to a transition image via intermediate objectives, possibly formulated in a quantitative way (the so-called “transition agenda”).

- At the operational level, transition management is concerned with translating visions and transition paths into “transition experiments”—i.e., “iconic” projects with a high level of risks (hence, the need for a protected setting or “niche”) that can make a potentially large innovative contribution to furthering the transition agenda.

- Finally, the reflexive level is concerned with monitoring and evaluating the transition process itself, as well as the functioning of the specific transition management “tools” (arenas, coalitions, experiments).

- Connecting (a) long-term vision(s) with short-term action: long-term desirable visions can only inspire significant change to start up when the future narratives/images find ways of connecting with contemporary illustrative actions/experiments. Measurable targets and objectives also have an important role to play in ensuring the connection between short-term actions and long-term guiding visions. However, it is notoriously difficult to unequivocally measure progress on the multiple (and often incommensurable) dimensions of sustainable development ([19]; see [20] for a discussion on sustainability impact assessment of energy systems). How do government initiatives connect long-term guiding visions for the energy transition with concrete short-term action, and how is progress measured in achieving the long-term visions?

- Innovation beyond (technological) innovation: Genuine system innovation will be the word of order if we are to move to a low-carbon society. Traditionally, the innovation agenda is often related to technological progress in support of the creation of new jobs and markets, the growth of competitive businesses, and general prosperity. Transition management however stresses that technological, as well as social innovations (in business practices, financing mechanisms, consumption practices, community activism, and so on) will be needed, allowing individuals, families, and communities to flourish without imposing undue stress on the global environment. How do states promote governance practices, which accelerate socio-technical innovation, encourage experimentation, orient inventiveness, and speed up the processes of diffusing beneficial societal advances from a sustainability perspective?

- Integration: Low-carbon development requires the simultaneous pursuit of multiple goals and the management of issues that cut across established administrative responsibilities. Transition governance stresses that economic, social, and environmental concerns should not just be balanced and traded off against each other; instead, a creative search for win-win situations offers chances of better integration of low-carbon concerns over administrations. However, such integration is notoriously difficult to achieve, as existing administrative structures and procedures tend to encourage a partial vision of problems [21]. Moreover, short-term political and policy imperatives frequently preclude longer-term and integrated thinking. How can states promote or institute transition governance approaches, which encourage such integration?

- Societal involvement and engagement: Low-carbon development cannot be achieved by governments alone. To achieve such far-reaching changes requires strong and consistent public support and understanding, self-directed change in many domains of society, and collaboration among diverse social actors. Multi-stakeholder processes have been a distinctive feature of governance for sustainable development ever since the publication of the Brundtland report [15]. Information and understanding from many actors is required to make sense of issues, plot appropriate transition trajectories, and implement sustainable solutions. How can societal engagement be encouraged and structured? And, how can the quality of debate in the public sphere be raised regarding complex issues related to sustainability?

- Learning/reflexivity: Learning is a constant feature of navigating the inherently uncertain transition to a low-carbon future. Individuals and groups continuously draw lessons from their experiences, but there is no guarantee these lessons will advance particular social goals. They may also be about political strategies and blocking change [22]. Reflexivity implies more than the usual “incremental adjustment” associated with the traditional policy cycle, as it involves deeper reflection on the goals of action and wider societal participation [1]. How can states promote fruitful social learning and reflexive low-carbon transition governance frameworks?

3. The German Energy Transition

3.1. Case Description

3.1.1. Pre-Development

3.1.2. Take off

3.2. Overall Assessment with Regard to the Implementation of Transition Management Core Ideas

4. The Dutch Energy Transition

4.1. Case Description

4.1.1. Pre-Development

4.1.2. Take off (as Part of Innovation Policy) and Subsequent Decline

4.2. Overall Assessment with Regard to the Implementation of Transition Management Core Ideas

5. The UK Energy Transition

5.1. Case Description

5.1.1. Pre-Development

5.1.2. Take off

- Providing a statutory foundation for the official UK greenhouse gas emissions targets of at least a 34% reduction by 2020, and an 80% reduction by 2050 (both based on 1990 levels), through action in the UK and abroad. The 80% target is a unilaterally binding target set by the UK in the absence of a binding agreement at the EU or international level. The UK government has the power to amend this target, but only if specific circumstances present themselves (a significant development in the science of climate change or in European law or policy);

- Establishing a system of five-year carbon budgets that set annual levels for permissible emissions. Three budgets spanning a 15-year time horizon will be active at any given time, presenting a medium-term perspective for the evolution of carbon emissions over the economy as a whole. The first budgets relate to the years 2008–2012, 2013–2017, and 2018–2022. A fourth budget relating to the years 2023–2027 was recently introduced (June 2011), setting out a target of a 50% reduction of GHG emissions on average (compared to 1990 levels);

- Establishing a Committee on Climate Change (CCC), as an independent expert advisory body that can make recommendations to government concerning the pathway to the 2050 target. It is composed of five to eight high-ranking scientists + a chair and chief executive, all of whom are influential in business and politics. The CCC reports annually to Parliament, and the government is required to formally reply to its reports. The merit of having an independent watchdog lies in forcing government to publically justify its own actions on a regular basis. This in turn contributes to a credible government commitment to long-term policies, which is a necessary precondition for creating a stable investment climate [52]. The CCC therefore has a central role in the UK transition to a low-carbon economy [53]. However, although the CCC does give detailed advice on specific policies available in for moving different sectors of the economy along a low-carbon transition path, it is not within their remit to suggest the optimal policy mix (this is left to the government’s discretion).

5.2. Overall Assessment with Regard to the Implementation of Transition Management Core Ideas

6. Tentative Lessons Learnt from the Three Country Cases

| Germany | The Netherlands | United Kingdom | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main transition governance innovation | Promotion of development and diffusion of RES in electricity generation through feed-in tariffs | Adoption of transition governance as the reference framework for innovation policy | Adoption of a long-term legislative commitment to a low-carbon energy future |

| Pre-development | Early action for combatting climate change combined with protracted nuclear controversy opened up a space for the promotion of RES as a real alternative | Clever “boundary work” by transition researchers led to the adoption of the transition framework in the national environmental planning process | Early engagement in the climate change issue due to strong public and political campaign effort backed by leading scientists (e.g., Stern) |

| Take-off | The EEG (adopted in 2000) combined with irreversible nuclear phase out (due to strong public support) has established a long-term commitment to RES as the main power source of the future | Transition governance was adopted as the frame of reference for innovation policy; hundreds of transition experiments have been funded and extensive learning has occurred | Long-term commitment to a low-carbon economy embedded in a legal framework with clear targets and responsibilities |

| Success factors | A process of cumulative causation has been put into motion by the adoption of the EEG with institutional change, market formation, entry of new firms and the strengthening and formation of advocacy coalitions as main constituent parts | Promoting the acceptance of the “transition governance” discourse in “traditional” policy circles based on its complementarity to other goals such as ecological modernization, energy market liberalization and stimulating the knowledge economy | Strong institutional base for supporting the transition to a low carbon economy, including mandatory long-term targets, system of carbon budgets, independent advice and scrutiny |

| Pitfalls | Managing the costs of RES deployment, especially for households | Colonization of transition governance by vested interests, implying limited impact on mainstream energy policy | Robustness of the climate policy framework when speed of decarbonization lags behind official government targets |

- In promoting and stimulating local or regional initiatives (drawing on resources of regional/local identification);

- In stimulating wider involvement in the actual practice of conducting transition experiments;

- In stimulating the actual practice of building coalitions around technological options for transition paths (e.g., the German RES policy design);

- In allowing stakeholder input into the formulation of concrete measures for initiating a transition;

- In setting up multi-stakeholder processes for developing scenarios, pathways, and visions.

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Voβ, J.-P.; Bauknecht, D.; Kemp, R. (Eds.) Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006.

- Doern, B.; Gattinger, M. Power Switch: Energy Regulatory Governance in the Twenty-First Century; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). A Roadmap for Moving to a Competitive Low Carbon Economy in 2050; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Unruh, G. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, J.C.J.M.; Truffer, B.; Kallis, G. Environmental innovation and societal transitions: Introduction and overview. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition management for sustainable development: A prescriptive, complexity-based governance framework. Governance 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions towards Sustainable Development; Routledge Studies in Sustainability Transitions; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Voβ, J.-P.; Bornemann, B. The politics of reflexive governance: Challenges for designing adaptive management and transition management. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16. Article 9. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss2/art9/main.html (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Avelino, F.; Rotmans, J. Power in transition: An interdisciplinary framework to study power in relation to structural change. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2009, 12, 543–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Environmental political economy, technological transitions and the state. New Pol. Econ. 2005, 10, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Engaging with the politics of sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notenboom, J.; Boot, P.; Koelemeijer, R.; Ros, J. Climate and Energy Roadmaps towards 2050 in north-western Europe. Available online: http://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/cms/publicaties/PBL_2012_Climate-and-Energy-Roadmaps_500269001_0.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Knopf, B.; Bakken, B.; Carrara, S.; Kanudia, A.; Keppo, I.; Koljonen, T.; Mima, S.; Schmid, E.; van Vuuren, D. Transforming the European energy system: Member states’ prospects within the EU framework. Clim. Change Econ. 2013, 4, pp. 1–26. Available online: http://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/S2010007813400058 (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, B.; Krishna, K. The coming sustainable energy transition: History, strategies and outlook. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7422–7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquet, R. The slow search for solutions: Lessons from historical energy transitions by sector and service. Energy Policy 2011, 38, 6586–6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management: New Mode of Governance for Sustainable Development; International Books: Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Sustainability Indicators—Measuring the Immeasurable; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hugé, J.; Waas, T.; Eggermont, G.; Verbruggen, A. Impact assessment for a sustainable energy future—reflections and practical experiences. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 6243–6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A. At the Edge; University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scrase, I.; Smith, A. The (non-)politics of managing low carbon socio-technical transitions. Environ. Polit. 2009, 18, 707–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enquete Commission of the German Bundestag. Protecting the Earth’s Atmosphere: An International Challenge. Deutscher Bundestag Referat Öffentlichkeitsarbeit: Berlin, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Weidner, H.; Mez, L. German climate change policy—a success story with some flaws. J. Environ. Dev. 2008, 17, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMWi. Zahlen und Fakten–Energiedaten–Nationale und Internationale Entwicklung. Available online: http://www.bmwi.de/DE/Themen/Energie/Energiedaten-und-analysen/Energiedaten/gesamtausgabe,did=476134.html (accessed on 6 January 2014). (In German)

- Jacobsson, S.; Lauber, V. The politics and policy of energy system transformation—explaining the German diffusion of renewable energy technology. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesetz für den Vorrang Erneuerbarer Energien. Available online: http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bundesrecht/eeg/gesamt.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2014). (In German)

- Verbruggen, A.; Lauber, V. Basic concepts for designing renewable electricity support aiming at a full-scale transition by 2050. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 5732–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi); Federal Ministry for the Environment; Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). Energy Concept for an Environmentally Sound, Reliable and Affordable Energy Supply; BMWi/BMU: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ethikkommission. Germany’s Energy Transition—a Collective Project for the Future; the Ethics Commission for a Safe Energy Supply: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vivid Economics. G20 low carbon competitiveness. Report prepared for the Climate Institute and E3G. Available online: http://www.e3g.org/docs/G20_Low_Carbon_Competitiveness_Report.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Bosman, R. Germany’s “Energiewende”: Redefining the Rules of the Energy Game; Clingendael International Energy Programme: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 100% Erneuerbare-Energie-Regionen-Projekt. Available online: http://www.100-ee.de (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). Entwurf Erfahrungsbericht 2011 zum Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz. Available online: http://www.erneuerbare-energien.de/fileadmin/ee-import/files/pdfs/allgemein/application/pdf/eeg_erfahrungsbericht_2011_entwurf.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Kemp, R. The Dutch energy transition approach. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2010, 7, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F.; Smith, A. Restructuring energy systems for sustainability? Energy transition policy in the Netherlands. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4093–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Kern, F. The transitions storyline in Dutch environmental policy. Environ. Polit. 2009, 18, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Rotmans, J. Transitioning policy: Co-production of a new strategic framework for energy innovation in the Netherlands. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerie voor Economische Zaken. Nu voor later: Energie Rapport 2005; Ministerie voor Economische Zaken: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2005. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- According to Kemp and Rotmans ([38], pp. 316–319], top officials from VROM and EZ made it very clear at this stage that the involvement of scientists in the policy implementation of transition management was no longer wanted. This reflects a clear desire to make selective use of transition concepts and to be in command of the whole process. For the EZ officials, a primary condition was also that the Dutch energy business community would be very visibly involved in the process.

- Hendriks, C. The democratic soup: Mixed meanings of political representation in governance networks. Governance 2009, 22, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Assessing the Dutch energy transition policy: how does it deal with dilemmas of managing transitions. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 2007, 9, 315–331. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, J.-P. Clogs in the works. Available online: http://www.greenchallenge.info/MediaDetails/ClogsInTheWorks.htm (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Hekkert, M.; Suurs, R.; Negro, S.; Kuhlmann, S.; Smits, R. Functions of innovation systems: A new approach for analysing technological change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2007, 74, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International success is evident from the establishment of a “Sustainability Transitions Research Network”, as well as the international journal “Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions” which is specifically dedicated to transition research.

- Kern, F.; Howlett, M. Implementing transition management as policy reforms: A case study of the Dutch energy sector. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M. De energieke samenleving. Op zoek naar een sturingsfilosofie voor een schone economie; Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving: Den Haag, the Netherlands, 2011. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- This focus does not imply that we believe this Act to be the sole “necessary and sufficient condition” for driving the transition to a low-carbon economy in the UK. Other (bottom-up) initiatives acting outside the scope of formal government support are certainly also worth mentioning. Especially worth mentioning here is the Transition Town Movement (which originated in the UK), a community-led process that helps a town/village/city/neighbourhood to become stronger, happier and more resilient. These communities have started up projects in areas of food, transport, energy, education, housing, waste, arts, etc., as small-scale local responses to the global challenges of climate change, economic hardship and shrinking supplies of cheap energy.

- ClientEarth. The UK Climate Change Act 2008—Lessons for Other National Climate Laws; ClientEarth: London, UK, 2009. Available online: http://www.clientearth.org/reports/climate-and-energy-lessons-from-the-climate-change-act.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Foxon, T. Governing a Low Carbon Energy Transition: Lessons from UK and Dutch Approaches. In Handbook of Sustainable Energy; Galarraga, I., González-Eguino, M., Markandya, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2011; pp. 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, S.; Flachsland, C.; Marschinski, R. Credible commitment in carbon policy. Clim. Policy 2012, 12, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, P.; Swales, J.; Winning, M. A review of the role and remit of the committee on climate change. Energy Policy 2012, 41, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R. The British Climate Change Act: A critical evaluation and proposed alternative approach. Environ. Res. Lett. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C. Preferable In tervention—the Pursuit of Nuclear Power. In The Political Economy of Sustainable Energy; Mitchell, C., Ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 96–120. [Google Scholar]

- UK DECC. Energy calculator. Available online: http://www.decc.gov.uk/en/content/cms/tackling/2050/calculator_on/calculator_on.aspx (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- There is however a rather small DECC programme aimed a empowering local communities to reduce their energy consumption and make deep cuts in GHG emissions (for more information, see [70]).

- Verbruggen, A. Renewable and nuclear power: A common future? Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4036–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxon, T.; Hammond, G.; Pearson, P. Developing transition pathways for a low carbon electricity system in the UK. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2010, 77, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laes, E.; Verbruggen, A. Decision Support for National Sustainable Energy Strategies in an Integrated Assessment Framework. Paths to Sustainable Energy; Ng, A., Ed.; Intech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 93–116. Available online: http://www.intechopen.com/books/howtoreference/paths-to-sustainable-energy/decision-support-for-national-sustainable-energy-strategies-in-an-integrated-assessment-framework (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Covenant of Mayors. Available online: http://www.covenantofmayors.eu/index_en.html (accessed on 6 January 2014).

- Ieromonachou, P.; Potter, S.; Enoch, M. Adapting strategic niche management for evaluating radical transport policies—the case of the Durham road access charging scheme. Int. J. Transport Manag. 2004, 2, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, D.; van Vliet, J.; van Vliet, B. Niche management and its contribution to regime change: The case of innovation in sanitation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2007, 19, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. A model for an analytic-deliberative process in risk management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 3049–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, E.; Knopf, B. Ambitious Mitigation Scenarios for Germany: A participatory approach. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, T.; Haxeltine, A.; Longhurst, N.; Seyfang, G. Sustainability Transitions from the Bottom-up: Civil Society, the Multi-Level Perspective and Practice Theory; CSERGE Working Paper 2011–01; The Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment (CSERGE): Norwich, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. Civil Society in Sustainable Energy Transitions. In Governing the Energy Transition: Reality, Illusion or Necessity? Verbong, G., Loorbach, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK.

- Chandler, H. Harnessing Variable Renewables; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UK DECC. Low Carbon Communities Challenge. Available online: http://www.decc.gov.uk/en/content/cms/tackling/saving_energy/community/lc_communities/lc_communities.aspx (accessed on 6 January 2014).

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Laes, E.; Gorissen, L.; Nevens, F. A Comparison of Energy Transition Governance in Germany, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1129-1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6031129

Laes E, Gorissen L, Nevens F. A Comparison of Energy Transition Governance in Germany, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Sustainability. 2014; 6(3):1129-1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6031129

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaes, Erik, Leen Gorissen, and Frank Nevens. 2014. "A Comparison of Energy Transition Governance in Germany, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom" Sustainability 6, no. 3: 1129-1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6031129

APA StyleLaes, E., Gorissen, L., & Nevens, F. (2014). A Comparison of Energy Transition Governance in Germany, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Sustainability, 6(3), 1129-1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6031129