Laying the Foundation for Transdisciplinary Faculty Collaborations: Actions for a Sustainable Future

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“A critical and self-reflective research approach that relates societal with scientific problems; it produces new knowledge by integrating different scientific and extra-scientific insights; its aim is to contribute to both societal and scientific progress”.[13] (p. 8)

“Learning that transforms problematic frames of reference—sets of fixed assumptions and expectations (habits of mind, meaning perspectives, mindsets)—to make them more inclusive, discriminating, open, reflective, and emotionally able to change.”.[22] (p. 58)

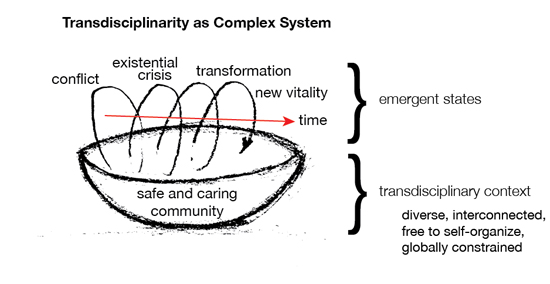

2. Background: Using Complexity Science Metaphors for Transdisciplinarity

2.1. Metaphors and Their Unintended Consequences

2.2. Introduction to Dynamic Complex Systems

“At the core of [emergence] was the thought that as systems acquire increasingly higher degrees of organizational complexity they begin to exhibit novel properties that in some sense transcend the properties of their constituent parts, and behave in ways that cannot be predicted on the basis of the laws governing simpler systems”.[41] (p. 3)

3. Experimental Context

3.1. History and Overview

| Case | Duration | Participants | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | December 2007–September 2011 Initiation, design | Local citizens, business owners, government representatives, non-profit organizations, faculty, staff, administrators, students (35 people) | Open invitation to create a community who would co-create sustainable alternatives to current activities |

| 1 | September 2011–August 2012 Implementation 1 | Same as Case 0 with a core group of 10 partners from Case 0 (58 people) | First cohort of freshmen (43) taking linked courses from SUSTAIN faculty partners and participating in community projects |

| 2 | September 2012–August 2013 Implementation 2 | Same as Case 1 with two changes in the core partner Case 1 core partners (60 people) | Second cohort of freshmen (45) taking linked courses from SUSTAIN faculty partners and participating in community projects |

| 3 | September 2013–present Implementation 3 | Same as Case 2 with two changes in the core partner group (85 people) | Third cohort of freshmen (63) taking linked courses from SUSTAIN faculty partners and participating in community projects |

| Intent | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-design activities | Title | Description | Key questions |

| Phase A: Established a collaborative community and shared aspirations | Create community around shared aspirations | Invited people to explore the possibility of learning together to create sustainable alternatives to industrial era designs | Given your busy lives, why are you here at this meeting? What is the larger thing that you are committed to in the world? Who is missing? |

| Explicitly share aspirational values of our community | Co-created a small set of shared principles that we could remember at all times and use as a standard in times of conflict | Who do we want to be together? | |

| Phase B: Uncovered a ground of wholeness and abundance from which to co-design | Co-design from an internal state that was consistent with our aspirations | In response to assertions of what was necessary, recursively explored what the need would provide until we arrived at some quality of intrinsic value (such as “peace”) | What would it make possible if you had what you think is needed? What is stopping you from embody this quality of intrinsic value now, in this moment? |

| Phase C: Navigated implementation in alignment with shared principles | Ensure congruence of project with shared aspirations | Continuously adjust to align project implementation with shared aspirations | Are our actions consistent with our principles and aspirations? |

3.3. Phase B: Uncovering a Ground of Wholeness and Abundance from Which to Co-Design

4. Methodology

5. Results

| A safe and caring community; |

| Conflict, both internal to individuals and open conflict between individuals; |

| Existential crises; |

| Personal growth and transformation; |

| Renewed vitality |

5.1. A Safe and Caring Community

“SUSTAIN has taught me that there are people (at this university!) who do respect me and do value me. The group of instructors who teach in SUSTAIN are kind and different and intelligent and kind and wonderful and thought-provoking and kind (did I already say that? Oh well, it deserves to be said again). They have a way of challenging me without making me feel inferior.”.(C.B.)

“I see that I am not the only one suffering here….I see how valuable my work is here. I see how little valued it is and also how that matters very little.”(C.B.)

“I see how much my soul is hungry to write and write and how tired it is of sending students off to try to do it. I see what a kind, real group of humans you all are and how privileged it's been for me to work alongside you... But I do want to say thank you. Thanks for loving me in a way that's helped me to be courageous.”(G.H.)

“Here at SUSTAIN headquarters [50], I am surrounded by some of the kindest people I have ever met, intelligence levels that truly are off the charts and a sense of community I never thought possible on the Cal Poly campus.”(C.B.)

“This crisis [a SUSTAIN faculty member having a brain hemorrhage] revealed to us how we are with each other. We are a community who care for each other, not only the faculty, but the students too.”(L.S.)

“This group of people, faculty, community members, staff and students has shown me what a life of caring really means. I experience with these [SUSTAIN] people inspiration, acceptance, challenge and hope.”(L.S.)

5.2. Conflict

“Physics, all full of forces and gravity and friction, is pushing everything out.”(L.S.)

“[The physics teacher] and I recreated a conflict that we allegedly ‘had’ during the day. It turned out that it was a live conflict, rather than one that we were ‘over’.”(L.V.)

5.3. Existential Crisis

“I am in a personal collapse of ‘ego’, of all that I once believed to be true about myself and my life—my professional and my personal life. Over the last year, my friendship with Roger has catalyzed in me a far deeper ability to ‘see’. I can now witness my own thought patterns and habits of mind. I find myself able to interrupt my enactment of what I experience as ‘suffering’. I feel so profoundly grateful for this, yet liberation is strangely uncomfortable because I have lost the story of who I am (or who I thought I was).”(L.V.)

“If I release the role of Progress Manager/Learning Warden/Content Expediter, then what role could I embrace in its place?”(G.H.)

5.4. Renewed Vitality

“I feel pedagogically alive after this year. I feel full of hope and love. Thank you SUSTAIN.”(C.B.)

“What happened is that the students left hungry for more content. Most of them asked if they could attend the course again this quarter, without receiving credit, just because they wanted to learn more. What if at the end of every course the students want more? What if they didn’ t see the class as a box to be checked, but as something interesting? What if we stopped cramming stuff down their throat in order for them to regurgitate the content on an exam and gave them tasty morsels that they will seek out in the future? This is my yardstick now: When the course is over, are the students hungry for more?”(L.S.)

6. Discussion

6.1. Failure of Normal Cause-Effect Relationships to Account for Patterns

| Type of Science | Natural | Cultural | Critical |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frame | Positivist | Hermeneutic constructivist | Emancipatory |

| Cognitive Interest | Technical: predicable outcome of practical skills for employment | Practical/meaning; Intellectual development and practical skills for understanding | Liberation*/enlightenment to enact conscious choices |

| Social domain | Work | Language/culture | Power/authority |

| Purpose | Prediction/control | Understanding/consensus | Enlightenment |

| Assumed system dynamic | Simple, controllable, predictable | Complicated | Complex, unpredictable |

| Status of participants | Student = fungible object; Faculty = authorized subject Community partner = resource to be used in transactions for desired outcomes | Student = individual; Faculty = guide Community partner = Contractual partner | Student, faculty and Community partners = Co-learners |

| Motivational assumption | External reward/punishment | Intrinsic values | Freedom as human vocation. Liberty and equity |

| Learning emphasis | Reproducing authorized content | Applying authorized content, developing individual voice | Mastery, learning capacity, ability to manage one’s attention |

| Structure | Prescriptive order (faculty-centered; lecture) | Imposed organization, optionality (mixed: active learning modalities) | Self-organization, networked, high level of autonomy (self-directed learning modalities) |

| Institutional metrics | Efficiency, cost, throughput | Student evaluations | Citizenship |

| System metaphor | Machine, factory | Organization | Living organism |

| Means | Application of control and force by authority figure (hierarchical) | Negotiated agreement between student and faculty | Dynamic, emergent, co-operation and collaboration |

| Learning process | Prescribed order (recipe) | Prescribed process (formulae) | Experimentation: situated practice with reference to formulae |

| Expertise | Field expertise required, but no expertise as a teacher is required | Pedagogical expertise across a variety of disciplines | Expertise does not necessarily ensure success |

| Disciplinary Status | Separate, bounded, fragmented | Interdisciplinary | Transdisciplinary |

| Type of learning that is assessed | Reproducing known results, information or applying such | Understanding, adaptive capability to apply concepts | Critical inquiry, transformational, situated learning by doing |

| System Boundaries | Closed | Open, bounded | Open, mutable: based on shared qualities and properties |

| Outcomes | Prescribed, fully described | Partially described | Not predictable, emergent |

| Collaborative dynamic | Possible only at the level of content | Collaboration at the level of pedagogy including content and process | Requires collaboration at the levels of content, process and context |

| Scope | Intentionally constrained to teachers’ areas of expertise; hierarchically determined; taken as determined by discipline | Partially constrained by class design with open boundaries to students’ areas of interest | Directed toward shared course aims, but limited only by one’s attention; Challenges boundaries of understanding for all participants |

6.2. Learning as Emergence: A Model of Transformative Change

| Occurrence in our transdisciplinary system | ||

|---|---|---|

| Properties | Complex system | The context of the transdisciplinary research, to include participants and all other situational factors |

| Open boundaries | Participants were participating in SUSTAIN courses as well as other experiences, rather than only SUSTAIN courses. | |

| Dynamic | Participants freely making self-regulated choices about their actions with the result of an ever-changing set of states within the human system | |

| Interconnectedness | Individuals interacted across boundaries at all different scales: peers, courses, projects, organizational and institutional boundaries | |

| Recursive | Individuals’ actions were immediately felt by the community, which causes recursive responses. | |

| Behavior | Non-linear | Learning measured by traditional measures was non-linear with large developmental increases demonstrated at the end of the quarter |

| Emergent (self-organizing) | Adaptive learning and conflict as weak emergence; Existential crisis, transformation and revitalization as strong emergence . | |

6.3. Systemic Conditions Supporting the Emergence of the Transformative Learning Opportunity

| System Condition | How this was met in our SUSTAIN learning system |

|---|---|

| Requisite diversity | Student, faculty and community partner of interests and disciplinary homes that spanned critical, social and natural sciences. Representative colleges: architecture, agriculture, liberal arts, science and math, engineering, business. |

| High degree of interconnectivity | Daily and weekly interactions supported through course meeting structure and team projects; instantaneous communication through social media. |

| Freedom to self-organize | Communication and self-organization facilitated through transparency of information and use of social networking tools. |

| Global constraint | Teams formed on the basis of autonomously choosing projects that were intrinsically motivating while ensuring that all partners were served with a team of a minimum size of three. |

6.3.1. A Requisite Variety within the System (Diversity)

6.3.2. A Global Constraint within the System (Project Group Formation)

6.3.3. A High Degree of Interconnectivity amongst the Parts of the System (Transparency and Community)

6.3.4. Freedom of Agents within the System to Reconfigure (Self-Organization)

6.4. Conditions for the Success of Faculty Members in the Transdisciplinary Research System

| Qualities | Description |

|---|---|

| Authenticity | Living in an emotionally appropriate, significant, purposive and responsible way that is congruent with espoused values |

| Presence | A quality of being that is emotionally open and attentive to what arises in the present moment |

| Satiation with the human need of respect | Sense of having their human need for respect generally satisfied |

| Vulnerability to one’s own state as a learner | Willingness to acknowledge one’s lack of understanding, limits of understanding and the possibility of learning from anyone. |

| Skillful means | Ability to manage one’s attention; bodily sense one’s affective state; suspend one’s hostile assumptions about “other”; enact a model of unity in the presence of conflict; consciously hold a paradox |

6.5. Negotiating the Existential Crisis: The Necessity of the “Strange Attractor”

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Appendix: SUSTAIN SLO Learning Initiative Details

(1) Students

| Case 1 (2012) | Case 2 (2013) | Case 3(2014) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students | 42 | 43 | 63 |

| Number of freshman at the university (fall) | 4316 | 3701 | 4871 |

| Number of different majors | 29

(49% STEM*) | 25

(28% STEM*) | 30

(32% STEM*) |

| Percent female | 57% | 59% | 65% |

| Average SUSTAIN course load as % of total course load | 75% | 50% | 50% |

(2) Faculty

| Case 1 (2012) | Case 2 (2013) | Case 3 (2014) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of faculty collaborators | 9 | 12 | 9 |

| (7 new) | (2 new) | ||

| Number of lecturers | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Courses offered by collaborating faculty | Liberal Arts | Liberal Arts | Liberal Arts |

| History of Social Movements; | Music of the 60’s; | Music Appreciation; | |

| Economics | Ethnic Studies | Food and Culture | |

| Science/Engineering | Science/Engineering | Science/Engineering | |

| Soil Science; | Soil Science; | Soil Science; | |

| Plant Diversity and Ecology; | Plant Diversity and Ecology; | Plant Diversity and Ecology; | |

| Project Management; | Project Management; | Project Management; | |

| Physics (calculus) I and II; | Physics (calculus) I and II; | Physics (calculus) I and II; | |

| Physics (algebra) I and II; | Physics (algebra) I and II; | Physics (algebra) I and II; | |

| Introductory Physics; | Introductory Physics; | Introductory Physics; | |

| Chemistry | Sustainability | Sustainability | |

| Communications | Communications | Communications | |

| Speech; | Speech; | Speech; | |

| Freshman Comp; | Freshman Comp; | Freshman Comp; | |

| Critical Thinking and Writing | Critical Thinking and Writing | Critical Thinking and Writing | |

| Number of sections | 18 | 19 | 17 |

| Number of SUSTAIN only sections | 16 | 3 | 6 |

(3) Community Partners

| Case 1 (2012) | Case 2 (2013) | Case 3 (2014) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participating community partners | AIDS Support Network; SLO Creek Farms; United Way * ;Food Bank; Oak Creek Commons *; Western Wildlife; Generations Waking Up; Master Gardeners *; Glean SLO *; Independent Living Resource Center * | Along Comes Hope *; United Way *; Oak Creek Commons *; Glean SLO *; Real Food Collaborative; Cal Poly Divest; WikiSLO; Laureate School *; One Cool Earth; Asset Development *; SLO Seed Exchange; Puppet Theatre | Along Comes Hope *; Laureate School *; Asset Development *; Creative Mediation; Independent Living Resource Center*; SLO MakerSpace; The Lavra; The Ranch; United Way *; Sustainable Living Research Ordinance |

| Number of projects | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Team size | 3–7 | 2–7 | 3–10 |

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Makower, J.; Pike, C. Strategies for the Green Economy: Opportunities and Challenges in the New World of Business; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, U. Green Economy the Next Oxymoron? No Lessons Learned from Failures of Implementing Sustainable Development. GAIA-Ecolog. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2012, 21, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolescu, B. Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity; Voss, K-C., Ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Després, C.; Brais, N.; Avellan, S. Collaborative planning for retrofitting suburbs: Transdisciplinarity and intersubjectivity in action. Futures 2004, 36, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, T. Prospects for Transdisciplinarity. Futures 2004, 36, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C. Transdisciplinary collaboration in environmental research. Futures 2005, 37, 1159–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C. From science to policy through transdisciplinary research. Environ. Sci. Policy 2008, 11, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgärtner, S.; Becker, C.; Frank, K. Relating the philosophy and practice of ecological economics: The role of concepts, models, and case studies in inter- and transdisciplinary sustainability research. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 67, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch Hadorn, G.; Bradley, D.; Pohl, C. Implications of transdisciplinarity for sustainability research. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 60, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Being undisciplined: Transgressing and intersections in academia and beyond. Futures 2008, 40, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory. Foundations Development Applications; George Braziller, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, T.; Bergmann, M.; Keil, F. Ecological Economics. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, M. Science’s new social contract with society. Nature 1999, 402, C81–C84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T. Transdisciplinarity in the Practice of Research, Interdisciplines: Virtual Seminar. Inter- Transdisc. Horizons. Available online: http://www.interdisciplines.org/paper.php?paperID=374 (accessed 20 April 2014).

- Carew, A.L.; Wickson, F. The TD Wheel: A heuristic to shape, support and evaluate transdisciplinary research. Futures 2010, 42, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehng, J.-C.J.; Johnson, S.D.; Anderson, R.C. Schooling and Students’ Epistemological Beliefs about Learning. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 18, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, B.K. Dimensionality and disciplinary differences in personal epistemology. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 378–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattuca, L. Learning interdisciplinarity: Sociocultural perspectives on academic work. J. High. Educ. 2002, 73, 711–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.; Deetz, S. Metaphor analysis of social reality in organizations. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 1981, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Learning as Discourse. J. Transform. Educ. 2003, 1, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S.; Burke, P.J. The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.; Vanasupa, L.; Schlemer, L. From Emergency to Emergence: An Educational Imperative for Our Complex, Interconnected and Ever-changing world. Int. J. Eng. Soc. Justice Peace 2014. submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L. Deepening Ecological Relationality Through Critical Onto-Epistemological Inquiry Where Transformative Learning Meets Sustainable Science. J. Transform. Educ. 2013, 11, 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ricca, B. Beyond Teaching Methods: A Complexity Approach. Complicity 2012, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, N. Complexity, complexity reduction, and “methodological borrowing” in educational inquiry. Complicity 2012, 9, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yam, Y. A mathematical theory of strong emergence using multiscale variety. Complexity 2004, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Vanasupa, L.; McCormick, K.E.; Stefanco, C.J.; Herter, R.J.; McDonald, M. Challenges in Transdisciplinary, Integrated Projects: Reflections on the Case of Faculty Members’ Failure to Collaborate. Innov. High. Educ. 2011, 37, 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- McClam, S.; Flores-Scott, E.M. Transdisciplinary teaching and research: What is possible in higher education? Teach. High. Educ. 2012, 17, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T.; Knobloch, T.; Krohn, W.; Pohl, C.; Schramm, E. Methods for Transdisciplinary Research: A Primer for Practice; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gotthelf, A. Aristotle’s conception of final causality. Rev. Metaphys. 1976, 30, 226–254. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J. Is Higher Education Ready for Transformative Learning?: A Question Explored in the Study of Sustainability. J. Transform. Educ. 2005, 3, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mälkki, K. Building on Mezirow’s theory of transformative learning: Theorizing the challenges to reflection. J. Transform. Educ. 2010, 8, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Imre, A. Metaphors in Cognitive Linguistics. Eger J. Engl. Stud. 2010, 10, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Cormac, E.R. A Cognitive Theory of Metaphor; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, M.; Limoges, C.; Nowotny, H.; Schwartzman, S.; Scott, P.; Trow, M. The New Production of Knowledge—The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Keene, C. Development Projects That Didn’t Work; Globalhood, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Making Sense of Emergence. Phil. Stud. 1999, 95, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A detailed description of the multitude of experiences in the change process that are beyond the scope of this paper. These are going to occur in any transdisciplinarity project and it is necessary to have a living, coherent theory of change to work with aspect. We encourage you to contact us if you are interested in design strategies that we used to navigate change process.

- Böhm, D. On Dialogue; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Torbert, W.R. Why educational research has been so uneducational: The case for a new model of social science based on collaborative inquiry. In Human Inquiry; Reason, P., Rowan, J., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny, H.; Scott, P.; Gibbons, M. Re-Thinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schon, D.A. Participatory action research and action science compared. Am. Behav. Sci. 1989, 32, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Bonner, A.; Francis, K. The development of Constructivist Grounded Theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2006, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, J. Using grounded theory and action research to raise attainment in, and enjoyment of, reading. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2009, 25, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teram, E.; Schachter, C.L.; Stalker, C.A. The Case for integrating grounded Theory and Participatory Action Research: Empowering Clients to Inform Professional Practice. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Headquarters”: this is humor. We did not actually have a headquarters. But there is irony in the metaphor of a military center, since we were often careful with our metaphors.

- Mingers, J. Recent Developments in Critical Management Science. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1992, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hénon, M. A two-dimensional mapping with a strange attractor. Comm. Math. Phys. 1976, 50, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, T.C.; Jensen, M.H.; Kadanoff, L.P.; Procaccia, I.; Shraiman, B.I. Fractal measures and their singularities: the characterization of strange sets. Phys. Rev. A 1986, 33, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computed in Fractint by Wikimol, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution License. Available online: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lorenz_attractor_yb.svg (accessed on 20 April 2014).

- Prigogine, I.; Stengers, I. Order out of Chaos; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, C. What is progress in transdisciplinary research? Futures 2011, 43, 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Mobjörk, M. Consulting versus participatory transdisciplinarity: A refined classification of transdisciplinary research. Futures 2010, 42, 866–873. [Google Scholar]

- Lele, S.; Norgaard, R. Practicing Interdisciplinarity. BioScience 2005, 55, 967–975. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T. Beyond Culture; Anchor Books: Garden City, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Ramos, M.B., Ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P.; de Groot, E. Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 82, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanasupa, L.; Stolk, J.; Herter, R. The Four-Domain Development Diagram: A Guide for Holistic Design of Effective Learning Experiences for the Twenty-first Century Engineer. J. Eng. Educ. 2009, 98, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Science of the Learning Organization; Currency Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P. Systems thinking. In Rethinking Management Information Systems; Currie, W.L., Galliers, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 1999; pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. Leverage points. In Places to Intervene in a System; The Sustainability Institute: Hartland, VT, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Craighero, L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 27, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, P.; Torbert, W. The action turn: Toward a transformational social science. Concepts Trans. 2001, 6, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. Knowing-in-Action: The New Scholarship Requires a New Epistemology. Change 1995, 27, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.G.; Maturana, H.R.; Uribe, R. Autopoiesis: The organization of living systems, its characterization and a model. Biosystems 1974, 5, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H.; Holling, C.S. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Systems of Humans and Nature; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Logic: The Theory of Inquiry (1938). In The Later Works, 1925–1953; Board of Trustees, Southern Illinois University: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1984; pp. 1–549. [Google Scholar]

- Doll, W.E. Prigogine: A new sense of order, a new curriculum. Theor. Pract. 1986, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M. On the vitality of vitalism. Theor. Cult. Soc. 2005, 22, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, S. Critical theory and transformative learning. In The Handbook of Transformative Learning; Taylor, E.W., Cranston, P., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Vanasupa, L.; Schlemer, L.; Burton, R.; Brogno, C.; Hendrix, G.; MacDougall, N. Laying the Foundation for Transdisciplinary Faculty Collaborations: Actions for a Sustainable Future. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2893-2928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6052893

Vanasupa L, Schlemer L, Burton R, Brogno C, Hendrix G, MacDougall N. Laying the Foundation for Transdisciplinary Faculty Collaborations: Actions for a Sustainable Future. Sustainability. 2014; 6(5):2893-2928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6052893

Chicago/Turabian StyleVanasupa, Linda, Lizabeth Schlemer, Roger Burton, Courtney Brogno, Ginger Hendrix, and Neal MacDougall. 2014. "Laying the Foundation for Transdisciplinary Faculty Collaborations: Actions for a Sustainable Future" Sustainability 6, no. 5: 2893-2928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6052893

APA StyleVanasupa, L., Schlemer, L., Burton, R., Brogno, C., Hendrix, G., & MacDougall, N. (2014). Laying the Foundation for Transdisciplinary Faculty Collaborations: Actions for a Sustainable Future. Sustainability, 6(5), 2893-2928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6052893