A Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Use and Policies: Global and Turkish Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“Renewable Energy is derived from natural processes that are replenished constantly. In its various forms, it derives directly or indirectly from the sun, or from heat generated deep within the earth. Included in the definition is energy generated from solar, wind, biofuels, geothermal, hydropower and ocean resources, and biofuels and hydrogen derived from renewable resources.”

2. A Comparison of Renewable Energy Use around the World

| Region | Renewables in TPES (%) | Hydro (%) | Geothermal, Solar, Wind and Wave (%) | Biofuel and Renewable Waste (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 49.3 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 47.7 |

| Non-OECD Americas | 30.2 | 10.1 | 0.6 | 19.5 |

| Asia | 26.2 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 22.9 |

| China | 11.4 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 8.3 |

| Non-OECD Europe and Eurasia | 3.7 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 1.4 |

| Middle East | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| OECD | 7.8 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 4.4 |

| World | 13.0 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 9.8 |

| Turkey | 10.2 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 4.1 |

3. Renewable Energy Policies: Global Perspectives

Capital subsidy: a subsidy that covers a share of the upfront capital cost of an asset (such as a solar water heater).Feed-in premium: a type of feed-in policy, where producers of electricity from renewable sources sell electricity at market prices, and a premium is added to the market price to compensate for higher costs and, thus, to mitigate the financial risks of the production from renewables.Feed-in tariff: the basic form of feed-in policies, where a minimum price (tariff) per unit (normally kWh or MWh) is guaranteed over a stated fixed-term period when electricity can be sold and fed into the electricity network, normally with priority or guaranteed grid access and dispatch.Fiscal incentive: an economic incentive that provides individuals, households or companies with a reduction in their contribution to the public treasury via income or other taxes, or with direct payments from the public treasury in the form of rebates or grants.Investment tax credit: a taxation measure that allows investments in renewable energy to be fully or partially deducted from the tax obligations or income of a project developer, industry, building owner, etc.Mandate/obligation: a measure that requires designated parties (consumers, suppliers, generators) to meet a minimum, and often gradually increasing, target for renewable energy, such as a percentage of total supply or a stated amount of capacity.Net metering: a regulated arrangement in which utility customers who have installed their own generating systems pay only for the net electricity delivered from the utility (total consumption minus on-site self-generation).Production tax credit: a taxation measure that provides the investor or owner of a qualifying property or facility with an annual tax credit based on the amount of renewable energy (electricity, heat or biofuel) generated by that facility.Renewable energy certificate (REC): a certificate awarded to certify the generation of one unit of renewable energy (typically 1 MWh of electricity, but also less commonly of heat).Renewable energy target: an official commitment, plan or goal set by a government (at the local, state, national or regional level) to achieve a certain amount of renewable energy by a future date.Renewable portfolio standard (RPS): an obligation placed by a government on a utility company, group of companies or consumers to provide or use a predetermined minimum renewable share of installed capacity, or of electricity or heat generated or sold;” RPSs often include tradable certificates, and they are referred to as tradable green certificates (TGC systems) in Europe.[26]

| Country | Regulatory Policies And Targets | Fiscal Incentives and Public Financing | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ● existing national ○ existing sub-national N new R revised X removed/expired * sub-national | Renewable energy targets | Feed-in tariff/premium payment | Electric utility quota obligation/Renewable | Portfolio Standard (RPS) | Net metering | Tradable Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) | Tendering | Heat obligation/mandate | Biofuels obligation/mandate | Capital subsidy or rebate | Investment or production tax credits | Reductions in sales, energy, CO2, value-added | Tax (VAT), or other taxes | Energy production payment | Public investment, loans, or grants |

| China | R | R | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||

| United States | R * | R * | R * | R * | ● | R | ● | R | ○ | X | ○ | ○ | R | ||

| Germany | ○ | R | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||||

| Brazil | ○ | ○ | R | ● | R | ○ | R | R | |||||||

| Spain 1 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| Italy | ○ | R | ○ | ○ | ○ | R | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Denmark | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | R | |||||

| Canada | ● | R * | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Japan | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||||

| Sweden | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||||

| Turkey | ○ | R | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||||

| Austria | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| Cyprus | ○ | ○ | N | ○ | ○ | R | |||||||||

| India | R | ○ | ○ | N * | ○ | R | ● | R | R | ○ | R | ○ | |||

| Portugal | R | R | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | X | X | ○ | X | |||||

3.1. Renewable Energy Policies of Selected OECD Countries

3.2. Renewable Energy Policies of Some Non-OECD Countries

- Various energy-saving renovations are implemented.

- Efforts have been made to support new and renewable energy developments.

- Improvements have been made in civil energy use conditions (energy service level, access to natural gas and electricity, combined heat and power projects, etc.).

- Environmental protection has been increased.

- Promote and encourage the development and utilization of its rich solar energy resources with the construction of power stations, solar power generation projects, efforts to generalize solar heating, cooling, water heaters and industrial applications of solar energy.

- Make nuclear power plants safer and more efficient, especially after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011.

- Benefit from the biomass potential in rural areas.

- Electricity Act 2003, which mandates that each State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC) establish minimum renewable power purchases; allows for the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) to set a preferential tariff for electricity generated from renewable energy technologies; provides open access of the transmission and distribution system to licensed renewable power generators.

- National Electricity Policy 2005, which allows SERCs to establish preferential tariffs for electricity generated from renewable sources.

- National Tariff Policy 2006, which mandates that each SERC specify a renewable purchase obligation (RPO) with distribution companies in a time-bound manner with purchases to be made through a competitive bidding process.

- Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana (RGGVY) 2005, which supports extension of electricity to all rural and below poverty line households through a 90% subsidy of capital equipment costs for renewable and non-renewable energy systems.

- Eleventh Plan 2007–2012, which establishes a target that 10% of power-generating capacity shall be from renewable sources by 2012 (a goal that has already been reached) and supports phasing out of investment-related subsidies in favor of performance-measured incentives.

- National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) 2008, which aims to promote development goals while addressing greenhouse gases mitigation and climate change adaptation through eight specific missions (including solar energy, energy efficiency, water, sustainable habitat and related topics).

- The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) of the Kyoto Protocol, which supports the development of renewable energy projects.

3.3. Renewable Energy Policies of the EU

| Country | Renewable Energy Support Policies |

|---|---|

| Austria | Electricity: feed-in tariffs, subsidies for PV installations |

| Heating and cooling: incentive scheme on the level of the individual federal states | |

| Transport: quota system | |

| Cyprus | Electricity: subsidy combined with a net metering scheme |

| Heating and cooling: currently none | |

| Transport: currently none | |

| Denmark | Electricity: premium tariff and net-metering |

| Heating and cooling: exemption from tax obligations and a direct tariff for biogas | |

| Transport: quota system, tax incentives for biofuels and a direct premium tariff for selling of biogas | |

| Germany | Electricity: feed-in tariffs and low interest loans for investments in new plants Heating and cooling: Market Incentive Programme (MAP), investment support by the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA) and low interest loans |

| Transport: quota system and fiscal regulation for some types of biofuels | |

| Italy | Electricity: combination of premium tariffs, feed-in tariffs and tender schemes; tax regulation mechanisms for investment in plants |

| Heating and cooling: tax regulation system and a price-based mechanism for installations | |

| Transport: quota system for biofuels | |

| Portugal | Electricity: feed-in tariffs for existing installations and specific power granting tenders for new installations |

| Heating and cooling: currently none | |

| Transport: biofuel quota system and a tax exemption to small producers | |

| Spain | Electricity: a tax regulation system for related investments |

| Heating and cooling: currently none | |

| Transport: quota system for biofuels | |

| Sweden | Electricity: a quota system, tax regulation mechanisms and a subsidy scheme |

| Heating and cooling: tax exemptions | |

| Transport: tax exemption for biofuels |

- •

- reducing EU domestic greenhouse gas emissions by 40% below the 1990 level and by 2030,

- •

- increasing the share of renewable energy to at least 27% of the EU’s energy consumption by 2030, with flexibility for Member States to set national objectives

- •

- establishing a market stability reserve in 2021,

- •

- developing a set of key indicators to assess progress over time and to inform any future policy intervention, and

- •

- establishing a new governance framework based on national plans for competitive, secure and sustainable energy.

- Twenty two Member States were on track regarding the RES trajectories defined in the NREAPs, and six underachieved. Only France and The Netherlands did not meet the 2011/2012 milestone with respect to the interim targets defined in the RES Directive.

- In the RES-E sector, 12 Member States (Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden) met or overachieved on their 2012 target, with the most significant overachievement in Estonia (95% more RES-E than planned in the NREAP for 2012).

- In the RES-H & C sector, only five Member States (Ireland, Portugal, Latvia, France and The Netherlands) underachieved their 2012 target.

- In the RES-T sector, which has seen less progress than the former two, only eight Member States (Austria, Czech Republic, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Slovakia and Sweden) met or overachieved on their 2012 target.

- Continue to increase funding for research, development and deployment (RD&D) to meet the goals stated in the Energy Concept.

- Involve all stakeholders through a stronger co-ordination platform.

- Continue to assess its RD&D challenges and to adjust its RD&D portfolio as national energy policy priorities change.

- Continue efforts in energy education and training to meet future demands for researchers and engineers.

- Improve energy statistics to provide a solid perspective, especially those related to international energy prices and energy consumption in the household, transport, and trade sectors.

- The German Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) must be preserved in principle for the transformation of the electricity supply. Feed-in tariffs should be kept up-to-date to support technological innovations that reduce costs.

- Introduce non-budgetary subsidy instruments for the expansion of renewables in the heat sector to especially include the existing stock of older buildings.

- Set incentives and specifications in the transportation sector to further reduce the amount of fuel consumptions of motor cars and utility vehicles

4. Renewable Energy Status and Policies of Turkey

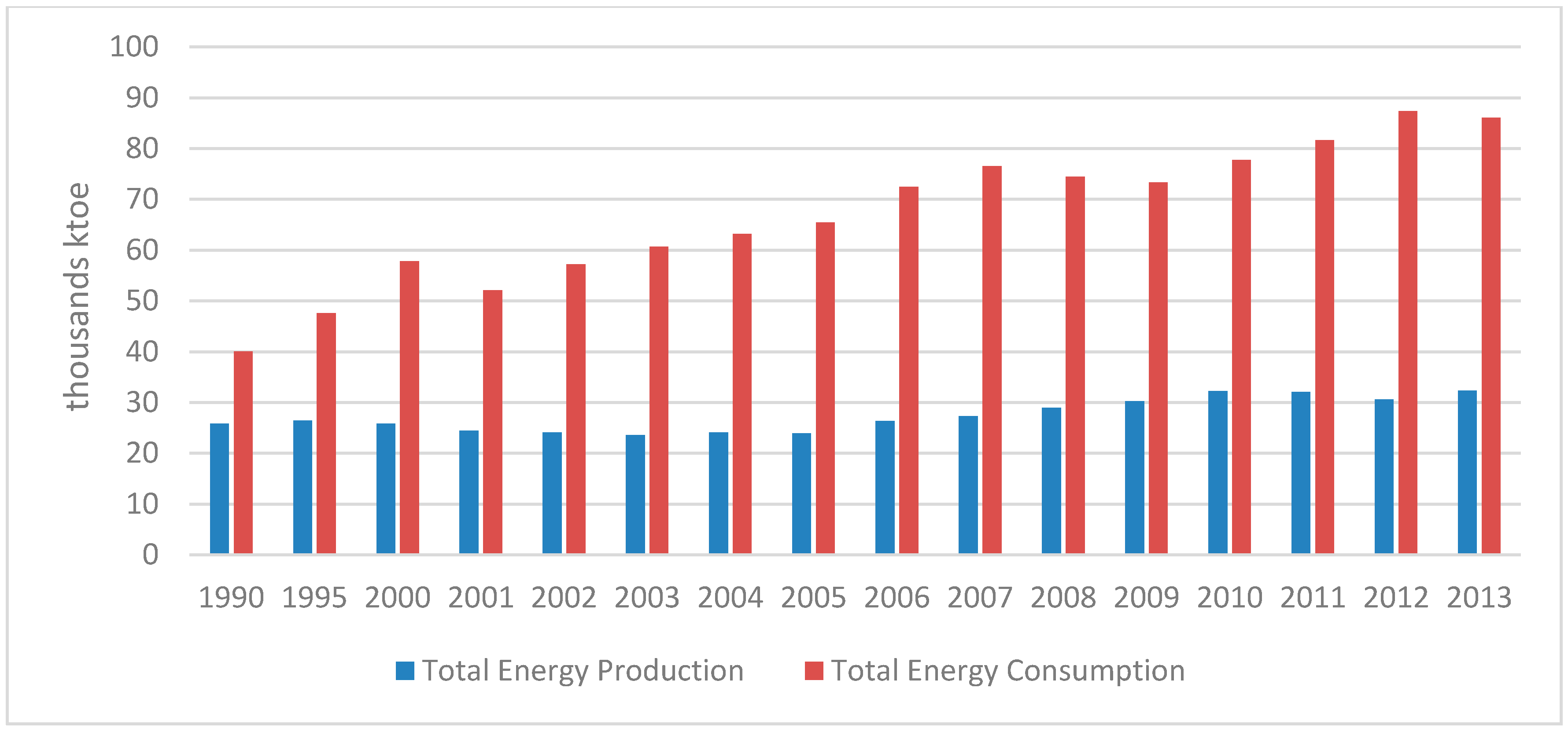

4.1. Current Energy and Renewable Energy Status in Turkey

- Hydro, which is the main and most developed RES in Turkey, with water resources being located in all seven geographical regions. Hydro accounted for 24% of electricity generation in 2012. There was an installed hydropower capacity of 6256 MW from rivers and 16,237 MW from reservoirs as of the end of January 2014. Overall, Turkey has 16% of Europe’s economic hydro potential.

- There is significant potential for wind power development in Turkey [62], with high average annual wind velocities creating the potential for its efficient utilization in the Mediterranean shores, Aegean Sea coast areas and the northern and western parts of the Marmara Sea coast. However, wind energy has had little, but increasing implementation in Turkey so far, with an installed capacity of 2815 MW as of the end of January 2014.

- Biomass has been a major source of renewable energy, but air pollution concerns and deforestation have resulted in a decrease in biomass use, changing the composition of the renewable energy supply in favor of wind energy [62,66]. The significant agricultural activities in large areas of the country provide residues for biomass combustion or gasification. The country also has combustible industrial waste, forestry and waste from wood processing, domestic and municipal waste and waste from areas polluted by oil and petroleum products, with a total potential of 8.6 billion toe. However, the installed capacity was only 239.6 MW, and the current energy use of biomass is 6 Mtoe, mainly for heating purposes.

- Turkey is rich in thermal waters. The geothermal potential for heating purposes is estimated to be 31,500 MW, of which 4809 MW has been made available as of the end of 2012. The installed capacity of geothermal energy was 310.8 MW as of the end of January 2014. Currently, geothermal energy is directly used for central heating systems, greenhouse heating and thermal tourism purposes.

- The climatic conditions and geographical location of Turkey especially in the southern half provide substantial potential for the production of electricity and heat using solar energy. Although the solar energy potential using concentrated solar power (CSP) technologies across the entire country is very high (380 TWh), there are no large-scale solar power installations. Currently, solar energy is widely used for water heating, greenhouse heating and for drying agricultural products. Solar collectors are available in 3–3.5 million residences, mostly in the Mediterranean, Aegean and Southeast Anatolian regions.

| Renewable Energy Sources | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary energy supply | |||||

| Hydro (ktoe) | 2861 | 3092 | 4454 | 4501 | 4976 |

| Geothermal, solar, etc. (ktoe) | 1643 | 2181 | 2648 | 3095 | 3508 |

| Biofuels and waste (ktoe) | 4829 | 4667 | 4559 | 3662 | 3653 |

| Energy production from renewables (ktoe) | 9333 | 9940 | 11,661 | 11,258 | 12,137 |

| Share of Renewables in TPES (%) | 9.5 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 10.0 | 10.4 |

| Electricity Generation | |||||

| Hydro (GWh) | 33,270 | 35,958 | 51,796 | 52,338 | 57,865 |

| Geothermal, solar, etc. (GWh) | 1009 | 1931 | 3584 | 5417 | 6759 |

| Biofuels and waste (GWh) | 219 | 340 | 457 | 469 | 721 |

| Electricity generation from renewables (GWh) | 34,498 | 38,229 | 55,837 | 58,224 | 65,345 |

| Share of renewable electricity generation in final electricity consumption * (%) | 21.6 | 24.7 | 32.8 | 31.6 | 33.9 |

| Total final consumption ** | |||||

| Geothermal, solar, etc. (ktoe) | 1431 | 1678 | 1823 | 2093 | 2231 |

| Biofuels and waste (ktoe) | 4771 | 4583 | 4441 | 3547 | 3529 |

| Total consumption from renewables (ktoe) | 6202 | 6261 | 6264 | 5640 | 5760 |

| Share of renewables in total final consumption (%) | 8.3 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 6.6 |

4.2. Energy Legislation in Turkey

- Exemption of 500 kW of installed capacity from licensing and setting up a company.

- Exemption from annual licensing costs for the first eight years upon license application and an initial fee of only 1% for the license application.

- Priority for system connection.

- Leasing, right of easement or usage permits to properties that are regarded as forest or private property of the Treasury.

- 85% discount in rent, right of easement and usage permits together with forest villagers development revenue and exemption from forestation and erosion control revenues during the first 10 years.

- Feed-in tariffs of 7.3, 7.3, 10.5, 13.3 and 13.3 USD $ cent/kWh for hydropower, wind energy, geothermal, biomass and solar radiation, respectively.

- Tax exemption for 2% biodiesel blending and premium for oil seeds.

4.3. International Energy Commitments

- The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline (opened in May 2005), which has a maximum capacity of one million barrels per day (or 50 million tonnes per year);

- The Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli (ACG) Project, which was established by the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) and currently provides oil to Turkey;

- The South Caucasus Natural Gas Pipeline (SCP) from Shah Deniz Field and the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) projects, which currently provide natural gas to Turkey.

4.4. Evaluation of Renewable Energy Policies and Strategies in Turkey

“Good progress has been made in the area of energy. Liberalisation of the electricity sector and the level of alignment with the Electricity Directive are advanced. However, a functioning competitive market and progress in legislative alignment in the natural gas sector are still lacking. Progress in the renewable energy sector needs to be speeded up, namely through streamlined administrative procedures. Further efforts are needed in the areas of energy efficiency and nuclear energy, in particular on alignment with relevant EU Directives. Overall, Turkey is at a rather advanced level of alignment in the field of energy.”

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCrone, A. Frankfurt School-UNEP Centre/BNEF. Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment; Frankfurt School of Finance & Management: Frankfurt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration Office (EIA). Annual Energy Outlook 2012 with Projections to 2035. 2012. Available online: www.eia.gov/forecasts/aeo (accessed on 2 April 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Komor, P.; Bazilian, M. Renewable energy policy goals, programs, and technologies. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Payne, J.E. Renewable energy consumption and economic growth: Evidence from a panel of OECD countries. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Policy Highlights; IEA: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum (WEF). Energy Vision 2013 Energy Transitions: Past and Future; WEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baris, K.; Kucukali, S. Availability of renewable energy sources in Turkey: Current situation, potential, government policies and the EU perspective. Energy Policy 2012, 42, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benli, H. Potential of renewable energy in electrical energy production and sustainable energy development of Turkey: Performance and policies. Renew. Energy 2013, 50, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, I.; Kaygusuz, K. Renewable energy sources for clean and sustainable energy policies in Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4132–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Bezir, N.C.; Ozek, N. Turkey’s Energy Production, Consumption, and Policies, until 2020. Energy Sources B 2009, 4, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D. Renewable energy policies in Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2006, 10, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MMO. Türkiye’nin Enerji Görünümü. In TMMOB Makine Mühendisleri Odası Raporu (MMO/588) (Genişletilmiş İkinci Baskı); MMO: Ankara, Turkey, 2012; Available online: http://www.mmo.org.tr/resimler/dosya_ekler/dd924b618b4d692_ek.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2013). (In Turkish)

- MMO. Türkiye’nin Enerji Görünümü. In TMMOB Makine Mühendisleri Odası Raporu (MMO/616) (Genişletilmiş Üçüncü Baskı); MMO: Ankara, Turkey, 2014; Available online: http://www.mmo.org.tr/resimler/dosya_ekler/9aca139809cf620_ek.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2015). (In Turkish)

- WWF-Türkiye (World Wide Fund for Nature-Türkiye) Yenilenebilir Enerji Geleceği ve Türkiye; WWF Rapor; WWF-Türkiye: Istanbul, Turkey, 2011; Available online: http://www.yesilekonomi.com/files/yenilenebilir-enerji-gelecegi-turkiye.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2013). (In Turkish)

- Yi, H.; Feiock, R.C. Renewable Energy Politics: Policy Typologies, Policy Tools, and State Deployment of Renewables. Policy Stud. J. 2014, 42, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadian, S.; Madani, K. The Water Demand of Energy: Implications for Sustainable Energy Policy Development. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4674–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigerna, S.; Bollino, C.A.; Polinori, P. The Question of Sustainability of Green Electricity Policy Intervention. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5378–5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioglu Akan, M.Ö.; Selam, A.A.; Fırat, S.Ü.O.; Er, M.; Özel, S. Renewable Energy Policies: A Comparison of Global and Turkish Perspectives. In Proceedings of the IAFOR North American Conference on Sustainability, Energy and the Environment, Providence, RI, USA, 11–14 September 2014.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Renewables Information 2010—IEA Statistics; IEA: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Renewables Information 2011—IEA Statistics; IEA: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Renewables Information 2012—IEA Statistics; IEA: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Renewables Information 2013—IEA Statistics; IEA: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Renewables Information 2014—IEA Statistics; IEA: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Selam, A.A.; Özel, S.; Arıoğlu Akan, M.Ö. Turkey’s Position among the OECD Countries within the Context of Renewable Energy Utilization. Dumlupinar Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Arioglu Akan, M.Ö.; Selam, A.A.; Fırat, S.Ü.O. Renewable Energy Sources: Comparison of their Use and Respective Policies on a Global Scale. In Handbook of Research on Green Economic Development Initiatives and Strategies, 1st ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; accepted for publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, R.; Panzer, C.; Resch, G.; Ragwitz, M.; Reece, G.; Held, A. A historical review of promotion strategies for electricity from renewable energy sources in EU countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1003–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21). Renewables 2014 Global Status Report; REN21 Secretariat: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Members and Partners. 2014. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/about/membersandpartners (accessed on 6 October 2014).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Balances of OECD Countries—IEA Statistics; IEA: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Saidel, M.A.; Alves, S.S. Energy efficiency policies in the OECD countries. Appl. Energy 2003, 76, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, A.; Wong, K.F.V. Analysis of renewable energy development to power generation in the United States. Renew. Energy 2014, 63, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Policies of IEA Countries—The United States 2014 Review; IEA: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. State Renewable Energy Governance: Policy Instruments, Markets, or Citizens. Rev. Policy Res. 2015, 32, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, A.; Zhang, J.; Gonela, V.; Awudu, I. Electricity generation from renewables in the United States: Resource potential, current usage, technical status, challenges, strategies, policies, and future directions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Energy Prospects: United States of America, REmap 2030 Analysis; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Novonous. India Renewable Energy Status Report 2014. Available online: http://www.ren21.net/portals/0/documents/resources/gsr/2014/gsr2014_full%20report_low%20res.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2015).

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Energy Prospects: China, REmap 2030 Analysis; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- China’s Energy Policy. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/english/official/2012-10/24/content_2250497.htm (accessed 6 October 2014).

- Liu, Z. Electric Power and Energy in China; Wiley: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, N. Investing in Wind Power: A Concise Guide to the Technologies and Companies for Investors; Harriman House Ltd.: Petersfield, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meisen, P.; Hawkins, S. Renewable Energy Potential of China: Making the Transition from Coal-Fired Generation. Available online: http://www.geni.org/globalenergy/research/renewable-energy-potential-in-china/Renewable%20Energy%20Potential%20in%20China.pdf (accessed 6 October 2014).

- Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Government of India (MNRE). Strategic Plan for New and Renewable Energy Sector for the Period 2011–2017. 2011. Available online: http://mnre.gov.in/file-manager/UserFiles/strategic_plan_mnre_2011_17.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2014). [Google Scholar]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Indian Renewable Energy Status Report: Background Report for DIREC 2010; NREL: Golden, CO, USA, 2010; Available online: http://ren21.net/Portals/0/documents/Resources/Indian_RE_Status_Report.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2015).

- Shrimali, G.; Goel, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Nelson, D. Solving India’s Renewable Energy Financing Challenge: Which Federal Policies Can Be Most Effective? 2014. Available online: http://climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Which-Federal-Policies-can-be-Most-Effective.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2015).

- Energy Charter Secretariat. In-Depth Energy Efficiency Policy Review of the Republic of Turkey. 2014. Available online: http://www.energycharter.org/fileadmin/DocumentsMedia/IDEER/IDEER-Turkey_2014_en.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2015).

- Menegaki, A.; Gurluk, S. Greece & Turkey; Assessment and Comparison of Their Renewable Energy Performance. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2013, 3, 367–383. [Google Scholar]

- European Wind Energy Association (EWEA). EU Energy Policy to 2050-Achieving 80%–95% Emissions Reductions; EWEA: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Renewable Energy Progress Report; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krozer, Y. Cost and benefit of renewable energy in the European Union. Renew. Energy 2013, 50, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Green Paper—2030 Framework for Climate and Energy Policies; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, K.; Edmonds, J.; Bakken, B.; Wise, M.; Kim, S.; Luckow, P.; Patel, P.; Graabak, I. EU 20-20-20 energy policy as a model for global climate mitigation. Clim. Policy 2014, 14, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquet, D. Policy instruments for renewable energy—From a European perspective. Renew. Energy 2013, 49, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzing, L.; Mitchell, C.; Morthorst, P.E. Renewable energy policies in Europe: Converging or diverging? Energy Policy 2012, 51, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legal Sources on Renewable Energy (RES Legal). 2015. Available online: http://www.res-legal.eu/ (accessed on 21 October 2015).

- European Commission (EC). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—A policy Framework for Climate and Energy in the Period from 2020 to 2030; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Forum for Renewable Energy Sources (EUFORES). EU Tracking Roadmap 2014 Keeping Track of Renewable Energy Targets towards 2020; EUFORES: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, M.; Kobashi, Y.; Okura, S.; Tkach-Kawasaki, L. Energy policy participation through networks transcending cleavage: An analysis of Japanese and German renewable energy promotion policies. Qual. Quant. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Policies of IEA Countries—Germany 2013 Review; IEA: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blazejczak, J.; Braun, F.G.; Edler, D.; Schill, W.P. Economic effects of renewable energy expansion: A model-based analysis for Germany. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 40, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholz, R.; Beckmann, M.; Pieper, C.; Muster, M.; Weber, R. Considerations on providing the energy needs using exclusively renewable sources: Energiewende in Germany. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregger, T.; Nitsch, J.; Naegler, T. Long-term scenarios and strategies for the deployment of renewable energies in Germany. Energy Policy 2013, 59, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotcioğlu, İ. Clean and sustainable energy policies in Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 5111–5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D.; Çanka Kılıç, F. Renewable Energies and Their Subsidies in Turkey and some EU countries- Germany as a Special Example. J. Int. Environ. Appl. Sci. 2012, 7, 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Yüksel, I.; Arman, H. Energy and Environmental Policies in Turkey. Energy Sources B 2014, 9, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, I. Renewable energy status of electricity generation and future prospect hydropower in Turkey. Renew. Energy 2013, 50, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toklu, E. Overview of potential and utilization of renewable energy sources in Turkey. Renew. Energy 2013, 50, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, H.A.; Simsek, N. Recent incentives for renewable energy in Turkey. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölük, G. Renewable Energy: Policy Issues and Economic Implications in Turkey. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2013, 3, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Turkey’s Renewable Energy Sector from a Global Perspective. 2012. Available online: https://www.pwc.com.tr/tr_TR/tr/publications/industrial/energy/assets/Renewable-report-11-April-2012.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2014).

- Kabakci, S.B.; Tanugur, Y. Waste in the Renewable Energy Legislations of European Union, United States and Turkey. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Clean Energy (ICCE), East Mediterranean University and University of Miami, Farnagusta, North Cyprus, 15–17 September 2010.

- European Commission (EC). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council—Turkey 2013 Progress Report; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Melikoglu, M. Hydropower in Turkey: Analysis in the view of Vision 2023. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Policies of IEA Countries—Turkey 2009 Review; IEA: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bezir, Ç.N.; Öztürk, M.; Özek, N. Renewable energy market conditions and barriers in Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Kaygusuz, K.; Sari, A. Sustainable Energy Policies in Turkey. Energy Sources B 2011, 6, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. Exploring and Contextualizing Public Opposition to Renewable Electricity in the United States. Sustainability 2009, 1, 702–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arıoğlu Akan, M.Ö.; Selam, A.A.; Oktay Fırat, S.Ü.; Er Kara, M.; Özel, S. A Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Use and Policies: Global and Turkish Perspectives. Sustainability 2015, 7, 16379-16407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71215820

Arıoğlu Akan MÖ, Selam AA, Oktay Fırat SÜ, Er Kara M, Özel S. A Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Use and Policies: Global and Turkish Perspectives. Sustainability. 2015; 7(12):16379-16407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71215820

Chicago/Turabian StyleArıoğlu Akan, Mahmure Övül, Ayşe Ayçim Selam, Seniye Ümit Oktay Fırat, Merve Er Kara, and Semih Özel. 2015. "A Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Use and Policies: Global and Turkish Perspectives" Sustainability 7, no. 12: 16379-16407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71215820

APA StyleArıoğlu Akan, M. Ö., Selam, A. A., Oktay Fırat, S. Ü., Er Kara, M., & Özel, S. (2015). A Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Use and Policies: Global and Turkish Perspectives. Sustainability, 7(12), 16379-16407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71215820