Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

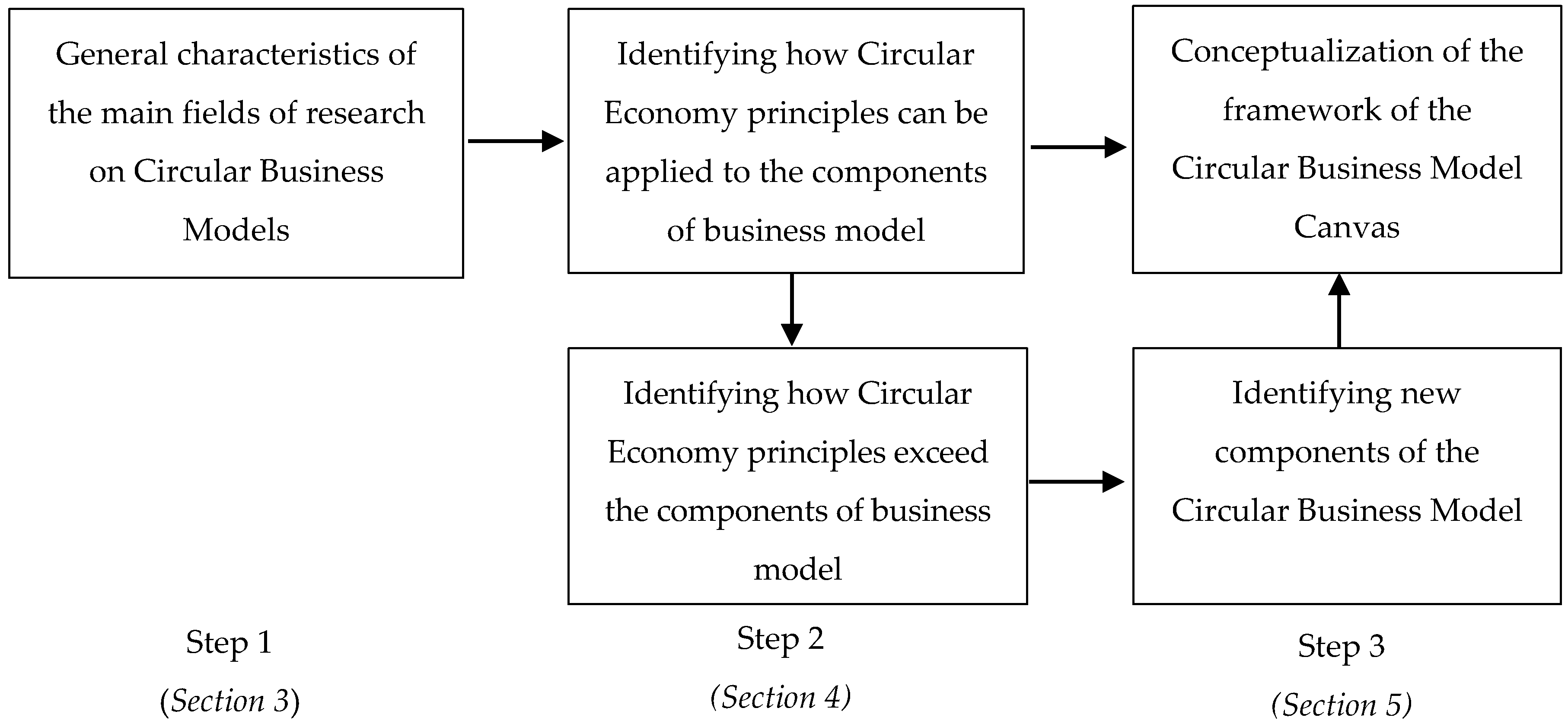

2. The Method and Concept of the Study

- (1)

- Identification of the state of the art on business models in the CE (circular business models)

- (2)

- Categorization of the initial body of literature according to the components of business model structure

- (3)

- Synthesis and development of the framework for a circular business model

2.1. Literature Review—Conceptual Frameworks for Categorizing the Research on Circular Business Models

| CBM Research Domains | Authors |

|---|---|

| Definitions | EMF Vol. 1&2 [2,4]; Joustra et al. [16]; Mentink [11]; Scott [3]; Lovins et al. [17]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Linder & Williander [18]; Ayres & Simonis [19]; Renner [20] |

| Components | EMF Vol. 1. [4]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund [21]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; EMF [23]; Mentink [11]; Govindan, Soleimani, & Kannan [24] |

| Taxonomies | Lacy et al. [25]; Bakker et al. [26]; Damen [27]; EMF Vol. 1. [4]; Lacy et al. [28]; WRAP [29]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Planing [5]; Jong et al. [14]; Tukker and Tischner [30]; Van Ostaeyen et al. [31]; El-Haggar [32]; Bakker et al. [33]; Ludeke-Freund [12]; Moser and Jakl [34]; Mentink [11]; Scott [3]; Bautista-Lazo [35]; Tukker [36]; EMF [6] |

| Conceptual Models | Mentink [11]; Wirtz [9]; Osterwalder and Pigneur [8]; Barquet et al. [10]; Osterwalder et al. [37]; Ludeke-Freund [12]; Dewulf [13]; Stubbs & Cocklin [38]; Roome and Louche [39]; Gauthier and Gilomen [40]; Abdelkafi and Tauscher [41]; Jabłoński [42]; Upward and Jones [43]; Nilsson & Söderberg [44] |

| Design Methods and Tools | Joustra et al. [16]; Jong et al. [14]; Scott [3]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Osterwalder and Pigneur [8]; Mentink [11]; Barquet et al. [10]; Jabłoński [42]; Parlikad et al. [45]; El-Haggar [32]; Guinée [46] |

| Adoption Factors | Winter [47]; Planing [5]; Lacy et al. [28]; Joustra et al. [16]; Scott [3]; Parlikad et al. [45]; Mentink [11]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; EMF Vol. 1. [4]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Scheepens et al. [48]; EMF [6]; Jong et al. [14]; Beuren et al. [49]; Jabłoński [50]; Pearce [51]; Linder & Williander [18]; Parlikad, et al. [45]; Beuren et al. [49]; Jabłoński (2015); Zairul et al. [52]; Roos [53]; Bechtel et al. [54]; UNEP [55]; Besch [56]; Heese et al. [57]; Walsh [58]; Firnkorn & Muller [59]; Shafiee & Stec [60] |

| Evaluation Models | Winter [47]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; Mentink [11]; EMF [23]; Andersson & Stavileci [61]; Jasch [62]; Jasch [63]; Gale [64] |

| Change Methodologies | Scott [3]; Roome & Louche [39]; Gauthier & Gilomen [40] |

2.2. Categorization of the Initial Body of Literature According to the Components of Business Model Structure

| BM components | Authors |

|---|---|

| Partners | Scott [3]; Joustra et al. [16]; El-Haggar [32]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Sheu [65]; Robinson et al. [66]; EMF Vol. 1. [4] |

| Key Activities | El-Haggar [32]; Scott [3]; WRAP [29]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28]; Rifkin [67]; Lacy et al. [25]; Joustra et al. [16]; EMF Vol. 3 [1]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; EMF Vol. 1. [4]; EMF [23]; EMF [6] |

| Key Resources | Planing [5]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28]; El-Haggar [32]; EMF [23]; Freyermuth [68]; Scott [3] |

| Value Proposition and Customer Segments | Jong et al. [14]; Planing [5]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28]; Parlikad et al. [45]; Bakker et al. [33]; El-Haggar [32]; Lacy et al. [25]; Scott [3]; EMF Vol. 1. [4]; Tukker and Tischner [30]; Tukker [36]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; Bakker et al. [26]; EMF [6] |

| Customer Relations | Renswoude et al. [7]; Recycling 2.0 [69]; Lacy et al. [25] |

| Channels | EMF [6]; Recycling 2.0 [69]; EMF [23] |

| Cost Structure | Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; Mentink [11]; Subramanian and Gunasekaran [70]; Sivertsson and Tell [71]; Berning and Venter [72]; Barquet et al. [10] |

| Revenue Streams | Van Ostaeyen et al. [31]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Tukker [36] |

| Additional Issues Related to Circular Economy | Material loops: EMF Vol. 1&2 [2,4]; Mentink [11]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28]; WRAP [29]; EMF Vol. 3 [1]; Govindan et al. [24]; El-Haggar [32]; EMF [23]; Freyermuth [68]; Scott [3]; Lacy et al. [25]; Planing [5]; |

| Adoption factors: Planing [5]; Scott [3]; El-Haggar [32]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; Lacy et al. [28]; Joustra et al. [16]; Jong et al. [14]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Barquet et al. [10]; Mentink [11]; Guinée [46]; EMF [23]; EMF [4]; EMF [6]; Parlikad et al. [45]; Stubbs & Cocklin [38]; Skelton and Pattis [73]; Winter [47] |

2.3. Synthesis and Development of the Framework of Circular Business Model

3. Research on Circular Business Models—The Review

3.1. Definitions

- (1)

- Design out waste/Design for reuse

- (2)

- Build resilience through diversity

- (3)

- Rely on energy from renewable sources

- (4)

- Think in systems

- (5)

- Waste is food/Think in cascades/Share values (symbiosis)

3.2. Components

- value propositions (what?)—products should become fully reused or recycled, which requires reverse logistics systems, or firms should turn towards product-service system (PSS) and sell performance related to serviced products

- activities, processes, resources and capabilities (how?)—products have to be made in specific processes, with recycled materials and specific resources, which may require not only specific capabilities but also creating reverse logistics systems and maintaining relationships with other companies and customers to assure closing of material loops

- revenue models (why?)—selling product-based services charged according to their use

- customers or customer interfaces (who?)—selling “circular” products or services may require prior changes of customer habits or, if this is not possible, even changes of customers

- (1)

- Sales model—a shift from selling volumes of products towards selling services and retrieving products after first life from customers

- (2)

- Product design/material composition—the change concerns the way products are designed and engineered to maximize high quality reuse of product, its components and materials

- (3)

- IT/data management—in order to enable resource optimization a key competence is required, which is the ability to keep track of products, components and material data

- (4)

- Supply loops—turning towards the maximization of the recovery of own assets where profitable and to maximization of the use of recycled materials/used components in order to gain additional value from product, component and material flows

- (5)

- Strategic sourcing for own operations—building trusted partnerships and long-term relationships with suppliers and customers, including co-creation

- (6)

- HR/incentives—a shift needs adequate culture adaptation and development of capabilities, enhanced by training programs and rewards

3.3. Taxonomies

| Classification Criteria | Model | Literature Sources | Explanation | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regenerate | Energy recovery | Damen [27]; Lacy et al. [28] | The conversion of non-recyclable waste materials into useable heat, electricity, or fuel | Ralphs and Food 4 Less installed an “anaerobic digestion” system |

| Circular Supplies | Lacy et al. [28]; EMF [23] | Using renewable energy | Iberdrola | |

| Efficient buildings | Scott [3] | Locating business activities in efficient buildings | Phillips Eco-Enterprise Center | |

| Sustainable product locations | Scott [3] | Locating business in eco-industrial parks | Kalundborg Eco-industrial Park | |

| Chemical leasing | Moser and Jakl [34] | The producer mainly sells the functions performed by the chemical, so the environmental impacts and use of hazardous chemical are reduced | Safechem | |

| Share | Maintenance and Repair | Lacy et al. [28]; WRAP [76]; Bakker et al. [33]; Planing [5]; Damen [27] | Product life cycle is extended through maintenance and repair | Patagonia, Giroflex |

| Collaborative Consumption, Sharing Platforms, PSS: Product renting, sharing or pooling | Lacy et al. [28]; Lacy et al. [25]; WRAP [76]; Planing [5]; Tukker [36]; Jong et al. [14] | Enable sharing use, access, or ownership of product between members of the public or between businesses. | BlaBlaCar, Airbnb, ThredUP, | |

| PSS: Product lease | Tukker [36]; Jong et al. [14]; WRAP [76]; | Exclusive use of a product without being the owner | Mud Jeans, Dell, Leasedrive, Stone Rent-a-PC | |

| PSS: Availability based | Van Ostaeyen, et al. [31]; Mentink [11] | The product or service is available for the customer for a specific period of time | GreenWheels | |

| PSS: Performance based | Van Ostaeyen, et al. [31]; Zairul et al. 2015 [52] | The revenue is generated according to delivered solution, effect or demand-fulfilment | Philips’s “Pay per Lux” solution; the need for new housing model for young starters in Malaysia | |

| Incentivized return and reuse or Next Life Sales | WRAP [76]; Mentink [11]; Lacy et al. [25]; Damen [27] | Customers return used products for an agreed value. Collected products are resold or refurbished and sold | Vodafone Red Hot, Tata Motors Assured | |

| Upgrading | Planing [5]; Mentink [11] | Replacing modules or components with better quality ones | Phoneblocks | |

| Product Attachment and Trust | Mentink [11] | Creating products that will be loved, liked or trusted longer | Apple products | |

| Bring your own device | WRAP [76] | Users bring their own devices to get the access to services, | Citrix pays employees for bringing own computers | |

| Hybrid model | Bakker et al. [26] | A durable product contains short-lived consumables | Océ-Canon printers and copiers | |

| Gap-exploiter model | Bakker et al. [26]; Mentink [11] | Exploits “lifetime value gaps” or leftover value in product systems. (e.g., shoes lasting longer than their soles). | printer cartridges outlasting the ink they contain | |

| Optimise | Asset management | WRAP [76] | Internal collection, reuse, refurbishing and resale of used products | FLOOW2, P2PLocal |

| Produce on demand | Renswoude et al. [7]; WRAP [76], Scott [3] | Producing when demand is present and products were ordered | Alt-Berg Bootmakers, Made, Dell Computer Company | |

| Waste reduction, Good housekeeping, Lean thinking, Fit thinking | Renswoude et al. [7]; Scott [3]; El-Haggar [32]; Bautista-Lazo [35] | Waste reduction in the production process and before | Nitech rechargeable batteries | |

| PSS: Activity management/outsourcing | Tukker [36] | More efficient use of capital goods, materials, human resources through outsourcing | Outsourcing | |

| Loop | Remanufacture, Product Transformation | Damen [27]; Planing [5]; Lacy et al. [25] | Restoring a product or its components to “as new” quality | Bosch remanufactured car parts |

| Recycling, Recycling 2.0, Resource Recovery | Lacy et al. [25] Damen [27] Planing [5]; Lacy et al. [28] | Recovering resources out of disposed products or by-products | PET bottles, Desso | |

| Upcycling | Lacy et al. [28] Mentink [11]; Planing [5] | Materials are reused and their value is upgraded | De Steigeraar (design and build of furniture from scrap wood) | |

| Circular Supplies | Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28] | Using supplies from material loops, bio based- or fully recyclable | Royal DSM | |

| Virtualize | Dematerialized services | WRAP [76]; Renswoude et al. [7] | Shifting physical products, services or processes to virtual | Spotify (music online) |

| Exchange | New technology | EMF [6] | New technology of production | WinSun 3D printing houses |

3.4. Conceptual Models

- (1)

- Customer segments that an organization serves

- (2)

- Value propositions that seek to solve customers’ problems and satisfy their needs

- (3)

- Channels which an organization uses to deliver, communicate and sell value propositions

- (4)

- Customer relationships which an organization builds and maintains with each customer segment

- (5)

- Revenue streams resulting from value propositions successfully offered to customers

- (6)

- Key resources as the assets required to offer and deliver the aforementioned elements

- (7)

- Key activities which are performed to offered and deliver the aforementioned elements

- (8)

- Key partnerships being a network of suppliers and partners that support the business model execution by providing some resources and performing some activities

- (9)

- Cost structure comprising all the costs incurred when operating a business model

- Economic characteristics, such as external bodies expecting triple bottom line performance, lobbying for changes to taxation system and legislation to support sustainability, keeping capital local

- Environmental characteristics, such as a threefold strategy (offsets, sustainable, restorative), closed-loop systems, implementation of services model, operating in industrial ecosystems and stakeholder networks

- Social characteristics, such as understanding stakeholder’s needs and expectations, educating and consulting stakeholders

- Economic characteristics, such as considering profit as a means to do something more (“higher purpose”), not as an end, which is also a reason for shareholders to invest

- Environmental characteristics, such as treating nature as a stakeholder

- Social characteristics, such as balancing stakeholders’ expectations, sharing resources among stakeholders, and building relationships

- Holistic characteristics, such as focusing on medium to long-term effects, and on reducing consumption

3.5. Design Methods and Tools

3.6. Adoption Factors

3.7. Evaluation Models

3.8. Change Methodologies

- (1)

- Business model as usual—if there are no transformations to business model elements

- (2)

- Business model adjustment—if marginal modifications to one element of BMs occur

- (3)

- Business model innovation—if major BM transformations were implemented

- (4)

- Business model redesign—if a complete rethinking of organizations’ BM elements results in radically new value propositions

4. Circular Economy and the Components of Business Model

4.1. Value Propositions Fitting Customer Segments (Value Proposition Design)

4.2. Channels

4.3. Customer Relationships

4.4. Revenue Streams

4.5. Key Resources

4.6. Key Activities

4.7. Key Partnerships

4.8. Cost Structure

4.9. The Need for Additional Components of a Business Model Related to the Circular Economy

| BM Components | Regenerate | Share | Optimize | Loop | Virtualize | Exchange |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partners | X | X | ||||

| Activities | X | X | X | X | ||

| Resources | X | X | X | X | ||

| Value proposition and Customer segments | X | X | X | |||

| Customer relations | ||||||

| Channels | X | |||||

| Cost structure | X | X | X | X | ||

| Revenue streams | X | X | ||||

| Potential to develop the BM framework | ||||||

| Take-back system | X | |||||

| Adoption factors | X | X | X | X | X | X |

5. Conceptualizing the Framework of the Circular Business Model Canvas

5.1. Key Areas of Redesigning a Business Model Framework

5.2. Take-Back System

5.3. Adoption Factors

5.4. The Framework of the Circular Business Model Canvas

- (1)

- Value propositions—offered by circular products enabling product-life extension, product-service system, virtualized services, and/or collaborative consumption. Moreover, this component comprises the incentives and benefits offered to the customers for bringing back used products

- (2)

- Customer segments—directly linked with value proposition component. Value proposition design depicts the fit between value proposition and customer segments

- (3)

- Channels—possibly virtualized through selling virtualized value proposition and delivering it also virtually, selling non-virtualized value propositions via virtual channels, and communicating with customers virtually

- (4)

- Customer relationships—underlying production on order and/or what customers decide, and social-marketing strategies and relationships with community partners when recycling 2.0 is implemented

- (5)

- Revenue streams—relying on the value propositions and comprising payments for a circular product or service, or payments for delivered availability, usage, or performance related to the product-based service offered. Revenues may also pertain to the value of resources retrieved from material loops

- (6)

- Key resources—choosing suppliers offering better-performing materials, virtualization of materials, resources allowing to regenerate and restore natural capital, and/or the resources obtained from customers or third parties meant to circulate in material loops (preferably closed)

- (7)

- Key activities—focused on increasing performance through good housekeeping, better process control, equipment modification and technology changes, sharing and virtualization, and on improving the design of the product, to make it ready for material loops and becoming more eco-friendly. Key activities might also comprise lobbying

- (8)

- Key partnerships—based on choosing and cooperating with partners, along the value chain and supply chain, which support the circular economy

- (9)

- Cost structure—reflecting financial changes made in other components of CBM, including the value of incentives for customers. Special evaluation criteria and accounting principles must be applied to this component

- (10)

- Take-Back system—the design of the take-back management system including channels and customer relations related to this system

- (11)

- Adoption factors—transition towards circular business model must be supported by various organizational capabilities and external factors

5.5. The Triple Fit Challenge as the Enabler of the Transition Towards a Circular Business Model

5.6. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Circular Business Model Canvas

6. Future Research

7. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Accelerating the Scale-up Across Global Supply Chains. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_ENV_TowardsCircularEconomy_Report_2014.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy. Opportunities for the Consumer Goods Sector. Available online: http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/TCE_Report-2013.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Scott, J.T. The Sustainable Business a Practitioner’s Guide to Achieving Long-Term Profitability and Competitiveness, 2nd ed.; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Available online: http://mvonederland.nl/system/files/media/towards-the-circular-economy.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Planing, P. Business Model Innovation in a Circular Economy Reasons for Non-Acceptance of Circular Business Models. Open J. Bus. Model Innov. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Delivering the Circular Economy a Toolkit for Policymakers; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Renswoude, K.; Wolde, A.T.; Joustra, D.J. Circular Business Models. Part 1: An introduction to IMSA’s Circular Business Model Scan. Available online: https://groenomstilling.erhvervsstyrelsen.dk/sites/default/files/media/imsa_circular_business_models_-_april_2015_-_part_1.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, B.W. Business Model Management: Design—Instruments—Success Factors, 1st ed.; Springer Science+Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barquet, A.P.B.; de Oliveira, M.G.; Amigo, C.R.; Cunha, V.P.; Rozenfeld, H. Employing the business model concept to support the adoption of product-service systems (PSS). Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentink, B. Circular Business Model Innovation: A Process Framework and a Tool for Business Model Innovation in a Circular Economy. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology & Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F. Towards a Conceptual Framework of Business Models for Sustainability. In Knowledge Collaboration & Learning for Sustainable Innovation, Proceedings of the ERSCP-EMSU Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 25–29 October 2010.

- Dewulf, K.R. Play it forward: A Game-based tool for Sustainable Product and Business Model Innovation in the Fuzzy Front End. In Knowledge Collaboration & Learning for Sustainable Innovation, Proceedings of the ERSCP-EMSU Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 25–29 October 2010.

- De Jong, E.; Engelaer, F.; Mendoza, M. Realizing Opportunities of a Circular Business Model. Available online: http://circulatenews.org/2015/04/de-lage-landen-realising-the-opportunities-of-a-circular-business-model (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Pateli, A.G.; Giaglis, G.M. A research framework for analysing eBusiness models. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joustra, D.J.; de Jong, E.; Engelaer, F. Guided Choices towards a Circular Business Model; North-West Europe Interreg IVB: Lille, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lovins, A.B.; Lovins, L.H.; Hawken, P.; June, M.A.Y. A Road Map for Natural Capitalism. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linder, M.; Williander, M. Circular Business Model Innovation: Inherent Uncertainties. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, R.U.; Simonis, U.E. Industrial Metabolism: Restructuring for Sustainable Development; United Nations University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Renner, G.T. Geography of Industrial Localization. Econ. Geogr. 1947, 23, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: state-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubscher, M.; Marinelli, T. Integration of Circular Economy in Business. In Proceedings of the Conference: Going Green—CARE INNOVATION 2014, Vienna, Austria, 17–20 November 2014.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, K.; Soleimani, H.; Kannan, D. Reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chain: A comprehensive review to explore the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 240, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lacy, P.; Rosenberg, D.; Drewell, Q.; Rutqvist, J. 5 Business Models that are Driving the Circular Economy. Available online: http://www.fastcoexist.com/1681904/5-Business-Models-That-Are-Driving-the-Circular-Economy (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Bakker, C.A.; den Hollander, M.C.; van Hinte, E.; Zijlstra, Y. Products That Last—Product Design for Circular Business Models, 1st ed.; TU Delft Library/Marcel den Hollander IDRC: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Damen, M.A. A Resources Passport for a Circular Economy. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, P.; Keeble, J.; McNamara, R.; Rutqvist, J.; Haglund, T.; Cui, M.; Cooper, A.; Pettersson, C.; Kevin, E.; Buddemeier, P.; et al. Circular Advantage: Innovative Business Models and Technologies to Create Value in a World without Limits to Growth; Accenture: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- WRAP. Innovative Business Model Map. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/content/innovative-business-model-map (accessed on 4 October 2015).

- Tukker, A.; Tischner, U. Product-services as a research field: Past, present and future. Reflections from a decade of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1552–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ostaeyen, J.; van Horenbeek, A.; Pintelon, L.; Duflou, J.R. A refined typology of product–service systems based on functional hierarchy modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haggar, S. Cleaner Production. In Sustainable Industrial Design and Waste Management: Cradle-to-Cradle for Sustainable Development; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, C.; Wang, F.; Huisman, J.; den Hollander, M. Products that go round: Exploring product life extension through design. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 69, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, F.; Jakl, T. Chemical leasing—A review of implementation in the past decade. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 22, 6325–6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista-Lazo, S. Sustainable Manufacturing: Turning Waste Into Profitable Co-Products; University of Liverpool: Liverpool, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A. Eight Types of Product Service Systems: Eight Ways To Sustainability? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Bernarda, G.; Smith, A. Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “Sustainability Business Model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roome, N.; Louche, C. Journeying Toward Business Models for Sustainability: A Conceptual Model Found Inside the Black Box of Organisational Transformation. Organ. Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gauthier, C.; Gilomen, B. Business Models for Sustainability: Energy Efficiency in Urban Districts. Organ. Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkafi, N.; Täuscher, K. Business Models for Sustainability From a System Dynamics Perspective. Organ. Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, A. Design and Operationalization of Technological Business Models. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun. 2015, 63, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upward, A.; Jones, P. An Ontology for Strongly Sustainable Business Models: Defining an Enterprise Framework Compatible With Natural and Social Science. Organ. Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nilsson, N.; Söderberg, V. How to Future Proof a Business Model: Capture and Capitalize Value in the Field of Urban Mining. Master’s Thesis, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Parlikad, A.K.; Mcfarlane, D.; Fleisch, E.; Gross, S. The Role of Product Identity in End-of-Life Decision Making. Available online: www.alexandria.unisg.ch/export/DL/Sandra_Gross/21460.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Guinée, J.B. Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment: Operational Guide to the ISO Standards. In Book Review: The Second Dutch LCA-Guide; Springer Science+Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 311–313. [Google Scholar]

- De Winter, J. Circular Business Models: An Opportunity to Generate New Value, Recover Value and Mitigate Risk Associated with Pressure on Raw Material Availability and Price Volatility. Master’s Thesis, University of Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scheepens, A.E.; Vogtländer, J.G.; Brezet, J.C. Two life cycle assessment (LCA) based methods to analyse and design complex (regional) circular economy systems. Case: Making water tourism more sustainable. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuren, F.H.; Gomes Ferreira, M.G.; Cauchick Miguel, P.A. Product-service systems: A literature review on integrated products and services. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, A. Network Dynamics and Business Model Dynamics in Improving a Company’s Performance. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A. The Profit-Making Allure of Product Reconstruction. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2009, 50, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zairul, M.; Wamelink, J.W.; Gruis, V.; John, L. New industrialised housing model for young starters in Malaysia: Identifying problems for the formulation of a new business model for the housing industry. In Proceedings of the APNHR 2015: The Asia Pacific Network for Housing Research, Gwangju, Korea, 9–11 April 2015.

- Roos, G. Business Model Innovation to Create and Capture Resource Value in Future Circular Material Chains. Resources 2014, 3, 248–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, N.; Bojko, R.; Völkel, R. Be in the Loop: Circular Economy & Strategic Sustainable Development. Master’s Thesis, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation Environment Programme (UNEP). Product-Service Systems and Sustainability; UNEP: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Besch, K. Product-service systems for office furniture: Barriers and opportunities on the European market. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heese, H.S.; Cattani, K.; Ferrer, G.; Gilland, W.; Roth, A.V. Competitive advantage through take-back of used products. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2005, 164, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B. PSS for Product Life Extension through Remanufacturing. In Proceedings of the 2nd CIRP IPS2 Conference, Linköping, Sweden, 14–15 April 2010; pp. 261–266.

- Firnkorn, J.; Müller, M. Selling Mobility instead of Cars: New Business Strategies of Automakers and the Impact on Private Vehicle Holding. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2012, 21, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A.; Stec, T. Gaining a Competitive Advantage with Sustainable Business—Implementing Inductive Charging using Systems Thinking, A Benchmarking of EVs and PHEVs. Master’s Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Göteborg, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, D.; Stavileci, S. An Assessment of How Circular Economy can Be Implemented in the Aerospace Industry. Master’s Thesis, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jasch, C. How to perform an environmental management cost assessment in one day. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1194–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasch, C. Environmental management accounting (EMA) as the next step in the evolution of management accounting. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, R. Environmental management accounting as a reflexive modernization strategy in cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.-B. Green Supply Chain Collaboration for Fashionable Consumer Electronics Products under Third-Party Power Intervention—A Resource Dependence Perspective. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2832–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Brase, G.; Griswold, W.; Jackson, C.; Erickson, L. Business Models for Solar Powered Charging Stations to Develop Infrastructure for Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7358–7387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freyermuth, G.S. Edges & Nodes/Cities & Nets: The History and Theories of Networks and What They Tell Us about Urbanity in the Digital Age. Available online: http://periodicals.narr.de/index.php/real/article/view/1576/1555 (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Waste Management. Recycling 2.0: Recycling Engagement and Education. Available online: http://www.cafr.org/summit/speakers/ppt/2015-06-08_11:10:00__Robinson_Susan.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Subramanian, N.; Gunasekaran, A. Cleaner supply-chain management practices for twenty-first-century organizational competitiveness: Practice-performance framework and research propositions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 164, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivertsson, O.; Tell, J. Barriers to Business Model Innovation in Swedish Agriculture. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1957–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, A.; Venter, C. Sustainable Supply Chain Engagement in a Retail Environment. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6246–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skelton, K.; Pattis, A. Life Cycle Management In Product Development: A Comparative Analysis of Industry Practices Kristen. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Life Cycle Management, Gothenburg, Sweden, 25–28 August 2013.

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltiomre, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberger, K.; Weiblen, T.; Csik, M.; Gassmann, O. The 4I-framework of business model innovation: A structured view on process phases and challenges. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2013, 18, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRAP. Innovative Business Models. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/content/innovative-business-models-1 (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Mahadevan, B. Business Models for Internet-Based E-Commerce: An Anatomy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A.; Tucci, C.L. Internet Business Models and Strategies: Text and Cases, 1st ed.; Mcgraw-Hill College: Columbus, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Papakiriakopoulos, D.A.; Poylumenakou, A.K.; Doukidis, G.J. Building E-Business Models: An Analytical Framework and Development Guidlines. In Proceedings of the 14th Bled Electronic Commerce Conference, Bled, Slovenia, 25–26 June 2001.

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, J.; Cantrell, S. Changing Business Models: Surveying the Landscape; Accenture Institute for Strategic Change: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Al-debei, M.M.; El-Haddadeh, R.; Avison, D. Defining the Business Model in the New World of Digital Business. In Proceedings of the 14th Americas Conference on Information Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 14–17 August 2008.

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Tucci, C.L. Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the Concept. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Lazo, S.; Short, T. Introducing the All Seeing Eye of Business: A model for understanding the nature, impact and potential uses of waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxel, H.; Esenduran, G.; Griffin, S. Strategic sustainability: Creating business value with life cycle analysis. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.J. Business models for open innovation: Matching heterogenous open innovation strategies with business model dimensions. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 33, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kocabasoglu, C.; Prahinski, C.; Klassen, R.D. Linking forward and reverse supply chain investments: The role of business uncertainty. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.; Pigneur, Y. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. In Proceedings of the ARTEM Organizational Creativity International Conference, Nancy, France, 26–27 March 2015.

- Talonen, T.; Hakkarainen, K. Elements of sustainable business models. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2014, 6, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seay, S.S. How incorporating a sustainable business model creates value. Bus. Stud. J. 2015, 7, 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, M. Introduction to Academic Entrepreneurship. In Academic Entrepreneurship and Technological Innovation; Szopa, A., Karwowski, W., Ordóñez de Pablos, P., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lewandowski, M. Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010043

Lewandowski M. Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework. Sustainability. 2016; 8(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleLewandowski, Mateusz. 2016. "Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework" Sustainability 8, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010043