Abstract

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are increasingly aware of the benefits of closing loops and improving resource efficiency, such as saving material costs, creating competitive advantages, and accessing new markets. At the same time, however, various barriers pose challenges to small businesses in their transition to a circular economy, namely a lack of financial resources and lack of technical skills. The aim of this paper is to increase knowledge and understanding about the barriers and enablers experienced by SMEs when implementing circular economy business models. Looking first at the barriers that prevent SMEs from realising the benefits of the circular economy, an investigation is carried out in the form of a literature review and an analysis of a sample of SME case studies that are featured on the GreenEcoNet EU-funded web platform. Several enabling factors that help SMEs adopt circular economy practices are then identified. The paper concludes that although various policy instruments are available to help SMEs incorporate circular economy principles into their business models, several barriers remain. The authors recommend that European and national policies strengthen their focus on greening consumer preferences, market value chains and company cultures, and support the recognition of SMEs’ green business models. This can be achieved through the creation of dedicated marketplaces and communities of practice, for example.

1. Introduction

The circular economy is a concept rooted in several different schools of thought and theories that question the prevailing linear economic systems, which assume that resources are infinite [1,2,3]. Among the first authors considered to have influenced the development of the circular economy concept is Kenneth Boulding [4], who in 1966 envisaged a “spaceman economy” that would operate by reproducing the initially limited stock of inputs and recycling waste outputs. This concept has since evolved such that today policy-makers, academics, and the business community increasingly recognise the need to move towards a new economic model whereby materials and energy from discarded products or byproducts are reintroduced into the economic system [5,6]. In terms of environmental benefits, becoming more circular would help avoid emissions, reduce the loss of resources, and ease the burden on global ecosystems [7]. For example, it has been estimated that the transition to a circular economy in the mobility, food, and built environment sectors could lead to emissions reductions of 48% by 2030 and 83% by 2050, compared with 2012 levels [8].

Looking beyond environmental sustainability, the economic benefits and business relevance of the circular economy are also increasingly recognised among academics and policy-makers. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation [6] estimates that the potential net material cost savings in a more circular economy in medium-lived complex products industries (in particular for motor vehicles, machinery, and equipment, as well as electrical machinery) at EU-level could be as high as $630 billion annually, while in the fast-moving consumer goods sector (mainly packaged food, apparel, and beverages) net materials savings at global level could exceed $700 billion annually. Furthermore, technological and organisational innovations underpinning a circular economy would allow Europe’s resource productivity to grow by 3% by 2030, equating to €1.8 trillion total benefits in three areas: mobility, food, and the built environment, including savings in primary resource costs and in costs linked to externalities, such as health impacts from air pollution [8].

Beyond cost savings, closing production-to-waste loops and increasing the re-use and recycling of materials would reduce demand for virgin materials and help to mitigate both demand-driven price volatility on raw material markets (e.g., for iron ore) and supply risks [9]. In addition, the uptake of circular business models was found to be associated with great employment potential: estimates for the United Kingdom show that a circular economy at current development rates could lead to net job creation of approximately 54,000 jobs by 2030, particularly in recycling and remanufacturing [10]. For the Netherlands, Bastein et al. [11] estimate that improving circular business models in the base metals and metal product industries, in the electronics and electrical appliances industry, and in the management of biotic waste, could create more than 50,000 jobs.

While these findings imply clear benefits for businesses that adopt circular business models, in actual practice there can be several barriers in the form of, for example, difficulties in valuing future benefits against current costs, knowledge needs, and market pull-and-push factors, such as availability of technologies and consumer demand for green products [12]. Both larger and smaller enterprises face such barriers, albeit to differing extents. For example, while a multinational company can support circular technology development through its research and development activities, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often depend on the availability of technology in the market. Moreover, while multinationals may be able to determine how circular economy concepts are adopted, an SME is, due to its size, often restricted to observing the trends in the market value chain in which it operates. Although both larger enterprises and SMEs are crucial for the circular economy, this article focuses on the role of the latter. SMEs are a substantial part of the business environment, with over 99% of European enterprises belonging to the SME category and around two-thirds of European employment being generated by SMEs [13].

Research on SMEs has shown that they are becoming increasingly aware of the benefits of improving resource efficiency even though, as illustrated in the literature review of this paper, they do not often link them well to the concept of a circular economy. Saving material costs, creating competitive advantages, and new markets are among the main reasons for European SMEs to take action [14]. For instance, by implementing a certified Environmental Management System (EMS), two-thirds of SMEs surveyed in a U.K. Defra study found their sales increased by £14,961 on average per € million turnover per year [15]. However, as explained, it is not always easy for SMEs to reap the benefits of more circular approaches. Based on an EU-funded online dataset of European SMEs, this paper identifies a number of barriers to adopting a more sustainable, circular-type of business model and also identifies possible enabling factors to overcome these barriers.

In the literature review presented in Section 2 below, the identification of barriers to implementing circular economy business models in SMEs has been based on a wide range of surveys and sources. These sources have based their analyses on firms in general, or specifically on SMEs, or on a subset thereof, e.g., SMEs in a geographic area (see, for example, [16,17]) and/or sector (see [18,19]). These enterprises may not yet have taken steps towards circular business models, however; consequently, their answers may be based more on perceptions than on actual experience. This paper adds to the analysis by focusing on EU SMEs that have already implemented circular economy business models and thus managed to overcome possible barriers. Another novel element can be found in the consideration of representative SME sectors across different European countries that have successfully introduced circularity into their business models, facilitating the cross-sectoral knowledge development. This can prove to be especially important, since the switch to a circular economy is applicable for several sectors and can follow similar paths and patterns.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature and categorizes the main barriers to the implementation of circular economy solutions by SMEs. Section 3 presents the methodology for the analysis of case studies featured in the online SME platform, as well as the main barriers and enablers encountered by the sampled SMEs. Section 4 discusses the research results and their management and scientific implications. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions and policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

In order to identify potential barriers preventing SMEs from adopting circular economy business models, a literature review has been conducted. Based on the review, barriers have been categorised as follows: company environmental culture, lack of capital, lack of government support/effective legislation, lack of information, administrative burden, lack of technical and technological know-how, and lack of support from the supply and demand network. The categories are explained further below.

Barriers under company environmental culture refer to the philosophy, habits, and attitudes of the company (manager and employees) towards implementing circular economy business practices [16]. For instance, in many SMEs, the manager is also the company owner with a significant say over the strategic decisions of the company. In this respect, some SME managers may have a positive attitude towards the circular economy, while others may not [17,20]. Furthermore, SME owners or managers may have different risk perceptions. A strong risk aversion on the part of managers can hinder the enactment of the circular economy, even following the evaluation of the benefits associated with its implementation [16,21]. An additional complexity is that decision-makers need to estimate the concrete value propositions before proceeding to circular economy practices; to assess the costs of circular measures, taking into account the risks of change in the current business environment; and acknowledge that a more long-term perspective needs to be adopted. Resistance to change keeps business models locked in their conventional configuration and may constitute a major bottleneck in micro-small companies [22,23]. The attitudes and behaviour of employees also fall under the same category; while working for an environmentally conscious company may motivate some employees, others are more reluctant or are unaware of how to change business-as-usual operations, or may even perceive green practices as additional workload [19,24].

Lack of capital has been cited extensively in the literature as one of the most salient barriers to the adoption of circular economy by SMEs [25]. Shifting from a linear to a circular production/business model requires activities such as distribution planning, inventory management, production planning, and management of a reverse logistics network [22], requiring a substantial amount of time and investment on the part of the company [26]. The level of upfront costs, the indirect (time and human resources) costs and the anticipated payback period are particularly important for SMEs, as they are generally more sensitive than large enterprises to any additional costs resulting from green business [27,28]. For example, in some cases product service business models (e.g., leasing services) demand higher upfront costs than sale transaction business models [22], while some producers regard product services as a threat to their production business models [23,29,30]. Implementing a circular economy business model also demands continuous monitoring and improvement of the product’s lifecycle; hence, a significant amount of resources would need to be allocated by the company to keep all parties (i.e., employees and customers) committed [26]. Additionally, external financing through, for example, EU and government grants, is often difficult to access, since SME staff and management restrictions do not usually allow for careful assessment of such opportunities [31,32]. Regarding commercial bank financing, SMEs often face difficulties in obtaining the collateral or guarantees required by banks [26,33], while economic recession rendered access to financing capital even more difficult for circular economy propositions. Finally, there are no new methods of financing available to promote innovative business models [22].

The lack of government support/effective legislation (through the provision of funding opportunities, training, effective taxation policy, laws and regulations, etc.) is widely recognised as a significant barrier to the uptake of environmental investments [34,35]. The lack of a concrete, coherent, and strict legislative framework often impedes SMEs’ consideration of integrating green solutions in their operations. For example, in EU waste legislation there is no coherent definition or classification of waste materials (e.g., to distinguish waste from byproduct materials used for recycling), thus inducing limitations on cross-border transportation of waste [36], while there are significant differences in the ambition of targets along the waste hierarchy [37]. This is reinforced by the lack of appropriate market signals (low prices of raw materials), which does not encourage the efficient use of resources or the transition to a circular economy [38]. As such, externalities (environmental costs), namely negative impacts on public health and environment, are not factored into the price of the products [22,39]. Additionally, circular business models can be excessively influenced by the fact that resource taxes are quite low, hence companies prefer to purchase cheaper raw materials rather than use recycled ones, which often entails supplementary processing costs [40,41].

Innovation policies rarely integrate new circular business model opportunities, as their main focus is on incremental innovation and efficiency [22]. Moreover, competition legislation hinders collaboration between companies and discourages understanding of the circular design and development of products and reverse infrastructure. On the one hand, sharing knowledge about business processes may harm a firm’s competitiveness, while, on the other hand, close collaboration among firms within product value chains can be viewed as cartel formation [22]. Finally, it has been reported that in some countries the enforcement of environmental regulations is not yet wholly effective, which does not encourage companies to seek prospective buyers for their byproducts. Similar discrepancies are also encountered in other fiscal policy instruments, such as “consumption taxes” of polluting products to control consumption habits, inhibiting the adoption of green consumption attitudes by consumers [39].

Studies have also highlighted the lack of information about the benefits of the circular economy [42] and environmental legislation [43]. In this context, a survey of 300 European firms conducted by the FUSION EU co-funded project [44] showed that most firms had either never heard of the term ‘circular economy’, or could not understand its meaning. On the positive side, when participants were given a simpler definition of circular economy, involving aspects such as the re-use and recovery of waste materials, the majority responded that they were actually already making efforts to recycle and repair. Companies also identified waste management as a sector that could unlock new business opportunities. A similar study conducted with the participation of 157 firms in China concluded that there is a relatively good understanding of the circular economy, but there is still a remarkable ‘gap’ between a firm’s awareness and actual behaviour due to a number of contextual and cultural factors [16]. The successful transition to a circular economy can only be achieved through collective effort, requiring exchange and dissemination of knowledge and innovation among different stakeholders in the value chain. Yet it is often the case that information is guarded confidentially by companies [36,45] or that people find it difficult to communicate their expertise, thereby preventing the broader dissemination and development of circular economy business models [21]. Due to the limited application of new circular business models, the track record of successful paradigms that would enhance practical knowledge is not yet extensive enough, which induces uncertainty in introducing circular practices [22]. The lack of an information exchange system constitutes an additional barrier to the effective adoption of circular business models. Confidentiality, lack of trust, and competition issues (along with competition legislation, as discussed earlier) inhibits the sharing of knowledge and product information among companies and forms a barrier to co-production, innovation, and the effective end-of-life management of products [46,47].

The administrative burden related to green business practices, such as monitoring and reporting environmental performance data, can be considered complex and barely affordable for SMEs. For instance, in many cases SMEs are required to submit the same data to various authorities and in different formats, but the expertise for that often needs to be sought among external consultants [35,48]. Moreover, adopting a circular business model can entail more complex and costly management and planning processes [22].

Lack of technical and technological know-how can hinder SMEs from transforming their linear business model into a circular one [16,28,45]. Linear technologies are widely established in the current business practices, keeping the economy locked into its current form [22]. Transforming business-as-usual operations would require new sustainable production and consumption technologies (in the fields of eco-design, clean production, and life cycle assessment) to be integrated into current linear business models, and competent professionals to be able to manage them. Nevertheless, the demand for environmentally friendly technologies is often quite low, and the technical capacities are inadequate [39]. Lack of technical know-how may result in SMEs adopting linear technologies and business models they are familiar with, and depending on their suppliers’ suggestions for innovative technical solutions [35]. Furthermore, the insufficient investment in technologies focusing on circular product designs (eco-design) and operations [45], the lack of advanced resource efficiency technologies [49], along with the low pricing signal of raw materials [36] are factors that are likely to impede the adoption of circular economy approaches by SMEs. A different bottleneck that has been reported is that of the increasing complexity in the mixes of materials in new products, rendering their management by current recycling infrastructure quite challenging [50].

Finally, the barrier of lack of support from the supply and demand network refers mainly to the dependency of SMEs on their suppliers’ and customers’ engagement in sustainable activities. The successful implementation of a circular economy necessitates the collaboration of all parties across the supply chain [26,36]. Nevertheless, suppliers and service partners may be reluctant to get involved in innovative circular economy processes owing to perceived risks to their competitive advantage or due to a mindset that does not prioritise circular economy practices [18]. Adopting a circular business model is likely to increase complexity throughout the supply chain (with regard to logistical, financial, and legal aspects), impacting the value chain of a product, process or service. In this context, issues related to governance (ownership, share of costs, and benefits along the value chain) need to be settled so that effective circular business models can be employed. Managing the transition in circular supply chains can be time-consuming, expensive, and may require collaboration with new market players [22,51]. Especially for micro-small companies, one of the major barriers is the lock-in of distribution channels [52], as well as the unpredictable return flow of materials (hampering the efficient retrieval of products) in circular practices involving the remanufacturing and reuse of products [30]. For example, in the case of remanufacturing photocopiers, the main challenge is to have the required labour to deal with the rate of photocopier returns [41].

On the other hand, insufficient customer awareness of the benefits of green products does not encourage a change in consumption patterns, and often there is no substantial pressure from the demand side on smaller organisations to meet sustainability criteria or develop a circular economy business model [53,54,55,56]. The transition to a circular economy necessitates a shift in consumers’ lifestyle and behaviour. Yet some may perceive circular economy practices as more costly and hard-to-implement alternatives with no tangible benefits, or may be unwilling to change their concepts of consumption and ownership (goods being perceived as symbols of social status) [57]. The public’s response is generally hard to predict since it is largely dependent on social norms and external conditions [36,58]. Furthermore, powerful stakeholders across the value chains may resist change due to their status quo interests, impacting the progress of small players towards innovative business models. Because of their low bargaining power, frontrunner SMEs seeking to establish a closed-loop business model are more likely to face additional costs due to the uneven allocation of power among stakeholders in the supply chain [45,56]. Policy initiatives to charge externalities or increase taxes on raw materials may also be resisted by powerful stakeholders with conflicting interests [2].

3. Analysis of SME Circular Economy Business Models

In this section we analyse whether and how SMEs that have successfully introduced circularity into their business models have faced the barriers identified in the literature review, and how they have been able to overcome them. For this purpose, we use a sample of SME case studies from the GreenEcoNet web platform.

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. Case Study Structure, Sustainability, and Application Scope

GreenEcoNet [59] is a web platform financed by the European Commission and developed by six European research organisations with the objective of showcasing examples of SMEs that have successfully made a change towards a green business model. The collection of innovative best practice examples (i.e., case studies) is one of the principal goals of the online platform, in order to inspire other enterprises to make similar business transitions. Case studies featured in the GreenEcoNet platform refer to the real-life SME experiences of introducing a ‘green solution’ that contributes to the transition to a green business model.

There are multiple definitions of a “case study” in the literature and different methodologies for case study analysis. For example, according to Yin [60] (p. 18) “a case study is an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”. Case study analysis constitutes one of many methods of performing qualitative analysis; others include surveys, experiments, etc. Yin [60] outlines five components as being particularly important to case studies, namely: a study’s questions; its propositions; its unit(s) of analysis; the logic linking the data to the propositions; and the criteria for interpreting the findings. Case study analysis usually follows protocol approaches to assist the researcher in carrying out the analysis and increasing the reliability of the research. Such protocols were developed by Yin [61] and Stake [62], for example.

In the context of GreenEcoNet platform, however, the term “case study” has been used to denote an example of where a green solution (either technological or business innovation) was successfully implemented. In this sense, a case study was designed to include the minimum data deemed necessary to ensure the evaluation and the replicability of the example by other businesses and institutions. In other words, a “GreenEcoNet case study” was first and foremost a way to structure data, and gathering insight on enablers or obstacles was a secondary goal.

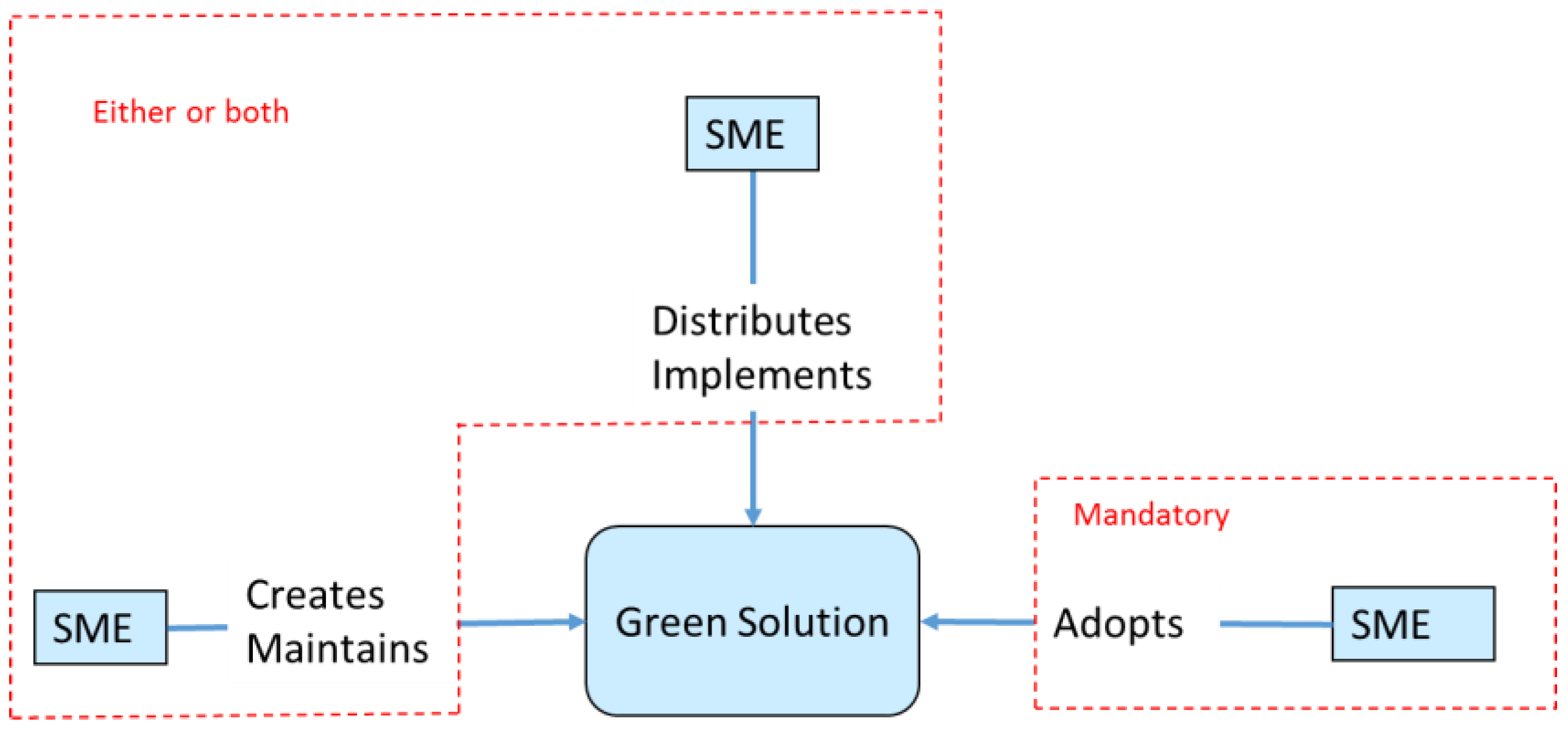

The major entity analysed in a GreenEcoNet case study, namely the “unit of analysis”, is the green solution featured on the online platform. In the context of the platform, a “green solution” is used in the broadest sense and can refer to products, technological processes, services, organisational methods, or business processes that improve operational performance, productivity, or efficiency, reduce environmental risk and resource use, and facilitate compliance with environmental regulations, etc. The best-practice examples have been selected on the basis of their relevance to sustainability principles, and of the scope of their application. As far as this scope is concerned, to be included in the GreenEcoNet platform a case study needs to have at its core a green solution, preferably related to the key activities or resources of the company. To prevent the case study from being an advertisement, it should include an SME adopter (end-user) of the green business model [63]. A case study in the GreenEcoNet platform therefore has the structure presented in Figure 1 below:

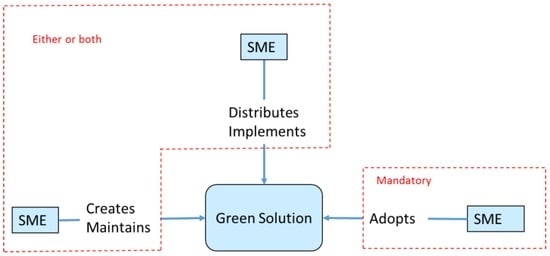

Figure 1.

Structure of case study in the GreenEcoNet platform [63].

According to this structure, businesses involved in the case study can be categorised as producers of green solutions, distributors and implementers (i.e., service providers), and adopters or end-users of green business models. Producers of green solutions are businesses that develop, create, and sell green solutions (such as Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs)). Distributors and implementers undertake the distribution, study/planning, and installation of the green solution, while adopters/end-users seek to embody resource-efficient and environmentally beneficial technologies or business practices in the way they carry out their operations [63].

The case studies have been collected by the GreenEcoNet team members through desk-based research, as well as through their stakeholder networks. The information used to generate each case study has been collected using a template based on a taxonomy that encompasses the categorisation of the private sector part of the green economy. This in turn has been validated through feedback from a focus group composed of eight experts from the business, academia, and research environments (more details on the taxonomy of the private sector part of the green economy can be found in [63]). The resulting template enables collection of both qualitative and quantitative information about the development, adoption, and/or implementation of a product or service that resulted in enhanced natural resources efficiency with respect to the available alternative. The template also enables collection of information on barriers and enabling factors (for more details, see Section 3.1.3, below).

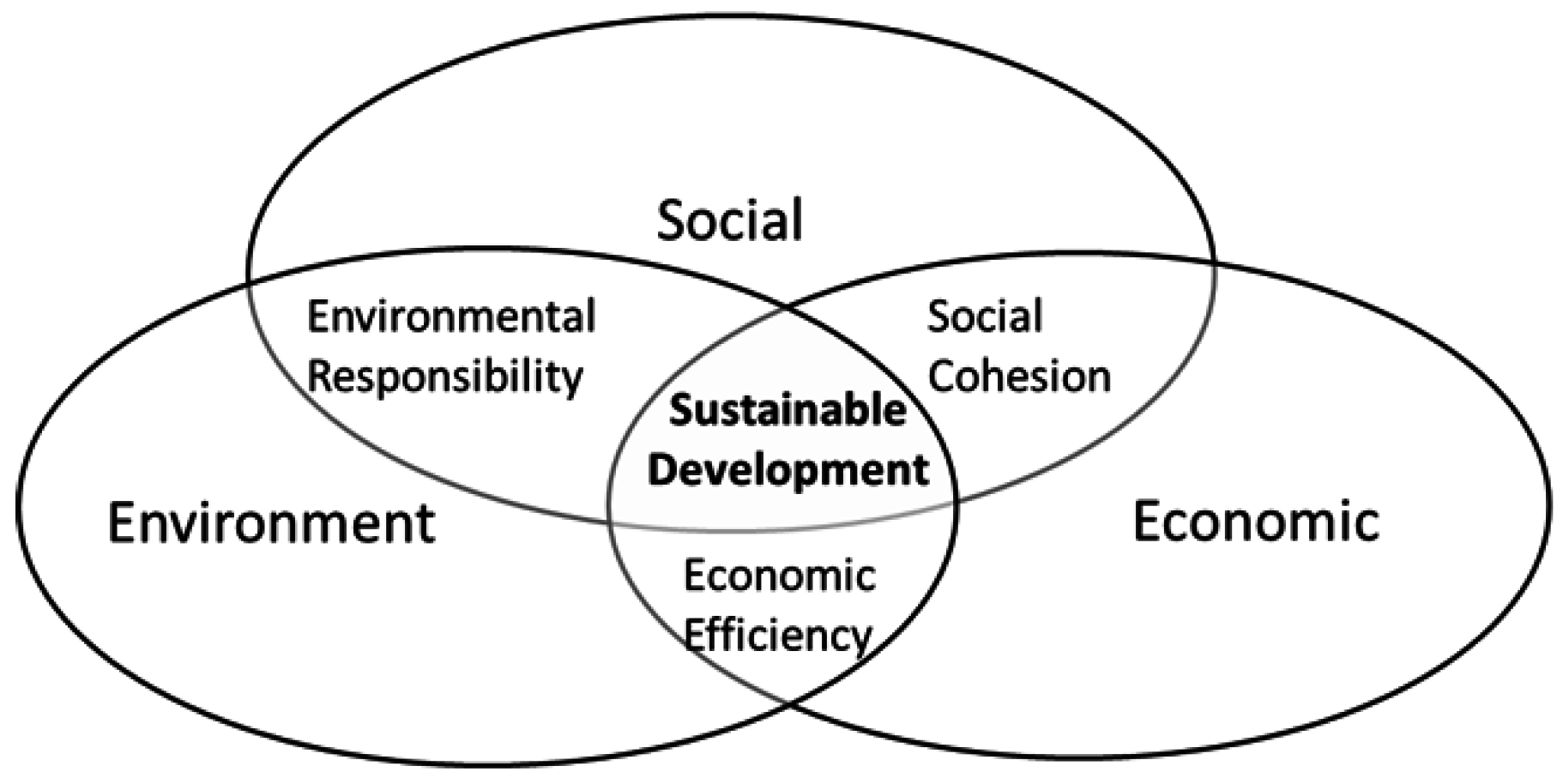

Apart from the narrative part of the case study description, users need to provide explicit information on the sustainability of their green business model. The compilation of specific sustainability information of the green business model in the case study template follows the three pillars of sustainability framework (see Figure 2). As such, users are requested to include information on: (1) Financial costs/benefits of the green solution; (2) Environmental benefits the solution has achieved; and (3) Social Benefits, namely, if the solution included a specific intervention to improve social well-being.

Figure 2.

Three pillars of sustainability framework (own design based on [64,65]).

Prior to publication on the platform, each case study is reviewed by at least two different experts of the GreenEcoNet team to ensure its relevance and content quality. Final case study drafts are also approved by the SME concerned, which is a direct reflection of the company’s willingness to share its experience through an online network. The collected case studies thus represent a specific subset of SMEs in Europe that have implemented a green solution, which should not be considered representative of all SMEs in European countries and sectors.

3.1.2. Sample Selection

At the time of writing this paper, the platform featured 52 business case studies. From this pool the team had to select the case studies that fitted into the circular economy concept and also contained sufficient information on barriers and enablers.

In the available literature the circular economy has been described as an industrial economy that relies on the “restorative capacity of natural resources” [11] and aims to minimise—if not eliminate—waste, utilise renewable sources of energy, and phase out the use of harmful substances [6]. Such an economy goes beyond the “end of pipe” approaches of the linear economy [66] and seeks transformational changes across the breadth of the value chain in order to retain materials in the “circular economy loop” and preserve their value for as long as possible [9,38]. Through fundamental changes to production and consumption systems the circular economy would entail several environmental benefits, for example decreased emissions and pollutants [67]. These descriptions from the literature are in line with the broad definition by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre [68] (p. 1): “In a circular economy, resources—including energy and materials—are used in circles. They are transformed, used, segregated, retransformed and reused in the most efficient and sustainable way possible“. In its Communication “Closing the loop—An EU Action Plan for the circular economy” the European Commission [69] (p. 2) expands on the idea of an economy “where the value of products, materials and resources is maintained in the economy for as long as possible, and the generation of waste minimised“. Based on the above definitions, the team selected case studies that described the development, adoption, and/or implementation by an SME of a product or service, resulting in a more efficient use of material and energy resources, and in turn a decreased environmental impact (for instance, in terms of emissions or waste production).

An additional quality check was performed to assess the quality and availability of information on barriers/enablers in the available case studies. In some cases this information was not detailed enough. In order to fill this data gap and validate the information provided, we contacted the entrepreneurs and requested to interview them. During these telephone/Skype interviews, we asked SME owners to explain in greater detail the barriers and enablers they encountered with their business. This allowed us to complement the information that was already in the database. Interviews were used because we found them to be the quickest and most efficient method to collect additional data. Case studies for which additional information was not sufficient were not included in the sample. Eventually, from the 52 case studies available on the online platform, 30 were selected for further analysis on barriers and enablers in this paper.

3.1.3. Analysis of Information

Once the sample of case studies was selected, the team collected information on the barriers and enablers experienced by those SMEs that have implemented circular economy business models. As discussed, SMEs have to provide this information when submitting their solution to the platform since it is part of the standard case study template. In the template the questions “Barriers/challenges/Lessons learnt—what barriers/challenges did your organisation face? What worked particularly well? What would you do differently next time?” appear in the “Description of the case study” box, encouraging SMEs to answer by providing insights into what barriers they faced and what enablers helped them succeed. In addition, another box in the template asks “Regulatory framework prerequisites and constraints?” providing a space where regulatory barriers could be reported. The barriers and enablers listed for each SME were then grouped into the categories identified in the literature review conducted for this paper, based on the expert judgement of the team. This allowed us to move to the quantitative part of our analysis by determining the percentage of SMEs in the sample that was affected by each category of barriers and enablers.

As a disclaimer, it is noted that while a barrier/enabler may be mentioned often by SMEs, this does not automatically imply that it has been the most significant barrier/enabler in each individual case study. It should also be clarified that the enablers can be identified as direct solutions for clearing an existing barrier (e.g., start-up financing to address the barrier of lack of capital) but also as favourable conditions (rather than measures to overcome a specific barrier) in an SME for improving the environmental performance of business operations (e.g., an owner committed to sustainability practices).

The team also decided to conduct a thorough description of the sample by analysing it quantitatively, based on the filtering criteria used in the online database. On the “Solutions” page of GreenEcoNet, solutions can be filtered by country, solution type (e.g., “technology/product”, “training”), technology area (e.g., “resource efficiency”, “energy production”, “waste treatment and recycling”), and SME sector (e.g., “manufacturing”, “accommodation and food service activities”). The different options for each of these filters were determined at the beginning of the GreenEcoNet project through the taxonomy cited above. We thus consider that these filters allow for a solid and objective description of the SME sample.

The methodology for this analysis was based on the expert judgement of the team, informed by literature reviews conducted throughout the project and the expert advice of various stakeholders who were consulted throughout the duration of the project. These included representatives of small business associations, resource efficiency experts, policy-makers, and small business owners.

3.2. Barriers and Enablers Derived from GreenEcoNet SME Case Studies

3.2.1. Sample Description

Regarding the geographical coverage of the sampled 30 case studies, 70% of them are from the United Kingdom and 17% from the Netherlands. The four remaining SMEs are based in Estonia, Belgium, Germany, and Greece. The lack of geographical diversity contrasts with the variety of sectors from which the SMEs come: 40% manufacturing sector, 13% information and communication, 10% wholesale and retail, 7% electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply, 7% accommodation and food service activities, and 7% transportation and storage. Five case studies are in other sectors such as: administrative support; arts, entertainment, and recreation; and human health and social work activities.

Each of these SMEs has strategies that include one or more green solutions. The most common type of green solution in our sample is a green technology/product (70% of SMEs), followed by organisational methods and (green) business plans (50%). Other types of green solutions in the case studies are training (20%), IT (7%), networking and communication (7%), and financing (3%).

Each of the case studies also belongs to one or more technology areas. Resource efficiency (41% of case studies) is the most represented technology area, followed by waste treatment and recycling (16%), materials (10%) and energy production (10%). Transportation (8%) and buildings (7%) are two other technology areas covered by the sample.

Regardless of the type of solution and the technology area it belongs to, we made a distinction between SMEs that produce, supply or install a green solution (56% of the sample), and those that have adopted a green solution (37%). Seven percent of the SMEs fulfil both roles. As an example, an SME produced an environmental management system (i.e., a green solution) and also adopted it.

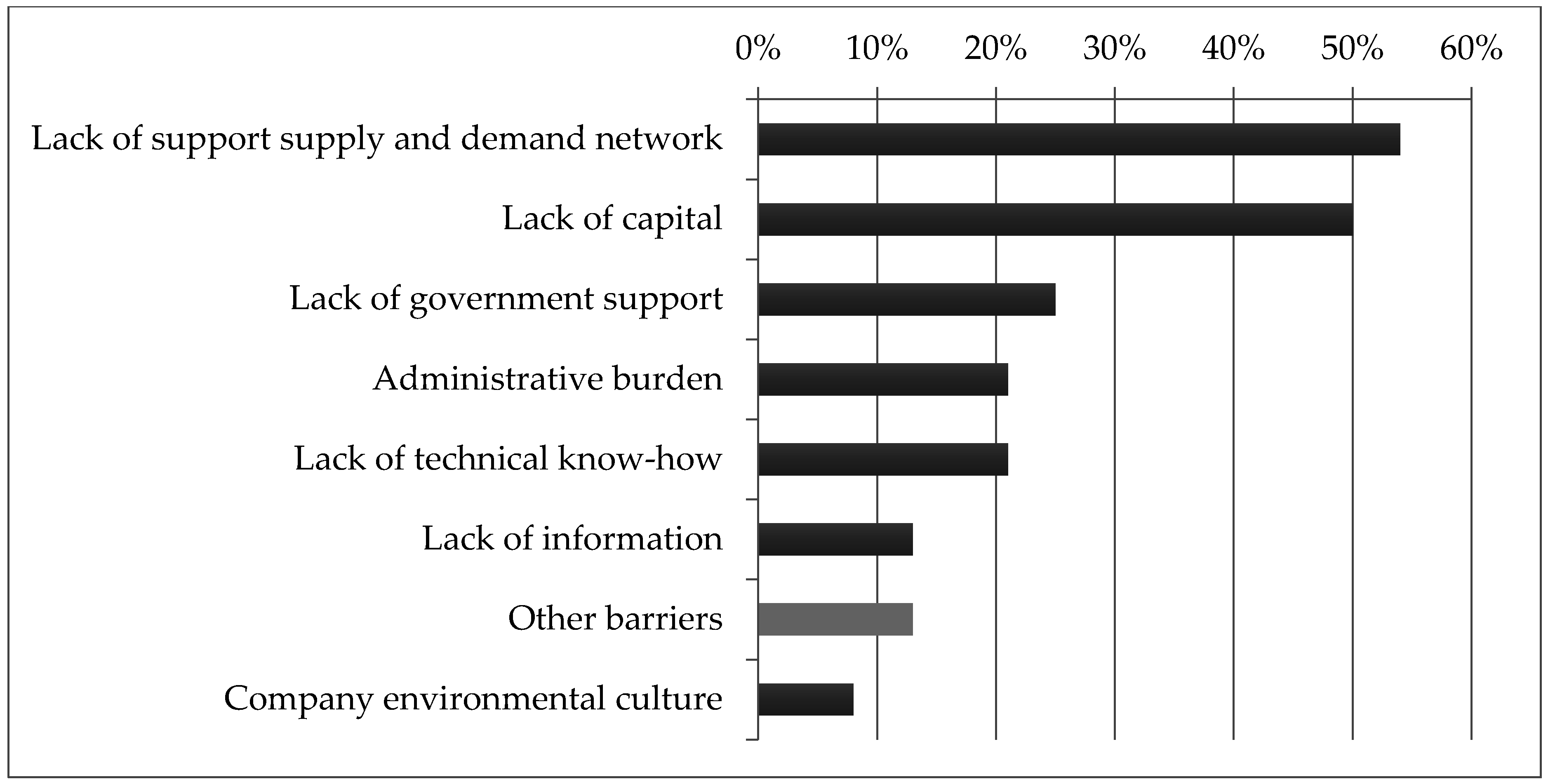

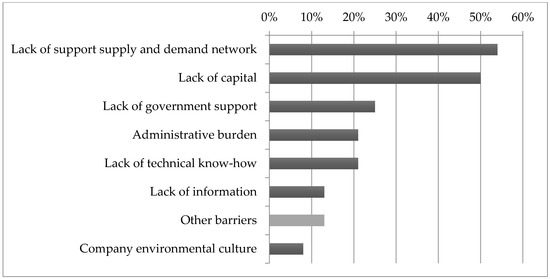

3.2.2. Barriers

More than half of the sampled SMEs (54%) mention the lack of support from the supply and demand network as their main barrier in the transition towards a circular economy. From a supply perspective, a major challenge seems to be the absence of “green” suppliers for specific inputs that the SME needs in the production process of a product or a service. According to the SMEs, in most cases markets for these inputs are absent or insufficiently developed in the supply chain. Additionally, some SMEs report difficulties in implementing a green solution since they are locked in at the bottom of the supply chain or they are part of global supply chains sectors with correlated high environmental impact. From a demand perspective, a major challenge underlined by the majority of SMEs is the need to create a business case for customers in order to buy a green product or to use a green service. According to the SMEs, the following issues are responsible for the lack of support from the demand-side network: the need to provide accurate figures and additional evidence of benefits related to green goods and services, the need to convince potential customers that the circular economy approach is the way forward, and the misperception of customers that green products and services are of lower quality than traditional goods and services.

Lack of capital is also a very frequently cited barrier (50%) in the sample, which in many cases refers to lack of initial capital, lack of financial opportunities or alternatives to private funds and traditional bank funding. Under “lack of capital” we also include the indirect (time and human resources) costs related to extra R&D effort needed for the development or improvement of a new green good or service. With respect to bank funding, more than 20% of the SMEs report difficulties in attracting the necessary funding from traditional banks to implement more sustainable measures within the company, to invest in the development of new green goods and services, or to finance the purchase of resource-efficient equipment. From the responses of the sampled SMEs, a picture emerges of the bank as an institution that is inflexible about SMEs’ requirements for occasional delays in repayments. Bankers also appear to have difficulty understanding the commercial potential of the circular economy, especially when it comes to testing or starting production of green innovative products that are currently not available on the market. The analysis of the sample therefore shows that despite efforts at European, national, and/or local levels to provide financial support to businesses for green innovation, the lack thereof is still considered a barrier by many SMEs.

A quarter of the sampled SMEs report the lack of government support as a main barrier towards the circular economy, referring to a lack of effective legislation as well as lack of support from local authorities.

The administrative burden and lack of technical know-how are mentioned by around one in five SMEs (21%). The former barrier includes complex systems and long procedures that businesses face to obtain certifications and labels, as well as to meet standards and legal obligations. The latter barrier includes a gap in employee skills and lack of knowledgeable people in matters related to circular economy business practices. Lack of information and company environmental culture were two other barriers mentioned by 13% and 8% of SMEs, respectively.

Beyond the abovementioned categories, SMEs note a number of additional barriers, including the absence of a reference point to which SMEs can turn for support, the economic sector in which the SME operates being extremely conservative and reluctant to make the “green” transition, as well as the existence of exogenous factors such as the economic downturn, which dampened interest in green business initiatives. These additional barriers are referred to in Figure 3 below as “other barriers”.

Figure 3.

Percentage of SMEs mentioning the barrier (% of all SMEs).

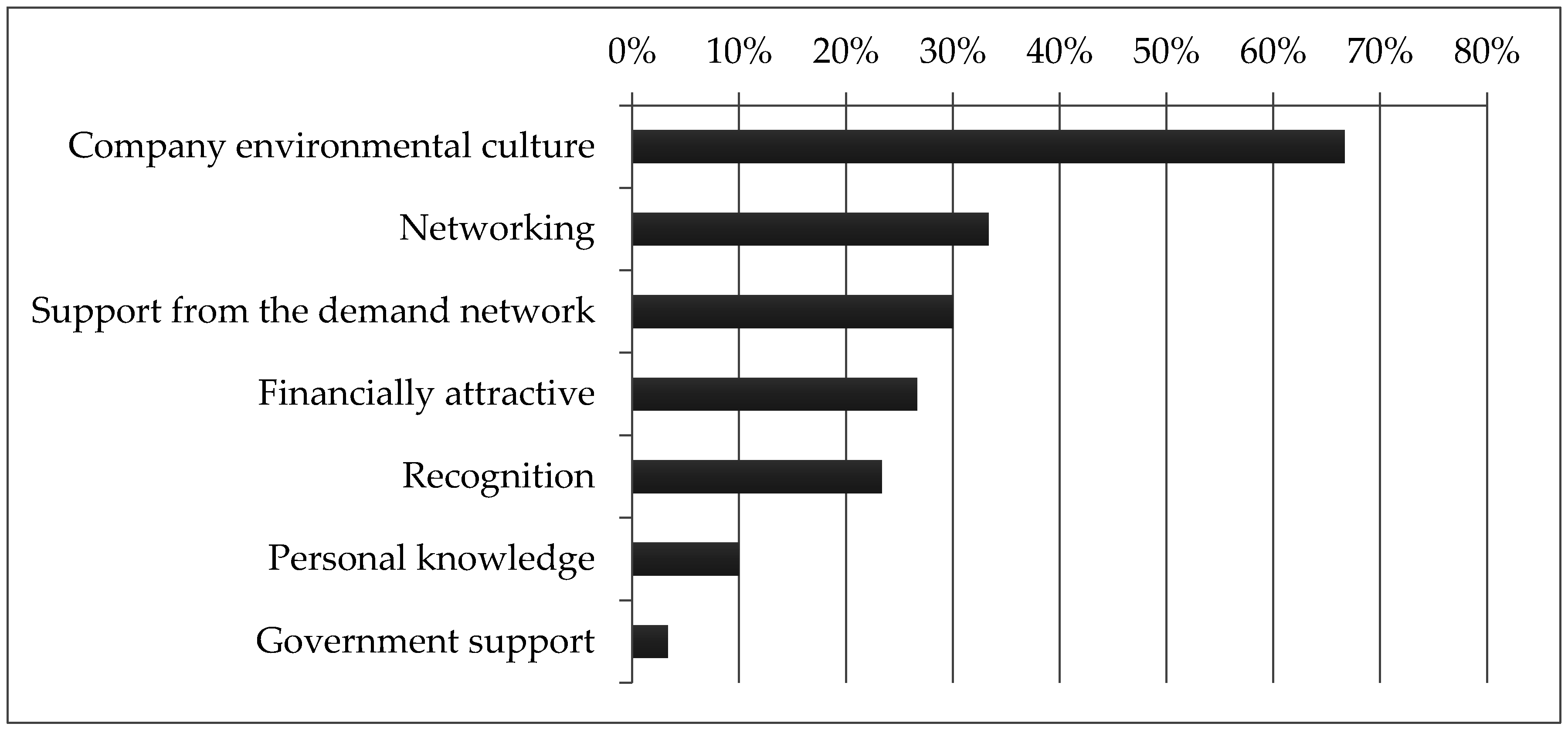

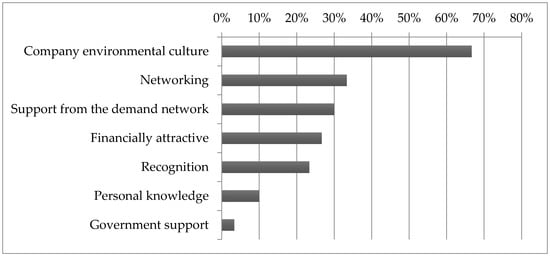

3.2.3. Enablers

As shown in Figure 4, the most frequently mentioned enabler is the company culture of the staff and manager. The majority of these SMEs state that the mindset and commitment of the staff is an important aspect to ease the transition to a circular economy model. It is mentioned that for newly founded start-up companies it is relatively easy to adopt circular economy principles, as their company culture develops from scratch, which can be easier than changing practices in existing firms.

Figure 4.

Percentage of SMEs mentioning the enabler (% of all SMEs).

Networking, in the broadest sense, is mentioned as an enabler by a third of the SMEs. In many cases, this involves joining a group of like-minded SMEs striving for sustainability, or membership of a supply chain partnership. A similar number of SMEs mention that their customers need or prefer “green” products or services, which motivates their adoption of a circular business model. This enabler is shown in Figure 4 as “support from the demand network”.

About a quarter of case studies (27%) demonstrate the importance of a financially attractive green business model. Green technology providers refer, in this respect, to special funds that are available for businesses wishing to implement a circular solution, such as specific start-up financing or local grants. Financial attractiveness is engendered by the relatively low risk of the investment, especially in the case of SMEs adopting solar photovoltaics. Another enabler, also mentioned by around one quarter of the SMEs (23%), is the external recognition of a green business model, such as an award, prize, or favourable treatment in government project tender procedures (when sustainability is a criterion for tendering).

A smaller number of SMEs in the sample mention know-how of individuals within the company as an enabling factor (10%). Finally, only one SME in the sample mentioned (non-financial) support by the (local) government as enabler. Considering that 25% of the sampled SMEs identify the lack of government support as a barrier, it can be concluded that some SMEs in the sample do not see the government as being particularly helpful with regard to circular economy transition.

4. Discussion

The case study analysis has enabled us to learn whether and to what extent the barriers identified from the literature review in Section 2 have been experienced by the SMEs included in the sample. While in the literature review barriers were identified and discussed individually, our analysis has provided insights into how frequently barriers have been identified in our case studies compared to other barriers. Obviously, as explained elsewhere in this paper, frequency does not necessarily imply significance and since our case study analysis has not weighted the barriers, we cannot claim that one barrier has been more significant than others. As a consequence, we cannot claim that the most frequently mentioned barrier is by definition the most important. Nevertheless, an analysis of the frequency of barriers mentioned is an indication of how often SMEs feel themselves to be confronted by a barrier, which could be considered, with the above caveat in mind, a token of the significance of a barrier from the perspective of the SMEs in our sample.

In general, it could be concluded that the barriers mentioned in the literature also apply to a number of the SMEs in the sample. For example, a lack of capital, especially, is seen as a key barrier for smaller companies [27,28]. About 50% of the SMEs in the sample mentioned this barrier, with one of them stating: “Because of our low turnovers, banks have always been hesitant in releasing funding to the business. It has been very challenging to secure a sufficient amount of funds to run our core business, let alone for greening the business.”

The administrative burden when attempting to switch to a circular economy business model, mentioned in the literature as a barrier to SMEs, has also been experienced by a few of the SMEs in our sample, with one of them mentioning the “slow and bureaucratic industry standards approvals process.” The complexity of administrative aspects throughout the supply chain has not been the specific focus of the analysis, but, as one of the SMEs explained: “Traceability (of inputs) across the whole supply chain is often difficult. Also, the different legal frameworks across countries add an additional layer of complexity to identifying the origin of inputs.”

Another barrier mentioned in the case study analysis is the lack of support from SMEs’ supply and demand networks (value chain). This confirms the finding in the literature review that SMEs have low bargaining power in their supply chain; in our sample SMEs appear to feel “locked in” at the bottom of their supply chain and do not have the capacity or “power” to fully implement a circular solution by themselves.

The literature review also identified the lack of technical and technological know-how within SMEs as a common barrier. As a consequence, the adoption of new technologies (e.g., those relevant to circular economy business models) by SMEs is either not considered or rather limited, which hampers the overall diffusion of these technologies on the market. Our case study analysis confirms that in some situations SMEs want to improve the environmental performance of their business operations but they are hampered by this barrier. In our sample, the lack of technical know-how is not considered as a stand-alone barrier in most cases as it is closely connected to SMEs’ lack of resources and time to acquire skills training. Neither do they have the financial means to hire external experts. As a result, a new technology needs to be operated with existing staff and knowledge and, if that is insufficient, then the technology will not be adopted.

One difference between the findings in the literature review and the conclusions from the SME case study analysis is the barrier of company environmental culture (management and staff), which in the literature review is identified as one of the main barriers. In our case study sample this barrier was among the least-often mentioned. A plausible explanation for this observation could be that the SMEs analysed in our sample had already adopted a circular-economy type of business so it is more likely that their company culture was more receptive to a sustainable business model. Interestingly, the reluctance among SME business leaders to change to new business models, as mentioned in the literature, was not specifically mentioned by SMEs in the sample. However, in several cases a lack of time to investigate the possibilities was noted. Although this ‘lack of time’ on the one hand refers to a lack of resources, it may also be due to a reluctance to change, and therefore an unwillingness to invest time in looking for green solutions.

Similarly, while a lack of information about the benefits of the circular economy is seen as a barrier to the implementation of circular economy business models in the literature, either due to the unfamiliarity of the term “circular economy” [44] or due to the non-existent exchange of information among companies [36,45], only a few of the SMEs in the sample experienced this barrier. The reason for this is probably that the sample includes only SMEs that have already implemented a circular economy business model and would therefore not have been hampered by a lack of information. The SME experience described by the publications in our literature review is wider as it also contains examples of SMEs that have not decided to adopt circular business models, and for whom a lack of information about benefits could well have been a barrier.

The lack of government support and effective legislation is a commonly cited barrier in the literature. On the one hand, SMEs find it more difficult to comply with environmental legislation than do large businesses, and there is a lack of knowledge about the specific environmental legislation that affects them [35]. On the other hand, legislation may also cause uncertainty about what a company needs to do to comply with it [36,37,38]. A quarter (25%) of the SMEs in the sample mentioned this barrier. It is notable that the sampled SMEs that experience a lack of government support seem to be more uncertain about unexpected changes and the consistency of policies. One SME mentioned a sudden change in a subsidy scheme, for example; another SME cited uncertainty about policies that have an imminent fixed end-date, while there was no certainty about follow-up policies. Like the barriers discussed above, a company that has created or that enjoys favourable conditions for aligning its business operation with a circular business model may need to rely less on government assistance to develop a suitable framework.

The above discussion shows how barriers are recorded from a general sample of SMEs (both those that have already switched to a circular business model and those that have not) can differ from those identified in a sample of circular-business SMEs. Our discussion has shown that the latter SMEs perceive barriers differently from a group of SMEs that have not adopted a circular business model. For example, a progressive SME owner, with knowledge of circular technologies, is likely to pursue a circular business model and see this transition as an opportunity rather than as a barrier. Such an SME may not be hampered by a lack of government support that might affect other SMEs. Several papers in the current literature have attempted to investigate the issue of barriers to circular economy transition but have mostly done so by focusing on specific sectors (see, for example, [18,19,70]) and/or in specific geographic areas (see [16,17,70]). Yet, while these studies seem to corroborate and complement our findings, our study offers a cross-sectoral study of barriers for a large macro geographic, multi-state region. In other words, our paper attempts to break new ground for academic research in terms of the identification of barrier commonalities, i.e., identification and ranking of those barriers that are common across sectors and regions and hence are specifically related to circular economy transition. As such, our analysis of barriers seems to constitute a framework for investigating ways of addressing such barriers.

Alongside barriers, it is thus important to focus on enablers for adopting a circular business model. The sample findings in this paper on enablers make it clear that despite the existence of barriers, there are effective ways around them. The case studies analysed for this paper show that a range of enablers can be applied to clear barriers and/or create a favourable business environment towards a circular business model. Our sample findings have shown, for example, that from a management point of view an important enabler is company leadership that goes beyond pure everyday management and that considers a circular business model to be more effective and efficient in the longer run. This can be enhanced by capacity development, skills building, and leadership training focused on SME management and leadership. Moreover, our case studies have made it clear that participation in communities of practice can support the successful implementation of circular business solutions.

While research into barriers is evolving rapidly, there seems to be a gap in the investigation of the design of SME specific enablers. Based on a few extant examples from the GreenEcoNet platform, this paper has identified a number of enablers to support SMEs in adopting circular business models, including the frequency of citation as a token of significance. Importantly, there seems to be a gap in the robust design of SME-centred communities of practice based on social learning theory, and in the development of capacity-building schemes, with a strong focus on SME needs and requirements. The few extant examples in this paper need to be corroborated and validated by additional research and testing.

5. Conclusions

This paper has analysed the barriers and enabling factors identified by SMEs during the implementation of their circular economy business model. For this analysis, the SMEs were selected from the GreenEcoNet platform, using a restrictive set of criteria in order to make the conclusions relevant for “circular economy” initiatives. The insights gained are particularly relevant for policy-makers at the EU and national level when devising circular economy policy frameworks for SMEs. Similarly, and as highlighted in the discussion, the insights gained during the research for this paper appear to break new ground and open up interesting research opportunities around the identification of barrier commonalities, i.e., of the identification and ranking of those barriers that are common across sectors and regions, and their specificities, i.e., those that are either sectorially or geographically specific. As such, it may open the way to a better academic understanding of the mechanisms underlying barriers and the resistance to the uptake and propagation of the circular economy, and of better ways to address and lower these barriers.

This research indicates that despite the various policy instruments available to facilitate the “green” SME transition, several barriers to such a transition exist. Most SMEs in the case studies mention “lack of support from their supply and demand network” and “lack of capital” as barriers to “going green”. The first barrier illustrates that SMEs usually operate as small actors in wider value (market) chains and therefore depend on how other “green” actors in the chain are or want to be. The second barrier highlights the fact that SMEs do not often have the financial capacity to manage the disruptive transition to a circular business model.

The paper also indicates several enabling factors that could provide additional information to policy-makers on how to support SMEs. Specifically, the results of this research demonstrate that the success of SMEs in transitioning to a circular business model depends on how well this process is supported by: a company culture with a “green” mindset on the part of the staff and manager; a local or regional network with other SMEs and supporting multipliers to enhance information sharing and awareness raising; and the benefits of having a “green” image and being recognised as a “green” supplier by customers.

While acknowledging that EU and member states support green SME initiatives through funding, training, and other incentives, this paper suggests that a wider range of enablers are required to enhance the attractiveness of green SME business. It is therefore recommended that European and national policies strengthen their focus on greening consumer preferences, market value chains, and company cultures, and support the recognition of SMEs’ circular business models. The implementation of a wider policy focus can be supported by the creation of dedicated marketplaces and communities of practice, such as GreenEcoNet.

Acknowledgments

The research carried out for this paper has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development, and demonstration under grant agreement No. 603939, GREENECONET project. The open access cost (OA) is covered by EC FP7 post-grant OA publishing funds. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. The views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Author Contributions

Vasileios Rizos conceptualised this paper and designed the research plan. Anastasia Ioannou performed the literature review. Terri Kafyeke, Erwin Hofman, and Roberto Rinaldi analysed the SME case studies included in the sample. Wytze van der Gaast and Corrado Topi contributed to the development of the discussion section and the policy conclusions. Arno Behrens and Alexandros Flamos provided advice throughout the process and revised the manuscript. Sotiris Papadelis contributed to the preparation of the methodology. Martin Hirschnitz-Garbers examined the economic benefits of the circular economy. All authors approved the final version of the paper. Furthermore, all authors were involved in the GreenEcoNet EU-funded project and contributed to the design and set-up of the GreenEcoNet online platform, the collection of case studies to be included in the platform and the dissemination of the project outcomes. The platform is the source of the case studies that were analysed for this paper. It should be acknowledged that the following organisations were partners in the GreenEcoNet project: CEPS (Centre for European Policy Studies), the University of York—Stockholm Environment Institute, University of Piraeus (UNIPI), the Ecologic Institute, JIN Climate and Sustainability, and the Green Economy Coalition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy. Opportunities for the Consumer Goods Sector; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, F. A Global Redesign? Shaping the Circular Economy; Chatham House: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, J.M. Squaring the Circular Economy: The Role of Recycling Within a Hierarchy of Material Management Strategies. In Handbook of Recycling State-of-the-Art for Practitioners, Analysts, and Scientists, 1st ed.; Worrel, E., Reuter, M.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 445–477. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, K. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. In Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy; Jarrett, H., Ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1966; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, M.; Leeuw, B.; Fehr, E.; Wong, A. Circular Economy. Improving the Management of Natural Resources; Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences: Bern, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Delivering the Circular Economy. A Toolkit for Policymakers; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EEA (European Environment Agency). Circular Economy in Europe—Developing the Knowledge Base; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation; SUN; McKinsey Center for Business and Environment. Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum; Ellen MacArthur Foundation; McKinsey & Company. Towards the Circular Economy: Accelerating the Scale-Up across Global Supply Chains; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J.; Mitchell, P. Employment and the Circular Economy. Job Creation in a More Resource Efficient Britain; Green Alliance: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bastein, T.; Roelofs, E.; Rietveld, E.; Hoogendoorn, A. Opportunities for a Circular Economy in the Netherlands; TNO: Delft, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Hirschnitz Garbers, M.; Ioannou, A. The Circular Economy: Barriers and Opportunities for SMEs; CEPS: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Minimizing Regulatory Burden for SMEs. Adapting EU Regulation to the Needs of Mico-Enterprises; COM (2011) 803 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Flash Eurobarometer 381—SMEs, Resource Efficiency and Green Markets; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hillary, R.; Burr, P. An Evidence-Based Study into the Benefits of EMSs for SMEs; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2011.

- Liu, Y.; Bai, Y. An exploration of firms’ awareness and behavior of developing circular economy: An empirical research in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 87, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Viñé, M.B.; Gómez-Navarro, T.; Capuz-Rizo, S.F. Eco-efficiency in the SME of Venezuela. Current status and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, S.; Haleem, A. Barriers to implement green supply chain management in automobile industry using interpretive structural modeling technique: An Indian perspective. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2011, 4, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.W.; Hon, A.H.Y.; Chan, W.; Okumus, F. What drives employees’ intentions to implement green practices in hotels? The role of knowledge, awareness, concern and ecological behaviour. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, J.; Fraser, E.D.G. Local Authorities, Climate Change and Small and Medium Enterprises: Identifying Effective Policy Instruments to Reduce Energy Use and Carbon Emissions. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2007, 15, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekoninck, E.A.; Domingo, L.; O’Hare, A.J.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Reyes, T.; Troussier, N. Defining the challenges for ecodesign implementation in companies: Development and consolidation of a framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, L.; Wurpel, G.; Ten Wolde, E. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy; IMSA Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Besch, K. Product-service systems for office furniture: Barriers and opportunities on the European market. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S. Resistance to change: Developing an individual differences measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trianni, A.; Cango, E. Dealing with barriers to energy efficiency and SMEs: Some empirical evidences. Energy 2012, 37, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervojeda, K.; Verzijl, D.; Rouwmaat, E.; Probst, L.; Frideres, L. Clean Technologies, Circular Supply Chains, Business Innovation Observatory; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oakdene Hollins. The Further Benefits of Business Resource Efficiency; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2011.

- Rademaekers, K.; Asaad, S.S.Z.; Berg, J. Study on the Competitiveness of the European Companies and Resource Efficiency; ECORYS: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.-J.; Wimmer, R. Product service systems as systemic cures for obese consumption and production. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O. Drivers and barriers for shifting towards more service-oriented businesses: Analysis of the PSS field and contributions from Sweden. J. Sustain. Prod. Des. 2002, 2, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoevenagel, R.; Brummelkamp, G.; Peytcheva, A.; van der Horst, R. Promoting Environmental Technologies in SMEs: Barriers and Measures; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S.; Tunçer, B. Greening SMEs by Enabling Access to Finance. Strategies and Experiences from the Switch-Asia Programme. Scaling-Up Study 2013; Switch-Asia Network Facility: Wuppertal, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hyz, A.B. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Greece—Barriers in Access to Banking Services. An Empirical Investigation. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2011, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.M.; Redmond, J.; Simpson, M. A review of interventions to encourage SMEs to make environmental improvements. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2009, 27, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogirou, C.; Sørensen, S.Y.; Larsen, P.B.; Alexopoulou, S. SMEs and the Environment in the European Union; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buren, N.; Demmers, M.; van der Heijden, R.; Witlox, F. Towards a Circular Economy: The Role of Dutch Logistics Industries and Governments. Sustainability 2016, 8, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilts, H.; von Gries, N.; Bahn-Walkowiak, B. From Waste Management to Resource Efficiency—The Need for Policy Mixes. Sustainability 2016, 8, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanner, R.; Bicket, M.; Withana, S.; ten Brink, P.; Razzini, P.; van Dijl, E.; Watkins, E.; Hestin, M.; Tan, A.; Guilcher, S.; Hudson, C. Scoping Study to Identify Potential Circular Economy Actions, Priority Sectors, Material Flows & Value Chain; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Doberstein, B. Developing the circular economy in China: Challenges and opportunities for achieving “leapfrog development”. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World 2008, 15, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Helms, M.M.; Hervani, A.A. Reverse logistics and social sustainability. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.; Williander, M. Circular Business Model Innovation: Inherent Uncertainties. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMEC Environment & Infrastructure; Bio Intelligence Service. The Opportunities to Business of Improving Resource Efficiency; AMEC Environment & Infrastructure: Northwich, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo-Luna, J.L.; Garcés-Ayerbe, C.; Rivera-Torres, P. Barriers to the adoption of proactive environmental strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUSION. Fusion Observatory Report: February 2014—The Circular Economy and Europe's Small and Medium Sized Businesses; BSK-CiC: Chatham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eijk, F. Barriers & Drivers towards a Circular Economy. Literature Review; A-140315-R-Final; Accelerations: Naarden, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, D.; Molina, A. Collaborative networked organisations and customer communities: Value co-creation and co-innovation in the networking era. Prod. Plan. Control. 2011, 22, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlikad, A.K.; Mcfarlane, D.; Fleisch, E.; Gross, S. The Role of Product Identity in End-of-Life Decision Making; Auto-ID Center: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Regulatory Policy and the Road to Sustainable Growth; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Geng, Y. Drivers and barriers of extended supply chain practices for energy saving and emission reduction among Chinese manufacturers. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin, N.; Madden, B.; Sharpe, S.; Benn, S.; Agarwal, R.; Perey, R.; Giurco, D. Shifting Business Models for a Circular Economy: Metals Management for Multi-Product-Use Cycles; UTS: Sydney, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WBCSD (World Business Council for Sustainable Development). A Vision for Sustainable Consumption. Innovation, Collaboration, and the Management of Choice; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsson, O.; Tell, J. Barriers to Business Model Innovation in Swedish Agriculture. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1957–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meqdadi, O.; Johnsenb, T.; Johnsenc, R. The Role of SME Suppliers in Implementing Sustainability. In Proceedings of the IPSERA 2012 Conference, Napoli, Italy, 1–4 April 2012.

- Wooi, G.C.; Zailani, S. Green Supply Chain Initiatives: Investigation on the Barriers in the Context of SMEs in Malaysia. Int. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.-H.; Geng, Y. The role of organizational size in the adoption of green supply chain management practices in China. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wycherley, I. Greening supply chains: The case of the body shop international. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 1999, 8, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edbring, E.G.; Lehner, M.; Mont, O. Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: motivations and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planing, P. Business Model Innovation in a Circular Economy. Reasons for Non-Acceptance of Circular Business Models. Open J. Bus. Model Innov. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar]

- GreenEcoNet. Connecting SMEs for a Green Economy. Available online: http://www.greeneconet.eu (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Flamos, A.; Ioannou, A.; Papadelis, S. Taxonomy for the Green Economy Landscape; Deliverable: D1.1; University of Piraeus Research Centre: Piraeus, Greece, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rozman Cafuta, M. Open Space Evaluation Methodology and Three Dimensional Evaluation Model as a Base for Sustainable Development Tracking. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13690–13712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; European Commission; International Monetary Fund; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; World Bank. Handbook of National Accounting—Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting 2003; United Nations: New York City, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin, L.; Jamsin, E.; Raksit, A. Wales and the Circular Economy. Favourable System Conditions and Economic Opportunities; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Bi, J.; Moriguichi, Y. The Circular Economy. A New Development Strategy in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 2006, 10, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre (JRC). Science for a Circular Economy—Some JRC Examples; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy; COM (2015) 614 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Riisgaard, H.; Mosgaard, M.; Zacho, K.O. Local Circles in a Circular Economy—The Case of Smartphone Repair in Denmark. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 5, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).