1. Introduction

For centuries the Istanbul Strait has been an important link between the Black Sea, which is a closed sea, and the rest of the world. It is one of the seaways with the most intense maritime traffic in the world [

1]. Moreover, it presents significant navigational challenges due to its geographic and oceanographic characteristics. It is approximately 31 km long, with an average width of 1500 m. It has several sharp turns requiring that ships alter course at least 12 times to safety navigate through it. At its narrowest point, which measures only 700 m, the current can reach 7–8 knots and a 45 degree course alteration is required, while at some sections the necessary course alteration reaches 80 degrees [

2]. In addition to these factors, there is another factor making navigation hazardous: that is the intense volume of local maritime traffic. On a daily basis, many passenger boats, passenger and car ferries, and sea buses traverse the Strait [

3]. Therefore, maritime shipping poses a particularly high risk to the region. Additionally, substandard ships increase the risk and threaten not only the marine environment but also life in this region. Over the years, serious accidents causing environmental disasters, such as those involving the

Independenta, the

Nassia, and

Volganeft-248, have taken place in this region [

4,

5,

6]. These causalities resulted in the loss of lives as well as caused significant amounts of oil to spill into the sea and the burning of oil causing air pollution. The

Independenta accident resulted in the spillage of around 65,000 tons of crude oil into the Strait, and is one of the worst oil spills on record [

4].

According to records of the Turkish Coastal Safety and Salvage, there have been several maritime incidents, such as grounding, contact, collusion, and fire [

7]. These include the frequent occurrence of ships ramming into seaside buildings or contact with local maritime vessels and fishing boats due to engine failure or navigation failure.

The 1994 Turkish Maritime Traffic Regulations were revised with the 1998 modified regulations after being adopted by the IMO and in 2004, the Vessel Traffic Services (VTS) were established to provide maritime safety in the region. These regulations, together with the establishment of the VTS, have decreased the number of collision-related accidents, but they have not had any effect on other types of accidents [

8]. There are various international rules and recommendations in order to reduce the risks arising from maritime transportation on the world’s seas, as well as to provide maritime safety and protect the marine environment which are regulated by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), such as the convention for the safety of life at sea (SOLAS), the international convention for the prevention of pollution from ships (MARPOL), and the convention of the international regulations for preventing collisions at sea (COLREG). The primary responsibility for the implementation and enforcement of these regulations for all ships flying their flags lies with the flag states [

9]. Classification societies perform, statutorily, surveys and related activities on behalf of flag states by authorization of a flag state. Classification societies play an important role in the case of certain states, such as open registers (Flags of Convenience—FOCs), which do not have the resources or personnel needed to carry out the inspections [

10,

11]. Additionally, Port States have the right to inspect a foreign-flagged ship coming into their port to ensure that the ship meets the requirements of international regulations, which is described as Port State Control (PSC). If a ship cannot comply with the standards required by the relevant conventions, the IMO Standards, it is called a substandard ship. PSC is often accepted as a measure to consolidate the former maritime safety net constructed by flag states and classifications societies; that is, the last safety net [

12]. It was due to a problem that PSC originally emerged. Many flag states were unable to adequately perform their mandated duties of ensuring that ships flying their flags complied with the IMO standards. This was especially the case with FOCs which were forced to do this because a ship flying with an open register flag rarely visit its ports of registry in its service life and additional costs are required for control mechanisms [

13]. After a series of tanker accidents in the 1970s, the control mechanism used by flag states and classification societies were deemed as ineffective in eradicating all substandard ships from the seas and the PSC emerged to assist in the enforcement of the procedures relating to international conventions [

9,

14].

Regional agreements on the PSC (Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control—MOU) have been created in order to develop an effective and sustainable inspection mechanism by balancing the demand for ports in the same region, exchanging information on ships inspected, unifying the standards for inspection and detention and the training of officers conducting inspections under the PSC [

15,

16]. The first regional agreement was the Paris MOU which includes Europe and the North Atlantic region. Since then, another eight regional agreements have been established and are, respectively, the Acuerdo de Vina del Mar Agreement, the Tokyo MOU, the Caribbean MOU, the Mediterranean MOU, the Indian Ocean MOU, the Abuja MOU, the Black Sea MOU, and the Riyadh MOU. In addition to these regional agreements, the USA conducts PSC over its territorial waters [

15,

16,

17].

Despite the fact that all regional PSC regimes are the same, there are differences in their implementation, such as the evaluation of performance of flag states and selecting priority ships for inspection [

15]. Moreover, each port in the same regime does not carry out the inspections with the same strictness due to geographic and cultural differences; therefore, the average detention and deficiency rates may be different from one to another [

18]. The largest and most stringent inspections are made in the Paris MOU and the Tokyo MOU with leader memorandums [

15]. According to research by Li and Zheng, the Paris MOU and the Tokyo MOU have the most efficient ship selecting methods [

12]. The Paris and Tokyo MOUs use “The Black, Grey and White List” (BGW list) of flag states as one of the parameters for determining a ship’s risk profile. The BGW list which represents the performances of flag states is generated based on the statistics of inspections and detentions conducted during the previous three years. From time to time, amendments are necessary by PSC regimes in order to improve the effectiveness of inspections and to ensure sustainability.

Several academic studies based on detentions and deficiencies detected in the various regional MOUs have been carried out to determine the effect of the PSC on maritime safety, taking into account various parameters such as ship age, ship type, recognizing organizations and flag states. These studies have concluded that the PSC has been successful in reducing risk and in raising the maritime safety level [

12,

13,

14,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The PSC mechanism is regarded as one of the most important tools to ensure maritime safety.

In this context, although the risks arising from maritime shipping cannot be completely eliminated due to the aforementioned characteristics of the Istanbul Strait, they may be reduced and the safety of navigation in this region may be improved by means of PSC inspections. The Black Sea MOU inspections are of special importance for maritime safety in this region because ships passing through this region, which visit a seaport of the Black Sea, are inspected in the Black Sea MOU. At the same time, these inspections are an important indicator of maritime safety in this region because these inspections directly reflect the performance of flag states passing through this region.

In this study, for the assessment of risks arising from maritime transportation in the Istanbul Strait, the risk level of passing flag states from this region has been taken into consideration. Firstly, in order to evaluate the performance of flag states, the Black Sea BGW lists are generated, as is the case with those of the Paris MOU and the Tokyo MOU. Secondly, in order to determine the risk level of flag states passing through the Istanbul Strait, the weighted point method, which includes the criteria of the BGW list, deficiency index level, casualty index level, and passing index level, is used.

2. Literature Review

Various studies on the casualty rates of flag states and the relationship between PSC inspections and flag states’ related risk have been carried out. In these studies the risks arising from maritime transportation are evaluated based on flag state data on PSC and the casualty rate of ships from flag states like this study. Li and Wonham investigated total loss statistics from 1977 to 1996 and analyzed the world fleet, dividing it into groups according to the total accidental loss rate. They concluded that the total loss rate had declining for this period due to the implementation of safety measures and confirmed that open registers (FOCs) had the worst safety record, generally [

24]. Alderton and Winchester examined the casualty record of flag states for the years 1997–1999 by comparing the average casualty rates of flag states according to the types of register and their findings indicated that FOCs had generally a worst record than national flags [

25]. Li investigated the relationship between the total loss rate of FOCs and Port State Control detentions, and found that there was a high correlation between the loss rate and detention rate and the age of a ship [

26]. Cariou

et al. showed that the main determinants of the number of reported deficiencies were the age of the vessel at inspection, the type of vessel, and the flag of registry [

13]. Knapp and Franses analyzed the effect of PSC inspections on the probability of casualty according to targeting ships, ship types, flag states, classification societies, and detained vessels. One of the conclusions drawn in this study is that black-listed flag states showed a higher probability of a serious casualty compared to the gray- and white-listed flag states [

27]. Robert and Marlow investigated casualties in dry bulk shipping from 1963–1996 and stressed that the risk would increase with ship age and the ship’s flag of registration [

28]. Piniella

et al. studied the influences of PSC policies concerning FOCs using detention and deficiency data of the Paris and Tokyo MOUs and the USCG. As part of this study, the relationship between FOCs fleets and the detection of substandard ships is determined using the detention index and they found that all FOCs have different results in the ranking of the highest detention index [

29]. Degre generated the Black-Gray-White list of categories of vessels according to their observed casualties using similar methods to those of the Black-Grey-White list of the Paris MOU to complement flag state performances [

30].

Furthermore, there are several studies, which take differing angles, based on maritime traffic of the Istanbul Strait and risk assessment. In these studies the risks arising from maritime transportation in the Istanbul Strait are evaluated using various parameters and methods, and the common finding of all these studies is that the Istanbul Strait is a high-risk waterway. Emecen Kara and Okşaş evaluated maritime safety in the Istanbul Strait according to average detention and deficiency rates of flag states passing through it in all regional MOUs [

15]. Using several maritime traffic safety parameters such as traffic flow, traffic volume of local vessel, and probability of collusion Aydoğdu

et al. found that the areas most at risk were at the southern entrance to the Istanbul Strait [

31]. Arslan and Turan investigated maritime casualties in the Istanbul Strait analytically and found various factors causing shipping accidents and the weights of each factor using the SWOT-AHP method [

32]. Or and Kahraman analyzed possible factors contributing to accidents in the Istanbul Strait using Bayesian analysis and simulations modelling. Their results indicated significant increases in the number of accidents in maritime conditions such as higher transit traffic rates, denser local traffic conditions, and adverse weather conditions [

33]. Ulusçu

et al. analyzed safety risks pertaining to the transit vessel maritime traffic in the Istanbul Strait by dividing it into slices incorporating a probabilistic accident risk model into the simulation model. They also investigated the impact of various factors, which included vessel arrivals, scheduling policies, pilotage, overtaking, and local traffic density, on the risk profile of the Strait. Local traffic density and pilotage were found to be two main factors affecting the level of risk [

3]. Contrary to these studies, in this study the risk arising from maritime transportation in the Istanbul Strait are determined based on the performances of flag states on the Black Sea MOU, as well as the number of passing and casualty rates of flag states in this region.

6. Discussion

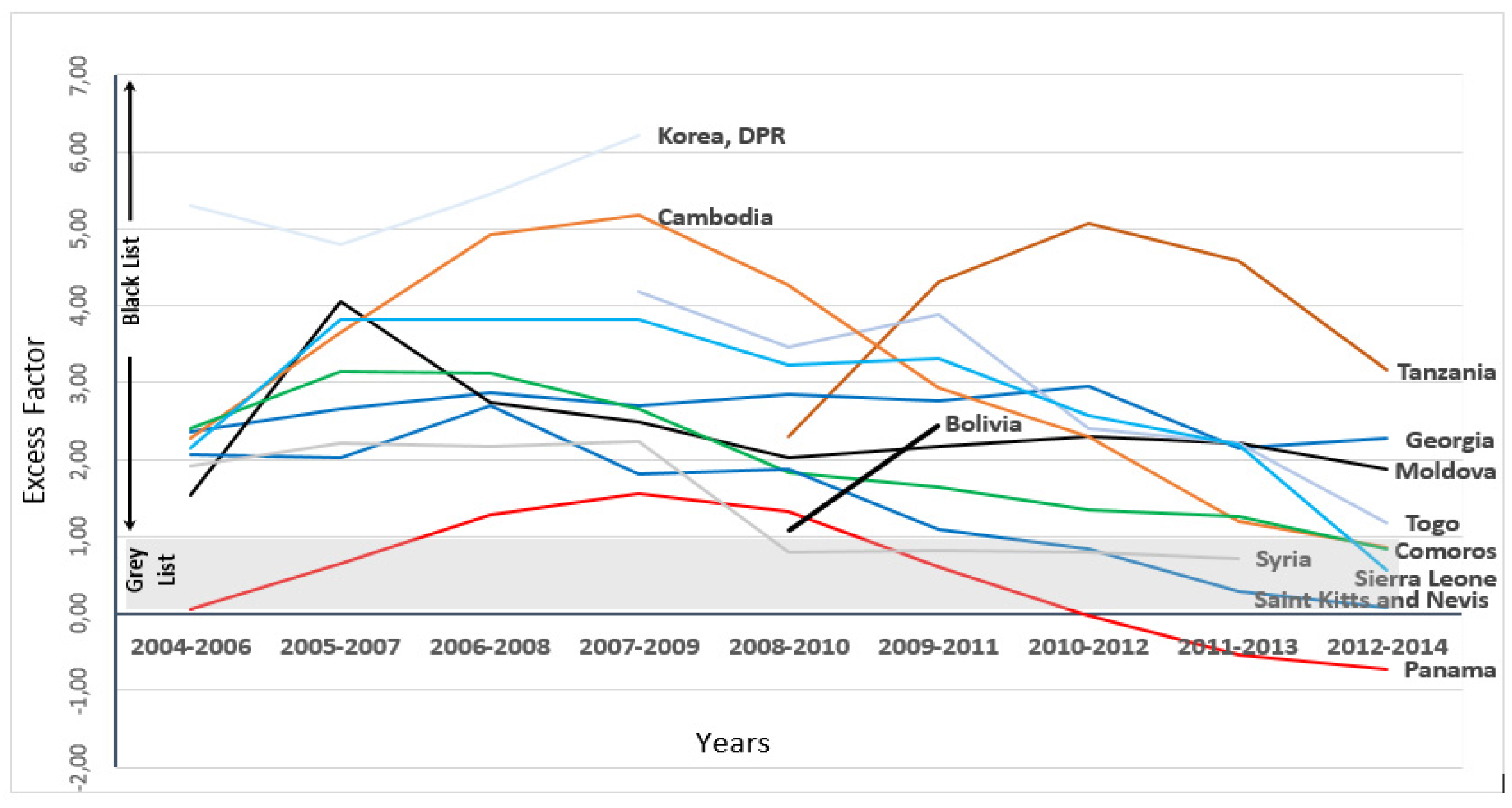

The percentage of inspections with deficiencies in the Black Sea MOU is over 60% and the detention rate has decreased since 2010. According to the BGW lists generated, a decrease can be seen in the flag states risk level from the years 2004 to 2014. The risk level of black-listed flags has shown a declining trend from 2009, except for Tanzania and Bolivia. This result indicates that PCS inspections have been effective in decreasing the risk in the Black Sea Region. The Comoros, Sierra Leone, Cambodia, and Saint Kitts and Nevis have moved from the black list to the grey list over time, and Panama has moved to the white list. Additionally, some flags, such as the DPR of Korea, Bolivia, Dominica, Syria, Mongolia, India, and Azerbaijan have been removed from the BGW lists over time, because the number of inspection is lower than 30 in the previous three-year period related to the number of ships visiting the Black Sea region seaports. However, this does not mean that these flags have no risk.

Moreover the BGW lists show that there was an overall improvement in the performance of FOCs from 2004 to 2014. In particular, the number of DPR of Korea-flagged ships, which had the highest value of excess factor in the black list from 2004 to 2009, have decreased significantly.

According to the 2014 BGW list, while some FOCs such as Cambodia, the Comoros, Vanuatu, Barbados, Lebanon, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, are in the grey list, and Georgia and Moldova are in the black list. Some others, such as Liberia, Malta, and Panama, which have the highest passing percentage, are in the white list. This demonstrates that there are differences among the performances of FOCs. This finding complies with the findings of Alderton and Winchester, Li and Wonham, and Piniella et al.

Some flags such as Algeria, Bangladesh, Dominica, Egypt, Honduras, Kiribati, Switzerland, Syria and Tuvalu have not been included in the 2014 BGW list, because they have not had 30 or more inspections. However, this does not show that these flags are not at risk, these flag states have a high risk status according to the deficiency index.

Flag states’ performances in the 2014 BGW list are, in general, similar to those in the Paris MOU. Tanzania, Georgia, Moldova, and Togo are black-listed flags in the BGW list of the Black Sea MOU. Tanzania, Moldova, and Togo are also in the black list on the Paris MOU and Tanzania has the highest risk in both the Black Sea MOU and the Paris MOU. However, there are more flag states in the black list of the Paris MOU than the Black Sea MOU. While Sierra Leone, Cambodia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, the Comoros, and the Cook Islands are grey-listed flags in Black Sea MOU, they are black-listed flags in the Paris MOU. Additionally, a surprising result is that Belize, which is a white-listed flag in the Black Sea MOU and Dominica, which is not listed in the Black Sea MOU, are found on the black list of the Paris MOU, and Georgia which is a black-listed flag in the Black Sea MOU is not listed in the Paris MOU.

Flag states’ performances in the 2014 black list of the Black Sea MOU differ from those in the Tokyo MOU significantly, but with the exception of Tanzania. Togo is in the grey list on the Tokyo MOU, and Moldova and Georgia are not listed on the Tokyo MOU. There are 12 flag states in the black list of the Tokyo MOU. Most of these flag states are not listed in the Black Sea MOU due to the fact that the number of inspected ships was lower than 30. While Sierra Leone and Cambodia are black-listed flags in the Tokyo MOU, they are grey-listed flags in the Black Sea MOU. Moreover, Belize, one of black-listed flags in the Tokyo MOU is in the white list of the Black Sea MOU.

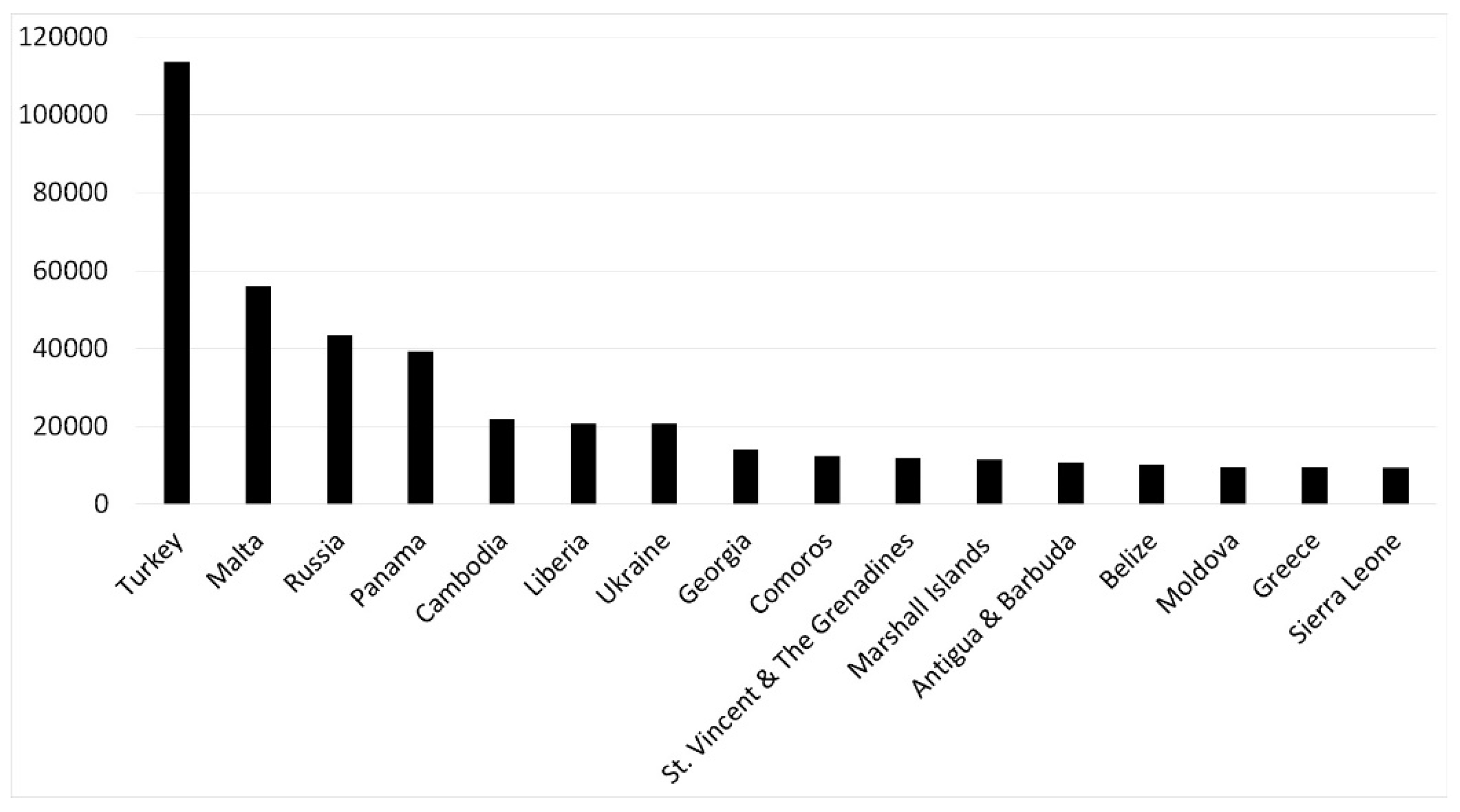

According to the flag state Risk Level of ships passing through the Istanbul Strait, Tanzania, Moldova, Togo, Cambodia, Georgia, Sierra Leone, and Turkey are classified as having high-risk flags. Tanzania, Moldova, Togo, and Georgia are already in the black list. Despite Cambodia and Sierra Leone being in the grey list, they are classified as having a high risk level because they have very high casualty index points. In the same way, despite the fact that Turkey is in the white list, it has a high risk level because it has very high passing percentage points. About 108 different flag states have passed through the Istanbul Strait during this period. 24 of these flag states, which have a passing percentage of 1% or more, constitute 93% of all passing ships. 25% of them have a high risk level, 62.5% of them have a standard risk level, and 12.5% have a low risk level. Another 84 flag states, which have a passing percentage below 1%, constitute 7% of all passing ships. Only one of these, Georgia, has a high risk level. 19% of these flag states have a standard risk level. Algeria, Bangladesh, Dominica, Egypt, Honduras, Kiribati, Switzerland, Syria, and Tuvalu have been included in the ranking of standard risk because these flags have larger deficiency index scores.

Additionally, it has become evident that the risk level of FOCs and national flags are not significantly different from each other in terms of evaluating high risk levels and standard risk levels. However, 16% of flag states with low-risk levels are FOCs. Eight of the top ten flag states in the ranking of passing percentage are FOCs. However, it should be noted that these FOCs generally have a standard risk level, except for Cambodia and Moldova, which are classed as high risk.

Safety of navigation, lifesaving appliances, and fire safety measures were the top deficiency categories in the Black Sea MOU during the period of 2012–2014. Research indicates that most of the casualties in the Strait region occurred due to navigational factors, such as collision or grounding in this period.