Abstract

Despite the growing demand for organic products, research on organic farming (OF) such as genotype screening, fertilizer application and nutrition uptake remains limited. This study focused on comparisons of the apparent recovery efficiency of nitrogen fertilizer (REN) in rice grown under OF and conventional farming (CF). Thirty-two representative conventional Japonica rice varieties were field grown under five different treatments: control check (CK); organic farming with low, medium and high levels of organic fertilizer (LO, MO and HO, respectively); and CF. Comparisons of REN between OF and CF classified the 32 genotypes into four types: high REN under both OF and CF (type-A); high REN under OF and low REN under CF (type-B); low REN under OF and high REN under CF (type-C); and low REN under both OF and CF (type-D). Though the yield and REN of all the rice varieties were higher with CF than with OF, organic N efficient type-A and B were able to maintain relatively high grain yield under OF. Physiological activities in flag leaves of the four types from booting to maturity were subsequently investigated under OF and CF. Under OF, high values of soil and plant analyzer development (SPAD) and N were observed in type-B varieties, while in contrast, both indexes slowly decreased in type-C varieties under CF. Moreover, the decline in N content in type-C and D varieties was greater under OF than CF. The decrease in glutamine synthetase (GS), glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) and glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) activity in flag leaves was smaller under OF than CF in type-A and B varieties, while in contrast, type-C and D varieties showed an opposite trend. The findings suggest that OF slows the decline in key enzymes of N metabolism in organic N-efficient type rice, thus maintaining a relatively high capacity for N uptake and utilization and increasing yield during the late growth period. Accordingly, we were able to screen for varieties of rice with synergistically high REN and high grain yield under OF.

1. Introduction

As a consequence of the negative impacts of conventional farming (CF) on the environment and human health [1,2], organic agriculture is becoming increasingly widespread. Moreover, due to increasing consumer demand and political support, the popularity of organic food is also on the rise [3,4]. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [5], the global organic food market has expanded by 10%–15% in the past 10 years, with conventional markets growing by only 2%–4%. In addition to the safety aspects, organic farming is deemed beneficial to the environment and the biodiversity of a wide range of taxa including birds and mammals, invertebrates and arable flora [6,7]. In China, organic agriculture and the production of organic products was introduced in 1990 [8]. Since then, both the international and domestic market for organic products has continued to grow, with experts predicting huge market potential in the future [9].

During the past three decades, farming practices and management systems have intensified in many rice-producing countries [10,11,12]. Organic rice, as an important organic product, is thought to represent approximately 3 million hm2 and is becoming increasingly popular [8]. However, due to its late start, there is a lack of related research and system technology for organic rice production, especially in terms of variety selection and fertilizer management [13]. Moreover, since nitrogen (N) is among the most important elements in agriculture systems, efficient organic fertilizer application that minimizes negative effects on the environment also needs to be examined. Moll et al. [14] defined nutrient use efficiency (NUE) as being the yield of grain per unit of available N in the soil (including the residual N present in the soil and the fertilizer). This NUE can be divided into two processes: uptake efficiency (the ability of the plant to remove N from the soil as nitrate and ammonium ions) and utilization efficiency (the ability to use N to produce grain yield) [15]. Although high amounts of organic fertilizer can maintain or increase rice yield, there is a risk of non-point source N pollution [16]. Under organic farming (OF), the gradual and continuous application of nutrients differs from that under CF [17]. Moreover, evaluation of yield and NUE in rice is commonly established on the basis of chemical N fertilizer [18], not the conditions of OF. Thus, there is an urgent need for research aimed at a thorough understanding of potential varieties that show high yield, quality and NUE under OF.

Nitrogen is usually available to plants in an inorganic form such as nitrate, nitrite or ammonia. Nitrate is a major source of inorganic nitrogen utilized by higher plants [19]. In Arabidopsis, the process of nitrate assimilation involves the initial uptake of nitrate ions from the soil, followed by reduction to nitrite and then to ammonia. The reduction reactions are catalyzed by the enzymes nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase, respectively. Ammonium ions enter the amino acid pool primarily by way of the action of glutamine synthetase [20]. Generally, in higher plants, there are some key N metabolism enzyme involved in assimilating intracellular ammonium into organic compounds, such as GS, GPT, GOT and so on. Glutamine synthetase (GS; EC 6.3.1.2) is a key enzyme for the assimilation of ammonium into glutamine. Numerous studies of the GS enzyme have emphasized the importance of this enzyme in plant nitrogen metabolism [21]. Leaf glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) and glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) activities, which in the presence of their co-substrates pyruvate and oxaloacetate, convert l-Glutamate into α-ketoglutarate, were determined to gain a better understanding of the nitrogen assimilation response [22]. However, there has been very little study of the influence of organic farming on nitrogen metabolism of rice plants.

In the present study, 32 representative conventional Japonica rice varieties were field-grown under CF and OF in Gaoyou city, Jiangsu Province, East China. The objectives were to screen for genotypes showing high yield and NUE under OF. Subsequently, key enzymes of N metabolism were investigated to determine the biochemical mechanism underlying effective N utilization in OF. The results provide a scientific basis for organic rice cultivation and nutrient management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Thirty-two representative Japonica rice varieties, commonly field-grown in the middle and lower reaches of Yangtze district, were selected (Table 1) and grown by organic farming and conventional farming during the rice growing season (from May to October) of 2013–2014. Two experiments were carried out, one in 2013 and a second one in 2014. In 2013, 32 varieties were screened under CK, CF and OF (including three different dosage of organic fertilizer) (Table 1 and Table 2). In 2014, we repeated the same experiment as 2013, eight rice varieties with synergy and transition of REN were chosen for thorough analysis under CF and medium dosage of OF.

Table 1.

Rice varieties used in this experiment.

Table 2.

Fertilizers applied to rice grown under organic and conventional farming.

Experiments were carried out on an eco-agricultural farm in Gaoyou county, Jiangsu Province, China (32°47′ N, 119°25′ E, 2.1 m altitude). In the farm, half of the planting area had been verified by the China Organic Food Certification Center in 2009, where the organic farming of rice was produced. Conventional farming was carried on the other part of the farm. The farm was under continuous cultivation with green manure (Astragalus sinicus L.)-rice rotation. During the study period of 2013 and 2014, the study site experienced annual mean precipitation of 968 mm and 992 mm, annual mean evaporation of 1118 mm and 1082 mm, an annual mean temperature of 15.0 °C and 14.8 °C, annual total sunshine hours of 2124 h and 2076 h, and a frostless period of 223 day and 217 day, respectively. The soil on the farm is clay with 22.4 g·kg−1 organic matter, 80.8 mg·kg−1 alkali hydrolysable N, 23.3 mg·kg−1 Olsen-P, 105.3 mg·kg−1 exchangeable K, and 1.03 g·kg−1 total N. In both years, seedlings were sown in a seedbed on May 1st then transplanted on 20 May at a hill spacing of 0.30 × 0.15 m with three seedlings per hill.

2.2. Treatments

The study was laid out in a split-plot design with farming system as the main plot and varieties as the split plot factor. Each block was 6 m2, with four replicates per treatment.

A zero N control (control check) was designated as CK to evaluate the background of N supply in soil fertility.

As OF treatments, three rates of organic fertilizer (low, medium and high) were applied (designated LO, MO and HO, respectively). Among the OF treatments, the MO treatment were adopted following the protocols of organic rice produced by the farm. Treatment details are shown in Table 2. Contents of N, phosphorus, potassium, and organic matter in each type of organic fertilizer were as follows. Rapeseed cake fertilizer (a byproduct of rapeseed after pressing oil): 4.60%, 1.03%, 1.21%, and 81.60%, respectively; Sanan organic fertilizer: 4.00%, 0.84%, 1.16%, and 45.00%, respectively (confirmed by measuring); and clover grass manure: 0.33%, 0.03%, 0.19%, and 0.21%, respectively. Sanan organic fertilizer, which has been certified as a biological organic fertilizer [23], was supplied by Beijing Sanan Agricultural Science and Technology Corporation (Beijing, China). The average fresh weight yield of clover grass was 12,000 kg·ha−1. Grass manure was plowed into the soil 15 days before cultivation as a basal fertilizer then rapeseed cake and specified Sanan organic fertilizer were applied evenly one day before transplanting. In early August, Sanan organic fertilizer was reapplied as top-dressing. All the OF treatments involving organic manure were managed according to the standards for organic rice cultivation, and weeds were controlled by hand weeding [9].

As CF treatments, it followed local high-yield agricultural management practices (Table 2). Nutrients were delivered throng chemical fertilizer (i.e., Urea as a source of N, P2O5 as a source of P and K2O as a source of K). Water, insects, and disease were controlled as required to avoid yield losses, and weeds were controlled with chemical herbicide treatment.

2.3. Plant Sampling and Measurements

Plants were hand-harvested on 25 October 2013, and 26 October 2014. Measurements of grain yield and yield components followed the procedures described in Yoshida et al. [24]. Plants in the two rows on each side of the plot were discarded to avoid border effects. Grain yield in each plot was thereby determined from a harvested area of 2.0 m2 and adjusted to a 14% moisture content.

Above-ground biomass and yield components; that is, the number of panicles per square meter, number of spikelets per panicle, percentage of filled grains and grain weight, were determined in a 1 m2 area (excluding borders) sampled randomly in each plot. The percentage of filled grains was defined as the number of filled grains expressed as a percentage of the total number of spikelets. The dry weight of each component was determined by oven-drying at 70 °C to a constant weight prior to weighing [25].

Tissue N content was determined by micro Kjeldahl digestion, distillation and titration to calculate aboveground N uptake [24]. The apparent recovery efficiency of N fertilizer (REN; the percentage of N fertilizer recovered in aboveground plant biomass at the end of the cropping season) was determined according to Zhang et al. [26]. In this paper, we chose the REN as the variable to estimate NUE.

A chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502) was used to determine soil and plant analyzer development (SPAD) values in flag leaves of 10 randomly selected plants of each variety. Average values of upper, middle and bottom portions of each flag leaf were determined. For soluble protein analysis, three biological replicated roots, rice leaves under different treatments were harvested at each growth stage.

Glutamine synthetase (GS), glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) and glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) activities in leaves were measured at booting, heading, middle-filling, late-filling and maturity. The activity of GS was measured with the biosynthetic reaction assay, using NH2OH as artificial substrate, by measuring the formation of glutamyl hydroxamate. Leaf GS activity was measured in pre-incubated assay buffer (37 °C) consisting of 70 mm MOPS (pH 6.80), 100 mm Glu, 50 mm MgSO4, 15 mm NH2OH, and 15 mm ATP. The reaction was terminated after 30 min at 37 °C by addition of an acidic FeCl3 solution (88 mm FeCl3, 670 mm HCl, and 200 mm trichloroacetic acid) at booting, heading, middle-filling, late-filling and maturity. One unit (U) of activity was defined as the increase in glutamylhydroxamate per g protein per hour [21]. Glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) and glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) activity were assayed by the method of Wu et al. [27]; one unit (U) of activities was defined as the increase in pyruvic acid content per g protein per hour.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance was performed using the SAS/STAT statistical analysis package (version 6.12, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data from each sampling date were analyzed separately. Four replicates were used to calculate the means. Differences between means were tested by least significant difference test at the 0.05 level of probability. For the mean comparisons, the Tukey test was the chosen method. Unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic means (UPGMA) of agglomeration method were used for the hierarchical clustering. Hierarchical cluster analysis was applied in the present work. After determining the Euclidean distance and sum of squared residuals, the dendrogram was built. Accordingly, the varieties were classified into three types as low, medium and high NUE under different farming systems respectively [28].

3. Results

3.1. Effects of OF and CF on REN

3.1.1. Statistical Analysis of REN under OF and CF

Table 3 shows the computed F-values of the differences in grain yield, REN and N content in the 32 rice varieties between years. All measurements showed significant differences among varieties and organic fertilizer treatments (LO, MO and HO, respectively), and in the interaction between variety and organic fertilizer treatment. Variations with year and the interactions between year and variety as well as between year and organic fertilizer treatment were not significant. Similar results were obtained in the measurements of SPAD and enzyme activity of GS, GPT and GOT (data not shown). Because year was not a significant factor, the data from both years were averaged.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance of F-values of grain yield, REN, and N content under organic N fertilizer.

3.1.2. Effects of OF on REN and Classification of Different Rice Varieties

REN showed an initial increase followed by a decrease with increasing organic fertilizer. Under LO, MO and HO treatment, the average REN of all varieties was 20.18%, 24.39% and 22.33%, respectively (Table 4). The highest variable coefficient (31.40%) was recorded with LO treatment and the lowest (18.88%) with MO. Thus, MO treatment resulted in the highest REN value, and was therefore chosen as the optimal OF treatment for the remainder of the analysis.

Table 4.

Variation in the REN of different rice varieties at different organic fertilizer levels under organic farming (%).

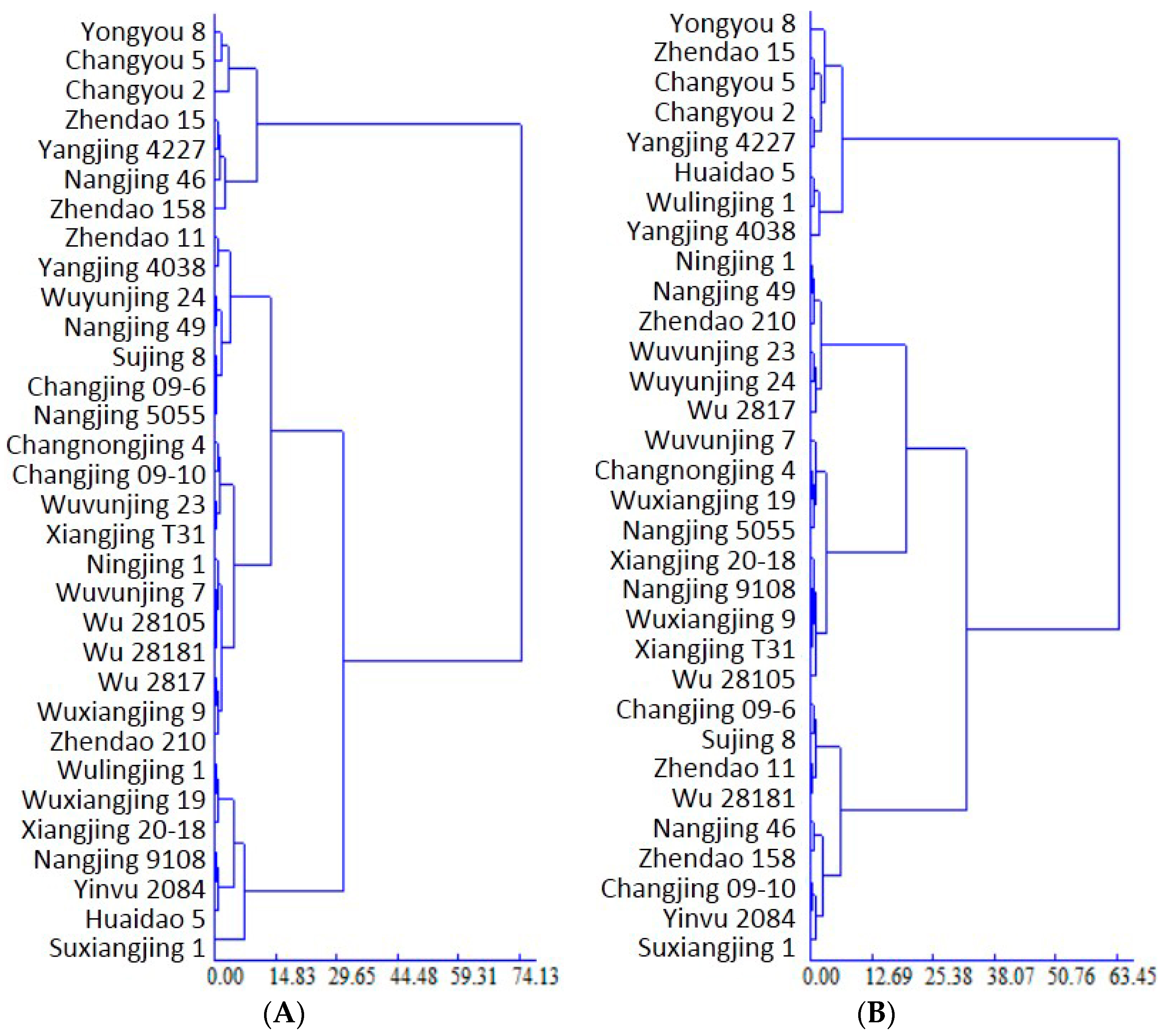

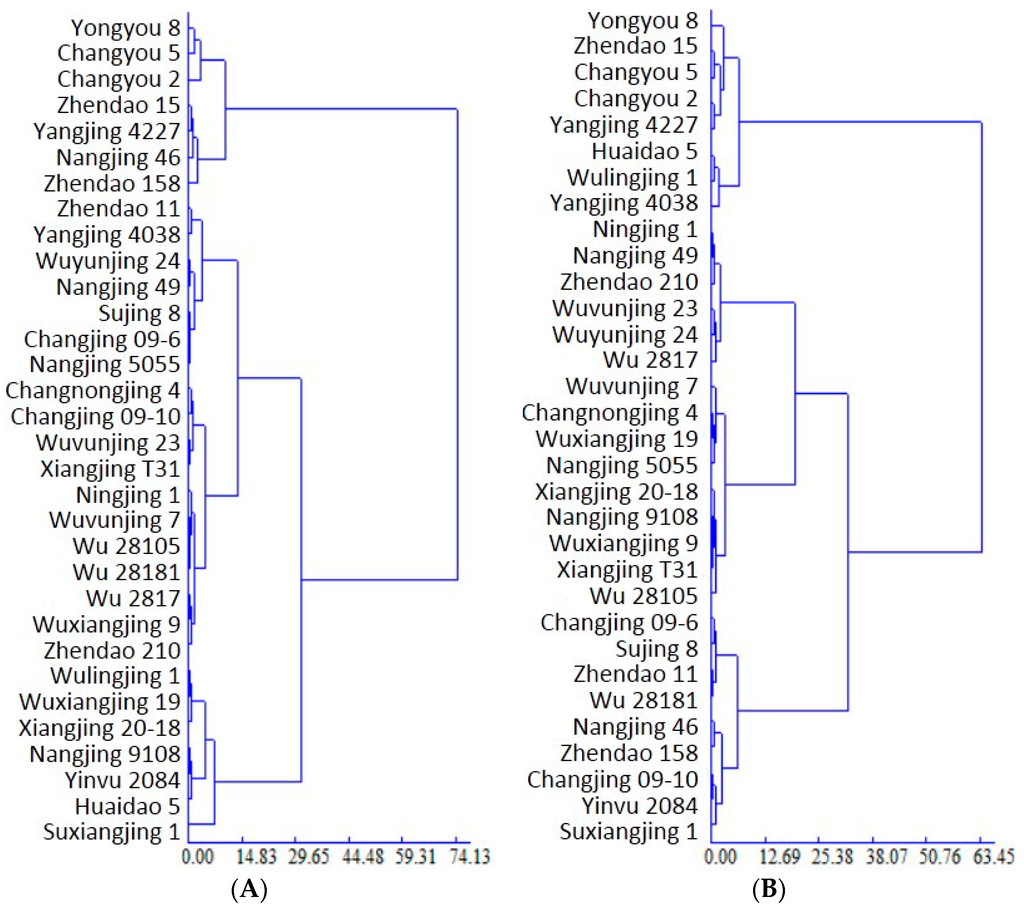

To clarify the REN attributes of the different rice varieties under OF-MO, after determining the Euclidean distance and sum of squared residuals, the dendrogram was built. Accordingly, the varieties were classified into three types as follows (Figure 1A): organic high REN (7 varieties; REN: 27.04%–33.66%, mean REN: 29.96%, variation coefficient: 7.93%), organic medium REN (18 varieties; 20.09%–24.37%, 21.88% and 6.11%, respectively) and organic low REN (7 varieties; 13.35%–18.86%, 17.15% and 11.06%, respectively). The mean REN value of all varieties was 22.61%, with the highest value (33.66%) recorded in Yongyou 8 and lowest (13.35%) in Suxiangjin 1.

Figure 1.

Dendrogram showing the Japonica rice varieties based on recovery efficiency of nitrogen under organic farming (A) and conventional farming (B).

3.1.3. Difference in REN between Varieties under CF

Under CF, the average REN was 37.66%, with the highest value (45.83%) recorded in Yongyou 8 and the lowest (31.44%) in Suxiangjing 1. Based on these results, the varieties were classified into three types by Euclidean distance (Figure 1B): high REN under CF (8 varieties; average REN of 43.34% and variation coefficient of 3.58%); medium REN under CF (15 varieties; 37.39% and 4.64%, respectively); and low REN under CF (9 varieties; 33.06% and 3.16%, respectively). Comparisons of REN under CF and OF revealed extremely significant higher efficiency under CF.

3.1.4. Genotype Screening of Transformation and Synergy in REN under OF and CF

Comparisons of the differences in REN between OF and CF (Table 5) resulted in classification of the genotypes into four types: high REN under both OF and CF (synergistically high REN, type-A); high REN under OF and low REN under CF (high-low REN transition, type-B); low REN under OF and high REN under CF (low-high REN transition, type-C); and low REN under both OF and CF (synergistically low REN, type-D).

Table 5.

Representative varieties showing REN Synergism and transformation under organic (OF) and conventional farming (CF).

All varieties were regular Japonica rice varieties except for three hybrids, Changyou 5, Yongyou 8 and Changyou 2, which have been proven to be a particular germplasm resource with significantly increasing yield and excellent quality traits [29] despite having high REN under OF. Of the regular Japonica varieties, Zhendao 15 and Yangjing 4227 were typical type-A varieties, Nangjing 46 and Zhendao 158 were type-B, Huaidao 5 and Wulingjing 1 were type-C, and Suxiangjing 1 and Yinyu 2084 were type-D.

3.2. Grain Yield and Yield Components in the Different Rice Varieties under OF and CF

In all the typical rice varieties, the number of panicles per unit area was significantly higher under CF than OF (Table 6). The OF/CF ratio of panicle number per unit area was highest in type-B followed by type-D, and lowest in type-C. Compared to CF, the number of spikelets per panicle in type-A and B rice showed a small but insignificant increase under OF. In contrast, type-C and D rice showed a significant decrease. The average OF/CF ratio of percentage of filled grains was 90.77%, 86.51%, 88.34% and 90.04% in type-A, B, C and D rice, respectively, with a significant decrease under OF. In contrast, the average OF/CF ratio of 1000-grain weight was greater under OF than CF in all varieties. Compared with CF treatment, grain yield significantly decreased under OF by 20.67%, 17.46%, 41.84% and 26.09% in type-A, B, C and D rice, respectively. Type-C and D rice showed higher grain yield losses than type-A and B rice under OF, suggesting that organic N efficient type-A and B were able to maintain relatively high grain yield under OF.

Table 6.

Grain yield and yield components in the different types of rice under organic (OF) and conventional farming (CF).

3.3. SPAD and N Values in Flag Leaves during the Key Growth Periods under OF and CF

3.3.1. SPAD Values

SPAD values report on the leaf chlorophyll content, which indicates the leaf N remobilization status. A dynamic change in SPAD values was detected in the flag leaves, the most important functional leaf in rice. SPAD values first increased then decreased with growth under both CF and OF (Table 7), and were significantly higher in all varieties under CF compared to OF. In type-A rice, SPAD values under OF were 95.35%, 96.83%, 96.06%, 95.85% and 95.50% of those under CF at booting, heading, middle-filling, late-filling and maturity, respectively. Type-D rice presented a similar trend; however, in type-B rice values under OF were 96.26%, 97.23%, 98.64%, 98.70% and 99.29% of those under CF, respectively. Moreover, the decreasing trend in type-B rice under OF was slow and smooth compared to that under CF. In contrast, SPAD values in type-C rice showed an opposite trend to type-B. These data demonstrate that farming mode, organic versus conventional, had only a small effect on SPAD values in type-A and D rice, but a greater effect on type-B and C.

Table 7.

Effects of organic (OF) and conventional farming (CF) on SPAD values in flag leaves during key growth periods.

3.3.2. N Content

During growth, the N content of the flag leaves first increased then decreased similarly to SPAD values, reaching a maximum at heading (Table 8). The N content of all varieties was higher under CF than OF. Moreover, the decline in N content in type-A and D rice was relatively smaller than that in type-B and C. In type-B, the range of N content was much smaller under OF, while in type-C, the range was smaller under CF. Thus, OF slowed down the decline in N content in varieties with a high REN under OF, whereas CF did not.

Table 8.

Effects of organic (OF) and conventional farming (CF) on N content in flag leaves during key growth periods (g·kg−1).

3.4. Effect on Key Enzymes of N Metabolism under OF and CF

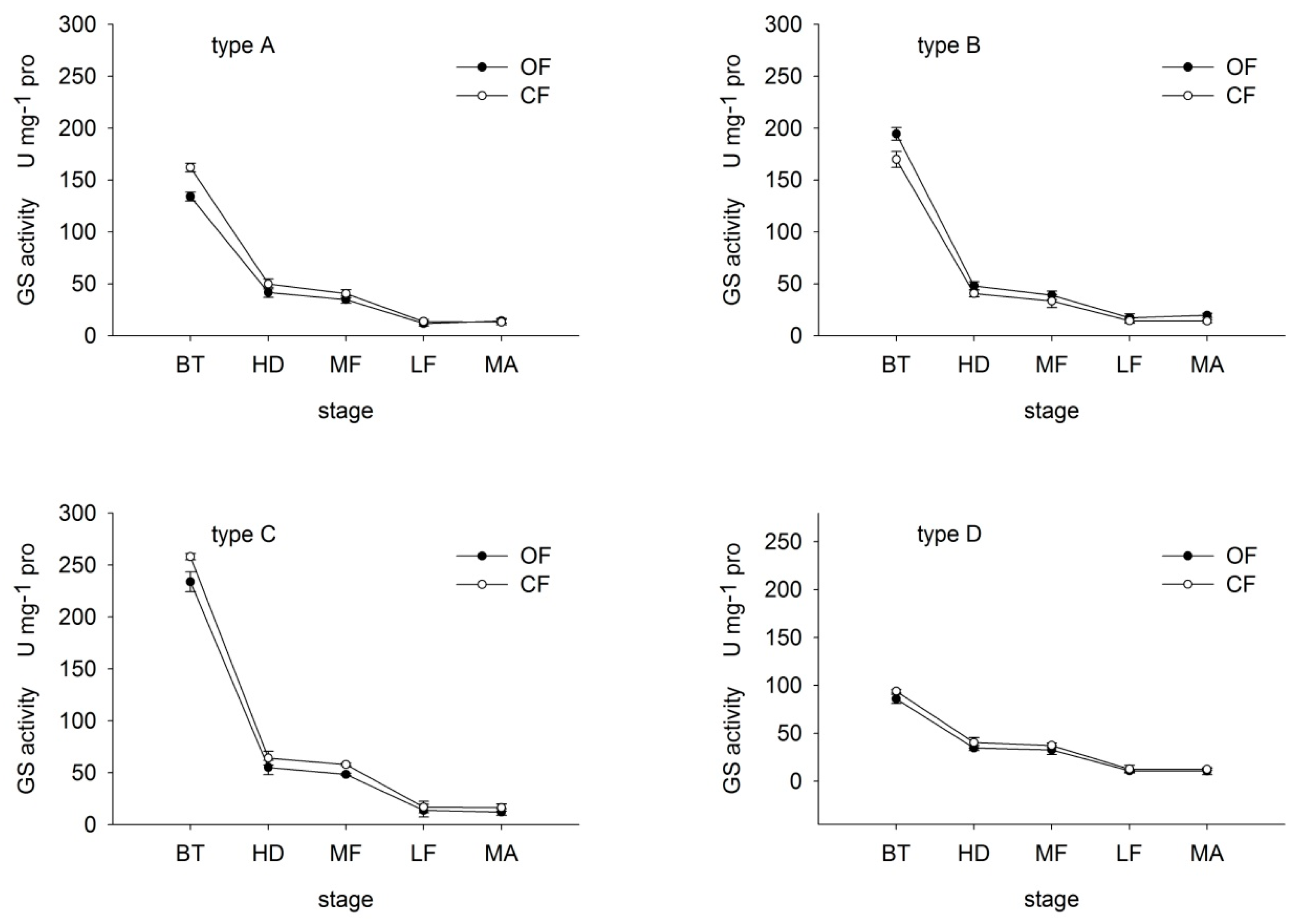

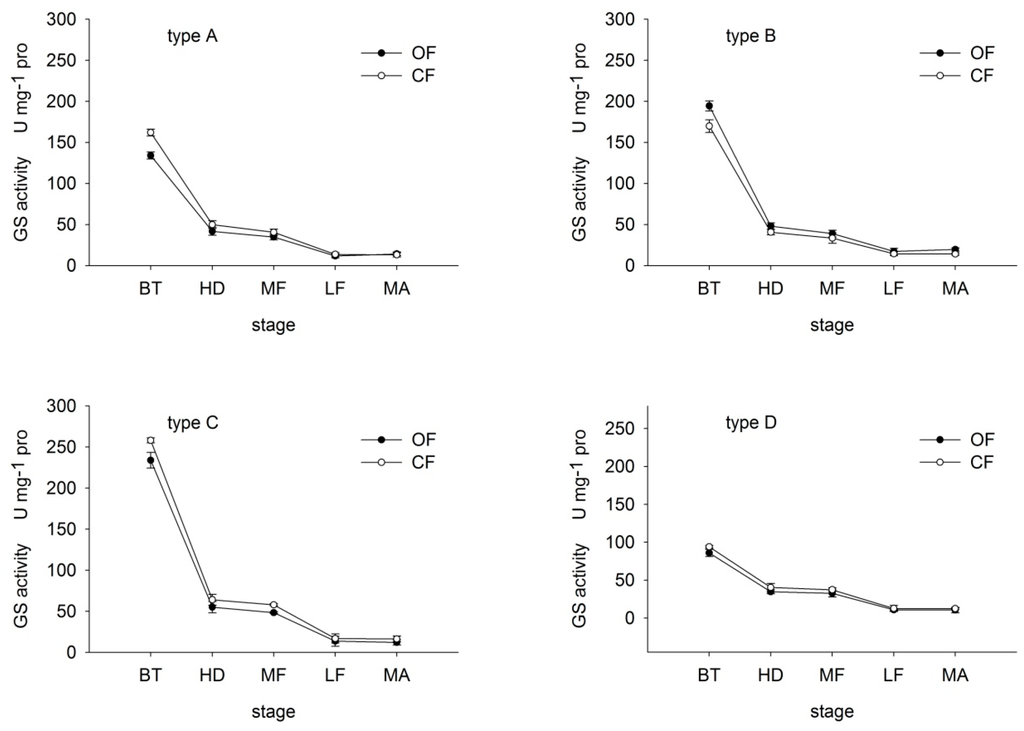

3.4.1. GS Activity

GS catalyzes the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent condensation of ammonia (NH3) with glutamate to yield glutamine. Many studies of the GS enzyme justify the importance of this enzyme in metabolism of plant N [18,21]. GS activity in all varieties showed the biggest drop from booting stage to heading (Figure 2). Under both OF and CF, GS activity decreased with growth in all varieties, except at maturity. Under OF, GS activity in type-A rice was 82.71%, 83.85%, 85.88%, 86.16% and 117.74% that under CF at booting, heading, middle-filling, late-filling and maturity, respectively. In contrast, in type-B rice, values under OF were 114.54%, 116.35%, 117.95%, 119.69% and 139.97% those under CF, respectively, suggesting that GS activity was greater under OF than CF in type-B rice. Type-C and D rice presented an opposite trend.

Figure 2.

Effects of organic (OF) and conventional farming (CF) on GS activity in flag leaves of the four different types (A–D) of rice during key growth periods. BT, booting, HD, heading: MF, middle-filling; LF, late-filling, MA, maturity. Type-A, high REN under both OF and CF; type-B, high REN under OF whereas low REN under CF; type-C, low REN under OF whereas high REN under CF; type-D, low REN under both OF and CF. Values are means with standard errors shown by the vertical bars (n = 4).

These findings suggest that OF increased GS activity in flag leaves of type-B rice. Moreover, under OF, the decrease in GS in type-A and B rice was less than that under CF. In contrast, the decrease in type-C and D rice was greater under OF than CF. That is, OF slowed the decline in GS activity in N efficient varieties, thereby maintaining a high N assimilation rate in later growth stages.

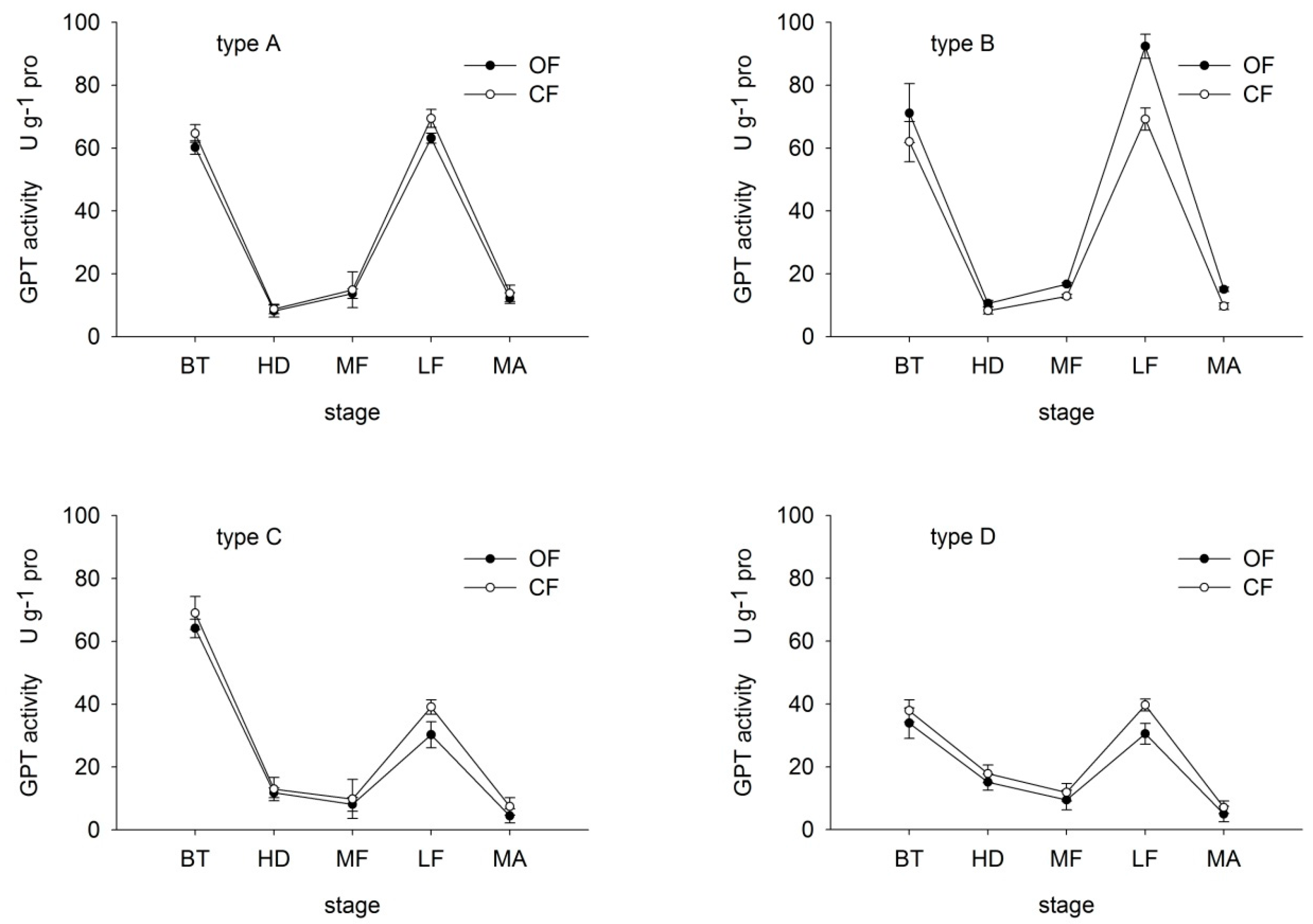

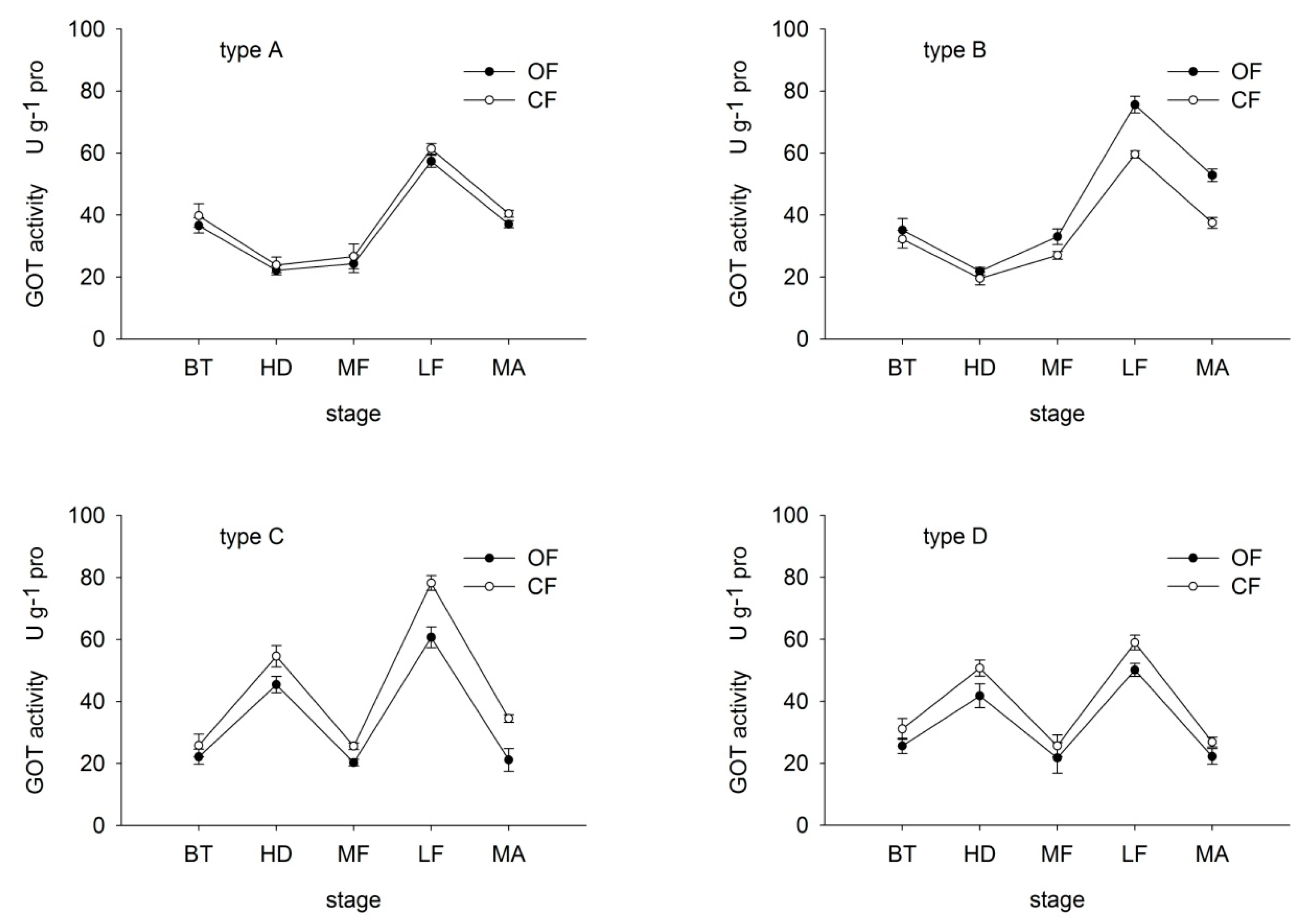

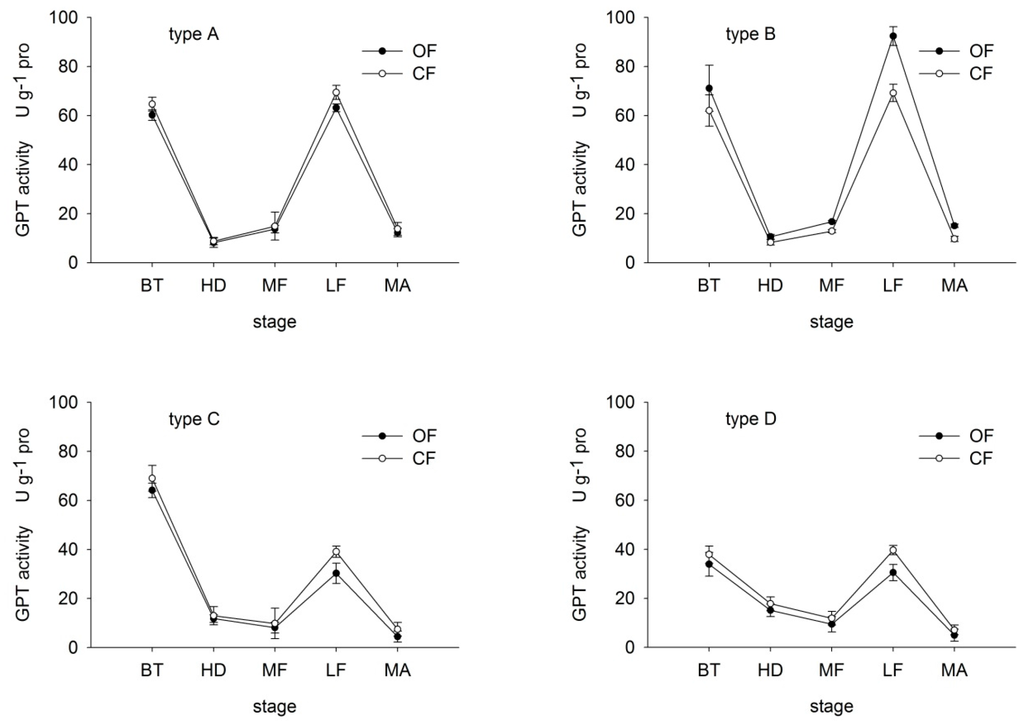

3.4.2. GPT and GOT Activity

GPT and GOT are the most common forms of transaminase in plant. Leaf GPT and GOT activities were determined to gain a better understanding of the nitrogen assimilation response [27]. Under both OF and CF, GPT activity in all varieties decreased then increased before dropping once again at maturity (Figure 3). In type-C and D rice, GPT activity increased from the middle-filling stage, while in type-A and B the increase occurred earlier, at the heading stage. These findings suggest that GPT activity recovered more quickly in N efficient varieties, thereby maintaining the N transformation ability. GPT activity in type-B rice was particularly noteworthy, with values under OF 114.69%, 126.87%, 130.03%, 133.48% and 155.39% of those under CF at booting, heading, middle-filling, late-filling and maturity, respectively. In contrast, the remaining three types showed lower GPT values under CF than OF at each corresponding stage.

Figure 3.

Effects of organic (OF) and conventional farming (CF) on GPT activity in the flag leaves of the four different types (A–D) during key growth periods. Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

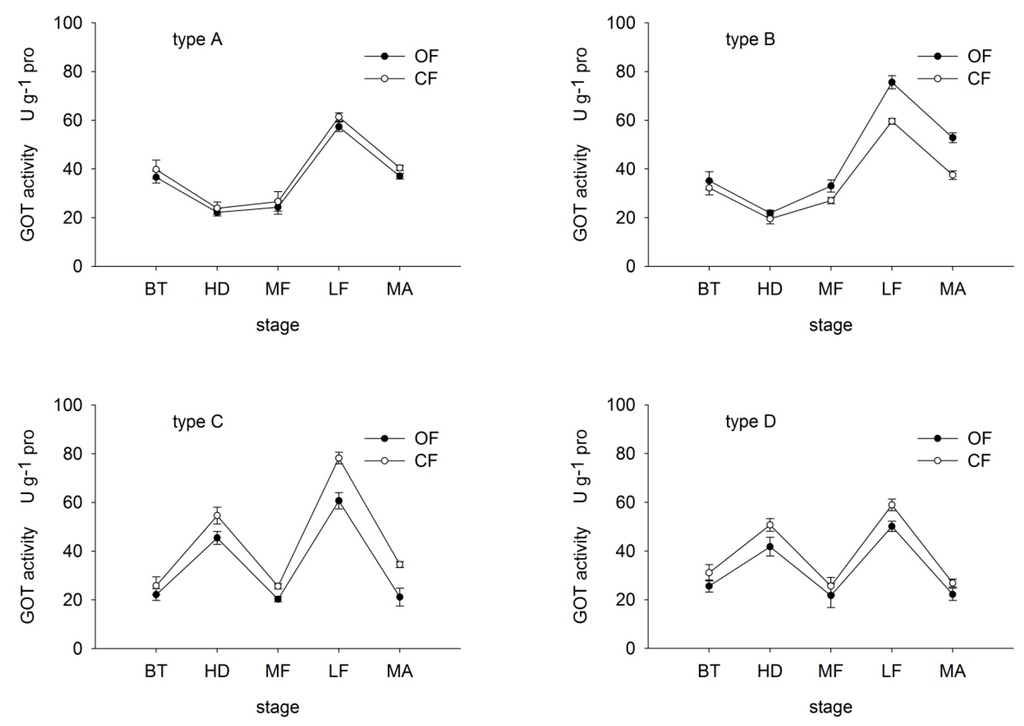

In type-A and B rice, GOT activity first decreased then increased before dropping again at maturity, reaching a peak at the late-filling period (Figure 4). In type-C and D rice, GOT activity peaked at the heading and late-filling stages. The OF/CF ratio of GOT activity was similar to that of GPT activity. The ratio in type-A, C and D rice ranged from 91.15% and 92.86%, 61.26% and 85.90%, and 82.28% to 84.98%, respectively, throughout growth. In contrast, in type-B rice, the ratio ranged from 109.19% to 149.79%. These findings suggest that under OF, the decrease in GOT and GPT in type-A and B rice was lower than that in type-C and D. Moreover, under OF, organic N efficient type-A and B were able to maintain relatively high N transformation abilities.

Figure 4.

Effects of organic (OF) and conventional farming (CF) on GOT activity in the flag leaves of the four different types (A–D) during key growth periods. Abbreviations as in Figure 2.

4. Discussion

4.1. NUE Consistency and Conversion under CF and OF

In conventional cropping systems, different measurements of NUE are commonly applied; for example, REN, agronomic efficiency of nitrogen (AEN), physiological efficiency of nitrogen (PEN), and partial factor productivity of nitrogen (PFPN). Consequently, research results often vary according to these different indexes. REN is commonly used to evaluate the actual use efficiency and loss rate of N [26]. In a previous study, REN was found to range between 30% and 40% under CF in China [18], which is lower than in other developed countries, such as USA, Canada and so on. In the current study, REN revealed a synergistically high NUE type, high-low NUE transition type, low-high NUE transition type and synergistically low NUE type. PFPN, as an integrative index of the total economic output relative to utilization of all N sources, was suggested by Hasegawa et al. [30] as a useful criterion for organic cropping systems in which animal compost or organic fertilizer are applied. In future studies, to fully clarify the high grain yield and high NUE under OF, additional NUE indexes such as AEN and PEN will be used to comprehensively evaluate the N use mechanism.

The literature on NUE tends to focus on CF or inorganic/organic fertilization, rather than OF [26,31,32]. Application of organic-inorganic compound fertilizer was previously found to have a positive effect on soil organic carbon accumulation and crop productivity in rice fields, reducing chemical fertilizer use, optimizing the physical qualities of paddy soil, and improving long-term sustainability through increased N efficiency, possibly as a result of enhanced microbial activity [31,32,33]. However, OF differs from organic fertilizer experiments. In the district of Xinjiang, a high dose of organic fertilizer was found to result in lower REN and AEN values than under a low organic fertilizer dose, and far lower than under CF [16]. In this study, the average NUE of all varieties was higher (37.66%) under CF than under OF (22.61%), consistent with Sun et al. [16]. We also found that an increase in organic fertilizer resulted in an initial increase in NUE followed by a decrease, with the maximum value at a medium dose. In order to enhance NUE under OF, it is therefore important to control the dose of organic fertilizer applied.

We subsequently examined the possible reasons for the higher NUE under CF than OF. Liu et al. [25] suggested that under low soil fertility, chemical fertilizer provides nutrients quickly, thereby promoting rapid growth. In contrast, with organic fertilizer, the nutrient release rate is very late, and therefore there is insufficient available nitrogen for growth. Thus, based on the conversion of N, organic fertilizer acts as a slow-release N fertilizer, with nutrients released and absorbed in a step-by-step manner, lasting longer. This study focused on NUE, and therefore, requires further analysis of the long-acting release mechanism under OF.

4.2. Relationship between Yield and NUE under OF and CF

A technology gap is thought to exist between rice yield and environmental efficiency scores based on levels of pure N use [34,35]. As a result, farmers tend to increase the use of external nutrients such as N to compensate for potential yield losses during the initial OF conversion period [11,16]. In old alluvial soil of India, 40% nitrogen and 25% phosphate chemical fertilizer can safely be supplemented by low-cost, natural resource-based bio-fertilizer (Azotobacter sp.) at 12 kg·ha−1 and organic manure at 10.00 t·ha−1 to make rice cultivation more productive and profitable over a long period [3]. Conversely, in the case study in a farmer’s fields in Japan, the highest grain yield was demonstrated to be obtained via internal nitrogen nutrient cycling of residues, such as rice straw, rice bran and weeds in lowland rice farming [36].

In our previous study, we found positive correlations between yield and dry matter accumulation at maturity, N uptake at maturity, REN and AEN in three high-quality rice varieties under OF [17]. In this study, we choose Japonica rice cultivars commonly grown in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, Jiangsu province. Under OF, spike number, grain number per panicle and spikelet number increased with an increasing dose of organic fertilizer. In contrast, the percentage of filled grains and 1000-grain weight showed an opposite trend, consistent with the conclusions of Ling et al. [23]. Similarly, this study demonstrated the effects of OF and CF on the various attributes of yield, revealing two synergy models: one showing consistently high yield, the other consistently low yield. Varieties showing high yield included the hybrid Japonica rice varieties Yongyou 8, Changyou 5 and Changyou 2, which often demonstrate high yield, achieving high output not only under CF but also at low soil fertility under OF. Those showing consistently low yield under both OF and CF included Suxiangjing 1 and Yingyu 2084. It is worth mentioning that the difference in yield between OF and CF was highly significant in some varieties; for example, Huaidao 5 and Wulingjing 1 showed high yield greater than 9 t·hm−2 under CF, but an average of only 5.98 t·hm−2 under OF.

Yield was always greater with CF than OF and the yield advantages were more prominent in the hybrid rice varieties than the conventional types under OF. At a late growth period under OF, the decrease in the range of leaf area and photosynthetic potential were found to be smaller, and moreover, the average population growth rate and percentage of dry matter accumulation were higher [29]. Therefore, to fully determine the optimal rice genotypes for OF, we need to screen, identify and evaluate various varieties under both OF and CF.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that when comparing NUE between CF and OF, some varieties obtain consistently high (type-A) and others consistently low NUE (type-D), whereas some transform from high to low (type-C) and others from low to high under OF compared to CF (type-B). From booting to maturity, higher values of SPAD and N content and less of a decline in GS, GPT and GOT activity in flag leaves were observed in type-A and B compared to type-C and D varieties under OF. Moreover, organic N-efficient type-A and B maintained relatively higher grain yield under OF. Accordingly, varieties with synergistically high NUE and high grain yield under OF were identified.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31201154 and 31571596), Three New Agriculture Project of Jiangsu Province (SXGC[2016]212 and SXGC[2015]089), Jiangsu Key Research and Development Plan (BE2015340,BE2016351), Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(16)1003), the Open Project Program of Key Laboratory of Crop Physiology (No. K12008) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Author Contributions

Lifen Huang and Hengyang Zhuang conceived and designed the experiments; Jie Yang performed the experiments; Jie Yang and Lifen Huang analyzed the data; Jie Yang contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; Lifen Huang wrote the paper; Xiaoyi Cui, Huozhong Yang and Shouhong Wang revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NUE | nitrogen use efficiency |

| OF | organic farming |

| CF | conventional farming |

| CK | control check |

| LO | low level of organic fertilizer |

| MO | medium level of organic fertilizer |

| HO | high level of organic fertilizer |

| BT | booting |

| HD | Heading |

| MF | middle-filling |

| LF | late-filling |

| MA | maturity |

| type-A | high NUE under both OF and CF |

| type-B | high NUE under OF whereas low NUE under CF |

| type-C | low NUE under OF whereas high NUE under CF |

| type-D | low NUE under both OF and CF |

| GS | glutamine synthetase |

| GPT | glutamic-pyruvic transaminase |

| GOT | glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase |

| SPAD | soil and plant analyzer development |

| REN | recovery efficiency of nitrogen |

| PFPN | partial factor productivity of nitrogen |

| AEN | agronomic efficiency of nitrogen |

| PEN | physiological efficiency of nitrogen |

References

- Pimentel, D.; Hepperly, P.; Hanson, J.; Douds, D.; Seidel, R. Environmental, energetic, and economic comparisons of organic and conventional farming systems. Bioscience 2005, 55, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reganold, J.P.; Elliott, L.F.; Unger, Y.L. Long-term effects of organic and conventional farming on soil erosion. Nature 1987, 330, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, M.; Datta, J.K.; Garai, T.K. Steps toward alternative farming system in rice. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 51, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmotte, S.; Barbier, J.M.; Mouret, J.C.; Le Page, C.; Wery, J.; Chauvelon, P.; Sandoz, A.; Lopez Ridaura, S. Participatory integrated assessment of scenarios for organic farming at different scales in Camargue, France. Agric. Syst. 2016, 143, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleemann, L.; Abdulai, A.; Buss, M. Certification and access to export markets: Adoption and return on investment of organic-certified pineapple farming in Ghana. World Dev. 2014, 64, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, D.G.; Perkins, A.J.; Wilson, J.D.; Alexander, I.H.; Grice, P.V.; Evans, A.D. Does organic farming benefit biodiversity? Biol. Conserv. 2005, 122, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, M.P.D.; Wright, D.J.; Leather, S.R. The effects of farming system and fertilisers on pests and natural enemies: A synthesis of current research. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 141, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.D. Production status and strategies of organic rice in China. Chin. Rice 2007, 3, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.M.; Joachim, S. Review of history and recent development of organic farming worldwide. Agric. Sci. China 2006, 5, 169–178. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, N.; Baba, Y.G.; Kusumoto, Y.; Tanaka, K. A review of post-war changes in rice farming and biodiversity in Japan. Agric. Syst. 2015, 132, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokazono, S.; Hayashi, K. Variability in environmental impacts during conversion from conventional to organic farming: A comparison among three rice production systems in Japan. J. Clean Prod. 2012, 28, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, B.; Nesme, T.; David, C.; Pellerin, S. Nutrient recycling in organic farming is related to diversity in farm types at the local level. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 204, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, F.M.; Saleh, W.D.; Moselhy, M.A. Bioconversion of rice straw and certain agro-industrial wastes to amendments for organic farming systems: 1. Composting, quality, stability and maturity indices. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 5952–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, R.H.; Kamprath, E.J.; Jackson, W.A. Analysis and interpretation of factors which contribute to efficiency of nitrogen utilization. Agron. J. 1982, 74, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirel, B.; Gouis, J.L.; Ney, B.; Gallais, A. The challenge of improving nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants: Towards a more central role for genetic variability and quantitative genetics within integrated approaches. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 2369–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.P.; Li, G.X.; Meng, F.Q.; Guo, Y.B.; Wu, W.L.; Yili, H.M.; Chen, Y. Nutrients balance and nitrogen pollution risk analysis for organic rice production in Yili reclamation area of Xinjiang. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2011, 27, 158–162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.F.; Yu, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, R.; Bai, Y.C.; Sun, C.M.; Zhuang, H.Y. Relationships between yield, quality and nitrogen uptake and utilization of organically grown rice varieties. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.B.; Huang, J.L.; Zhong, X.H.; Yang, J.C.; Wang, H.G.; Zou, Y.B.; Zhang, F.S.; Zhu, Q.S.; Buresh, R.; Witt, C. Research strategy in improving fertilizer-nitrogen use efficiency of irrigated rice in China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2002, 35, 1095–1103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Haefele, S.M.; Jabbar, S.M.A.; Siopongco, J.; Tirol-Padre, A.; Amarante, S.T.; Sta, C.P.; Cosico, W.C. Nitrogen use efficiency in selected rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes under different water regimes and nitrogen levels. Field Crop. Res. 2008, 107, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.Q.; Crawford, N.M. ldentification of the Arabidopsis CHL3 Gene as the Nitrate Reductase Structural Gene MA2. Plant Cell 1991, 3, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, A.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, G.; Shi, L.; Xu, F.; Cai, H. Accumulated expression level of cytosolic glutamine synthetase 1 Gene (OsGS1;1 or OsGS1;2) alter plant development and the carbon-nitrogen metabolic status in rice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, X.G.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D.Y.; Xu, C.M.; Ji, C.L.; Zhang, X.F. Response of Rice Nitrogen Physiology to High Nighttime Temperature during Vegetative Stage. Sci. World J. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Q.H.; Zhang, H.C.; Ju, Z.W.; Dai, Q.G.; Huo, Z.Y. Effect of different dosages of Sanan bio-organic fertilizer on organic rice production, quality and utilization of nitrogen absorption. Chin. Rice. 2010, 1, 17–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, S.; Forno, D.; Cock, J.; Gomez, K. Laboratory Manual for Physiological Studies of Rice; International Rice Research Institute: Metro Manila, Philippines, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.J.; Chen, T.T.; Wang, Z.Q.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.C.; Zhang, J.H. Combination of site-specific nitrogen management and alternate wetting and drying irrigation increases grain yield and nitrogen and water use efficiency in super rice. Field Corp. Res. 2013, 154, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Chu, G.; Liu, L.J.; Wang, Z.Q.; Wang, X.M.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.C.; Zhang, J.H. Mid-season nitrogen application strategies for rice varieties differingin panicle size. Field Crop. Res. 2013, 150, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Jiang, S.H.; Tao, Q.N. Colorimetric method for plant transaminase (GOT and GPT activity). Chin. J. Soil Sci. 1998, 29, 136–138. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.L.; Huang, D.Y.; Chen, A.L.; Wei, W.X.; Brookes, P.C.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.S. Differential responses of crop yields and soil organic carbon stock to fertilization and rice straw incorporation in three cropping systems in the subtropics. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 184, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.F.; Zhang, R.; Yu, J.; Jiang, L.L.; Su, H.D.; Zhuang, H.Y. Effects of organic farming on yield and quality of hybrid Japonica Rice. Acta Agron. Sin. 2015, 41, 458–467. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, H.; Furukawa, Y.; Kimura, S.D. On-farm assessment of organic amendments effects on nutrient status and nutrient use efficiency of organic rice fields in Northeastern Japan. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 108, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.X.; Zhou, P.; Li, Z.P.; Smith, P.; Li, L.Q.; Qiu, D.S.; Zhang, X.H.; Xu, X.B.; Shen, S.Y.; Chen, X.M. Combined inorganic/organic fertilization enhances N efficiency and increases rice productivity through organic carbon accumulation in a rice paddy from the Tai Lake region, China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 131, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ni, T.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Fang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Li, R.; Shen, B.; Shen, Q. Effects of organic–inorganic compound fertilizer with reduced chemical fertilizer application on crop yields, soil biological activity and bacterial community structure in a rice–wheat cropping system. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 99, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Fang, H.; Mooney, S.J.; Peng, X.H. Effects of long-term inorganic and organic fertilizations on the soil micro and macro structures of rice paddies. Geoderma 2016, 266, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, S.; Guo, H.X. The environmental efficiency of non-certified organic farming in China: A case study of paddy rice production. China Econ. Rev. 2014, 31, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Humphreys, E.; Salim, M.; Chauhan, B.S. Growth, yield and nitrogen use efficiency of dry-seeded rice as influenced by nitrogen and seed rates in Bangladesh. Field Crop. Res. 2016, 186, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Toriyama, K.; Kobayashi, K. Nitrogen supply via internal nutrient cycling of residues and weeds in lowland rice farming. Field Crop. Res. 2012, 137, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).