Abstract

Employees contribute to the sustainability of organizations in many ways, yet the specific impact of employee voice on employee performance appraisal, as an element of organization sustainability, is not clear. Based on the attribution theory, we present a model to investigate the relationship between employee voice and employee performance appraisal. Using the PLS (Partial Least Squares) method, we test our model’s hypotheses with 273 dyads of supervisor-employee questionnaires administered on a branch of a state-owned enterprise in China. The results show that promotive voice is positively attributed to prosocial motives and constructive motives, while prohibitive voice is not significantly attributed to prosocial motives and constructive motives. The attribution of prosocial motives and constructive motives has a significant and positive effect on employees’ performance appraisal. Moreover, the attribution of prosocial motives and constructive motives fully mediates the relationship between promotive voice and performance appraisal, but has no mediating effects on the relationship between prohibitive voice and performance appraisal.

1. Introduction

With market competitiveness growing due to deregulation policy and increased business entrepreneurship in recent years, firms’ external environments have become more and more uncertain, thereby increasing the difficulty of management decision-making and risking the sustainability of the organization. A sustainable organization is viewed as more than just enduring but an organization where employees are actively involved in a continuous process of change; one in which the culture of the organization embraces different ways of working, relating, and thinking to remain viable [1].

As an important information source for managerial decision-making in an environment of change, employee voice has the potential to contribute to organizational sustainability. Employee voice refers to the expression of change-oriented ideas, opinions, and suggestions to a specific target within the organization with the intent to improve the situation at work [2,3]. First line employees learn the needs of customers and suppliers, and when these employees use voice to communicate their knowledge of these stakeholders, voice plays an important role in organizational decision-making. Bashur & Oc’s (2014) study identifies the value of employee opinion in better decision making, lower turnover, and innovation in organizations [3]. The absence of employee voice (i.e., silence), may be a sign that the organization lacks morale and the opportunity to improve is at risk [4].

However, employee voice often questions the current policies and challenges the authority of decision makers. Therefore, employee voice could potentially damage interpersonal relationships, especially the relationship between a supervisor and an employee [2,5,6,7]. This raises an important and interesting question: how does the employee voice influence employee performance appraisal? The impact of employee voice on employee performance evaluation not only affects employee career development, but also the organization’s ability to deliver value and assure survival of all stakeholders, including the employees since the employee performance ratings ultimately affect the employees voice behaviors [8].

Although the contributions of employee voice to group or organizational performance are widely recognized, it is still not clear whether and how this recognition is reflected in employee performance evaluations [7]. In existing studies based on the social exchange theory [9], a typical viewpoint holds that because voice behavior can improve the team or organizational performance, supervisors should give a positive performance appraisal (i.e., high ratings) to employees who are willing to share their knowledge, ideas, and opinions for managerial problem solving. This viewpoint is supported by empirical studies which found that voice behavior is positively associated with the evaluation of employee performance [3,8,10,11]. In the existing literature, the voice is viewed as an aspect of citizenship behavior involving innovative suggestions that contribute toward changing existing practices and leading to improvements [12]. However, others have argued that voice can have unfavorable impacts on employees due to its challengeable nature. This viewpoint is also supported by some relevant findings that employee voice has a negative effect on employee career success, such as salary progression and promotion, implying that employee voice is negatively associated with employee performance ratings [6,13]. This negative relationship is more likely to occur in societies with higher power distance (e.g., the east Asian region) [14].

To integrate these competing perspectives and resolve empirical puzzles, researchers have developed varying theoretical frameworks. Burris (2012) distinguished the types of employee voice, and found that individuals who use challenging voice are less recognized than those who engage in supportive voice, and their ideas are less endorsed [15]. Moreover, Burris et al. (2013) emphasized the role of agreement and disagreement around voice between employees and supervisors [16]. They proposed that agreement around voice between employees and supervisors has a favorable impact on employees, and disagreement around voice leads to two different outcomes; employees overestimating (underestimating) their voice relative to their supervisors’ perspective will result in negative (positive) outcomes.

This paper aims to investigate the impact of employee voice on performance appraisal from the perspective of supervisor’s attribution of the motives of employee voice. As the attribution theory suggests, when people observe certain behaviors, people tend to make dispositional attribution on behaviors that are under the control of the actors [17,18]. In recent years, the attribution perspective has been widely used in the studies on organizational behavior [19,20,21]. The extant research has shown that performance appraisals are significantly influenced by the supervisor’s attribution of an employee’s motives behind certain behaviors [22,23], implying that when employees make suggestions and/or present new ideas, their motives will be perceived and attributed by supervisors, thereby influencing their performance appraisals.

By focusing on supervisor’s attribution of employee motives, this study contributes to the existing literature that deals with the relationship between employee voice and performance appraisal. In addition, most existing studies are conducted in the context of the Western culture and hence all of their conclusions may not hold in other cultures. Our study is based on a Chinese sample with substantial cultural differences. Specifically, our study is based on data collected from a state-owned Chinese enterprise, where the employees tend to remain silent due to the hierarchy structure. Accordingly, our study also aims to consider the external validity of existing results.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the hypotheses on the linkage between employee voice, supervisor attribution and performance appraisal. Section 3 introduces the methods and data. The empirical results are presented and discussed in Section 4. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Motives of Employee Voice

In the early literature, voice is identified as a response to job dissatisfaction, one in which the employee attempts to change a negative situation rather than escape from it [24]. Later, studies on voice incorporate the notion that it challenges and upsets the status quo but in a constructive manner [10,25]. For example, Van Dyne & LePine (1998) define voice as “promotive behavior that emphasizes expression of constructive challenge intended to improve rather than merely criticize” [10] (p. 109). Van Dyne et al. (2003) broaden the concept of employee voice by including suggestions as well as concerns [26].

The voice behavior is recognized as a typical organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) [27]. First, the voice behavior can benefit the unit or group and contribute toward the organization’s sustainability. Second, employee voice is a discretionary behavior, not directly or explicitly required by the contractual job requirements. Third, voice is not recognized by the formal reward system [28,29]. Under the dynamic environment, the organizations need employees to propose more ideas or suggestions, but which are not employees’ in-role behaviors. Van Dyne, Cummings, and Park’s (1995) classify the employee voice as a type of “challenging/promotive” OCB [25]. Challenging means that its focus is changing the status quo, while promotive means that its intention is constructive. Therefore, compared with other forms of OCB (e.g., helping others), voice is often viewed as a risky and costly behavior [6,7,28]. Though employee voice is not recognized by the formal reward system, it is likely to influence the supervisor perceptions, recognition, and rewards over time [28]. This implies that if the real intentions of the employees are not clearly identified, the employees might be regarded as troublemakers, which can result in negative performance ratings.

The attribution theory suggests that behavior of individuals is dictated by the underlying motives [30]. While analyzing the motives of the people who engage in OCB, several existing studies suggest that motives play a vital role in the interpretation of OCB [28,31,32,33]. Organ (1988) described those who perform OCB as “good soldiers”, which implies that the motive behind OCB is purely altruistic [28]. Bolino (1999), Hui et al. (2000) and Bolino et al. (2006) found that egoistic concerns can also motivate individuals to perform OCB [31,34,35]. Consistent with the framework of altruistic and egoistic concerns, Rioux & Penner (2001) identified three types of motives for OCB: (i) prosocial value, (ii) organizational concern and (iii) impression management [32]. Prosocial value refers to the desire to be helpful and to build positive relationships with others. Organizational concern involves the desire of employees to show pride in and commitment to the organization, whereas impression management is the desire to look good to coworkers and supervisors. Prosocial value and organizational concern are mainly altruistic. In contrast, impression management focuses on the needs of the employees.

However, Grant & Mayer’s (2009) study suggests that impression management motives “strengthen the association between prosocial motives and affiliative (initiative) but not challenging (voice) forms of citizenship” [20] (p. 906). This implies that impression management is indeed a predictor of affiliative citizenship behavior directing toward other people and the organization but is not suitable for explaining the voice behavior due to the challenging nature of the employee voice. Therefore, this paper focuses on prosocial value and organizational concern.

Based on the above discussion, we classify motives for employee voice into two types: (i) prosocial motives (prosocial values) and (ii) constructive motives (organizational concern). Prosocial motives are defined as the motives for employee voice that benefits coworkers, colleagues and other organizational members, while the constructive motives are motives for employee voice that benefits the unit, group and organization.

The condition for sustained competitive advantage may be present when the motives of employees match the interest of the firm and these interests or behaviors are expressed through performance appraisals [36].

2.2. Attribution of Voice Motives

According to the attribution theory, when employees suggest ideas or give advice to their supervisors, the supervisors often try to identify the motives behind this behavior. In accordance with Liang et al. (2012), we separate employee voice into two dimensions: the promotive and prohibitive [37]. Promotive voice refers to employees’ expression of innovative ideas or suggestions for improving the performance of their organization, while prohibitive voice focuses on the concerns about work practices and other factors that are harmful to the organization. The motives behind both promotive voice and prohibitive voice are prosocial and constructive, but promotive voice and prohibitive voice differ in content and function. Thus, the supervisors are likely to attribute promotive voice and prohibitive voice differently [28,33,38].

Promotive voice focuses on a future-oriented ideal state that aims to increase the “process gain” by making things better, which in turn benefits the supervisors and work colleagues. When employees utilize promotive voice, the altruistic motives behind this behavior can be easily recognized and interpreted by the supervisors. In contrast, the prohibitive voice, which concentrates on the past or present-oriented factors that are harmful to organizations, attempts to prevent or reduce the “process losses”. The prohibitive voice is more challengeable and may result in conflict and misunderstanding between the employees, colleagues, or supervisors by drawing the organizations’ attention to harmful factors. Thus, the constructive motive behind prohibitive voice could not be easily identified and is more likely to be misunderstood as “trouble making”. In addition, the prohibitive voice is more aggressive in style and tone. It may embarrass the supervisors and increase the perception of threat from the subordinates. As a result, the prohibitive voice tends to face strong resistance from the supervisors [15]. This is more so in a cultural setting with high power distance (e.g., in China). To mitigate the threat and maintain self-respect, the supervisors may be less likely to attribute the prohibitive voice to prosocial and constructive motive. Thus, we offer the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Promotive voice is positively associated with supervisors’ attribution of prosocial motives.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Promotive voice is positively associated with supervisors’ attribution of constructive motives.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Prohibitive voice is negatively associated with supervisors’ attribution of prosocial motives.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Prohibitive voice is negatively associated with supervisors’ attribution of constructive motives.

2.3. Attribution of the Motives and Performance Appraisal of Employees

Existing research shows that performance appraisal is significantly influenced by supervisor attribution of employees’ motives for exhibiting certain behaviors [22,23]. Not only the identification of specific motives, but also the types of attributed motives influence supervisors’ evaluations of subordinates [11]. Employees with a prosocial motive are perceived as having a strong desire to help coworkers, a concern for the wellbeing of others, and a desire to build positive relationships with colleagues, creating a positive organization climate and facilitating interpersonal harmony in the organization. For example, employees could offer some practical suggestions to resolve the interpersonal conflicts among colleagues. When supervisors believe that the voice behavior of the subordinates is driven by an altruistic rather than egoistic motive, they tend to regard the subordinates as “good citizens”, which results in positive performance appraisal [35,39,40].

Employees with a high constructive motive have a fervent desire and sense of obligation to perform behaviors that benefits the organization. These employees pay more attention to the organization, spend extra time at work, and offer useful suggestions to supervisors. As a result, the organization can function more effectively and plan for the future [37]. According to the social exchange theory [9], people tend to reciprocate helping behaviors. Supervisors will reward the employees with high performance ratings when they believe that the organization can benefit from the constructive voice of the employees. In societies with a collectivist culture (e.g., China), where people hold group values and are more concerned about collective interests [41], the attribution of prosocial motives and constructive motives are more likely to have a positive impact on employees’ performance ratings. This discussion can be summarized by two hypotheses as follows:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

Attribution of prosocial motives is positively associated with performance appraisal.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

Attribution of constructive motives is positively associated with performance appraisal.

2.4. Mediating Effect of Attribution of Motives

As discussed above, the motives behind the employee voice cannot be easily identified due to its challenging nature, and hence the employee performance appraisals are significantly affected by supervisors’ attribution of the motives. Promotive voice focuses on future-oriented factors and aims to improve organizational sustainability in new ways [37]. Hence, it is more likely to be attributed to prosocial motives and constructive motive, which can have a positive impact on employee performance appraisals. In contrast, the prohibitive voice concentrates on the past or present-oriented factors that are harmful to organizations, and attempts to prevent the damage. Moreover, the tone of prohibitive voice is more aggressive. Therefore, prohibitive voice is less likely to be attributed to prosocial motives and constructive motives, and hence it is likely to have a negative impact on employee performance appraisals. Based on this discussion, we offer the following hypotheses concerning the mediating effect of attribution of motives:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

Attribution of prosocial motives has a mediating effect on the relationship between promotive voice and performance appraisal.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

Attribution of constructive motives has a mediating effect on the relationship between promotive voice and performance appraisal.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Attribution of prosocial motives has a mediating effect on the relationship between prohibitive voice and performance appraisal.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Attribution of constructive motives has a mediating effect on the relationship between prohibitive voice and performance appraisal.

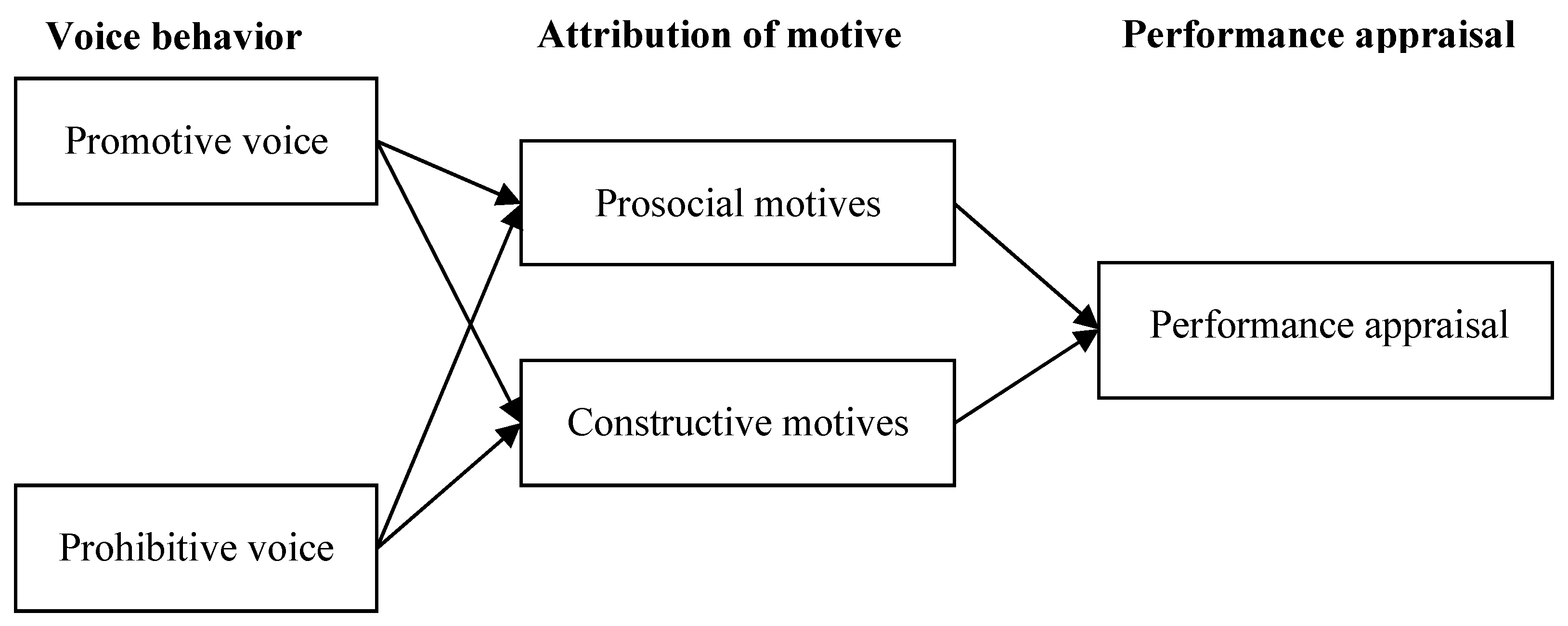

Based on the above hypotheses concerning the relationship among the employee voice, supervisor attribution of motives, and performance appraisal of employees, we propose a conceptual model, which is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model.

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Sample

The sample of respondents is drawn from a branch of a state-owned enterprise (SOE) in Guangdong Province of China. Respondents in the dyad questionnaire consist of two groups: employees and their supervisors. The employees’ questionnaire involves self-evaluation on their voice (promotive voice, prohibitive voice). The supervisors’ questionnaire involves an evaluation of the motives of employee voice (prosocial motive and constructive motive) and a rating of employees’ performance. In this study, we obtain the employees’ self-evaluation and the supervisors’ performance evaluation reports respectively. A total of 297 employees and 50 supervisors returned the questionnaires. After deleting the invalid questionnaires, we have 273 dyads of valid questionnaires including 273 employees and 48 supervisors.

Table 1 shows the basic information on respondents. For employees, 49.1% of respondents are male and 50.9% are female. Males account for 60.4% and females 39.6% of the supervisors. The respondents are divided into five age groups: under 25 years old (12.4% for employees, 0% for supervisors), 26–30 (38.5% for employees and 8.3% for supervisors), 31–40 (31.1% for employees and 56.3% for supervisors), 41–50 (15.4% for employees and 29.2% for supervisors), and over 50 years old (2.6% for employees and 6.3% for supervisors). Respondents are categorized into three educational background groups: less than a bachelor degree (37.0% for employees and 16.7% for supervisors), bachelor’s degree (54.6% for employees and 66.7% for supervisors), and a graduate degree (8.4% for employees and 16.7% for supervisors). For the tenure of respondents, there are three groups: less than 3 years (27.1% of employees and 8.3% of supervisor), 4–10 years (46.5% for employees and 16.7% for supervisors), and more than 10 years (26.4% for employees and 75.0% for supervisors).

Table 1.

Background of respondents.

3.2. Measures

The constructs in the questionnaire are measured based on the existing studies. Specifically, a 5-point Likert scale is used to measure the constructs, with measurements ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. We also collected some demographic information on the subjects (e.g., age, gender, education background, and tenure).

Promotive voice (PM). Promotive voice is measured using Liang et al.’s (2012) 5-item scale [37]. Sample items include “I proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the unit”, and “I raise suggestions to improve the unit’s working procedure”.

Prohibitive voice (PH). Prohibitive voice is measured using Liang et al.’s (2012) 5-item scale [37]. Sample items include “I advise other colleagues against undesirable behaviors that would hamper job performance”, and “I dare to voice out opinions on things that might affect efficiency in the work unit, even if that would embarrass others”.

Prosocial motives (PS). Prosocial motives are measured using Grant’s (2008) 3-item scale [42]. Sample items include “His or her suggestions benefit the coworkers”, and “His or her voice concerns for the welfare of others”.

Constructive motives (CS). Constructive motives are measured using Gorden’s (1988) 2-item scale [43]. These items include “His or her comments are constructive to the organizational performance”, and “His or her ideas are likely to enhance the work team performance”.

Performance appraisal (PA). Performance appraisal is measured based on Van Dyne & LePine’s (1998) and Burris’s (2012) scale [10,15]. Sample items include “This particular co-worker fulfills the responsibilities specified in his/her job”, and “If this employee is promoted, I expect him or her to perform well”.

We utilize the Partial Least Squares (PLS) method for empirical estimation because this methodology is particularly suited for evaluating complex structural models when the sample is small [44]. Our analysis includes two parts: the measurement model by evaluating the reliability and validity of constructs, and the structural model by assessing the R2 value and path coefficients.

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the questionnaire items. The mean values of PM and PH are 3.533 and 3.374, respectively, implying that respondents in our sample have a moderate level of promotive and prohibitive voice, which is also confirmed by the median values of PM and PH. The variances of PM and PH are small, which suggests that the means values are highly representative. The mean values of PS and CS are also at a moderate level, suggesting that, on average, supervisors have a positive attitude toward employee voice. The mean and median values of PA are 3.92 and 4, respectively, implying that the performance of most respondents in our sample is well recognized by their supervisors.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the constructs.

4. Estimation Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

In the first stage, we must confirm the validity and reliability of the latent variables (LVs) [45]. As shown in Table 3, the value of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is greater 0.5, and the value of both Construct Reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s Alpha is greater than 0.7. These results suggest that the reliability and convergent validity are accepted for the measurement model [46].

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity analysis.

The results of discriminant validity analysis are shown in Table 4 and Table 5. For the Fornee-Larcher Criterion, the square root of each construct’s AVE, as shown in Table 4, exceeds its correlations with other constructs in the model. Moreover, for the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio, as shown in Table 5, the ratios between all the constructs are lower than 0.85. These results imply an acceptable level of discriminant validity of the latent constructs [47].

Table 4.

Discriminant validity analysis (Fornee-Larcher Criterion).

Table 5.

Discriminant validity analysis (Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio).

4.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

In stage two, using 273 dyad cases, bootstrapping (with 5000 replications) was performed to assess the R2 values and path coefficients, as recommended by Hair et al. (2010) [46]. As shown in Table 6, in the case of the partial mediation model, the estimated R2 values of PA, CS and PS, respectively, are 0.469, 0.044, and 0.059. In the case of the full mediation model, the estimated R2 values of PA, CS and PS, respectively, are 0.46, 0.046, and 0.058. Based on the estimated R2 values, there seems to be little difference between the partial and full mediation models. The mediating effect of the attribution of motives is identified using both partial and full mediation models.

Table 6.

R2 values of partial and full mediation models.

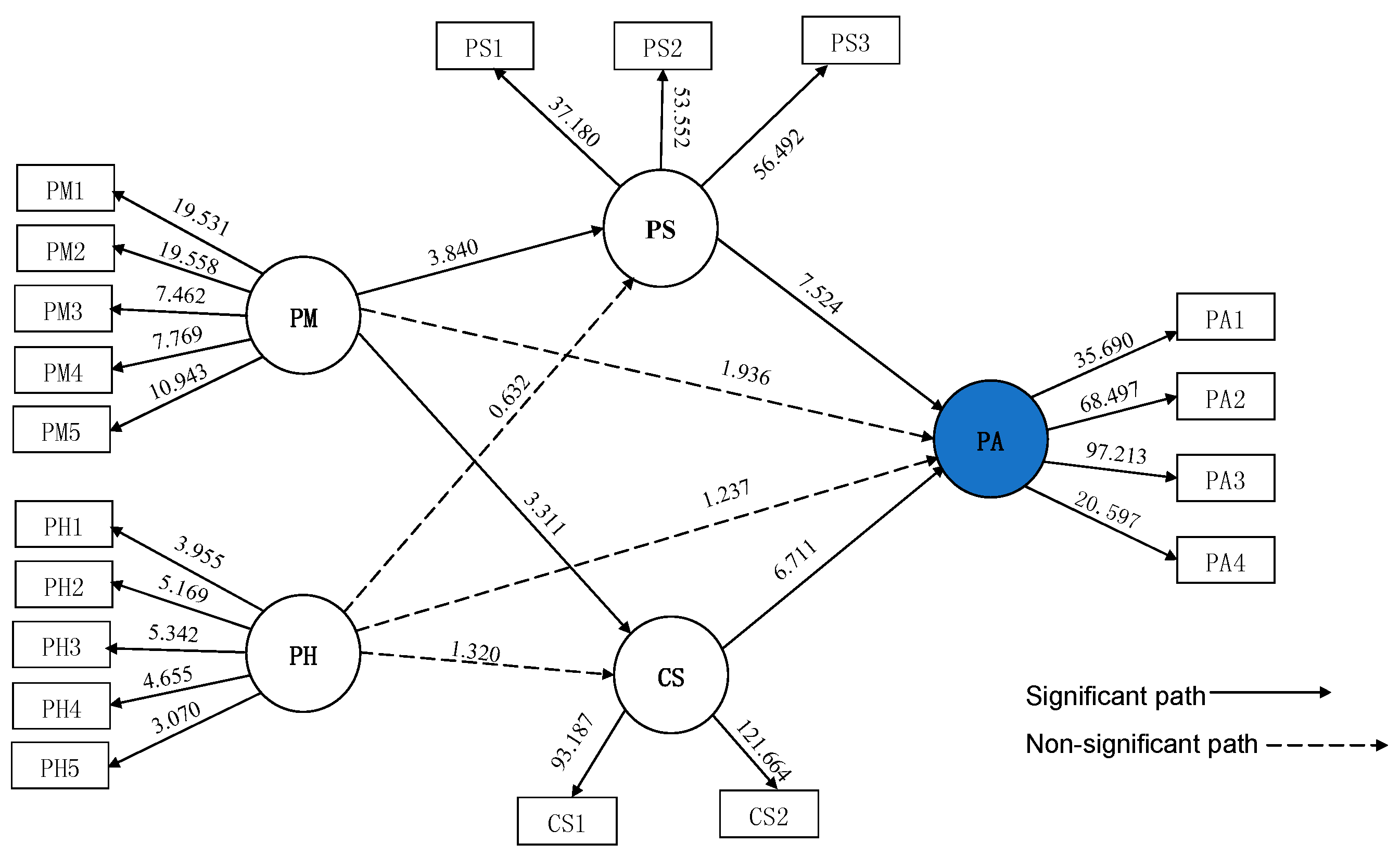

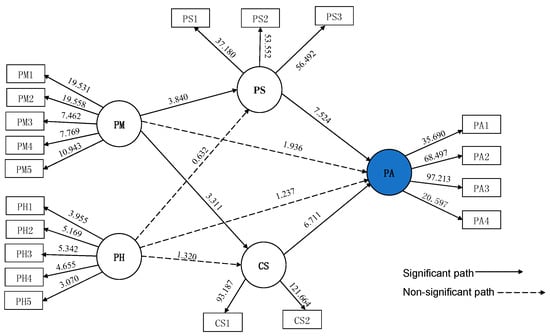

4.2.1. The Partial Mediation Model

The estimation results on the partial mediation model that are presented in Table 7 are also shown in Figure 2. At the 1% level of significance, the promotive voice of the employees is positively related to the supervisors’ attribution of prosocial and constructive motives. The path coefficients of 0.268 and 0.244, respectively, support Hypotheses H1a and H1b. The relationship between the prohibitive voice and supervisors’ attribution of prosocial and constructive motives is statistically insignificant at the 10% level. These results do not support Hypotheses H2a and H2b. The attribution of prosocial and constructive motive has a positive effect on employee performance appraisal at the 1% significance level. The path coefficients of 0.407 and 0.373, respectively, support Hypotheses H3a and H3b. Both prosocial motives and constructive motives have no partial mediation effects on the relationship between promotive voice and performance appraisal and on the relationship between prohibitive voice and performance ratings at 10% significance level. Therefore, further testing of the full mediating effect is desirable.

Table 7.

Estimation results of the partial mediation model.

Figure 2.

The partial mediation model.

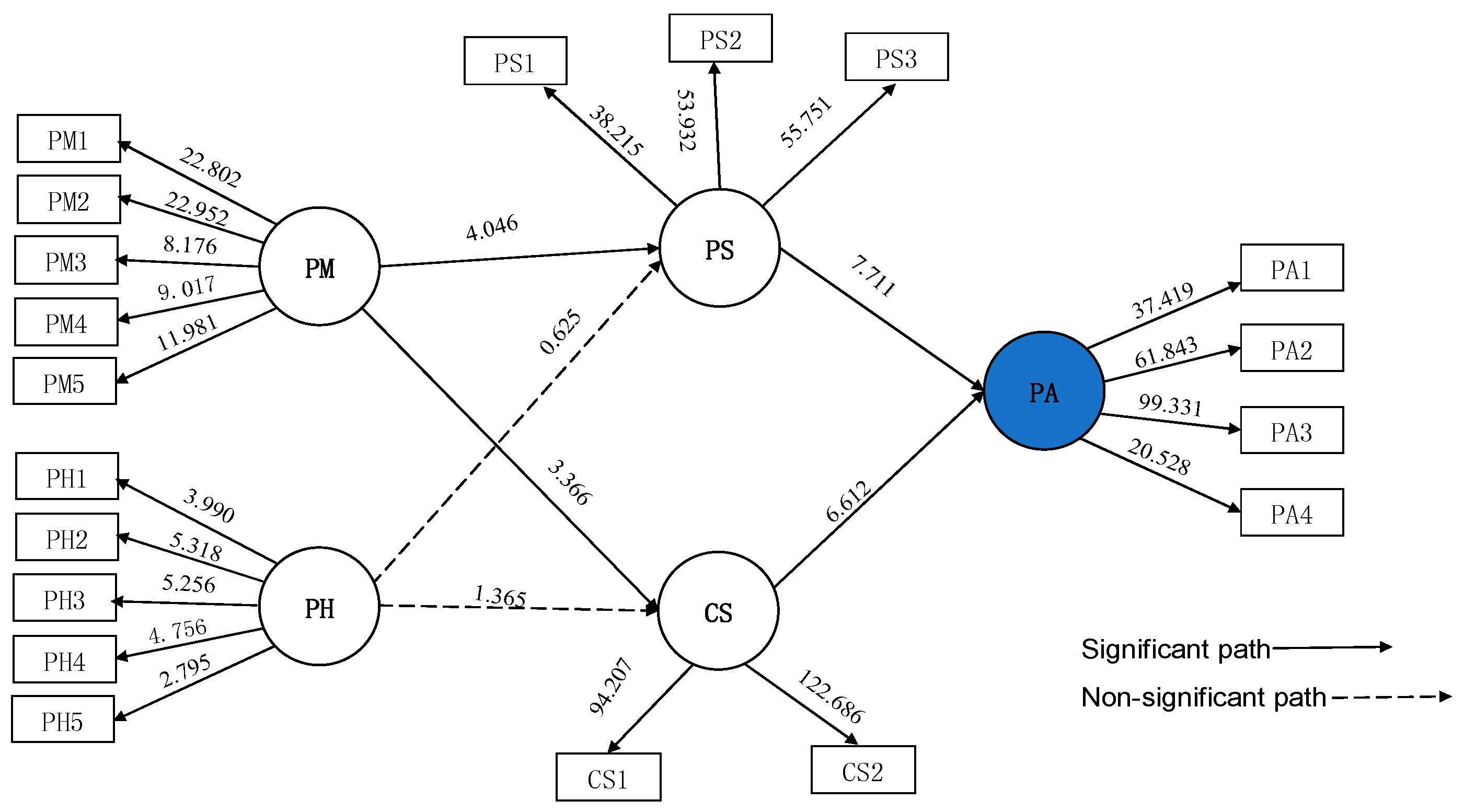

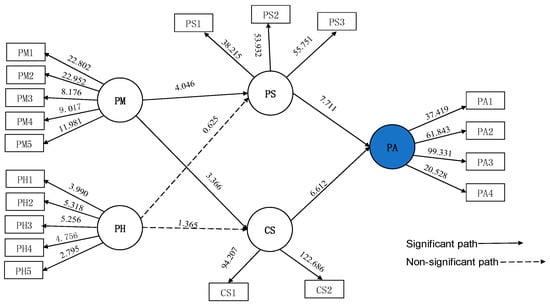

4.2.2. The Full Mediation Model

The estimation results of the full mediation model, which are presented in Table 8, are also shown in Figure 3. The promotive voice has a significant and positive effect on supervisor attribution of prosocial and constructive motive at the 1% level of significance. The path coefficients of 0.265 and 0.248, respectively, support Hypotheses H1a and H1b. Prohibitive voice is not significantly associated with supervisor attribution of prosocial and constructive motives at the 10% level of significance, implying that Hypotheses H2a and H2b cannot be supported. Supervisor attribution of prosocial and constructive motive is positively related to employee performance ratings at the 1% level of significance. The path coefficients of 0.394 and 0.360, respectively, support Hypotheses H3a and H3b. Supervisor attribution of prosocial and constructive motive has a full mediation effect on the relationship between promotive voice and performance ratings at the 1% level of significance. These results support Hypotheses H4a and H4b. However, the full mediating effect of supervisor attributions of the prosocial and constructive motive on the relationship between prohibitive voice and performance ratings is statistically insignificant at the 10% level.

Table 8.

Estimation results of the full mediation model.

Figure 3.

The full mediation model.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

By focusing on supervisor’s attribution of employee motives, this paper examines the impact of the employee voice on performance appraisal. We test our model’s hypotheses with 273 dyads of supervisor-employee questionnaires administered on a branch of a state-owned enterprise in China. Empirical results based on partial least squares (PLS) show that promotive voice has a significant and positive effect on supervisor’s attribution of prosocial motives and constructive motives. The promotive voice, which focuses on a future-oriented ideal state and aims to increase the “process gain” by making things better, is often viewed as an expression of “what could be” [37]. Promotive voice is more likely to be attributed to altruistic motives. In contrast, prohibitive voice is not significantly associated with supervisor’s attribution of prosocial and constructive motives. The prohibitive voice, which concentrates on the past or present-oriented factors that are harmful to organizations and attempts to prevent or reduce the “process losses”, is often viewed as an expression of “what should be”. Prohibitive voice is less likely to be attributed to altruistic motives. This suggests that supervisors are also less likely to view prohibitive voice as contributing to the sustainability of the organization.

Supervisor’s attribution of the prosocial motives and constructive motives for voice behavior is significantly associated with the employee performance appraisal in a positive direction. This suggests that, owing to the challengeable nature of the voice behaviors, supervisor’s attribution of the voice motives has a significant impact on employee performance appraisal. Moreover, the employee voice with a prosocial motive can contribute to interpersonal harmony within the organization. The employee voice with a constructive motive can make organizations work more effectively and operate in a future oriented manner. As a result, the supervisors are more likely to reward voice behaviors with prosocial motives and constructive motives.

Supervisor’s attribution of prosocial motives and constructive motives lead to full mediation of the relationship between promotive voice and employee performance appraisal. This means that promotive voice fully affects employee performance ratings through supervisor perception of the prosocial motives and constructive motives. In addition, the supervisor’s attribution of the prosocial motives and constructive motives has no mediation effect on the relationship between prohibitive voice and employee performance ratings due to the traits of prohibitive voice.

5.2. Contribution to Theory Building

Whether and how the employee voice behavior affects their performance appraisal ratings remains a debatable issue. Recent studies have developed new theories to integrate the competing perspectives and resolve the empirical puzzles [15,16]. Using the attribution theory, we contribute to the existing literature by considering the supervisor attribution of the voice motives. Our analysis suggests that owing to the difficulties in identifying the true motives of the employee voice behaviors, the supervisor’s attribution of the motives affects the relationship between the employee voice and performance appraisal. Specifically, only the voice behaviors attributed to the prosocial and constructive motives can have a positive impact on the performance rating of the employees.

To identify how supervisors attribute the motives behind the employee voice behaviors differently, we disaggregated the employee voice into a promotive and prohibitive voice. We argue that compared with the promotive voice, prohibitive voice is more challengeable in content and aggressive in tone. Therefore, it is less likely to be attributed to the prosocial motives and constructive motives.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that previous research on this issue is mainly conducted in the context of the Western culture. Since the cognition of the individuals is undoubtedly affected by their cultural traits and the Chinese cultural is very different from the Western culture, this study also deals with external validity of the existing results.

5.3. Practical Implications

The empirical analysis presented in this study shows that different types of employee voice may have different impacts on employee performance ratings due to supervisor’s attribution of voice motives. If the employees plan to change the status quo, they had better choose the promotive voice, which is more likely to be attributed to altruistic motives and also viewed as supporting the long term organizational sustainability by the supervisors. Of course, this does not mean that employees cannot voice in a prohibitive manner. If employees tend to choose prohibitive voice, they should try to make their motives prosocial and constructive in some manner, including clear framing, factual documentation and appropriate timing [25]. This strategy can help the supervisors to better understand the true motives of the employees. Additionally, employees choosing prohibitive voice should be trustworthy and professional, so that the motives behind their voice can be more clearly identified by the supervisors.

The findings of this study have important implications for the attitude of the supervisors (especially, the attitude towards the prohibitive voice of the employees). To create a good environment for employee voice and consistently obtain valuable information for decision making and organizational sustainability, supervisors should appropriately attribute the motives of employee voice behaviors. Regardless of whether employees offer suggestions in a promotive or prohibitive manner, if their motives are indeed prosocial or constructive, the supervisors should provide a positive and motivating performance appraisal to the employees.

5.4. Limitation and Future Research

The search reported in this study is a part of a small-scale research project, where the sample is drawn from a branch of a typical SOE. Future research should explore whether the results are applicable to non-SOEs. The concerns of the supervisors vary considerably across organizations and hence they may attribute the employee voice motives differently. Future research should compare the results of data collected from private and foreign-owned firms. Moreover, when examining the impact of different types of voice on performance appraisal in future studies, some information on voice, such as the context, source, message, and timing, should be controlled since these factors have been found to have some impact on supervisor’s attribution of voice motives [11]. The future research may also consider the moderating effect of variables such as the leadership style, organization climate, on the relationship between employee voice, supervisor attribution and performance appraisal. In summary, while there is no evidence of significant omitted variable bias in our study, it is highly desirable to use a larger model to re-examine the impact of employee voice on performance evaluation in China.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support received from (i) the Soft Sciences Fund of Guangdong, China (No. 2014A070703022), (ii) the Innovation Funds of Guangdong, China (No. 2014GXJK008), and (iii) the Social Sciences Fund of Guangzhou, China (No. 14G40). The authors are grateful to two reviewers for very helpful comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Author Contributions

Xiaoyan Su developed the theoretical hypothesis, collected data and wrote the paper. Yating Liu conducted the empirical analysis. Nancy Hanson-Rasmussen contributed to the literature review and language improvement. All authors read and improved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mitleton-Kelly, E.A. Complexity Theory Approach to Sustainability. Learn. Organ. 2011, 18, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Predicting Voice Behavior in Work Groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, M.R.; Oc, B. When Voice Matters: A Multilevel Review of the Impact of Voice in Organizations. J. Manag. 2014, 41, 1530–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, S.; O’Sullivan, M.; Dole, E.; Garvey, J. Employee Voice and Silence in Auditing Firms. Empl. Relat. 2016, 38, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S. Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Milliken, F.J.; Morrison, E.W.; Hewlin, P.F. An Exploratory Study of Employee Silence: Issues that Employees don’t Communicate upward and why. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1453–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D. Employee Voice Behavior: A Meta-analytic Test of the Conservation of Resources Framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, A.; Karabell, Z. Sustainable Excellence; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Transaction Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne, L.; LePine, J.A. Helping and Voice Extra-role Behaviors: Evidence of Construct and Predictive Validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, S.W.; Maynes, T.D.; Podsakoff, N.P. Effects of Message, Source, and Context on Evaluations of Employee Voice Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozionelos, N.; Singh, S.K. The Relationship of Emotional Intelligence with Task and Contextual Performance: More than It Meets the Linear Eye. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Crant, J.M. What do Proactive People do? A Longitudinal Model Linking Proactive Personality and Career Success. Pers. Psychol. 2001, 54, 845–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-K.; Yeh, R.-S.; Shih, H.-Y. Voice Behavior and Performance Ratings: The Role of Political Skill. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, E.R. The Risks and Rewards of Speaking Up: Managerial Responses to Employee Voice. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 851–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, E.R.; Detert, J.R. Speaking Up vs. Being Heard: The Disagreement Around and Outcomes of Employee Voice. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, E. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, H.H. Attribution in Social Interaction. In Attribution: Perceiving the Causes of Behavior; Jones, E.E., Kanhouse, D.E., Kelley, H.H., Nisbett, R.E., Valins, S., Weiner, B., Eds.; General Learning Press: Morristown, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Borman, W.C.; Penner, S.J. Citizenship Performance: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Motives. In Personality Psychology in the Workplace: Decade of Behavior; Roberts, B.W., Hogan, R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M.; Mayer, D.M. Good Soldiers and Good Actors: Prosocial and Impression Management Motives as Interactive Predictors of Affiliative Citizenship Behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, M.A.; Borman, W.C. Citizenship Performance: An Integrative Review and Motivational Analysis. In Performance Measurement: Current Perspectives and Future Challenges; Bennett, W., Lance, C.E., Woehr, D.J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 141–173. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.D.; Rush, M.C. The Effects of Organizational Citizenship Behavior on Performance Judgments: A Field Study and a Laboratory Experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.E.; Frez, A.; Kiker, D.S.; Motowidlo, S.J. Liking and Attributions of Motives as Mediators of the Relationships between Individuals’, Reputations, Helpful Behaviors, and Raters’ Reward Decisions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne, L.; Cummings, L.L.; McLean Parks, J. Extra-role Behaviors: In Pursuit of Construct and Definitional Clarity. Res. Organ. Behav. 1995, 17, 215–285. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne, L.; Ang, S.; Botero, I.C. Conceptualizing Employee Silence and Employee Voice as Multidimensional Constructs. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1359–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual- and Organizational-level Consequences of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The Nature and Dimensionality of Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Critical Review and Meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penner, L.; Midili, A.; Kegelmeyer, J. Beyond Job Attitudes: A Personality and Social Psychology Perspective on the Causes of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C. Citizenship and Impression Management: Good Soldiers or Good Actors? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, S.M.; Penner, L.A. The Causes of Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Motivational Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Bowler, W.M.; Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H. Organizational Concern, Prosocial Values, or Impression Management? How Supervisors Attribute Motives to Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 1450–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.; Lam, S.K.; Law, K.S. Instrumental Values of Organizational Citizenship Behavior for Promotion: A Quasi-Field Experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolino, M.C.; Varela, J.A.; Bande, B.; Turnley, W.H. The Impact of Impression Management Tactics on Supervisor Ratings of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.; Lee, T.; Wu, W. The Relationship between Human Resource Management Practices, Business Strategy and Firm Performance: Evidence from Steel Industry in Taiwan. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1351–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Farh, C.I.C.; Farh, J.L. Psychological Antecedents of Promotive and Prohibitive Voice: A Two-Wave Examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Judgments of Responsibility; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, M.; Peng, K.K.; Wong, C.S. Supervisor Attribution of Subordinate’s Organizational Citizenship Behavior Motives. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, R.S.; Wong, Y.L. Differentiating Good Soldiers from Good Actors. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 883–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofested, G. Cultural’s Consequences: International Differences in Cultural-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M. Does Intrinsic Motivation Fuel the Prosocial Fire? Motivational Synergy in Predicting Persistence, Performance, and Productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorden, W.I. Range of Employee Voice. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1988, 1, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Market. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. A Practical Guide to Factorial Validity Using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and Annotated Example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).