Abstract

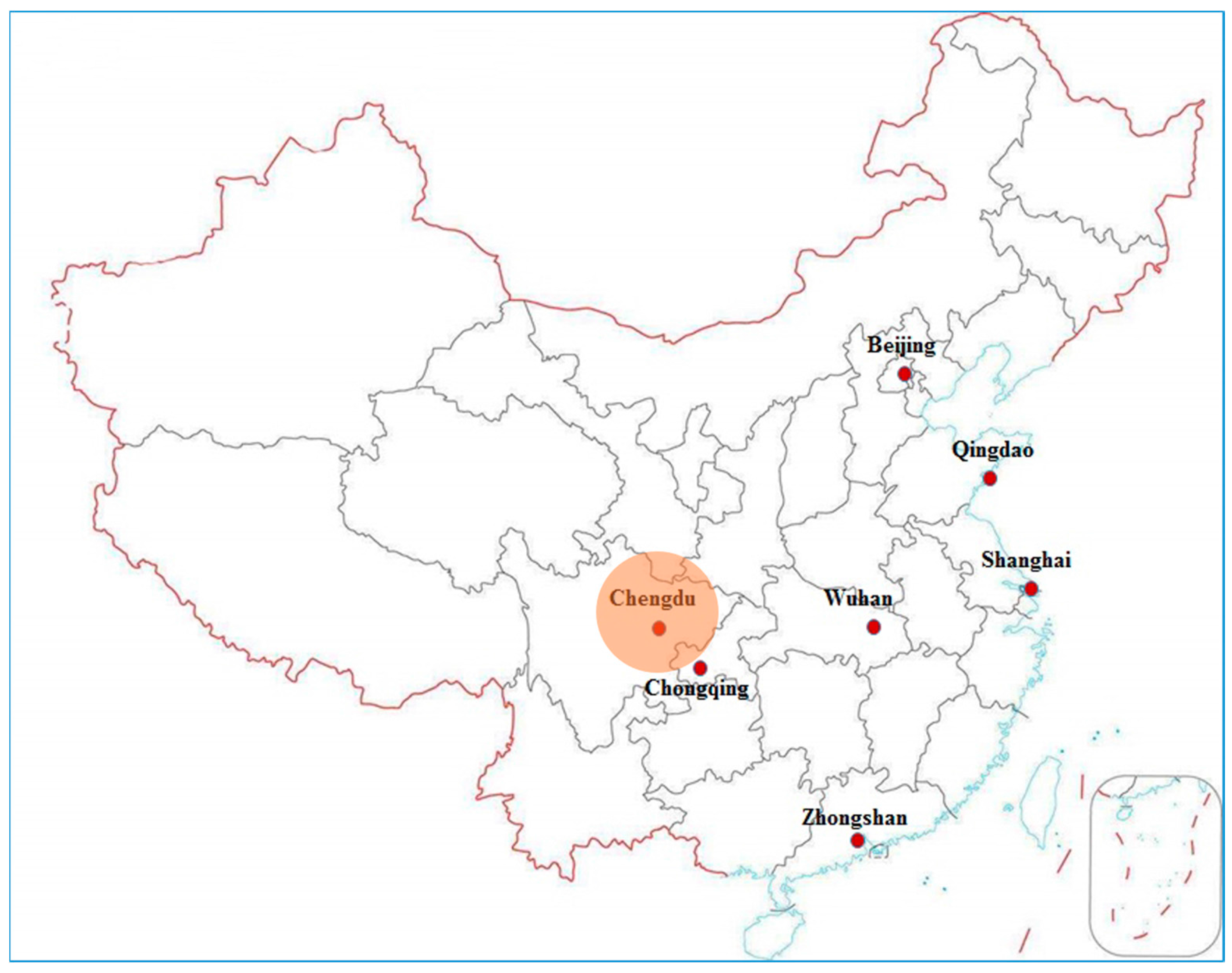

Land in rural China has been under a separate and closed management system for decades even after the urban land reform that started in the late 1980s. The blurred property rights over rural land have been hindering the rural welfare as surplus rural land in sub-urban areas cannot be circulated into more economic use without first being requisitioned by the state. This traditional conversion process creates a lot of problems, among them are the compensation standard as well as displacement of rural residents to the city, where they cannot find adequate welfare protection. The prolonged disparity in economic outcomes for rural and urban residents in China in the process of urbanisation has made the authority realise that land-based local finance is no longer an option. Coordinated Urban and Rural Development (CURD) ideology arises to set a level playing field by giving the rural residents comparable welfare status as their urban counterparts’ one. The CURD ideology is basically linked to the strategic development of the three main issues in the rural area of China, or in the Chinese terminology: San Nong. These three issues are rural villages, rural enterprises and rural farmers (nong cun, nong ye, nong min). CURD ideology is to preserve the livelihood of rural villages, facilitate and promote rural enterprises and increase the living standard of rural farmers. Most importantly, however, CURD policy package bestows rural residents with property rights over their farmland so that they could sub-co1ntract the user-rights to other urban commercial entities for higher benefits. While CURD policies are applied in a lot of different regions in China including Chongqing in the West, Qingdao in the North, Zhongshan in the South and Wuhan in the middle, we focus our examination in Chengdu as the Chengdu model has been widely documented and highly regarded as the most successful model in implementing the CURD strategies. From our case study, we find that CURD policies reduce the pressure for rural residents to migrate to the city for better job opportunities, which in turn reduce the need to expand the development scale, especially housing needs, of the urban configuration. Consequently, CURD ideology helps contribute to a more sustainable urbanisation process in China that accommodates and balances the needs and interests of both the city and rural residents.

1. Introduction

Since the advent of land use reform in China in the late 1980s, there has been a deliberate policy in place to exclude rural land from the newly created market circulation system. Among the various reasons for the country’s dual-track land use system, the protection of rural farmers’ land from excessive commercial development is a prominent one. Farmers’ benefits from and rights to the land in rural collectives play a special role in the socialist ideology important to the ruling regime. Despite the huge benefits to local economies accruing from the commercialisation of the urban land market, rural land tenure remains untouchable. Inalienable property rights remain in the hands of rural collectives whose land has no alternative use other than farming, unless requisitioned by the state via a specified process. Because of this property rights distinction between urban land and rural land, rural land on which agricultural activities no longer support the livelihood of villagers cannot easily be circulated into another land use channel, which has a detrimental impact on the income and living standards of rural inhabitants. This is rather different from other economies such as the European states, where private land ownership on agricultural land is a common phenomenon, especially with the legacies left behind from the period of feudalism and monarchies [1]. State policies therefore may have far less impact on rural development in Europe than in China. Institutional change in rural land property rights allocation therefore holds the key to the rationalisation of rural land use and management reform as well as a sustainable urbanisation process.

2. Literature Review

Urbanization is a spill-over process of urban development into rural area. This arises mainly because of the development pressure in the urban areas due to population and economic growth. Such pressure eventually leads to conversion of agricultural use of land near urban fringe into higher-density urban uses, such as commercial, industrial and residential. Even in a market system where property rights are well-delineated and land owners in the rural area are well-compensated for their land, urbanisation is not always well-received as part of the urban economic process. One of the reasons is the diminishing rural land when there is unchecked urban sprawl that may have impacts on farmers’ livelihood or even animals’ [2]. The loss of farmland for farmers is the most socially undesirable outcome of urbanisation, especially in developing economy, even though these farmers are properly compensated for the value of the land. This is because farmers may not have other skill sets to survive in the urban settings, not to mention their unwillingness to live in the relatively more crowded city environment, even though city may provide higher-pay job opportunities. Moreover, leaving their village also means the loss of social and personal networks for these rural residents who usually have a much closer tie with their neighbours compared to urban households. On the other hand, urbanisation is a natural outcome to accommodate the consequence of economic growth in the urban area, without which the continuous full factor of urban economy will lead to unacceptable high-density development as well as over- crowdedness. Urbanisation therefore makes it difficult for the livelihood of these rural residents to be undisturbed when accommodating development needs from the city’s economic expansion. Balancing urban and rural developments in a sustainable pattern therefore receives more and more attention in the recent years for its ramifications in not only the economy, but also in social policies pertaining to the fair treatment of the rural residents.

In some societies where land title and property rights on rural land are less than clearly delineated for the rural residents and farmers, urbanisation imposes a further layer of unwarranted hardship on them. Farmers who actually work on agricultural activities in these societies are usually deprived of their title to land for various reasons. Land titles therefore directly affect the living standards of rural farmers, and proper rights to the use of land have been demonstrated to be an important tool for poverty reduction [3,4,5]. According to Finan et al. [6], improving access to (the use of) land, irrespective of the size of that land, can significantly increase the welfare of rural households. A major obstacle to land accessibility, both physically and legally, is the issue of property rights. Galiani and Schargrodsky [7] regard the securing of property rights as instrumental to economic development and the alleviation of poverty. Based on data derived from a questionnaire survey, their analysis shows that land titling is a powerful and effective policy tool that allows the poor to accumulate wealth when bestowed with the ownership of land. More interestingly, land titling to these rural farmers was also shown to have an impact on the consumption pattern of households that benefit from it. The researchers documented increased investment in housing in the form of both physical improvements and an expansion in area after households had become more affluent, concluding that “… entitling the poor increases their investment both in the houses and in the human capital of their children, which should contribute to reducing poverty in future generations” [7] . From a different perspective, Ma et al. [8] make the similar observation that securing property rights helps to enhance investment in agricultural land, which leads to more sustainable rural development, although that observation contradicts an earlier study by Place and Migot-Adholla [9] who did not observe such a positive outcome. Interestingly, land titling has also been shown to weaken cooperation among farm labour [10], which might explain the possible negative impact on farm productivity. Consequently, we need to understand that there are always two sides to a coin, and examining the impact of land titling therefore needs a more focused framework.

Urbanisation is an expansionist land-based economic development process from rural areas to urban centres. On the other hand, there is also rurbanisation, especially in Europe, where expansion moves from the urban centre to rural areas [11]. In any case, land title assembly therefore is essential to this process. In the urban setting, this does not pose a major problem as long as there is a just compensation mechanism for the land taken. This is because for urban land, the end user of the land may very often not be the one who develops it. The welfare state of the land owner at the beginning is therefore not directly tied to the land per se as all the developer is concerned with is the production of real estate space on the top of the land, which he will sell or lease with the property rights over land to the end users who need such urbanised space for various socio-economic activities in a relatively compact mode. Rural land on the other hand is quite different, where the welfare of the land users—farmers—is inevitably linked to the land he owns, as he constantly recycles agricultural production function on his farmland. Even with just compensation on the value of land, rural land users’ welfare will be negatively affected if they cease their agricultural production, both socially and economically. In addition, relocation is not easy or even feasible compared to their urban counterparts in order to maintain their welfare.

Given the importance of land title to the welfare of rural farmers, urbanisation can produce more sustainable outcomes that benefit both urban and rural residents if urbanisation process can take into consideration an option of expanding urban economic activities beyond urban fringe without the need for rural residents to forfeit their land title on rural land. The current attempt by the Chinese government to balance the disparity between urban and rural development under the Coordinated Urban and Rural Development (CURD) strategic and ideological plan matches this objective. The CURD ideology is basically linked to the strategic development of the three main issues in the rural area of China, or in the Chinese terminology: San Nong. These three issues are rural villages, rural enterprises and rural farmers (nong cun, nong ye, nong min). CURD ideology is to preserve the livelihood of rural villages, facilitate and promote rural enterprises and increase the living standard of rural farmers. While CURD is a comprehensive welfare policy target aiming at elevating the welfare standard of the rural residents, an important machinery designed under CURD direction is the land title reform that facilitates a much more flexible circulation of rural land that accommodates the needs of urban economy as well as the welfare of the rural residents. In this paper, we will therefore concentrate on the land-based aspects of CURD strategies in order to examine how a new model of urbanisation process in China takes into account sustainable development.

Urbanisation and Rural Land Development in China

Urbanisation in China started with the growing upward trend of economic development that benefits from the economic reforms in the late 1970s. Urbanisation in China since then has taken an enormous step in this nation following high-speed economic growth, structural changes as well as influx of foreign investment [12]. However, economic growth in China does not impact the urbanisation process all over the nation evenly. Administrative intervention policies account more for the urbanisation progress, especially between coastal and inland cities [13]. Not only are administrative measures important in making the regional discrepancy in urbanisation process in China, they are also the main factor fostering landed-local finance in this process. This is because of the administratively divided property rights and land management systems between urban and rural land in China. Because rural land belongs to rural collectives, and cannot be developed until requisitioned by the city government, it gives the city government a chance to absorb the appreciated land value in rural areas if they choose to, before converting such rural land and selling it to private developers. This landed-local finance has provided a major source of income for a lot of local authorities, but at the same time has also created grievances among the rural residents.

Landed property is an important capital source of wealth accumulation, particularly for rural inhabitants whose major earnings are linked to the direct use of the land. Consequently, the right to use land is a determining factor in the enjoyment of income from land. Market-oriented strategic planning that enhances the role of the land economy in urban areas is regarded as an important step towards achieving significant economic outcomes for China [14,15]. However, such strategic planning has not been applied to the country’s rural land owing to the existence of inalienable property rights to the land of rural collectives.

The property rights arrangements governing rural land constitutes an important, albeit delicate, topic within the overall subject of urban land reform in China, as land expropriation in rural villages is a complicated issue [16]. Such expropriation by local governments is regarded as a primary factor in farmers’ poverty, which has forced many into the cities during the large-scale urbanisation of China [13]. The allocation of land to rural farmers is therefore instrumental in their welfare [17]. Reforming the rural land use system within the dual-track land use rights mechanism that differentiates between urban and rural land in terms of property rights is essential to eliminating the widening gap between urban and rural living standards [18]. Starting with the experiment in shareholding enterprise reform in rural collectives [19], one can see the central government’s resolve to tackle the core issue, namely, the institutional arrangement for rural property rights, gradually. CURD represents a start, with both the market system and actors who are active on the investment side of land development being introduced, ostensibly to facilitate rural farmers’ change of residence [20]. Under the general principle of the CURD strategy that stresses coordinating developments between rural and urban settings, experiments in a number of cities have shown that a CURD policy package that allows rural farmers to exchange residential land for commercial purposes can allow idle rural land to circulate back into the market land use system and improve rural living standards [21]. Accordingly, this strategy seems to have fostered a sustainable rural land use model that is receiving increasing academic attention [22]. A market system that is beginning to achieve a more efficient circulation system for rural land is taking shape [23].

3. Coordinated Urban–Rural Development (CURD) in China

The long-term dual urban–rural land tenure structure in China has led to obvious gaps in income, social welfare and public services between urban and rural residents. Compared with urban regions, rural regions lack investments, infrastructure and economic reform, which has restricted rural economic development and widened the gap between urban and rural development. Part of the reason for this outcome is the over-reliance on landed-revenue by the local governments in China. In the past, most local governments chose to requisition rural land at a relatively low compensation level, then they would convert collective land into state land before circulating it into the open market for huge economic gains [24]. However, this approach led to disputes with rural residents as well as unfairness, in addition to market risks resulting from the variations in the land market.

To alleviate this imbalance in the process of property-led urbanisation, the Chinese government proposed the aforementioned CURD strategy in 2002. CURD is based on the previous Three Concentrations policy guide (which currently has ceased to exist and has been rephrased as the New Model of Urbanisation, Xinxing Chengzhenhua, for some political reasons beyond the scope of this paper). The “Three Concentrations” means concentration of industries on industrial zone; rural farmers to concentrate on the urbanised fringe area and move to newly built housing compounds developed by the authority; and land development to be concentrated and intensified on designated areas (which is the focus of this project). CURD’s principal aim is to minimise the long-standing urban–rural disparity in economic development, land use market structure, living standards and social infrastructure. CURD is in effect a very comprehensive rural reform package that encompasses two main aspects. Firstly, CURD is designed to enhance the social welfare for the rural residents. In the past, due to the differential treatment between city and rural residents created by the household registration (Hukou) system, rural residents lack the social insurance and low-income welfare support that are available to their city counterparts. Such a situation is worsened by the lack of physical infrastructure due to the scattered living arrangement of the rural residents. Secondly, CURD is about mobilising a major factor of production of the rural residents—land—into more productive and rewarding use. In the past decade, many reform policies have emerged to support and enhance CURD. It is hoped that the boundary between rural and urban economies will become increasingly less distinct, meaning that national and regional planning do not need to be segregated into two sets. Ultimately, it is hoped that a more sustainable model of urbanisation can be established in China.

In 2007, the National Development and Reform Commission of China approved the establishment of two pilot regions for further experimentation in executing reform packages under the CURD strategy: Chongqing and Chengdu (see Notice of the National Development and Reform Commission on allowing (the establishment of) pilot region for comprehensive reforms of coordinated urban and rural development in Chongqing and Chengdu).

In 2009, the government issued more intensive and preferential policy packages to support the CURD strategy in the five following ways: (1) allocate more national resources, capital and subsidies to the countryside, as well as a preferential finance policy, to support rural development; (2) encourage a transformation from traditional agriculture to modern agricultural activities, including the adoption of standardised agricultural production methods, construction of water conservancy infrastructure, encouragement of innovation in agricultural technology and regulation of the agricultural market; (3) increase investment in the construction of infrastructure and provision of public services and a social welfare package in rural areas to improve the quality of life; (4) accelerate the speed at which the urban–rural dual structure is changed to stimulate rural economic development by, for example, reforming rural land management and accelerating urbanisation; and (5) improve rural governance and maintain rural stability. It is the fourth measure, namely, reforming rural land management, which this project will focus on.

One of the key issues in CURD is protecting agricultural land while maximising the efficiency of both urban and rural land use mechanism. According to the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) Land Administration Law, there are two main kinds of rural land in China—cultivation land, which is contracted by farmers for agricultural use, and rural collective construction land. Reforming the ownership of rural collective land and circulating rural land are important issues in the overall CURD strategic arrangement. Under the general rationale of the CURD strategy, it is hoped that the land use rights structure between the urban and rural land use markets will be unified to ensure that the circulation of rural land proceeds more efficiently and land income can play a similar role in lifting rural living standards as it did in lifting urban living standards, and hence making urbanisation more sustainable for the rural residents.

The circulation of rural land includes the transfer of management rights to rural land and the transfer of usage rights to rural collective construction land. The Land Administration Law allows the transfer of management rights to rural cultivation land to achieve large-scale management and enhance productivity. The transfer of usage rights to rural collective construction land is playing an important role in the urbanisation process. In 2013, the Chinese government opened up the rural collective construction land market for sale and leasing in a way similar to the market for state-owned land as part of a strategic move under the CURD policy.

4. Chengdu: A Successful CURD Model

4.1. Basic Information on Chengdu

Chengdu is the capital of Sichuan Province in southwest China, and is the most important economic, financial, commercial, cultural and transport hub in western China. Chengdu is the eighth largest city in mainland China, with a geographical area of 12,390 km2, including a 1418 km2 metro area, five city core districts, four suburban districts, four satellite cities and six counties. The municipality is home to 14.3 million inhabitants, according to the 2014 census, 9.92 million of whom live in urban areas and 4.38 million of whom live in rural areas. Chengdu has witnessed fast-paced urbanisation since the implementation of CURD policies in 2003, with the urbanisation rate jumping from 57.52% in 2003 to 69.4% in 2013, higher than the national rate (53.7%) in that year.

4.2. Rural Land Reform and CURD in Chengdu

From 2003 to 2007, the Chengdu government invested a huge amount of capital into relocating farmers to urban areas, albeit without much success. In 2008, the government implemented a policy to accelerate the urbanisation process and reduce the gap between urban and rural citizens by reforming the rural land system, with a focus on the registration and confirmation of rural land rights and the circulation of rural land in the open market. Under the guidance of that policy, the Chengdu government has carried out experiments of rural land property rights reform in Dujiangyan, Wenjiang, Shuangliu, Dayi and 14 other counties. The foundation of that reform is the registration and confirmation of rural land and property ownership, with farmers issued certificates giving them the right to carry out the contracted management of their rural land. Then, based on the registration and confirmation of rural land and property ownership, that land can be circulated in the open market effectively and efficiently. With the success of these trials, CURD in Chengdu currently covers all rural prefectures, including both the sub-urban and remote ones.

With regard to rural collective land and property, farmers can operate rural tourism businesses or engage in other types of commercial activities themselves or lease their land to rural collective economic organisations and work for them to obtain both leasing and employment income [25]. Such a scheme was first experimented with in Longhua Village and Sansheng Village. With regard to rural farmland, farmers can transfer the management rights to their farmland to rural enterprises or rural collective economic organisations, which in turn manage and operate that land, or they can subcontract or lease it to a commercial operator for better land use, thereby increasing farmers’ income from land circulation and from working. By the end of 2014, 2308 million km2 of rural cultivated land was in circulation and 54.1% of farmland was being used in one of the aforementioned ways.

In the past decade of CURD strategic development, farmers’ quality of life has improved significantly. For example, in Shuangliu Prefecture, the local government has constructed residential districts for rural farmers that provide a better housing environment and more facilities than what they had previously and have achieved the effective and intensive use of rural housing land. Rural residents’ annual total per capita income increased from RMB ¥5252.76 in 2003 to RMB ¥7752.80 in 2007 and to RMB ¥16,806.29 in 2013 (In 2003, the exchange rate between US dollars and RMB yuan was 1:8.27. In 2007, it was 1:7.6. In 2013, the exchange rate dropped to 1:6.19.). The gap in annual income between urban and rural residents has also narrowed from 2.28:1 in 2003 to 2.06:1 in 2007 and to 1.93:1 in 2013. The education level of rural citizens, too, has undergone obvious enhancement, with the proportion of those obtaining at least a junior high school diploma increasing from 70.3% in 2003 to 78.75% in 2013.

In 2003, Chengdu started to implement reform policies targeting more efficient rural land use under the general guidelines of the CURD strategy. The Chengdu government issues certificates of usage rights to rural land to each rural inhabitant certifying that they hold the right to use, transfer and enjoy income from that land. This is the so-called land titling policy. Since 2008, land titling has been implemented in such a way that land titles are assigned back to rural villagers to effectuate transfers after a government survey was conducted to delineate boundaries. In March 2008, the first land title was issued in Heming Village. It is not surprising that disputes have arisen over the boundary delineation. The Chengdu authorities have resorted to negotiation via village council meetings in which villagers discuss various issues of concern and resolve differences concerning boundary delineation before official recognition by the government. By the end of 2010, land ownership titles had been assigned to more than 33,800 rural collectives. Almost 1.8 million households obtained new titles to their agricultural land under the Household Responsibility System. In addition, 1.66 million households received titles to construction land classified as either “housing land” or “other types of rural construction land.” Land titling now covers most rural areas in Chengdu.

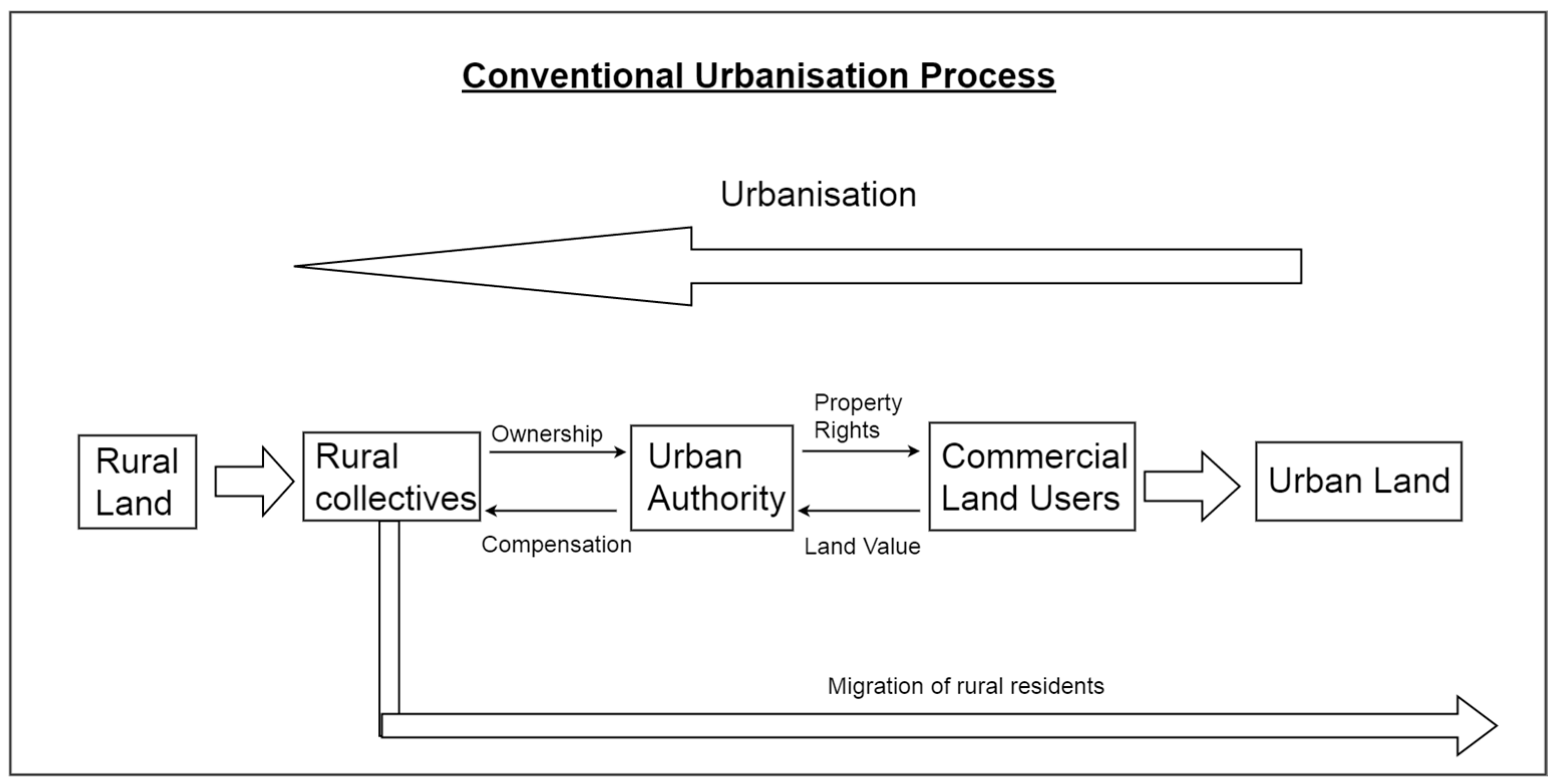

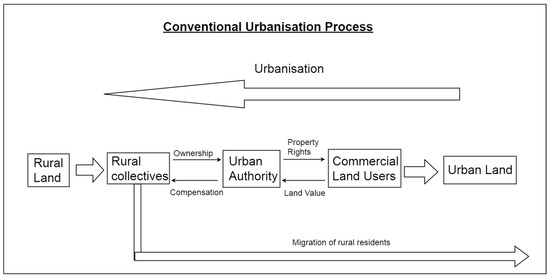

To conceptualise such policy change brought about by the CURD ideology, the following two models are illustrated.

Figure 1 shows the conventional urbanization model when rural/agricultural land is being encroached. In Figure 1, we can see that under conventional urbanization process, urban boundary is being pushed outwards, encroaching rural land due to development pressure. In this process, commercial land users, usually the real estate developers, are the main actors in converting rural land into urbanized commercial land either for residential, resort or business-oriented purposes. This conversion is physical and one way, meaning existing rural owners of such land are compensated one way or the other and displaced from the ownership as well as the use of such land afterwards. Land in rural China broadly belongs to village collectives, which have three major categories of stakeholders in the governance arrangement, namely township, villages and villagers. There is no express stipulation on how to allocate the property rights to each of these stakeholders by law. Rural residents lack the legal title to dispose land. The rights to dispose land is the core of all property rights and a significant indicator of an efficient circulation system for land in the rural areas. Farmers are prohibited from transferring rural land owned collectively by law, and they only have the rights of disposal through village collectives. A direct consequence of this is rural-to-urban migration of these rural residents, as the loss of rural land deprives these rural residents from their basic tool of production. However, due to the problem of the urban household registration system, these rural migrants cannot enjoy the same level of social benefits their urban counterparts have in the city. Under such urbanization process, rural residents receive double penalty in terms of welfare and therefore become the main victim in China. The issue therefore hinges on solving the obscured property rights over rural land and the status of household registration. On the other hand, from land administration’s point of view, this conventional model also produces some problems. First of all, because the local government is the only entity to convert rural land, it increases unnecessary conflict and negotiation between the authority and rural farmers over compensation and re-settlement issues [16]. On the other hand, because of the potential financial gains in this process, it also opens up opportunity for corruption. The advent of the CURD ideology targets these problems with a core element of granting land title back to the individual rural owners.

Figure 1.

Conversion of rural land into urban land in the process of urbanisation in China.

Under the CURD ideology, it is hoped that the following socio-economic benefits can be brought to the rural residents:

- -

- To improve economic gains for the rural residents in combined ways, including rental income of the long lease on their own farmland (or in cases where the rural residents decide to sell, capital value); dividends on the economic return to be generated on their land and formal salaries for working on the new enterprise is to be setup on their land;

- -

- To allow technical and knowledge transfer for the rural residents once they are employed as part-owner and part-worker by the new enterprises. This enables them to learn commercial skills to continue with the viable business on their site once the long lease expires;

- -

- To allow for formal social insurance and security packages to be offered to the rural residents once they are formally employed by a business enterprise;

- -

- To provide urban Hukou (household registration) to the rural residents once they join the CURD package, and this entitles them to such urban benefits as medical and education;

- -

- To enhance personal satisfaction and self-esteem of the rural residents when their living standard is being raised.

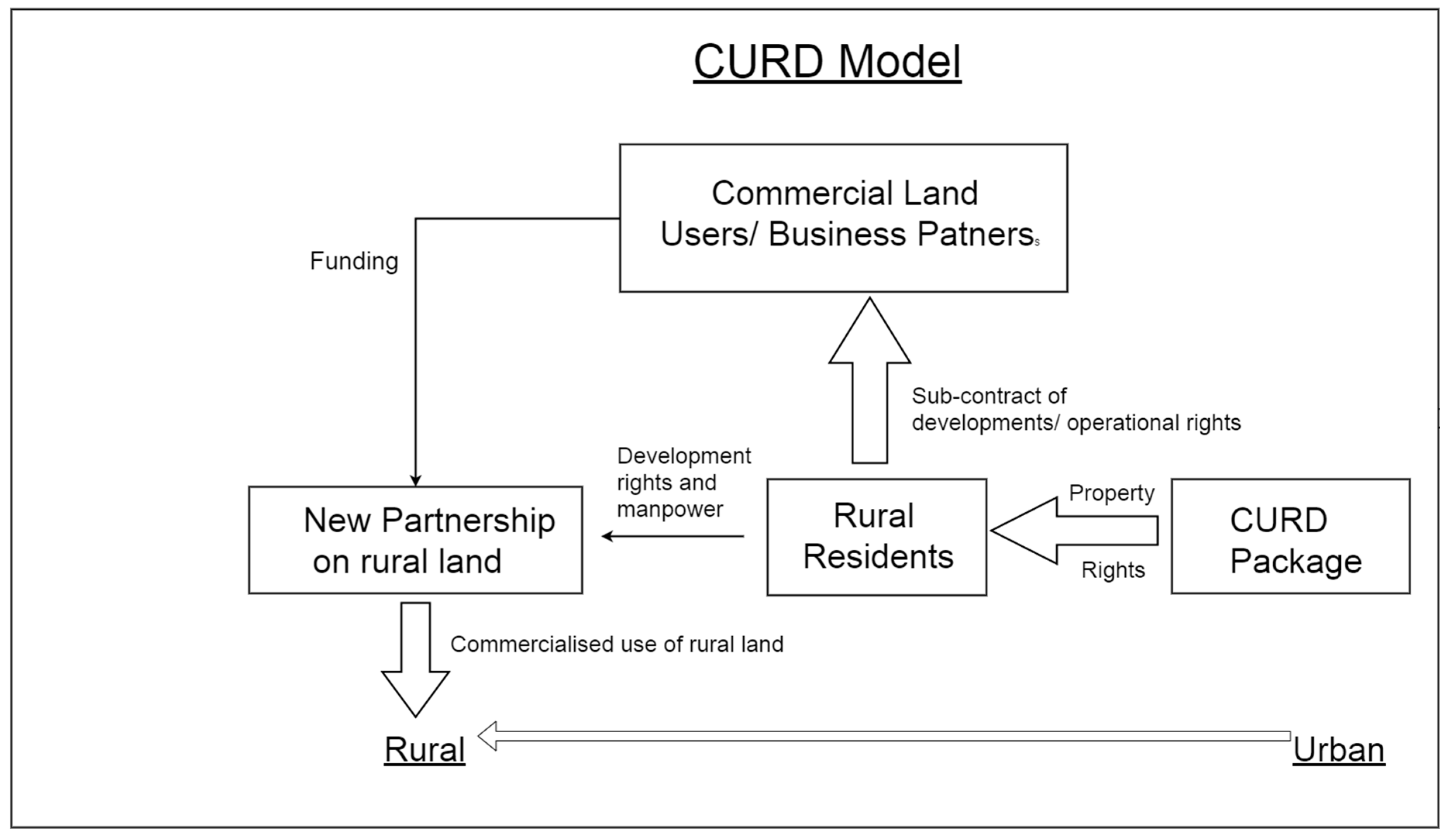

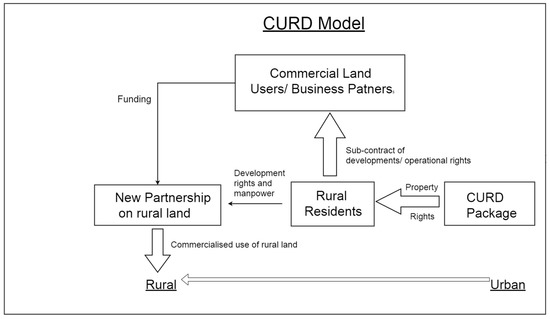

Figure 2 illustrates this transformation under the CURD ideology. As mentioned above, the ideology of CURD evolves around improving the three core issues in the rural areas, which eventually aim at alleviating the livelihood of rural residents in China. Since the farmers in the rural collectives are living in a closely knit community, issuance of property rights certificates was completed within a short period of time and in an efficient manner that allowed the rural farmers to experiment other alternative use of their land without major problems. In terms of governance of the land tenure system, the CURD policies allowed for a smooth transition to convert rural land into more commercial use without the hassles of land requisition and compensation negotiation. This also minimised political risk for the local authority. Property rights on rural land are now more clearly defined and transferrable that makes circulation of surplus rural land into commercial use feasible. In the end, rural farmers are able to utilise their surplus farmland as a means for wealth accumulation in a similar manner as their urban counterparts. From the figure, we can see that the CURD ideology aims at facilitating a more sustainable urbanisation process that will raise the living standard and welfare state of the rural residents by giving them full legal title on land, which they can utilise as capital to accommodate economic expansion of urban activities.

Figure 2.

Coordinated Urban and Rural Development (CURD) model of urbanisation in China.

These benefits are to be delivered via the following policy/operational principles:

- No land requisition and no compulsory purchase of land to be initiated; apply the core principle of “Farmers leave their land without leaving their village (li tu bu li xiang)”;

- Using commercial enterprises to support rural economy;

- Rural farmers enjoy equal social benefits as their urban counterparts.

With the implementation of CURD policies, rural residents were given the property rights certificate on their farmland as elaborated above. To accelerate urbanisation and the relocation of rural villagers, the Chengdu government reorganises rural land (mainly building land) and issues certificates of ownership and usage rights for collective land and property and offers subsidies to these rural residents in the countryside to construct housing villages with higher intensity and concentration of residents. In this way, physical and social infrastructure can be provided by the government to these residents in a more efficient way in the rural areas. Upon receiving the property rights on their land, rural residents can operate tourist-oriented businesses or other types of commercial activity such as commercial gardens/fruit farms (nongjiale) for urban residents in joint venture with business entities which provide funding and management expertise in return for a management lease on the land. Trial farms have been established in Longhua Village and Sansheng Village. Alternatively, rural villagers can choose to live in urban areas and enjoy the same rights and social welfare as other urban citizens by voluntarily giving up both management rights to rural land and usage rights to construction land. The rural land that is returned is managed by the city government and operated by rural collective economic organisations. An example can be found in Wenzhou, Chengdu.

To a very large extent, CURD policies help to improve the governance structure of the complicated rural land tenure system in China. The most significant result is the circulation of surplus rural land into more efficient commercial use without the unnecessary conflicts in the requisition process. While the local government may not have the access to the potential financial gains in the conversion process of rural land to urban construction land as they enjoyed in the past, they now find less political risks in developing rural areas for high-value commercial activities such as catering or tourism which will also eventually bring in tax income for them. More importantly, there is now less pressure in dealing with the influx of displaced rural farmers in the urban areas, which also alleviates such urban problems as crime and demand for welfare housing. On balance, local authorities find it a harmonious approach to sustain long-term economic growth for the whole district, and “harmony” is always a keyword for success as far as local governments are concerned.

With the property rights over their land being ascertained, most rural residents choose to sub-contract the use-rights of their land for commercial uses that cater to the socio-economic needs of their urban counterparts so that they would not need to leave their village and their own social network. This fulfills the operational principle of “li tu bu li xiang” described above. With the aim of intensifying the utilisation and operation of rural cultivated land, the Chengdu government has proposed that farmers be able to transfer management rights to contracted farmland to rural enterprises or rural collective economic organisations, which take responsibility for managing and operating them on a larger scale via subcontracting, leasing or demutualising, thereby boosting farmers’ income through land circulation and employment. Hence, instead of physically converting agricultural land into residential or commercial space, CURD allows the rural residents to be temporarily separated from the ownership of such land, which will then be leased to a commercial entity for such purposes as restaurant, resort or a hybrid of commercial farm and restaurant (i.e., nongjiale). These leases on the use of land (usually around 30 years) enable urban commercial entities to tap into rural resources without the need to take over their property rights on such assets and compensate them, especially land. In return, the rural land owners obtain rental income on their land, job opportunity with these new operators, management skills in running commercial entities on their own land, and an increase in welfare.

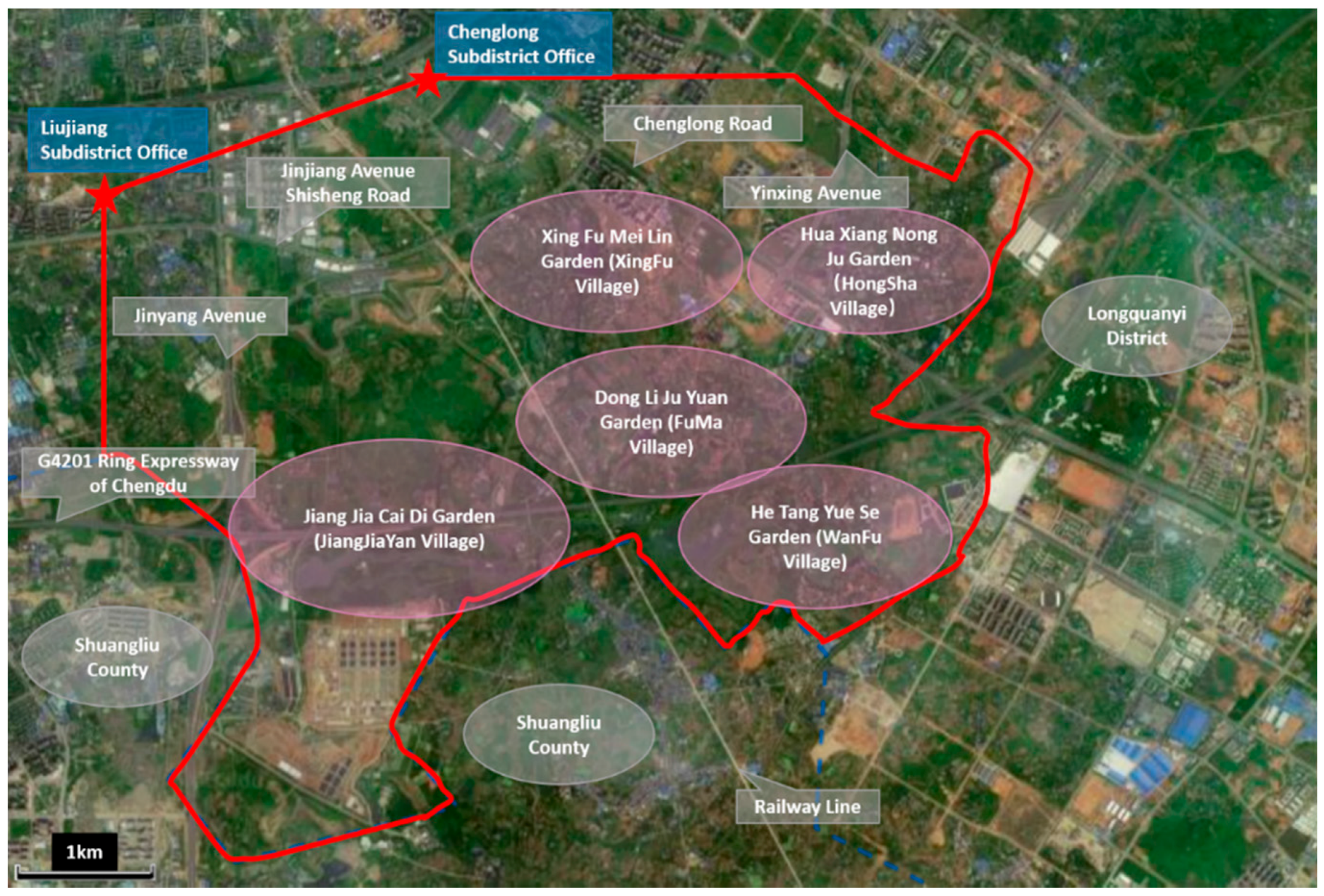

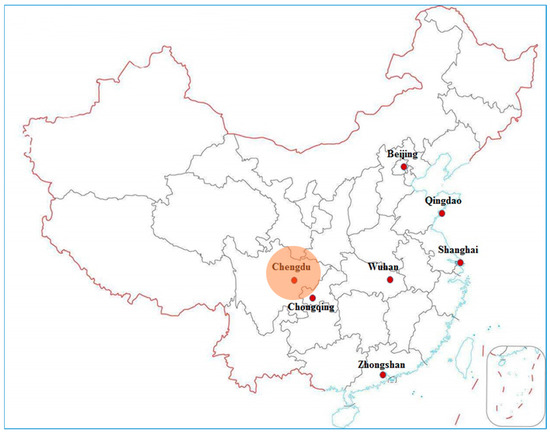

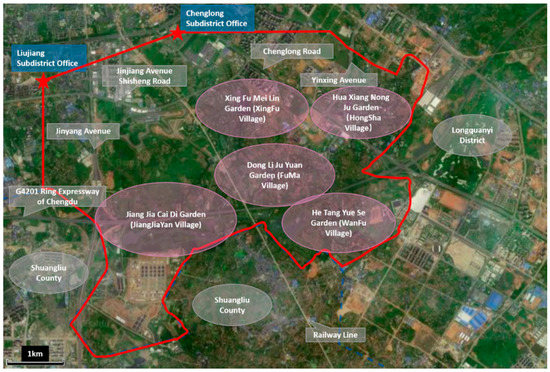

An example to illustrate this outcome is the Sansheng Flower Village development. Sansheng Flower Villages is a cluster of five villages in Jinjiang District of Chengdu, which is the northeastern part of Chengdu (Figure 3 and Figure 4). These five villages are Hongsha Village, Xinfu Village, Jiangjiayan Village, Fuma Village, and Wanfu Village (Figure 5). The total area of this cluster is about 12 km2. They are called flower villages because of a major flowers exhibition held in Hongsha village in 2003. Since then, the other villages took turn in organising this event, and eventually, this cluster of villages earned the title of Five Golden Flowers, and hence the name Sansheng Flower Villages. According to government record, by the end of 2013, there was a total rural population of 27,410 living in this cluster. Per capita annual income at that time was about 19,921 Yuan (almost a three-times increase from the year 2004 at 6080 Yuan).

Figure 3.

Geographical Location of Chengdu city.

Figure 4.

Locational Map of Sansheng Flower Village Complex in Chengdu.

Figure 5.

Configuration of the Sansheng Flower Village Complex.

From our survey on Sansheng Flower Villages, we notice that most of the original farmland in the complex has been turned into commercial operations of all sorts. Part of the farm plots have been converted into commercial farmland for selling indoor and outdoor plants for city dwellers. A significant part of the complex has also been turned into catering/resort/conference facilities (Figure 6) that target various leisure and commercial activities extending from the urban centre. On the other hand, a not insignificant part of the Sansheng Flower village site remains as tranquil rural residential land occupied by these rural residents who either work on these converted commercial facilities or lease out their land to their urban partners (Figure 7). Hence, it fits exactly the principle of “leaving the farmland without leaving the village”.

Figure 6.

Commercialised uses of farmland on Sansheng Flower Village Complex.

Figure 7.

Non-converted of farmland on Sansheng Flower Village Complex.

For the city government, this also allows a much more efficient and sustainable urbanisation process to be carried out, as rural residents who scattered around in the rural area in the past are now more centralised in the new developments. Urban residents can now also access sub-urban and even more remote rural land for social and economic activities.

Subsequent to the land titling initiative, six pertinent policy documents were issued by the local government. A “land for new housing” policy was established in 2008/2009 whereby rural homeowners who want to transfer their land first need to obtain titles for their housing land. Upon receipt of those titles, they are free to find an investor/financier to provide them the capital to build a new house elsewhere. As long as the land area occupied by their new house is smaller than that of their old housing land, as shown on the title, the housing land can be transferred to an investor for such “business” uses as tourist resorts and restaurants. The contract for such a transaction is signed not only by the original housing land owner and the investor, but also by the head of the collective, which is the land’s legal owner. This policy therefore bestowed transfer rights to rural construction land for the first time. Under its terms, investors who are not members of the respective rural collective or village can be granted land user rights for 40 or 50 years.

Generally speaking, the Sansheng Flower Village case shows that urbanisation comes to an amiable convergence with the rural area. The physical boundary between urban and rural still exists, but the functional boundary is being merged (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Convergence of urban and rural boundary at Sansheng Flower Village Complex.

5. Conclusions

Ever since the urban land reform started in China in the late 1980s, urbanization has been accelerated at an increasing speed. Urban land has since then become a highly valuable financial asset (For example: http://www.scmp.com/property/hong-kong-china/article/2005041/shanghai-land-sells-100000-yuan-sq-m-highest-price-ever), especially for the local governments [26]. Urbanization therefore creates an opportunity for some local authorities to accumulate land-based incomes through converting rural land into state land with relatively low compensation standard because of the blurred property rights on rural land described above [27]. This is not regarded as a healthy development in the urbanization process as discontent among rural residents has been snowballing in the last decade. In addition, the unbalanced social benefit arising from the urban household registration system also creates hardship for the rural migrants living in the city. Eventually, creative measures that aim at promoting a more sustainable urbanization process as well as elevating the welfare state of the rural residents are in demand, and CURD ideology is one of the more successful packages.

The core element of the CURD ideology is to allow property rights to be granted to the individual owners of the rural land, and to allow such rural land to be circulated into a market system that provides a more optimal use, without the need of requisition by the state authority. It is hoped that such a policy package allows rural farmers to stay in rural land while enjoying a basic welfare package to which all other urban residents are entitled. In so doing, it will reduce the pressure of rural-to-urban migration, and hence the pressure on urbanization. The case study of Chengdu shows that land title on rural land remains instrumental in contributing to a sustainable urbanization process in China. In fact, the CURD ideology represents an important milestone in the overall property rights reforms over land in China, especially in the rural setting. CURD represents a new policy direction that allows economic activities arising from urban development to be extended into rural land without massive urban land development, based on the principle that rural residents now have a larger degree of flexibility of using their land commercially. This reverts wealth arising from urbanization back to the rural residents. While there are also other non-land-based CURD welfare policies, without a doubt, land title commands an important role in achieving such results and re-distributing property rights back to rural residents. CURD ideology is a flexible model of dealing with blurred property rights in rural China that allows rural land to be circulated into higher-return use. This represents a more sustainable urbanisation process through which some economic activities could be carried out on rural land without massive conversion of agricultural land into building land. More importantly, rural residents are able to retreat from agricultural activities without having to depart from their rural life while enjoying elevated social welfare as well as economic gains. CURD policies therefore reduce the pressure for rural residents to migrate to the city for better job opportunities, which in turn reduce the need to expand the development scale, especially housing needs, of the urban configuration. To this end, CURD ideology helps contribute to a more sustainable urbanisation process in China that accommodates and balances the needs and interests of both the city and rural residents.

Acknowledgments

This paper was financially supported by the Hong Kong University Seed Fund for Basic Research 2016 Project Number 1004004254.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nagle, J. Feudalism, Monarchies, and Nobility; Rosen Educational Services: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Filippi-Codaccioni, O.; Clobert, J.; Julliard, R. Urbanisation effects on the functional diversity of avian agricultural communities. Acta Oecol. 2009, 35, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorner, P. Latin American Land Reforms in Theory and Practice: A Retrospective Analysis; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, H.; Deininger, K.; Feder, G. Power, distortions, revolt, and reform in agricultural land relations. In Handbook of Development Economics; Behrman, J., Srinivasan, T.N., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Broegaard, R.B. Land access and titling in Nicaragua. Dev. Chang. 2009, 40, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finan, F.; Sadoulet, E.; de Janvry, A. Measuring the poverty reduction potential of land in rural Mexico. J. Dev. Econ. 2005, 77, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiani, S.; Schargrodsky, E. Property rights for the poor: Effects of land titling. J. Public Econom. 2010, 94, 700–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Heerink, N.; Ekko, V.I.; Van, D.B.; Shi, X. Land tenure security and land investments in northwest China. China Agri. Econom. Rev. 2013, 5, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, F.; Migot-Adholla, S. The economic effects of land registration on smallholder farms in Kenya: Evidence from Nyeri and Kakamega districts. Land Econ. 1998, 74, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, E.M.; Lesorogol, C.K. The impact of land privatization on cooperation in farm labor in Kenya. Hum. Ecol. 2012, 40, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehin, J.B. La périurbanisation et la rurbanisation à travers la consommation d’espace. BSGLg 1998, 34, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.H. What explains China’s rising urbanisation in the reform era? Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2301–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, X.; Lo, K. Measuring sustainable urbanization in china: A case study of the coastal Liaoning area. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, J. Planning the competitive city-region: The emergence of strategic development plan in China. Urban Aff. Rev. 2007, 42, 714–740. [Google Scholar]

- Phat, N.T. Administrative reforms of rural land in transition economies: An example in China and Vietnam. Sociol. Mind 2013, 3, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Webster, C. Land dispossession and enrichment in China’s suburban villages. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S. Economic reform and household welfare in rural China: Evidence from household survey data. J. Int. Dev. 2000, 12, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Westen, A.C.M. Land in China: Struggle and reform. Development 2011, 54, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yep, R. The evolution of shareholding enterprise reform in rural China: A manager empowerment thesis. Pac. Aff. 2001, 74, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Deng, L.; Gao, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L. Rural housing land consolidation and transformation of rural villages under the “coordinating urban and rural construction land” policy: A case of Chengdu City, China. Low Carbon Econ. 2013, 4, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Xu, Y. Exchange of rural residential land in China. Asian Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Li, F. Land consolidation: An approach for sustainable development in rural China. Ambio 2011, 40, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Ai, Y. Capitalism without capital: Capital conversion and market making in rural China. China Q. 2014, 219, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Cao, S. The land finance model jeopardizes China’s sustainable development. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- School of Scientific Development Research Sichuan University; CURD Committee of the Chengdu City Government. Annual Report on Chengdu Balanced Rural and Urban Development (Chengdu Tong Chou Cheng Xiang Fa Zhan Nian Du Bao Gao, 2014); Sichuan University Press: Chengdu, China, 2014.

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Huang, L.; Tang, X. Urban residential land value analysis: Case Danyang, China. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2007, 10, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, S. Values in land: Fiscal pressures, land disputes and justice claims in rural and peri-urban China. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).