Linking Transitions to Sustainability: A Study of the Societal Effects of Transition Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Assessing the Societal Effects of Transition Management Processes

2.1. Societal Effects of Transition Management and Transdisciplinary Sustainability Research

- (1)

- Outputs in the form of usable products such as (innovative) goods, services and action plans or publications as well as production-related experiences of participants.

- (2)

- Impacts in the form of

- Enhanced capacities such as knowledge gains and problem-solving capacities and

- Network effects, such as new relationships, trust or accountability.

- (1)

- The first category refers to the creation of usable products as a concrete and tangible output of solution-oriented sustainability research, which in design, production and delivery themselves should be oriented towards sustainability principles [45]. At the very least, in transition management processes, vision documents and related pathways are produced [32]. The processes can also lead to other artefacts, such as websites (see e.g., www.lebensklima.at, the website of one of the case studies) or new products (e.g., a floating building, cf., [47]) and services (e.g., a public lecture series on participation and sustainability, cf., [48]). The intensity (quality and frequency) of being involved in creating products and having experiences can be seen as an indicator for the creation of impacts such as enhanced capacities and network effects [46]. Experiences may include methodological experiences and organizational experiences, such as experiencing new ways of working, planning and organizing as well as social experiences, such as interactions with others [44].

- (2a)

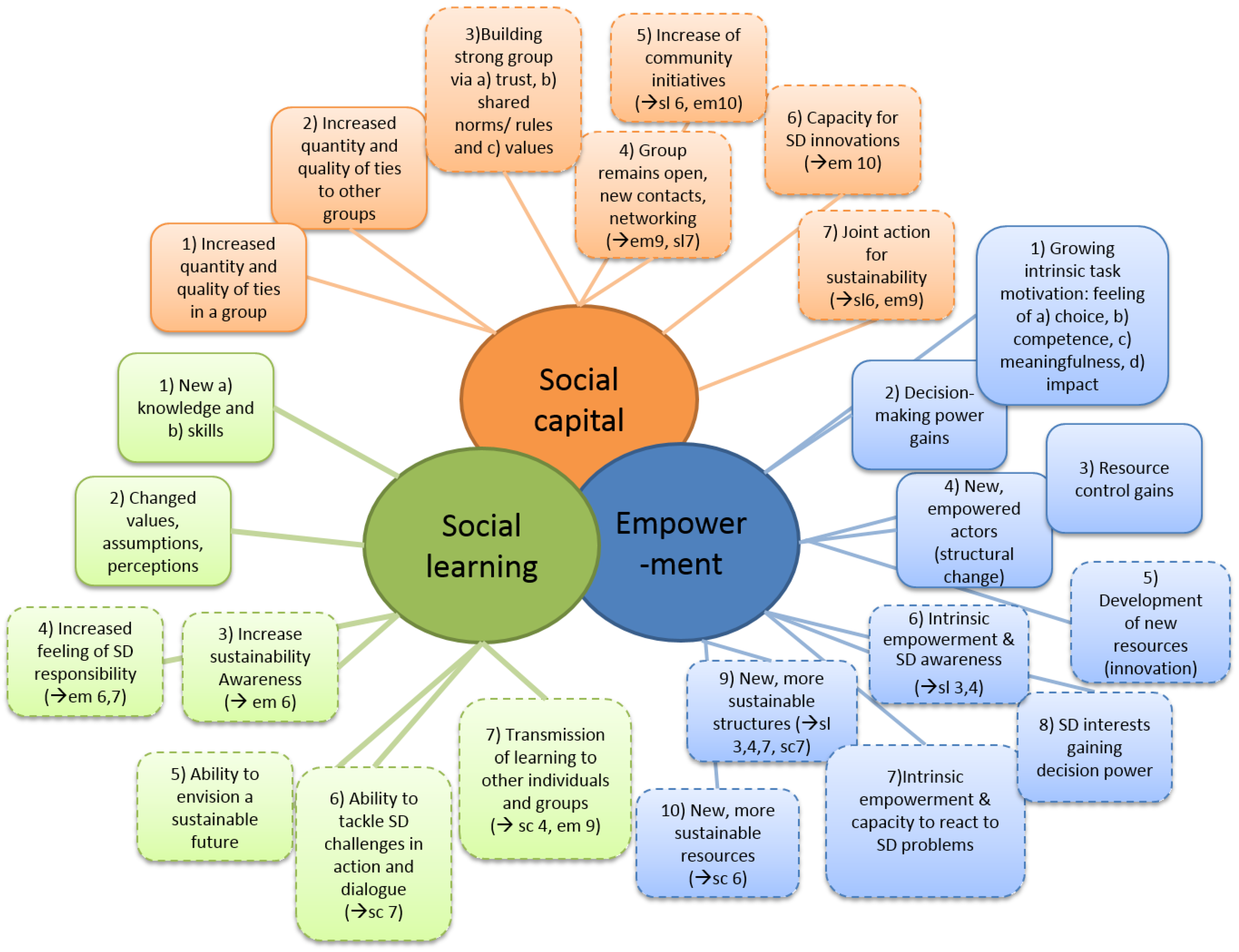

- The second category refers to enhanced capacity, which includes the acquisition of knowledge by individuals and collectives as well as of skills (know-how) for applying the new knowledge. Capacity is built through participatory research features, “as they organize and encourage information exchange, mutual, and joint learning” [45]. Rather than on ‘enhanced capacity’, transition management focuses on (social) learning and empowerment of participants in the transition arena setting [13,49].Transition management aims for “transformative change in societal systems through a process of searching, learning, and experimenting” [32] (p. 1006). Learning is considered as core to overcoming lock-in situations, allowing for innovations and systems change [29]. Loorbach highlights the value of learning-by-doing as a core process within transition management, allowing for an experimental and explorative attitude to social innovation and change [22,25]. Social learning, as a reflexive learning process that involves and goes beyond individual participants, is considered a precondition of change within the transition management literature. It is based on bringing together different actors’ perspectives and a variety of options in participatory settings. Joint learning of participants can contribute to the development of alternative and visionary solutions to complex challenges. This results in new types of discourse as well as changing perspectives [32].Besides social learning, the empowerment of civil society in locally addressing sustainability forms a second core effect of TM processes. As stated by Loorbach [13] (p. 284), “The ultimate goal of transition management should be to influence and empower civil society in such a way that people themselves shape sustainability in their own environments, and in doing so contribute to the desired transitions to sustainability”. This refers to the finding and realizing of (new) ways to solve social challenges in a local and sustainable way—and turn the visions of the future (sustainable) communities developed as part of the TM process into reality. Avelino highlights the empowerment of change agents and frontrunners in niches to challenge, transform or replace (unsustainable) regimes as a core strategy of transition management [49].

- (2b)

- The second category includes as well network effects. These refer to the creation or expansion of stakeholder networks and relationships (e.g., new contacts) as well as other qualities of human interrelations such as trust, identity, and accountability [45]. Via participation, transdisciplinary research does help to develop networks and structured interrelations. Similarly, transition management aims at the forming of new coalitions and networks [32] and more broadly new social relationships (such as new actors) to address societal challenges and contributing to sustainability transitions [48]. Transition management is centred around participatory spaces, e.g., transition arenas, which bring together a diversity of change agents or frontrunners for joint envisioning and collective action (e.g., [16]). The development of trust, shared goals and mutual expectations benefits the functioning of the transition arena process. The developed vision and respective images of change then need to be translated to wider networks, organizations and institutions [22]. Altogether, networks and relationships of trust and reciprocity are main determinants of social capital, whose increase is a third core societal effect of transition management processes—and an important precondition of collective action to address societal challenges [50].

2.2. Relating Social Learning, Empowerment and Social Capital to Sustainability

2.2.1. Social Learning

2.2.2. Empowerment

2.2.3. Social Capital

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Description

- (1)

- Environmental thinking (awareness of nature and natural resources),

- (2)

- Social thinking (consideration and acknowledgement of self and others),

- (3)

- Time horizon (short and long term) and

- (4)

- Interregional thinking (connection with other parts in the world, near and far).

3.2. Operationalization of Impacts, Data Collection and Interpretation

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Interplay of Societal Effects Contributing to Sustainability Transitions

5.2. Multi-Scalar Effects

5.3. Facilitating and Assessing Sustainability in Relation to Societal Effects

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Societal Effect | Aspects Composing the Societal Effect | Operationalisation of Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| Social Learning |

|

|

| Empowerment |

|

|

| Social Capital |

|

|

References

- United Nations Conference on Environment & Development. Agenda 21; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- WCED. Our Common Future: Report of the 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, P.J. Geology of mankind. Nature 2002, 415, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Part 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; de Haan, H. Transitions: Two steps from theory to policy. Futures 2009, 41, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, R.; Rotmans, J. Transition Governance towards a Bioeconomy: A Comparison of Finland and The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Complexity and transition management. J. Ind. Ecol. 2009, 13, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevyvere, H.; Nevens, F. Lost in Transition or Geared for the S-Curve? An Analysis of Flemish Transition Trajectories with a Focus on Energy Use and Buildings. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2415–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R.; Van Asselt, M. More evolution than revolution: Transition management in public policy. Foresight 2001, 3, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management. New Mode of Governance for Sustainable Development; International Books: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Becker, G.; Knieper, C.; Sendzimir, J. How Multilevel Societal Learning Processes Facilitate Transformative Change. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, C.; Wittmayer, J.; Henneman, P.; van Steenbergen, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Loorbach, D. Transition Management in the Urban Context: Guidance Manual; DRIFT, Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; 49p. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.; Van Steenbergen, F.; Quist, J.; Loorbach, D.; Hoogland, C. The Community Arena: A Co-Creation Tool for Sustainable Behaviour by Local Communities Methodological Guidelines; Deliverable 4.1; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T.R. Constructing sustainability science: Emerging perspectives and research trajectories. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Loorbach, D.; Meadowcroft, J. Governing societal transitions to sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.A. Transition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-Based Governance Framework. Gov. Int. J. Policy Adm. Inst. 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N. Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschmayer, F.; Bauler, T.; Schäpke, N. Towards a Governance of Sustainability Transitions: Giving Place to Individuals; UFZ Discussion Papers; Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research: Leipzig, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rauschmayer, F.; Bauler, T.; Schäpke, N. Towards a thick understanding of sustainability transitions—Linking transition management, capabilities and social practices. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 109, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Walker, G. CAUTION! Transitions ahead: Politics, practice, and sustainable transition management. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A. The politics of socio-ecological resilience and socio-technical transitions. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.; Avelino, F.; Giezen, M. Seeds of Change? Exploring (Dis-) Empowerment in Transition Management; DRIFT, Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bussels, M.; Happaerts, S.; Bruyninckx, H. Evaluating and Monitoring Lessons from a Field Scan; Policy Research Centre TRADO: Leuven, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, J.J.; Brown, R.R.; Farrelly, M.A. A design framework for creating social learning situations. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C.; Smits, R.; Woolthuis, R.K. Learning towards system innovation: Evaluating a systemic instrument. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, C.; Wittmayer, J. Transition Management in Five European cities—An Evaluation; DRIFT, Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R. Detour ahead: A response to Shove and Walker about the perilous road of transition management. Environ. Plan. A 2008, 40, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taanman, M.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Diepenmaat, H. Monitoring On-Going Vision Development in System Change Programmes. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2012, 12, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creten, T.; Happaerts, S.; Bachus, K. Evaluating Long-Term Transition Programs on a Short-Term Basis towards a Five-Step Transition Program Evaluation Tool; Policy Research Centre TRADO: Leuven, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nocera, S.; Cavallaro, F. Policy Effectiveness for containing CO2 Emissions in Transportation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 20, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogl, K.; Kvarda, E.; Nordbeck, R.; Pregernig, M. Environmental Governance: The Challenge of Legitimacy and Effectiveness; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mierlo, B.; Regeer, B.; van Amstel, M. Reflexive Monitoring in Action. A Guide for Monitoring System Innovation Projects; Communication and Innovation Studies, WUR: Wageningen, The Netherlands; Athena Institute, VU: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 3–104. [Google Scholar]

- Regeer, B.J.; Hoes, A.-C.; van Amstel-van Saane, M.; Caron-Flinterman, F.F.; Bunders, J.F.G. Six Guiding Principles for Evaluating Mode-2 Strategies for Sustainable Development. Am. J. Eval. 2009, 30, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Geels, F.W. Strategic niche management and sustainable innovation journeys: Theory, findings, research agenda, and policy. J. Tech. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2008, 20, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Raven, R. What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengers, F.; Wieczorek, A.; Raven, R.P.J.M. Experimenting for sustainability transitions: A systematic literature review. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regeer, B.J.; de Wildt-Liesveld, R.; van Mierlo, B.; Bunders, J.F.G. Exploring ways to reconcile accountability and learning in the evaluation of niche experiments. Evaluation 2016, 22, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, Arnim; Kay, Braden; Forrest, N. Worth the trouble?! An evaluative scheme for urban sustainability transition labs (USTL) and an application to the USTL in Phoenix, Arizona. In Urban Sustainability Transitions. Routledge Series on Sustainability Transitions; Frantzeskaki, N., Coenen, L., Broto, C., Loorbach, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, C.R.; Absenger-Helmli, I.; Schilling, T. The reality of transdisciplinarity: A framework-based self-reflection from science and practice leaders. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Talwar, S.; O’Shea, M.; Robinson, J. Toward a methodological scheme for capturing societal effects of participatory sustainability research. Res. Eval. 2014, 23, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.I.; Helgenberger, S.; Wiek, A.; Scholz, R.W. Measuring societal effects of transdisciplinary research projects: Design and application of an evaluation method. Eval. Program Plan. 2007, 30, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Wittmayer, J.; Loorbach, D. The role of partnerships in “realising” urban sustainability in Rotterdam’s City Ports Area, The Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N.; van Steenbergen, F.; Omann, I. Making sense of sustainability transitions locally: How action research contributes to addressing societal challenges. Crit. Policy Stud. 2014, 8, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F. Empowerment and the challenge of applying transition management to ongoing projects. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäpke, N.; Omann, I.; Mock, M.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Von Raggamby, A. Supporting sustainabiltiy transitions by enhancing the human dimension via empowerment, social learning and social capital. In Proceedings of the SCORAI Europe Workshop, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 7–8 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T.R.; Wiek, A.; Sarewitz, D.; Robinson, J.; Olsson, L.; Kriebel, D.; Loorbach, D. The future of sustainability science: A solutions-oriented research agenda. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Ness, B.; Schweizer-Ries, P.; Brand, F.S.; Farioli, F. From complex systems analysis to transformational change: A comparative appraisal of sustainability science projects. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.R.A.; Glass, J.; Laing, A. What is social learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, r1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, M.; Jeffrey, P. Time to Talk? How the Structure of Dialog Processes Shapes Stakeholder Learning in Participatory Water Resources Management. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; Kristjanson, P. A Catalyst toward Sustainability? Exploring Social Learning and Social Differentiation Approaches with the Agricultural Poor. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2685–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenhüner, B.; Rodela, R.; Ecker, F. Social learning research in ecological economics: A survey. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Kerkhof, M.; Wieczorek, A. Learning and stakeholder participation in transition processes towards sustainability: Methodological considerations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2005, 72, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodela, R. Social Learning and Natural Resource Management: The Emergence of Three Research Perspectives. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodela, R. The social learning discourse: Trends, themes and interdisciplinary influences in current research. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 25, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauppenlehner-Kloyber, E.; Penker, M. Between Participation and Collective Action—From Occasional Liaisons towards Long-Term Co-Management for Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, T.S.L. Learning to Manage Global Environmental Risks: A Comparative History of Social Responses to Climate Change, Ozone Depletion, and Acid Rain; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.A.E.J. Social Learning towards a Sustainable World: Principles, Perspectives, and Praxis; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, John; Loeber, A. Theories of learning. Agency, structure and change. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods; Fischer, F., Miller, G., Sidney, M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2006; pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organisational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. On Dialogue, Culture, and Organizational Learning. Reflections 1993, 4, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, W.N. Taking flight: Dialogue, collective thinking, and organizational learning. Organ. Dyn. 1993, 22, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, E.; Stagl, S. Public participation for sustainability and social learning: Concepts and lessons from three case studies in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabs, J.; Langen, N.; Maschkowski, G.; Schäpke, N. Understanding role models for change: A multilevel analysis of success factors of grassroots movements for sustainable consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 134A, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäpke, N.; Rauschmayer, F. Going beyond efficiency: Including altruistic motives in behavioral models for sustainability transitions to address sufficiency. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2014, 10, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Taanman, M.; Diepenmaat, H.; Cuppen, E. Reflection for targeted action. The use of transition monitoring in innovation programs. Presented at the Easy-eco Vienna Conference, Vienna, Austria, 11–14 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, T.; Kasser, T. Human Identity. A Missing Link in Environmental Campaining. Environment 2010, 52, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, T. Common Cause: The Case for Working with Our Cultural Values; WWF-UK: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, F. Power in Transition: Empowering Discourses on Sustainability Transitions. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241860638_Power_in_Transition_Empowering_Discourses_on_Sustainability_Transitions (accessed on 1 May 2017).

- Pick, Susan; Sirkin, J. Breaking the Poverty Cycle: The Human Basis for Sustainable Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo Lima Constantino, P.; Carlos, H.S.A.; Ramalho, E.E.; Rostant, L.; Marinelli, C.E.; Teles, D.; Fonseca-Junior, S.F.; Fernandes, R.B.; Valsecchi, J. Empowering Local People through Community-based Resource Monitoring: A Comparison of Brazil and Namibia. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Chomba, S.W.; Nathan, I.; Minang, P.A.; Sinclair, F. Illusions of empowerment? Questioning policy and practice of community forestry in Kenya. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.D.G.; Dougill, A.J.; Mabee, W.E.; Reed, M.; McAlpine, P. Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayoux, L. Tackling the Down Side: Social Capital, Women’s Empowerment and Micro-Finance in Cameroon. Dev. Chang. 2001, 32, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Mehta, J.N.; Ebbin, S.A.; Lichtenfeld, L.L. Community Natural Resource Management: Promise, Rhetoric, and Reality. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2000, 13, 705–715. [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcroft, J. What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.W.; Velthouse, B.A. Cognitive Elements of Empowerment: An “Interpretive” Model of Intrinsic Task Motivation. Acad. Manag. 1990, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar]

- Boje, D.M.; Rosile, G.A. Where’s the Power in Empowerment? Answers from Follett and Clegg. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2001, 37, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, W.A. Re-thinking empowerment. Organ. Dyn. 2000, 29, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Bosch, S.; Rotmans, J. Deepening, Broadening and Scaling Up; DRIFT, Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- German Advisory Council on Global Change. A Social Contract for Sustainability; WBGU: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kristof, K. Models of change. Einführung und Verbreitung Sozialer Innovationen und Gesellschaftlicher Veränderungen in Transdisziplinärer Perspektive; vdf Hochschulverlag: Zürich, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, C.; Banjade, M.R. Social capital, conflict, and adaptive collaborative governance: Exploring the dialectic. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico García-Amado, L.; Ruiz Pérez, M.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; Dahringer, G.; Reyes, F.; Barrasa, S. Building ties: Social capital network analysis of a forest community in a biosphere reserve in Chiapas, Mexico. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. Capitals and Capabilities: A Framework for Analyzing Peasant Viability, Rural Livelihoods and Poverty. World Dev. 1999, 27, 2021–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T. The meaning of social capital and its link to collective action. In Handbook of Social Capital: The Troika of Sociology, Political Science and Economics; Svendsen, G.T., Svendsen, G.L., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mansuri, G. Community-Based and -Driven Development: A Critical Review. World Bank Res. Obs. 2004, 19, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, S.; Buchecker, M. Does Participatory Planning Foster the Transformation Toward More Adaptive Social-Ecological Systems? Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Ward, H. Migration, Social Capital and the Environment. World Dev. 2001, 29, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Smith, D. Social Capital in Biodiversity Conservation and Management. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S. Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Gehmacher, E.; Kroismayr, S.; Neumüller, J.; Schuster, M. Sozialkapital: Neue Zugänge zu Gesellschaftlichen Kräften; Mandelbaum Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Uphoff, N. Understanding social capital: Learning from the analysis and experience of participation. In Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective; Dasgupta, P., Serageldin, I., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 79, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defi ning Urban Social Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballet, J.; Sirven, N.; Requiers-Desjardins, M. Social Capital and Natural Resource Management: A Critical Perspective. J. Environ. Dev. 2007, 16, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss, J. Depoliticizing Development: The World Bank and Social Capital; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Omann, Ines; Grünberger, S. Quality of life and sustainability. Links between sustainable behaviour, social capital and well-being. In Proceedings of the 9th Biennial Conference of the European Society for Ecological Economics (ESEE): Advancing Sustainability in a Time of Crisis, Istanbul, Turkey, 14–17 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill, M. Strengthening the “social”in sustainable development: Developing a conceptual framework for social sustainability in a rapid urban growth region in Australia. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ročak, M.; Hospers, G.-J.; Reverda, N. Searching for Social Sustainability: The Case of the Shrinking City of Heerlen, The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T. The disappearing sustainability triangle: Community level considerations. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppen, E.; Pesch, U.; Remmerswaal, S.; Taanman, M. Normative diversity, conflict and transition: Shale gas in The Netherlands. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bosch, S.; Rotmans, J. Deepening, Broadening and Scaling up: A Framework for Steering Transition Experiments. Available online: https://repub.eur.nl/pub/15812/ (accessed on 1 May 2017).

- Wittmayer, J.; Mock, M.; van Steenbergen, F.; Baasch, S.; Omann, I.; Schäpke, N. Taking Stock—Three Years of Addressing Societal Challenges on Community Level through Action Research; Pilot specific synthesis report; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.; van Steenbergen, F.; Bohunovsky, L.; Baasch, S.; Quist, J.; Loorbach, D.; Hoogland, C. Pilot Projects Getting Started Year 1 Status Report; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.; van Steenbergen, F.; Bohunovsky, L.; Baasch, S.; Quist, J.; Loorbach, D.; Hoogland, C. Pilot Projects on a Roll—Year 2 pilot Specific Reports; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.; Schäpke, N.; Feiner, G.; Piotrowski, R.; Van Steenbergen, F.; Baasch, S. Action Research for Sustainability Reflections on Transition Management in Practice; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.; van Steenbergen, F.; Baasch, S.; Feiner, G.; Mock, M.; Omann, I. Pilot Projects Rounding up Year 3 Pilot-Specific Report; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M. Shifting Power Relations in Sustainability Transitions: A Multi-actor Perspective. Submitt. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2015, 7200, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, P.G.; Reason, P. Initiating action research Challenges and paradoxes of opening communicative space. Action Res. 2015, 7, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, D.; Shani, A.B. Roles, politics, and ethics in action research design. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2005, 18, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Impact | Description (Subject and Object of Impact) | Potential Contributions to Sustainability (Result of Impact) | Adverse Effects (Critique) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social learning | Social learning comprises processes of individual and collective experimentation, reflection and innovation [22,32], which lead to lasting changes in the interpretive frames (such as belief systems, cognitive frameworks, etc.) guiding the actions of a person [63]. In detail, it can include:

|

| A focus on consensus building, shared goals and trust/respect to foster social learning may limit the space for radical change (towards sustainability) [108] |

| Empowerment | Empowerment refers to:

|

| Empowerment paradox: the attempt to empower somebody establishes a dependency relationship and therefore may ultimately be disempowering [49] |

| Social capital | Social capital structurally refers to relationships between individuals, groups and networks [87,96]. Two dimensions can be distinguished [97]:

|

| Strong increase of social capital within a group may create exclusion tendencies towards “outsiders” [101], hamper innovation [102] and obscure power relationships [91,103]. |

| No | Aspects | Finkenstein | Carnisse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | New skills | Several survey R discovered new competencies: speaking one’s own mind in public, better communication, creativity, organisation, leadership, an increase in self-reflexivity and the feeling of responsibility as well as the ability to work in a team and the understanding for political work—R made similar observations. | Diverse new skills reported: speaking one’s own mind in public, sharing knowledge and perspectives, put things in a broader perspective, R made similar observations. Additionally observed skills: working respectfully together, chairing group session, reporting outcomes. |

| 1b | New knowledge | P reported some surprises, insight that individual worries (but also ideas) are shared by others; a general increase in knowledge. Ps learned about the idea of transitions, sustainability transitions, participatory methods and issues related to different areas such as mobility, energy, local economic affairs; knowledge repercussions in outputs generated. | P reported more knowledge and awareness on what was happening around them, the neighbourhood and its dynamics and the history of Carnisse. Legal, financial and institutional know-how related to a community centre was gained. R observed participants getting acquainted with new perspectives. |

| 2 | Changed values, assumptions and perceptions | P reported increased trust, more openness, fewer prejudices, positive attitudes to change and more long-term thinking, personal growth and a higher motivation to engage. No particular observations. | P reported awareness that they can make a difference; arena re-affirmed their current perspectives and values; vision gave them nice ordering of their assumptions and perspectives on change. R observed P starting to feel that change is necessary and possible, a continuous process that comes from within. |

| 3 | Increased sustainability awareness | P stated sustainability is a very important issue. Working groups explicitly or implicitly deal with sustainability; experiments address sustainability challenges; the vision includes sustainability goals. | All P found a clear connection between sustainability and the vision; interpretations of sustainability differed, but the common denominator was a focus on the long term. Sustainability was multi-interpretable, no consensus on priorities was reached, the vision created awareness of the interconnectedness of different scales. |

| 4 | Increased feeling of responsibility for sustainability | P partially feel responsible; in general increased feeling of responsibility of own actions. Working on a common vision including sustainability increased sustainability awareness; the vision attributes responsibility to the current generation. It was agreed upon by all participants. | P reported tackling neighbourhood problems (not specific sustainability problems), felt responsible for participating in the arena and lamented the absence of institutional actors from the arena process and the outsourcing of responsibility. N/A |

| 5 | Ability to envision a (sustainable) future | N/A. A joint vision was developed, agreed upon by all, to include sustainability. Radical change was constantly promoted by single participants only; participants reacted rather annoyed, and the arena stuck to envisioning soft changes. | All P found a clear connection between sustainability and the vision; interpretations of sustainability differed, but the common denominator was a focus on the long term. Some reported the vision was too utopian, while others stated that it wasn’t radical enough. A joint vision was developed, with input from group discussions and 1-on-1 interviews. It includes ecological and mostly social aspects of sustainability. Vision was agreed upon in the arena; however, most participants did not own the vision. |

| 6 | Tackling sustainability in actions & dialog | P stated that the project would be beneficial for future generations and other regions and would benefit sustainability in Finkenstein. Eight working groups, several actions and events in many parts relating to sustainability were developed. Nine out of 15 participants stated that the project implements measures that are future-oriented and benefit other parts of the world. A “climate energy model-region” was applied for and got accepted. Working groups are related to sustainability. An institutional structure for further implementation of the vision has been built, establishing a local steering committee. (→sc aspect 7). | For most P neighbourhood development (so not SD) was a collaborative effort par excellence and working collaboratively was the guiding principle of the vision. Sustainability was operationalized in relation to social challenges. Collaborative actions were initiated in the experiments. Directly: No explicit joint action for sustainability was mentioned; the community centre reopening was a reaction to local, social problems. Indirectly: three newly arena-initiated experiments related to social aspects of sustainability. (→sc aspect 7) |

| 7 | Transmission of (sustainability) learning | P stated that they have frequently talked with other citizens about the project, and met with some interest and some scepticism. Results presented to the transition team (local politicians) as well as to the interested public. Following the arena process, a successful application was launched to become a “climate-energy–model-region”, building on insights from the arena process and supported by local officials. (→sc aspect 4). | Vision was being distributed during a network event. P talked to other residents about ‘Bloeiend Carnisse’, the development vision for Carnisse. People who were not engaged in the process were mainly sceptical; although they liked the vision, but considered it too abstract. Similar observations, plus the vision was presented in the media. General focus on internal group process. The experiment of reopening a community centre under self-maintenance attracted the interest of officials of the Rotterdam municipality and was interpreted as a potential model for mitigating the crisis of the welfare state within the city. (→sc aspect 4) |

| No | Aspects | Finkenstein | Carnisse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Growing intrinsic task motivation via A) choice, B) competence, C) meaningfulness and D) impact. | (A) P reported they were able to choose the agenda. Vision written by researchers but developed and agreed upon by the community arena, with working groups and actions led by P. (B) Cf. social learning/new skills; P took roles depending on competences they became aware of during the arena, and new skills got developed. (C) Good scores for bringing in their own input and topics, open agenda, majority of P had the feeling of doing something meaningful; R made similar observations. (D) P believe they have an impact on the local environment; the steps taken were quite small; some changes were based on assumptions about their own ability to impact development; 50% of P reported increase in possibilities to shape Finkenstein; attitudes towards the future changed in a positive way; experiments impacted upon local developments in the form of raising attention, attracting additional participants and finally the validation of the climate energy model region in Finkenstein. | (A) All P reported being able to choose the agenda. The arena process helped to voice perspectives on the state of Carnisse. (B) P reported gains in confidence to speak in public (see ‘skills’ in social learning table); P took different roles, could employ their competences in the arena when necessary. (C) Scores P gave for being able to bring in their own input and topics were good; P felt vision was a great result, appreciated the exchange of perspectives. Motivation in group was very apparent during the whole process, a symptom of a meaningful process. (D) Scores P gave to level of impact they are having were good. P stated they were able to make a difference. Some had this feeling prior to the arena. Others stated the arena-process did not develop sufficient tangible actions for people to make an impact. P, in re-opening of the community centre, stated they can make a direct impact in the here and now. Re-opening the community centre made a direct impact; presentation of vision to broader audience had impact. |

| 2 | Gains in decision-making power with regard to local developments | Change in perception of local politics: realizing own ability to shape local politics, taking responsibility for local developments, recognition of the value of local politics. The majority of P agreed that they can bring their own requests/ideas to the municipality. No formalized decision-making power granted by local politics, but increased influence on local development; working groups started activities, organized courses and events, brought new ideas to the community council. | Most P reported being decision-makers with power, but also reported that the most important decision-makers were not present in the arena process and that they needed to be involved. Arena had strong emphasis on ‘power to the people’, managed to influence a large-scale networking event and to put its transition agenda on the table. (See also aspect 1/impact above) |

| 3 | Gains of control over resources by arena participants | Nothing to report. Very few concrete resources granted; intangible resources difficult to observe. Actions by arena P frequently undertaken without waiting for permission or resources from the community council. | Direct effect was generated by taking control over the closed community centre, participants stated actors who control resources should step up. Resource of symbolic legitimization, financial and physical capital to re-open and manage the community centre. New social capital (ties and networks of engaged residents and volunteers) and symbolic capital (the group became a powerful actor in the institutional network of Carnisse). |

| 4 | Changes in local structures (e.g., new actors) | Nothing to report: Arena established itself as a new, but temporal actor in the local system. It gained more and more publicity; supporting group of local officials (the transition team); a local steering committee was elected | Nothing to report. Community arena did not appear as a new actor much, because it was kept in the shadows/margins. But group action- around the community centre gained considerable influence (because of their central position in the neighbourhood and influential networks). |

| 5 | Development of new resources (innovation) | Nothing to report. Nothing to report. | Nothing to report. Symbolic capital: vision and the arena became a symbol to relate to. See aspect 3/resource gains on new social capital and symbolic capital strengthening the new actor. |

| 6 | Empowerment contributes to sustainability if increasing meaningfulness (aspect 1) relates to sustainability | R stated sustainability is a very important issue. Working groups explicitly or implicitly deal with sustainability; experiments o address sustainability challenges; the vision includes sustainability goals. P partially feel responsible; in general they have an increased feeling of responsibility for their own actions. Working on a common vision including sustainability increased sustainability awareness; the vision attributes responsibility to the current generation. It was agreed upon by all participants. (→sl aspect 3, 4) | All respondents found a clear connection between sustainability and the vision, but the interpretation of sustainability differed. Focus on the long term and local problems such as social challenges. Some participants reported that they were engaged because they felt responsible for solving these challenges. Long-term thinking and awareness of the interlinkages between different scale levels were strengthened. Sustainability was interpreted in different ways by the different participants, but the vision created awareness on the interconnectedness of different scales. Vision shows sustainability in social, ecological and economical dimensions. This potentially was influenced by the writing by the researchers. →social learning 3 P reported on tackling neighbourhood problems (not specific sustainability problems), felt responsible for participating in the arena and lamented the absence of institutional actors from the arena process and the outsourcing of responsibility. N/a →social learning 4 |

| 7 | Feeling of (increased) capacity to react to sus. problems | The vision exerted pull and encouraged participants to build pathways for reaching the vision; attempts to directly influence the decisions of the community council were only partially successful. Rs made similar observations. | P reported community centre reopening as a reaction to local, social problems. Vision of arena and arena process focussed on “power to the people”, independence from local institutional structures, embeddedness of new actions in the local communities. |

| 8 | New sustainability-related decision-making capacities | Nothing to report; working groups influenced local developments with their actions, including sustainability-related experiments. | Nothing to report. Only with regard to social aspects of sustainability as part of the re-opened community centre. |

| 9 | A sustainability orientation of new actors and changing of local structures | P stated sustainability is a very important issue and they partially feel responsible for it; in general they have an increased feeling of responsibility for their own actions. Indirectly: The arena group and related working groups established themselves as new local actors. The developed vision shows the high value of sustainability; Some working groups and activities highlighted the value of sustainability (→sl aspect 3, 4) P stated that they have frequently talked with other citizens about the project, and were met with some interest but also some scepticism. Results presented to the transition team (local politicians) as well as to the interested public. Following the arena process, a successful application was launched to become a climate energy model region, building on insights from the arena process and supported by local officials. (→sl aspect 7) P stated that the project was beneficial for future generations and other regions and could benefit sustainability in Finkenstein. Eight working groups; several actions and events in many parts relating to sustainability were developed. Nine out of 15 participants stated that the project implements measures that are future-oriented and benefit other parts of the world. A “climate-energy-model-region” was applied for and got accepted. Working groups are related to sustainability. An institutional structure for further implementation of the vision has been built, establishing a local steering committee. →social capital 6 | Nothing to report. The foundation board, as a new local actor, had a certain (implicit) sustainability orientation. The experiment run by the foundation board of reopening a community centre under self-maintenance attracted the interest of officials of the Rotterdam municipality and was interpreted as a potential model for mitigating the crisis of the welfare state within the city. All P found a clear connection between sustainability and the vision; the interpretation of sustainability differed, but the common denominator was a focus on the long term. Sustainability was interpreted in different ways; no consensus on priorities was reached, but the vision created awareness of the interconnectedness of different scales. →social learning 3 P reported on tackling neighbourhood problems (not specific sustainability problems), felt responsible for participating in the arena and lamented the absence of institutional actors from the arena process and the outsourcing of responsibility. N/a→social learning 4 Vision was being distributed during a network event. P talked to other residents about ‘Bloeiend Carnisse’, the development vision for Carnisse. People who were not engaged in the process were mainly sceptical; although they liked the vision, it was considered too abstract. Similar observations, plus the vision was presented in the media. General focus on internal group process. The experiment of reopening a community centre under self-maintenance attracted the interest of officials of the Rotterdam municipality and was interpreted as a potential model for mitigating the crisis of the welfare state within the city.→social learning 7 Directly: No explicit joint action for sustainability was mentioned; the community centre reopening was a reaction to local, social problems. Indirectly: three newly arena initiated experiments, related to social aspects of sustainability.→social capital 7 |

| 10 | Developed resources to contribute to sustainability | Nothing to report | Nothing to report. Vision as a symbol including sustainability aspects may implicitly promote sustainability in neighbourhood development. (→sc aspect 6) |

| No | Aspects | Finkenstein | Carnisse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quantity and quality of ties within a group, i.e., the community arena | Approximately 60 P meet regularly; many of them did not know each other before.

Collaboration with like-minded people was appreciated. P perceived themselves as “one group”; development of very good relationships, more trustful relationships and connection to new milieus. The group was quite diverse; participants did not know each other; trustful atmosphere; group feeling. | 67 P in total made contact with each other. Participants did not know each other beforehand and were quite diverse. They did not see the arena as a stable group with a lot of cohesion and interactions were very informal, loose and short-term. A shared feeling of responsibility for Carnisse was expressed. The arena group was exclusive in participation. Ties within the arena group were rather distant. Different phases can be observed: from open and flexible to a closed core group that was opening up again. |

| 2 | Quantity and quality of ties with other groups, i.e., other groups within or beyond the community | Quantity not concretely assessed. P frequently talked with other citizens about the project and met with some interest and some scepticism. Criticism of P regarding lack of public interest. Arena connected to public in three broadening events; connected with policy makers in three meetings. Ties to Slovenian minority in Finkenstein could not be established. | Quantity not concretely assessed. Outside contact on the topic of the arena did not really take place. In regard to the experiment, there was a lot of exchange. One public broadening event with 100+ participants, contact established with local municipality and government. Work on the opening of the community centre established further contact with the Rotterdam municipality, housing cooperations, local schools, etc. Ties to inhabitants with immigrant backgrounds were difficult to establish and maintain in deliberative processes, but for visitors of the community centre and participants in workshops and activities new ties were established |

| 3a | Building strong group via a) development of trust within the group | Growing trust was reported, as well as working together in a respectful and constructive way. Trust could be observed. | Group feeling was not really created. Not observed. |

| 3b | Building strong group via b) development of shared rules and norms within group | Similar concerns among the participants; communication became more appreciative. The steering committee was elected by a mutually agreed voting procedure; communication guidelines were developed. | Not assessed. The common denominator of the group was a shared connection and responsibility to the neighbourhood. |

| 3c | Building strong group via c) development of shared values within the group | Initially divagating interests and aims were transferred into a shared vision and actions benefitting the common good. Some activities show shared values (mostly social); the vision includes a number of value statements and was endorsed by the whole arena group. | Not assessed. Shared values of group centred around social morals for community; also apparent in the vision. |

| 4 | Group shows openness towards new contacts, networking | Process sparked interest in and respect for other persons, increased self-reflexivity and led to fewer prejudices. Working groups focussed on establishing exchange. P stated that they have frequently talked with other citizens about the project, meeting with some interest and some scepticism. Results presented to the transition team (local politicians) as well as to the interested public. Following the arena process, a successful application was launched to become a “climate-energy-model–region”, building on insights from the arena process and supported by local officials. (→sl aspect 7, em 9) | Some participants reported that they had sparked interest in other participants. Efforts were made by the arena group to invite new contacts to each meeting, but these were not very effective. The experiment run by the foundation board of reopening a community centre under self-maintenance attracted the interest of officials of the Rotterdam municipality and was interpreted as a potential model for mitigating the crisis of the welfare state within the city (→sl aspect 7, em 9) |

| 5 | Quantity and quality of sustained or new community initiatives | Quantity: 60 participants in eight working groups meet regularly; eight arena workshops with 10–30 participants each took place; Quality: new ways of working together. Quantity: eight collective actions were started. Quality—nothing to report. (→sl aspect 6) | N/A Three types of innovative practices: newly arena initiated experiments; participants engaged in own (innovative) activities; innovative ideas communicated through the vision and a networking event. (→sl aspect 6) |

| 6 | Capacity for sustainability-related innovations | Nothing to report. Nothing to report. | Nothing to report. Vision as a symbol including sustainability aspects may implicitly promote sustainability in neighbourhood development. (→em aspect 10) |

| 7 | Joint action for sustainability | Nine out of 15 participants state that the project implements measures that are future-oriented and benefit other parts of the world. A “climate-energy-model region” was applied for and got accepted. Working groups are related to sustainability. An institutional structure for further implementation of the vision has been built, establishing a local steering committee. (→em aspect 9) P stated project was beneficial for future generations and other regions and would benefit sustainability in Finkenstein. Eight working groups, several actions and events in many parts relating to sustainability were developed. (→sl aspect 6) | Directly: No explicit joint action for sustainability was mentioned; community centre reopening was a reaction to local, social problems. Indirectly: three newly arena initiated experiments, related to social aspects of sustainability. (→em aspect 9) For most P, neighbourhood development (so not SD) was a collaborative effort par excellence and working collaboratively was the guiding principle for the vision. Thereby, sustainability was operationalized in relation to social challenges. Collaborative actions were initiated in experiments. (→sl aspect 6) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schäpke, N.; Omann, I.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Van Steenbergen, F.; Mock, M. Linking Transitions to Sustainability: A Study of the Societal Effects of Transition Management. Sustainability 2017, 9, 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050737

Schäpke N, Omann I, Wittmayer JM, Van Steenbergen F, Mock M. Linking Transitions to Sustainability: A Study of the Societal Effects of Transition Management. Sustainability. 2017; 9(5):737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050737

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchäpke, Niko, Ines Omann, Julia M. Wittmayer, Frank Van Steenbergen, and Mirijam Mock. 2017. "Linking Transitions to Sustainability: A Study of the Societal Effects of Transition Management" Sustainability 9, no. 5: 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050737

APA StyleSchäpke, N., Omann, I., Wittmayer, J. M., Van Steenbergen, F., & Mock, M. (2017). Linking Transitions to Sustainability: A Study of the Societal Effects of Transition Management. Sustainability, 9(5), 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050737