Abstract

Historic city centres of European cities are one of the most important elements of the European cultural heritage. They are places that attract many visitors due to their relevance in terms of heritage, but the recent growth of tourist flows constitutes a threat to the conservation of their values. In some European cities, such as Venice or Barcelona, the debate has taken to the streets, and there is significant social mobilization taking place, with very belligerent positions against tourism (anti-tourism, tourismphobia). The mass media also generates discourse on the topic and places the debate on urban tourism sustainability at the forefront of the public debate. In this context, this article reviews the state of the art on tourism impact and identifies, describes and evaluates the different dimensions of tourist pressure based on a case study: the historic centre of the city of Donostia-San Sebastián (Basque Country, Spain). The main goal of the research is to help determine how tourist pressure affects the safeguarding of “historic urban landscapes” and the desirable or desired models of city and tourist destination.

1. Introduction

Historic city centres are a core part of European cultural heritage. The majority of these centres are protected under each country’s legislation. In addition to this, many of them have been included in the UNESCO List of World Heritage Sites. In these cases, the discussion uses the definition of “Groups of Buildings” as defined in the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972) and, specifically, urban buildings corresponding to “historic cities” (1987 Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention). The expression “historic urban landscape” was coined recently, a term that has become enshrined in institutional doctrine on heritage based on the Vienna Memorandum (2005) and the object of a specific UNESCO Recommendation (2011). According to this doctrine, the historic urban landscape incorporates not only material and immaterial components, but also the natural substratum moulded by each generation of settlers and even changing perceptions of this landscape. It involves taking a holistic approach based on the integration of morphological, socioeconomic and cultural factors.

Cities are the most important component of cultural tourism in Europe. Visitor influx tends to be concentrated in urban centres, which overlap unevenly with historic centres. There is a substantial flow of tourists and day trippers inspired or motivated by cultural factors and interested in historic heritage and/or contemporary culture. This flow coexists with visitors with broader and more heterogeneous intentions. Whatever the purpose of their journey may be, tourists and day trippers make intensive use of historic centres, engaging in a series of cultural activities during their visits that overlap with the occupations of both local residents and residents from the rest of the urban sprawl.

Tourism produces an impact on the city, especially in historic centres. This topic has formed the basis of a well-established line of research with important contributions being made since the 1980s. It also appears repeatedly in the work of major institutions contributing to learning in matters of heritage and urban development. Recently, the debate on this kind of impact has moved beyond the boundaries of academia and tourism stakeholders. In many European cities, a very negative view of the local effects of tourism has started to surface. Various social collectives have been marching against the different forms of city tourism, with issues ranging from the increase in tourist rental properties to cruise ships. Although these demonstrations do not usually attract large numbers of protesters, they are quite visible in the media. Local governments have added the negative effects of tourism to their agendas, and are starting to develop mitigation plans and programmes. Tourism is even starting to be seen as a problem for a large part of the local community in the most popular urban destinations. Two processes have favoured the appearance of this kind of opinion. Firstly, the rapid and spectacular growth in visitor numbers to leading European urban tourism destinations [1]. Secondly, the boom in tourist rental accommodation, favoured by P2P platforms like Airbnb [2]. Although the effects of this expansion are still difficult to determine, it is raising all sorts of new issues that need to be addressed by urban tourism management.

This study sets out to establish how certain tourism related processes affect how historic urban landscapes are safeguarded. In these spaces, tourist activity will be sustainable if it does not involve a deterioration in the set of physical, socioeconomic and symbolic characteristics as a whole. The study is based on and makes reference to the Parte Vieja (Old Quarter) of Donostia-San Sebastián, a historic neighbourhood in one of Spain’s traditionally most popular cities for tourism. Like many other places, the Parte Vieja is seeing rising levels of tourist pressure accompanied by a certain social resistance and the need to add the issue to the local political agenda. In addition to the introduction, this paper is divided into four sections. The first addresses the state of the art on the impact of tourism on cities. This is followed by the research methodology and the case study. The next section analyses the main factors of tourism pressure (results and discussion). The final section deals with the conclusions.

2. The Impact of Tourism on the City: State of the Art

Although some cities have been receiving visitors for a long time, urban tourism really started to emerge in the 1990s. During these years, tourism flows increased, tourism took on a high-profile role on the urban agenda and tourism research rediscovered the city. This was a period of major studies on urban tourism, which usually included specific chapters on the impact of tourism on the city [3,4,5,6]. Generally speaking, the classic studies on tourism impact have been used as a reference [7]. Among other issues, it was accepted that the sense and intensity of the impact depends on both visitor numbers and the characteristics of the destination. The impact may be physical, economic or social and it may be felt in a positive or negative sense. Sustainable planning in the destination involves maximising the positive effects of tourism and minimising the negative effects. This set of hypotheses was then applied to the study of the effects of tourism on the city. There was a prevailingly optimistic view, which emphasised the contribution of leisure and tourism to urban development [8], often as part of major renovation operations. Pearce [9] incorporated the scale aspect into the study of urban tourism, a factor that should be considered when assessing impact.

In Europe, most of the urban tourism flow was concentrated in cities and historic centres. Over the years, this gave rise to a more specific line of research focusing on these spaces. In addition to general discussions [10,11,12,13], more concrete issues relating to the impact of tourism were tackled. The term touristification was used to explain the process of change in urban forms and functions derived from the implementation and growth of tourism activity [14]. This process had a particular effect on the “tourist-historic city” [15], the part of the historic city that visitors actually use. The existence of cities under pressure was highlighted [16], and the relations between tourism impact, carrying capacity and visitor management were analysed [17,18]. Based on the destination life cycle theory, Russo [19] puts forward the existence of a vicious circle of tourism development in large heritage cities, with reference to the case of Venice.

The growth of research into urban tourism led to a proliferation of study topics [20]. In terms of tourism impact, these included holistic approaches focused on destination sites through to much more specific studies on one or two aspects of the impact. Estimates were produced on the effects of tourism on the urban economy based on the input-output model [21]. Similar studies have been produced to assess the economic impact of major cultural tourism attractions [22] and events such as European Capital of Culture [23]. Studies on social impact include work on the way local communities perceive this kind of impact, and their attitudes to tourism development [24,25]. Surveys of the resident population are used to probe the connection between these factors and variables such as personal and collective economic dependence on the tourism activity, the proximity of the home address to the places with high visitor numbers and various socio-economic factors. The sustainability of the destination also implies obtaining a satisfactory tourist experience, so the effects of high visitor numbers on that experience is also analysed [26,27]. High visitor numbers may also lead to a perception of overcrowding, but visitors may also see this as being a typical feature of tourism sites [28]. Generally speaking, there is a predominance of quantitative studies. However, these contain interesting discussions arising from analysis of the discourse of different stakeholders [29,30,31,32], which enables alliances, conflicts and contradictions to be identified according to areas of interest and reference scales. This entire set of themed discussions is being enriched with the results extracted from studies undertaken in emerging countries with fledgling tourism industries. Among other issues, work is being done on the attitudes of residents to tourism development [33,34], factors that influence the perception of overcrowding and its impact on the tourist experience [35], and changes in the commercial landscape derived from the growth in tourism [36].

To a great extent, this scientific research has fed into approaches to the impact on tourism of major institutions contributing to doctrine on the subject of urban heritage, namely the World Heritage Centre [37], ICOMOS [38], OWHC and others. It is even a topic of discussion at the World Tourism Organisation [39,40,41], UN-Habitat [42] and the European Commission [43]. Compared to sector approaches, the focus is more holistic, centred on the logic of the particular site in question. The historic city is discussed on the basis of the historic urban landscape approach [44], paying particular attention to World Heritage Sites, where tourism is a recurring theme [45]. The negative effects on the conservation of cities and historic centres is worrying, but the positive impact of tourism as a factor in urban regeneration is also accepted, in both physical and socio-economic terms. This explains the emphasis on sustainable site planning and management [46], incorporating the local community as a producing agent of both the space and its heritage value and, at the same time, as the main receiver of the impact of tourism.

Together with tourism studies and doctrinal discussions on urban heritage, the last fifteen years have seen the emergence of a strong line of work on tourism gentrification [47,48]. Although there are some previous studies that explore the relationships between gentrification and tourism [49], the first major reference to tourism gentrification can be found in Gotham’s article [50] on the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) in New Orleans. Subsequent discussions have delved into aspects like the dynamics of the property market associated with the growth in urban tourism; the role of local authorities, public urban regeneration initiatives and their connection with property promotion; residential displacement, which involves both emptying an area and replacing one kind of settler for another with more spending power; commercial gentrification, with the appearance of a new globally oriented commercial landscape; plus discourses on the “right to the city”. These processes are all suitable for analysis over very long periods of time [51], highlighting similarities and differences between successive phases. Investigative work is also being done on the effects of the recent expansion of the tourism footprint in spaces that up to now had not seen visitors. These spaces may be local neighbourhoods in large tourist metropolises like Berlin [52]; historic quarters in cities that are part of leading sun and sand destinations, like Palma de Mallorca [53]; or historic centres in emerging regions like Latin America [54,55] and China [56]. In more recent studies, a frequent theme is the spread of tourism rental accommodation in urban centres. This surge, linked to the activities of P2P platforms, is the direct cause of residential displacement [57]. At the same time, this displacement reinforces commercial gentrification and puts the functioning of urban amenities intended for the local population at risk [58].

From our perspective, the biggest contribution of tourism gentrification studies lies in the emphasis placed on identifying impacts in the place itself, an approach that ties in fully with urban studies tradition. Touristification is a phenomenon that has been known about for some time, but more emphasis is now being placed on its effects and readings from the point of view of the communities affected, including price rises, residential displacement due to the impossibility of exercising the right to housing, loss of local traders, etc. This accounts for the importance being given to recording resistance movements [59], which vary from positions that merely question the current tourism model through to complete and frankly anti-tourism options.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study

Donostia-San Sebastián is a city with 186,062 inhabitants in the Basque Country (Spain). It has a long history of tourism stretching back to the 19th century as a spa city where members of the aristocracy came to spend their summers. In the Spanish context, it is a paradigm of bourgeois city planning [60] and its urban landscape is second to none, largely due to its privileged location facing the Cantabrian Sea and the development of local urban planning. The historic centre is known as Parte Vieja. It lies beneath Monte Urgull, a headland that separates the two main beaches of Zurriola and La Concha (see Figure 1). Its current layout is the result of reconstruction work carried out in the 19th century, after the destruction suffered by the city in the War against Napoleon. This means its streets follow a compact grid pattern, unlike the majority of European historic cities. The space is a unique example of urban planning and is home to some of the city’s main monuments as well as important expressions of intangible heritage (such as the Tamborrada).

Figure 1.

Parte Vieja (left-right: aerian view; Basílica de Santa María del Coro—18th century, Parte Vieja’s Port). Source: Turismo San Sebastian www.sansebastianturismo.com/es/.

Nowadays, Donostia-San Sebastián continues to be a major tourist destination. Tourist numbers are around a million and a half visitors, with a higher influx in the summer months. Recent dynamics are very positive. Between 2010 and 2015 the number of enquiries dealt with in the municipal Tourist Information Offices rose by 25.6% and the number of travellers staying in hotels increased by 22.9%. This growth is mostly associated with good performance in the international market. The number of excursionists is also on the rise, with these visitors spending the night in towns spread over a wide radius, including the large tourist towns on the French Cantabrian coast. Although the city continues to maintain its traditional profile as a summer destination, it has been gradually taking on the characteristics of a more complex urban tourism destination. The city’s historic heritage, gastronomy (with internationally renowned restaurants and chefs) and the contemporary cultural scene (with events like the Film Festival) are forming the basis for new tourist attractions. An extended tourism season, together with a rapid rise in visitor numbers, especially excursionists, places tourism at the top of the urban debate agenda. Tourism pressure is high and continues to grow, especially in places that support local attractiveness. As a result, local residents, politicians and municipal technical experts have begun to express their concern for the sustainable management of this “tourism success” and control over its more negative aspects.

3.2. Research Methodology

The work described in this paper adopted an approach to the study of cultural tourism from the territorial paradigm, in line with the Geography-based hypotheses put forward by Jansen-Verbeke [14,61]. This approach, adapted to the study of the impact of tourism, enabled work to be done on the logic of places (a spatial rather than sectoral perspective) with an integrated view of the phenomenon. It involved the need to address the object of study (the historic urban landscape and the transformations brought about by tourism pressure) from different perspectives. In this case, the study of the impact of tourism was tackled in terms of three aspects: its impact on forms of historic urban landscape, on functions and on the meanings attributed through social discourses.

To be able to apply this approach, a wide-ranging set of research tasks were performed. In terms of urban form, an attempt was made to identify the impact on the urban image and the use of public space. To do this, use was made of municipal statistical records (visitor records, tourist transport user records, use of public car parks, automatic footfall counting of pedestrians and cyclists, etc.) plus direct observation at times of major congestion when the pressure undergone by the city centre is more visible.

For the impact analysis of urban functions, use was made of primary data sources such as municipal statistics on housing, population and economic activity; secondary sources included local studies on trade and tourist accommodation, plus an inventory was compiled of active premises in the Parte Vieja by means of field work. This inventory was compiled between August and October 2016, directly coinciding with the dates when tourist numbers in the city were at their highest. The work was aimed at estimating the degree of penetration of tourist activity in this area, paying particular attention to the links between tourism and the retail trade and hospitality sectors. To do this, information was gathered from all ground floor premises (a total of 499). The database compiled from this information was handled with GIS programs (Geographic Information Systems) to produce maps based on geographical information obtained from the province government and the city’s urbanism department.

Lastly, analysis of the discourse and of the meanings of the impact was based on carrying out a series of semi-structured interviews with local stakeholders (public authorities and trade and residents’ associations), on taking part in a number of urban debate forums as observers and on compiling local and regional news items on the issue.

4. Results and Discussion

In geographical terms, the tourist destination of Donostia-San Sebastián was built around its coastline, with the Parte Vieja, the historic city centre, in the middle. This area is packed with heritage, it is very small and it has high levels of tourism activity. Owing to the growth and changing tourist numbers the city receives, this use is on the rise. Based on the analyses carried out, the following sections describe the main factors of change caused by tourism in this space.

4.1. Occupation of the Public Space and Deterioration of the Urban Landscape

The growth of tourism activity has direct repercussions on the levels of use of public space and tourist attractions in Donostia-San Sebastián. The impact, which affects the formal aspects of the historic urban landscape, is especially noticeable in the Parte Vieja. Firstly, the high concentration of visitors affects mobility and use of the public space (see Figure 2). Tourists and excursionists make a very selective use of the urban space in Donostia-San Sebastián, and have specific mobility patterns and behaviours [62]. In some cases, these different patterns prevent spatial-temporal overlaps and reduce pressure on the space. In other cases, they converge with the patterns of local residents, resulting in very high densities of use. Although information available on pedestrian mobility does not allow differentiation between movements by Parte Vieja residents, by residents from other parts of the city, and by visitors, footfall recorded in various locations gives an idea of the levels of use in the busiest spaces and junctions. In the Parte Vieja on 21 December 2015, the footfall counter using thermal detection technology recorded 17,560 pedestrian hits in barely three hours. Although these are mobile flows, the relationship between the surface area of the space, the public thoroughfare available in the Parte Vieja, and the volume of visitors shows an extremely high density of use.

Figure 2.

Photograph illustrating visitor crowding in Calle Mayor in the Parte Vieja. August 2016. Source: The authors.

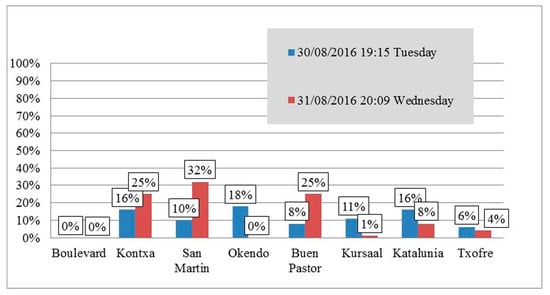

Car parking and wheeled traffic management is highly problematic, particularly at times when extraordinary events are being held. The mass influx of visitors in private vehicles causes severe congestion in public car parks and brings the streets around the fully pedestrianised Parte Vieja to a standstill. The car parks closest to the historic centre and the beach area record close to 100% occupancy rates at many times of day (see Figure 3). This is a typical situation in summer, when the number of day trippers rises significantly. On these days, vehicles are forced to drive round the streets in search of a parking space, causing traffic jams, a regular occurrence that is repeatedly covered by the local press during the high season.

Figure 3.

Real-time parking space availability in Donostia-San Sebastián. Source: Produced by the authors based on real-time access to car park occupation data provided by San Sebastián City Council. Directorate general of Mobility.

Competition for the use of public space is also related to deterioration in the quality of the urban landscape. In the Parte Vieja, with its narrow pedestrianised streets, passers-by repeatedly come across installations that extend business out into the public space. This process has been adopted both by the hospitality industry, where the bar table and open-air terrace bar phenomenon severely restricts available pavement space, and by retail trade, which has extended the sales space into the public thoroughfare with posters and display units. Around one third of ground floor premises occupy the public space (inventory data from July 2016). A total of 165 premises (see Table 1), especially souvenir shops (26), food shops (26) and above all, bars, cafés and restaurants (88). Of these, 32 have an open-air terrace or bar tables on the street, 34 have small outdoor bars to cater for smokers, and 22 have some other kind of element such as awnings, stools and menu display units. In addition to the privatization of public space, these practices lead to the banalisation of the urban landscape. In fact, in the Parte Vieja, a tourist commercial landscape is gradually taking over, with unsatisfactory results. The proliferation of standardised media homogenises the historic urban landscape, trivialises it, takes away its personality (undermining local urban identity) and places it at the same level as other overcrowded destinations (see Figure 4).

Table 1.

Donostia-San Sebastián. Businesses in ground floor premises. Occupation of the public space. Parte Vieja. 2016.

Figure 4.

Photographs illustrating the proliferation of posters, display units and various signs for global products in the Parte Vieja (Coca Cola take away, the “Paellador” advertising board, etc.). Source: The authors. August 2016.

4.2. The Reorientation of Trade and Hospitality to Tourist Demand

The Parte Vieja is an area with lively commercial and hospitality activity. In addition to local residents, its main target market comprises the rest of the city and a large part of the historic region of Guipúzcoa. The growth in visitor numbers is producing a noticeable change in local economic activity, with a gradual reorientation towards meeting tourist demand. Fieldwork has enabled the authors to identify 499 active premises occupying practically the entire surface area available on the ground floor of buildings (see Table 2). Of the 499, 41 are involved in direct tourism activities (8.22%): souvenir shops, tourism services company offices and cultural facilities used by visitors. Shops, bars and restaurants account for another 336 establishments (67.33%). Depending on their product and location, these activities are likely to have visitors among their customers, which is why they are included as indirect tourism activities. Tourism is gradually gaining importance as a means of economic activity in the Parte Vieja. On the one hand, souvenir shops and other similar businesses are on the rise. On the other hand, the remainder of shops and hotel establishments are adapting to meet demand from outsiders, in terms of opening times, products and other aspects. At the same time, franchise establishments and/or those owned by global brands are starting to appear, along with an extension of the tourism commercial landscape, which is spreading its sales area out onto the street.

Table 2.

Businesses in ground floor premises. Parte Vieja. Donostia-San Sebastián. 2016.

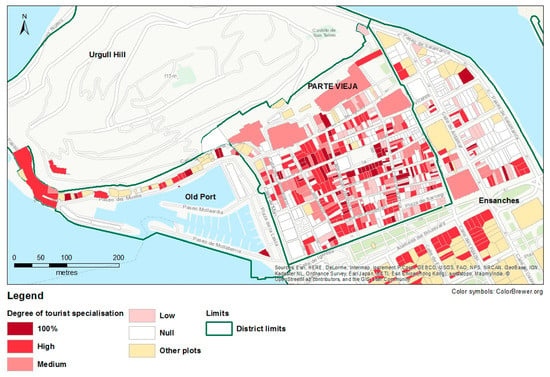

The process of change can be seen clearly in retail trade. At city level, this sector consists of 2847 establishments and provides employment for 8753 people. Over the last few years, the number of commercial establishments has fallen as a result of the drop-in consumption during the crisis and the high rental price of premises [63]. But, at the same time, the sector has become more tourist-oriented. Tourism has become a strategic and operational option for many establishments, and this backed by studies in the Trade Strategic Plan (2015) and the Plan for Promoting Tourism and Trade (2015) promoted by the municipal administration. In the Parte Vieja, retail trade accounts for 41% of all ground floor business premises and their connection with tourism activity is particularly evident. Although the results of the inventory show that there is a relatively wide range of businesses, they are all very closely linked to tourism. Out of the 206 traders in the Parte Vieja, 38% are closely or very closely linked to tourism (see Table 3 and Figure 5). At the other extreme, only 21% of premises are not connected with tourism at all. By types of activity, souvenir shops and similar businesses are highly dependent on tourism, but this is also true of food shops and shops selling fashion and accessories. In these cases, the percentages of total or high dependency on tourism are 44% and 30% respectively.

Table 3.

Retail trade. Degree of connection with tourist activity. Parte Vieja. Donostia-San Sebastián. 2016 vertical percentages.

Figure 5.

Tourist Specialisation of businesses at ground level in Parte Vieja district and its surroundings (San Sebastián, Spain). Source: The authors based on fieldwork. August 2016.

Hospitality (bars, restaurants and other leisure venues) is another sector undergoing a process of change. This is the indirect tourism activity that benefits the most from the presence of tourists and day trippers. Tourists in Donostia-San Sebastián spend €123.6 per person per day. Expenditure on food, restaurants and/or bars stands at €50. Day trippers spend a very similar amount on the same things, with €49.2 [64]. At municipal level, there are many restaurant establishments with links to local gastronomic tradition and catering for the habits and customs of local residents. Around 1224 establishments are linked to hospitality in the city (not counting accommodation), which gives an average density of 6.6 establishments for every 1000 inhabitants. In the Parte Vieja, the inventory includes 163 premises, accounting for 33% of the total number of ground floor establishments in the area. The levels of tourist specialisation are extremely high (see Table 3 and Figure 5). More than 91% of premises are oriented and linked to custom coming in from outside the city, with 64% catering wholly or mostly for tourists alone. Plus, this type of business has been found to be on the increase. The Parte Vieja has traditionally been a place where the local community go for a meal or a drink, however, over the last few years more and more tourists are coming here to eat out. Since 1994, municipal regulations have governed the number of hospitality industry premises. These regulations prevent new premises being opened in saturated areas if a minimum separation distance is not respected. However, there has been a marked expansion in the area covered by existing businesses that have extended into nearby empty premises, often using them as storage facilities and service areas. Even though the number of businesses has not increased, the surface area given over to hospitality usage is growing.

4.3. Growth and Transformation of Tourist Accommodation

The tourist accommodation sector in Donostia-San Sebastián is thriving, dynamic and very profitable. It is composed of 146 establishments, including hotels, guest houses, camp sites and rural tourism accommodation, with a capacity of around 8118 beds. There is also a “liquid” supply of homes for tourist use, most of which are in an irregular situation in terms of local planning regulations. According to local estimates [65], this supply comes in a wide range of options: at least 450 homes with 2000 beds are units managed by companies with permits issued by the Basque government; a maximum of 1530 homes and 7400 beds are advertised on the websites of Airbnb, HomeAway and Trip Advisor.

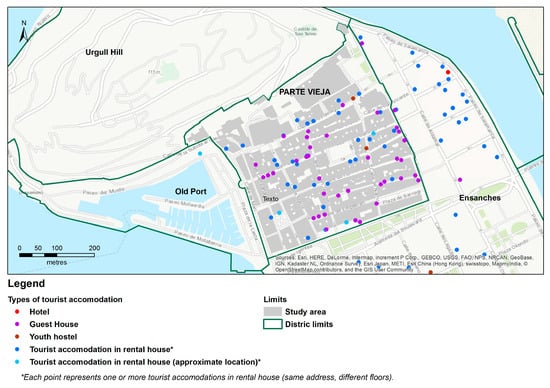

The Parte Vieja houses a major part of the accommodation on offer (see Figure 6). The first significant component in this provision is that of guest houses and youth hostels; a total of 38, with 383 beds. These are small, low-category establishments based on the middle floors of multiple-use buildings. The ground floors of these buildings are occupied by shops, bars and restaurants. The remaining floors are for residential use, alongside the various forms of tourism accommodation. The layout of the urban road system and the built fabric has made building large hotels difficult, so they have opted to be located in other parts of the city. This situation is changing. At the moment, two hotel projects are underway and are expected to provide around 182 beds. Both projects are situated opposite the old fishing harbour, which has been extensively refurbished to rebrand it as a leisure and tourism space. Nearby is the Aquarium, one of the city’s recreational amenities with the highest number of visitors (306,447 in 2015).

Figure 6.

Tourist Accommodation in Parte Vieja district and its surroundings (San Sebastián, Spain). Source: The authors based on fieldwork. August 2016.

The second component of the supply is that of properties for tourist use. Renting out these homes has been a traditional activity in the city and is linked to long stays in the summer. The recent trend for P2P platforms has led to a rise in this activity. The new customer profile is young, cosmopolitan and technology savvy. This is a genuinely urban tourist, unlike the city’s traditional customer profile. Even though there are no data on the exact number of tourist use properties, local estimates (op. cit.) consider 1530 tourist use properties in Donostia-San Sebastián in P2P platforms (502 are supplied by individual owners and 1028 by trading agents). This number includes both regulated and unregulated tourist use properties. According to it, the district Parte Vieja concentrates 15% being on the third position and is invested by at least 8 trading agents.

In this part of the city, various factors of attraction converge: the built landscape, the proximity of beaches, the leisure and entertainment scene, pedestrianised streets and squares and the central location of the historic city centre. Using the regional govern database and the city council website, we have located 40 tourist-use properties in this part of the city, with an estimated capacity equivalent to 167 beds. The number of these type of properties has raised from 0 in 2010 to 40 in 2016. In absolute terms, this is not a particularly significant trend, as yet, although these figures may possibly underestimate the scope of the phenomenon. This activity has appeared only very recently, and is still very new and spread fairly unevenly in this part of the city. As the majority of units do not comply with local planning regulations, they are part of the informal tourism economy. At urban level, the boom in properties for tourist use is one of the most active factors in the ‘touristification’ of the Parte Vieja, with the aggravating circumstance being that it is based in high-rise and directly on residential use and not at the expenses of other forms of tourist accommodation (as is proven by the continuity of the number of guest houses, hotels and youth hostels in the same period).

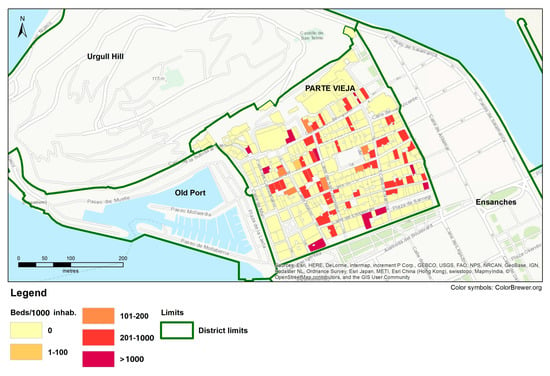

We have used number of beds per 1000 inhabitants as an indicator of accommodation specialisation. At city level, a figure of 55.49 was obtained (taking as reference a total number of 10,325 beds, 2207 of which are clearly identified homes for tourist use). The Parte Vieja has 3858 residents and 550 commercial accommodation beds, which means that already there are 142.56 beds per 1000 inhabitants. Analysis on a larger scale means we can identify the areas subject to greater transformation, as can be seen on Figure 7. At street block level, many are recording values of over 200 beds per 1000 inhabitants. And in some smaller blocks, the accommodation capacity is greater than the resident population. In terms of plots, 41 out of 325 show values of 201–1000 in the beds per 1000 inhabitants ratio, and there are 10 in which the accommodation capacity exceeds the resident population. In general, these are plots facing the busiest streets: Portu, Nagusia, Boulevard, San Jerónimo and Abuztuaren. When planned capacity (current supply plus new hotel developments underway) is taken into account, a higher specialisation value is obtained, 189.73 beds per 1000 residents. There is no doubt that the expansion of the accommodation supply is one of the main factors in the touristification of this part of the city.

Figure 7.

Intensity of Tourist Beds per plot in Parte Vieja district (San Sebastián, Spain). Source: The authors based on fieldwork. August 2016.

4.4. The Social Perception of Tourism: Actors, Discourses and Contestation

At present, there is growing concern for the negative impacts that may be caused by the rapid rise in visitor numbers. This concern is reflected in the media, in emerging social movements and on the local political agenda. Compared to what used to happen in previous years, when institutional discourse was focused almost solely on the benefits of rising tourist numbers, news items are now starting to appear that put this discourse into context and turn the spotlight on the more negative effects of tourism. Editorials, features and opinion columns are talking about the issue in the printed press, online, in blogs and on social media. Taking the opposing view to the position of business owners in the accommodation and hospitality sectors, who are keen on continuing to attract more visitors, is the voice of the Parte Vieja residents, who are complaining about the high levels of overcrowding and tourist pressure that the historic centre is being subjected to (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Confrontation of discourses in the press. Note: On the left, the front page is surprising in its positive take on the picture of the street, with the headline “The hospitality scene confirms the tourist boom and asks for better transport” and continues: “Gipuzkoa is enjoying a tourism Belle Époque and the best is yet to come”. Whereas the second front page follows a different line of news, alerting of the perceived threats from tourism. The headline reads “The last summer before this all blows up”. Source: (Left) Anuncibay A, 29 March 2016, Noticias de Gipuzkoa. (Right) Pagola J. 22 July 2015 in Kulturaldia.

The local community view of tourism was the object of a study carried out in 2016 by Camio [66]. The study used a survey to analyse the attitudes of residents in the Parte Vieja, showing a fairly consistent level of consensus in identifying the problems caused by mass tourism: invasion of the public thoroughfare by visitors, excessive occupation by traders, increase in noise levels, more rubbish and higher prices for goods and services, especially for housing. Of the sample selected, 58% were born in the neighbourhood, a figure that rose to 84% if the people who had been living there for more than 10 years were included. A total of 80% of people surveyed received no direct or indirect income from tourism.

This view of the negative impacts of tourism is the basis for an emerging local residents’ movement. In 2013, the local community association (Parte Zaharrean Bizi) and the youth assembly (Urgullpeko Gazteak) were both set up. These are new actors who are opposed to the discourse that was dominant up to now, marked by trade organisations in the sector: bar and restaurant owners in Guipuzkoa (Gipuzkoako Ostalaritza Elkartea), local bar and restaurant owners and traders (Zaharrean) and hotel owners in Guipuzkoa (ADEGI). The emerging voice of local resident groups has served to create spaces for discussion (for example, the round tables set up on noise, tourism, etc.), and even to generate fledgling joint action at neighbourhood level to restrain some of the impacts regarded as negative: the disappearance of the local language, noise at night and the mass occupation of public space (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Main negative impacts identified by neighbourhood groups.

Today’s answer has a precedent in a social movement called Donostiako Piratak. Although it was set up to provide an alternative model to the “Semana Grande” (or Big Week), the city’s official festival, the movement questions processes, policies and forces of change that are seen as threats to the local community’s quality of life, right to the city and identity. One of these threats is the current tourism model. Since 2003, the Donostiako Piratak festival has been held every year on the dock of the Parte Vieja Port area, a space that symbolises the city’s functional transformation and that has enormous identity value, especially for residents in the historic centre of Donostia-San Sebastián.

As has been evident in other European cities [59], the growing awareness of the negative impacts of tourism channels movements that question the prevalence of policies aimed at tourism growth that apply an insufficient amount of regulation, control and planning in their development. In the last instance, the views collected suggest that demands are largely focused on building alternative destination models, more in harmony with other urban functions.

5. Conclusions

The rise in tourist numbers is having an impact on the Parte Vieja of Donostia-San Sebastián. The city’s historic urban landscape, one of the elements that make it so attractive to tourists, is being threatened by a rapid touristification process. As Jansen-Verbeke [14] points out, this process involves a formal and functional change brought about by the rise in tourism activity. The threats affect the formal, socio-economic and symbolic aspects of this landscape. However, the extent of the impact is different depending on which aspect you look at.

In terms of the urban layout, the loss of quality in the historic landscape and its image is particularly striking. In Donostia-San Sebastián, tourism has produced urban landscape. In fact, it has given the city many iconic buildings that are part of its tourist image, like the Hotel María Cristina, the Hotel de Londres y de Inglaterra, the railings along the promenade at La Concha beach and the Balneario de La Perla spa complex. However, today’s tourism activity is devaluing the landscape of the Parte Vieja. Touristification involves a process of banalisation and homogenization of the landscape, in which global brands are beginning to make an appearance. This stereotyped commercial landscape is completely opposed to the glamour of the Belle Époque on which the destination’s tourism success has been based. The impoverishment of the landscape entails a process of “urbanalisation” [67]. The fact that cities are clearly oriented (especially in their central areas) towards consumerism and activities related to leisure, culture and global tourism, seems to indicate that the urban experience in culturally dissimilar places is similar and interchangeable.

Because of its historic origins, public space in the Parte Vieja is limited. The streets, which are pedestrianised, are narrow and there is hardly any open space. As a result, the growth in visitor numbers leads to overcrowding and causes serious mobility and car parking problems. Visitors and residents view large numbers of people very differently. Up to now, satisfaction surveys carried out by the City Council do not show that this is a problem for visitors. Like many popular mass tourism destinations, large crowds make for “atmosphere” and are only rejected if they cause very severe problems for a holiday stay (more expensive services, inflated prices, car parking problems, queueing for tables in local restaurants and so on). Residents, on the other hand, are much more sensitive. They see the large numbers of people as congestion, since it has a negative effect on their quality of life, especially in the area of public order (anti-social behaviour, noise, dirt, people’s safety, lack of access for ambulances, etc.). Problems with overcrowding in public spaces result in the loss of residential attractiveness in the Parte Vieja, which is losing residents while increasing its focus on tourism.

In socio-economic terms, the impacts of tourism are equally evident. In Donostia-San Sebastián, the intensive use of historic spaces by visitors brings with it an increase in competition for central spaces with displacements and changes of use. Different processes can be seen that affect retail trade, hospitality, accommodation and the residential function. In the Parte Vieja, local urban retail trade (geared to cater for residents) is being gradually replaced by establishments targeting tourist customers. Souvenir shops are evident in many streets, and a large proportion of the other establishments are focusing their products and services on the visitor market. An identical process is observed in hospitality establishments (bars and restaurants). There has been a surge in new formats, with takeaway products and standardised international food that contrasts with the wealth of local gastronomic tradition. The amount of accommodation is also growing, in terms of both conventional formats and tourism rental properties.

According to the local community association and social movements, the touristification of trade and hospitality, together with the occupation and massification of the public space, damages residents’ quality of life. They are therefore indirect processes that drive out the residential function. These processes (which have already been going on for some time in the Parte Vieja) have recently been joined by the expansion of tourism rental properties. Some residents are starting to abandon the centre, putting their homes on the tourism market and moving to live in other areas. At the same time, new investors are appearing and trying to make the most of this market niche. This means the city’s residential function is being threatened, and this may start a vicious circle: fewer residents, fewer traders catering for residents and more businesses catering for tourists. So, the loss of population would reinforce the tourist orientation of the area’s establishments. This process raises concern, as touristification can lead to a tourism monoculture of the kind referred to in classic research on the “vicious circle of tourism” in heritage cities [19].

Lastly, at the symbolic level, the Parte Vieja is an area where the tourism conflict is exacerbated. On the one hand, the hospitality sector views the growth of tourism as a great business opportunity and takes action against any possible mitigation and control measures. On the other hand, local residents’ associations in the neighbourhood are expressing their dismay at the growth of tourism and the loss of quality of life it brings for them. They also disagree with urban regeneration projects in the Port area that break with the city’s maritime tradition and will lead to the complete domination of the tourist industry there. Tourism is equally seen as a factor in the banalisation of local culture, whose customs and traditions are being adapted to suit foreign consumers. However, we have to take into account that touristification processes also have a local component: residents from the rest of the city and the metropolitan area habitually use the Parte Vieja for leisure and entertainment and cultural practice. In this context, the local government is searching for the difficult balance between the interests of all local stakeholders. In fact, the challenge of balanced tourism growth is one of the key themes of the city’s Tourism Master Plan.

In summary, it can be said that certain aspects of recent tourism development in San Sebastián pose a threat to safeguarding the heritage values of the historic urban landscape in the Parte Vieja. At a formal level, there are problems that can more or less be resolved from a technical point of view (urban management, mobility, cleaning, etc.). However, the problems associated with functional touristification are much more worrying. The scope of changes brought about by tourism in the commercial landscape of the Parte Vieja and in its functional profile (increase in tourism businesses, violent invasion of tourist rental properties and loss of population) may turn this space into an area of tourism monoculture. This process threatens the sustainability of the historic urban landscape. The neighbourhood is becoming a leisure district with no residents in which the values of the urban layout are being maintained but with the loss of its condition as a living urban space. As a result, its sustainability is being threatened.

The processes described in research on the impact of tourism are being reproduced in the Parte Vieja of Donostia-San Sebastián. Some of them were detected some time ago (touristification, functional change), but others are only being highlighted more recently (commercial gentrification, tourism gentrification). Similar to many other European cities, managing successful tourism becomes a key issue on the urban agenda, and Donostia-San Sebastián is facing the challenge of correctly regulating and channelling tourism activity. At the City Council, work is being done on several fronts: urban planning regulation involving activity licences for tourism properties, municipal by-laws limiting the opening of new hospitality establishments in saturated areas, pedestrianisation and a policy of sustainable mobility, etc. Nevertheless, the thresholds that mark the destination’s load capacity are unclear because there are varying views on the extent of the impact of tourism on the city.

The case study carried out opens up interesting lines of work, and enables a future research agenda to be drawn up. The city of Donostia-San Sebastián exemplifies very well the cultural values associated with this new UNESCO’s heritage category (HUL). It is not a city with great monumental resources but its attractiveness is related to the quality of the urban plot, the care of the public space and the beauty and splendour of the residential buildings of the bourgeois areas, coupled with more intangible aspects, like quality of life and the urban environment. The integrating nature of this concept has allowed us to embrace the study from a multidimensional approach that has led to the selection of the three dimensions of study we have proposed here: form, function and significance. Undoubtedly, this approach does not exhaust the potential of the HUL framework and opens new lines of research to complete it.

The tourism sustainability of historic urban landscapes requires deciding the extent to which processes involving impacts are attributable to tourism or whether they are due to the logic of more general processes of social change. Research is also needed that differentiates between tourism consumption from non-tourism consumption (linked to more or less recurring urban/metropolitan leisure patterns). The processes of tourism metropolisation, like the expansion of false excursionism [19], entail coming up with adequate formulas of tourism government across the region. The logic of municipal public action is not set up to deal with the size of the real tourism destination that goes beyond the limits of administrative competencies. Lastly, it would be highly pertinent to work on the scales of tourism impact. Positive impacts often affect the destination as a whole, whereas negative impacts tend to be concentrated only in more enclosed areas, in this case the Parte Vieja. Tourism will only be sustainable if it can guarantee that this part of the city can be safeguarded.

Author Contributions

María García-Hernández and Manuel de la Calle-Vaquero conceived and designed the methodology and analyzed the data; Claudia Yubero performed the cartography; and María García-Hernández, Manuel de la Calle-Vaquero and Claudia Yubero performed the methods and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ECM Benchmarking Report 2016. Available online: http://www.europeancitiesmarketing.com/research/reports-and-studies/ecm-benchmarking-report/ (accessed on 20 April 2017).

- Arias, A.; Quaglieri, A. Unravelling Airbnb: Urban perspectives from Barcelona. In Reinventing the Local in Tourism: Producing, Consuming and Negotiating Place; Russo, A.P., Richards, G., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2016; pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S. Urban Tourism; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cazes, G.; Potier, F. Le Tourisme Urbain; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Law, C.M. Urban Tourism: The Visitor Economy and the Growth of Large Cities; Continuum: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S. Managing Urban Tourism; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson, A.; Wall, G. Tourism: Economic, Physical, and Social Impacts; Longman: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, L.; van der Borg, J.; Meer, J. Urban Tourism: Performance and Strategies in Eight European Cities; Aldershot: Avebury, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.G. An integrative framework for urban tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 926–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Borg, J.; Costa, P.; Gotti, G. Tourism in European heritage cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitiño Vinuesa, M.A. Turismo y desarrollo sostenible en ciudades históricas. Ería 1998, 47, 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- De la Calle Vaquero, M. La Ciudad Histórica como Destino Turístico; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A.P.; van der Borg, J. Planning considerations for cultural tourism: A case study of four European cities. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. The territoriality paradigm in Cultural Tourism. Tourism 2009, 19, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. The Tourist-Historic City; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Glasson, J. Oxford: A heritage city under pressure: Visitors, impacts and management responses. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Godfrey, K.; Goodey, B. Towards Visitor Impact Management: Visitor Impacts, Carrying Capacity, and Management Responses in Europe’s Historic Towns and Cities; Aldershot: Avebury, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- García Hernández, M. Turismo y Conjuntos Monumentales: Capacidad de Acogida Turística y Gestión de Flujos de Visitantes; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A.P. The “vicious circle” of tourism development in heritage cities”. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Page, S. Urban tourism research: Recent progress and current paradoxes. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlett, G.; Fletcher, J.; Cooper, C. The impact of tourism on the Old Town of Edinburgh. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 16, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo Viu, J.; Romaní Fernández, J.; Suriñach Caralt, J. The impact of heritage tourism on an urban economy. The case of Granada and the Alhambra. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 361–376. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, L.C.; Sanz, J.Á.; Devesa, M.; Bedate, A.; del Barrio, M.J. The economic impact of cultural events: A case-study of Salamanca 2002, European Capital of Culture. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2006, 13, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, A.J.; Snaith, T.; Miller, G. The social impacts of tourism: A case study of Bath, UK. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.J.; Li, J.M.; Kim, H.-K. Community residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards heritage tourism in a historic city. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2007, 4, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Riganti, P.; Nijkamp, P. Congestion in popular tourist areas: a multi-attribute experimental choice analysis of willingness-to-wait in Amsterdam. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryon, J.; Neuts, B. Crowding and the Tourist Experience in an Urban Environment: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Available online: http://www.steunpunttoerisme.be/main/files/nieuwsbrief/oktober_2008/paperNVVS_bart_neuts.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2017).

- Popp, M. Positive and negative urban tourist crowding: Florence, Italy. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 14, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Living in a World Heritage City. Stakeholders in the dialectic of the universal and particular. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 8, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Gillot, L. Heritage and tourism: A dialogue of deaf? The case of Brussels. Riv. Sci. Tur. 2010, 1, 263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, A.; Staniscia, B. Rome: A difficult path between tourist pressure and sustainable development. Riv. Sci. Tur. 2010, 1, 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, M.; Hidalgo, C. Tourism in the historic cores, Conflict or opportunity? The stakeholders point of view in Madrid’s case. Riv. Sci. Tur. 2010, 1, 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, P.-C. Resident attitudes toward heritage tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2011, 12, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, L. Residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in a historical-cultural village: Influence of perceived impacts, sense of place and tourism development potential. Sustainability 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Hu, H.; Kavan, P. Factors influencing perceived crowding of tourists and sustainable tourism destination management. Sustainability 2016, 8, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, T.; Zhang, T.; Fujiki, Y. The social and cultural impact of tourism development on World Heritage Sites. A case of the Old Town of Lijiang, China, 2000–2004. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 97, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, A. Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites: A Practical Manual for World Heritage Site Managers; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, D. Tourism at World Heritage Cultural Sites: The Site Manager´s Handbook; US/ICOMOS—World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. Cultural Heritage and Tourism Development. A Report on the International Conference on Cultural Tourism, Siem Reap; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. Tourism Congestion Management at Natural and Cultural Sites; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. Global Report on City Tourism—Cities 2012 Project (AM Reports: Volume Six); UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat & UNESCO. Historic Districts for All. A Social and Human Approach for Sustainable Revitalisation. Manual for City Professionals; UN-Habitat & UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Defining, Measuring and Evaluating Carrying capacity in European Tourism Destinations; Final Report B4-3040/2000/294577/MAR/D2; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz, V.; Elliott, M.A. Tourism and sustainability in the evaluation of World Heritage Sites, 1980–2010. Sustainability 2016, 8, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirfan, L. World Heritage, Urban Design and Tourism. Three Cities in the Middle East; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.; Tallon, A. Geographies of gentrification and tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Geographies; Wilson, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gravari-Barbas, M.; Guinand, S. Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises. International Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- LeVine, M. The ‘New-Old Jaffa’: Tourism, gentrification, and the battle for Tel Aviv’s Arab Neighbourhood. In Consuming Tradition, Manufacturing Heritage: Global Norms and Urban Forms in the Age of Tourism; AlSayyad, N., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 240–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism gentrification: The case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2004, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.M.; Smith, N.; Mejías, M.A. Gentrification, displacement, and tourism in Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Urban Geogr. 2007, 28, 276–298. [Google Scholar]

- Füller, H.; Michel, B. ‘Stop Being a Tourist!’ New dynamics of urban tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, M. Fent barri: Heritage tourism policy and neighbourhood scaling in Ciutat de Mallorca. Etnografica 2009, 13, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiernaux, D.; González, C.I. Turismo y gentrificación: Pistas teóricas sobre una articulación. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2014, 58, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, V. Patrimonio urbano, turismo y gentrificación. In Perspectivas del Estudio de la Gentrificación en México y América Latina; Delgadillo, V., Díaz, I., Salinas, L., Eds.; UNAM: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2015; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.B. Urban conservation and revalorisation of dilapidated historic quarters: The case of Nanluoguxiang in Beijing. Cities 2010, 27, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola Gant, A. Holiday Rentals: The New Gentrification Battlefront. Sociol. Res. Online 2016, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesar, O.; Dezeljin, R.; Bienenfeld, M. Tourism gentrification in the city of Zagreb: Time for a debate? Int. Manag. Res. 2015, 11, 657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Colomb, C.; Novy, J. Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Cuesta, G. San Sebastián: Un modelo de construcción de la ciudad burguesa en España. Ería 2013, 88, 101–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. A Geographer’s Gaze at Tourism. Doc. Anàl. Geogr. 2008, 52, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- CICtourGUNE. eGIStour. Sistema de Medición y Modelización de Flujos Turísticos. Informe 2010. Available online: http://observatorioturisticodeeuskadi.basquetour.net/en/estudios-y-publicaciones (accessed on 20 April 2017).

- Turismo de San Sebastián—Donostia Turismoa. Plan de Impulso al Turismo y el Comercio de Donostia—San Sebastián; Turismo de San Sebastián: San Sebastián, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Turismo de San Sebastián—Donostia Turismoa. Informes Sobre Perfil y Satisfacción del Turista de Donostia—San Sebastián; Turismo de San Sebastián: San Sebastián, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fomento de San Sebastián. Estudio de Dimensionamiento de la Oferta de Apartamentos Vacacionales en San Sebastián. Propuesta de Medidas de Ordenación y Regulación Urbanística; Fomento de San Sebastián: San Sebastián, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Camio Olaskoaga, M. Análisis de Los Beneficios y Costes Socio-Culturales del Turismo en la Parte Vieja de Donostia-San Sebastián (País Vasco), Desde la Perspectiva de Sus Residentes. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, F. Urbanalización. Paisajes Comunes, Lugares Globales; Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).